Introduction

Cellular function is typically classified by organizing biological features according to subcellular localization, molecular function or biological process (Marshall et al., 2021; Bordenstein and The Holobiont Biology Network, 2024; Schultz et al., 2025). These classifications have supported the annotation and comparative analysis of genes across species and experimental contexts (Prokopenko et al., 2024; Schaffer et al., 2025). However, these classifications primarily reflect molecular identity or spatial localization rather than the coordinated cellular activity (Feuermann et al. 2025), not adequately capturing the role of energy in structuring and constraining cellular behaviour. In turn, the field of bioenergetics addresses the chemistry of intracellular energy transformations, but it lacks a modular and systemic classification linking energy demand and usage to cellular organization (Cox and Smith 2014; Streit et al. 2024; Ryu et al. 2024). Similarly, systems biology often incorporates energy balance into modelling frameworks but does not provide a comprehensive taxonomy of cellular modules based on their energetic roles (Schmidt et al. 2021). As a result, a conceptual gap remains between molecular-level descriptions and a systems-level understanding of cellular functions organized around energy flow, constraints and regulation. A framework linking energy dynamics to modular cell architecture could clarify how life maintains continuity under variable conditions and how cells prioritize function when resources are limited. To address this gap, we propose a modular classification scheme that groups cellular functions and features according to their role in energy transformation, flow and management, rather than their molecular type.

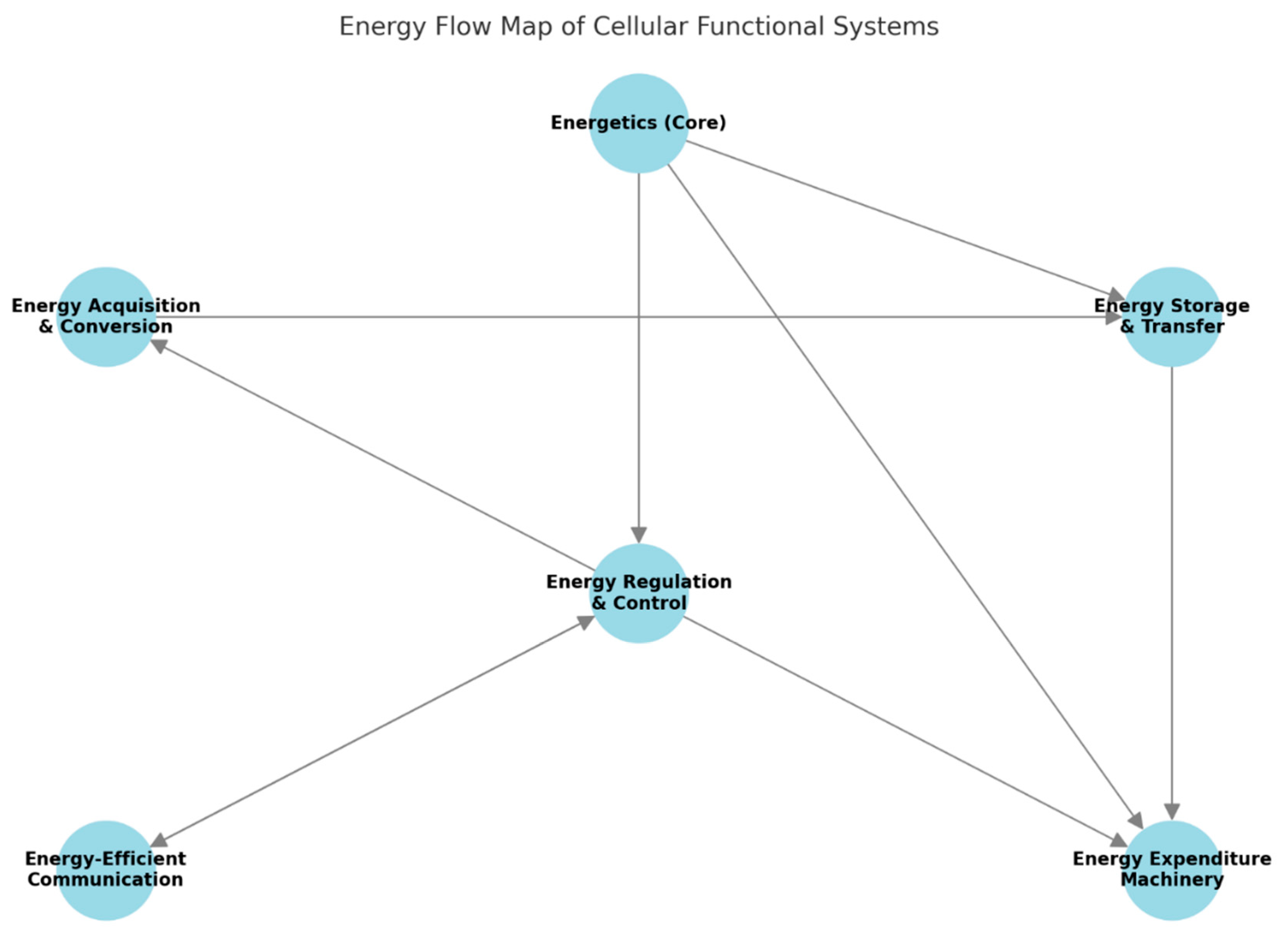

Our approach departs from traditional taxonomies that emphasize chemical identity or spatial localization and instead introduces an architecture that reflects how energy is acquired, stored, used and redistributed to keep cellular viability. The goal is to define functional modules not by what they are made of or where they reside, but by the energetic roles they fulfill within the system. We organize cellular systems into six primary energy-oriented modules (

Figure 1):

The first module, ENERGY ACQUISITION AND CONVERSION, includes all systems responsible for capturing external energy and converting it into biochemical energy forms usable within the cell. Examples include photosystems in photosynthetic organisms, glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, electron transport chains, ATP synthase complexes and fermentation pathways.

The second module, ENERGY STORAGE AND TRANSFER MOLECULES, groups components that retain and shuttle energy in usable form. This includes ATP, NADH, GTP, lipid droplets, glycogen granules and high-energy intermediates such as phosphocreatine.

The third module, ENERGY EXPENDITURE MACHINERY, consists of all systems that use energy to perform cellular work. These include biosynthetic enzymes, ion pumps, ribosomes involved in translation and cytoskeletal motor proteins like myosin and kinesin. These systems are defined by their active energy consumption and their role in output generation.

The fourth module, ENERGY REGULATION AND CONTROL SYSTEMS, encompasses those mechanisms that sense the cell’s energetic status and adjust metabolic or functional activity accordingly. These include AMPK and mTOR pathways, redox balancing cycles such as the glutathione system and checkpoint regulators that monitor ATP/AMP or NAD⁺/NADH ratios.

The fifth module, ENERGY DISTRIBUTION NETWORKS, involves the cellular infrastructure that enables the spatial flow of energy and energy carriers. Structures such as mitochondrial reticula, cytoplasmic streaming mechanisms and membrane trafficking systems fall under this category. These systems do not generate or use energy directly, but instead facilitate its movement and availability across the cell.

The sixth module, ENERGY-EFFICIENT COMMUNICATION AND COORDINATION, describes systems that contribute to energy optimization at the multicellular or population level. This includes hormonal signaling (such as insulin and glucagon), metabolic coordination between adjacent cells and intercellular energy exchange via gap junctions or shared metabolites in tissues or microbial communities.

Next, we simulate how these modules behave under energy stress and recovery, aiming to assess differential resilience between modules and identify which ones are preserved or sacrificed under limitation. We will proceed as follows. We first describe the construction of the classification framework and define the boundaries of each energetic module. We then present a series of simulations that model energy depletion, recovery and prioritization dynamics. Finally, we discuss the significance of these results and the structural insights they provide into the energetic organization of cellular modules.

Methods

We describe here the methodology to build, formalize and simulate an energy-based modular classification of cellular modules. It includes the mathematical formulation of module boundaries, the structure of energetic interactions and the simulation protocols for depletion, prioritization and recovery.

Energetic functions structured into discrete modules. The first step in constructing our classification framework involved decomposing the set of cellular functions into modules according to their energetic role. This required an operational definition of what constitutes a distinct energetic function. We defined an energetic function as a transformation of energy over time, taking the general form , where and ′ represent equivalent or converted forms of energy within cellular context. For example, ATP hydrolysis was represented as , reflecting the transformation of chemical potential into mechanical or transport work plus entropy.

Cellular processes were grouped into six classes based on the dominant form of energy input and output, the sign of net energy change and the presence or absence of feedback regulation. For classification purposes, we constructed a function-to-system mapping , where represents one of the six energetic modules. To avoid ambiguity in multifunctional molecules (e.g. ATP), the assignment was constrained by a primary function criterion: a molecule or structure is placed within the module whose function it supports most directly under standard cellular conditions. Multifunctional elements such as ATP or mitochondria were assigned to modules where their principal energetic role is realized, even if they participate secondarily in other categories. For example, mitochondria are classified within acquisition and conversion despite also supporting distribution through spatial dynamics.

Defining module boundaries through matrix representation. Following the initial mapping, we formalized the module boundaries using adjacency matrices and process-energy coupling coefficients (Yu et al., 2018; Nath 2024). Let denote the set of cellular energetic functions and the energetic modules. We constructed a binary matrix such that if function belongs to module and zero otherwise. To quantify energy interactions between modules, we defined an energy coupling matrix , where is the average normalized energy transfer from module to module per unit time under standard metabolic fluxes. Each entry was computed using experimental flux data from standard mammalian cell models (CHO-K1 and HeLa) and normalized with respect to total ATP turnover (Fak et al., 2011). The normalized coupling was defined by , where is the subset of functions where module contributes energy to module . Sparse entries in were thresholded using a cutoff ϵ=10-3 to eliminate negligible transfers and self-interactions were retained to model internal feedback loops. This matrix defined the topology of energy flow and allowed module boundaries to be delineated not only by categorical assignment but also by quantitative interaction patterns. In this formulation, the modules are treated not as isolated entities but as weakly coupled energy transformers embedded in a dynamic network.

Simulation of cellular energy allocation. To investigate module behavior under dynamic energy conditions, we implemented a discrete-time simulation model. Let

be the time index and

the available energy pool for module

at time

. Total cellular energy

was set to vary according to predefined input curves simulating energy depletion and recovery scenarios. For each time step

, we updated module energy levels using the function:

where

are elements of the coupling matrix,

is the energy consumed by module

based on activity status and

is a saturation bound. Module activity was governed by a threshold rule:

was active at

if

, where

is a fixed energy activation threshold representing the minimum energy required for functionality. Each module was assigned a fixed activation threshold

between 0.3 and 0.8, representing its minimum energy requirement. Values were determined by estimating the relative ATP or GTP demand of each module class based on literature and standard metabolic costs. Energy-intensive modules like biosynthesis and transport received higher thresholds, while regulatory and coordination systems were assigned lower values.

Each simulation run consisted of 50-time steps (1 unit per step), with initial energy distributed evenly or weighted according to a given protection scheme. The simulation allowed us to track energy state evolution, module activation and the cascade of functional failures or recoveries.

Overall, the discrete-time model with energy thresholds and coupling dynamics served to encode temporal dependencies and nonlinear interactions among modules under varying resource constraints.

Stability and sensitivity to perturbation. To examine the effect of different stress patterns, namely, linear decline, sudden shock and oscillatory behavior, we defined three time-dependent energy input functions for simulation input:

a linear depletion function ,

a step shock function ,

and a sinusoidal fluctuation function .

The threshold values were calculated by mapping relative energy demands of each functional module to a normalized energy scale ranging from 0 to . Using literature-based approximations of ATP and GTP consumption, modules were ranked by metabolic cost, then rescaled to a [0.3, 0.8] interval. Additional simulation parameters included (scaling for depletion rate), 4 (amplitude for oscillatory stress), (oscillation frequency) and (shock onset), defining temporal energy input profiles for different stress scenarios.

Three prioritization schemes. Next, we examined how alternative energy allocation strategies influence module survival and resilience during depletion and recovery phases. Each strategy determined which modules remained functional under varying energy constraints. To achieve this, we tested three distinct approaches for distributing energy across cellular modules, each based on a different prioritization logic, allowing us to compare their impact on functional continuity under varying energy conditions:

The first treated all modules equally.

The second prioritized modules requiring less energy to stay active.

The third prioritized modules involved in regulation and communication.

To simulate prioritization strategies, we introduced a priority vector with elements representing the relative importance of maintaining module During energy allocation, available energy was assigned in descending order of and modules were allocated only if their energy demands could be met. Three prioritization schemes were evauated:

uniform ,

functional protection ,

and manual prioritization emphasizing regulation and communication.

The energy allocation algorithm applied a greedy strategy at each time step: iterate over sorted modules by and allocate if remaining energy . This framework enabled the evaluation of module viability under varying energy budget strategies, revealing how functional preservation depends on prioritization.

Recovery simulation. To simulate recovery dynamics, we inverted depletion functions and used recharging functions

or exponential models

. These models allowed us to examine whether moduless recover in the same sequence they fail or display hysteresis effects. However, to model biological inertia, we introduced a delay parameter

per module that represented reactivation latency even when energy thresholds were met. The energy update rule was modified as:

where

is the last time step when

became inactive. Delay values were set proportionally to energy demand

with

. This rule introduced a biologically realistic hysteresis where high-cost modules required longer recovery times even after sufficient energy was available. Modules with low

recovered quickly, reflecting robustness to transient energy loss. In addition, the model tracked false starts (activation followed by immediate deactivation) to quantify instability. Recovery simulations employed the same discretized time steps, threshold activation and energy transfer dynamics as depletion models, ensuring symmetry in comparison.

Overall, the incorporation of delay-dependent reactivation enriched the temporal dimension of the model, allowing exploration of reversible versus irreversible functional transitions in response to energy dynamics.

Tooling, implementation and verification. All simulations were implemented in Python 3.11: NumPy for numerical operations, Matplotlib for graphical rendering, SciPy for auxiliary computations and Pandas for data structuring. Code was developed in Jupyter Notebook and executed on a 12-core CPU module (AMD Ryzen 9, 64 GB RAM). Module interaction parameters were precomputed using symbolic matrix operations and stored as sparse matrices in SciPy’s compressed format. The core simulation engine ran deterministic updates of module energy states and activity flags over time. Outputs included binary activation matrices, energy curves and event timelines. Verification was conducted through internal consistency checks: energy conservation, activation-consumption alignment and state progression consistency. In cases of violation (e.g. negative energy, contradictory transitions), assertions halted execution and flagged errors. Parameter sensitivity was assessed by varying thresholds , coupling values and reactivation delays across multiple scenarios. Code and documentation were version-controlled with Git and tested across Python versions 3.9 through 3.11. All computational assets were executed in isolated virtual environments to ensure dependency integrity.

In conclusion, our methods establish a structured platform for modeling energy dynamics across modular cellular modules and functional viability under energetic constraints. Through computational simulations, we aim to define module boundaries, analyze inter-module dependencies and simulate stress/recovery scenarios.

Results

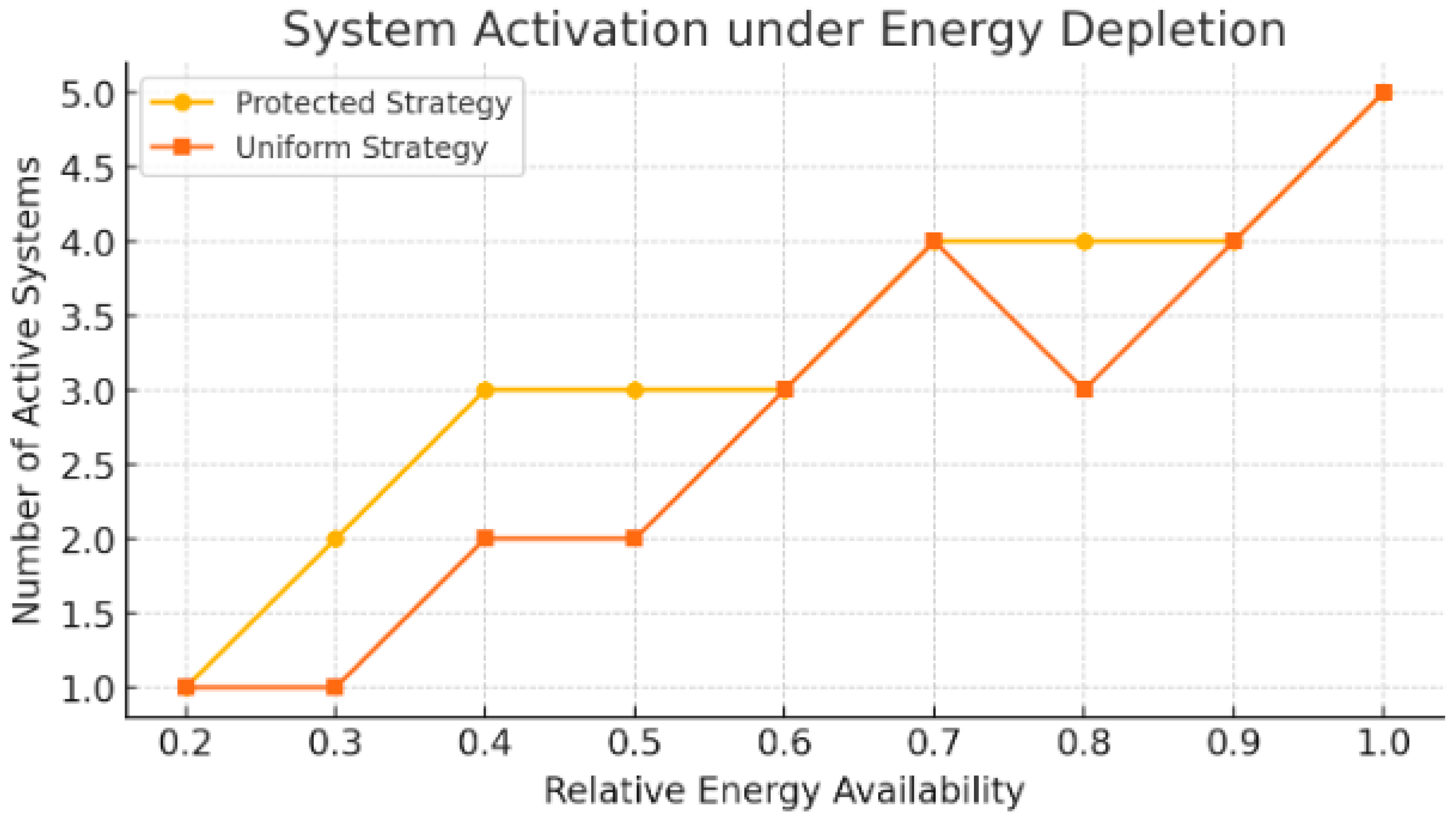

We present here the outcomes of simulation experiments designed to evaluate module behaviour under energy depletion and recovery, making comparisons between uniform and protection-based prioritization strategies. Quantitative metrics such as the number of active modules per time point and reactivation timing were used to assess functional continuity and resilience across different energy allocation scenarios.

The simulations conducted across nine stages of progressive energy decline demonstrated that the total number of active modules decreased predictably as energy availability dropped from 100% to 20% (

Figure 1):

Under a uniform prioritization strategy, five modules remained functional at full energy availability, but this number declined to one by the final time step. The activity profile was non-linear, with noticeable drops occurring between 80% and 60% energy availability, suggesting that several modules shared similar activation thresholds.

In contrast, when prioritization was adjusted to favor low-cost modules involved in regulation and communication, the number of functional modules remained higher in mid-stage energy levels. Specifically, at 40% and 50% availability, the protected prioritization strategy preserved three active modules compared to two under the uniform model. Across all stages, the protected strategy maintained equal or greater model activation at every time point except the first.

Quantitatively, the mean number of active models over the simulation period was 3.22 for the protected strategy and 2.78 for the uniform approach (paired t-test: p=0.05). This suggests that, during moderate-to-severe energy stress, the prioritization of low-demand regulatory and communication modules can increase overall functional continuity.

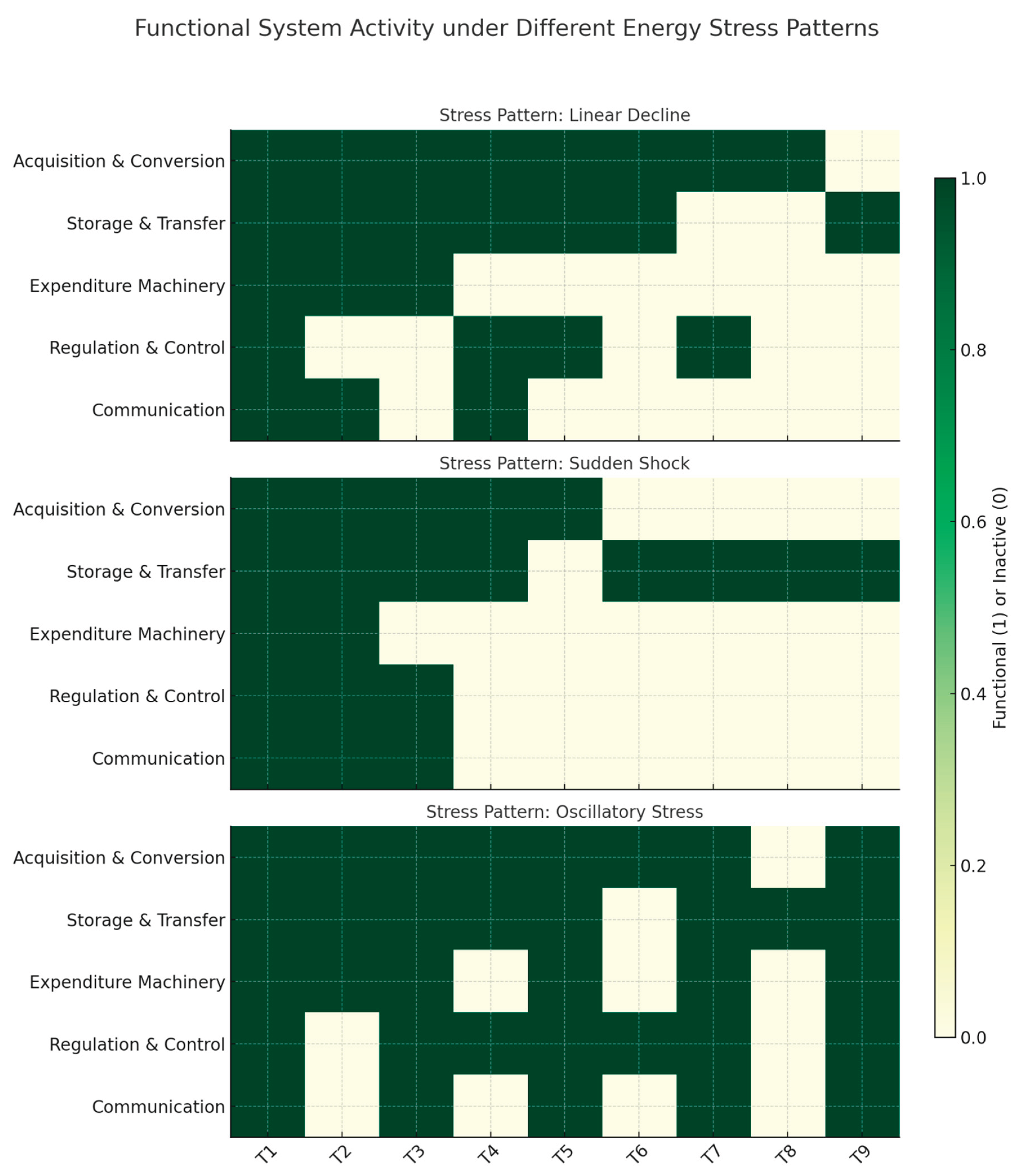

Next, we assessed functional module activity under different energy stress patterns. Different paths were identified (

Figure 2):

In the linear decline scenario, a gradual reduction in energy causes stepwise inactivation with higher-demand modules shutting down earlier.

In the sudden shock pattern, a sharp drop in energy availability after a short steady state results in abrupt and sustained functional loss in the more energy-intensive modules.

In the oscillatory pattern, fluctuating energy inputs cause repeated cycles of activation and deactivation, especially in borderline modules near their energy thresholds.

These patterns illustrate how different energy dynamics produce varying sequences of module failure or recovery, highlighting the temporal sensitivity of energy-dependent cellular functions.

The recovery phase followed the depletion simulation in reverse. Reactivation of modules occurred in a stepwise pattern, beginning with low-demand modules as energy levels increased.

Under uniform conditions, their reactivation occurred at 40% and 45% energy levels. This early reactivation created a phase of relative stability where communication and control functions were restored ahead of the higher-demand modules.

Under the protected strategy, communication and regulatory modules reactivated at 30% and 35% energy recovery, respectively. The protected strategy showed smoother transitions with fewer on-off fluctuations.

False reactivation events, defined as a module activating and then deactivating within two time steps due to energy inconsistency, occurred twice under the uniform strategy and only once under the protected strategy. When comparing the number of total functional time-points (defined as the cumulative active module count over the recovery timeline), the protected module showed a total of 29 versus 26 for the uniform one. Although this difference is modest, it reflects the cumulative effect of earlier reactivation and increased resilience of prioritized modules.

The recovery simulations thus revealed a persistent asymmetry between the depletion and restoration phases, with module order and energy delay parameters playing a central role in the pace and sequence of full functional restoration.

Overall, our results show that a protection-based prioritization strategy preserves more functional modules during energy depletion and supports earlier and more stable recovery of low-cost modules. Statistically significant differences in activation and reactivation profiles confirm the impact of energy-aware strategies on module viability. These findings underscore the role of strategic energy allocation in modular module dynamics.

Conclusions

Our simulations showed that cellular modules respond differently to energy stress, depending on their energy demand and the allocation strategy applied. We modeled six modules with distinct energetic functions and found that, under uniform allocation, high-demand modules often consumed available resources early, leading to loss of other critical but less energy-intensive functions. In contrast, prioritizing low-cost regulatory and communication modules preserved functionality across a broader range of energy levels and allowed more stable recovery. Quantitatively, the protected strategy maintained a higher number of active modules through moderate-to-severe depletion and achieved earlier reactivation during recovery. This was particularly evident under fluctuating or abrupt stress conditions, where resilience depended not just on absolute energy levels but also on the order of module reactivation and the presence of delay-induced hysteresis. The simulations confirmed that different stress patterns, namely, linear decline, sudden shock and oscillatory behavior, produce distinct activation trajectories. By integrating quantitative dynamics with categorical classification, we exposed patterns of resilience and failure that may not be visible under function-agnostic or purely molecular categorizations. Our exploration of recovery dynamics suggests that not all modules regain function in the same order in which they failed. The combination of threshold-dependent activation, inter-module coupling and prioritization strategies resulted in a rich range of functional outcomes across simulations.

Our approach interprets cellular modules by focusing on energy roles rather than molecular identity. Our modular classification organizes cellular functions into six energetically defined modules, each characterized by its primary role in acquiring, storing, utilizing or coordinating energy. This contrasts with traditional classifications based on molecular structure, spatial compartmentalization or biological process category (Avci et al., 2022; Feuermann et al., 2025). By integrating systemic roles with thermodynamic constraints, our model assesses how energy shapes the operation and organization of life at the cellular level. Unlike descriptive frameworks, our model is prescriptive and predictive. Simulating real-time model behavior based on quantifiable energetic parameters, it can highlight hidden trade-offs like the preservation of control mechanisms at the cost of high-demand execution modules. Additionally, the ability to simulate dynamic transitions adds explanatory power in contexts where function emerges or collapses based on limited energy availability. Our approach is able to connect structural features with functional behavior in energy-constrained conditions, providing a better understanding of the resilience and fragility of cellular functions when resources become limited or unstable. Moreover, our simulations produce interpretable metrics such as activation duration, recovery timing and false reactivation that are directly related to measurable module behavior.

Our top-down framework bridges molecular, metabolic, mechanical and informational dimensions by organizing them around energy transformation and management. This classification does not yet exist as a formal or unified system in the scientific literature, although related concepts appear in various specialized fields. In bioenergetics, the focus is on energy-producing and consuming pathways like glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation and on molecules like ATP and NADH, but not on broader functional systems like the cytoskeleton or ribosomes in terms of energy roles (Rigoulet et al., 2020; Lopaschuk et al., 2021). Metabolic network models like flux balance analysis account for energy flow and thermodynamic feasibility, yet they do not classify cellular structures or processes modularly by energetic function (Anand et al., 2020; Sahu et al., 2021). In systems biology, energy costs are discussed in relation to specific processes like translation or signaling, but there is no general framework for classifying systems by energy role. Cell physiology addresses energy demands of activities such as active transport, though it lacks a taxonomy of systems grounded in energetic frameworks (Liang et al., 2025). Traditional cellular function classifications like Gene Ontology categorize genes and proteins based on their chemical function, biological role or cellular location (Chen et al., 2017; The Gene Ontology Consortium, 2019). While invaluable for annotation, these categories are not designed to capture dynamic interdependencies between functional systems or account for energy constraints. Synthetic biology platforms focus on engineering minimal pathways for energy production or consumption, but often without a general framework to classify entire systems based on energetic requirements. In contrast, our model bridges a classification framework with simulation tools, treating energy not just as an input or constraint but as a basis for defining system identity.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The values assigned to energy thresholds, coupling coefficients and delay parameters were based on representative estimates rather than empirical measurements from real cells, reducing the biological specificity of the simulations. We assumed that each module has a fixed energy requirement, yet in living models thresholds can be plastic and regulated through feedback and context. Our model handles inter-module energy transfer using average coupling values without accounting for spatial localization or real-time biochemical control, which limits its accuracy under conditions where spatial dynamics are critical. Still, our discrete-time simulation approach does not model continuous biochemical flux, stochastic variations, noise and feedback mechanisms that can significantly alter outcomes, particularly under low-energy conditions. Additionally, our model treats module transitions as binary, active or inactive, whereas biological systems often operate in graded states. This simplification limits the granularity of functional transitions that our model can capture. Finally, our framework is top-down and abstracted from molecular detail, which can make it difficult to directly link simulation outcomes to specific gene products or experimental interventions.

Our model suggests various avenues for future development and empirical testing, since it connects cell structure and function to thermodynamic principles. It is particularly suitable for research in bioenergetics, metabolism, aging research and synthetic biology modeling. One immediate application involves refining the model with transcriptomic and metabolomic data that capture cellular energy status and functional activity under stress conditions, enabling more accurate parameterization and system-specific calibration. Experimental tracking of cellular modules during controlled energy depletion and refeeding cycles could test whether observed reactivation sequences align with our predicted recovery order. In synthetic biology, our framework could help in designing minimal viable modules with defined energy roles and controlled prioritization. Our approach can also inform the development of modular control circuits that dynamically allocate energy between modules. Future research could extend our model to include spatial structure or simulate intercellular energy cooperation, particularly in tissues or microbial consortia. More refined simulations could replace binary activation with sigmoid or probabilistic response curves that reflect more realistic regulatory behavior. Future directions might also include developing a library of organism-specific parameter sets, creating tools for integration with molecular databases and expanding simulation capabilities to include adaptive thresholds. These developments would improve the model’s ability to make accurate predictions in diverse biological contexts and experimental setups. Another possible line of inquiry involves applying this classification to specific disease models such as energy imbalance in ischemia or metabolic stress in cancer cells. The modular design lends itself to flexibility in expansion, offering a stable yet open-ended framework for testing hypotheses related to energy flow, module prioritization and functional resilience under stress conditions.

In conclusion, we addressed the question of how energy-centered classification and dynamic simulation can enhance our understanding of modular cellular function. Our framework models cellular modules based on their energetic role and interaction under variable energy constraints. Our simulations quantified resilience, failure order and recovery patterns under distinct stress conditions and prioritization strategies. The results demonstrate the potential of this approach to generate functionally meaningful insights beyond static categorizations, offering a computational platform for analyzing module interdependence and energy allocation in a way that is scalable, modular and mathematically tractable.

Author Contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials.

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

References

- Anand, S.; Mukherjee, K.; Padmanabhan, P. "An Insight to Flux-Balance Analysis for Biochemical Networks. "Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews 36(no. 1 (April 2020)), 32–55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avcı, B.; Brandt, J.; Nachmias, D.; Elia, N.; Albertsen, M.; Ettema, T. J. G.; Schramm, A.; Kjeldsen, K. U. "Spatial Separation of Ribosomes and DNA in Asgard Archaeal Cells. "ISME Journal 16(no. 2 (February 2022)), 606–610. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordenstein; Seth, R. and The Holobiont Biology Network The Disciplinary Matrix of Holobiont Biology: Uniting Life’s Seen and Unseen Realms Guides a Conceptual Advance in Research. Science 2024, 386(6723), 731–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y. H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Cai, Y. D. "Prediction and Analysis of Essential Genes Using the Enrichments of Gene Ontology and KEGG Pathways. "PLoS ONE 12(no. 9 (September 5, 2017)), e0184129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, Brian N.; Smith, David W. On Strain and Stress in Living Cells. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2014, 71, 239–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuermann, Marc, Huaiyu; Mi; Gaudet, Pascale; Muruganujan, Anushya; Lewis, Suzanna E.; Ebert, Dustin; Mushayahama, Tremayne; Consortium, Gene Ontology; Thomas, Paul D. A Compendium of Human Gene Functions Derived from Evolutionary Modelling. Nature 2025, 640, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, K.; Nicoli, F.; Shehimy, S. A.; Penocchio, E.; Di Noja, S.; Li, Y.; Bonfio, C.; Borsley, S.; Ragazzon, G. "Catalysis-Driven Active Transport Across a Liquid Membrane; "Angewandte Chemie International Edition; Volume 64, no. 15 (April 7, 2025), p. e202421234. [CrossRef]

- Lopaschuk, G. D.; Karwi, Q. G.; Tian, R.; Wende, A. R.; Abel, E. D. "Cardiac Energy Metabolism in Heart Failure. "Circulation Research 128(no. 10 (May 14, 2021)), 1487–1513. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, Stuart M., Cole; Mathis; Carrick, Emma; Keenan, Graham; Cooper, Geoffrey J. T.; Graham, Heather; Craven, Matthew; Gromski, Piotr S.; Moore, Douglas G.; Walker, Sara I.; Cronin, Leroy. Identifying Molecules as Biosignatures with Assembly Theory and Mass Spectrometry. Nature Communications 2021, 12(Article 3033). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath; Sunil. "Thermodynamic Analysis of Energy Coupling by Determination of the Onsager Phenomenological Coefficients for a 3×3 System of Coupled Chemical Reactions and Transport in ATP Synthesis and Its Mechanistic Implications. "BioSystems 240(June 2024), 105228. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Yajuan, Yuzhong; Song; Mao, Jing. "Quantitative Analysis of the Coupling Coefficients between Energy Flow, Value Flow, and Material Flow in a Chinese Lead-Acid Battery System. "Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25(no. 34 (2018)), 34448–34459. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokopenko; Mikhail, Paul C. W.; Davies; Harré, Michael; Heisler, Marcus; Kuncic, Zdenka; Lewis, Geraint F.; Livson, Ori; Lizier, Joseph T.; Rosas, Fernando E. “Biological Arrow of Time: Emergence of Tangled Information Hierarchies and Self-Modelling Dynamics.” arXiv. 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.12029.

- Rak, M.; McStay, G. P.; Fujikawa, M.; Yoshida, M.; Manfredi, G.; Tzagoloff, A. "Turnover of ATP Synthase Subunits in F1-Depleted HeLa and Yeast Cells. "FEBS Letters 585(no. 16 (August 19, 2011)), 2582–2586. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigoulet, M.; Bouchez, C. L.; Paumard, P.; Ransac, S.; Cuvellier, S.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Mazat, J.-P.; Devin, A. "Cell Energy Metabolism: An Update. "Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 1861(no. 11 (November 1, 2020)), 148276. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu; Woo, Keun; Fung, Tak Shun; Baker, Daphne C.; Saoi, Michelle; Park, Jinsung; Febres-Aldana, Christopher A.; Aly, Rania G.; Cui, Ruobing; Sharma, Anurag; Fu, Yi; Jones, Olivia L.; Cai, Xin; Pasolli, H. Amalia; Cross, Justin R.; Rudin, Charles M.; Thompson, Craig B. Cellular ATP Demand Creates Metabolically Distinct Subpopulations of Mitochondria. Nature 2024, 635, 746–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, A.; Blätke, M. A.; Szymański, J. J.; Töpfer, N. "Advances in Flux Balance Analysis by Integrating Machine Learning and Mechanism-Based Models. "Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 19 (August 5(2021), 4626–4640. [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, Leah V.; Hu, Mengzhou; Qian, Gege; Moon, Kyung-Mee; Pal, Abantika; Soni, Neelesh; Latham, Andrew P.; Pontano Vaites, Laura; Tsai, Dorothy; Mattson, Nicole M.; Licon, Katherine; Bachelder, Robin; Cesnik, Anthony; Gaur, Ishan; Le, Trang; Leineweber, William; Palar, Aji; Pulido, Ernst; Qin, Yue; Zhao, Xiaoyu; et al. Multimodal Cell Maps as a Foundation for Structural and Functional Genomics. Nature 2025, 642, 222–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, Cameron A., Kelsey H.; Fisher-Wellman; Neufer, P. Darrell. From OCR and ECAR to Energy: Perspectives on the Design and Interpretation of Bioenergetics Studies. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2021, 297(4), 101140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, Júnia; Jamil, Tahira; Sengupta, Pratyay; Karthick, Shobhan; Sivabalan, Muthamilselvi; Rawat, Anamika; Patel, Niketan; Krishnamurthi, Srinivasan; Alam, Intikhab; Singh, Nitin K.; Raman, Karthik; Soares Rosado, Alexandre; Venkateswaran, Kasthuri. Genomic Insights into Novel Extremotolerant Bacteria Isolated from the NASA Phoenix Mission Spacecraft Assembly Cleanrooms. Microbiome 2025, 13(Article 117). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streit, Julian O.; Bukvin, Ivana V.; Chan, Sammy H. S.; Bashir, Shahzad; Woodburn, Lauren F.; Włodarski, T.; Figueiredo, Angelo Miguel; Jurkeviciute, Gabija; Sidhu, Haneesh K.; Hornby, Charity R.; Waudby, Christopher A.; Cabrita, Lisa D.; Cassaignau, Anaïs M. E.; Christodoulou, John. The Ribosome Lowers the Entropic Penalty of Protein Folding. Nature 2024, 633, 232–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. "The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 Years and Still GOing Strong. "Nucleic Acids Research 47(no. D1 (January 8, 2019)), D330–D338. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).