Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

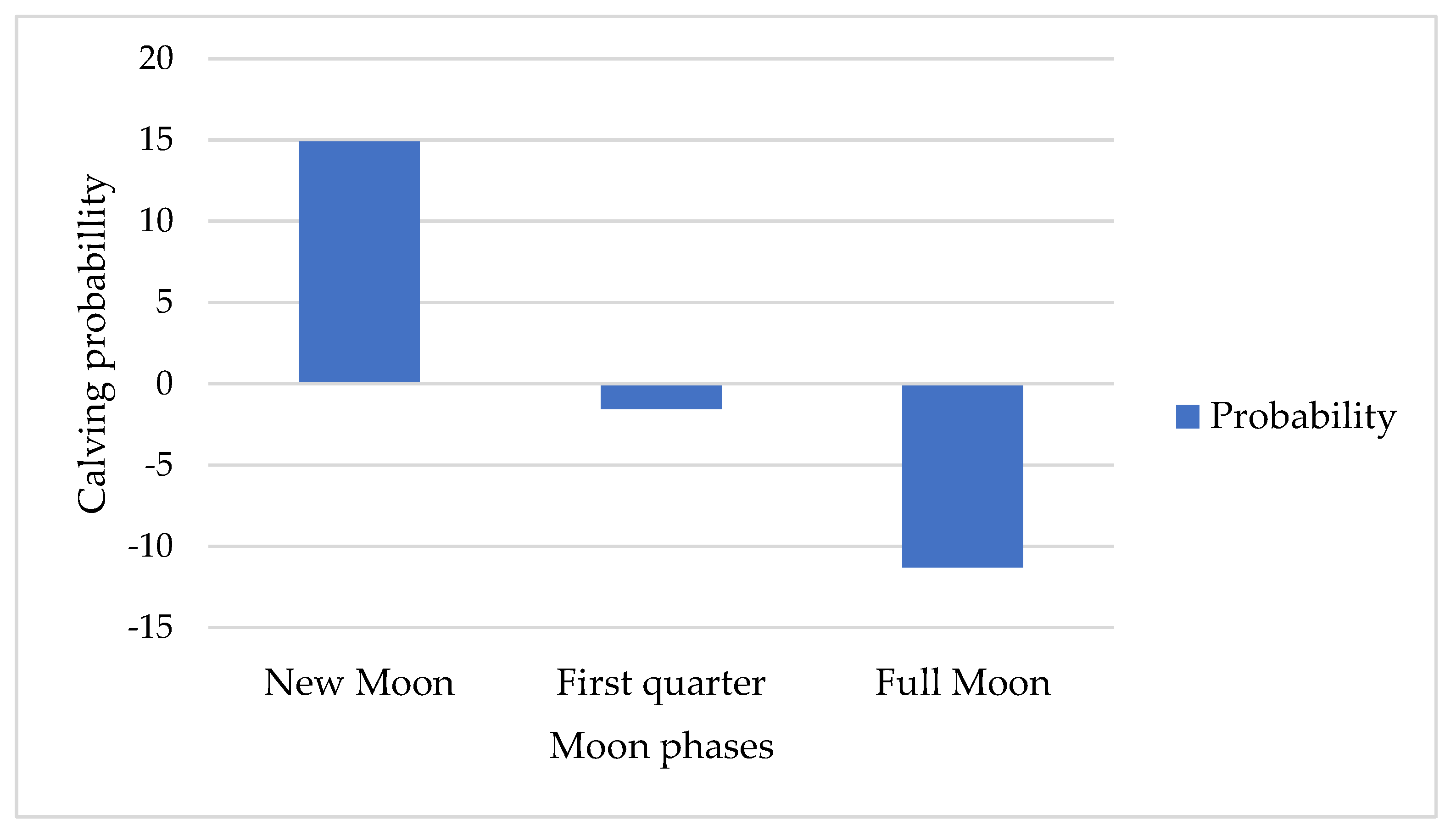

The Moon is at the centre of many popular beliefs including that the number of births increases during Full Moon days, followed by many breeders to anticipate calving periods. However, it has been rarely explored in dairy cattle farming. This retrospective study was conducted to evaluate the association of lunar cycles on calving distribution, with particular focus on a potential increase during full-moon nights. Data from 383,926 calvings of Montbéliard breed that occurred between March 2022, and January 2025, mostly in Franche-Comté (98.2%), France were analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed using the Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM). Results revealed significant association of the lunar cycle on calving distribution, it was observed a higher calving probability than the average (p < 0.001, +15%) during the New Moon, and a lower calving probability than the average during the First Quarter and Full Moon phases (p < 0.001 for both and -1.5% and -11%, respectively) in all groups, primiparous, multiparous, male and female. The observed patterns may have practical implications for veterinarians and breeders, particularly in ensuring adequate colostrum intake, thereby supporting improved management of parturition periods.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Characteristics

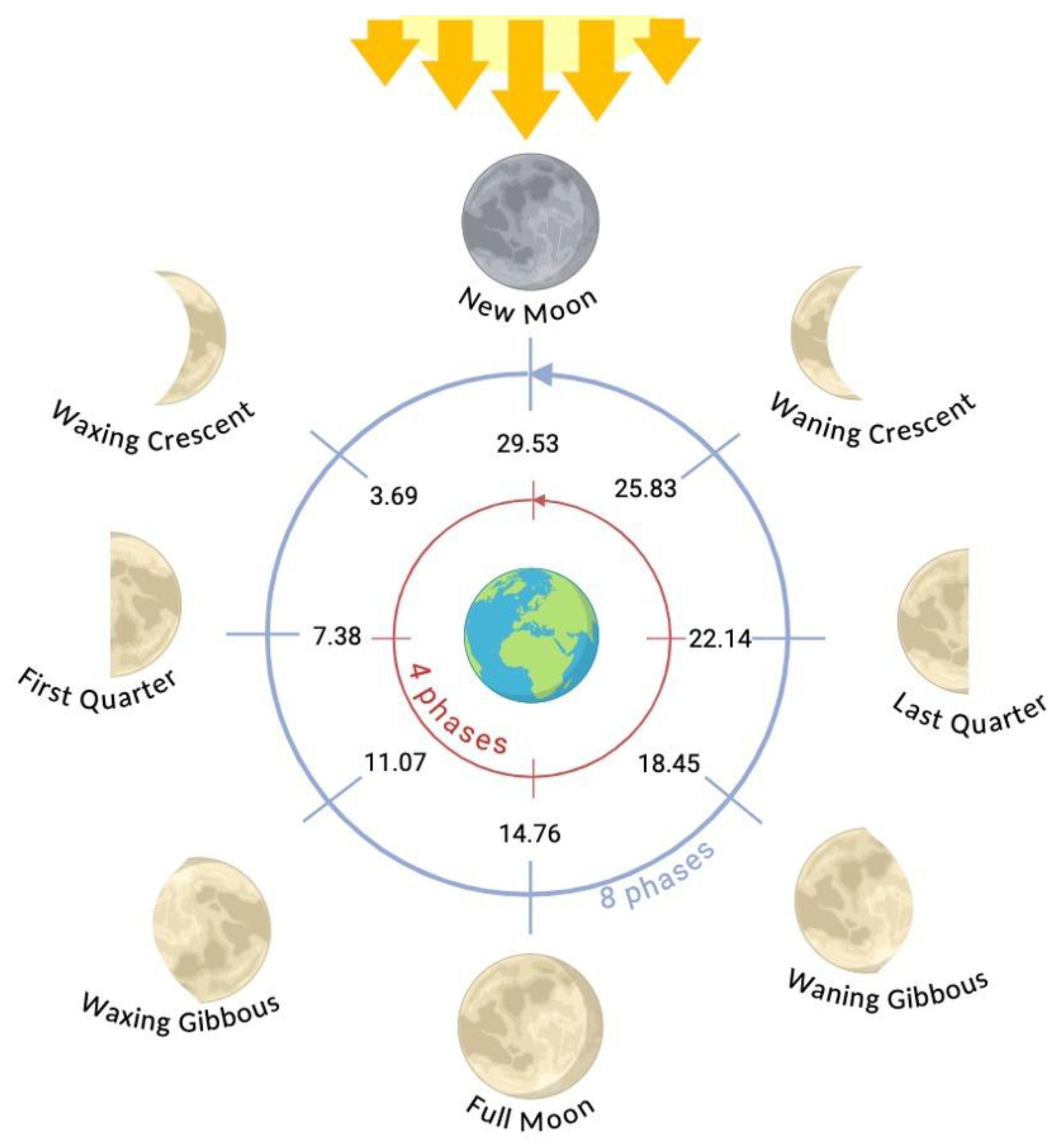

2.2. Characteristics of the Lunar Cycle

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

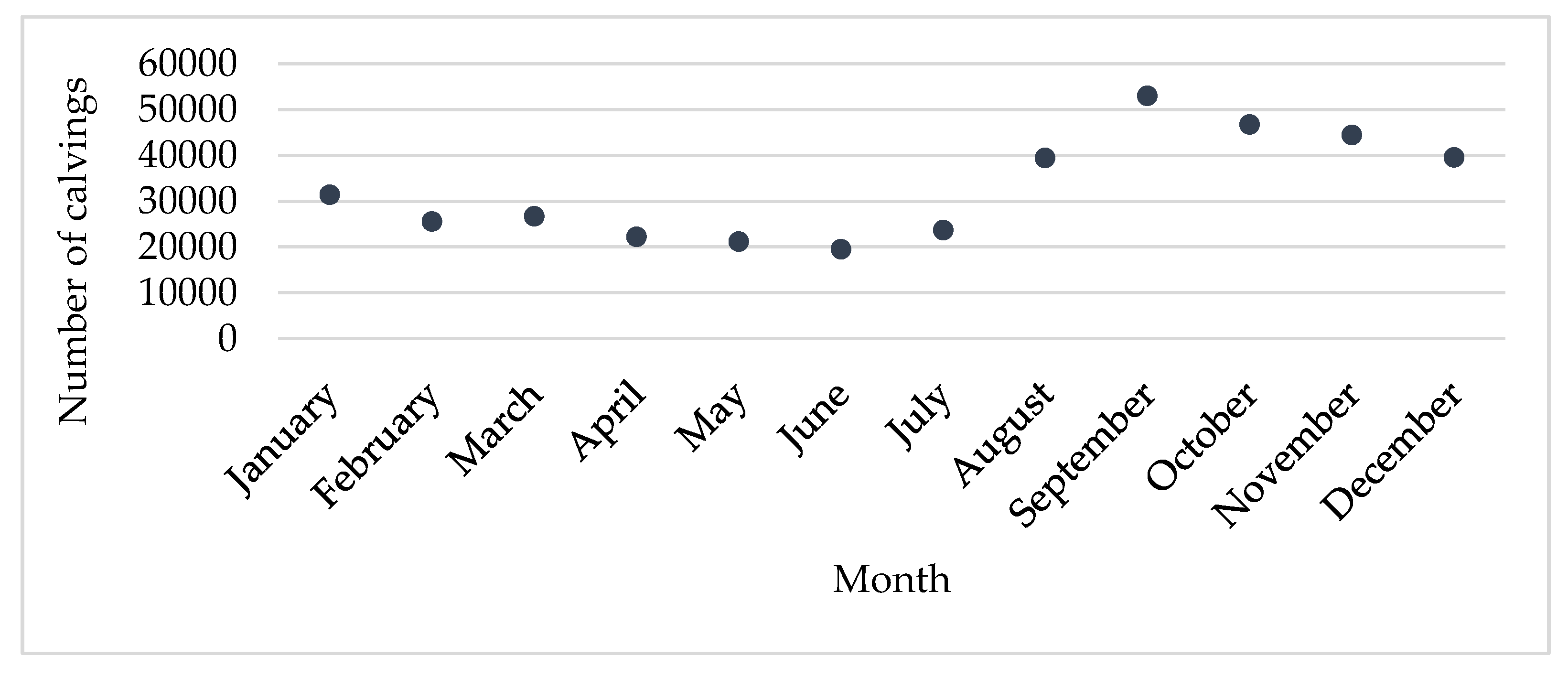

3.1. Monthly Distribution of Calving in Montbéliarde Cows

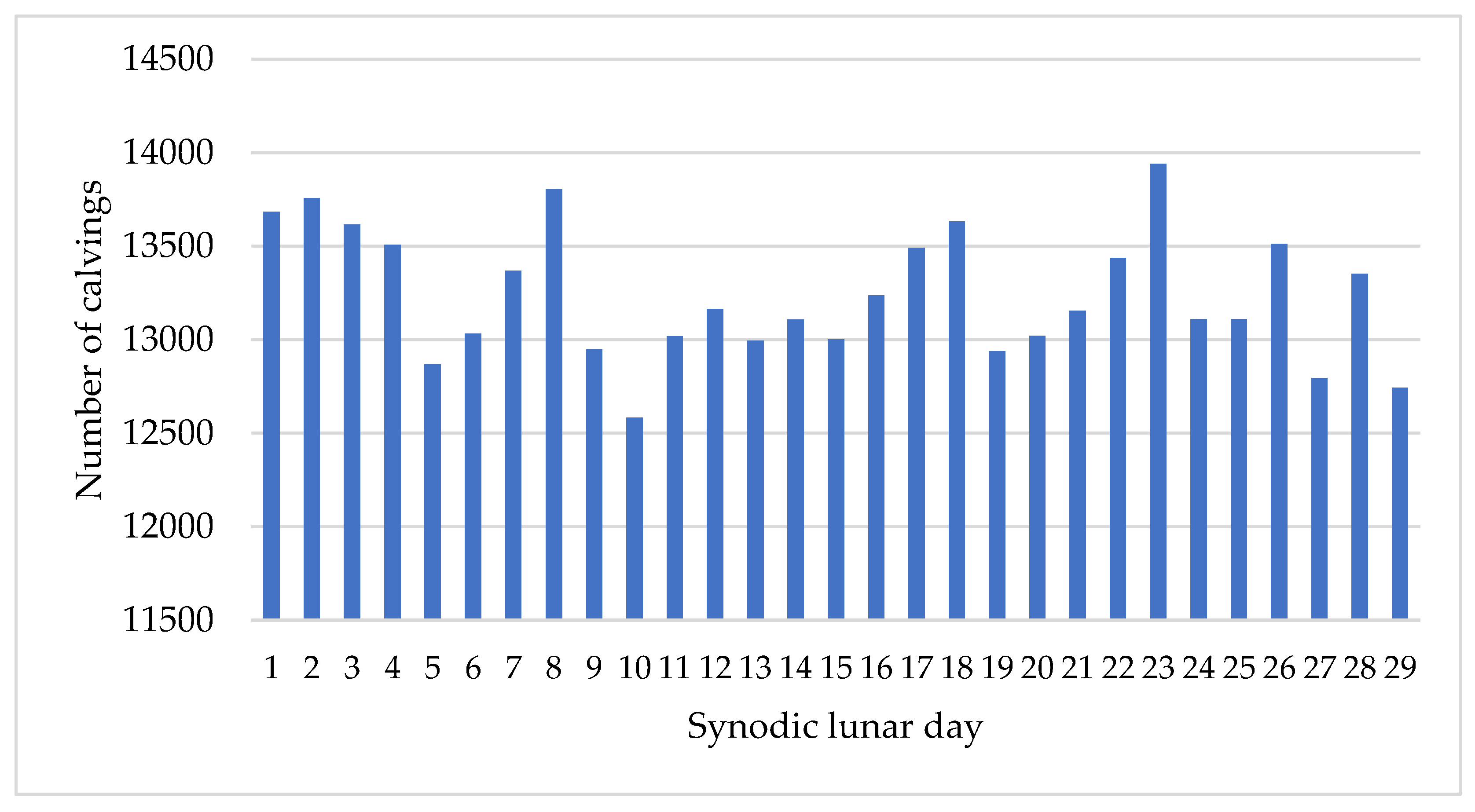

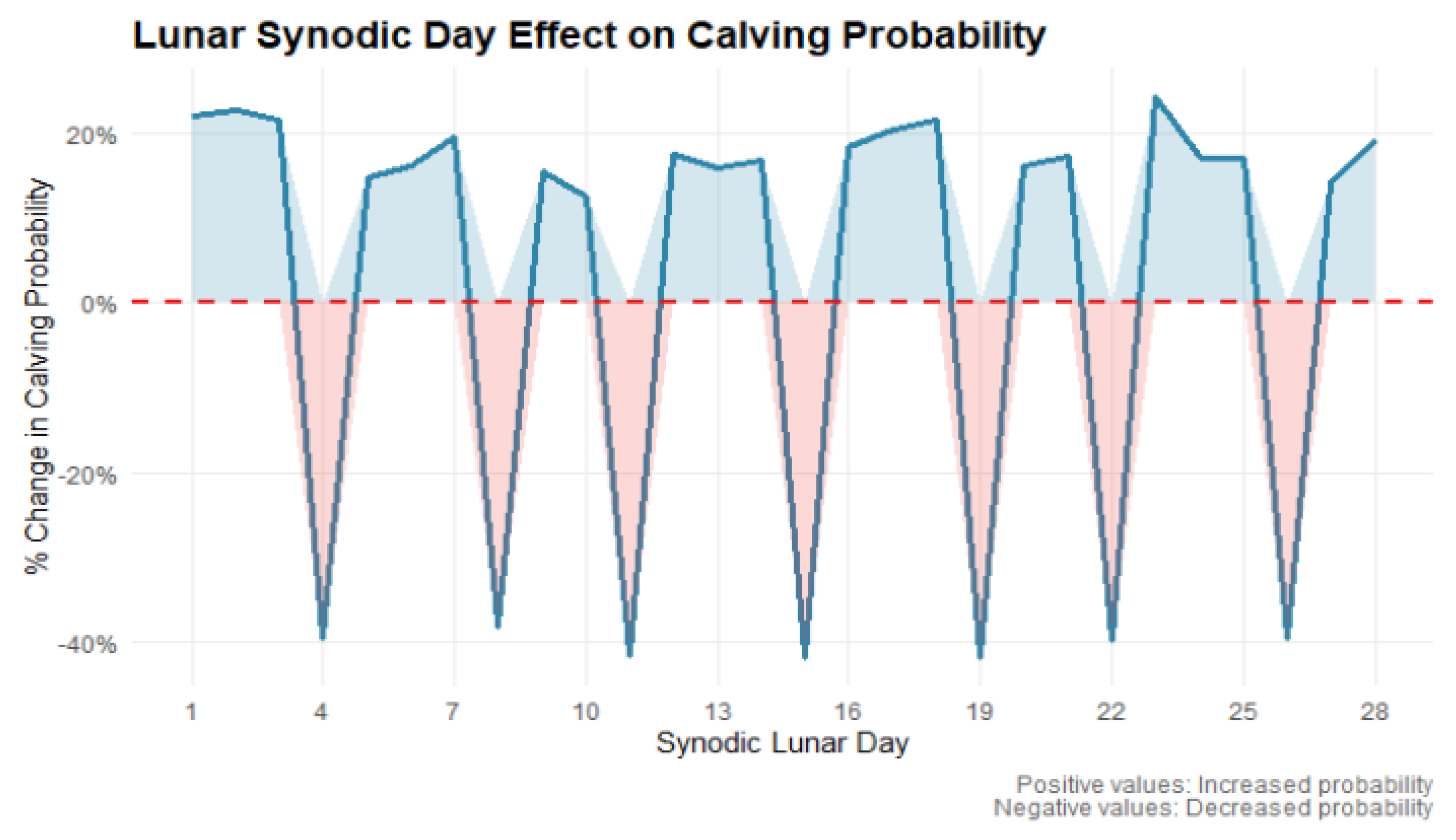

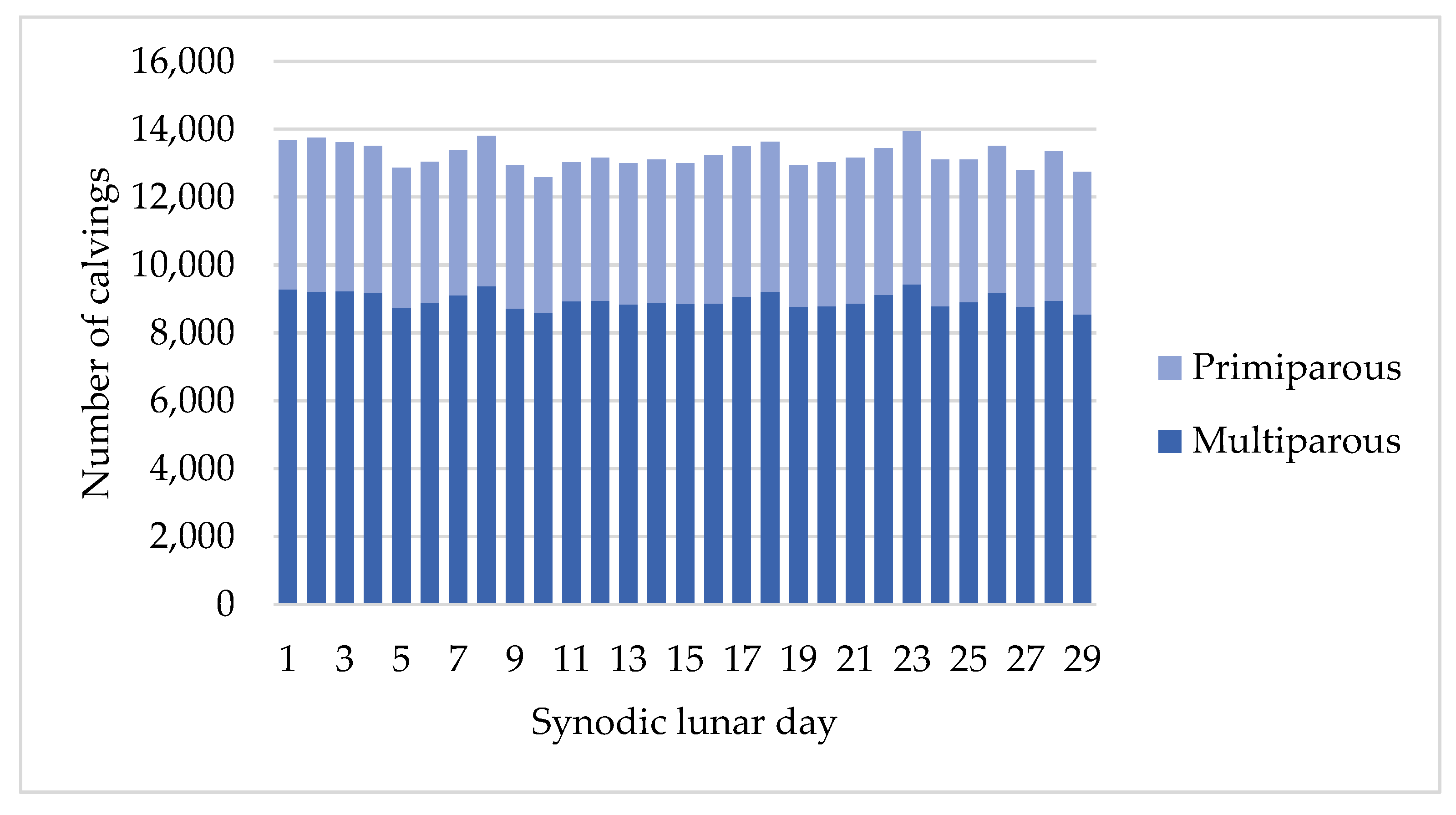

3.2. Analysis by Synodic Lunar Days

3.3. Analysis by Lunar Phases

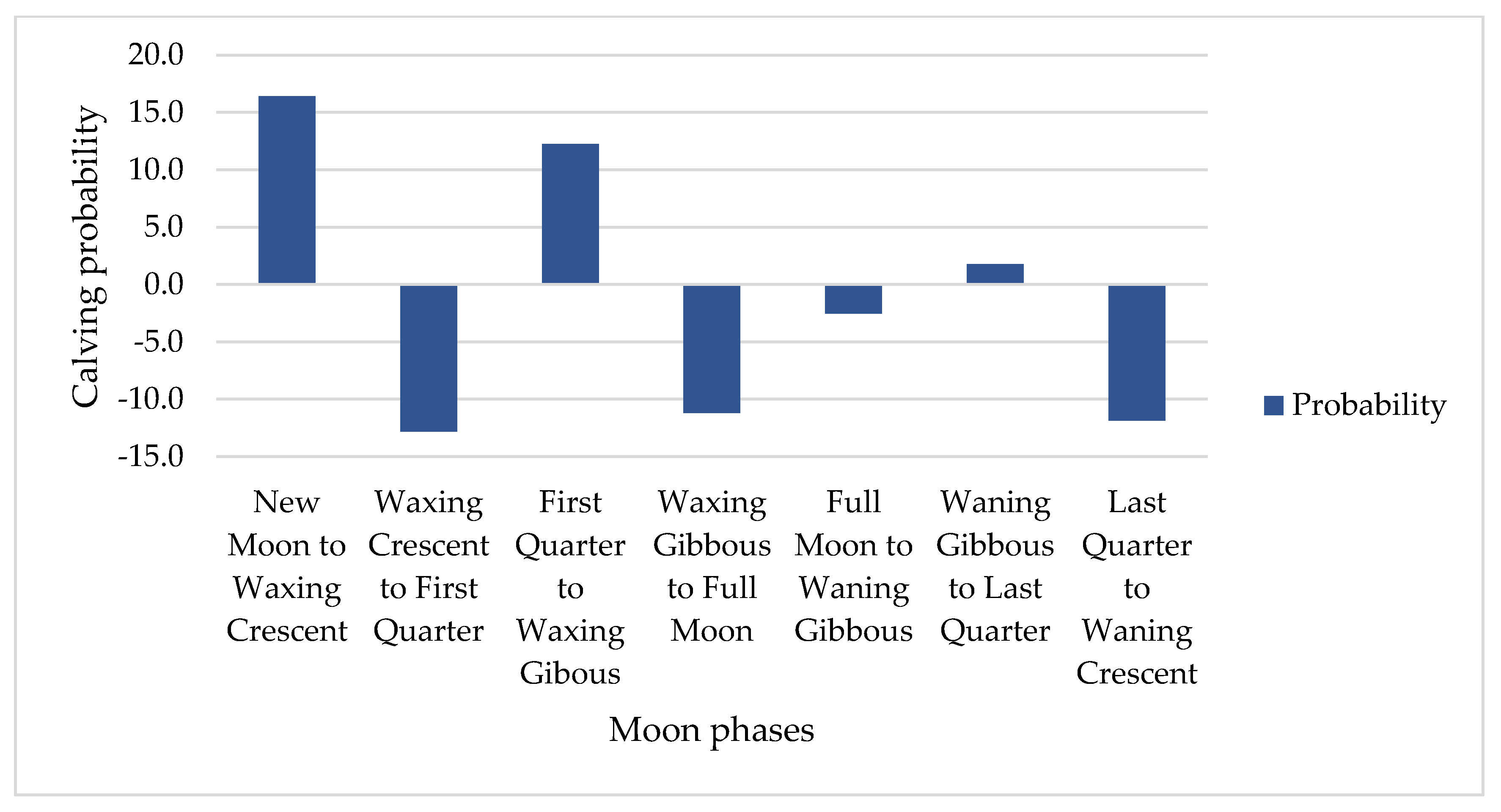

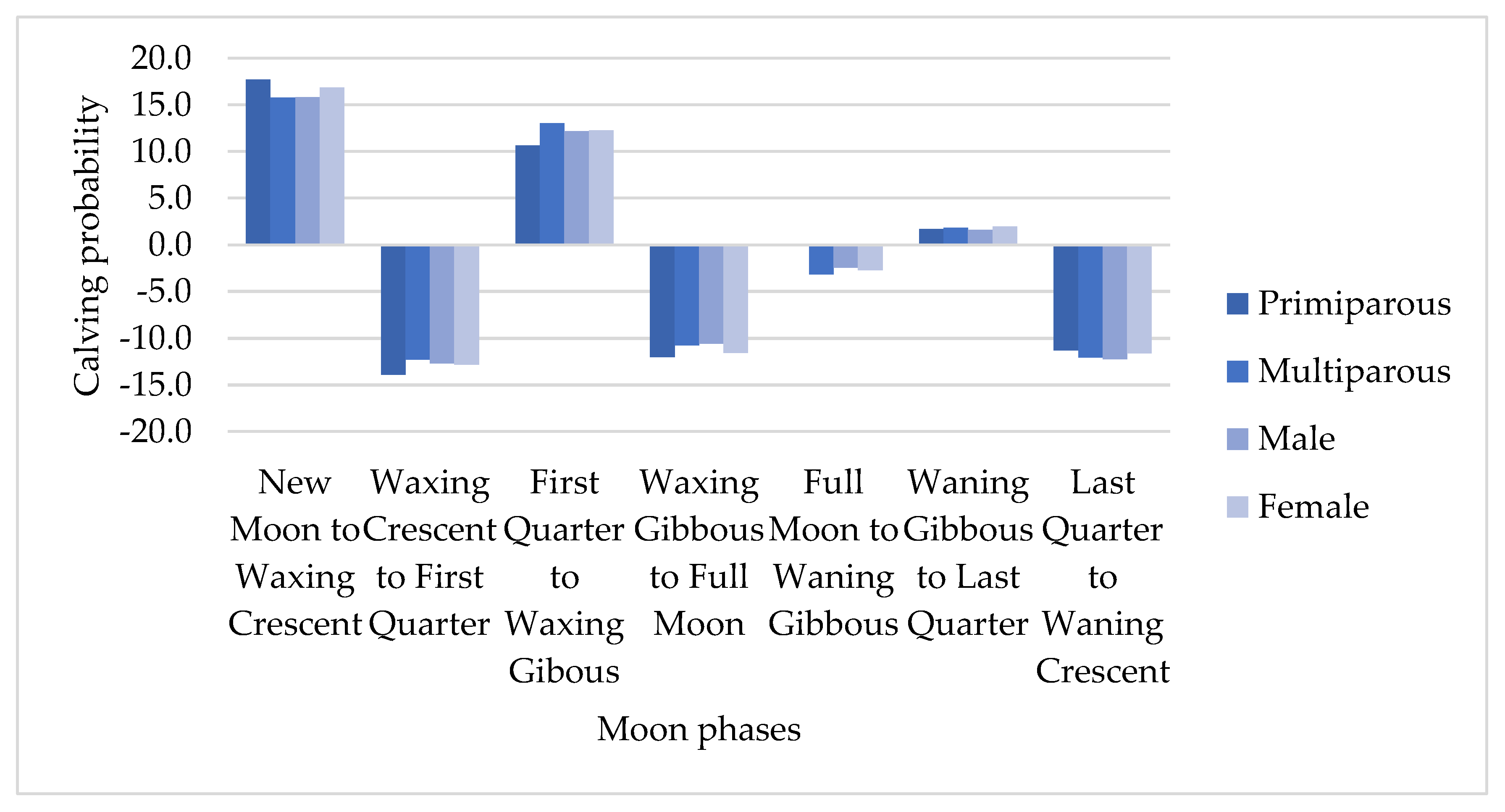

3.3.1. Synodic Waxing and Waning Phases

3.3.2. Distribution in Four Phases of the Synodic Revolution

3.3.3. Distribution in Eight Phases of the Synodic Revolution

3.3.4. Analysis by the Tropical Month

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EDE | Institute of Livestock |

| H0 | Null hypothesis |

| H1 | Alternative hypothesis |

| IRR | Incidence Rate Ratio |

| GLMM | Generalized Linear Mixed Method |

| Km | Kilometers |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| UTC | Coordinated Universal Time |

| % | % - Percentage |

References

- Yonezawa, T.; Uchida, M.; Tomioka, M.; Matsuki, N. Lunar Cycle Influences Spontaneous Delivery in Cows. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0161735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinedo, P.; Keller, K.; Schatte, M.; Velez, J.; Grandin, T. Association between the Lunar Cycle and Pregnancy at First Artificial Insemination of Holstein Cows. JDS Commun. 2025, 6, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre, A.A.; Palomares, R.A.; De Ondiz, A.D.; Soto, E.R.; Perea, M.S.; Hernández-Fonseca, H.J.; Perea, F.P. Lunar Cycle Influences Reproductive Performance of Crossbred Brahman Cows Under Tropical Conditions. J. Biol. Rhythms 2021, 36, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammann, T.; Hässig, M.; Rüegg, S.; Bleul, U. Effects of Meteorological Factors and the Lunar Cycle on Onset of Parturition in Cows. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 126, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, F.P.; Pulla, A.M.; Quito, K.P.; Soria, M.E.; Romero, A.; Hernández-Fonseca, H.; Palomares, R.A.; Ungerfeld, R.; Villamediana, P.; Mendez, M.S. Moon Cycle Influences Calving Frequency, Gestation Length and Calf Weight at Birth, but Not Offspring Sex Proportion in Tropical Crossbred Cattle. Chronobiol. Int. 2024, 41, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y.; Kitai, N.; Uematsu, M.; Kitahara, G.; Osawa, T. Daily Calving Frequency and Preterm Calving Is Not Associated with Lunar Cycle but Preterm Calving Is Associated with Weather Conditions in Japanese Black Cows. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0220255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojewodzic, D.; Gołębiewski, M.; Grodkowski, G. Methods of Observing the Signs of Approaching Calving in Cows—A Review. Animals 2025, 15, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, L.; Kézér, F.L.; Bodó, S.; Ruff, F.; Palme, R.; Szenci, O. Salivary Cortisol as a Non-Invasive Approach to Assess Stress in Dystocic Dairy Calves. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztowny, E.; Wawrzykowski, J.T.; Jamioł, M.A.; Kankofer, M. The Profile of Selected Protein Markers of Senescence in the Placentas of Cows During Early–Mid-Pregnancy and Parturition with and Without the Retention of Fetal Membranes: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenavai, S.; Preissing, S.; Hoffmann, B.; Dilly, M.; Pfarrer, C.; Özalp, G.R.; Caliskan, C.; Seyrek-Intas, K.; Schuler, G. Investigations into the Mechanisms Controlling Parturition in Cattle. REPRODUCTION 2012, 144, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Physiology, Cytobiology and Proteomics, West Pomeranian University of Technology Szczecin, Janickiego 29, 71-270 Szczecin, Poland; Kurpińska, A. ; Skrzypczak, W.; Department of Physiology, Cytobiology and Proteomics, West Pomeranian University of Technology Szczecin, Janickiego 29, 71-270 Szczecin, Poland Hormonal Changes in Dairy Cows during Periparturient Period. Acta Sci. Pol. Zootech. 2020, 18, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, J.; Stilwell, G. Calving Management and Newborn Calf Care: An Interactive Textbook for Cattle Medicine and Obstetrics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-68167-8. [Google Scholar]

- Holtgrew-Bohling, Kristin Large Animal Clinical Procedures for Veterinary Technicians: Husbandry, Clinical Procedures, Surgical Procedures, and Common Diseases.; 5th Edition.; Elsevier, 2023; ISBN 978-0-323-88200-2.

- Jackson, Peter G.G., Handbook of Veterinary Obstetrics.; 2nd ed.; Saunders Ldt, 2004; ISBN 978-0-7020-2740-6.

- Guo, L.; Li, M.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Lu, W. Two Melatonin Treatments Improve the Conception Rate after Fixed-time Artificial Insemination in Beef Heifers Following Synchronisation of Oestrous Cycles Using the CoSynch -56 Protocol. Aust. Vet. J. 2021, 99, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Ispierto, I.; Abdelfatah, A.; López-Gatius, F. Melatonin Treatment at Dry-off Improves Reproductive Performance Postpartum in High-producing Dairy Cows under Heat Stress Conditions. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2013, 48, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasek, R.; Rezac, P.; Havlicek, Z. Environmental and Animal Factors Associated with Gestation Length in Holstein Cows and Heifers in Two Herds in the Czech Republic. Theriogenology 2017, 87, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zain The Montbéliarde Cattle: A Top Dairy Cattle Breed Known for High Milk Production. Available online: https://cattledaily.com/montbeliarde-cattle/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Logeais, Caroline; Loones, Fabrice Insee, Bourgogne- Franche- Comté Première Région Rurale de France. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/5360632.

- Lourenço, J. C. S. Impacto Do Parto Distócico No Desempenho Produtivo e Reprodutivo de Bovinos Leiteiros, Universidade Estadual de Maringá: Paraná, Brazil, 2019.

- Mee, J.F. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Dystocia in Dairy Cattle: A Review. Vet. J. 2008, 176, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaousioti, A.; Basioura, A.; Praxitelous, A.; Tsousis, G. Dystocia in Dairy Cows and Heifers: A Review with a Focus on Future Perspectives. Dairy 2024, 5, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboisson, D.; Trillat, P.; Dervillé, M.; Cahuzac, C.; Maigné, E. Defining Health Standards through Economic Optimisation: The Example of Colostrum Management in Beef and Dairy Production. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0196377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godden, S. Colostrum Management for Dairy Calves. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2008, 24, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.J.; Heinrichs, A.J. Invited Review: The Importance of Colostrum in the Newborn Dairy Calf. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 2733–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Dictionary of Astronomy; Ridpath, I., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2018; Vol. 1.

- Taillet, R.; Villain, L.; Febvre, P. Dictionnaire de Physique; 5th ed.; De Boeck Supérieur, 2023; ISBN 978-2-8073-4822-6.

- Murdin, P. Encyclopedia of Astronomy & Astrophysics, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2001; ISBN 978-1-003-22043-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kronfeld-Schor, N.; Dominoni, D.; De La Iglesia, H.; Levy, O.; Herzog, E.D.; Dayan, T.; Helfrich-Forster, C. Chronobiology by Moonlight. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20123088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, M.V.; Kumar, S. Moon and Health: Myth or Reality? Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Science NASA Science, Moon Phases Available online:. Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/moon/moon-phases (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Gros, Clement; Gros, Michel Calendrier Lunaire 2025; 47 éd.; CALENDRIER LUNAIRE, 2024; ISBN 978-2-9559359-6-5.

- Andreatta, G.; Tessmar-Raible, K. The Still Dark Side of the Moon: Molecular Mechanisms of Lunar-Controlled Rhythms and Clocks. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 3525–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Microsoft Corporation Microsoft Excel 2021.

- French Republique Arrêté Du 6 Août 2013 Relatif à l’identification Des Animaux de l’espèce Bovine; 2013.

- NASA Moon Phase and Libration Available online: https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/gallery/moonphase.

- Lune-pratique.fr Calendrier Lunaire. Available online: https://www.lune-pratique.fr (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation Microsoft Power BI Desktop 2025.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2021.

- Bolker, B.M.; Brooks, M.E.; Clark, C.J.; Geange, S.W.; Poulsen, J.R.; Stevens, M.H.H.; White, J.-S.S. Generalized Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide for Ecology and Evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staboulidou, I.; Soergel, P.; Vaske, B.; Hillemanns, P. The Influence of Lunar Cycle on Frequency of Birth, Birth Complications, Neonatal Outcome and the Gender: A Retrospective Analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2008, 87, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharati, S.; Sarkar, M.; Haldar, P.; Jana, S.; Mandal, S. The Effect of the Lunar Cycle on Frequency of Births: A Retrospective Observational Study in Indian Population. Indian J. Public Health 2012, 56, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, O.; Kuehn, A. Lunar Cycle and the Number of Births: A Spectral Analysis of 4,071,669 Births from South-Western Germany. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2008, 87, 1378–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Gracia, F.J. The Influence of the Lunar Cycle on Spontaneous Deliveries in Historical Rural Environments. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 236, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Luengo, F.; Salamanca-Zarzuela, B.; Urueña, S.M.; García, C.E.; Carboner, S.C. External Influences on Birth Deliveries: Lunar Gravitational and Meteorological Effects. An. Pediatría Engl. Ed. 2020, 93, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londero, A.P.; Bertozzi, S.; Messina, G.; Xholli, A.; Michelerio, V.; Mariuzzi, L.; Prefumo, F.; Cagnacci, A. Exploring the Mystical Relationship between the Moon, Sun, and Birth Rate. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudziunaite, S.; Moshammer, H. Temporal Patterns of Weekly Births and Conceptions Predicted by Meteorology, Seasonal Variation, and Lunar Phases. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2022, 134, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, T.S. The effect of lunar cycle on the frequency of birth in Al-Elwiya maternity hospital, Baghdad, 2017. 2018, pp. 78–82.

- Charpentier, A.; Causeur, D. Large-Scale Significance Testing of the Full Moon Effect on Deliveries. 2010.

- Chastant-Maillard, S.; Saint-Dizier, M. Le vêlage: pourquoi, quand, comment?. 2009, pp. 37–42.

- Rørvang, M.V.; Nielsen, B.L.; Herskin, M.S.; Jensen, M.B. Prepartum Maternal Behavior of Domesticated Cattle: A Comparison with Managed, Feral, and Wild Ungulates. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soriano, F.; Ruiz-Torner, A.; Armañanzas, E.; Valverde-Navarro, A.A. Influence of Light/Dark, Seasonal and Lunar Cycles on Serum Melatonin Levels and Synaptic Bodies Number of the Pineal Gland of the Rat. Histol. Histopathol. 2002; 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P-value | Positive probability (day) | IRR1 | Percentual effect | Negative probability (day) |

IRR1 |

Percentual effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primiparous | < 0.001 | 1 - 3 | 1.21 – 1.25 | 21% - 25% 14% - 18% 11% - 17% 15% - 16% |

4 8 11 15 |

0.60 | 40% |

| 5 - 7 | 1.14 – 1.18 | 0.62 | 38% | ||||

| 9 - 10 | 1.11 – 1.17 | 0.57 | 43% | ||||

| 12 - 14 | 1.15 – 1.16 | 0.58 | 42% | ||||

| 16 - 18 | 1.21 – 1.23 | 21% - 23% | 19 | 0.58 | 42% | ||

| 20 - 21 | 1.17 – 1.18 | 17% - 18% | 22 | 0.60 | 40% | ||

| 23 - 25 | 1.16 – 1.25 | 16% - 25% | 26 | 0.60 | 40% | ||

| 27 - 28 | 1.12 – 1.22 | 11% - 22% | - | - | - | ||

| Multiparous | < 0.001 | 1 - 3 | 1.21 – 1.22 | 21% - 22% 15% - 20% |

4 8 |

0.61 | 39% |

| 5 - 7 | 1.15 – 1.20 | 0.62 | 38% | ||||

| 9 - 10 | 1.11 – 1.17 | 11% - 17% | 11 | 0.57 | 43% | ||

| 12 - 14 | 1.15 – 1.16 | 15% - 16% | 15 | 0.58 | 42% | ||

| 16 - 18 | 1.21 – 1.26 | 21% - 23% | 19 | 0.58 | 42% | ||

| 20 - 21 | 1.17 – 1.18 | 17% - 18% | 22 | 0.60 | 40% | ||

| 23 - 25 | 1.16 – 1.25 | 16% - 25% | 26 | 0.60 | 40% | ||

| 27 - 28 | 1.12 – 1.22 | 11% - 22% | - | - | - | ||

| Males | < 0.001 | 1 - 3 | 1.20 - 1.22 | 20% - 22% | 4 | 0.605 | 39% |

| 5 - 7 | 1.13 – 1.20 | 13% - 20% | 8 | 0.601 | 38% | ||

| 9 - 10 | 1.15 – 1.13 | 13% - 15% | 11 | 0.591 | 41% | ||

| 12 - 14 | 1.18 – 1.19 | 18% | 15 | 0.579 | 42% | ||

| 16 - 18 | 1.21 – 1.20 | 19% - 20% | 19 | 0.588 | 41% | ||

| 20 - 21 | 1.16 – 1.18 | 16% - 18% | 22 | 0.594 | 41% | ||

| 23 - 25 | 1.16 - 1.25 | 16% - 25% | 26 | 0.601 | 40% | ||

| 27 - 28 | 1.16 – 1.21 | 16% - 21% | - | - | - | ||

| Females | < 0.001 | 1 - 3 | 1.22 – 1.23 | 22% - 23% | 4 | 0.605 | 40% |

| 5 - 7 | 1.15 – 1.19 | 15% - 19% | 8 | 0.620 | 38% | ||

| 9 - 10 | 1.12 – 1.16 | 12% - 16% | 11 | 0.582 | 42% | ||

| 12 - 14 | 1.15 – 1.17 | 15% - 17% | 15 | 0.583 | 42% | ||

| 16 - 18 | 1.17 – 1.22 | 17% - 22% | 19 | 0.579 | 42% | ||

| 20 - 21 | 1.16 – 1.17 | 16% - 17% | 22 | 0.607 | 39% | ||

| 23 - 25 | 1.18 – 1.24 | 18% - 24% | 26 | 0.608 | 39% | ||

| 27 - 28 | 1.13 – 1.18 | 13% - 18% | - | - | - |

| Positive probability (phase) | P-value | IRR1 | Percentual effect | Negative probability (phase) | P-value | IRR1 | Percentual effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primiparous | New Moon | < 0.001 | 1.16 | 16% | First Quarter | < 0.001 | 0.97 | 3% |

| Full Moon | 0.89 | 11% | ||||||

| Multiparous | New Moon | < 0.001 | 1.14 | 14% | First Quarter | < 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.9% |

| Full Moon | < 0.01 | 0.88 | 11% |

| P-value | Positive probability (phase) | IRR1 | Percentual effect | Negative probability (phase) | IRR1 | Percentual effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | < 0.001 | New Moon | 1.148 | 15% | First Quarter | 0.99 | 2% |

| Full Moon | 0.89 | 11% | |||||

| Female | < 0.001 | New Moon | 1.151 | 15% | First Quarter | 0.98 | 2% |

| Full Moon | 0.88 | 12% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).