Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Farms and Animals

2.2. Data for Analysis

- age of the first calving;

- birth rate;

- calving interval;

- service period;

- number of inseminations per gestation.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Review

3. Results

3.1. Age of the First Calving

3.1. The Interval Between Successive Parturitions

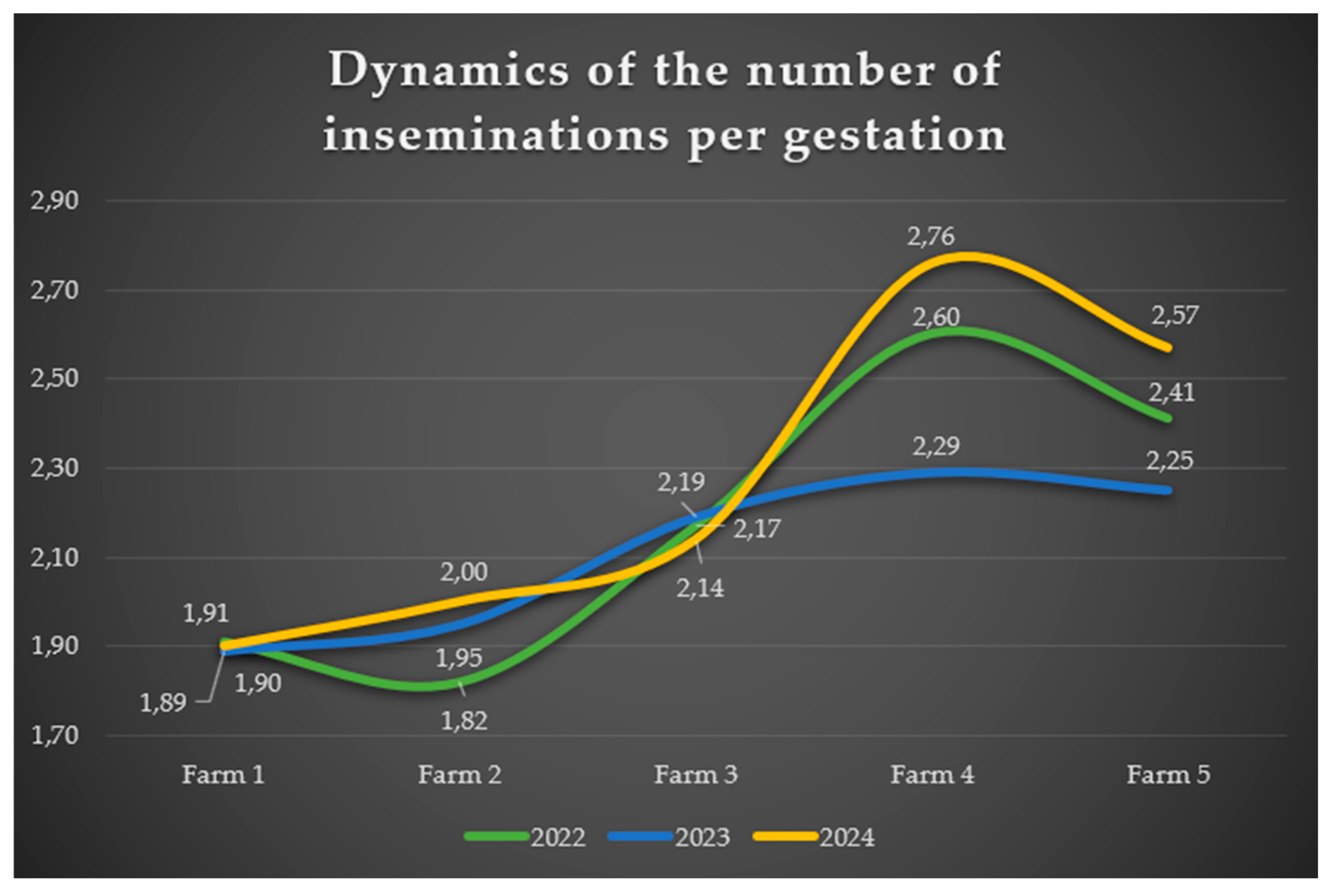

3.3. Number of Inseminations per Gestation

3.4. Efficiency of Using Cows for Reproduction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Dijk, M., Morley, T., Rau, M.L. et al. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050. Nat Food 2021, Volume 2, pp. 494–501.

- Smith, J. , Sones K., Grace D., MacMillan S., Tarawali S., Herrero M. Beyond milk, meat, and eggs: Role of livestock in food and nutrition security, Animal Frontiers 2013, Volume 3, pp. 6–13.

- Nicklas, T. A. , O’Neil, C. E., Fulgoni, V. L. The role of dairy in meeting the recommendations for shortfall nutrients in the American diet. The Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2009, Volume 28, pp. 73-81.

- Čuboň, J. , Haščík, P., Kačániová, M. D. Evaluation of raw materials and foodstuffs of animal origin, Slovak Republic: Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, pp. 381.

- Keresteš, J. Milk in human nutrition. Bratislava, Slovak Republic: Cad Press, 2016, pp. 649.

- Mihai, B. , Posan P., Marginean G.E., Alexandru M., Vidu L. Study on the trends of milk production and dairy products at european and national level. Scientific Papers. Series D. Animal Science 2023 Vol. LXVI, pp. 309-316.

- Mirmiran, P. , Esmaillzadeh, A., & Azizi, F. Dairy consumption and body mass index: an inverse relationship. International Journal of Obesity 2005, Volume 29(1), pp. 115-121.

- Teegarden, D. The Influence of Dairy Product Consumption on BodyComposition. The Journal of nutrition 2005, Volume 135(12), pp. 2749-2752.

- Zemel, M.B. , Richards, J., Mathis, S., Milstead, A., Gebhardt, L., & Silva, E. Dairy augmentation of total and central fat loss in obese subjects. International journal of obesity 2005, Volume 29(4), pp. 391-397.

- Vergnaud, A.C. , Péneau, S., Chat-Yung, S., Kesse, E., Czernichow, S., Galan, P.,... & Bertrais, S. Dairy consumption and 6-y changes in body weight and waist circumference in middle-aged French adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2008, Volume 88(5), pp. 1248-1255.

- Pal, S. , Ellis, V., & Dhaliwal, S. Effects of whey protein isolate on body composition, lipids, insulin and glucose in overweight and obese individuals. British journal of nutrition 2010, Volume 104(5), pp. 716-723.

- Sousa, G.T. , Lira, F.S., Rosa, J.C., de Oliveira, E.P., Oyama, L.M., Santos, R.V., & Pimentel, G. D. Dietary whey protein lessens several risk factors for metabolic diseases: a review. Lipids in health and disease 2012, Volume 11, pp. 1-9.

- Rosell, M. , Håkansson, N. N., & Wolk, A. Association between dairy food consumption and weight change over 9 y in 19 352 perimenopausal women. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2006, Volume 84(6), pp. 1481-1488.

- Faghih, S. H. , Abadi, A. R., Hedayati, M., & Kimiagar, S. M. Comparison of the effects of cows' milk, fortified soy milk, and calcium supplement on weight and fat loss in premenopausal overweight and obese women. Nutrition, metabolism and cardiovascular diseases 2011, Volume 21(7), pp. 499-503.

- Josse, A.R. , Atkinson, S.A., Tarnopolsky, M.A., & Phillips, S.M. Increased consumption of dairy foods and protein during diet-and exercise-induced weight loss promotes fat mass loss and lean mass gain in overweight and obese premenopausal women. The Journal of nutrition 2011, Volume 141(9), pp. 1626-1634.

- Abargouei, A.S. , Janghorbani, M., Salehi-Marzijarani, M., & Esmaillzadeh, A. Effect of dairy consumption on weight and body composition in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. International journal of obesity 2012, Volume 36(12), pp. 1485-1493.

- Sanders, T. A. Role of dairy foods in weight management. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012, Volume 96(4), pp. 687-688.

- Liu, S. , Choi, H.K., Ford, E., Song, Y., Klevak, A., Buring, J. E., & Manson, J. E. A prospective study of dairy intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes care 2006, Volume 29(7), pp. 1579-1584.

- Shahar, D. R. , Abel, R., Elhayany, A., Vardi, H., & Fraser, D. Does dairy calcium intake enhance weight loss among overweight diabetic patients?. Diabetes care 2007, Volume 30(3), pp. 485-489.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/dairy-production-products/production/dairy-animals/en (accessed on 20.01.2025).

- Michigan State University. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/history_of_dairy_cow_breeds_holstein (accessed on 20.01.2025).

- Dairy Global. Available online: https://www.dairyglobal.net/dairy/milking/us-holstein-cow-sets-new-lifetime-production-record/ (accessed on 20.01.2025).

- Kőrösi, Z.J.; Holló, G.; Bene, S.; Bognár, L.; Szabó, F. Association of Production and Selected Dimensional Conformation Traits in Holstein Friesian Cows. Animals 2024, 14, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amma Z, Reiczigel J, Fébel H, Solti L. Relationship between Milk Yield and Reproductive Parameters on Three Hungarian Dairy Farms. Vet Sci. 2024, Volume 11(5):218. [CrossRef]

- Nenel R., L. , & Mcgilliard M. L. Interactions of high milk yield and reproductive performance in dairy cows. Journal of dairy science 1993, Volume 76(10), pp. 3257-3268.

- Lucy M., C. Reproductive loss in high-producing dairy cattle: where will it end? Journal of dairy science 2001, Volume 84(6), pp. 1277-1293.

- Butler W., R. Energy balance relationships with follicular development, ovulation and fertility in postpartum dairy cows. Livestock production science 2003, Volume 83(2-3), pp. 211-218.

- Ettema, J.F. , Santos J.E. Impact of age at calving on lactation, reproduction, health, and income in first-parity Holsteins on commercial farms. Journal of dairy science 2004, Volume 87(8), pp. 2730-42.

- Leblanc, S. Assessing the association of the level of milk production with reproductive performance in dairy cattle. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2010, Volume 56(S), pp. S1-S7.

- Abeni, F. , Calamari L., Stefanini L., & Pirlo G. Effects of daily gain in pre-and postpubertal replacement dairy heifers on body condition score, body size, metabolic profile, and future milk production. Journal of Dairy Science 2000, Volume 83(7), pp. 1468-1478.

- Daniels K., M. Dairy heifer mammary development. Annual Tri-State Dairy Nutrition Conference, Grand Wayne Center, Fort Wayne, Indiana, USA, 20-21 April, 2010 (pp. 69-76). Purdue University Press.

- Mourits M. C., M. , Huirne R. B. M., Dijkhuizen A. A., Kristensen A. R., & Galligan, D. T. Economic optimization of dairy heifer management decisions. Agricultural systems 1999, Volume 61(1), pp. 17-31.

- Gabler M., T. & Heinrichs A. J. Dietary protein to metabolizable energy ratios on feed efficiency and structural growth of prepubertal Holstein heifers. Journal of dairy science 2003, Volume 86(1), pp. 268-274.

- Shamay, A. , Werner D., Moallem U., Barash H. & Bruckental I. Effect of nursing management and skeletal size at weaning on puberty, skeletal growth rate, and milk production during first lactation of dairy heifers. Journal of Dairy Science 2005, Volume 88(4), pp. 1460-1469.

- Stevenson J., L. , Rodrigues J. A., Braga F. A., Bitente S., Dalton J. C., Santos J. E. P. & Chebel R. C. Effect of breeding protocols and reproductive tract score on reproductive performance of dairy heifers and economic outcome of breeding programs. Journal of dairy science 2008, Volume 91(9), pp. 3424-3438.

- Fricke, P. M. Twinning in dairy cattle. The professional animal scientist 2001, Volume 17(2), pp. 61-67.

- Del Río, N. S. , Stewart, S., Rapnicki, P., Chang, Y. M., & Fricke, P. M. An observational analysis of twin births, calf sex ratio, and calf mortality in Holstein dairy cattle. Journal of dairy science 2007, Volume 90(3), pp. 1255-1264.

- Eddy, R. G. , Davies, O., & David, C. An economic assessment of twin births in British dairy herds. In American Association of Bovine Practitioners Conference Proceedings 1992, pp. 326-331.

- Beerepoot, G. M. M. , Dykhuizen, A. A., Nielen, Y., & Schukken, Y. H. The economics of naturally occurring twinning in dairy cattle. Journal of dairy science 1992, 75(4), 1044–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Němečková, D. , Stádník, L., & Čítek, J. Associations between milk production level, calving interval length, lactation curve parameters and economic results in Holstein cows. Mljekarstvo: časopis za unaprjeđenje proizvodnje i prerade mlijeka 2015, Volume 65(4), pp. 243-250.

- Sørensen, T.J. , Østergaard, S. Economic consequences of postponed first insemination of cows in a dairy cattle herd. Livestock Production Science 2003, Volume 79 (2-3), pp. 145-153.

- Murray, B. Balancing act – Research shows we are sacrificing fertility for production traits. Ontario MinistryAgric. Food 2003, Publ. 81-093.

- Wall E., S. Brotherstone J. A., Woolliams G. Banos & Coffey M. P. Genetic evaluation of fertility using direct and correlated traits. Journal of Dairy Science 2003, Volume 86, pp. 4093–4102.

- González-Recio, O. , Pérez-Cabal M. A. & Alenda R. Economic value of female fertility and its relationship with profit in Spanish dairy cattle. Journal of dairy science, 2004, Volume 87(9), pp. 3053-3061.

- Nederlands Rundvee Syndicaat. Jaarstatistieken 2005. Cooperatie Rundveeverbetering Delta, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

- Mikolaychik, I. N. , Gorelik, O. V., Nenahov, V. V., Morozova, L. A., & Safronov, S. L. The relationship between the duration of the service period and the milk yield of the Holsteinized black-mottled breed. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021 (Vol. 677, No. 4, p. 042016). IOP Publishing.

- Mymrin, V. , & Loretts, O. Contemporary trends in the formation of economically-beneficial qualities in productive animals. In International Scientific and Practical Conference “Digital agriculture-development strategy” (ISPC 2019), pp. 511-514. Atlantis Press.

- Gridina, S. L. , Gridin, V. F., & Leshonok, O. I. Characterization of high-producing cows by their immunogenetic status. In International scientific and practical conference" Agro-SMART-Smart solutions for agriculture"(Agro-SMART 2018, pp. 253-256. Atlantis Press.

- Chechenikhina, O. S. , Loretts, O. G., Bykova, O. A., Shatskikh, E. V., Gridin, V. F., & Topuriya, L. Y. Productive qualities of cattle in dependence on genetic and paratypic factors. International Journal of Advanced Biotechnology and Research 2018, Volume 9(1), pp. 587-593.

- Tkachenko, I. V. , Gridin, V. F., & Gridina, S. L. Results of researches federal state scientific institution" Ural research institute for agri-culture" on identification of interrelation efficiency cows of the ural type with the immune status. In Hui Yi research leek, raw anger and rational use of natural Zi source of raw material servo, 2016, pp. 85-90.

- Gridina, S. L. , & Shatalina, O. S. Relationship of cattle blood groups and the service period duration. Russian agricultural sciences 2015, Volume 41(4), pp. 271-273.

- Granaci, V. , Focşa, V., Curuliuc, V., & Ciubatco, V. Relația dintre service-period, productivitatea de lapte și manifestarea funcției de reproducție la vaci. In Inovații în zootehnie și siguranța produselor animaliere–realizări și perspective 2021, pp. 175-184).

- Carvalho J., O. , Sartori R., Machado G. M., Mourão G. B. & Dode M. A. N. Quality assessment of bovine cryopreserved sperm after sexing by flow cytometry and their use in in vitro embryo production. Theriogenology 2010, Volume 74(9), pp. 1521-1530.

- Dejarnette J., M. , Leach M. A., Nebel R. L., Marshall C. E., Mccleary C. R. & Moreno J. F. Effects of sex-sorting and sperm dosage on conception rates of Holstein heifers: is comparable fertility of sex-sorted and conventional semen plausible? Journal of dairy science 2011, Volume 94(7), pp. 3477-3483.

- Thomas J., M. , Locke J. W. C., Bonacker R. C., Knickmeyer E. R., Wilson D. J., Vishwanath R.,... & Patterson D. J. Evaluation of SexedULTRA 4M™ sex-sorted semen in timed artificial insemination programs for mature beef cows. Theriogenology 2019, pp. 100-107.

- Washburn, S. P. , Silvia, W. J., Brown, C. H., McDaniel, B. T., & McAllister, A. J. Trends in reproductive performance in southeastern Holstein and Jersey DHI herds. Journal of Dairy Science 2002, Volume 85(1), pp. 244-251.

- De Vries, A. , & Risco, C. A. Trends and seasonality of reproductive performance in Florida and Georgia dairy herds from 1976 to 2002. Journal of Dairy Science 2005, Volume 88(9), pp. 3155-3165.

- Pryce, J. E. , & Harris, B. L. Genetic and economic evaluation of dairy cow body condition score in New Zealand. Interbull Bulletin 2004, Volume 32, pp. 82-82.

- Cuvliuc, A.E. Cercetări privind parametrii fenotipici și genotipici la populația activă a rasei Holstein din România. Doctoral thesis, University of Agronomic Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, Bucharest, 28.02.2022.

- Holstein Association USA. Available online: https://www.holsteinusa.com/holstein_breed/breedhistory.html (accessed on 10.02.2025).

| Farm studied | Age at the first calve (days) Year of reference |

p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||

| Farm A | N | 816 | 742 | 796 | |

| X ± SX | 757.36 ± 6.07 | 738.89 ± 2.91 | 738.31 ± 2.15 | 3.11*** | |

| S | 172.26 | 79.08 | 60.53 | ||

| CV(%) | 22.75 | 10.7 | 8.20 | ||

| Farm B | N | 684 | 738 | 809 | |

| X ± SX | 679.49 ± 2.33 | 677.01 ± 1.64 | 675.92 ± 1.57 | 1.27* | |

| S | 60.73 | 44.67 | 44.63 | ||

| CV(%) | 8.94 | 6.60 | 6.60 | ||

| Farm C | N | 454 | 618 | 641 | 3.38*** |

| X ± SX | 731.04 ± 2.68 | 726.71 ± 2.02 | 722.10 ± 1.81 | ||

| S | 42.72 | 45.32 | 43.83 | ||

| CV(%) | 5.84 | 6.24 | 6.07 | ||

| Farm D | N | 424 | 445 | 519 | 1.65** |

| X ± SX | 733.45 ± 5.31 | 710.7 ± 4.07 | 722.82 ± 3.96 | ||

| S | 107.08 | 84.46 | 86.39 | ||

| CV(%) | 5.31 | 11.88 | 11.95 | ||

| Farm E | N | 412 | 595 | 628 | |

| X ± SX | 671.10 ± 5.13 | 703.83 ± 4.23 | 718.04 ± 3.77 | 7.62*** | |

| S | 100.23 | 99.49 | 92.51 | ||

| CV(%) | 14.93 | 14.14 | 12.88 | ||

| Farm studied | Quantity of milk (kg)/305 lactation daysYear of reference | p-Value | |||

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||

| Farm A | N | 816 | 742 | 796 | |

| X ± SX | 13062.77 ± 10.85 | 14316.3 ± 22.23 | 14306.59 ± 12.7 | 1.21* | |

| S | 310 | 605.5 | 340.65 | ||

| CV(%) | 2.37 | 4.23 | 2.38 | ||

| Farm studied | Quantity of milk (kg)/305 lactation daysYear of reference | p-Value | |||

| Farm B | N | 684 | 738 | 809 | |

| X ± SX | 12783.19 ± 83.72 | 14684.72 ± 19.18 | 15514.01 ± 29.31 | 3.13*** | |

| S | 889.64 | 521.13 | 833.87 | ||

| CV(%) | 17.13 | 3.54 | 5.37 | ||

| Farm C | N | 454 | 618 | 641 | 2.28** |

| X ± SX | 12549.08 ± 44.95 | 12255.60 ± 33.78 | 9731.43 ± 30.72 | ||

| S | 957.86 | 840.47 | 777.9 | ||

| CV(%) | 7.64 | 6.85 | 7.9 | ||

| Farm D | N | 424 | 445 | 519 | 5.98*** |

| X ± SX | 9749.38 ± 20.88 | 10546.93 ± 39.79 | 11163.22 ± 26.97 | ||

| S | 430.71 | 839.35 | 597.4 | ||

| CV(%) | 4.41 | 7.95 | 5.35 | ||

| Farm E | N | 412 | 595 | 628 | |

| X ± SX | 10900.45 ± 21.561 | 11598.05 ± 68.43 | 12042.41 ± 84.37 | 13.11*** | |

| S | 437.81 | 1669.28 | 2114.42 | ||

| CV(%) | 4.02 | 14.39 | 17.55 | ||

| Farm | Value of phenotypic correlations | |

| 2022 | 2024 | |

| Farm A | 0 | 0.05 |

| Farm B | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Farm C | -0.06 | 0.03 |

| Farm D | 0.01 | 0.25 |

| Farm E | 0 | -0.06 |

| Farm studied | Calving intervalul (days)Year of reference | p-Value | |||

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||

| Farm A | N | 816 | 742 | 796 | |

| X ± SX | 392.22 ± 1.94 | 396.6 ± 2.54 | 400.1 ± 1.87 | 1.55* | |

| S | 45.97 | 53.88 | 44.62 | ||

| CV(%) | 11.72 | 13.59 | 11.15 | ||

| Farm B | N | 684 | 738 | 809 | |

| X ± SX | 389.80 ± 3.59 | 393.77 ± 3.97 | 395.85 ± 3.38 | ||

| S | 73.57 | 82.76 | 75.53 | 1.56* | |

| CV(%) | 18.87 | 21.02 | 19.08 | ||

| Farm C | N | 454 | 618 | 641 | |

| X ± SX | 404.93 ± 4.47 | 398.44 ± 4.14 | 404.74 ± 3.95 | ||

| S | 78.24 | 78.35 | 75.35 | 0.04 | |

| CV(%) | 19.32 | 19.66 | 18.62 | ||

| Farm D | N | 424 | 445 | 519 | |

| X ± SX | 393.62 ± 4.78 | 375.75 ± 3.85 | 403.10 ± 4.83 | ||

| S | 76.19 | 59.61 | 82.76 | 1.83** | |

| CV(%) | 19.36 | 15.87 | 20.53 | ||

| Farm E | N | 412 | 595 | 628 | |

| X ± SX | 400.61 ± 5.03 | 400.05 ± 4.83 | 401.16 ± 3.42 | ||

| S | 84.75 | 87.95 | 71.31 | 0.10 | |

| CV(%) | 21.15 | 21.99 | 17.78 | ||

| Efficiency indicators | Farm studied | ||||

| Farm A | Farm B | Farm C | Farm D | Farm E | |

| Number of cows culled | 544 | 458 | 430 | 198 | 283 |

| Average value of the interval from first to last gestation (years) | 3.45 | 3.09 | 3.17 | 3.18 | 3.74 |

| Average number of completed lactations | 4.19 | 3.88 | 3.84 | 3.98 | 4.38 |

| Efficiency of use in reproduction (%) | 92.43 | 93.15 | 89.69 | 93.64 | 90.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).