Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Load Distributing Band (LDB) mechanical chest compression (CC) device is used to treat out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients. Mechanical CCs induce artifacts in the electrocardiogram (ECG) recorded by defibrillators, potentially leading to inaccurate cardiac rhythm analysis. A reliable analysis of the cardiac rhythm is essential for guiding resuscitation treatment and understanding retrospectively patients’ response to treatment. The aim of this study was to design an artificial intelligence (AI)-based framework for cardiac automatic multiclass rhythm classification in the presence of CC artifacts during OHCA. Concretely, an automatic multiclass cardiac rhythm classification is addressed to distinguish the following types of rhythms: shockable rhythms (Sh), asystole (AS) and organized rhythms (OR). A total of 15479 segments (2406 Sh, 5481 AS, 7592 OR) were extracted from 2058 patients during LDB CCs, whereof 9666 were used to train the algorithms and 5813 to assess the performance. The proposed architecture consisted of an adaptive filter for CC artifact suppression and a multiclass rhythm classifier. Three alternatives were considered for the multiclass classifier: a traditional machine learning algorithm and two deep-learning architectures based on convolutional neuronal networks and residual networks (ResNets). The unweighted mean of sensitivities, unweighted mean of bad hbox and the accuracy of the best method (ResNets) were 88.3%, 88.3% and 88.2%, respectively. These results highlight the potential of AI-based methods to provide accurate cardiac rhythm diagnoses without interrupting mechanical CC therapy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials

3. Methods

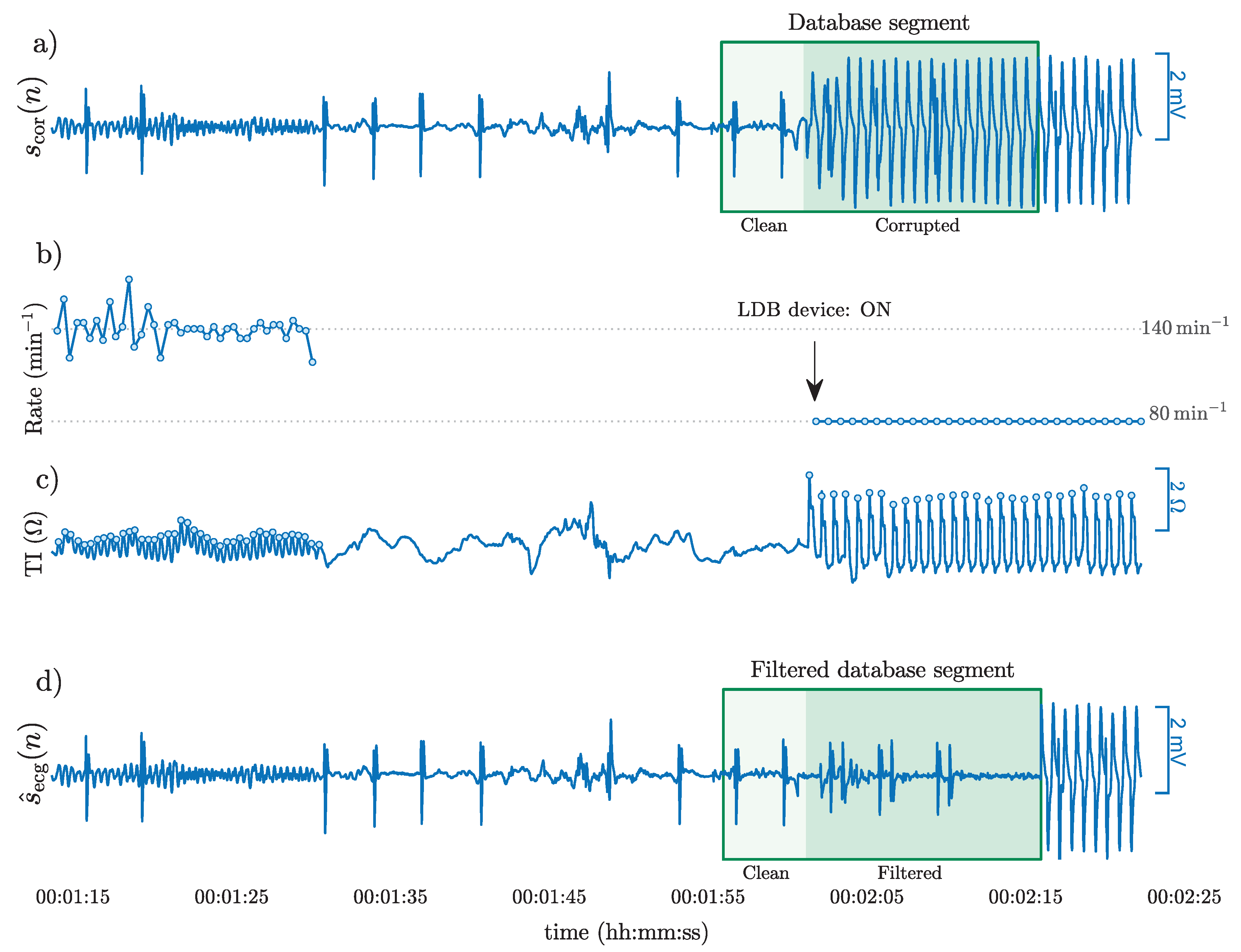

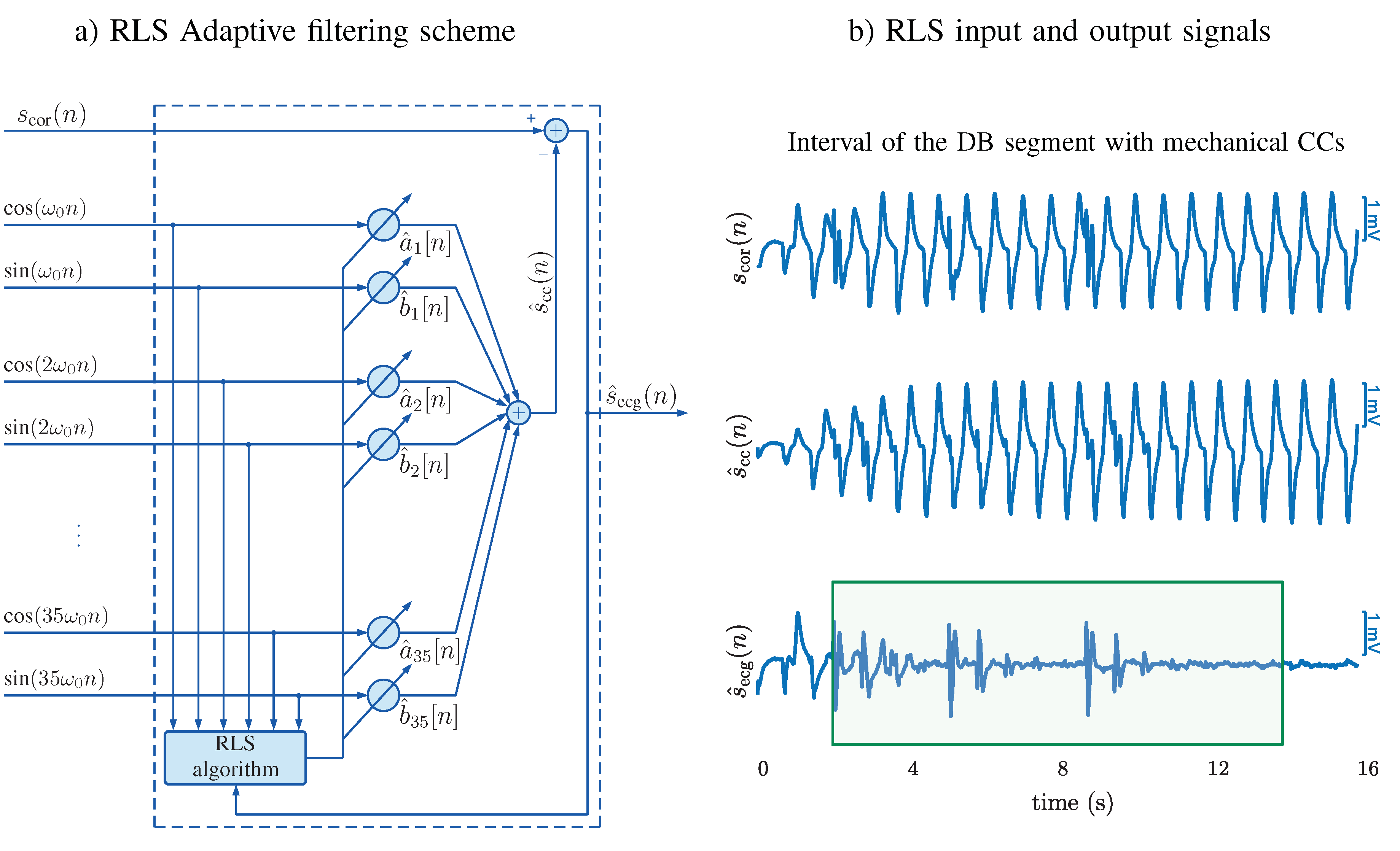

3.1. CPR Artifact Suppressing Filter

3.2. Optimization and Evaluation

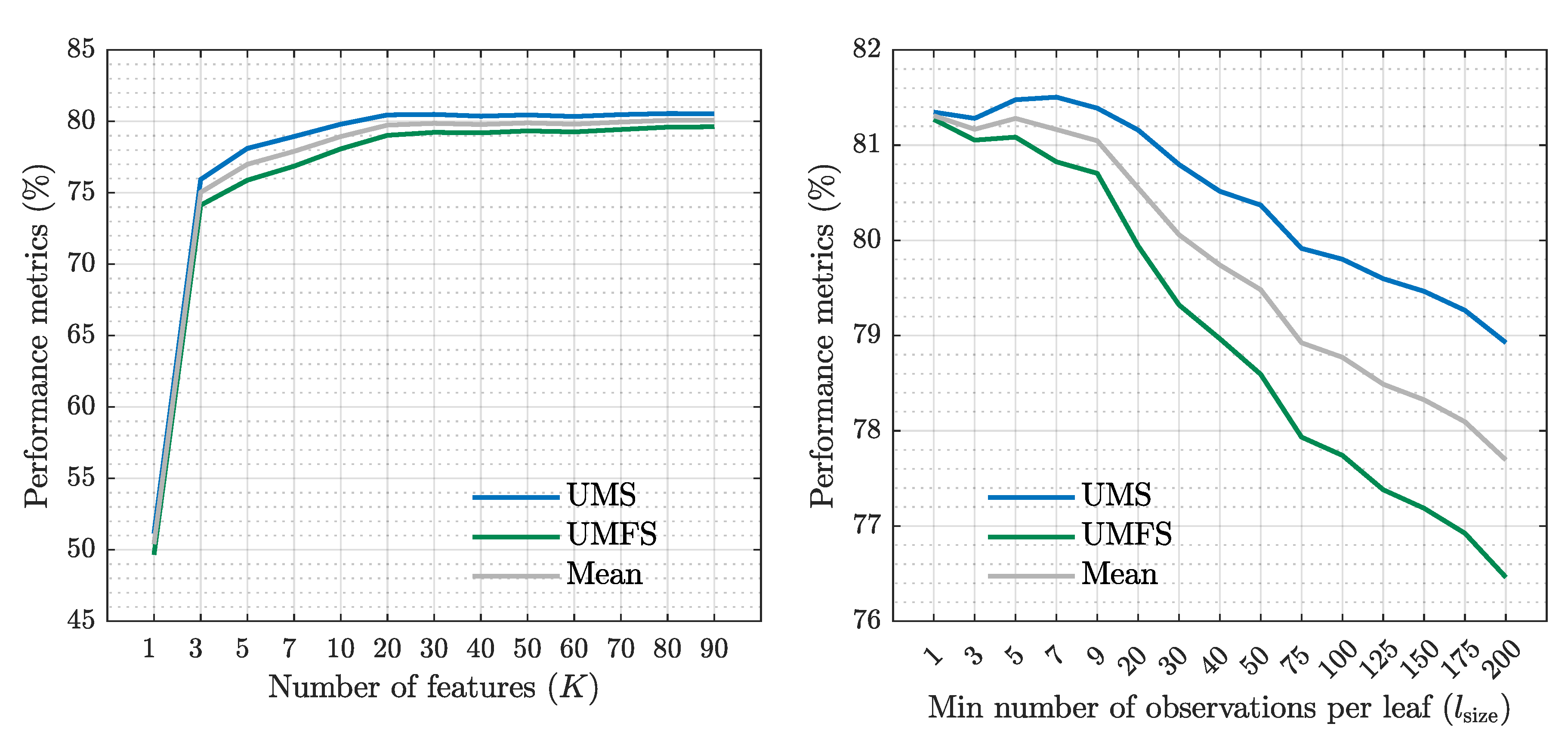

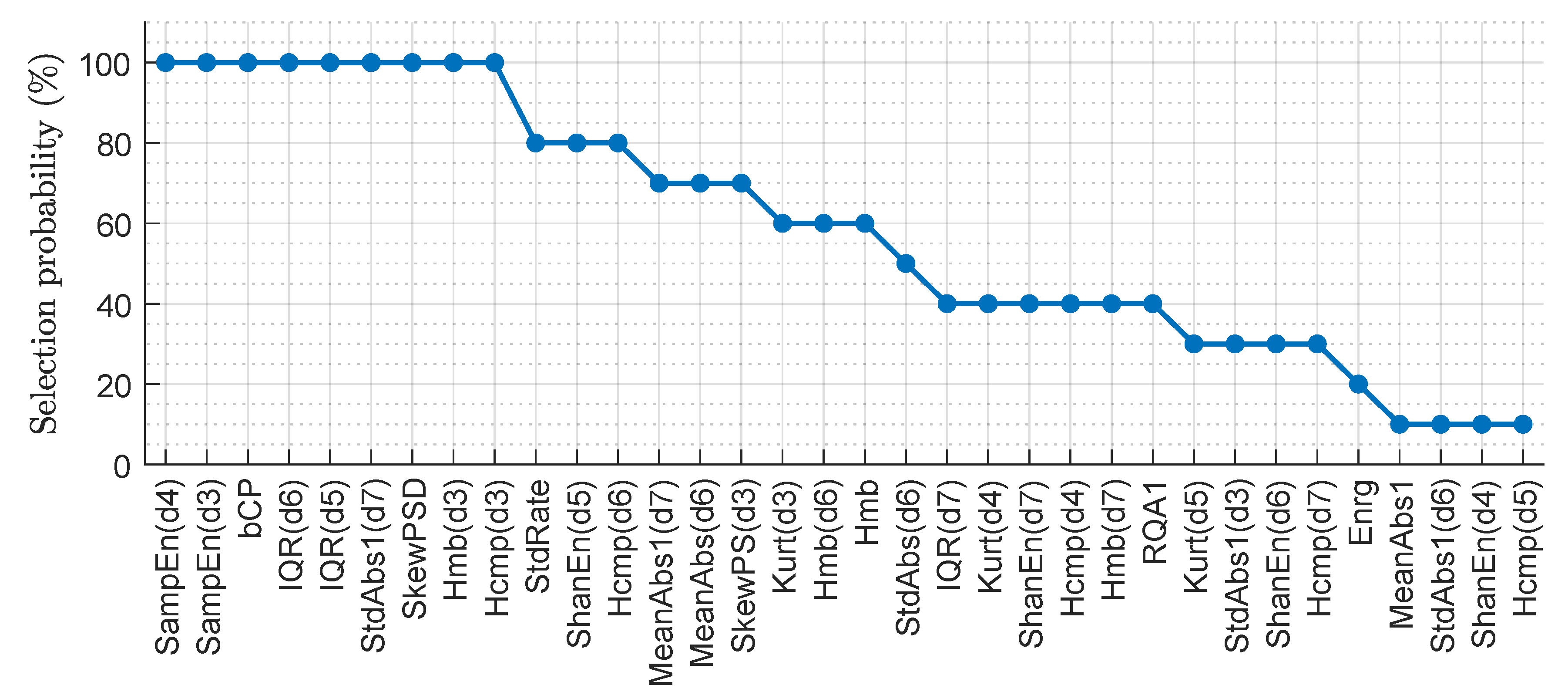

3.3. Classical Machine Learning Architecture

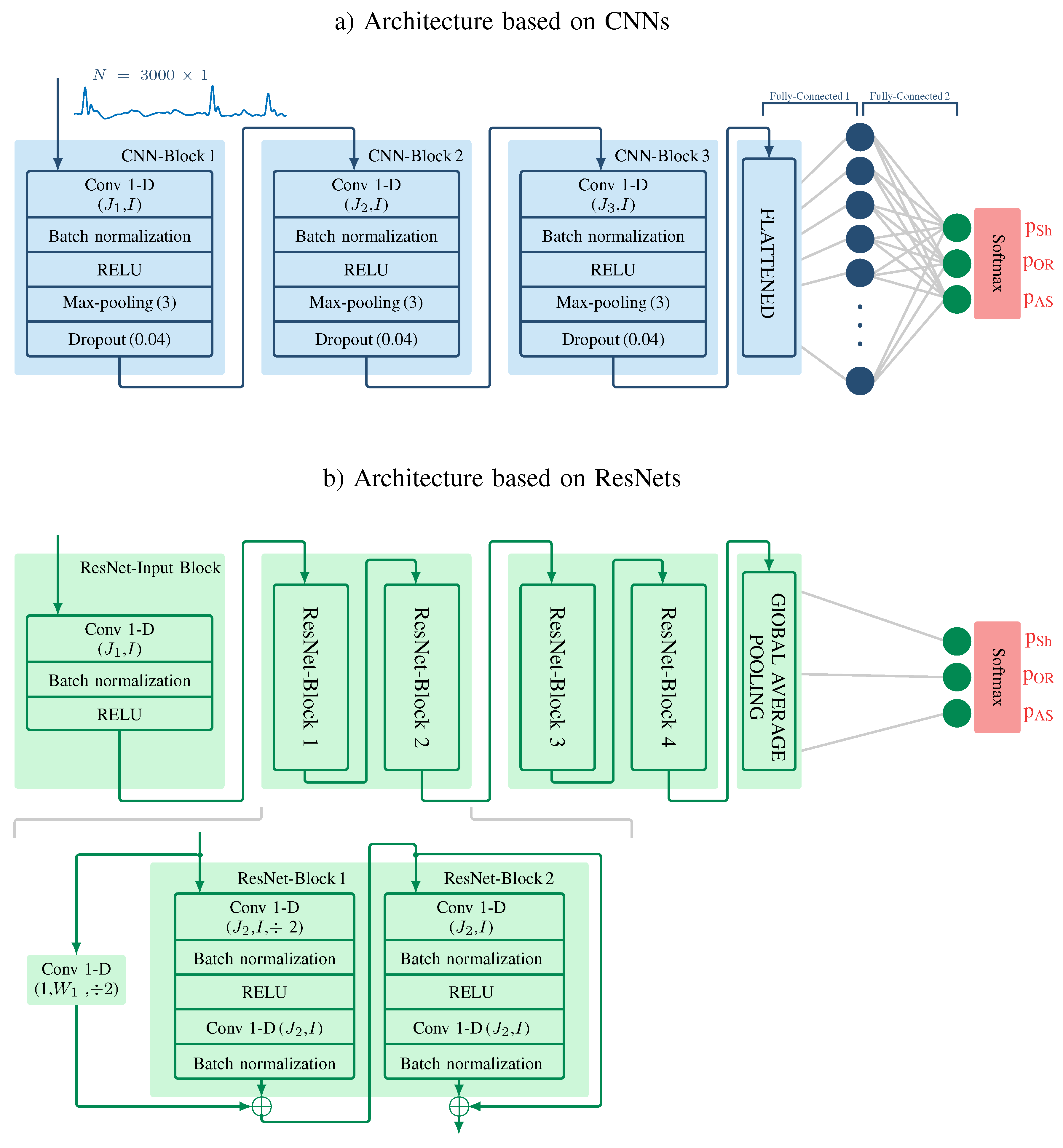

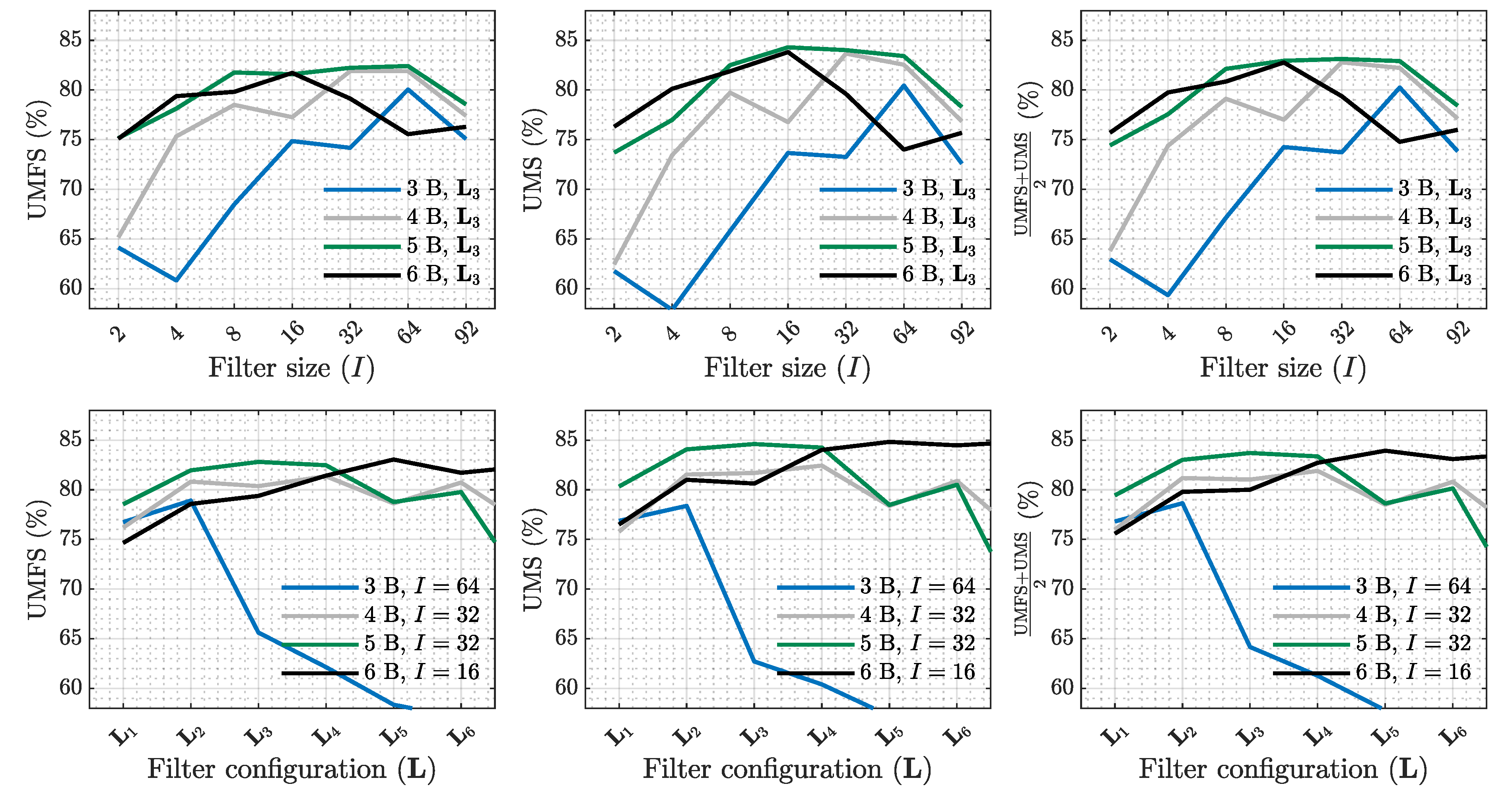

3.4. Algorithm Based on CNNs

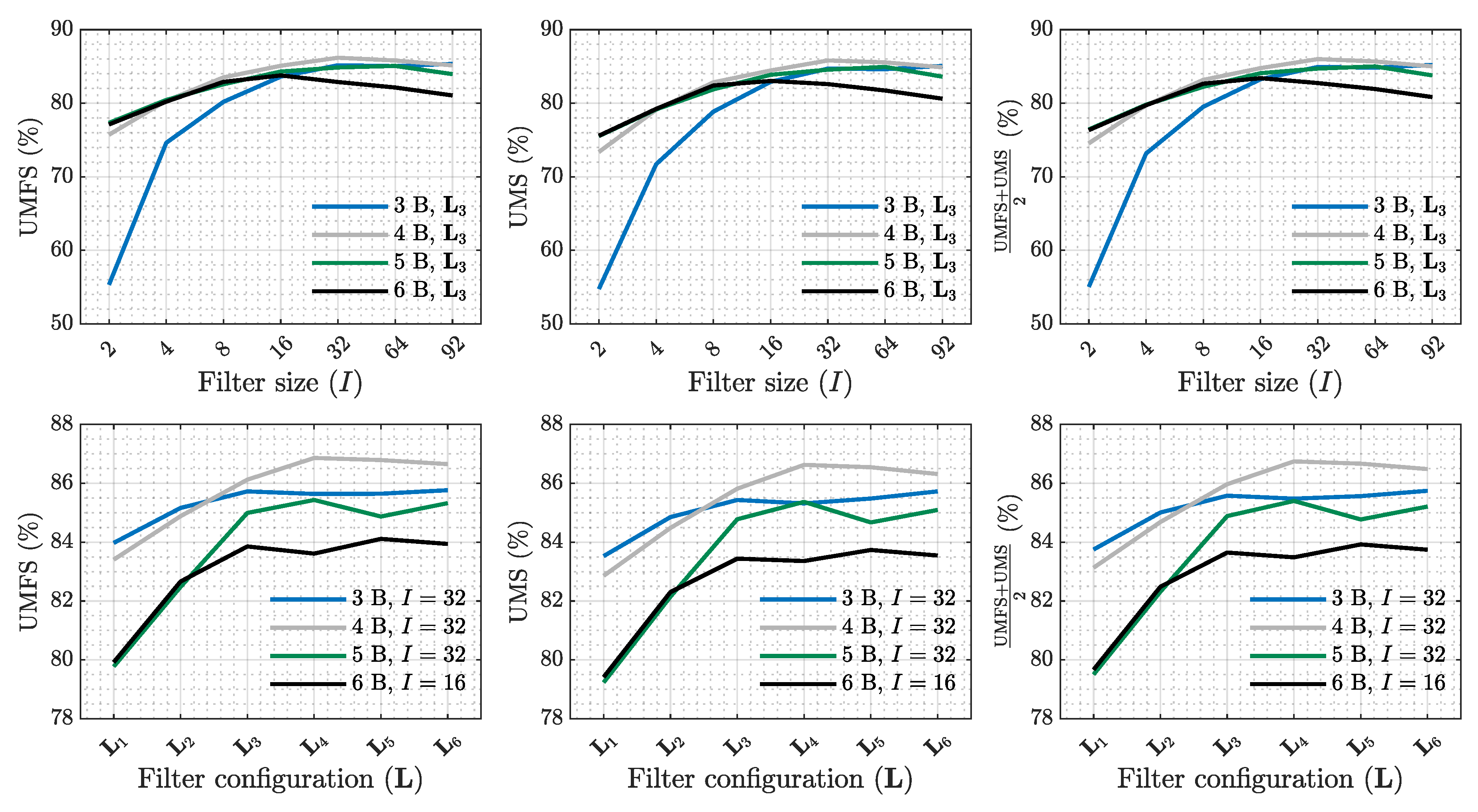

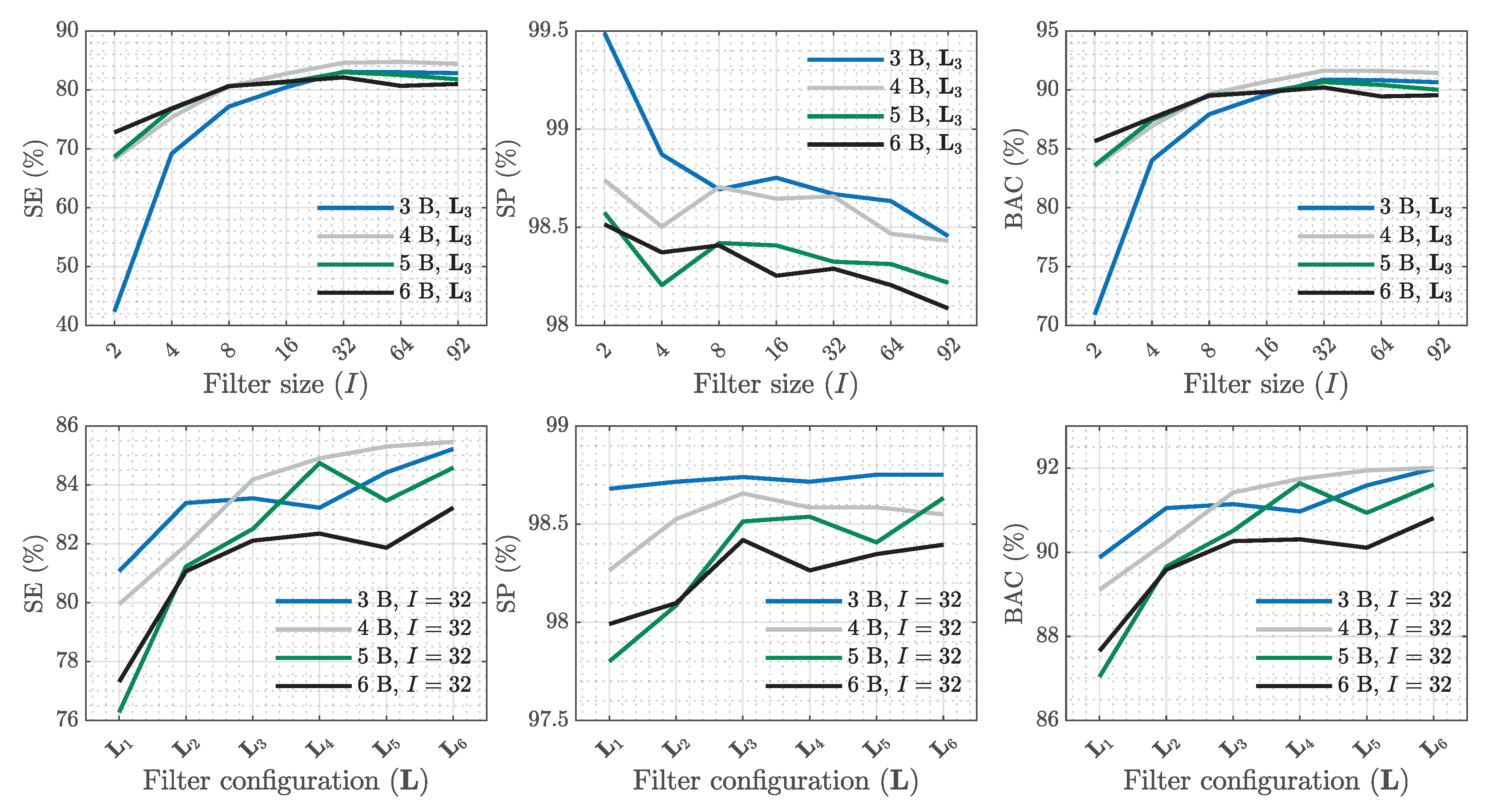

3.5. Algorithm Based on ResNets

4. Results

5. Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- Gräsner, J.T.; Herlitz, J.; Tjelmeland, I.B.; Wnent, J.; Masterson, S.; Lilja, G.; Bein, B.; Böttiger, B.W.; Rosell-Ortiz, F.; Nolan, J.P.; et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: epidemiology of cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soar, J.; Böttiger, B.W.; Carli, P.; Couper, K.; Deakin, C.D.; Djärv, T.; Lott, C.; Olasveengen, T.; Paal, P.; Pellis, T.; et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 115–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olasveengen, T.M.; Semeraro, F.; Ristagno, G.; Castren, M.; Handley, A.; Kuzovlev, A.; Monsieurs, K.G.; Raffay, V.; Smyth, M.; Soar, J.; et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: basic life support. Resuscitation 2021, 161, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gough, C.J.; Nolan, J.P. The role of adrenaline in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Critical Care 2018, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kvaløy, J.T.; Skogvoll, E.; Eftestøl, T.; Gundersen, K.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Olasveengen, T.M.; Steen, P.A. Which factors influence spontaneous state transitions during resuscitation? Resuscitation 2009, 80, 863–869. [Google Scholar]

- Nordseth, T.; Bergum, D.; Edelson, D.P.; Olasveengen, T.M.; Eftestøl, T.; Wiseth, R.; Abella, B.S.; Skogvoll, E. Clinical state transitions during advanced life support (ALS) in in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2013, 84, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Nordseth, T.; Niles, D.E.; Eftestøl, T.; Sutton, R.M.; Irusta, U.; Abella, B.S.; Berg, R.A.; Nadkarni, V.M.; Skogvoll, E. Rhythm characteristics and patterns of change during cardiopulmonary resuscitation for in-hospital paediatric cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2019, 135, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Thakor, N.V.; Zhu, Y.S.; Pan, K.Y. Ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation detection by a sequential hypothesis testing algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 1990, 37, 837–843. [Google Scholar]

- Jekova, I.; Krasteva, V. Real time detection of ventricular fibrillation and tachycardia. Physiological measurement 2004, 25, 1167. [Google Scholar]

- Irusta, U.; Ruiz, J. An algorithm to discriminate supraventricular from ventricular tachycardia in automated external defibrillators valid for adult and paediatric patients. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 1229–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Neurauter, A.; Eftestøl, T.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Abella, B.S.; Sunde, K.; Wenzel, V.; Lindner, K.H.; Eilevstjønn, J.; Myklebust, H.; Steen, P.A.; et al. Prediction of countershock success using single features from multiple ventricular fibrillation frequency bands and feature combinations using neural networks. Resuscitation 2007, 73, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwok, H.; Coult, J.; Drton, M.; Rea, T.D.; Sherman, L. Adaptive rhythm sequencing: A method for dynamic rhythm classification during CPR. Resuscitation 2015, 91, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chicote, B.; Irusta, U.; Alcaraz, R.; Rieta, J.J.; Aramendi, E.; Isasi, I.; Alonso, D.; Ibarguren, K. Application of entropy-based features to predict defibrillation outcome in cardiac arrest. Entropy 2016, 18, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicote, B.; Irusta, U.; Aramendi, E.; Alcaraz, R.; Rieta, J.J.; Isasi, I.; Alonso, D.; Baqueriza, M.d.M.; Ibarguren, K. Fuzzy and sample entropies as predictors of patient survival using short ventricular fibrillation recordings during out of hospital cardiac arrest. Entropy 2018, 20, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, D.; Barro, S.; Salceda, J.; Ruiz, R.; Mira, J. Fuzzy K-nearest neighbor classifiers for ventricular arrhythmia detection. International journal of bio-medical computing 1991, 27, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, A.B.; Eftestøl, T.; Engan, K.; Irusta, U.; Kvaløy, J.T.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Wik, L.; Katsaggelos, A.K. ECG-based classification of resuscitation cardiac rhythms for retrospective data analysis. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 2017, 64, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.; Dong, X. Life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia detection with personalized features. IEEE access 2017, 5, 14195–14203. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Rajagopalan, C.; Clifford, G.D. Ventricular fibrillation and tachycardia classification using a machine learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2013, 61, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, A.B.; Eftestøl, T.; Irusta, U.; Kvaløy, J.T.; Wik, L.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Katsaggelos, A.K.; Engan, K. An automatic system for the comprehensive retrospective analysis of cardiac rhythms in resuscitation episodes. Resuscitation 2018, 122, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Figuera, C.; Irusta, U.; Morgado, E.; Aramendi, E.; Ayala, U.; Wik, L.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Eftestøl, T.; Alonso-Atienza, F. Machine learning techniques for the detection of shockable rhythms in automated external defibrillators. PloS one 2016, 11, e0159654. [Google Scholar]

- Picon, A.; Irusta, U.; Álvarez-Gila, A.; Aramendi, E.; Alonso-Atienza, F.; Figuera, C.; Ayala, U.; Garrote, E.; Wik, L.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; et al. Mixed convolutional and long short-term memory network for the detection of lethal ventricular arrhythmia. PloS one 2019, 14, e0216756. [Google Scholar]

- Hajeb-M, S.; Cascella, A.; Valentine, M.; Chon, K. Deep neural network approach for continuous ECG-based automated external defibrillator shock advisory system during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Journal of the American Heart Association 2021, 10, e019065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jaureguibeitia, X.; Zubia, G.; Irusta, U.; Aramendi, E.; Chicote, B.; Alonso, D.; Larrea, A.; Corcuera, C. Shock decision algorithms for automated external defibrillators based on convolutional networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 154746–154758. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, E.; Aramendi, E.; Daya, M.; Irusta, U.; Chicote, B.; Russell, J.K.; Tereshchenko, L.G. Circulation detection using the electrocardiogram and the thoracic impedance acquired by defibrillation pads. Resuscitation 2016, 99, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Elola, A.; Aramendi, E.; Irusta, U.; Del Ser, J.; Alonso, E.; Daya, M. ECG-based pulse detection during cardiac arrest using random forest classifier. Medical & biological engineering & computing 2019, 57, 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Alwan, Y.; Cvetković, Z.; Curtis, M.J. Methods for improved discrimination between ventricular fibrillation and tachycardia. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2017, 65, 2143–2151. [Google Scholar]

- Cheskes, S.; Schmicker, R.H.; Christenson, J.; Salcido, D.D.; Rea, T.; Powell, J.; Edelson, D.P.; Sell, R.; May, S.; Menegazzi, J.J.; et al. Perishock pause: an independent predictor of survival from out-of-hospital shockable cardiac arrest. Circulation 2011, 124, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz de Gauna, S.; Irusta, U.; Ruiz, J.; Ayala, U.; Aramendi, E.; Eftestøl, T. Rhythm analysis during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: past, present, and future. BioMed research international 2014, 2014, 386010. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, U.; Irusta, U.; Ruiz, J.; Eftestøl, T.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Alonso-Atienza, F.; Alonso, E.; González-Otero, D. A reliable method for rhythm analysis during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. BioMed research international 2014, 2014, 872470. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, I.; Irusta, U.; Aramendi, E.; Eftestøl, T.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Wik, L. Rhythm analysis during cardiopulmonary resuscitation using convolutional neural networks. Entropy 2020, 22, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isasi, I.; Irusta, U.; Rad, A.B.; Aramendi, E.; Zabihi, M.; Eftestøl, T.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Wik, L. Automatic cardiac rhythm classification with concurrent manual chest compressions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 115147–115159. [Google Scholar]

- Wik, L.; Olsen, J.A.; Persse, D.; Sterz, F.; Lozano Jr, M.; Brouwer, M.A.; Westfall, M.; Souders, C.M.; Malzer, R.; van Grunsven, P.M.; Manual, vs.; et al. integrated automatic load-distributing band CPR with equal survival after out of hospital cardiac arrest. The randomized CIRC trial. Resuscitation 2014, 85, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rubertsson, S.; Lindgren, E.; Smekal, D.; Östlund, O.; Silfverstolpe, J.; Lichtveld, R.A.; Boomars, R.; Ahlstedt, B.; Skoog, G.; Kastberg, R.; et al. Mechanical chest compressions and simultaneous defibrillation vs conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the LINC randomized trial. Jama 2014, 311, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krep, H.; Mamier, M.; Breil, M.; Heister, U.; Fischer, M.; Hoeft, A. Out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation with the AutoPulse™ system: A prospective observational study with a new load-distributing band chest compression device. Resuscitation 2007, 73, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, M.E.H.; Mackey, K.E.; Zhang, Z.C.; Tanaka, H.; Ma, M.H.M.; Swor, R.; Shin, S.D. Mechanical CPR devices compared to manual CPR during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and ambulance transport: a systematic review. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine 2012, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Putzer, G.; Braun, P.; Zimmermann, A.; Pedross, F.; Strapazzon, G.; Brugger, H.; Paal, P. LUCAS compared to manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation is more effective during helicopter rescue—a prospective, randomized, cross-over manikin study. The American journal of emergency medicine 2013, 31, 384–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, A.; McCluskey, A.; Gwinnutt, C.; Keenan, A. Effect of rescuer fatigue on performance of continuous external chest compressions over 3 min. Resuscitation 2002, 55, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, I.; Irusta, U.; Elola, A.; Aramendi, E.; Ayala, U.; Alonso, E.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Eftestøl, T. A machine learning shock decision algorithm for use during piston-driven chest compressions. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 2018, 66, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, I.; Irusta, U.; Aramendi, E.; Olsen, J.; Wik, L. Shock decision algorithm for use during load distributing band cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2021, 165, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, I.; Irusta, U.; Aramendi, E.; Ayala, U.; Alonso, E.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Eftestøl, T. A multistage algorithm for ECG rhythm analysis during piston-driven mechanical chest compressions. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2018, 66, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, E.B.; Persse, D.; Souders, C.M.; Sterz, F.; Malzer, R.; Lozano Jr, M.; Westfall, M.; Brouwer, M.A.; van Grunsven, P.M.; Whitehead, A.; et al. Design of the Circulation Improving Resuscitation Care (CIRC) Trial: a new state of the art design for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest research. Resuscitation 2011, 82, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Ma, L.; Ward, R.K. Fast RLS Fourier analyzers capable of accommodating frequency mismatch. Signal Processing 2007, 87, 2197–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irusta, U.; Ruiz, J.; de Gauna, S.R.; Eftestl, T.; Kramer-Johansen, J. A least mean-square filter for the estimation of the cardiopulmonary resuscitation artifact based on the frequency of the compressions. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2009, 56, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuo, S. Computer detection of ventricular fibrillation. Proc. of Computers in Cardiology, IEEE Comupter Society.

- Alonso-Atienza, F.; Morgado, E.; Fernandez-Martinez, L.; Garcia-Alberola, A.; Rojo-Alvarez, J.L. Detection of life-threatening arrhythmias using feature selection and support vector machines. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2013, 61, 832–840. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, H.; George, S.L.; Hui, K.; Tong, T. Gene selection using iterative feature elimination random forests for survival outcomes. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2012, 9, 1422–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.Q.; Ong, C.J.; Li, X.P.; Hui, Z.; Wilder-Smith, E.P. A feature selection method for multilevel mental fatigue EEG classification. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 2007, 54, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests Mach Learn 45 (1): 5–32, 2001.

- Ioffe, S. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03167, arXiv:1502.03167 2015.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp.

- Han, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Deep pyramidal residual networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp.

- Lin, M.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Network in network. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.4400, arXiv:1312.4400 2013.

- Sutskever, I.; Martens, J.; Dahl, G.; Hinton, G. On the importance of initialization and momentum in deep learning. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2013; pp. 1139–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, I.; Irusta, U.; Aramendi, E.; Age, J.; Wik, L. Characterization of the ECG compression artefact caused by the AutoPulse device. Resuscitation 2017, 118, e38. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, I.; Irusta, U.; Aramendi, E.; Ayala, U.; Alonso, E.; Kramer-Johansen, J.; Eftest, T.; et al. Removing piston-driven mechanical chest compression artefacts from the ECG. In Proceedings of the 2017 Computing in Cardiology (CinC). IEEE; 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kerber, R.E.; Becker, L.B.; Bourland, J.D.; Cummins, R.O.; Hallstrom, A.P.; Michos, M.B.; Nichol, G.; Ornato, J.P.; Thies, W.H.; White, R.D.; et al. Automatic external defibrillators for public access defibrillation: recommendations for specifying and reporting arrhythmia analysis algorithm performance, incorporating new waveforms, and enhancing safety: a statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association Task Force on Automatic External Defibrillation, Subcommittee on AED Safety and Efficacy. Circulation 1997, 95, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar]

| SE (%) | PPV (%) | (%) | Sum. metrics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | AS | OR | Sh | AS | OR | Sh | AS | OR | Sh | UMFS | UMS | ACC |

| ML | 80.1 | 85.1 | 90.7 | 76.8 | 87.2 | 90.7 | 78.4 | 86.1 | 90.7 | 85.1 | 85.3 | 83.8 |

| CNN | 84.3 | 84.1 | 94.2 | 78.9 | 91.2 | 85.1 | 81.5 | 87.5 | 89.4 | 86.1 | 87.5 | 85.5 |

| ResNet | 83.8 | 89.2 | 92.0 | 81.0 | 90.1 | 94.1 | 82.4 | 89.6 | 93.0 | 88.3 | 88.3 | 88.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).