Introduction

Dental implants restore function and aesthetics in edentulous patients, with prosthodontic components like abutments and crowns ensuring full rehabilitation. [

1] Their success is largely due to osseointegration—the direct bonding of bone to titanium. [

2]

Two key interfaces exist in implant dentistry: the bone-implant interface (osseointegration), which is well-studied, [

3] and the peri-implant soft tissue interface (soft tissue seal or mucointegration), which remains less understood. [

4,

5] This soft tissue barrier is crucial for preventing peri-implant disease and ensuring long-term stability. When compromised, bacterial infiltration can lead to peri-implant mucositis or peri-implantitis, which, if untreated, causes progressive bone loss and implant failure. [

6,

11,

12,

13]

Unlike periodontal bone loss, peri-implant bone loss may result from insufficient soft tissue thickness rather than bacterial factors. Linkevicius et al. found that when soft tissue thickness (STT) at the alveolar crest is ≤2 mm, bone resorption occurs as the body establishes biologic width. [

14] This underscores the need for adequate soft tissue dimensions to maintain peri-implant health.

To enhance the peri-implant soft tissue seal, various strategies have been explored:

- -

Modifying abutment surfaces to improve tissue attachment. [

15,

16,

17,

18]

- -

Adjusting prosthetic designs (e.g., emergence profile, platform-switching) to enhance stability. [

19,

20,

21]

- -

Placing implants subcrestally to improve soft tissue adaptation and protective function. [

22]

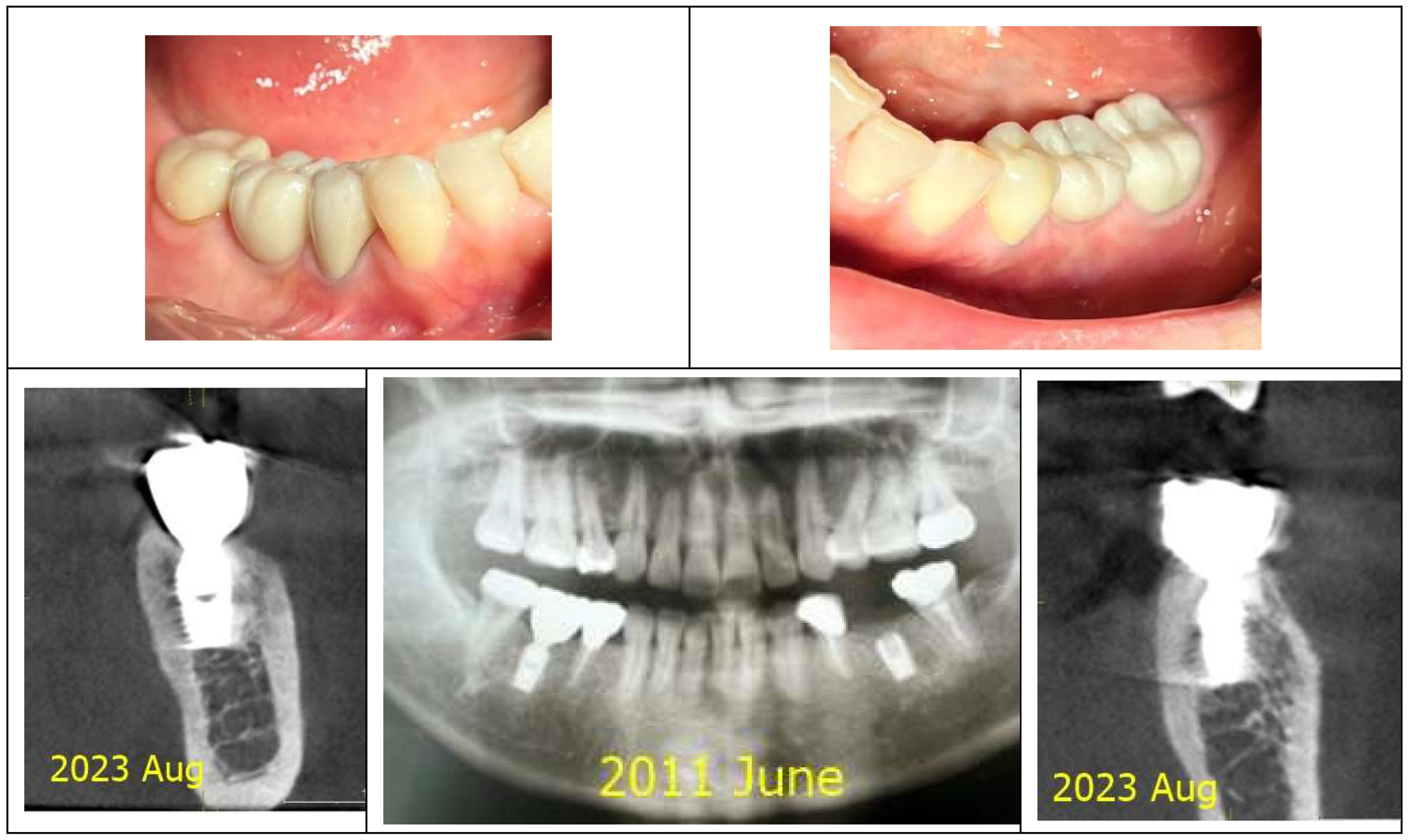

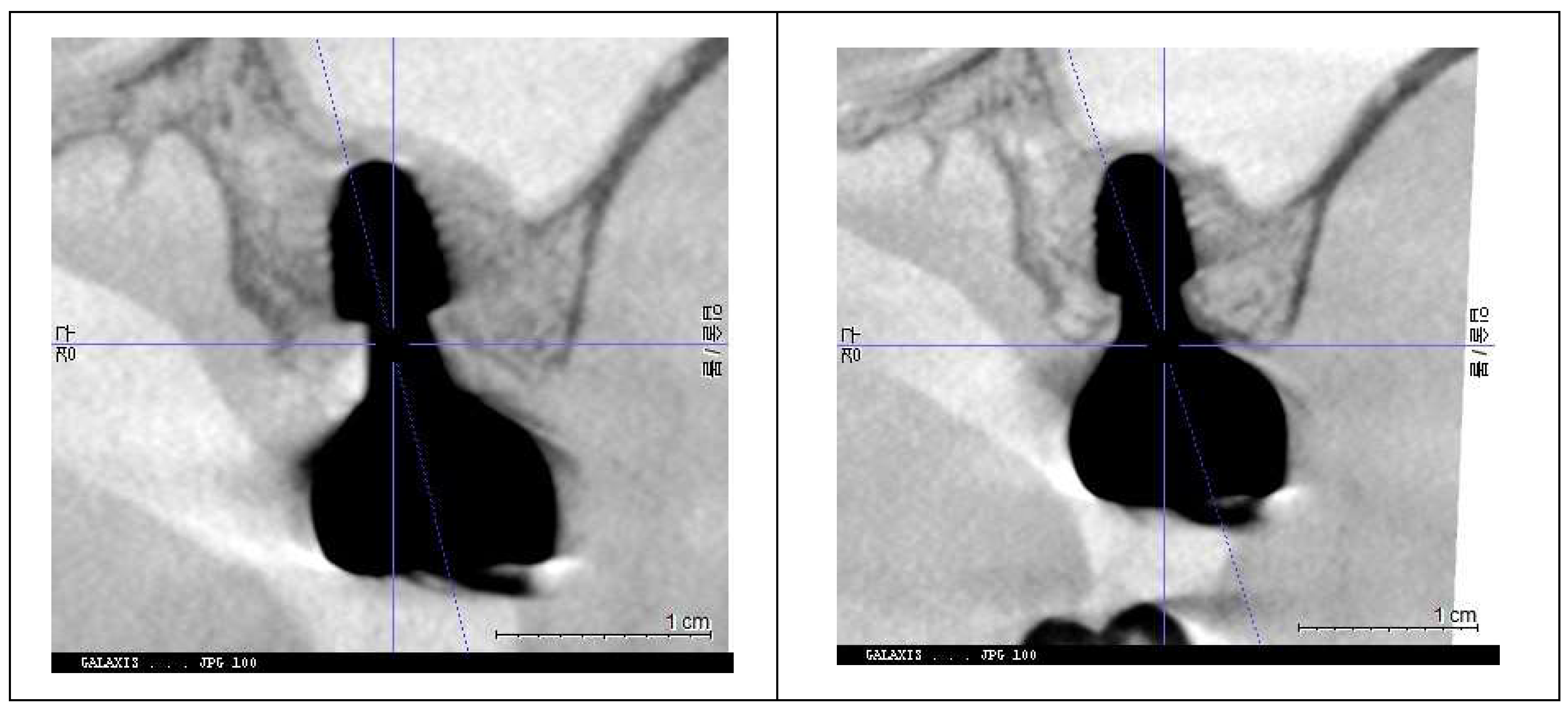

Among these, subcrestal implant placement (SPI) has gained attention for promoting bone remodeling and soft tissue stability, particularly in cases with thin peri-implant mucosa. Several studies have shown that subcrestally placed implants (SPIs) promote stable peri-implant conditions and minimize crestal bone loss. (

Figure 1) [

23,

24,

25,

26]

Figure 1.

Results after 10 years of subcrestally placed implants (SPI) – Fixtures were placed subcrestally, with X-rays showing no crestal bone loss and clinical photos demonstrating healthy peri-implant soft tissue and a natural emergence profile. This approach reflects a trend seen with Bicon implants during the 2000s to 2010s, where implant fixtures were often placed slightly deeper than those of other systems to support lasting stability.

Figure 1.

Results after 10 years of subcrestally placed implants (SPI) – Fixtures were placed subcrestally, with X-rays showing no crestal bone loss and clinical photos demonstrating healthy peri-implant soft tissue and a natural emergence profile. This approach reflects a trend seen with Bicon implants during the 2000s to 2010s, where implant fixtures were often placed slightly deeper than those of other systems to support lasting stability.

Most research on peri-implant soft tissue has focused on horizontal extensions between the implant restoration and underlying tissue, while vertical dimensions remain underexplored.

With subcrestally placed implants (SPI), a longer and broader submucosal area forms around the implant abutment and restoration. While most research has focused on the horizontal extension of this submucosal transition zone, this case suggests that the Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD)—the vertical space between the crestal bone and the implant restoration—may play a critical role in biological stability. Notably, peri-implant mucositis was successfully treated in this case by adjusting the CRD through prosthodontic modifications.

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old woman underwent extraction of her

lower right first molar on

June 3, 2020, due to a severe periodontal abscess. On

September 22, 2020, her

upper left first molar was extracted due to a crown and root fracture. (

Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Initial clinical image of the upper left first molar on the patient’s first visit (September 22, 2020), showing a fracture line extending from the crown to the root before extraction.

Figure 2.

Initial clinical image of the upper left first molar on the patient’s first visit (September 22, 2020), showing a fracture line extending from the crown to the root before extraction.

On

October 29, 2020, an implant (

Oneplant, Warrentec, Seoul, South Korea) was placed at the

upper left first molar site, with a transcrestal sinus lift and bone grafting. (

Figure 3) A second

Oneplant implant was placed at

the lower right first molar site on

December 21, 2020.

Figure 3.

October 29, 2020 – Implant placement at the upper left first molar site with sinus lift and bone grafting surgery.

Figure 3.

October 29, 2020 – Implant placement at the upper left first molar site with sinus lift and bone grafting surgery.

The second-stage surgery for healing abutment connection was performed on March 3, 2021. Healing abutments (6.0 mm diameter, 5.0 mm height) were placed at both sites.

Final restoration for the lower right molar was completed on March 18, 2021, using a 4.5 mm diameter, 3 mm gingival cuff abutment, while the upper left molar was restored on March 25, 2021, with a 4.5 mm diameter, 4 mm gingival cuff abutment.

Zirconia crowns were cemented onto prefabricated abutments (Warrentec) using the extraoral cementation technique (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

March 25, 2021 – Restoration completed using a 4 mm gingival cuff abutment.

Figure 4.

March 25, 2021 – Restoration completed using a 4 mm gingival cuff abutment.

She was instructed on implant care, including thorough cleaning with proximal brushes and water irrigation devices.

For 19 months, the patient showed no signs of implant-related disease, with routine check-ups confirming stable function. However, on October 17, 2022, she reported discomfort around the upper left first molar implant, including gingival bleeding, swelling, and food impaction.

Clinical examination revealed redness and slight swelling in the peri-implant soft tissue, though radiographic evaluation showed no bone loss. Consequently, peri-implant mucositis was diagnosed at the upper left first molar implant, while the lower right first molar implant remained healthy.

Treatment included reinforcing oral hygiene, increasing recall visits with saline irrigation, and applying topical antibiotics. However, symptoms persisted, particularly discomfort from food impaction. Despite a tight interproximal contact and a natural crown profile with sufficient embrasure space for cleaning, food accumulated in the sulcus rather than in interproximal or contact areas. In contrast, the lower right first molar implant remained stable with no signs of peri-implant disease.

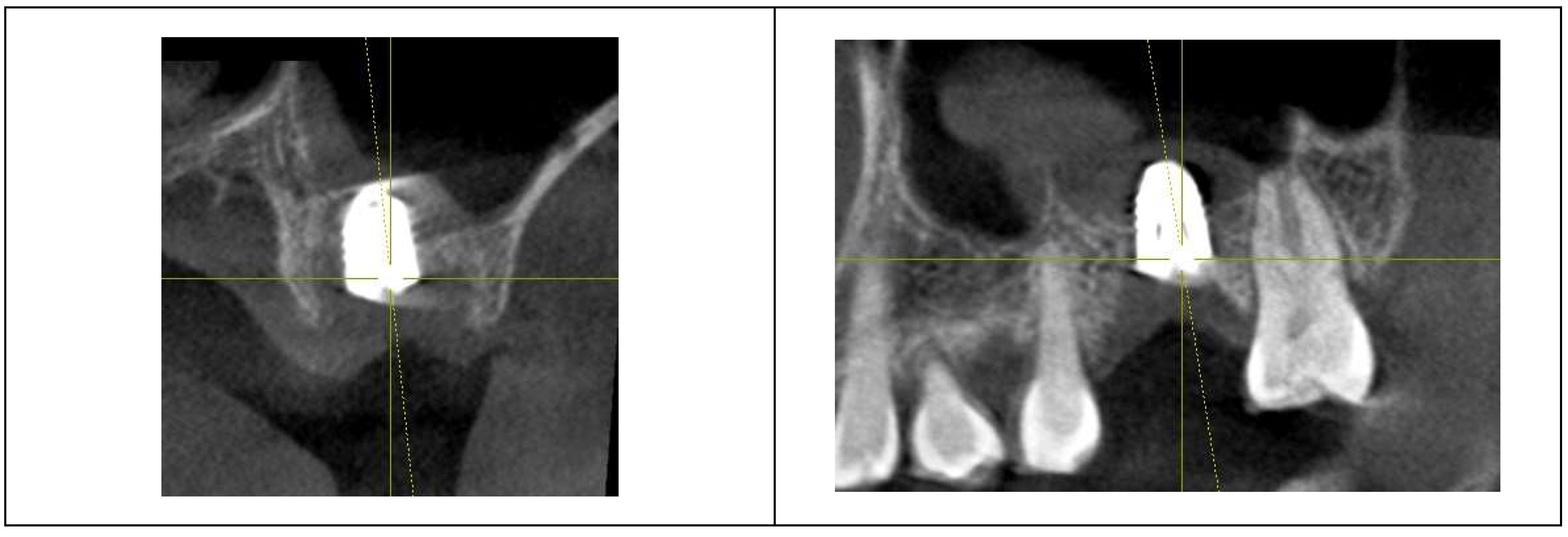

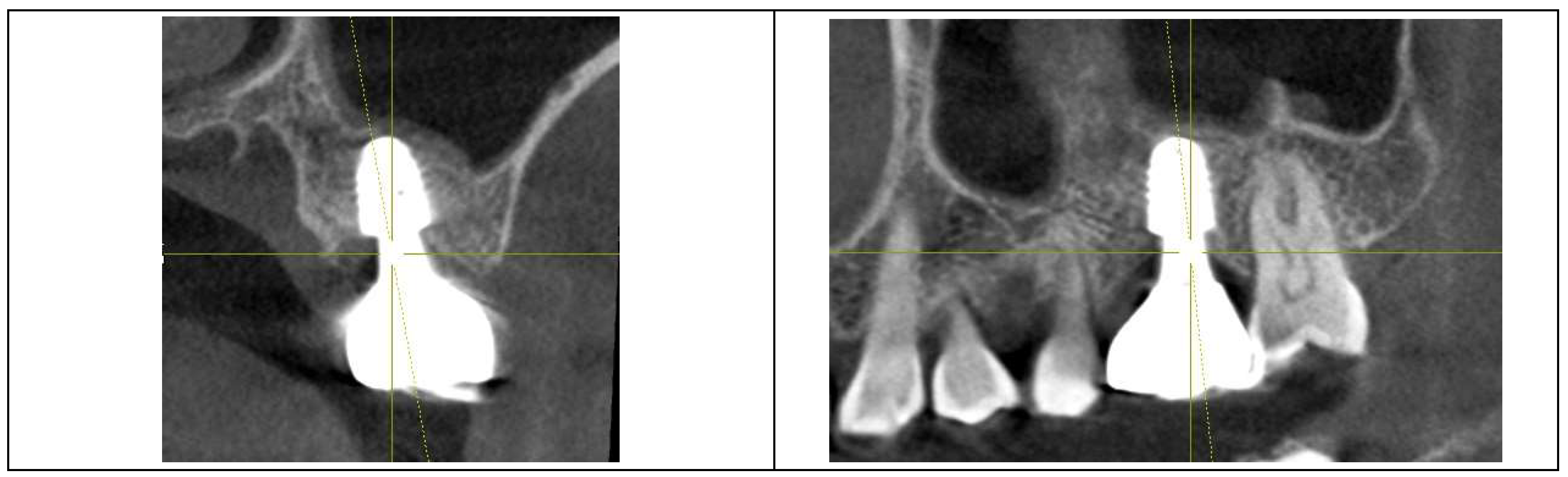

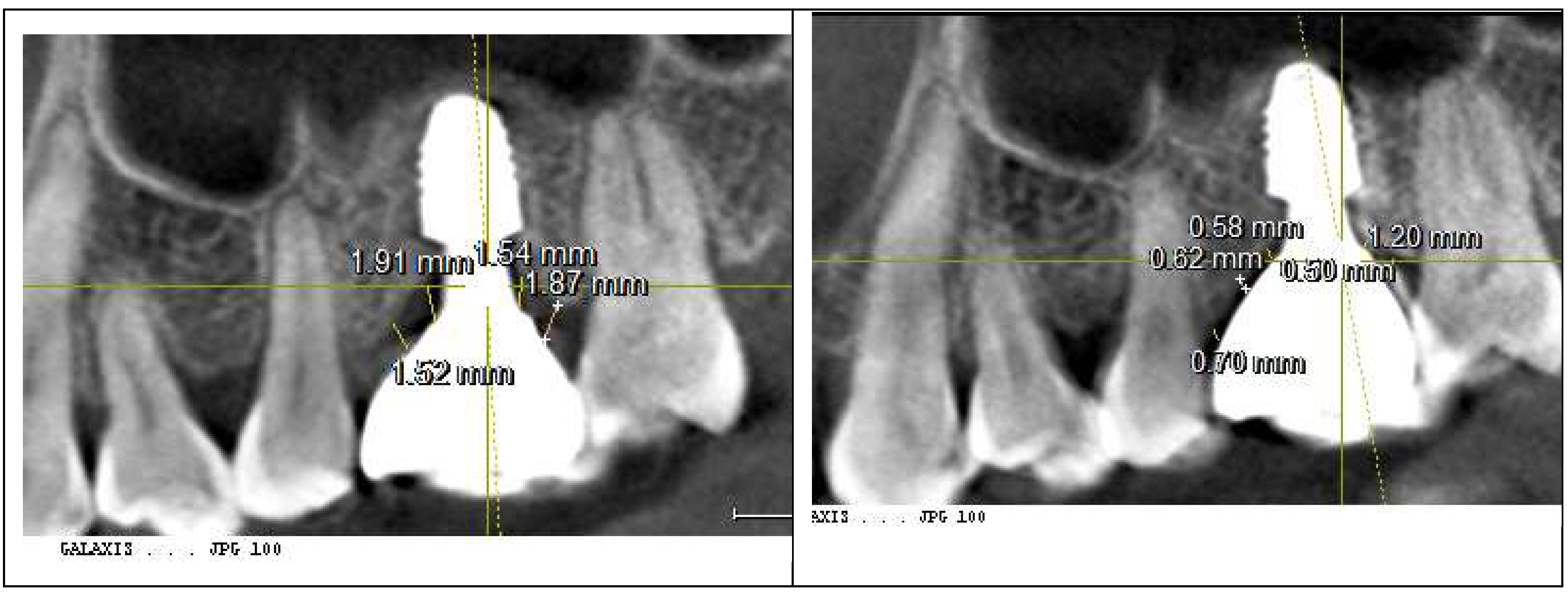

To assess peri-implant soft tissue structure and bone topography, a Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) scan was performed, focusing on the Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD)—the vertical distance between the implant restoration and the crestal bone—to identify the optimal treatment approach. The results are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1.

presents the measurements of the Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD), which quantifies the vertical distance between the implant restoration and the crestal bone. The values are divided into central CRD (cCRD) and peripheral CRD (pCRD) to distinguish the dimensional variations along the implant interface. These measurements are taken at both central and peripheral locations, evaluating the mesial (M), distal (D), buccal (B), and lingual (L) aspects around the implants of the upper left first molar and lower first molar. The data were collected from the CBCT scan conducted on October 26, 2021.

Table 1.

presents the measurements of the Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD), which quantifies the vertical distance between the implant restoration and the crestal bone. The values are divided into central CRD (cCRD) and peripheral CRD (pCRD) to distinguish the dimensional variations along the implant interface. These measurements are taken at both central and peripheral locations, evaluating the mesial (M), distal (D), buccal (B), and lingual (L) aspects around the implants of the upper left first molar and lower first molar. The data were collected from the CBCT scan conducted on October 26, 2021.

| |

Upper left 1st molar |

Lower right 1st molar |

| cCRD |

pCRD |

cCRD |

pCRD |

| M |

1.52 |

1.91 |

0.36 |

0.91 |

| D |

1.54 |

1.87 |

0.78 |

1.66 |

| B |

1.88 |

2.04 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

| L |

0.98 |

2.05 |

0.6 |

1.41 |

| Average |

1.48 |

1.97 |

0.51 |

1.07 |

Measurement of Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD)

CRD refers to the vertical space between the crestal bone and the implant restoration. It is measured at two locations: centrally (cCRD) and peripherally (pCRD) to evaluate dimensional variations along the implant interface.

The CRD for the upper left first molar implant was consistently larger than that for the lower right first molar implant. The central CRD (cCRD) difference was 0.97 mm (1.48 mm – 0.51 mm), while the peripheral CRD (pCRD) difference was 0.90 mm (1.97 mm – 1.07 mm). As no CBCT-based CRD measurements exist in the literature, a clinical study by Won, analyzing CRD (or Soft Tissue Thickness, STT) in 20 cases of subcrestally placed implants with stable outcomes over two years, served as a reference. That study reported an average pCRD of 0.6 mm and cCRD of 0.3 mm (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of CRD measurements in 20 cases of subcrestally placed implants, as analyzed by Won. The average pCRD was 0.6 mm, and the average cCRD was 0.3 mm.

Table 2.

Summary of CRD measurements in 20 cases of subcrestally placed implants, as analyzed by Won. The average pCRD was 0.6 mm, and the average cCRD was 0.3 mm.

| |

cCRD |

pCRD |

| |

cCRD/M |

cCRD/D |

cCRD/B |

cCRD/L |

pCRD/M |

pCRD/D |

pCRD/B |

pCRD/L |

| average |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

| |

0.3 |

0.6 |

The analysis indicated that the increased CRD in the upper left first molar implant likely contributed to peri-implant mucositis. To address this, the restoration was remade to adjust the CRD to the optimal range. A new restoration with a 4.5 mm diameter, 3 mm gingival cuff abutment was fabricated and delivered to the patient (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

October 31, 2022 The restoration was remade with gingival cuff 3 mm abutment.

Figure 5.

October 31, 2022 The restoration was remade with gingival cuff 3 mm abutment.

Following the restoration remake, the patient reported no further discomfort, including gingival bleeding, swelling, or food impaction. Clinical examination confirmed healthy peri-implant soft tissue with no radiographic bone resorption. Probing with the Implant Paper Point Probe (IPPP) (Sure Endo, Seoul, South Korea) at a yield strength of 0.35 N showed a consistent depth of less than 1 mm, with no bleeding, confirming the successful resolution of peri-implant mucositis.

Figure 6 compares the restorations before and after revision, highlighting profile differences. It also includes a post-revision panoramic X-ray and clinical photographs taken on October 31, 2022 (

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The upper left image presents a comparison of the two restorations before and after the revision, while the upper right image shows a panoramic X-ray taken post-revision. The lower two images display the clinical appearance of the upper left first molar implant restoration following the revision procedure conducted on October 31, 2022.

Figure 6.

The upper left image presents a comparison of the two restorations before and after the revision, while the upper right image shows a panoramic X-ray taken post-revision. The lower two images display the clinical appearance of the upper left first molar implant restoration following the revision procedure conducted on October 31, 2022.

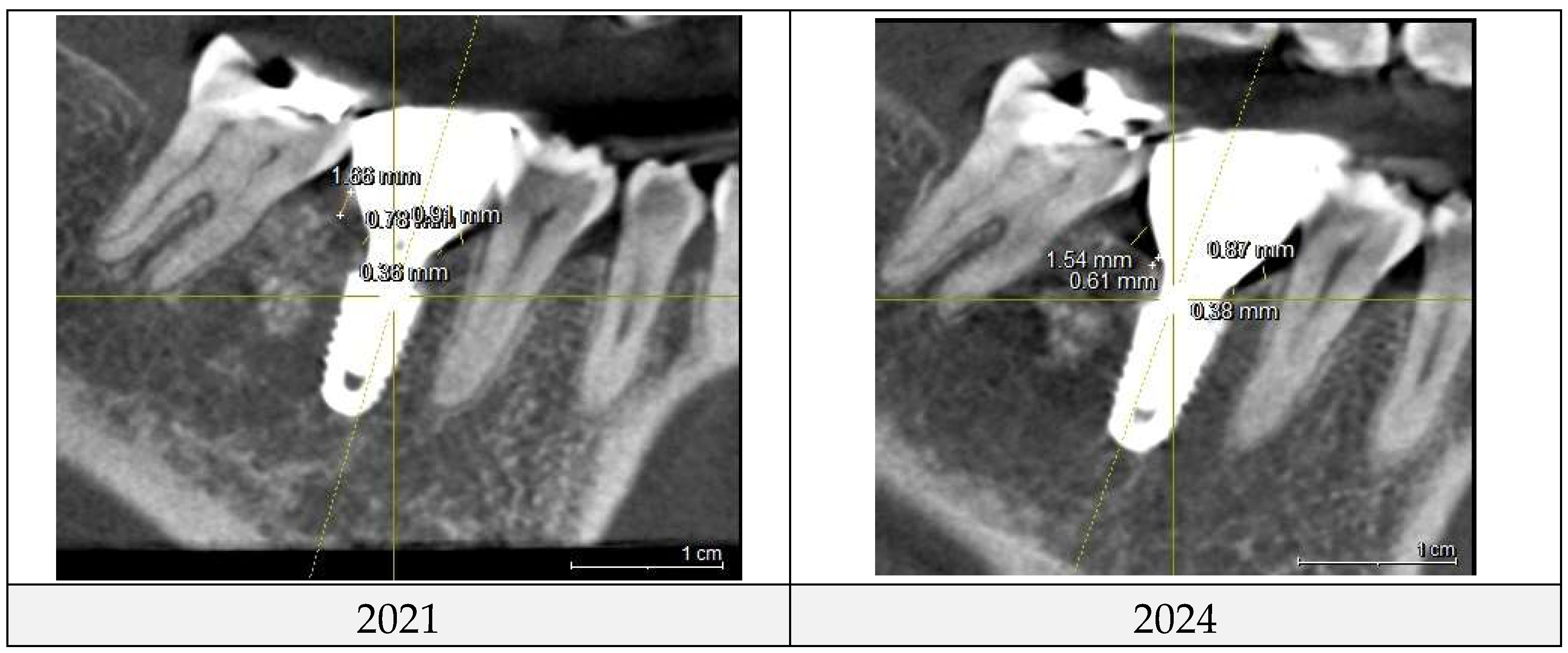

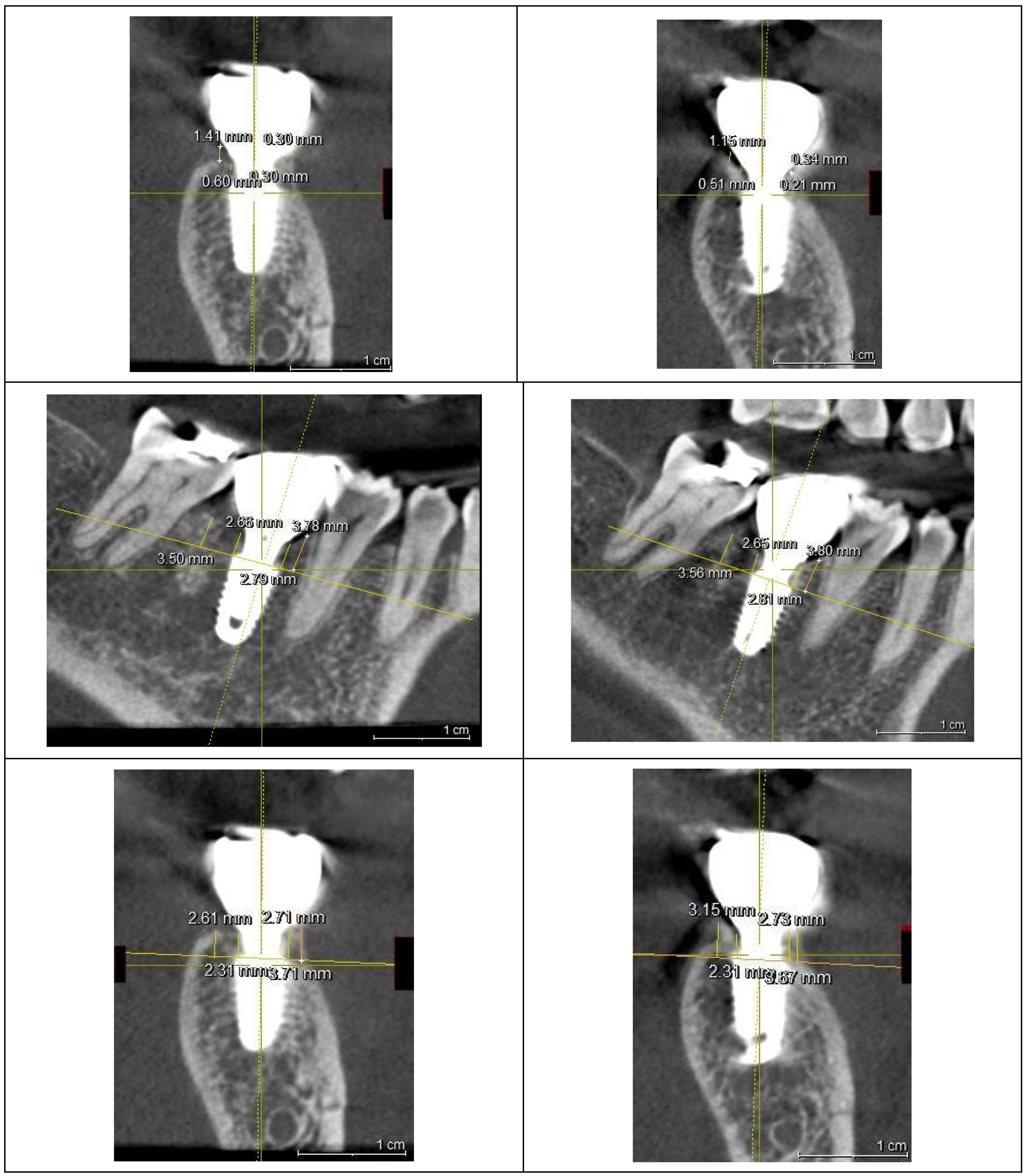

Radiographic and Clinical Analysis: A Split-Mouth Comparison

The two implant sites were analyzed in a split-mouth study using CBCT scans from 2021 and 2024 to assess peri-implant soft tissue and bone structure. CRD and DP measurements were obtained through CBCT imaging and clinical evaluations to examine their correlation with peri-implant health, particularly in managing peri-implant mucositis.

Panoramic and CBCT scans were taken using Sirona Dental Systems (ORTHOPHOS XG 3D or AXEOS) and analyzed with SIDEXIS and GALILEOS Implant Viewer (version 1.9.5605.25519 ID7).

Radiographic Measurements

Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD)

CRD was measured at two locations:

- -

Central CRD (cCRD): The vertical distance from the crestal bone to the restoration at the outer edge of the implant fixture diameter.

- -

Peripheral CRD (pCRD): The vertical distance at the most peripheral part of the crestal bone in the buccolingual direction and at the most coronal midpoint of the mesiodistal crestal bone.

Depth of Placement (DP)

DP was measured perpendicularly at the same central and peripheral locations:

- -

Central DP (cDP): The distance from the implant fixture top (or fixture-abutment connection) to the crestal bone at the outer fixture diameter.

- -

Peripheral DP (pDP): The distance from the implant fixture top (or fixture-abutment connection) to the crestal bone at the most coronal points in the buccal, lingual, mesial, and distal aspects.

Clinical Evaluation

Peri-implant soft tissue health was assessed using:

- -

Implant Paper Point Probing (IPPP): Standardized method for measuring probing depths.

- -

Bleeding on Probing (BOP): Indicator of inflammation.

- -

Visual Assessment: Identification of redness and swelling as signs of peri-implant tissue health.

Results

CRD and DP measurements for the upper left and lower right first molar implants were recorded in 2021 and 2024. Averages were calculated and compared over time, with results summarized in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

-

A.

Control site (the lower right 1st molar) for comparison

- a)

Changes of CRD

Table 3.

Changes in CRD from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the control site (the lower right first molar implant).

Table 3.

Changes in CRD from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the control site (the lower right first molar implant).

| pCRD |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

0.91 |

0.87 |

-0.04 |

| D |

1.66 |

1.54 |

-0.12 |

| B |

0.3 |

0.34 |

0.04 |

| L |

1.41 |

1.15 |

-0.26 |

| average |

1.07 |

0.98 |

-0.10 |

| cCRD |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

0.36 |

0.38 |

0.02 |

| D |

0.78 |

0.61 |

-0.17 |

| B |

0.3 |

0.21 |

-0.09 |

| L |

0.6 |

0.51 |

-0.09 |

| average |

0.51 |

0.43 |

-0.08 |

Table 4.

Changes in Depth of Placement (DP) from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the control Site (the lower right first molar implant) The DP changes over time indicate variations in crestal bone level, signifying potential bone loss or gain around the implant.

Table 4.

Changes in Depth of Placement (DP) from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the control Site (the lower right first molar implant) The DP changes over time indicate variations in crestal bone level, signifying potential bone loss or gain around the implant.

| pDP |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

3.78 |

3.8 |

0.02 |

| D |

3.5 |

3.56 |

0.06 |

| B |

3.71 |

3.67 |

-0.04 |

| L |

2.61 |

3.15 |

0.54 |

| average |

3.4 |

3.55 |

0.15 |

| cDP |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

2.79 |

2.81 |

0.02 |

| D |

2.65 |

2.65 |

0 |

| B |

2.71 |

2.73 |

0.02 |

| L |

2.31 |

2.31 |

0 |

| average |

2.62 |

2.63 |

0.01 |

Table 5.

Clinical parameters for soft tissue condition at the lower right first molar implant. This table presents the clinical assessment of soft tissue health around the lower right first molar implant, including Implant Paper Point Probing (IPPP), Bleeding on Probing (BOP), redness, and swelling, demonstrating a healthy soft tissue state.

Table 5.

Clinical parameters for soft tissue condition at the lower right first molar implant. This table presents the clinical assessment of soft tissue health around the lower right first molar implant, including Implant Paper Point Probing (IPPP), Bleeding on Probing (BOP), redness, and swelling, demonstrating a healthy soft tissue state.

| Depth of Probing |

BOP |

redness |

swelling |

| Less than 1 mm |

no |

no |

no |

-

B.

TreatmenT site (the upper left 1st molar) for peri-implant mucositis

- a)

Changes of CRD

Table 6.

Changes in CRD from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the treatment site (the upper left first molar implant).

Table 6.

Changes in CRD from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the treatment site (the upper left first molar implant).

| pCRD |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

1.91 |

0.58 |

-1.33 |

| D |

1.87 |

1.2 |

-0.67 |

| B |

2.04 |

0.76 |

-1.28 |

| L |

2.05 |

0.99 |

-1.06 |

| average |

1.97 |

0.88 |

-1.09 |

| cCRD |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

1.52 |

0.62 |

-0.90 |

| D |

1.54 |

0.5 |

-1.04 |

| B |

1.88 |

0.58 |

-1.3 |

| L |

0.98 |

0.5 |

-0.48 |

| average |

1.48 |

0.55 |

-0.93 |

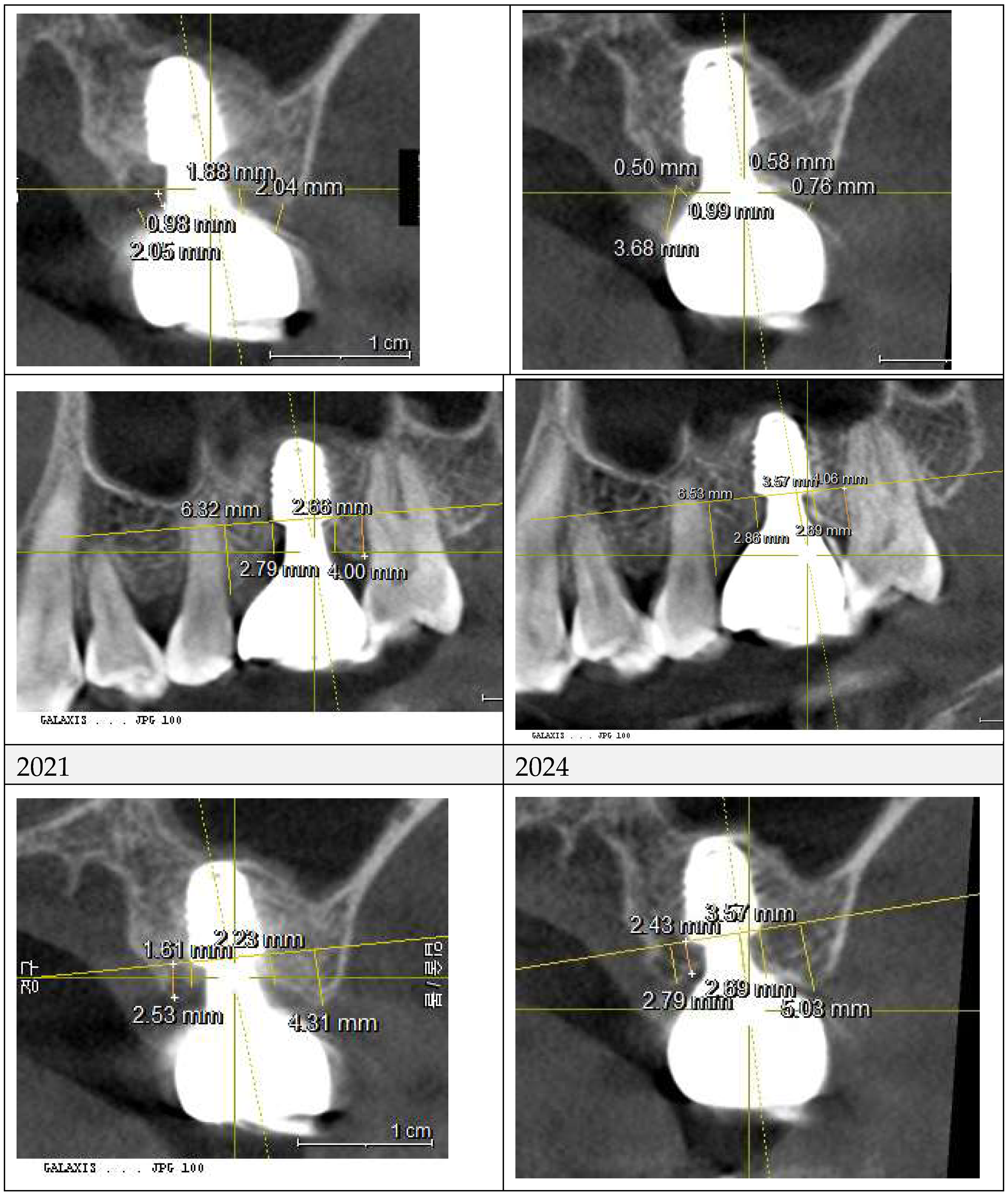

Table 7.

Changes in Depth of Placement (DP) from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the treatment site (the upper left first molar implant) The DP changes over time indicate variations in crestal bone level, signifying potential bone loss or gain around the implant.

Table 7.

Changes in Depth of Placement (DP) from 2021 to 2024 at the peripheral and central areas for the treatment site (the upper left first molar implant) The DP changes over time indicate variations in crestal bone level, signifying potential bone loss or gain around the implant.

| pDP |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

6.32 |

6.53 |

0.21 |

| D |

4.00 |

4.06 |

0.06 |

| B |

4.31 |

5.03 |

0.72 |

| L |

1.61 |

2.79 |

1.18 |

| average |

4.06 |

4.60 |

0.54 |

| cDP |

2021 |

2024 |

changes |

| M |

2.79 |

2.86 |

0.07 |

| D |

2.66 |

2.69 |

0.03 |

| B |

2.23 |

3.57 |

1.34 |

| L |

2.53 |

2.43 |

-0.1 |

| average |

2.55 |

2.89 |

0.34 |

Table 8.

Clinical parameters for soft tissue condition at the upper left first molar implant. This table presents the clinical assessment of soft tissue health around the upper left first molar implant, including Implant Paper Point Probing (IPPP), Bleeding on Probing (BOP), redness, and swelling, demonstrating a healthy soft tissue state after revision.

Table 8.

Clinical parameters for soft tissue condition at the upper left first molar implant. This table presents the clinical assessment of soft tissue health around the upper left first molar implant, including Implant Paper Point Probing (IPPP), Bleeding on Probing (BOP), redness, and swelling, demonstrating a healthy soft tissue state after revision.

| Depth of Probing |

BOP |

redness |

swelling |

| Less than 1 mm |

no |

no |

no |

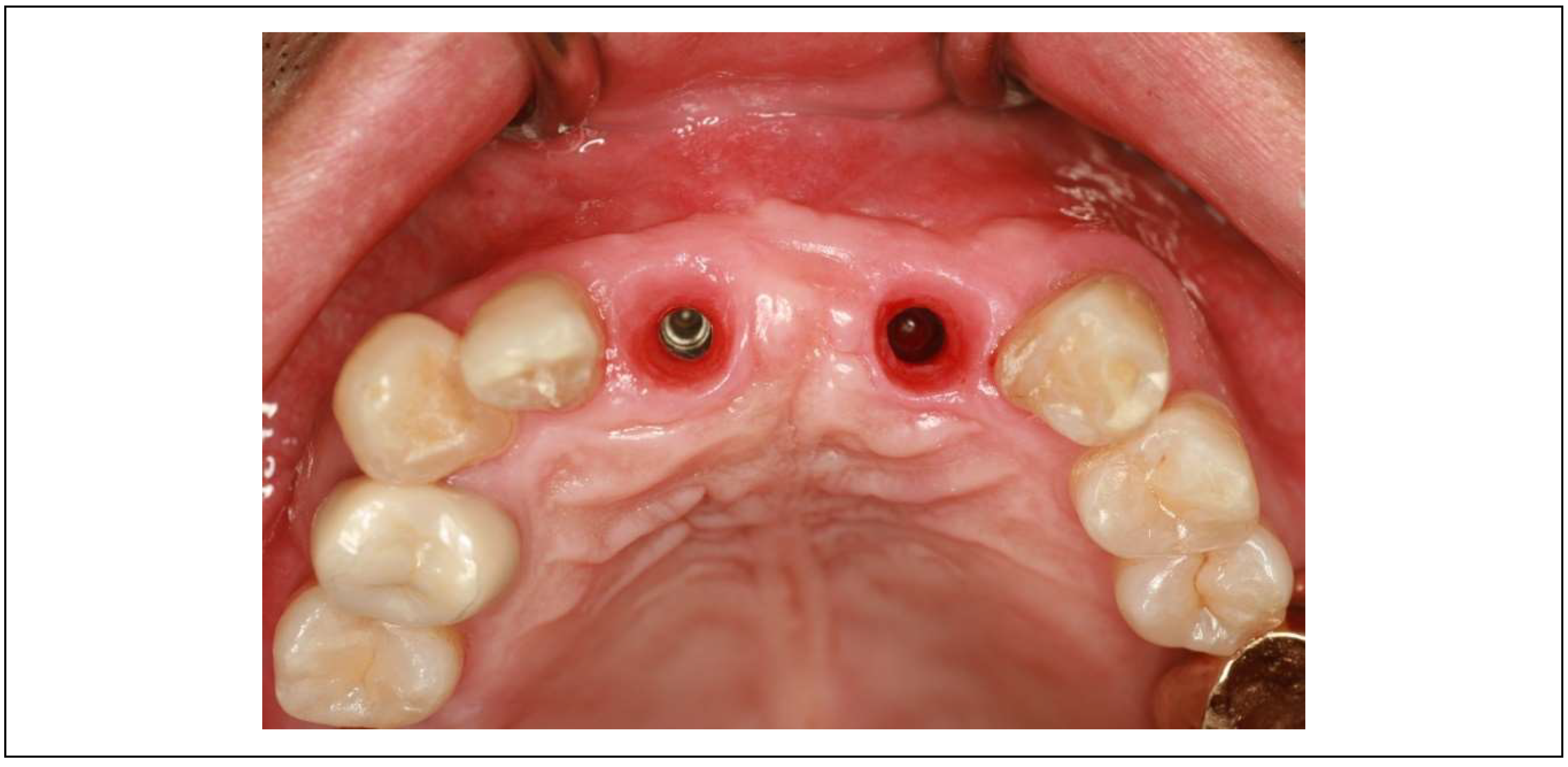

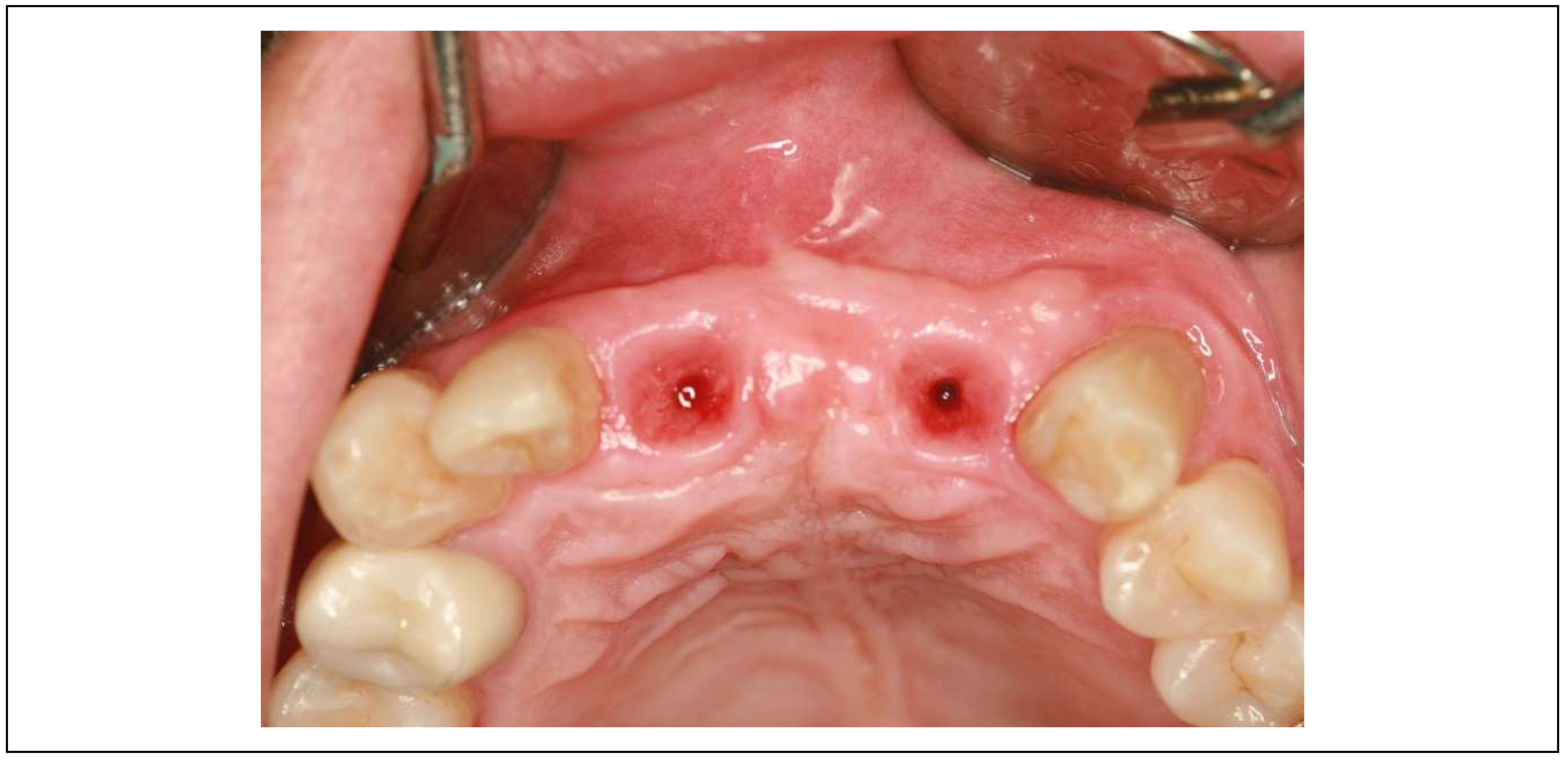

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the radiographic changes observed from 2021 to 2024 at the lower right first molar implant site (control site) and the upper left first molar implant site (experimental site), respectively. (

Figure 7,

Figure 8) The clinical photographs taken in 2024 (

Figure 9) depict the final results, showcasing both a stable and natural appearance for both implant sites.

Figure 7.

This image illustrates the X-ray measurements conducted on the lower right first molar implant, comparing data from 2021 and 2024.

Figure 7.

This image illustrates the X-ray measurements conducted on the lower right first molar implant, comparing data from 2021 and 2024.

Figure 8.

This image illustrates the X-ray measurements conducted on the upper left first molar implant, comparing data from 2021 and 2024.

Figure 8.

This image illustrates the X-ray measurements conducted on the upper left first molar implant, comparing data from 2021 and 2024.

Figure 9.

Clinical images of control and experimental sites post-revision. This figure presents clinical photographs of the control and experimental implant sites following the revision procedure. Both sites exhibit a natural and healthy appearance, indicating successful soft tissue adaptation and restoration aesthetics, taken at 2024.

Figure 9.

Clinical images of control and experimental sites post-revision. This figure presents clinical photographs of the control and experimental implant sites following the revision procedure. Both sites exhibit a natural and healthy appearance, indicating successful soft tissue adaptation and restoration aesthetics, taken at 2024.

Summary of Results

The upper left molar exhibited significant changes in soft tissue thickness and peri-implant mucositis, whereas the lower right molar maintained a stable CRD (

Table 9).

Table 9.

Summary of the comparison for the average changes between the control site (lower right molar) and the treatment site (upper left molar) for CRD.

Table 9.

Summary of the comparison for the average changes between the control site (lower right molar) and the treatment site (upper left molar) for CRD.

| |

Control site |

Treated site |

| The average change in pCRD |

-0.10 |

-1.09 |

| The average change in cCRD |

-0.08 |

-0.93 |

Following prosthodontic adjustment to reduce CRD, mucositis in the upper left implant resolved, with no BOP and probing depths remaining below 1 mm.

The post-revision evaluation highlights structural changes in peri-implant soft tissue and their impact on implant health.

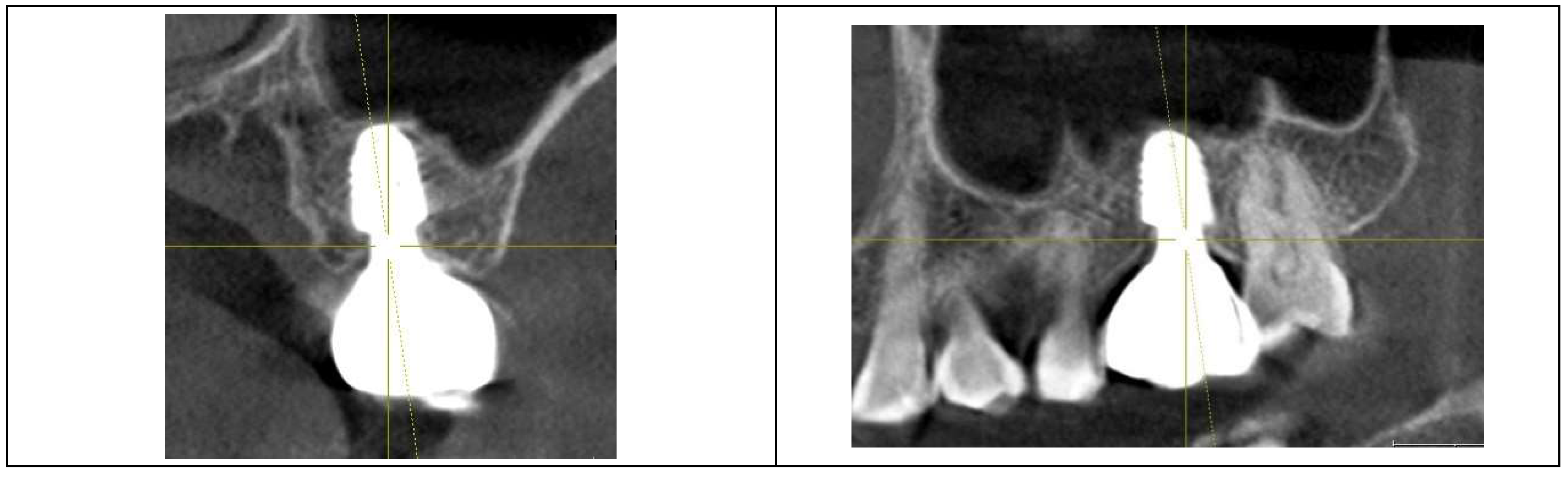

Figure 10 compares X-rays from October 2021 and July 2024, showing a marked decrease in Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD) after restoration modification. (

Figure 10) The reduction ensured the gap was fully occupied by peri-implant soft tissue, eliminating voids. This suggests that maintaining CRD within a critical range is essential for a stable biological seal, reinforcing the soft tissue barrier against bacterial infiltration.

Figure 10.

Comparison of X-rays taken in October 2021 and July 2024 after the restoration revision, demonstrating a decrease in the CRD. When the CRD is maintained within the critical range, it can be inferred that the gap space is occupied exclusively by peri-implant soft tissue, without voids, and the GRD can be represented as Soft Tissue Thickness (STT).

Figure 10.

Comparison of X-rays taken in October 2021 and July 2024 after the restoration revision, demonstrating a decrease in the CRD. When the CRD is maintained within the critical range, it can be inferred that the gap space is occupied exclusively by peri-implant soft tissue, without voids, and the GRD can be represented as Soft Tissue Thickness (STT).

These findings underscore the importance of CRD optimization in implant restoration and the need for histologic evidence to further validate its role in peri-implant soft tissue stability.

Discussions

1. Biological Role of Peri-Implant Soft Tissue

Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis are infectious complications primarily caused by the disruption of the peri-implant soft tissue seal [

12,

13]. This soft tissue acts as a biological barrier, protecting the crestal bone from bacterial infiltration. The hard and soft tissues surrounding osseointegrated implants are crucial for mitigating potential challenges [

27]. Linkevicius et al. emphasized the role of vertical soft tissue thickness in forming a strong biologic seal [

14] but did not fully address its three-dimensional architecture. This omission raises concerns about pocket formation, which can facilitate bacterial colonization and food accumulation, particularly in subcrestally placed implants (SPI), where deeper positioning complicates soft tissue stability. Bosshardt et al. described periodontal pocket formation as initiating with junctional epithelium breakdown, reinforcing its role as the first line of defense and the importance of probing as a diagnostic tool [

28].

Adequate Supracrestal Tissue Height (STH) is essential for maintaining biologic width and preventing esthetic issues, but excessive STH can contribute to pocket formation and peri-implant disease. A balanced STH of 3–5 mm is recommended for optimal tissue health [

7]. While studies emphasize the vertical role of peri-implant soft tissue in stability, little research has explored the horizontal component and the width of the transitional area, which inevitably forms in SPI cases.

This case report suggests that an optimal CRD stabilizes peri-implant soft tissue architecture. Proper CRD maintenance may limit epithelial downgrowth, prevent deep pockets, and reinforce the biological seal.

The positive outcome has been sustained up to the present, as of March 2025, following the implant restoration remake on October 31, 2022, which optimized the CRD. This stability is evidenced by the patient’s absence of pain or discomfort and confirmed through objective clinical evaluations, including visual inspection and probing depths consistently within 1 mm.

Clinical improvement in peri-implant mucositis after CRD optimization suggests structural changes in peri-implant soft tissue.

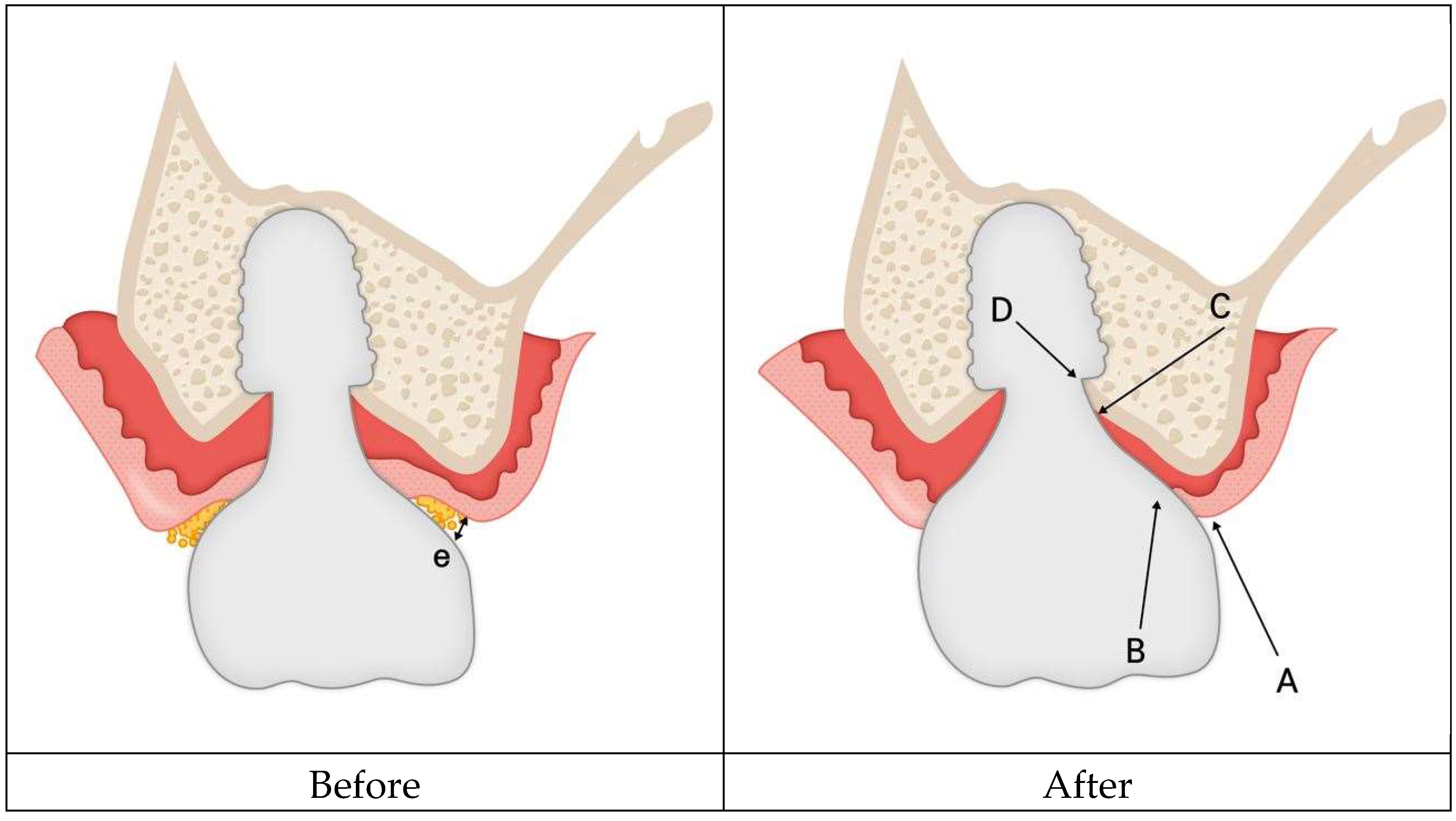

Figure 11 illustrates this proposed histologic adaptation. Before modification, the peri-implant interface had void spaces (pockets) alongside sulcular epithelium and connective tissue. After restoration revision, the void was likely eliminated, reorganizing peri-implant soft tissue into sulcular epithelium, junctional epithelium, and connective tissue.

Figure 11.

Hypothetical schematic representation of histologic changes in peri-implant soft tissue following restoration modification. Before modification, the Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD) contained voids (pockets), sulcular epithelium, and connective tissue. After modification, it is hypothesized that the CRD was restructured into a stable peri-implant soft tissue barrier, consisting of sulcular epithelium, junctional epithelium, and connective tissue, reinforcing the biological seal and reducing the risk of peri-implant inflammation.

Figure 11.

Hypothetical schematic representation of histologic changes in peri-implant soft tissue following restoration modification. Before modification, the Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD) contained voids (pockets), sulcular epithelium, and connective tissue. After modification, it is hypothesized that the CRD was restructured into a stable peri-implant soft tissue barrier, consisting of sulcular epithelium, junctional epithelium, and connective tissue, reinforcing the biological seal and reducing the risk of peri-implant inflammation.

This transformation may enhance the biologic seal, prevent bacterial infiltration, and promote peri-implant health. While inferred from clinical and radiographic data, further histologic research is needed to confirm this structural adaptation.

2. Clinical Indicators and Diagnosis of Peri-Implant Disease

Peri-implant mucositis presents as redness, swelling, bleeding on probing (BOP), suppuration on probing (SOP), and increased probing pocket depth (PPD), while peri-implantitis is confirmed by radiographic bone loss. Periodic probing is crucial for monitoring peri-implant conditions, as increased PPD with profuse BOP and SOP strongly correlates with peri-implantitis [

29].

The diagnosis of peri-implant mucositis is based on clinical criteria without requiring histologic confirmation. Unlike peri-implantitis, it is reversible. Junctional epithelium destruction is a hallmark of gingivitis, emphasizing hemidesmosomes’ role in periodontal gingiva [

26]. However, peri-implant tissues differ morphologically, particularly in their weaker hemidesmosomal attachment, making them more vulnerable to bacterial infiltration and disease progression [

29].

Despite skepticism regarding hemidesmosomes’ role in implants [

10], resistance during probing suggests peri-implant soft tissue retains some sealing ability, similar to natural teeth [

9,

30]. Berglundh and Lindhe highlighted the significance of biological width in protecting the underlying bone [

31]. This underscores the need for peri-implant soft tissue integrity to maintain peri-implant health and prevent disease progression.

Probing plays a crucial role in peri-implant soft tissue health, aiding in early disease detection and preventing progression toward peri-implant bone loss. When combined with clinical signs like erythema, BOP, SOP, and swelling, it provides a comprehensive assessment of peri-implant tissue health, enabling timely intervention [

29].

3. Probing Implants’ Sulcus with IPPP (Implant Paper Point Probing)

Periodontal sulcus depth in natural teeth is measured using probes with limited force, defined as the distance from the gingival margin to the most apically penetrated portion of the junctional epithelium. In healthy conditions, the probe tip remains within the junctional epithelium, but inflammation allows deeper penetration into connective tissue, compromising the epithelial barrier.

Similarly, peri-implant inflammation causes deeper probe penetration, approaching the alveolar bone crest. The 2017 World Workshop recommended probing peri-implant pockets with a light force (~0.25 N) as healthy depths remain <5 mm [

13]. Controlled probing at 0.2 N has shown similar penetration in implants and natural teeth, aligning with epithelial barrier dimensions [

32].

A major clinical challenge is applying a standardized probing force. Automated probes exist but are limited by implant prosthesis curvature and design [

33]. To address this, the author used the Implant Paper Point Probe (IPPP), developed by Suredent in South Korea. With a yield strength of 0.25–0.35 N, IPPP flexibly penetrates the sulcus, bending under excess force to prevent tissue damage and ensuring controlled probing. This makes it a reliable alternative to metal probes for implants.

IPPP also enhances diagnostic accuracy by detecting sulcus fluid and BOP, observable through wetting and discoloration. While some authors express concerns about tissue damage from probing with metal or plastic instruments, IPPP alleviates this risk by bending upon reaching a preset force, preventing excessive penetration and safeguarding peri-implant soft tissue.

4. Possible Explanation for the Results from This Study

This case study primarily examined the impact of Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD) on peri-implant soft tissue health. The key finding was that maintaining CRD within an optimal range was associated with peri-implant soft tissue stability, preventing the onset of peri-implant mucositis—a precursor to peri-implantitis.

To explain this observation, three possible mechanisms are proposed:

-

Preservation of Hemidesmosomal Attachment

- -

By eliminating pocket formation at the peri-implant interface, the hemidesmosomal attachment of the junctional epithelium remains functional at the entrance.

- -

This prevents sulcular epithelial downgrowth and maintains the integrity of the peri-implant mucosa, reinforcing the soft tissue barrier against bacterial infiltration.

-

Hydraulic Pressure from the Connective Tissue

- -

A stable junctional epithelium at the entrance allows the connective tissue beneath the implant restoration to exert hydraulic pressure against the prosthesis.

- -

This pressure generates a protective sealing force, further contributing to the biologic defense mechanism.

-

Sustained Structural and Immunologic Integrity

- -

-

Maintaining structural stability ensures that each component of the peri-implant soft tissue fulfills its specialized role:

- ▪

Sulcular epithelium: High turnover rate facilitating rapid barrier renewal.

- ▪

Junctional epithelium: Adheres to the implant surface and plays an immunologic role.

- ▪

Connective tissue: Provides mechanical support, vascular supply, and immune defense.

- -

These roles are well-established in basic histology and can be inferred without direct histologic investigation. The structural integrity of peri-implant soft tissue can be assessed through dimensional analysis, as demonstrated in this study.

From this case, two key clinical findings support this hypothesis:

Peri-implant mucositis resolved following CRD optimization.

Peri-implant soft tissue returned to a healthy state, as confirmed through Implant Paper Point Probing (IPPP).

These findings suggest that maintaining CRD within an optimal range may help prevent downward migration of the sulcular epithelium, allowing the underlying connective tissue to remain stable without requiring additional epithelial coverage. This self-sustaining tissue maintains its structural and functional integrity, preventing inflammatory pocket formation and minimizing disease progression.

Conversely, when CRD exceeds the critical range, peri-implant soft tissue stability is compromised. Without sufficient support, connective tissue becomes unsustainable, necessitating compensatory epithelial coverage. This leads to apical migration of the sulcular epithelium, forming deep pockets that facilitate bacterial colonization and inflammation. The inflammatory response, aimed at managing the foreign material, often results in soft tissue swelling, further deepening the pocket and increasing susceptibility to peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis.

This mechanism closely parallels the pathogenesis of periodontitis in natural teeth, where the junctional epithelium converts into pocket epithelium, marking disease progression [

28]. Thus, this study reinforces CRD as a modifiable factor in maintaining peri-implant health and preventing disease progression.

These results challenge the traditional assumption that subcrestally placed implants (SPIs) are inherently prone to deep pocket formation and peri-implant complications. Instead, this study demonstrates that when CRD is maintained within a critical range, SPIs can achieve stable peri-implant soft tissue adaptation—even when a longer and wider peri-implant soft tissue dimension develops beneath the restoration. Furthermore, this broader and more voluminous connective tissue may actually enhance peri-implant soft tissue health due to its intrinsic biological properties, including enhanced vascularization, mechanical support, and immunologic function. This underscores the necessity of meticulous soft tissue management and precision in prosthetic design to ensure long-term implant success.

Additionally, all cases in this study employed an extraoral cementation technique, effectively eliminating excess cement—a well-documented risk factor for peri-implant disease. These findings emphasize the importance of integrating both soft tissue and prosthetic management strategies to optimize peri-implant health and prevent complications.

The only definitive way to demonstrate and validate this hypothesis would be through histologic examination, which is impractical in human patients due to ethical constraints. Instead, insights can be drawn from established histologic studies, supplemented by clinical evidence from X-rays and oral examinations.

5. Histologic Features of the Junctional Epithelium and Connective Tissue

The peri-implant soft tissue comprises two primary components:

Junctional epithelium

Connective tissue

These structures function synergistically to form a biologic seal around implants, mimicking the protective roles observed in natural teeth.

Junctional Epithelium

The junctional epithelium serves as a critical defense barrier, forming the first line of protection against microbial colonization and infection. It also plays a vital role in adapting gingival tissues to implants while contributing to immunologic defense mechanisms [

9].

Key characteristics of the junctional epithelium:

- -

High cell turnover: Comprising 15–30 cell layers, with a maximum average thickness of about 0.5 mm.

- -

Hemidesmosomal adhesion: Hemidesmosomes are present on both the implant-facing and connective tissue-facing surfaces of the epithelium, facilitating adhesion.

- -

Larger intercellular spaces: Compared to oral epithelium, these spaces allow immune cells to traverse the epithelium, enhancing its defensive function.

- -

Endocytosis and decomposition: The epithelium can process and neutralize exogenous factors, contributing to its protective role [

34].

Clinically, the junctional epithelium is indistinguishable from connective tissue, but its presence is often inferred by the absence of bleeding on probing (BOP). Its high turnover rate and ability to facilitate immune cell migration further enhance its protective function. In self-sustained peri-implant soft tissue, the upper portion may include junctional epithelium—even if composed of a single cell layer—distinguishing it from the pathologic sulcular epithelial downgrowth observed in disease progression.

Connective Tissue

Located apical to the junctional epithelium, peri-implant connective tissue is primarily composed of collagen fibers. In natural teeth, this connective tissue is anchored to cementum via dentogingival fibers, providing a mechanical barrier against bacterial invasion. However, dental implants lack this intrinsic fibrous attachment.

Instead, peri-implant connective tissue compensates by forming a functional seal, which is maintained through:

- -

Expansile forces generated by the inherent elasticity of the connective tissue.

- -

Compressive forces exerted against the implant surface and surrounding structures.

These biomechanical interactions ensure the stability and integration of peri-implant soft tissue (

Figure 12). The connective tissue effectively supports the overlying junctional epithelium, playing a critical role in peri-implant soft tissue stability and protecting the underlying crestal bone.

Figure 12.

Illustration of temporary submucosal swelling, demonstrating the resilience and hydraulic pressure within the connective tissue. This phenomenon, observed during prosthesis removal for temporary repair, highlights the structural integrity and adaptability of peri-implant connective tissue, contributing to the sealing effect of the peri-implant soft tissue.

Figure 12.

Illustration of temporary submucosal swelling, demonstrating the resilience and hydraulic pressure within the connective tissue. This phenomenon, observed during prosthesis removal for temporary repair, highlights the structural integrity and adaptability of peri-implant connective tissue, contributing to the sealing effect of the peri-implant soft tissue.

1. New Model for Biologic Width for Implants

The traditional concept of biologic width, originally developed for natural teeth, has been adapted for implants. First introduced by Gargiulo et al. [

35] and expanded by Vacek et al. [

36], it consists of:

- -

Gingival sulcus

- -

Epithelial attachment

- -

Connective tissue attachment

Studies report consistent connective tissue dimensions of approximately 1.07 mm and 0.77 mm. Ivanovski further explored the supra-alveolar transmucosal architecture, identifying similarities and differences between teeth and implants [

37].

Limitations of Traditional Biologic Width Models

Traditional models focus mainly on vertical soft tissue dimensions, overlooking horizontal and oblique components. Some research suggests that factors such as a wide band of keratinized mucosa, adequate mucosal height, and thick tissue phenotype may help reduce inflammation. However, no specific peri-implant mucosal thickness parameters have been directly linked to peri-implant diseases [

38,

39]. This underscores the need for standardized criteria for peri-implant soft tissue assessment and disease prevention.

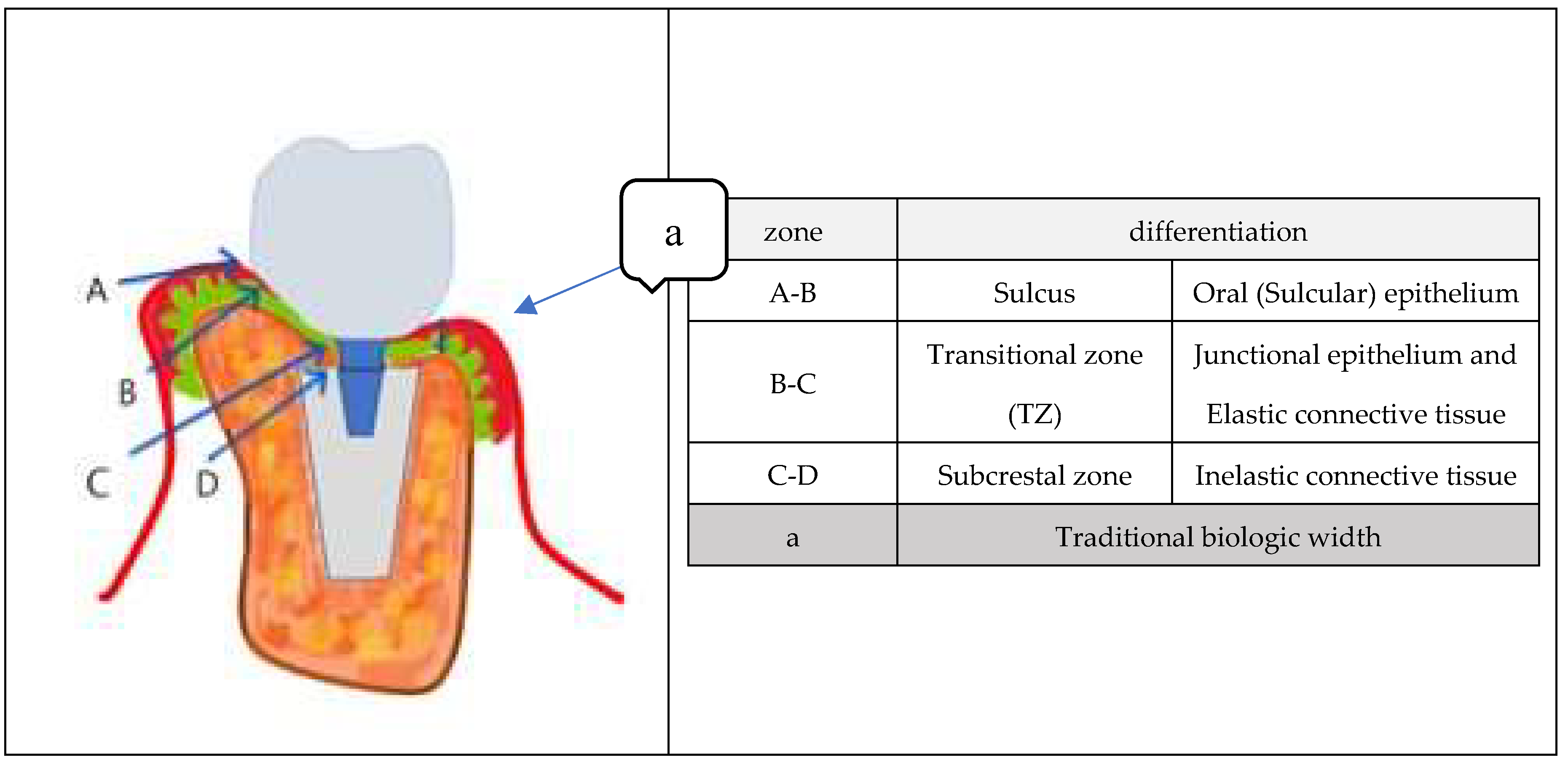

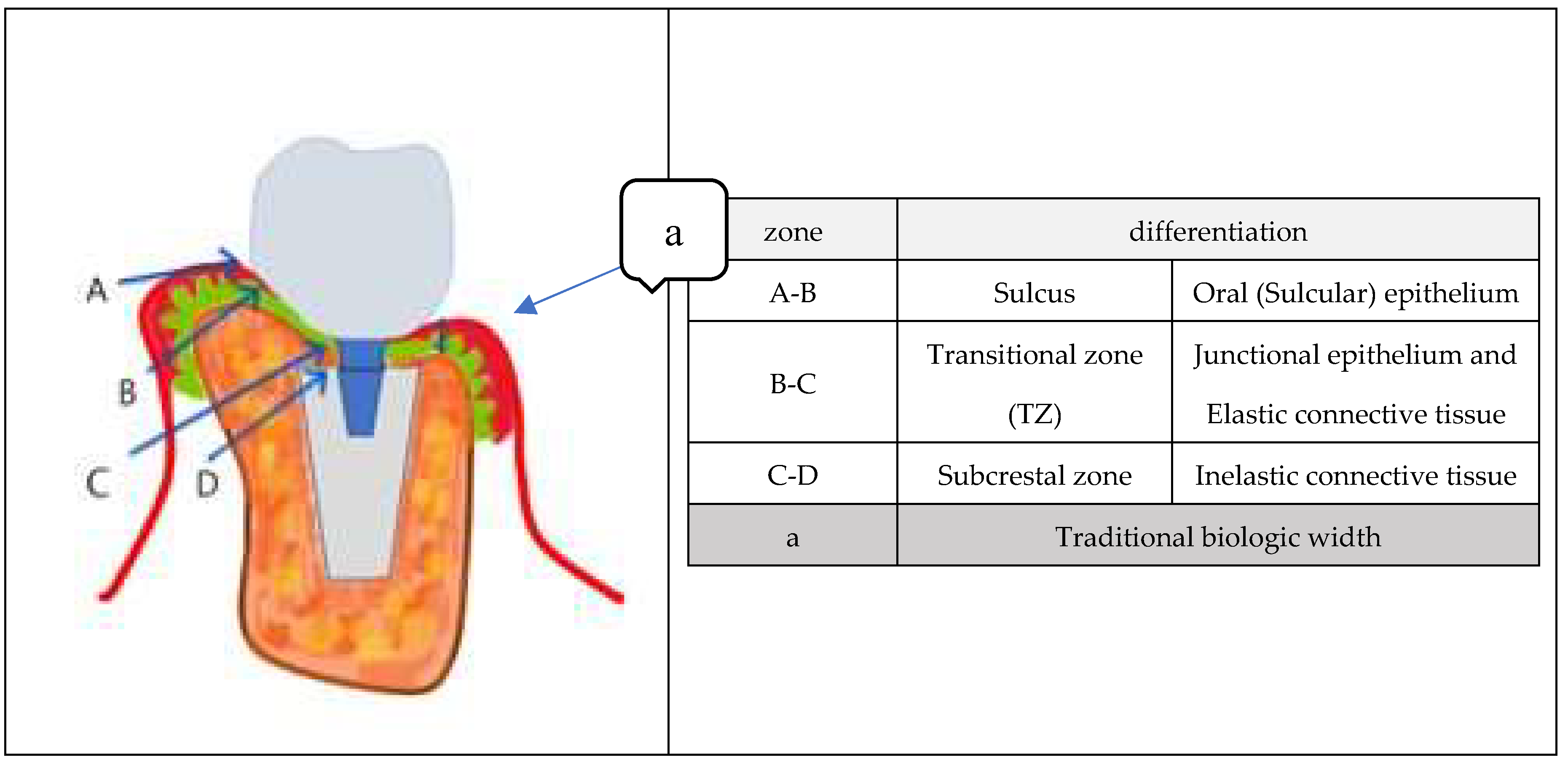

Proposed New Model for Biologic Width

This study introduces a three-zone model for peri-implant soft tissue, which provides a refined perspective on biologic width. The first zone, the Sulcus (A-B), extends from the gingival margin to the Transitional Zone and is primarily composed of oral and sulcular epithelium. This zone serves as the primary defense barrier, protecting the underlying peri-implant structures. Beneath this layer lies the Transitional Zone (TZ) (B-C), which consists of elastic connective tissue and may include junctional epithelium. The TZ adapts to the contours of the implant restoration, stabilizing the surrounding soft tissue while maintaining a functional biological seal that ensures close contact with the implant surface. The third zone, the Subcrestal Zone (SZ) (C-D), is specifically relevant to subcrestally placed implants. This zone comprises inelastic connective tissue that directly interfaces with the crestal bone, providing mechanical support and contributing to the long-term stability of the implant. The prominence of the Subcrestal Zone is particularly notable in tissue-level implants with matching abutment techniques [

40], highlighting its role in ensuring optimal peri-implant health and integration.

\

Figure 13.

illustrates a schematic representation of submucosal peri-implant soft tissue, distinguishing three distinct zones: the Sulcus (A-B), the Transitional Zone (TZ) (B-C), and the Subcrestal Zone (SZ) (C-D). The Sulcus represents the outermost layer, extending from the gingival margin to the Transitional Zone, forming the visible interface between the implant restoration and the oral cavity. The Transitional Zone, located beneath the Sulcus, serves as an adaptive region where connective tissue stabilizes around the implant restoration while maintaining some epithelial characteristics. This zone plays a crucial role in ensuring a functional biological seal. The Subcrestal Zone, positioned closest to the crestal bone, consists entirely of inelastic connective tissue, providing mechanical support and long-term stability. This schematic model integrates real X-ray images and illustrations to enhance the visualization of peri-implant soft tissue structure. By emphasizing the configurations of the Transitional Zone and Subcrestal Zone, the model highlights their clinical significance in implant success. Additionally, traditional biologic width (A-E) is incorporated for comparative analysis.

Figure 13.

illustrates a schematic representation of submucosal peri-implant soft tissue, distinguishing three distinct zones: the Sulcus (A-B), the Transitional Zone (TZ) (B-C), and the Subcrestal Zone (SZ) (C-D). The Sulcus represents the outermost layer, extending from the gingival margin to the Transitional Zone, forming the visible interface between the implant restoration and the oral cavity. The Transitional Zone, located beneath the Sulcus, serves as an adaptive region where connective tissue stabilizes around the implant restoration while maintaining some epithelial characteristics. This zone plays a crucial role in ensuring a functional biological seal. The Subcrestal Zone, positioned closest to the crestal bone, consists entirely of inelastic connective tissue, providing mechanical support and long-term stability. This schematic model integrates real X-ray images and illustrations to enhance the visualization of peri-implant soft tissue structure. By emphasizing the configurations of the Transitional Zone and Subcrestal Zone, the model highlights their clinical significance in implant success. Additionally, traditional biologic width (A-E) is incorporated for comparative analysis.

Conclusions

In this case, peri-implant mucositis was resolved by modifying the implant restoration to optimize Crest to Restoration Distance (CRD). The difference in CRD between the upper left and lower right implants suggests that CRD may play a role in peri-implant soft tissue stability.

While this observation led to the proposal of a new model emphasizing the transitional zone in subcrestally placed implants (SPIs), this remains a hypothesis. Further studies with larger patient cohorts are needed to validate these findings and refine our understanding of peri-implant soft tissue dynamics.

A systematic approach to CRD assessment, along with comprehensive clinical and histologic evaluations, may help establish evidence-based guidelines for optimizing implant outcomes.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Statement

This study is a retrospective clinical report conducted independently at a private dental clinic. As it does not involve any experimental procedures or interventions beyond routine clinical practice, the need for formal ethical approval by any ethical committee was deemed unnecessary. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for the use of their clinical data and images for research and publication purposes.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data and materials used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent for the publication of clinical images and case details was obtained from the patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Full Description |

| SPI |

Subcrestally Placed Implant |

| STT |

Soft Tissue Thickness |

| CRD |

Crest to Restoration Distance |

| cCRD |

Central Crest to Restoration Distance |

| pCRD |

Peripheral Crest to Restoration Distance |

| DP |

Depth of Placement |

| cDP |

Central Depth of Placement |

| pDP |

Peripheral Depth of Placement |

| SZ |

Subcrestal Zone |

| TZ |

Transitional Zone |

| CBCT |

Cone Beam Computed Tomography |

| PPD |

Probing Pocket Depth |

| BOP |

Bleeding on Probing |

| SOP |

Suppuration on Probing |

| IPPP |

Implant Paper Point Probing |

| CAC |

Crown-Abutment Complex |

| 3DSTA |

3-Dimensional Soft Tissue Analysis |

| Ep |

Epi-Crestal |

| STL |

Standard Tessellation Language (used for 3D modeling and digital impressions) |

| STH |

Supracrestal Tissue Height |

References

- Gomez-Meda, R.; Esquivel, J.; Blatz, M.B. The esthetic biological contour concept for implant restoration emergence profile design. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adell, R.; Lekholm, U.; Rockler, B.; Brånemark, P.I. A 15-year study of osseointegrated implants in the treatment of the edentulous jaw. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1981, 10, 387–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, D.; Sennerby, L.; De Bruyn, H. Modern implant dentistry based on osseointegration: 50 years of progress, current trends, and open questions. Periodontol 2000 2017, 73, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunrath, M.F.; Gerhardt, M.N. Trans-mucosal platforms for dental implants: Strategies to induce muco-integration and shield peri-implant diseases. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.N.; Badran, Z.; Ciobanu, O.; Hamdan, N.; Tamimi, F. Strategies for optimizing the soft tissue seal around osseointegrated implants. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Ao, X.; Xie, P.; Jiang, F.; Chen, W. The biological width around implants. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monje, A.; González-Martín, O.; Ávila-Ortiz, G. Impact of peri-implant soft tissue characteristics on health and esthetics. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 35, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Ortiz, G.; González-Martín, O.; Couso-Queiruga, E.; Wang, H.L. The peri-implant phenotype. J. Periodontol. 2020, 91, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, S.; Roffel, S.; Meyer, M.; Gasser, A. Biology of soft tissue repair: Gingival epithelium in wound healing and attachment to the tooth and abutment surface. Eur. Cell Mater. 2019, 38, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aellos, F.; Grauer, J.A.; Harder, K.G.; et al. Dynamic analyses of a soft tissue-implant interface: Biological responses to immediate versus delayed dental implants. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Kinane, D.F.; Lindhe, J.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology of the European Academy of Periodontology at the Charterhouse at Ittingen, Thurgau, Switzerland. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35 (Suppl. 8), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Chapple, I.L. Clinical research on peri-implant diseases: Consensus report of Working Group 4. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39 (Suppl. 12), 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of Workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 (Suppl. 1), S173–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkevicius, T.; Apse, P.; Grybauskas, S.; Puisys, A. The influence of soft tissue thickness on crestal bone changes around implants: A 1-year prospective controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2009, 24, 712–719. [Google Scholar]

- Al Rezk, F.; Trimpou, G.; Lauer, H.C.; Weigl, P.; Krockow, N. Response of soft tissue to different abutment materials with different surface topographies: A review of the literature. Gen. Dent. 2018, 66, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. Surface modification strategies to reinforce the soft tissue seal at the transmucosal region of dental implants. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 42, 404–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rompen, E.; Domken, O.; Degidi, M.; Farias Pontes, A.E.; Piattelli, A. The effect of material characteristics, surface topography, and implant components and connections on soft tissue integration: A literature review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2006, 17 (Suppl. 2), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baus-Domínguez, M.; Oliva-Ferrusola, E.; Maza-Solano, S.; et al. Biological response of the peri-implant mucosa to different definitive implant rehabilitation materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martín, O.; Lee, E.; Weisgold, A.; Veltri, M.; Su, H. Contour management of implant restorations for optimal emergence profiles: Guidelines for immediate and delayed provisional restorations. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2020, 40, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.T.; Lin, G.H.; Wang, H.L. Effects of platform-switching on peri-implant soft and hard tissue outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2017, 32, e9–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, J.; Gomez Meda, R.; Blatz, M.B. The impact of 3D implant position on emergence profile design. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2021, 41, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios-Garzón, N.; Velasco-Ortega, E.; López-López, J. Bone loss in implants placed at subcrestal and crestal level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Materials 2019, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervaeke, S.; Dierens, M.; Besseler, J.; De Bruyn, H. The influence of initial soft tissue thickness on peri-implant bone remodeling. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2014, 16, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolantoni, G.; Tatullo, M.; Miniello, A.; Sammartino, G.; Marenzi, G. Influence of crestal and subcrestal implant position on development of peri-implant diseases: A 5-year retrospective analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 28, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Huang, B. Clinical and radiographic results of crestal vs. subcrestal placement of implants in posterior areas: A split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2023, 25, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, C.; Rodríguez-Ciurana, X.; Clementini, M.; et al. Influence of subcrestal implant placement compared with equicrestal position on the peri-implant hard and soft tissues around platform-switched implants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.C.; Barootchi, S.; Tavelli, L.; Wang, H.L. The peri-implant phenotype and implant esthetic complications: Contemporary overview. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosshardt, D.D. The periodontal pocket: Pathogenesis, histopathology, and consequences. Periodontol 2000 2018, 76, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, A.; Amerio, E.; Farina, R.; et al. Significance of probing for monitoring peri-implant diseases. Int. J. Oral Implantol. (Berl.) 2021, 14, 385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, N.G.; Aparicio, C. Junctional epithelium and hemidesmosomes: Tape and rivets for solving the “percutaneous device dilemma” in dental and other permanent implants. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T.; Lindhe, J. Dimension of the peri-implant mucosa: Biological width revisited. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 971–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahamsson, I.; Soldini, C. Probe penetration in periodontal and peri-implant tissues: An experimental study in the beagle dog. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2006, 17, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barendregt, D.S.; Van der Velden, U.; Timmerman, M.F.; Van der Weijden, G.A. Comparison of two automated periodontal probes and two probes with a conventional readout in periodontal maintenance patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsuta, I.; Ayukawa, Y.; Kondo, R.; et al. Soft tissue sealing around dental implants based on histological interpretation. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2016, 60, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, A.W.; Arrocha, R. Histo-clinical evaluation of free gingival grafts. Periodontics 1967, 5, 285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Vacek, J.S.; Gher, M.E.; Assad, D.A.; Richardson, A.C.; Giambarresi, L.I. The dimensions of the human dentogingival junction. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 1994, 14, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovski, S.; Lee, R. Comparison of peri-implant and periodontal marginal soft tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000 2018, 76, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.H.; Madi, I.M. Soft-tissue conditions around dental implants: A literature review. Implant Dent. 2019, 28, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchigami, K.; Munakata, M.; Kitazume, T.; et al. A diversity of peri-implant mucosal thickness by site. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2017, 28, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, C. 3-Dimensional soft tissue analysis (3DSTA) of subcrestally placed implants: Relating biologic stability with morphologic achievements. Preprints 2024, Version 1, Received April 15, 2024; Approved April 17, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).