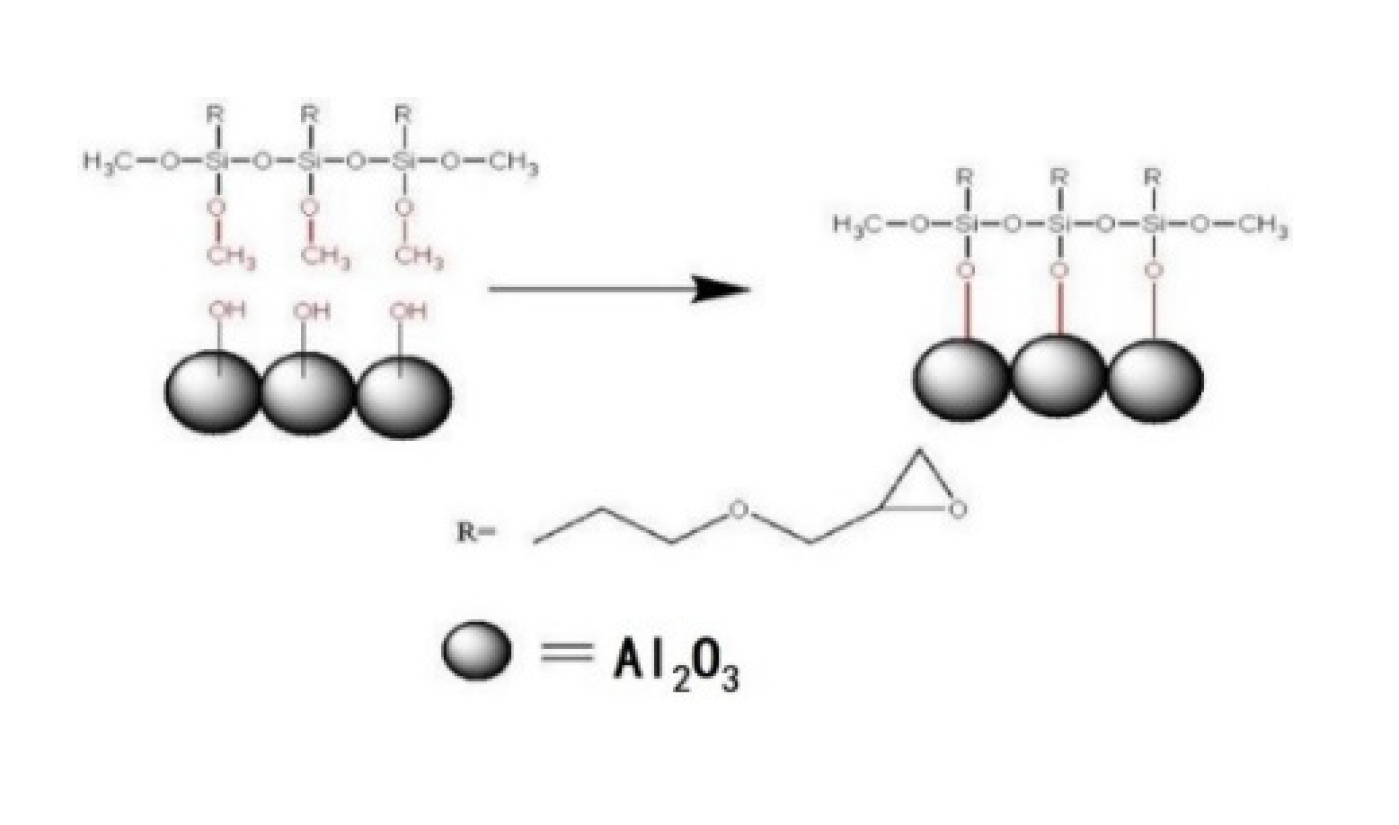

3.1. Morphology Structure of the Al2O3

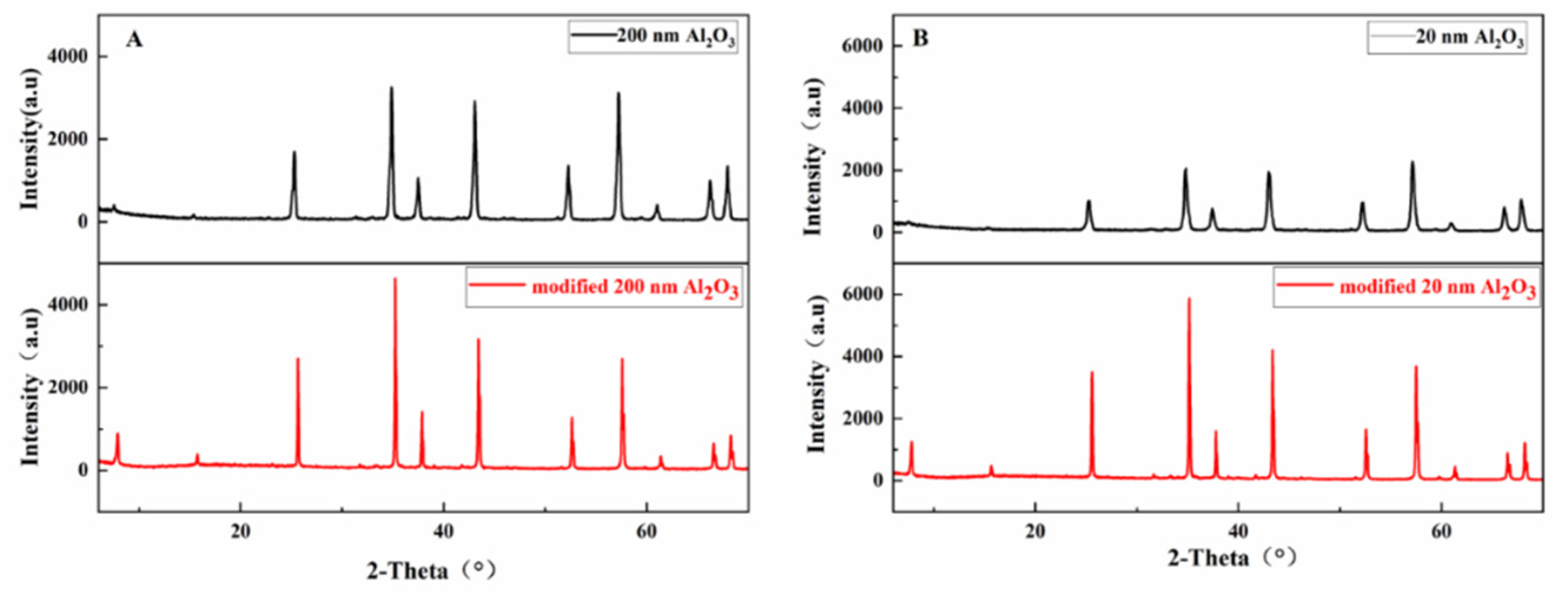

Figure 3 shows the XRD pattern of nano-Al

2O

3 before and after modification. It can be seen from the

Figure 3A that the modified 200 nm Al

2O

3 sample shows characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ angles of 25.65°, 35.21°, 43.45°, 52.62° and 57.59°. Compared with the X-ray diffraction pattern of the unmodified 200 nm Al

2O

3, the position of the characteristic peaks is consistent, indicating that the surface modification treatment does not cause the change of crystal structure. It is worth noting that the intensity of all characteristic peaks of the modified Al

2O

3 is increased, which indicates that the introduction of KH560 leads to the enhancement of the crystallization degree of Al

2O

3 and the increase of coordination number. Therefore, the crystallinity of modified Al

2O

3 increases, accompanied by the increase in the coordination degree, which is directly reflected in the enhancement of the characteristic peak strength in the XRD pattern. The modified 20 nm Al

2O

3 as shown in

Figure 3B is similar to the modified 200 nm Al

2O

3, the characteristic peak is basically unchanged but the height of the peak is increased.

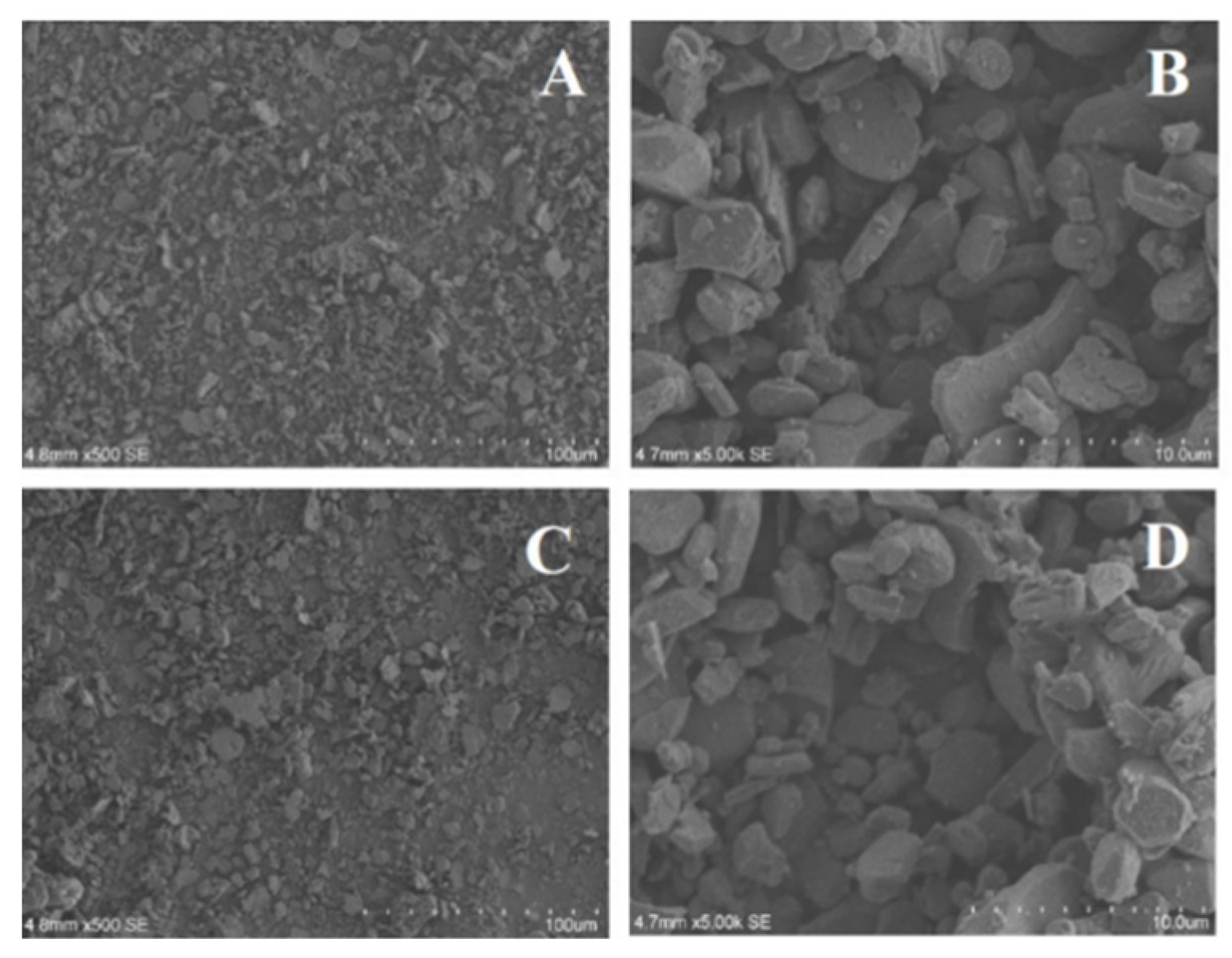

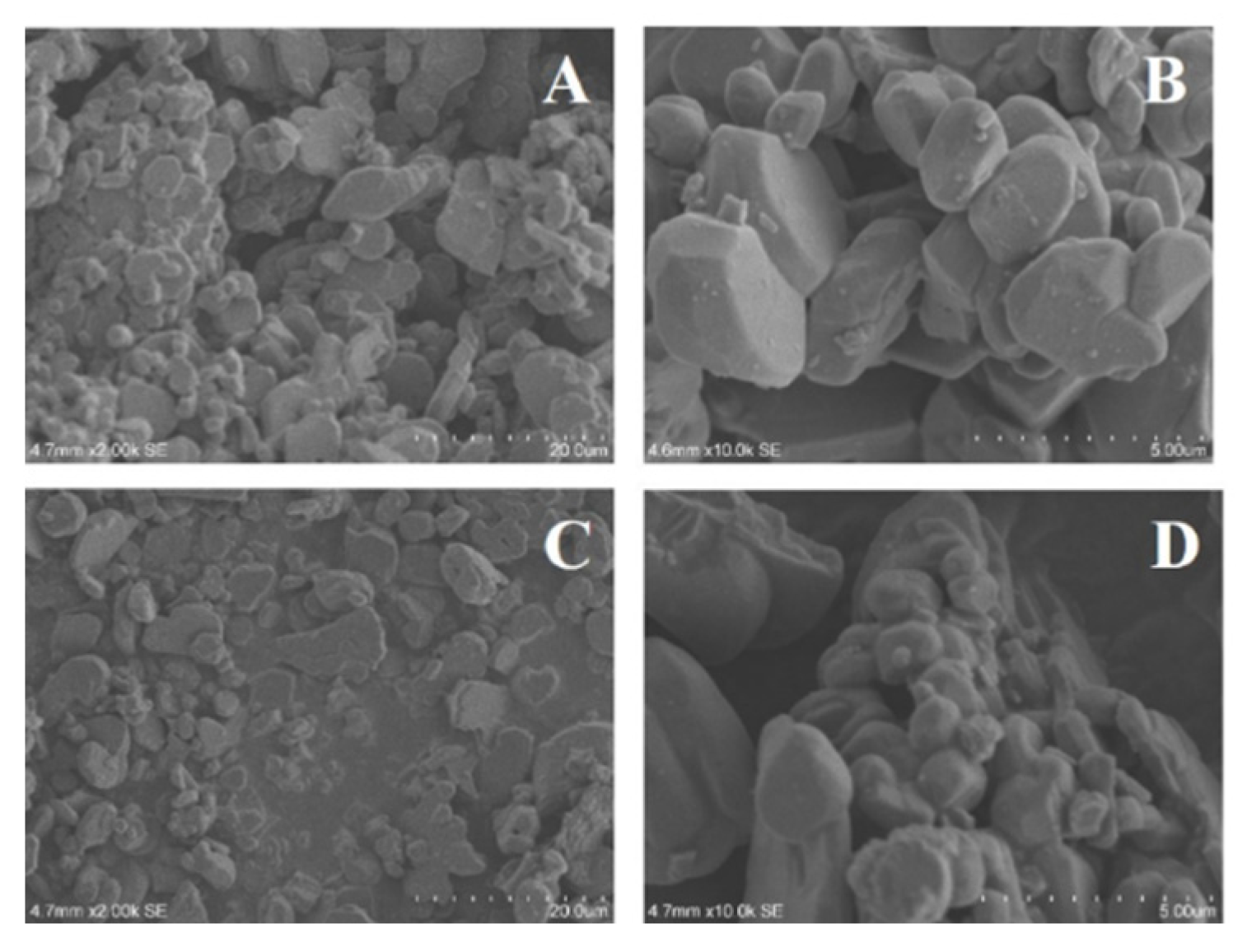

In order to study the appearance of Al

2O

3 with different particle sizes and morphologies, SEM with different magnification rates was used to observe its apparent morphology, and the results were shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 (A, C: low-resolution, B, D: high-resolution). As can be seen from

Figure 4, the unmodified Al

2O

3 at 200 nm and 20 nm have a good morphology, which surface are smooth, and the size are basically consistent with the said standard. It can be seen from

Figure 4A that at low-resolution, 200 nm Al

2O

3 exhibits different particle sizes, uneven structures and different morphologies, while at high-resolution (

Figure 4B), it is found that the surface of Al

2O

3 is smooth with less impurities. In

Figure 5A and B, it can be seen that the morphology of 20 nm Al

2O

3 is similar to that of 200 nm Al

2O

3, with fewer impurities. The surface morphologies of the unmodified Al

2O

3 are shown in

Figure 5. It can be seen from

Figure 5A and C that the modified Al

2O

3 still have the intact morphology, indicating that the modification method does not destroy the original crystal structure of the nanoparticles, which is consistent with the XRD results above. It can be observed from

Figure 5B and D that the surface of the modified Al

2O

3 is rougher than that of the unmodified Al

2O

3, and more obvious bulges can be seen, indicating that the surface modification of Al

2O

3 by KH-560 has been realized. In addition, it can also be seen that compared with 200 nm Al

2O

3, the surface of 20 nm Al

2O

3 have a more obvious bulge and a looser arrangement, which indicates that the smaller particle size of Al

2O

3 is more dispersed during the modification process and is easier to be modified by surfactants.

3.2. Dielectric Properties of the Materials

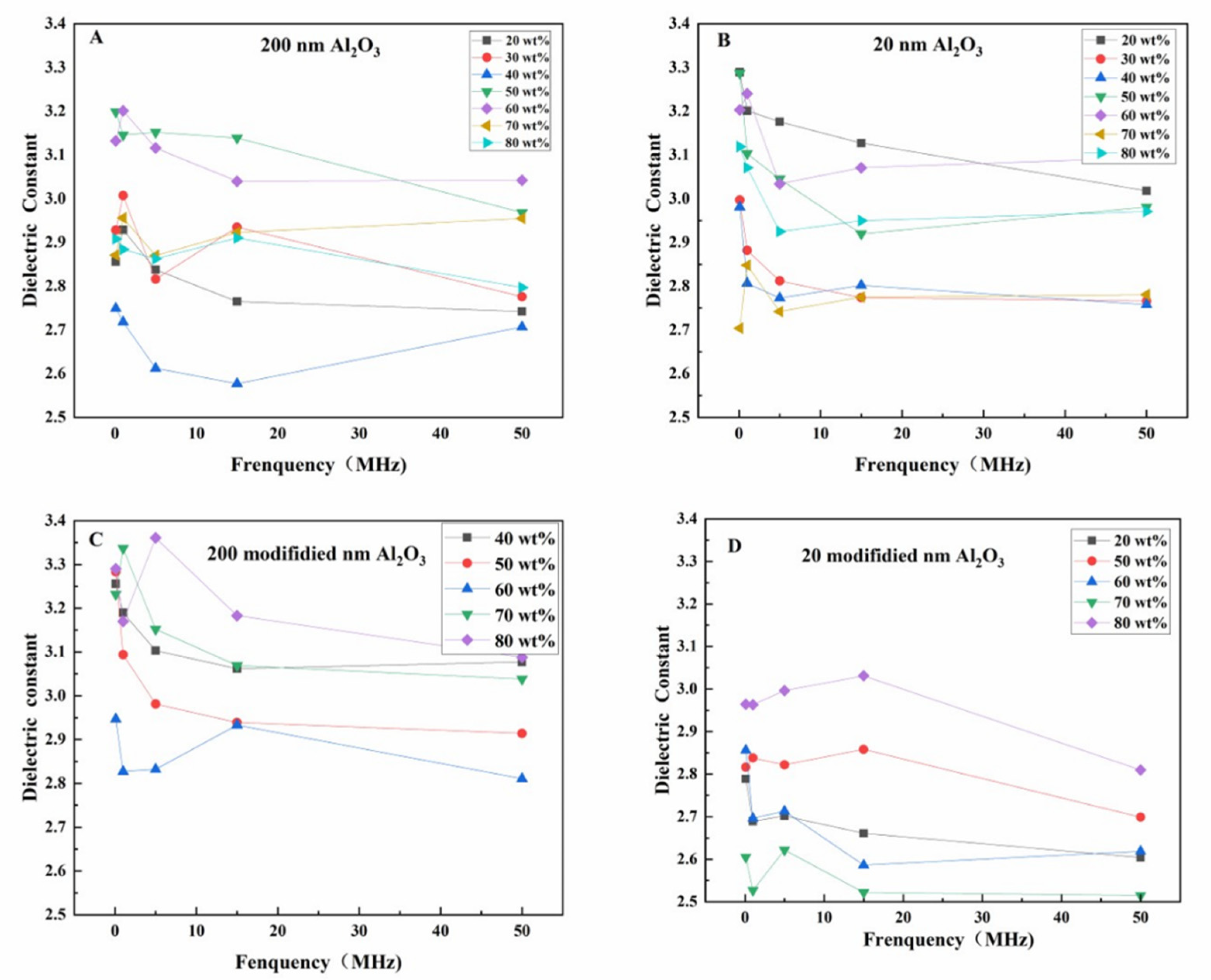

As can be seen from

Figure 6, the dielectric constant of Al

2O

3/EP composite material changes with the increase of Al

2O

3 content, but the change amplitude is not uniform, which is mainly related to the interaction between the low dielectric constant of Al

2O

3 (8-10) and the dielectric constant of EP matrix (3.2-3.6). The addition of Al

2O

3 effectively reduces the dielectric constant of the composite material, especially at high frequency (50 MHz), the Al

2O

3/EP composite still maintains a low dielectric constant, indicating that Al

2O

3 inhibits the polarization transition, making it suitable for the application of high frequency insulating electronic materials. However, the dielectric constant of the high-filled composites fluctuates greatly at low frequencies, which may be caused by the increase of the content of the filler leading to the increase of the electrical conductivity, and the intensification of the interface polarization and particle agglomeration phenomenon.

Meanwhile, as shown in

Figure 6A, when the Al

2O

3/EP composite of 200 nm is filled with 40 wt% Al

2O

3, the dielectric constant from low frequency to high frequency is always maintained at about 2.6, indicating that the material is difficult to have polarization transformation in the wide frequency range, and has good high frequency and low frequency insulation properties. While in

Figure 6B, the 20 nm Al

2O

3/EP composite material has the lowest dielectric constant of 2.7 when the filling amount of Al

2O

3 is 20 wt% at the low frequency of 0.1MHz, which is 15.6% lower than the dielectric constant of traditional EP, showing excellent insulation performance and suitable for the application of low-frequency insulating electronic materials. This shows that the particle size has a significant effect on the dielectric constant of the composite material: Al

2O

3 particles with smaller particle size (such as 20 nm) can be more evenly dispersed in the EP matrix due to their larger specific surface area, reducing interface defects and polarization effects, and thus exhibiting lower dielectric constant at low frequencies. Although the larger particle size (such as 200 nm) Al

2O

3 particles may lead to an increase in the interface region at a high filling amount, they can still maintain a stable low dielectric constant in the wide frequency range due to their low dielectric constant characteristics.

Figure 6C and D respectively show the results of the change of the modified Al

2O

3 content with two different particle sizes on the dielectric constant of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composite with frequency. As can be seen from the figure, with the increase of the added amount of modified Al

2O

3, the dielectric constant value of the composite material presents a different trend of change. Although the change amplitude is different, the dielectric constant of all modified Al

2O

3/EP composites is lower than that of pure EP matrix, indicating that the addition of modified Al

2O

3 effectively improves the insulation property of the composite material. It can meet the high requirements of insulation properties of electronic materials. Before and after Al

2O

3 modification, the effect on the dielectric constant of the composite material is significant: due to the poor interface bonding between the unmodified Al

2O

3 and the EP matrix, interface defects and interface polarization are easy to occur, resulting in high dielectric constant. The interface compatibility between the modified Al

2O

3 and the EP matrix is significantly improved by surface treatment (such as silane coupling agent modification), and the interface polarization and defects are reduced, thus reducing the dielectric constant of the composite material. In addition, the dispersion of the modified Al

2O

3 particles is better, which reduces the particle agglomeration phenomenon, further improves the uniformity and stability of the composite material, and makes it show a lower dielectric constant in the wide frequency range.

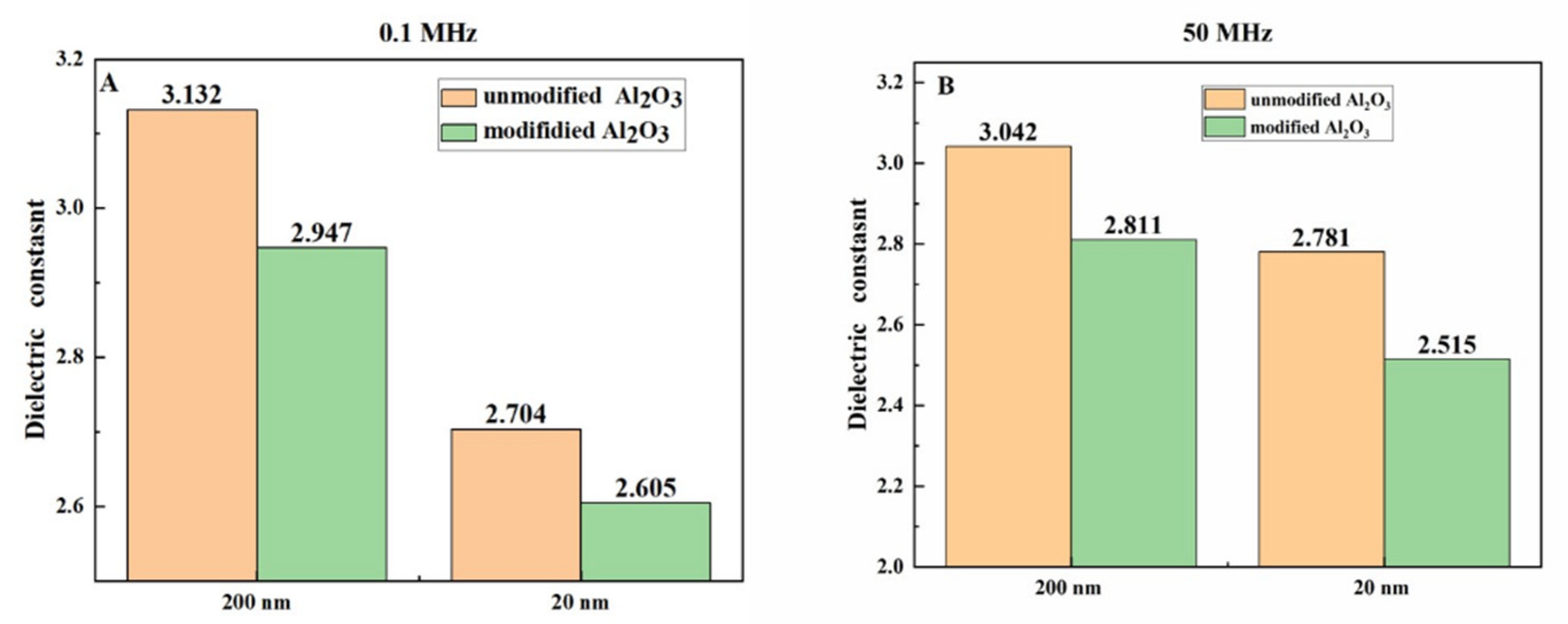

In addition, by comparing the dielectric constants of Al

2O

3/EP and modified Al

2O

3/EP composites at two representative frequency points of 0.1MHz and 50MHz (as shown in

Figure 7), it was found that the dielectric constants of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composites were lower than those of the unmodified Al

2O

3/EP composites at both low and high frequencies. Especially at the high frequency of 50 MHz, when the content of Al

2O

3 at 20 nm is 50 wt%, the dielectric constant of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composite is 2.515, which is 9.56% lower than that of the unmodified Al

2O

3/EP composite (2.781). The results show that the modified Al

2O

3/EP composites have better insulation properties. The influence of Al

2O

3 before and after modification on the dielectric constant of the composite is mainly reflected in the interface bonding and dispersion: the unmodified Al

2O

3 is easy to produce interface defects and interface polarization due to poor interface bonding with EP matrix, resulting in high dielectric constant. The interface compatibility between the modified Al

2O

3 and the EP matrix was significantly improved by silane coupling agent modification, and the interface polarization and defects were reduced, thus reducing the dielectric constant. In addition, particle size also has a significant impact on dielectric properties: Al

2O

3 particles with smaller particle size (such as 20 nm) can be more evenly dispersed in the EP matrix due to their larger specific surface area, further reducing interface polarization and defects, and thus exhibiting lower dielectric constant at both low and high frequencies. Although the larger particle size of Al

2O

3 particles may lead to the increase of the interface region at high filling amount, due to the optimization of modification treatment, it can still maintain a low dielectric constant in the wide frequency range.

3.3. Thermal Conductivities of the Materials

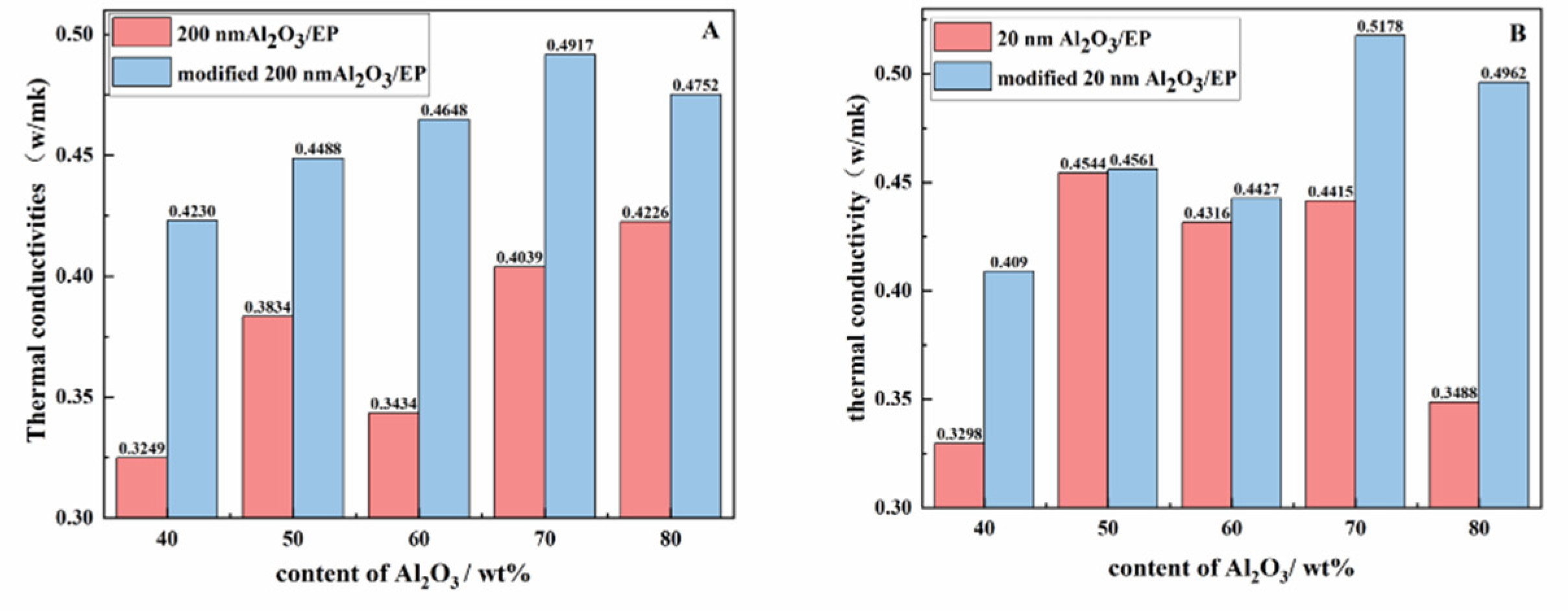

In order to further compare the differences in thermal conductivity between Al

2O

3/EP and modified Al

2O

3/EP composites, this study compared the thermal conductivity of materials with different particle sizes and different Al

2O

3 content (as shown in

Figure 8). The results show that the thermal conductivity of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composites is higher than that of the unmodified Al

2O

3/EP composites, which is mainly due to the better dispersion of the modified Al

2O

3 in the EP matrix, the reduction of particle agglomeration phenomenon, and the formation of a more effective thermal conductivity channel. Specifically, when 60 wt% modified 200 nm Al

2O

3 was added, the thermal conductivity of the composite was 0.4427 W/mK, which was 29% higher than that of the unmodified material (0.3434 W/mK). When adding 80 wt% modified 20 nm Al

2O

3, the thermal conductivity reached 0.4962 W/mK, which was 43% higher than that of the unmodified material (0.3488 W/mK). The influence of Al

2O

3 before and after modification on the thermal conductivity of the composite is mainly reflected in the interface bonding and dispersion: the unmodified Al

2O

3 is easy to form agglomeration due to poor interface bonding with the EP matrix, which hinders the heat conduction path. The interface compatibility between the modified Al

2O

3 and the EP matrix was significantly improved by the modification of silane coupling agent, and the agglomeration phenomenon was reduced, thus improving the thermal conductivity. In addition, particle size and filling amount also have a significant impact on thermal conductivity: Al

2O

3 particles with smaller particle size (such as 20 nm) can be more evenly dispersed in the EP matrix due to their larger specific surface area, forming more thermal conductivity channels, and thus showing higher thermal conductivity under high filling amount; The larger particle size (such as 200 nm) Al

2O

3 particles, although the thermal conductivity path is longer, can still significantly improve the thermal conductivity after modification. The reason why small particle size Al

2O

3 can be added in the resin is that its high specific surface area and surface energy, so that the interaction between the particles and the resin matrix is enhanced, and the modification treatment further optimizes the interface compatibility and reduces the agglomeration of particles, so that it can still maintain good dispersion and fluidity under high filling volume. From the perspective of thermal conductivity mechanism, the modified Al

2O

3 promotes the transfer of phonons between the filler and the matrix by improving the interface bonding and reducing the interface thermal resistance, while the uniformly dispersed filler forms a continuous heat conduction network, further enhancing the heat transfer efficiency.

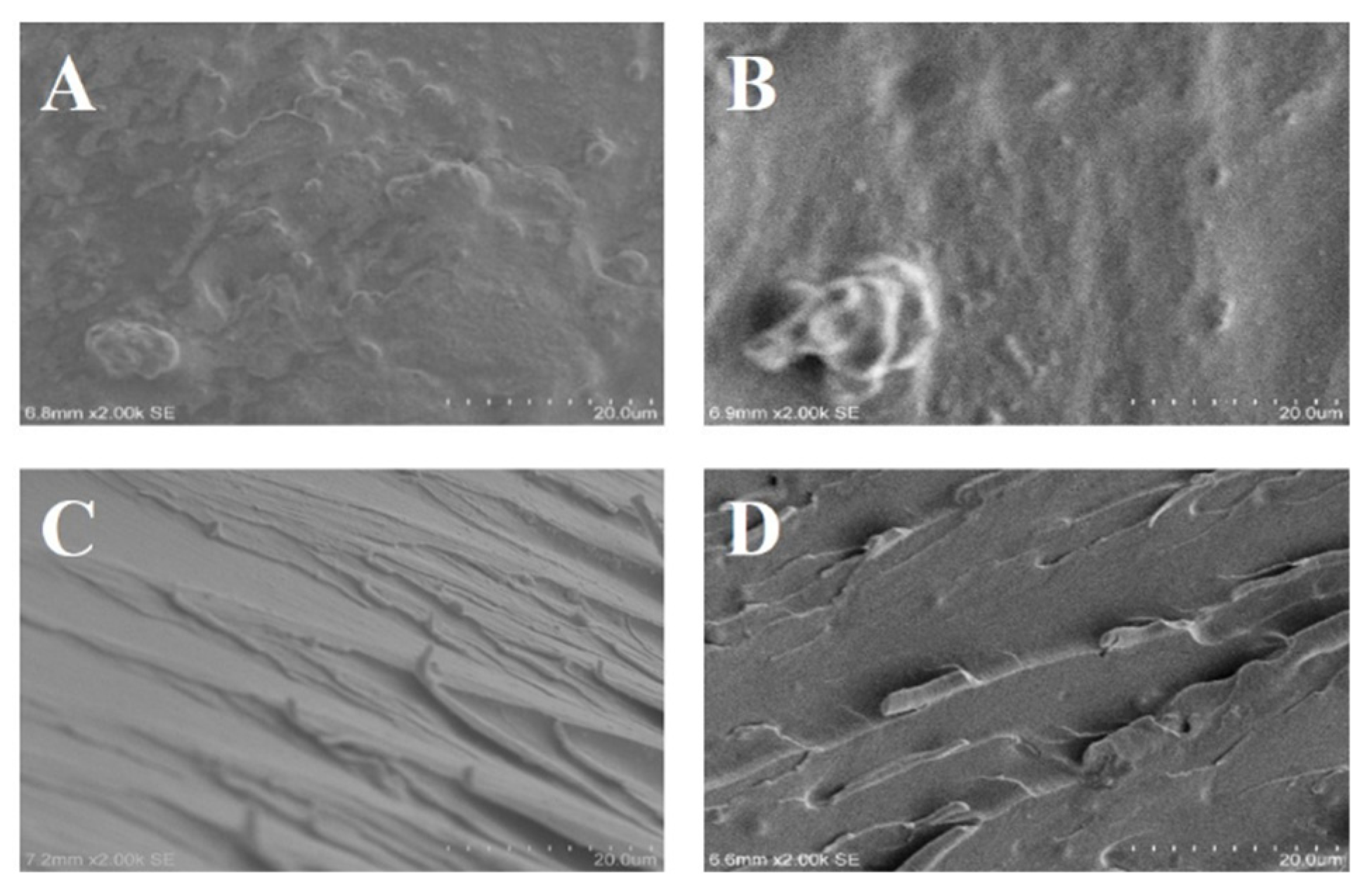

In order to further study the heat conduction mechanism of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composite, the cross section morphology of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composite was observed by low and high rate SEM, and the results are shown in

Figure 9. As can be seen from the figure, there are very obvious particles in the Al

2O

3/EP composite material before and after modification, most of these particles are isolated from each other, while a small number of particles are in contact with each other, thus providing a good path for heat transfer. Among them, the surfaces of

Figure 9A and B are river-like, showing obvious brittle fracture characteristics, indicating that the dispersion of unmodified Al

2O

3 in the EP matrix is poor, and the particle agglomeration phenomenon is significant, resulting in a large interface thermal resistance, which hindering the effective heat transfer. However, a small number of dimples appeared on the surface of the 20 nm Al

2O

3/EP composite, indicating that the addition of small particle size Al

2O

3 was conducive to the increase of toughness of the Al

2O

3/EP composite, but the distribution of dimples on the surface was uneven, which further confirmed that the agglomeration of unmodified Al

2O

3 in the resin matrix affected the formation of the thermal conductivity path. In addition, the 20 nm Al

2O

3/EP surface particles are more uniform than the 200 nm Al

2O

3/EP surface particles, indicating that the small particle size Al

2O

3 is more evenly dispersed in the EP resin, and the aggregated Al

2O

3 can not establish a good thermal conductivity path, resulting in its thermal conductivity can not be fully played.

Figure 9C and D show that the dimples on the surface of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composite are larger than those of the unmodified Al

2O

3/EP composite, and the surface of the 20 nm Al

2O

3/EP composite is very rough, showing the characteristics of ductile fracture, indicating that the modified small particle size Al

2O

3 can effectively improve the toughness of the material. In addition, the convex part of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composite is evenly dispersed, although there is still a small amount of agglomeration, but the texture is more, indicating that a continuous thermal conductivity path is formed, and the thermal conductivity of the material is significantly improved. This phenomenon is mainly attributed to the modification treatment (such as silane coupling agent modification) to optimize the interface bonding between Al

2O

3 and EP matrix, reduce interface defects and interface thermal resistance, and thus promote the transfer of phonons between the filler and the matrix. At the same time, the uniformly dispersed Al

2O

3 particles form a more continuous heat conduction network in the matrix, which further enhances the heat transfer efficiency.

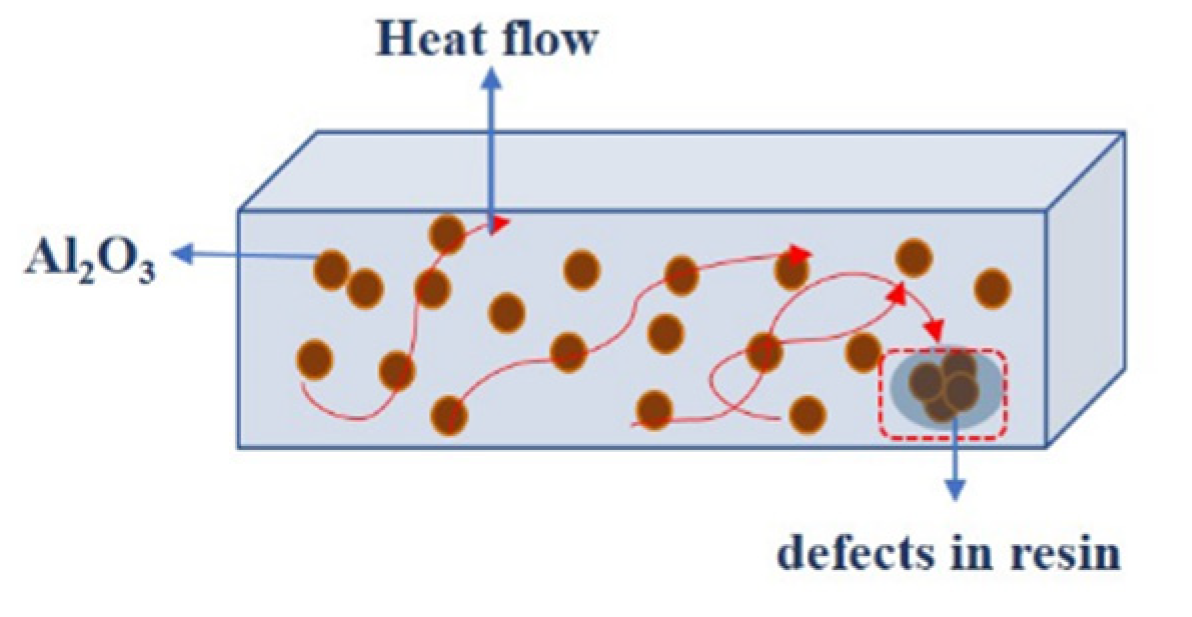

From the perspective of thermal conductivity mechanism, the modified Al

2O

3 significantly improves the heat conduction performance of the composite material by improving the interface compatibility and reducing the interface thermal resistance. Due to the larger specific surface area, small particle size Al

2O

3 can be more evenly dispersed in the EP matrix (as shown in

Figure 10), forming more thermal conductivity channels, thus showing higher thermal conductivity under high filling volume. The modified treatment further reduces the particle agglomeration phenomenon, optimizes the dispersion of the filler, and makes the heat conduction path more continuous and efficient. In addition, the improved toughness of the modified Al

2O

3/EP composite also indicates that the improved interface bonding not only contributes to heat conduction, but also enhances the mechanical properties of the material.

3.4. Thermal Resistant of the Materials

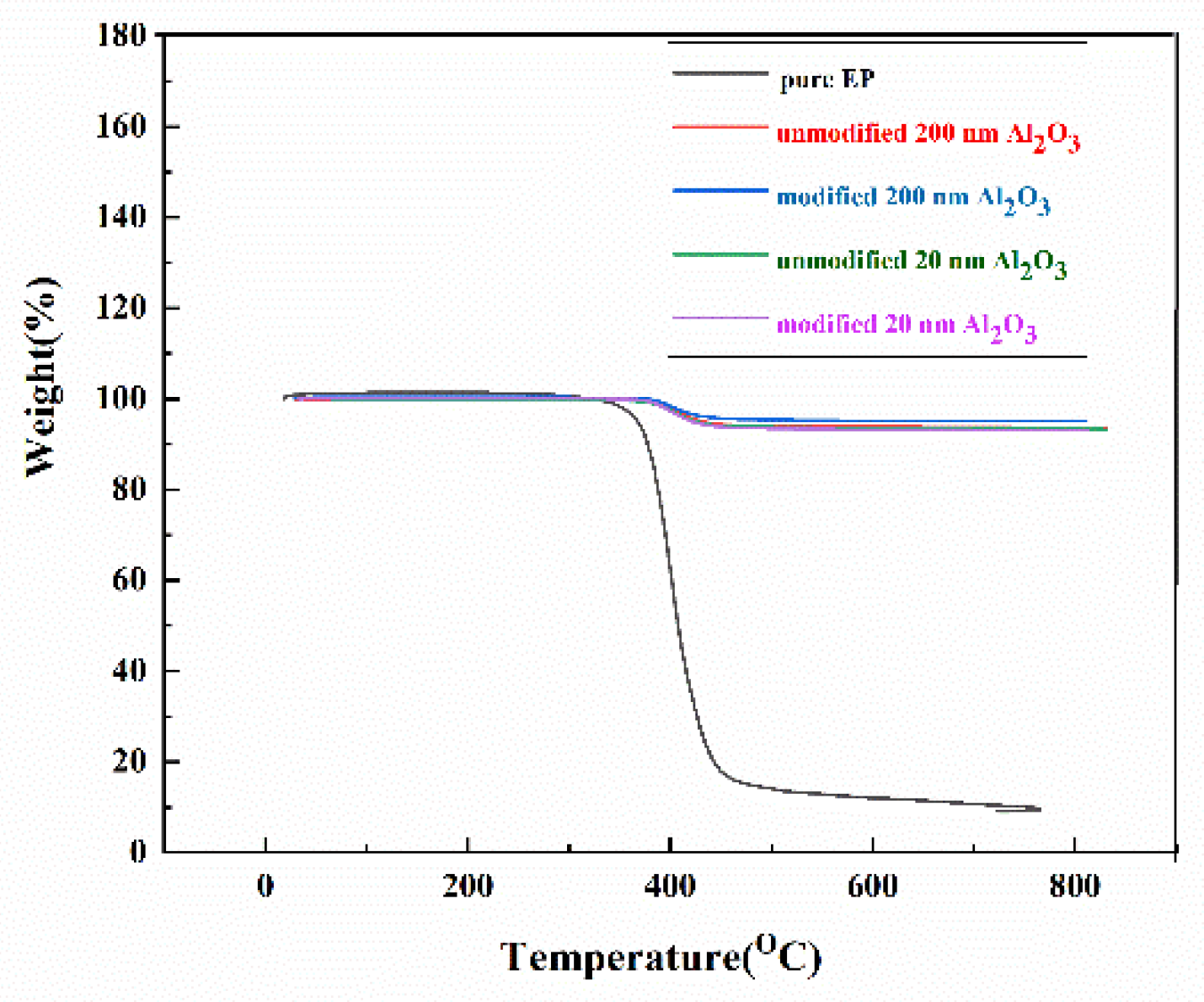

Figure 11 shows the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) results of pure EP resin, and Al

2O

3 content of 60 wt% Al

2O

3/EP. From the graph, it can be observed that as the temperature increases, the thermal decomposition behavior of the material exhibits distinct stage-wise changes. When the temperature approaches 400±20°C, the material begins to undergo significant thermal decomposition. This stage primarily includes two key reactions: first, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are released from the material; second, the thermal cracking of large-molecule, non-volatile components occurs, forming coke. Simultaneously, the released combustible volatile components undergo combustion reactions at high temperatures. As the temperature continues to rise to the range of 500~700°C, the material enters a deep carbonization stage. During this process, most of the organic components have already decomposed, and the remaining material mainly consists of carbonized products, resulting in a significant slowdown in the weight loss rate. When the temperature exceeds 700 °C, the thermal decomposition process of the material is essentially complete, and the weight stabilizes, showing no significant further changes. It is noteworthy that the introduction of nano-sized Al

2O

3 fillers significantly improves the thermal stability of epoxy resin (EP) composites. Experimental data show that at a high temperature of 800°C, Al

2O

3/EP composites prepared with Al

2O

3 fillers of 200 nm and 20 nm particle sizes exhibit excellent residual carbon rates, reaching 92%~93%. This value represents a significant improvement compared to pure epoxy resin, fully demonstrating that the incorporation of Al

2O

3 fillers effectively enhances the thermal stability of the composite material. Analysis of the reasons reveals that Al

2O

3 nanoparticles form an effective thermal barrier within the matrix, delaying the thermal decomposition process. The interfacial interactions between the nano-fillers and the polymer matrix enhance the material's thermal stability. Additionally, Al

2O

3 participates in the carbonization process, promoting the formation of a more stable carbon layer. The improvement in thermal resistance can also positively impact the material's thermal conductivity.