Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Nodule Sample Collection

2.2. Rhizobial Isolation

2.3. Authentication of Rhizobial Isolates

2.4. Characterization of Rhizobial Isolates

2.5. Leaf Gas-Exchange Studies

2.6. Relative Symbiotic Effectiveness of Rhizobial Isolates

2.7. Shoot 15N/14N and 13C/12C Isotopic Analysis

2.8. Physiological Characterization of Isolates

2.8.1. Temperature Tolerance

2.8.2. Drought Tolerance

2.8.3. Salinity Tolerance

2.8.5. Acid-Alkali Production

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Gas-Exchange Parameters

3.2. Plant Growth

3.3. Shoot C Concentration

3.4. Shoot δ13C and C:N Ratio

3.5. Nodulation Induced by Rhizobial Isolates

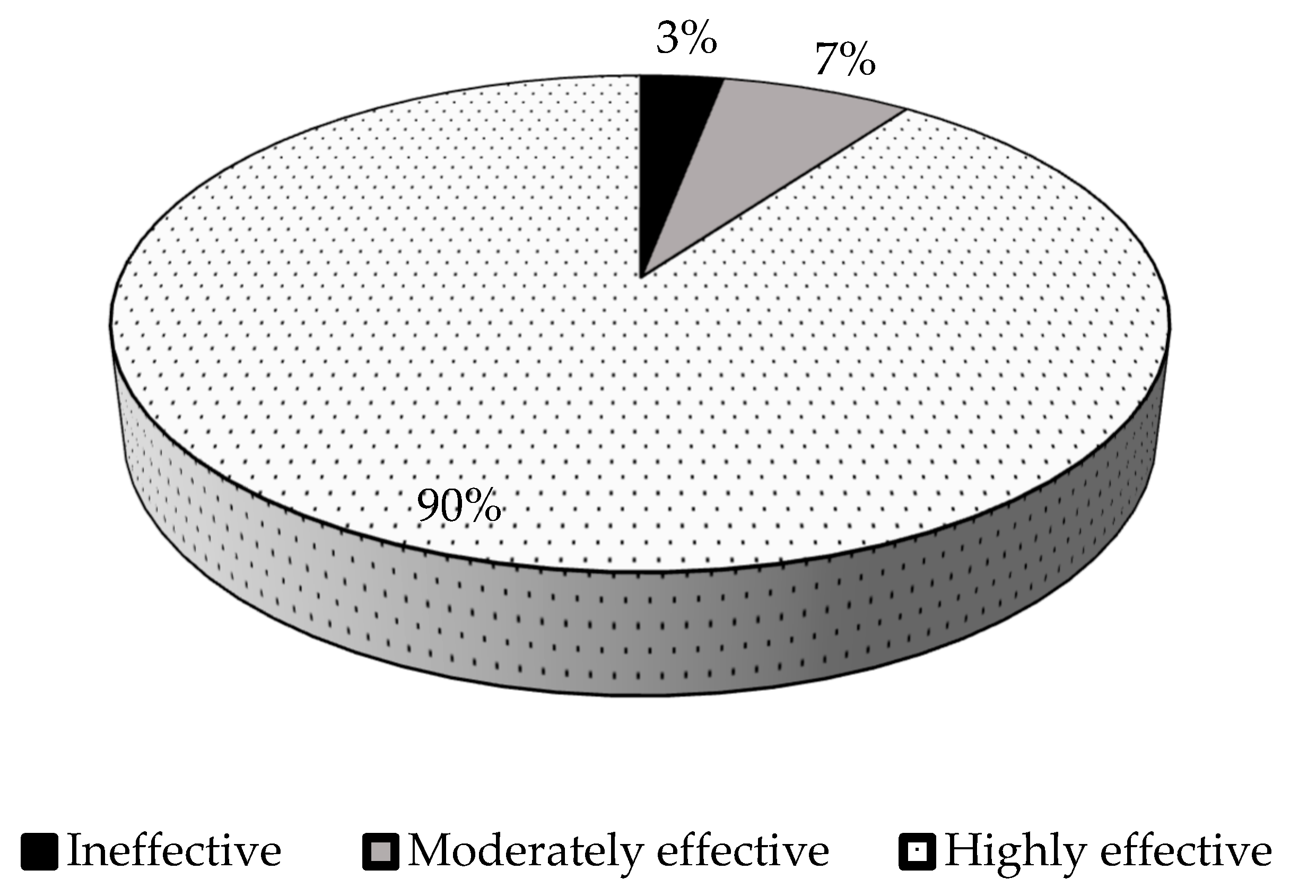

3.6. Relative Symbiotic Effectiveness of Rhizobial Isolates

3.8. Shoot δ15N and N-fixed

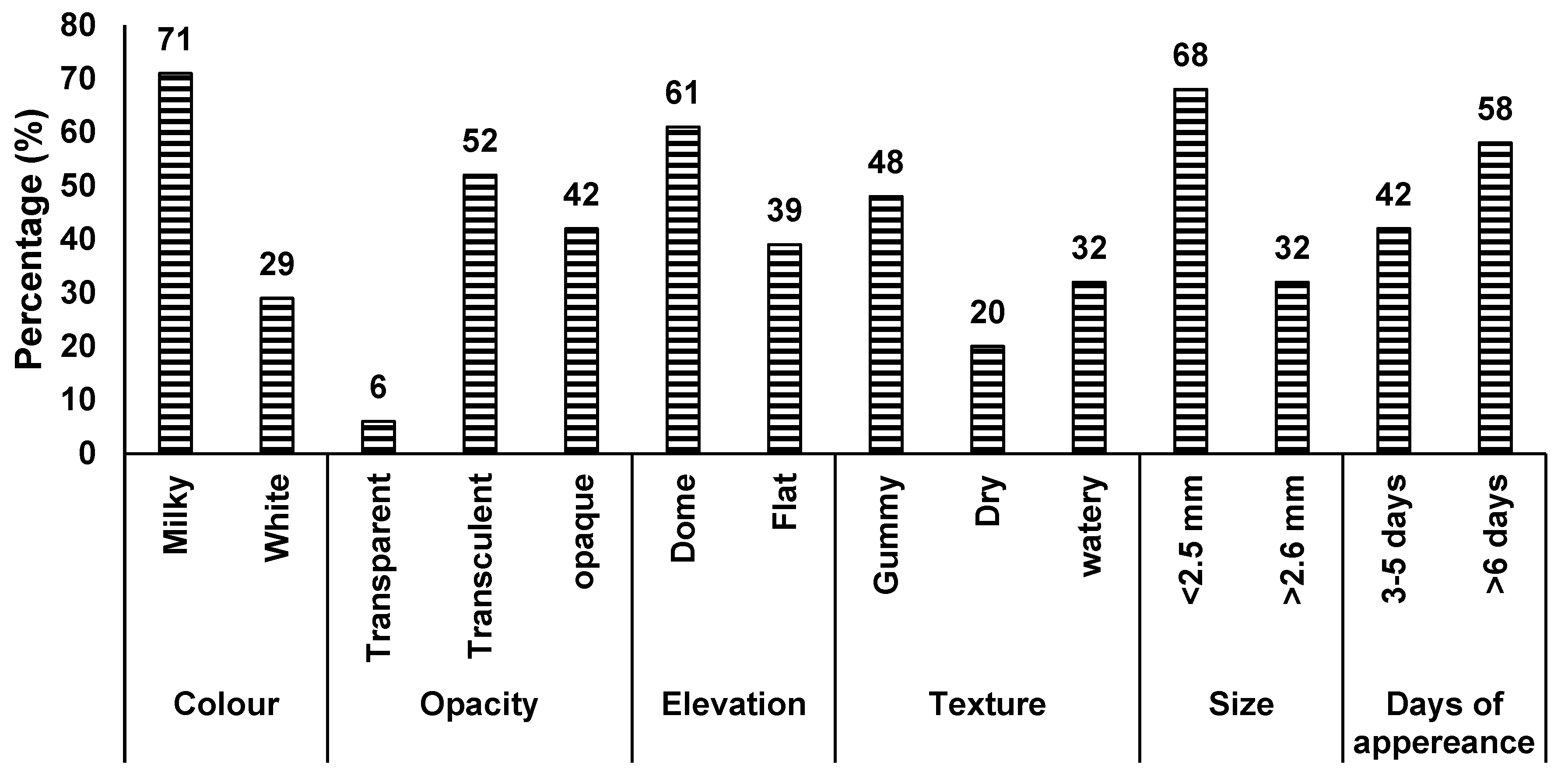

3.9. Phenotypic Characterisation of the Rhizobial Isolates

3.10. Biochemical Characterisation of Rhizobial Isolates

3.10.1. Temperature Tolerance

3.10.2. Salinity Tolerance

3.10.2. Drought Tolerance

3.10.2. IAA Production

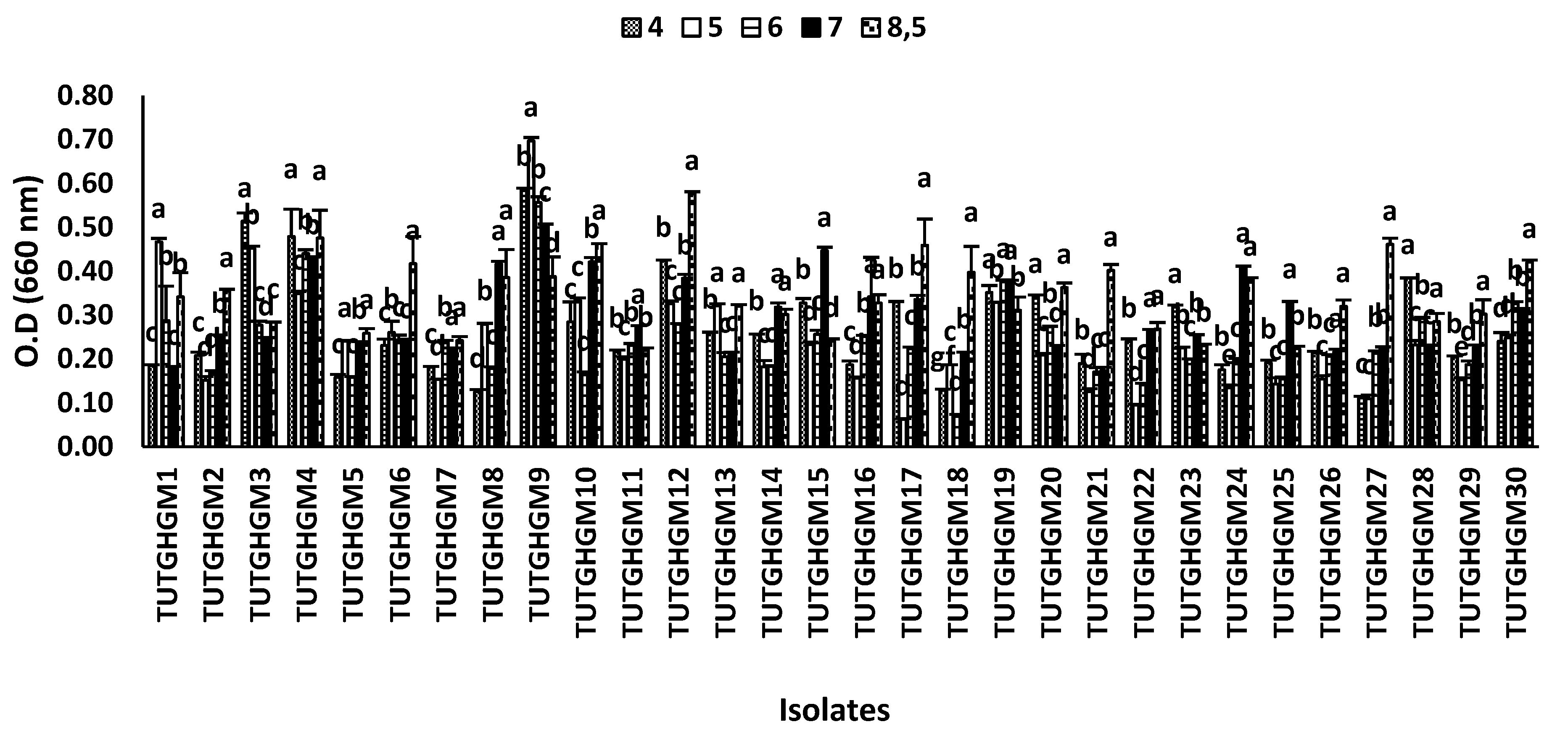

3.10.5. pH Tolerance

4. Discussion

4.1. Diversity of Soybean Rhizobial Isolates and Their Photosynthetic Performance

4.2. Plant Water-Use Efficiency and Strain Symbiotic Effectiveness

4.3. Plant Growth-Promoting Traits of the Rhizobial Isolates from Da

Supplementary Materials

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meena, I.; Meena, R.; Sharma, S.; Singh, D. Yield and Nutrient Uptake by Soybean as Influenced by Phosphorus and Sulphur Nutrition in Typic Haplustept. Madras Agricultural Journal 2015, 102, 1. [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy, D.S.; Traore, P.S.; Freduah, B.S.; Adiku, S.G.K.; Dodor, D.E.; Kumahor, S.K. Productivity of Soybean under Projected Climate Change in a Semi-Arid Region of West Africa: Sensitivity of Current Production System. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoFA-SRID. Facts & figures: Agriculture in Ghana, 2021. Statistics Research, and InformationDirectorate of Minister of Food and Agriculture.

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Mitran, T.; Meena, R.S.; Lal, R.; Layek, J.; Kumar, S.; Datta, R. Role of soil phosphorus on legume production. Legumes for soil health and sustainable management 2018, 487–510. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuba, J.; Jaiswal, S.K.; Mohammed, M.; Denwar, N.N.; Dakora, F.D. Adaptability to local conditions and phylogenetic differentiation of microsymbionts of TGx soybean genotypes in the semi-arid environments of Ghana and South Africa. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2021, 44, 126264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, S.T.; Jaiswal, S.K.; Mohammed, M.; Dakora, F.D. Studies of Phylogeny, Symbiotic Functioning and Ecological Traits of Indigenous Microsymbionts Nodulating Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc) in Eswatini Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwenda, G.M.; Hill, Y.J.; O’Hara, G.W.; Reeve, W.G.; Howieson, J.G.; Terpolilli, J.J. Competition in the Phaseolus vulgaris-Rhizobium symbiosis and the role of resident soil rhizobia in determining the outcomes of inoculation. Plant and Soil 2023, 487, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaka, F.; Dida, M.M.; Opala, P.A.; Ombori, O.; Maingi, J.; Osoro, N.; Muthini, M.; Amoding, A.; Mukaminega, D.; Muoma, J. Symbiotic Efficiency of Native Rhizobia Nodulating Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Soils of Western Kenya. International Scholarly Research Notices. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Verma, J.P. Does plant—microbe interaction confer stress tolerance in plants: a review? Microbiol. Res. 2018, 207, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, S.; Dahiya, A.; Gera, R.; Sindhu, S.S. Mitigation of abiotic stress in legume-nodulating rhizobia for sustainable crop production. Agricultural Research 2020, 9, 444–459. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Suárez, M.; Andersen, S.U.; Poole, P.S.; Sánchez-Cañizares, C. Competition, Nodule Occupancy, and Persistence of Inoculant Strains: Key Factors in the Rhizobium-Legume Symbioses. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 690567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bationo, A.; Fening, J.O.; Kwaw, A. Assessment of soil fertility status and integrated soil fertility management in Ghana. Improving the Profitability, Sustainability and Efficiency of Nutrients Through Site Specific Fertilizer Recommendations in West Africa Agro-Ecosystems: Volume 1.

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Sathya, A.; Vijayabharathi, R.; Varshney, R.K.; Gowda, C.L.; Krishnamurthy, L. Plant growth promoting rhizobia: challenges and opportunities. 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bouizgarne, B.; Oufdou, K.; Ouhdouch, Y. Actinorhizal and Rhizobial-Legume symbioses for alleviation. In Plant Microbes Symbiosis: Applied Facets; Springer New Delhi, India: 2014.

- Rasanen, L.A.; Lindstrom, K. Effects of biotic and abiotic constraints on the symbiosis between rhizobia and the tropical leguminous trees Acacia and Prosopis. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2003, 41, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Q.; Shabaan, M.; Ashraf, S.; Kamran, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Ahmad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Sarwar, M.J.; Iqbal, R.; Ali, B.; et al. Comparative efficacy of different salt tolerant rhizobial inoculants in improving growth and productivity of Vigna radiata L. under salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaitov, B.; Kurbonov, A.; Abdiev, A.; Adilov, M. Effect of chickpea in association with Rhizobium to crop productivity and soil fertility. Eurasian Journal of Soil Science 2016, 5, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, M.; Kukreja, K.; Sunita, S.; Dudeja, S. Symbiotic effectivity of high temperature tolerant mungbean (Vigna radiata) rhizobia under different temperature conditions. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci 2014, 3, 807–821. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, K.; Reckling, M.; Ramirez, M.D.A.; Djedidi, S.; Fukuhara, I.; Ohyama, T.; Yokoyama, T.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D.; Halwani, M.; Egamberdieva, D. Characterization of rhizobia for the improvement of soybean cultivation at cold conditions in central Europe. Microbes and environments 2020, 35, ME19124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- del-Canto, A.; Sanz-Saez, Á.; Sillero-Martínez, A.; Mintegi, E.; Lacuesta, M. Selected indigenous drought tolerant rhizobium strains as promising biostimulants for common bean in Northern Spain. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelar Ferreira, P.A.; Bomfeti, C.A.; Lima Soares, B.; de Souza Moreira, F.M. Efficient nitrogen-fixing Rhizobium strains isolated from amazonian soils are highly tolerant to acidity and aluminium. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2012, 28, 1947–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasegaran, P.; Hoben, H.J. Handbook for rhizobia: methods in legume-Rhizobium technology; Springer Science & Business Media: 2012.

- Vincent, J.M. A manual for the practical study of the root-nodule bacteria. 1970.

- Pongslip, N. Phenotypic and genotypic diversity of rhizobia; Bentham Science Publishers: 2012.

- Makoi, J.H.J.R.; Chimphango, S.B.M.; Dakora, F.D. Photosynthesis, water-use efficiency and δ13C of five cowpea genotypes grown in mixed culture and at different densities with sorghum. Photosynthetica 2010, 48, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Sanagala, R.; Sinilal, B.; Yadav, S.; Sarkar, A.K.; Dantu, P.K.; Jain, A. Iron availability affects phosphate deficiency-mediated responses, and evidence of cross-talk with auxin and zinc in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, E.; Amsalu, B.; Argaw, A.; Tamiru, S. Symbiotic effectiveness of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) nodulating rhizobia isolated from soils of major cowpea producing areas in Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2020, 6, 1763648. [Google Scholar]

- Purcino, H.; Festin, P.; Elkan, G. Identification of effective strains of Bradyrhizobium for Arachis pintoi. 2000.

- Ngwenya, Z.D.; Dakora, F.D. Symbiotic Functioning and Photosynthetic Rates Induced by Rhizobia Associated with Jack Bean (Canavalia ensiformis L.) Nodulation in Eswatini. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, A.; Germon, J.; Hubert, P.; Kaiser, P.; Letolle, R.; Tardieux, A.; Tardieux, P. Experimental determination of nitrogen kinetic isotope fractionation: some principles; illustration for the denitrification and nitrification processes. Plant and soil 1981, 62, 413–430. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G.D.; Ehleringer, J.R.; Hubick, K.T. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1989, 40, 503–537. [Google Scholar]

- Pausch, R.C.; Mulchi, C.L.; Lee, E.H.; Forseth, I.N.; Slaughter, L.H. Use of 13C and 15N isotopes to investigate O3 effects on C and N metabolism in soybeans. Part I. C fixation and translocation. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 1996, 59, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.A.; Chernet, M.T.; Tuji, F.A. Phenotypic, stress tolerance, and plant growth promoting characteristics of rhizobial isolates of grass pea. Int. Microbiol. 2020, 23, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilowati, A.; Puspita, A.; Yunus, A. Drought resistant of bacteria producing exopolysaccharide and IAA in rhizosphere of soybean plant (Glycine max) in Wonogiri Regency Central Java Indonesia. In Proceedings of the IOP conference series: earth and environmental science; 2018; p. 012058. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Castro, J.; Lozano, L.; Sohlenkamp, C. Dissecting the acid stress response of Rhizobium tropici CIAT 899. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 846. [Google Scholar]

- Rejili, M.; Mahdhi, M.; Fterich, A.; Dhaoui, S.; Guefrachi, I.; Abdeddayem, R.; Mars, M. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation of wild legumes in Tunisia: Soil fertility dynamics, field nodulation and nodules effectiveness. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2012, 157, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Grönemeyer, J.L.; Kulkarni, A.; Berkelmann, D.; Hurek, T.; Reinhold-Hurek, B. Rhizobia indigenous to the Okavango region in Sub-Saharan Africa: diversity, adaptations, and host specificity. Applied and environmental microbiology 2014, 80, 7244–7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwenya, Z.D.; Mohammed, M.; Jaiswal, S.K.; Dakora, F.D. Phylogenetic relationships among Bradyrhizobium species nodulating groundnut (Arachis hypogea L.), jack bean (Canavalia ensiformis L.) and soybean (Glycine max Merr.) in Eswatini. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10629. [Google Scholar]

- Gyogluu, C.; Mohammed, M.; Jaiswal, S.K.; Kyei-Boahen, S.; Dakora, F.D. Assessing host range, symbiotic effectiveness, and photosynthetic rates induced by native soybean rhizobia isolated from Mozambican and South African soils. Symbiosis 2018, 75, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Jaiswal, S.K.; Dakora, F.D. Distribution and correlation between phylogeny and functional traits of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.)-nodulating microsymbionts from Ghana and South Africa. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 18006. [Google Scholar]

- Osei, O.; Abaidoo, R.C.; Ahiabor, B.D.K.; Boddey, R.M.; Rouws, L.F.M. Bacteria related to Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense from Ghana are effective groundnut micro-symbionts. Appl Soil Ecol 2018, 127, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belane, A.K.; Dakora, F.D. Assessing the relationship between photosynthetic C accumulation and symbiotic N nutrition in leaves of field-grown nodulated cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) genotypes. Photosynthetica 2015, 53, 562–571. [Google Scholar]

- Parvin, S.; Uddin, S.; Tausz-Posch, S.; Armstrong, R.; Tausz, M. Carbon sink strength of nodules but not other organs modulates photosynthesis of faba bean (Vicia faba) grown under elevated [CO2] and different water supply. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.A.; Joseph, C.M.; Yang, G.-P.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Sanborn, J.R.; Volpin, H. Identification of lumichrome as a Sinorhizobium enhancer of alfalfa root respiration and shoot growth. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 1999, 96, 12275–12280. [Google Scholar]

- Matiru, V.; Dakora, F. Xylem transport and shoot accumulation of lumichrome, a newly recognized rhizobial signal, alters root respiration, stomatal conductance, leaf transpiration and photosynthetic rates in legumes and cereals. New Phytol. 2005, 165, 847–855. [Google Scholar]

- Matiru, V.N.; Dakora, F.D. The rhizosphere signal molecule lumichrome alters seedling development in both legumes and cereals. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Dakora, F.D.; Matiru, V.; Kanu, A.S. Rhizosphere ecology of lumichrome and riboflavin, two bacterial signal molecules eliciting developmental changes in plants. Frontiers in plant science 2015, 6, 146621. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M.; Mbah, G.C.; Sowley, E.N.; Dakora, F.D. Cowpea Genotypic Variations in N2 Fixation, Water Use Efficiency (δ13C), and Grain Yield in Response to Bradyrhizobium Inoculation in the Field, Measured Using Xylem N Solutes, 15N, and 13C Natural Abundance. Frontiers in Agronomy 2022, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, Y.; Murthy, J.; Kumar, T.R.; Rao, M.N. Phenotypic, stress tolerance and plant growth promoting characteristics of rhizobial isolates from selected wild legumes of semiarid region, Tirupati, India. Advances in Microbiology 2016, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mhadhbi, H.; Chihaoui, S.; Mhamdi, R.; Mnasri, B.; Jebara, M. A highly osmotolerant rhizobial strain confers a better tolerance of nitrogen fixation and enhances protective activities to nodules of Phaseolus vulgaris under drought stress. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011, 10, 4555–4563. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Gao, Y. Hydrogen Ion Concentration Index of Culture Media. In Quality Management in the Assisted Reproduction Laboratory; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.N.d.; Oliveira, L.A.d.; Andrade, J.S. Production and some properties of crude alkaline proteases of indigenous Central Amazonian rhizobia strains. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 2010, 53, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, D.; Kaneto, M.; Itoh, K.; Suyama, K.; Pokharel, B.B.; Gaihre, Y.K. Genetic diversity of soybean-nodulating rhizobia in Nepal in relation to climate and soil properties. Plant and Soil 2012, 357, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Han, X.Z.; Ji, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Wang, E.T.; Xie, Z.H.; Chen, W.F. Abundance and diversity of soybean-nodulating rhizobia in black soil are impacted by land use and crop management. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2014, 80, 5394–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolates | A | Gs | Ci | E | Ci/Ca | WUEi |

| µmol (CO2) m-2s-1 |

mol(H2O) m-2s-1 |

µmol(CO2) molair-1 |

mol(H2O) m-2s-1 |

µmol(CO2) mol-1(H2O) |

||

| TUTGMGH1 | 11.34±0.76d-l | 0.16±0.01j-m | 257.38±1.38fg | 5.41±0.07ij | 0.65±0.01i-j | 70.36±2.43bc |

| TUTGMGH2 | 12.48±0.40fg | 0.26±0.01edf | 285.89±3.89a-d | 7.81±0.21d-h | 0.74±0.01a-e | 48.30±2.11d-g |

| TUTGMGH3 | 11.59±0.01g-k | 0.19±0.02hij | 277.25±5.98a-f | 6.12±0.44g-j | 0.72±0.01a-i | 63.80±7.59b-e |

| TUTGMGH4 | 14.81±0.07bc | 0.33±0.0001b | 285.99±0.27a-d | 9.09±0.01bcd | 0.75±0.001abc | 44.54±0.13hij |

| TUTGMGH5 | 10.62±0.12j-m | 0.18±0.03h-l | 261.91±21.91d-g | 9.84±2.46cd | 0.67±0.06g-j | 65.69±16.51bcd |

| TUTGMGH6 | 11.81±0.01ghi | 0.30±0.03c | 290.18±0.66ab | 7.97±0.001c-g | 0.76±0.003ab | 40.49±3.49ij |

| TUTGMGH7 | 11.26±0.02h-m | 0.27±0.003cd | 290.69±3.60ab | 8.29±0.004b-f | 0.75±0.01abc | 41.29±0.54ij |

| TUTGMGH8 | 16.16±0.63a | 0.39±0.03a | 285.08±0.25a-e | 12.62±0.01a | 0.76±0.003ab | 41.06±1.20ij |

| TUTGMGH9 | 13.05±0.10ef | 0.21±0.01ghi | 266.68±5.76b-h | 7.40±0.04c-h | 0.70±0.01b-j | 62.08±2.23b-f |

| TUTGMGH10 | 12.44±0.31fg | 0.24±0.01efg | 271.05±1.85a-f | 8.12±0.35c-f | 0.71±0.01a-i | 53.08±1.38b-i |

| TUTGMGH11 | 16.18±0.01a | 0.39±0.001a | 286.22±0.18a-d | 10.11±0.01b | 0.76±0.001ab | 41.57±0.11ij |

| TUTGMGH12 | 9.03±0.73o | 0.14±0.002lm | 260.12±9.90efg | 6.01±0.06hij | 0.67±0.02f-j | 62.60±5.87b-f |

| TUTGMGH13 | 11.78±0.74g-j | 0.23±0.01efg | 274.35±1.67a-g | 8.74±0.10b-e | 0.70±0.001a-i | 50.58±0.47e-j |

| TUTGMGH14 | 10.94±0.00h-m | 0.27±0.001cde | 283.46±7.89a-e | 8.38±1.22b-f | 0.74±0.02a-d | 40.83±0.16ij |

| TUTGMGH15 | 9.25±0.04no | 0.13±0.01mn | 243.343±10.34gh | 7.19±1.25d-i | 0.63±0.02j | 71.59±6.07b |

| TUTGMGH16 | 10.15±0.08mn | 0.17±0.003i-l | 263.78±3.02c-g | 7.09±0.13e-i | 0.69±0.01c-j | 58.43±1.51c-g |

| TUTGMGH17 | 10.96±0.38h-m | 0.25±0004def | 288.84±3.23abc | 8.41±0.03b-f | 0.76±0.01ab | 43.13±1.53ij |

| TUTGMGH18 | 7.76±0.08p | 0.15±0.0001klm | 281.28±0.91a-f | 7.24±0.002c-i | 0.71±0.002a-i | 51.77±0.57-i |

| TUTGMGH19 | 11.44±0.36g-l | 0.28±0.003cd | 293.69±2.53a | 8.67±0.32b-e | 0.77±0.02a | 41.01±0.85ij |

| TUTGMGH20 | 7.86±0.02p | 0.21±0.01kmn | 294.82±3.90a | 7.84±0.06d-h | 0.76±0.01ab | 37.63±1.68j |

| TUTGMGH21 | 10.40±0.29lm | 0.15±0.002klm | 230.75±16.97h | 6.12±0.002g-j | 0.61±0.04e-j | 70.88±2.75bc |

| TUTGMGH22 | 15.71±0.35ab | 0.30±0.0014c | 272.51±2.23a-g | 7.79±0.11d-h | 0.71±0.07a-i | 52.62±0.54e-i |

| TUTGMGH23 | 12.04±0.29fgh | 0.25±0.02def | 276.83±6.81a-f | 8.34±0.02b-f | 0.76±0.004ab | 47.90±2.15g-j |

| TUTGMGH24 | 13.57±0.42de | 0.21±0.002gh | 262.06±4.01b-g | 7.91±0.16-h | 0.67±0.01f-j | 63.60±1.42b-e |

| TUTGMGH25 | 13.07±0.19ef | 0.18±0.002h-k | 265.45±1.68b-g | 6.49±0.04f-j | 0.66±0.01hij | 71.43±1.26b |

| TUTGMGH26 | 10.58±0.19jkl | 0.11±0.001n | 209.91±3.81i | 4.80±0.03jk | 0.53±0.010j | 97.09±2.40a |

| TUTGMGH27 | 11.46±0.01g-l | 0.20±0.001ghi | 245.10±20.48gh | 7.40±0.54d-h | 0.64±0.06j | 56.32±0.23d-h |

| TUTGMGH28 | 11.403±0.08g-l | 0.22±0.002fg | 279.53±0.97a-f | 7.18±0.05d-i | 0.73±0.002a-h | 50.81±0.70f-i |

| TUTGMGH29 | 10.67±0.17i-m | 0.23±0.001fg | 279.44±0.07a-f | 8.24±0.50b-f | 0.74±0.02a-f | 46.63±0.63d-j |

| TUTGMGH30 | 14.74±0.71bc | 0.20±0.002ghi | 259.90±6.45efg | 7.79±0.47d-h | 0.64±0.02j | 72.20±3.08b |

| TUTGMGH31 | 11.49±0.28g-l | 0.18±0.001h-l | 265.91±8.97b-g | 7.68±0.57d-h | 0.68±0.02d-j | 64.15±0.68b-e |

|

Bradyrhizobium strain WB74 |

15.59±0.03bc | 0.37±0.001a | 279.293±0.24a-f | 12.10±0.01a | 0.75±0.001a-d | 42.39±0.18ij |

| Uninoculated | 2.64±0.26q | 0.07±0.0002o | 293.67±0.69a | 3.58±0.01i | 0.76±0.019ab | 40.43±4.08ij |

| 5 mM KNO3 | 14.47±0.53cd | 0.21±0.001ghi | 256.56±4.31fg | 8.81±0.29b-e | 0.72±0.002a-i | 70.34±2.60bc |

| F- statistics | 59.32** | 46.96** | 6.66*** | 9.72*** | 6.99*** | 12.68** |

| Isolates | Shoot dry matter | Root dry matter | Total biomass | C concentration | C content | δ13C | C:N ratio |

| g plant-1 | g plant-1 | g plant-1 | % | g plant-1 | ‰ | g.g-1 | |

| TUTGMGH1 | 1.72±0.09a-d | 0.64±0.03b-e | 2.36±0.13bc | 43.30±0.05fgh | 74.48±4.05ab | -27.52±0.01e-i | 18.31±0.04c-g |

| TUTGMGH2 | 1.44±0.03c-h | 0.50±0.05c-g | 1.94±0.07c-k | 43.27±0.03f-i | 62.16±1.22b-k | -27.95±0.02mn | 17.99±0.03c-i |

| TUTGMGH3 | 1.74±0.09abc | 0.51±0.01c-g | 2.25±0.11c-f | 43.42±0.28d-g | 75.58±4.29bc | -27.51±0.01d-h | 18.59±0.18c-g |

| TUTGMGH4 | 1.32±0.23e-l | 0.37±0.01fgh | 1.69±0.26h-l | 42.99±0.13ij | 56.83±10.89d-m | -27.65±0.06h-k | 17.40±0.02e-l |

| TUTGMGH5 | 1.22±0.05h-l | 0.35±0.01gh | 1.57±0.05g-k | 43.37±0.06efg | 52.92±2.07h-m | -28.11±0.03no | 17.33±0.11e-l |

| TUTGMGH6 | 1.49±0.07c-j | 0.85±0.18b | 2.33±0.19bcd | 43.81±0.09bc | 65.14±3.01b-j | -27.74±0.03jkl | 17.55±0.27d-l |

| TUTGMGH7 | 1.54±0.01b-i | 0.50±0.04-g | 2.03±0.03c-h | 43.72±0.03bcd | 67.19±0.35c-g | -28.07±0.01no | 15.57±0.10l |

| TUTGMGH8 | 1.27±0.14f-l | 0.45±0.02d-h | 1.59±0.05d-j | 42.82±0.10jk | 54.37±6.13g-m | -28.13±0.06o | 16.54±0.45g-l |

| TUTGMGH9 | 1.61±0.19b-f | 0.62±0.01b-e | 2.23±0.19b-e | 43.27±0.09f-i | 69.64±8.01b-e | -27.19±0.04a | 16.69±0.10f-l |

| TUTGMGH10 | 1.08±0.02l | 0.39±0.01e-h | 1.47±0.01lmn | 42.76±0.016jk | 46.04±0.86lm | -27.67±0.03h-l | 16.17±0.10h-m |

| TUTGMGH11 | 1.53±0.05b-i | 0.37±0.02fgh | 1.90±0.04d-k | 43.69±0.11bcd | 66.85±2.11c-g | -27.25±0.02ab | 17.07±0.28e-l |

| TUTGMGH12 | 1.38±0.03d-k | 0.57±0.02c-g | 1.95±0.05c-k | 43.44±0.02d-g | 59.81±1.40i-m | -27.76±0.07jkl | 19.54±0.24cd |

| TUTGMGH13 | 1.21±0.08i-l | 0.52±0.002c-g | 1.73±0.08g-l | 42.86±0.011j | 51.86±3.23g-k | -27.69±0.01i-l | 21.54±0.07b |

| TUTGMGH14 | 0.45±0.05mn | 0.23±0.01h | 0.68±0.05n | 43.66±0.11b-e | 19.44±2.42mn | -27.60±0.05g-j | 19.86±1.04bc |

| TUTGMGH15 | 1.23±0.09g-l | 0.61±0.003c-f | 1.84±0.09e-l | 43.45±0.09d-g | 53.43±3.96h-l | -27.38±0.09b-f | 19.87±0.17bc |

| TUTGMGH16 | 1.54±0.03b-i | 0.61±0.01c-f | 2.15±0.04c-g | 43.01±0.13hij | 66.24±1.60b-i | -27.85±0.01lm | 16.04±0.09i-l |

| TUTGMGH17 | 1.57±0.01b-h | 0.67±0.08bcd | 1.90±0.40c-f | 43.56±0.01c-f | 68.25±0.28b-g | -27.40±0.02b-f | 18.78±0.36bcd |

| TUTGMGH18 | 0.72±0.01m | 0.42±0.05d-h | 1.14±0.04n | 42.53±0.35kl | 30.48±0.38no | -27.97±0.05mno | 18.67±0.37c-f |

| TUTGMGH19 | 1.56±0.07b-i | 0.60±0.01c-f | 2.16±0.06c-h | 43.32±0.07fg | 67.43±2.83b-h | -27.35±0.02a-e | 17.68±2.09d-k |

| TUTGMGH20 | 1.62±0.04b-f | 0.61±0.03c-f | 2.23±0.07c-f | 43.81±0.03bc | 70.97±1.74a-d | -27.82±0.03klm | 15.68±0.68kl |

| TUTGMGH21 | 1.99±0.10a | 0.72±0.02bc | 2.70±0.12ab | 42.77±0.03jk | 84.98±4.38a | -27.37±0.03b-f | 17.05±0.10e-l |

| TUTGMGH22 | 1.17±0.09jkl | 0.64±0.09b-e | 1.80±0.15f-l | 41.88±0.06m | 48.87±3.73jkl | -27.45±0.05c-g | 17.18±0.04e-l |

| TUTGMGH23 | 1.55±0.10c-g | 0.52±0.07c-g | 2.07±0.15c-h | 43.35±0.15efg | 70.75±2.02a-d | -28.44±0.04q | 16.03±1.29i-l |

| TUTGMGH24 | 1.61±0.02b-f | 0.51±0.12c-g | 2.11±0.11c-i | 44.42±0.09a | 71.36±0.84a-d | -27.24±0.01ab | 18.61±0.36e-g |

| TUTGMGH25 | 1.30±0.03e-k | 0.61±0.05c-f | 1.91±0.02d-k | 42.43±0.05l | 55.02±1.38e-l | -28.29±0.04p | 15.91±0.50jkl |

| TUTGMGH26 | 0.60±0.32mn | 0.60±0.23c-f | 1.20±0.44mn | 43.21±0.12ghi | 26.00±13.95mn | -27.33±0.02abc | 16.87±0.58e-l |

| TUTGMGH27 | 1.48±0.15c-j | 0.53±0.02c-g | 2.00±0.14c-j | 42.84±0.04j | 63.25±6.52b-j | -27.34±0.01a-d | 16.86±0.58e-l |

| TUTGMGH28 | 1.54±0.15b-i | 0.58±0.09c-g | 2.12±0.20c-h | 43.90±0.03b | 67.76±6.50b-h | -27.54±0.01f-i | 17.55±0.29d-l |

| TUTGMGH29 | 1.48±0.02c-k | 0.45±0.01d-h | 1.93±0.01c-k | 44.30±0.02a | 65.56±0.74b-h | -27.74±0.01jkl | 17.54±0.67d-l |

| TUTGMGH30 | 1.58±0.09b-f | 0.72±0.05bc | 2.30±0.04bcd | 43.83±0.01bc | 69.23±3.79b-f | -27.66±0.10h-k | 17.84±0.13d-j |

| TUTGMGH31 | 1.13±0.04kl | 0.41±0.12-h | 1.54±0.07klm | 42.84±0.04j | 48.26±1.83klm | -27.34±0.11a-d | 16.86±0.58e-l |

|

Bradyrhizobium strain WB74 |

1.07±0.001l | 0.57±0.04c-g | 1.64±0004i-m | 43.88±0.01b | 46.95±0.02l | -29.55±0.06r | 21.59±0.08b |

| Uninoculated | 0.33±0.01n | 0.22±0.07h | 0.54±0.07o | 40.15±0.02n | 13.12±0.30n | -27.77±0.09jkl | 18.15±0.98c-i |

| 5 mM KNO3 | 1.85±0.07ab | 1.13±0.08a | 2.97±0.07a | 41.77±0.01m | 77.14±2.78ab | -27.75±0.01jkl | 23.59±0.1.71a |

| F-statistics | 13.50** | 5.74*** | 15.74** | 68.00** | 13.18** | 70.00** | 8.90*** |

| Isolates | Nodule number | Nodule fresh weight | Relative symbiotic effectiveness | N concentration | N content | δ15N | N-fixed |

| per plant | g plant-1 | % | % | g plant-1 | ‰ | g plant-1 | |

| TUTGMGH1 | 19±0.88hij | 0.64±0.01a | 161±8.63ab | 2.36±0.01f-i | 4.07±0.23b-e | -2.02±0.02f-i | 3.82±0.23b-e |

| TUTGMGH2 | 10±0.58k | 0.52±0.003abc | 134±2.55b-i | 2.41±0.02d-i | 3.46±0.06c-h | -2.08±0.05f-k | 3.21±0.06c-h |

| TUTGMGH3 | 37±1.15ab | 0.44±0.02c-f | 163±8.63ab | 2.25±0.02ghi | 3.91±0.19b-f | -1.76±0.05d | 3.66±0.19b-f |

| TUTGMGH4 | 30±1.15b-e | 0.61±0.01ab | 124±24.07d-j | 2.53±0.03b-h | 3.36±0.70c-h | -2.15±0.05g-l | 3.11±0.70c-h |

| TUTGMGH5 | 25±6.35e-i | 0.34±0.002f-i | 114±4.32f-j | 2.52±0.03b-h | 3.07±0.14fgh | -1.94±0.02d-g | 2.82±0.14fgh |

| TUTGMGH6 | 18±0.58h-j | 0.52±0.001bc | 139±6.14b-h | 2.60±0.01b-f | 3.87±0.18b-f | -1.95±0.02d-g | 3.62±0.18b-f |

| TUTGMGH7 | 20±6.69g-j | 0.42±0.02c-g | 144±0.82b-g | 2.72±0.03abc | 4.18±0.03a-d | -2.28±0.01jkl | 3.93±0.03a-d |

| TUTGMGH8 | 24±1.73-j | 0.44±0.01c-f | 119±1.49e-j | 2.61±0.07b-f | 3.31±0.40d-h | -2.35±0.01l | 3.06±0.40d-h |

| TUTGMGH9 | 35±5.77abc | 0.51±0.10bcd | 150±17.59b-e | 2.59±0.02b-f | 4.16±0.45a-d | -2.17±0.02g-l | 3.91±0.45a-d |

| TUTGMGH10 | 16±0.58jk | 0.43±0.01c-f | 101±1.89j | 2.61±0.04b-f | 2.81±0.05gh | -1.76±0.02d | 2.56±0.05gh |

| TUTGMGH11 | 28±0.88c-g | 0.43±0.003c-f | 143±4.32b-g | 2.59±0.06b-f | 3.96±0.15b-f | -2.31±0.03kl | 3.71±0.15b-f |

| TUTGMGH12 | 34±0.33bd | 0.56±0.01ab | 129±2.97c-j | 2.27±0.05ghi | 3.13±0.11e-h | -2.18±0.01g-l | 2.88±0.11e-h |

| TUTGMGH13 | 30±1.15b-e | 0.40±0.03d-h | 133±7.01g-j | 2.33±0.08f-i | 2.79±0.07gh | -2.13±0.05g-l | 2.54±0.07gh |

| TUTGMGH14 | 24±2.03e-j | 0.36±0.04fgh | 42±5.13k | 2.23±0.21hi | 0.99±0.16ij | -1.26±0.03c | 0.75±0.16j |

| TUTGMGH15 | 26±6.43d-h | 0.40±0.03d-h | 115±8.63f-j | 2.28±0.03ghi | 2.81±0.25gh | -2.16±0.02g-l | 2.56±0.25gh |

| TUTGMGH16 | 20±0.58g-j | 0.43±0.10c-f | 144±3.24b-g | 2.70±0.01a-d | 4.16±0.10a-d | -2.64±0.28m | 3.91±0.10a-d |

| TUTGMGH17 | 25±3.06e-g | 0.43±0.01c-f | 146±0.627b-g | 2.23±0.02ghi | 3.50±0.02c-h | -2.11±0.05g-l | 3.25±0.02c-h |

| TUTGMGH18 | 20±3.76g-j | 0.19±0.01jk | 67±0.82j | 2.17±0.11i | 1.56±0.01i | -2.14±0.01g-l | 1.31±0.10i |

| TUTGMGH19 | 22±0.58e-j | 0.55±0.03ab | 145±6.21b-g | 2.78±0.06ab | 4.33±0.24abc | -2.01±0.03e-h | 4.08±0.24abc |

| TUTGMGH20 | 43±1.45a | 0.38±0.01e-h | 151±3.77b-e | 2.41±0.11d-i | 3.90±0.15b-f | -2.29±0.04jkl | 3.65±0.15b-f |

| TUTGMGH21 | 27±0.33c-h | 0.50±0.01b-e | 186±9.51a | 2.53±0.03b-g | 5.02±0.23a | -2.23±0.03h-l | 4.77±0.23a |

| TUTGGH22 | 20±0.88g-j | 0.39±0.04e-i | 109±8.24hij | 2.34±0.10f-i | 2.71±0.14gh | -2.23±0.01h-l | 2.46±0.14gh |

| TUTGMGH23 | 23±0.33e-j | 0.51±0.01b-e | 153±4.59bcd | 2.92±0.04a | 4.77±0.12ab | -2.65±0.24m | 4.53±0.12ab |

| TUTGMGH24 | 21±0.33f-j | 0.38±0.03d-h | 150±1.89b-e | 2.39±0.04f-i | 3.84±0.10b-f | -1.26±0.03c | 3.59±0.10b-f |

| TUTGMGH25 | 35±1.53ab | 0.58±0.01ab | 121±2.97b-j | 2.69±0.07a-e | 3.49±0.01c-h | -2.79±0.04m | 3.24±0.01c-h |

| TUTGMGH26 | 16±0.88ijk | 0.18±0.05k | 56±29.93k | 2.46±0.16c-i | 1.57±0.92i | -2.05±0.001f-j | 1.32±0.92i |

| TUTGMGH27 | 16±1.73jk | 0.24±0.03ijk | 138±14.30b-i | 2.37±0.16f-i | 3.47±0.35c-h | -2.08±0.03f-k | 3.22±0.35c-h |

| TUTGMGH28 | 29±1.15b-f | 0.31±0.01ghi | 144±13.75b-g | 2.36±0.15f-i | 3.64±0.41c-g | -1.86±0.05def | 3.39±0.41c-g |

| TUTGMGH29 | 20±0.33g-j | 0.43±0.002c-f | 138±1.62b-i | 2.43±0.20c-i | 3.60±0.29c-g | -2.10±0.05f-k | 3.35±0.29c-g |

| TUTGMGH30 | 21±1.45f-g | 0.40±0.08d-h | 147±8.09b-f | 2.46±0.02c-i | 3.88±0.20b-f | -1.79±0.02de | 3.63±0.20b-f |

| TUTGMGH31 | 16±0.58jk | 0.31±0.01ghi | 105±4.05ij | 2.37±0.16f-i | 2.68±0.29gh | -2.08±0.04f-k | 2.43±0.29gh |

| Bradyrhizobium strain WB74 | 30±0.33b-e | 0.29±0.01hij | 100±0.00j | 2.40±0.16e-i | 2.57±0.17h | -2.26±0.04i-l | 2.32±0.17h |

| Uninoculated | NA | NA | NA | 1.13±0.05k | 0.37±0.02j | +1.55±0.01b | NA |

| 5 mM KNO3 | NA | NA | NA | 1.39±0.02j | 2.57±0.12g | +2.16±0.06a | NA |

| F-statistics | 8.05*** | 9.95*** | 9.90*** | 14.97** | 12.96** | 194.76** | 12.96** |

| Isolates |

Temperature ℃ |

Salinity (NaCl) % |

pH indicator | ||||||||||||

| 25 | 28 | 30 | 37 | 40 | 45 | 0.01 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | BTB | ||

| TUTGMGH1 | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH2 | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | - | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH4 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH5 | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | - | - | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH6 | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH7 | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH8 | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH9 | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH10 | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH11 | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH12 | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH13 | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH14 | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH15 | ++ | +++ | + | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH16 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH17 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | - | - | - | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH18 | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH19 | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH20 | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH21 | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH22 | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH23 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH24 | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH25 | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | - | - | - | - | - | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH26 | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH27 | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | Blue | |

| TUTGMGH28 | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | - | - | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | - | blue | |

| TUTGMGH29 | + | +++ | + | + | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH30 | + | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | Yellow | |

| TUTGMGH31 | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | Yellow | |

| Isolates | Drought | IAA | |||

| Control | 5% | 15% | 30% | (µg mL-1) | |

| TUTGMGH1 | 0.170±0.012ijk | 0.204±0.003fgh | 0.084±0.001lm | 0.078±0.0003e-h | 8.59±0.03d |

| TUTGMGH2 | 0.333±0.006klm | 0.142±0.001 | 0.088±0.005jkl | 0.065±0.006gh | 6.52±0.15f |

| TUTGMGH3 | 0.262±0.001hij | 0.258±0.002de | 0.176±0.004b | 0.069±0.002fgh | 9.92±0.10b |

| TUTGMGH4 | 0.330±0.036d-g | 0.210±0.001fg | 0.077±0.001mn | 0.075±0.0003e-h | 8.59±0.47d |

| TUTGMGH5 | 0.238±0.023ij | 0.103±0.001k-n | 0.144±0.003e | 0.083±0.002d-h | 9.39±0.16bc |

| TUTGMGH6 | 0.634±0.048b | 0.256±0.005de | 0.114±0.001h | 0.083±0.002d-h | 8.74±0.054cd |

| TUTGMGH7 | 0.225±0.003ijk | 0.131±0.001i-m | 0.110±0.002h | 0.084±0.001d-h | 8.49±0.15de |

| TUTGMGH8 | 0.282±0.0196f-i | 0.145±0.005 | 0.135±0.006ef | 0.086±0.002def | 9.85±0.01b |

| TUTGMGH9 | 0.526±0.015c | 0.523±0.003a | 0.157±0.009d | 0.067±0.0003fgh | 8.30±0.13de |

| TUTGMGH10 | 0.277±0.003f-i | 0.377±0.067c | 0.171±0.003bc | 0.154±0.026b | 4.52±0.03g |

| TUTGMGH11 | 0.137±0.002mn | 0.099±0.001lmn | 0.085±0.002klm | 0.106±00.004c | 8.65±0.11d |

| TUTGMGH12 | 0.639±0.019a | 0.424±0.002b | 0.243±0.001a | 0.164±0.001a | 8.11±0.64de |

| TUTGMGH13 | 0.338±0.007 | 0.175±0.0003f-k | 0.165±0.002cd | 0.065±0.002h | 7.75±0.10e |

| TUTGMGH14 | 0.105±0.002n | 0.093±0.0003mn | 0.057±0.0003p | 0.089±0.0003cde | 4.01±.07gh |

| TUTGMGH15 | 0.307±0.003e-h | 0.082±0.001n | 0.072±0.001no | 0.085±0.0003d-g | 7.75±0.05e |

| TUTGMGH16 | 0.447±0.003d | 0.218±0.0003ef | 0.164±0.001cd | 0.098±0.0003cd | 11.37±0.23a |

| TUTGMGH17 | 0.350±0.002def | 0.172±0.010f-k | 0.106±0.0003hi | 0.041±0.001 | 8.49±0.04de |

| TUTGMGH18 | 0.203±0.042jkl | 0.096±0.002lmn | 0.127±0.001fg | 0.069±0.001fgh | 4.16±0.37gh |

| TUTGMGH19 | 0.223±0.007ijk | 0.461±0.038b | 0.124±0.003g | 0.142±0.001b | 4.69±0.35g |

| TUTGMGH20 | 0.314±0.005e-h | 0.128±0.0003i-n | 0.097±0.001ij | 0.075±0.001e-h | 3.00±0.14ij |

| TUTGMGH21 | 0.270±0.061g-j | 0.167±0.006g-j | 0.166±0.005dd | 0.101±0.0123cd | 6.35±0.03f |

| TUTGMGH22 | 0.266±0.002g-j | 0.086±0.003mn | 0.05±0.001q | 0.067±0.0003fgh | 8.06±0.69de |

| TUTGMGH23 | 0.265±0.013hij | 0.176±0.004f-j | 0.081±0.001lm | 0.085±0.00d-g1 | 4.48±0.29g |

| TUTGMGH24 | 0.156±0.011lmn | 0.127±0.006j-n | 0.090±0.0003jkl | 0.091±0.003cde | 1.21±0.14k |

| TUTGMGH25 | 0.228±0.012ijk | 0.128±0.001i-n | 0.139±0.003e | 0.078±0.001e-h | 2.76±0.04jk |

| TUTGMGH26 | 0.258±0.009hij | 0.161±0.005hij | 0.096±0.001j | 0.090±0.001cde | 0.98±0.11l |

| TUTGMGH27 | 0.235±0.008ij | 0.159±0.003hij | 0.162±0.001cd | 0.074±0.002e-h | 3.02±0.22ij |

| TUTGMGH28 | 0.388±0.002de | 0.159±0.003hij | 0.162±0.001cd | 0.074±0.002e-h | 2.14±0.02k |

| TUTGMGH29 | 0.269±0.001g-j | 0.105±0.0003k-n | 0.067±0.001o | 0.044±0.004i | 4.12±0.07gh |

| TUTGMGH30 | 0.227±0.003ijk | 0.282±0.003d | 0.094±0.001jk | 0.089±0.001cde | 3.59±0.26hi |

| TUTGMGH31 | 0.257±0.009hij | 0.160±0.004hij | 0.096±0.001j | 0.091±0.001cde | 0.98±0.11l |

| F-statistics | 41.294** | 62.881** | 207.34** | 22.857** | 135.02** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).