Submitted:

11 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, Virus and Sera

2.2. Hamster Study Design

2.3. Assessment of Functional Activity of Anti-N Antibodies

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

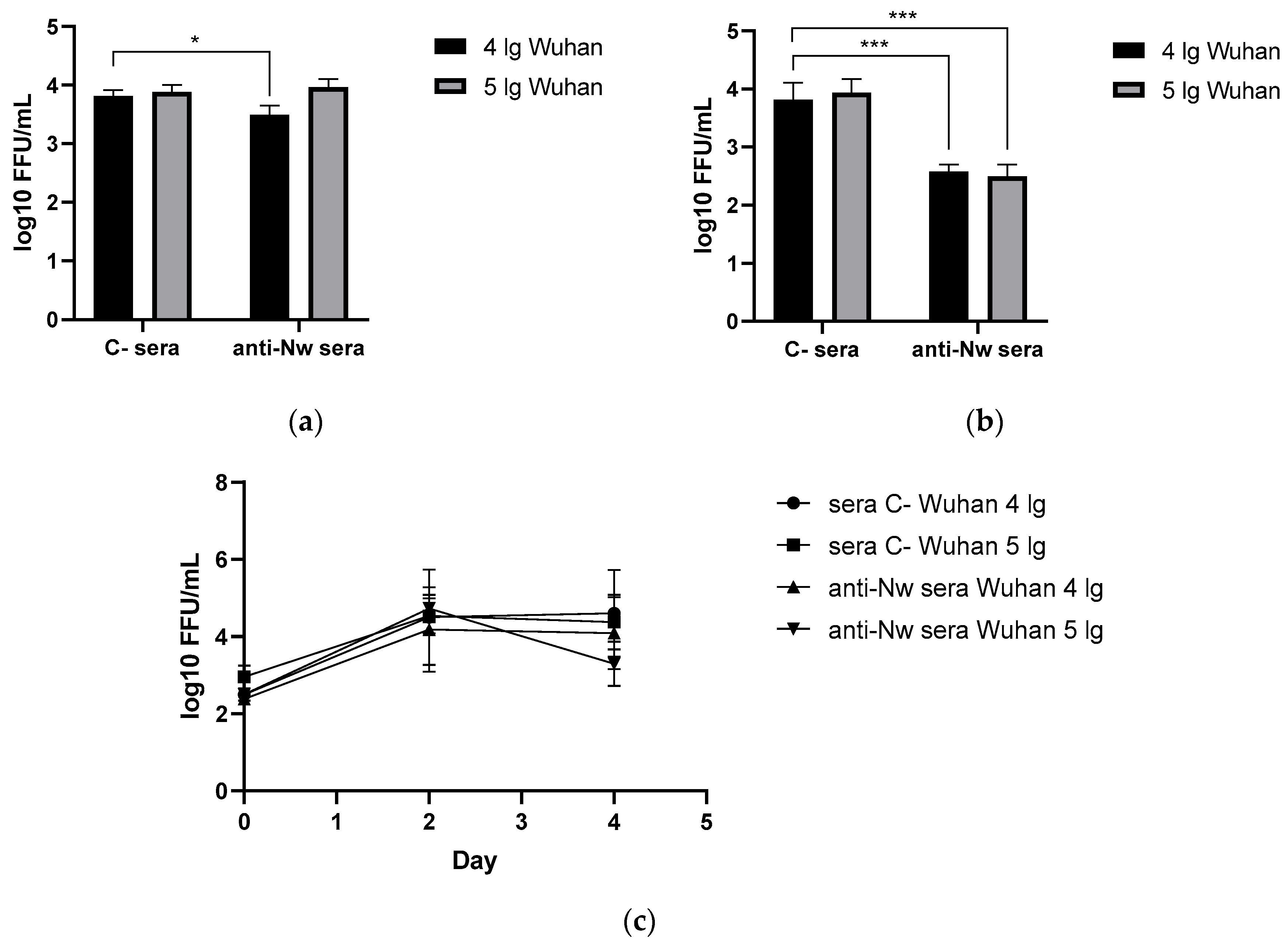

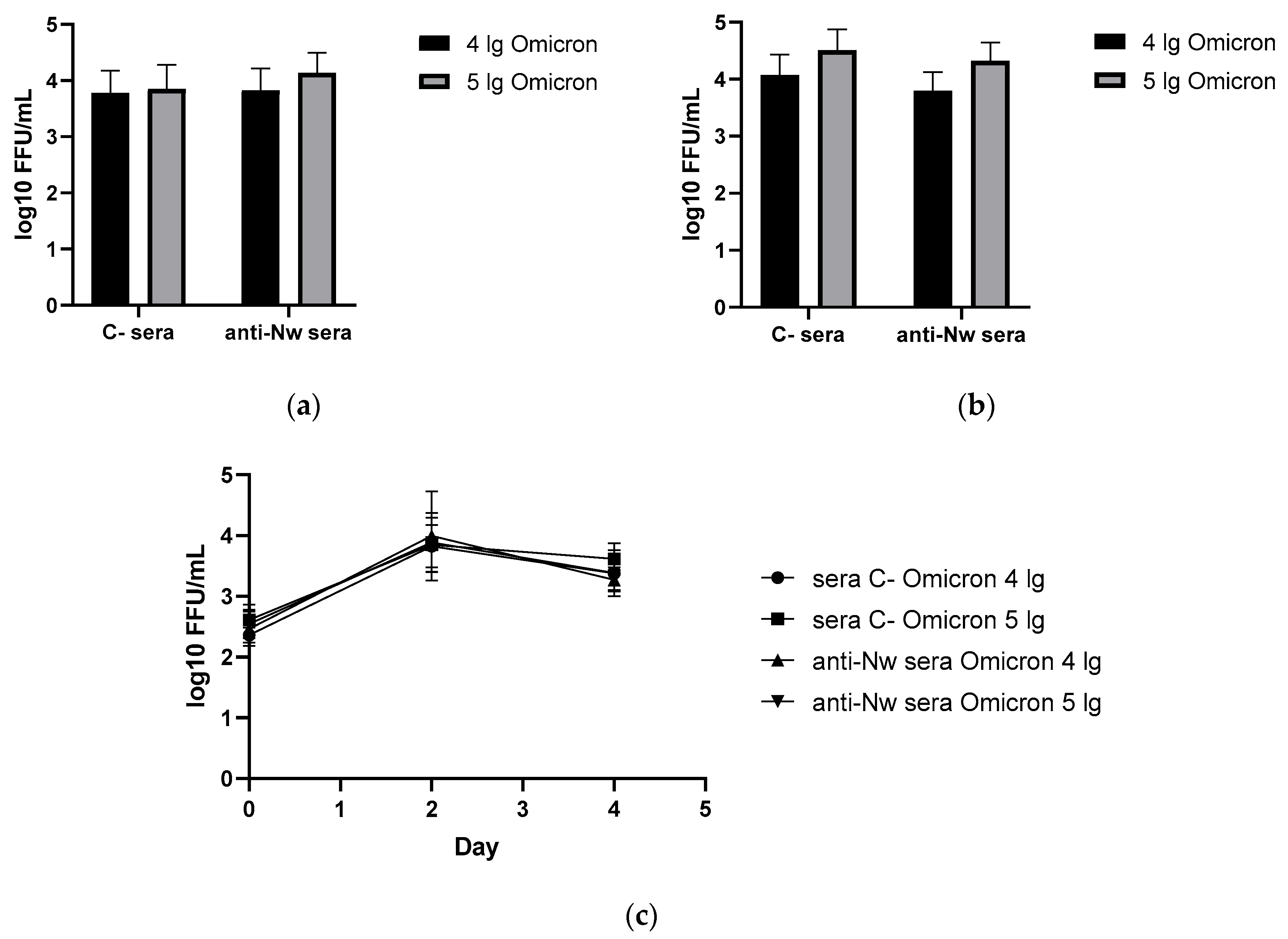

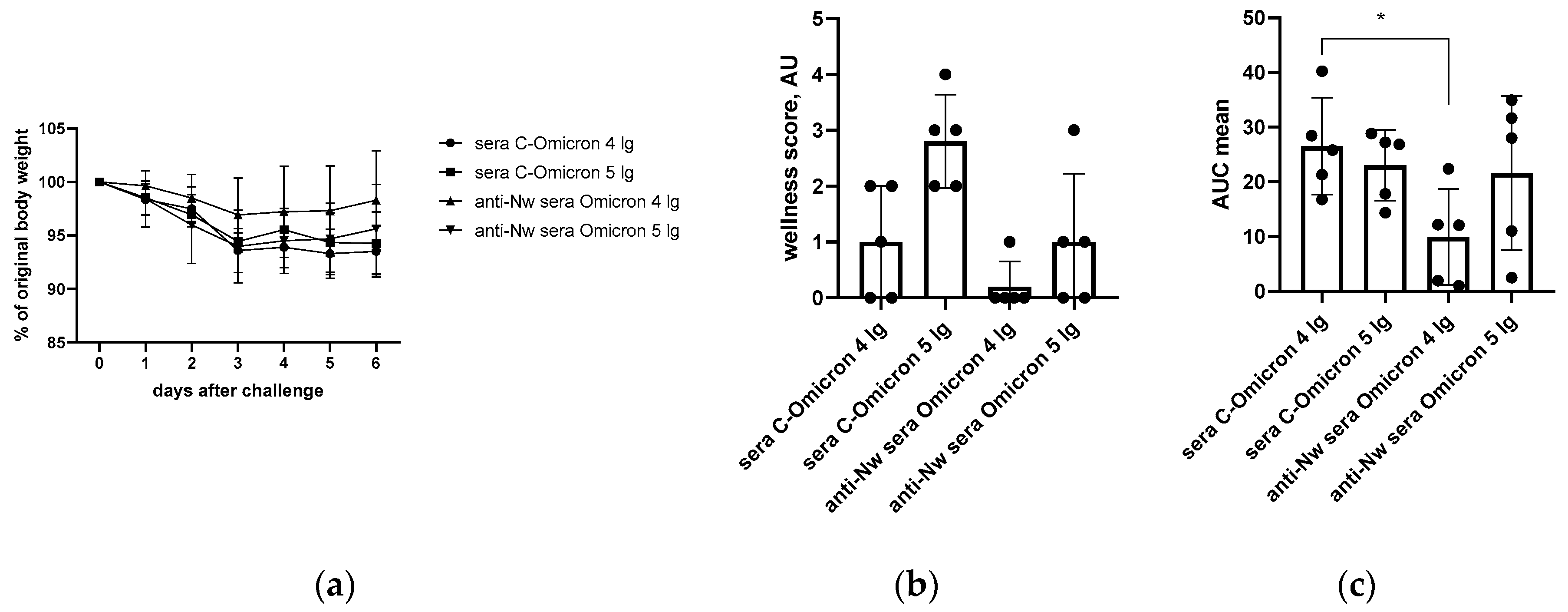

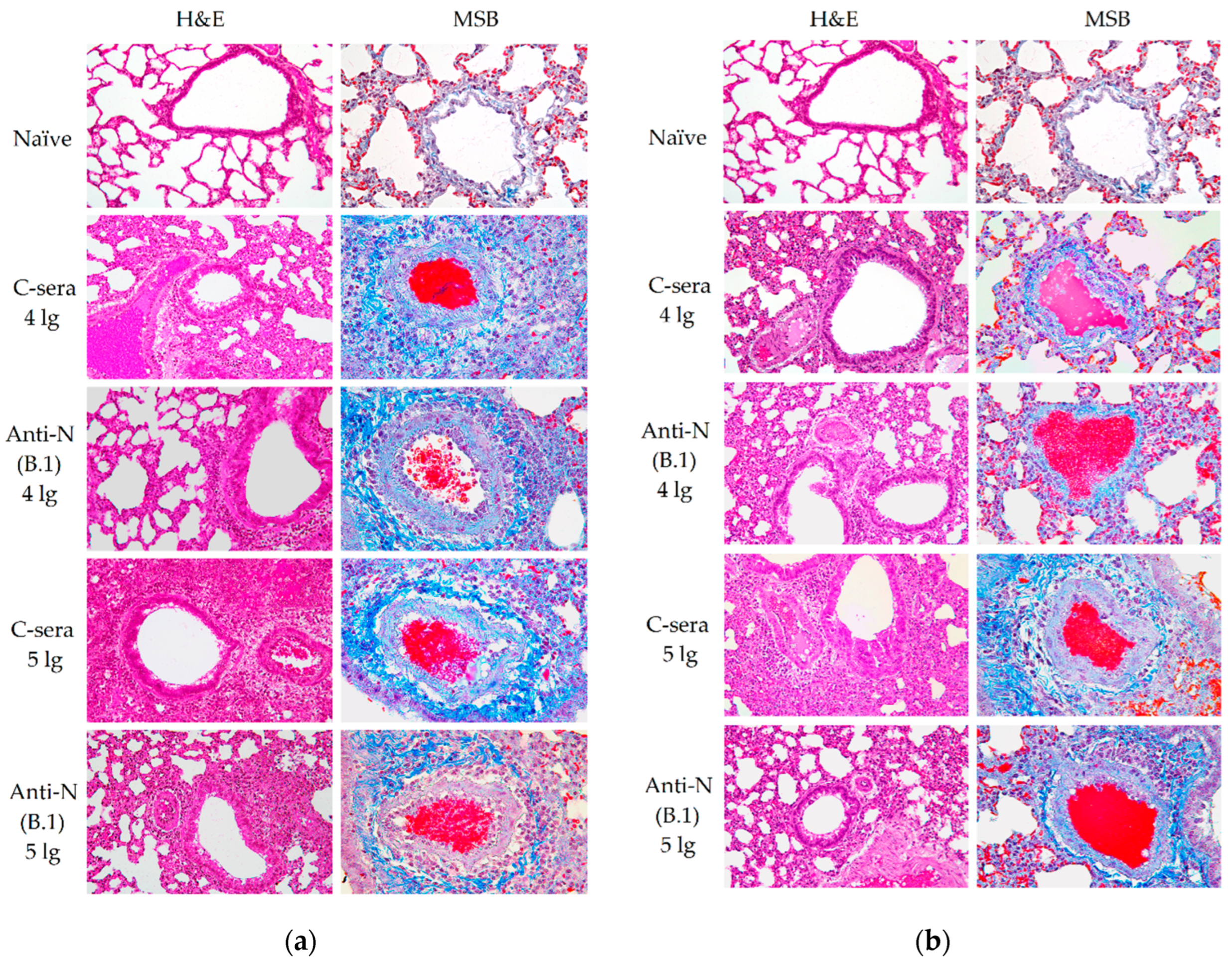

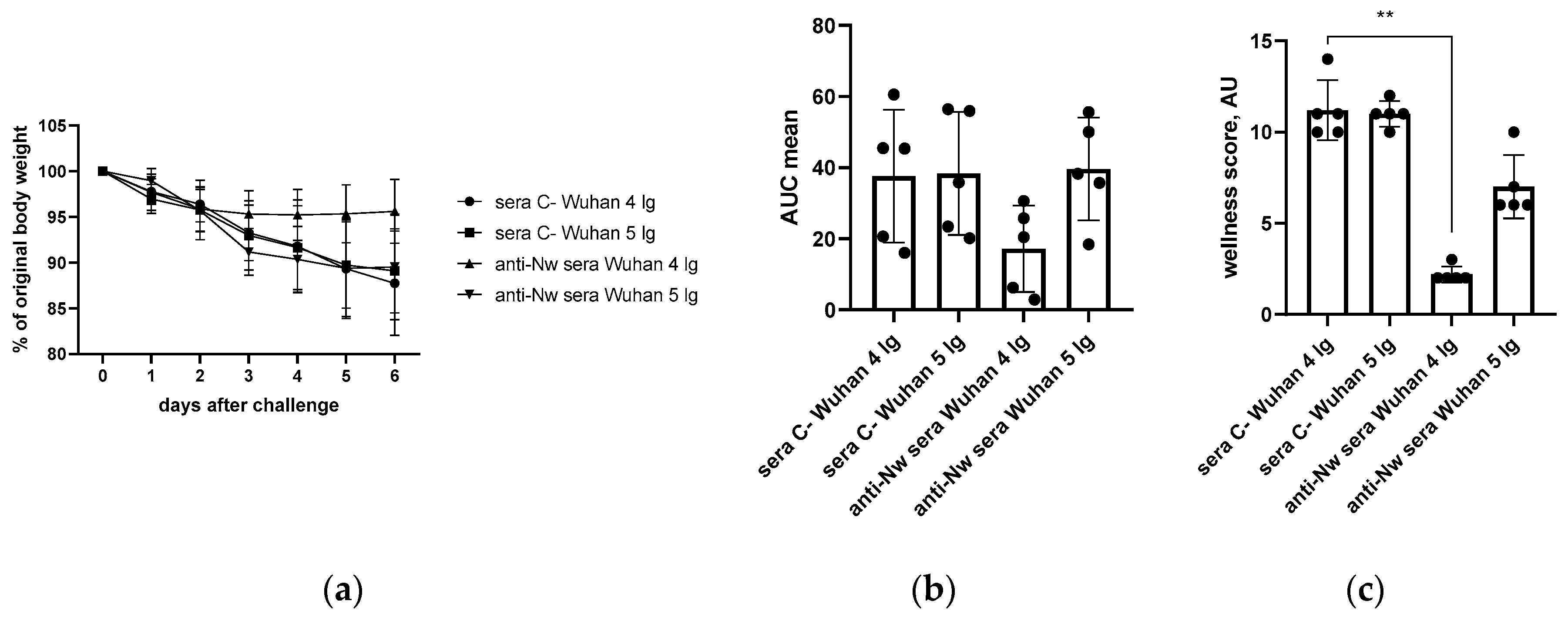

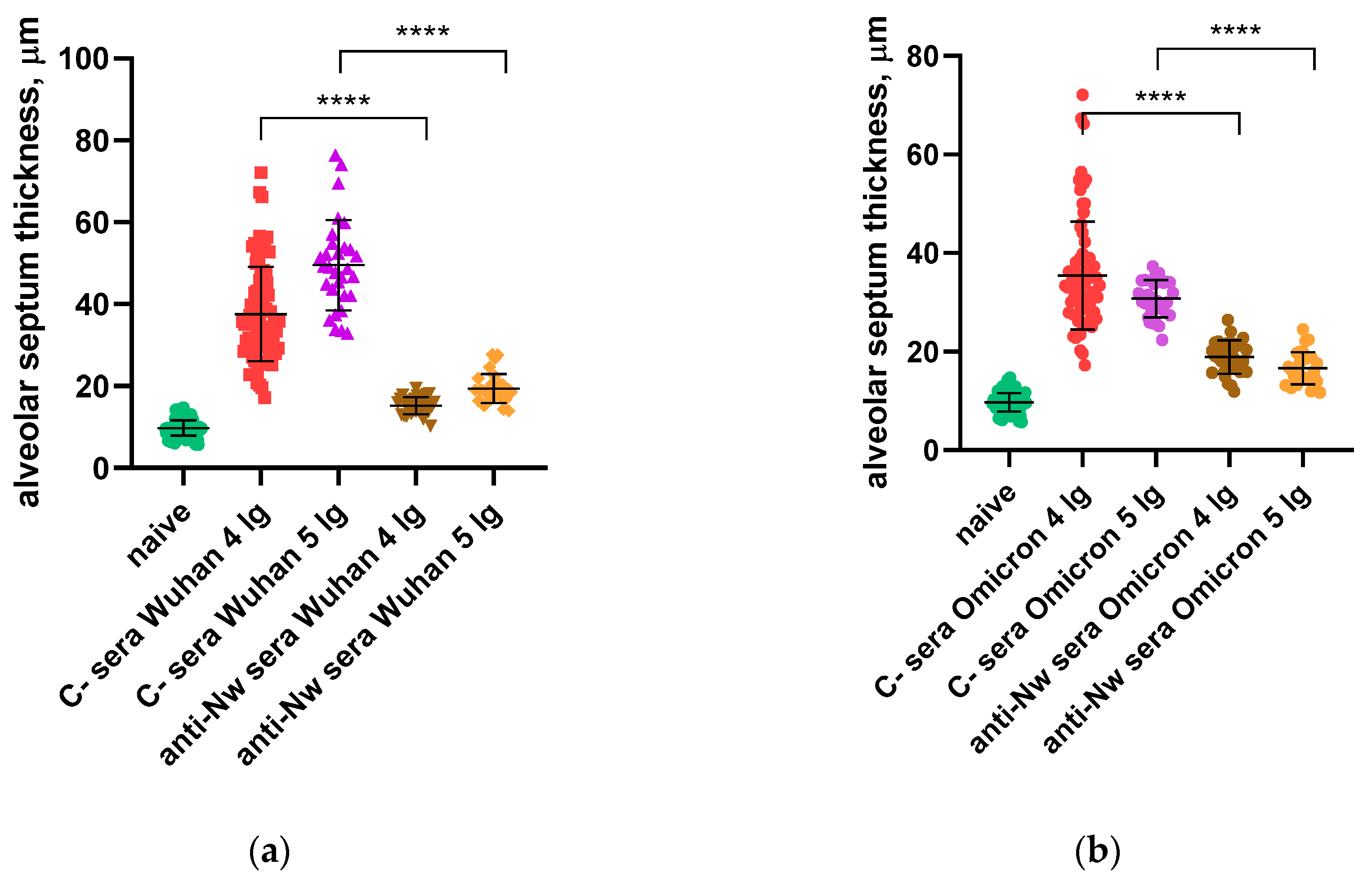

3.1. Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 Infection

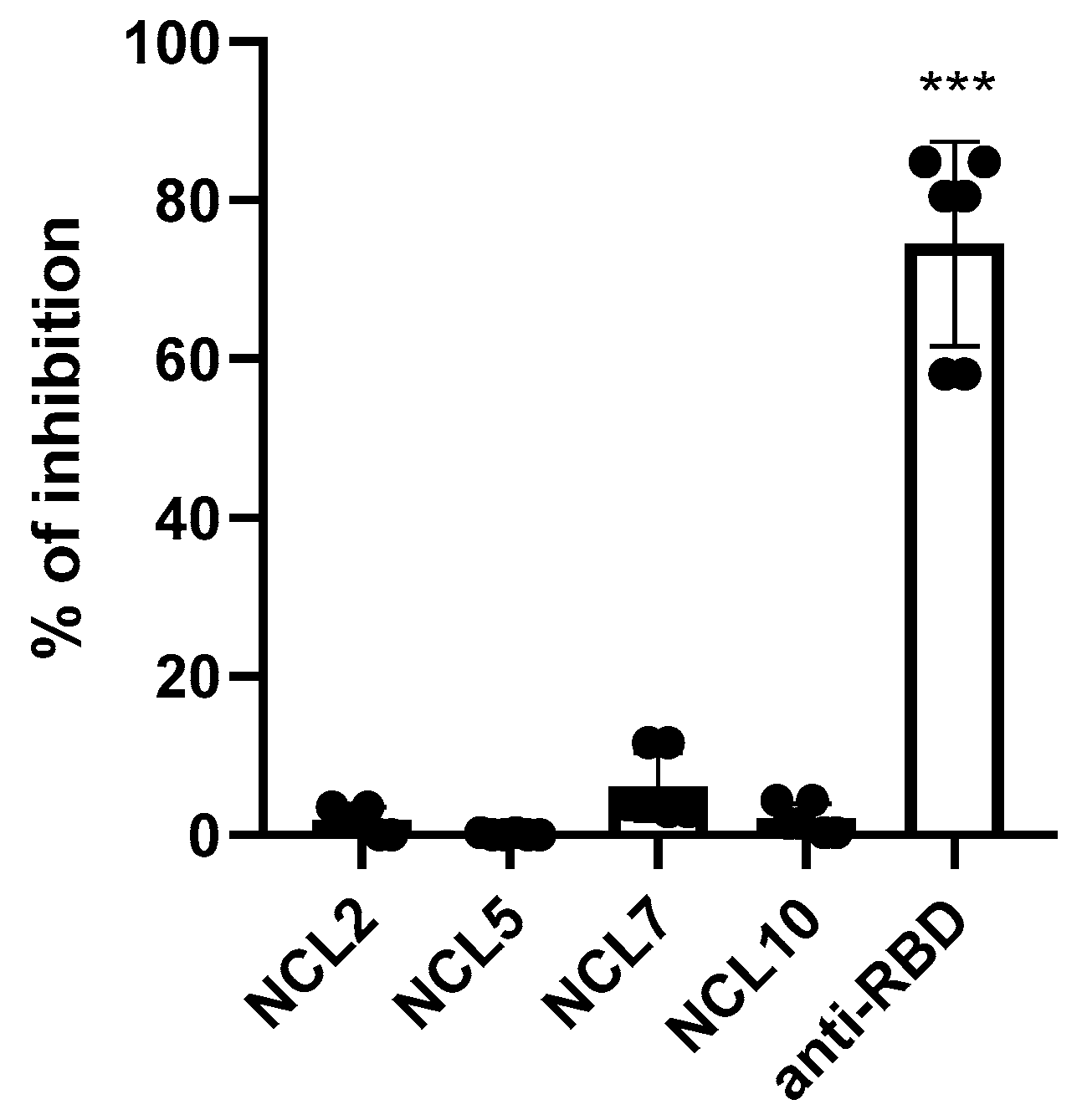

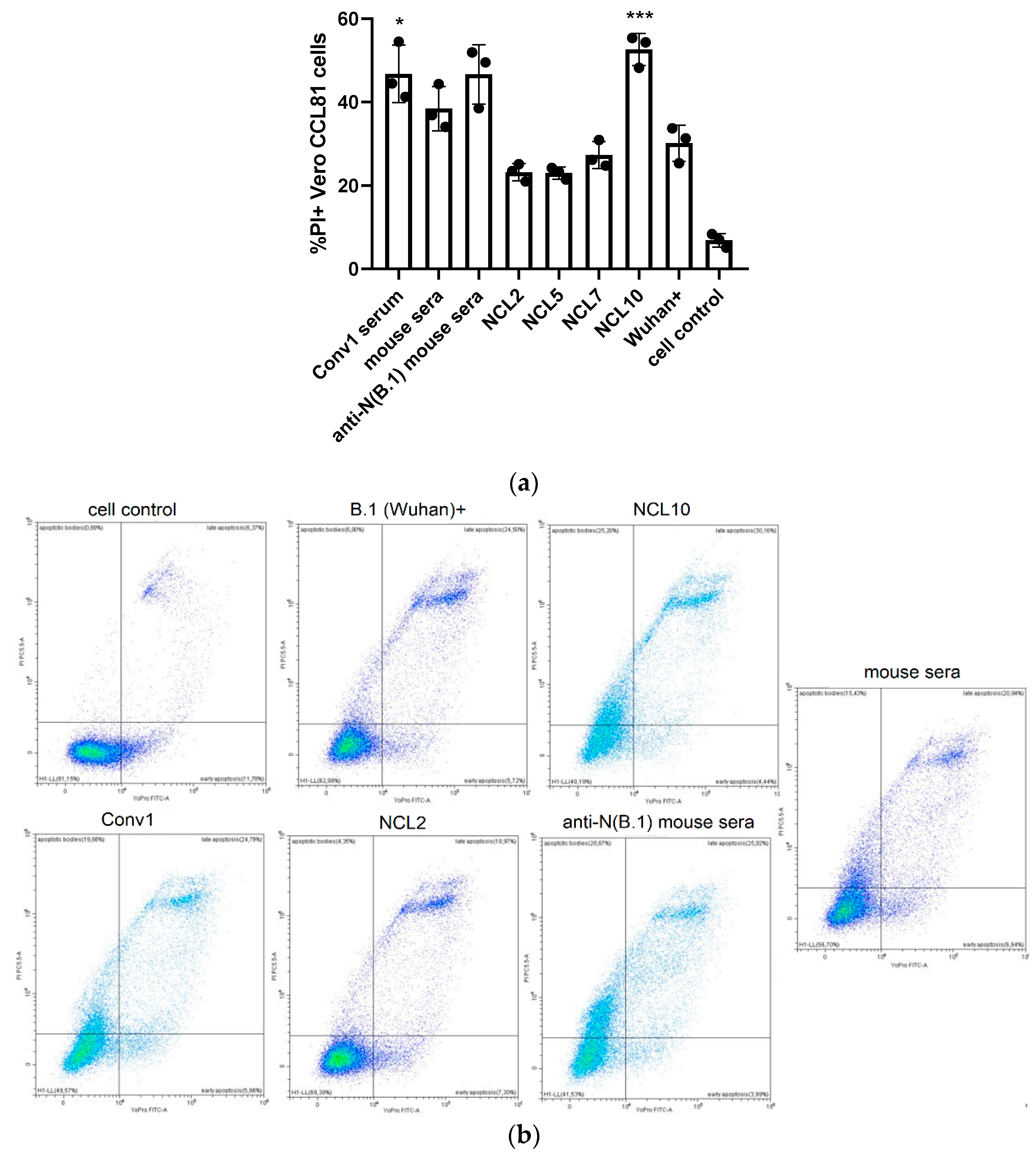

3.2. Functional Activity of the N(B.1)-Specific Antibodies

3.2.1. Complement Dependent Cytotoxicity (CDC)

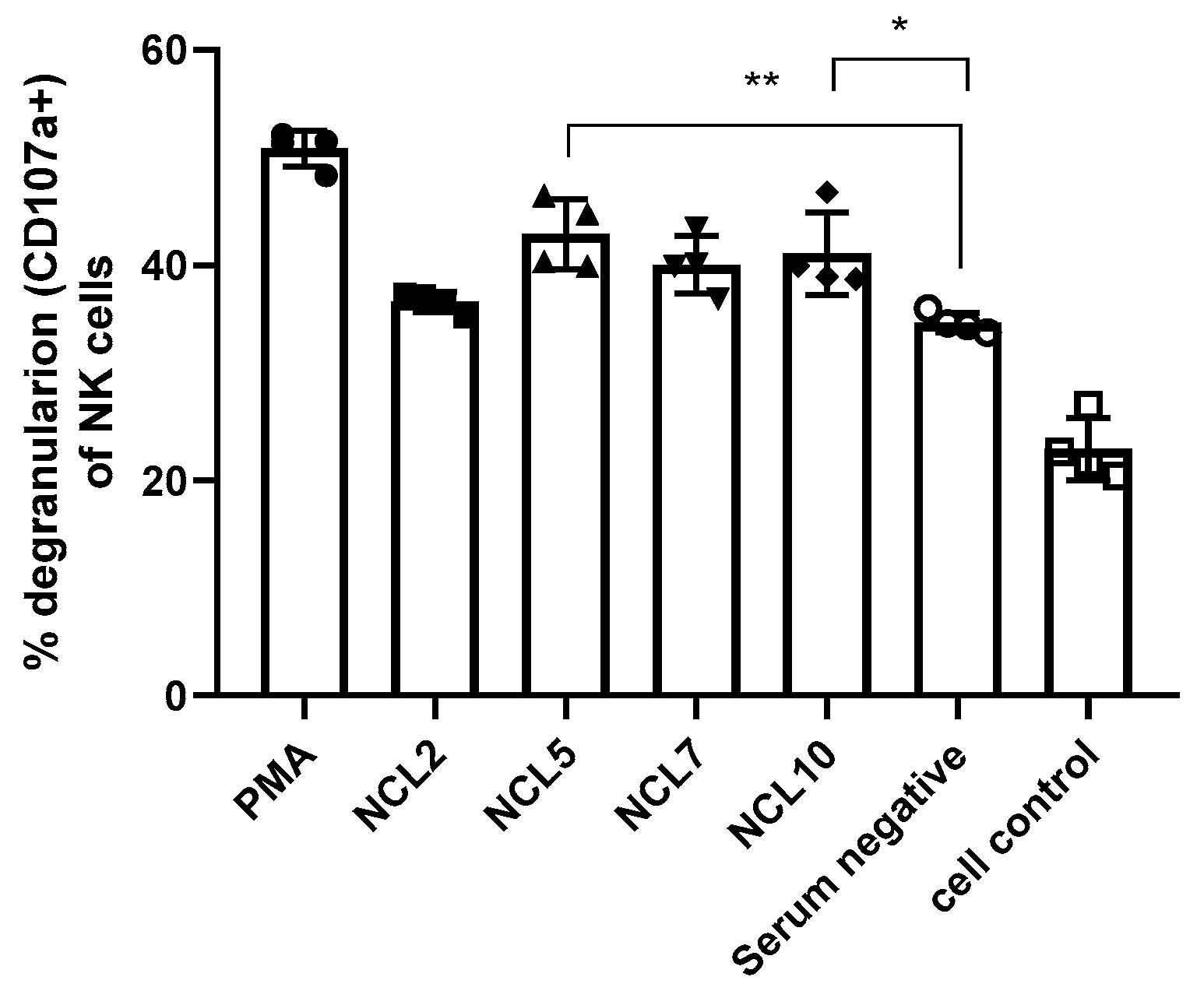

3.2.2. Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Senevirathne, T.H.; Wekking, D.; Swain, J.W.R.; Solinas, C.; De Silva, P. COVID-19: From emerging variants to vaccination. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2024, 76, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oronsky, B.; Larson, C.; Caroen, S.; Hedjran, F.; Sanchez, A.; Prokopenko, E.; Reid, T. Nucleocapsid as a next-generation COVID-19 vaccine candidate. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases 2022, 122, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, N.K.; Mazumdar, K.; Gordy, J.T. The Nucleocapsid Protein of SARS-CoV-2: a Target for Vaccine Development. Journal of virology 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Muñoz, A.D.; Yewdell, J.W. Cell surface RNA virus nucleocapsid proteins: a viral strategy for immunosuppression? npj Viruses 2024, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rak, A.; Donina, S.; Zabrodskaya, Y.; Rudenko, L.; Isakova-Sivak, I. Cross-Reactivity of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid-Binding Antibodies and Its Implication for COVID-19 Serology Tests. Viruses 2022, 14, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Sidney, J.; Vita, R.; Peters, B.; Crotty, S.; Weiskopf, D.; Sette, A. SARS-CoV-2 human T cell epitopes: Adaptive immune response against COVID-19. Cell host & microbe 2021, 29, 1076–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, A.; Sidney, J.; Crotty, S. T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2. Annual review of immunology 2023, 41, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Ramirez, S.I.; Mateus, J.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Rawlings, S.A.; Sutherland, A.; Premkumar, L.; Jadi, R.S.; et al. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell 2020, 181, 1489–1501.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajnberg, A.; Amanat, F.; Firpo, A.; Altman, D.R.; Bailey, M.J.; Mansour, M.; McMahon, M.; Meade, P.; Mendu, D.R.; Muellers, K.; et al. Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months. Science 2020, 370, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movsisyan, M.; Truzyan, N.; Kasparova, I.; Chopikyan, A.; Sawaqed, R.; Bedross, A.; Sukiasyan, M.; Dilbaryan, K.; Shariff, S.; Kantawala, B.; et al. Tracking the evolution of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and long-term humoral immunity within 2 years after COVID-19 infection. Scientific reports 2024, 14, 13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerber, N.; Priller, A.; Yazici, S.; Bauer, T.; Cheng, C.C.; Mijocevic, H.; Wintersteller, H.; Jeske, S.; Vogel, E.; Feuerherd, M.; et al. Dynamics of spike-and nucleocapsid specific immunity during long-term follow-up and vaccination of SARS-CoV-2 convalescents. Nature communications 2022, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yang, M.; He, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.Q.; Hong, Z.; Liu, J.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Q.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 antibody curbs viral nucleocapsid protein-induced complement hyperactivation. Nature communications 2021, 12, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caddy, S.L.; Vaysburd, M.; Papa, G.; Wing, M.; O'Connell, K.; Stoycheva, D.; Foss, S.; Terje Andersen, J.; Oxenius, A.; James, L.C. Viral nucleoprotein antibodies activate TRIM21 and induce T cell immunity. The EMBO journal 2021, 40, e106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, H.O.; Saltoglu, N.; Can, G.; Balkan, II; Budak, B.; Ozbey, D.; Caglar, B.; Karaali, R.; Mete, B.; Tuyji Tok, Y.; et al. Inactive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine generates high antibody responses in healthcare workers with and without prior infection. Vaccine 2022, 40, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Ning, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Shi, L.; He, T.; Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Zhai, A.; Wu, C. The BBIBP-CorV inactivated COVID-19 vaccine induces robust and persistent humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid, besides spike protein in healthy adults. Frontiers in microbiology 2022, 13, 1008420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Zou, J.; Muruato, A.E.; Periasamy, S.; Kurhade, C.; Plante, J.A.; Bopp, N.E.; et al. A live-attenuated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate with accessory protein deletions. Nature communications 2022, 13, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyushkina, D.; Shokina, V.; Tikhonova, P.; Manuvera, V.; Shirokov, D.; Kharlampieva, D.; Lazarev, V.; Varizhuk, A.; Vedekhina, T.; Pavlenko, A.; et al. Autoimmune Effect of Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 Nucleoprotein. Viruses 2022, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyushenko, V.; Isakova-Sivak, I.; Kudryavtsev, I.; Goshina, A.; Chistyakova, A.; Stepanova, E.; Prokopenko, P.; Sychev, I.; Rudenko, L. Detection of IFNgamma-Secreting CD4(+) and CD8(+) Memory T Cells in COVID-19 Convalescents after Stimulation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells with Live SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2021, 13, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonimous. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European parliament and of the council of September 22, 2010, on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32010L0063.

- Rak, A.; Matyushenko, V.; Prokopenko, P.; Kostromitina, A.; Polyakov, D.; Sokolov, A.; Rudenko, L.; Isakova-Sivak, I. A novel immunofluorescent test system for SARS-CoV-2 detection in infected cells. PloS one 2024, 19, e0304534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, K.S.; Mezhenskaya, D.А.; Sivak, K.V.; Rudenko, L.G.; Isakova-Sivak, I.N. Comparative study of the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 B.1 AND B.1.617.2 lineages for syrian hamsters. Medical academic journal 2022, 22, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, B.J.; Roman, J.A.; Luke, T.C.; Nagabhushana, N.; Raviprakash, K.; Williams, M.; Sun, P. Antibody-dependent NK cell degranulation as a marker for assessing antibody-dependent cytotoxicity against pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in human plasma and influenza-vaccinated transchromosomic bovine intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Journal of virological methods 2017, 248, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, M.R.; Price, D.A.; Brenchley, J.M.; Lore, K.; Guenaga, F.J.; Smed-Sorensen, A.; Ambrozak, D.R.; Migueles, S.A.; Connors, M.; Roederer, M.; et al. The functional profile of primary human antiviral CD8+ T cell effector activity is dictated by cognate peptide concentration. Journal of immunology 2004, 172, 6407–6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rak, A.; Gorbunov, N.; Kostevich, V.; Sokolov, A.; Prokopenko, P.; Rudenko, L.; Isakova-Sivak, I. Assessment of Immunogenic and Antigenic Properties of Recombinant Nucleocapsid Proteins of Five SARS-CoV-2 Variants in a Mouse Model. Viruses 2023, 15, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duensing, T.D.; Watson, S.R. Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity Assay. Cold Spring Harbor protocols 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, R.; Roknuzzaman, A.S.M.; Nazmunnahar; Shahriar, M.; Hossain, M.J.; Islam, M.R. The WHO has declared the end of pandemic phase of COVID-19: Way to come back in the normal life. Health science reports 2023, 6, e1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Behera, R.L.; Paital, B. CHAPTER 8 - Socio-economic impact of COVID-19. In COVID-19 in the Environment; Rawtani, D., Hussain, C.M., Khatri, N., Eds.; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 153–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, O.J.; Barnsley, G.; Toor, J.; Hogan, A.B.; Winskill, P.; Ghani, A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2022, 22, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinands, J.M.; Rao, S.; Dixon, B.E.; Mitchell, P.K.; DeSilva, M.B.; Irving, S.A.; Lewis, N.; Natarajan, K.; Stenehjem, E.; Grannis, S.J.; et al. Waning of vaccine effectiveness against moderate and severe covid-19 among adults in the US from the VISION network: test negative, case-control study. Bmj 2022, 379, e072141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobczak, M.; Pawliczak, R. COVID-19 vaccination efficacy in numbers including SARS-CoV-2 variants and age comparison: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Annals of clinical microbiology and antimicrobials 2022, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Role in Viral Structure, Biological Functions, and a Potential Target for Drug or Vaccine Mitigation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubuk, J.; Alston, J.J.; Incicco, J.J.; Singh, S.; Stuchell-Brereton, M.D.; Ward, M.D.; Zimmerman, M.I.; Vithani, N.; Griffith, D.; Wagoner, J.A.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein is dynamic, disordered, and phase separates with RNA. Nature communications 2021, 12, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanaga, K.; Yamanouchi, K.; Fujiwara, K. Protective effect of monoclonal antibodies on lethal mouse hepatitis virus infection in mice. Journal of virology 1986, 59, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.; Class, J.; Palacio, N.; Richner, J.M.; Penaloza MacMaster, P. Combining spike- and nucleocapsid-based vaccines improves distal control of SARS-CoV-2. Cell reports 2021, 36, 109664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, F.Y.; Lidenge, S.J.; Poppe, L.K.; Pena, P.B.; Privatt, S.R.; Bennett, S.J.; Ngowi, J.R.; Mwaiselage, J.; Belshan, M.; Siedlik, J.A.; et al. Presence of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) against SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 plasma. PloS one 2021, 16, e0247640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Lu, Q.; Zeng, H.; Hou, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, F.; et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity response to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2021, 6, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnan, W.; Wrighton, S.; Sundwall, M.; Blackberg, A.; Larsson, O.; Hoglund, U.; Khakzad, H.; Godzwon, M.; Walle, M.; Elder, E.; et al. Spike-Dependent Opsonization Indicates Both Dose-Dependent Inhibition of Phagocytosis and That Non-Neutralizing Antibodies Can Confer Protection to SARS-CoV-2. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 808932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, C.A.; Sabberwal, P.; Williamson, J.C.; Greenwood, E.J.D.; Crozier, T.W.M.; Zelek, W.; Seow, J.; Graham, C.; Huettner, I.; Edgeworth, J.D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 host-shutoff impacts innate NK cell functions, but antibody-dependent NK activity is strongly activated through non-spike antibodies. eLife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieke, G.J.; van Bremen, K.; Bischoff, J.; ToVinh, M.; Monin, M.B.; Schlabe, S.; Raabe, J.; Kaiser, K.M.; Finnemann, C.; Odainic, A.; et al. Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity Against SARS-CoV-2 After Natural Infection Is More Potent Than After Vaccination. The Journal of infectious diseases 2022, 225, 1688–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez, J.M.; Romero, C.; Cruz, M.; Vandeberg, P.; Merritt, W.K.; Pradenas, E.; Trinite, B.; Blanco, J.; Clotet, B.; Willis, T.; et al. Anti-Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Hyperimmune Immunoglobulin Demonstrates Potent Neutralization and Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity and Phagocytosis Through N and S Proteins. The Journal of infectious diseases 2022, 225, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, K.; Riecken, K.; Jung, J.M.; Hildebrandt, H.; Menzel, S.; Bunders, M.J.; Fehse, B.; Koch-Nolte, F.; Heinrich, F.; Peine, S.; et al. Natural killer cell-mediated ADCC in SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals and vaccine recipients. European journal of immunology 2022, 52, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamerton, R.E.; Marcial-Juarez, E.; Faustini, S.E.; Perez-Toledo, M.; Goodall, M.; Jossi, S.E.; Newby, M.L.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Veenith, T.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike- and Nucleoprotein-Specific Antibodies Induced After Vaccination or Infection Promote Classical Complement Activation. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 838780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojdani, A.; Vojdani, E.; Kharrazian, D. Reaction of Human Monoclonal Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 Proteins With Tissue Antigens: Implications for Autoimmune Diseases. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 617089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).