Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction, Literature Review and Objectives

1.1. Kleiber’s Law and Organ Metabolic Rates

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

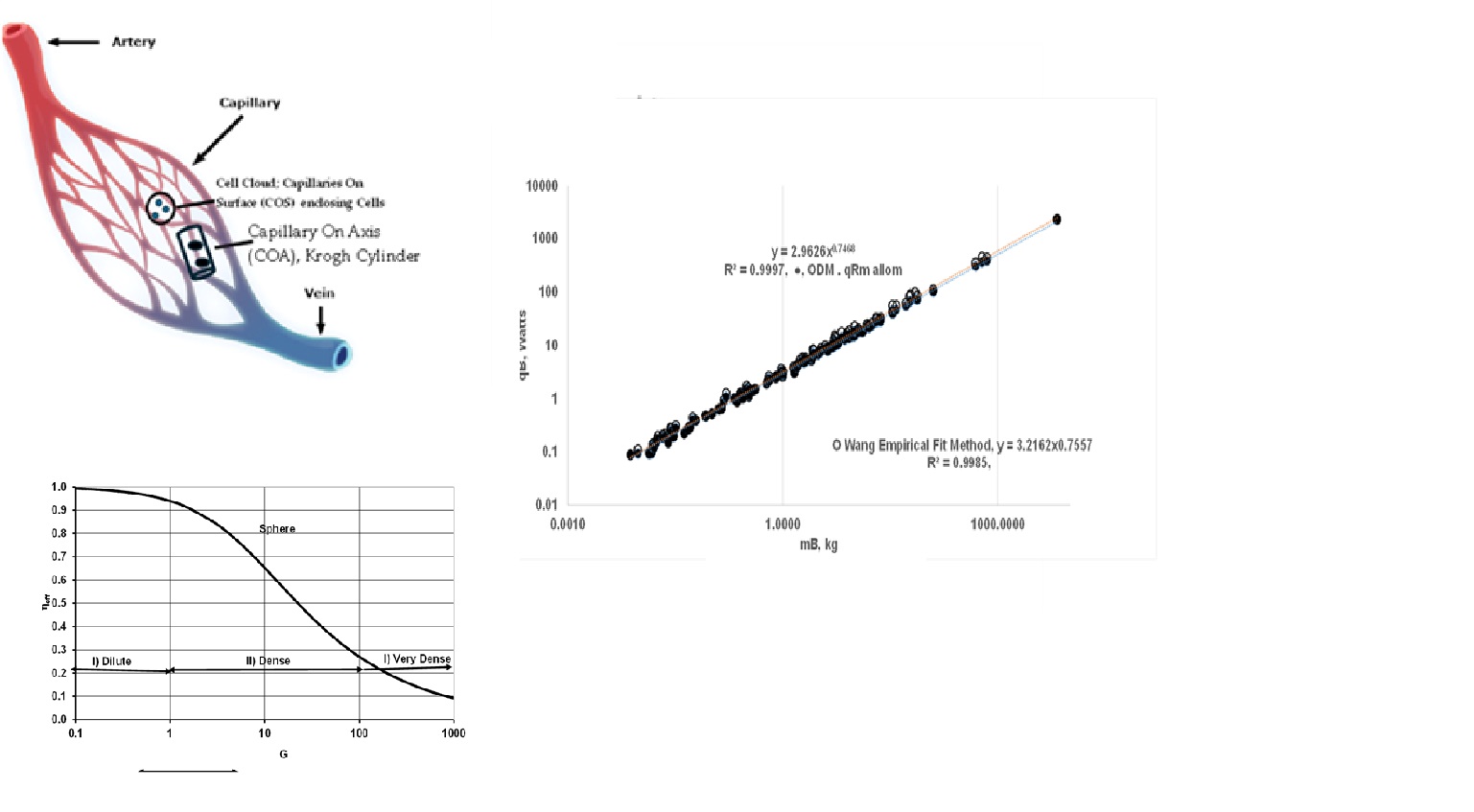

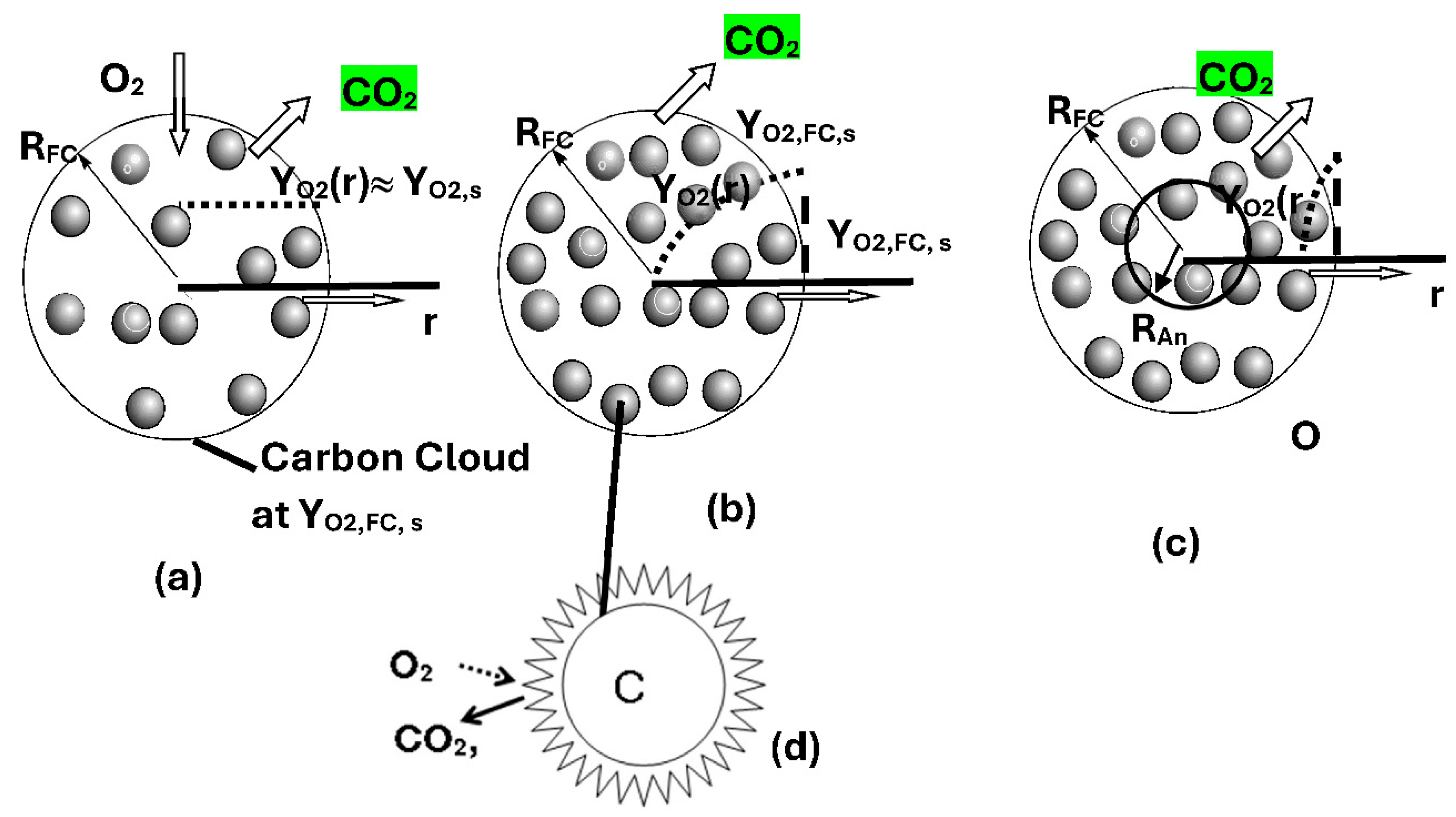

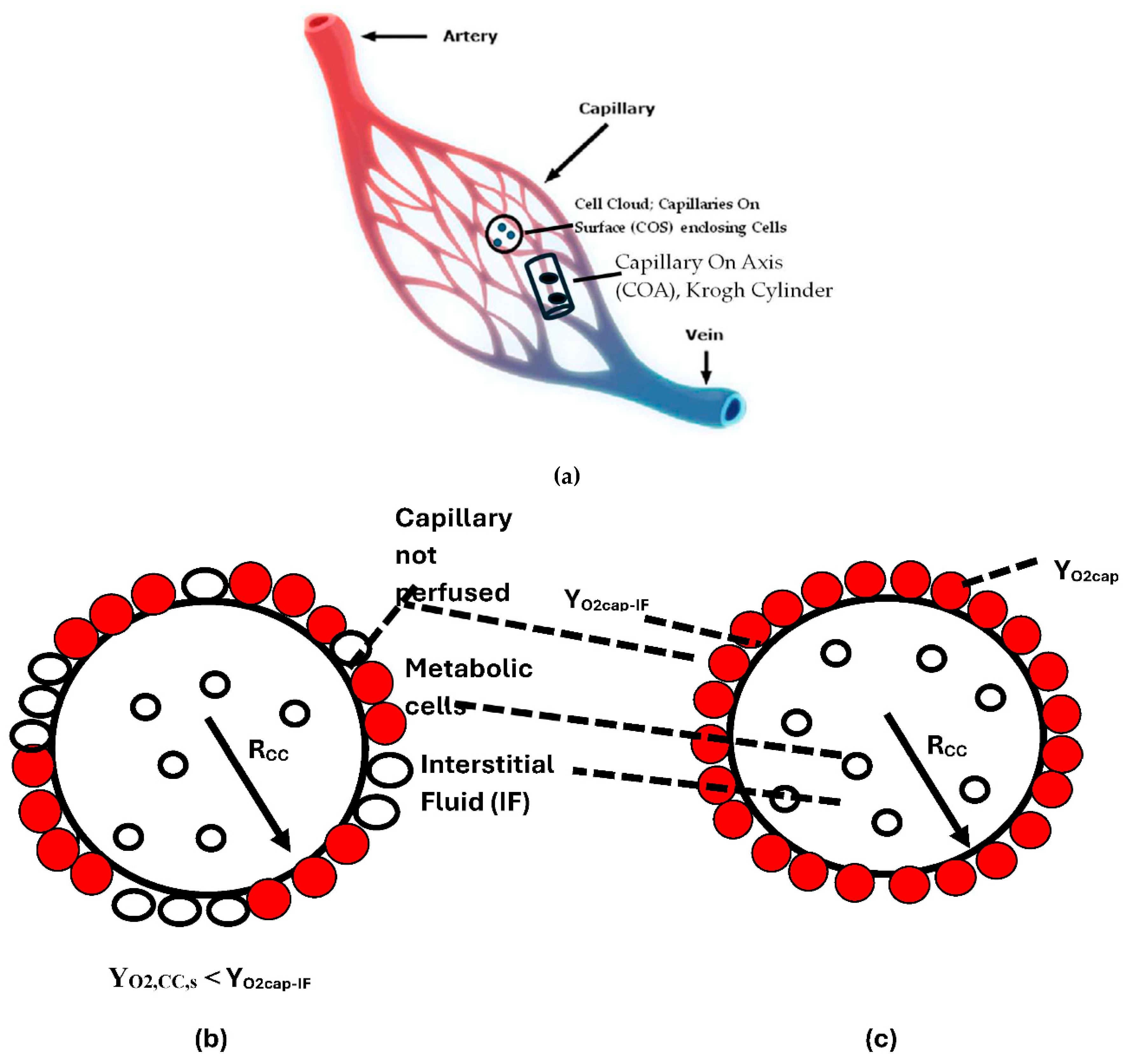

2.1. ODM Hypothesis

2.2. Methodology

- i)

- Metabolic Rate of single cell located at r in CC {Figure 3}

- ii)

- Oxygen Profiles within CC

- iii)

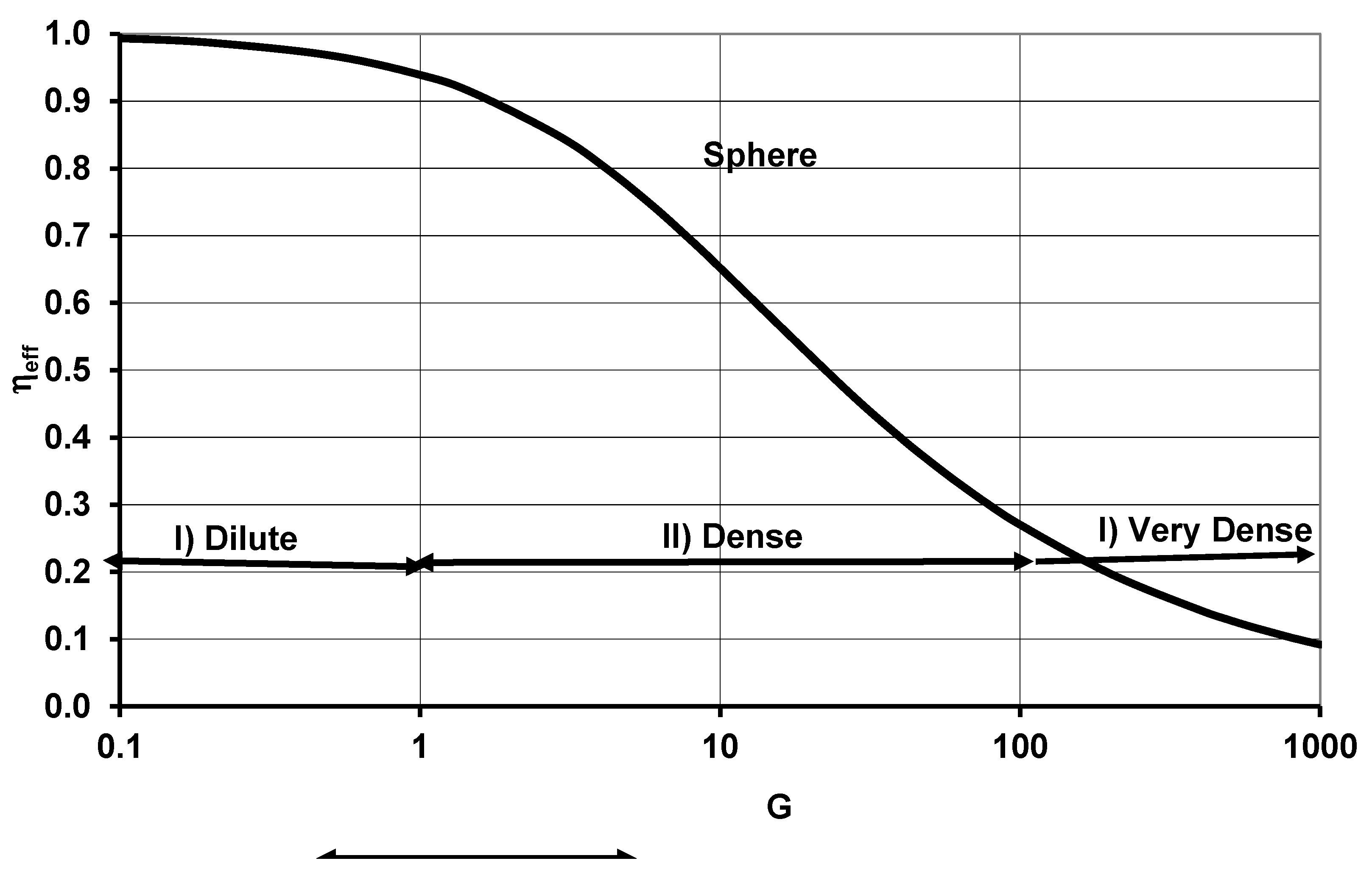

- Effectiveness Factor of Spherical CC and Specific Organ Metabolic Rate {SOrMRk}

- iv)

- Metabolic Rate of Vital Organs {}: Using Equation 17 for the vital organs, the metabolic rates of vital organs of any BS:

- v)

- Metabolic Rate of Remaining Mass (RM) of Tissues {} for any BS

- vi)

- Whole Body Metabolic Rate () under Rest

- vii)

- Metabolic Rate of RM {} and Whole Body Metabolic Rate {} under Exercise

- viii)

- Upper Metabolic Rate (UPR,) and Maximum Metabolic Rate (MMR,) of Whole Body

2.3. Estimation of OD Number (GOD,k) and Effectiveness Factor (ηeff,k) of Organ k any BS

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Whole Body Metabolic Rate using EAR for All Organs and the Effect of Elia’s Constant for on Whole-Body Allometry

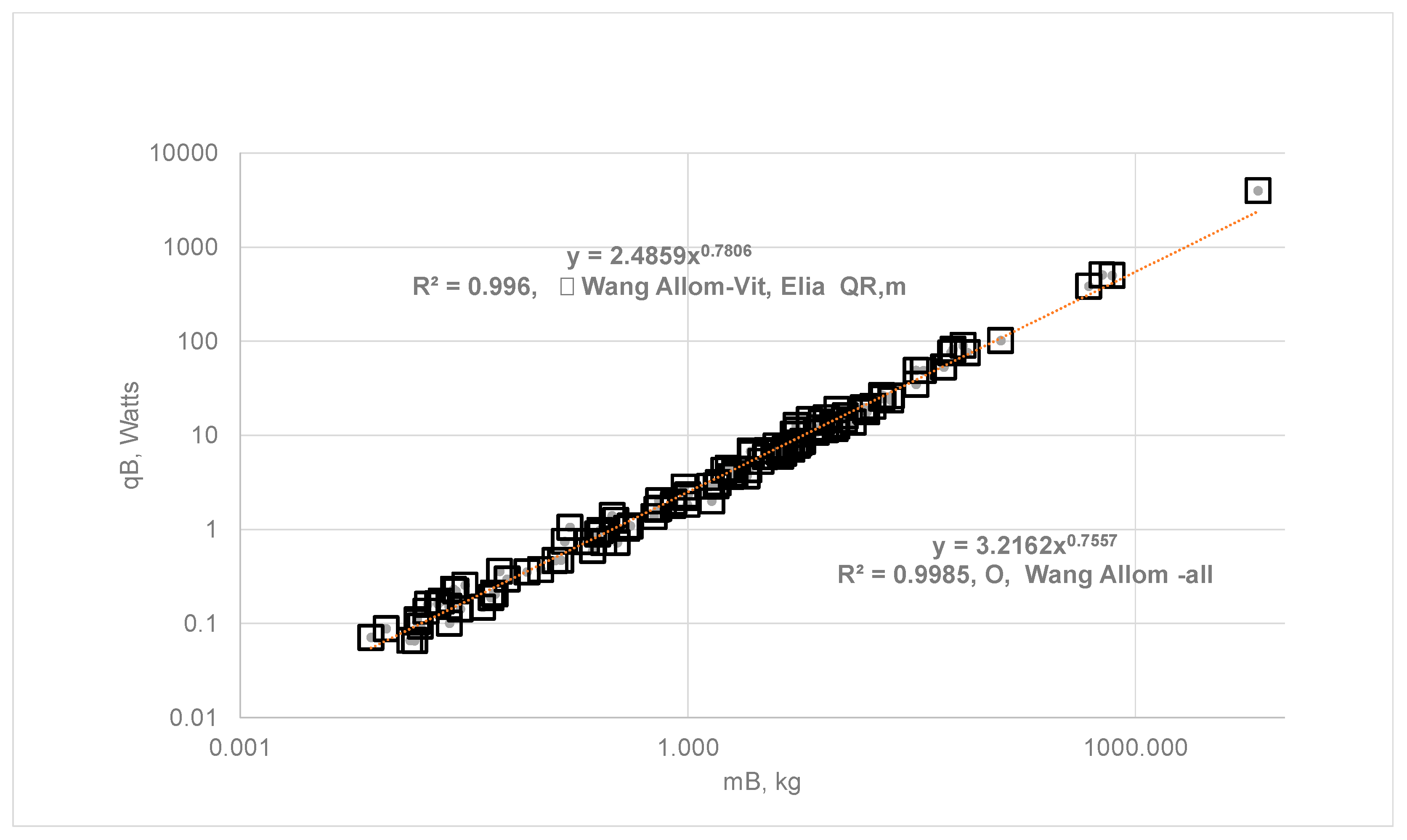

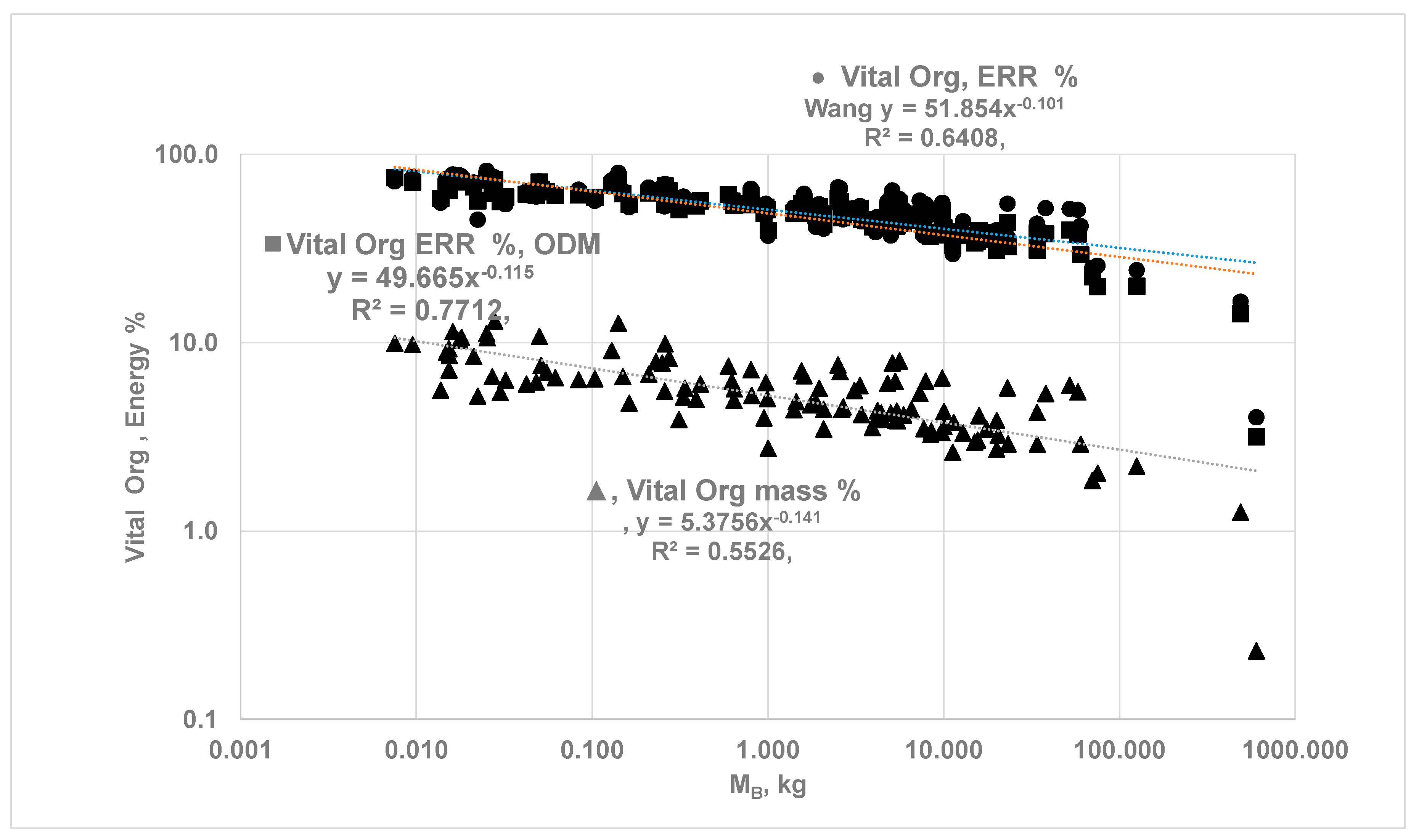

- Empirical Allometric Relations (EAR) for all Organs: Hereafter, Wang’s allometric relations will be referred to as EAR (Equation 4) or, , which are obtained with data on SOrMRk ( , W/kg of k, k=Kids, H, Br, L and RM) vers us the body mass for six species. The same allometric constants were then extended to estimate SOrMRk of 116 species, summing up OrMRk to obtain the whole-body metabolic rate and validating Wang’s approach by demonstrating Kleiber’s law with a = 3.22 and b = 0.76. Note that EAR is used only for and is estimated using organ masses listed in Table 3 {Appendix A} which tabulates the BS, body mass, organ masses for 116 species, and using EAR.

- EAR for Vital Organs and Elia Constant for RM: The author used the same allometric constants for vital organs but assumed Elia’s constant qRM of 0.581 W/kg and computed the whole-body metabolic rate. With Elia’s constant, , the Kleiber’s law exponents become a = 2.49, and b = 0.78. It is seen from Figure 4 that the slope b increased from 0.76 to 0.78, representing a 3.3 % increase in the exponent b when Elis’s constant is used for RM.

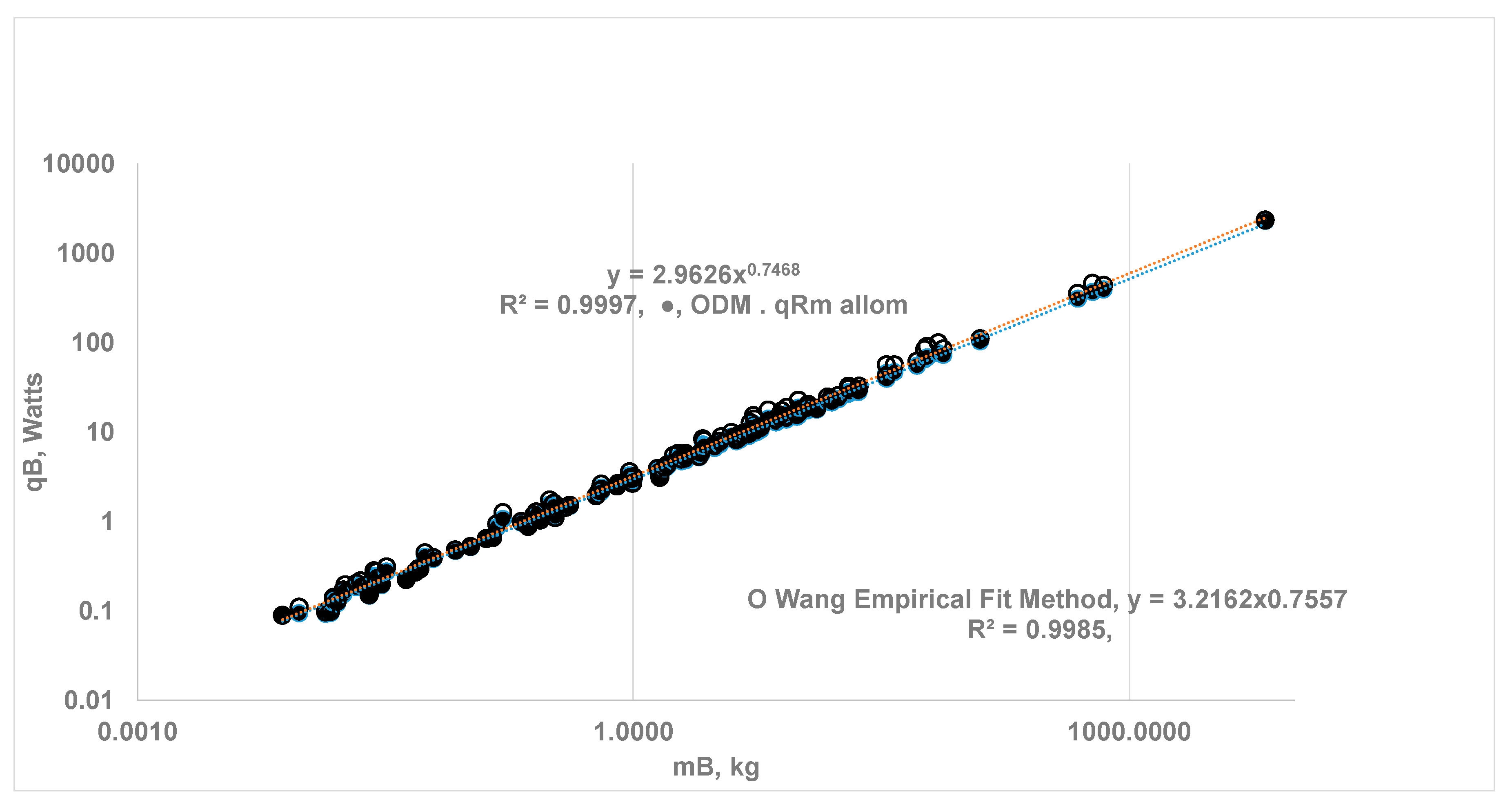

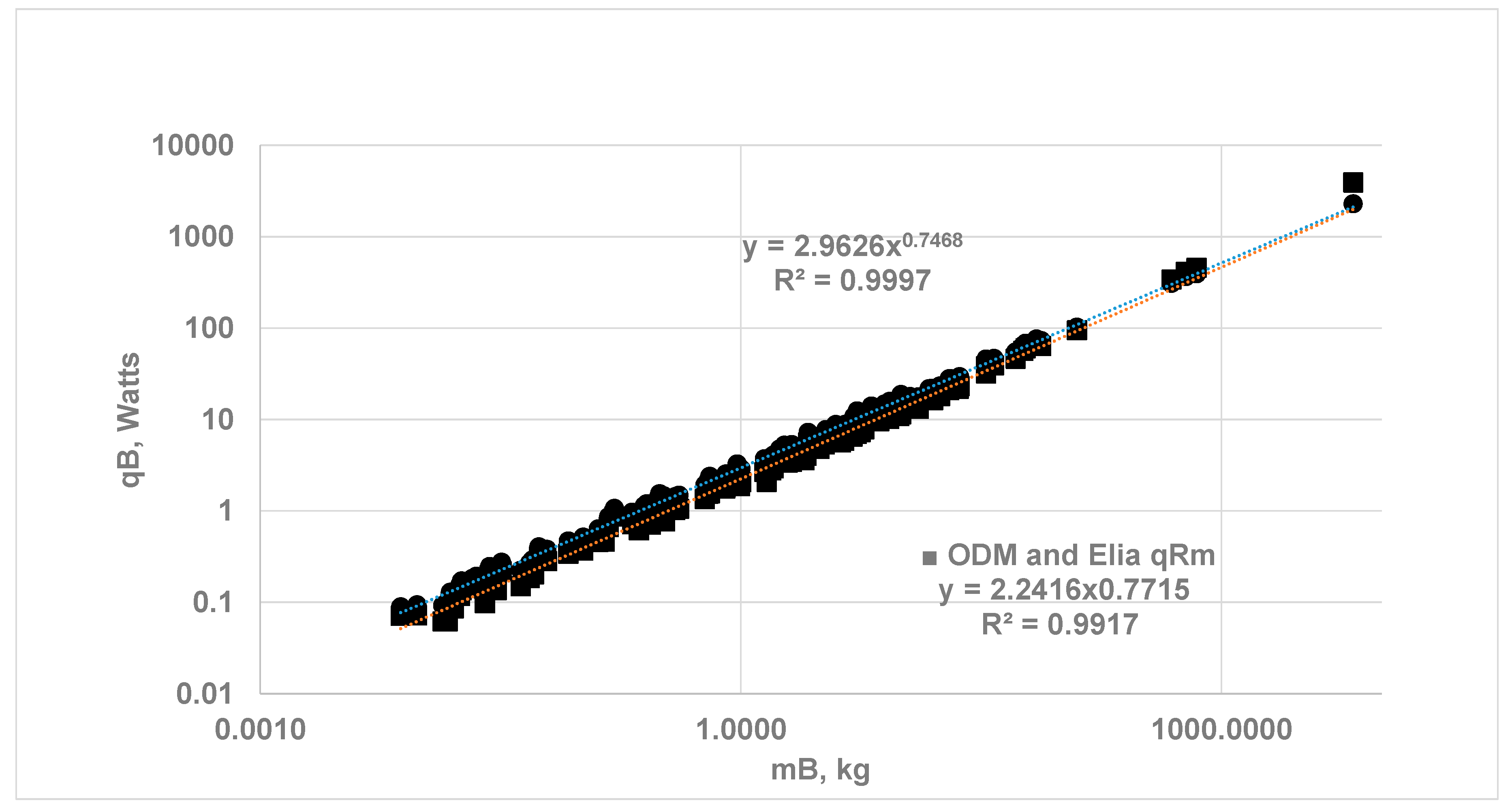

3.2. Whole Body Metabolic Rate Using ODM Hypothesis and Comparison with Results from EAR Method

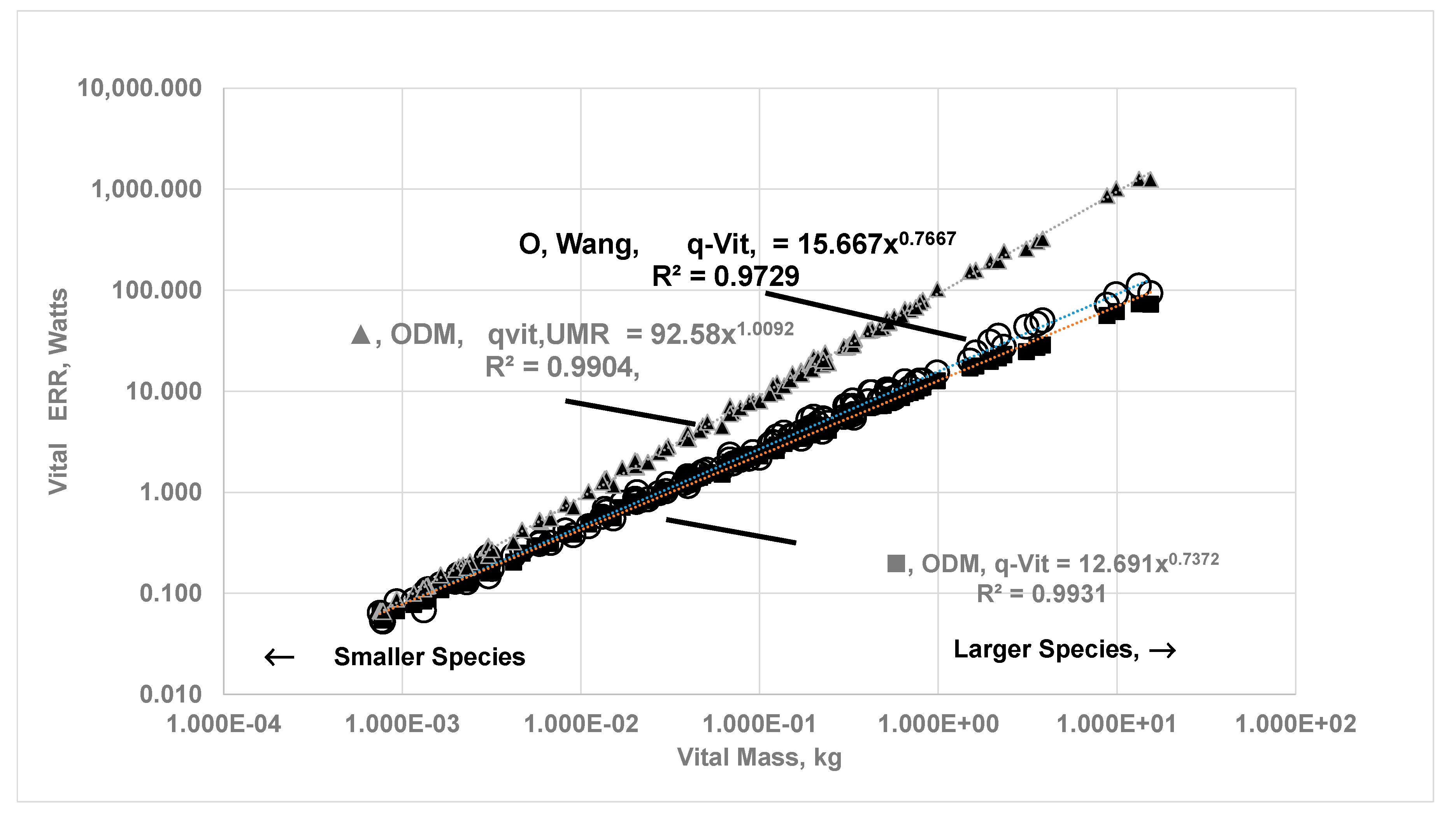

3.3. Vital Organ Contribution Percentage via ODM and Comparison of results with Empirical Allometric Laws

3.4. The Upper Metabolic Rate of Organ {UMRB }, Maximum Metabolic Rate of Organ (MMRk) and MMRB of Whole-Body

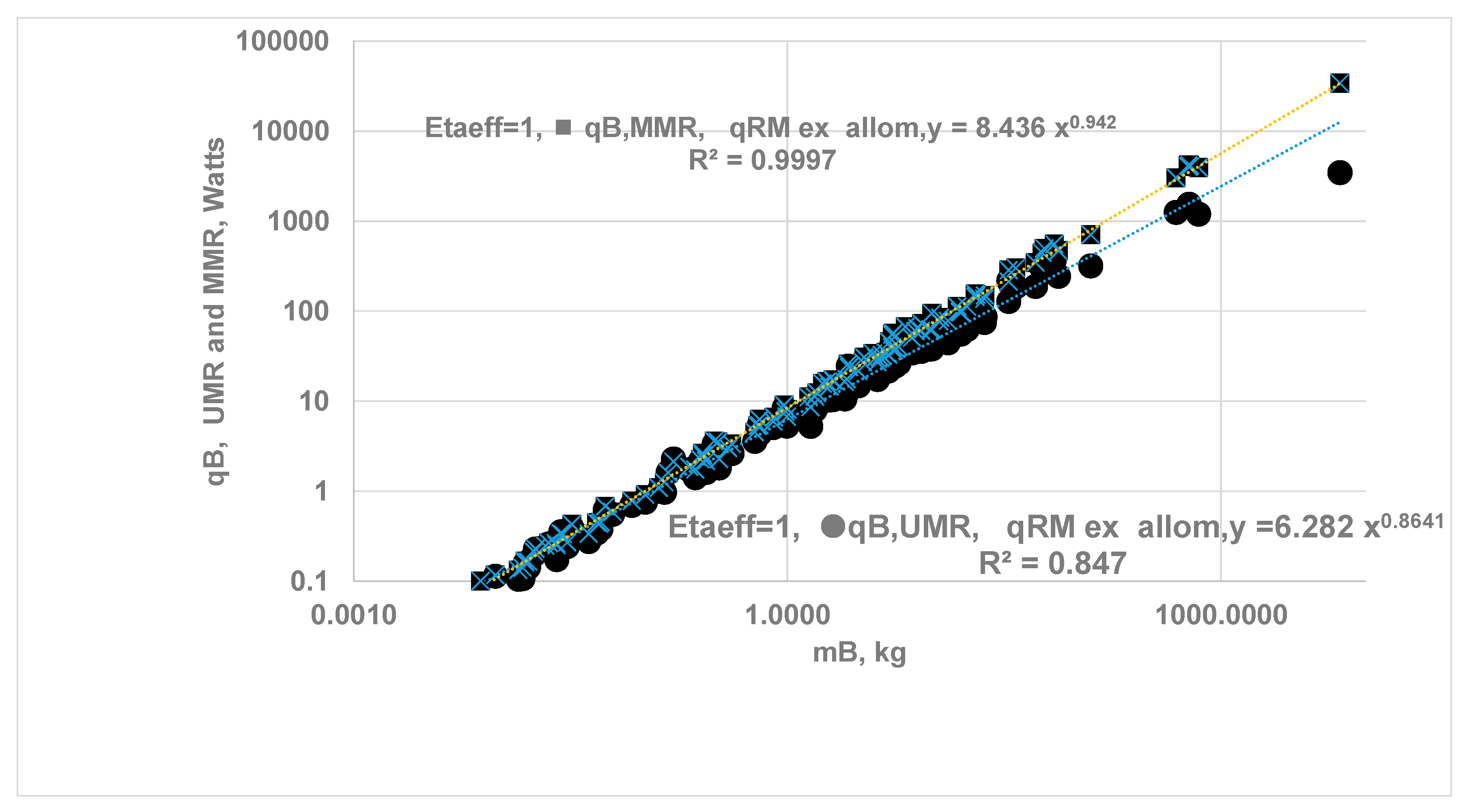

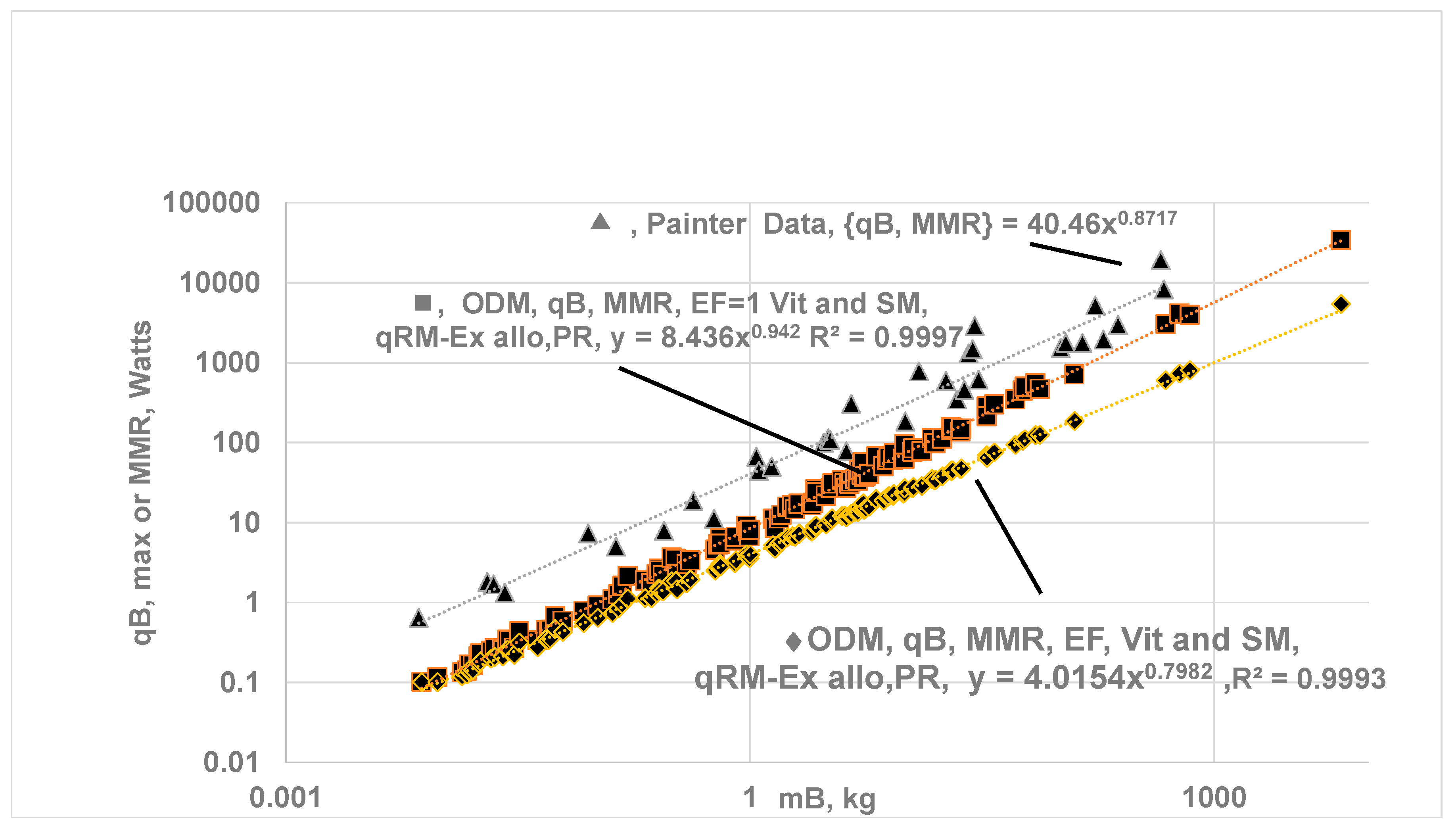

- a)

- The {ηeff,CC}k is finite for vital organs but isolated metabolic rate is altered due to change in capillary perfusion ratio (Equation 2420, Table 2 }: reduced for kidneys (0.55) and liver (0.67) but increased for H (3) , SM (10.4) and RM-ex (1.16). For SM and RM-ex, the SOrMRk are given by the product of allometric laws of RM as at rest and perfusion ratio. Figure 9 compares the results for under ODM with the literature data for . If , a MMR= 4.015 and bMMR = 0.798. The slope under exercise is steeper than the slope under rest.

- b)

- The ηeff,CC is set to 1 for all vital organs and SM {i.e no O2 gradient during exercise} but RM-ex given by allometric law with correction for perfusion ratio of 1.16. Even if O2 gradients are present for organs other than H and SM, results may not change since metabolic rate from SM dominates. a MMR= 8.436 and bMMR = 0.942, ηeff,k=1.

- i)

- The predicted values for bMMR range from 0.798 to 0.942 with an average of 0.87. The upper value of bMMR indicates almost isometric law. It is believed that MMR must follow an isometric law since the “cost” of transportation (e.g., tread mill, jogging) must be proportional to body mass, meaning SMMR {specific maximum metabolic rate, W/kg} must not differ between smaller and larger species during exercise. Ref. [8] states that when a 20 g mouse and 500 kg racehorse run at their maximum capacity, their specific maximal metabolic rate (W/g) is nearly the same. This finding agrees with the ODM model, indicating all cells within an organ are subjected to oxygen concentrations close to their highest possible values.

- ii)

- The literature data mostly reports {mL of O2 per min} vs MB under exercise. It is converted into watts using HHVO2 of 20.5 J/mL of O2. where in Watts and in mL/min . Painter collected data on MMR for 32 mammalian BS ranging from 0.007 kg (pygmy mice) to 575 kg (cattle), found that bMMR = 0.872 (95% CI : bMMR = 0.812-0.931) found and attributes the increase from 0.75 at rest to 0.872 under exercise to the increased O2 transport to cells with the heart as the limiting step [15]. Based on VO2max [67] in mL/min, aMMR = 40.46 bMMR = 0.872 .Weibel et al. [16] conducted treadmill experiments in animals to measure VO2 max (highest rate for 5 min) and reported aMMR = 118 mL/min or 40.4 W, with bMMR = 0.872 for 34 mammalian species, including both athletic and non-athletic groups (0.007 to 500 kg). They further reported bMMR =0.942 for the athletic group {predicted upper value for bMMR when ηeff=1 for vital organs and SM} and 0.849 for non-athletic group [16]. Data from Talyor et al. [67] and Ref. [8] report bmMR = 0.87 - 0.88 for homeotherm.

- iii)

- Ref. [6], bMMR = 0.872 or 7/8 (see Fig. 6 in Ref. [6]), [15] ; Agutter bMMR = 0.86 [72]. Ref [68]: bMMR = 0. for MB =0.3 to 300 kg, but increases to 0.86 for MB = 0.3 to 500 kg. Single Flow Network model bMMR = 6/7 [58] . However the predicted aMMR is low compared to literature data. MMR is largely driven by the high MR of SM, and the predicted low values of aMMR orignate from the allometric relation of SM and body mass used in the current ODM model. This model assumes a similar SM mass percentage relative to body mass across species, yielding low SM values for humans. According to Weibel and Hoppeler [16], SM is about 42% of body mass in the athletic wood mouse (small animal), 45% in the pronghorn and 25% in the goat, with an average of 36% of body mass. Further, skeleton mass varies significantly, with the shrew at 5% and the elephant at 25% [71]. These findings indicate a wide variation in SM mass across body sizes.

- iv)

- The current results for MMR are validated further with the data reported by Midorikawa et al [65]. The VO2max (during maximal exercise) of sumo wrestlers is about 30 mL/min/kg or 10.25 W/kg, attributed to SM, liver and kidneys [65]. For a 58 kg individual, reported data show =1320 W, while the predicted value is 446 W . Why do measured values exceed predictions from the ODM model ? The allometry for SM predicts a mass of 5.1 kg for 58 kg human, whereas the measured value is 24 kg for a 58 kg person! When the author used the actual SM mass of 24 kg (without using allometric SM mass) and mRM-EX = MB - mSM - mvit = 58 - 24 - 5.4 = 28.6 kg, the predicted increased to 1045 W ( =296 W, EAR) with reported data at =1320 W.

3.4. A Method of Tracking GODk Number for Organs During Growth of Humans or any other BS by Medical Personnel

- I)

- Direct Method: Measure Organ Masses and known SOrMRk of RS-1: Measure blood flow rate and the change in O2 concentration between the arterial and venous ends of the organ to estimate OrMRk. Directly measure organ masses using CT scan or MRI, then estimate SOrMRk (=OrMRk / mk) and compare with SOrMRk of the shrew (i.e., isolated). Estimate ηeff,k and determine GOD, k of organ k using Equation 1613.

- II)

- Ratio method for Same BS: Assume that (GOD k at any age / GOD k at birth) = ( mk / mk,birth)lk if GOD,k at birth and mk,birth are known.Typically lk =2/3.

- III)

- GOD,k for normal growth in terms of Body Mass data MB(t): The ODM method presents SOrMRk in terms of a powerful dimensionless parameter GOD k, which is proportional to mkl. Using the allometric law for organ masses (Equation 5) , where lk =2/3 and dk values are tabulated in Table 1.

- IV)

- Ratio Method, GOD,k in terms of measured Organ Masses and Reference Species RS-2: Assuming Rat Wistar as RS-2 and knowing GOD ,k of RS-2, one can determine GOD ,k if organ mass data is available.

4. Summary and Conclusions

5. Future Work

- Whether the secrets of Kleiber’s law and maximal metabolic rate allometries in biology can be revealed from oxygen-deficient combustion engineering remains an open question. Additional supporting data are needed either to confirm or question the ODM hypothesis.

- While the present study focuses on interspecific relations across 116 species, the approach may also apply to intraspecific relations, such as human growth from 2 kg to 70 kg. As organs grow, GOD, k can be monitored throughout the development process. Notably, human brain growth appears to deviate from the allometric laws for organ masses based on Wang’s six-species data.

- Collect statistical data to determine whether cancer development correlates with abnormal increases in GOD,k and assess its relationship with cancer occurrence.

- Conduct future studies on the impact of RS-2 selection on Kleiber’s law.

- A more precise allometric relationship is needed for SM mass relative to body mass MB since it directly affects the predicted MMR in the ODM model.

- Develop a Krogh-type COA model incorporating the ODM method, define GOD,k for COA and evaluate whether Kleiber’s law holds.

- Gather data on cell reactivity, cell size, cell density and organ mass to estimate GOD,k using fundamental biological parameters.

- While the current work follows a “downstream” hypothesis based on cell kinetics, the WBE employs an “upstream” flow network (or supply-side) hypothesis and optimization. Future work should aim to integrate these two hypotheses to understand their combined effects on mass fraction of O2 at the cell cloud surface {YO2,cc,s }.

Funding

Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest and other Ethics Statements

Abbreviations

| a | Normalization Constant in Kleiber’s law |

| b | allometric scaling exponent in Kleiber’s law |

| BMA | Body mass based Allometry |

| BMR | Basal Metabolic Rate |

| CC | Cell Cloud |

| CCh,p | Characteristic O2 consumption rate by particle in fuel cloud [3] |

| Cch, cell | Characteristic O2 consumption rate by a cell in cell cloud [3] |

| Cap | Capillary |

| Cap-IF | Interface between capillary and Interstitial Fluid (IF) |

| COA | Capillary on Axis |

| COS | Capillary On Surface |

| EAR | Empirical Allometric Relation |

| EQ | Encephalization Quotient |

| ERR | Energy release rate, W |

| FC | Fuel (particle) Cloud |

| IF | Interstitial Fluid (IF) |

| MB | Body mass |

| MR | Metabolic Rate |

| MMR | Maximal Metabolic Rate |

| m | mass |

| nCC | number density of cells, cells/m3 |

| nFC | number density of fuel particle, particles/m3 |

| OD | Oxygen deficient/deficiency |

| ODC | Oxygen-Deficient Metabolism |

| ODM | Oxygen-Deficient Metabolism |

| OEF | Oxygen Extraction Fraction |

| OEM | Oxygen extraction Fraction |

| OMA | Organ Mass Based Allometry |

| OrMk | Organ metabolic rate of organ k, = SOrMk x mk , W |

| qk,m | Metabolic rate of organ k per unit mass of organ, (W/kg of organ k) |

| qM | Metabolic rate of whole body per unit mass of body, (W/kg of body) |

| RM | Remaining Mass , MB- mvitt |

| RM,Ex | Remaining Mass during exercise , MB- mvitt-mSM |

| SATP | Standard Atm Temperature and Pressure, T = 25 C, P = 101 kPa |

| SBMR | Specific Basal Metabolic Rate (W/kg of body) |

| SERR | Specific Energy release rate (W/kg of cloud) |

| SM | Skeletal Muscle |

| SOrMRk | Specific organ metabolic rate, |

| UMR | Upper Metabolic rate when O2 gradient is zero |

| WBE | West, Brown and Enquist |

| Vit | vital organs |

| YO2 | Oxygen mass fraction g of O2 per g of mixture |

| YO2,CC,s | Oxygen mass fraction at surface of cell cloud |

| YO2,FC,s | Oxygen mass fraction at surface of fuel cloud |

Appendix A

| Species | MB,kg | W/kg | W/kg | W/kg | W/kg | W/kg | 100xmkidskg | 100xmH, kg | 100xmBr , kg | 100xmL kg | 100xmvit kg | Vit ERR % ODM | Vit ERR % EAR, | ODM W | EAR, W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shrew/Sorex araneus | 0.00755 | 50.2 | 76.8 | 43.3 | 122.5 | 3.3 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.015 | 0.038 | 0.68 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| 2 | Crocidura russula | 0.00953 | 49.2 | 74.7 | 41.9 | 115.1 | 3.2 | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.055 | 0.86 | 75.7 | 75.7 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| 3 | Lasiurus borealis | 0.01377 | 47.7 | 71.5 | 39.8 | 104.3 | 3.0 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.035 | 1.3 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| 4 | Lasionycteris noctivagans | 0.01478 | 47.5 | 70.9 | 39.4 | 102.3 | 2.9 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.033 | 1.4 | 53.2 | 53.2 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| 5 | Mus musculus | 0.01539 | 47.3 | 70.6 | 39.2 | 101.2 | 2.9 | 0.028 | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.068 | 1.4 | 77.1 | 77.1 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| 6 | Myodes glareolus | 0.01536 | 47.3 | 70.6 | 39.2 | 101.3 | 2.9 | 0.024 | 0.01 | 0.035 | 0.067 | 1.4 | 74.1 | 74.1 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| 7 | Microtus agrestis | 0.01531 | 47.3 | 70.6 | 39.2 | 101.4 | 2.9 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.039 | 0.063 | 1.4 | 69.8 | 69.8 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| 8 | Neomys fodiens | 0.01616 | 47.1 | 70.2 | 38.9 | 99.9 | 2.9 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.025 | 0.055 | 1.5 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| 9 | Blarina brevicauda | 0.01764 | 46.8 | 69.5 | 38.4 | 97.6 | 2.8 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.032 | 0.093 | 1.6 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| 10 | Apodemus sylvaticus | 0.01807 | 46.7 | 69.3 | 38.3 | 97.0 | 2.8 | 0.026 | 0.014 | 0.057 | 0.11 | 1.6 | 78.1 | 78.1 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| 11 | Microtus | 0.02119 | 46.1 | 68.0 | 37.4 | 92.9 | 2.8 | 0.036 | 0.015 | 0.058 | 0.11 | 1.9 | 77.3 | 77.3 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| 12 | Peromyscus leucopus | 0.02239 | 45.9 | 67.5 | 37.1 | 91.6 | 2.7 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.074 | 0.12 | 2 | 76.4 | 76.4 | 0.19 | 0.22 |

| 13 | Apodemus flavicollis | 0.02513 | 45.4 | 66.6 | 36.5 | 88.8 | 2.7 | 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.061 | 0.1 | 2.3 | 70.9 | 70.9 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| 14 | Nyctalus noctula | 0.02532 | 45.4 | 66.6 | 36.5 | 88.6 | 2.7 | 0.013 | 0.037 | 0.032 | 0.05 | 2.4 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| 15 | Microtus arvalis | 0.02703 | 45.1 | 66.0 | 36.1 | 87.1 | 2.6 | 0.055 | 0.019 | 0.039 | 0.19 | 2.4 | 81.7 | 81.7 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| 16 | Mouse | 0.02797 | 45.0 | 65.8 | 36.0 | 86.3 | 2.6 | 0.051 | 0.016 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 2.5 | 80.4 | 80.4 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| 17 | Gerbillus perpallidus | 0.02998 | 44.8 | 65.2 | 35.6 | 84.7 | 2.6 | 0.027 | 0.013 | 0.058 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 65.1 | 65.1 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| 18 | Mustela nivalis | 0.03219 | 44.5 | 64.7 | 35.3 | 83.1 | 2.6 | 0.043 | 0.036 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 2.8 | 75.5 | 75.5 | 0.27 | 0.31 |

| 19 | Acomys minous | 0.0423 | 43.5 | 62.6 | 33.9 | 77.2 | 2.5 | 0.032 | 0.018 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 4 | 57.2 | 57.2 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| 20 | Jaculus jaculus | 0.04804 | 43.0 | 61.7 | 33.3 | 74.6 | 2.4 | 0.029 | 0.045 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 4.5 | 54.3 | 54.3 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| 21 | Rhabdomys pumilio | 0.05002 | 42.9 | 61.4 | 33.1 | 73.8 | 2.4 | 0.041 | 0.021 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 4.7 | 63.6 | 63.6 | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| 22 | Talpa europaea | 0.05117 | 42.8 | 61.2 | 33.0 | 73.4 | 2.4 | 0.036 | 0.031 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 4.8 | 59.6 | 59.6 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| 23 | Glaucomys volans | 0.05495 | 42.5 | 60.7 | 32.7 | 72.0 | 2.4 | 0.059 | 0.056 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 4.9 | 72.1 | 72.1 | 0.40 | 0.45 |

| 24 | Arvicola terrestris | 0.06168 | 42.1 | 59.9 | 32.1 | 69.8 | 2.3 | 0.07 | 0.028 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 5.7 | 69.9 | 69.9 | 0.38 | 0.39 |

| 25 | Glis glis | 0.08386 | 41.1 | 57.8 | 30.8 | 64.3 | 2.2 | 0.068 | 0.048 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 7.8 | 64.3 | 64.3 | 0.47 | 0.48 |

| 26 | Tamias striatus | 0.10377 | 40.4 | 56.3 | 29.8 | 60.7 | 2.1 | 0.081 | 0.066 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 9.7 | 59.9 | 59.9 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| 27 | Octodon degus | 0.12921 | 39.6 | 54.9 | 28.9 | 57.3 | 2.0 | 0.11 | 0.041 | 0.19 | 0.48 | 12.1 | 64.9 | 64.9 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| 28 | Tupaia glis | 0.14107 | 39.3 | 54.3 | 28.6 | 55.9 | 2.0 | 0.11 | 0.117 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 13.2 | 56.7 | 56.7 | 0.65 | 0.66 |

| 29 | Rat | 0.1496 | 39.1 | 54.0 | 28.3 | 55.1 | 2.0 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.92 | 13.6 | 72.9 | 72.9 | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| 30 | Cebuella Cebuella | 0.16266 | 38.9 | 53.4 | 28.0 | 53.8 | 2.0 | 0.19 | 0.086 | 0.44 | 1.35 | 14.2 | 79.9 | 79.9 | 1.06 | 1.25 |

| 31 | Rattus norvegicus | 0.20987 | 38.1 | 51.8 | 27.0 | 50.3 | 1.9 | 0.15 | 0.087 | 0.23 | 0.92 | 19.6 | 64.2 | 64.2 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| 32 | Cheirogaleus medius | 0.23103 | 37.8 | 51.3 | 26.6 | 49.0 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.093 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 22 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| 33 | Rat | 0.25004 | 37.5 | 50.8 | 26.3 | 48.0 | 1.8 | 0.21 | 0.094 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 23.3 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 1.13 | 1.18 |

| 34 | Mustela erminea | 0.2585 | 37.4 | 50.6 | 26.2 | 47.6 | 1.8 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 1 | 23.8 | 62.8 | 62.8 | 1.19 | 1.27 |

| 35 | Helogale parvula | 0.2603 | 37.4 | 50.5 | 26.2 | 47.5 | 1.8 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.52 | 1.11 | 24 | 67.0 | 67.0 | 1.20 | 1.27 |

| 36 | Sciurus vulgaris | 0.2742 | 37.2 | 50.2 | 26.0 | 46.8 | 1.8 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 25.9 | 52.9 | 52.9 | 1.02 | 1.04 |

| 37 | Callithrix jacchus | 0.3118 | 36.8 | 49.5 | 25.5 | 45.2 | 1.8 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.73 | 1.78 | 28.1 | 69.6 | 69.6 | 1.55 | 1.73 |

| 38 | Saguinus fuscicollis | 0.3304 | 36.6 | 49.1 | 25.3 | 44.5 | 1.7 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.78 | 1.44 | 30.3 | 61.2 | 61.2 | 1.47 | 1.60 |

| 39 | Rat | 0.3372 | 36.6 | 49.0 | 25.2 | 44.3 | 1.7 | 0.23 | 0.1 | 0.19 | 0.8 | 32.4 | 51.9 | 51.9 | 1.14 | 1.10 |

| 40 | Rat (Wistar) | 0.3901 | 36.1 | 48.2 | 24.7 | 42.6 | 1.7 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 1.43 | 37 | 59.7 | 59.7 | 1.43 | 1.44 |

| 41 | Sciurus niger | 0.4127 | 36.0 | 47.9 | 24.5 | 42.0 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 1.07 | 38.9 | 56.0 | 56.0 | 1.48 | 1.51 |

| 42 | Sciurus carolinensis | 0.5959 | 34.9 | 45.8 | 23.3 | 38.0 | 1.6 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.75 | 1.64 | 56.6 | 52.8 | 52.8 | 1.92 | 1.93 |

| 43 | Saguinus oedipus | 0.6237 | 34.8 | 45.6 | 23.1 | 37.6 | 1.6 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 1 | 2.09 | 58.6 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 2.12 | 2.21 |

| 44 | Mustela putorius | 0.64 | 34.7 | 45.4 | 23.0 | 37.3 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.48 | 1.04 | 2.88 | 59.2 | 61.3 | 61.3 | 2.39 | 2.60 |

| 45 | Leontopithecus chrysomelas | 0.642 | 34.7 | 45.4 | 23.0 | 37.3 | 1.6 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 1.32 | 1.89 | 60.2 | 57.1 | 57.1 | 2.15 | 2.26 |

| 46 | Guinea pig | 0.7996 | 34.0 | 44.3 | 22.3 | 35.2 | 1.5 | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 2.7 | 76 | 57.6 | 57.6 | 2.46 | 2.49 |

| 47 | Potorous tridactylu | 0.8091 | 34.0 | 44.2 | 22.3 | 35.0 | 1.5 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 1.14 | 2.37 | 76.3 | 56.7 | 56.7 | 2.55 | 2.65 |

| 48 | Erinaceus europaeus | 0.9493 | 33.6 | 43.4 | 21.8 | 33.6 | 1.5 | 0.89 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 4.96 | 88.1 | 65.7 | 65.7 | 3.27 | 3.59 |

| 49 | Sylvilagus floridanus | 0.972 | 33.5 | 43.3 | 21.7 | 33.4 | 1.5 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 3.2 | 92.1 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 2.91 | 3.00 |

| 50 | Ondatra zibethicus | 0.9915 | 33.4 | 43.2 | 21.6 | 33.2 | 1.5 | 0.58 | 0.3 | 0.47 | 2.6 | 95.2 | 50.6 | 50.6 | 2.70 | 2.67 |

| 51 | Saimiri boliviensis | 1.0026 | 33.4 | 43.1 | 21.6 | 33.1 | 1.5 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 2.9 | 1.94 | 94.1 | 54.7 | 54.7 | 2.87 | 3.14 |

| 52 | Martes foina | 1.406 | 32.5 | 41.4 | 20.6 | 30.2 | 1.4 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 1.9 | 3.49 | 133.5 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 3.72 | 3.92 |

| 53 | Mephitis mephitis | 1.4488 | 32.4 | 41.3 | 20.5 | 30.0 | 1.4 | 0.66 | 0.6 | 0.98 | 1.74 | 140.9 | 37.0 | 37.0 | 3.17 | 3.11 |

| 54 | Trichosurus vulpecula | 1.5504 | 32.2 | 40.9 | 20.3 | 29.4 | 1.3 | 1.35 | 0.9 | 1.27 | 3.32 | 148.2 | 52.1 | 52.1 | 3.91 | 4.04 |

| 55 | Martes martes | 1.603 | 32.1 | 40.8 | 20.2 | 29.2 | 1.3 | 0.88 | 1.08 | 2.05 | 3.79 | 152.5 | 48.6 | 48.6 | 4.08 | 4.29 |

| 56 | Cebus apella | 1.7499 | 31.9 | 40.4 | 20.0 | 28.5 | 1.3 | 1.04 | 1.34 | 5.08 | 4.93 | 162.6 | 56.7 | 56.7 | 4.75 | 5.44 |

| 57 | Eulemur macaco macaco | 1.8753 | 31.7 | 40.0 | 19.8 | 28.0 | 1.3 | 1.42 | 0.91 | 2.42 | 7.78 | 175 | 61.8 | 61.8 | 5.22 | 5.76 |

| 58 | Chrotagale owstoni | 1.9598 | 31.6 | 39.8 | 19.6 | 27.7 | 1.3 | 1.28 | 1.16 | 2.33 | 4.41 | 186.8 | 50.1 | 50.1 | 4.72 | 4.97 |

| 59 | Vulpes corsac | 2.0752 | 31.4 | 39.6 | 19.5 | 27.2 | 1.3 | 0.88 | 2.17 | 3.41 | 3.56 | 197.5 | 41.2 | 41.2 | 4.82 | 5.31 |

| 60 | Lemur catta | 2.0746 | 31.4 | 39.6 | 19.5 | 27.2 | 1.3 | 1.12 | 1.17 | 2.28 | 7.29 | 195.6 | 54.4 | 54.4 | 5.33 | 5.76 |

| 61 | Eulemur fulvus fulvus | 2.5002 | 31.0 | 38.7 | 19.0 | 25.9 | 1.2 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 2.25 | 4.34 | 241.3 | 40.3 | 40.3 | 5.21 | 5.31 |

| 62 | Felis silvestris | 2.573 | 30.9 | 38.6 | 18.9 | 25.7 | 1.2 | 1.54 | 1.03 | 3.81 | 5.02 | 245.9 | 49.9 | 49.9 | 5.62 | 5.93 |

| 63 | Didelphis virginiana | 2.6336 | 30.8 | 38.5 | 18.8 | 25.6 | 1.2 | 2.29 | 1.21 | 0.83 | 15.73 | 243.3 | 66.9 | 66.9 | 7.24 | 8.35 |

| 64 | Aonyx cinerea | 2.675 | 30.8 | 38.4 | 18.8 | 25.4 | 1.2 | 3.06 | 1.51 | 3.59 | 10.64 | 248.7 | 66.1 | 66.1 | 6.97 | 7.97 |

| 65 | Leopardus geoffroyi | 3.1002 | 30.4 | 37.7 | 18.4 | 24.5 | 1.2 | 3.07 | 1.6 | 3.21 | 5.84 | 296.3 | 54.6 | 54.6 | 6.61 | 7.12 |

| 66 | Lepus europaeus | 3.3386 | 30.2 | 37.4 | 18.2 | 24.0 | 1.2 | 1.85 | 2.89 | 1.48 | 9.04 | 318.6 | 45.2 | 45.2 | 7.26 | 7.86 |

| 67 | Dasyprocta punctata | 3.4002 | 30.2 | 37.3 | 18.2 | 23.9 | 1.2 | 2.13 | 3.63 | 2.28 | 10.88 | 321.1 | 48.8 | 48.8 | 7.81 | 8.81 |

| 68 | Potos flavus | 3.9203 | 29.8 | 36.7 | 17.8 | 23.0 | 1.2 | 1.44 | 2.11 | 3.11 | 16.57 | 368.8 | 53.1 | 53.1 | 8.84 | 9.82 |

| 69 | Dasyprocta azarae | 4.1004 | 29.7 | 36.5 | 17.7 | 22.7 | 1.1 | 2.27 | 3.04 | 2.38 | 9.35 | 393 | 44.1 | 44.1 | 8.22 | 8.83 |

| 70 | Varecia rubra | 4.2004 | 29.6 | 36.4 | 17.6 | 22.5 | 1.1 | 2.24 | 1.81 | 3.57 | 7.22 | 405.2 | 43.7 | 43.7 | 7.87 | 8.21 |

| 71 | Alouatta sara | 4.3996 | 29.5 | 36.2 | 17.5 | 22.3 | 1.1 | 0.99 | 2.4 | 5.65 | 8.12 | 422.8 | 38.7 | 38.7 | 8.20 | 8.75 |

| 72 | Monkey | 4.5 | 29.5 | 36.1 | 17.5 | 22.1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 11 | 430.4 | 46.5 | 46.5 | 8.85 | 9.48 |

| 73 | Martes pennanti | 4.7907 | 29.3 | 35.8 | 17.3 | 21.8 | 1.1 | 2.11 | 2.74 | 4.12 | 11.3 | 458.8 | 44.5 | 44.5 | 9.22 | 9.90 |

| 74 | Trachypithecus vetulus | 4.9996 | 29.2 | 35.7 | 17.2 | 21.5 | 1.1 | 1.54 | 1.92 | 7.2 | 9 | 480.3 | 42.3 | 42.3 | 9.03 | 9.64 |

| 75 | Lutrogale perspicillata | 5.1002 | 29.2 | 35.6 | 17.1 | 21.4 | 1.1 | 4.85 | 4.85 | 6.22 | 15.2 | 478.9 | 56.1 | 56.1 | 10.83 | 12.76 |

| 76 | Chlorocebus pygerythrus | 5.3005 | 29.1 | 35.4 | 17.1 | 21.2 | 1.1 | 1.21 | 4.26 | 8.08 | 8.9 | 507.6 | 37.1 | 37.1 | 9.58 | 10.70 |

| 77 | Lutra lutra | 5.3253 | 29.1 | 35.4 | 17.0 | 21.2 | 1.1 | 6.11 | 5.14 | 4.78 | 25.5 | 491 | 64.2 | 64.2 | 12.38 | 15.20 |

| 78 | Proteles cristata | 5.3998 | 29.0 | 35.3 | 17.0 | 21.1 | 1.1 | 2.43 | 9.06 | 3.99 | 18.2 | 506.3 | 42.4 | 42.4 | 11.44 | 13.97 |

| 79 | Agouti paca | 5.4599 | 29.0 | 35.3 | 17.0 | 21.0 | 1.1 | 2.22 | 1.76 | 3.21 | 14 | 524.8 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 10.04 | 10.49 |

| 80 | Macaca nigra | 5.5997 | 28.9 | 35.2 | 16.9 | 20.9 | 1.1 | 1.86 | 2.39 | 10.52 | 9.5 | 535.7 | 44.1 | 44.1 | 9.95 | 10.98 |

| 81 | Puma yagouaroundi | 5.9007 | 28.8 | 35.0 | 16.8 | 20.6 | 1.1 | 3.91 | 2.96 | 4.3 | 11.6 | 567.3 | 47.1 | 47.1 | 10.60 | 11.40 |

| 82 | Hylobates concolor | 6.5502 | 28.6 | 34.5 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 1.1 | 3.52 | 5.82 | 13.78 | 29.3 | 602.6 | 57.9 | 57.9 | 14.08 | 17.55 |

| 83 | Prionailurus viverrinus | 7.3003 | 28.3 | 34.1 | 16.3 | 19.4 | 1.0 | 5.59 | 3.35 | 5.29 | 16 | 699.8 | 51.0 | 51.0 | 12.78 | 13.99 |

| 84 | Macropus agilis | 7.7003 | 28.2 | 33.9 | 16.2 | 19.2 | 1.0 | 4.63 | 6.02 | 3.08 | 20.3 | 736 | 45.7 | 45.7 | 13.71 | 15.33 |

| 85 | Lontra canadensis | 7.9003 | 28.1 | 33.8 | 16.1 | 19.0 | 1.0 | 7.47 | 5.41 | 4.25 | 25.5 | 747.4 | 56.8 | 56.8 | 14.83 | 17.15 |

| 86 | Dolichotis patagonum | 8.4296 | 28.0 | 33.5 | 16.0 | 18.7 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 6.51 | 3.65 | 15.8 | 813.4 | 37.0 | 37.0 | 13.72 | 15.00 |

| 87 | Symphalangus syndactylus | 8.5002 | 28.0 | 33.5 | 15.9 | 18.7 | 1.0 | 4.37 | 5.15 | 14.3 | 29.4 | 796.8 | 54.3 | 54.3 | 15.87 | 18.81 |

| 88 | Colobus guereza | 9.7498 | 27.6 | 32.9 | 15.6 | 18.0 | 1.0 | 2.33 | 3.7 | 8.65 | 17.1 | 943.2 | 36.5 | 36.5 | 14.79 | 15.66 |

| 89 | Felis chaus | 9.7999 | 27.6 | 32.9 | 15.6 | 18.0 | 1.0 | 8.19 | 4.83 | 4.97 | 15.3 | 946.7 | 48.0 | 48.0 | 15.26 | 16.77 |

| 90 | Lynx canadensis | 10.0003 | 27.6 | 32.8 | 15.6 | 17.9 | 1.0 | 5.49 | 3.88 | 8.26 | 15.8 | 966.6 | 43.4 | 43.4 | 15.26 | 16.45 |

| 91 | Dog | 10 | 27.6 | 32.8 | 15.6 | 17.9 | 1.0 | 7 | 8.5 | 7.5 | 42 | 935 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 18.73 | 22.64 |

| 92 | Hystrix indica | 11.2543 | 27.3 | 32.4 | 15.3 | 17.3 | 1.0 | 5.24 | 5.62 | 4.07 | 25.5 | 1085 | 42.0 | 42.0 | 17.39 | 18.81 |

| 93 | Theropithecus gelada | 11.4021 | 27.3 | 32.3 | 15.3 | 17.3 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 7.72 | 14.09 | 23.6 | 1091 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 17.83 | 20.31 |

| 94 | Pudu puda | 12.898 | 27.0 | 31.9 | 15.0 | 16.7 | 0.9 | 1.99 | 5.05 | 6.16 | 20.6 | 1256 | 29.5 | 29.5 | 17.75 | 18.41 |

| 95 | Gazella gazella | 14.9969 | 26.7 | 31.3 | 14.7 | 16.0 | 0.9 | 4.06 | 12 | 7.93 | 32.7 | 1443 | 34.9 | 34.9 | 21.79 | 24.58 |

| 96 | Castor fiber | 15.5662 | 26.6 | 31.2 | 14.6 | 15.9 | 0.9 | 7.83 | 4.4 | 4.89 | 34.5 | 1505 | 44.1 | 44.1 | 21.97 | 23.47 |

| 97 | Macaca arctoides | 15.87 | 26.5 | 31.1 | 14.6 | 15.8 | 0.9 | 5 | 6.1 | 11.8 | 24.1 | 1540 | 35.8 | 35.8 | 21.30 | 22.85 |

| 98 | Lynx lynx | 17.5008 | 26.3 | 30.7 | 14.4 | 15.4 | 0.9 | 7.95 | 9.3 | 9.43 | 26.4 | 1697 | 37.4 | 37.4 | 23.35 | 25.65 |

| 99 | Capreolus capreolus | 20 | 26.0 | 30.3 | 14.1 | 14.8 | 0.9 | 8 | 16 | 10 | 48 | 1918 | 39.3 | 39.3 | 27.93 | 32.35 |

| 100 | Cuon alpinus | 19.9964 | 26.0 | 30.3 | 14.1 | 14.9 | 0.9 | 7.64 | 15.8 | 11.6 | 34.6 | 1930 | 35.2 | 35.2 | 26.68 | 30.54 |

| 101 | Dog | 20.388 | 26.0 | 30.2 | 14.1 | 14.8 | 0.9 | 9.2 | 15.3 | 9.6 | 44.7 | 1960 | 39.6 | 39.6 | 27.98 | 32.17 |

| 102 | Mandrillus sphinx | 23.0249 | 25.7 | 29.8 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 0.9 | 4.99 | 7.6 | 16.8 | 33.1 | 2240 | 32.2 | 32.2 | 27.95 | 29.87 |

| 103 | Papio hamadryas | 23.2493 | 25.7 | 29.7 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 0.9 | 8.03 | 10.3 | 17.4 | 39.2 | 2250 | 37.4 | 37.4 | 29.35 | 32.45 |

| 104 | Zalophus californianus | 33.9579 | 24.9 | 28.4 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 0.8 | 20.59 | 16.8 | 31 | 127.4 | 3200 | 54.7 | 54.7 | 45.67 | 56.18 |

| 105 | Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris | 33.9875 | 24.9 | 28.4 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 0.8 | 10.35 | 10.4 | 8.4 | 69.6 | 3300 | 36.1 | 36.1 | 39.32 | 42.20 |

| 106 | Canis lupus chanco | 38.0209 | 24.7 | 28.1 | 12.9 | 12.5 | 0.8 | 20.69 | 30.3 | 14 | 97.1 | 3640 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 46.66 | 56.35 |

| 107 | Sheep | 52.006 | 24.0 | 27.0 | 12.3 | 11.5 | 0.8 | 16 | 28 | 10.6 | 96 | 5050 | 32.5 | 32.5 | 54.93 | 61.68 |

| 108 | Reference women | 58.015 | 23.8 | 26.7 | 12.1 | 11.2 | 0.7 | 27.5 | 24 | 120 | 140 | 5490 | 51.8 | 51.8 | 65.07 | 83.63 |

| 109 | Human | 59.97 | 23.8 | 26.6 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 0.7 | 25 | 32 | 130 | 170 | 5640 | 51.4 | 51.4 | 68.58 | 90.32 |

| 110 | Reference man | 70.04 | 23.5 | 26.1 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 0.7 | 31 | 33 | 140 | 180 | 6620 | 50.8 | 50.8 | 75.95 | 98.83 |

| 111 | Panthera tigris altaica | 74.9716 | 23.3 | 25.9 | 11.7 | 10.4 | 0.7 | 42.46 | 30.5 | 34.2 | 110 | 7280 | 41.6 | 41.6 | 72.84 | 84.70 |

| 112 | Hog | 125.33 | 22.3 | 24.4 | 10.9 | 9.1 | 0.6 | 26 | 35 | 12 | 160 | 12300 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 102.80 | 109.95 |

| 113 | Dairy cow | 487.9 | 20.0 | 20.8 | 9.0 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 116 | 188 | 40 | 646 | 47800 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 308.50 | 353.68 |

| 114 | Horse | 600.28 | 19.6 | 20.3 | 8.7 | 6.0 | 0.5 | 166 | 425 | 67 | 670 | 58700 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 366.40 | 457.67 |

| 115 | Steer | 699.8 | 19.4 | 19.9 | 8.5 | 5.7 | 0.5 | 100 | 230 | 50 | 500 | 69100 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 392.43 | 434.45 |

| 116 | Elephant | 6650.4 | 16.1 | 15.2 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 120 | 220 | 570 | 630 | 7E+05 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2292.18 | 2327.20 |

Appendix B

| 1 | 50-70 kg Human brains indicate jump in masses from 1.2 kg to 1.4 kg compared to sheep of comparable body mass of 52 kg with mBr= 0.11kg. Human. |

| 2 | Same as footnote (a). |

| 3 | Elia values for “ek” are [8]: Kids, H, Br, L, SM,AT, RM-ex 2: 21.3, 21.3, 11.62, 9.7, 0.63 , 0.22, 0.58 W/kg [12] and fk = 0; mRM-ex2 = MB-mvit-mSM-mAT. |

| 4 | Krebs report that the SOrMRk of organs decreases with an increase in body mass, and the order of decrease is the same as the decrease in SBMR of the body [54]. The constants ck,6, dk,6 etc., are based on data from six species [11] and ck,116, dk,116 etc., are based on 116 species [14]. |

| 5 | Elia constant SOrMRk (W/kg) for Kids, H, Br, L and RM: i.e., ek, 21.3, 21.3, 11.62, 9.7, and 0.58 W/kg and fk for Elia = 0. |

| 6 | Later et al. [141], for species MB: 70-80 kg, eR: 0.463 W/kg, fR = 0, qR,m = constant, AT mass isometric with body mass [31]. |

| 7 | Ref. [41] cites Hepatocytes: fk = -0.17 to 0.21; kidney cortex: –0.11 to –0.07, brain: –0.07, spleen: –0.14 and lung: –0.10. |

| 8 | For SM based on 49 species, ck,49= 0.061, dk,49 =1.09, MB from 0.006 to 6600 kg [31]. |

| 9 | Gutierrez: kidneys mK ∝ mB 0.85; for liver mL ∝ mB 0.87 to 0.89 [270]. |

| 10 | Allometric relation for mass of RM yields different values compared to mRM= MB – mbital where mbital is based on allometric constants. |

References

- Popovic, M. , " Thermodynamic properties of microorganisms: determination and analysis of enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy of biomass, cells and colonies of 32 microorganism species,," Heliyon 2019, 5, e0195.

- Popovic M, "Beyond COVID-19: Do biothermodynamic properties allow predicting the future evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants? Microbial Risk Analysis, 1002; 22, 100232. [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, K. , "Oxygen Deficient (OD) Combustion and Metabolism: Allometric Laws of Organs and Kleiber’s Law from OD Metabolism? Journal: Systems 2021, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, M. , "Body size and metabolism. ," Hilgardia. 1932, 6, 315–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, M. , The fire of life: An introduction to animal energetics, NY: Krieger, 1961.

- White C R and Seymour R S,, "Revew-Allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism,". The Journal of Experimental Biology, The Company of Biologists 2005, 208, 1611–1619. [CrossRef]

- West GB, Brown JH, Enquist BJ., "A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology.,". Science 1997, 276, 122–126. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppeler, H. and Weibel, E R,, "On Scaling functions to body size: theories and facts-Editorial,," Special Issue is dedicated toThe Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 208, no. Special Issue is dedicated to Knut Schmidt-Nielsen,The Company of Biologists, pp. 1573-74, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Banavar, J. R. , Maritan, A. & Rinaldo A, "Size and form in efficient transportation networks,". Nature 1999, 399, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bejan A, In Shape and Structure, from Engineering to Nature, p 260-266, Cambridge: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press., 2000.

- Bejan A, "The constructal law of organization in nature: tree-shaped flows and body size. ," J Exp Biol 2005, 208, 1677–1686. [CrossRef]

- Singer, D. , "Size relationship of metabolic rate: oxygen availability as the “missing link” between structure and function? ”, Review," Thermochimica Acta 2006, 446, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trayhun, P. , "Oxygen—A Critical, but Overlooked, Nutrient,". Front. Nutr.,HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY ARTICLE 2019, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G. B. , Brown, J. H. and Enquist, B. J., "The fourth dimension of life: fractal geometry and allometric scaling of organisms.,". Science 1999, 284, 1677–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter PR, ".Allometric scaling of the maximum metabolic rate of mammals: oxygen transport from the lungs to the heart is a limiting step.,". Theor Biol Med Model. 2005, 11, 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weibel ER, Hoppeler H, " Exercise-induced maximal metabolic rate scales with muscle aerobic capacity.,". J Exp Biol, 2005, 208, 1635–1644. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva J K L, Garcia G J M, Barbosa L A,, "Allometric scaling laws of metabolism,". Physics of Life Reviews, 2006, 3, 229–261. [CrossRef]

- Painter, P. , "Rivers, blood and transportation networks.,". Nature 2000, 408, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetrius, L. , "Demetrius, L.Directionality theory and the evolution of body size.,". Proc. R. Soc. Lond., 2000, 267, 2385–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Zhang J, Ying Z, Heymsfield S. B., "Organ-Tissue Level Model of Resting Energy Expenditure Across Mammals: New Insights into Kleiber’s Law," International Scholarly Research Network ISRN Zoology., no. Article ID 673050,, p. 9 pages, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, O'Connor TP, Heshka S, Heymsfield SB., "The reconstruction of Kleiber's law at the organ-tissue level,". J.Nutr., 2001, 131, 2967–70. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Ying Z, Bosy-Westphal A, Zhang J, Schautz B, Later W., "Specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues across adulthood: evaluation by mechanistic model of resting energy expenditure,". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010, 92.

- Gallagher, D.; Belmonte, D.; Deurenberg, P.; Wang, Z.M.; Krasnow, N.; Pisunyer, F.X.; Heymsfield, S.B. , "Organ-tissue mass measurement allows modeling of REE and metabolically active tissue mass,,". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 1998, 38, E249–E258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoł A, Kozłowski J,, "Scaling of organ masses in mammals and birds: phylogenetic signal and implications for metabolic rate scaling,,". ZooKeys 2020, 9821, 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Annamalai K, Ryan W., "Interactive processes in gasification and combustion- I: Cloud of droplets,". Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 1993, 19, 383–446.

- Annamalai K, Ryan W.,, "Interactive processes in gasification and combustion- II: Isolated carbon/coal and porous char particles,". Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 1993, 19, 383–446. [CrossRef]

- Annamalai,K., Ryan,W. and Dhanapalan,S., "Interactive processes in gasification and combustion-III: Coal particle arrays, streams and clouds,". Journal of the Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 1994, 20, 487–618. [CrossRef]

- Kapteijn F, Marin G B, Moulijn J.A., "Catalytic reaction engineering, in Catalysis: an integrated approach," NY, Elsevier, Hardcover ISBN: 9780444829634, 1999.

- Annamalai, K. and Nanda, A., "Biological aging and life span based on entropy stress via organ and mitochondrial metabolic loading,". Entropy 2017, 19, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, M. , "Organ and tissue contribution to metabolic rate," in Energy metabolism: tissue determinants and cellular corollaries, New York, Raven Press, Ltd, 1992, pp. 61-79.

- Groebe K, " An Easy-to-Use Model for 02 Supply to Red Muscle, Validity of Assumptions, Sensitivity to Errors in Data,,". Biophysical Journal 1995, 68, 1246–1269. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pias S C, "How does oxygen diffuse from capillaries to tissue, Symposium Review,". J Physiol 2021, 1769–1782.

- Singer D, Schunck O, Bach F, Kuhn HJ., "Size effects on metabolic rate in cell, tissue, and body calorimetry.,". Thermochimica Acta 1995, 251, 227–240. [CrossRef]

- Place TL, Domann FE, Case AJ., " Limitations of oxygen delivery to cells in culture: An underappreciated problem in basic and translational research.,". Free Radic Biol Med 2017, 113, 311–322. [CrossRef]

- Schumacker PT, Samsel RW, "Analysis of oxygen delivery and uptake relationships in the Krogh tissue model. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1989 Sep;67(3):1234-44. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1989, 67, 1234–44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton WW, Chandel NS., " Hypoxia. 2. Hypoxia regulates cellular metabolism.,". Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011, 300, C385–93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WANG, R., HUSSAIN, A., GUO, Q., JIN, X., WANG, M.., "Oxygen and Iron Availability Shapes Metabolic Adaptations of Cancer Cells.," World Journal of Oncology, North America, no. Available at: .

- Melkonian EA, Schury MP., " Biochemistry, Anaerobic Glycolysis. [Updated 2023 Jul 31].," Treasure Island (FL), In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing;; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546695/, 2024.

- Zheng, J. , "Energy metabolism of cancer: Glycolysis versus oxidative phosphorylation (Review). ," Oncol Lett. 2012, 4, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Avaiabke online https://www.webmd.com/cancer/cancer-incidence-age (accessed on 11/19/2024.

- Accesed on 09/10/2024, Ratcliffe group | Hypoxia biology in cance; Accessed 06/17/2024 https://www.ck12.org/book/human-biology-circulation/section/5.1/ ].

- Grant H et.al. and 18 other authors, "Larger organ size caused by obesity is a mechanism for higher cancer risk," bioRxiv, no. 2020.07.27.223529; [CrossRef]

- Piiper P, Scheid J., "Cross-sectional PO2 distributions in Krogh cylinder and solid cylinder models,". Respir Physiol 1986, 64, 241–251. [CrossRef]

- Smil V, "Laying down the law, Millennium Essay," Nature, vol. 403, no. www.nature.com, p. 597, 2000.

- Morisaki H, Sibbald W J, "Tissue oxygen delivery and the microcirculation,,,,". Critical Care Clinics 2004, 20, 213–223. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostergaard L,, " Blood flow, capillary transit times, and tissue oxygenation: the centennial of capillary recruitment,,". Journal of Applied Physiology 2020, 129, 1413–1421. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A.M. Makarieva, V.G. A.M. Makarieva, V.G. Gorshkov, B. Li, S.L. Chown, P.B. Reich, V.M. Gavrilov,, "Mean mass-specific metabolic rates are strikingly similar across life's major domains: Evidence for life's metabolic optimum,". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16994–16999. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Makarieva, V.G. A.M. Makarieva, V.G. Gorshkov, B. Li, S.L. Chown, P.B. Reich, V.M. Gavrilov,, "Mean mass-specific metabolic rates are strikingly similar across life's major domains: Evidence for life's metabolic optimum,,". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 16994–16999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt SL, Schaeffer PJ., " Use of allometry in predicting anatomical and physiological parameters of mammals.,". Lab Anim., 2002, 36, 1–19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holliday M A, Potter, D, Arrah A and Bearg S,, " The Relation of Metabolic Rate to Body Weight and Organ Size, A Review,,". Pediat. Res. 1967, 1, 185–195. [CrossRef]

- shcroft S P, Stocks B, Egan B, Zierath J R, " Exercise induces tissue-specific adaptations to enhance cardiometabolic health,,". Cell Metabolism 2024, 36, 278–300. [CrossRef]

- Wendt, D. , van Loon, L.J. & Marken Lichtenbelt, W.D., " Thermoregulation during Exercise in the Heat.,". Sports Med 2007, 37, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DELMAR, R. FINCO,, " Chapter 9 Kidney Function, KANEKO,J R, editor,," in Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals (Third Edition),, Academic Press, ISBN 9780123963505, 1980, pp. 337-400. [CrossRef]

- Joyner M J and Casey D P, "Regulation of Increased Blood Flow (Hyperemia) to Muscles During Exercise: A Hierarchy of Competing Physiological Needs,,". Physiological Reviews 2015, 95, 549–601. [CrossRef]

- Angleys, H, Østergaard, L, "Krogh’s capillary recruitment hypothesis, 100 years on: Is the opening of previously closed capillaries necessary to ensure muscle oxygenation during exercise?,". American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2019, H425–H447. [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, I, Kalliokoski K, K Hannukainen,J C, Duncker D J, Nuutila,P and Knuuti J,, "Organ-Specific Physiological Responses toAcuteP hysical Exercise and Long-Term Trainingi n Humans,,". Int.Union Physiol.Sci., Am.Physiol.Soc. Physiology 2014, 29, 421–436. [CrossRef]

- Wasserman DH, Cherrington AD., " Hepatic fuel metabolism during muscular work: role and regulation.,". Am J Physiol 1991, 260, E811–24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa L A,Garcia G J M, da Silva J K L,, "The scaling of maximum and basal metabolic rates of mammals and birds, ,,". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2006, 359, 547–554. [CrossRef]

- Accessed on 12/21/2024 https://health.howstuffworks.com/wellness/diet-fitness/exercise/sports-physiology8.htm, posted by By: Craig Freudenrich, Ph.D.

- Smith K J and Ainslie P N,, " Regulation of cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise,". Exp Physiol, 2017, 102, 1356–1371. [CrossRef]

- Ahulwalia A., "Allometric scaling in-vitro, Scientific Reports, 7:42113 | DOI: 10.1038/srep42113," www.nature.com/scientificreports, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Prange H D, Anderson J F and Rahn H, "Scaling of Skeletal Mass to Body Mass in Birds and Mammals. The American Naturalist, 1979, 113, 103–12. [CrossRef]

- Kayser, C. , and A. Heusner. 1964., "Etude comparative du metabolism &Energetique dans la s&rie animale.,". J. Physiol. (Paris), 1964, 56, 489–524. [Google Scholar]

- White, "Metabolic Scaling in Animals: Methods, Empirical," no. [CrossRef]

- Midorikawa T, Tanaka S, Ando T, Tanaka C, Masayuki K, Ohta M, Torii S, Sakamoto S, "Is There a Chronic Elevation in Organ-Tissue Sleeping Metabolic Rate in Very Fit Runners?,". Nutrients 2016, 8, 196. [CrossRef]

- Korthuis RJ., "Skeletal Muscle Circulation. Ed. San Rafael (CA)," in Chapter 4, Exercise Hyperemia and Regulation of Tissue Oxygenation During Muscular Activity., Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences;, Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK57139/, 2011.

- Tayor et al, "Resp Physio," vol. 44, pp. 25-37, 1981.

- Weibel ER, Bacigalupe LD, Schmitt B, Hoppeler H., "Allometric scaling of maximal metabolic rate in mammals: muscle aerobic capacity as determinant factor.,". Resp Physiol Neurobiol 2004, 140, 115–32. [CrossRef]

- De Moraes R, Gioseffi G, Nóbrega AC, Tibiriçá E., "Effects of exercise training on the vascular reactivity of the whole kidney circulation in rabbits.,". J Appl Physiol 1985, 97, 683–8. [CrossRef]

- Poortmans, JR. , " Exercise and renal function.1,". Sports Med 1984, 1, 125–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindstedt SL, Hoppeler H., "Allometry: revealing evolution's engineering principles.,". J Exp Biol., 2023, 226, jeb245766. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agutter PS, Wheatley DN., "Metabolic scaling: consensus or controversy? Theor Biol Med Model., 2004, 1. [CrossRef]

- Pryce, and 11 additional authors, "Reference ranges for organ weights of infants at autopsy: Results of >1,000 consecutive cases from a single centre.,". BMC clinical pathology 2014, 14, 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packard, G.C. , "Rethinking the metabolic allometry of ants. Evol Ecol 2020, 34, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, TH. , "Scaling laws for capillary vessels of mammals at rest and in exercise,". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2003, 270, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert A J, "A Sceptics View: “Kleiber’s Law” or the “3/4 Rule” is neither a Law nor a Rule but Rather an Empirical Approximation,". Systems 2014, 2, 186–202. [CrossRef]

- Krebs, AH. , "Body size and tissue respiration,". Biochem. et Biophys. Acta, 1950, 4, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, RK. , "Allometry of mammalian cellular oxygen consumption,". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, WR. , "xSite model of allometric scaling and fractal distribution networks of organs," [https://arxiv.org/pdf/q-bio/0404039], accceesed Feb 26 2019.

- Later W, Bosy-Westphal A, Hitze B, Kossel E, Glüer CC, Heller M, Müller MJ., "No evidence of mass dependency of specific organ metabolic rate in healthy humans.,". Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 4, 1004–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier D S, "Beyond the ’3/4-power law’: variation in the intra- and interspecific scaling of metabolic rate in animals,". Biological Reviews 2005, 80, 611–662. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier, D.S. , "Body-Mass Scaling of Metabolic Rate: What are the Relative Roles of Cellular versus Systemic Effects?,". Biology 2015, 4, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C., " Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia.,". J Cell Mol Med., 2011, 15, 1239–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner BA, Venkataraman S, Buettner GR., " The rate of oxygen utilization by cells.,". Free Radic Biol Med. 2011, 51, 700–712. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage VM, Allen AP, Brown JH, Gillooly JF, Herman AB, Woodruff WH, West GB., "Scaling of number, size, and metabolic rate of cells with body size in mammals.,". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 4718–23. [CrossRef]

- W. Ryan, K. Annamalai and J. Caton,, "Relation between Group Combustion and Drop Array Studies,,". Combustion and Flame 1990, 80, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Hess; J R, " Diffusion-limited oxygen delivery. Blood 2024, 143, 659–660. [CrossRef]

- White C R, Seymour R S, "Mammalian basal metabolic rate is propor- tional to body mass 2/3,,". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 4046–4049. [CrossRef]

- Dodds, P S, Rothman D.H., Weitz J S, "Re-examination of the “3/4-law” of metabolism,,". J. Theor. Biol. 2001, 209, 9–27. [CrossRef]

- White C R and Seymour R S, "Revew-Allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism, vol. , no. T," he Journal of Experimental Biology, 2005, 208, 1611–1619. [CrossRef]

- Lee SY, Gallagher D., "Assessment methods in human body composition.,". Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008, 5, 566–72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- "Scaling of Skeletal Mass to Body Mass in Birds and Mammals".

- Heymsfield S B, Gallagher D, Kotler D P, Wang Z, Allison D B, Heshka S, ",ody-size dependence of resting energy expenditure can".

- Heymsfield S B , Gallagher D, Kotler D P, Wang Z , Allison D B , Heshka S, "Body-size dependence of resting energy expenditure can be attributed to nonenergetic homogeneity of fat-free mass,,". Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002, 282, E132:E138.

- Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age#:~:text=Age%20and%20Cancer%20Risk,-Advancing%20age%20is&text=The%20incidence%20rates%20for%20cancer,groups%2060%20years%20and%20older.(accessed on 17th Nov 2024).

- Sarelius I and, U. Pohl, "Control of muscle blood flow during exercise: Local factors and integrative mechanisms,,". Acta Physiologica 2010, 199, 349–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groebe, K, "An Easy-to-Use Model for 02 Supply to Red Muscle, Validity of Assumptions, Sensitivity to Errors in Data,,". Biophysical Journal 1995, 68, 1246–1269. [CrossRef]

- Accessed 12/25/2024 https://www.physio-pedia.com/VO2_Max#:~:text=The%20simplest%20formula%20to%20calculate,mL/kg/min).

- Javed F, He Q, Davidson LE, Thornton JC, Albu J, Boxt L, Krasnow N, Elia M, Kang P, Heshka S, Gallagher D., "Brain and high metabolic rate organ mass: contributions to resting energy expenditure beyond fat-free mass.,". Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 4, 907–912. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzer, "Carbohydrate and fat utilization during rest and physical activity," The European e-Journal of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, vol. 6, 2011.

- Hryvniak D, Wilder R P, Jenkins J, Statuta S, ", Chapter 15 - Therapeutic Exercise, Editor(s): David X. Cifu,," in Braddom's Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Sixth Edition), NY, Elsevier 2011, pp. 291-315. [CrossRef]

| Organ | ρk, g/cc | ck,6, 1 kg | dk,62 | ek,6 3 | fk,6 4 | mk (85 kg human) | Ek,6 | Fk,6 | (85 kg human) | ck,116 [3] |

dk,116 [3] |

OEFk) 84 kg human) |

| Kidneys (Kids)5 | 1.05 | 0.007 | 0.85 | 33.41 | -0.08 | 0.31 | 20.94 | -0.094 | 0.11 | 0.00631 | 0.728 | 0.085 |

| Heart (H) | 1.06 | 0.006 | 0.98 | 43.11 | -0.12 | 0.47 | 23.04 | -0.122 | 0.15 | 0.00580 | 0.932 | 0.48 |

| Brain (Br) | 1.036 | 0.011 | 0.76 | 21.62 | -0.14 | 0.32 | 9.42 | -0.184 | 0.044 | 0.0108 | 0.886 | 0.37 |

| Liver (L) | 1.06 | 0.033 | 0.87 | 33.11 | -0.27 | 1.57 | 11.49 | -0.310 | 0.19 | 0.0286 | 0.872 | 0.52 |

| RM6 | 0.939 | 1.01 | 1.45 | -0.17 | 83.44 | 1.44 | -0.168 | 0.19 | 0.940 | 1.007 |

| Organ | Rest (mL/min) | Mild Exer(mL/min) | Maximal (mL/min) | Rest % | Exercise % | EX-Rest ratios |

| Kidney | 1100 | 900 | 600 | 19 | 3 | 0.55 |

| Heart | 250 | 350 | 750 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Brain | 750 | 750 | 750 | 13 | 4 | 1 |

| Others (i.e., liver, spleen) | 600 | 400 | 400 | 10 | 2 | 0.67 |

| Skeletal muscle | 1200 | 4500 | 12500 | 21 | 71 | 10.42 |

| RM-Ex (GI+skin+others) | 2500 | 3000 | 2900 | 43 | 17 | 1.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).