1. Introduction

Reconciling quantum mechanics (QM) with the general theory of relativity (GR) remains an enduring challenge in theoretical physics. Although quantum field theory (QFT) and the Standard Model have successfully described three of the four fundamental forces—electromagnetism, the weak interaction, and the strong interaction—an equally robust and experimentally testable quantum theory of gravity remains elusive. Various approaches, including loop quantum gravity [

1,

2,

3,

4], string theory [

5,

6,

7], and asymptotic safety scenarios [

8,

9], have generated significant insights. Nevertheless, key conceptual obstacles persist, as exemplified by the black hole information paradox [

10,

11,

12,

13], which arises from the tension between near-thermal Hawking radiation and quantum unitarity.

The

Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework [

19,

20] offers a discrete-space–time viewpoint in which space–time cells, each endowed with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space, function as localized "memory units" for quantum information. In this picture, quantum fields interacting within Planck-scale cells leave "quantum imprints"—localized records of field states and interactions—thereby providing a mechanism that aims to preserve unitarity even in extreme gravitational settings such as black hole evaporation.

In this work, we extend the QMM framework to incorporate electromagnetic interactions, focusing on local U(1) gauge fields. While quantum electrodynamics (QED) is familiar in the continuum limit, embedding it into a Planck-scale discretized theory, where each cell actively stores and processes quantum information, poses unique challenges. Our approach employs link variables on the edges of the discrete lattice to implement gauge transformations and covariant derivatives, alongside imprint operators that encode electromagnetic field strengths and matter currents in a localized, gauge-invariant manner. This construction is designed to preserve unitarity, locality, and covariance in a discretized setting, going beyond a straightforward adaptation of standard lattice QED.

In the present paper, we focus on the Abelian (U(1)) sector for concreteness; extending QMM to non-Abelian gauge fields (e.g., SU(2), SU(3)) is a central goal of future research. In addition, while the framework aims to reproduce the equivalence principle at scales well above the Planck length, the precise emergence of local inertial frames from the underlying discrete cell structure remains an open problem that we will address in subsequent work.

Compared with strategies relying on extra dimensions or asymptotic boundaries, the QMM is inherently discrete and background-independent, with an explicit focus on quantum informational aspects of space–time. By embedding electromagnetism in QMM, we seek a finite, gauge-invariant discretization scheme that may help regulate ultraviolet divergences and illuminate high-energy QED behavior in a quantum gravitational regime. We emphasize that, while our approach is formulated in a fully discretized context, it remains conceptual and requires further work—particularly to connect the Planck-scale description with macroscopic, continuum-like physics.

This paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we review the central ideas of the QMM: discretization into Planck-scale cells, finite-dimensional local Hilbert spaces, and the imprint mechanism for local encoding of quantum information.

Section 3 describes how electromagnetism is incorporated into QMM through gauge-invariant imprint operators and an interaction Hamiltonian on a discrete lattice. We examine potential physical consequences—including charged black hole evaporation, vacuum polarization, and early-universe cosmology—in

Section 4, emphasizing conceptual and (where feasible) quantitative features.

Section 5 compares the QMM approach to other frameworks, such as holography and loop quantum gravity, highlighting both strengths and open questions. Finally,

Section 6 outlines possible experimental and observational strategies, including astrophysical observations and laboratory analog systems, that could probe QMM-inspired predictions. Throughout this work, we adopt the metric signature

, set

, and label space–time coordinates by Greek indices

. Standard references in quantum field theory, general relativity, and gauge theory [

21,

22] are cited where relevant.

2. Foundations of the Quantum Memory Matrix

In this section, we briefly recapitulate the key elements of the QMM hypothesis that underpin our later extension to electromagnetism. The QMM framework posits that, at the Planck scale, the smooth continuum of classical space–time is replaced by a discrete assembly of finite-sized cells—each acting as an active repository of quantum information. Although many details of the construction have been elaborated in our previous work [

19], here we review the essential principles: the discretization of space–time into finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces, the mechanism by which local interactions leave

quantum imprints, and the way in which unitarity, locality, and covariance are preserved. These features provide the conceptual foundation for incorporating additional fields (including gauge fields) at high energies.

2.1. Discretization of Space–Time and Finite-Dimensional Hilbert Spaces

A central assumption of QMM is that the classical continuum picture of space–time does not hold at the Planck scale (). Instead, in this framework, space–time is composed of discrete, finite-sized cells (sometimes referred to as space–time quanta). These cells serve both as the fundamental geometric building blocks and as localized storage sites for quantum information.

We label each cell by an index

, where

denotes the set of all cells. Each cell

x is associated with a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

. The total Hilbert space of the QMM is then

Within each

, a finite basis of states encodes geometric properties (e.g., discrete spectra of length, area, and volume, conceptually similar to those in loop quantum gravity) as well as any local quantum information relevant to field interactions.

By design, endowing each with finite dimension provides an ultraviolet (UV) cutoff at the Planck scale. In traditional continuum theories, high-momentum divergences arise because there is, in principle, no upper limit on energy modes. In contrast, the QMM discretization implies that operators such as area or volume have discrete spectra, serving as a built-in regularization reminiscent of lattice gauge theory. Moreover, each cell’s finite dimensionality gives the cell an additional role as a "memory unit" where the state of local fields can be imprinted.

Although the fundamental description is discrete, continuum physics can emerge at scales . In such a regime, the collective behavior of many space–time quanta approximates smooth geometry, recovers Lorentz invariance, and yields effective field theories consistent with general relativity and standard quantum field theory. This transition involves constructing imprint operators and interactions that reproduce the known symmetries in the low-energy limit. We note that in the current formulation, the discretization is imposed rather than derived; developing a fully dynamical origin of the cells is a longer-term goal.

2.2. Formal Construction of the Global Hilbert Space

A crucial point in the QMM framework is defining the

global Hilbert space

where

is typically an infinite (and possibly countable) index set of Planck-scale cells. In finite-dimensional quantum mechanics, taking a tensor product of a finite number of Hilbert spaces is straightforward; however, when the index set

is countably infinite, the standard tensor product construction can lead to subtle issues such as nonseparability. In this subsection, we outline how we handle these matters by adapting the notion of an infinite tensor product

à la von Neumann [

28] (see also [

29] for operator-algebraic treatments).

Choice of Reference State

In von Neumann’s approach to infinite tensor products, one begins by choosing a reference vector (or fiducial state) for each local Hilbert space . Denote this reference vector by . A typical choice might be the "vacuum" or a ground state for each cell. One then considers the set of all finite-energy excitations relative to these reference states. Concretely, a candidate global state is viewed as an equivalence class of local modifications away from .

Definition of the Infinite Tensor Product

Let us denote by each finite-dimensional space of dimension . For most QMM models, is uniformly bounded. We pick a reference vector in each . The formal infinite tensor product Hilbert space (in the von Neumann sense) is built as follows:

1. **Elementary Tensors:** Consider finite linear combinations of vectors of the form

where

denotes the product of the reference vectors in all remaining cells. Intuitively, this means only

finitely many cells are excited away from

.

2. **Inner Product:** The inner product between such elementary tensors can be defined so that each factor is orthonormal. Specifically, for two vectors and differing in finitely many cells, their overlap is the product of overlaps in each local Hilbert space . Because only finitely many factors differ from , this product is well-defined and nonzero.

3. **Completion:** We then form the Hilbert-space completion of the space of finite linear combinations under the resulting norm. The result is a well-defined, infinite tensor product Hilbert space in which each cell carries a copy of the local degrees of freedom, but states differ from the global reference at only finitely (or countably) many sites in a square-summable sense.

Cylindrical Consistency and Physical Subspace

In practical quantum gravity or quantum field models, one might demand additional constraints (e.g., gauge constraints, or physically normalizable states) that reduce the naive infinite product to a

physically relevant subspace. In lattice gauge theory, for example, one often imposes

Gauss’s law constraints or other projection conditions. Similarly, in QMM one may require certain boundary-matching or curvature constraints among neighboring cells. These constraints can lead to a

cylindrically consistent projective limit of finite-lattice states [

30,

31].

Operator Algebras and Locality

A related perspective is via local *operator algebras*. For each cell x, let be the algebra generated by imprint operators and possibly geometric operators (e.g., area, volume in a gravitational extension). One then forms the -algebraic (or von Neumann algebraic) inductive limit of the local . The global Hamiltonian emerges from local terms plus adjacency interactions. This approach clarifies how local unitarity extends globally: since each cell is finite-dimensional, each local evolution is unitary, and the global evolution remains unitary under standard operator-algebraic constructions.

Relation to QMM Discretization

Because each is finite-dimensional, the infinite product remains better controlled than in infinite-dimensional quantum field theories, where issues of renormalization and nonseparability can be more severe. The QMM discretization effectively pre-regularizes high-energy modes by capping local state space dimensions at each cell. In physical terms, this results in a built-in ultraviolet cutoff at the Planck scale.

In summary, the infinite tensor product space

can be rigorously defined via von Neumann’s framework or via projective/inductive limits of finite-lattice states. Although subtlety remains—especially regarding constraints that might reduce the naive product to a physically valid subspace—this construction ensures that each Planck-scale cell contributes a finite-dimensional state space, allowing for local imprint operators and a globally unitary time evolution.

2.3. Quantum Imprints and Local Encoding of Information

A cornerstone of the QMM hypothesis is the concept of

quantum imprints—local records left in the QMM cells when quantum fields interact with them. When a field operator

interacts at a cell

x, an imprint is recorded in

. Crucially, these imprint operators act on the tensor product space of the field degrees of freedom

and the QMM cell:

Denoted

, these operators capture the local field configuration (e.g., amplitude, phase, or internal quantum numbers) and couple it to the cell’s finite-dimensional degrees of freedom.

For a generic matter field

, a simple example of how the QMM coupling can be expressed is:

Here,

dictates how the field state modifies the QMM cell’s state and, conversely, how the cell’s state might affect the field. The evolution of the total system remains unitary because these local interactions are incorporated into the global Hamiltonian.

From a semiclassical perspective, processes such as black hole evaporation might appear to lose information. In the QMM view, the "lost" information is instead stored nonperturbatively in the QMM cells via . This information can later become accessible, for example, through interactions with outgoing modes.

2.4. Physical Requirements: Unitarity, Locality, and Covariance

For QMM to be a viable approach that bridges quantum field theory and gravity, it must satisfy:

Unitarity: The global time-evolution operator is unitary when the total Hamiltonian includes QMM, matter, and their interaction terms.

Locality: Interactions occur only within each discrete cell; hence, any influence is propagated cell to cell under causal constraints, without acausal effects at a distance.

Covariance: Although the fundamental level is discretized, the resulting theory must reduce to a generally covariant description at large scales. By building imprint operators and Hamiltonians from appropriate geometric or tensorial objects, the usual coordinate invariance can be approximated in low-energy regimes.

This local, cell-by-cell design ensures that the continuum picture emerges as an effective description, while the underlying QMM structure remains consistent with relativistic principles.

2.5. Retrieval Mechanisms and Information Restoration

In QMM, any information embedded in the cells persists in the global Hilbert space. For example, consider a black hole formed by collapsing matter . When that matter crosses the horizon, imprint operators in the near-horizon cells record the state. As Hawking-like radiation processes occur, the outgoing modes can interact with these imprints, leading to correlations that effectively "return" the hidden information over time. While a detailed black hole evaporation model is beyond our current scope, the existence of these imprint operators in principle offers a mechanism for eventual information retrieval.

2.6. Comparison with Other Discrete Quantum Gravity Approaches

QMM shares certain elements with loop quantum gravity and spin foam models by imposing discrete structures on geometry. However, QMM explicitly treats each cell as a local "quantum memory," going beyond mere geometric quantization. Similarly, causal set theory introduces a discrete underpinning for space–time but focuses on partial orders rather than on local Hilbert spaces.

Because QMM assigns a finite-dimensional Hilbert space to each cell—and explicitly includes imprint operators for matter and gauge fields—it provides a direct strategy for coupling fields to discrete geometry. This sets it apart from purely geometric approaches and underlines how local unitarity can be preserved.

2.7. Implications and Transition to Electromagnetism

Embedding quantum information directly at the Planck-scale structure of space–time potentially resolves certain conceptual challenges in quantum gravity, such as the black hole information conundrum. Up to now, we have focused primarily on scalar and gravitational fields in QMM. Incorporating electromagnetism introduces new considerations: for instance, respecting local U(1) gauge invariance in a discrete setup requires specially designed imprint operators and link variables.

The next section extends the QMM framework to electromagnetism by explicitly constructing such gauge-invariant imprint operators. We outline how photon states and electromagnetic field strengths can be encoded consistently within each cell, maintaining unitarity, locality, and approximate covariance. Ultimately, the same strategy may be generalized to non-Abelian gauge fields, though that remains a future step in realizing a more complete unification with the Standard Model.

3. Incorporation of Electromagnetism into QMM

In this section, we outline how the QMM framework can be extended to include the electromagnetic field in a way that aims to preserve local U(1) gauge invariance, unitarity, and locality on a discretized space–time. Although continuum QED is well studied, embedding gauge fields into Planck-scale, quantum-information–driven cells involves adapting lattice gauge methods for QMM’s imprint operators. Below, we detail a representation based on link variables, propose gauge-invariant imprint operators for the electromagnetic sector, and construct the interaction Hamiltonian. Figures are provided primarily for conceptual illustration rather than as derived numerical plots.

3.1. Gauge Symmetry and the Discretized Electromagnetic Field

In continuum QED, the gauge potential

transforms under local U(1) as

with

an arbitrary real function. The corresponding field strength,

is manifestly gauge invariant.

In the QMM picture, space–time is discretized into Planck-scale cells

. To maintain a local U(1) symmetry, we adopt the standard lattice gauge approach by defining link variables

where

a is the lattice spacing (of order the Planck length) and

q is the charge coupling. This construction:

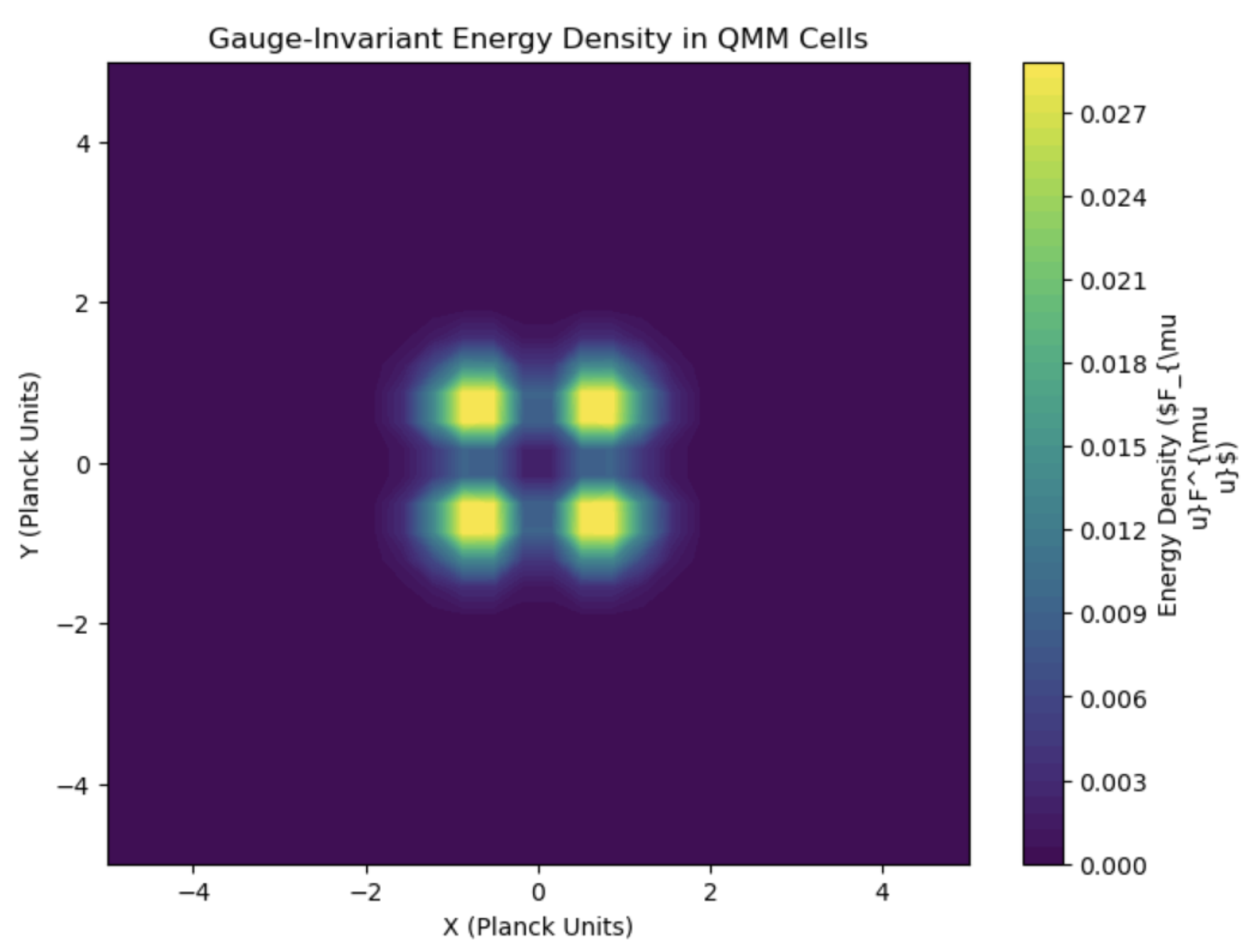

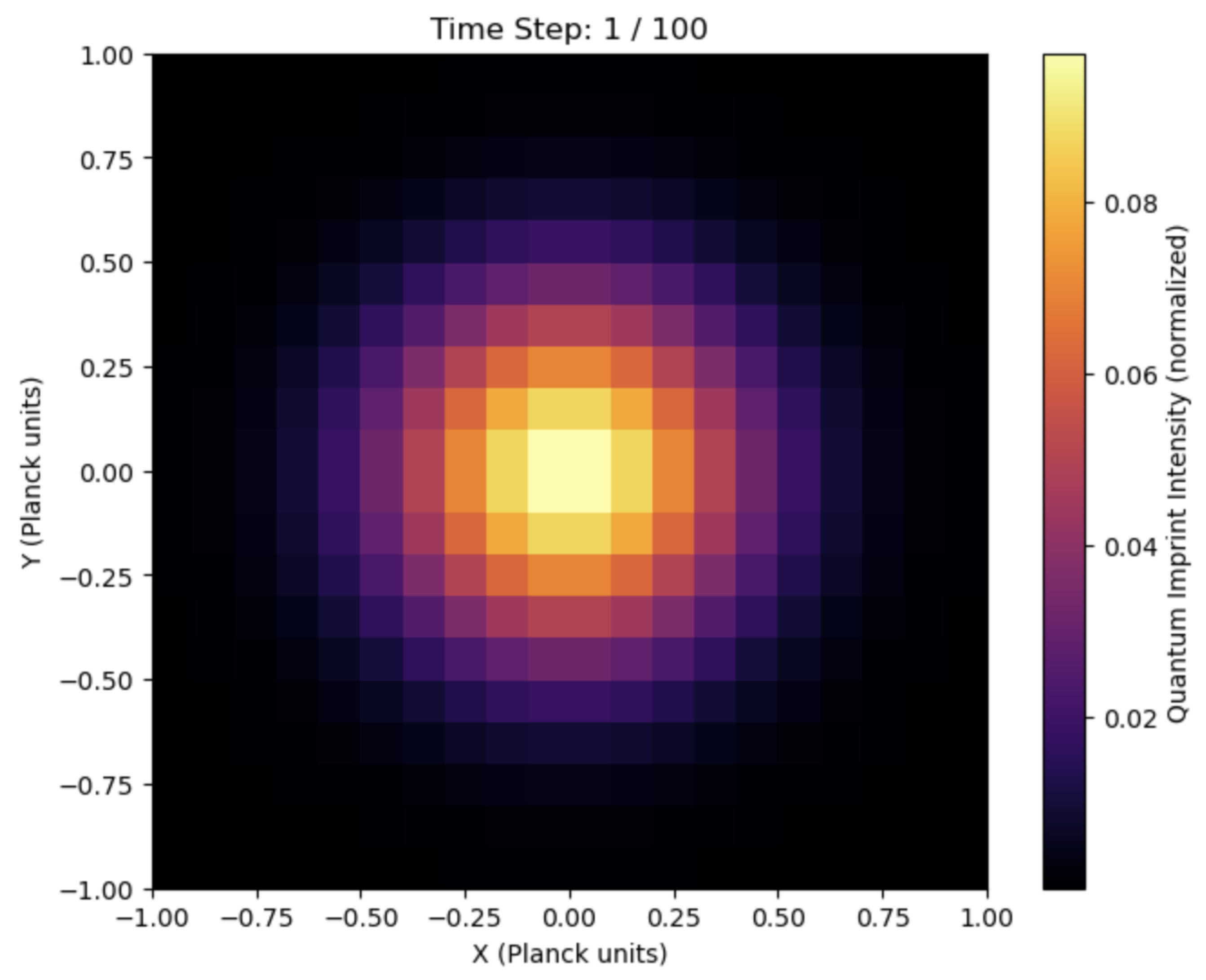

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of how link variables encode electromagnetic information into QMM cells while preserving local U(1) symmetry. This visualization is conceptual; color gradients and labels do not represent computed values.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of how link variables encode electromagnetic information into QMM cells while preserving local U(1) symmetry. This visualization is conceptual; color gradients and labels do not represent computed values.

3.2. Constructing Gauge-Invariant Electromagnetic Imprint Operators

A main challenge is to build imprint operators that record electromagnetic data locally yet remain gauge invariant. In QMM, these imprint operators must act on the combined tensor product space , capturing how the field configuration changes the cell’s finite-dimensional state.

A natural choice for encoding the free electromagnetic field is

where

is a coupling constant with suitable dimensions, and

is the discretized analog of Eq. (

4) (often realized via plaquette operators in a lattice setup). Since

is gauge invariant for Abelian fields, it can serve as a local measure of electromagnetic field strength or energy density.

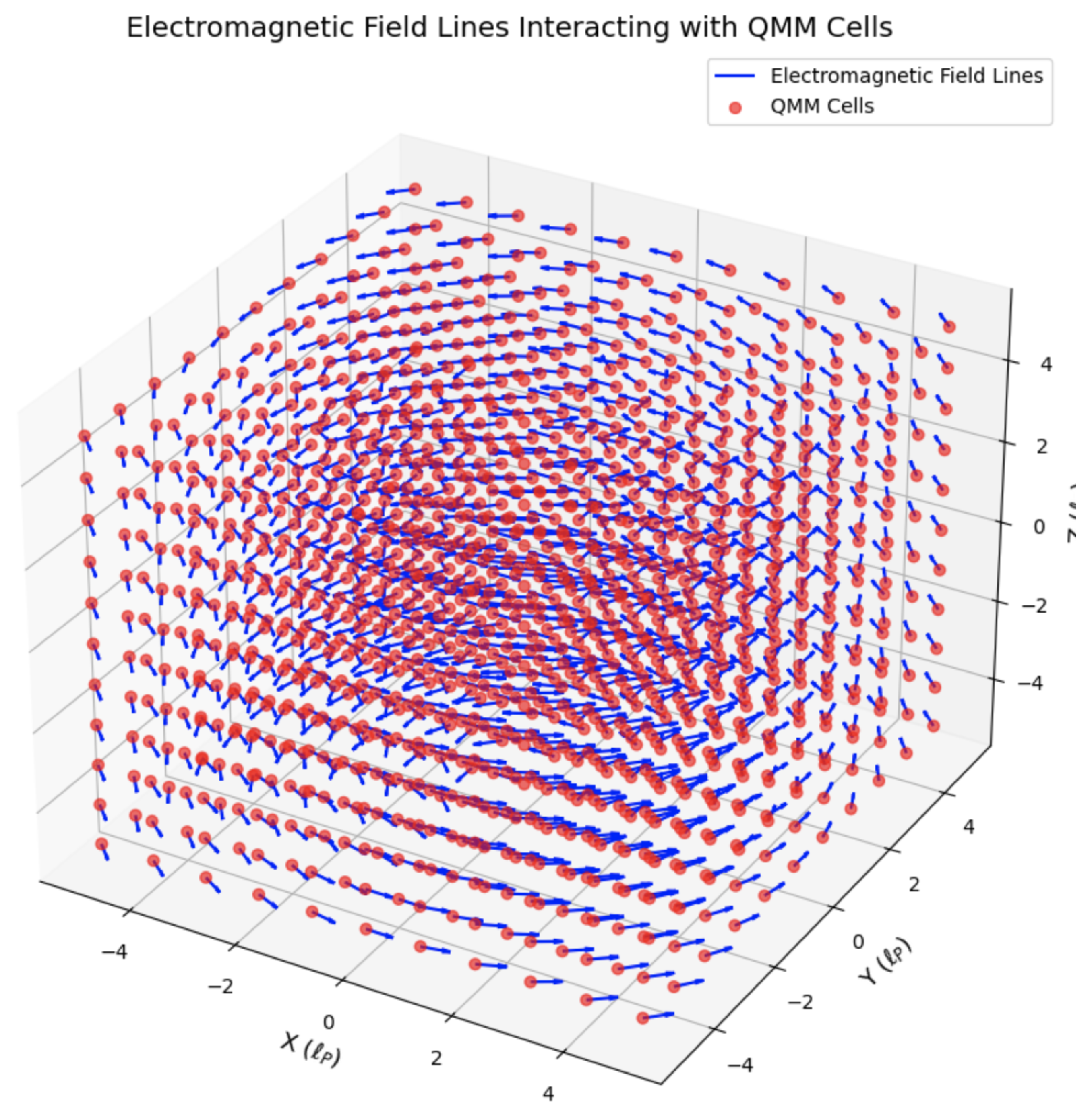

Figure 2.

A conceptual depiction of electromagnetic field lines interacting with QMM cells. Here, can be viewed as an operator that records the local field energy/momentum imprint in the cell’s Hilbert space.

Figure 2.

A conceptual depiction of electromagnetic field lines interacting with QMM cells. Here, can be viewed as an operator that records the local field energy/momentum imprint in the cell’s Hilbert space.

For charged matter fields (e.g., a Dirac spinor

), the minimal coupling arises through discretized covariant derivatives,

Accordingly, imprint operators that capture the local charge-current interactions might look like

where

and

are coupling constants, and

is built in the usual way from matter fields (e.g.,

). Strictly,

alone is gauge-dependent; in a fully gauge-invariant treatment, one employs link variables or closed loops. The final imprint operator, however, must maintain overall gauge covariance or invariance when acting on the cell plus field Hilbert space.

3.3. Interaction Hamiltonian for QMM–Electromagnetism Coupling

Putting these elements together yields a total Hamiltonian with three main pieces:

: Discretized photon (and matter) terms, akin to standard lattice QED.

: Governs the intrinsic dynamics of the QMM cells themselves.

: Couples the electromagnetic degrees of freedom to local QMM imprint operators.

Hence,

In practice,

might contain discrete analogs of

plus fermionic parts.

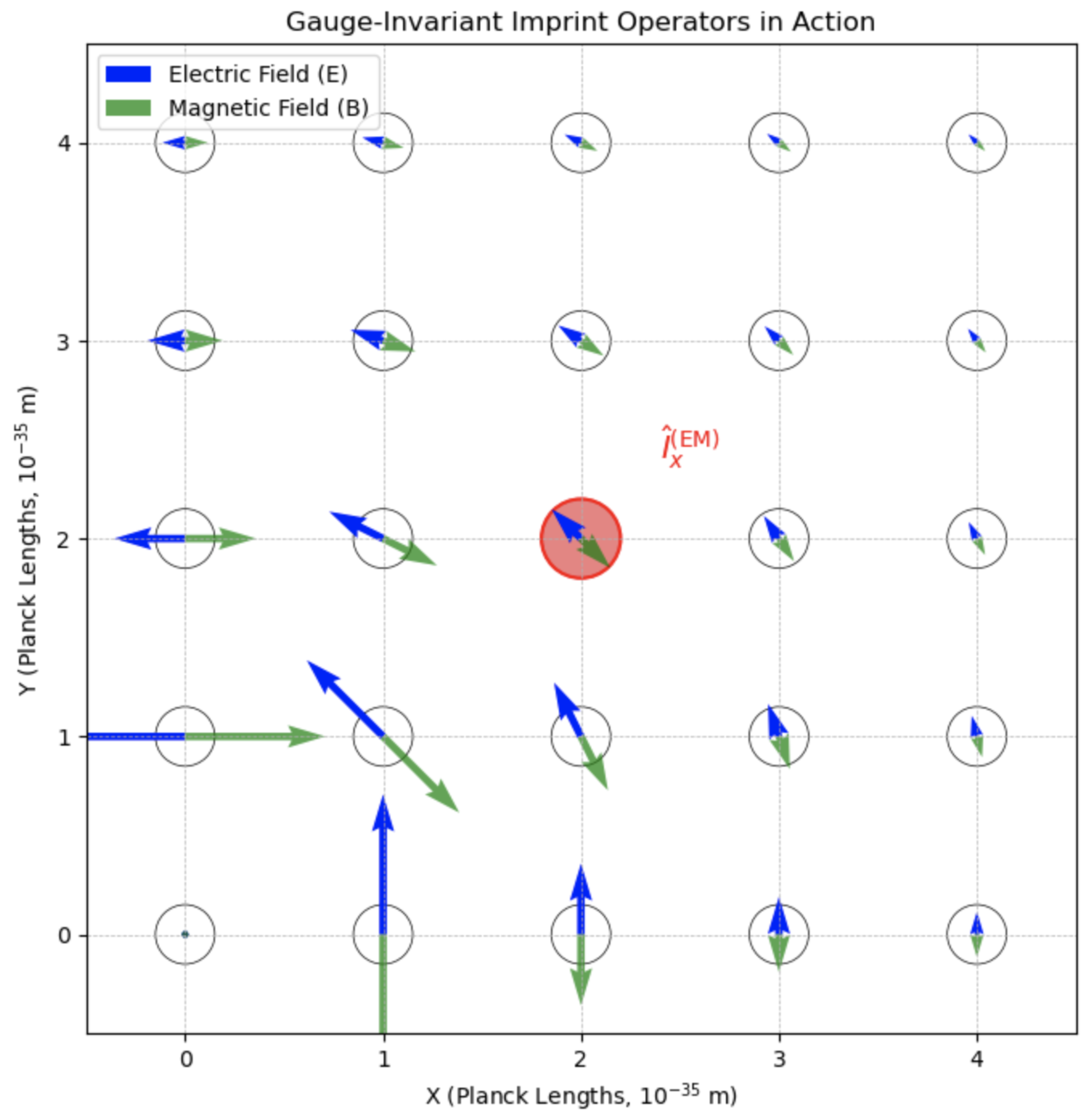

Figure 3.

Conceptual diagram illustrating how the electromagnetic field operators and QMM cell imprint operators interact through the Hamiltonian. Bidirectional arrows indicate information exchange; color codes/labels are not calculated results.

Figure 3.

Conceptual diagram illustrating how the electromagnetic field operators and QMM cell imprint operators interact through the Hamiltonian. Bidirectional arrows indicate information exchange; color codes/labels are not calculated results.

A representative form for the interaction Hamiltonian might be:

where

acts on the field degrees of freedom, while

and

act on cell

x. The ellipsis can include higher-order corrections or self-interactions if desired.

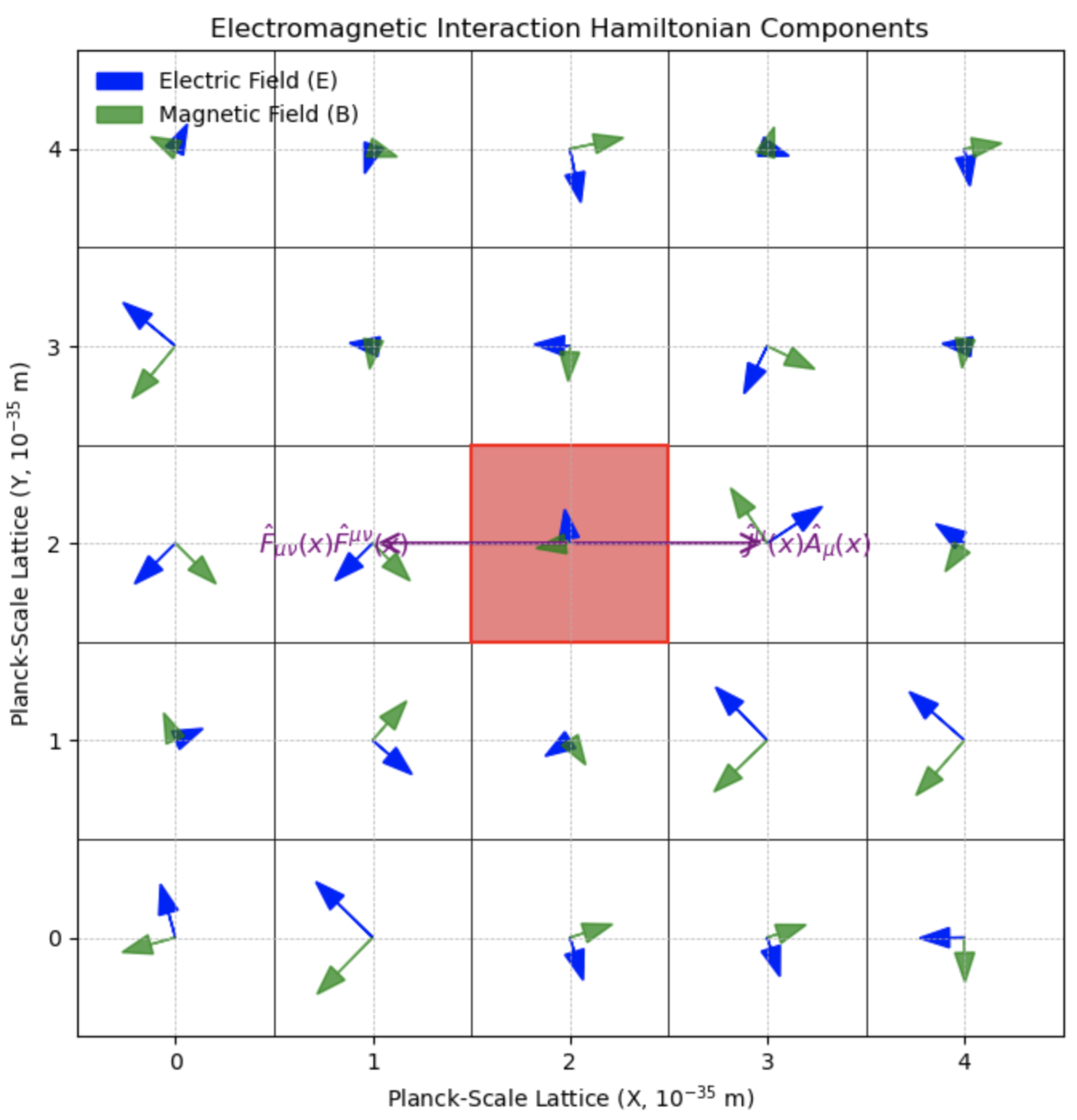

Figure 4.

Schematic breakdown of the electromagnetic interaction Hamiltonian, showing how QMM imprint operators couple with field operators at each cell.

Figure 4.

Schematic breakdown of the electromagnetic interaction Hamiltonian, showing how QMM imprint operators couple with field operators at each cell.

3.4. Preserving Unitarity, Locality, Gauge Invariance, and the Equivalence Principle

By design,

is Hermitian, so the time-evolution operator

remains unitary. Locality follows from the fact that imprint operators act only on cell

x and the local field state; nonlocal correlations can arise dynamically but only through sequential interactions across neighboring cells. Gauge invariance is upheld because the discretized operators (e.g., link variables, plaquette operators) transform properly under local U(1). The imprint operators themselves are built from gauge-covariant or invariant quantities so that no unphysical degrees of freedom are introduced.

One might worry that a fundamental discretization could conflict with the equivalence principle, which requires local inertial frames in a smooth manifold. In the QMM approach, however, local gravitational and electromagnetic degrees of freedom are encoded symmetrically at the cell level, and no preferred direction or frame is introduced at large scales. When many cells are coarse-grained to form an effective continuum, the usual local Lorentz invariance and equivalence principle emerge in the low-energy limit. Thus, although physics at the Planck scale is discrete, standard relativistic effects (including freely falling inertial observers and locally Minkowskian coordinates) remain valid in macroscopic regimes.

3.5. Implications for Charged Black Holes and QED Vacuum Structure

Extending QMM to electromagnetism suggests several possibilities:

Charged Black Hole Evaporation: In principle, a charged black hole (e.g., Reissner–Nordström) could leave electromagnetic imprints on horizon-adjacent cells. As the hole evaporates, outgoing photons and charged particles can become entangled with these imprinted states, potentially leading to non-thermal correlations in Hawking radiation. Although a detailed black hole model is not provided here, the imprint mechanism indicates a path toward preserving information about charge distributions.

Vacuum Polarization and Running Couplings: The Planck-scale discretization in QMM places a physical cutoff on momentum modes. Loop integrals in QED become finite sums, thereby altering vacuum polarization at very high energies. This might modify the running of near the Planck scale, perhaps smoothing out or preventing a Landau pole. A more rigorous renormalization-group analysis would clarify how the QMM cutoff affects coupling constants.

Cosmological Photon Fields: Early-universe fields imprinted on QMM cells could influence magnetogenesis or reionization scenarios. Subtle changes in primordial photon spectra might leave signatures in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) or large-scale structure. Detecting these small deviations would be challenging, but any observed anomaly in polarization or small-scale power could hint at Planck-scale discreteness.

3.6. Towards a Fully Unified Field Theory

Incorporating electromagnetism into QMM is a meaningful step toward a more complete theory unifying quantum gravity and gauge interactions. Further research could address:

Non-Abelian Extensions: SU(2) and SU(3) gauge groups require imprint operators that handle more complex field strength tensors and link variables. This remains an open but promising direction.

Full Standard Model Integration: To fully unify matter and interactions, quarks, leptons, and the Higgs sector must also be embedded in the QMM framework, possibly introducing flavor structure and spontaneous symmetry-breaking at the discrete level.

Dynamic Space–Time Quanta: Ultimately, one would like a mechanism that generates discrete cells dynamically instead of imposing them. Approaches akin to spin foam or causal set theory might be merged with QMM to achieve full background independence.

We have outlined how U(1) gauge fields can be merged with the QMM framework by employing link variables and gauge-invariant imprint operators that respect unitarity, locality, and local gauge symmetry. While the current formulation remains a "by-hand" discretization rather than a dynamically generated one, it opens the possibility of systematically analyzing trans-Planckian QED effects, charged black hole evaporation scenarios, and potential cosmological signals. In the next section, we discuss how these developments might manifest in physical observables and consider prospective tests of QMM-based predictions.

4. Applications to Black Hole Information, Vacuum Structure, and Cosmology

Having extended the QMM framework to include U(1) gauge fields, we now explore three contexts where electromagnetism and gravity intersect in nontrivial ways: charged black holes, vacuum polarization at trans-Planckian energies, and early-universe cosmology. While a fully dynamical treatment remains beyond the scope of this paper, these examples illustrate how the local storage of quantum information at the Planck scale could, in principle, help maintain unitarity and potentially yield small but measurable deviations from standard predictions.

4.1. Charged Black Holes and Information Retrieval

Classically, charged black holes in general relativity are described by Reissner–Nordström or Kerr–Newman solutions, characterized only by mass

M, charge

Q, and angular momentum

J. According to the no-hair theorems, other details about the collapsing matter appear lost behind the horizon. In the QMM picture, however, quantum information is

imprinted in cells near (and possibly inside) the horizon as the collapsing charged matter crosses it. For example, an imprint operator such as

can record local electromagnetic field strengths and charge-current distributions in the discrete Hilbert spaces

. This effectively supplements the macroscopic parameters with more detailed quantum information.

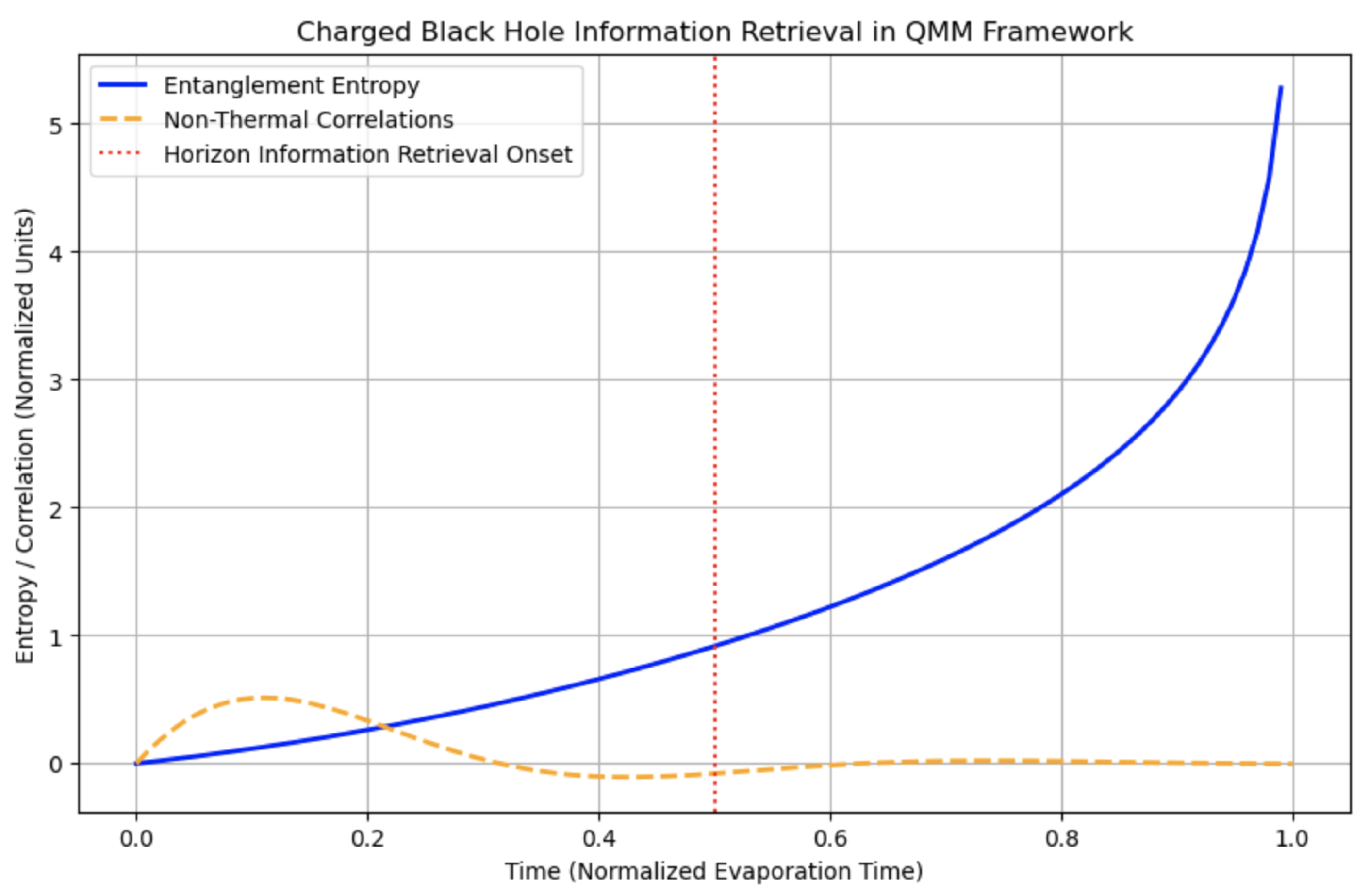

As the black hole evaporates via a Hawking-like process, the outgoing radiation (photons and charged particles) interacts with these QMM-stored imprints, possibly producing non-thermal correlations that reflect the original matter state. In a more traditional semiclassical analysis, the Hawking radiation appears nearly thermal and would seemingly erase information; here, the local QMM degrees of freedom may restore it.

Figure 5 schematically depicts how the entanglement entropy might deviate from the standard Page curve, eventually returning to zero if enough correlations are re-emitted.

Preliminary estimates suggest that the correction to entanglement entropy could be proportional to , where d is the dimension of a cell’s Hilbert space. While a rigorous proof would require simulating the entire evaporation process (beyond the current scope), the suggestion is that any discovered charge-dependent correlations in black hole radiation could signal an imprint-like mechanism at work.

4.2. Vacuum Polarization and UV Behavior

In quantum field theory, loop integrals often lead to divergences, particularly in vacuum polarization diagrams. By discretizing space–time at the Planck scale, QMM posits a physical ultraviolet (UV) cutoff around

where

is the Planck length. Consequently, momentum integrals turn into finite sums over modes associated with QMM cells, removing the classical divergences of continuum QED.

Moreover, the running of the electromagnetic coupling could be altered at high energies if the discrete cell structure modifies vacuum polarization at or near the Planck scale. One possibility is that saturates or follows a different trajectory than the usual logarithmic running, suggesting a UV-complete extension of QED free from a Landau pole. Concrete calculations, however, would require a detailed renormalization-group analysis adapted to the QMM discretization.

Additionally, QMM implies a finite number of zero-point modes per cell. This might adjust estimates of the vacuum energy density and, in principle, feed into the cosmological constant problem. While any resolution would demand an in-depth calculation, QMM’s inherent cutoff at each cell is at least a conceptually distinct way to tame infinite zero-point sums.

4.2.1. A Toy Calculation for Discrete Vacuum Polarization

To illustrate how QMM discretization regularizes loop integrals in quantum electrodynamics, we sketch a simplified one-loop vacuum polarization calculation in a discrete setting. In continuum QED, the vacuum polarization tensor for the photon field is given by an integral of the form

where

,

m is the fermion mass, and the ellipsis denotes possible additional contributions or counterterms.

In the QMM framework, space–time is discretized into Planck-scale cells, each with finite local Hilbert space dimension. Consequently, one expects momenta to be restricted to a

finite set of modes, typically bounded by

where

is the Planck length. Instead of integrating over all four-momenta in

, one sums over a discrete set

(or a suitable lattice in momentum space) with

. Symbolically,

Here

V is the (finite) volume factor associated with the reciprocal lattice spacing, ensuring proper dimensional analysis. Consequently, the continuum vacuum polarization integral (

13) becomes

where the sum is manifestly

finite (i.e., it contains only those momenta with

).

Because

is finite, the usual ultraviolet divergences of continuum QED do not appear; the loop integral is replaced by a finite sum. Physically, this corresponds to the local Hilbert space dimension imposing a cutoff at momenta

. In conventional continuum QED, the electromagnetic coupling

runs logarithmically with energy scale

, potentially leading to a Landau pole at extremely high energies. In the discrete QMM scenario, one might anticipate that

where

is a finite saturation value rather than an unbounded growth. A fully rigorous renormalization-group analysis would be required to confirm this behavior, but the toy calculation demonstrates how discretizing space–time at the Planck scale removes the usual high-momentum tail of loop integrals.

Although the discrete sum (

15) captures the essential idea of a Planck-scale cutoff, a complete treatment would:

Implement the full QMM structure of local imprint operators and gauge constraints on each cell, ensuring gauge invariance is maintained at the lattice level;

Include additional effects such as vertex corrections and higher-order diagrams that also become finite under QMM discretization;

Examine the role of gravitational degrees of freedom, which could further modify the effective cutoff or the coupling flow.

Nevertheless, this toy calculation illustrates how the QMM perspective replaces divergent integrals with finite sums, potentially offering a path to ultraviolet completeness. The key ingredient is that each Planck-scale cell has a finite-dimensional Hilbert space, capping the number of local excitations and, in turn, the maximum momentum modes that can propagate.

4.3. Early-Universe Cosmology and Primordial Fields

In standard cosmology, large-scale cosmic magnetic fields could originate from inflationary or phase-transition magnetogenesis. In a QMM setting, the Planck-scale discretization might leave imprints on these primordial electromagnetic modes. Quantum fluctuations of stored in QMM cells during or before inflation could lead to:

Small deviations in the primordial power spectrum, possibly detectable as subtle modulations of E-mode or B-mode polarization in the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

Non-Gaussian features or anisotropies arising from discrete-phase correlations among cells.

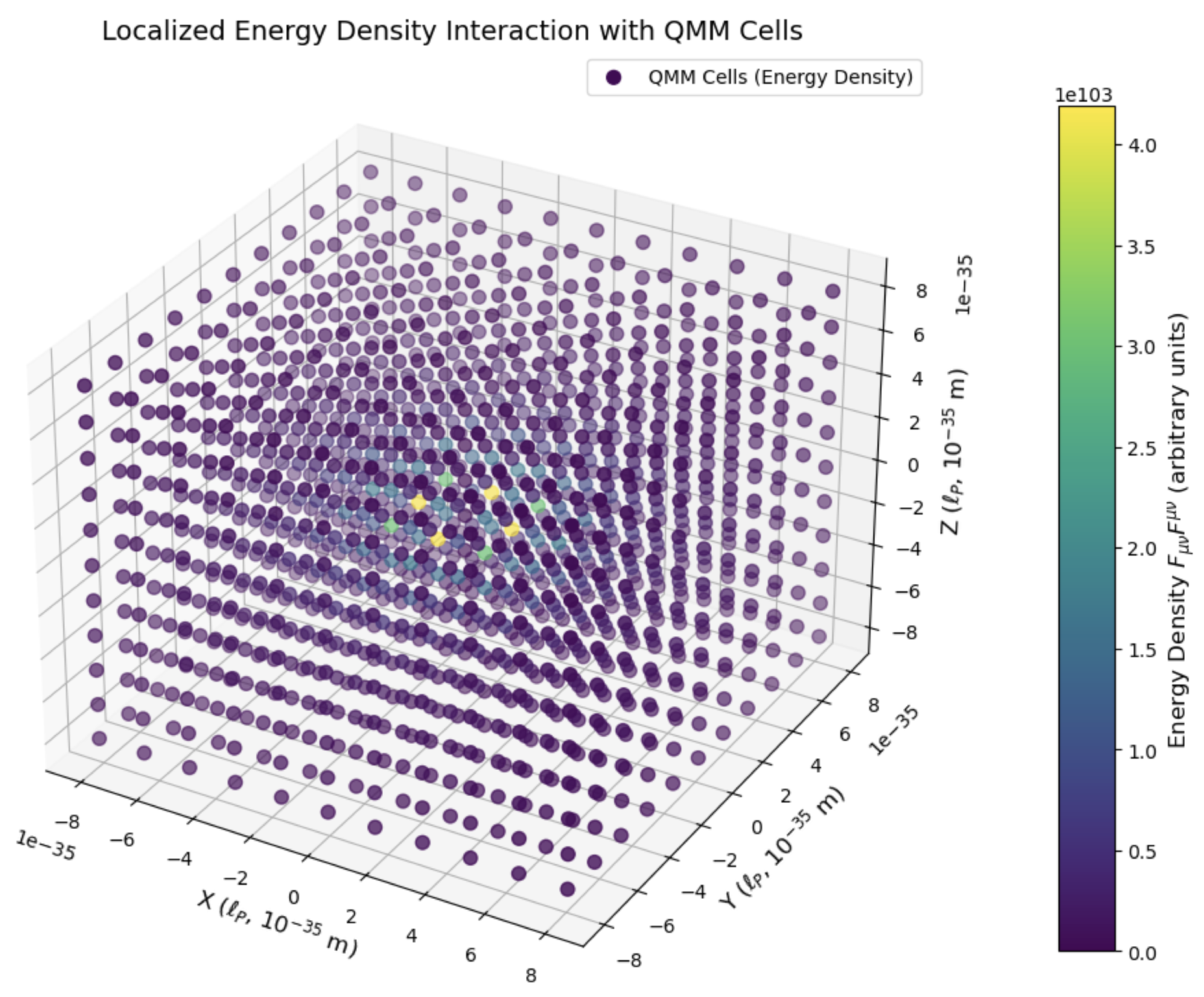

Figure 6 illustrates the concept of QMM cells seeding electromagnetic fluctuations. If the fractional deviation in the electromagnetic spectrum is on the order of

, then advanced CMB missions (e.g., LiteBIRD, CMB-S4) or 21-cm surveys might pick up traces of such effects, albeit with considerable experimental difficulty.

4.4. Analog Models and Prospects for Experimental Tests

Direct experiments at the Planck scale are currently unfeasible, but laboratory analogs could probe aspects of QMM:

Quantum Simulations of U(1) Gauge Theories: Cold-atom systems, superconducting qubits, or Rydberg arrays can emulate discretized gauge fields. By defining imprint-like operators and monitoring entanglement growth and correlations, one can examine how local storage of quantum information might emerge in a lattice-based simulation.

Analog Black Holes: Systems that mimic event horizons—e.g., sonic horizons in Bose–Einstein condensates or optical waveguide setups—generate Hawking-like emission. If the emission shows deviations from thermality consistent with local imprint-and-retrieval processes, it could give indirect credence to the QMM picture.

Although such analogs are inherently limited (due to different energy scales and backgrounds), any observed deviation patterns hinting at a local memory mechanism would be a suggestive proof of principle.

4.5. Toward a Unified QMM-Based Field Theory

Ultimately, we hope that merging QMM with gravitational and gauge degrees of freedom yields a finite, unitary theory of all interactions:

Non-Abelian Extensions: Imprint operators that handle non-Abelian field strengths (e.g., ) and non-Abelian link variables remain a key open challenge.

Full Standard Model Integration: Including quarks, leptons, and the Higgs mechanism into the QMM architecture may require discretized Yukawa couplings and finite-dimensional representations of flavor symmetries.

Dynamical Quantum Geometry: A fully background-independent approach would see the QMM discretization emerge from a deeper quantum gravity principle rather than being inserted by hand.

In this section, we have highlighted how charged black hole evaporation, vacuum polarization, and early-universe cosmology might look if the electromagnetic field is discretized via QMM. While each example requires further detailed study to produce concrete quantitative predictions, they collectively illustrate the breadth of scenarios where local Planck-scale information storage could significantly impact fundamental questions. With possible indirect signals in astrophysical observations, cosmological data, or quantum simulators, QMM provides a framework for exploring the interplay of quantum information, gravity, and gauge fields beyond the standard continuum paradigm.

5. Comparison with Existing Approaches and Theoretical Consistency

In the preceding sections, we have presented the QMM framework as a locally encoding, discretized approach to quantum gravity, where each Planck-scale cell carries a finite-dimensional Hilbert space and can store quantum information via gauge-invariant imprint operators. Here, we compare QMM with several well-known approaches to quantum gravity and the black hole information paradox, highlighting both the advantages it offers and the open challenges that remain on the path to a fully unified theory.

5.1. Holography and the Holographic Principle

The holographic principle—as realized in the AdS/CFT correspondence—asserts that bulk gravitational physics can be fully described by a boundary field theory in one fewer dimension. By contrast, QMM posits that:

Every Planck-scale cell in the bulk has a finite-dimensional Hilbert space that stores quantum information.

No reliance on asymptotic boundaries is required, which may make QMM more adaptable to cosmological spacetimes without a clear conformal boundary.

Key distinctions include:

Bulk vs. Boundary Encoding: Holographic dualities situate fundamental degrees of freedom on a boundary, whereas QMM distributes them throughout the interior (one cell per Planck volume).

Locality: The holographic map can be intrinsically nonlocal, relating degrees of freedom in the bulk to those on a boundary in ways that may obscure local causal structure. QMM aims for strictly local encoding within cells, preserving causal relations in a more direct manner.

Robustness to Asymptotic Structure: AdS/CFT presupposes asymptotically AdS spacetimes, which may not match realistic cosmologies (e.g., de Sitter). QMM’s cell-based framework, while still incomplete, is not tied to a specific boundary condition.

5.2. ER=EPR, Wormholes, and Nonlocal Mechanisms

The ER=EPR conjecture proposes that Einstein–Rosen bridges (wormholes) can be understood as geometrizations of entangled states, potentially offering a nonlocal path to recover information from black holes. QMM, by contrast:

Encodes information locally in each cell’s finite-dimensional Hilbert space, eliminating a need for geometric wormholes or other nonlocal channels.

Suggests that information retrieval occurs through local, causal interactions of imprint operators with outgoing degrees of freedom rather than through topological shortcuts.

Could, in principle, be distinguished experimentally if one found that black hole radiation correlations fit a purely local storage model rather than a wormhole-based nonlocal entanglement.

5.3. Firewalls, Complementarity, and Observer Dependence

The firewall paradox questions the smoothness of the black hole horizon by suggesting a high-energy barrier for an infalling observer, in tension with the equivalence principle. In QMM:

Planck-scale imprinting of information avoids the need for a macroscopic firewall: the energy excitations remain localized in Planck-scale cells, leaving large-scale horizons effectively smooth.

The imprint is observer-independent, since once the quantum data is recorded in QMM cells, its existence does not depend on a specific observer’s trajectory.

Unitarity is maintained by local, sequential interactions rather than any abrupt or global mechanism.

Nevertheless, a more detailed black hole horizon model would be required to show definitively how QMM reconciles infalling and distant observers’ descriptions in all scenarios.

5.4. Loop Quantum Gravity, Spin Foams, and Causal Sets

Loop quantum gravity (LQG), spin foams, and causal set theories all discretize space–time or its causal structure to handle quantum gravitational phenomena. QMM differs by:

Explicit Quantum Information Storage: Each QMM cell is not only a "quantum of geometry" but also an active memory unit that encodes field data via imprint operators.

Allowing a direct coupling to matter and gauge fields, as these degrees of freedom can be discretely imprinted into local Hilbert spaces.

Proposing an information-preserving perspective on the black hole paradox: local imprinting ensures reversible evolution in principle, even if it appears lost in semiclassical treatments.

5.5. Minimal Length Scenarios and UV Regularization

Various minimal length or generalized uncertainty principle approaches posit a fundamental length scale (often the Planck length) to regularize QFT divergences:

QMM provides a built-in UV cutoff through the finite dimension of each cell’s Hilbert space.

In principle, this finite-dimensionality can tame loop integrals by turning them into discrete sums.

Unlike a purely ad hoc momentum cutoff, QMM aims to ground the cutoff in a physical picture of Planck-scale discretization plus local quantum information storage.

5.6. Challenges, Open Questions, and Future Directions

Despite potential advantages, many key aspects remain open:

Non-Abelian Gauge Groups: SU(2), SU(3), and beyond would require more sophisticated imprint operators to capture non-Abelian self-interactions and topological properties.

Dynamical Lattice Generation: Currently, QMM cells are imposed. A fully emergent picture of discrete space–time, analogous to spin foams or causal sets, is yet to be developed.

Renormalization at Low Energies: A systematic link between QMM’s discrete high-energy regime and established low-energy effective field theory remains to be constructed, including detailed RG flow analyses.

Empirical Discrimination: Concrete observational signatures, such as subtle deviations in black hole spectra, gravitational waves, or the CMB, must be predicted with enough precision to be tested.

5.7. Advantages of QMM and the Path Ahead

QMM’s defining strengths can be summarized as follows:

A local, unitary mechanism that encodes and retrieves information without invoking nonlocal wormhole connections or holographic boundaries.

A gauge-invariant discretization scheme via imprint operators, enabling a clear coupling between gauge fields and discrete geometry.

An intrinsic UV cutoff arising naturally from the finite dimension of each cell’s Hilbert space, potentially offering a road to ultraviolet completeness.

Achieving a fully unified theory still requires demonstrating how non-Abelian fields, dynamical geometry, and all Standard Model components fit into QMM. Nonetheless, by placing quantum information storage at the heart of space–time at the Planck scale, QMM provides a novel standpoint on the black hole information paradox, cosmic singularities, and other puzzles that challenge the interface between quantum mechanics and gravity. In the following section, we discuss what observational or experimental strategies might shed light on QMM’s distinctive predictions or falsify its core assumptions.

6. Experimental and Observational Perspectives

While direct tests of Planck-scale physics remain well beyond current technological reach, the QMM framework’s discrete, locally encoded structure suggests potential observational signatures that might—under favorable conditions—deviate measurably from standard quantum field theory, general relativity, and semiclassical black hole thermodynamics. In this section, we discuss several experimental and observational strategies that could probe QMM-specific predictions. The emphasis is on conceptual avenues where QMM might differ qualitatively from other new physics scenarios, thus allowing for potential discrimination.

6.1. Non-Thermal Features in Black Hole Evaporation

A central implication of QMM is that Hawking-like radiation from black holes may carry non-thermal correlations imprinted by Planck-scale cells near the horizon. In standard semiclassical treatments, Hawking radiation appears nearly thermal, suggesting information loss (or at best very subtle correlations). Under QMM, local imprint operators can encode detailed charge and field configurations, causing outgoing quanta to exhibit deviations from strict thermality.

Back-of-the-envelope estimates suggest that if a cell’s Hilbert space has dimension d, the correction to the entanglement entropy might scale as . For modest –100, one might expect a few-percent deviation from a purely thermal spectrum. Although such small signals would be extremely challenging to observe for typical astrophysical black holes (due to their low temperature and environmental backgrounds), primordial black holes (PBHs) nearing the end of their evaporation could reach higher temperatures. Upcoming gamma-ray observatories (e.g., CTA) or advanced cosmic-ray detectors could, in principle, set constraints on or detect non-thermal spectral features from PBH evaporation.

Figure 7.

Conceptual depiction of how charged black hole formation and the associated imprinting of electromagnetic data in QMM cells can alter the Hawking radiation spectrum, leading to potential non-thermal correlations.

Figure 7.

Conceptual depiction of how charged black hole formation and the associated imprinting of electromagnetic data in QMM cells can alter the Hawking radiation spectrum, leading to potential non-thermal correlations.

Similarly, gravitational-wave observatories (LIGO, Virgo, KAGRA, LISA, the Einstein Telescope, Cosmic Explorer) may one day observe subtle modifications in ringdown signals following black hole mergers. If QMM effects introduce small phase shifts or amplitude modulations in the quasi-normal mode spectrum, these might be detectable as advanced detectors reach higher precision. While pinning down such tiny signatures remains a formidable challenge, any observed anomalies could hint at horizon-scale quantum memory.

6.2. Cosmic Microwave Background and Large-Scale Structure

At the cosmological scale, QMM’s discretization of electromagnetism might modify primordial electromagnetic fluctuations in the early universe. Such modifications could leave imprints in:

CMB Polarization and Non-Gaussianity: If QMM discretization alters vacuum modes or magnetogenesis, the E-mode or B-mode polarization of the CMB might reveal small deviations from standard inflationary predictions. Non-Gaussian correlations or scale-dependent anomalies in the power spectrum could emerge.

Primordial Magnetic Fields: QMM-induced changes to the generation or evolution of cosmic magnetic fields could affect their coherence length, strength, or polarization properties. Faraday rotation measurements and gamma-ray observations of blazar halos might then detect signatures of such changes.

Future missions (LiteBIRD, CMB-S4, high-resolution 21-cm surveys) might be sensitive enough to observe subtle effects at the level, where x depends on model details. Though detecting these small signals would require precise modeling and data analysis, even upper limits could place constraints on QMM parameter spaces.

6.3. Laboratory Analog Experiments and Quantum Simulators

Although direct Planck-scale experiments are unattainable, lab-based analog models can probe certain mechanisms central to QMM:

Sonic/Optical Horizon Analogs: In Bose–Einstein condensates or waveguide arrays, one can create effective horizons that emit Hawking-like radiation. Introducing local "imprint-like" couplings might replicate aspects of QMM’s discrete information storage. Deviations from thermal emission in such systems could qualitatively mimic QMM-based retrieval mechanisms.

Quantum Simulation of Lattice Gauge Theories: Platforms such as Rydberg arrays, trapped ions, or superconducting qubit circuits can emulate U(1) lattice gauge theories. By programming interaction terms reminiscent of QMM imprint operators, one can study entanglement transfer and information retention on a discrete lattice. Observed correlation patterns could serve as a testbed for the QMM concept of local memory in each cell.

While these analog experiments cannot directly replicate Planck-scale curvature or energies, they can provide valuable insight into the dynamical role of local quantum information storage and retrieval.

6.4. Distinguishing QMM Effects from Other New Physics

Any observed anomalies in black hole radiation or cosmological data could stem from various beyond–standard-model theories, including ER=EPR wormholes, extra dimensions, or modified gravity frameworks. The hallmark of QMM is a strictly local information storage and gauge-invariant discretization:

Nonlocal or higher-dimensional models often predict global entanglement patterns or novel resonances. QMM’s signals, by contrast, would typically reflect local, cell-by-cell correlations that do not rely on hidden dimensions or wormholes.

Identifying a characteristic discrete imprint signature (e.g., a –type correction scaling) could help discriminate QMM from alternative pictures that either do not introduce a finite Hilbert-space dimension per cell or rely on long-range entanglement.

6.5. Long-Term Outlook: Indirect Probes and Future Missions

Despite the immense challenges, combining astrophysical observations (e.g., PBH evaporation or ringdown waveforms), precision cosmology (CMB and 21-cm mapping), and lab-based analog experiments offers a multi-channel approach to testing key QMM ideas. Even null results that constrain the size of non-thermal deviations or power-spectrum modifications can limit QMM parameter ranges (for instance, bounding the dimension d of each cell’s Hilbert space).

Over time, consistent evidence of local imprint correlations in multiple arenas—from black hole radiation to cosmological signals—would strengthen the case for a Planck-scale quantum memory mechanism. If no such signatures are found, QMM might require substantial revision or be subsumed by competing frameworks. In either case, the approach of treating space–time as a dynamic information reservoir provides a compelling lens for future quantum gravity research.

7. Conclusion

We have presented an extended Quantum Memory Matrix framework that incorporates electromagnetism into a discretized quantum gravitational setting by assigning finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces to Planck-scale cells. Within this approach, both gravitational and electromagnetic interactions can leave imprints at the Planck scale, locally encoding key quantum information. As a result, unitarity can be preserved through these imprint operators rather than relying on nonlocal processes such as wormhole-mediated correlations.

By carefully embedding U(1) gauge symmetry via link variables and gauge-invariant imprint operators, we propose a mechanism that could maintain unitarity even in processes like charged black hole evaporation, where detailed electromagnetic information is recorded and later revealed in emitted radiation. In addition, the discrete structure of QMM inherently introduces a Planck-scale cutoff, potentially alleviating high-energy divergences in loop integrals and altering the running of coupling constants at trans-Planckian energies.

While our outline provides a conceptual foundation and indicates how non-thermal features in black hole radiation, modified vacuum polarization, or subtle cosmological signatures might arise, significant open questions remain. Future work must address:

Non-Abelian Gauge Groups and the Full Standard Model: Extending QMM to SU(2), SU(3), and the entire particle spectrum is crucial for a fully unified picture.

Dynamical Discretization: Developing a background-independent theory where the Planck-scale cell structure emerges rather than is imposed.

Detailed Renormalization and Observational Predictions: Mapping discrete QMM states to continuum physics and producing testable predictions for observational data.

We anticipate that ongoing theoretical advances, combined with increasingly sensitive observations and lab-based quantum simulations, will help clarify the viability of QMM. Regardless of the outcome, framing space–time as a local quantum information repository opens novel perspectives on phenomena ranging from black hole evaporation to early-universe magnetogenesis, and offers a distinctive path toward reconciling gravity with the principles of quantum mechanics.

Author Contributions

F.N. developed the research concept and prepared the initial manuscript draft. V.V. and E.M. critically reviewed the manuscript, contributed to the formalism, and aided in its revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. All theoretical results are derived from the proposed Quantum Memory Matrix framework, and no datasets are associated with this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. A Minimal Toy Model for Black Hole Information Retrieval

In this appendix, we present a simplified one-dimensional horizon model illustrating how imprint operators in the Quantum Memory Matrix (QMM) framework could enable unitarity-preserving black hole evaporation at a purely conceptual level. This toy setup is not a realistic black hole, but it captures essential features: a horizon-like boundary, infalling modes, and an outflow of radiation that can become entangled with Planck-scale cells.

Appendix A.1. 1+1 Dimensional Rindler-Like Horizon Setup

Consider a 1+1 dimensional lattice with coordinate sites indexed by , and let represent the "horizon" region. We split the lattice into:

Although not a true black hole, we treat

as a boundary beyond which infalling modes cannot return, akin to a Rindler horizon. In QMM, each cell

x has a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

of dimension

, and a global vacuum-like reference state

as discussed in

Section 2.

Appendix A.2. Imprint Operators and Local Interactions

When a matter field mode

propagates from

into the horizon region at

, we posit a local

imprint operator acting on

This operator stores the "quantum imprint" of the infalling mode in cell 0:

where

is a coupling constant. Over time, additional cells with

may similarly store subsequent infalling data.

To simulate Hawking-like emission, we introduce an "outflow" field that can carry information away from the horizon (cells with ). As it interacts with the imprint operators, may become entangled with the stored states in near the horizon.

Appendix A.3. Sketch of Entanglement Entropy and ΔS∼ln(d)

Let d be the dimension of each horizon cell’s Hilbert space ( for simplicity). In a highly idealized scenario, one can model the infalling matter as depositing one qubit (or qudit) of information each time step into cell , then the outflow interacts with that cell, picking up a correlation phase.

Late-Time Entropy Growth.

Initially, the total system (infall+outflow+cells) is nearly unentangled. After many steps:

Cell plus interior cells each store distinct qudit states from repeated infall,

Outflow modes have partial entanglement with these stored states.

A naive semiclassical analysis (neglecting QMM) might yield an ever-increasing entanglement entropy of the outflow, suggesting information loss. However, once the cell saturates its local dimension d, no further new states can be stored in cell 0 without significantly altering existing stored data. This saturation effect leads to an eventual turnover in the outflow’s entanglement entropy.

Logarithmic Correction.

If cell 0 can hold at most

qubits, the

maximum entanglement entropy contributed by that cell is

(up to a multiplicative constant for the chosen log base). Hence the total correction to the black hole (or horizon) entropy from cell

is on the order of

. For a chain of

N cells behind the horizon, one might argue that

though

N itself might scale with horizon area in more realistic geometries.

Effective Unitary Evaporation.

Because each cell can eventually re-transfer stored data to outflow modes (via repeated imprint interactions), the global evolution remains unitary. By the time all infall quanta have re-emerged in , the net entanglement entropy of the external radiation plus interior cells can return to near zero, restoring a Page-curve–like behavior. In essence, the discrete horizon cells act like finite “quantum memory slots,” preventing unbounded growth of entropy and enabling eventual retrieval of information in the outgoing modes.

Appendix A.4. Discussion and Limitations

This 1+1 dimensional toy model is far from a realistic black hole. It lacks true curvature effects, gravitational collapse, or a dynamically changing horizon. Nonetheless, it illustrates how:

Finite-dimensional imprint operators at each cell can store infalling states;

Outgoing radiation modes can retrieve that stored data, leading to non-thermal correlations;

Entanglement entropy can exhibit a –type cap for each cell, aligning with the idea that storing more than qubits of quantum information in a single cell is impossible.

While merely indicative, such minimal examples clarify how the QMM principle of local Planck-scale memory might avert the conventional "lost information" scenario in black hole evaporation. A complete analysis in higher dimensions, coupled with gravitational dynamics and multi-cell horizon models, is left for future work. Nonetheless, this simplified case captures the essential mechanism by which finite-dimensional cells can store and ultimately re-release quantum data, preserving global unitarity in extreme conditions.

References

- Rovelli, C. Loop Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 1998, 1, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background Independent Quantum Gravity: A Status Report. Class. Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53–R152. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Black Hole Entropy from Loop Quantum Gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3288–3291. [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Pawlowski, T.; Singh, P. Quantum Nature of the Big Bang: Improved Dynamics. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 74, 084003. [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. String Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998.

- Maldacena, J. The Large-N Limit of Superconformal Field Theories and Supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 231–252. [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B.; Lippert, M. The Information Paradox and the Black Hole Partition Function. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 76, 024006. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Ultraviolet Divergences in Quantum Theories of Gravitation. In General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey; Hawking, S.W., Israel, W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979; pp. 790–831.

- Reuter, M.; Saueressig, F. Renormalization Group Flow of Quantum Einstein Gravity in the Einstein-Hilbert Truncation. Phys. Rev. D 1998, 65, 065016. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Breakdown of Predictability in Gravitational Collapse. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 2460–2473. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G. Notes on Black-Hole Evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 870–892. [CrossRef]

- Preskill, J. Do Black Holes Destroy Information? Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 1992, 1, 237–247. [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional Reduction in Quantum Gravity. Conf. Proc. C 1993, 930308, 284–296. [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The World as a Hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Marolf, D.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Black Holes: Complementarity or Firewalls? J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 62. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.D. The Fuzzball Proposal for Black Holes: An Elementary Review. Fortschr. Phys. 2005, 53, 793–827. [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool Horizons for Entangled Black Holes. Fortschr. Phys. 2013, 61, 781–811. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Brasher, R.; Marx, E. The Quantum Memory Matrix: A Unified Framework for the Black Hole Information Paradox. Entropy 2024, 26, 1039. [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F.; Marx, E.; Vinokur, V. Extending the QMM Framework to the Strong and Weak Interactions. Entropy 2025, 27, 153.

- Peskin, M.E.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995.

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 1: Foundations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995.

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1995.

- Dyson, F.J. Divergent Series in Quantum Electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. 1952, 85, 631–632. [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, L.; Koul, R.K.; Lee, J.; Sorkin, R.D. A Quantum Source of Entropy for Black Holes. Phys. Rev. D 1987, 34, 373–383. [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. Minimal Length Scale Scenarios for Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativity 2013, 16, 2. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.G. Confinement of Quarks. Physical Review D 1974, 10, 2445–2459. [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. On Infinite Direct Products. Ann. Math. 1939, 40, 149–??.

- Kadison, R.V.; Ringrose, J.R. Fundamentals of the Theory of Operator Algebras, Vols. I–IV; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983.

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Projective techniques and functional integration for gauge theories. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 2170–2191.

- Haag, R. Local Quantum Physics: Fields, Particles, Algebras, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).