Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

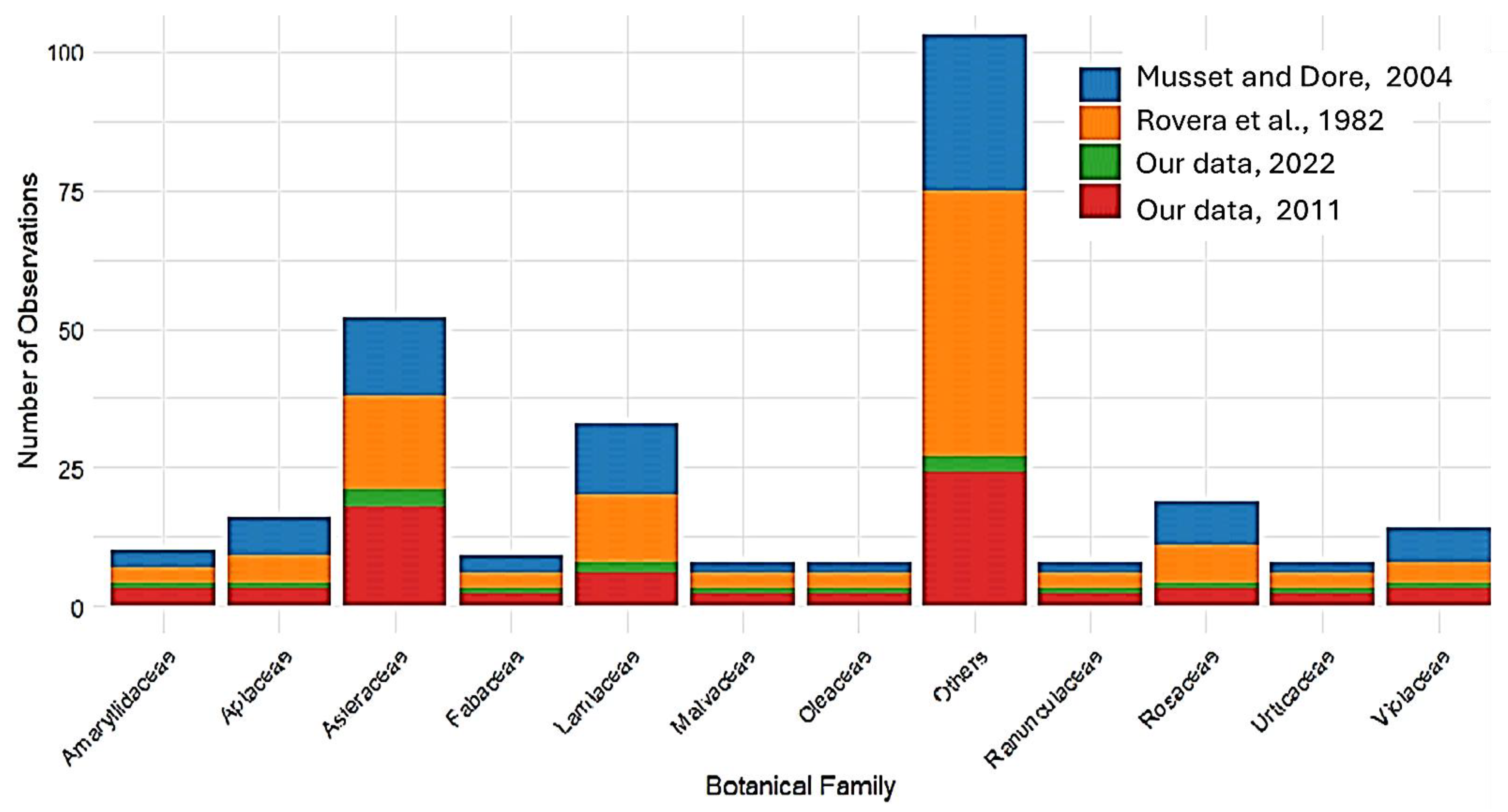

2.1. Wild Plants Across the Southern Occitan Alps

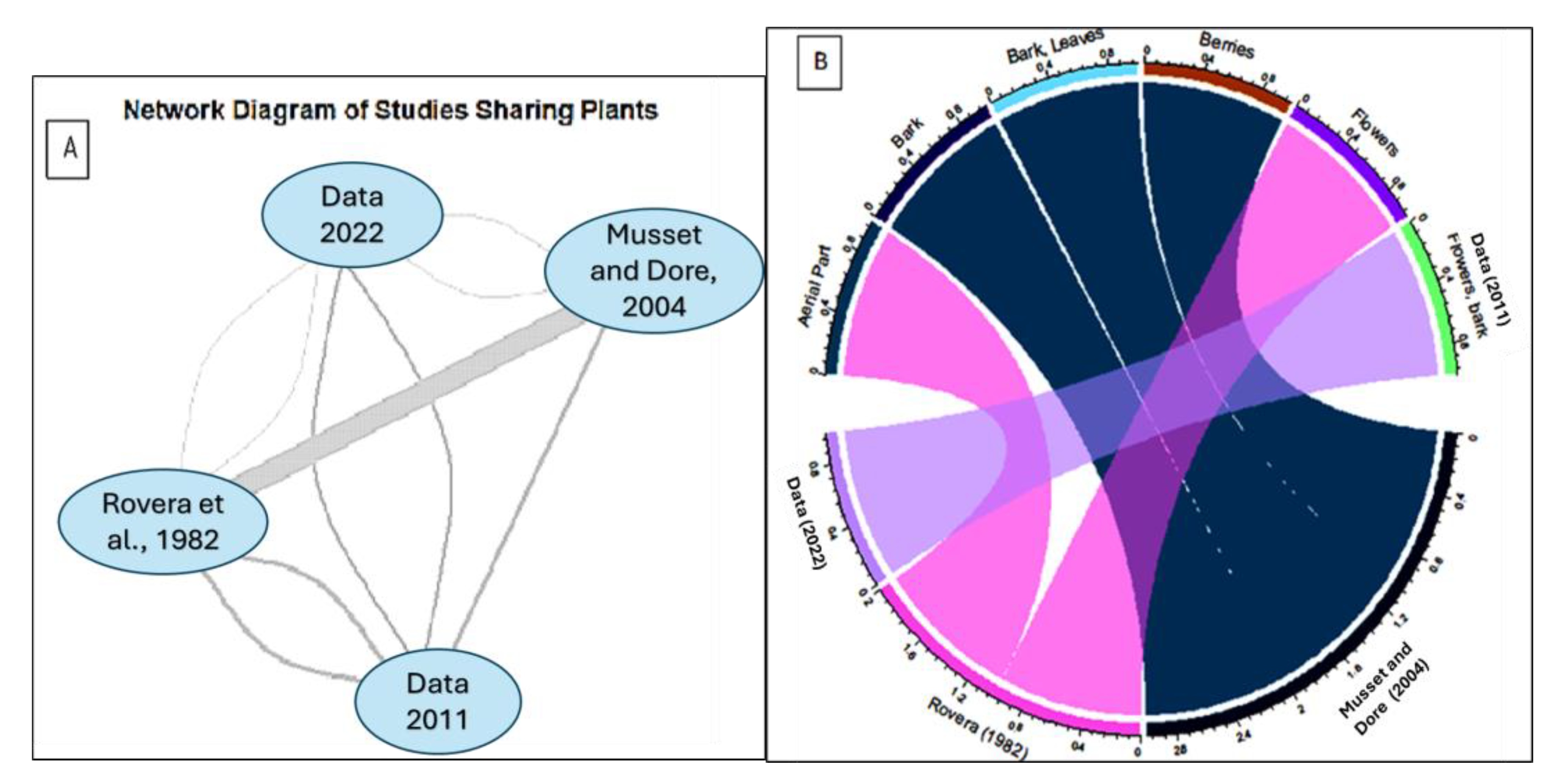

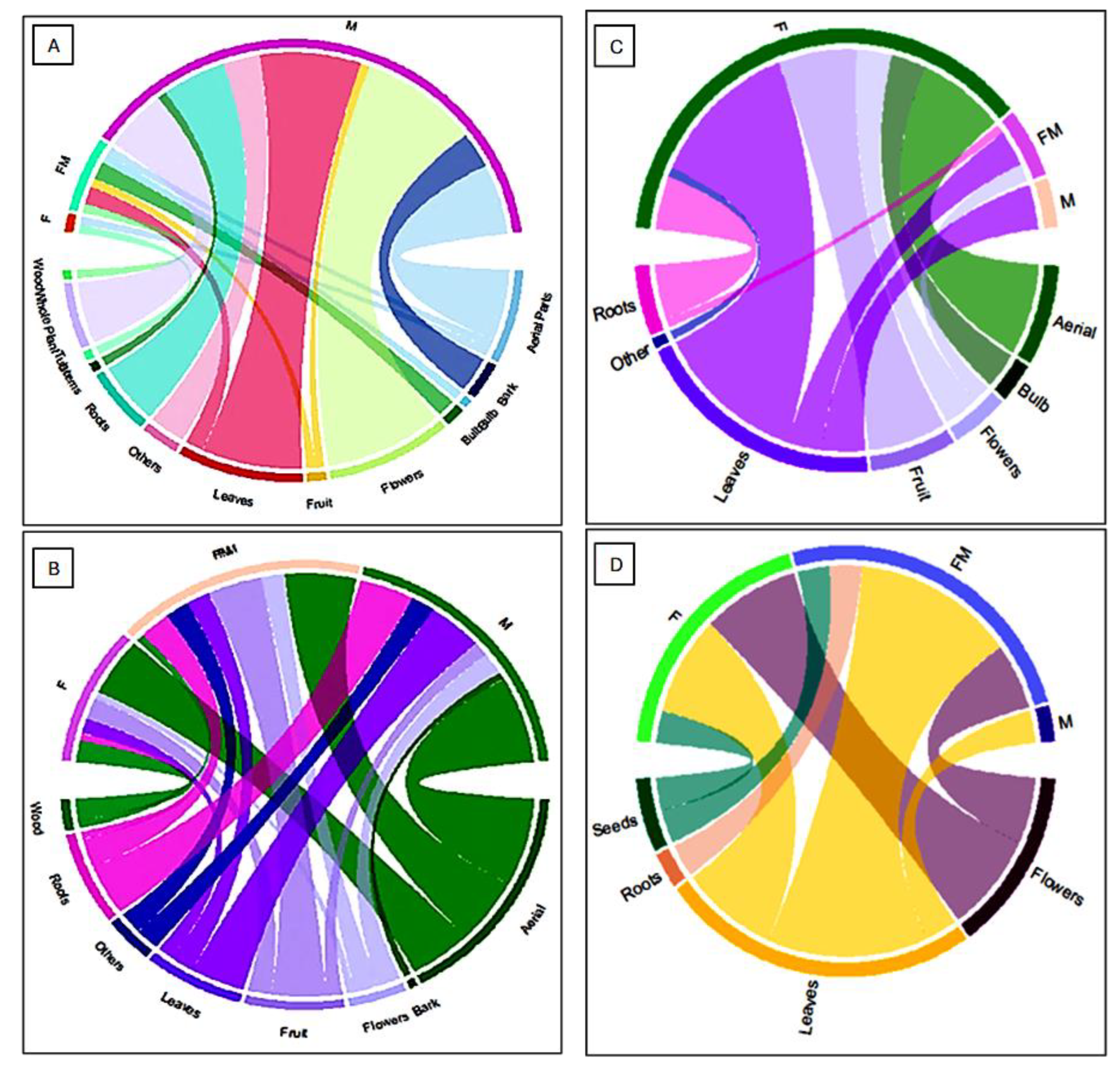

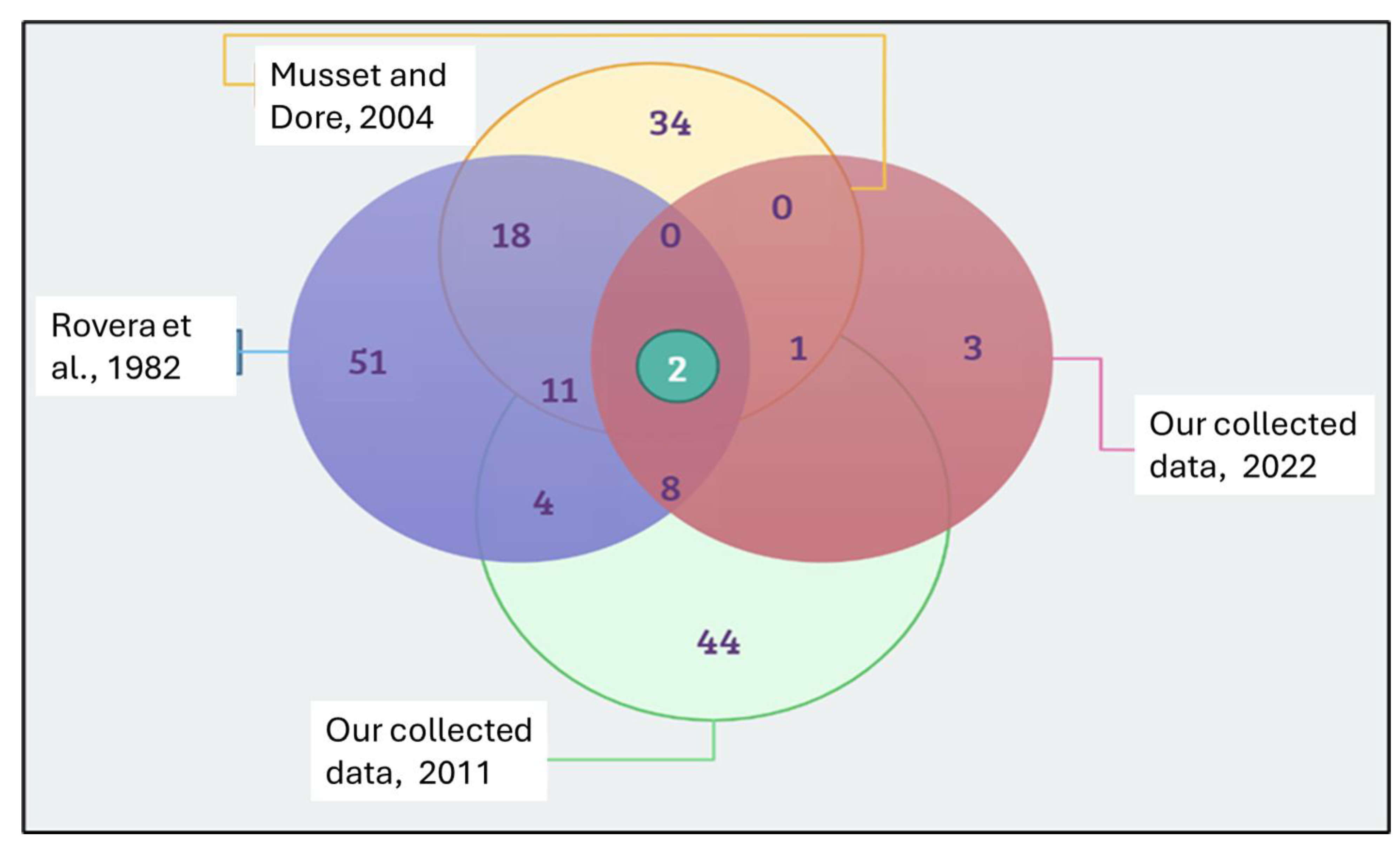

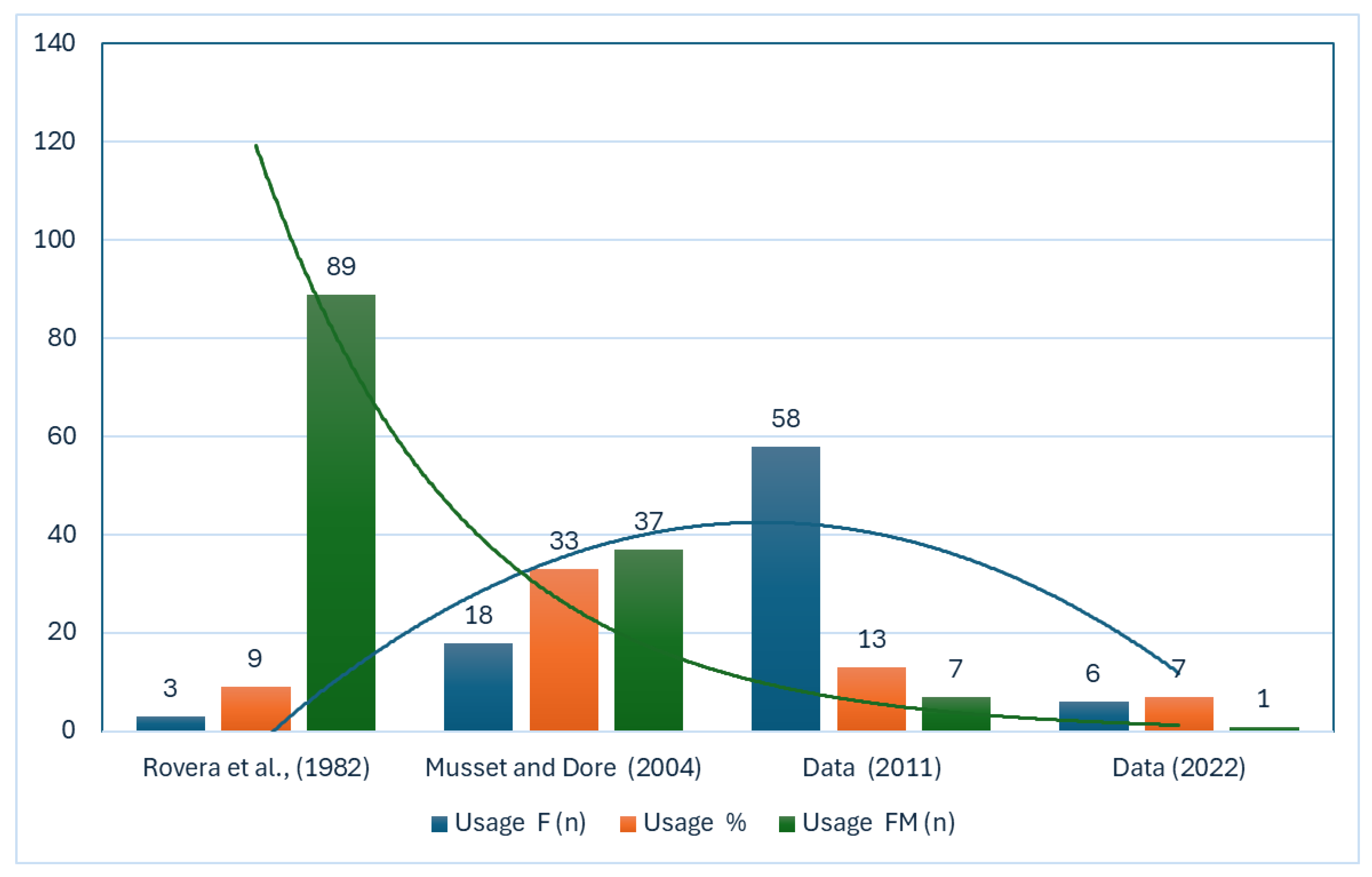

2.2. Shifts in Traditional Plant Knowledge, Usage, and Biodiversity Across Data Sites in the Southern Occitan Alps

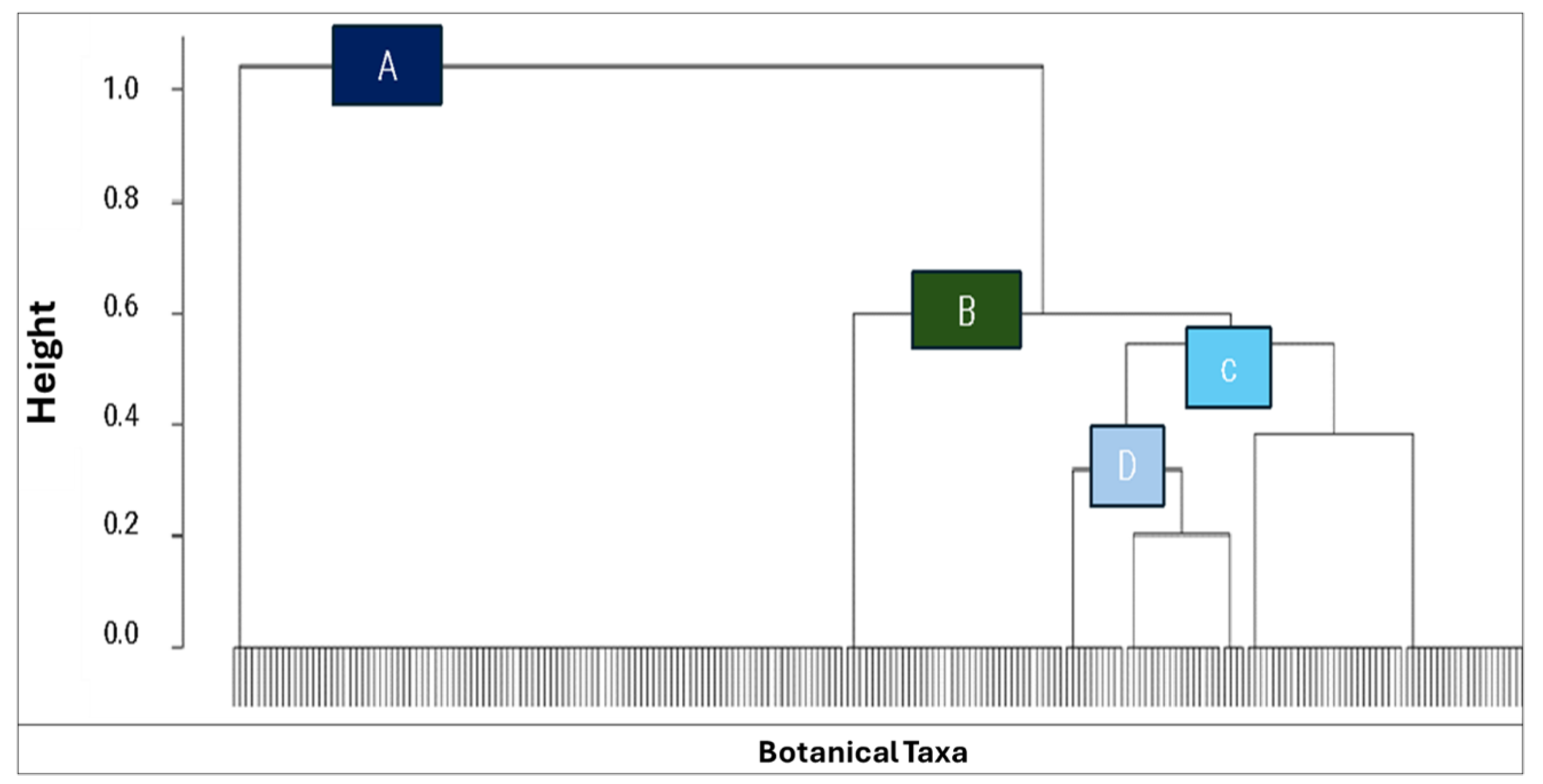

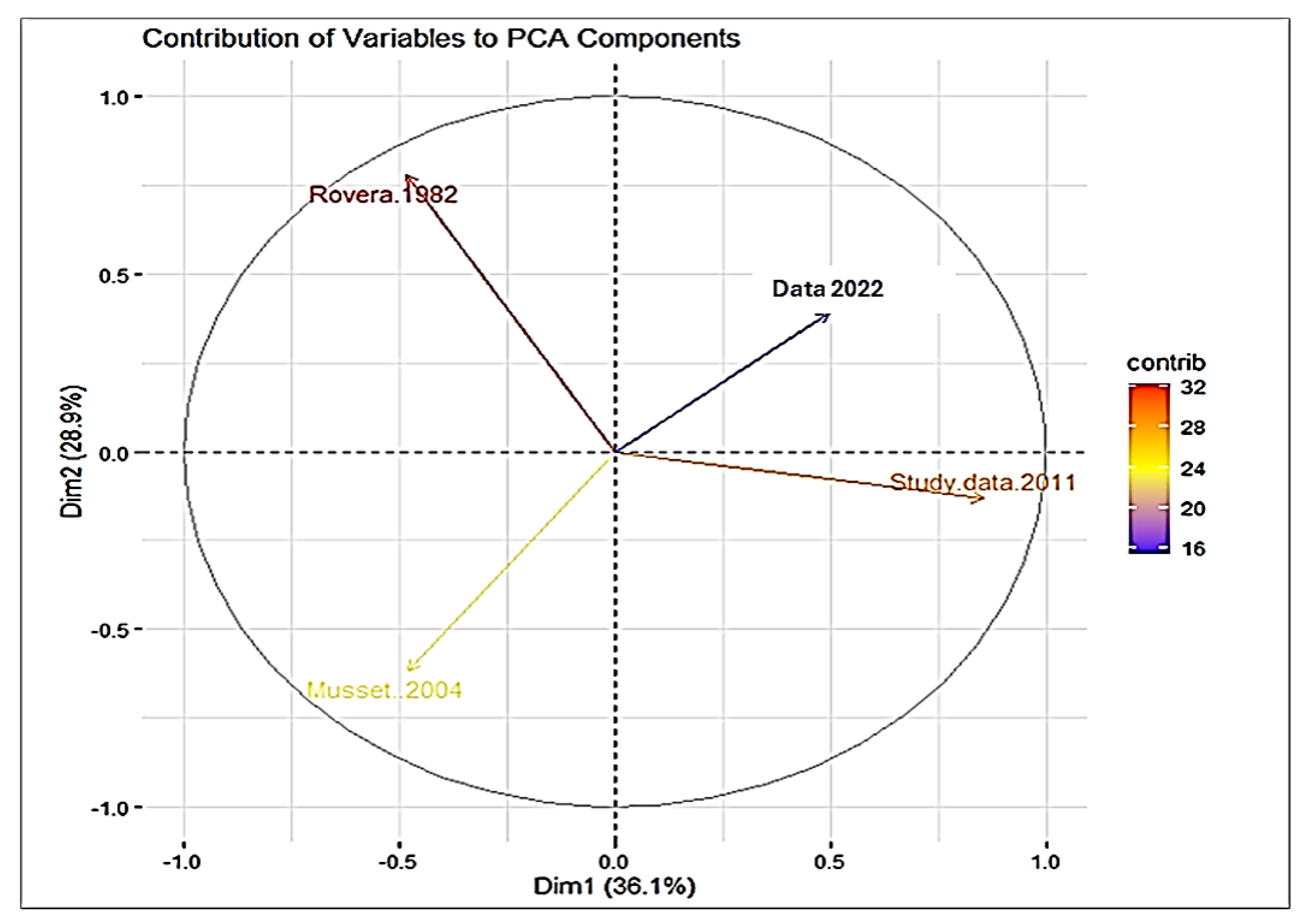

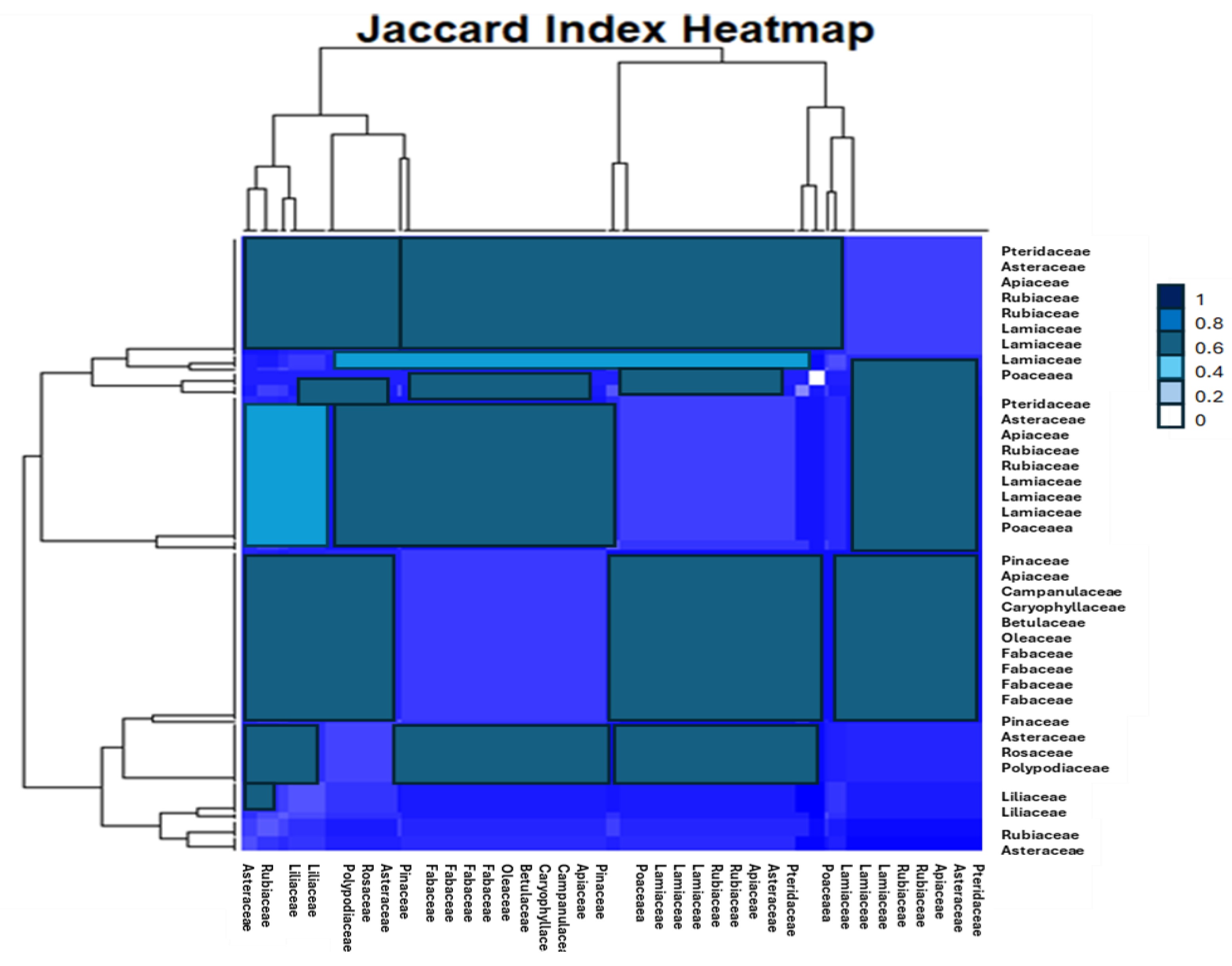

2.3. Patterns, Similarities, and Knowledge Dynamics: A Comparative Analysis Through Heatmaps, Dendrograms, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.4. Factors Influencing Botanical Diversity: Insights from Logistic Regression Analysis

| Explanatory Variables | Category | Coefficients | Odds Ratios | Std. Error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude (m) | 600-1600 | 0.8 | 2.22 | 0.3 | 0.002 |

| 1600-2400 | 0.45 | 1.57 | 0.25 | 0.048 | |

| 2400–3031 | 0.1 | 1.11 | 0.32 | 0.724 | |

| Temperature Average (°C) | 5 to 12°C | 0.3 | 1.35 | 0.28 | 0.223 |

| 7 to 13°C | -0.1 | 0.9 | 0.27 | 0.74 | |

| Precipitation Average (mm) | 1400-1600 | -0.2 | 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.511 |

| 1200-1400 | -0.5 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.151 | |

| Age Range (years) | 71-75 | 0.85 | 2.34 | 0.3 | 0.004 |

| 30-80 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.22 | 0.441 | |

| Data Source | Interviews | 0.6 | 1.82 | 0.35 | 0.09 |

| Herbarium | 0.25 | 1.28 | 0.4 | 0.517 |

3. Discussion

3.1. Resilience and Change Wild Plants in the Southern Occitan Alps

3.2. Ecological and Socio-Economic Drivers of Plant Knowledge and Diversity

3.3. Limitations of the Data

4. Materials and Methods

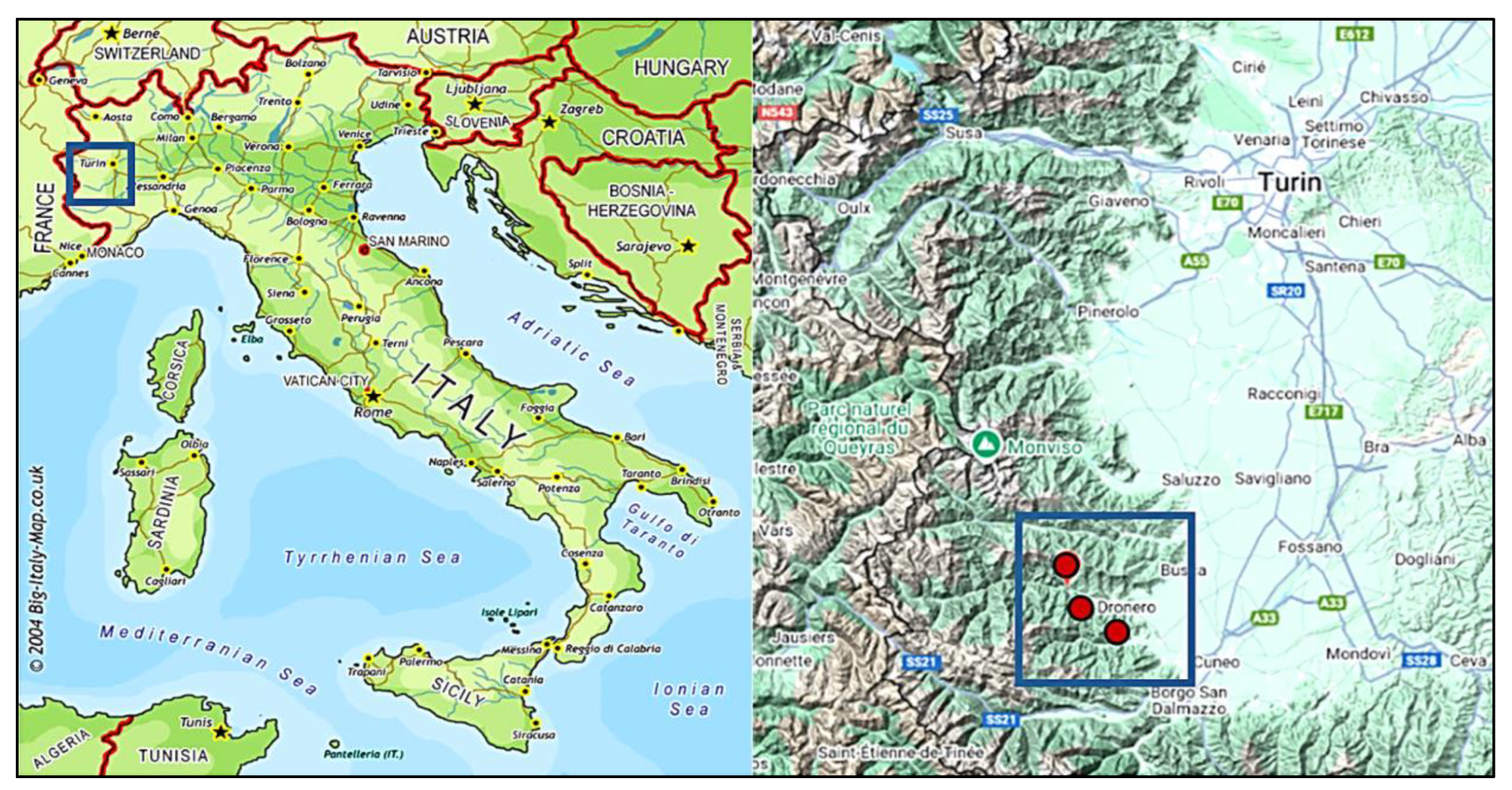

4.1. Data Area

4.2. Fieldwork and Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

- p is the probability of the event occurring (e.g., presence of a botanical taxa).

- β0 is the intercept (constant term).

- βi are the coefficients for each explanatory variable.

- Xi are the explanatory variables (altitude, temperature, precipitation, age range, and data source).

- Altitude1, Altitude2, and Altitude are the dummy variables for the three levels of Altitude (600-1,600m, 1600-2,400m, and 2,400–3,031m).

- Temperature1 and Temperature are the dummy variables for the two levels of Temperature Average (5 to 12°C and 7 to 13°C).

- Precipitation 1 and Precipitation 2 are the dummy variables for the two levels of Precipitation Average (1400-1600mm and 1200-1400mm).

- Age1and Age2 are the dummy variables for the two levels of Age Range (71-75 years and 30-80 years).

- Data Source has two levels: Interviews and Herbarium. Substituting the Coefficients

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sulaiman, N.; Zocchi, D.M.; Borrello, M.T.; Mattalia, G.; Antoniazzi, L.; Berlinghof, S.E.; Bewick, A.; Häfliger, I.; Schembs, M.; Torri, L.; et al. Traditional Knowledge Evolution over Half of a Century: Local Herbal Resources and Their Changes in the Upper Susa Valley of Northwest Italy. Plants 2024, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, A.; Avanza, G. ICH in the South-Western Alps. Empowering Communities through Youth Education on Nature and Cultural Practices.; 2020.

- Burns, R.K. The Circum-Alpine Culture Area: A Preliminary View. Anthropol. Q. 1963, 36, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Khan, S.M. Traditional Ecological Knowledge Sustains Due to Poverty and Lack of Choices Rather than Thinking about the Environment. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2023, 19, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Cantalice, A.S.; Oliveira, D.V.; Oliveira, E.S.; dos Santos, E.B.; dos Santos, F.I.R.; Soldati, G.T.; da Silva Lima, I.; Silva, J.V.M.; Abreu, M.B.; et al. Why Is Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) Maintained? An Answer to Hartel et al. (2023). Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abildtrup, J.; Audsley, E.; Fekete-Farkas, M.; Giupponi, C.; Gylling, M.; Rosato, P.; Rounsevell, M. Socio-Economic Scenario Development for the Assessment of Climate Change Impacts on Agricultural Land Use: A Pairwise Comparison Approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hatmi, S.; Lupton, D.A. Documenting the Most Widely Utilized Plants and the Potential Threats Facing Ethnobotanical Practices in the Western Hajar Mountains, Sultanate of Oman. J. Arid Environ. 2021, 189, 104484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, D.E. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): A Comprehensive Guide. Available online: https://sigmaearth.com/traditional-ecological-knowledge-tek-a-comprehensive-guide/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Casi, C.; Guttorm, H.; Virtanen, P. Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Situating Sustain. Handb. Contexts Concepts 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E. Alpine Ethnobotany in Italy: Traditional Knowledge of Gastronomic and Medicinal Plants among the Occitans of the Upper Varaita Valley, Piedmont. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2009, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyver, P.O.; Timoti, P.; Davis, T.; Tylianakis, J.M. Biocultural Hysteresis Inhibits Adaptation to Environmental Change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2019, 34, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Traditional Uses of Wild Food Plants, Medicinal Plants, and Domestic Remedies in Albanian, Aromanian and Macedonian Villages in South-Eastern Albania. J. Herb. Med. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.; Jackson, G.; McNamara, K.E. Climate-Driven Losses to Knowledge Systems and Cultural Heritage: A Literature Review Exploring the Impacts on Indigenous and Local Cultures. Anthr. Rev. 2023, 10, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteros-Rozas, E.; Ontillera-Sánchez, R.; Sanosa, P.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Reyes-García, V.; González, J.A. Traditional Ecological Knowledge among Transhumant Pastoralists in Mediterranean Spain. In Proceedings of the Ecology and Society; 2013; Vol. 18, p. art33.

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Maroyi, A.; Ladio, A.H.; Pieroni, A.; Abbasi, A.M.; Toledo, B.A.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Hallwass, G.; Soldati, G.T.; Odonne, G.; et al. Advancing Ethnobiology for the Ecological Transition and a More Inclusive and Just World: A Comprehensive Framework for the next 20 Years. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2024, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harisha, R.P. TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE (TEK) AND ITS IMPORTANCE IN SOUTH INDIA: PERSPECIVE FROM LOCAL COMMUNITIES. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2016, 14, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A Review of the Global Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Sustainable Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattoni, C.; Ianni, E.; Geneletti, D.; Zatelli, P.; Ciolli, M. Landscape Changes, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Future Scenarios in the Alps: A Holistic Ecological Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Sharma, R.K.; Babu, S.; Bhatnagar, Y.V. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Contemporary Changes in the Agro-Pastoral System of Upper Spiti Landscape, Indian Trans-Himalayas. Pastoralism 2020, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrhmoun, M. Old Plants for New Food Products? The Diachronic Human Ecology of Wild Herbs in the Western Alps. Press 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa; Furusawa, T. Changing Ethnobotanical Knowledge.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2016; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rovera, L. ; Lomagno Caramello; Lomagno P.A.; Piervtton, R. La Fitoterapia Popolare Nella Valle Maira. Corso di laurea in scienze naturali., Università degli studi di Torino, Facoltà di Scienze MFN, 1982.

- Musset, D.; Dore, D. La Mauve et l’erba Bianca. Une Introduction Aux Enquêtes Ethnobotaniques Suivie de l’inventaire Des Plantes Utiles Dans La Vallée de La Stura. Un’introduzione Alle Indagini Etnobotaniche Seguita Dall’inventario Delle Piante Utili Nella Valle Della Stura. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, K.L. “Where Our Women Used to Get the Food”: Cumulative Effects and Loss of Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Practice; Case Data from Coastal British ColumbiaThis Paper Was Submitted for the Special Issue on Ethnobotany, Inspired by the Ethnobotany Symposium Organized by Alain Cuerrier, Montreal Botanical Garden, and Held in Montreal at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the Canadian Botanical Association. In Proceedings of the Botany; February 2008; Vol. 86; pp. 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, N.; Aziz, M.A.; Stryamets, N.; Mattalia, G.; Zocchi, D.M.; Ahmed, H.M.; Manduzai, A.K.; Shah, A.A.; Faiz, A.; Sõukand, R.; et al. The Importance of Becoming Tamed: Wild Food Plants as Possible Novel Crops in Selected Food-Insecure Regions. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, J.M. Changing Trends in Dietary Pattern and Implications to Food and Nutrition Security in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 3, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Sulaiman, N.; Sõukand, R. Chorta (Wild Greens) in Central Crete: The Bio-Cultural Heritage of a Hidden and Resilient Ingredient of the Mediterranean Diet. Biology 2022, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Tardío, J.; Reyes-García, V. Trends in Wild Food Plants Uses in Gorbeialdea (Basque Country). Appetite 2017, 112, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarbà, C.; Allegra, V.; Silvio Zarbà, A.; Zocco, G. ; 1 Department Agriculture, Food and Environment (Di3A), University of Catania, Catania, Italy; 2 Agronomist: Research collaborator Di3A, Catania, Italy Wild Leafy Plants Market Survey in Sicily: From Local Culture to Food Sustainability. AIMS Agric. Food 2019, 4, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, T.; Ide, Y. Global Patterns of Genetic Variation in Plant Species along Vertical and Horizontal Gradients on Mountains. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2008, 17, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xiong, Q.; Luo, P.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, X.; Lin, B. Direct and Indirect Effects of Environmental Factors, Spatial Constraints, and Functional Traits on Shaping the Plant Diversity of Montane Forests. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaobo, Z.; Huang, F.; Hao, L.; Zhao, J.; Mao, H.; Zhang, J.; Ren, S. The Socio-Economic Importance of Wild Vegetable Resources and Their Conservation: A Case Data from China. Kew Bull. 2010, 65, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Cadotte, M.W.; Isaac, M.E.; Milla, R.; Vile, D.; Violle, C. Regional and Global Shifts in Crop Diversity through the Anthropocene. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0209788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, J.A.; Puentes, J.P. Medicinal and Aromatic Species of Asteraceae Commercialized in the Conurbation Buenos Aires-La Plata (Argentina). In Proceedings of the Ethnobiology and Conservation; September 1 2013; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, S.; Giacalone, D. Barriers to Consumption of Plant-Based Beverages: A Comparison of Product Users and Non-Users on Emotional, Conceptual, Situational, Conative and Psychographic Variables. FOOD Res. Int. 2021, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleš, I.; Pedisić, S.; Zorić, Z.; Elez-Garofulić, I.; Repajić, M.; You, L.; Vladimir-Knežević, S.; Butorac, D.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. The Medicinal and Aromatic Plants as Ingredients in Functional Beverage Production. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 96, 105210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, L.; Hassan, M.; Amjad, M.S.; Mir, R.A.; Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Bussmann, R.W.; Binish, Z. Ethnobotanical Insights into Medicinal and Culinary Plant Use: The Dwindling Traditional Heritage of the Dard Ethnic Group in the Gurez Region of the Kashmir Valley, India. Plants 2023, 12, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friday, C.; Scasta, J.D. Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Ethnobotany for Wind River Reservation Rangelands. Ethnobiol. Lett. 2020, 11, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, A.; Mascino, L. Valades Ousitanes, Architettura e Rigenerazione. In Proceedings of the ARCHALP; August 7 2020; Vol. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mattalia, G.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Traditional Uses of Wild Food and Medicinal Plants among Brigasc, Kyé, and Provençal Communities on the Western Italian Alps. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISE (International Society of Ethnobiology) The ISE Code of Ethics. Available online: https://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

| Botanical Taxa | Family | Rovera (1982) | Musset and Dore (2004) | Data (2011) | Data 2022 | Part Used | Usage | Methods of preparations and Usage | Data Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abies alba Mill. | Pinaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Wood | F | Timber, ornamental purposes | Musset and Dore(2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Sap | M | The sap can be used in tinctures or syrups for respiratory issues or as a topical antiseptic. | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Abies grandis (Douglas ex D.Don) Lindl. | Pinaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Wood | F | Timber, ornamental purposes | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Abies nordmanniana (Steven) Spach | Pinaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Wood | F | Timber, ornamental purposes | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Acacia spp. | Fabaceae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Flowers, bark | F | Used in fritters, omelets, and as flavoring. Only white or pink flowers used. | Stellato (2022) | |

| Achillea herba-rotta All. | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial Part | M | Decoction or tea. Drink 1-2 cups per day. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Achillea millefolium L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Herbal remedy, anti-inflammatory | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Aconitum napellus L. | Ranunculaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots, Leaves | M | Medicinal uses, toxicity | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Adiantum capillus-veneris L. | Pteridaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Treats respiratory issues | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Aesculus hippocastanum L. | Sapindaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Seeds | M | Medicinal (for circulation) | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Agrimonia eupatoria L. | Rosaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Herbal teas and infusions | Data (2011) | |

| Alliaria petiolata (M.Bieb.) Cavara & Grande | Brassicaceae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Leaves, flowers, roots | FM | Used as broccoletti or in pasta. Seeds used to make a mustard-like sauce. | Data (2022) | |

| Allium cepa L. | Amaryllidaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bulb | FM | Raw or cooked as food; used in folk medicine for colds, coughs, and as an antibacterial. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Allium porrum L. | Amaryllidaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, bulbs | FM | Consumed as a vegetable in cooking; also used in herbal teas for its medicinal properties. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Allium sativum L. | Amaryllidaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bulb | FM | Eaten raw or cooked, or used in oils or tinctures for its antibacterial, antiviral, and cardiovascular benefits. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Allium schoenoprasum L. | Alliaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Food for cows, milk becomes more bitter | Data (2011) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| Allium ursinum L. | Liliaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Leaves, bulbs | FM | Used for flavoring vegetables, salads, or dishes with fish. Flowers also used in dishes.Treats insomnia, respiratory and cardiac disorders. | Data (2011) | |

| Alopecurus pratensis L. | Poaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves and flowers | F | Used to make better cheese | Data (2011) | |

| Anemone vulgaris Miller | Ranunculaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Decoction, drink 1 small glass before meals | Rovera (1982) | |

| Angelica archangelica L. | Apiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Roots, leaves | M | Used in tinctures or teas to treat digestive issues, respiratory conditions, and as a mild sedative. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Angelica sylvestris L. | Apiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots, Leaves | M | Herbal remedy, digestive aid | Musset (2004) | |

| Antennaria dioica (L.) Gaertner | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Herb | M | Made into an infusion or poultice for treating wounds or as a diuretic. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Apium graveolens L. | Apiaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Stems | FM | Used in cooking soups, or salads and herbal medicine for digestive health and as a mild sedative. | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Arctium lappa L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Roots, Seeds | M | Herbal remedy for skin, detoxification; Root is used in decoctions or teas for detoxification, skin health, and as an anti-inflammatory. | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng. | Ericaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Urinary health, antiseptic | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Armoracia rusticana G.Gaertn., B.Mey. & Scherb. | Brassicaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Liqueur | Data (2011) | |

| Arnica montana L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, roots | M | Applied topically in ointments or tinctures for bruises, sprains, and inflammatory pain. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Artemisia absinthium L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Alcoholic beverage, or teas to treat digestive issuesappetite stimulation, and parasitic infections. | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Artemisia genipi Stechm. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | F | Liqueur production | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, flowers | M | Used in herbal liqueurs or teas for digestive support, appetite regulation, and as a stimulant. | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Artemisia glacialis L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Flowers and stems | F | Liqueur | Data (2011) | |

|

ContinuedTable 1. |

||||||||||

| Artemisia umbelliformis Lam. | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Infusion: A pinch of plant per cup of water. Drink during the day, avoid overuse. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Artemisia vulgaris L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Digestive aid, medicinal herb | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Aruncus dioicus (Walter) Fernald | Rosaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Shoots | F | Sprouts preserved in oil or in omelets. | Data (2011) | |

| Asparagus acutifolius L. | Liliaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves and stem | F | Boiled and eaten in salad. | Data (2011) | |

| Atropa belladonna L. | Solanaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots, Leaves, Berries | M | Historical medicinal use (toxic) | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Barbarea vulgaris W.T.Aiton | Brassicaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | M | Used as a diuretic. | Data (2011) | |

| Borago officinalis L. | Boraginaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Flowers | F | Cooked and used in omelets. | Data (2011) | |

| Brassica oleracea L. | Brassicaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Heated leaves with an iron or in the oven, then applied to the affected area. Apply 2-3 times a day. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Bunium bulbocastanum L. | Apiaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Bulb | F | Used as a substitute for potatoes with milk (or cream) and flour to make cakes, then baked in the oven. Or roasted on a hot stone. Also dried for the winter. | Data (2011) | |

| Clinopodium nepeta (L.) Kuntze | Lamiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Whole plant (flowering) | M | Infusion: A pinch of dried leaves per cup of water. Use compresses as needed. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Calendula arvensis L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | FM | Medicinal uses, skin care | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Calendula officinalis L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | M | Skin care, anti-inflammatory | Musset and Dore (2004) | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | F | Soups and medicinal uses as an emollient. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M | Infusion: 1-2 flowers in 1 liter of water. Apply as a compress or wash. | Rovera (1982) | ||||

| Campanula rapunculus L. | Campanulaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves and flowers | F | A liqueur called "Sanvoran" is made from it, typical of the Occitan region. | Data (2011) | |

| Capsella bursa-pastoris Medik. | Brassicaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Salads. | Data (2011) | |

| Carlina acaulis L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots | M | Medicinal purposes | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| Carlina vulgaris L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Infusion: 1 tablespoon per cup of water. Drink after meals. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Carum carvi L. | Apiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Seeds | FM | Culinary uses, digestive aid | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Castanea sativa Mill. | Fagaceae | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Nuts, Wood, Fruits | F | Edible nuts, timber, Roasted or boiled, sweet or salty. | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Celtis australis L. | Ulmaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Seeds | F | Oil | Data (2011) | |

| Centaurea cyanus L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infusion: Flowers in water. Use as an eyewash or compress. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Cetraria islandica (L.) Ach. | Caryophyllaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Thallus, Lichen (tallo) | M | Decoction, drink 1 glass per day | Rovera (1982) | |

| Chelidonium majus L. | Papaveraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Latex, root | M | Apply latex topically to affected areas or use decoction of root (10 cm in 1 liter of water). Drink a small cup before meals. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Chenopodium bonus-henricus L. | Amaranthaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Leaves, stems | FM | Often boiled and mixed with other vegetables. Used in a casserole with Melissa. Cooked in agnolotti, raw in gnocchi. Grows well on slopes. | Stellato (2022) | |

| Chrysojasminum odoratissimum (L.) Banfi | Oleaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction: 4-5 leaves in 2 liters of water for 30 minutes | Rovera (1982) | |

| Cicerbita alpina Wallr. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Used in salads. | Data (2011) | |

| Cichorium intybus L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Roots, Leaves | F | Poor man's coffee, used as an antidote against worms, also in salads. | Data (2011) | |

| Cinchona calisaya Wedd. | Rubiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Root | M | Decoction, drink 1 small glass after meals | Rovera (1982) | |

| Cinnamomum verum J.Presl | Lauraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bark | M | Infusion: 1 liter of water, 1 tsp thyme, 2 of burdock root, left overnight. Drink 1 cup after every meal. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck | Rutaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | FM | Fresh juice, drink the juice of 1/2 lemon daily | Rovera (1982) | |

| Cornus sanguinea L. | Cornaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Seeds | F | Oil | Data (2011) | |

| Corylus avellana L. | Betulaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Fruits | F | Oil | Data (2011) | |

| Crataegus monogyna Jacq. | Rosaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flower buds with leaves | M | Decoction. Drink after meals. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Poaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Entire plant | M | Decoction or infusion. Drink after meals or as needed. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| Diplotaxis tenuifolia (L.) DC. | Brassicaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Leaves | F | Used raw and cooked in meats, fish, and cheeses. Flower buds used in pasta sauce with anchovies. | Data (2011) | |

| Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott | Dryopteridaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Rhizomes, Leaves | M | Traditionally used in herbal remedies | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Echium vulgare L. | Boraginaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Decoction, drink 1 glass per day | Rovera (1982) | |

| Equisetum arvense L. | Equisetaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Stem | F | Salads | Data (2011) | |

| Equisetum spp. | Equisetaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Decoction, drink 1 glass per day | Rovera (1982) | |

| Festuca rubra L. | Poaceaea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves and flowers | F | Used to improve cheese quality. | Data (2011) | |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Apiaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Used to flavor dishes and drinks, or also to make liqueurs. | Data (2011) | |

| Fragaria vesca L. | Rosaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Infusion: A handful of dried leaves in 1/2 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Fraxinus excelsior L. | Oleaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | M | Leaves used as diuretics and sudorifics. | Data (2011) | |

| Fumana ericoides (Cav.) Gand. | Cistaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infusion: 5-6 flowers in 1/2 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Galium album Mill. | Rubiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infusion: A pinch of flowers in water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Gentiana acaulis L. | Gentianaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Maceration: 20 flowers in 1 liter of red wine for 10 days | Rovera (1982) | |

| Gentiana lutea L. | Genzianaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Flowers, Roots | F | Root used after being washed, cut, and dried, commonly used in liqueurs and aromatic wines.Food for cows, milk becomes more bitter, but it’s also used for making liqueurs | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | M | Decoction: 1.5 liters of water and 15 pieces of root (4-5 cm) | Rovera (1982) | ||||

| Gentiana acaulis L. | Genzianaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Flowers | F | Food for cows, milk becomes more bitter, also used in liqueurs | Data (2011) | |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | Fabaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots | FM | Used as a sweetener and in herbal medicine | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Hedera helix L. | Araliaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction: 10-15 leaves in 1 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Helianthus spp. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Tuber | F | Eaten raw. | Data (2011) | |

| Hylotelephium telephium (L.) H.Ohba | Crassulaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts (Flowers) | M | Infuso: 1 tablespoon dried plant in ½ liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

|

ContinuedTable 1. |

||||||||||

| Humulus lupulus L. | Cannabaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | F | Digestive liqueurs made from the flowers, the sprouts are used in soups, omelets, and as a side dish for polenta. | Data (2011) | |

| Hypericum perforatum L. | Hypericaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Whole plant | M | For colds, apply to the burned area several times a day | Rovera (1982) | |

| Hyssopus officinalis L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | M | Perfumes and medicines for the lungs are made from it. | Data (2011) | |

| Juglans regia L. | Juglandaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Fruit | F | Oil | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction: 2-3 handfuls of leaves in 5-6 liters of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Juniperus communis L. | Cupressaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Berries, Roots | F | Used in cheese refining, and roots for liqueur production. | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | F | Berries used in meats, game, pork, rabbit, vegetables, pickled mushrooms. Used in liquor making, especially gin. | Stellato (2022) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | FM | Decoction (5-7 berries), soaking in wine or water, or consumed raw after meals | Rovera (1982) | ||||

| Laburnum anagyroides Medik. | Fabaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bark, young branches | M | Decoction: 50 cm of dry bark in 1 liter of water; young branches ground with vinegar for poultices | Rovera (1982) | |

| Lactuca perennis L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Edible, medicinal uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Lactuca serriola L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Salads and soups. Used as a laxative. | Data (2011) | |

| Lactuca virosa Thunb. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Leaves, stem | F | Tender leaves used in salads. Rosettes used in creams, soups, and mashed potatoes. | Stellato (2022) | |

| Lamium album L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction or used for inflammation in the genital tract | Rovera (1982) | |

| Lamium purpureum L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Used externally for treating wounds and inflammations | Rovera (1982) | |

| Lapsana communis L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Soups and omelets. | Data (2011) | |

| Larix decidua (L.) Mill. | Pinaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Wood, Resin | FM | Timber, ornamental. Applied to abscesses to promote maturation | Rovera (1982) | |

| Lathyrus oleraceus Lam. | Fabaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Fruits | F | Edible but also a bit poisonous. | Data (2011) | |

| Lathyrus sativus L. (Grass Pea) | Fabaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Dry plant (flowering) | M | Secondary use to expel the placenta. | Rovera (1982) | |

|

ContinuedTable 1. |

||||||||||

| Lathyrus tuberosus L. | Fabaceaea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Tubers and leaves | F | Leaves in salads. Tubers in soups or salads once cooked. It was also called "hunger herb" because it was used during times of extreme famine. Otherwise, it was eaten only by cows. | Data (2011) | |

| Laurus nobilis L. | Lauraceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Culinary uses, anti-inflammatory | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Lavandula angustifolia Mill. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Aromatherapy, skin care | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Lavandula stoechas L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Flowers | F | Ornamental, honey | Data (2011) | |

| Leontopodium nivale subsp. alpinum (Cass.) Greuter | Asteraceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Whole plant | M | Decoction: 3-4 flowers in 1 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Levisticum officinale W.D.J.Koch | Apiaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Stems and leaves | F | In summer, only the leaves are used, while in spring, the stem is also used. Used chopped on Castelmagno cheese cubes. | Data (2011) | |

| Lilium martagon var. martagon | Liliaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Bulb | F | Salads. | Data (2011) | |

| Linum usitatissimum L. | Linaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Seeds, Fiber | F | Fiber production, oil extraction | Musset (2004) | |

| Lupinus angustifolius L. | Fabaceaea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Fruits | F | Used as a substitute for fava beans, after being thoroughly washed to remove toxic substances. | Data (2011) | |

| Lythrum salicaria L. | Lythraceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Roots | M | Ornamental, urinary health | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Malva alcea L. | Malvaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Inflorescences, roots | M | Decoction: 1 handful in 1 liter of water; compresses applied to the legs | Rovera (1982) | |

| Malva pusilla Sm. | Malvaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts, flowers | M | Decoction or infusion; 5-6 flowers in water or 1 plant in 2-3 liters | Rovera (1982) | |

| Malva sylvestris L. | Malvaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Soothing digestive, skin care | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, flowers, and roots | FM | Raw in salads, cooked as an antispasmodic for the intestines. Roots against indigestion. Also used as a refreshing agent. Once boiled, it was used for inflammations. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, flowers | FM | Paired with herbs for fillings or omelets. Buds pickled in vinegar as a condiment.Used for cough, bronchitis, and digestive issues. In the past, used in soups for children or elderly with stomach or bronchitis issues. | Stellato (2022) | |||

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Entire plant, leaves | M | Decoction: Used for inflammation, gargles, or anti-inflammatory purposes | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Marrubium vulgare L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | M | Respiratory health, cough remedy | Musset (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Entire plant | M | Decoction: 1 plant in 5 cups of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Matricaria chamomilla | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Known for its calming properties | Musset and Dore (2004); Rovera (1982) | |

| Matricaria recutita L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Flowers | FM | Infusions | Data (2011) | |

| Melilotus officinalis (L.) Lam. | Fabaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Infusion: 3-4 leaves in 1 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Blood circulation, agricultural use | Musset and Dore (2004) | |||

| Melissa officinalis L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Leaves | FM | Calming, digestive aid | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | F | Used to give the characteristic flavor in salads. | Data (2011) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | FM | Used raw in salads, soups, omelets. Commonly used in liquors and as an aromatic ingredient.Used for depression, kidney colic, insomnia, and insect bites. | Stellato (2022) | ||||

| Mentha × rotundifolia (L.) Huds. | Labiateae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Used to flavor dishes and drinks. | Data (2011) | |

| Mentha aquatica L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Infusion: 3-4 leaves per cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Mentha piperita L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Decoction or infusion, used for digestion and colic relief | Rovera (1982) | |

| Mentha spp. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Digestive aid, culinary uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Mespilus germanica (L.) Kuntze | Rosaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | F | Edible fruit, ornamental | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Muscari botryoides (L.) Mill. | Liliaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Bulb | F | The bulb is roasted and dried for the winter. | Data (2011) | |

| Myosotis spp. | Boraginaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | F | Symbolic uses, ornamental | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Nasturtium officinale R.Br. | Brassicaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Aerial parts | FM | Likely consumed raw or prepared as an infusion for diuretic or digestive benefits | Rovera (1982) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Stems | FM | Culinary uses, detoxification | Musset and Dore (2004) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Salads, decoctions, hair growth | Data (2011) | |||

| Nepeta cataria L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | M | Cat attraction, medicinal uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Culinary uses, digestive aid | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Olea europaea L. | Oleaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | F | Olive oil production, culinary uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, oil | M | Used for treating burns, likely as oil or leaf extracts | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Onopordon acanthium L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Seeds | F | Oil | Data (2011) | |

| Origanum vulgare L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Culinary uses, medicinal uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | F | Used to flavor dishes and drinks. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Decoction, 2-3 times a day for knee application | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Oxalis acetosella L. | Oxalidaceae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Leaves, flowers | M | Leaves and stems used in soups, roasts, or to make a lemonade-like drink. Astringent, diuretic, blood purifier. Used for gastric issues, liver congestion, nephritis, skin rashes, and worms. | Stellato (2022) | |

| Papaver rhoeas L. | Papaveraceae | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Flowers | M | Soothing, medicinal | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | F | Baked to make green pies. Or in salads. | Data (2011) | |||

| Parietaria judaica L. | Urticaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Stems | M | Respiratory health, herbal remedy | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Parietaria officinalis L. | Urticaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | M | Poultice of chopped leaves; infusion with a handful of leaves in 1 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves and bulb | FM | Salads, soups, omelets. The juice was used as a diuretic and detoxifier for the urinary tract. Bulbs were eaten after being boiled twice to remove the bitter taste, then fried in slices or roasted. | Data (2011) | |||

| Pastinaca sativa L. | Apiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots | FM | Culinary uses, medicinal uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss | Apiaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | F | Infusion: 2 umbels in one cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Culinary uses, digestive aid | Musset and Dore (2004) | |||

| Peucedanum ostruthium W.D.J.Koch | Apiaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots | M | Roots must be crushed and prepared as a decoction. | Rovera (1982); Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Phyteuma orbiculare L. | Campanulaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves, inflorescences, and roots | F | Cooked and then used in omelets, roots are consumed in salads. | Data (2011) | |

| Phyteuma ovatum Honck. | Campanulaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves, inflorescences, and roots | F | Oil is made from it, or it is eaten toasted. | Data (2011) | |

| Pimpinella anisum L. | Apiaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Seeds, Leaves | FM | Used for flavoring and medicinal purposes | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Eaten with snails. The flowers are rarely used because they are laxative. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Umbels | FM | Infusion: 2 leaves or umbels in a cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Seeds, leaves | F | Fresh leaves used in soups, cheeses, and cooked vegetables. | Stellato (2022) | |||

| Pinus cembra L. | Pinaceae | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Timber, Nuts | F | Used for timber and nuts | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Seeds | F | Salads with the leaves and dried rhizome as a digestive. | Data (2011) | |||

| Pinus sylvestris L. | Pinaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Timber, Resin | F | Used for timber and resin | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Plantago lanceolata L. | Plantaginaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction or poultice for wounds and respiratory relief | Rovera (1982) | |

| Plantago major L. | Plantaginaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Seeds | M | Common herb for medicinal uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Basal leaves | M | Decoction: 2-3 roots in one cup of water; One cup in the evening | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Plantago sp. | Plantaginaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | M | Used against pimples. | Data (2011) | |

| Poa pratensis L. | Poaceaea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Flowers and leaves | F | Used to make better cheese. | Data (2011) | |

| Polygala spp. | Polygalaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots, Leaves | M | Used in traditional medicine | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Polygonum bistorta Samp. | Poligonaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | M | The leaves are used to make a powerful medicine for hemorrhoids. | Data (2011) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| Polypodium vulgare L. | Polypodiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Root | M | Decoction: a handful of root in 1 liter of water; Drink several times during the day | Rovera (1982) | |

| Polyporus officinalis (Vill.) Fr. | Polyporaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fungi | M | Decoction: Drink 1-2 cups per day. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Portulacaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Seeds | FM | Edible herb used in salads and for medicinal properties | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Primula veris L. | Primulaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Buds and leaves | FM | Used in potato flan, soups with other herbs, or in omelets. Also used as diuretics and detoxifiers. Buds pickled or with sugar. | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers & Leaves | M | Decotto: Use flowers and leaves. | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Primula vulgaris Huds. | Primulaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | FM | Used ornamentally and for medicinal teas | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Prunus avium (L.) L. | Rosaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | F | Produces edible fruit | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stems | M | - | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Prunus cerasus L. | Rosaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stems | M | - | Rovera (1982) | |

| Prunus spinosa L. | Rosaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Berries | FM | Used in jams and liqueurs | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Pulmonaria officinalis L. | Boraginaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Leaves, flowers | FM | Leaves used in fried dishes, fillings, pies, ravioli. Emollient, rich in vitamins A and C. | Stellato (2022) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | - | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Quercus robur L. | Fagaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bark | M | Decoction, drink 1 small glass after meals | Rovera (1982) | |

| Ranunculus acris L. | Ranunculaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Toxic plant often found in meadows | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bulb (sliced) | M | Decoction: 5-6 fruits in 4 liters of water; Decoction 4-5 times a day | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Rheum rhabarbarum L. | Polygonaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Stems, Roots | F | Used in cooking and desserts | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Ribes rubrum L. | Grossulariaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | F | Used in jams and desserts | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Rorippa spp. | Brassicaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Stems | FM | Culinary uses, medicinal uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Rosa canina L. | Rosaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fruit, Flowers | FM | Used for medicinal purposes and in jams | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | M | Decoction: 5-6 leaves per cup of water; Drink 2-3 times a day | Rovera (1982) | |||

|

Continued Table 1. |

||||||||||

| Rosa canina L. | Rosaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Fruits | F | Used to make sauces. Or toasted as a tea substitute. | Data (2011) | |

| Rosa moschata Herrm. | Rosaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | F | Known for its fragrant flowers | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Fragrant herb used in cooking and medicine | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction: 7-8 cm of twigs in 1 liter of water; Drink 3 times a day | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Rubus fruticosus L. | Rosaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fruit, Leaves | F | Known for its berries (blackberries) | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction: 2-3 leaves per cup of water; Drink 3 times a day | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Rubus idaeus L. | Rosaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | F | Edible fruit commonly used in jams and desserts | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Rumex acetosa L. | Polygonaceae | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Leaves, Roots | FM | A sour leafy plant often used in salads | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Rumex alpinus L. | Polygaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Rhizome and leaves | F | Baked with or without rice, seasoned with butter, cheese, and eggs to make green pies, a holiday dish. | Data (2011) | |

| Rumex crispus L. | Polygonaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Root | M | Decoction: 6-7 cm of root in 3 glasses of water; Drink 1 small glass in the morning | Rovera (1982) | |

| Rumex obtusifolius L. | Polygonaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Decoction: 4-5 leaves in 1 liter of water on an empty stomach; Drink 1 glass in the morning on an empty stomach for 15 days | Rovera (1982) | |

| Rumex patientia L. | Polygonaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Roots | M | Wild herb with medicinal properties | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Ruta graveolens L. | Rutaceae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Leaves | F | Grappa | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, flowers | F | Used in salads or with herbs to balance strong flavors. Stems used like broccoli, boiled and seasoned. | Stellato (2022) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Grappa preparation, drink 1 small glass after meals | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Salix alba L. | Salicaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Bark | M | Used for its bark's medicinal properties | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Salix spp. | Salicaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Crushed leaves used as toothpaste; Apply 2 times a day | Rovera (1982) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bark, Leaves | M | Known for its use in herbal medicine | Musset and Dore (2004) | |||

| Salvia officinalis L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Leaves | M | Decoction: 1⁄2 umbrella in 1⁄2 liter of water; Drink 1 small cup in the morning | Rovera (1982) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, flowers | FM | Flowers fried in batter, used in sauces or soups. Used in a hot drink with lemon for digestion. | Stellato (2022) | |||

| Salvia pratensis L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Omelets, salads, soups. Dried flowers used as flour to make bread. Also animal feed. | Data (2011) | |

| Sambucus nigra L. | Adoxaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Berries, Flowers | M | Immune boosting, cold remedy | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves and flowers | FM | Soups, salads, omelets. Preparation of elderberry wine. Jam is made, which has a laxative effect. Flowers are fried in batter. A liqueur is also made. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fruits | M | Wine made by pressing berries; Vulnerary (wound healing) | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Sanguisorba minor Scop. | Rosaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Decotto: a handful of flowers in 1 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Santolina chamaecyparissus L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Known for its aromatic leaves used in herbal remedies | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Saponaria officinalis L. | Caryophyllaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Roots, Leaves | M | Used traditionally to make soap | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Satureja hortensis L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | F | A culinary herb used for flavoring dishes | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Satureja montana L. | Labiateae | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Leaves | F | Adds flavor to food. | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts (Flowers) | M | Infuso: 1 tablespoon dried plant in ½ liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, flowers | F | Used with eggs, legumes, vegetables. Often added to minestrone or savory pudding in Piedmont. | Stellato (2022) | |||

| Silene vulgaris (Moench) Garcke | Cariofillaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Flowers and flowers | FM | Liqueurs, soups from cooked flowers, and green omelets baked in the oven. | Data (2011) | |

| Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Flowers and fruits | F | Cooked leaves used as a liver detoxifier. | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Seeds, leaves, flowers | FM | Tender central shoots used raw in salads. Flower receptacles can be boiled or used like artichokes. | Stellato (2022) | |||

| Solanum dulcamara L. | Solanaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Stems, Leaves | M | Known for its toxic and medicinal uses | Musset (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stem | M | Decotto: 10 cm of stem in a cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| Solanum tuberosum L. | Solanaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Tuber | F | Infuso: 1 leaf per cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Sorbus aucuparia L. | Rosaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Berries, Leaves | FM | Known for its berries and use in medicinal syrups | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Stellaria media (L.) Vill. | Caryophyllaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Liqueur | Data (2011) | |

| Tanacetum balsamita L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Used in omelets. | Data (2011) | |

| Tanacetum vulgare L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Known for its medicinal use | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves and flowers, roots | FM | Salads, condensed, coffee, leaves cooked in butter, soup with herbs, and raw in salad. Used against jaundice and gallstones. Buds were pickled and used as capers. Roots toasted as a coffee substitute. A liqueur is also made from the leaves. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Decoction: 1 liter of water, 2-3 flowers of tansy, 1 sprig of wormwood, boiled for 30 mins. | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Taraxacum officinale F.H.Wigg. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Roots, Leaves, Flowers | M | Often used in herbal remedies | Musset (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Teas, infusions, digestion, gnocchi, cheese refining, and green cakes baked in the oven. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | M | Infuso: 1 plant in 1 glass of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Teucrium chamaedrys L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | M | A medicinal plant | Musset (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Decotto: 1 glass of water with a pinch of plant | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Teucrium montanum L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | M | Used for its medicinal qualities | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Thymus serpyllum L. | Lamiaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Salads, teas, and infusions to eliminate intestinal gas and facilitate bile flow | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Used for its aromatic and medicinal properties | Musset and Dore (2004) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Decotto: handful in 1 liter of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Thymus vulgaris L. | Lamiaceae | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | FM | Commonly used in cooking and herbal medicine | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| Tilia cordata Mill. | Tiliaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Known for its calming tea | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | F | Used to flavor dishes. | Data (2011) | |||

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infuso: 1 teaspoon per cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Tragopogon pratensis L. | Asteraceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves and roots | FM | Sprouts and leaves used as vegetables, cooked or raw. Especially in soups. Used in green cakes baked in the oven. Roots eaten cooked. Used (unconsciously) against diabetes. | Data (2011) | |

| Trifolium pratense L. | Fabaceae | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | FM | Used in teas and for its medicinal properties | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | F | The bulb is roasted and dried for the winter. | Data (2011) | |||

| Tulipa sylvestri L. | Liliaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Bulb | F | Paired with roe deer, in sweets, or as a concentrate. | Data (2011) | |

| Tussilago farfara L. | Asteraceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Flowers | M | Used for cough and respiratory issues | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infuso: pinch per cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Ulmus minor Mill. | Ulmaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Bark | M | Decotto: 4-6 plants in 2 liters of water, boil for 4-5 hours | Rovera (1982) | |

| Urtica dioica L. | Urticaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Leaves, Roots | FM | Known for its nutritional and medicinal benefits | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fruits | FM | Used in omelets after being well-cooked or in soups, or even as shampoo. | Data (2011) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, roots | FM | Used in risotto and ravioli, collected when young and succulent. Diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties. | Stellato (2022) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Whole plant | M | Decotto: handful of leaves in 1% water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Urtica urens L. | Urticaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Whole plant | M | Decoction | Rovera (1982) | |

| Urena lobata subsp. lobata | Parmeliaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Thallus | M | Decoction | Rovera (1982) | |

| Vaccinium myrtillus L. | Ericaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Berries, Leaves | FM | A plant with medicinal and edible uses | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | F | Wine: fruit with abundant sugar, left in the sun or oven | Rovera (1982) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | F | Paired with venison, in desserts or as a concentrate | Data (2011) | |||

| Valerianella locusta L. | Valerianaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves | F | Salads | Data (2011) | |

| Veratrum album L. | Liliaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Whole plant | M | Not specified. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Continued Table 1. | ||||||||||

| Verbascum lychnitis L. | Scrophulariaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves, Seeds and flowers | M | Decoction: one leaf per cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |

| Verbascum thapsus L. | Scrophulariaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Traditionally used in herbal remedies | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infusion: one teaspoon of dried flowers in a cup of water | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Verbena officinalis L. | Verbenaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers, Leaves | M | Used for its medicinal properties | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Infusion | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Veronica longifolia subsp. longifolia | Scrofulariaceae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves | FM | Teas and infusions | Data (2011) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Aerial parts | M | Wine infusion, drink 1 small glass in the morning | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Veronica beccabunga L. | Scrophulariaceae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Leaves and flowers | F | Salads | Data (2011) | |

| Viola alba Besser | Violaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infusion: 2-3 flowers per cup of water, drink during the headache. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Viola biflora L. | Violaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infusion: Drink during the headache. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Viola odorata L. | Violaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Flowers, leaves | F | Used for decoration, in fritters, and in soups. Use caution as it can cause nausea. | Stellato (2022) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers and Leaves | M | Decoction: 5-6 plants in 1 liter of water, cook for 2-3 minutes. Drink after meals for astringent, small cup in the morning on an empty stomach for laxative. | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Viola tricolor L. | Violaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | FM | Used for decorative and medicinal purposes | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Flowers | M | Infusion: 2-3 plants per cup of water. Drink 2-3 small cups during the day. | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Viscum album L. | Santalaceae | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Berries, Leaves | M | Used in traditional medicine and rituals | Musset and Dore (2004) | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Leaves and Fruit | M | Infusion: A pinch of flowers per cup of water. Drink 2-3 cups during the day. | Rovera (1982) | |||

| Vitis vinifera L. | Vitaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Fruit | M | Decoction: 7-8 leaves in 1/2 liter of water. Drink small cup in the morning. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Zea mays L. | Poaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stigmas | M | Decoction: 150 gr. of stigmas in 1 liter of water. Drink 3-4 small cups during the day. | Rovera (1982) | |

| Data | Year | Location | Altitude (m) | Temperature Average (°C) | Precipitation Average (mm) | Age Range | Number of Participants | Data Source | Social and Economic Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rovera (1982) | 1982 | Val Maria | 600-1600 | 5 to 10 | 1300-1500 | 71-75 | Not determined | Direct conversation with locals, isolated area | Isolated economy and social conditions |

| Musset and Dore (2004) | 2004 | Valle Stura | 630–3031 | 5 to 12 | 1400-1600 | Various (30-80) | 24 individuals with diverse professions and roles | Interviews, herbariums, recipe books | Social/economic context needed |

| Our data from (2011) |

2011 | Valle Grana | 600-2400 | 7 to 13 | 1200-1400 | Various (25-75) | 20 individuals with diverse professions and roles (e.g., farmers, drivers, herbarium) | Herbarium, Indigenous and Allochthonous Quotes | Multiple generations across various professions (including merchants, restaurateurs, holidaymakers, and others) |

| Our data from 2022 | 2022 | Val Maira (Municipalities of Marmora, Dronero, and Acceglio, specifically the hamlet of Chiappera) | 600-1600 | 8 to 13 | 1300-1500 | Various (25-75) | 16 individuals, 3 dining establishments, and a culinary expert who has collaborated with local restaurants | Direct interviews, remote data collection, herbarium, and recipe books | Local economy is based on tourism, seasonal workers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).