1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the high prevalent arrhythmia in patients with heart failure (HF) that links adverse cardiac remodeling with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) death, stroke, peripheral embolism and HF decompensation [

1]. The pooled prevalence of AF in the inpatients with acutely decompensated HF with reduced (HFrEF) and preserved (HFpEF) ejection fraction was 34.4% and 42.8%, respectively [

2]. Along with it, AF was detected in about 20% outpatients with HFrEF and 33% those with HFpEF [

2]. To note, the prevalence rate of AF in patients with HFpEF may reach 60% [

3].

Moreover, AF and HF are not only coexist, but also can be plausible triggers for progressing electrical and structural atrial remodeling acting through the overlap of several pre-disposing factors, such as conventional CV risk factors (hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, older age), established cardiac diseases (coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathies, valvular heart disease) and signature of comorbidities including type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, overweigh / obesity [

3,

4]. Despite the nature of atrial remodeling in AF patients with HFpEF differs from that of HFrEF, left atrial myopathy is closely associated with cardiac fibrosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, neurohormonal activation and leads to progression of both of these conditions [

4]. It has been suggested that a disproportionate prevalence of myocardial ischemia, loss of cardiac myocytes, exaggerated accumulation of the extracellular matrix in atrial tissue in HFrEF when compared with HFpEF potentiates a more rapid progression of left atrial (LA) myopathy than left ventricular (LV) dysfunction [

5]. In contrast, hypertension, metabolic comorbidities (overweight/obesity, diabetes), age-associated disorders may intervene in left atrial structure and function before an occurrence of clinical signs / symptoms of HFpEF [

6]. In fact, AF is considered a powerful trigger for progression of adverse cardiac remodeling and clinical manifestation of HFpEF regardless of the presentation of other risk factors and concomitant diseases. To best of our knowledge, guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) can prevent new cases of AF and the progression of atrial myopathy in patients with HF, however, AF can interfere with the efficacy of some components of GDMT for HFpEF [

7,

8,

9]. As a result, identifying modifiable risk factors for AF may play a significant role in suitable preventive approach to detecting vulnerable patients with HFpEF [

10].

Myocardium in HFpEF presents decreased respiratory function and increased reactive oxygen species production, which is considered as mitochondrial dysfunction [

11], in close relation with exerkine, hepatokine and adipocytokine dysfunction, mitophagy abnormality, progenitor cell alteration that directly participate in dynamic nature of metabolic adaptation to disease progression [

12,

13,

14]. Moreover, several phenotypes of all myocardial cells (cardiac myocytes, cardiac progenitor cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, etc.), which are responsible for microvascular inflammation, abnormal vasoreactivity, cardiac hypertrophy and extracellular cardiac matrix accumulation/degradation, are closely regulated not only auto/paracrine factors, but also a large spectrum of cytokines and chemokines produced by skeletal myocytes, adipocytes, hepatocytes and kidney [

15,

16].

Adropin is a secreted multifunctional peptide that is responsible for metabolic flexibility and optimizing substrate utilization patterns in numerous physiological and pathological conditions [

17]. Adropin expression is markedly regulated by various factors, including fat-reached diet, liver X receptor alpha, estrogen receptor alpha, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor, regulator of reprogramming, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 expression by inhibiting sirtuin-1 and STAT3. Adropin was found to be expressed in various tissues, including the myocardium, skeletal muscles, adipose tissue, kidney, gastrointestinal tract and brain [

17,

18,

19].

Adropin is involved in regulating glucose and lipid homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, adipogenesis, the inflammatory response, and immune reactions by modulating multiple signaling pathways (e.g. c-Jun N-terminal kinase [JNK], cAMP activated protein kinase A, activation of the glucose transporter protein and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, Nrf2/HO-1, Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor [VEGFR]-2/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT and VEGFR/ c-Src/ERK1/2 signaling, expressing antioxidant enzymes and Bcl-2 / Bax proteins). It also alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress responses by reducing the phosphorylation of the inositol trisphosphate receptor in target cells [

20,

21]. Moreover, adropin acting through JNK may inhibit transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-induced fibroblast activation and fibrotic tissue remodeling and promotes tissue protection [

22]. Other cardiovascular effects of adropin include the regulation of arterial stiffness and vasodilation via endothelium-derived nitric oxide bioavailability, reducing cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, enhancing diastolic function, anti-ischemic, anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects, mediating cardiac cells survival [

23,

24,

25,

26]. On contrary, a deficiency of adropin can disrupt the function of immune cells and inflammatory pathways, thereby impairing the regulatory capacity of the immune system and promoting systemic, microvascular and adipose tissue inflammation.

Previous clinical studies have revealed that circulating adropin levels were lower in patients with cardiovascular (atherosclerosis, acute myocardial infarction, acute and chronic HF, cardiac cachexia, stroke) and non-cardiovascular (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, acute and chronic kidney diseases, overweight / obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus) diseases [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. For patients with HF regardless of its phenotypes, circulating levels of adropin were inversely correlated with HF severity [

33,

34]. Along with it, low levels of adropin are likely to be an independent predictor for occurrence of HF, kidney injury and diabetes mellitus, as well as to be the biomarker of poor clinical outcomes including cardiovascular death, HF-related hospitalization and diabetes-induced kidney disease [

33,

34,

35,

36]. However, the discriminative potency of adropin for AF in individuals with HFpEF remains unclear and requires face-to-face comparison with conventionally used and promising biomarkers, such as natriuretic peptides, cardiac troponins, soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 and galectin-3. The aim of the study is a) to investigation the possible discriminative value of adropin for new onset AF in patients with HFpEF who are being treated in accordance with conventional guideline and b) to compare it with predictive potencies of conventionally used predictors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

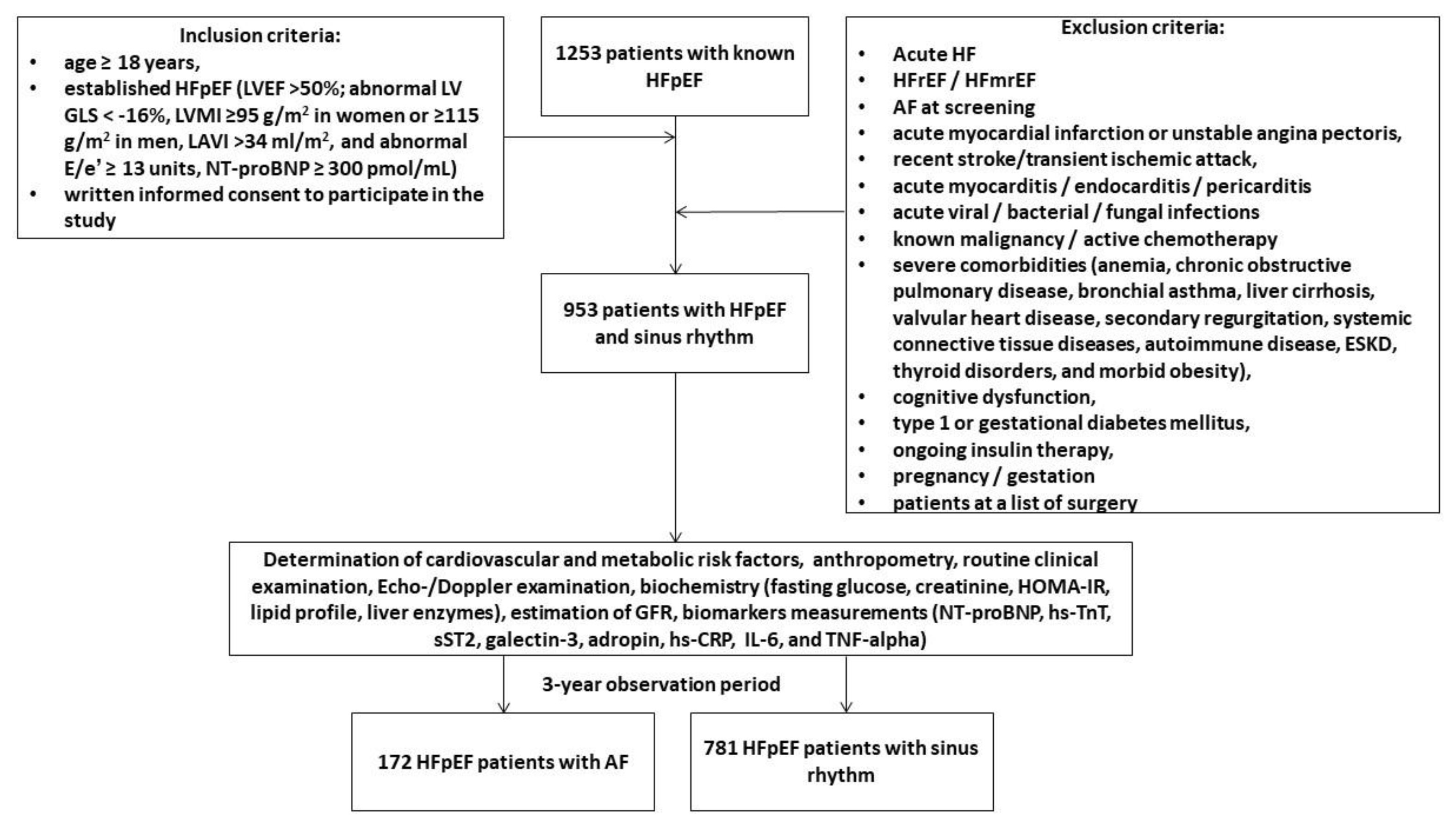

We pre-screened 1253 adult patients with HFpEF in our local database according to the conventional criteria: left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) >50%; abnormal LV global longitudinal strain (GLS) < -16%, LV myocardial mass index (MMI) ≥95 g/m

2 in women or ≥115 g/m

2 in men, left atrial volume index (LAVI) >34 mL/m

2, and abnormal diastolic index E/e’ ≥ 13 units, N-terminal natriuretic pro-peptide (NT-proBNP) ≥ 300 pmol/mL [

37]. Finally, between October 2020 and August 2022 were prospectively enrolled 953 outpatients with hemodynamically stable HFpEF and a presence of sinus rhythm on ECG and without a previous history of AF in the following medical centers: the private hospital Vita-Centre (Zaporozhye, Ukraine), EliteMedService (Zaporozhye, Ukraine), City Hospital #7 (Zaporozhye, Ukraine) and the private hospital “MIRUM clinic” (Kyiv, Ukraine). All patients continued to receive optimal GDMT and provided voluntary written informed consent to participate in the study (

Figure 1). The major exclusion criteria were acute HF, HFrEF, HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, recent stroke / transient ischemic attack, acute viral and bacterial infection, known malignancy, active chemotherapy, with severe comorbidities, including end stage renal disease (ESRD), cognitive dysfunction/dementia, pregnancy/gestation. We followed patients for 3 years and divided them into two cohorts depending on the presence of AF: 172 patients exhibited AF, whereas 781 individuals preserved sinus rhythm on ECG.

2.2. Determination of AF and Follow-Up

We determined 3-year cases of any forms of AF according to 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of AF [

38]. To detect AF we utilized ECG at rest, continuous 72-h ECG monitoring (when needed), direct interview with patients and /or their relatives, contact with general practitioners, review of databases, and discharge reports. The following had to be present for a case of AF to be verified: an absence of distinct repeating P waves on an ECG; irregular atrial activations; and irregular R-R intervals. The patient-centered management of AF involved individualizing treatment strategies according to the conventional approach [

39]. CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores were utilized to assess the risk of thromboembolism and bleeding and provide anticoagulation in patients with HFpEF after AF verification. Follow-up data were collected via clinic visits at baseline and during 3 years after the baseline with 3-month intervals.

2.3. Echocardiography Examination

In the study, all patients underwent a routine transthoracic B-mode and Doppler ultrasound examination. This was provided by an experienced echocardiographer using a GE Healthcare Vivid E95 scanner in apical 2- and 4-chamber views (General Electric Company, Horton, Norway). The conventional hemodynamic parameters included LVEF by using Simpson’s method, the LV end-diastolic (LVEDV) and end-systolic (LVESV) volumes, the left atrial volume index (LAVI), early diastolic blood filling (E), and the mean longitudinal strain ratio (e‘) were evaluated according to 2018 Guideline of the American Society of Echocardiography [

40]. The estimated E/e' ratio was expressed as the ratio of the E-wave velocity to the average of the medial and lateral e' velocities. After acquisition of high-quality echocardiographic data during at least three cardiac cycles, LV GLS was obtained by 2D speckle-tracking image analysis. We stored the data in the DICOM format for subsequent analysis. Left ventricular hypertrophy was defined as an LVMMI of ≥95 g/m² in women and ≥115 g/m² in men [

40].

2.4. Blood Sampling

Blood samples were obtained from all participants in fasting condition and collected in BD Vacutainer Serum Plus Tube. The samples were stored for 30 minutes at room temperature to clot. After clotting, the samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature. Samples with hemolysis were not used for further evaluation. The supernatant was collected and stored at -70°C until analysis at certified laboratory of the Vita Centre (Zaporozhye, Ukraine).

2.5. Biomarkers Assessment

The local Vita Centre laboratory in Zaporozhye, Ukraine, used a Roche P800 analyzer from Basel, Switzerland, to determine conventional hematological and biochemical parameters. The following data were recorded: blood routine indices, electrolytes, liver enzymes, glucose, serum uric acid, serum creatinine and lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein [HDL-C] and low-density lipoprotein [LDL-C] cholesterol). Concentrations of circulating biomarkers (N-terminal natriuretic pro-peptide [NT-proBNP], high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T [hs-TrT], soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 [sST2], galectin-3, tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α], high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP], and IL-6) were measured in serum using ELISA kits (Elabscience, Houston, Texas, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Adropin levels were measured with ELISA kit produced by Antibodies.com (Stockholm, Sweden). The data obtained from the ELISA analysis were subjected to standard curve-based evaluation. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate and the mean value was used for the final analysis. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation for each marker were both below 10%.

2.7. Glomerular Filtration Rate Estimation

The CKD-EPI formula was utilized to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [

41].

2.8. Determination of Insulin Resistance

The Homeostatic Assessment Model of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) was performed to assess insulin resistance [

42].

2.9. Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 11.0 for Windows and Graph Pad Prism, version 9 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. All continues variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation [SD] median and interquartile range [IQR] depending on whether the data were normally distributed, whereas categorical variables were presented as number (n) and percentage (%). Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) was utilized for correlations between hemodynamic parameters, comorbidities and biomarkers including the levels of adropin. We utilised the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to calculate the false discovery rate-adjusted P-value for each pair of variables. The chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. To compare the data between the two groups, an independent samples t-test was used if the variances were homogeneous and a Mann–Whitney U test was used if they were not. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to calculate the cutoff values for variables in predicting AF. Youden's index (sensitivity + specificity - 1) was used to determine the optimal cut-off value for each possible predictor. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were employed to investigate the prognostic factors for AF. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported for each predictor variable. We compared the incremental prognostic capacity of models on using a binary prediction methodology based on the estimation of integrated discrimination indices (IDI) and net reclassification improvement (NRI). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to suggest a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Clinical Characteristics

A total of 953 patients with HFpEF, New York Heart Association class II (n = 385) / III (n = 568) and were enrolled in the study and divided into two cohorts depending on a presence of new onset AF (n=172) or sinus rhythm on ECG (n=781) during 3 years. The clinical characteristics of patients outlined in

Table 1.

The entire group of patients had a mean age of 69 years and 52.2% of them were male. The profile of comorbidity conditions included dyslipidemia (62.2%), hypertension (87.9%), stable coronary artery disease (36.0%), smoking (35.2%), abdominal obesity (29.2%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (37.4%), left ventricular hypertrophy (70.9%), and chronic kidney disease 1-3 stages (26.3%). Therefore, all patients were hemodynamically stable, had a mean systolic / diastolic blood pressure of 143 / 87 mm Hg, a mean LVEF of 54%, an average of LAVI of 38 mL/m2, a mean of GLS of -15.9%. The therapy of HFpEF were personally optimized and included antagonists of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin-II receptor blockers or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors), beta-blockers, diuretics, sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor and other concomitant medications depending on the presence of comorbidities and diseases.

Patients from AF cohort were older, more likely to have type 2 diabetes mellitus and CKD stages 1-3, higher LAVI, concentrations of hs-CRP, NT-proBNP, sST2 and lower adropin levels than those with sinus rhythm on ECG. The patients with HFpEF from the cohort with sinus rhythm on ECG tended to treat frequently with angiotensin-II receptor blockers, beta-blockers, and SGLT2 inhibitors when compared with those who had AF.

We did not find significant differences between the two patients cohorts with respect to gender, body mass index, anthropometric parameters, the presence of dyslipidemia, hypertension, stable coronary artery disease, smoking, abdominal obesity, left ventricular hypertrophy, New York Heart Association classes, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, LVEF, LVMMI, E/e`, GLS, eGFR, lipid profile, glucose levels, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, and concentrations of TNF-alpha, galectin-3, IL-6, and hs-TrT.

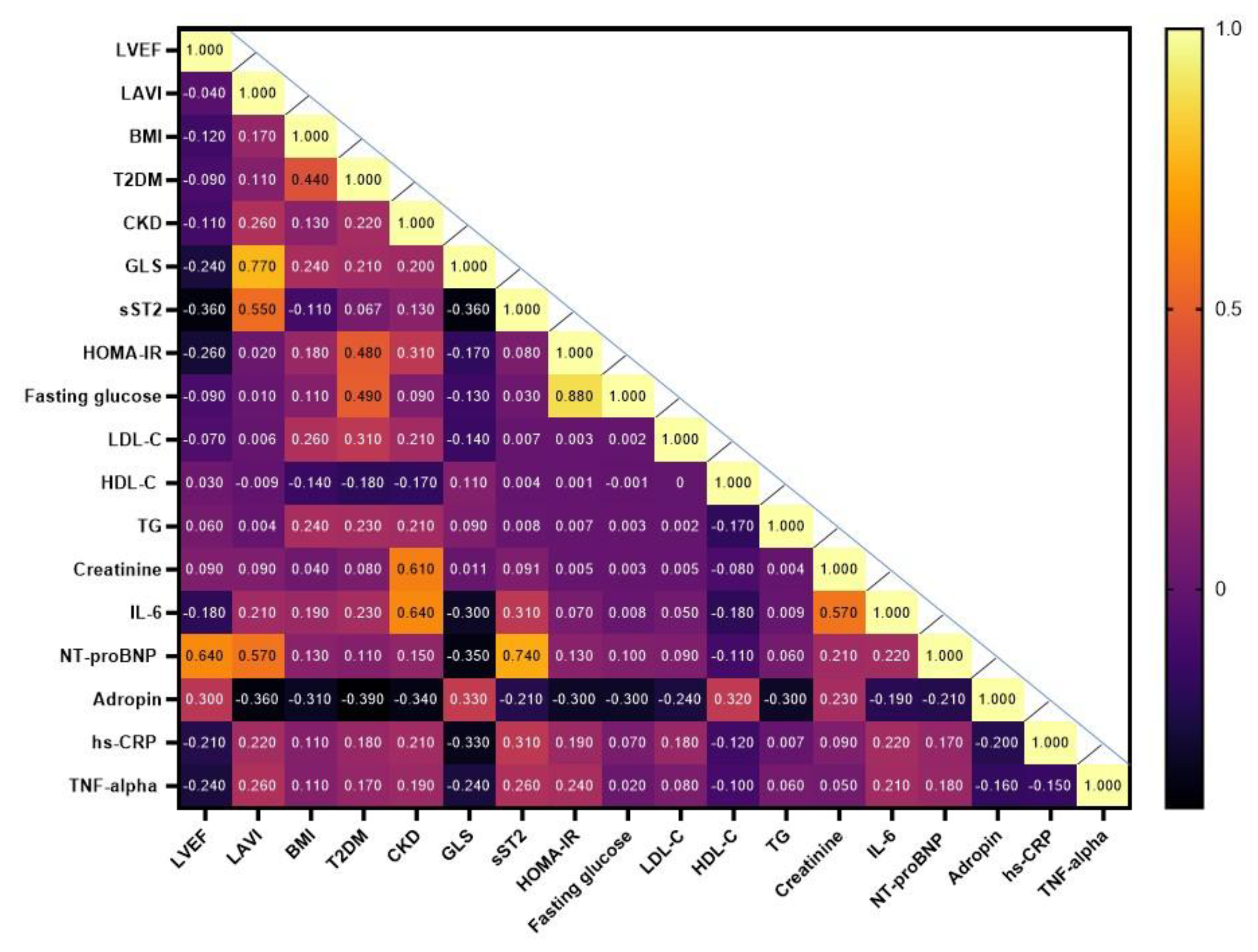

3.2. Spearman’s Correlations Between Hemodynamic Parameters, Comorbidities and Biomarkers

The heat map provides a visual representation of the Spearmen correlation coefficients between each pair of variables including age, gender, hemodynamic parameters, comorbidities and circulating biomarkers (

Figure 2). The study has shown that the levels of serum adropin positively correlated with LVEF (r = 0.33; P = 0.001), GLS (r = 0.33; P = 0.001), HDL-C levels (r=0.30; p=0.001), creatinine (r=0.26; p=0.002) and inversely correlated with LAVI (r = -0.36; P = 0.001), CKD (r = -0.34; P = 0.001), T2DM (r = -0.39; P = 0.001), BMI (r = -0.31; P = 0.001), triglyceride levels (r = -0.30; P = 0.001), fasting glucose (r = -0.30; P = 0.001), HOMA-IR (r = -0.30; P = 0.012), LDL-C (r = -0.24; P = 0.001) and NT-proBNP(r = -0.21; P = 0.012).

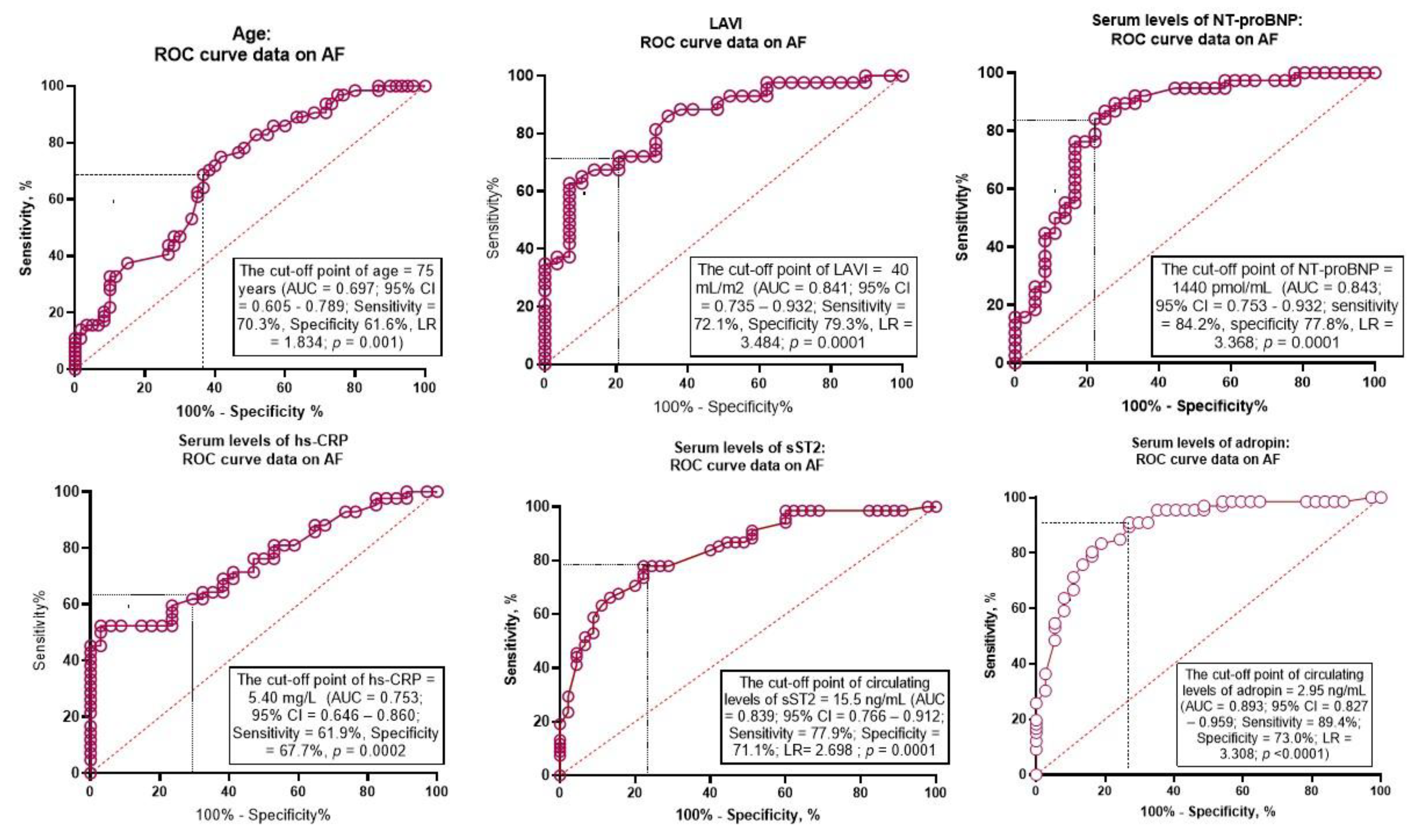

3.3. Predictive Factors of AF: The Results of the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis

ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal cutoff for possible predictors of new onset AF in patients with HFpEF (

Table 2). Age ≥75 years showed the area under curve (AUC) for AF of 0.697 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.712 – 0.740, P = 0.001) with a sensitivity of 70.3% and a specificity of 61.6%.

The well-balanced predictive cutoff point for LAVI was 40 mL/m

2 (AUC = 0.841, 95% CI = 0.735 – 0.932) with a sensitivity of 72.1% and a specificity of 79.3%. The AUC for NT-proBNP was 0.843 (95% CI = 0.751 – 0.932) and predictive cutoff point was 1440 pmol/mL (sensitivity = 84.2%; specificity = 77.8%). Optimal cutoff points for hs-CRP and sST2 were 5.4 mg/L (AUC = 0.753, 95% CI = 0.646 – 0.860, sensitivity = 61.9%; specificity = 67.7%) and 15.5 ng/mL (AUC = 0.839, 95% CI = 0.766 - 0.912; sensitivity = 77.9%; specificity = 71.1%), respectively. The AUC for adropin was 0.893 (95% CI = 0.827 – 0.959) and predictive cutoff point was 2.95 ng/mL (sensitivity = 89.4%; specificity = 73.0%). ROC curves for these variables are presented by

Figure 3.

3.4. Predictive Factors for New Onset AF: Unadjusted and Adjusted for Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Models

Cox proportional hazards model was constructed for assessment of independent predictors of AF (

Table 3). Significant variables (P<0.05) comparing cohorts with and without AF were entered into univariate Cox regression analysis, and those retaining statistical significance (P<0.05) were entered into multivariate Cox proportional hazards model.

In unadjusted rough Cox regression model, age ≥ 75 years, type 2 diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1–3, LAVI ≥40 mL/m2, NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL, hs-CRP ≥5.40 mg/L, adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL, sST2 ≥15.5 ng/mL were identified as the predictors for new onset AF in HFpEF patients. After adjusting for age ≥ 75 years (Model 2), the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1–3, LAVI ≥40 mL/m2, NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL, adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL had discriminative values for AF. Model 3 has revealed that the only the levels of NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL and adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL were independent predictors of AF.

3.5. Comparison of the Predictive Models

We found that discriminative value of adropin was superior to NT-proBNP, while adding adropin to NT-proBNP did not improve predictive information of adropin alone.

Table 4.

The comparisons of predictive models for AF.

Table 4.

The comparisons of predictive models for AF.

| Models |

AUC |

NRI |

IDI |

| M (95% CI) |

p value |

M (95% CI) |

p value |

M (95% CI) |

p value |

| NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL |

0.843 (0.751–0.932) |

- |

Reference |

Reference |

| Adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL |

0.893 (0.827–0.959) |

0.040 |

0.25 (0.21–0.30) |

0.046 |

0.41 (0.32–0.52) |

0.044 |

| NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL + Adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL |

0.929 (0.837–0.974) |

0.048 |

0.29 (0.24–0.35) |

0.040 |

0.48 (0.40–0.56) |

0.042 |

3.6. Reproducibility of Adropin Versus NT-proBNP

The assessment of the reproducibility regarding adropin compared with NT-proBNP has shown that the intra-class correlation coefficients for inter-observer reproducibility of NT-proBNP and adropin were 0.75 (95% CI = 0.69-0.82) and 0.86 (95% CI = 0.80-0.91), respectively. We did not find significant changes in intra-observer reproducibility of adropin in relation to age and gender in eligible patients (p = 0.316 and p = 0.412).

4. Discussion

In the 3-year longitudinal multicenter study, we found that age ≥ 75 years, type 2 diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1–3, LAVI ≥40 mL/m2, NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL, hs-CRP ≥5.40 mg/L, adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL, sST2 ≥15.5 ng/mL significantly predicted incident AF. After adjusting for age ≥ 75 years, the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and CKD stages 1–3 adropin and NT-proBNP remained independent predictors for AF in this patient population. Moreover, we have first identified a higher predictive value of low circulating adropin when compared with elevated NT-proBNP for new episodes of AF in symptomatic patients with HFpEF.

Despite a wide implementation of international guideline for AF in the routine clinical praxis, identifying patients at high risk of new AF remains challenging. Previous clinical studies and meta-analysis have shown that AF episodes and their progression from paroxysmal to non-paroxysmal forms depend on combinations of several conditions and parameters, including older age, a history of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, hypertension, diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, LVH, cardiac surgery, cardiomyopathies, LA asynchrony and LA remodeling, heart rhythm disturbance, LV diastolic and systolic dysfunction, low hematocrit and hemoglobin, elevated levels of HbA1c, natriuretic peptides, galectin-3, sST2, and hs-CRP [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. There is little evidence for HFpEF patients without a previous history of AF who were treated with optimal GDMT. Although elevated level of NT-proBNP was a predictor of incident AF during the first 2 years of long-term observation, it remains unclear, whether the discriminative value of natriuretic peptide(s) remains accurate in individuals with HFpEF and coexisting overweight, obesity or type 2 diabetes mellitus [

48,

49]. Indeed, glycosylation and obesity may affect the prognostic value of NT-proBNP regarding AF [

50,

51], while NT-pro-BNP significantly improved the predictive ability of conventional cardiovascular risk factors and the novel CHARGE-AF risk score for AF [

52]. On the other hand, the biomarkers, which relate to cardiac fibrosis (galectin-3, sST2), inflammation (ha-CRP, IL-6, TNF-alpha) and myocardial injury (cardiac troponins), did not provide the superiority over NT-proBNP in predicting AF in individuals without previous incident of AF [

52,

53]. In this context, a discovery of new non-invasive, easily accessible biomarkers that could stratify HFpEF patients depending on the risk of new onset AF appears to be promising.

In our study, we have identified low levels of adropin as promising biomarker of higher risk of AF in HFpEF patients who were optimally treated with GDMT and had target / near target levels of NT-proBNP (<1000 pmol/mL). These findings are likely to be practically useful, because they allow providing a clear approach to risk stratification beyond respectively time-consuming analysis of LA remodeling. Because in recent clinical studies has been proven a linear correlation between serum adropin concentrations and LA diameter, LAVI, LA strain in patients with AF [

54,

55], it could suggest that a decrease in the concentration of this peptide may precede the manifestation of AF and LA volume overload.

Being not only an independent risk factor for heart disease, but also a metabolic regulator of the cardiovascular system's adaptation to the progression of adverse cardiac remodeling and HF, adropin is likely to be a promising prognostic biomarker for these conditions. Unfortunately, there is little rigorous clinical evidence of the superiority of adropin over natriuretic peptides and other biomarkers of biomechanical stress, inflammation, cardiac fibrosis, and myocardial damage. Most of them were obtained in cohort studies and require further validation [

28,

30,

33,

35,

55]. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that adropin may play a protective role in cardiovascular remodeling and that its deficiency represents a metabolic maladaptation that potentiates accelerated HF progression. Indeed, extensive researches have explored the pivotal role of adropin, particularly in mechanisms related to inflammation, immune response and oxidative stress through suppression of VEGFR2/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT and VEGFR/c-Src/ERK1/2 signaling [

56]. Moreover, adropin demonstrated direct cardiac and vascular protective effects via modulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor and inhibiting SIRT1 and TNF-alpha-depending apoptosis [

57].

Another aspect of an association of low levels of adropin with the risk of AF is their possible link with endothelial dysfunction, accelerating atherosclerosis and lipid toxicity. Perhaps the loss of the suppressive effect of adropin on ROR-dependent regulation of lipid oxidation may significantly mediate its negative effect on the lipid core formation in atherosclerotic plaques, sub-intimal accumulation of oxidized lipoproteins, disruption of integral functions of the vascular wall, and regulation of vasodilation [

56,

58]. Therefore, adropin downregulated lipogenic proteins SEBP-1 and ADRP and thereby potentiates lipid toxicity, ROS production and mitochondrial dysfunction [

59]. Overall, all these pathogenetic pathways are likely to be crucial for AF development.

On the other hand, in our study we did not find any significant differences in glucose homeostasis parameters, lipid profile between HFpEF patients with AF and with sinus rhythms, whereas adropin levels were sufficient different. However, the associations between adropin levels and the parameters mentioned above were found. We hypothesized that adropin playing an important role in the overall regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism is not the plausible factor that mediates variability of these parameters. On the contrary, liver perfusion and hepatocyte metabolism are likely to be in the loop of the regulation of adropin levels in circulating blood. Along with it, adipose tissue inflammation and concomitant diabetes may intervene in expression of adropin in remote tissue and thereby limit organ protective capability of the peptide.

Finally, as we had hypothesized, adropin is a promising indicator of a higher risk of new onset AF in individuals with HFpEF, whose predictive potency exceeds that of NT-proBNP. These findings open up a new perspective for a large-scale clinical study to develop a new risk stratification model for these patients.

5. Study Limitations

The study has several limitations. The first limitation affects the lack of data regarding a trajectory of biological markers during the observational period in connection with new cases of AF. Additionally, we did not investigate nutritional status among the patients and its association with the changes of adropin levels. Finally, we did not compare the discriminative value of adropin with previously validate risk scores, such as Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology model for atrial fibrillation (CHARGE-AF). However, we do not believe that these limitations will have an impact on the interpretation of the results.

6. Conclusions

We found that after adjusting for age ≥ 75 years, a presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and CKD stages 1–3, the levels of NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL and adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL were independent predictors of new onset AF in patients HFpEF. Moreover, adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL presented more predictive information than NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL alone, whereas the combination of both biomarkers did not improve the predictive ability of adropin alone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.B.; methodology, A.E.B.; software, O.O.B.; validation, T.A.B., A.E.B., M.L.; formal analysis, O.O.B., T.A.B., and A.E.B.; investigation, O.O.B. and T.A.B.; resources, T.A.B. and O.O.B.; data curation, A.E.B. and T.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation: T.A.B.; O.O.B., E.V.N.; M.L., and A.E.B.; writing—review and editing, T.A.B.; O.O.B., E.V.N.; M.L., and A.E.B.; visualization, O.O.B. and E.V.N.; supervision, A.E.B.; project administration, T.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Zaporozhye Medical Academy of Post-graduate Education (protocol number: 8; date of approval: 10 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all patients in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who gave their consent to participate in this study and all the administrative staff and doctors of the private hospital "Vita Centre" for their assistance in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Sagris M, Vardas EP, Theofilis P, Antonopoulos AS, Oikonomou E, Tousoulis D. Atrial Fibrillation: Pathogenesis, Predisposing Factors, and Genetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 23(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Jin X, Nauta JF, Hung CL, Ouwerkerk W, Teng TK, Voors AA, Lam CS, van Melle JP. Left atrial structure and function in heart failure with reduced (HFrEF) versus preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2022; 27(5):1933-1955. [CrossRef]

- Fauchier L, Bisson A, Bodin A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation: recent advances and open questions. BMC Med. 2023; 21(1):54. [CrossRef]

- Emmons-Bell S, Johnson C, Roth G. Prevalence, incidence and survival of heart failure: a systematic review. Heart. 2022; 108(17):1351-1360. [CrossRef]

- Peigh G, Shah SJ, Patel RB. Left Atrial Myopathy in Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure: Clinical Implications, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Targets. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2021; 18(3):85-98. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi N, Miyasaka Y, Suwa Y, Harada S, Nakai E, Shiojima I. Heart Failure in Atrial Fibrillation - An Update on Clinical and Echocardiographic Implications. Circ J. 2020; 84(8):1212-1217. [CrossRef]

- Newman JD, O'Meara E, Böhm M, Savarese G, Kelly PR, Vardeny O, Allen LA, Lancellotti P, Gottlieb SS, Samad Z, Morris AA, Desai NR, Rosano GMC, Teerlink JR, Giraldo CS, Lindenfeld J. Implications of Atrial Fibrillation for Guideline-Directed Therapy in Patients With Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024; 83(9):932-950. [CrossRef]

- Bidaoui G, Assaf A, Marrouche N. Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure: Novel Insights, Challenges, and Treatment Opportunities. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2024; 22(1):3. [CrossRef]

- La Fazia VM, Pierucci N, Mohanty S, Chiricolo G, Natale A. Atrial Fibrillation Ablation in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2025; 17(1):53-62. [CrossRef]

- Borlaug BA, Sharma K, Shah SJ, Ho JE. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023; 81(18):1810-1834. [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh LA, Robleto E, Lopaschuk GD. Cardiac energy substrate utilization in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: reconciling conflicting evidence on fatty acid and glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2025 Jun 1;328(6):H1267-H1295. [CrossRef]

- Berezin AE, Berezin AA, Lichtenauer M. Myokines and Heart Failure: Challenging Role in Adverse Cardiac Remodeling, Myopathy, and Clinical Outcomes. Dis Markers. 2021;2021:6644631. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Qin D, Hu J, Yang Y, Hu D, Yu B. Inflamed adipose tissue: A culprit underlying obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Front Immunol. 2022;13:947147. [CrossRef]

- Rafaqat S. Adipokines and Their Role in Heart Failure: A Literature Review. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2023 Nov 15;14(11):5657-5669. [CrossRef]

- Hanna A, Frangogiannis NG. Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines as Therapeutic Targets in Heart Failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2020;34(6):849-863. [CrossRef]

- Berezin OO, Berezina TA, Hoppe UC, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Diagnostic and predictive abilities of myokines in patients with heart failure. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2024; 142:45-98. [CrossRef]

- Ali II, D'Souza C, Singh J, Adeghate E. Adropin's Role in Energy Homeostasis and Metabolic Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23(15):8318. [CrossRef]

- Skrzypski M, Wojciechowicz T, Rak A, Krążek M, Fiedorowicz J, Strowski MZ, Nowak KW. The levels of adropin and its therapeutic potential in diabetes. J Endocrinol. 2025; 265(1):e240117. [CrossRef]

- Kumar KG, Trevaskis JL, Lam DD, Sutton GM, Koza RA, Chouljenko VN, Kousoulas KG, Rogers PM, Kesterson RA, Thearle M, Ferrante AW Jr, Mynatt RL, Burris TP, Dong JZ, Halem HA, Culler MD, Heisler LK, Stephens JM, Butler AA. Identification of adropin as a secreted factor linking dietary macronutrient intake with energy homeostasis and lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008 Dec;8(6):468-81. [CrossRef]

- Gao S, Ghoshal S, Zhang L, Stevens JR, McCommis KS, Finck BN, Lopaschuk GD, Butler AA. The peptide hormone adropin regulates signal transduction pathways controlling hepatic glucose metabolism in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(36):13366-13377. [CrossRef]

- Jasaszwili M, Wojciechowicz T, Billert M, Strowski MZ, Nowak KW, Skrzypski M. Effects of adropin on proliferation and differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells and rat primary preadipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2019;496:110532. [CrossRef]

- Liang M, Dickel N, Györfi AH, SafakTümerdem B, Li YN, Rigau AR, Liang C, Hong X, Shen L, Matei AE, Trinh-Minh T, Tran-Manh C, Zhou X, Zehender A, Kreuter A, Zou H, Schett G, Kunz M, Distler JHW. Attenuation of fibroblast activation and fibrosis by adropin in systemic sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(740):eadd6570. [CrossRef]

- Butler AA, Havel PJ. Adropin: A cardio-metabolic hormone in the periphery, a neurohormone in the brain? Peptides. 2025 May;187:171391. [CrossRef]

- Jurrissen TJ, Ramirez-Perez FI, Cabral-Amador FJ, Soares RN, Pettit-Mee RJ, Betancourt-Cortes EE, McMillan NJ, Sharma N, Rocha HNM, Fujie S, Morales-Quinones M, Lazo-Fernandez Y, Butler AA, Banerjee S, Sacks HS, Ibdah JA, Parks EJ, Rector RS, Manrique-Acevedo C, Martinez-Lemus LA, Padilla J. Role of adropin in arterial stiffening associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022 Nov 1;323(5):H879-H891. [CrossRef]

- Vural A, Kurt D, Karagöz A, Emecen Ö, Aydin E. The Relationship Between Coronary Collateral Circulation and Serum Adropin Levels. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e35166. [CrossRef]

- Berezin AA, Obradovic Z, Berezina TA, Boxhammer E, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Cardiac Hepatopathy: New Perspectives on Old Problems through a Prism of Endogenous Metabolic Regulations by Hepatokines. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(2):516. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh Kumar K, Zhang J, Gao S, Rossi J, McGuinness OP, Halem HH, Culler MD, Mynatt RL, Butler AA. Adropin deficiency is associated with increased adiposity and insulin resistance. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(7):1394-402. [CrossRef]

- Berezina TA, Berezin OO, Hoppe UC, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Low Levels of Adropin Predict Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Outpatients with Newly Diagnosed Prediabetes after Acute Myocardial Infarction. Biomedicines. 2024;12(8):1857. [CrossRef]

- Kalkan AK, Cakmak HA, Erturk M, Kalkan KE, Uzun F, Tasbulak O, Diker VO, Aydin S, Celik A. Adropin and Irisin in Patients with Cardiac Cachexia. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018; 111(1):39-47. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Cui B, Zhao X, Wu Y, Qin H, Guo Y, Wang H, Lu M, Zhang S, Shen J, Shi X, Liang W, Ma S, Li Q, Zhu A, Qi H. Correlation of Serum Adropin Levels with Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease in Hemodialysis Patients. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2021 Sep;19(7):401-408. [CrossRef]

- Adıyaman MŞ, Canpolat Erkan RE, Kaya İ, Aba Adıyaman Ö. Serum Adropin Level in the Early Period of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Its Relationship With Cobalamin and Folic Acid. Cureus. 2022;14(12):e32748. [CrossRef]

- Bays JA, Bartlett AM, Boone AM, Kim Y, Yu Z, Palle SK, Short KR. Serum adropin is unaltered in adolescents with histology-confirmed steatotic liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025;80(1):182-188. [CrossRef]

- Berezina TA, Berezin OO, Hoppe UC, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Low Levels of Adropin Predict Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Outpatients with Newly Diagnosed Prediabetes after Acute Myocardial Infarction. Biomedicines. 2024;12(8):1857. [CrossRef]

- El Moneem Elfedawy MA, El Sadek Elsebai SA, Tawfik HM, Youness ER, Zaki M. Adropin a candidate diagnostic biomarker for cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2024;22(4):100438. [CrossRef]

- Kaur R, Krishan P, Kumari P, Singh T, Singh V, Singh R, Ahmad SF. Clinical Significance of Adropin and Afamin in Evaluating Renal Function and Cardiovascular Health in the Presence of CKD-MBD Biomarkers in Chronic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(19):3158. [CrossRef]

- Berezina TA, Berezin OO, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Predictors for Irreversibility of Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Obesity After Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography. Adv Ther. 2025; 42(1):293-309. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(1):4-131. [CrossRef]

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373-498. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):507. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):546-547. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2021;42(40):4194. [CrossRef]

- January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Furie KL, Heidenreich PA, Murray KT, Shea JB, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019;140(2):e125-e151. Erratum in: Circulation. 2019;140(6):e285. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Rahko, P.S.; Blauwet, L.A.; Canaday, B.; Finstuen, J.A.; Foster, M.C.; Horton, K.; Ogunyankin, K.O.; Palma, R.A.; Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2018, 32, 1-64. [CrossRef]

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 150(9):604-12. [CrossRef]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412-419. [CrossRef]

- Karantoumanis I, Doundoulakis I, Zafeiropoulos S, Oikonomou K, Makridis P, Pliakos C, Karvounis H, Giannakoulas G. Atrial conduction time associated predictors of recurrent atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;37(4):1267-1277. [CrossRef]

- Blum S, Meyre P, Aeschbacher S, Berger S, Auberson C, Briel M, Osswald S, Conen D. Incidence and predictors of atrial fibrillation progression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(4):502-510. [CrossRef]

- Turkkolu ST, Selçuk E, Köksal C. Biochemical predictors of postoperative atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):167. [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic M, Kalezic N, Milicic B, Zivkovic M, Ivosevic T, Lakicevic M, Zivaljevic V. Risk Factors for New Onset Atrial Fibrillation during Thyroid Gland Surgery. Med Princ Pract. 2022; 31(6):570-577. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang SH, Liao CF, Chen ZY, Chao TF, Chen SA, Tsao HM. Distinct atrial remodeling in patients with subclinical atrial fibrillation: Lessons from computed tomographic images. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2022;10(2):e00927. [CrossRef]

- Werhahn SM, Becker C, Mende M, Haarmann H, Nolte K, Laufs U, Zeynalova S, Löffler M, Dagres N, Husser D, Dörr M, Gross S, Felix SB, Petersmann A, Herrmann-Lingen C, Binder L, Scherer M, Hasenfuß G, Pieske B, Edelmann F, Wachter R. NT-proBNP as a marker for atrial fibrillation and heart failure in four observational outpatient trials. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9(1):100-109. [CrossRef]

- Staszewsky L, Meessen JMTA, Novelli D, Wienhues-Thelen UH, Disertori M, Maggioni AP, Masson S, Tognoni G, Franzosi MG, Lucci D, Latini R. Total NT-proBNP, a novel biomarker related to recurrent atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):553. [CrossRef]

- Budolfsen C, Schmidt AS, Lauridsen KG, Hoeks CB, Waziri F, Poulsen CB, Riis DN, Rickers H, Løfgren B. NT-proBNP cut-off value for ruling out heart failure in atrial fibrillation patients - A prospective clinical study. Am J Emerg Med. 2023; 71:18-24. [CrossRef]

- Shu H, Cheng J, Li N, Zhang Z, Nie J, Peng Y, Wang Y, Wang DW, Zhou N. Obesity and atrial fibrillation: a narrative review from arrhythmogenic mechanisms to clinical significance. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):192. [CrossRef]

- Svennberg E, Lindahl B, Berglund L, Eggers KM, Venge P, Zethelius B, Rosenqvist M, Lind L, Hijazi Z. NT-proBNP is a powerful predictor for incident atrial fibrillation - Validation of a multimarker approach. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:74-81. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Zhou T, Li J, Yuan C, Li C, Chen S, Shen C, Gu D, Lu X, Liu F. Association between NT-proBNP levels and risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Heart. 2025;111(3):109-116. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Xue Y, Shang F, Ni S, Liu X, Fan B, Wang H. Association of serum adropin with the presence of atrial fibrillation and atrial remodeling. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019; 33(2):e22672. [CrossRef]

- Berezin AA, Obradovic Z, Fushtey IM, Berezina TA, Novikov EV, Schmidbauer L, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. The Impact of SGLT2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin on Adropin Serum Levels in Men and Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Chronic Heart Failure. Biomedicines. 2023; 11(2):457. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Ding N, Chen C, Gu S, Liu J, Wang Y, Lin L, Zheng Y, Li Y. Adropin: a key player in immune cell homeostasis and regulation of inflammation in several diseases. Front Immunol. 2025; 16:1482308. [CrossRef]

- Gao S, McMillan RP, Jacas J, Zhu Q, Li X, Kumar GK, Casals N, Hegardt FG, Robbins PD, Lopaschuk GD, Hulver MW, Butler AA. Regulation of substrate oxidation preferences in muscle by the peptide hormone adropin. Diabetes. 2014;63(10):3242-52. [CrossRef]

- Ying T, Wu L, Lan T, Wei Z, Hu D, Ke Y, Jiang Q, Fang J. Adropin inhibits the progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE-/-/Enho-/- mice by regulating endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):402. [CrossRef]

- Yu M, Wang D, Zhong D, Xie W, Luo J. Adropin Carried by Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Nanocapsules Ameliorates Renal Lipid Toxicity in Diabetic Mice. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(33):37330-37344. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design. Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AF, atrial fibrillation; CV, cardiovascular; GLS, global longitudinal stain; E/e': the ratio of the E-wave velocity to the average of the medial and lateral e' velocities; ESRD, end stage renal disease; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; HFmrEF, heart failure mildly reduced ejection fraction; HOMA-IR, the Homeostatic Assessment Model of Insulin Resistance; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; LAVI, left atrial volume index; MI, myocardial infarct; TNF-alpha, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; hs-TnT, high-sensitivity troponin T; IL, interleukin; sST2, soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2; NT-proBNP, N-terminal natriuretic pro-peptide.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design. Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AF, atrial fibrillation; CV, cardiovascular; GLS, global longitudinal stain; E/e': the ratio of the E-wave velocity to the average of the medial and lateral e' velocities; ESRD, end stage renal disease; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure reduced ejection fraction; HFmrEF, heart failure mildly reduced ejection fraction; HOMA-IR, the Homeostatic Assessment Model of Insulin Resistance; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; LAVI, left atrial volume index; MI, myocardial infarct; TNF-alpha, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; hs-TnT, high-sensitivity troponin T; IL, interleukin; sST2, soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2; NT-proBNP, N-terminal natriuretic pro-peptide.

Figure 2.

Heat map with Spearmen correlations between each pair of variables. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; GLS, global longitudinal strain; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Assessment Model of Insulin Resistance; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IL, interleukin; NT-proBNP, N-terminal brain natriuretic pro-peptide; TG, triglycerides; sST2, soluble suppressor tumorigenisity-2; TNF-alpha, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Figure 2.

Heat map with Spearmen correlations between each pair of variables. Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; GLS, global longitudinal strain; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Assessment Model of Insulin Resistance; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IL, interleukin; NT-proBNP, N-terminal brain natriuretic pro-peptide; TG, triglycerides; sST2, soluble suppressor tumorigenisity-2; TNF-alpha, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for possible predictors of AF. Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; CI, confidence interval; ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve; LR, positive likelihood ratio; LAVI, left atrial volume index; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; sST2, soluble suppressor tumorigenisity-2; NT-proBNP, N-terminal brain natriuretic pro-peptide.

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves for possible predictors of AF. Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; CI, confidence interval; ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve; LR, positive likelihood ratio; LAVI, left atrial volume index; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; sST2, soluble suppressor tumorigenisity-2; NT-proBNP, N-terminal brain natriuretic pro-peptide.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the patients involved in this study.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the patients involved in this study.

| Variables |

Entire Group Patients with HFpEF (n = 953) |

Patients with HFpEF and AF (n = 172) |

Patients with HFpEF and sinus rhythm (n = 781) |

p Value |

| Demographics and anthropomorphic parameters |

| Age (years) |

69 (54–85) |

75 (61–87) |

66 (52–81) |

0.042 |

| Male (n (%)) |

497 (52.2) |

92 (53.5) |

405 (51.9) |

0.818 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

26.9 ± 7.20 |

27.6 ± 6.10 |

25.8 ± 5.80 |

0.680 |

| Waist circumference (cm) |

99 ± 8 |

101 ± 5 |

98 ± 9 |

0.730 |

| WHR (units) |

0.90 ± 0.13 |

0.91 ± 0.10 |

0.90 ± 0.14 |

0.850 |

| Medical history |

| Dyslipidemia (n (%)) |

588 (62.0) |

108 (62.8) |

480 (61.5) |

0.846 |

| Hypertension (n (%)) |

838 (87.9) |

153 (88.9) |

685 (87.7) |

0.890 |

| Stable CAD (n (%)) |

343 (36.0) |

64 (37.2) |

279 (35.7) |

0.388 |

| Dilated CMP, (n (%)) |

58 (6.1) |

12 (7.0) |

46 (5.9) |

0.482 |

| Smoking (n (%)) |

335 (35.2) |

65 (37.7) |

270 (34.5) |

0.358 |

| Abdominal obesity (n (%)) |

278 (29.2) |

48 (27.9) |

230 (29.4) |

0.642 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, (n (%)) |

356 (37.4) |

72 (41.9) |

284 (36.4) |

0.042 |

| LVH (n (%)) |

676 (70.9) |

128 (74.4) |

548 (70.2) |

0.056 |

| CKD stages 1–3 (n (%)) |

251 (26.3) |

69 (40.1) |

182 (23.3) |

0.043 |

| New York Heart Association class II / III |

385 (40.4) / 568 (59.6) |

65 (37.8) / 107 (62.2) |

320 (41.0) / 461 (59.0) |

0.710 |

| Hemodynamics |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) |

143 ± 11 |

147± 8 |

140 ± 13 |

0.840 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) |

87 ± 9 |

86 ± 9 |

87 ± 10 |

0.780 |

| LVEDV (mL) |

158 (144–173) |

160 (142–181) |

157 (140–178) |

0.650 |

| LVESV (mL) |

73 (63–82) |

73 (62–86) |

71 (60–83) |

0.612 |

| LVEF (%) |

54 (51–57) |

53 (51–56) |

55 (52–59) |

0.545 |

| LVMMI (g/m2) |

144 ± 16 |

148 ± 19 |

142 ± 18 |

0.477 |

| LAVI (mL/m2) |

38 (33–44) |

40 (35–48) |

37 (32–43) |

0.046 |

| E/e` (units) |

19 ± 6 |

20 ± 4 |

19 ± 5 |

0.811 |

| GLS (%) |

−17.9 (−16.4; −19.2) |

−18.2 (−16.7; −19.8) |

−17.1 (−16.3; −19.5) |

0.266 |

| Biomarkers |

| Hemoglobin, g/L |

146 (132-158) |

144 (131-155) |

147 (130-162) |

0.673 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

81 ± 17 |

77 ± 19 |

83 ± 15 |

0.533 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) |

4.95 ± 0.9 |

5.07 ± 1.1 |

4.91 ± 1.2 |

0.810 |

| HOMA-IR (units) |

7.43 ± 2.5 |

7.47± 2.3 |

7.38 ± 2.8 |

0.650 |

| HbA1c (%) |

6.42 ± 0.16 |

6.45 ± 0.15 |

6.38 ± 0.20 |

0.711 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) |

109.8 ± 21.6 |

115.6± 20.1 |

102.2 ± 23.2 |

0.520 |

| SUA (µmol/L) |

347 ± 120 |

359 ± 118 |

346 ± 135 |

0.351 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) |

5.72 ± 1.30 |

5.80 ± 1.25 |

5.70 ± 1.28 |

0.433 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) |

0.99 ± 0.15 |

1.01 ± 0.14 |

0.99 ± 0.16 |

0.355 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) |

3.84± 0.22 |

3.90 ± 0.20 |

3.81± 0.22 |

0.590 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) |

2.21 ± 0.16 |

2.23 ± 0.15 |

2.20 ± 0.17 |

0.620 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) |

6.05 (2.98–9.17) |

6.38 (3.18–9.75) |

5.87 (2.24–9.56) |

0.048 |

| TNF-alpha (pg/mL) |

3.46 (2.15–4.86) |

3.52 (2.09–4.93) |

3.29 (1.98–4.80) |

0.580 |

| NT-proBNP (pmol/mL) |

1068 (375–1606) |

1360 (532–1850) |

986 (343–1657) |

0.042 |

| Adropin (ng/mL) |

3.48 (1.58–5.45) |

2.93 (1.25–4.58) |

3.72 (1.69–5.80) |

0.044 |

| Galectin-3 (ng/mL) |

4.24 (1.15–7.46) |

4.31 (1.08–7.55) |

4.15 (1.01–7.31) |

0.312 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) |

1.98 (0.80–3.15) |

2.14 (0.93 – 3.21) |

1.92 (0.77 – 3.09) |

0.060 |

| sST2 (ng/mL) |

11.2 (3.46 – 18.9) |

14.3 (3.54 – 20.2) |

10.9 (2.87 – 19.1) |

0.044 |

| hs-TnT, ng/mL |

0.06 (0.011–0.117) |

0.07 (0.013–0.122) |

0.05 (0.005–0.116) |

0.548 |

| Concomitant medications |

| ACEIs (n (%)) |

715 (75.0) |

123 (71.5) |

592 (75.8) |

0.174 |

| ARBs (n (%)) |

152 (15.9) |

24 (14.0) |

128 (16.4) |

0.046 |

| ARNI, (n (%)) |

36 (3.8) |

5 (2.9) |

31 (4.0) |

0.050 |

| Beta-blockers (n (%)) |

851 (89.3) |

137 (79.7) |

714 (91.4) |

0.048 |

| Ivabradine (n (%)) |

137 (14.4) |

18 (10.5) |

119 (15.2) |

0.046 |

| CCBs (n (%)) |

181 (19.0) |

33 (19.2) |

148 (19.0) |

0.880 |

| Loop and thiazide-like diuretics (n (%)) |

891 (93.5) |

163 (94.8) |

728 (93.2) |

0.835 |

| Antiplatelet agents (n (%)) |

793 (83.2) |

144 (83.7) |

649 (83.1) |

0.882 |

| Anticoagulants (n (%)) |

91 (9.5) |

15 (8.7) |

76 (9.7) |

0.828 |

| Metformin (n (%)) |

325 (34.1) |

57 (33.1) |

268 (34.3) |

0.850 |

| DPP4 inhibitors (n (%)) |

31 (3.2) |

5 (2.9) |

26 (3.3) |

0.162 |

| GLP-1 RAs (n (%)) |

48 (5.0) |

8 (4.7) |

40 (5.1) |

0.116 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors (n (%)) |

811 (85.0) |

127 (73.8) |

684 (87.6) |

0.042 |

| Statins (n (%)) |

856 (89.8) |

152 (88.4) |

704 (90.1) |

0.820 |

Table 2.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis for Predictive Factors of AF.

Table 2.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis for Predictive Factors of AF.

| Variables |

AUC |

95% CI |

p value |

Cutoff |

Se, % |

Sp,% |

| Age |

0.697 |

0.605 – 0.789 |

0.0002 |

75 years |

70.3 |

61.6 |

| LAVI |

0.841 |

0.735 – 0.932 |

0.0001 |

40 mL/m2

|

72.1 |

79.3 |

| NT-proBNP |

0.843 |

0.751 – 0.932 |

0.0001 |

1440 pmol/mL |

84.2 |

77.8 |

| hs-CRP |

0.753 |

0.646 – 0.860 |

0.0002 |

5.40 mg/L |

61.9 |

67.7 |

| Adropin |

0.893 |

0.827 – 0.959 |

0.0001 |

2.95 ng/mL |

89.4 |

73.0 |

| sST2 |

0.839 |

0.766 - 0.912 |

0.0001 |

15.5 ng/mL |

77.9 |

71.1 |

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis for predictive factors of AF.

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis for predictive factors of AF.

| Predictive factors |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| HR (95% CI) |

P value |

HR (95% CI) |

P value |

HR (95% CI) |

P value |

| Age≥75 years |

1.215 (1.046–1.448) |

0.046 |

- |

- |

| LVH (presence vs absent) |

1.036 (0.988-1.122) |

0.466 |

- |

- |

| T2DM (presence vs absent) |

1.366 (1.124–1.578) |

0.044 |

1.325 (1.118–1.543) |

0.048 |

- |

| CKD stages 1–3 (presence vs absent) |

1.292 (1.164–1.459) |

0.012 |

1.203 (1.018–1.422) |

0.050 |

- |

| New York Heart Association HF class (III vs II) |

1.216 (1.002-1.452) |

0.064 |

- |

- |

| LAVI ≥40 mL/m2

|

1.533 (1.117–1.956) |

0.001 |

1.411 (1.104–1.847) |

0.026 |

- |

| NT-proBNP ≥1440 pmol/mL |

1.497 (1.125–2.833) |

0.001 |

1.541 (1.116–2.253) |

0.001 |

1.536 (1.120–2.247) |

0.001 |

| hs-CRP ≥5.40 mg/L |

1.126 (1.014–1.843) |

0.048 |

1.088 (1.035–1.106) |

0.052 |

1.049 (1.013–1.098) |

0.144 |

| Adropin ≤2.95 ng/mL |

1.783 (1.255–2.815) |

0.001 |

1.696 (1.247–2.990) |

0.001 |

1.690 (1.240–2.864) |

0.001 |

| sST2 ≥15.5 ng/mL |

1.246 (1.112–1.878) |

0.012 |

1.215 (1.088–1.830) |

0.051 |

1.176 (1.043–1.820) |

0.062 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).