1. Introduction

Mastitis is a prevalent and economically significant disease affecting dairy cattle worldwide. It leads to substantial production and financial losses, challenging the sustainability of dairy farming systems. The economic impact of mastitis arises from reduced milk production and quality, shorter productive lifespan of cows, increased treatment and labor costs, and complications such as infertility and lameness [

1,

2,

3].

Mastitis manifests in two forms: clinical and subclinical. Clinical mastitis is characterized by visible signs such as swelling, heat, and abnormal milk, whereas subclinical mastitis (SCM) lacks overt symptoms, making it more challenging to detect. Despite its asymptomatic nature, SCM can lead to significant milk yield losses and adversely affect milk quality. The SCC) in milk serves as a reliable diagnostic tool for SCM, with an optimal threshold of 200,000 cells/mL indicating increased risk [

4]. Clinical mastitis can reduce dairy farming productivity by up to 70% [

5]. SCM also has significant financial implications, with potential milk production declines of up to 72% and a 25% chance of culling affected cows [

6]. Thus, SCM is often called the silent threat in profitable dairy operations. SCM prevalence is notably higher in developing countries, where cattle are kept in crowded, unsanitary conditions, manual milking is common, and diagnostic tools are limited [

7]. In Bangladesh, traditional dairy practices lack sufficient hygiene management, promoting SCM spread [

8].

In Bangladesh, SCM prevalence among lactating varies regionally, influenced by agricultural practices, environmental factors, and management strategies. Studies have reported SCM prevalence ranging from 28% in Khulna [

9] to 71.9% in Jhenaidah [

10], with intermediate prevalence observed in Shahjadpur, Sirajganj (67.5%, [

11], Chattogram (50%, [

12], and Brahmanbaria (28.75%,[

13]. Factors such as cow breed, age, and management practices affect SCM prevalence, with crossbred and older cows (≥7 years) at higher risk [

11,

13], while poor hygiene and inadequate milking techniques contribute to higher prevalence [

10,

12].

Although the prevalence of SCM in Bangladesh has been documented, there is limited data quantifying its economic impact. The annual economic loss from reduced milk production alone due to SCM in Bangladesh is Tk. 122.6 million (US

$ 2.11 million) [

14]. Understanding the financial implications of SCM is crucial for developing effective management strategies and improving the profitability of dairy farms. Therefore, this study aims to assess the economic losses associated with SCM in crossbred dairy cattle in Sirajganj district, Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, Population and Husbandry Practices

This study took place in the Siarjganj district of Bangladesh, a region renowned for its numerous dairy farms. The target population comprised high-yielding dairy cattle from Bangladesh, while the study population included dairy cattle from the specific study area. In this region, the majority of cattle were Holstein Friesian crosses, followed by Sahiwal and Jersey crosses. In September, Jumbo grass and black gram (“Mash Kalai”) seeds are sown in owner-specific pastures known as “bathan.” From December to mid-June, the cattle graze freely (

Figure 1 a,b) in the “bathan,” where temporary shelters are established for both the animals and their caretakers. Hand milking occurs twice daily, in the morning and afternoon, within these temporary shelters (

Figure 2a). After milking, the animals are given concentrates. During this period, caretakers also live in the “bathan” to ensure proper care and management. When the pasture or ‘bathan’ is flooded (June to August), the animals are moved to the owners’ cowshed premises (‘non-bathan’). For the remainder of the year, the animals are raised in either a semi-intensive management system for larger herds with more than 10 animals or an intensive management system (

Figure 2c) for herds with 10 or fewer animals. In these systems, the animals receive straw and concentrates at recommended levels based on their production performance. Straw and concentrates are provided during this time, and hand milking is also practiced (

Figure 2b). Artificial insemination is commonly used for breeding, and veterinarians from the Bangladesh Milk Producers Co-operative Union Limited (Milk Vita) offer disease diagnosis and clinical management.

2.2. Sampling Size Calculation and Sampling

The sample size (n) was calculated based on the following formula:

Using a Z-score of 1.96 for a 95% confidence level, an expected prevalence (p) of 44% (or 0.44) as reported by [

15], q = 1 - p, and a precision of 1.8% (or 0.018), the calculated sample size is 2921. Ultimately, 3174 cows were selected. The list of all dairy herds in the study area was obtained from Milk Vita. A simple random sample of 76 herds was chosen using Excel-generated random numbers, and all lactating dairy cows from these selected herds were included in the sample.

2.3. Collection of Bulk Milk Samples

Aseptically, 40 milliliters of composite milk sample, consisting of 10 milliliters from each teat, were collected from each cow and placed in a sterile falcon tube. The samples were then transported to the Milk Vita laboratory in an icebox, ensuring the journey

2.4. Counting Somatic Cells

The somatic cells in bulk milk were counted using the EKOMILK SCAN® analyzer, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. Cow-Level Data Collection

A pre-tested questionnaire was administered during bulk milk sampling to collect cow-level data, including herd ID, cow ID, age, breed, parity, lactation stage, daily milk yield, and history of clinical mastitis.

2.6. Milk Yield and Somatic Cell Count

2.6.1. Bathan Period

Milk yield loss associated with SCC was assessed using multivariable mixed-effects linear regression models to account for clustering at the herd level. Initially, a full model included SCC, age, breed, parity, pregnancy status, lactation stage, history of clinical mastitis, and other disease categories as fixed effects, with herd as a random effect. Non-significant variables were sequentially removed using backward elimination based on statistical significance (p > 0.05) and biological relevance, resulting in a final model retaining SCC, parity, pregnancy status, and lactation stage as key predictors. The SCC was centered at 200,000 cells/mL because dairy cows produce the highest milk yield at this level ([

16]). The mixed-effects model thus included SCC above 200,000, parity, age, pregnancy status, and lactation stage as fixed effects, with herd as a random effect. Regression coefficients (β), standard errors (SE), and p-values were derived from the final model, and SCC coefficients were interpreted as the estimated milk loss per 100,000-cell/mL increment above 200,000 cells/mL. Models were implemented in R using the ‘lmer’ function from the lme4 package, with significance testing performed via the ‘lmerTest’ package.

where

is the herd level random effect,

is the residual error and

i denotes a cow and j denotes a herd

2.6.2. Non-Bathan Period

The same backward elimination process was used for the data from the non-bathan period. The initial model considered SCC, parity, breed, age, pregnancy status, and lactation stage as fixed effects, with herd as a random intercept (Equation 2). The final model identified SCC, parity, age, pregnancy status, and lactation stage as significant predictors of milk yield. Regression coefficients (β), standard errors (SE), and p-values were derived from this mixed-effects model, with SCC coefficients representing milk loss per 100,000-cell/ml increase.

2.7. Milk Yield and Economic Loss Estimation

We estimated the milk yield loss associated with increased somatic cell count (SCC) using the regression coefficient () obtained from the final mixed-effects model. First, SCC values were rescaled to units of 100,000 cells/mL for easier interpretation (Equation 3). The regression coefficient was multiplied by each cow’s SCC value to calculate individual milk yield losses (liters/day), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were derived using the standard error of the coefficient. Losses were summed to obtain total herd loss and averaged to estimate per-cow loss. These results were then scaled to a 1,000-cow basis for standardization. The equations used to estimate milk yield loss per cow, per herd and per 1000 cow are provided below:

Expressing somatic cell in 100,000 cells/ ml milk:

Adjusted regression parameter and standard error: and

Estimating milk yield loss per cow:

Calculating 95% Confidence Interval (CI) per cow:

Calculating 95% Confidence Interval per cow:

Total loss (L/day):

Total variance of herd milk loss:

Total

Average loss per cow=, Average

Estimating loss per 1000 cow=

Estimating

Economic losses were computed by multiplying the estimated milk loss by the market price of milk (60 Taka per liter). These economic losses were similarly expressed per cow, for the entire herd, and for a standardized 1,000-cow herd. Finally, to provide international comparability, the 1,000-cow economic losses were converted to USD using a fixed exchange rate of 1 USD = 122 BDT. The equations used to estimate economic loss per cow, per herd and per 1000 cow are provided below:

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Bathan Period

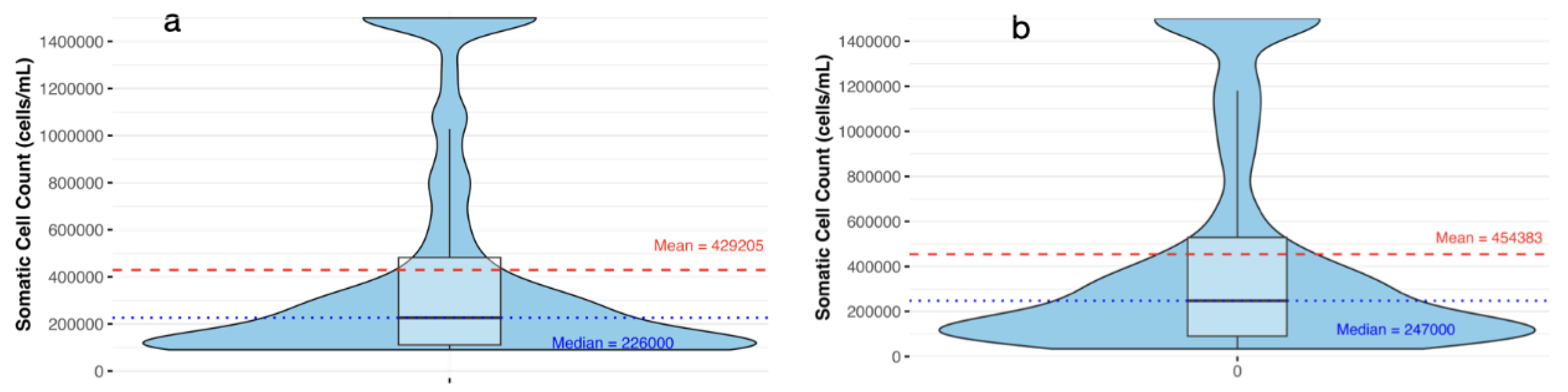

During the “bathan” period, 2,208 measurements of cow somatic cell count (SCC) were recorded. The average SCC was 429,000, with a range from 90,000 to 1,500,000 (

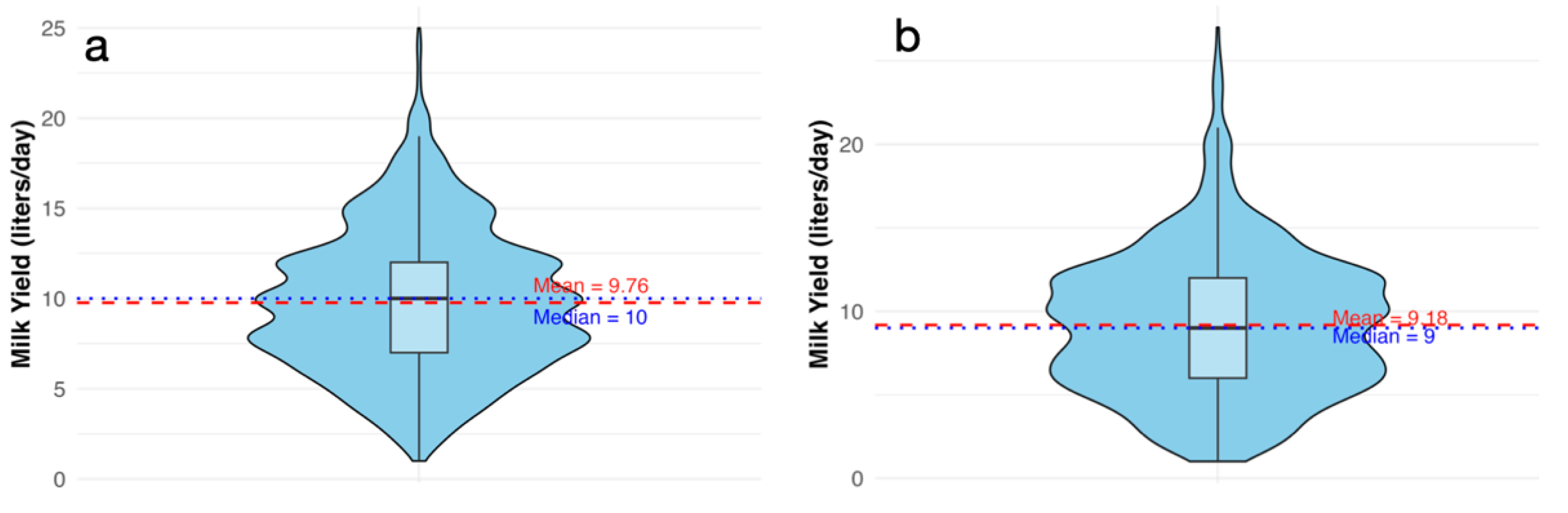

Figure 3a). The average milk yield was 9.76 liters, ranging from 1 to 25 liters (

Figure 4a). The mean age of the cows was 5.4 years, with a range from 2 to 12.3 years. The mean number of parities was 3, ranging from 1 to 9. The mean lactation stage was 5.9 months, with a range from 15 days to 25 months.

3.1.2. Non-Bathan Period

During the “non-bathan” period, 965 cow SCC measurements were recorded. The average SCC was 454,383, with a range from 33,700 to 1,500,000 (

Figure 3b). The average milk yield was 9.18 liters, ranging from 1 to 27 liters (

Figure 4b). The mean age of the cows was 5.54 years, with a range from 2.75 to 15.83 years. The mean number of parities was 3, ranging from 1 to 13. The mean lactation stage was 7.1 months, with a range from 3 days to 36 months.

3.2. Factors Significantly Impacting Milk Yield

During the ‘bathan’ period, SCC was negatively associated with milk yield, with each 100,000-cell/ml increase resulting in a loss of approximately 378 ml of milk (β = −3.78×10⁻⁷, p = 0.01). During the ‘non-bathan’ period, the loss was greater — about 679 ml per 100,000-cell/ml increase (β = −6.79×10⁻⁷, p = 0.008). Additionally, age, parity, pregnancy, and lactation stage were identified as significant predictors of milk yield (

Table 1)

3.3. Milk Yield and Economic Loss per Cow:

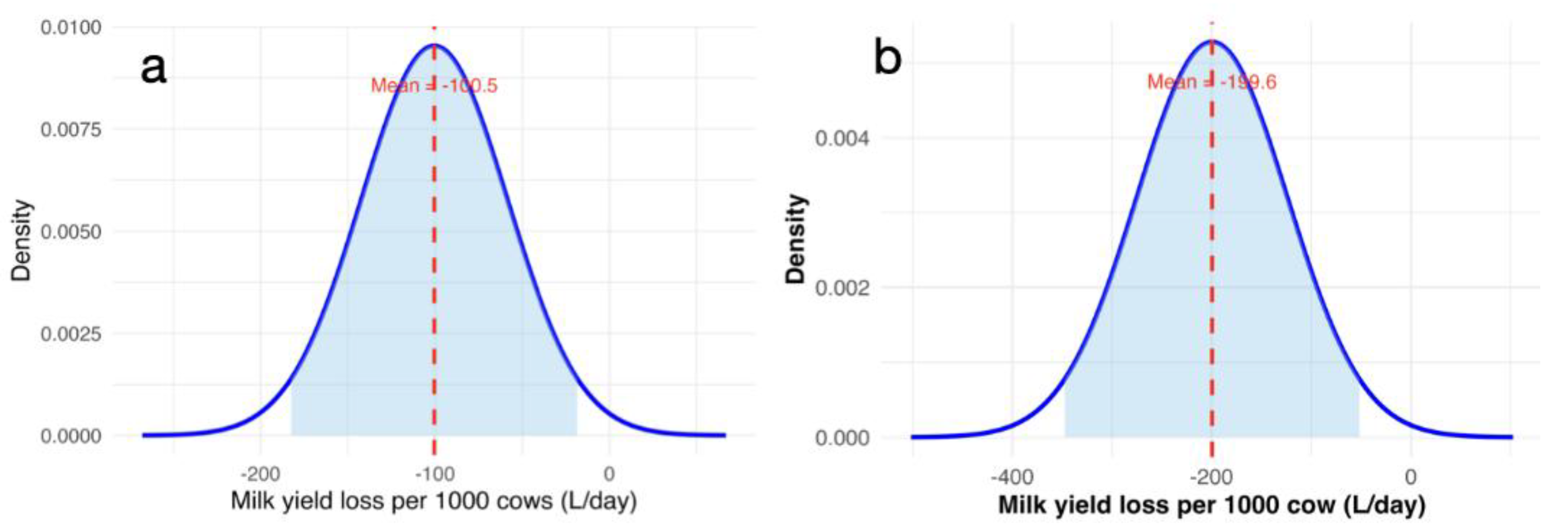

During the ‘bathan’ period, the average milk yield loss per cow was 0.100 liters (95% CI: 0.097−0.104), resulting in an estimated economic loss of BDT 6.03 per cow (95% CI: BDT 5.83−6.23). During the ‘non-bathan’ period, milk production significantly decreases when the somatic cell count (SCC) surpasses 200,000 cells/mL. On average, each cow loses about 0.2 liters of milk per day (95% CI: 0.191−0.208 liters) for every 100,000 increases in SCC above this threshold. This translates to an average daily loss of approximately 12 Taka per cow (95% CI: 11.45−12.50 Taka) (Table 2).

3.4. Milk Yield and Economic Loss for 1,000-Cow

During the ‘bathan’ period, the daily total milk loss was 100.5 liters per 1,000 cows (95% CI: 97.10−103.80), which translates to BDT 6,028.90 (95% CI: BDT 5827.6−6230.2) or USD 49.42 (95% CI: USD 47.77−51.07) (

Table 3,

Figure 5a). In contrast, during the ‘non-bathan’ period, the estimated daily total milk loss was nearly 200 liters per 1,000 cows (95% CI: 190.87−208.34), equating to BDT 11,976.2 (95% CI: BDT 11452.0−12500.4) or USD 98.17 (95% CI: USD 93.87−102.46) (

Table 3,

Figure 5b).

3.5. Herd-Specific Milk-Yield Across Farms

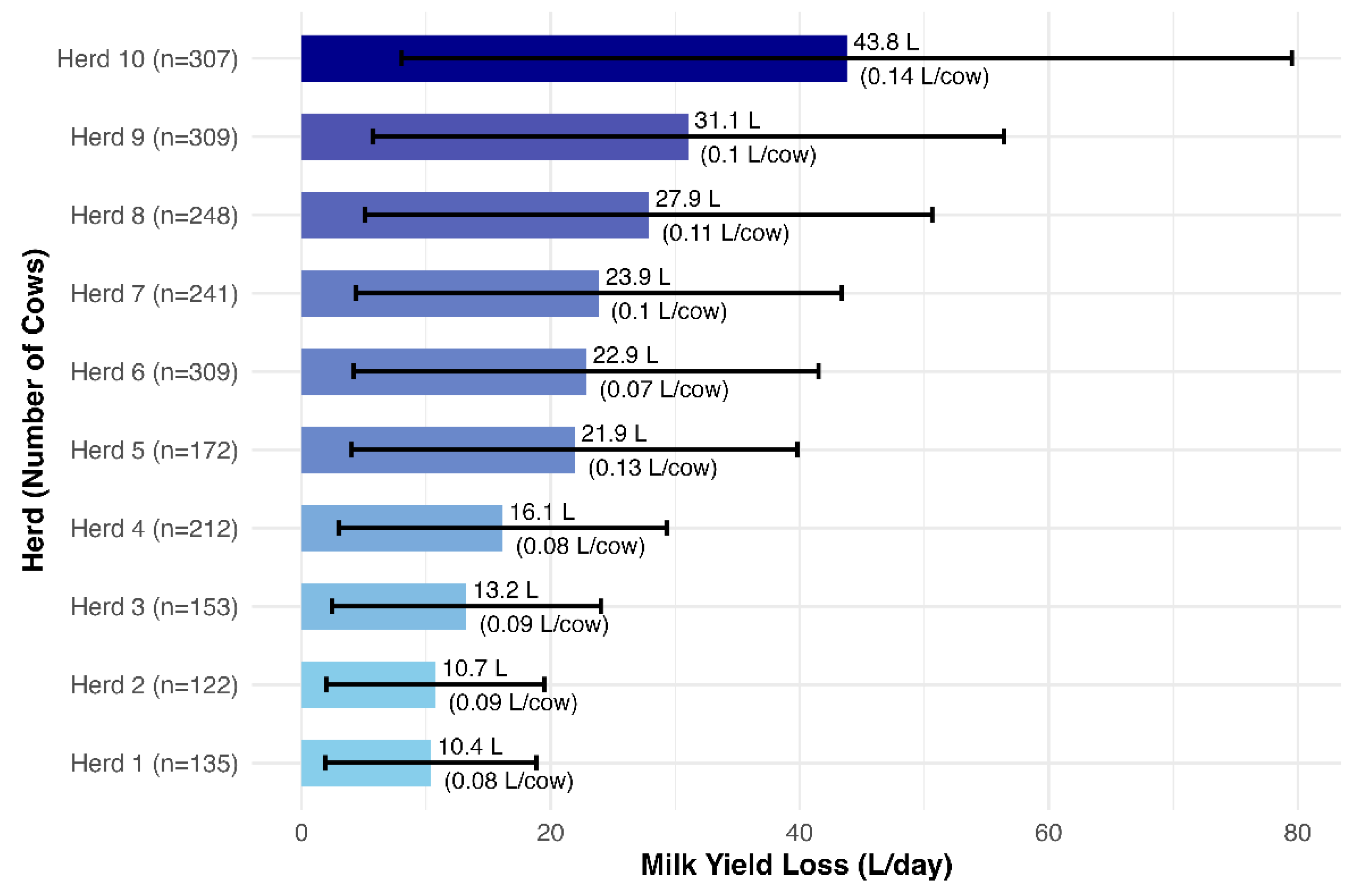

Figure 6 displays the milk yield loss specific to each herd across 10 farms, with the number of cows sampled per farm shown in parentheses. The light blue bars indicate the average milk yield loss per herd, while the vertical black lines represent the variability (95% confidence interval) around the mean. There is significant variation in milk yield loss among the farms, with Farm 1 experiencing the lowest loss at 10.4 liters and Farm 10 the highest at 43.8 liters.

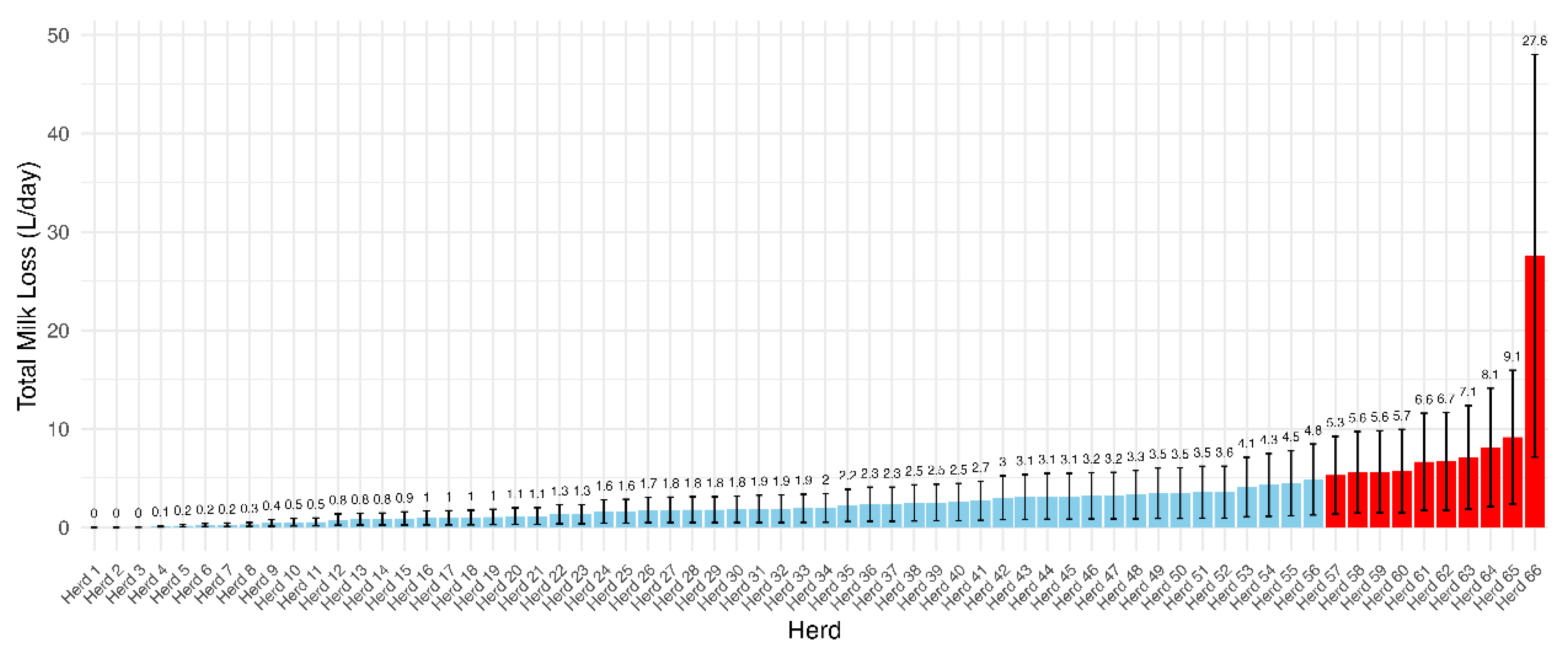

During the ‘non-bathan’ period, the herd-level milk yield loss varied from about 0 liters per day to 27.56 liters per day. The median loss was around 1.94 liters per day, while the average loss across herds was approximately 2.91 liters per day (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

This study is the first in Bangladesh to predict the milk yield loss and economic impact of subclinical mastitis in dairy cattle. We observed significant variations in milk yield loss during both the ‘bathan’ and ‘non-bathan’ periods, as well as across different herds in these periods. Factors such as cow comfort and the availability of abundant green fodder may contribute to these differences. Implementing veterinary extension programs to educate farmers on cow comfort and ensuring year-round access to green grass or silage could help to reduce the somatic cell count, thereby enhancing milk yield and increasing farmers’ profitability.

In this study, the average cow-level SCC per ml of milk differed between the ‘bathan’ (429,000) and ‘non-bathan’ (454,383) periods. In the USA, the standard SCC threshold for identifying cows with subclinical mastitis is ≤500,000 cells per ml of milk [

17]. Bangladesh currently does not have an official threshold for this measurement. A gold standard study determined the SCC threshold for Bangladesh to be ≤100,000 cells per ml of milk [

18]. We are using a large number of milk samples tested for SCC to establish the SCC threshold for diagnosing subclinical mastitis in Bangladeshi cows through a Bayesian mixture modeling approach (Unpublished data).

During the ‘bathan’ period, cows are allowed to roam freely and have access to an ample supply of green grass. This environment significantly contributes to cow comfort and reduces stress, which are critical factors influencing SCC. The presence of natural antioxidants in green grass, such as vitamins C and E, carotenoids, and polyphenols, plays a pivotal role in enhancing the immune response and reducing oxidative stress in dairy cows. Increased antioxidant intake from fresh forage is associated with improved udder health and a significant reduction in SCC levels [

19,

20]. In contrast, during the ‘non-bathan’ period, cows are primarily housed indoors, often tied with ropes, and lack access to fresh green grass. This constrained environment can lead to increased stress levels and reduced antioxidant intake, both of which are potential contributors to higher SCC levels [

21,

22]. Therefore, the combination of improved cow comfort and the antioxidant-rich diet during the ‘bathan’ period may be responsible for the relatively lower SCC compared to the ‘non-bathan’ period.

Elevated SCC are consistently linked to reduced milk production. For example, a large Irish study of mostly Holstein and crossbred cows found that milk production losses increased with higher SCC across lactations. Higher-producing cows tend to lose more milk per unit increase in SCC than lower-producing cows [

23]. Cattle grazing practices and seasonal feeding markedly affect how elevated SCC impact milk yield. In our study, freely grazing cows during the ‘bathan’ period (lush pasture access) suffered only ~0.10 L/cow/day loss, whereas confined cows in the ‘non-bathan’ period (limited fodder) lost ~0.20 L/day – a twofold increase. This aligns with global findings that poor management, housing, and nutrition raise SCC and reduce yield: for example, better hygiene and proper nutrition help in reducing milk somatic cells [

24]. A U.S. analysis estimated that cows with chronic high SCC (≥100,000 cells/mL over consecutive tests) suffered daily losses of US

$1.20–2.06 per cow as SCC remained elevated [

25]. Global reviews highlight that mastitis (clinical or subclinical) is one of the costliest dairy cattle diseases worldwide, with per-cow losses often in the tens to hundreds of dollars per lactation. For instance, a Colombian study estimated about US

$70.3 per cow per year lost due to milk yield reduction from mastitis [

26].

We observed wide farm-to-farm differences in SCC losses, mirroring global patterns that farm-specific factors are key. Farm management and animal factors strongly influence SCC and associated yield loss. Poor milking hygiene and high environmental bacterial load elevate SCC [

27]. For example, a review in South Asia identified stall--feeding (limited grazing), overcrowding, cracked or muddy floors, open drains, flies, and poor drainage as key drivers of subclinical mastitis [

28,

29]. Correspondingly, improving cow and milker hygiene, cleaning bedding, and preventing environmental contamination are universally recommended control measure. Overall, these findings emphasize that farm-specific factors – from milking procedures to barn conditions to cow cleanliness – critically affect SCC. Milking hygiene is a critical determinant of udder health, as cleaning and drying teats before milking, using sanitized equipment, and milking infected cows last have all been shown to reduce bacterial transmission and lower SCC. Housing and environmental conditions also play a major role, as poor housing—characterized by wet, muddy, or cracked floors and inadequate drainage—is a well-documented risk factor for elevated SCC. Providing clean, dry bedding and preventing overcrowding further helps in reducing SCC [

29]. Cow hygiene itself is equally important, with studies showing that lower udder and leg hygiene scores—indicating reduced dirt and manure contamination—are strongly associated with reduced SCC. Nutrition also plays a pivotal role, as adequate feeding supports immune competence, whereas deficiencies can heighten mastitis risk. Reviews highlight that cows with year-round access to quality forage and well-balanced rations consistently maintain lower SCC levels [

28]. Finally, monitoring and culling strategies are critical—regular SCC testing, ideally on a monthly basis, enables early detection of subclinical mastitis, allowing for timely treatment or culling of chronically infected cows to protect overall herd health [

29].

5. Conclusions

Milk yield and economic losses varied across herds, highlighting the impact of herd-level management and cow-level factors such as age, parity, pregnancy, and lactation stage. Our findings suggest that higher SCC and associated milk losses were observed during the non-bathan period, likely linked to cows being confined and deprived of fresh green fodder. In contrast, during the bathan period, freely grazing cows had lower losses. Therefore, improving cow comfort—through regular access to green grass, silage, or pasture throughout the year—and proper housing management may help reduce SCC, maintain milk yield, and enhance economic returns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A K M Anisur Rahman; Data curation, Muhammad Aktaruzzaman, Mst. Tahomina Akter and Md. Mazhar Islam; Formal analysis, Muhammad Aktaruzzaman, Md. Mazhar Islam and Md. Shaffiul Alam; Funding acquisition, A K M Anisur Rahman; Investigation, Md. Mazhar Islam; Methodology, Muhammad Aktaruzzaman, M. Ariful Islam, Solama Akter Shanta, Mst. Tahomina Akter and Muhammad Tofazzal Hossain; Project administration, A K M Anisur Rahman; Resources, M. Ariful Islam and A K M Anisur Rahman; Software, Muhammad Aktaruzzaman, Solama Akter Shanta and Mst. Tahomina Akter; Supervision, M. Ariful Islam and Muhammad Tofazzal Hossain; Validation, Solama Akter Shanta, Muhammad Tofazzal Hossain and Md. Shaffiul Alam; Visualization, A K M Anisur Rahman; Writing – original draft, Muhammad Aktaruzzaman, Solama Akter Shanta, Mst. Tahomina Akter, Md. Mazhar Islam and Md. Shaffiul Alam; Writing – review & editing, M. Ariful Islam, Muhammad Tofazzal Hossain and A K M Anisur Rahman.

Funding

This study was supported by Bangladesh Agricultural University Research System Funded project: 2021/1399/BAU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Welfare and Experimentation Ethical Committee (AWEEC) of Bangladesh Agricultural University (AWEEC/BAU/2022/ approved on 20 December 2022). Milk samples were collected by trained animal handlers or caretakers in a manner that caused no pain, distress, or harm to the animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated from this study are presented in the corresponding tables and figures.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the farmers who willingly participated in this study and contributed their time and milk from their animals.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCC |

Somatic Cell Count |

| SCM |

Subclinical Mastitis |

| SE |

Standard Error |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| BDT |

Bangladeshi Taka |

| USD |

United States Dollar |

References

- Bezman, D.; Lemberskiy-Kuzin, L.; Katz, G.; Merin, U.; Leitner, G. Influence of Intramammary Infection of a Single Gland in Dairy Cows on the Cow’s Milk Quality. Journal of Dairy Research 2015, 82, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfenson, D.; Leitner, G.; Lavon, Y. The Disruptive Effects of Mastitis on Reproduction and Fertility in Dairy Cows. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2015, 14, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, F.J.S.; Santman-Berends, I.M.G.A.; Lam, T.J.G.M.; Hogeveen, H. Failure and Preventive Costs of Mastitis on Dutch Dairy Farms. Journal of Dairy Science 2016, 99, 8365–8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petzer, I.-M.; Karzis, J.; Donkin, E.F.; Webb, E.C.; Etter, E.M.C. Somatic Cell Count Thresholds in Composite and Quarter Milk Samples as Indicator of Bovine Intramammary Infection Status. Onderstepoort j. vet. res. 2017, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijps, K.; Lam, T.J.; Hogeveen, H. Costs of Mastitis: Facts and Perception. Journal of Dairy Research 2008, 75, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammadi, M.; Haine, D.; Kelton, D.F.; Barkema, H.W.; Hogeveen, H.; Keefe, G.P.; Dufour, S. Herd-Level Mastitis-Associated Costs on Canadian Dairy Farms. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, M.S.; Rahman, Md.M.; Persson, Y.; Derks, M.; Sayeed, Md.A.; Hossain, D.; Singha, S.; Hoque, Md.A.; Sivaraman, S.; Fernando, P.; et al. Subclinical Mastitis in Dairy Cows in South-Asian Countries: A Review of Risk Factors and Etiology to Prioritize Control Measures. Vet Res Commun 2022, 46, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Nasir, T. Smart Practices in Modern Dairy Farming in Bangladesh: Integrating Technological Transformations for Sustainable Responsibility. Administrative Sciences 2025, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohidullah, M.; Hossain, Md.J.; Alam, M.A.; Rahman, N.; Salauddin, Md.; Matubber, B. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Sub-Clinical Mastitis in Lactating Dairy Cows with Special Emphasis on Antibiogram of the Causative Bacteria in Bangladesh. AJDFR 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, Md.A.; Rahman, Md.A.; Bari, M.S.; Islam, A.; Rahman, Md.M.; Hoque, Md.A. Prevalence of Subclinical Mastitis and Associated Risk Factors at Cow Level in Dairy Farms in Jhenaidah, Bangladesh. AAVS 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajib, M.M.R.; Atiquzzaman, A.S.M.; Devnath, B.; Rahima, F.F.; Jalil, M.A. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Sub-Clinical Mastitis in Lactating Cows in Selected Area of Bangladesh. Research in Agriculture Livestock and Fisheries 2024, 11, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, J.; Chowdhury, S.; Chowdhury, G.M. Prevalence of Bovine Subclinical Mastitis and Antibiogram Pattern of Isolated Organisms from Mastitic Milk in Chattagram, Bangladesh. AJOAIR 2024, 7, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.U.; Shahadat, H.M.; Chakma, S.S.; Islam, F.; Islam, R.; Islam, T.; Mahfuz, S. Prevalence of Subclinical Mastitis of Dairy Cows in Bijoynagar Upazila under Brahmanbaria District of Bangladesh. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, M.; Samad, M.; Saha, S. Influence of Host Level Factors on Prevalence and Economics of Subclinical Mastitis in Dairy Cows in Bangladesh. 2003.

- Bari, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Persson, Y.; Derks, M.; Sayeed, M.A.; Hossain, D.; Singha, S.; Hoque, M.A.; Sivaraman, S.; Fernando, P. Subclinical Mastitis in Dairy Cows in South-Asian Countries: A Review of Risk Factors and Etiology to Prioritize Control Measures. Veterinary Research Communications 2022, 46, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, L.; Guimaraes, I.; Noyes, N.R.; Caixeta, L.S.; Machado, V.S. Effect of Subclinical Mastitis Detected in the First Month of Lactation on Somatic Cell Count Linear Scores, Milk Yield, Fertility, and Culling of Dairy Cows in Certified Organic Herds. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 2140–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegg, P.L. A 100-Year Review: Mastitis Detection, Management, and Prevention. Journal of Dairy Science 2017, 100, 10381–10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumon, S.M.M.R.; Parvin, Mst.S.; Ehsan, Md.A.; Islam, Md.T. Relationship between Somatic Cell Counts and Subclinical Mastitis in Lactating Dairy Cows. Vet World 2020, 13, 1709–1713, doi:10.14202/vetworld.2020.1709-1713. [CrossRef]

- Nudda, A.; Carta, S.; Battacone, G.; Pulina, G. Feeding and Nutritional Factors That Affect Somatic Cell Counts in Milk of Sheep and Goats. Veterinary Sciences 2023, 10, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre-Santos, S.; Royo, L.J.; Martínez-Fernández, A.; Menéndez-Miranda, M.; Rosa-García, R.; Vicente, F. Influence of the Type of Silage in the Dairy Cow Ration, with or without Grazing, on the Fatty Acid and Antioxidant Profiles of Milk. Dairy 2021, 2, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogalski, Z.; Momot, M. The Housing System Contributes to Udder Health and Milk Composition. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, A.; Weary, D.M.; Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Invited Review: The Welfare of Dairy Cattle Housed in Tiestalls Compared to Less-Restrictive Housing Types: A Systematic Review. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 9383–9417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, F.; O’Grady, L.; More, S.J. Investigating a Dilution Effect between Somatic Cell Count and Milk Yield and Estimating Milk Production Losses in Irish Dairy Cattle. Journal of Dairy Science 2013, 96, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhussien, M.N.; Dang, A.K. Milk Somatic Cells, Factors Influencing Their Release, Future Prospects, and Practical Utility in Dairy Animals: An Overview. Vet World 2018, 11, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadrich, J.C.; Wolf, C.A.; Lombard, J.; Dolak, T.M. Estimating Milk Yield and Value Losses from Increased Somatic Cell Count on US Dairy Farms. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101, 3588–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ubaldo, A.L.; Rivero-Perez, N.; Valladares-Carranza, B.; Velázquez-Ordoñez, V.; Delgadillo-Ruiz, L.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A. Bovine Mastitis, a Worldwide Impact Disease: Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Viable Alternative Approaches. Veterinary and Animal Science 2023, 21, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejyong, T.; Chanachai, K.; Immak, N.; Prarakamawongsa, T.; Rukkwamsuk, T.; Tago Pacheco, D.; Phimpraphai, W. An Economic Analysis of High Milk Somatic Cell Counts in Dairy Cattle in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 958163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussien, M.N.; Dang, A.K. Milk Somatic Cells, Factors Influencing Their Release, Future Prospects, and Practical Utility in Dairy Animals: An Overview. Vet World 2018, 11, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bari, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Persson, Y.; Derks, M.; Sayeed, M.A.; Hossain, D.; Singha, S.; Hoque, M.A.; Sivaraman, S.; Fernando, P.; et al. Subclinical Mastitis in Dairy Cows in South-Asian Countries: A Review of Risk Factors and Etiology to Prioritize Control Measures. Vet Res Commun 2022, 46, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).