1. Introduction

With the development of new technologies edentulous patients have had the possibility to access to implant surgery protocols that include fixed protheses on implants that are positionated in alveolar bone according to bone quality and quantity of the patients, risks of peri implantitis and osseointegration process [

1,

2,

3]. The original protocol of osseointegrated implantology involved implant placement in totally edentulous patients. [

4,

5]. Technological progress has also affected implant surgery with development of new methods and techniques leading to computer-guided procedures, to program the treatment that differentiate for implant numbers, sites, loading times and prosthetics structures [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Brånemark studied the full-arch rehabilitation and stated that the implants in the anterior area of the bone should be parallel to each other, that supported a full-arch prosthetic rehabilitation and 5 implants should be located in the lower jaw and 6 in the upper jaw. With this method the survival rate was up to 90% after 10 years. Then Branemark et al. compared in another study the difference between 4 and 6 implants in a full arch rehabilitation [

10]. In this retrospective analysis 156 patients were recruited and after 10 years there was no difference in terms of biomechanics. Predictability rehabilitations with a reduced number of implants in cases of totally edentulous patients have been studied, defining that a small number of implants were better in terms of oral hygiene and bone fit because there is a greater distance between them [

11,

12,

13].

In edentulous patients it is important to state the bone quality, especially in the posterior sectors and the anamnesis of the patient is fundamental in case of systemic disease or smoking habits because all these conditions are often not compatible with the implant insertion [

14,

15,

16] (aggiungi articolo lenalidomide). Therefore, in cases of insufficient bone volume, bone augmentation techniques are used. These help to maintain implant stability, improving the biomechanics of the implants in terms of occlusal force distribution with increased predictability of survival and success rate, but this method has disadvantages such as increasing working time, cost and in some cases biological complications associated with the use of certain types of materials [

17,

18,

19]. The concept of intentionally tilted implants has been proposed as an alternative method [

20,

21,

22]. This procedure can help to reduce cantilevers of the overlying prostheses and improve a better distribution of implants in the arch [

23]. With the aim of reducing the cantilever of distal rehabilitation this protocol is proposed in cases of completely edentulous posterior sectors in both the upper and lower jaw. [

24]. Specifically, the result attempted is achieved by the use of four implants placed between the two mental foramen at the lower arch and four implants placed between the two anterior walls of the maxillary sinuses at the upper arch. Of these, the two most distal implants are tilted distally to the occlusal plane. With this technique it is necessary to make an implant-supported fixed protheses with distal cantilevers, increasing the stress on peri-implant bone, because of the absence of implants distally to the noble anatomical structures [

25]. Indeed peri-implant bone is an area of great bone turnover and an area of great attention by the clinician, as it is most susceptible to the stresses to which the implant system is undergone. Any overloads are concentrated specifically on the peri-implant marginal bone [

26]. The key factor in the reduced adaptability of the implant system under stress may be the absence of the periodontal ligament [

27]. Kim et al. in a review highlighted that this phenomena of major remodeling may occur more frequently when occlusal overload insists at the implant level [

27]. The mandibular bone, as well as all long bones in the human body, undergo an elastic deformation when subjected to functional stress [

28]. The particular biology of lower jaw bone tissue, its anatomical shape and its close relationship with the muscle and ligament tissues of the cervicofacial district, specifically the masticatory muscles, are the main causes of these phenomena [

29]. In addition in edentulous patients the phenomenon, better known as median mandibular flexure, can influence the implant success rate [

30,

31,

32].

Contraction of the inferior head of the lateral pterygoid muscles is one of the main causes of mandibular deformation, particularly active during opening and protrusive movements [

33,

34]. Median mandibular flexion (MMF) causes a great reduction of the mandibular arch and this can lead to peri-implant bone loss, in cases of implant rehabilitations [

32].

Thus, the choice of the number and placement of implants that will support the patient’s prostheses becomes of paramount importance for implant rehabilitation in cases of totally edentulous arches. Described the biomechanical difficulties associated with the implant system and the living, continuously remodeling tissue that accommodates that system, the purpose of this study was to assess, through a retrospective radiographic analysis, any correlation between different types of mandibular full-arch implant-supported rehabilitations and peri-implant bone loss. In particular, a comparison was made between rehabilitations that involved implant placement between the mental foramen and those that also involved implant placement distal to it. It is also important to state the possible association between bone resorption and specific risks related to implant number and position to help clinicians to choose the appropriate full arch mandibular rehabilitation method according to the single case.

The null hypothesis of this study was the absence of significant differences between peri-implant bone loss and implant placement pattern, number of implants and implant position.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective observational analysis was performed on digital panoramic radiographs (OPGs) of 24330 subjects, taken between January 2010 and April 2024. The OPGs were taken in a private dental clinic based in Salerno, Italy, through Orthophos Sirona (Sirona Dental Systems GmbH, Bensheim, Germany) radiographic device use and analyzed through GALILEOS(®) (Sirona Dental Systems GmbH, Bensheim, Germany) imaging viewer software. All the pictures were seen under the same conditions of light and resolution (27 inches 4k Ultrasharp, Dell Inc, Usa). All the files were transferred anonymously.

All the radiographs showed a fixed full arch implant supported mandibular rehabilitation in fully edentulous patients with a minimum follow up of 5 years, up to a maximum of 10 years.

Exclusion criteria:

Full arch rehabilitations with less than 5 years follow-up

Full arch rehabilitations with more than 10 years follow-up

Mandibular rehabilitations with dental implants supporting removable prostheses

Mandibular rehabilitations with dental implants supporting fixed prostheses with horizontal bone resorption

Dental elements in the mandible

OPGs with low resolution quality

Two trained examiners (A.A. and M.G.) with a good level of experience in radiographic evaluation and implantology independently analyzed the OPGs. To guarantee consistency in the evaluation process, the researchers were presented with a randomized assortment of OPGs. The inter-examiner reliability in the data extraction and collection process was assessed using Cohen kappa coefficient. Inter-observer agreement analysis yielded values exceeding 0.90, indicative of substantial concordance. Intra-observer agreement analysis produced values spanning from 0.87 to 0.99, interpreted as representing substantial to almost perfect agreement. The study demonstrated robust inter- and intra-observer reliability, signifying high precision in the measurements obtained for both individual evaluators and repeated measurements by the same evaluator.

The sample was divided into 5 patterns, based on the number of implants inserted and the implants location. The division was based on mandibular rehabilitations supported by 4, 6 or 8 implants placed either between or distal to the two mental foramina.

In particular:

Model 1 was characterized by the presence of the implants at sites 4.5, 4.2, 3.2 and 3.5.

Model 2 was distinguished by the presence of implants at sites 4.6, 4,4, 4.2, 3.2, 3.4 and 3.6.

Model 3 was characterized by the presence of the implants at position 4.6, 4,4, 4.3, 3.3, 3.4 and 3.6.

Model 4 was distinguished by the presence of implants at position 4.7, 4.6, 4,4, 4.2, 3.2, 3.4, 3.6 and 3.7.

Model 5 was characterized by the presence of the implants at sites 4.7, 4.6, 4,4, 4.3, 3.3, 3.4, 3.6 and 3.7.

Bone level measurements in mesial and distal positions were calculated on all OPGs using the Sydexis XG software (Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA). Following calibration using the known implant diameter, the ruler function was used to measure the distance between the implant shoulder and the bone crest mesially and distally to it. The degree of accuracy was 0.05 mm. In case of bone loss related to the length of the implant, a peri implant bone defect was diagnosed. The chosen cut-off was 25% [

35].

2.2. Data collection and statistical analysis

Data obtained from the OPGs were reported on an electronic worksheet of Microsoft Excel software 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Frequencies and percentages were calculated for implant placement models, number and location of implants.

In order to compare frequencies, χ² test was used to evaluate whether peri-implant bone loss was related to the implant placement model, number of implants, and implant position. Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 28.0 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA).

The sample size, calculated using the statistical software G*Power 3.1.9.7, was determined by considering a statistical power of 80% and a significance level α=0.05 as 63 individuals.

3. Results

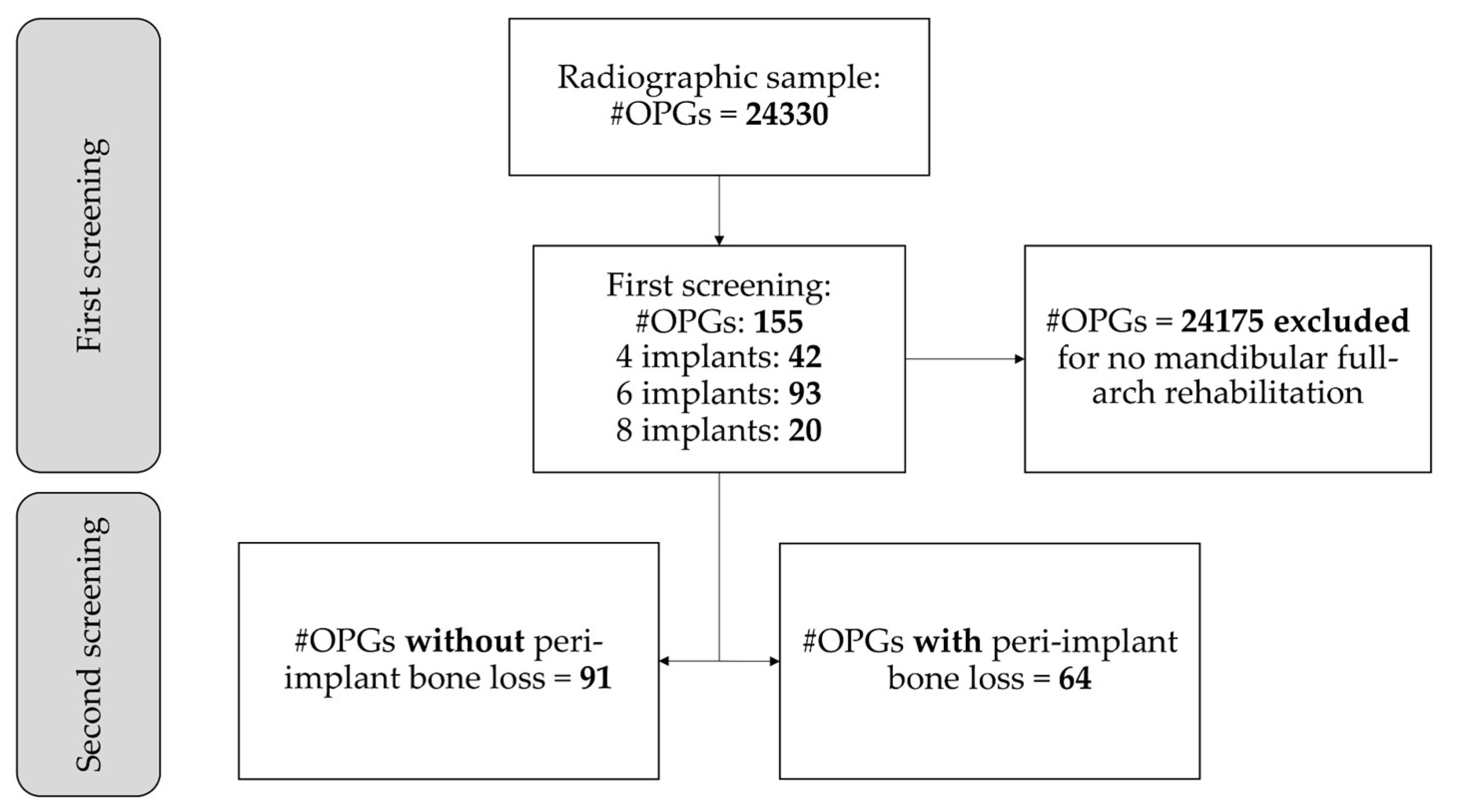

The present study included 155 OPGs that met the eligibility criteria and a peri-implant bone defect was identified in 64 (41.3%) of the 155 OPGs (

Figure 1).

The frequencies and percentages of the implants’ position were shown in

Table 1.

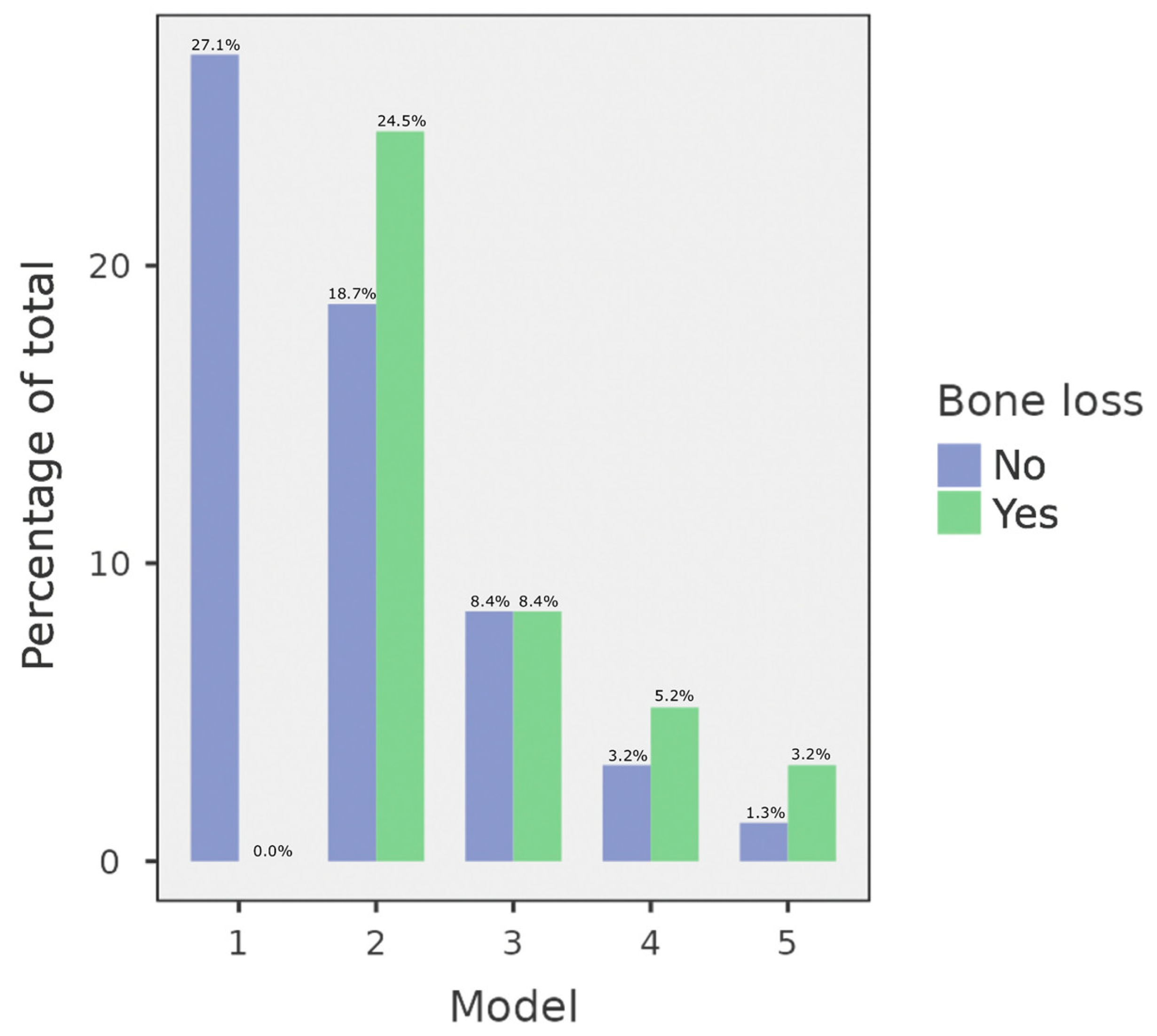

According to implant positioning models, 42 (27.1%) full-arch rehabilitations were performed according to pattern 1, 67 (43.2%) which followed pattern 2, 26 (16.8%) that were positioned according to pattern 3, 13 (8.4%) that followed pattern 4, and 7 (4.5%) which were placed according to pattern 5.

Peri-implant bone loss was detected in 38 (24.5%) OPGs in which implants were placed with pattern 2, 13 (8.4%) in which implants were positioned following pattern 3, 8 (5.2%) that followed pattern 4, 5 (3.2%) which followed pattern 5. The type 1 of the positioning pattern wasn’t associated with peri-implant bone defect.

χ² test found that there was a statistically significant difference between implant placement pattern and peri-implant bone loss (p < 0.001). The distribution of OPGs in relation to implant positioning models and peri-implant bone loss was shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 2.

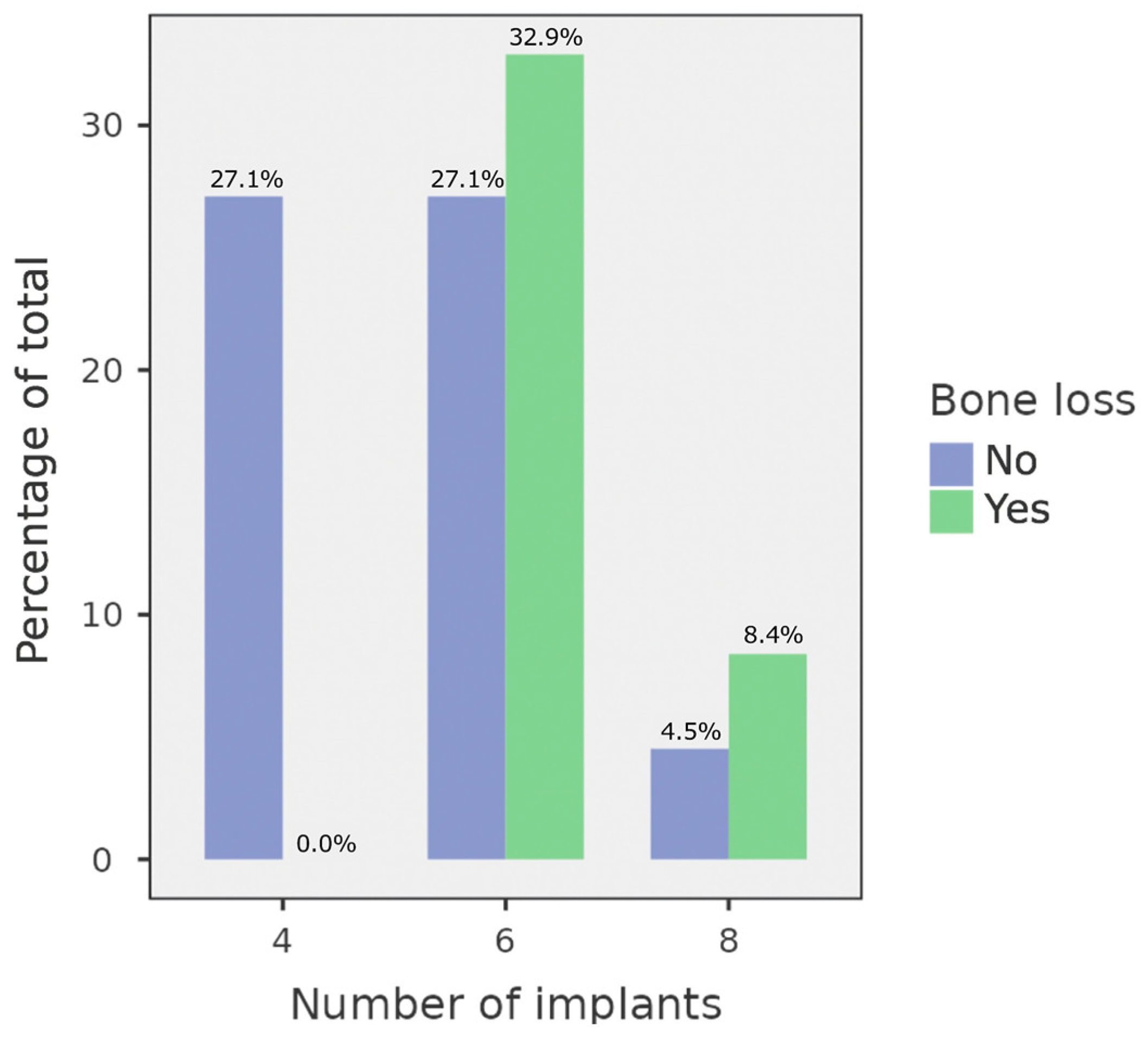

Based on the number of implants, the sample consists of 42 (27.1%) full-arch rehabilitations on 4 dental implants, 93 (60.0%) on 6 dental implants, 20 (12.9%) on 8 dental implants.

No implants presented bone defects in OPGs in which 4 implants were placed, while 51 (32.9%) OPGs in which full-arch rehabilitation included 6 implants and 13 (8.4%) OPGs in which 8 implants exhibited peri-implant bone loss.

A statistically significant difference between the number of implants and peri-implant bone loss was found (p < 0.001) using χ² test. The distribution of OPGs in relation to the number of implants and peri-implant bone loss was displayed in

Figure 3 and

Table 3.

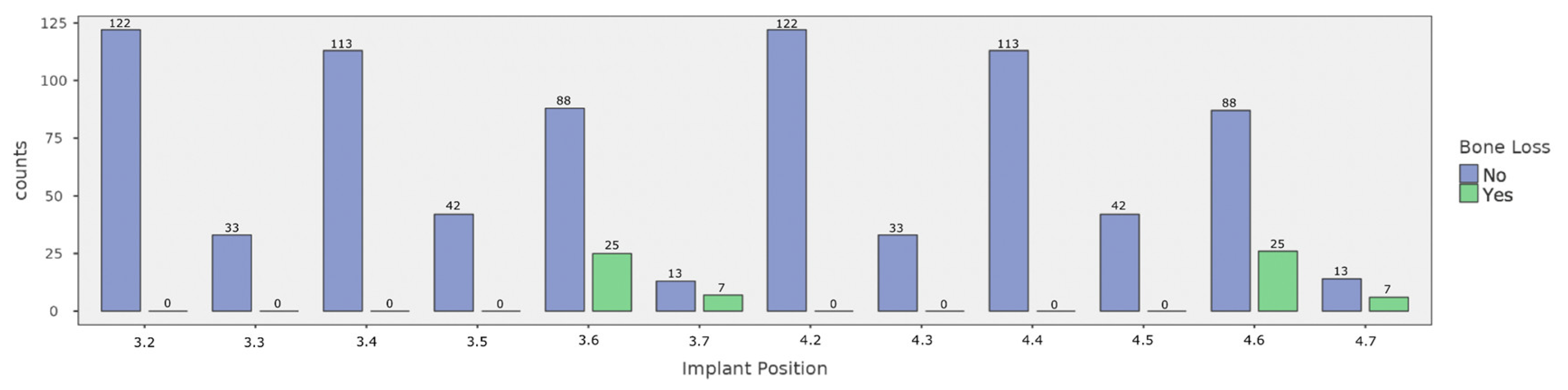

Peri-implant bone loss was predominantly observed in the most distal implant of 2, 3, 4, 5 models. Analyzing implant positions, a total of 64 on 822 implants exhibited peri-implant bone defects. Of these, 25 (2.8%) were positioned in location 3.6, 7 (0.8%) in location 3.7, 26 (2.9%) in location 4.6, and 6 (0.7%) in location 4.7. In particular, χ² test revealed a statistically significant difference between implant position and peri-implant bone deficits (p < 0.001). The detailed distribution of implant positions according to bone loss is presented in

Figure 4 and

Table 4.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study is to detect peri-implant bone loss in full-arch mandibular fixed rehabilitations supported by different number of implants and evaluate potential risk factors associated with the number and location of implants that may have an association with bone defects. In these cases of mandibular rehabilitation, the study shows the prevalence of peri-implant bone loss. 24330 panoramic radiographs (OPGs) were collected from the initial sample but non all the OPGs met the inclusion criteria. The rigorous selection process found 155 OPGs for analysis. The resulting sample was therefore found to be representative and relevant to the research goals. 64 digital radiographs showed peri-implant bone loss involving the implant inserted distal to the mental foramen, interesting outcome to investigate. Infact the results of the study showed greater susceptibility to peri-implant bone defect in implants inserted distal to the mental foramen than those mesial to it in cases of full-arch mandibular rehabilitations. These results continue to raise questions about the potential role that the location and number of implants may have on the long-term success of full-arch mandibular rehabilitation [

35,

36]. Peri-implant bone loss and marginal radio-transparency were identified among the criteria for implant success. In fact, values greater than 1.5 mm during the first 12 months of loading and 0.2 mm for each year thereafter indicate failure of implant rehabilitation [

37]. The new 2018 classification of peri-implant diseases and conditions assigns 2 mm as the limit to diagnose peri-implant disease, however there are different opinions in literature [

38]. This difference in results can be attributed to biomechanical variables, such as loading forces or mandibular flexure, key factors in this area. An association between occlusal overloads and peri-implant crestal bone loss is also described in a systematic review by Di Fiore et al., which in any case requires further studies with reproducible and standardized methods to support this relation more strongly [

39].

In the patterns that included the placement of at least one implant distal to the mental foramen, there was at least 50 percent bone loss, a finding that was found to be statistically significant.

Mandibular flexion had also been identified by Miyamoto et al. as the main cause of implant failure in mandibular full-arch rehabilitation [

40]. In fact especially during opening and protrusion movements, implants connected together in a rigid rehabilitation capable of resisting mandibular flexion were found to be more susceptible to vestibulo-lingual forces [

33,

41].

In the crestal area a stress from the side may affect osseointegration and causes peri-implant bone loss [

42,

43]. Indeed, it has also been described that peri-implant bone loss in overload is possible even in the absence of inflammatory phenomena [

44]. The absence of the periodontal ligament radically changes the response of the implant system to occlusal overloads, with the lack of an adaptation phase, which is instead present in the periodontal system [

45].

Other studies that evaluated the functional loads and deformations caused by mandibular flexure in different types of fixed mandibular rehabilitations also identified the same conclusions. In all described patterns, the more distal implants that supported the prosthetic rehabilitation above were found to be more susceptible to overloads and stresses.

Mijiritsky et al. showed that the area at the level of the crestal module of the distal implants that supported mandibular rehabilitations, mainly in molar region, has peri implant bone stress caused by mandibular flexion, as shown by the results of this study [

46]. It is important to consider also other factors in addition to mandibular flexion, that can enforce this phenomenon in full arch rehabilitations of edentulous jaws to prevent from negatively affecting implant success.

Despite the results in several studies there is no protocol yet describing what is the ideal number of implants for full-arch mandibular rehabilitation. In cases of insufficient hard tissue volumes in the posterior sectors, the All-on-4 technique is described as a potential prosthetic rehabilitative solution. Despite the original indications, based on the results of this analysis, this technique may have further indications for use. In fact, its use could, in any case, avoid the problems associated with placing an implant distal to the mental foramen, especially then in cases where the mandibular flexion mechanism is increased, such as in brachyfacial patients, with increased mandibular length, reduced gonia angle and decreased symphysis bone density, length, and surface area.

The outcomes of this study, the analysis of different implant rehabilitation models in mandibular full-arch cases show statistically significant differences that result in very interesting clinical data that should be taken into account when planning a patient’s rehabilitation. However, further clinical investigations, that go beyond the retrospective nature of the present study, are needed, using the aid of biometric parameters and with the standardization of implant parameters, such as shape or surface morphology and prosthodontic superstructure. With this perspective, stronger data may be available about the effect this and other factors may have on long-term implant success and stability.

5. Conclusions

Study results assess that:

- in mandibular implant rehabilitations there is greater susceptibility to bone resorption of implants placed distal to the mental foramen than mesial ones;

- a key role in long-term implant success may therefore be the number of implants placed and their location;

- the choice of an “all-on-four” implant placement protocol may be a clinical indication for fixed full-arch mandibular rehabilitations, especially in cases where there is an increased susceptibility to the phenomenon of mandibular flexion.

The results of this study make it necessary to investigate the issue further and further prospective clinical and radiographic analysis can be conducted to confirm the results and investigate the possible underlying causes or concomitant causes of these phenomena.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and A.A.; methodology, M.G.; validation, F.G., M.C. and A.A.; formal analysis, F.D.A.; investigation, R.G.; resources, A.A.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, R.G.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, F.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this observational study because our retrospective analysis was conducted through RX OPG examinations

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pantaleo, G.; Acerra, A.; Giordano, F.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Langone, M.; Caggiano, M. Immediate Loading of Fixed Prostheses in Fully Edentulous Jaws: A 7-Year Follow-Up from a Single-Cohort Retrospective Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yafi, F.; Camenisch, B.; Al-Sabbagh, M. Is Digital Guided Implant Surgery Accurate and Reliable? Dent. Clin. North Am. 2019, 63, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.S. Dental Implants: The Last 100 Years. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 76, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brånemark, P.I.; Hansson, B.O.; Adell, R.; Breine, U.; Lindström, J.; Hallén, O.; Ohman, A. Osseointegrated Implants in the Treatment of the Edentulous Jaw. Experience from a 10-Year Period. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Suppl. 1977, 16, 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- Adell, R.; Eriksson, B.; Lekholm, U.; Brånemark, P.I.; Jemt, T. Long-Term Follow-up Study of Osseointegrated Implants in the Treatment of Totally Edentulous Jaws. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1990, 5, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caggiano, M.; Amato, A.; Acerra, A.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Martina, S. Evaluation of Deviations between Computer-Planned Implant Position and In Vivo Placement through 3D-Printed Guide: A CBCT Scan Analysis on Implant Inserted in Esthetic Area. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, M.; Esposito, M.; Zuffetti, F.; Galli, F.; Del Fabbro, M.; Testroi, T. A 5-Year Report from a Multicentre Randomised Clinical Trial: Immediate Non-Occlusal versus Early Loading of Dental Implants in Partially Edentulous Patients. Eur. J. Oral Implantol. 2010, 3, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci, G.O.; Morton, D.; Weber, H.-P. Loading Protocols for Dental Implants in Edentulous Patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2009, 24 Suppl, 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Tahmaseb, A.; Wismeijer, D.; Coucke, W.; Derksen, W. Computer Technology Applications in Surgical Implant Dentistry: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2014, 29 Suppl, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brånemark, P.I.; Svensson, B.; van Steenberghe, D. Ten-Year Survival Rates of Fixed Prostheses on Four or Six Implants Ad Modum Brånemark in Full Edentulism. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 1995, 6, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, L.H.; Kurtzman, G.M. Oral Hygiene and Maintenance of Dental Implants. Dent. Today 2006, 25, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mericske-Stern, R.; Worni, A. Optimal Number of Oral Implants for Fixed Reconstructions: A Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Oral Implantol. 2014, 7 Suppl 2, S133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, T.; Dhaliwal, S.; Naert, I.; Mine, A.; Kronstrom, M.; Sasaki, K.; Duyck, J. Impact of Implant Number, Distribution and Prosthesis Material on Loading on Implants Supporting Fixed Prostheses. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.R.; Gonçalves, A.; Gabrielli, M.A.C.; de Andrade, C.R.; Vieira, E.H.; Pereira-Filho, V.A. Evaluation of Alveolar Bone Quality: Correlation Between Histomorphometric Analysis and Lekholm and Zarb Classification. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, 2114–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumard, B.; Maquer, G.; Heuberger, P.; Zysset, P.K.; Wolfram, U. Peroperative Estimation of Bone Quality and Primary Dental Implant Stability. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 92, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, M.; Amato, A.; Sammartino, P.; Iandolo, A.; Martina, S.; Caggiano, M. Laser Therapy in the Treatment of Peri-Implantitis: State-of-the-Art, Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiano, M.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Giordano, F.; Acerra, A.; Sammartino, P.; Iandolo, A. The “Sling” Technique for Horizontal Guided Bone Regeneration: A Retrospective Case Series. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, F.; D’Ambrosio, F.; acerra, A.; Scognamiglio, B.; Langone, M.; caggiano, M. Bone Gain after Maxillary Sinus Lift: 5-Years Follow-up Evaluation of the Graft Stability. J. Osseointegration 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Dodge, A.; Luepke, P.; Wang, H.-L.; Kapila, Y.; Lin, G.-H. Effect of Membrane Exposure on Guided Bone Regeneration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, C.; Perales, P.; Rangert, B. Tilted Implants as an Alternative to Maxillary Sinus Grafting: A Clinical, Radiologic, and Periotest Study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2001, 3, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DE Vico, G.; Bonino, M.; Spinelli, D.; Schiavetti, R.; Sannino, G.; Pozzi, A.; Ottria, L. Rationale for Tilted Implants: FEA Considerations and Clinical Reports. ORAL Implantol. 2011, 4, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, C.M.; Romeo, D.; Galbusera, F.; Agliardi, E.; Pietrabissa, R.; Zampelis, A.; Francetti, L. A Finite Element Analysis of Tilted versus Nontilted Implant Configurations in the Edentulous Maxilla. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2009, 22, 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. Tilted versus Axially Placed Dental Implants: A Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maló, P.; Rangert, B.; Nobre, M. “All-on-Four” Immediate-Function Concept with Brånemark System Implants for Completely Edentulous Mandibles: A Retrospective Clinical Study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2003, 5 Suppl 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozan, O.; Kurtulmus-Yilmaz, S. Biomechanical Comparison of Different Implant Inclinations and Cantilever Lengths in All-on-4 Treatment Concept by Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2018, 33, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungsiyakull, C.; Rungsiyakull, P.; Li, Q. , Li, W.; & Swain, M. Effects of occlusal inclination and loading on mandibular bone remodeling: a finite element study. The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants. 2011, 26, 527–537. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Oh, T.-J.; Misch, C.E.; Wang, H.-L. Occlusal Considerations in Implant Therapy: Clinical Guidelines with Biomechanical Rationale. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2005, 16, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eijden, T.M. Biomechanics of the Mandible. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Oral Biol. 2000, 11, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, G.N.; Nicholls, J.I. Evaluation of Mandibular Arch Width Change. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1981, 46, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiano, M.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Acerra, A.; Giudice, D.; Giordano, F. Biomechanical Implications of Mandibular Flexion on Implant-Supported Full-Arch Rehabilitations: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, X.; He, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, B. The Effect of Mandibular Flexure on the Design of Implant-Supported Fixed Restorations of Different Facial Types under Two Loading Conditions by Three-Dimensional Finite Element Analysis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 928656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaraman, K.; Chopra, A.; Venkatesh, S.B. Clinical Importance of Median Mandibular Flexure in Oral Rehabilitation: A Review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodkind, R.J.; Heringlake, C.B. Mandibular Flexure in Opening and Closing Movements. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1973, 30, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regli, C.P.; Kelly, E.K. The Phenomenon of Decreased Mandibular Arch Width in Opening Movements. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1967, 17, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiano, M.; Acerra, A.; Gasparro, R.; Galdi, M.; Rapolo, V.; Giordano, F. Peri-Implant Bone Loss in Fixed Full-Arch Implant-Supported Mandibular Rehabilitation: A Retrospective Radiographic Analysis. Osteology 2023, 3, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, E.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, I.; deLlanos-Lanchares, H.; Mauvezin-Quevedo, M.A.; Brizuela-Velasco, A.; Alvarez-Arenal, A. Mandibular Flexure and Peri-Implant Bone Stress Distribution on an Implant-Supported Fixed Full-Arch Mandibular Prosthesis: 3D Finite Element Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8241313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahriari, S.; Parandakh, A.; Khani, M.-M.; Azadikhah, N.; Naraghi, P.; Aeinevand, M.; Nikkhoo, M.; Khojasteh, A. The Effect of Mandibular Flexure on Stress Distribution in the All-on-4 Treated Edentulous Mandible: A Comparative Finite-Element Study Based on Mechanostat Theory. J. Long. Term Eff. Med. Implants 2019, 29, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrektsson, T.; Zarb, G.; Worthington, P.; Eriksson, A.R. The Long-Term Efficacy of Currently Used Dental Implants: A Review and Proposed Criteria of Success. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1986, 1, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Greenwell, H.; Kornman, K.S. Staging and Grading of Periodontitis: Framework and Proposal of a New Classification and Case Definition. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 Suppl 1, S159–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, A.; Montagner, M.; Sivolella, S.; Stellini, E.; Yilmaz, B.; Brunello, G. Peri-Implant Bone Loss and Overload: A Systematic Review Focusing on Occlusal Analysis through Digital and Analogic Methods. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Fujisawa, K.; Takechi, M.; Momota, Y.; Yuasa, T.; Tatehara, S.; Nagayama, M.; Yamauchi, E. Effect of the Additional Installation of Implants in the Posterior Region on the Prognosis of Treatment in the Edentulous Mandibular Jaw. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2003, 14, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulsani, M.; Maiti, S.; Rupawat, D. Evaluation of Change In Mandibular Width During Maximum Mouth Opening and Protrusion. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, F.; Uno, I.; Hata, Y.; Neuendorff, G.; Kirsch, A. Analysis of Stress Distribution in a Screw-Retained Implant Prosthesis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2000, 15, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stacchi, C.; Lamazza, L.; Rapani, A.; Troiano, G.; Messina, M.; Antonelli, A.; Giudice, A.; Lombardi, T. Marginal Bone Changes around Platform-Switched Conical Connection Implants Placed 1 or 2 Mm Subcrestally: A Multicenter Crossover Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2023, 25, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolini, M. M.; Del Bel Cury, A. A.; Pizzoloto, L.; Acapa, I. R. H.; Shibli, J. A.; & Bordin, D.; & Bordin, D. Does traumatic occlusal forces lead to peri-implant bone loss? A systematic review. Braz. Oral Research 2019, 33 (suppl 1), e069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalakis, K. X. , Calvani, P., & Hirayama, H. Biomechanical considerations on tooth-implant supported fixed partial dentures. J. Dental Biomec. 2012; 3, 1758736012462025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijiritsky, E.; Shacham, M.; Meilik, Y.; Dekel-Steinkeller, M. Clinical Influence of Mandibular Flexure on Oral Rehabilitation: Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 16748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).