Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Characterization and Testing technique

3.1. Thermogravimetry Analysis (TGA)

3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.3. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

4. Result and Discussion

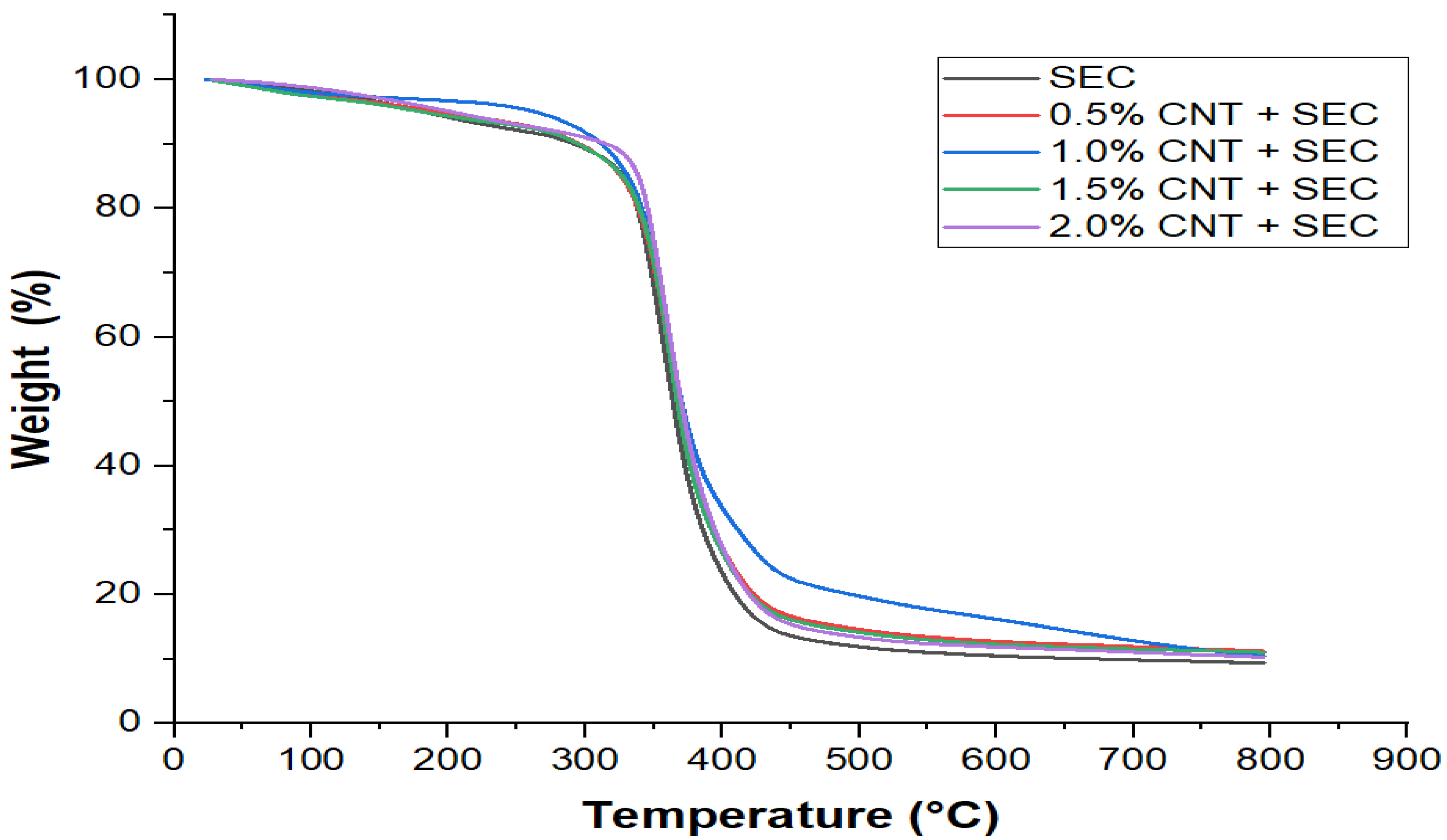

4.1. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

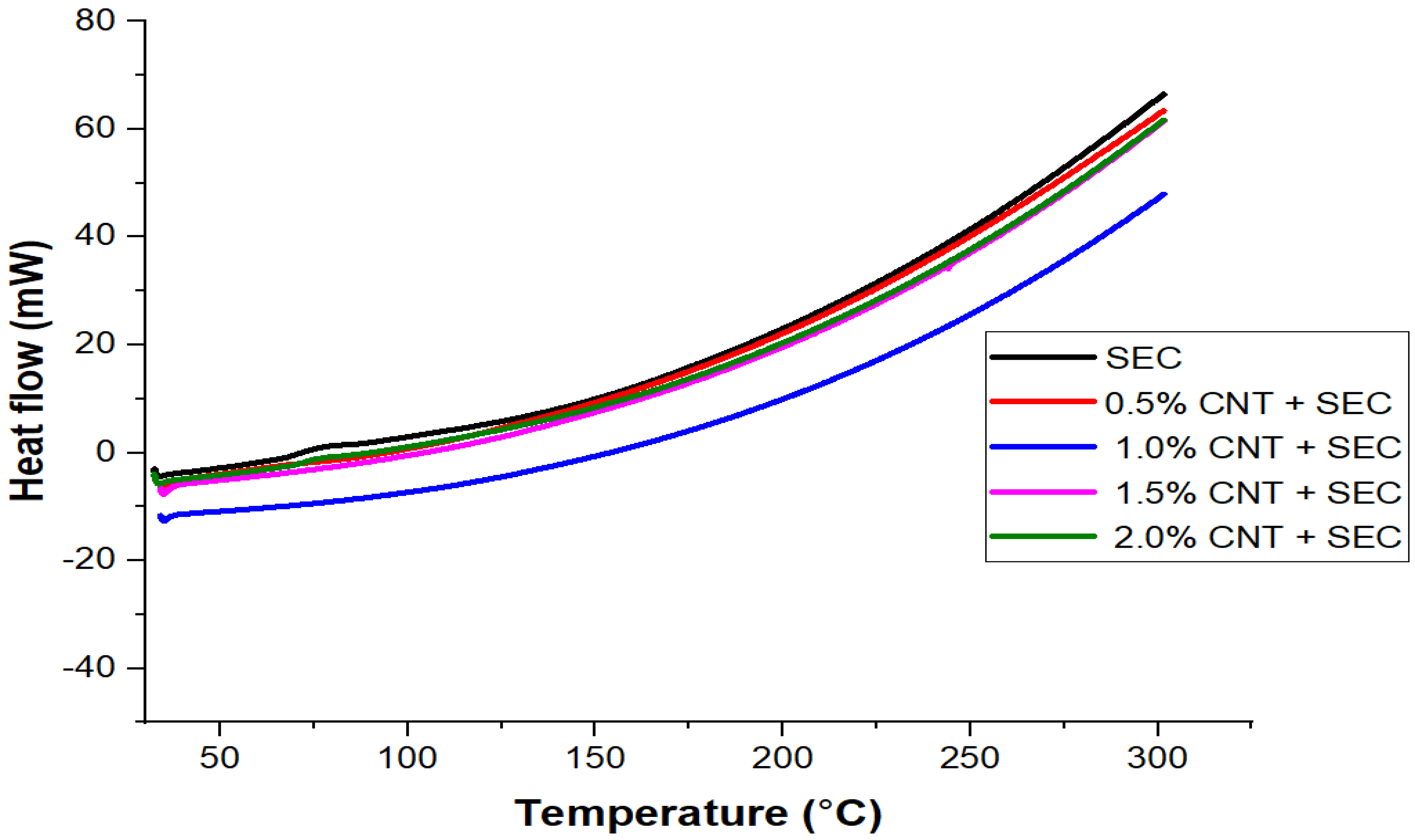

4.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

4.3. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

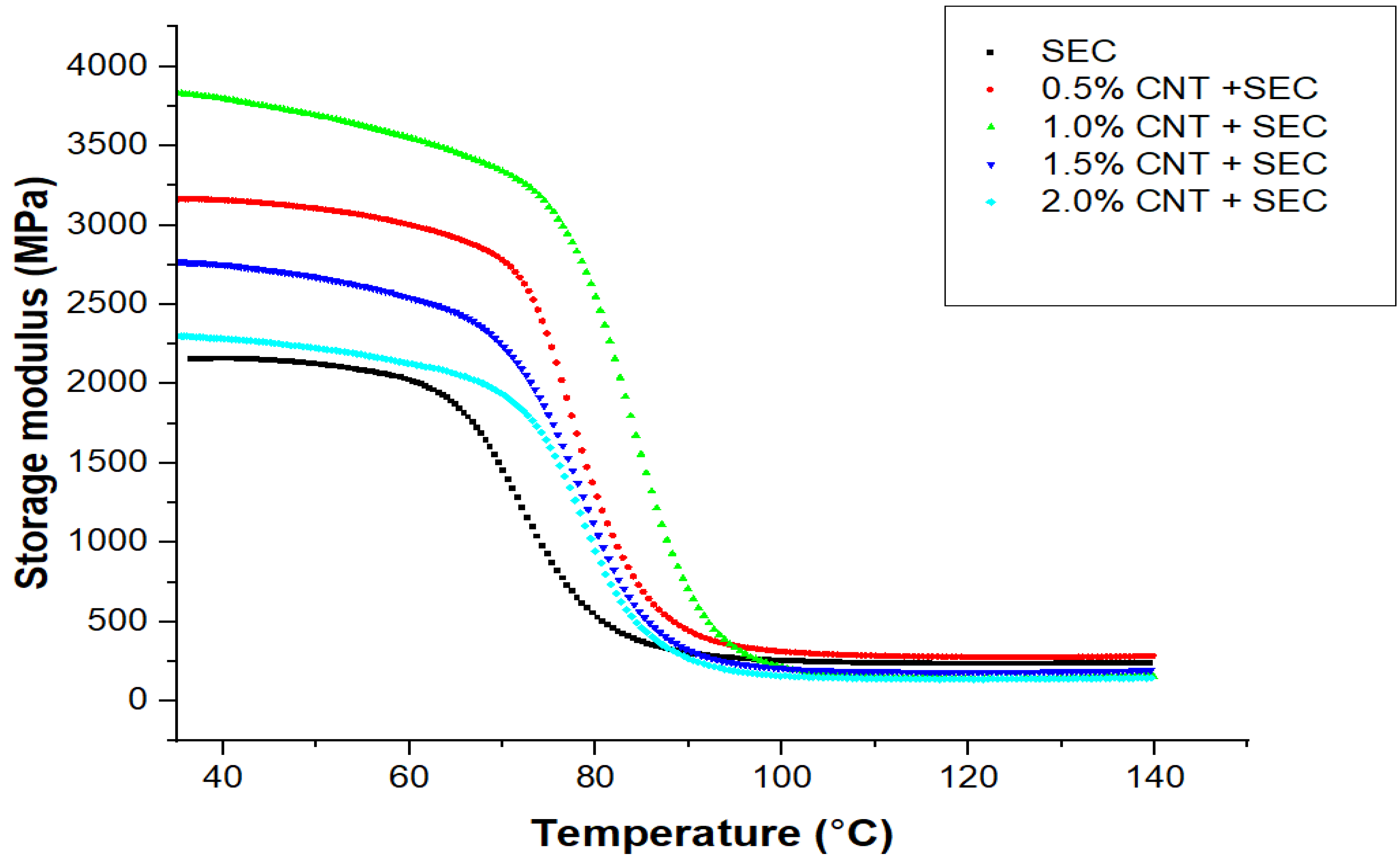

4.3.1. Storage Modulus

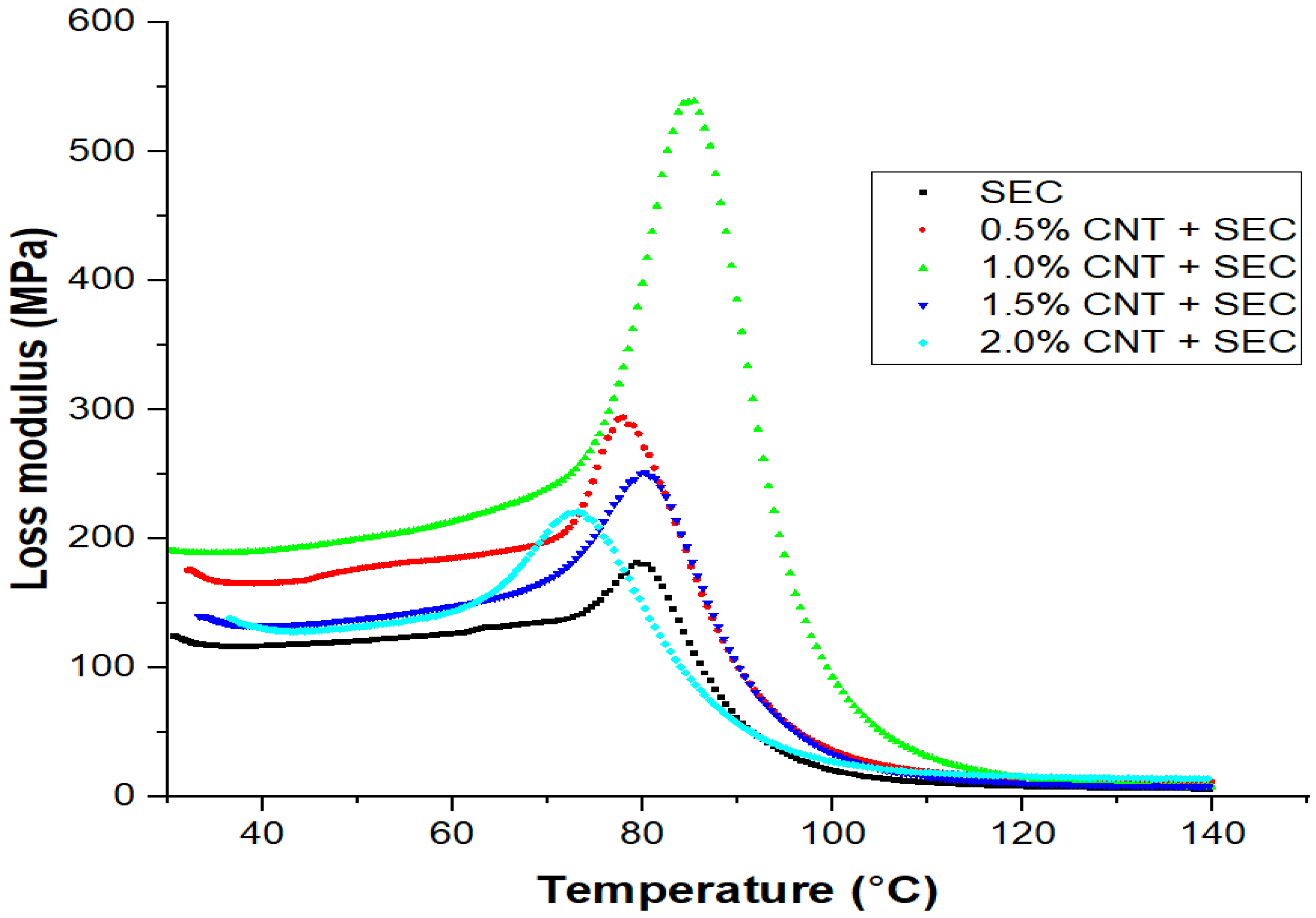

4.3.2. Loss Modulus

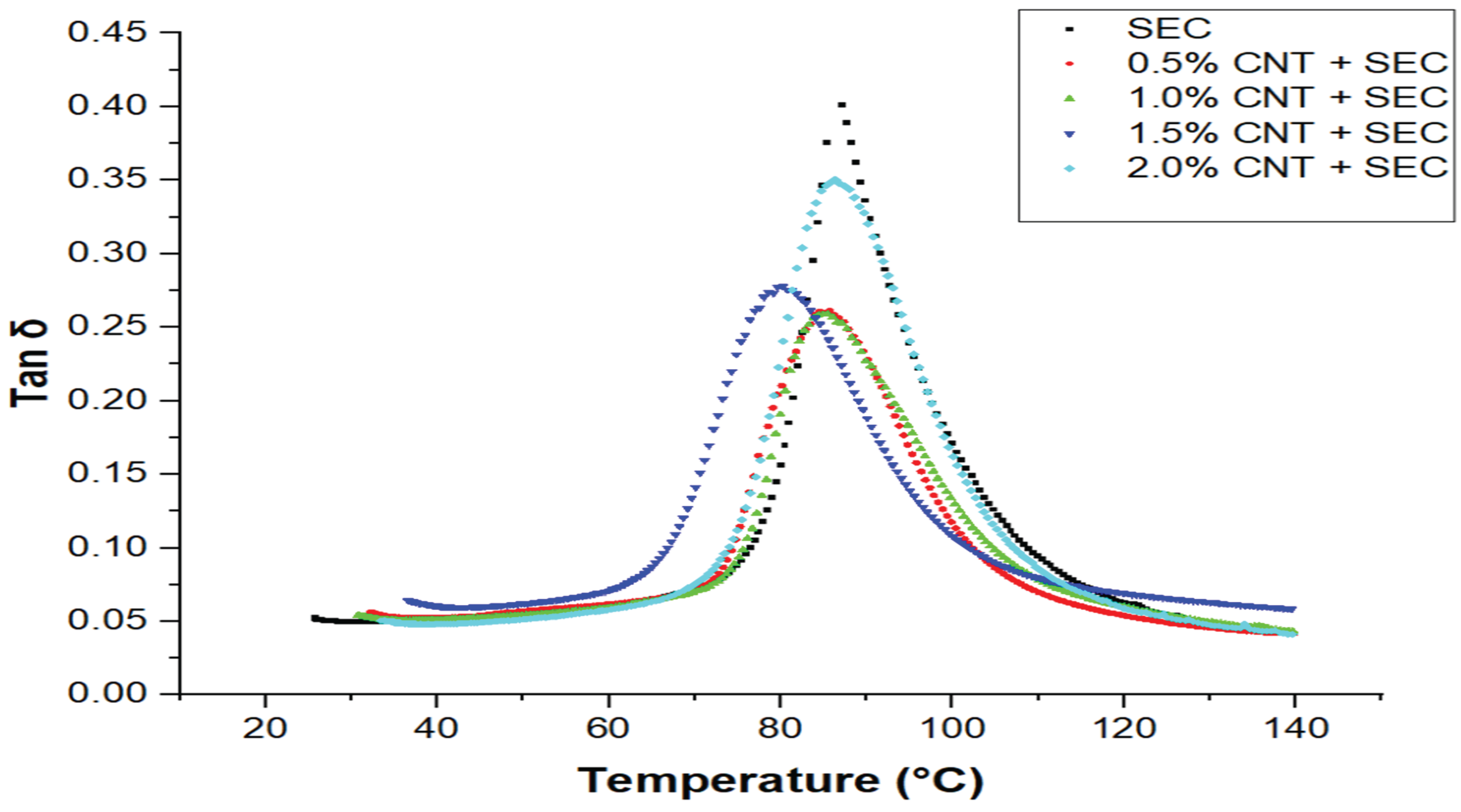

4.3.3. Damping Factor

| Biocomposites | Storage modulus E’(MPa) | Loss modulus E” (MPa) | Damping factor (Tan δ) | Glass temperature Tg (°C) at loss modulus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEC | 2159.37 | 181.63 | 0.58 | 80.16 |

| 0.5% CNT + SEC | 3165.60 | 294.34 | 0.26 | 85.68 |

| 1.0% CNT + SEC | 3859.28 | 539.44 | 0.25 | 89.26 |

| 1.5% CNT + SEC | 2773.18 | 251.35 | 0.28 | 86.34 |

| 2.0% CNT + SEC | 2306.484 | 221.01 | 0.35 | 85.78 |

5. Conclusions

- The thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) showed that all bio-composites undergo three main stages of degradation, with the lowest weight loss and thus highest thermal stability observed in the composite containing 1.0 wt.% CNT. Notably, this formulation exhibited the most resistance to thermal decomposition in the 100–380°C range, confirming the role of CNTs in enhancing the thermal resistance up to an optimal content level.

- The differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms showed a pronounced endothermic peak at 110°C, corresponding to moisture loss, particularly in composites with hydrophilic constituents such as cellulose and lignin from sisal fibers. Composites with 1.0 wt.% CNT showed increased crystallinity, leading to enhanced thermal stability.

- The storage modulus (E′), which reflects rigidity, was maximized at 1.0 wt.% CNT (3859.28 MPa), indicating optimal reinforcement and improved load-bearing capacity due to effective dispersion and interaction of CNTs within the matrix.

- Composites with 1.0 wt.% CNT exhibited the highest loss modulus and the lowest tan δ, indicating both superior stiffness and reduced energy dissipation—favorable traits for structural applications.

- The glass transition temperature (Tg) also peaked at 89.26°C in the 1.0 wt.% CNT composite, signifying increased thermal and dimensional stability.

Authors Contribution

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stachurski, Z. H. Fundamentals of Amorphous Solids : Structure and Properties; Wiley-Vch Verlag Gmbh & Co. Kgaa: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, A. Ancient Egyptian Materials; 1926.

- Kar, K. K. (Ed.) Composite Materials; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S. K. Composites Manufacturing : Materials, Product, and Process Engineering; Crc Press: Boca Raton, Fla, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Sudhakara, P.; Nijjar, S.; Saini, S.; Singh, G. Recent Progress of Composite Materials in Various Novel Engineering Applications. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 28195–28202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thostenson, E. T.; Ren, Z.; Chou, T.-W. Advances in the Science and Technology of Carbon Nanotubes and Their Composites: A Review. Composites Science and Technology 2001, 61(13), 1899–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mai, Y.-W.; Ye, L. Sisal Fibre and Its Composites: A Review of Recent Developments. Composites Science and Technology 2000, 60(11), 2037–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A. K.; Fink, H.-P.; Sain, M. Biocomposites Reinforced with Natural Fibers: 2000–2010. Progress in Polymer Science 2012, 37(11), 1552–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, K.; Thomas, S.; Pavithran, C. Effect of Chemical Treatment on the Tensile Properties of Short Sisal Fibre-Reinforced Polyethylene Composites. Polymer 1996, 37(23), 5139–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K. C. M.; Thomas, S. Effect of Interface Modification on the Mechanical Properties of Polystyrene-Sisal Fiber Composites. Polymer Composites 2003, 24(3), 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, K. P.; Menard, N. R. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis; CRC Press, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, K. Manufacturing Sisal–Polypropylene Composites with Minimum Fibre Degradation. Composites Science and Technology 2003, 63, (3–4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P. V.; Rabello, M. S.; Mattoso, L. H. C.; Joseph, K.; Thomas, S. Environmental Effects on the Degradation Behaviour of Sisal Fibre Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. Composites Science and Technology 2002, 62, (10–11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, M. Z.; Zhang, M. Q.; Liu, Y.; Yang, G. C.; Zeng, H. M. The Effect of Fiber Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of Unidirectional Sisal-Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Composites Science and Technology 2001, 61, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, P. A.; Joseph, K.; Unnikrishnan, G.; Thomas, S. A Comparative Study on Mechanical Properties of Sisal-Leaf Fibre-Reinforced Polyester Composites Prepared by Resin Transfer and Compression Moulding Techniques. Composites Science and Technology 2007, 67, (3–4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idicula, M.; Malhotra, S. K.; Joseph, K.; Thomas, S. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis of Randomly Oriented Intimately Mixed Short Banana/Sisal Hybrid Fibre Reinforced Polyester Composites. Composites Science and Technology 2005, 65, (7–8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Isaac, D. H. Fatigue Properties of Hemp and Glass Fiber Composites. Polymer Composites 2014, 35, 1926–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanese, A. C.; Cioffi, M. O. H.; Voorwald, H. J. C. Thermal and Mechanical Behaviour of Sisal/Phenolic Composites. Composites Part B: Engineering 2012, 43, 2843–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirao Ramachandrarao; Khan, S. H.; Abdullah, K. Carbon Nanotubes and Nanofibers – Reinforcement to Carbon Fiber Composites - Synthesis, Characterizations and Applications: A Review. Composites Part C Open Access 2024, 100551–100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, U. K.; M. Trihotri; Gupta, S. C.; Khan, F. H.; Malik, M. M.; Qureshi, M. S. Effect of Carbon Nanotubes Implantation on Electrical Properties of Sisal Fibre–Epoxy Composites. Composite interfaces 2016, 24, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G., Vijayasekaran; P., Selvaraju; Dominic, A.; Krishnamurthy, N. G. Vijayasekaran; P. Selvaraju; Dominic, A.; Krishnamurthy, N.; A. Yasminebegum; S. K. Hasane Ahammad. Mechanical Properties Evaluation of Carbon Nanotube/Sisal Fiber/Marble Dust Reinforced Polymer Based Composites. Materials Today: Proceedings 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.; Kumar, P. S.; Deeraj, B. D. S.; Joseph, K.; Jayanarayanan, K.; Mini, K. M. Modification of Epoxy Binder with Multi Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Hybrid Fiber Systems Used for Retrofitting of Concrete Structures: Evaluation of Strength Characteristics. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P. V.; Rabello, M. S.; Mattoso, L. H. C.; Joseph, K.; Thomas, S. Environmental Effects on the Degradation Behaviour of Sisal Fibre Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. Composites Science and Technology 2002, 62, (10–11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Drzal, L. T.; Qin, Y.; Huang, Z. Multifunctional Graphene Nanoplatelets/Cellulose Nanocrystals Composite Paper. Composites Part B: Engineering 2015, 79, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test Method for Plastics: Dynamic Mechanical Properties: In Tension. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Jorge Ananias Neto; Henrique; Ricardo C. T. Aguiar; Banea, M. D. A Review on the Thermal Characterisation of Natural and Hybrid Fiber Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 4425–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewelina Ciecierska; Boczkowska, A. ; Krzysztof Jan Kurzydlowski; Iosif Daniel Rosca; Suong Van Hoa. The Effect of Carbon Nanotubes on Epoxy Matrix Nanocomposites. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2012, 111, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. L.; Banea, M. D.; Neto, J. S. S.; Cavalcanti, D. K. K. Mechanical and Thermal Characterization of Natural Intralaminar Hybrid Composites Based on Sisal. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Wu, F.; Wang, J. Thermal Degradation Behavior of Epoxy Resin Containing Modified Carbon Nanotubes. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, F.; Mehmet Guclu; Koray Gurkan; Durmus, A. ; Yener Taskin. The Effect of Carbon Nanotubes Loading and Processing Parameters on the Electrical, Mechanical, and Viscoelastic Properties of Epoxy-Based Composites. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering 2022, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, S.-C.; Lin, K.-Y. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis of Carbon Nanotube-Reinforced Nanocomposites. Journal of Applied Biomaterials & Functional Materials 2017, 15, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh Kumar Rao, Prakash Chandra Gope, Fracture Toughness of Walnut Particles (Juglans regia L.) and Coconut Fibre Reinforced Hybrid Biocomposite. Journal of Polymer Composites, 2014, , Volume 36, Issue 1, pages 167–173. [CrossRef]

- Prakash Chandra Gope and Dinesh Kumar Rao, “Fracture behaviour of epoxy biocomposite reinforced with short coconut fibres (Cocos nucifera) and walnut particles (Juglans regia L.)” Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials,Vol 29, Issue 8, pages 1098-1117, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Prakash Chandra Gope, Vinay Kumar Singh, Dinesh Kumar Rao, “Mode I Fracture Toughness of Bio-fiber and Bio Shell Particle Reinforced Epoxy Bio-composites” Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites, Vol. 34 , Issue 13, p131075-1089, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dinesh Kumar Rao, “Tensile, Compressive and Flexural Behaviour with Characterization of Hybrid Bio-Composite Reinforced with Walnut Shell Particles and Coconut Fibres”. In the proceedings of International Society of Agile Manufacturing, Conference on Advanced and Agile Manufacturing System,KNIT Sultanpur support on TEQIP-II, International Society of Agile Manufacturing (ISAM), Dec 28-29,2015, p310-314.ISBN:978-93-85777-03-5.

- DK Rao, P Sharma, V Kumar, PK Agarwal, CK Kaithwas, "Introduction to thermo plastic polymer composites:applications, advantages, and drawbacks",Mechanical and Mathematical Modeling, Elsevier book in Dynamic Mechanical and Creep-Recovery Behavior of Polymer-Based Composites, p1-9. 2024. [CrossRef]

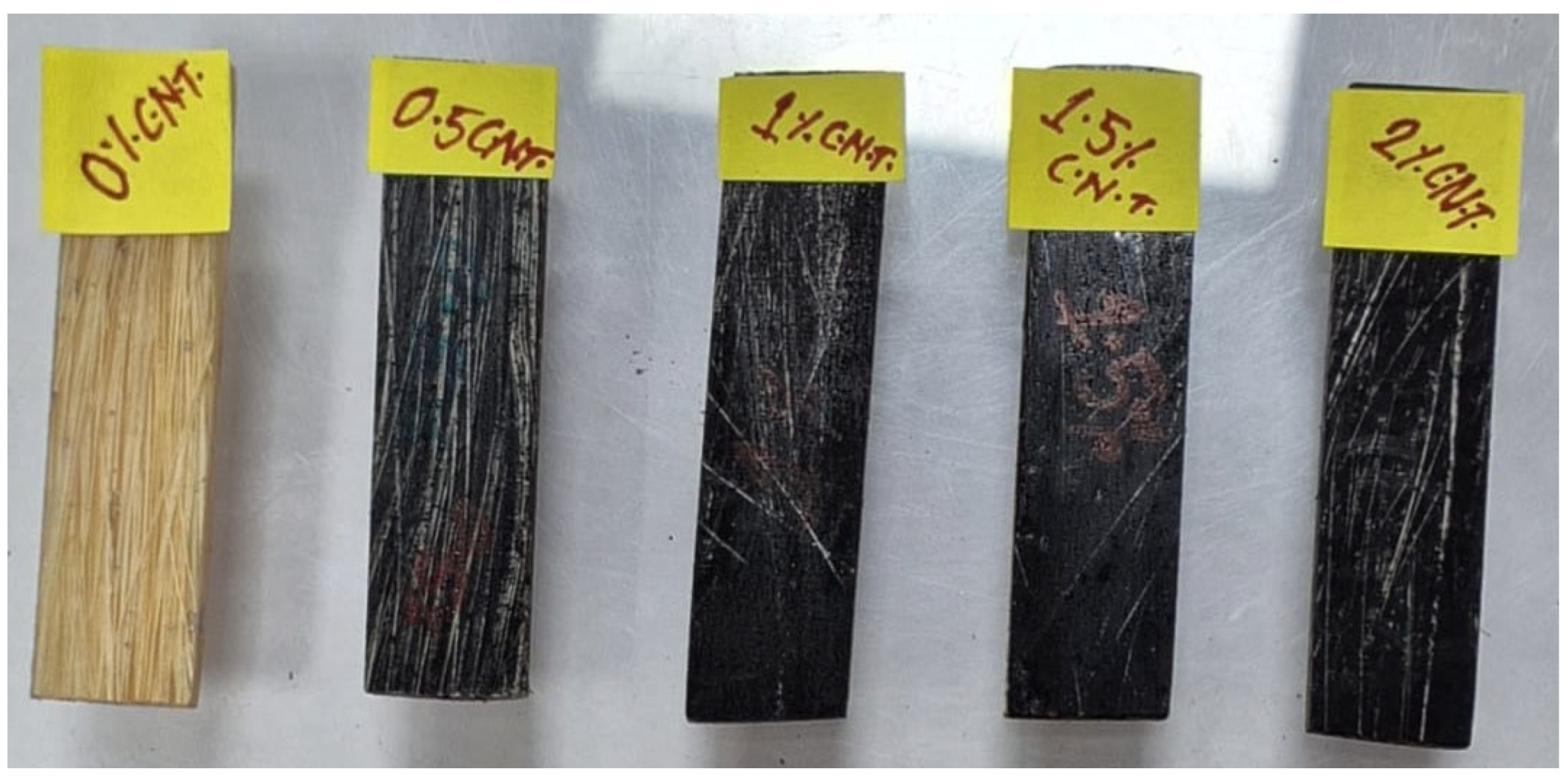

| Nomenclature | Specification of bio-composites |

|---|---|

| SEC | Sisal fibre (constant 15 wt.% loading) epoxy composite |

| SEC + 0.5% CNT | Sisal fibre (constant 15 wt.% loading) epoxy composite with 0.5 wt.% CNT additives |

| SEC + 1.0% CNT | Sisal fibre (constant 15 wt.% loading) epoxy composite with 1.0 wt.% CNT additives |

| SEC + 1.5% CNT | Sisal fibre (constant 15 wt.% loading) epoxy composite with 1.5 wt.% CNT additives |

| SEC + 2.0% CNT | Sisal fibre (constant 15 wt.% loading) epoxy composite with 2.0 wt.% CNT additives |

| Temperature (°C) | Weight loss (%) of bio-composites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEC | 0.5% CNT + SEC | 1.0% CNT + SEC | 1.5% CNT + SEC | 2.0% CNT + SEC | |

| 30-100 | 1.80 | 2.44 | 2.01 | 1.23 | 2.58 |

| 100-380 | 66.14 | 61.71 | 57.62 | 60.13 | 62.85 |

| 380-420 | 82.80 | 79.23 | 72.28 | 80.04 | 79.87 |

| 420-790 | 90.60 | 88.72 | 89.38 | 89.65 | 88.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).