1. Introduction

Unoccupied Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), commonly referred to as drones, have emerged as powerful tools across various applications, including military operations [1], commercial industries, and agriculture [2,3]. A UAV is an aircraft that operates without a human pilot onboard, instead being remotely controlled or operating autonomously through pre-programmed flight paths and artificial intelligence-based navigation systems. Equipped with sensors, cameras, and communication systems, UAVs can perform a wide range of tasks that were once limited to manned aircraft, offering cost-effective, flexible, and accessible solutions for aerial operations.

UAV technology has rapidly advanced and become accessible for civilian applications. Today, drones are used in industries such as agriculture, logistics, filmmaking [4], environmental monitoring [5], and infrastructure inspection[6,7]. Their ability to capture real-time data, reach inaccessible locations, and perform automated tasks has positioned them as valuable assets across multiple sectors.

In recent years, UAVs have also gained significant attention in education [8], offering new ways to enhance learning experiences through hands-on, technology-driven applications.

Integrating UAVs into educational settings has introduced an innovative approach to teaching subjects such as engineering, computer science, and environmental studies. Drones provide students with experiential learning opportunities, allowing them to engage in real-world applications of concepts like aerodynamics, coding, and data analysis. Moreover, UAVs encourage interdisciplinary learning by bridging technical subjects with creative fields like digital media, geography, and environmental research. As drone technology becomes more advanced and accessible, it presents a unique opportunity to cultivate critical skills such as problem-solving, teamwork, and innovation among students.

Despite the growing adoption of UAVs in education, the landscape of drone-based learning platforms remains diverse, with various options available for different levels of instruction and application areas. Some UAV platforms focus on introductory programming and flight mechanics, while others emphasize autonomous navigation, machine learning integration, or specialized applications like aerial mapping and environmental sensing. Understanding the capabilities, limitations, and effectiveness of different educational UAV platforms is essential for educators and institutions aiming to incorporate drones into their curricula.

This paper analyzes various UAV platforms designed for educational use, examining their features, usability, and learning outcomes. By evaluating the strengths and challenges of different drone-based learning tools, this study offers insights into the best approaches for integrating UAV technology into education, ensuring that students and educators can maximize the benefits of this emerging technology.

2. Drone Platforms for Education

Prior research has indicated the substantial benefits of integrating robotics into the curriculum as early as the 8th grade [9]. Robotics engages the students in a creative and practical viewpoint, allowing them to conceive situations and solutions beyond theoretical knowledge and apply them to real-world applications. UAVs can take these benefits further as they have the novelty of being airborne and represent an advanced culmination of the robotics field with their array of sensors, physical structure, and abilities. Integrating UAV awareness in high school and college education through two primary methods is possible. Using simulation platforms is the first method [10]. Often, the first step involves testing the created code in a sandbox environment. Modern-day simulators offer intuitive features such as no-code mission creation, side-by-side action-reaction results, and step-by-step learning modules that can be easily adapted in a classroom environment.

The second method is using UAV hardware models that have been curated explicitly with student education in focus. These user-friendly UAV platforms integrate safety features such as break-resistant materials, soft propellors, propellor guards, and modular builds, ensuring a secure learning environment. Students can explore real-time data collection, geographical mapping, and environmental monitoring with built-in cameras and sensors. These platforms foster hands-on learning in STEM subjects, allowing students to understand complex concepts through interactive experiences. The current market has multiple such platforms that have been created, ready to cater to classroom needs.

They come at various price points and are equipped with competitive features. As such, choosing the right platform for a classroom can be challenging. The authors acknowledge that selecting an EDU platform can be highly subjective based on program budget, needs, and learning objectives. As such, this study focuses on providing a detailed comparison and fact sheet for the three popular drone-based EDU platforms rather than scoring them on a standard scale. The three platforms are the Tello EDU drone from DJI, the CoDrone EDU platform from Robolink, and the Crazyflie drone from Bitcraze.

Figure 1 shows a new model of the Robolink CoDrone EDU platform flying outdoors at a height of ∼25 meters in the presence of 2 m/s winds.

The drones are compared over several factors, such as hardware, capability, physical facts, usage, and support characteristics.

2.1. Platform and Company Peripherals

The three platforms are competitively priced in the US market. They are also supported by a strong and active community. DJI and Robolink also offer additional vehicle types, such as other drone platforms and ground vehicles.

Table 1 highlights some high level information for the three platforms.

2.2. Hardware

Table 2 compares the three platforms with regards to their hardware characteristics. The drone platforms must be built of robust materials to allow students to experiment freely without fear of constant damage to hardware. Another factor is having a modular build for these drones, so the entire platform does not need to be replaced if one component is damaged. Replacement parts can be ordered from the manufacturer and swapped with the damaged part, keeping overall costs in check. Modular builds allow specific parts to be easily upgraded, allowing the unit to keep pace with curriculum objectives and research. The DJI Tello falls back in this regard with a unibody build. The propellers and motors are the only two components that can be swapped. The battery is removable on all three platforms. The Robolink CoDrone and the Crazyflie are modular to a larger extent, allowing additional component replacement and upgrades. The Crazyflie has expansion decks that can be added to the drone to improve capabilities. Radio modules and processing units can also be swapped. The CoDrone has a higher replaceability and repairability rating than the Tello but has not featured any expansion decks. Sensor customization is limited, as additional sensors cannot be added. The hardware of the CoDrone, unlike the Crazyflie, is also closed source. However, due to its forward-facing camera, the Tello has a feature that is not standard with the other two platforms. It offers a live 720 pixel resolution flight view where the drone can stream its forward-facing camera view directly to the users’ control device.

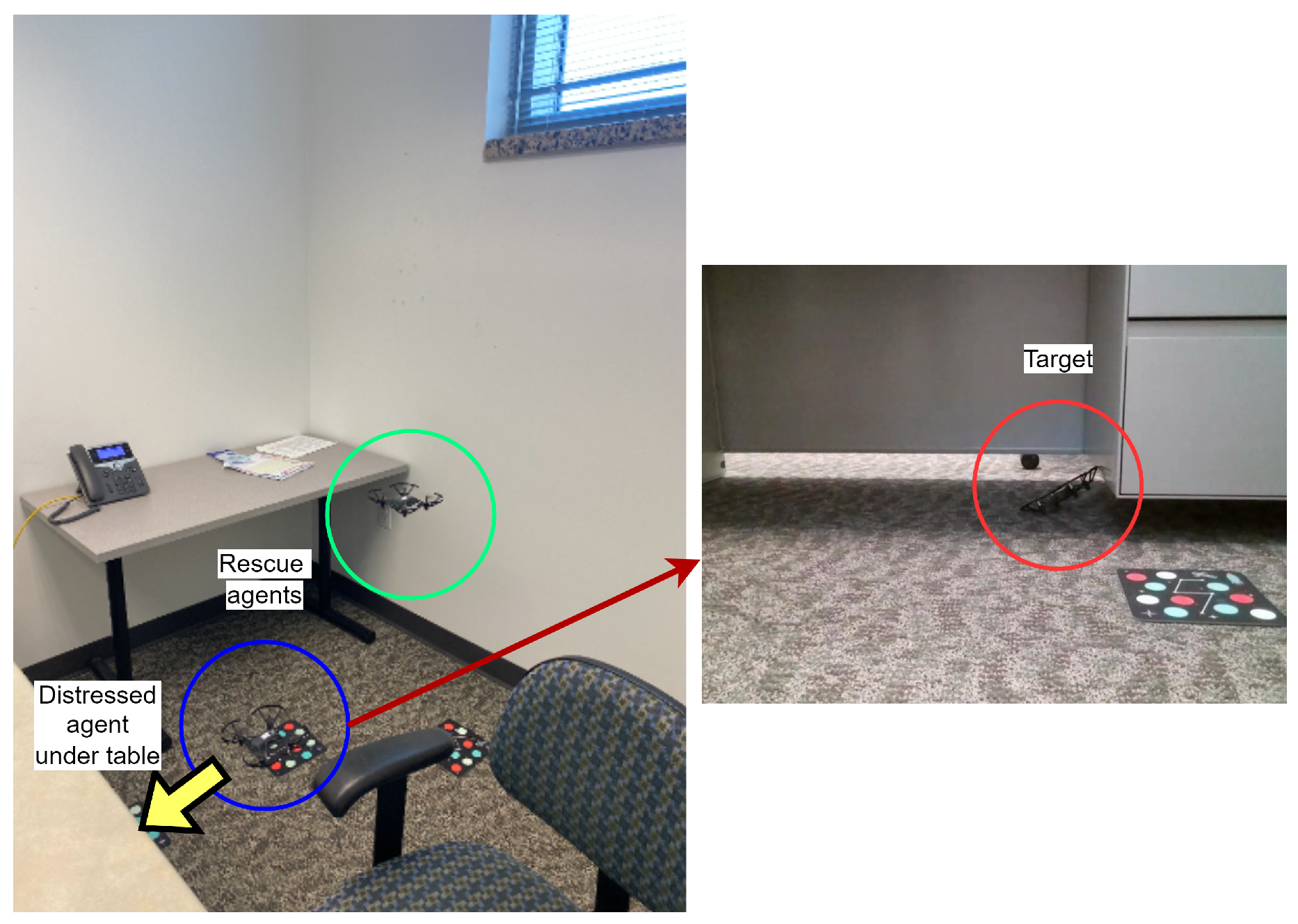

Figure 2 shows a use-case scenario of the live view from the DJI Tello, where the authors used a rescuer agent’s camera feed to search for drone agents in distress [11].

The Tello has decent camera specifications for an inexpensive drone. Multiple project possibilities exist for using Tello’s camera and live view for applications such as marker recognition and navigation, object detection [13], tracking [14], and target following.

Table 3 outlines the Tello forward-facing camera specifications.

It is worth noting that while Crazyflie 2.X uses brushed DC motors, Bitcraze has also released a newer version, Crazyflie 2.1, which uses brushless DC motors. These offer improved efficiency, longer flight times, and higher thrust. The specifications outlined in this study refer to the newer model. While only the CoDrone comes with a controller in the box, the Crazyflie and the Tello have a mobile application for iOS and Android that can control the drone. Specific Bluetooth gamepad controllers can also be used with the Tello and the Crazyflie. The CoDrone platform does not support direct connection with a phone. However, all three platforms can be connected to a laptop computer to control them. In such scenarios, web-based tools such as Blockly are suitable for controlling these drones.

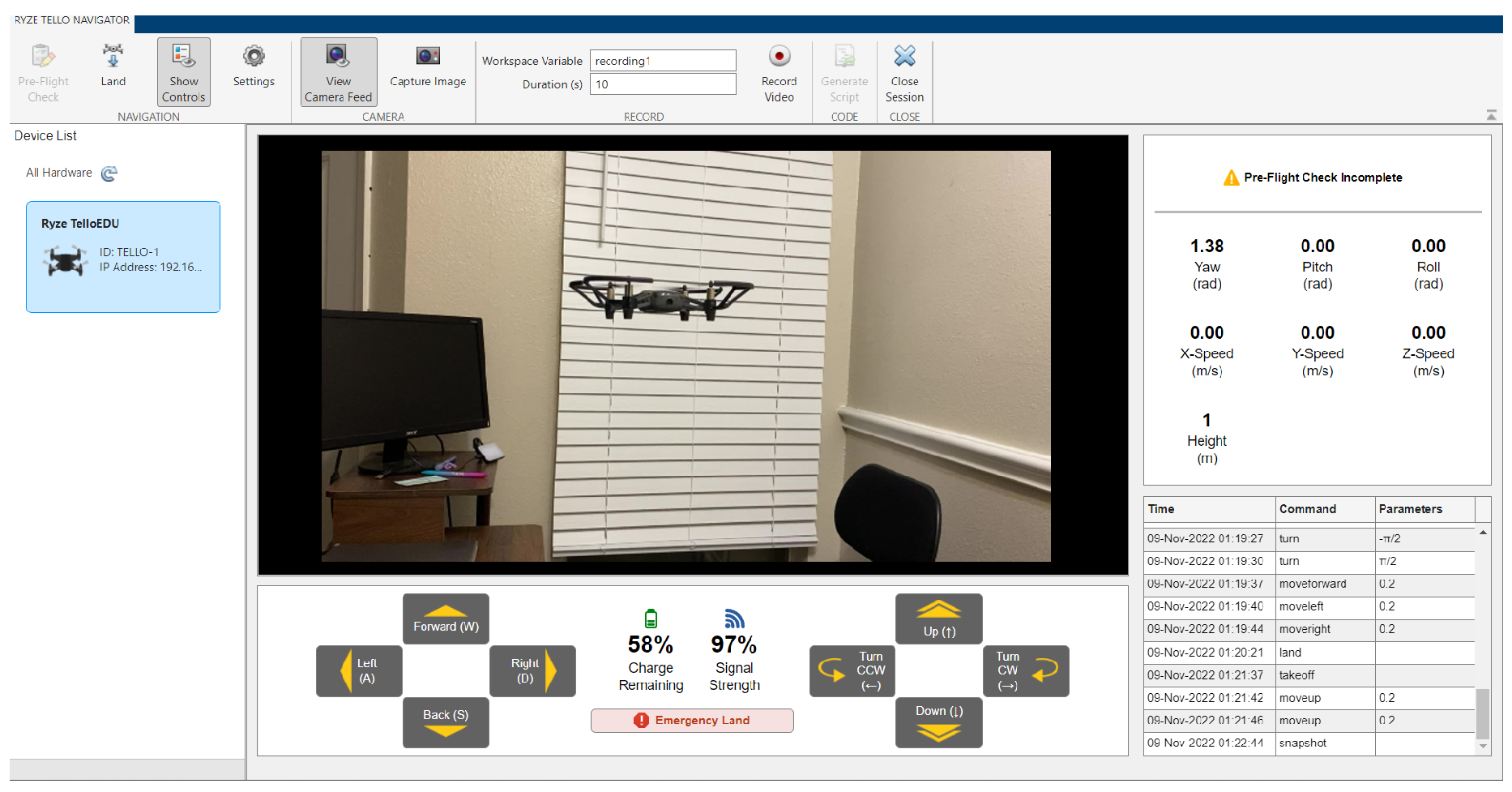

Additionally, third-party tools like MATLAB support drone integration and control. For example, MATLAB has an independent support package for connecting and controlling Tello drones. With multiple features and an informative GUI, it is an ideal way to code Tello drones and create additional applications for them.

Figure 3 shows a view from the MATLAB support package to connect and control Tello drones.

None of the three platforms can use GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System). However, there are some interesting workarounds for this shortcoming.

The Crazyflie has two methods for positioning. One is the Loco positioning system, which consists of anchors and base stations. The anchors act like satellites in a GPS (Global Positioning System) system, emitting radio signals received by the tag. The system can function in (TWR) Two-Way Ranging, TDoA 2 (Time Difference of Arrival 2) or TDoA 3 (Time Difference of Arrival 3) modes. The anchors and tags exchange radio signals. The system measures the time it takes for signals to travel between anchors and tags, which allows it to calculate distances. Using the distances from multiple anchors, the tag on the Crazyflie calculates its 3D position. This happens onboard without the need for an external computer. With precise position information, the Crazyflie can perform autonomous flight tasks, such as following waypoints, navigating mazes, or even flying in formations with other Crazyflies.

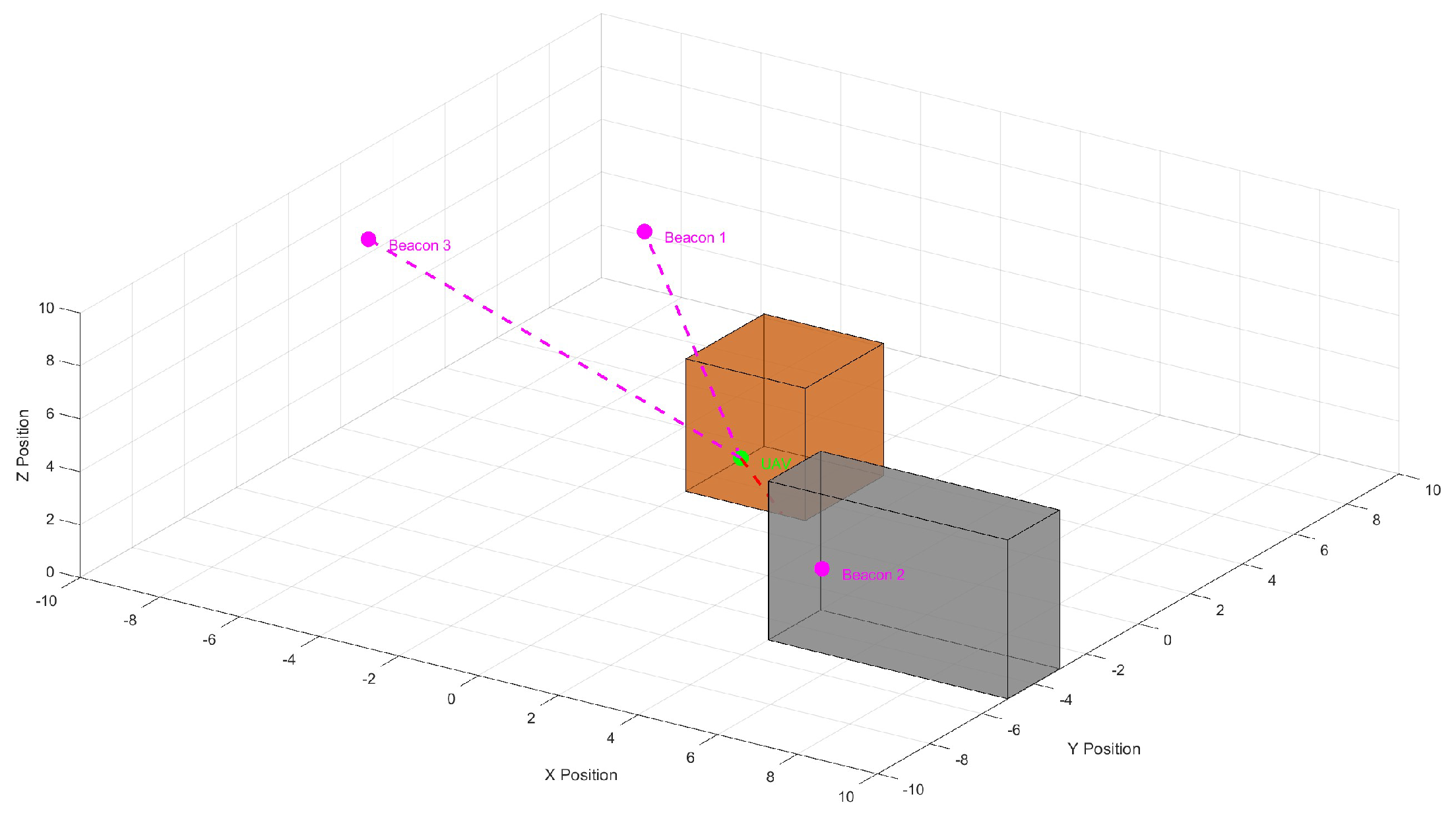

The lighthouse system relies on Lighthouse base stations. They emit sweeping infrared laser beams across the room. The Crazyflie needs the Lighthouse positioning deck attached. This deck has photodiodes that detect the laser sweeps from the base stations. When the laser beams hit the photodiodes on the Crazyflie, the system measures the precise angle between the base station and the receiver. By having multiple receivers on the Lighthouse deck (usually four), the Crazyflie can calculate its position and orientation with respect to the base stations. Like the Loco system, this calculation also happens onboard the Crazyflie, eliminating the need for communication with an external computer. However, both these systems do not come standard with the platform and must be purchased separately. There are also considerations such as line of sight issues, limited range, and need for calibration. Both active and passive light beacons face these issues.

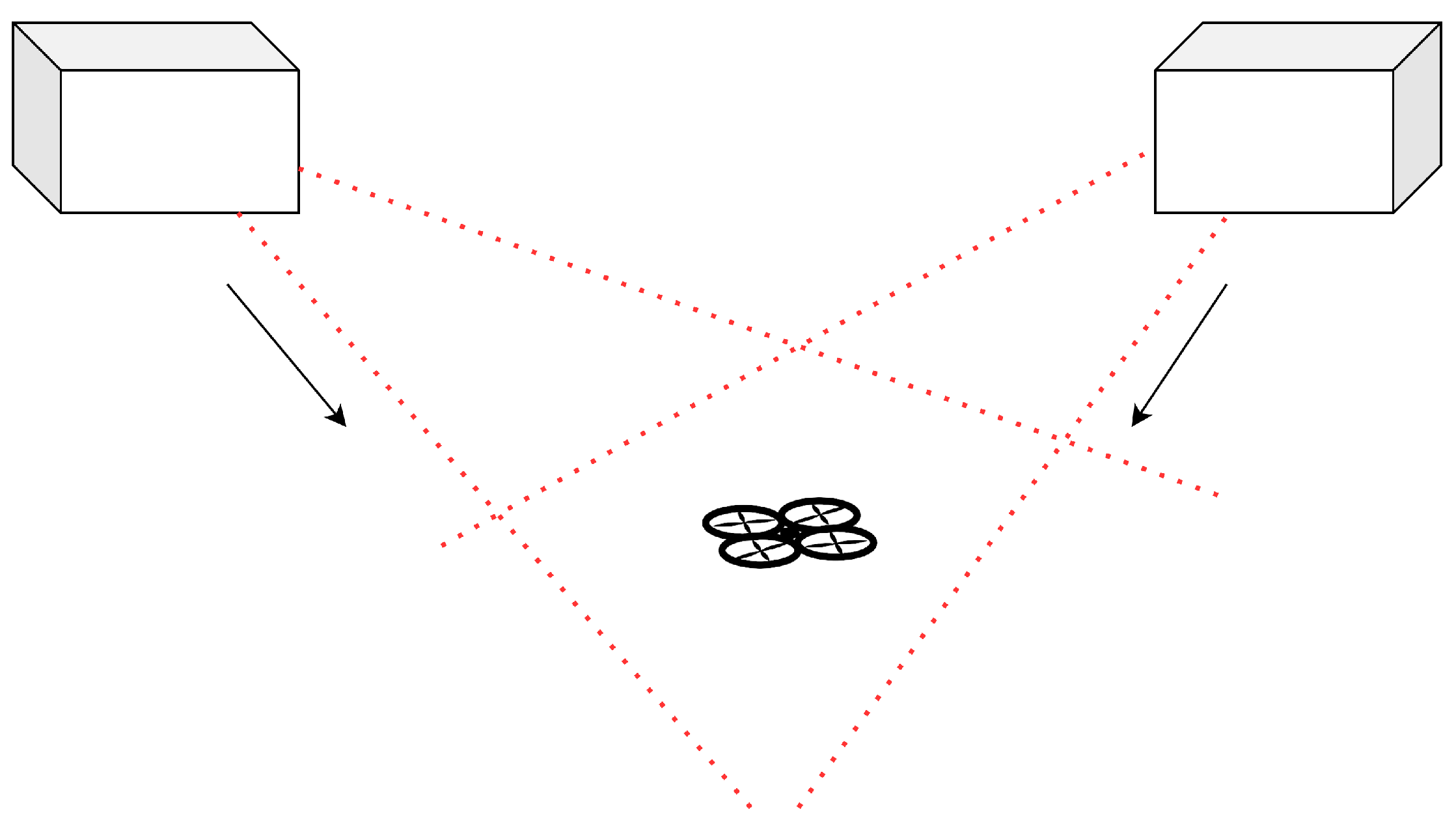

Figure 4 shows a common issue with beacons. Beacon 2 is behind an obstacle and cannot transmit information to the UAV (shown by the green sphere). Beacons 1 and 3 transmit information to the UAV; however, if the UAV moves farther out of the LoS (Line of Sight) of Beacon 3, it may lose access to the information that Beacon 3 is transmitting.

Figure 5 depicts an illustration of the lighthouse system that Crazyflie uses for positioning.

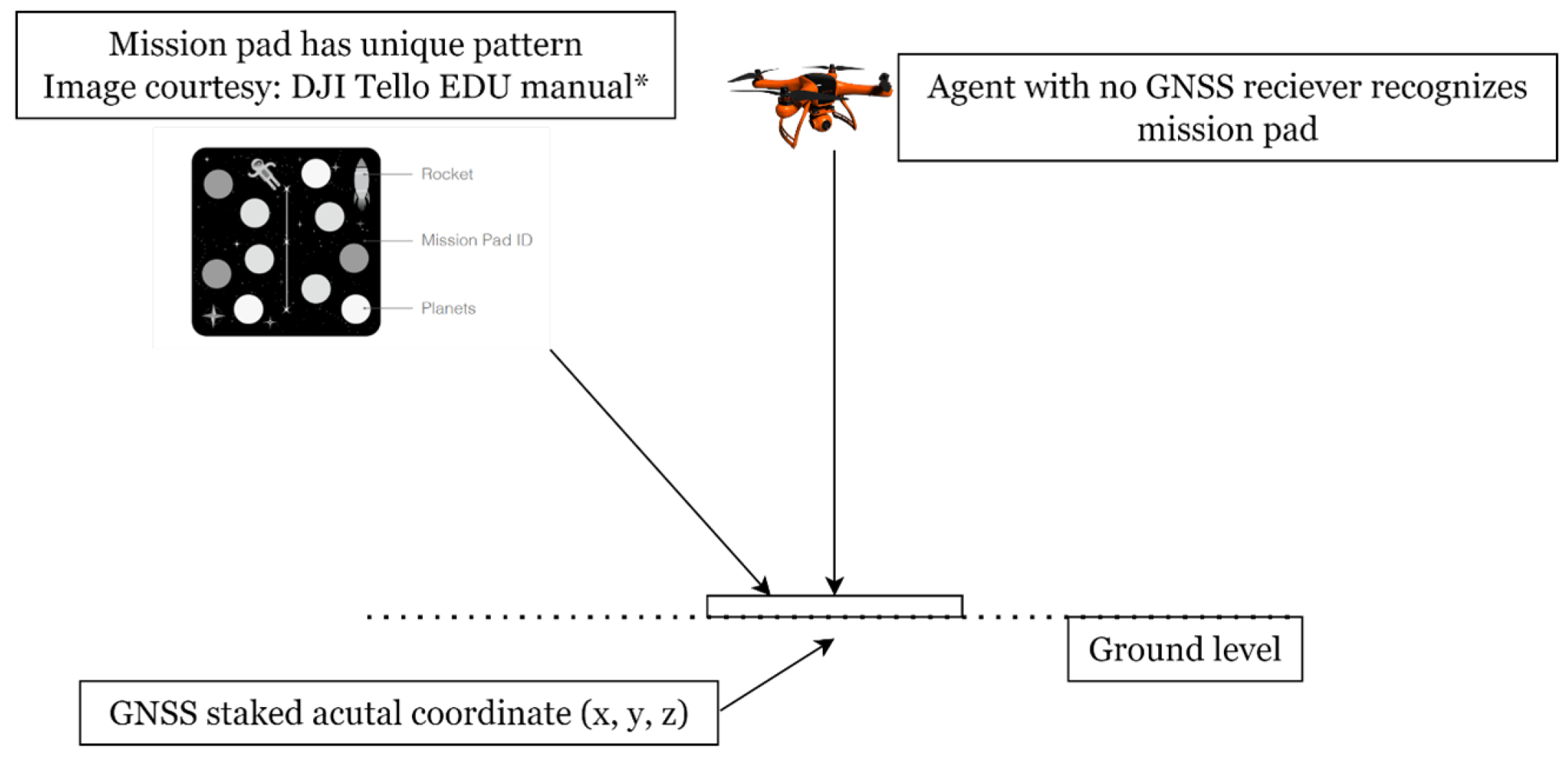

Despite lacking a GNSS receiver, there is a novel workaround for providing Tello drones with local positioning and global GNSS coordinates. This method is relatively cost-effective but has limitations in terms of range. The DJI Tello comes with standard ground mission pads that the downward-pointing sensor can recognize. The Tello uses these pads and the Visual Positioning System to localize and orient itself. By placing these pads on pre-decided local or staked GNSS global coordinates, it is possible to use the tellopy library and create an overlay map of the coordinates and the mission pad locations on the controlling computer. Since each pad is uniquely designated in the created map, once the Tello recognizes the mission pad, the information can be compared to the coordinate overlay map, and the drone gets the coordinate information specific to the recognized mission pad.

Figure 6 shows the workflow for this described scenario.

2.3. Capability and Physical Facts

Table 4 presents a comparison of the physical characteristics and capabilities of the three platforms. An important ability in these EDU platforms is swarm support. UAV swarms consist of multiple UAV agents working in tandem, communicating with each other, often through an established hierarchy [15]. UAV swarms are increasingly used in applications to enhance the temporal efficiency and data collection capabilities of drones.

Figure 7 shows two agents from a Robolink and Tello swarm working in tandem to locate a missing agent from the swarm in an indoor environment [11,12].

While the Tello and Robolink use downward-facing sensors to support physical ground-based markers, the Crazyflie does not have this as standard out-of-the-box support.

2.4. Usage and Support

Table 5 addresses the usage and support characteristics of the three platforms. The Tello and the Crazyflie have mobile applications to control the drones. The CoDrone platform does not. The presence of an official mobile app platform provides a convenience factor for drone usage. It also provides the user with additional ways to control the drone if the controller is unavailable. Cost-wise, the Tello seems to have chosen not to include the controller as a standard with the drone, instead pushing the user to rely on their mobile computing devices to control the drone. Several simulation platforms have also incorporated the ability to simulate popular drone platforms in simulation scenarios, making it easier to conduct experiments on the drones in simulation before they are tried on the hardware platform. This reduces the risk of failure and keeps costs in check. There is no direct simulator platform support for the Tello and the Robolink. Commercial versions of other DJI drones, such as the DJI Mavic, can be simulated on popular platforms such as the Webots simulator (link: https://cyberbotics.com). The Crazyflie is available as a drag-and-drop module in Webots.

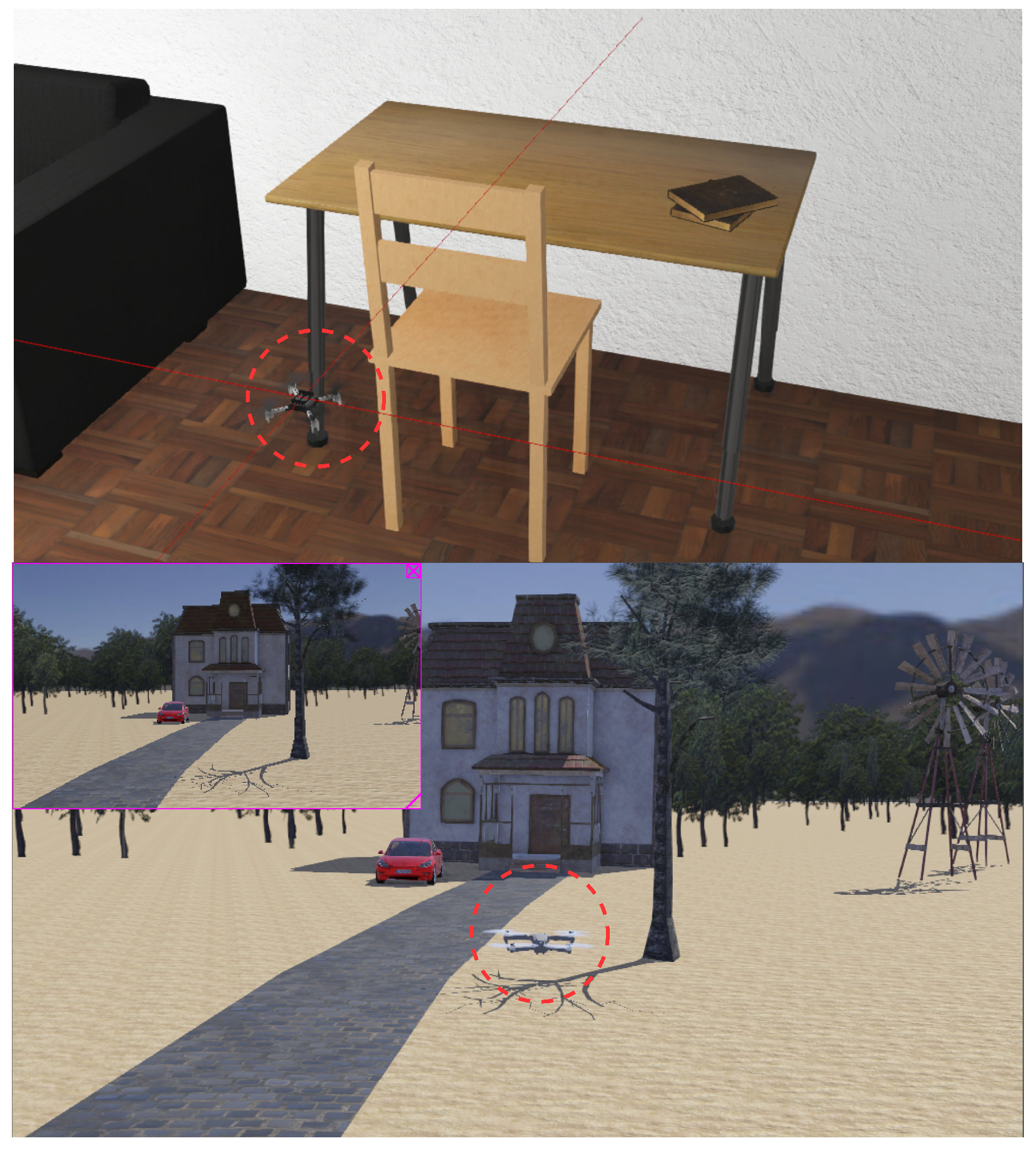

Figure 8 shows the Crazyflie and the DJI Mavic performing in the Webots simulation platform.

The UAV model in the popular CoppeliaSim platform closely mimics the DJI Tello design. Since CoppeliaSim allows modification of material properties such as material mass and sensor parameters, it can be modified to simulate the DJI Tello.

Figure 9 shows a general quadcopter whose in-simulation model characteristics, such as mass, thrust, and sensor suite, were modified to be similar to the Tello.

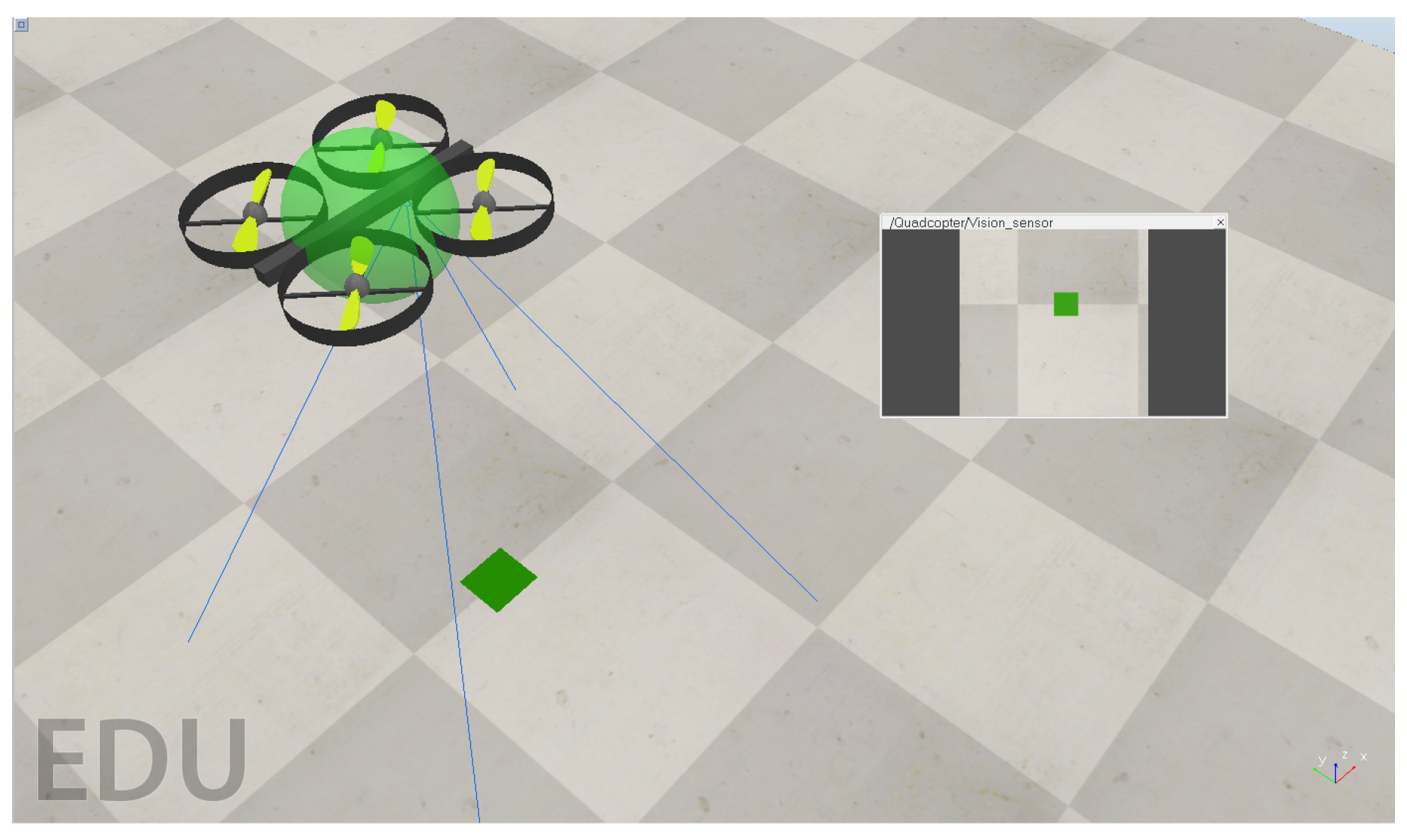

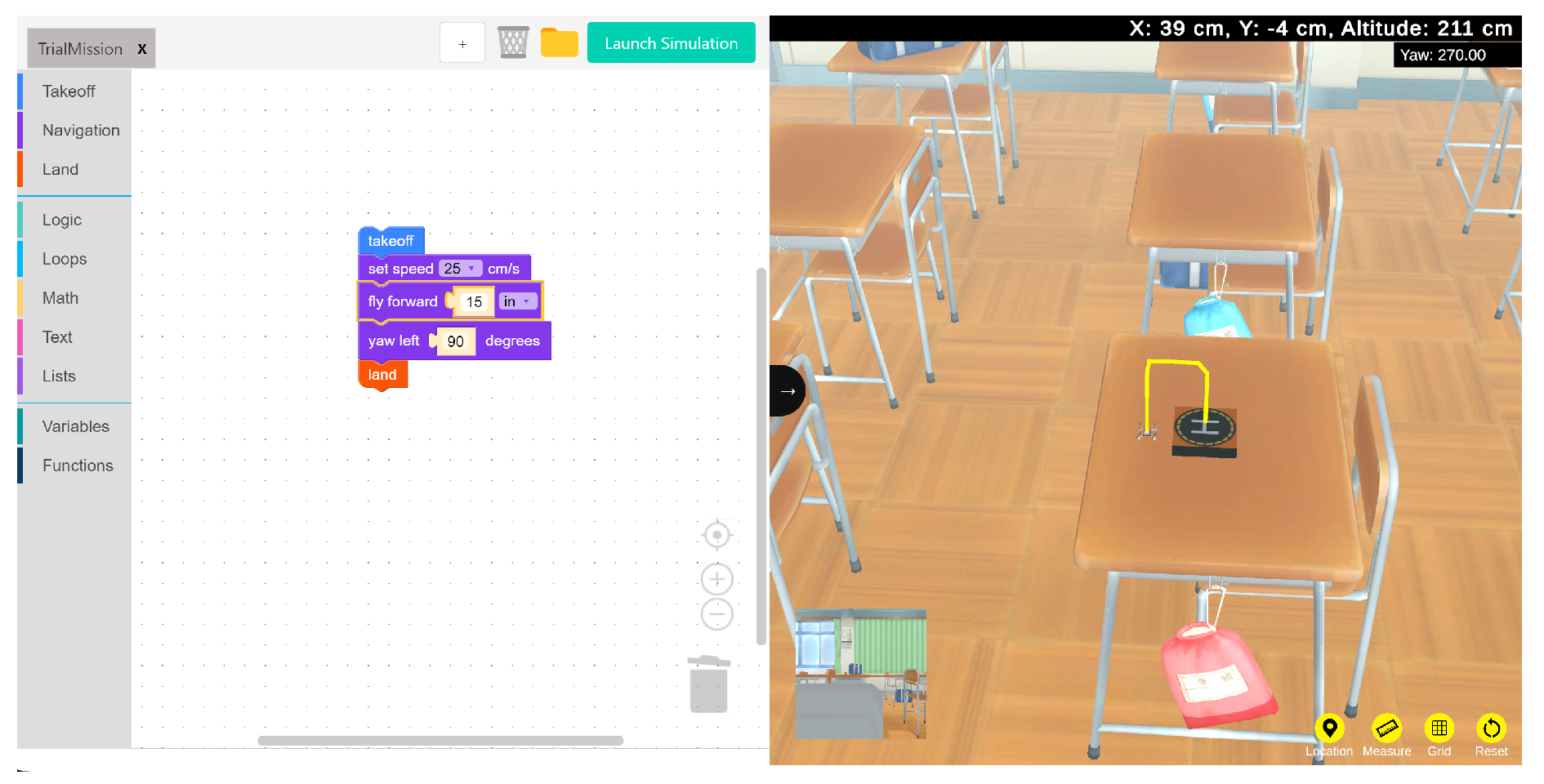

Drone Blocks also offers a convenient simulation platform along with their block code support. Students and educators can now control the Crazyflie directly and code for it in the platform. The side-by-side simulator also offers a risk-free way to observe code directly in action on a simulator before being deployed on the actual drone.

Figure 10 shows a screen capture of the Drone Blocks platform and the simulator.

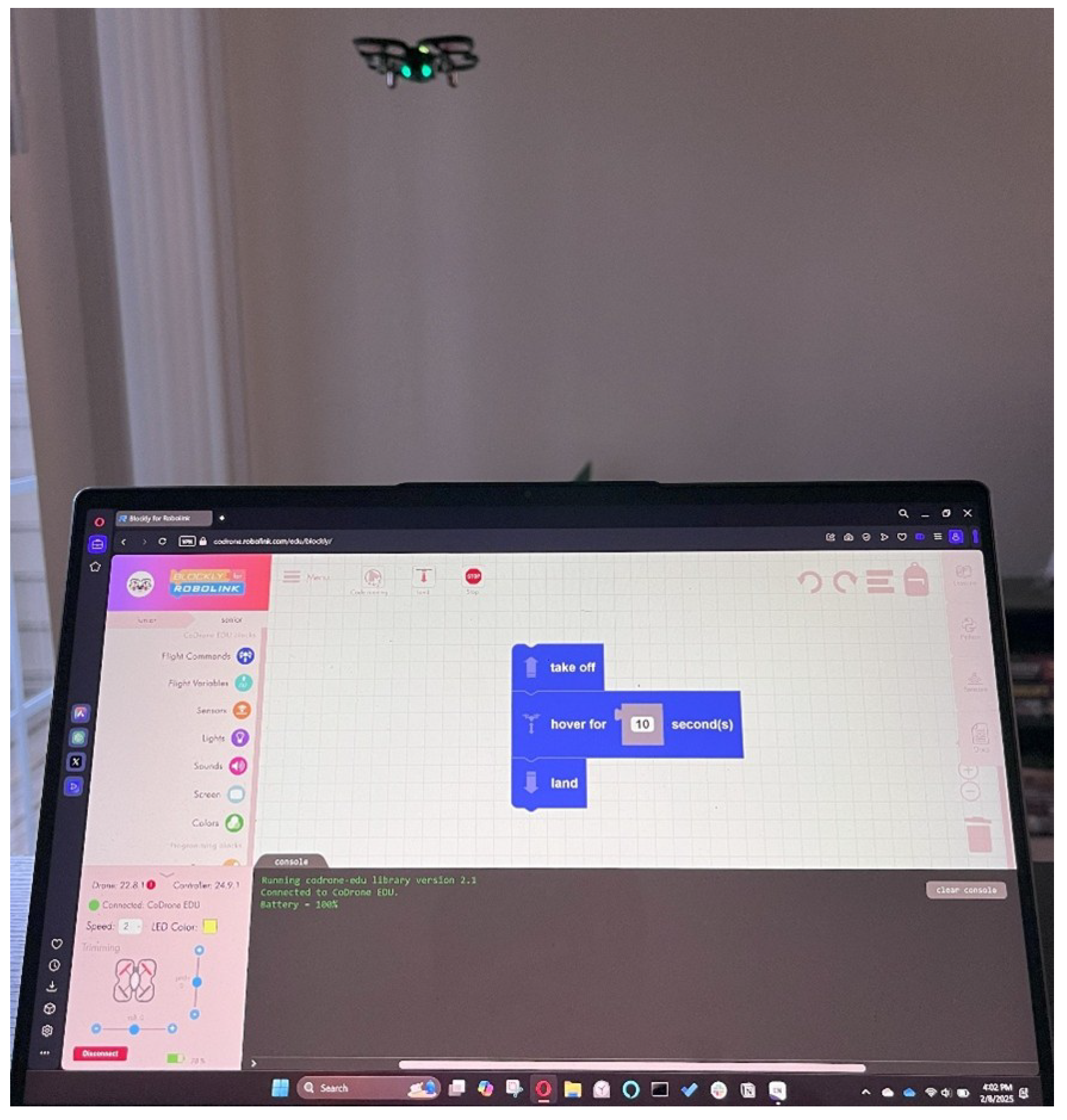

Figure 11 shows the Robolink CoDrone connected to a PC running Blockly and executing a mission.

Regarding ROS support, the CoDrone platform is not officially compatible with ROS. Tello EDU can be easily integrated into the ROS ecosystem. Popular packages and strong community support are available for both ROS1 and ROS2. Some packages have even succeeded in extending the capabilities of the drone, such as allowing Visual SLAM capabilities for mapping indoor environments. Crazyflie is one of the most popular platforms for ROS development in research and education. The official package “crazyswarm” has several features, such as drivers for communication with the Crazyflie, simulation tools for testing algorithms in a virtual environment, demo applications showcasing various functionalities, and support for swarm behavior, allowing you to control multiple Crazyflies simultaneously.

2.5. Use Cases and Suggested Integrations in Research.

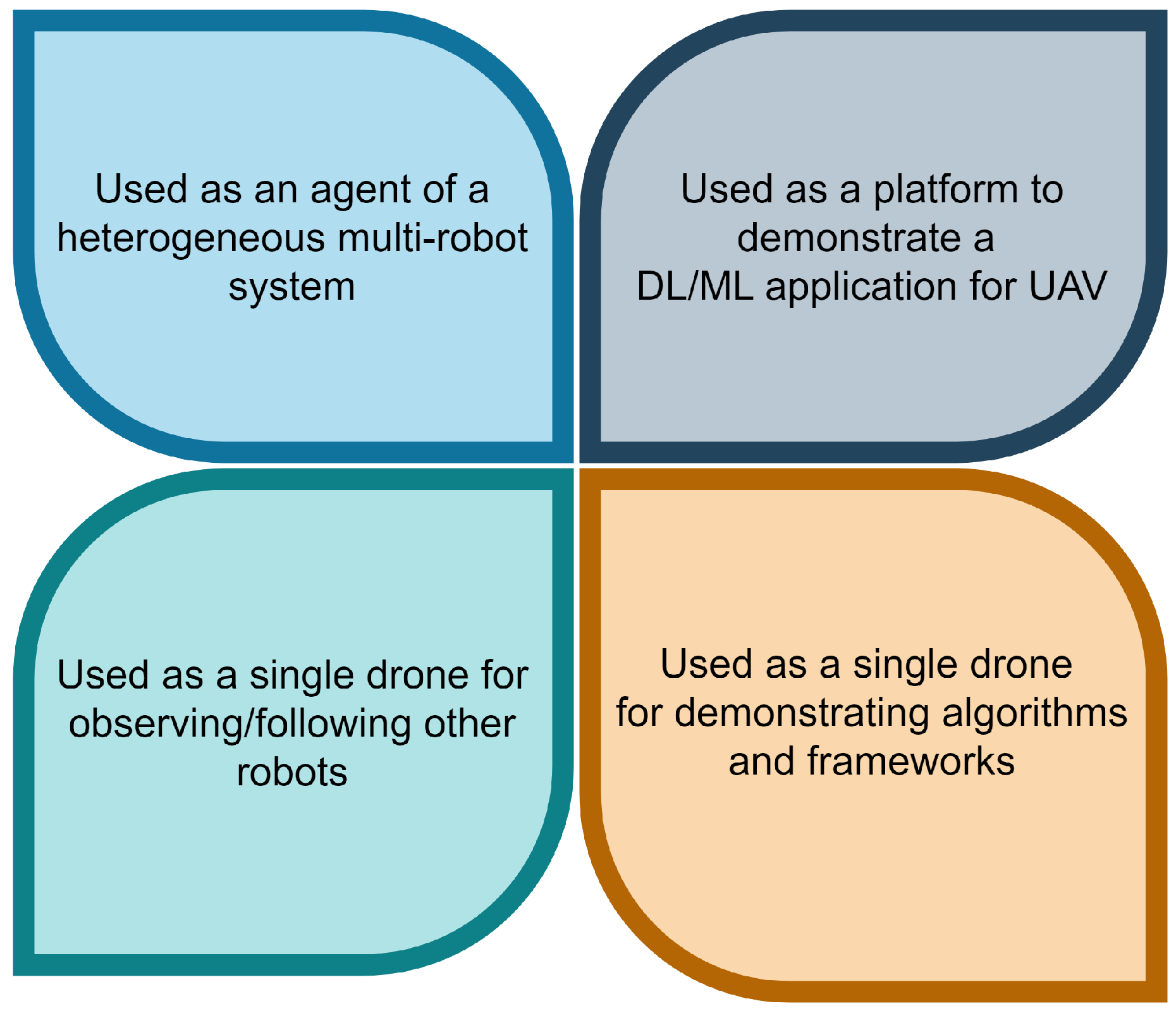

The potential of these low-cost drone platforms has reached beyond the classroom into the domain of research applications. A brief literature review conducted during this study highlighted their use in four significant use case scenarios.

Figure 12 shows the four possible use case scenarios of educational drone platforms in research applications.

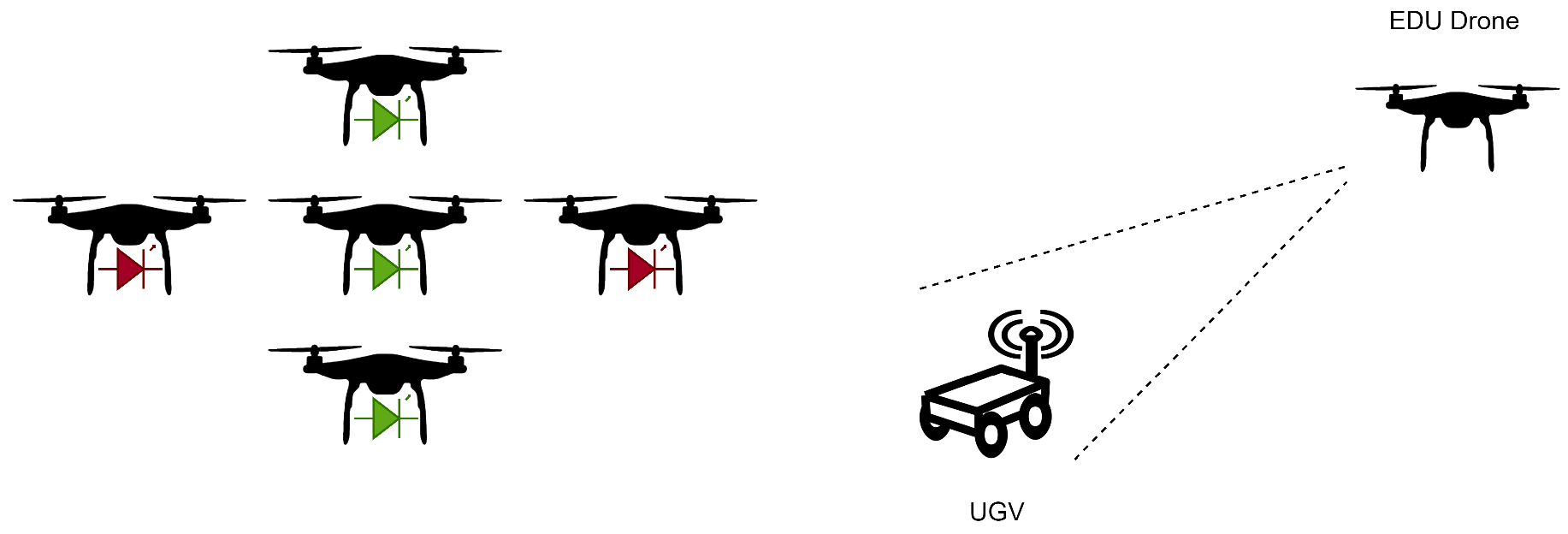

Figure 13 shows two common uses of educational drone platforms in current research.

Table 6 and

Table 7 list current literature that uses the Crazyflie and the DJI Tello platforms and outline the use case scenarios for each. Additional applications can be demonstrated using these platforms. Some future suggested use cases include using them as Blockchain-backed data collection and storage platforms [16], using LLM as a control structure for autonomous flight [17], and as agents of large-scale hierarchical swarms [18].

Due to its focus being more on classroom education and less on research applications, very little research exists that uses the Robolink EDU platform. However, the newer revised version of the platform shows promising capabilities that have potential in application use cases similar to the other two platforms.

2.6. Key Takeaways

Schools and universities are increasingly incorporating drones into STEM curricula to make learning interactive and relevant to 21st-century careers, particularly in robotics, automation, and data analytics. Moreover, drones are an accessible platform for introducing emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning through applications like autonomous navigation and object recognition. The potential of UAVs in education is vast, offering a dynamic approach to skill-building and knowledge acquisition that prepares students for the evolving demands of modern industries. Conceptual knowledge of aerodynamics, GNSS, inertial navigation, and electronics is communicated effectively through experiments and demonstrations on UAV platforms. Additionally, creative applications such as aerial photography and videography encourage students to think critically about storytelling and visual design.

An additional topic to be explored is the proliferation of complete DIY packages that involve using open-source files to make/print 3D aircraft models and individually source the electronic components to create modular drones from scratch. However, this approach is more hands-on and involves considerably more effort.

Readily available, low-cost educational platforms, like those discussed in this study, form a crucial bridge between higher-end commercial drones and DIY package drones. They offer a practical outlet for students to explore the domain before they venture further into it as research or a creative pursuit.

References

- Xiaoning, Z. Analysis of military application of UAV swarm technology. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), 2020, 27-28 Nov. 2020; pp. 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Lan, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhang, Y. WSN-Assisted UAV Trajectory Adjustment for Pesticide Drift Control. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsouros, D.C.; Bibi, S.; Sarigiannidis, P.G. A Review on UAV-Based Applications for Precision Agriculture. Information 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvane, Q.; Fleureau, J.; Tariolle, F.-L.; Guillotel, P. Automated cinematography with unmanned aerial vehicles. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.04353 2017. [CrossRef]

- Tzoumas, G.; Pitonakova, L.; Salinas, L.; Scales, C.; Richardson, T.; Hauert, S. Wildfire detection in large-scale environments using force-based control for swarms of UAVs. Swarm Intelligence 2022, 17, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczyk, E. UGV and UAV collaboration in an autonomous infrastructure scenario. 2020.

- Batistatos, M.C.; Mazilu, A.I.; Kourtis, M.-A.; Xilouris, G.K.; Santorinaios, D.; Oikonomakis, A.; Oikonomakis, G.; Leonis, P.E.; Sygrimis, P.A.; Ntouros, K.G.; et al. UAV Swarm Management Platform for Autonomous Area and Infrastructure Inspection. In Proceedings of the 2024 Panhellenic Conference on Electronics & Telecommunications (PACET), 2024; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Bolick, M.M.; Mikhailova, E.A.; Post, C.J. Teaching innovation in STEM education using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Education Sciences 2022, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usselman, M.; Ryan, M.; Rosen, J.H.; Koval, J.; Grossman, S.; Newsome, N.A.; Moreno, M.N. Robotics in the core science classroom: Benefits and challenges for curriculum development and implementation (rtp, strand 4). In Proceedings of the 2015 ASEE annual conference &, exposition; 2015; pp. 26–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Phadke, A.; Medrano, F.A.; Sekharan, C.N.; Chu, T. Designing UAV Swarm Experiments: A Simulator Selection and Experiment Design Process. Sensors 2023, 23, 7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phadke, A.; Medrano, A. Drone2Drone: A search and rescue framework for finding lost UAV swarm agents; Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi: Symposium for Student Innovation, Research, and Creative Activities 2023, 2023 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Phadke, A.; Medrano, F.A.; Chu, T.; Sekharan, C.N.; Starek, M.J. Drone2Drone (D2D): A Search and Rescue Framework Module for Finding Lost UAV Swarm Agents. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, 2023, & Applied Computing (CSCE); pp. 903–908. [CrossRef]

- Takayama, Y.; Ratsamee, P.; Mashita, T. Reduced Simulation: Real-to-Sim Approach toward Collision Detection in Narrowly Confined Environments. Robotics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Nagahara, M. Platooning control of drones with real-time deep learning object detection. Advanced Robotics 2022, 37, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, A.; Medrano, F.A. Towards Resilient UAV Swarms—A Breakdown of Resiliency Requirements in UAV Swarms. Drones 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, A.; Sekharan, C.N.; Vasudeva, K.K.; Kar, D. Unifying Sky and Chain: A Perspective on Blockchain’s Role in UAV Swarms. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain, 7-8 Sept. 2024, 2024, and Internet of Things (AIBThings); pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Phadke, A.; Hadimlioglu, A.; Chu, T.; Sekharan, C.N. Integrating Large Language Models for UAV Control in Simulated Environments: A Modular Interaction Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.17602 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Wang, Y.; Ayanian, N. Hierarchical Trajectory (Re) Planning for a Large Scale Swarm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.16743 2025. [CrossRef]

- Karagüzel, T.A.; Turgut, A.E.; Eiben, A.E.; Ferrante, E. Collective gradient perception with a flying robot swarm. Swarm Intelligence 2022, 17, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisa, A.S.; Satpute, S.G.; Lindqvist, B.; Nikolakopoulos, G. An Edge-Based Architecture for Offloading Model Predictive Control for UAVs. Robotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Nex, F.; Vosselman, G.; Kerle, N. End-to-End Nano-Drone Obstacle Avoidance for Indoor Exploration. Drones 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Ding, R.; Wu, W. HHPSO: A Heuristic Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Path Planner for Quadcopters. Drones 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Robins, A.; Lillywhite-Roake, C.; Pearce, A.; Mehta, H.; James, S.; Wong, T.H.; Pournaras, E. M-SET: Multi-Drone Swarm Intelligence Experimentation with Collision Avoidance Realism. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.; Lima, G.V.; Morais, A.S.; Oliveira-Lopes, L.C.; Ramos, D.C.; Tofoli, F.L. Modified Artificial Potential Field for the Path Planning of Aircraft Swarms in Three-Dimensional Environments. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanHorn, K.; Wolek, A. Machine-Learning-Based Wind Detection and Avoidance Using a Crazyflie Micro Drone. In Proceedings of the 2024 Regional Student Conferences; 2024; p. 85491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virbora, N.; Sokoeun, U.; Saran, M.; Sovicheyratana, S.; Channareth, S.; Saravuth, S. Implementation of Matrix Drone Show Using Automatic Path Generator with DJI Tello Drones. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET); 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Deng, F.; Lam, T.L. Asymmetric Self-Play-EnabledIntelligent Heterogeneous Multirobot Catching System Using Deep Multiagent Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.; Raychowdhury, A. Autonomous Navigation via Deep Reinforcement Learning for Resource Constraint Edge Nodes using Transfer Learning. IEEE Access 2020, vol. 8, 26549–26560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakura, N.; Kiyokawa, T.; Kumamoto, H.; Takamatsu, J.; Ogasawara, T. Collection of Marine Debris by Jointly Using UAV-UUV With GUI for Simple Operation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 67432–67443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.A.; Shekaramiz, M.; Masoum, M.A.S. Computer Vision-Based Path Planning with Indoor Low-Cost Autonomous Drones: An Educational Surrogate Project for Autonomous Wind Farm Navigation. Drones 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusefi, A.; Durdu, A.; Aslan, M.F.; Sungur, C. LSTM and Filter Based Comparison Analysis for Indoor Global Localization in UAVs. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 10054–10069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubran, I.; Fares, F.; Alfassi, Y.; Feldman, F.A.a.D. Newton-PnP: Real-time Visual Navigation for Autonomous Toy-Drones. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Kyoto, Japan, 23-27 October 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A Robolink CoDrone EDU flying in an outdoor test scenario.

Figure 1.

A Robolink CoDrone EDU flying in an outdoor test scenario.

Figure 2.

An example of the DJI Tello live view use where a “rescue” DJI agent is searching for a target DJI agent [12].

Figure 2.

An example of the DJI Tello live view use where a “rescue” DJI agent is searching for a target DJI agent [12].

Figure 3.

Ryze Tello MATLAB package to control DII Tello EDU.

Figure 3.

Ryze Tello MATLAB package to control DII Tello EDU.

Figure 4.

UAV (green dot) in the presence of obstacles and three light-based positioning beacons.

Figure 4.

UAV (green dot) in the presence of obstacles and three light-based positioning beacons.

Figure 5.

A depiction of lighthouse base stations emitting IR to assist crazyflie positioning (Figure recreated from original crazyflie-lighthouse documentation).

Figure 5.

A depiction of lighthouse base stations emitting IR to assist crazyflie positioning (Figure recreated from original crazyflie-lighthouse documentation).

Figure 6.

Workflow of the DJI Tello getting localization information by using external marker detection.

Figure 6.

Workflow of the DJI Tello getting localization information by using external marker detection.

Figure 7.

An old version of Robolink EDU (left) and its swarm formation vs. DJI Tello edu (right) and its swarm formation.

Figure 7.

An old version of Robolink EDU (left) and its swarm formation vs. DJI Tello edu (right) and its swarm formation.

Figure 8.

A crazyflie (top) and a DJI Mavic drone (bottom) in the Webots simulation platform.

Figure 8.

A crazyflie (top) and a DJI Mavic drone (bottom) in the Webots simulation platform.

Figure 9.

A general quadcopter in the CoppeliaSim edu simulator modified to have DJI Tello-like characteristics

Figure 9.

A general quadcopter in the CoppeliaSim edu simulator modified to have DJI Tello-like characteristics

Figure 10.

A simple mission and side-by-side integrated simulator offered by Drone Blocks for the crazyflie platform.

Figure 10.

A simple mission and side-by-side integrated simulator offered by Drone Blocks for the crazyflie platform.

Figure 11.

Robolink CoDrone connected to Blockly running a simple mission.

Figure 11.

Robolink CoDrone connected to Blockly running a simple mission.

Figure 12.

Four use case scenarios for drone platforms in research.

Figure 12.

Four use case scenarios for drone platforms in research.

Figure 13.

Two common uses of low-cost drone platforms. Using them in multi-swarm fashion for drone shows (left) and using them as observe drones in a heterogeneous multi-robot system (right)

Figure 13.

Two common uses of low-cost drone platforms. Using them in multi-swarm fashion for drone shows (left) and using them as observe drones in a heterogeneous multi-robot system (right)

Table 1.

General platform information.

Table 1.

General platform information.

| |

DJI Tello EDU |

Robolink CoDrone EDU |

Bitcraze Crazyflie |

| The average cost of a unit in USD (as of December 2024) |

$200 |

$215 |

$240 |

| Community support |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Parent company offers other UAV products? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Parent company offers robot vehicle kits? |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Table 2.

Comparison of the hardware characteristics of the three drone platforms.

Table 2.

Comparison of the hardware characteristics of the three drone platforms.

| |

DJI Tello EDU |

Robolink CoDrone EDU |

Crazyflie |

| Modular build |

No (Motors and propellers can be replaced) |

Yes |

Yes |

| Front facing camera |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Live flight view |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Downward facing camera |

Yes (Used by Visual Positioning System) |

No |

No |

| Brushless motors |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Multiple/quick battery charge kit |

Yes |

Yes |

Not standard |

| GNSS capability |

No |

No |

No |

| Additional special sensors |

Visual Positioning system through bottom sensor |

Bottom range, Optical flow, and color sensor |

Additional sensors are available |

| External controller (in package) |

No |

Yes |

No |

Table 3.

DJI Tello camera specifications.

Table 3.

DJI Tello camera specifications.

| Photo |

5MP (2592x1936) |

| FOV (Field of View) |

82.6° |

| Video |

HD720P30 |

| Format |

JPG(Photo); MP4(Video) |

| EIS |

Yes |

Table 4.

Comparison of the capability and physical characteristics of the three drone platforms.

Table 4.

Comparison of the capability and physical characteristics of the three drone platforms.

| |

DJI Tello EDU |

Robolink CoDrone EDU |

Crazyflie |

| Multi-agent (Swarm) support |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Flight range (Vertical) |

30 m |

50 m |

30 m (tested) |

| Flight range (Lateral) |

100 m |

50 m |

30 m (tested) |

| Battery capacity |

1.1 Ah/3.8 V |

3.7v 530mAh 20C |

170 mAh, 250 mAh, 350 mAh options |

| Weight |

87 grams |

54.8 grams |

37 grams |

| Battery charge time |

90 minutes |

60 minutes |

60 minutes |

| Continuous flight time (indoor scenario) |

13 minutes |

7 minutes |

10 minutes |

| Drone dimensions |

98 mm by 92.5 mm |

138.8 mm by 138.5 mm |

80.7 mm by 110 mm (cross length) |

| Maximum flight speed |

8 m/s |

2.5 m/s |

1.1 m/s |

| Physical marker support |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Table 5.

Comparison of the usage and support characteristics of the three drone platforms.

Table 5.

Comparison of the usage and support characteristics of the three drone platforms.

| |

DJI Tello EDU |

Robolink CoDrone |

Crazyflie |

| Direct tool interface |

Yes, mobile application |

No |

Yes, mobile applications and PC clients |

| Simulator support |

No* |

No |

Yes |

| Python support |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Indirect scripting/blockly support |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| ROS support |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Table 6.

An outline of current research that uses the Crazyflie platform.

Table 6.

An outline of current research that uses the Crazyflie platform.

| Reference number |

Purpose of use |

| [19] |

Demonstrates collective gradient following using a swarm of Crazyflie UAVs. |

| [20] |

Demonstration of offloading high-level control tasks of UAV to the edge for Model Predictive Control |

| [21] |

Demonstration of obstacle avoidance in an indoor scenario. |

| [22] |

Demonstrate a hybrid PSO for path planning using the Crazyflie. |

| [23] |

Used as a platform in a testbed designed to evaluate distributed sensing with swarm intelligence |

| [24] |

Demonstration of the capture of an agent using multi-drone formation |

| [25] |

Demonstration of ML-supported drone platform’s ability to detect wind and adjust trajectory. |

Table 7.

An outline of current research that uses the DJI Tello EDU platform.

Table 7.

An outline of current research that uses the DJI Tello EDU platform.

| Reference number |

Purpose of use |

| [26] |

100 DJI Tello agents were used to demonstrate the creation of a matrix-based drone show. |

| [27] |

Used as a part of a heterogeneous multi-robot system |

| [28] |

Used to demonstrate autonomous navigation using deep reinforcement learning |

| [29] |

Used a marine debris spotter in tandem with a UUV (Unmanned Underwater Vehicle) to collect debris |

| [30] |

Used to study computer vision-based path planning in a wind turbine farm scenario |

| [31] |

Used to demonstrate multi-modal deep neural network-based monocular visual-inertial localization framework. |

| [32] |

Turns the Tello into a self-reliant autonomous navigation drone using visual navigation cues |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).