1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) remains a high prevalent life-threatening condition in older adults that is associated with a high 1-year risk of death and hospitalization, poor functional capacity and quality of life [

1]. A median prevalence rate of all HF phenotype has 11.8% (range 4.7-13.3%), but over the last decade HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is more common [median prevalence 4.9% (range 3.8-7.4%) and 3.3% (range 2.4-5.8%), respectively] than HF reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [

2]. However, HF prevalence, new incidence and survival varied widely in close connection with age, gender, ethnicity, HF phenotype, concomitant comorbidity profile, as well as certain socio-demographic factors including affordability of health system resources and guideline-directed medical therapies [

3,

4,

5]. On the other hand, early-to-moderate stages of HFpEF remains more frequently under-recognized than symptomatic HFrEF / HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF) in everyday practice due to a wide range of comorbidity pattern including metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, respiratory and autoimmune diseases [

6,

7].

Although patients with any HF phenotypes showed a strict similarity in short-term hospitalization rate, long-term survival rate may vary sufficiently depending on age, HF etiology, comorbidity status and N-terminal natriuretic pro-peptide (NT-proBNP) levels [

8]. In fact, HF patients with low (< 300 ng/L) / near normal (< 125 ng/L) NT-proBNP levels had a better prognosis than those with elevated NT-proBNP levels (>300 ng/L), regardless of HF phenotype [

9]. A high proportion of the individuals with any HF phenotypes with low NT-proBNP levels exhibit a high incidence of diabetes and obesity. Aline with it, among of those who reached target levels of NT-proBNP (< 1000 ng/L) there were no significant differences in the presence of metabolic comorbidities, but many patients had better clinical status, cardiac performance including improved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), quality of life and greater longevity than those with higher NT-proBNP [

10,

11].

Another aspect concerns patients with HF who were discharged from hospital after decompensation with hemodynamic stability, improved LVEF and low NT-proBNP. More of them were treated with conventional guideline-based therapy, including renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2i) inhibitors [

12]. However, near normal / low levels of NT-proBNP seems not to be a significant predictive factor for further adverse clinical outcomes including mortality and HF-related outcomes when compared with elevated concentrations of this pro-peptide [

13]. In fact, there are no evidence-based recommendations for clinical risk assessment in patients with HF with improved LVEF (HFimpEF) / HFpEF with low / near normal NT-proBNP [

14]. Although numerous clinical studies have identified numerous plausible predictors (male sex, left atrial volume index, left ventricular end diastolic dimension, anemia, neutrophil count, the levels of myokines / hepatokines including irisin and adropin, glomerular filtration rate, creatinine, pre-existing kidney failure, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus) for these patients [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], reliable predictors corresponding with this clinical presentation remain to be under scientific discussion. Moreover, the predictive utility of metabolic-related factors for HF outcomes, such as adipokines with inflammatory activity, myokines, hepatokines, inflammatory cytokines, are not still fully recognized [

20,

21,

22].

Indeed, visceral, perivascular and epicardial adipose tissues, myocardium, skeletal muscles, liver are considered endocrine organs that synthesize and release a broad spectrum of cytokines with pro- and anti-inflammatory properties, many of which are directly and indirectly involved in the pathogenesis of adverse cardiac remodeling and are responsible for HF development and progression [

23]. Apelin is an anti-inflammatory and angiopoetic adipokine, whose levels are markedly reduced in patients with chronic HF and upregulated after reversible cardiac remodeling [

24]. Circulating levels of visfatin – a metabolic regulator of oxidative phosphorylation and suppressor of oxidative stress - were found to be significantly lower in patients with HF [

25]. Patients with HF especially those with HFrEF and HFmrEF had sufficiently reduced serum concentrations of adipokine / myokines irisin, which has organ protective and anti-inflammatory properties, and increased levels of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha and C-reactive protein [

26]. Fetuin-A – multifunctional adipokine / hepatokines (known as tissue chaperone) with organoprotective properties – exerted a link with liver hypoperfusion in HFrEF and inversely correlated with exercise tolerance and survival [

27]. However, their discriminative abilities in patients with HFpEF with low NT-proBNP have not yet been deeply studied. The aim of the study is to detect plausible predictors for poor one-year clinical outcomes in patients with HFpEF and low NT-proBNP treated with in accordance with conventional guideline.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

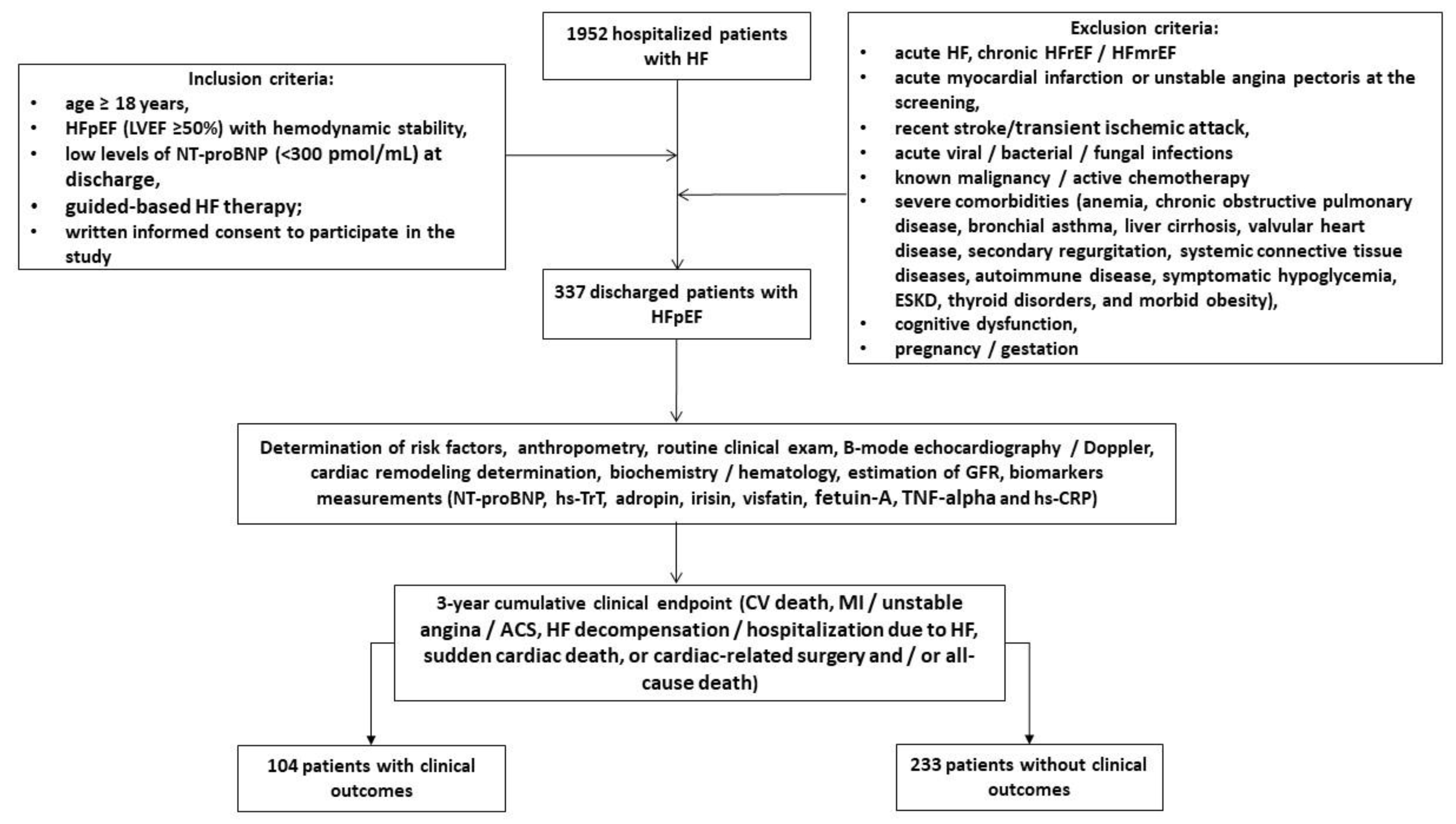

Using our local database, we pre-screened 1952 patients with HF who were hospitalized for HF progression and finally enrolled 337 discharged patients according to the inclusion criteria: age ≥. 18 years, hemodynamic stability and established HFpEF at hospital discharge, low levels of N-terminal natriuretic pro-peptide (NT-proBNP) due to optimal guideline-based therapy, and written informed consent to participate in the study (

Figure 1). The major exclusion criteria were patients with acute HF, HF with reduced (HFrEF) and mildly reduced (HFmrEF) ejection fraction, acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, recent stroke / transient ischemic attack, acute viral and bacterial infection, known malignancy, active chemotherapy, with severe comorbidities, including end stage renal disease (ESRD), cognitive dysfunction/dementia, pregnancy/gestation. We followed patients for 3 years and divided them into two cohorts depending on the presence of clinical combined outcome: 104 patients exhibited clinical events, whereas 233 individuals did not have them.

2.2. Determination of Clinical Outcomes and Follow-Up

We determine 3-year cumulative clinical endpoint that included CV death, myocardial infarction / unstable angina / acute coronary syndrome, HF decompensation / hospitalization due to HF, sudden cardiac death, or cardiac-related surgery and / or all-cause death. To detect cumulative clinical endpoint we utilized direct interview with patients, their relatives, contact with general practitioners, as well as review of databases, discharge and autopsy reports. Follow-up data were collected via clinic visits at baseline (at discharge from the hospital), during 36 months after the study entry.

2.3. Echocardiography Examination

In the study, all patents were undergone a routine transthoracic B-mode and Doppler ultrasound examination, which had been provided by experienced echo cardiographer in apical 2- and 4-chamber views using a GE Healthcare Vivid E95 scanner (General Electric Company, Horton, Norway). The conventional hemodynamic parameters included the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by using Simpson’s method, the left ventricular end-diastolic (LVEDV) and end-systolic (LVESV) volumes, the left atrial volume index (LAVI), early diastolic blood filling (E), and the mean longitudinal strain ratio (e‘) were evaluated according to 2018 Guideline of the American Society of Echocardiography [

28]. The estimated E/e' ratio was expressed as the ratio of the E-wave velocity to the average of the medial and lateral e' velocities. After acquisition of high-quality echocardiographic data during at least three cardiac cycles, LV GLS was obtained by 2D speckle-tracking image analysis. The data were stored in the DICOM format for subsequent analysis. Left ventricular hypertrophy was defined as a left ventricular mass index (LVMI) ≥95 g/m

2 in women or ≥115 g/m

2 in men [

28].

2.4. Blood Sampling

Blood samples were obtained from all participants in fasting condition and collected in BD Vacutainer Serum Plus Tube. After centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and stored at -70°C until analysis.

2.5. Biomarkers Assessment

Conventional hematological and biochemical parameters were determined with a Roche P800 analyzer (Basel, Switzerland) in the local laboratory of the Vita Centre (Zaporozhye, Ukraine). Data on blood routine indices glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high density lipoprotein (HDL-C) and low density lipoprotein (LDL-C) cholesterol, serum uric acid, and serum creatinine were recorded. In addition, we measured circulating biomarkers (NT-proBNP, tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-alpha], high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP], adropin, irisin, visfatin, fetuin-A) in serum using ELISA kits (Elabscience, Houston, Texas, USA) in accordance with the instructions provided by the manufacturer at the initial baseline measurement and at the end of the study. The data obtained from the ELISA analysis were subjected to a standard curve-based evaluation. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate, and the mean value was employed for the final analysis. Both intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variability for each marker were < 10%.

2.7. Glomerular Filtration Rate Estimation

Conventional CKD-EPI formula was to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [

29].

2.8. Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 11.0 for Windows and Graph Pad Prism, version 9 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine whether data were normally distributed. All continues variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation [SD] median and interquartile range [IQR] depending on whether the data were normally distributed, whereas categorical variables were presented as number (n) and percentage (%). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test. The Mann-Whitey U test was used to compare differences in continuous variables between cohorts with and without combined clinical events. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to calculate the cutoff values of irisin for predicting combined clinical event. To determine the optimal cut-off value for the predictors, Youden's index (sensitivity + specificity - 1) was used. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard model were constructed to predict the independent prognostic factors for the clinical endpoint. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported for each predictor variable. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to compare the survival rates, and survival curves were plotted. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Clinical Characteristics

A total of 337 patients with HFpEF, New York Heart Association class II (n = 133) / III (n = 204) and low NT-proBNP at discharge were enrolled in the study and divided into two cohorts depending on a presence of 3-year cumulative end point (n=104) or an absent of it (n=233). The follow-up time was 3 years. The clinical characteristics of patients outlined in

Table 1.

Patients in entire group had a mean age of 61 years and showed the following profile of comorbidity conditions: dyslipidemia (60.2%), hypertension (84.6%), stable coronary artery disease (33.5%), atrial fibrillation (18.1%), smoking (39.2%), abdominal obesity (28.2%), diabetes mellitus (31.5%), left ventricular hypertrophy (73.0%), and chronic kidney disease 1-3 stages (21.3%). Therefore, all patients were hemodynamically stable, had a mean LVEF of 54%, an average of LAVI of 39 mL/m2, a mean of GLS of -15.2%. The therapy of the patients were personally optimized and included antagonists of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin-II receptor blockers or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors), beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor and other concomitant medications. There were no significant differences between the two cohorts with respect to sex, body mass index, anthropometric parameters, presence of dyslipidemia, hypertension, stable coronary artery disease, smoking, abdominal obesity, left ventricular hypertrophy, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, left ventricular dimensions, LVEF, LVMMI, E/e`, GLS, eGFR, lipid profile, glucose levels, TNF-alpha, NT-proBNP, adropin, visfatin, fetuin-A, hs-TrT. Patients in the cumulative clinical endpoint cohort were older, more likely to have atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1-3, dilated cardiomyopathy and higher LAVI and lower irisin levels than those in the free endpoint cohort. The patients in the cumulative clinical endpoint cohort tended to treat frequently with angiotensin-II receptor blockers, anticoagulants, metformin when compared with those who had no clinical endpoint.

3.2. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis for Predictive Factors of Cumulative Clinical Endpoint

ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the optimal cutoff for possible predictors of clinical outcome in (

Table 2). Age ≥64 years exhibited area under curve (AUC) for cumulative endpoint of 0.726 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.712 – 0.740, P = 0.001) with a sensitivity of 76.2% and a specificity of 74.5%. Optimal predictive cutoff point for LAVI was 39 mL/m

2 (AUC = 0.771, 95% CI = 0.723 – 0.835) with a sensitivity of 78.5% and a specificity of 82.0%. The AUC for hs-CRP was 0.755 (95% CI = 0.695 – 0.819) and predictive cutoff point was 6.10 mg/L (sensitivity = 77.3%; specificity = 80.8%). Optimal cutoff points for irisin and visfatin were 7.2 ng/mL (AUC = 0.868, 95% CI = 0.799 – 0.948, sensitivity = 83.4%; specificity = 86.3) and 1.1 ng/mL (AUC = 0.757, 95% CI = 0.733 – 0.787; sensitivity = 80.5%; specificity = 81.9), respectively.

3.3. Predictive Factors for 3-Year Cumulative Clinical Endpoint: Unadjusted and Adjusted for Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Models

Cox proportional hazards model was constructed for assessment of independent predictors of 3-year cumulative clinical endpoint (

Table 3). Significant variables (P<0.05) comparing cohorts with and without cumulative endpoints were entered into univariate Cox regression analysis, and those retaining statistical significance (P<0.05) were entered into multivariate Cox proportional hazards model.

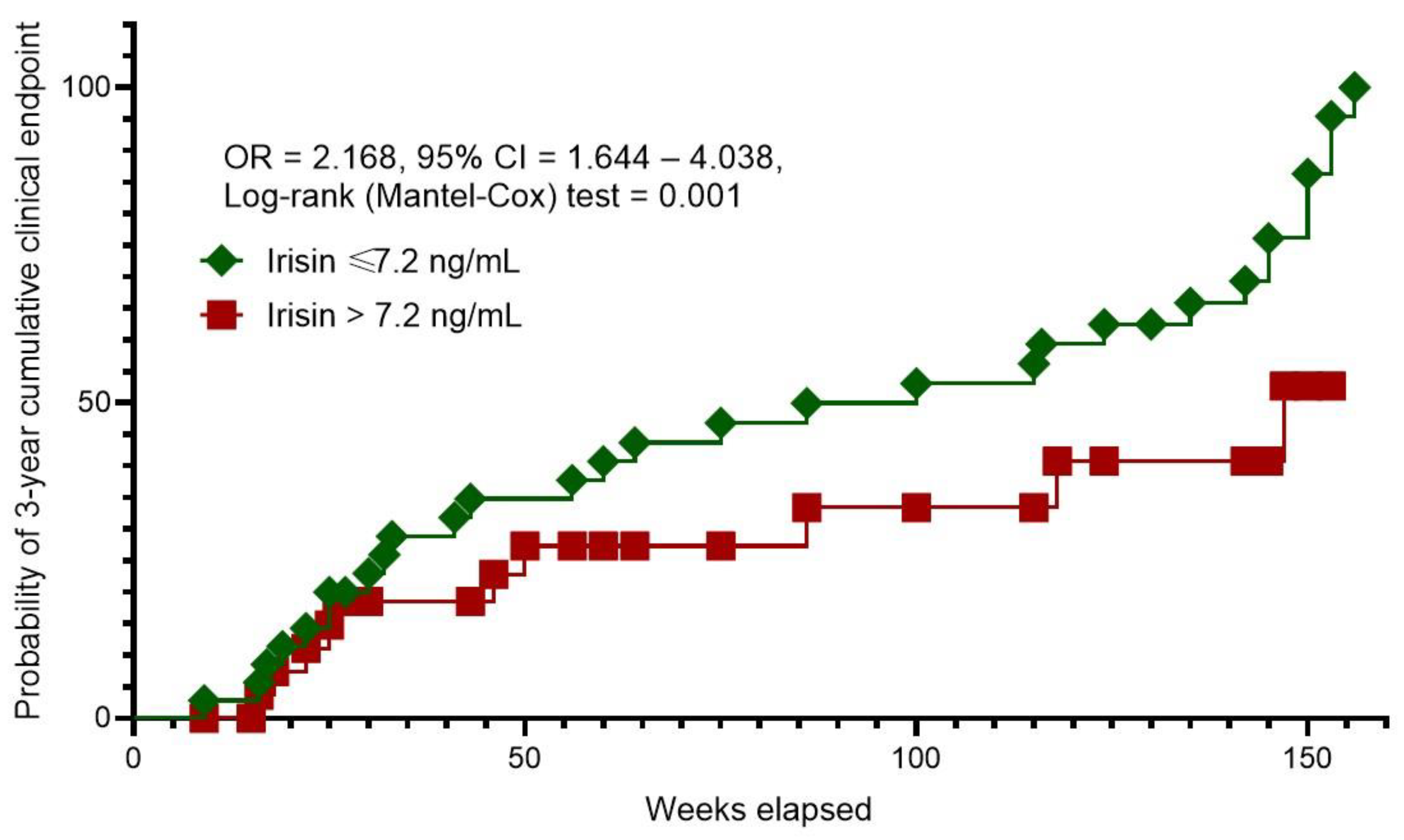

After adjusting for age ≥ 64 years, a presence of atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1–3 and dilated cardiomyopathy (Model 2), the multivariable Cox regression analysis revealed that the levels of irisin ≤7.2 ng/mL was an independent predictor of cumulative clinical endpoint.

3.4. Kaplan–Meier Curves Survival Analysis

The Kaplan–Meier curves revealed different probability rates of 3-year cumulative clinical endpoint between patients with HFpEF and serum irisin levels of ≤7.2 ng/mL and >7.2 ng/mL (

Figure 2). To note, the patients with the levels of irisin >7.2 ng/mL had a sufficient benefit in survival than those with serum irisin levels of ≤7.2 ng/mL.

4. Discussion

In the study we identified age ≥ 64 years, the presence of atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1–3 and dilated cardiomyopathy, LAVI ≥39 mL/m2, serum levels of hs-CRP ≥6.10 mg/L, irisin ≤7.2 ng/mL and visfatin ≤1.1 ng/mL as predictors of poor clinical outcome in HFpEF patients treated with guideline-based optimal therapy with target level of NT-proBNP less than 300 pmol/mL. After adjusting for concomitant comorbidities and age serum levels of irisin ≤7.2 ng/mL remained to be an independent predictive factor for 3-year cumulative clinical endpoint. Moreover, the individuals with circulating irisin >7.2 ng/mL exerted a significant superiority in survival rate when compared with those with lower irisin levels (≤7.2 ng/mL). These findings offer new perspectives in the stratification of patients with HFpEF who have achieved target NT-proBNP levels as a result of conventional management and / or concomitant comorbidities such as obesity.

Previous studies and systematic reviews highlighted the plausible prognostic role of BNP and NT-proBNP in predicting adverse clinical outcome including all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization in HFpEF patients, [

13,

30,

31]. However, predictive role of NPs in HFpEF seem to be controversial, because low levels of NT-proBNP often leave the risk of HF progression underestimated [

32]. Meanwhile, patients hospitalized with HFpEF often have low NT-proBNP levels, which was associated with age < 65 years, ischemic etiology, obesity, higher LVEF, eGFR > 80 ml/kg/1.73m

2, and lower NYHA class, whereas chronic kidney disease and diabetes mellitus were associated with elevated levels of NT-proBNP [

9,

33,

34]. Along with it, clinical status was similarly impaired in HF patients with lower and higher NT-proBNP levels [

35]. Azzo JD et al. (2024) [

36] reported that higher levels of NT-proBNP rather associated with inflammation and fibrosis than low concentrations of the biomarker. On the other hand, the elevation of NT-proBNP in serial measurements reflected dynamic change in risk for HF events and death, whereas stable levels of NT-proBNP were related to lower risk of incident HF and mortality [

37]. Thus, the risk of patients with low NP levels remains often out of the zone of interest or is only used as a reference level when comparing to higher values of NT-proBNP. The use of cardiac troponins as an alternative biomarker for risk stratification in a patient with low NT-proBNP levels also remains inadequate because a positive troponin test improves the predictive and diagnostic value of natriuretic peptides only when their concentrations are high [

38]. In this context, the search for new biomarkers with independent predictive value for adverse clinical events in HFpEF and low NT-proBNP remains very relevant.

We hypothesized that the comorbidity signature may not only contribute to adverse cardiac remodeling, but also be associated with a distinct cytokine profile reflecting metabolic homeostasis of distant organs such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and liver. Although these organs synthesizes and secretes a wide range of metabolically active molecules involved in the development and progression of HF, their discriminative properties for HF, particularly in people with HFpEF, have not been established. In this study, we established that apart from older age and such known concomitant comorbidities as atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1–3 and dilated cardiomyopathy, altered levels of hs-CRP, visfatin and irisin, which belong to adipokines / myokines were predictors for cumulative clinical endpoint for 3 years in patients with HFpEF and low levels of NT-proBNP. In fact, irisin ≤7.2 ng/mL alone was found to be an independent predictor of adverse clinical outcomes for patients with HFpEF after adjusting for age and concomitant comorbidities.

Previous studies have shown that irisin can be synthesized and secreted not only by skeletal muscle but also by myocardium to maintain energy homeostasis [

39]. Alteration of irisin levels in HF is considered a possible mechanism of skeletal muscle metabolic remodelling, cardiac hypertrophy and persistence of a clinical sign such as fatigue [

40]. Moreover, in chronic HFpEF patients rather than HFmrEF and HFrEF low levels of irisin exerted predictive potency for adverse outcomes [

15,

41,

42]. Since irisin has shown inverse correlation with inflammatory biomarkers such as CRP and TNF-alpha, and LDL in previous studies, it was hypothesized that one of the possible molecular mechanisms for the negative impact of altered levels of irisin on prognosis is excessive inflammatory response, oxidative stress / damage and mitochondrial dysfunction due to activation of apoptosis / pyroptosis and autophagy via irisin precursor fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 and AKT/GSK3β/FYN/Nrf2 axis in an mTOR-independent manner [

43,

44]. In this context, altered irisin regulation links adverse cardiac remodeling and skeletal muscle dysfunction with metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, obesity and metabolic syndrome [

45,

46]. However, the predictive value of irisin for distant events in patients with HFpEF requires further explanation. An indirect effect of irisin deficiency on the number of cardiovascular events through the progression of microvascular inflammation and impaired myocardial perfusion cannot be excluded. This suggestion seems to be a purpose for further investigations.

5. Study Limitations

The study has several limitations. The first limitation affects the lack of data regarding a trajectory of biological markers during the observational period in connection with the rate of adverse clinical outcomes. Yet, we did not investigate quality of life of the patients and its association with the changes of irisin levels. Finally, we did not compare the discriminative value of irisin with previously validate risk score. However, we do not believe that these limitations will have an impact on the interpretation of the results.

6. Conclusions

We found that age ≥ 64 years, the presence of atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, CKD stages 1–3 and dilated cardiomyopathy, LAVI ≥39 mL/m2, serum levels of hs-CRP ≥6.10 mg/L, irisin ≤7.2 ng/mL and visfatin ≤1.1 ng/mL as predictors of poor clinical outcome in HFpEF. Serum levels of irisin ≤7.2 ng/mL could emerge as valuable biomarker for predicting long-term prognosis among HFpEF patients with low or near normal levels of NT-proBNP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.B.; methodology, A.E.B.; software, O.O.B.; validation, T.A.B., A.E.B., M.L.; formal analysis, O.O.B., T.A.B., and A.E.B.; investigation, O.O.B. and T.A.B.; resources, T.A.B. and O.O.B.; data curation, A.E.B. and T.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation: T.A.B.; O.O.B., E.V.N.; M.L., and A.E.B.; writing—review and editing, T.A.B.; O.O.B., E.V.N.; M.L., and A.E.B.; visualization, O.O.B. and E.V.N.; supervision, A.E.B.; project administration, T.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Zaporozhye Medical Academy of Post-graduate Education (protocol number: 8; date of approval: 10 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all patients in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who gave their consent to participate in this study and all the administrative staff and doctors of the private hospital "Vita Centre" for their assistance in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Emmons-Bell S, Johnson C, Roth G. Prevalence, incidence and survival of heart failure: a systematic review. Heart. 2022; 108(17):1351-1360. [CrossRef]

- van Riet EE, Hoes AW, Wagenaar KP, Limburg A, Landman MA, Rutten FH. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(3):242-52. [CrossRef]

- Yu B, Akushevich I, Yashkin AP, Yashin AI, Lyerly HK, Kravchenko J. Epidemiology of geographic disparities in heart failure among US older adults: a Medicare-based analysis. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1280. [CrossRef]

- Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2023; 118(17):3272-3287. Erratum in: Cardiovasc Res. 2023; 119(6):1453. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvad026. [CrossRef]

- Desai RJ, Stonely D, Ikram N, Levin R, Bhatt AS, Vaduganathan M. County-Level Variation in Triple Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Adv. 2024 Jun 12;3(7):101014. [CrossRef]

- Campbell P, Rutten FH, Lee MM, Hawkins NM, Petrie MC. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: everything the clinician needs to know. Lancet. 2024;403(10431):1083-1092. Epub 2024 Feb 14. Erratum in: Lancet. 2024;403(10431):1026. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00494-X. PMID: 38367642. [CrossRef]

- Palazzuoli A, Ruocco G, Gronda E. Noncardiac comorbidity clustering in heart failure: an overlooked aspect with potential therapeutic door. Heart Fail Rev. 2022;27(3):767-778. PMID: 32382883. [CrossRef]

- Borlaug BA, Sharma K, Shah SJ, Ho JE. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(18):1810-1834. [CrossRef]

- Chen YY, Liang L, Tian PC, Feng JY, Huang LY, Huang BP, Zhao XM, Wu YH, Wang J, Guan JY, Li XQ, Zhang J, Zhang YH. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and low NT-proBNP levels. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023; 102(47):e36351. [CrossRef]

- Pieske B, Wachter R, Shah SJ, Baldridge A, Szeczoedy P, Ibram G, Shi V, Zhao Z, Cowie MR; PARALLAX Investigators and Committee members. Effect of Sacubitril/Valsartan vs Standard Medical Therapies on Plasma NT-proBNP Concentration and Submaximal Exercise Capacity in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: The PARALLAX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021; 326(19):1919-1929. [CrossRef]

- Januzzi JL Jr, Prescott MF, Butler J, Felker GM, Maisel AS, McCague K, Camacho A, Piña IL, Rocha RA, Shah AM, Williamson KM, Solomon SD; PROVE-HF Investigators. Association of Change in N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Following Initiation of Sacubitril-Valsartan Treatment With Cardiac Structure and Function in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA. 2019; 322(11):1085-1095. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox JE, Fang JC, Margulies KB, Mann DL. Heart Failure With Recovered Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020; 76(6):719-734. [CrossRef]

- Ammar LA, Massoud GP, Chidiac C, Booz GW, Altara R, Zouein FA. BNP and NT-proBNP as prognostic biomarkers for the prediction of adverse outcomes in HFpEF patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2024 Oct 7. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39373821. [CrossRef]

- Pensa AV, Khan SS, Shah RV, Wilcox JE. Heart failure with improved ejection fraction: Beyond diagnosis to trajectory analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;82:102-112. [CrossRef]

- Berezina TA, Fushtey IM, Berezin AA, Pavlov SV, Berezin AE. Predictors of Kidney Function Outcomes and Their Relation to SGLT2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Who Had Chronic Heart Failure. Adv Ther. 2024 Jan;41(1):292-314. [CrossRef]

- Çavuşoğlu Y, Çelik A, Altay H, Nalbantgil S, Özden Ö, Temizhan A, Ural D, Ünlü S, Yılmaz MB, Zoghi M. Heart failure with non-reduced ejection fraction: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, phenotypes, diagnosis and treatment approaches. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2022; 50(Supp1):S1-S34. [CrossRef]

- Berezin AA, Obradovic AB, Fushtey IM, Berezina TA, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Low Plasma Levels of Irisin Predict Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023;10(4):136. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Qiao Y, Tang J, Guo Y, Liu K, Yang B, Zhou Y, Yang K, Shen S, Guo T, Guo J. Frequency, predictors, and prognosis of heart failure with improved left ventricular ejection fraction: a single-centre retrospective observational cohort study. ESC Heart Fail. 2021; 8(4):2755-2764. [CrossRef]

- Wu N, Lang X, Zhang Y, Zhao B, Zhang Y. Predictors and Prognostic Factors of Heart Failure with Improved Ejection Fraction. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2024; 25(8):280. [CrossRef]

- Berezin AE, Berezin AA, Lichtenauer M. Myokines and Heart Failure: Challenging Role in Adverse Cardiac Remodeling, Myopathy, and Clinical Outcomes. Dis Markers. 2021;2021:6644631. [CrossRef]

- Tomita Y, Misaka T, Yoshihisa A, Ichijo Y, Ishibashi S, Matsuda M, Yamadera Y, Ohara H, Sugawara Y, Hotsuki Y, Watanabe K, Anzai F, Sato Y, Sato T, Oikawa M, Kobayashi A, Takeishi Y. Decreases in hepatokine Fetuin-A levels are associated with hepatic hypoperfusion and predict cardiac outcomes in patients with heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol. 2022;111(10):1104-1112. [CrossRef]

- Kalkan AK, Cakmak HA, Erturk M, Kalkan KE, Uzun F, Tasbulak O, Diker VO, Aydin S, Celik A. Adropin and Irisin in Patients with Cardiac Cachexia. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;111(1):39-47. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Qin D, Hu J, Yang Y, Hu D, Yu B. Inflamed adipose tissue: A culprit underlying obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Front Immunol. 2022;13:947147. [CrossRef]

- Rafaqat S. Adipokines and Their Role in Heart Failure: A Literature Review. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2023 Nov 15;14(11):5657-5669. [CrossRef]

- Straburzyńska-Migaj E, Pilaczyńska-Szcześniak L, Nowak A, Straburzyńska-Lupa A, Sliwicka E, Grajek S. Serum concentration of visfatin is decreased in patients with chronic heart failure. Acta Biochim Pol. 2012; 59(3):339-43.

- Abd El-Mottaleb NA, Galal HM, El Maghraby KM, Gadallah AI. Serum irisin level in myocardial infarction patients with or without heart failure. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019;97(10):932-938. [CrossRef]

- Tomita Y, Misaka T, Sugawara Y, Ichijo Y, Anzai F, Sato Y, Kimishima Y, Yokokawa T, Sato T, Oikawa M, Kobayashi A, Yoshihisa A, Takeishi Y. Reduced Fetuin-A Levels Are Associated With Exercise Intolerance and Predict the Risk of Adverse Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure: The Role of Cardiac-Hepatic-Peripheral Interaction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(17):e035139. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Rahko, P.S.; Blauwet, L.A.; Canaday, B.; Finstuen, J.A.; Foster, M.C.; Horton, K.; Ogunyankin, K.O.; Palma, R.A.; Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2018, 32, 1-64. [CrossRef]

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration). A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 150(9):604-12. [CrossRef]

- Cao J, Jin XJ, Zhou J, Chen ZY, Xu DL, Yang XC, Dong W, Li LW, Luo J, Chen L, Fu M, Zhou JM, Ge JB. [Prognostic value of N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide on all-cause mortality in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2019;47(11):875-881. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt W, Rühs H, Burghaus R, Diedrich C, Duwal S, Eissing T, Garmann D, Meyer M, Ploeger B, Lippert J. NT-proBNP Qualifies as a Surrogate for Clinical End Points in Heart Failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021; 110(2):498-507. [CrossRef]

- Kosyakovsky LB, Liu EE, Wang JK, Myers L, Parekh JK, Knauss H, Lewis GD, Malhotra R, Nayor M, Robbins JM, Gerszten RE, Hamburg NM, McNeill JN, Lau ES, Ho JE. Uncovering Unrecognized Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Among Individuals With Obesity and Dyspnea. Circ Heart Fail. 2024;17(5):e011366. [CrossRef]

- Zheng YR, Ye LF, Cen XJ, Lin JY, Fu JW, Wang LH. Low NT-proBNP levels: An early sign for the diagnosis of ischemic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:666-671. [CrossRef]

- Ceriello A, Lalic N, Montanya E, Valensi P, Khunti K, Hummel M, Schnell O. NT-proBNP point-of-care measurement as a screening tool for heart failure and CVD risk in type 2 diabetes with hypertension. J Diabetes Complications. 2023;37(3):108410. [CrossRef]

- Kondo T, Campbell R, Jhund PS, Anand IS, Carson PE, Lam CSP, Shah SJ, Vaduganathan M, Zannad F, Zile MR, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV. Low Natriuretic Peptide Levels and Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2024;12(8):1442-1455. [CrossRef]

- Azzo JD, Dib MJ, Zagkos L, Zhao L, Wang Z, Chang CP, Ebert C, Salman O, Gan S, Zamani P, Cohen JB, van Empel V, Richards AM, Javaheri A, Mann DL, Rietzschel ER, Schafer PH, Seiffert DA, Gill D, Burgess S, Ramirez-Valle F, Gordon DA, Cappola TP, Chirinos JA. Proteomic Associations of NT-proBNP (N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide) in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2024; 17(2):e011146. [CrossRef]

- Jia X, Al Rifai M, Hoogeveen R, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Shah AM, Ndumele CE, Virani SS, Bozkurt B, Selvin E, Ballantyne CM, Nambi V. Association of Long-term Change in N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide With Incident Heart Failure and Death. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8(3):222-230. [CrossRef]

- Averina M, Stylidis M, Brox J, Schirmer H. NT-ProBNP and high-sensitivity troponin T as screening tests for subclinical chronic heart failure in a general population. ESC Heart Fail. 2022; 9(3):1954-1962. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Xie S, Guo L, Jiang J, Chen H. Irisin: linking metabolism with heart failure. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(10):6003-6014.

- Ho MY, Wang CY. Role of Irisin in Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure, and Cardiac Hypertrophy. Cells. 2021; 10(8):2103. [CrossRef]

- Berezin AA, Lichtenauer M, Boxhammer E, Stöhr E, Berezin AE. Discriminative Value of Serum Irisin in Prediction of Heart Failure with Different Phenotypes among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cells. 2022;11(18):2794. [CrossRef]

- Berezina TA, Berezin OO, Hoppe UC, Lichtenauer M, Berezin AE. Trajectory of Irisin as a Predictor of Kidney-Related Outcomes in Patients with Asymptomatic Heart Failure. Biomedicines. 2024 Aug 12;12(8):1827. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Hu C, Kong CY, Song P, Wu HM, Xu SC, Yuan YP, Deng W, Ma ZG, Tang QZ. FNDC5 alleviates oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activating AKT. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27(2):540-555. [CrossRef]

- Rabiee F, Lachinani L, Ghaedi S, Nasr-Esfahani MH, Megraw TL, Ghaedi K. New insights into the cellular activities of Fndc5/Irisin and its signaling pathways. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:51. [CrossRef]

- Behera J, Ison J, Voor MJ, Tyagi N. Exercise-Linked Skeletal Irisin Ameliorates Diabetes-Associated Osteoporosis by Inhibiting the Oxidative Damage-Dependent miR-150-FNDC5/Pyroptosis Axis. Diabetes. 2022;71(12):2777-2792. PMID: 35802043; PMCID: PMC9750954. [CrossRef]

- Ma EB, Sahar NE, Jeong M, Huh JY. Irisin Exerts Inhibitory Effect on Adipogenesis Through Regulation of Wnt Signaling. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1085. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).