Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

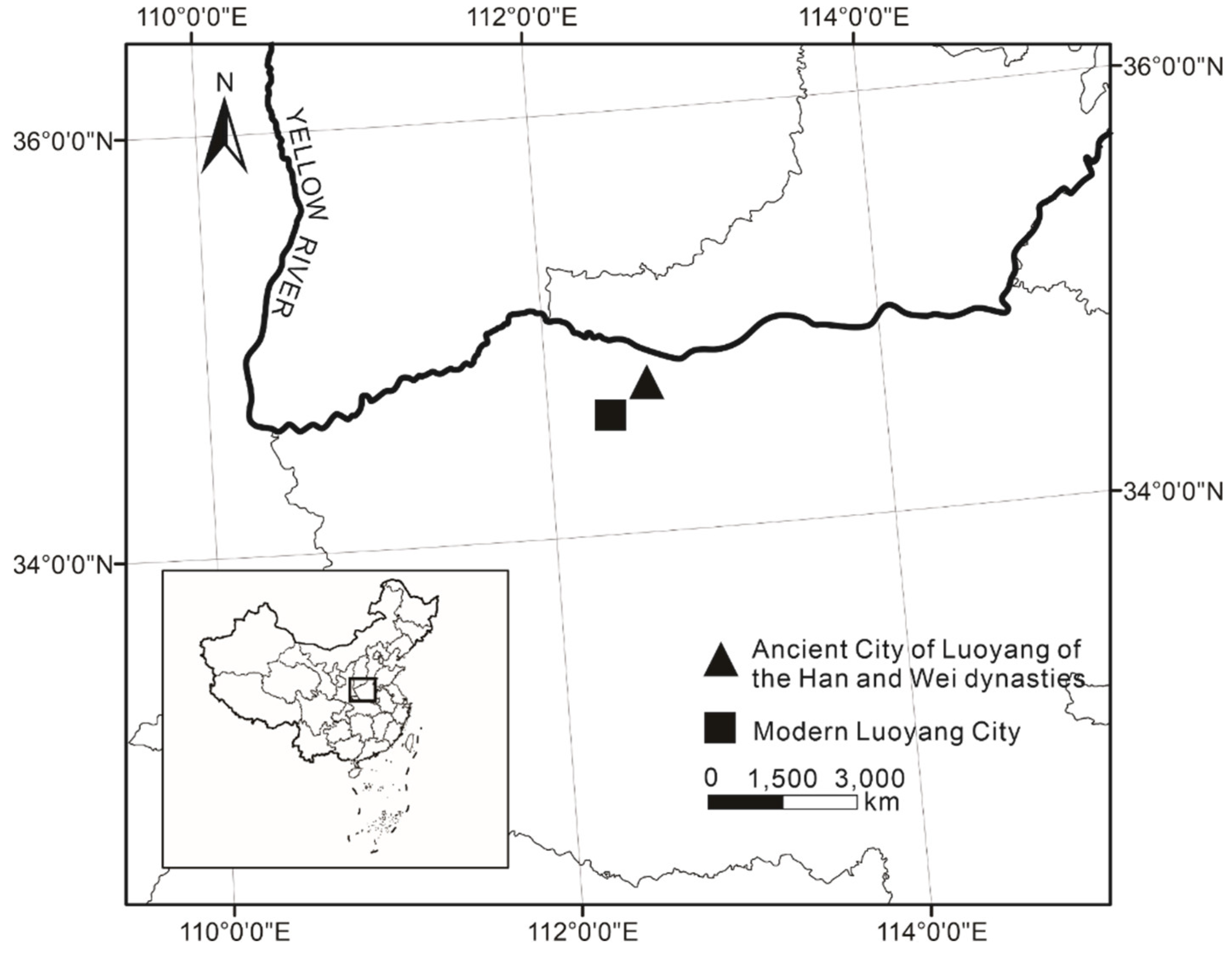

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Research Objects and the Time

2.3. Taxonomic Study

2.4. Climatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomic Work on Plants

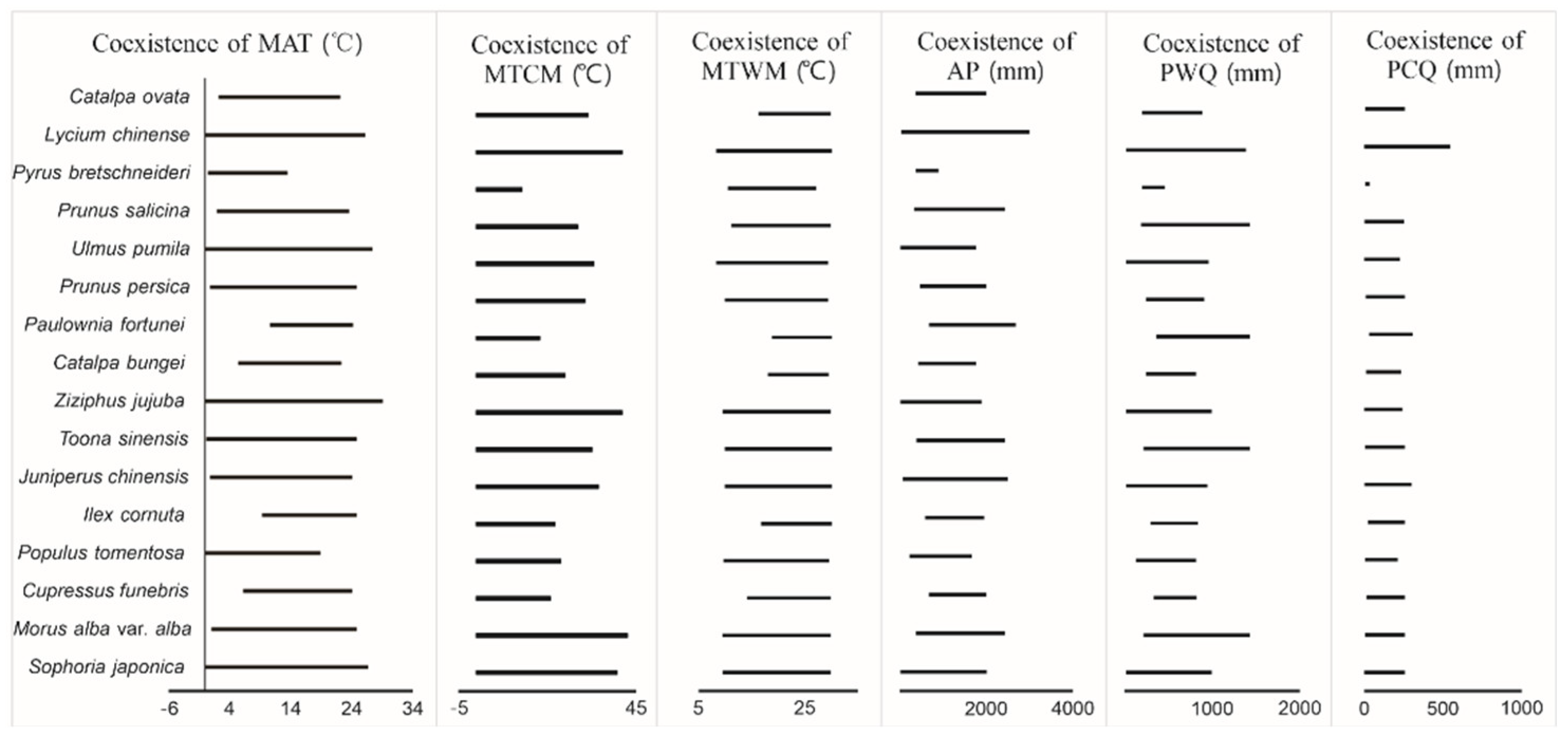

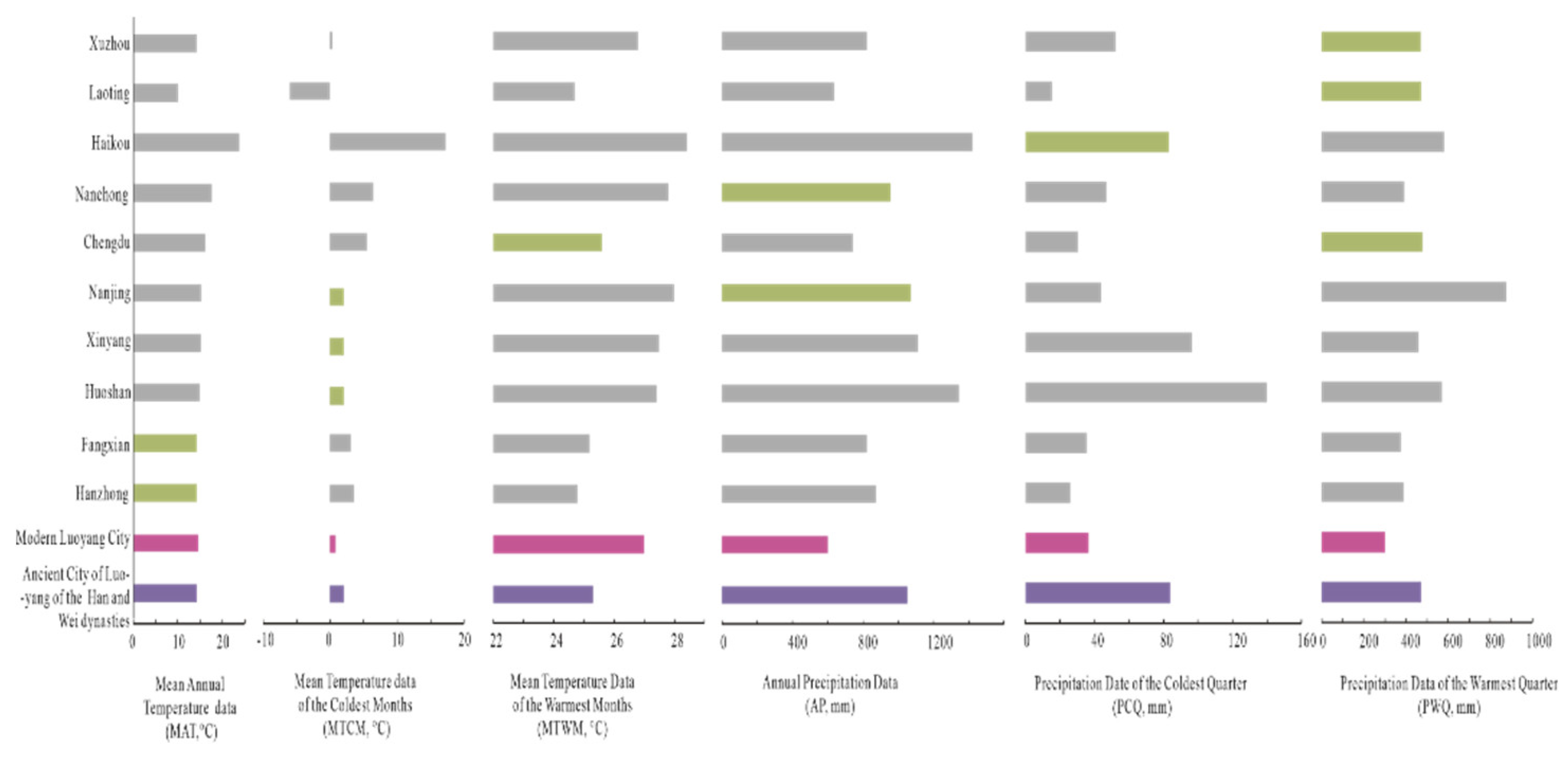

3.2. Climatic Analysis

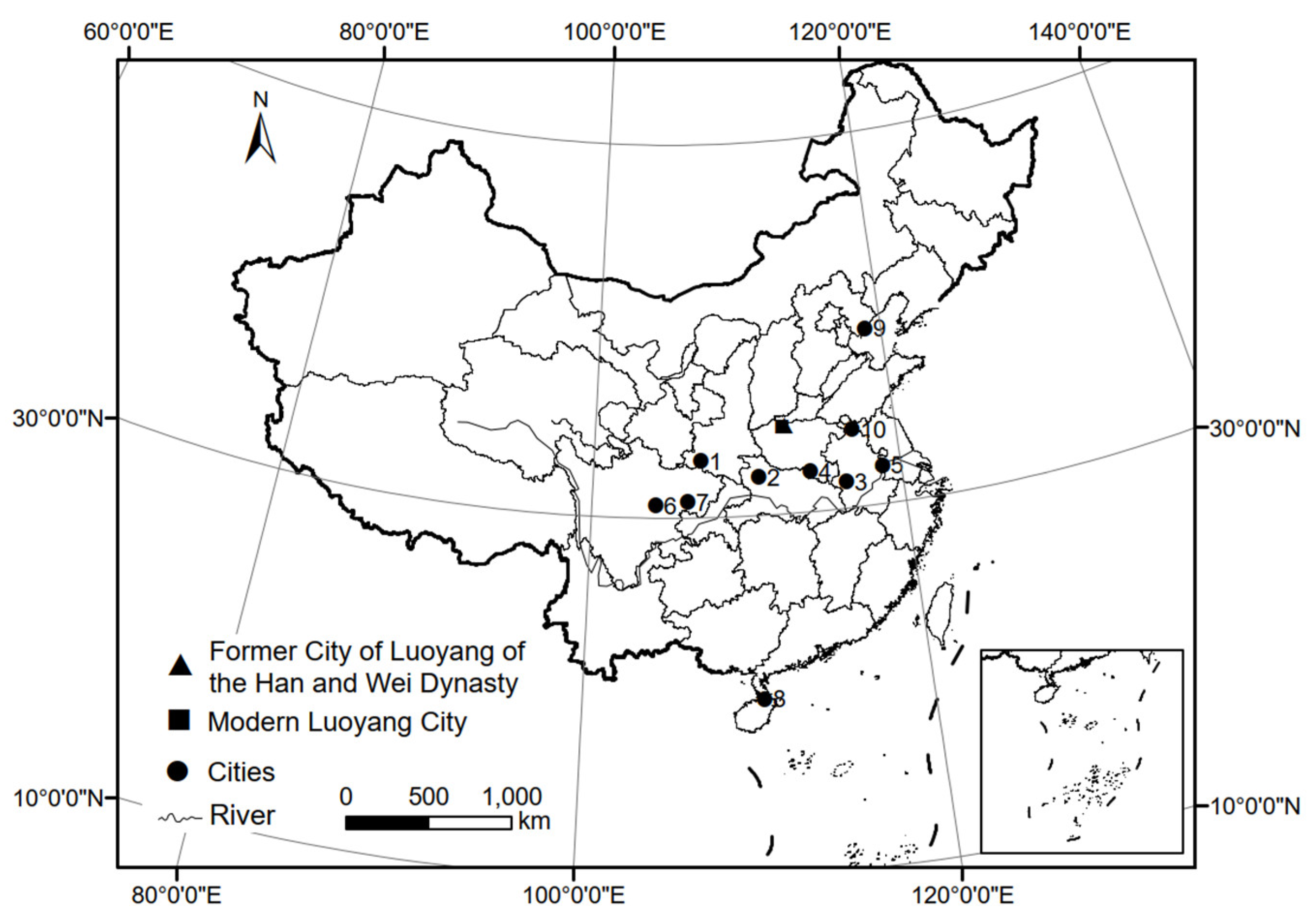

3.3. Comparison of Temperature Parameters

4. Discussion

4.1. Climate in East Asia in the 6th Century AD

4.2. Circumstantial Evidence of the Climate in East Asia in the 6th Century AD

4.3. Climate Discussions in East Asia Over the Past 1.475 Millennia

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thuiller, W.; Lavorel, S.; Araújo, M. B.; Sykes, M. T.; Prentice, I. C. Climate change threats to plant diversity in Europe. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2005, 102, 8245–8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, S. Q. N.; Xu, C.; Teng, L. C.; Svenning, J. C. Long-term effects of cultural filtering on megafauna species distributions across China. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 117, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S. W.; Zhou, X.; Sachs, J. P.; Luo, W. H.; Tu, L. Y.; Liu, X. Q.; Zeng, L. Y.; Peng, S. Z.; Yan, Q.; Liu, F.; Zheng, J. Q.; Zhang, J. Z.; Shen, Y. N. Central eastern China hydrological changes and ENSO-like variability over the past 1800 yr. Geology 2021, 49, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, A. F.; Zhang, H. X.; Liu, W. G.; Feng, X. P.; Sun, X. S.; Yan, T. L.; Leng, C. C.; Shen, J.; Chen, F. H. Quantification of temperature and precipitation changes in northern China during the “5000-year” Chinese History. Quaternary Sci Rev 2021, 255, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Su, T.; Liu, Y. S.; Xing, Y. W.; Jacques, F. M. B.; Zhou, Z. K. Quantitative climate reconstructions of the late Miocene Xiaolongtan megaflora from Yunnan, southwest China. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 2009, 276, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y. F.; Bruch, A. A.; Mosbrugger, V.; Li, C. S. Quantitative reconstruction of Miocene climate patterns and evolution in Southern China based on plant fossils. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 2011, 304, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. Y.; Wen, Y. J.; Fang, X. Q. Changes of climate and land cover in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River over the past 2000 years. Res sci 2020, 42, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. J.; Ma, F. J.; dong, J. L.; Liu, C. H.; Liu, S.; Sun, B. N. New costapalmate palm leaves from the Oligocene Ningming Formation of Guangxi, China, and their biogeographic and palaeoclimatic implications. Hist biol 2017, 29, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbrugger, V.; Utescher, T. The coexistence approach — a method for quantitative reconstructions of Tertiary terrestrial palaeoclimate data using plant fossils. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 1997, 134, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. S.; Wang, Y. F.; Sun, Q. G. The Quantitative Reconstruction of Palaeoenvironments and Palaeoclimates Based on Plants. Chin Bul Bot 2003, 20, 430–438. [Google Scholar]

- Moine, O.; Antoine;, P.; Hatté, C.; Landais, A.; Mathieu, J.; Prud’homme, C.; Rousseau, D.-D., The impact of Last Glacial climate variability in west-European loess revealed by radiocarbon dating of fossil earthworm granules. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114, 6209-6214.

- Folland, C. K.; Rayner, N. A.; Brown, S. J.; Smith, T. M.; Shen, S. S. P.; Parker, D. E.; Macadam, I.; Jones, P. D.; Jones, R. N.; Nicholls, N.; Sexton, D. M. H. Global temperature change and its uncertainties since 1861. Geophys Res Lett 2001, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. J.; Hu, K.; Lu, P.; Mo, D. W.; Jin, Y. X.; Lü, J. Q. Difference and its palaeoclimate reason of settlement evolution between Yulin area of Shaanxi Province and Luoyang area of Henan Province around 44 Ka BP. J Palaeogeog-English 2015, 17, 841–850. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. X.; Wang, W. T.; Bai, Y. H. Changes of natural environment in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River and its causes. Acta Agro Jiangxi 2007, 19, 106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q. H.; Ma, L. J.; Liu, Q.; Ding, S. Y.; Tang, Q.; Lu, X. l. Plant species diversity and its response to environmental factors in typical river riparian zone in the middle and lower reaches of Yellow River. Chin J Eco 2015, 34, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X. Y.; Sang, Y. F. , The ancient city of Luoyang and the Han-Wei dynasty.; Zhengzhou Ancient Books Publishing House: Zhengzhou, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. L.; Mao, Y. G. , Archaeological Integration of Luoyang: Qin, Han, Wei, Jin and North and South Dynasties.; Beijing Library Press: Beijing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. L.; Han, S. P. , Archaeological Integration of Luoyang: Sui, Tang, Five Dynasty and Song.; Beijing Library Press: Beijing, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Luoyang Archaeological Working Group, I. o. A. Chinese Academy of Sciences, Luoyang, Preliminary Survey of Luoyang City in Han and Wei Dynasty. Archaeology 1973, 4, 198–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. R. A few questions about the historic relics of Shang Dynasty in Yanshi and the Erlitou site. Archaeology 1996, 5, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S. W. Formation and Evolution of the Inner and Outer Coffin System. The Journal of Nankai University (Philosophy, Literature and Social Science Edition) 2014, 3, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. F., The history of Chinese tomes. Guangling Press: Yangzhou, 2009; p 1-598.

- Gao, M. Q.; Lu, L. D., Ancient Chinese Names of Plants. Elephant Press: zhengzhou, 2006; p 1-547.

- Liu, H. M.; Xia, X. F.; Li, Y. M.; Wang, L. L. Original Plants of “Algae” and Its Corresponding Plants in Historical Books and Records of China. Chin Agric Sci Bull 2017, 33, 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. M.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, X. F.; Li, Y. M. Original Plants of Celery and Its Corresponding Plant. Chin Agric Sci Bull 2016, 32, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. M.; Chang, L.; Xia, X. F.; Wang, L. L.; Han, D.; Zhong, B.; Li, Y. M. Research on the Original Plants of Scallion and Its Corresponding Plants. Chin Agric Sci Bull 2015, 31, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mosbrugger, V.; Utescher, T. The coexistence approach—a method for quantitative reconstructions of Tertiary terrestrial palaeoclimate data using plant fossils. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 1997, 134, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, F. M. B.; Shi, G.; Wang, W. Reconstruction of Neogene zonal vegetation in South China using the Integrated Plant Record (IPR) analysis. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 2011, 307, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utescher, T.; Bruch, A. A.; Erdei, B.; François, L.; Ivanov, D.; Jacques, F. M. B.; Kern, A. K.; Liu, Y. S.; Mosbrugger, V.; Spicer, R. A. The coexistence approach—theoretical background and practical considerations of using plant fossils for climate quantification. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 2014, 410, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Z.; Yue, H. B.; Yue, Z. W. High-resolution ecological reconstruction in the Yin and Shang dynasties. Cult Relics Southern China 2016, 2, 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K. Z., Fluctuations of world climate in historical times. Acta Meteor Sin, 1962, 31, 275-287.

- Lamb, H. H., Climate: present, past and future - v. 1: Fundamentals and climate now.- v. 2: Climatic history and the future. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 1979, 26, 364-365.

- Hinsch, B. Climatic change and history In China. J Asia Hist 1988, 22, 131–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, R. A.; Murray, T. J. Climates of hunger: mankind and the world’s changing weather. University of Wisconsin Press 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. C. The relationship between the migrating south of the nomadic nationalities in north china and the climatic changes. Sci Gelgra Sin 1996, 16, 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L. h. The impact of climate change on ancient chinese agriculture in historical period. Chin Agric Infor 2014, 9, 175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Q. S. , Climate change in China through the dynasties.; Science Press: Beijing, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, G.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J. On the changes of the climatic zones and the developments of the distributive areas of living beings in China during the historical periods. Chin Histl Geo 1987, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, C. X. Study on the climate in the North and South Dynasties. J Zhejiang Meteor 1987, 8, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Man, Z. M., Studies on climate change in China’s historical period. Shandong Education Press: Jinan, 2009; p 1-504.

- Wu, R. J.; Tong, G. B. Vegetation and climatic quantitative reconstruction of Longgan Lake since the past 3000year. Mar Geol & Quat Geol 1997, 17, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W. C.; Wu, R. J.; Yang, X. D.; Wang, S. M.; Wu, Y. H.; Xue, B.; Tong, G. W. The Palaeoenvironmental and Palaeoclimatic Changes of Longgan Lake since the Past 3000 Years. J Lake Sci 1998, 10, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P. D.; Mann, M. E. Climate over Past Millennia. Rev Geophys 2004, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M. E. Climate Over the Past Two Millennia. Annu Rev Earth Pl Sc 2007, 35, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T. X.; Wang, Y. F.; Hou, Y. J.; Du, N. Q.; Li, C. S. Historical natural landscape of Tongwancheng area in northern Shaanxi Province and migration rate of Mau Us Desert. J Palaeogeog-English 2004, 6, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdary, J. S.; Hu, K.; Srinivas, G.; Kosaka, Y.; Wang, L.; Rao, K. K. The Eurasian Jet Streams as Conduits for East Asian Monsoon Variability(Review). Curr Clim Change Rep 2019, 5, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Feng, J.; Wen, Z. P.; Ma., T. J.; Yang, X. Q.; Wang, C. H., Recent Progress in Studies of the Variabilities and Mechanisms of the East Asian Monsoon in a Changing Climate. Adv Atmos Sci 2019, 36, 887-901.

- Running, S. W.; Coughlan, J. C. A general model of forest ecosystem processes for regional applications I. Hydrologic balance, canopy gas exchange and primary production processes. Ecol Model 1988, 42, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciruzzi, D. M.; Loheide, S. P. Groundwater subsidizes tree growth and transpiration in sandy humid forests. Ecohydrology 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ancient names of plants | Names of modern taxa | Scientific Names | Plant Features | Figures |

| Pine(松) | Pines | Pinus sp. | Stem surface splitting into patches needle-shaped leaves.Flowers unisexual, monoecious.Bearing fruit in autumn.Seed maturation period 1-2 years. | |

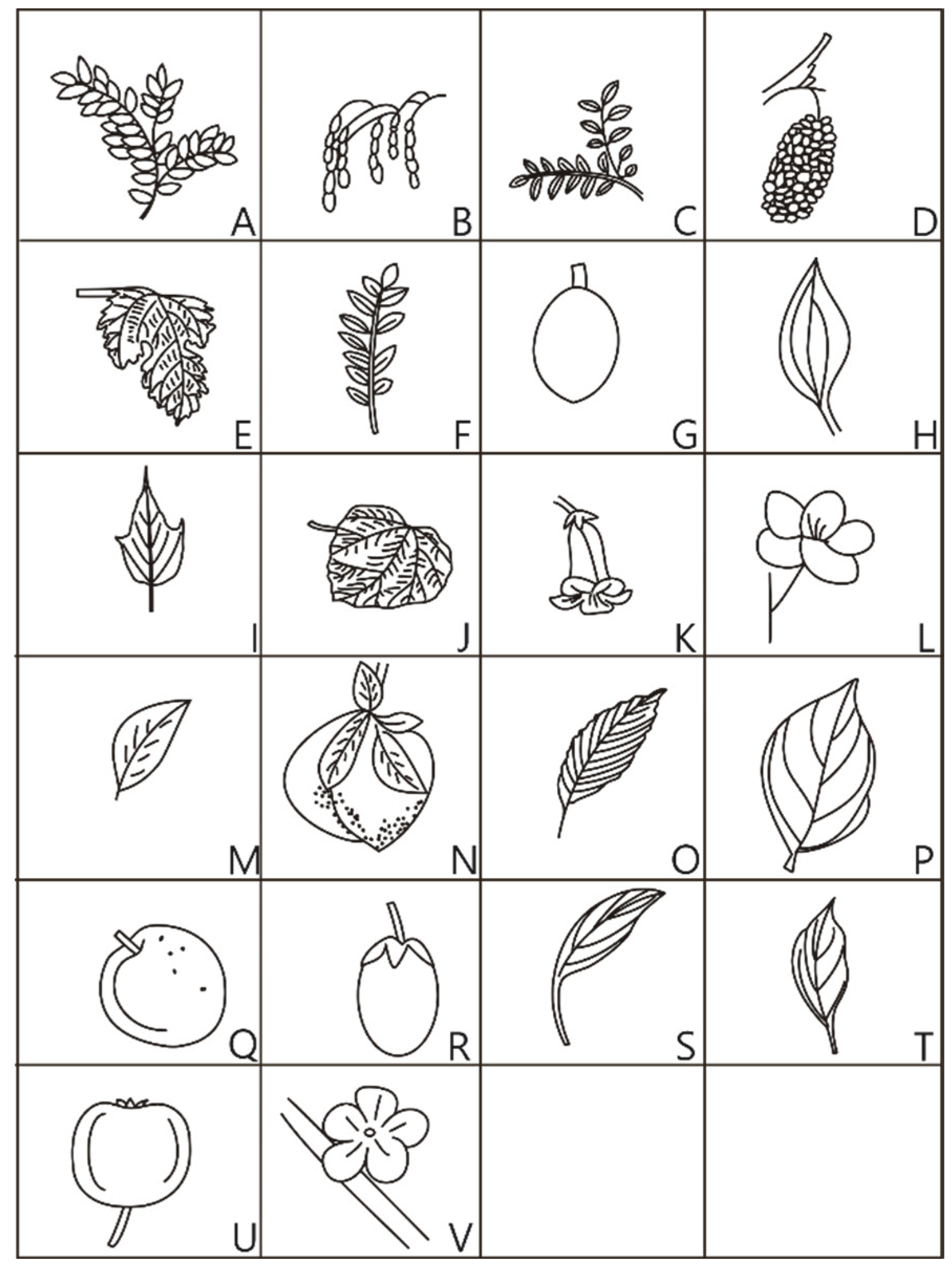

| Huai(槐) | Pagoda Tree | Styphnolobium japonicum (L.) Schott | Leaf opening at day and closing at night. Leaflets ovate-oblong or ovate-lanceolate opposite.Flowers small, yellow, florets forming panicles.Legume.3-6 seeds/fruit | Figure 2A, 2B, 2C |

| Sang(桑) | Mulberry | Morus alba var. alba Linn. | Leaves large as palms, blade margin serrate, sometimes notched, apex acuminate. Polygamous fruit, ovate-ellipsoid | Figure 2D, 2E |

| Bai(柏) | Cypress | Cupressus funebris Endl | Flowers very small and contain a lot of pollen. The fruit forms a globular fruit that dehiscences at maturity and contains several seeds. Seed size like wheat seeds | |

| Cheng(柽) | Tamarisk | Tamarix sp./Myricaria sp. | Stem surface red. Tiny leaves. Inflorescence spike-like, flesh-red, about 10 cm in length | |

| Zhi(枳) | Trifolia Orange | Cirtus sp. | Deciduous shrub or small tree with thick thorns on the stem, compound leaves, white flowers Fruit small spherical with sour taste | |

| Yang | Poplar | Populus tomentosa Carr. | Deciduous trees. Leaves long and broadly shaped. Dioecious, with spikes of flowers in spring. Seeds with flocculent hairs at the tip | |

| Niu Jin Shu / Beef Tendon Tree | Vaccinium | Vaccinium bracteatum Thunb. | Stem surface with red coloration. Leaves resembling apricot leaves but pointed, light-colored. The flowers are like neem and the stamens are white. stem juice can be used to make dark rice. | |

| Gou Gu /Dog Bone Trss | Ilex | Ilex cornuta Lindl. et Paxt. | Woody plants, shrubs or small trees. Surface of the stem with longitudinal furrows. Leaves ovate or ovate-lanceolate, margin with 1-3 pairs of sinuate spines. Spines ca. 3 mm in length | |

| Jiu Tree / Liquor Tree | Cocos | Cocos nucifera L. | Plants tall, tree-like. Stems stout, with annular leaf scars. Leaves pinnatisect. Inflorescences axillary, much branched; spathe fusiform, thickly woody. Fruit ovoid or subglobose, containing liquid nutrients inside. | |

| Mian Mu / Flour Wood | Arenga | Arenga westerhoutii Griffith | The part outside the pith is very hard and the pith can be processed to make starch. | |

| Gua | Sabina | Juniperus chinensis L. | Evergreen shrubs, stems erect. Leaf dimorphism, with both spiny and scaly leaves. Fruits subglobose. | |

| Chun | Toon | Toona sinensis (A. Juss.) Roem. | Deciduous trees, about ten meters tall. Compound leaves, red in young, sweet and edible. Little White Flower. Fruits were capsule, red at maturity | Figure 2F |

| Zao | Jujibe | Ziziphus jujuba Mill | woody stem . Leaf ovate-elliptic, apically obtuse, or with small apices, basally ternately veined . Fruit rectangular or oblong-ovoid, red at maturity. | Figure 2G, 2H |

| Qiu | Chinese Catalpa | Catalpa bungei C.A. Mey. | Deciduous trees Stem straight, ascending, branched at high. Leaves resembling sycamore leaves but thin and small, tri-tipped or penta pointed. Flowers small, corolla partly white. Fruit narrowly ellipsoid. | Figure 2I |

| Tong / Tung | Paulownia | Paulownia fortunei (Seem.) Hemsl. | Deciduous trees, up to 10 m. Bark Rough, with slightly white in color. Leaves rounded and large, palmately divided, with long stalks. Flowers labiate, purple or white, mainly white, in large panicles, calyx yellow-brown. Fruits were capsule, 6-10 cm length | Figure 2J, 2K |

| Tao | Peach Tree | Prunus persica L. | Deciduous sub-trees, more than 3 m tall. Leaf long oval. Flower at spring, and fruit mature in Summer. Drupe broadly ovoid, densely pubescent; drupe firmly woody; seeds compressed ovate-cordate. | Figure 2L, 2M, 2N |

| Yu | Elm | Ulmus pumila L. | First grows elm pods, then leaves. Elm pods. Samara suborbicular, white at maturity, many samara densely arranged together. | Figure 2O |

| Li(李)(01) | Plum tree | Prunus salicina Lindl. | Deciduous trees. Leaves ovate, apical, denticulate. Flowers white, with five petals. Fruits with a lot of water, large and round, skin with fine points. | Figure 2P, 2Q |

| Nai | Nane Tree | Malus pumila Mill. | Perennial trees, with woody stems. Leaves broadly ovate, apex acute. Red and white flowers with five petals. Fruit depressed globose, calyx depressed, sepals persistent, petiole thick and short. | Fig, 2T, 2U, 2V |

| Li(梨)(02) | Pear Tree | Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd. | Deciduous trees. Leaves elliptic-obovate. Flowers white, with five petals. Fruit rounded | |

| Qi | Chinese Wolfberry | Lycium chinense Miller | Deciduous small shrubs. Leaves long elliptic, alternate. Small red and purple flowers in June and July, flowers borne in leaf axils. Fruit red, ovoid and pointed, slightly elongated, like a date pit. | Figure 2R, 2S |

| Zi | Catalpa | Catalpa ovata G. Don | Deciduous trees, straight stem, branched in high places . Ovate-oblong, or triangular-ovate. Flowers small, purple-red. Fruit linear. |

| Ancient names of plants | Scientific Names for the plants |

| Pine Tree | Pinus sp. |

| Huai | Styphnolobium japonicum (L.) Schott |

| Sang | Morus alba var. alba Linn. |

| Bai | Cupressus funebris Endl |

| Cheng | Tamarix sp./Myricaria sp. |

| Zhi | Cirtus sp. |

| Yang | Populus tomentosa Carr. |

| Niu Jin Shu / Beef Tendon Tree | Vaccinium bracteatum Thunb. |

| Gou Gu /Dog Bone Tree | Ilex cornuta Lindl. et Paxt. |

| Jiu Tree / Liquor Tree | Cocos nucifera L. |

| Mian Mu / Flour Wood | Arenga westerhoutii Griffith |

| Gua | Juniperus chinensis L. |

| Chun | Toona sinensis (A. Juss.) Roem. |

| Zao | Ziziphus jujuba Mill |

| Qiu | Catalpa bungei C.A. Mey. |

| Tong / Tung | Paulownia fortunei (Seem.) Hemsl. |

| Tao | Prunus persica L. |

| Yu | Ulmus pumila L. |

| Li (01) | Prunus salicina Lindl. |

| Nai | Malus pumila Mill. |

| Li(02) | Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd. |

| Qi | Lycium chinense Miller |

| Zi | Catalpa ovata G. Don |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).