Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

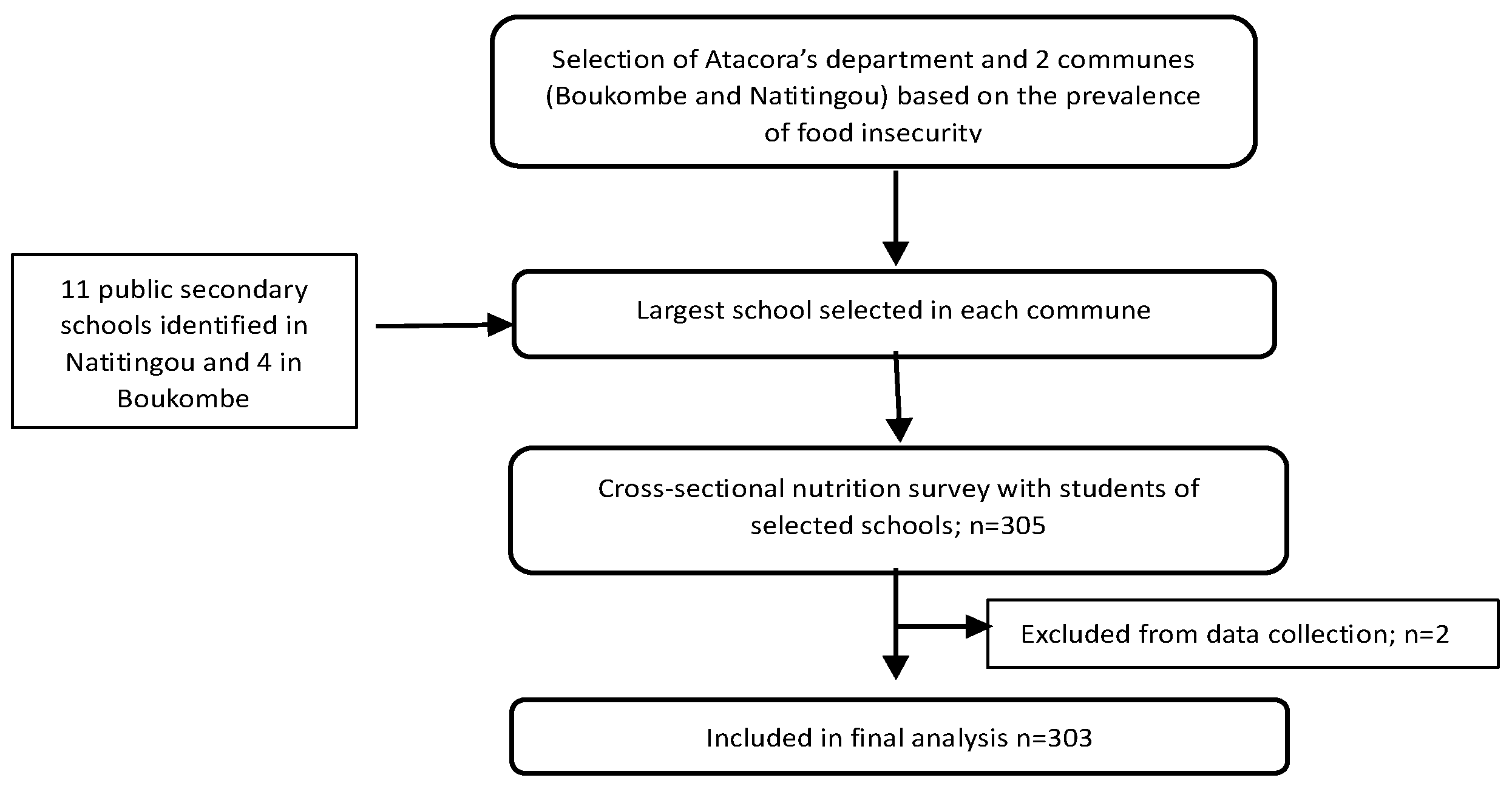

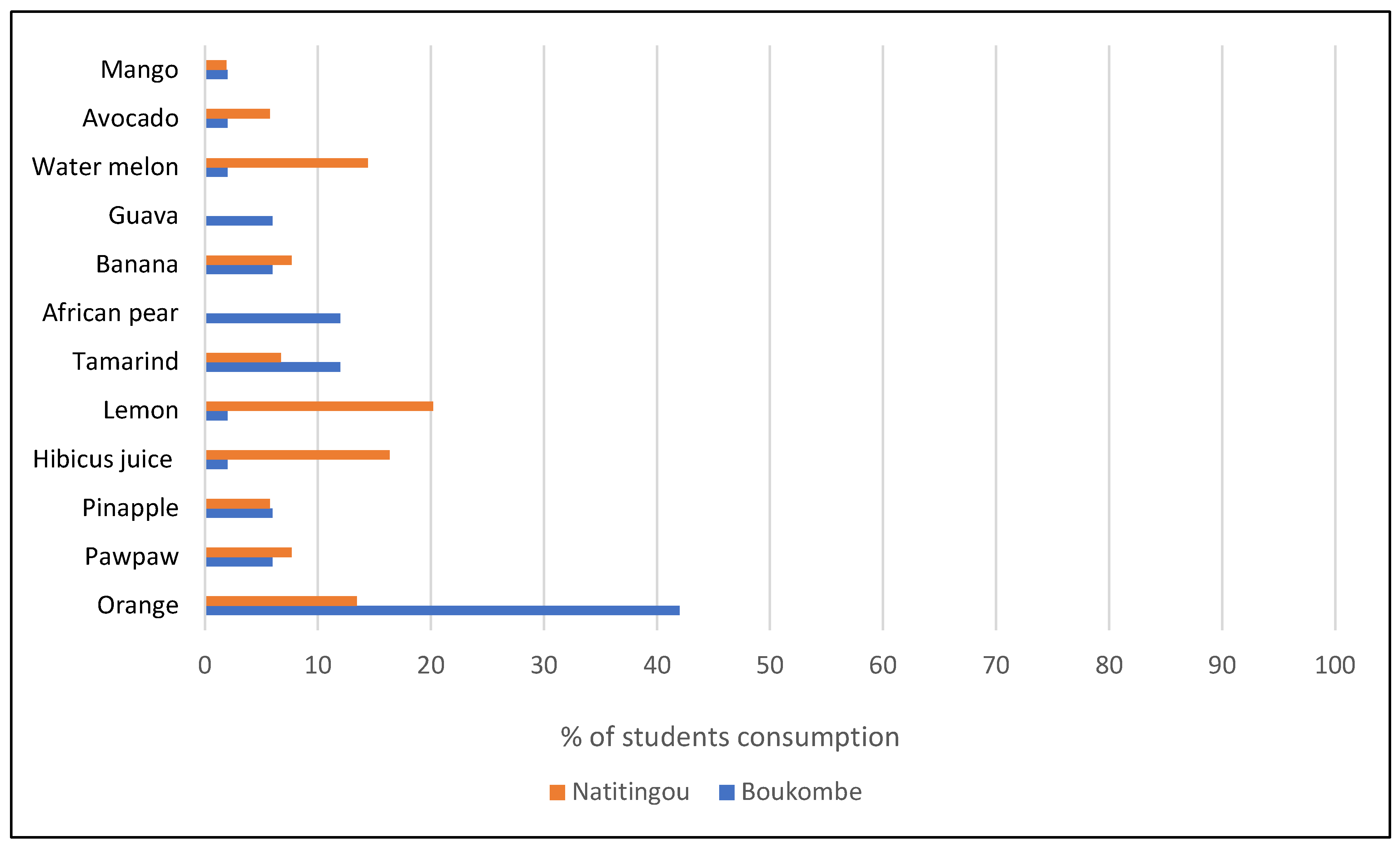

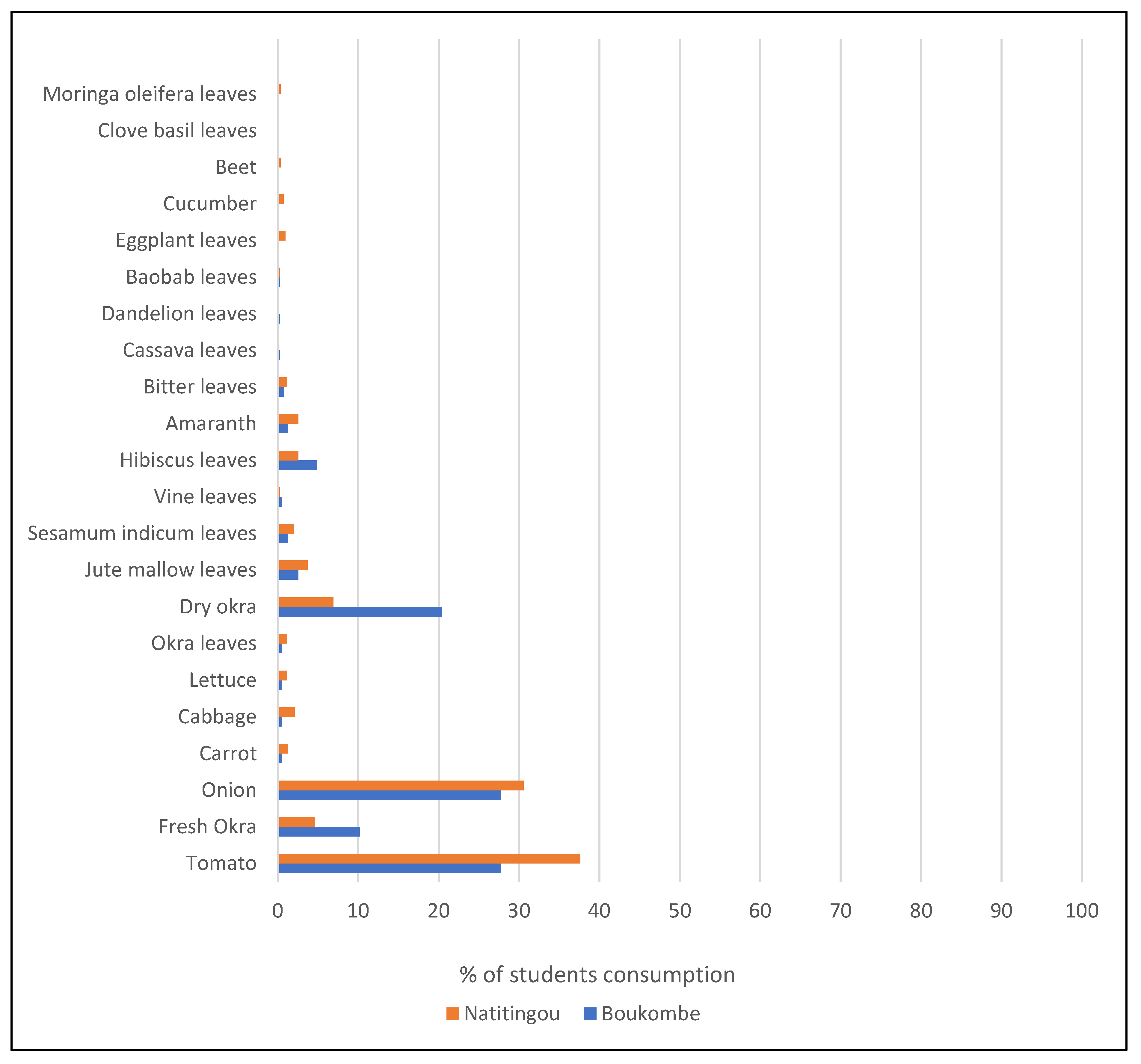

Fruit and vegetables (F&V) are recommended for a healthy life. Adolescence is a critical period for the onset of eating disorders and future health. F&V consumption among adolescents is globally low, making this group a key target for interventions. This cross-sectional study aimed to assess F&V consumption among secondary school students in the food-insecure communes of Boukombe (rural) and Natitingou (urban), Benin. Using probabilistic random sampling, 303 students completed F&V intake frequency questionnaires and 24-hour dietary recalls on school and non-school days. Poisson models identified factors associated with F&V consumption. Results showed that only 8.8% (Boukombe) and 11% (Natitingou) of students consumed fruit at least twice per day, while 9.9% and 11.4% consumed vegetables at least twice per day. Over 80% of students did not eat fruit in the preceding 24 hours. On average, 45.5% of students in Boukombe and 68% in Natitingou consumed at least three types of vegetables on school days. The most commonly consumed fruits were oranges in Boukombe and oranges with lemons in Natitingou. Factors influencing fruit consumption included sex (P=0.00582), age (P=0.0472), and mothers’ occupation (P=0.03385), while commune (P=0.00017) and ethnic group affected vegetable consumption. Such low F&V consumption among surveyed students is a matter of public health concern, as it is likely to affect their health―in terms of micronutrient deficiency―and intellectual performance. These results should incentivize nutrition researchers, project managers, public health officials, and policymakers to (re)design and implement broader measures targeting secondary school students’ dietary practices to increase their F&V consumption.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Socioeconomic data

- -

- Fruit and vegetable consumption frequency data

- -

- 24-hour dietary recall data

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Socio-Economic Data

3.2. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Frequency Based on the F&V Frequency Consumption Questionnaire

3.3. Number of Fruits and Vegetables Consumed Based on 24-Hour Dietary Recall

3.4. Fruits Consumed Based on 24-Hour Recall

3.5. Vegetables Consumed Based on 24-Hour Recall

3.6. Factors Associated with Fruit Consumption

3.7. Factors Associated with Vegetable Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cole, M.B.; Augustin, M.A.; Robertson, M.J.; Manners, J.M. The science of food security. npj Sci. Food 2018, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier Ph, Delpeuch F, Maire B. Le complexe “malnutrition-infection” : premier problème de santé publique chez les populations défavorisées. Médecine Mal Infect. 1996 Apr 1;26:366–70.

- WHO. Africa’s health depends on improved nutrition [Internet]. WHO | Regional Office for Africa. 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/africas-health-depends-improved-nutrition.

- INSAE, PAM. analyse globale de la vulnérabilité de la sécurité alimentaire et de la nutrition Benin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 Nov 16]. Available from: https://instad.bj/images/docs/insae-statistiques/sociales/Securite%20alimentaire%20et%20nutrition/RapportAGVSA_2017.pdf.

- African Development Bank. COMPACT BENIN POUR L’ALIMENTATION ET L’AGRICULTURE. 2023.

- INSAE, PAM. agvsan bénin 2017 - Recherche Google [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=agvsan+b%C3%A9nin+2017&sxsrf=AJOqlzVP67GsE4jtgzwuPEor7KdVlW2JcQ%3A1677249822716&ei=Hs34Y-WYK-nXxc8Pz9mxkAo&ved=0ahUKEwjln4e_sq79AhXpa_EDHc9sDKIQ4dUDCA8&uact=5&oq=agvsan+b%C3%A9nin+2017&gs_lcp=Cgxnd3Mtd2l6LXNlcnAQAzIECCMQJzoICAAQgAQQsANKBAhBGAFQvSJYvyZgiztoAnAAeACAAbQEiAGjDZIBBzMtMi4xLjGYAQCgAQHIAQHAAQE&sclient=gws-wiz-serp.

- INSAE, ICF. Enquête Démographique et de Santé au Bénin, 2017-2018. 2019.

- de Onis, M.; Borghi, E.; Arimond, M.; Webb, P.; Croft, T.; Saha, K.; De-Regil, L.M.; Thuita, F.; Heidkamp, R.; Krasevec, J.; et al. Prevalence thresholds for wasting, overweight and stunting in children under 5 years. Public Health Nutr 2018, 22, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFPA. Adolescents and Youth Dashboard - Nigeria | United Nations Population Fund [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Jun 17]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/data/adolescent-youth/BJ.

- Chaulet S, Riquin É, Avarello G, Malka J, Duverger P. Troubles des conduites alimentaires chez l’adolescent. J Pédiatrie Puériculture. 2018 Jun 1;31(3):113–45.

- Hooshmand, S. Dietary Diversity and Nutritional Status of Urban Primary School Children from Iran and India. J Nutr Disord Ther. 2013 Jan 1;03.

- Nago, E.S.; Verstraeten, R.; Lachat, C.K.; Dossa, R.A.; Kolsteren, P.W. Food Safety Is a Key Determinant of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in Urban Beninese Adolescents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris M, Longobardi C. Critical Period (Psychology) - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/critical-period-psychology.

- Brooks AM, Hanafin S, Molcho M, Gabhainn S, Cahill H. State of the nation’s children, Ireland 2010. 2010 Dec 1;

- Ruiz, L.D.; Zuelch, M.L.; Dimitratos, S.M.; Scherr, R.E. Adolescent Obesity: Diet Quality, Psychosocial Health, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors. Nutrients 2019, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziaei, R.; Shahi, H.; Dastgiri, S.; Mohammadi, R.; Viitasara, E. Fruit and vegetable intake and its correlates among high-school adolescents in Iran: a cross-sectional study. J. Public Heal. 2019, 28, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shikeri, A.B. Fruit and Vegetables’ Consumption among Children and Adolescents: Determinants of Consumption and Possible Solutions. Adv. Obesity, Weight. Manag. Control. 2017, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrvash B, Majlessi F, Montazeri A, Nedjat S, Shojaeezadeh D, Rahimi A, et al. Fruit and Vegetables Consumption among Adolescents: A Study from a Developing Country. World Appl Sci J. 2013 Jan 1;21:1502–11.

- Morris, J.; Briggs, M.; Zidenberg-Cherr, S. School-based gardens can teach kids healthier eating habits. Calif. Agric. 2000, 54, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Healthy Diet: Key Facts. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Nago, E.S.; Lachat, C.K.; Huybregts, L.; Roberfroid, D.; Dossa, R.A.; Kolsteren, P.W. Food, energy and macronutrient contribution of out-of-home foods in school-going adolescents in Cotonou, Benin. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 103, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darboux AJ, Sossa Jerome C, Falola LG. Etude de l’offre et du comportement alimentaires - ProQuest. Int J Innov Appl Stud. 2019;Vol. 27(N° 1):410–6.

- Agbanou BT. Dynamique de l’occupation du sol dans le secteur Natitingou-Boukombé (nord-ouest bénin) : de l’analyse diachronique à une modélisation prospective [Internet] [phdthesis]. Université Toulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II ; Université d’Abomey-Calavi (Bénin); 2018 [cited 2024 Jun 22]. Available from: https://theses.hal.science/tel-02476241.

- MEBOUNOU CC, DJAOUGA M, DJOMAMOU D. Apport de la cartographie numérique aux travaux cadastraux d’une portion du lotissement de YIMPORIMA dans la commune de NATITINGOU. 2019;

- Magnani R. Food and Nutrition technical assistance. Sampling guide. [Internet]. 1997 [cited 2024 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=16.+Magnani%2CR.+(1997).+Food+and+Nutrition+technical+assistance.+Sampling+guide.+%5Bcited+2022+Octobre+30%5D.+Available+from%3A+file%3A%2F%2F%2FC%3A%2FUsers%2Fadmin%2FDownloads%2FFANTA_-_Sampling_Guide%2520(1).pdf&oq=16.%09Magnani%2CR.+(1997).+Food+and+Nutrition+technical+assistance.+Sampling+guide.+%5Bcited+2022+Octobre+30%5D.+Available+from%3A+file%3A%2F%2F%2FC%3A%2FUsers%2Fadmin%2FDownloads%2FFANTA_-_Sampling_Guide%2520(1).pdf&aqs=chrome..69i57.866j0j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

- Delbosq S, Velasco V, Vercesi C, Gruppo Regionale HBSC Lombardia 2018, Vecchio LP. Adolescents’ Nutrition: The Role of Health Literacy, Family and Socio-Demographic Variables. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan;19(23):15719.

- Kristjansdottir, A.G.; Andersen, L.F.; Haraldsdottir, J.; de Almeida, M.D.V.; Thorsdottir, I. Validity of a questionnaire to assess fruit and vegetable intake in adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 60, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogill B. Food and nutrition technical assistance. Anthr Indic Meas Guide URL Httpswww Fantaproject Orgsitesdefaultfilesresourcesanthropometry-2003-ENG Pdf Accessed 2019-05-14WebCite Cache ID 78MvIDHOF [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2024 Apr 14]; Available from: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=90d1b6ef3275d1c3d723e1363301fd97f4261bf2.

- Gibson RS, Ferguson EL. An interactive 24-hour recall for assessing the adequacy of iron and zinc intakes in developing countries [Internet]. ILSI Press Washington, DC; 2008 [cited 2024 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/download/68047630/An_Interactive_24-Hour_Recall_for_Assess20210712-30399-1r342zm.pdf.

- Hounkpatin, W.A.; Koukou, E.; Termote, C.; Ntandou-Bouzitou, G.; Mitchodigni, I.; Bodjrènou, S.; Alaofè, H. Dietary Diversity Predicts the Adequacy of Micronutrient Intake in 6- to 23-Month-Old Children Regardless of the Season in Rural Southern Benin. Food Nutr. Bull. 2023, 44, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; A Ingwersen, L.; Vinyard, B.T.; Moshfegh, A.J. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M.; Ingwersen, L.A.; Moshfegh, A.J. Accuracy of dietary recall using the USDA five-step multiple-pass method in men: An observational validation study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004, 104, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochedy A, Ehlinger V, Godeau E. Habitudes alimentaires et activité physique des collégiens en 2018. Résultats de l’enquête nationale en collèges et en lycées chez les adolescents sur la santé et les substances- EnCLASS 2018. Rennes, Paris: EHESP; 2020 p. 10.

- Seidu, A.-A.; Aboagye, R.G.; Frimpong, J.B.; Iddrisu, H.; Agbaglo, E.; Budu, E.; Hagan, J.E.; Ahinkorah, B.O. Determinants of Fruits and Vegetables Consumption among In-School Adolescents in Ghana. Adolescents 2021, 1, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamport DJ, Saunders C, Butler LT, Spencer JP. Fruits, vegetables, 100% juices, and cognitive function. Nutr Rev. 2014 Dec 1;72(12):774–89.

- Yaméogo, T.M.; Sombié, I.; Kyelem, C.G.; Guira, O.; Lankoandé, D.; Coulibali, B.; Tapsoba, M.M.D.; Ilboudo, A.; Kissou, A.S.-L.; Bagbila, A.; et al. Determinants of Fruit and Vegetables Intake among Secondary School Pupils in the City of Bobo-Dioulasso (Burkina Faso): A Cross-Sectional Study. Open J. Intern. Med. 2018, 08, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Prevalence and correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents in Laos. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Heal. 2020, 33, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwa, M.; Subaita, F.; Choudhury, S.R.; Khalequzzaman; Al Mamun, M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.R.; Haque, M.A. Fruit and vegetables consumption among school-going adolescents: Findings from the baseline survey of an intervention program in a semi-urban area of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0252297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary. Les fruits et légumes de saison [Internet]. Neary. 2024 [cited 2024 Jan 3]. Available from: https://neary.fr/blogs/les-fruits-et-legumes/le-calendrier-de-fruits-et-legumes-de-saison.

- FreshPlaza. Les oranges au Bénin : une filière qui reste à construire [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.freshplaza.fr/article/9334734/les-oranges-au-benin-une-filiere-qui-reste-a-construire/.

- Zeidan, W.; Taweel, H.; Shalash, A.; Husseini, A. Consumption of fruits and vegetables among adolescents in Arab Countries: a systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S.M.; Serem, J.C.; Bester, M.J.; Mavumengwana, V.; Kayitesi, E. African Green Leafy Vegetables Health Benefits Beyond Nutrition. Food Rev. Int. 2021, 37, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadeiye E, Adekanmbi AE. FRUIT AND VEGETABLE CONSUMPTION AMONG PRIMARY SCHOOL PUPILS OF EGBEDA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA, OYO STATE, NIGERIA. Int J Fam Consum Sci. 2020;9:103–15.

- Fayet-Moore, F.; McConnell, A.; Cassettari, T.; Tuck, K.; Petocz, P.; Kim, J. Vegetable intake in Australian children and adolescents: the importance of consumption frequency, eating occasion and its association with dietary and sociodemographic factors. Public Health Nutr 2019, 23, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharairi, N.A.; Somerset, S. Parental work status and children's dietary consumption: Australian evidence. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groele, B.; Głąbska, D.; Gutkowska, K.; Guzek, D. Mother-Related Determinants of Children At-Home Fruit and Vegetable Dietary Patterns in a Polish National Sample. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Sánchez, A.D.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Mundo-Rosas, V. Socioeconomic characteristics of mothers and their relationship with dietary diversity and food group consumption of their children. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molz, P.; Pereira, C.S.; Reuter, C.P.; Prá, D.; Franke, S.I.R. Factors associated with the consumption of fi ve daily servings of fruits and vegetables by students. Rev. De Nutr. J. Nutr. 2019, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviniemi, M.T.; Orom, H.; Giovino, G.A. Race/ethnicity, psychological distress, and fruit/vegetable consumption. The nature of the distress-behavior relation differs by race/ethnicity. Appetite 2011, 56, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjadi, F.F.; Takeuchi, D.T.; Umoren, J. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Longitudinal Patterns of Family Mealtimes: Link to Adolescent Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 244–249.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of study | Location | Year | Target population | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional study (review) | 22 Arabic countries | 2023 | Adolescents 10-19 years |

A low proportion (10−29%) of adolescents met the five recommended daily F&V servings/portions target, with lower consumption of fruits than vegetables. | [41] |

| Cross-sectional study | Bangladesh | 2021 | Secondary school students 14−18 years | Low intake was observed among secondary school students in Bangladesh, where only 21% ate at least five servings/portions of F&V per day. | [38] |

| Cross-sectional study | Ghana | 2021 | Secondary school students | The prevalence of adequate F&V intake (both eaten at least twice a day) among secondary school student was 35.7% and 26.8%, respectively, and adequate F&V intake (both eaten at least five times a day) was 27.8%. | [34] |

| Cross-sectional study | Benin | 2019 | Adolescents 10−19 years |

Another study carried in Cotonou on adolescents has shown that only 8.6% of adolescents/students consumed F&V at least five times a day. | [22] |

| Cross-sectional study | Benin | 2010 | Secondary school students 13−19 years | The average quantity of daily fruit and vegetables intake was 97g. | [21] |

| Student characteristics | Boukombe | Natitingou | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Sex | Female | 56 | 56.57 | 117 | 59.39 | 0.62 |

| Male | 43 | 43.43 | 80 | 40.61 | ||

| Age (years, SD) | 15.88 ± 2.72 | 15.32 ± 2.72 | 0.12 | |||

| School grade | 6th grade | 28 | 9.5 | 35 | 11.8 | <0.001 |

| 7th grade | 5 | 1.7 | 43 | 14.5 | ||

| 8th grade | 18 | 6.1 | 19 | 6.4 | ||

| 10th grade | 25 | 8.4 | 44 | 14.9 | ||

| 11th grade | 23 | 7.8 | 56 | 18.9 | ||

| Father's profession | Farmer | 45 | 45 | 33 | 17 | <0.001 |

| Breeder | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Public service worker | 22 | 22 | 74 | 38 | ||

| Taxi driver | 4 | 4 | 12 | 6 | ||

| Trader | 3 | 3 | 18 | 9 | ||

| Craftsman | 8 | 8 | 40 | 20 | ||

| Private service worker | 13 | 13 | 8 | 4 | ||

| Processor | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | ||

| No profession | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Mother’s profession | Farmer | 12 | 12.12 | 7 | 3.55 | <0.001 |

| Breeder | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.50 | ||

| Public service worker | 9 | 9.09 | 19 | 9.64 | ||

| Trader | 17 | 17.17 | 81 | 41.11 | ||

| Craftsman | 14 | 14.14 | 34 | 17.25 | ||

| Housewife | 42 | 42.42 | 50 | 25.38 | ||

| Private service worker | 1 | 1.01 | 1 | 0.50 | ||

| Processor | 1 | 1.01 | 0 | 0 | ||

| No profession | 3 | 3.03 | 4 | 2.03 | ||

| Ethnic group | Ditamari | 79 | 78.78 | 33 | 16.24 | <0.001 |

| Bariba | - | 29 | 14.21 | |||

| Peulhs | 1 | 1.01 | 2 | 1.01 | ||

| Waama | 2 | 2.02 | 27 | 13.19 | ||

| Fon | 3 | 3.03 | 18 | 9.13 | ||

| Nago | 1 | 1.01 | 4 | 2.03 | ||

| Others | 14 | 14.15 | 89 | 44.19 | ||

| Food type | Consumption frequency | Boukombe(n=101) | Natitingou(n=202) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | |||

| Fruit, not including juice | 2 or more times a day | 8.8 | 11.0 | 0.01 |

| Once a day | 12.8 | 20.0 | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 2.9 | 2.0 | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 13.8 | 17.5 | ||

| 1–3 times month | 2.9 | 11.0 | ||

| Less than once a month or never | 58.4 | 38.5 | ||

| Vegetables | 2 or more times a day | 9.9 | 11.44 | 0.12 |

| Once a day | 12.9 | 21.39 | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 1.9 | 3.5 | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 20.9 | 21.89 | ||

| 1–3 times month | 2.9 | 6.97 | ||

| Less than once a month or never | 51.5 | 34.82 | ||

| Fruits, not including juice | 2 or more times a day | 8.8 | 11.0 | 0.01 |

| Once a day | 12.8 | 20.0 | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 2.9 | 2.0 | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 13.8 | 17.5 | ||

| 1–3 times a month | 2.9 | 11.0 | ||

| Less than once a month or never | 58.4 | 38.5 | ||

| Vegetables | 2 or more times a day | 9.9 | 11.4 | 0.12 |

| Once a day | 12.9 | 21.4 | ||

| 5–6 times a week | 1.9 | 3.5 | ||

| 3–4 times a week | 20.9 | 21. 9 | ||

| 1–3 times a month | 2.9 | 7.0 | ||

| Less than once a month or never | 51.5 | 34.8 |

| p-value | p-value | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boukombe | Natitingou | ||||||

| SD (%) | NSD (%) | SD (%) | NSD (%) | ||||

| Number of different fruits consumed | 0.034 | ||||||

| 0 | 84.84 | 79.79 | 0.335 | 81.13 | 68,55 | 0.065 | |

| 1 | 13.13 | 16.16 | 13.70 | 26.28 | |||

| 2 | 2.02 | 4.04 | 4.06 | 4.12 | |||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.50 | 0.51 | |||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.50 | 0.51 | |||

| Number of different vegetables consumed | <0.01 | ||||||

| 0.24 | 0.65 | ||||||

| 0 | 6.06 | 4.04 | 5.07 | 3.09 | |||

| 1 | 15.15 | 12.12 | 8.12 | 8.76 | |||

| 2 | 33.33 | 28.28 | 18.27 | 18.55 | |||

| 3 | 20.20 | 26.26 | 17.76 | 19.58 | |||

| 4 | 10.10 | 15.15 | 20.81 | 16.49 | |||

| 5 | 9.09 | 8.08 | 13.19 | 13.91 | |||

| 6 | 6.06 | 5.05 | 5.58 | 9.27 | |||

| 7 | 0 | 1.01 | 6.59 | 4.12 | |||

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 4.06 | 3.09 | |||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.03 | |||

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.50 | 0 | |||

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.54 | |||

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.51 | |||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Estimate | Std. Error | Z value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School day | ||||

| (Intercept) | -0.91691 | 1.15945 | -0.791 | 0.43 |

| Age | -0.45641 | 0.22998 | -1.985 | 0.04 |

| Sex | 0.99633 | 0.36129 | 2.758 | 0.005 |

| Commune Natitingou | 0.44776 | 0.40890 | 1.096 | 0.27 |

| Student ethnicity | -0.02352 | 0.01624 | -1.449 | 0.14 |

| Father’s occupation | -0.02601 | 0.08333 | -0.312 | 0.75 |

| Mother’s occupation | 0.20452 | 0.09639 | 2.122 | 0.03 |

| Non-school day | ||||

| (Intercept) | -32.8 | 2140000 | 0.00 | 1.000 |

| Age | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.30 | 0.76 |

| Male | -0.33 | 0.26 | -1.27 | 0.20 |

| Commune Natitingou | -0.50 | 0.34 | -1.45 | 0.14 |

| Student ethnicity | 2.68 | 0.86 | 3.12 | 0.001 |

| Mother’s occupation | 2.73 | 1.32 | 2.06 | 0.039 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | Z value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.703 | 0.714 | 26.85 | <0.0001 |

| Age | 0.0110 | 0.0331 | 0.11 | 0.74 |

| Male | -0.0325 | 0.1868 | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Commune Boukombe | -09814 | 0.2612 | 14.11 | 0.0001 |

| Student ethnicity | ||||

| Berba | -1.9282 | 0.3350 | 33.14 | < 0.0001 |

| Biali | 1.6654 | 0.3733 | 19.90 | < 0.0001 |

| Cenoufo | -1.3389 | 0.4421 | 9.17 | 0.002 |

| Djema | -3.5776 | 0.7151 | 25.03 | < 0.0001 |

| Fodo | -2.6850 | 0.5683 | 22.32 | < 0.0001 |

| Goun | -1.0600 | 0.3734 | 8.06 | 0.004 |

| Kpabiye | -0.9735 | 0.4199 | 5.38 | 0.02 |

| Mahi | -0.9629 | 0.3362 | 8.20 | 0.004 |

| M’berme | 1.3184 | 0.3618 | 13.28 | 0.0002 |

| Peda | -2.1175 | 0.4188 | 25.56 | < 0.0001 |

| Xwla | 1.1950 | 0.57558 | 4.28 | 0.03 |

| Yom | 4.8455 | 0.3824 | 160.57 | < 0.0001 |

| Yora | -2.4539 | 0.4609 | 28.35 | < 0.0001 |

| Zeriman | 1.9821 | 0.4477 | 19.60 | < 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).