Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

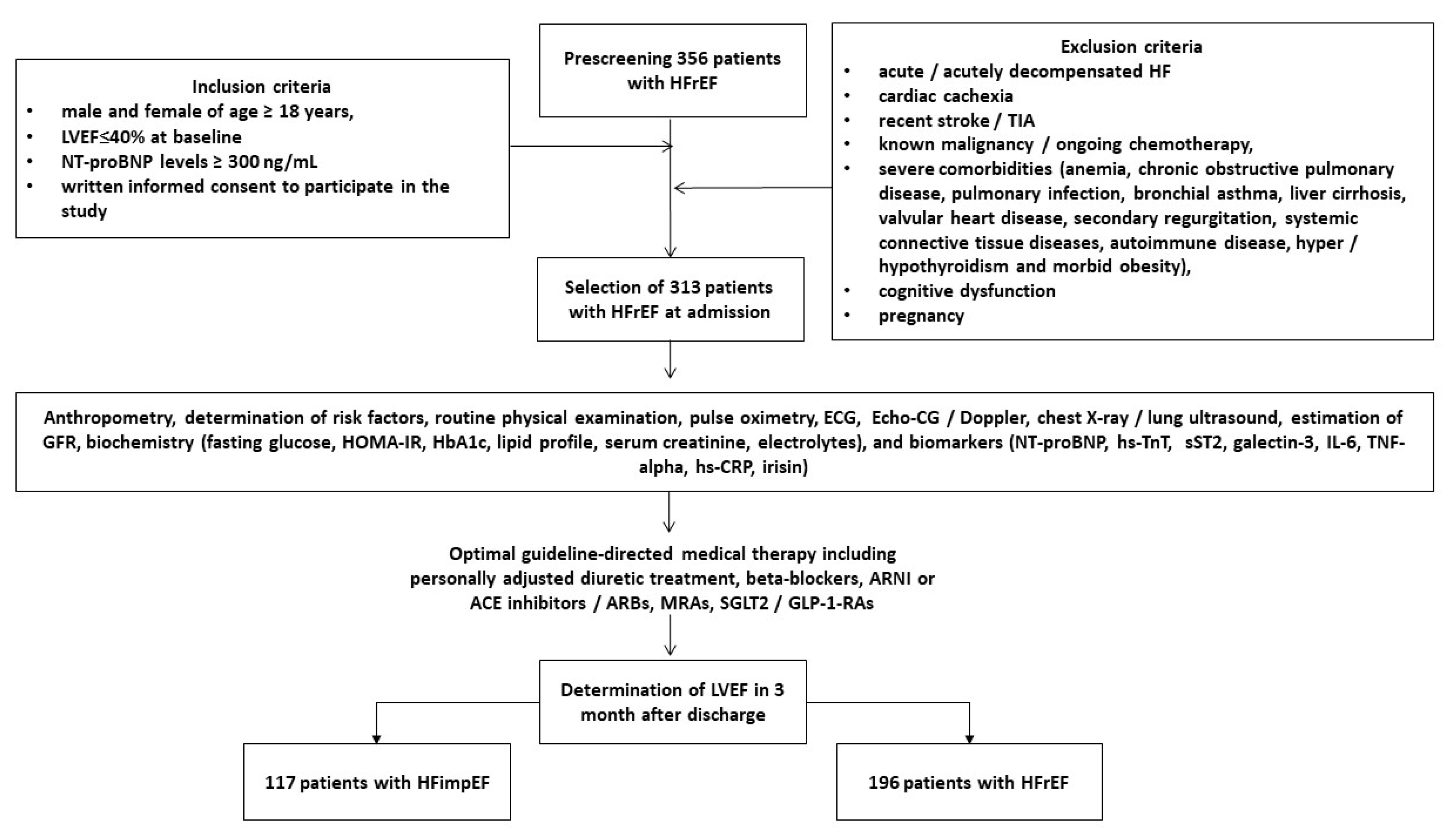

The role of irisin in predicting functional cardiac recovery in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) retains not fully understood. The aim of the study is to determine discriminative value of irisin for improved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in discharged patients with HFrEF. We included in the study 313 patients who were discharge with HFrEF (at admission LVEF < 40%) and followed them for 3 months. HF with improved EF (HFimpEF) was defined as an increase in LVEF of more than 40% on transthoracic B-mode echocardiography within 3 months of follow-up. All individuals gave their informed consent to participate in the study and obtained optimal guideline-based management. Serum concentrations of NT-proBNP, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), interleukin-6, galectine-3, soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 and irisin were determined using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. At 3rd months 117 (37.4%) patients had improved LVEF, whereas 196 individuals were categorized as having persistent HFrEF. The proportions of current stable coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease grade 1-3, and percutaneous coronary intervention history were significantly higher in patients with persistent HFrEF compared with HFimpEF. We found that HFimpEF was associated with lower left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, serum levels of NT-proBNP and higher left atrial volume index (LAVI), irisin concentrations than those with persistent HFrEF, whereas the levels of other biomarkers did not significantly differ between groups. The most balanced cut-off value of irisin and NT-proBNP (improved LVEF versus non-improved LVEF) were 10.8 ng/mL (area under curve [AUC] = 0.96, sensitivity = 81.0%, specificity = 88.0%; P = 0.0001) and 1540 pmol/L (AUC = 0.79; sensitivity = 73.1%, specificity 78.5%, p = 0.0001), respectively. Using multivariate comparative analysis we established that the irisin levels ≥ 10.8 ng/mL (odds ration [OR] = 1.73; P = 0.001) and NT-proBNP < 1540 pmol/mL (OR = 1.47; P = 0.001), LAVI < 39 mL/m2 (OR = 1.23; P = 0.001), atrial fibrillation (OR = 0.95; P = 0.010) independently predicted HFimpEF. The discriminative value of irisin ≥10.8 ng/mL was better than NT-proBNP <1540 pmol/mL, but the combined model (irisin added to NT-proBNP) did not improve the predictive modality of irisin alone. In conclusion, serum irisin ≥10.8 ng/mL predicted improved LVEF in patients with HFrEF independently of NT-proBNP.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

2.2. The Evaluation of Participants’ Demographics, Anthropometry Parameters and Concomitant Diseases / Conditions

2.3. Determination of HFimpEF

2.4. Echocardiography Examination

2.5. Glomerular Filtration Rate and Insulin Resistance Determination

2.6. Blood Sampling and Biomarker Analysis

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Basic Clinical Characteristics, Echocardiographic Parameters and Laboratory Findings

3.2. The Optimal Cut-Offs for Possible Predictors of HFimpEF: The Results of the ROC Curve Analysis

3.3. Predictive Factors for HFimpEF: Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Models

3.4. Comparison of the Predictive Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287, Erratum in: Cardiovasc Res. 2023, 119, 1453. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvad026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt B, Ahmad T, Alexander KM, Baker WL, Bosak K, Breathett K, Fonarow GC, Heidenreich P, Ho JE, Hsich E, Ibrahim NE, Jones LM, Khan SS, Khazanie P, Koelling T, Krumholz HM, Khush KK, Lee C, Morris AA, Page RL 2nd, Pandey A, Piano MR, Stehlik J, Stevenson LW, Teerlink JR, Vaduganathan M, Ziaeian B; Writing Committee Members. Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America. J Card Fail. 2023, 29, 1412–1451. [CrossRef]

- Emmons-Bell S, Johnson C, Roth G. Prevalence, incidence and survival of heart failure: a systematic review. Heart. 2022, 108, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denfeld QE, Winters-Stone K, Mudd JO, Gelow JM, Kurdi S, Lee CS. The prevalence of frailty in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017, 236, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Devore AD, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Heart Failure With Preserved, Borderline, and Reduced Ejection Fraction: 5-Year Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017, 70, 2476–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioncel O, Lainscak M, Seferovic PM, Anker SD, Crespo-Leiro MG, Harjola VP, Parissis J, Laroche C, Piepoli MF, Fonseca C, Mebazaa A, Lund L, Ambrosio GA, Coats AJ, Ferrari R, Ruschitzka F, Maggioni AP, Filippatos G. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell K, Kondo T, Talebi A, Teh K, Bachus E, de Boer RA, Campbell RT, Claggett B, Desai AS, Docherty KF, Hernandez AF, Inzucchi SE, Kosiborod MN, Lam CSP, Martinez F, Simpson J, Vaduganathan M, Jhund PS, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV. Prognostic Models for Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 457–465, Erratum in: JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 861. 10.1001/jamacardio.2024.2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pensa AV, Khan SS, Shah RV, Wilcox JE. Heart failure with improved ejection fraction: Beyond diagnosis to trajectory analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2024, 82, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabon MA, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Chatur S, Siqueira S, Marti-Castellote P, de Boer RA, Hernandez AF, Inzucchi SE, Kosiborod MN, Lam CSP, Martinez F, Shah SJ, Desai AS, Jhund PS, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. In-hospital course of patients with heart failure with improved ejection fraction in the DELIVER trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 2532–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park CS, Park JJ, Mebazaa A, Oh IY, Park HA, Cho HJ, Lee HY, Kim KH, Yoo BS, Kang SM, Baek SH, Jeon ES, Kim JJ, Cho MC, Chae SC, Oh BH, Choi DJ. Characteristics, Outcomes, and Treatment of Heart Failure With Improved Ejection Fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e011077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726, Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 4901. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licordari R, Correale M, Bonanno S, Beltrami M, Ciccarelli M, Micari A, Palazzuoli A, Dattilo G. Beyond Natriuretic Peptides: Unveiling the Power of Emerging Biomarkers in Heart Failure. Biomolecules. 2024, 14, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Figal DA, Hernández-Vicente A, Pastor-Pérez F, Martínez-Sellés M, Solé-González E, Alvarez-García J, García-Pavía P, Varela-Román A, Sánchez PL, Delgado JF, Noguera-Velasco JA, Bayes-Genis A; NICE study investigators. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide post-discharge monitoring in the management of patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction - a randomized trial: The NICE study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller C, McDonald K, de Boer RA, Maisel A, Cleland JGF, Kozhuharov N, Coats AJS, Metra M, Mebazaa A, Ruschitzka F, Lainscak M, Filippatos G, Seferovic PM, Meijers WC, Bayes-Genis A, Mueller T, Richards M, Januzzi JL Jr; Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology practical guidance on the use of natriuretic peptide concentrations. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciatti E, Merlo A, Scangiuzzi C, Limonta R, Gori M, D’Elia E, Aimo A, Vergaro G, Emdin M, Senni M. Prognostic Value of sST2 in Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023, 12, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girerd N, Cleland J, Anker SD, Byra W, Lam CSP, Lapolice D, Mehra MR, van Veldhuisen DJ, Bresso E, Lamiral Z, Greenberg B, Zannad F. Inflammation and remodeling pathways and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with ischemic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicori P, Zhang J, Cuthbert J, Urbinati A, Shah P, Kazmi S, Clark AL, Cleland JGF. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in chronic heart failure: patient characteristics, phenotypes, and mode of death. Cardiovasc Res. 2020, 116, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markousis-Mavrogenis G, Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Devalaraja M, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos GS, van der Harst P, Lang CC, Metra M, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, Zannad F, Zwinderman AH, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, Kakkar R, Voors AA, van der Meer P. The clinical significance of interleukin-6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT-CHF study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge FH, Omote K, Reddy YNV, Sorimachi H, Obokata M, Borlaug BA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in patients with normal natriuretic peptide levels is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43, 1941–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen YY, Liang L, Tian PC, Feng JY, Huang LY, Huang BP, Zhao XM, Wu YH, Wang J, Guan JY, Li XQ, Zhang J, Zhang YH. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and low NT-proBNP levels. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023, 102, e36351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy SP, Kakkar R, McCarthy CP, Januzzi JL Jr. Inflammation in Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1324–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocco G, Jerie P, Amiet P, Pandolfi S. Inflammation in Heart Failure: known knowns and unknown unknowns. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017, 18, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berezin AE, Berezin AA. Point-of-care heart failure platform: where are we now and where are we going to? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2022, 20, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Cui F, Ning K, Wang Z, Fu P, Wang D, Xu H. Role of irisin in physiology and pathology. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 962968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa RAL. Exercise-produced irisin effects on brain-related pathological conditions. Metab Brain Dis. 2024, 39, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He X, Hua Y, Li Q, Zhu W, Pan Y, Yang Y, Li X, Wu M, Wang J, Gan X. FNDC5/irisin facilitates muscle-adipose-bone connectivity through ubiquitination-dependent activation of runt-related transcriptional factors RUNX1/2. J Biol Chem. 2022, 298, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann T, Elbelt U, Stengel A. Irisin as a muscle-derived hormone stimulating thermogenesis--a critical update. Peptides. 2014, 54, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello L, Pitrone M, Guarnotta V, Giordano C, Pizzolanti G. Irisin: A Possible Marker of Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho MY, Wang CY. Role of Irisin in Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure, and Cardiac Hypertrophy. Cells. 2021, 10, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang YJ, Zhang Z, Yan T, Chen K, Xu GF, Xiong SQ, Wu DQ, Chen J, Jose PA, Zeng CY, Fu JJ. Irisin attenuates type 1 diabetic cardiomyopathy by anti-ferroptosis via SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of p53. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024, 23, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Hu C, Kong CY, Song P, Wu HM, Xu SC, Yuan YP, Deng W, Ma ZG, Tang QZ. FNDC5 alleviates oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activating AKT. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li RL, Wu SS, Wu Y, Wang XX, Chen HY, Xin JJ, Li H, Lan J, Xue KY, Li X, Zhuo CL, Cai YY, He JH, Zhang HY, Tang CS, Wang W, Jiang W. Irisin alleviates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy by inducing protective autophagy via mTOR-independent activation of the AMPK-ULK1 pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018, 121, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo W, Zhang B, Wang X. Lower irisin levels in coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Minerva Endocrinol. 2020, 45, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk D, Melekoglu A, Altinbilek E, Calik M, Kosem A, Kilci H, Misirlioglu NF, Uzun H. Association Between Serum Irisin Levels and ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Int J Gen Med. 2023, 16, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou Q, Song R, Zhao X, Yang C, Feng Y. Lower circulating irisin levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with chronic complications: A meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e21859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang PX, Fan ZJ, Wu LY, Wang SY, Zhang JL, Dong XT, Zhang AH. Serum irisin levels are negatively associated with blood pressure in dialysis patients. Hypertens Res. 2023, 46, 2738–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz Kopuz TN, Dagdeviren M, Fisunoglu M. Serum irisin levels in newly diagnosed type-II diabetic patients: No association with the overall diet quality but strong association with fruit intake. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022, 49, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen X, Chen Y, Zhang J, Yang M, Huang L, Luo J, Xu L. The association between circulating irisin levels and osteoporosis in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024, 15, 1388717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin AE, Berezin AA. Biomarkers in Heart Failure: From Research to Clinical Practice. Ann Lab Med. 2023, 43, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Rahko, P.S.; Blauwet, L.A.; Canaday, B.; Finstuen, J.A.; Foster, M.C.; Horton, K.; Ogunyankin, K.O.; Palma, R.A.; Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2018, 32, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F., 3rd; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A New Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and ? -cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He Y, Ling Y, Guo W, Li Q, Yu S, Huang H, Zhang R, Gong Z, Liu J, Mo L, Yi S, Lai D, Yao Y, Liu J, Chen J, Liu Y, Chen S. Prevalence and Prognosis of HFimpEF Developed From Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 8, 757596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu N, Lang X, Zhang Y, Zhao B, Zhang Y. Predictors and Prognostic Factors of Heart Failure with Improved Ejection Fraction. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2024, 25, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho LT, Juang JJ, Chen YH, Chen YS, Hsu RB, Huang CC, Lee CM, Chien KL. Predictors of Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Improvement in Patients with Early-Stage Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2023, 39, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardeny O, Desai AS, Jhund PS, Fang JC, Claggett B, de Boer RA, Hernandez AF, Inzucchi SE, Kosiborod MN, Lam CSP, Martinez FA, Shah SJ, Mc Causland FR, Petrie MC, Vaduganathan M, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Dapagliflozin and Mode of Death in Heart Failure With Improved Ejection Fraction: A Post Hoc Analysis of the DELIVER Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid CM, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, Anker SD, Atherton J, Böhm M, Butler J, Drazner MH, Michael Felker G, Filippatos G, Fiuzat M, Fonarow GC, Gomez-Mesa JE, Heidenreich P, Imamura T, Jankowska EA, Januzzi J, Khazanie P, Kinugawa K, Lam CSP, Matsue Y, Metra M, Ohtani T, Francesco Piepoli M, Ponikowski P, Rosano GMC, Sakata Y, Seferović P, Starling RC, Teerlink JR, Vardeny O, Yamamoto K, Yancy C, Zhang J, Zieroth S. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 352–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang W, Nurhafizah A, Frederich A, Khairunnisa AR, Kezia C, Fathoni MI, Samban S, Flindy S. Risk and Protective Factors of Poor Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure with Improved Ejection Fraction Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2025, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintér A, Behon A, Veres B, Merkel ED, Schwertner WR, Kuthi LK, Masszi R, Lakatos BK, Kovács A, Becker D, Merkely B, Kosztin A. The Prognostic Value of Anemia in Patients with Preserved, Mildly Reduced and Recovered Ejection Fraction. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022, 12, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo T, Campbell R, Jhund PS, Anand IS, Carson PE, Lam CSP, Shah SJ, Vaduganathan M, Zannad F, Zile MR, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV. Low Natriuretic Peptide Levels and Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2024, 12, 1442–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezina TA, Berezin OO, Novikov EV, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Irisin Predicts Poor Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Low Levels of N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide. Biomolecules. 2024, 14, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li J, Xie S, Guo L, Jiang J, Chen H. Irisin: linking metabolism with heart failure. Am J Transl Res. 2020, 12, 6003–6014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang Z, Chen K, Han Y, Zhu H, Zhou X, Tan T, Zeng J, Zhang J, Liu Y, Li Y, Yao Y, Yi J, He D, Zhou J, Ma J, Zeng C. Irisin Protects Heart Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Through a SOD2-Dependent Mitochondria Mechanism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2018, 72, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrini A, Bruno C, Vergani E, Venuti A, Favuzzi AMR, Guidi F, Nicolotti N, Meucci E, Mordente A, Mancini A. Circulating irisin levels in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: A pilot study. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0210320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin AA, Lichtenauer M, Boxhammer E, Stöhr E, Berezin AE. Discriminative Value of Serum Irisin in Prediction of Heart Failure with Different Phenotypes among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cells. 2022, 11, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin AA, Fushtey IM, Pavlov SV, Berezin AE. Predictive value of serum irisin for chronic heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Biomed. 2022, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar M, Irfan U, Abdelkhalek A, Javed I, Khokhar MI, Shakil F, Raza S, Salim SS, Altaf MM, Habib R, Ahmed S, Ahmed F. Comprehensive Quality Analysis of Conventional and Novel Biomarkers in Diagnosing and Predicting Prognosis of Coronary Artery Disease, Acute Coronary Syndrome, and Heart Failure, a Comprehensive Literature Review. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2024, 17, 1258–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Entire HF patient cohort (n = 313) |

Patients with HFimpEF (n = 117) |

Patients with HFrEF (n = 196) |

P value between cohorts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and anthropometry parameters | ||||

| Age, year | 69 (61–78) | 67 (60–75) | 70 (62–81) | 0.146 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 184 (58.9) | 68 (58.1) | 116 (59.2) | 0.146 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.2 ± 4.26 | 25.3 ±3.88 | 26.9 ± 3.97 | 0.272 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 101 ± 7 | 99 ± 5 | 101 ± 8 | 0.690 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Smoking history, n (%) | 135 (43.1) | 48 (41.0) | 87 (44.4) | 0.642 |

| Abdominal obesity, n (%) | 75 (24.0) | 27 (23.1) | 48 (24.5) | 0.475 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 234 (74.8) | 86 (73.5) | 148 (75.5) | 0.344 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 176 (56.2) | 66 (56.4) | 110 (56.1) | 0.871 |

| Stable CAD, n (%) | 162 (51.8) | 57 (48.7) | 105 (53.6) | 0.046 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 57 (18.2) | 20 (17.1) | 37 (18.9) | 0.242 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 93 (29.7) | 28 (23.9) | 65 (33.2) | 0.048 |

| LVH, n (%) | 217 (69.3) | 81 (69.2) | 136 (69.4) | 0.844 |

| CKD 1–3 grades, n (%) | 68 (21.7) | 22 (18.8) | 46 (23.5) | 0.044 |

| T2DM, n (%) | 102 (32.6) | 38 (32.5) | 64 (32.7) | 0.526 |

| PCI history, n (%) | 97 (31.0) | 42 (35.9) | 55 (28.1) | 0.048 |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | ||||

| II | 72 (23.0) | 29 (24.8) | 43 (21.9) | 0.142 |

| III | 184 (58.9) | 69 (59.0) | 115 (58.7) | 0.416 |

| IV | 57 (18.1) | 19 (16.2) | 38 (19.4) | 0.144 |

| Hemodynamic and echocardiographic parameters | ||||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 127 ± 8 | 129 ± 8 | 126 ± 9 | 0.395 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 68 ± 9 | 69 ± 7 | 68 ± 7 | 0.462 |

| LVEDV, mL | 176 (154–197) | 178 (155–201) | 173 (149–193) | 0.274 |

| LVESV, mL | 103 (98–106) | 99 (95–103) | 110 (97–119) | 0.022 |

| LVEF, % | 41 (34–51) | 44 (40–47) | 37 (33–39) | 0.024 |

| LVMI, g/m2 | 148 ± 22 | 147 ± 19 | 155 ± 20 | 0.226 |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 44 (35–54) | 42 (36–49) | 47 (40–53) | 0.046 |

| TAPSE, mm | 20 (15-26) | 19 (14-24) | 22 (15-27) | 0.611 |

| E/e`, unit | 17 ± 7 | 16 ± 4 | 17 ± 5 | 0.355 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Baseline eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 64 ± 19 | 65 ± 15 | 61 ± 13 | 0.331 |

| K, mmol/L | 4.1 (3.3-5.3) | 4.3 (3.4-5.5) | 4.0 (3.1-5.10) | 0.124 |

| Na, mmol/L | 139 (128-146) | 139 (125-149) | 137 (127-145) | 0.846 |

| HOMA-IR, units | 5.11 ± 2.33 | 5.05 ± 2.23 | 5.19± 2.25 | 0.658 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 4.68 ± 0.57 | 4.59 ± 0.52 | 4.70 ± 0.51 | 0.681 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.10 ± 1.99 | 5.07 ± 1.65 | 5.11± 1.57 | 0.560 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 13.9 (12.6–15.1) | 13.8 (12.5-14.7) | 14.0 (12.6-15.3) | 0.674 |

| Haematocrit, % | 38 (34–42) | 38 (35-40) | 39 (35–43) | 0.644 |

| Baseline creatinine, µmol/L | 104 ± 10 | 97 ± 11 | 106 ± 9 | 0.128 |

| Serum uric acid, µmol/L | 359 ± 85 | 352 ± 80 | 360 ± 88 | 0.672 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.69 ± 0.60 | 5.61 ± 0.68 | 5.73 ± 0.66 | 0.654 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 1.03 ± 0.09 | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 0.748 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 3.60± 0.20 | 3.50 ± 0.18 | 3.60± 0.20 | 0.786 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 2.34 ± 0.37 | 2.30 ± 0.29 | 2.41 ± 0.27 | 0.650 |

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 5.98 (2.24–9.70) | 5.52 (2.12–8.16) | 6.11 (2.80–10.56) | 0.860 |

| TNF-alpha, pg/mL | 3.68 (2.10–5.23) | 3.45 (2.03–4.94) | 3.81 (2.19–5.21) | 0.547 |

| IL-6, ng/mL | 2.91 (0.76–4.95) | 2.70 (0.67–4.82) | 3.20 (0.88–5.61) | 0.216 |

| cTnT, ng/mL | 0.036 (0.004-0.112) | 0.021 (0.001-0.110) | 0.048 (0.003-0.120) | 0.690 |

| NT-proBNP, pmol/mL | 1810 (980–2560) | 1330 (870–1580) | 2310 (1130–3580) | 0.044 |

| sST2, ng/mL | 29.40 (13.90-45.70) | 27.63 (11.17–41.80) | 31.90 (15.82-47.54) | 0.844 |

| Galectin-3, ng/mL | 27.5 (11.6 – 53.4) | 24.1 (9.8 – 41.5) | 32.7 (10.1 – 60.3) | 0.671 |

| Irisin, ng/mL | 5.75 (2.18–9.12) | 8.23 (4.26–13.50) | 4.37 (1.62–7.17) | 0.001 |

| Concomitant medications and devises | ||||

| ACE inhibitors, n (%) | 122 (39.0) | 43 (36.8) | 79 (40.3) | 0.519 |

| ARBs, n (%) | 39 (12.5) | 20 (17.1) | 19 (9.7) | 0.050 |

| ARNI, n (%) | 152 (48.7) | 54 (46.2) | 98 (50.0) | 0.538 |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 285 (91.1) | 105 (89.7) | 180 (91.8) | 0.351 |

| Ivabradine, n (%) | 32(10.2) | 10 (8.5) | 22 (11.2) | 0.271 |

| CCBs, n (%) | 35 (11.2) | 11 (9.4) | 24 (12.2) | 0.164 |

| MRA, n (%) | 231 (73.8) | 86 (73.5) | 145 (74.0) | 0.834 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 298 (98.2) | 112 (95.7) | 186 (94.9) | 0.877 |

| Antiplatelet agents, n (%) | 179 (57.2) | 69 (59.0) | 110 (56.1) | 0.048 |

| Anticoagulants, n (%) | 93 (29.7) | 28 (23.9) | 65 (33.2) | 0.048 |

| Metformin, n (%) | 97 (31.0) | 36 (30.8) | 61 (31.1) | 0.713 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors, n (%) | 227 (72.5) | 86 (73.5) | 141 (71.9) | 0.637 |

| GLP-1-RAs, n (%) | 34 (10.8) | 13 (11.1) | 21 (10.7) | 0.511 |

| Statins, n (%) | 234 (74.8) | 86 (73.5) | 148 (75.5) | 0.344 |

| RCT, n (%) | 22 (7.0) | 9 (7.7) | 13 (6.6) | 0.766 |

| Variables | AUC | 95% CI | P value | Cut-offs | Se, % | Sp,% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAVI | 0.721 | 0.680 – 0.773 | 0.001 | 39 mL/m2 | 73.9 | 77.1 |

| E/e` | 0.667 | 0.615 – 0.718 | 0.001 | 17 | 63.6 | 70.2 |

| hs-CRP | 0.744 | 0.712 – 0.779 | 0.001 | 6.1 mg/L | 72.3 | 75.4 |

| TNF-alpha | 0.602 | 0.543 – 0.665 | 0.048 | 3.7 pg/mL | 62.4 | 61.8 |

| NT-proBNP | 0.855 | 0.811 – 0.892 | 0.0001 | 1540 pmol/mL | 79.0 | 73.1 |

| sST2 | 0.768 | 0.733 – 0.795 | 0.001 | 31 ng/mL | 72.6 | 70.4 |

| Galectin-3 | 0.741 | 0.708 – 0.795 | 0.001 | 28 ng/mL | 73.5 | 78.1 |

| Irisin | 0.960 | 0.910 – 0.988 | 0.0001 | 10.8 ng/mL | 81.0 | 88.0 |

| Predictive factors | Univariate log regression | Multivariate log regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| T2DM (presence vs absent) | 0.97 (0.91–1.02) | 0.212 | - | |

| PCI history (presence vs absent) | 0.95 (0.89–1.13) | 0.437 | - | |

| AF (presence vs absent) | 0.95 (0.91–0.98) | 0.010 | 0.95 (0.90–0.98) | 0.010 |

| Stable CAD (presence vs. absent) | 1.02 (0.94–1.17) | 0.380 | - | |

| CKD stages 1–3 (presence vs. absent) | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) | 0.048 | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) | 0.177 |

| Dilated CMP (presence vs absent) | 0.96 (0.92–1.02) | 0.422 | - | |

| LAVI < 39 mL/m2 vs. ≥39 mL/m2 | 1.32 (1.15–1.56) | 0.001 | 1.23 (1.11–1.39) | 0.001 |

| E/e`<17 vs. ≥17 | 1.18 (1.04–1.35) | 0.012 | 1.10 (1.00–1.27) | 0.052 |

| hs-CRP <6.1 mg/L vs. ≥6.1 mg/L | 1.12 (1.06–1.20) | 0.018 | 1.09 (1.00–1.20) | 0.120 |

| TNF-alpha <3.7 bg/mL vs. ≥3.7 ng/mL | 1.06 (1.01 – 1.12) | 0.044 | 1.05 (0.99 – 1.10) | 0.206 |

| NT-proBNP <1540 vs. ≥ 1540 pmol/mL | 1.56 (1.12–2.15) | 0.001 | 1.47 (1.11–2.12) | 0.001 |

| sST2 <31 ng/mL vs. ≥31 ng/mL | 1.24 (1.02–1.65) | 0.048 | 1.20 (1.00–1.68) | 0.086 |

| Galectin-3 <28 ng/mL vs. ≥28 ng/mL | 1.17 (1.01–1.43) | 0.050 | 1.12 (1.00–1.27) | 0.064 |

| Irisin ≥ 10.8 ng/mL vs.<10.8 ng/mL | 1.75 (1.22–4.32) | 0.001 | 1.73 (1.16–4.18) | 0.001 |

| Predictive Models | Dependent Variable: AKI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | NRI | IDI | ||||

| M (95% CI) | p value | M (95% CI) | p value | M (95% CI) | p value | |

| Model 1 (NT-proBNP<1540 pmol/mL) | 0.855 (0.811 – 0.892) | - | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Model 2 (a presence of AF) | 0.820 (0.715 – 0.944) | 0.427 | 0.10 (0.06–0.15) | 0.388 | 0.11 (0.05–0.17) | 0.481 |

| Model 3 (LAVI <39 mL/m2) | 0.721 (0.680 – 0.773) | 0.044 | 0.03 (0.01–0.06) | 0.642 | 0.06 (0.02–0.09) | 0.552 |

| Model 4 (irisin≥10.8 ng/mL) | 0.960 (0.910 – 0.988) | 0.001 | 0.36 (0.24–0.49) | 0.001 | 0.44 (0.38–0.52) | 0.001 |

| Model 1+ Model 2 | 0.848 (0.790 – 0.910) | 0.066 | 0.10 (0.05–0.17) | 0.249 | 0.12(0.06–0.19) | 0.265 |

| Model 1+ Model 3 | 0.851 (0.810 – 0.912) | 0.270 | 0.09 (0.03–0.15) | 0.338 | 0.11 (0.03-0.17) | 0.286 |

| Model 1+ Model 4 | 0.979 (0.932 – 0.982) | 0.001 | 0.38 (0.29–0.50) | 0.001 | 0.44 (0.35–0.54) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).