Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Evidence of the Involvement of IgE Antibodies in COVID-19 and in Vaccination

2.1. Does SARS-CoV-2 Possess “Allergen-Like” Epitopes?

3. Allergen-Like Epitopes in HIV Envelope Proteins

4. The Role of IgE in RSV Infection

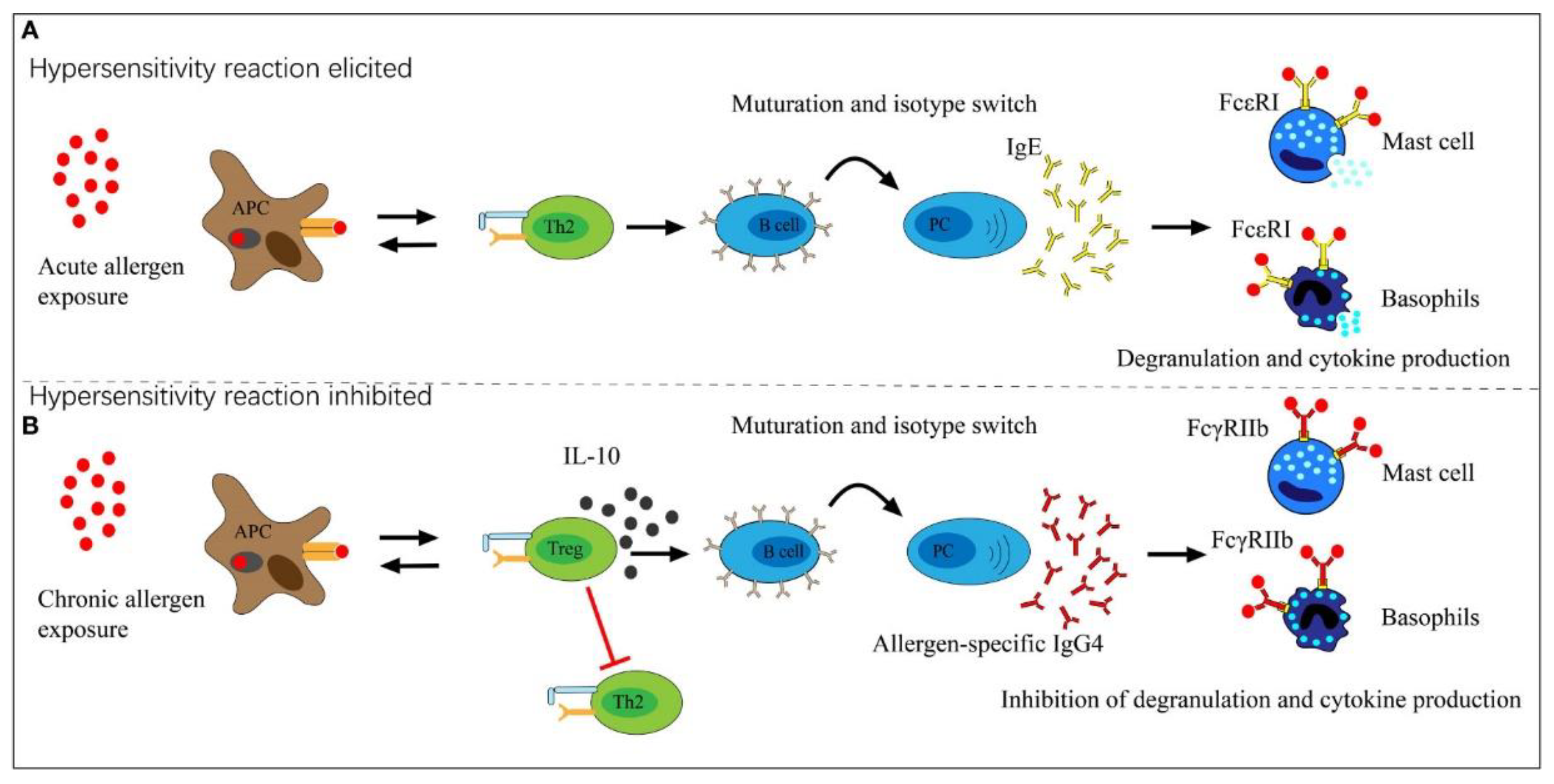

5. Repeated Vaccination with Allergen-Like Epitopes

6. Implications for Vaccine Design

- AlgPred 2.0 (https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/algpred2/), which uses multiple machine learning approaches to predict allergen-like sequences.

- AllergenFP (http://ddg-pharmfac.net/AllergenFP/), uses a descriptor-based fingerprint to detect potential allergens.

- BLASTp (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), finds regions of similarity between biological sequences. The program compares nucleotide or protein sequences to the sequence database and calculates the statistical significance.

- AlphaFold (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/), predicts protein structures for docking studies.

- Molecular docking (Autodock, HADDOCK) (https://rascar.science.uu.nl/haddock2.4/),

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeSilva, M.B.; Mitchell, P.K.; Klein, N.P.; Dixon, B.E.; Tenforde, M.W.; Thompson, M.G.; Naleway, A.L.; Grannis, S.J.; Ong, T.C.; Natarajan, K. Protection of two and three mRNA vaccine doses against severe outcomes among adults hospitalized with COVID-19—Vision Network, August 2021 to March 2022. The Journal of infectious diseases 2023, 227, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde, M.W.; Self, W.H.; Adams, K.; Gaglani, M.; Ginde, A.A.; McNeal, T.; Ghamande, S.; Douin, D.J.; Talbot, H.K.; Casey, J.D. Association between mRNA vaccination and COVID-19 hospitalization and disease severity. Jama 2021, 326, 2043–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauring, A.S.; Tenforde, M.W.; Chappell, J.D.; Gaglani, M.; Ginde, A.A.; McNeal, T.; Ghamande, S.; Douin, D.J.; Talbot, H.K.; Casey, J.D. Clinical severity of, and effectiveness of mRNA vaccines against, covid-19 from omicron, delta, and alpha SARS-CoV-2 variants in the United States: prospective observational study. bmj 2022, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde, M.W.; Self, W.H.; Zhu, Y.; Naioti, E.A.; Gaglani, M.; Ginde, A.A.; Jensen, K.; Talbot, H.K.; Casey, J.D.; Mohr, N.M. Protection of mRNA vaccines against hospitalized COVID-19 in adults over the first year following authorization in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2022, ciac381.

- Sibanda, B.; Haryanto, B. Assessing the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination Programs on the Reduction of COVID-19 Cases: A Systematic Literature Review. Annals of Global Health 2024, 90, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rispens, T.; Huijbers, M.G. The unique properties of IgG4 and its roles in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology 2023, 23, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidarsson, G.; Dekkers, G.; Rispens, T. IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions. Frontiers in immunology 2014, 5, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispens, T.; Ooijevaar-de Heer, P.; Bende, O.; Aalberse, R.C. Mechanism of immunoglobulin G4 Fab-arm exchange. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2011, 133, 10302–10311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalberse, R.; Stapel, S.; Schuurman, J.; Rispens, T. Immunoglobulin G4: an odd antibody. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2009, 39, 469–477. [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman, J.; Van Ree, R.; Perdok, G.a.; Van Doorn, H.; Tan, K.; Aalberse, R. Normal human immunoglobulin G4 is bispecific: it has two different antigen-combining sites. Immunology 1999, 97, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Neut Kolfschoten, M.; Schuurman, J.; Losen, M.; Bleeker, W.K.; Martínez-Martínez, P.; Vermeulen, E.; Den Bleker, T.H.; Wiegman, L.; Vink, T.; Aarden, L.A. Anti-inflammatory activity of human IgG4 antibodies by dynamic Fab arm exchange. Science 2007, 317, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Akdis, C.; Blaser, K. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy. Allergy 2000, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdis, M. Healthy immune response to allergens: T regulatory cells and more. Current opinion in immunology 2006, 18, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larché, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Valenta, R. Immunological mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Immunology 2006, 6, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durham, S.R.; Walker, S.M.; Varga, E.-M.; Jacobson, M.R.; O'Brien, F.; Noble, W.; Till, S.J.; Hamid, Q.A.; Nouri-Aria, K.T. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. New England Journal of Medicine 1999, 341, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosroshahi, A.; Stone, J.H. A clinical overview of IgG4-related systemic disease. Current opinion in rheumatology 2011, 23, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della-Torre, E.; Lanzillotta, M.a.; Doglioni, C. Immunology of IgG4-related disease. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 2015, 181, 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Shiokawa, M.; Kodama, Y.; Kuriyama, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Tomono, T.; Morita, T.; Kakiuchi, N.; Matsumori, T.; Mima, A.; Nishikawa, Y. Pathogenicity of IgG in patients with IgG4-related disease. Gut 2016, 65, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Tang, L.-F.; Cheng, L.; Wang, H.-Y. The clinical significance of allergen-specific IgG4 in allergic diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 1032909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flicker, S.; Valenta, R. Renaissance of the blocking antibody concept in type I allergy. International archives of allergy and immunology 2003, 132, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachholz, P.A.; Durham, S.R. Mechanisms of immunotherapy: IgG revisited. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 2004, 4, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, D.B.; Meyers, D.A.; Kagey-Sobotka, A.; Valentine, M.D.; Lichtenstein, L.M. Clinical relevance of the venom-specific immunoglobulin G antibody level during immunotherapy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1982, 69, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, U.; Helbling, A.; Bischof, M. Predictive value of venom-specific IgE, IgG and IgG subclass antibodies in patients on immunotherapy with honey bee venom. Allergy 1989, 44, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri-Aria, K.T.; Wachholz, P.A.; Francis, J.N.; Jacobson, M.R.; Walker, S.M.; Wilcock, L.K.; Staple, S.Q.; Aalberse, R.C.; Till, S.J.; Durham, S.R. Grass pollen immunotherapy induces mucosal and peripheral IL-10 responses and blocking IgG activity. The Journal of Immunology 2004, 172, 3252–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamji, M.; Ljørring, C.; Francis, J.; A Calderon, M.; Larche, M.; Kimber, I.; Frew, A.; Ipsen, H.; Lund, K.; Würtzen, P. Functional rather than immunoreactive levels of IgG4 correlate closely with clinical response to grass pollen immunotherapy. Allergy 2012, 67, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiler, F.; Klunker, S.; Zimmermann, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M. Distinct regulation of IgE, IgG4 and IgA by T regulatory cells and toll-like receptors. Allergy 2008, 63, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy: multiple suppressor factors at work in immune tolerance to allergens. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2014, 133, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Redwan, E.M.; Makis, W.; Rubio-Casillas, A. IgG4 Antibodies Induced by Repeated Vaccination May Generate Immune Tolerance to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Vaccines 2023, 11, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrgang, P.; Gerling, J.; Kocher, K.; Lapuente, D.; Steininger, P.; Habenicht, K.; Wytopil, M.; Beileke, S.; Schäfer, S.; Zhong, J. Class switch toward noninflammatory, spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Science immunology 2022, 8, eade2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhre, J.S.; Pongracz, T.; Künsting, I.; Lixenfeld, A.S.; Wang, W.; Nouta, J.; Lehrian, S.; Schmelter, F.; Lunding, H.B.; Dühring, L. mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 induce comparably low long-term IgG Fc galactosylation and sialylation levels but increasing long-term IgG4 responses compared to an adenovirus-based vaccine. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiszel, P.; Sík, P.; Miklós, J.; Kajdácsi, E.; Sinkovits, G.; Cervenak, L.; Prohászka, Z. Class switch towards spike protein-specific IgG4 antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination depends on prior infection history. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmenegger, M.; Fiedler, S.; Brugger, S.D.; Devenish, S.R.; Morgunov, A.S.; Ilsley, A.; Ricci, F.; Malik, A.Y.; Scheier, T.; Batkitar, L. Both COVID-19 infection and vaccination induce high-affinity cross-clade responses to SARS-CoV-2 variants. Iscience 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, K.J.; Ramanathan, P.; Haycroft, E.R.; Reynaldi, A.; Cromer, D.; Tan, C.W.; Wang, L.-F.; Wines, B.D.; Hogarth, P.M.; Downie, L.E. Preexisting immunity restricts mucosal antibody recognition of SARS-CoV-2 and Fc profiles during breakthrough infections. JCI insight 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valk, A.M.; Keijser, J.B.; van Dam, K.P.; Stalman, E.W.; Wieske, L.; Steenhuis, M.; Kummer, L.Y.; Spuls, P.I.; Bekkenk, M.W.; Musters, A.H. Suppressed IgG4 class switching in dupilumab-and TNF inhibitor-treated patients after mRNA vaccination. Allergy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, G.E.; Fryer, H.A.; Gill, P.A.; Boo, I.; Bornheimer, S.J.; Hogarth, P.M.; Drummer, H.E.; O'Hehir, R.E.; Edwards, E.S.; van Zelm, M.C. Third dose COVID-19 mRNA vaccine enhances IgG4 isotype switching and recognition of Omicron subvariants by memory B cells after mRNA but not adenovirus priming. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.2009. 2015.557929.

- Farkash, I.; Feferman, T.; Cohen-Saban, N.; Avraham, Y.; Morgenstern, D.; Mayuni, G.; Barth, N.; Lustig, Y.; Miller, L.; Shouval, D.S. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies elicited by COVID-19 mRNA vaccine exhibit a unique glycosylation pattern. Cell Reports 2021, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, J.; Ardizzone, C.M.; Khanna, M.; Trauth, A.J.; Hagensee, M.E.; Ramsay, A.J. Dynamics of Serum-Neutralizing Antibody Responses in Vaccinees through Multiple Doses of the BNT162b2 Vaccine. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, M.; Sakamoto, A.; Ozuru, R.; Kurihara, Y.; Itoh, R.; Ishii, K.; Shimizu, A.; Chou, B.; Nabeshima, S.; Hiromatsu, K. The appearance of anti-spike receptor binding domain immunoglobulin G4 responses after repetitive immunization with messenger RNA-based COVID-19 vaccines. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024, 139, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, M.; Islam, M.R.; Khaton, F.; Soltana, U.H.; Jafrin, S.A.; Rahman, S.I.A.; Tauheed, I.; Ahmed, T.; Khan, I.I.; Akter, A. Appearance of tolerance-induction and non-inflammatory SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after COVID-19 booster vaccinations. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, A.M.; Armina-Rodriguez, A.; Alvarez, L.; Ocasio-Malavé, C.; Ramos-Nieves, R.; Rodriguez Martinó, E.I.; López-Marte, P.; Torres, E.A.; Sariol, C.A. The Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG1 and IgG3 Antibody Isotypes with Limited Neutralizing Capacity against Omicron Elicited in a Latin Population a Switch toward IgG4 after Multiple Doses with the mRNA Pfizer–BioNTech Vaccine. Viruses 2024, 16, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, B.; Oltz, E.; Bednash, J.; Horowitz, J.; Rubinstein, M.; Vlasova, A.N. Brief Research Report: Impact of vaccination on antibody responses and mortality from severe COVID-19. Frontiers in Immunology 15, 1325243.

- Kalkeri, R.; Zhu, M.; Cloney-Clark, S.; Plested, J.S.; Parekh, A.; Gorinson, D.; Cai, R.; Mahato, S.; Ramanathan, P.; Aurelia, L.C. Altered IgG4 Antibody Response to Repeated mRNA versus Protein COVID Vaccines. medRxiv 2024, 2024.2001. 2017.24301374.

- Nziza, N.; Deng, Y.; Wood, L.; Dhanoa, N.; Dulit-Greenberg, N.; Chen, T.; Kane, A.S.; Swank, Z.; Davis, J.P.; Demokritou, M. Humoral profiles of toddlers and young children following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Kumar, S.; Lai, L.; Linderman, S.; Malik, A.A.; Ellis, M.L.; Godbole, S.; Solis, D.; Sahoo, M.K.; Bechnak, K. XBB. 1.5 monovalent booster improves antibody binding and neutralization against emerging SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.2002. 2003.578771.

- Portilho, A.I.; Silva, V.O.; Da Costa, H.H.M.; Yamashiro, R.; de Oliveira, I.P.; de Campos, I.B.; Prudencio, C.R.; Matsuda, E.M.; de Macedo Brígido, L.F.; De Gaspari, E. An unexpected IgE anti-receptor binding domain response following natural infection and different types of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 20003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routhu, N.K.; Stampfer, S.D.; Lai, L.; Akhtar, A.; Tong, X.; Yuan, D.; Chicz, T.M.; McNamara, R.P.; Jakkala, K.; Davis-Gardner, M.E. Efficacy of mRNA-1273 and Novavax ancestral or BA. 1 spike booster vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 BA. 5 infection in non-human primates. Science Immunology 2023, eadg7015.

- Valk, A.M.; Keijser, J.B.; van Dam, K.P.; Stalman, E.W.; Wieske, L.; Steenhuis, M.; Kummer, L.Y.; Spuls, P.I.; Bekkenk, M.W.; Musters, A.H. Suppressed IgG4 class switching in dupilumab-and TNF inhibitor-treated patients after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. medRxiv 2023, 2023.2009. 2029.23296354.

- Liu, Z.; Cai, L.; Xing, M.; Qiao, N.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Tang, N.; Xu, Z.; Guo, Y. Evaluation of antibody responses in healthy individuals receiving SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccines. Biosafety and Health 2024, 6, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Matsumoto, Y.; Shirai, A.; Okubo, T. Influenza A virus infection increases IgE production and airway responsiveness in aerosolized antigen-exposed mice. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 1998, 102, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakhama, A.; Lee, Y.-M.; Ohnishi, H.; Jing, X.; Balhorn, A.; Takeda, K.; Gelfand, E.W. Virus-specific IgE enhances airway responsiveness on reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus in newborn mice. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2009, 123, 138–145. e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guclu, O.A.; Goktas, S.S.; Dilektasli, A.G.; Ozturk, N.A.A.; Demirdogen, E.; Coskun, F.; Ediger, D.; Ursavas, A.; Uzaslan, E.; Erol, H.A. A pilot study for IgE as a prognostic biomarker in COVID-19. Internal Medicine Journal 2022, 10.1111/imj. 15728.

- Ferastraoaru, D.; Hudes, G.; Jerschow, E.; Jariwala, S.; Karagic, M.; de Vos, G.; Rosenstreich, D.; Ramesh, M. Eosinophilia in asthma patients is protective against severe COVID-19 illness. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice 2021, 9, 1152–1162. e1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-j.; Dong, X.; Cao, Y.-y.; Yuan, Y.-d.; Yang, Y.-b.; Yan, Y.-q.; Akdis, C.A.; Gao, Y.-d. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020, 75, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Tu, L.; Zhu, P.; Mu, M.; Wang, R.; Yang, P.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Ping, R.; Hu, P. Clinical features of 85 fatal cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan. A retrospective observational study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2020, 201, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo-Muñoz, J.; Sastre, B.; Cañas, J.; Gil-Martínez, M.; Redondo, N.; Del Pozo, V. Eosinophil response against classical and emerging respiratory viruses: COVID-19. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2021, 31, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plūme, J.; Galvanovskis, A.; Šmite, S.; Romanchikova, N.; Zayakin, P.; Linē, A. Early and strong antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 predict disease severity in COVID-19 patients. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022, 20, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.M.; Jackson, K.J. A temporal model of human IgE and IgG antibody function. Frontiers in immunology 2013, 4, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannin, P.; Delneste, Y.; Lecoanet-Henchoz, S.; Gretener, D.; Bonnefoy, J.-Y. Interleukin-7 (IL-7) enhances class switching to IgE and IgG4 in the presence of T cells via IL-9 and sCD23. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 1998, 91, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zou, Y.; Hu, Z. Advances in aluminum hydroxide-based adjuvant research and its mechanism. 2015.

- Kinet, J.-P. The high-affinity IgE receptor (FcϵRI): from physiology to pathology. Annual review of immunology 1999, 17, 931–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempuraj, D.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Ahmed, M.E.; Raikwar, S.P.; Thangavel, R.; Khan, A.; Zaheer, S.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Burton, C.; James, D. COVID-19, mast cells, cytokine storm, psychological stress, and neuroinflammation. The Neuroscientist 2020, 26, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Afrin, L.B.; Weinstock, L.B.; Molderings, G.J. Covid-19 hyperinflammation and post-Covid-19 illness may be rooted in mast cell activation syndrome. International journal of infectious diseases 2020, 100, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta Junior, J.d.S.; Miggiolaro, A.F.R.d.S.; Nagashima, S.; De Paula, C.B.V.; Baena, C.P.; Scharfstein, J.; De Noronha, L. Mast cells in alveolar septa of COVID-19 patients: a pathogenic pathway that may link interstitial edema to immunothrombosis. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 574862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmani, A.R.; Mahdavinezhad, F.; Moslemi, R.; Mehrabi, Z.; Noori, A.; Kouhestani, M.; Noroozi, Z.; Ai, J.; Rezaei, N. Anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies as potential treatment in COVID-19. Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology 2021, 43, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frasca, D.; Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; Mendez, N.V.; Landin, A.M.; Blomberg, B.B. Effects of age on H1N1-specific serum IgG1 and IgG3 levels evaluated during the 2011–2012 influenza vaccine season. Immunity & ageing 2013, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cavacini, L.A.; Kuhrt, D.; Duval, M.; Mayer, K.; Posner, M.R. Binding and neutralization activity of human IgG1 and IgG3 from serum of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS research and human retroviruses 2003, 19, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suthar, M.S.; Zimmerman, M.G.; Kauffman, R.C.; Mantus, G.; Linderman, S.L.; Hudson, W.H.; Vanderheiden, A.; Nyhoff, L.; Davis, C.W.; Adekunle, O. Rapid generation of neutralizing antibody responses in COVID-19 patients. Cell Reports Medicine 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzini, L.; Martinuzzi, D.; Hyseni, I.; Benincasa, L.; Molesti, E.; Casa, E.; Lapini, G.; Piu, P.; Trombetta, C.M.; Marchi, S. Comparative analyses of SARS-CoV-2 binding (IgG, IgM, IgA) and neutralizing antibodies from human serum samples. Journal of Immunological Methods 2021, 489, 112937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.N.; Nelson Jr, R.P.; Ledford, D.K.; Fernandez-Caldas, E.; Trudeau, W.L.; Lockey, R.F. Serum IgE and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 1990, 85, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, A.J.; Abrams, D.; Conant, M.; Chudwin, D.; Cowan, M.; Volberding, P.; Lewis, B.; Casavant, C. Acquired immune dysfunction in homosexual men: immunologic profiles. Clinical immunology and immunopathology 1983, 27, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, J.; Fröschl, M.; Brunner, R.; Braun-Falco, O. LAV/HTLV-III infection and atopy: serum IgE and specific IgE antibodies to environmental allergens. Acta dermato-venereologica 1986, 66, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.Y. Chronic diffuse dermatitis and hyper-IgE in HIV infection. Acta dermato-venereologica 1988, 68, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miguez-Burbano, M.; Shor-Posner, G.; Fletcher, M.A.; Lu, Y.; Moreno, J.; Carcamo, C.; Page, B.; Quesada, J.; Sauberlich, H.; Baum, M. Immunoglobulin E levels in relationship to HIV-1 disease, route of infection, and vitamin E status. Allergy 1995, 50, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouaaz, F.; Ruscetti, F.W.; Dugas, B.; Mikovits, J.; Agut, H.; Debr, P.; Mossalayi, M.D. Role of IgE Immune Complexes in the Regulation of HIV-1 Replication and Increased Cell Death of Infected U1 Monocytes: Involvement of CD23/Fc ε RII-Mediated Nitric Oxide and Cyclic AMP Pathways. Molecular Medicine 1996, 2, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellaurie, M.; Rubinstein, A.; Rosenstreich, D.L. IgE levels in pediatric HIV-1 infection. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology: official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology 1995, 75, 332–336. [Google Scholar]

- Israël-Biet, D.; Labrousse, F.; Tourani, J.-M.; Sors, H.; Andrieu, J.-M.; Even, P. Elevation of IgE in HIV-infected subjects: a marker of poor prognosis. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 1992, 89, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LUCEY, D.R.; ZAJAC, R.A.; MELCHER, G.P.; BUTZIN, C.A.; BOSWELL, R.N. Serum IgE levels in 622 persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection: IgE elevation with marked depletion of CD4+ T-cells. AIDS research and human retroviruses 1990, 6, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor-Posner, G.; Miguez-Burbano, M.J.; Lu, Y.; Feaster, D.; Fletcher, M.; Sauberlich, H.; Baum, M.K. Elevated IgE level in relationship to nutritional status and immune parameters in early human immunodeficiency virus–1 disease. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 1995, 95, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bul, R.H.D.; Molinaro, G.A.; Kettering, J.D.; Heiner, D.C.; Imagawa, D.T.; Geme Jr, J.W.S. Virus-specific IgE and IgG4 antibodies in serum of children infected with respiratory syncytial virus. The Journal of pediatrics 1987, 110, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Y. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) evades the human adaptive immune system by skewing the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance toward increased levels of Th2 cytokines and IgE, markers of allergy—a review. Virus genes 2006, 33, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Welliver, R.C.; Sun, M.; Rinaldo, D.; Ogra, P.L. Respiratory syncytial virus-specific IgE responses following infection: evidence for a predominantly mucosal response. Pediatric research 1985, 19, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith-Norowitz, T.A.; Josekutty, J.; Silverberg, J.I.; Lev-Tov, H.; Norowitz, Y.M.; Kohlhoff, S.; Nowakowski, M.; Durkin, H.G.; Bluth, M.H. Long term persistence of IgE anti-Varicella Zoster Virus in pediatric and adult serum post chicken pox infection and after vaccination with Varicella Virus vaccine. International Journal of Biomedical Science: IJBS 2009, 5, 353. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Norowitz, T.A.; Tam, E.; Norowitz, K.B.; Chotikanatis, K.; Weaver, D.; Durkin, H.G.; Bluth, M.H.; Kohlhoff, S. IgE anti Hepatitis B virus surface antigen antibodies detected in serum from inner city asthmatic and non asthmatic children. Human Immunology 2014, 75, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Norowitz, T.A.; Wong, D.; Kusonruksa, M.; Norowitz, K.B.; Joks, R.; Durkin, H.G.; Bluth, M.H. Long term persistence of IgE anti-influenza virus antibodies in pediatric and adult serum post vaccination with influenza virus vaccine. International journal of medical sciences 2011, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

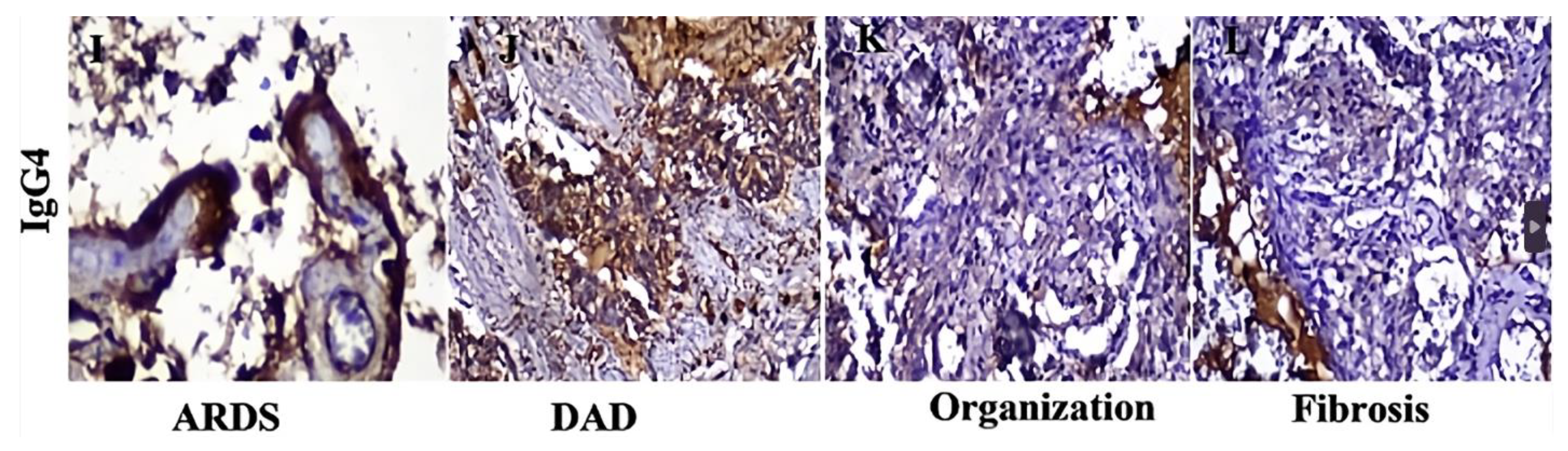

- Della-Torre, E.; Lanzillotta, M.; Strollo, M.; Ramirez, G.A.; Dagna, L.; Tresoldi, M. Serum IgG4 level predicts COVID-19 related mortality. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2021, 93, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moura, A.D.; da Costa, H.H.; Correa, V.A.; de, S. Lima, A.K.; Lindoso, J.A.; De Gaspari, E.; Hong, M.A.; Cunha-Junior, J.P.; Prudencio, C.R. Assessment of avidity related to IgG subclasses in SARS-CoV-2 Brazilian infected patients. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 17642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genova, S.N.; Pencheva, M.M.; Abadjieva, T.I.; Atanasov, N.G. Cellular and immune response in fatal COVID-19 pneumonia. The Pan African Medical Journal 2024, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.F.; James, L.K.; Bahnson, H.T.; Shamji, M.H.; Couto-Francisco, N.C.; Islam, S.; Houghton, S.; Clark, A.T.; Stephens, A.; Turcanu, V. IgG4 inhibits peanut-induced basophil and mast cell activation in peanut-tolerant children sensitized to peanut major allergens. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2015, 135, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin, P.; Bouzoumou, A.; Murrieta, M.; Debbia, M.; Rouger, P.; Leynadier, F.; Levy, D. Purification of human IgG4 subclass with allergen-specific blocking activity. Journal of immunological methods 1993, 165, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Casillas, A.; Redwan, E.M.; Uversky, V.N. Does SARS-CoV-2 induce IgG4 synthesis to evade the immune system? Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balz, K.; Kaushik, A.; Chen, M.; Cemic, F.; Heger, V.; Renz, H.; Nadeau, K.; Skevaki, C. Homologies between SARS-CoV-2 and allergen proteins may direct T cell-mediated heterologous immune responses. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balz, K.; Trassl, L.; Härtel, V.; Nelson, P.P.; Skevaki, C. Virus-induced T cell-mediated heterologous immunity and vaccine development. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusch, E.; Renz, H.; Skevaki, C. Respiratory virus-induced heterologous immunity: Part of the problem or part of the solution? Allergo Journal 2018, 27, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, I.K.; Kaya, M.; Rückert, R.; Bozman, N.; Kaya, V.; Bayram, H.; Yıldırım, M. A bioinformatic analysis: Previous allergen exposure may support anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune response. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2023, 107, 107961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Hasegawa, K.; Ma, B.; Fujiogi, M.; Camargo, C.A.; Liang, L. Association of asthma and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2020, 146, 327–329. e324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevaki, C.; Karsonova, A.; Karaulov, A.; Fomina, D.; Xie, M.; Chinthrajah, S.; Nadeau, K.C.; Renz, H. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 in asthmatics: a complex relationship. Nature Reviews Immunology 2021, 21, 202–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevaki, C.; Karsonova, A.; Karaulov, A.; Xie, M.; Renz, H. Asthma-associated risk for COVID-19 development. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2020, 146, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Pandey, A.K.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, P.; Tripathi, P.K.; Menon, M.B.; Gomes, J.; Vivekanandan, P.; Kundu, B. Uncanny similarity of unique inserts in the 2019-nCoV spike protein to HIV-1 gp120 and Gag. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Worobey, M.; Holmes, E.C. Evolutionary aspects of recombination in RNA viruses. Journal of General Virology 1999, 80, 2535–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Microbiological reviews 1992, 56, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, D.L.; Hahn, B.H.; Sharp, P.M. Recombination in AIDS viruses. Journal of molecular evolution 1995, 40, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Casillas, A.; Redwan, E.M.; Uversky, V.N. SARS-CoV-2: a master of immune evasion. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, K.; Hernandez, N.; Mughal, F.; Tomaszewski, T.; Caetano-Anollés, G. The seasonal behaviour of COVID-19 and its galectin-like culprit of the viral spike. In Methods in Microbiology; Elsevier: 2022; Volume 50, pp. 27-81.

- Hirani, N.; MacKinnon, A.C.; Nicol, L.; Ford, P.; Schambye, H.; Pedersen, A.; Nilsson, U.J.; Leffler, H.; Sethi, T.; Tantawi, S. Target inhibition of galectin-3 by inhaled TD139 in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. European Respiratory Journal 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambouskova, M.; Polakovicova, I.; Halova, I.; Goel, G.; Draberova, L.; Bugajev, V.; Doan, A.; Utekal, P.; Gardet, A.; Xavier, R.J. New regulatory roles of galectin-3 in high-affinity IgE receptor signaling. Molecular and cellular biology 2016, 36, 1366–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsilioni, I.; Theoharides, T.C. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein stimulates secretion of chymase, tryptase, and IL-1β from human mast cells, augmented by IL-33. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perugino, C.A.; AlSalem, S.B.; Mattoo, H.; Della-Torre, E.; Mahajan, V.; Ganesh, G.; Allard-Chamard, H.; Wallace, Z.; Montesi, S.B.; Kreuzer, J. Identification of galectin-3 as an autoantigen in patients with IgG4-related disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2019, 143, 736–745. e736. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, R.V.; Culver, E.L. IgG4 autoantibodies and autoantigens in the context of IgG4-autoimmune disease and IgG4-related disease. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15, 1272084. [Google Scholar]

- Raszek, M.; Cowley, D.; Redwan, E.M.; Uversky, V.N.; Rubio-Casillas, A. Exploring the possible link between the spike protein immunoglobulin G4 antibodies and cancer progression. Exploration of immunology 2024, 4, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Umetsu, D.T.; DeKruyff, R.H. TH1 and TH2 CD4+ cells in human allergic diseases. Journal of allergy and Clinical Immunology 1997, 100, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Y. The changes in the T helper 1 (Th1) and T helper 2 (Th2) cytokine balance during HIV-1 infection are indicative of an allergic response to viral proteins that may be reversed by Th2 cytokine inhibitors and immune response modifiers–a review and hypothesis. Virus genes 2004, 28, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, Y. HIV-1 gp41 heptad repeat 2 (HR2) possesses an amino acid domain that resembles the allergen domain in Aspergillus fumigatus Asp f1 protein: review, hypothesis and implications. Virus Genes 2007, 34, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romagnani, S.; Del Prete, G.; Manetti, R.; Ravina, A.; Annunziato, F.; De Carli, M.; Mazzetti, M.; Piccinni, M.-P.; D'Elios, M.M.; Parronchi, P. Role of TH1/TH2 cytokines in HIV infection. Immunological reviews 1994, 140, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.H.; Goeddel, D.V. Tumour necrosis factors α and β inhibit virus replication and synergize with interferons. Nature 1986, 323, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewski, T.F.; Fitch, F.W. Anti-proliferative effect of IFN-gamma in immune regulation. I. IFN-gamma inhibits the proliferation of Th2 but not Th1 murine helper T lymphocyte clones. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 1988, 140, 4245–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T.R.; Moore, K.W. The role of IL-10 in crossregulation of TH1 and TH2 responses. Immunology today 1991, 12, A49–A53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, Y. HIV-1 induced AIDS is an allergy and the allergen is the Shed gp120–a review, hypothesis, and implications. Virus Genes 2004, 28, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, L.; Da Silva, J. Relationship between atopy, allergic diseases and total serum IgE levels among HIV-infected children. European annals of allergy and clinical immunology 2013, 45, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, M.A.; Bajwa, G.; George, T.A.; Dong, C.C.; Dougherty, I.I.; Jiang, N.; Gan, V.N.; Gruchalla, R.S. Counterregulation between the FcεRI pathway and antiviral responses in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. The Journal of Immunology 2010, 184, 5999–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, V.; Sykes, A.; Zhu, J.; Chan, B.; Macintyre, J.; Regamey, N.; Kieninger, E.; Gupta, A.; Shoemark, A.; Bossley, C. Increased nuclear suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 in asthmatic bronchial epithelium suppresses rhinovirus induction of innate interferons. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2015, 136, 177–188. e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P.; Werder, R.B.; Simpson, J.; Loh, Z.; Zhang, V.; Haque, A.; Spann, K.; Sly, P.D.; Mazzone, S.B.; Upham, J.W. Aeroallergen-induced IL-33 predisposes to respiratory virus–induced asthma by dampening antiviral immunity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2016, 138, 1326–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrani, S.R.; Montville, D.J.; Pratt, A.S.; Sahu, S.; DeVries, M.K.; Rajamanickam, V.; Gangnon, R.E.; Gill, M.A.; Gern, J.E.; Lemanske Jr, R.F. Innate immune responses to rhinovirus are reduced by the high-affinity IgE receptor in allergic asthmatic children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2012, 130, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, A.L.; Pomeranz, E.S.; Gelber, L.E.; Price, G.W.; Farris, H.; Hayden, F.G.; Platts-Mills, T.A.; Heymann, P.W. Risk factors for acute wheezing in infants and children: viruses, passive smoke, and IgE antibodies to inhalant allergens. Pediatrics 1993, 92, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teach, S.J.; Gergen, P.J.; Szefler, S.J.; Mitchell, H.E.; Calatroni, A.; Wildfire, J.; Bloomberg, G.R.; Kercsmar, C.M.; Liu, A.H.; Makhija, M.M. Seasonal risk factors for asthma exacerbations among inner-city children. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2015, 135, 1465–1473. e1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Quiros, M.; Avila, L.; Platts-Mills, T.A.; Hunt, J.F.; Erdman, D.D.; Carper, H.; Murphy, D.D.; Odio, S.; James, H.R.; Patrie, J.T. High titers of IgE antibody to dust mite allergen and risk for wheezing among asthmatic children infected with rhinovirus. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2012, 129, 1499–1505. e1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiecki, M.; Colonna, M. The multifaceted biology of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nature Reviews Immunology 2015, 15, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bencze, D.; Fekete, T.; Pázmándi, K. Type I interferon production of plasmacytoid dendritic cells under control. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, M.A.; Liu, A.H.; Calatroni, A.; Krouse, R.Z.; Shao, B.; Schiltz, A.; Gern, J.E.; Togias, A.; Busse, W.W. Enhanced plasmacytoid dendritic cell antiviral responses after omalizumab. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2018, 141, 1735–1743. e1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teach, S.J.; Gill, M.A.; Togias, A.; Sorkness, C.A.; Arbes Jr, S.J.; Calatroni, A.; Wildfire, J.J.; Gergen, P.J.; Cohen, R.T.; Pongracic, J.A. Preseasonal treatment with either omalizumab or an inhaled corticosteroid boost to prevent fall asthma exacerbations. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2015, 136, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, A.; Busse, W.W.; Calatroni, A.; Togias, A.G.; Grindle, K.G.; Bochkov, Y.A.; Gruchalla, R.S.; Kattan, M.; Kercsmar, C.M.; Khurana Hershey, G. Effects of omalizumab on rhinovirus infections, illnesses, and exacerbations of asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2017, 196, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Abdullahi, A.; Ferreira, I.A.; Goonawardane, N.; Saito, A.; Kimura, I.; Yamasoba, D.; Gerber, P.P.; Fatihi, S.; Rathore, S. Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts infectivity and fusogenicity. Nature 2022, 603, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, T.P.; Brown, J.C.; Zhou, J.; Thakur, N.; Sukhova, K.; Newman, J.; Kugathasan, R.; Yan, A.W.; Furnon, W.; De Lorenzo, G. The altered entry pathway and antigenic distance of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant map to separate domains of spike protein. Biorxiv 2022, 2021.2012. 2031.474653.

- McMahan, K.; Giffin, V.; Tostanoski, L.H.; Chung, B.; Siamatu, M.; Suthar, M.S.; Halfmann, P.; Kawaoka, Y.; Piedra-Mora, C.; Jain, N. Reduced pathogenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in hamsters. Med 2022, 3, 262–268. e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, B.J.; Grove, J.; MacLean, O.A.; Wilkie, C.; De Lorenzo, G.; Furnon, W.; Cantoni, D.; Scott, S.; Logan, N.; Ashraf, S. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron is an immune escape variant with an altered cell entry pathway. Nature microbiology 2022, 7, 1161–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariën, K.K.; Vanham, G.; Arts, E.J. Is HIV-1 evolving to a less virulent form in humans? Nature Reviews Microbiology 2007, 5, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobben, M.; Bakker, M.; Schriek, A.I.; Levels, L.J.; Umotoy, J.C.; Tejjani, K.; van Breemen, M.J.; Lin, R.N.; de Taeye, S.W.; Ozorowski, G. Polyfunctionality and breadth of HIV-1 antibodies are associated with delayed disease progression. PLoS pathogens 2024, 20, e1012739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.W.; Ghebremichael, M.; Robinson, H.; Brown, E.; Choi, I.; Lane, S.; Dugast, A.-S.; Schoen, M.K.; Rolland, M.; Suscovich, T.J. Polyfunctional Fc-effector profiles mediated by IgG subclass selection distinguish RV144 and VAX003 vaccines. Science translational medicine 2014, 6, 228ra238–228ra238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnasuta, C.; Akapirat, S.; Madnote, S.; Savadsuk, H.; Puangkaew, J.; Rittiroongrad, S.; Rerks-Ngarm, S.; Nitayaphan, S.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Kaewkungwal, J. Comparison of antibody responses induced by RV144, VAX003, and VAX004 vaccination regimens. AIDS research and human retroviruses 2017, 33, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, N.L.; Liao, H.-X.; Fong, Y.; DeCamp, A.; Vandergrift, N.A.; Williams, W.T.; Alam, S.M.; Ferrari, G.; Yang, Z.-y.; Seaton, K.E. Vaccine-induced Env V1-V2 IgG3 correlates with lower HIV-1 infection risk and declines soon after vaccination. Science translational medicine 2014, 6, 228ra239–228ra239. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, G.N.; Locke, E.R.; O’Hare, A.M.; Bohnert, A.S.; Boyko, E.J.; Hynes, D.M.; Berry, K. COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness against infection or death in a national US health care system: a target trial emulation study. Annals of Internal Medicine 2022, 175, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, E.; Morioka, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Fukushima, M. Behavioral and Health Outcomes of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case-Control Study in Japanese Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eythorsson, E.; Runolfsdottir, H.L.; Ingvarsson, R.F.; Sigurdsson, M.I.; Palsson, R. Rate of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection during an omicron wave in Iceland. JAMA network open 2022, 5, e2225320–e2225320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemaitelly, H.; Tang, P.; Hasan, M.R.; AlMukdad, S.; Yassine, H.M.; Benslimane, F.M.; Al Khatib, H.A.; Coyle, P.; Ayoub, H.H.; Al Kanaani, Z. Waning of BNT162b2 vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 385, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, N.K.; Burke, P.C.; Nowacki, A.S.; Gordon, S.M. Risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among those up-to-date and not up-to-date on COVID-19 vaccination by US CDC criteria. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0293449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, L.R.; Ruffin, J.; Wiegand, R.; Grant, L.; Babu, T.M.; Briggs-Hagen, M.; Burgess, J.L.; Caban-Martinez, A.J.; Chu, H.Y.; Ellingson, K.D. Protection from covid-19 vaccination and prior sars-cov-2 infection among children aged 6 months–4 years, united states, september 2022–april 2023. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2025, 14, piae121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, C.; Manni, S.; Wolff, S.; Barnes, T.; Mukherjee, S.; Vogel, T.; Hoenig, L.; Vogel, P.; Hahn, A.; Gerlach, M. IgG3 and IgM identified as key to SARS-CoV-2 neutralization in convalescent plasma pools. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitcombe, A.L.; McGregor, R.; Craigie, A.; James, A.; Charlewood, R.; Lorenz, N.; Dickson, J.M.; Sheen, C.R.; Koch, B.; Fox-Lewis, S. Comprehensive analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics in New Zealand. Clinical & translational immunology 2021, 10, e1261. [Google Scholar]

- Gazit, S.; Shlezinger, R.; Perez, G.; Lotan, R.; Peretz, A.; Ben-Tov, A.; Cohen, D.; Muhsen, K.; Chodick, G.; Patalon, T. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 natural immunity to vaccine-induced immunity: reinfections versus breakthrough infections. MedRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Redman, M.; King, A.; Watson, C.; King, D. What is CRISPR/Cas9? Archives of Disease in Childhood-Education and Practice 2016, 101, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobaño, C.; Quelhas, D.; Quintó, L.; Puyol, L.; Serra-Casas, E.; Mayor, A.; Nhampossa, T.; Macete, E.; Aide, P.; Mandomando, I. Age-dependent IgG subclass responses to Plasmodium falciparum EBA-175 are differentially associated with incidence of malaria in Mozambican children. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2012, 19, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucan, C.; Traoré, Y.; Tall, F.o.; Nacro, B.; Traoré-Leroux, T.r.s.; Fumoux, F.; Rihet, P. High immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) and low IgG4 levels are associated with human resistance to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infection and immunity 2000, 68, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groux, H.; Gysin, J. Opsonization as an effector mechanism in human protection against asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum: functional role of IgG subclasses. Research in immunology 1990, 141, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thau, L.; Asuka, E.; Mahajan, K. Physiology, opsonization. StatPearls [Internet] 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).