Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

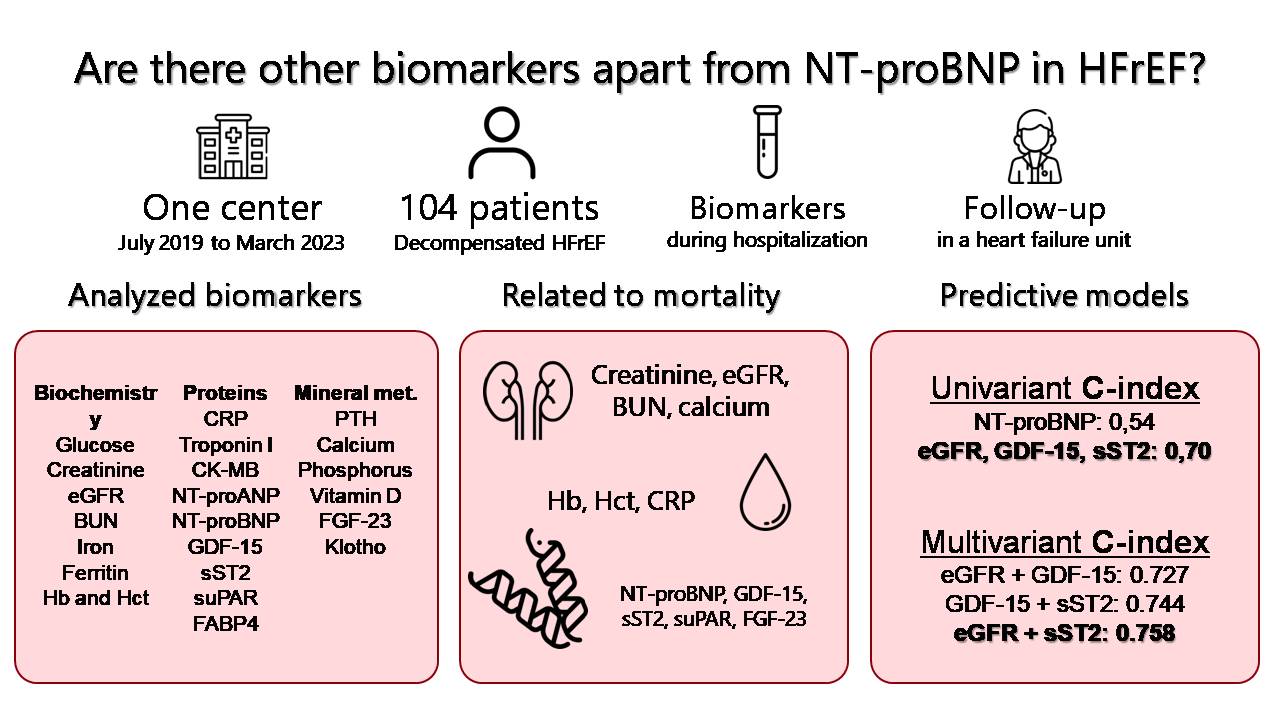

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baseline characteristics of patients

| All-cause death | ||||

| Total | No | Yes | p-Value | |

| (n= 104) | (n= 84) | (n= 20) | ||

| Anthropometric parameters | ||||

| Age (years) | 66.7 (18.3) | 65.5 (16.1) | 76.6 (13.5) | 0.009 |

| Male [n (%)] | 82 (78.8) | 66 (78.6) | 16 (80) | 0.888 |

| Obesity [n (%)] | 39 (37.5) | 34 (40.5) | 5 (25) | 0.199 |

| Risk factors and comorbidities | ||||

| Stroke [n (%)] | 11 (10.6) | 9 (10.7) | 2 (10) | 0.926 |

| Peripheral vascular disease [n (%)] | 9 (8.7) | 7 (8.3) | 2 (10) | 0.683 |

| CPD [n (%)] | 31 (29.8) | 23 (27.4) | 8 (40) | 0.268 |

| CKD [n (%)] | 33 (31.7) | 22 (26.3) | 11 (55) | 0.013 |

| Cancer [n (%)] | 15 (14.4) | 9 (10.7) | 6 (30) | 0.038 |

| STEMI [n (%)] | 29 (27.9) | 24 (28.6) | 5 (25) | 0.749 |

| LVEF (%) | 20 (15) | 20 (15) | 20 (10) | 0.936 |

| Atrial fibrillation [n (%)] | 32 (30.8) | 26 (31.1) | 6 (30) | 0.934 |

| NYHA III-IV [n (%)] | 13 (12.5) | 3 (3.6) | 10 (50) | <0.001 |

| HF [n (%)] | 46 (44.2) | 31 (36.9) | 15 (75) | 0.002 |

| Prior coronary revasc. [n (%)] | 21 (20.2) | 18 (21.4) | 3 (15) | 0.520 |

| Smoking [n (%)] | 37 (35.6) | 30 (35.7) | 7 (35) | 0.952 |

| Diabetes [n (%)] | 49 (47.1) | 41 (48.8) | 8 (40) | 0.448 |

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 69 (66.3) | 56 (66.7) | 13 (65) | 0.887 |

| Dyslipidemia [n (%)] | 58 (55.8) | 47 (56) | 11 (55) | 0.939 |

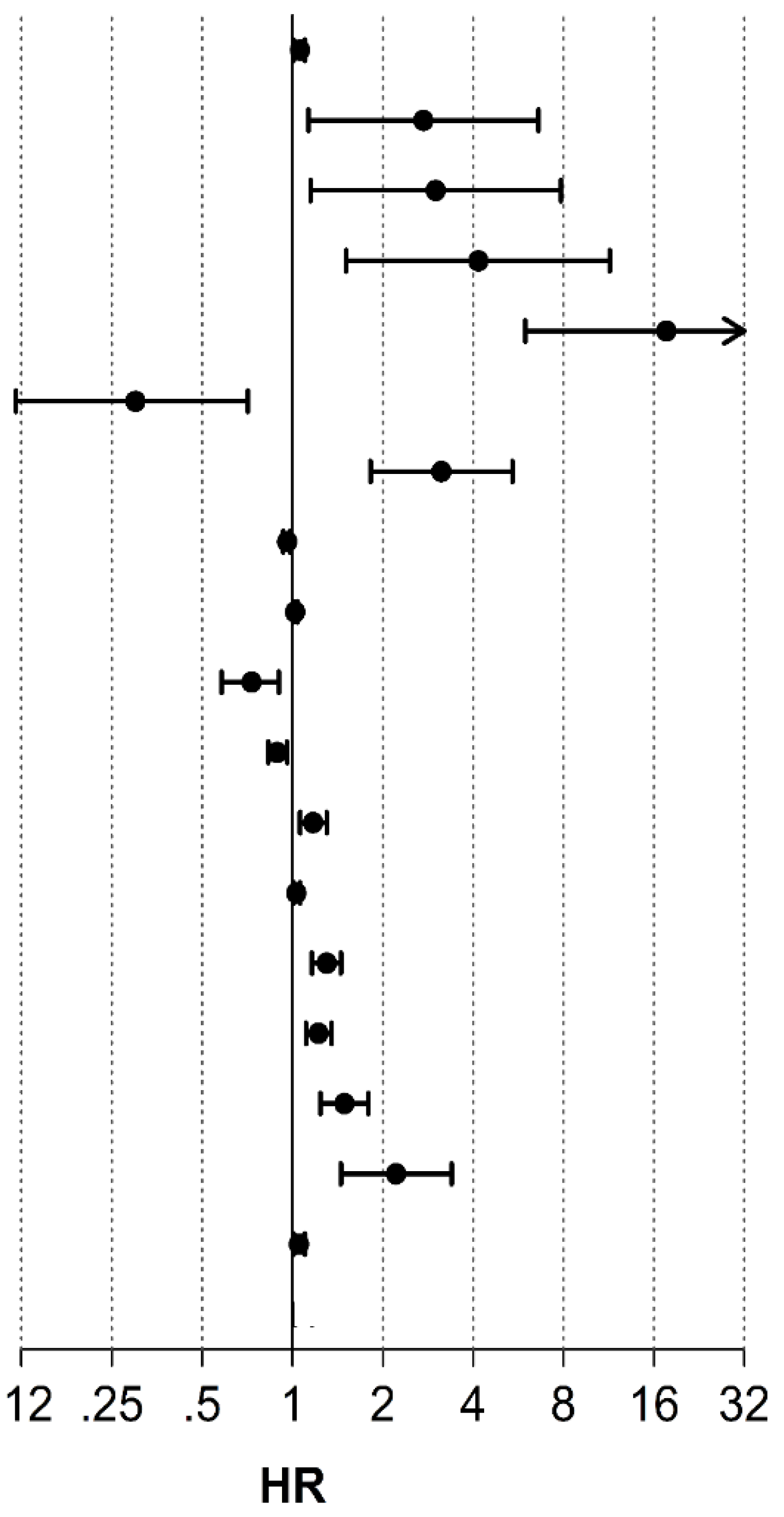

2.2. Association of biomarkers and all-cause death

| All-cause death | ||||

| HR | (95% CI) | p-Value | C-index | |

| Age (years) | 1.07 | 1.01-1.10 | 0.012 | 0.63 |

| CKD [n (%)] | 2.73 | 1.13-6.60 | 0.025 | 0.41 |

| Cancer [n (%)] | 3 | 1.15-7.83 | 0.025 | 0.29 |

| HF [n (%)] | 4.2 | 1.51-11.45 | 0.006 | 0.52 |

| NYHA III-IV [n (%)] | 9.62 | 3.97-23.408 | <0.001 | 0.048 |

| SGLT2i [n (%)] | 0.3 | 0.12-0.71 | 0.007 | 0.45 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 3.13 | 1.82-5.4 | <0.001 | 0.66 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.96 | 0.93-0.98 | <0.001 | 0.7 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 1.02 | 1.01-1.04 | 0.007 | 0.65 |

| HB(g/dL) | 0.73 | 0.58-0.90 | 0.004 | 0.66 |

| Hct (%) | 0.89 | 0.83-0.96 | 0.002 | 0.66 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.17 | 1.06-1.30 | 0.003 | 0.6 |

| NT-ProBNP (pg/mL) | 1.03 | 1.01-1.06 | 0.010 | 0.54 |

| GDF-15 (ng/mL) | 1.3 | 1.16-1.45 | <0.001 | 0.7 |

| sST2 (x10 ng/mL) | 1.2 | 1.11-1.35 | <0.001 | 0.7 |

| suPAR (ng/mL) | 1.49 | 1.24-1.79 | <0.001 | 0.65 |

| FGF-23 (x103 RU/mL) | 2.2 | 1.45-3.39 | <0.001 | 0.56 |

| NT-ProANP (ng/mL) | 1.05 | 1.01-1.10 | 0.024 | 0.57 |

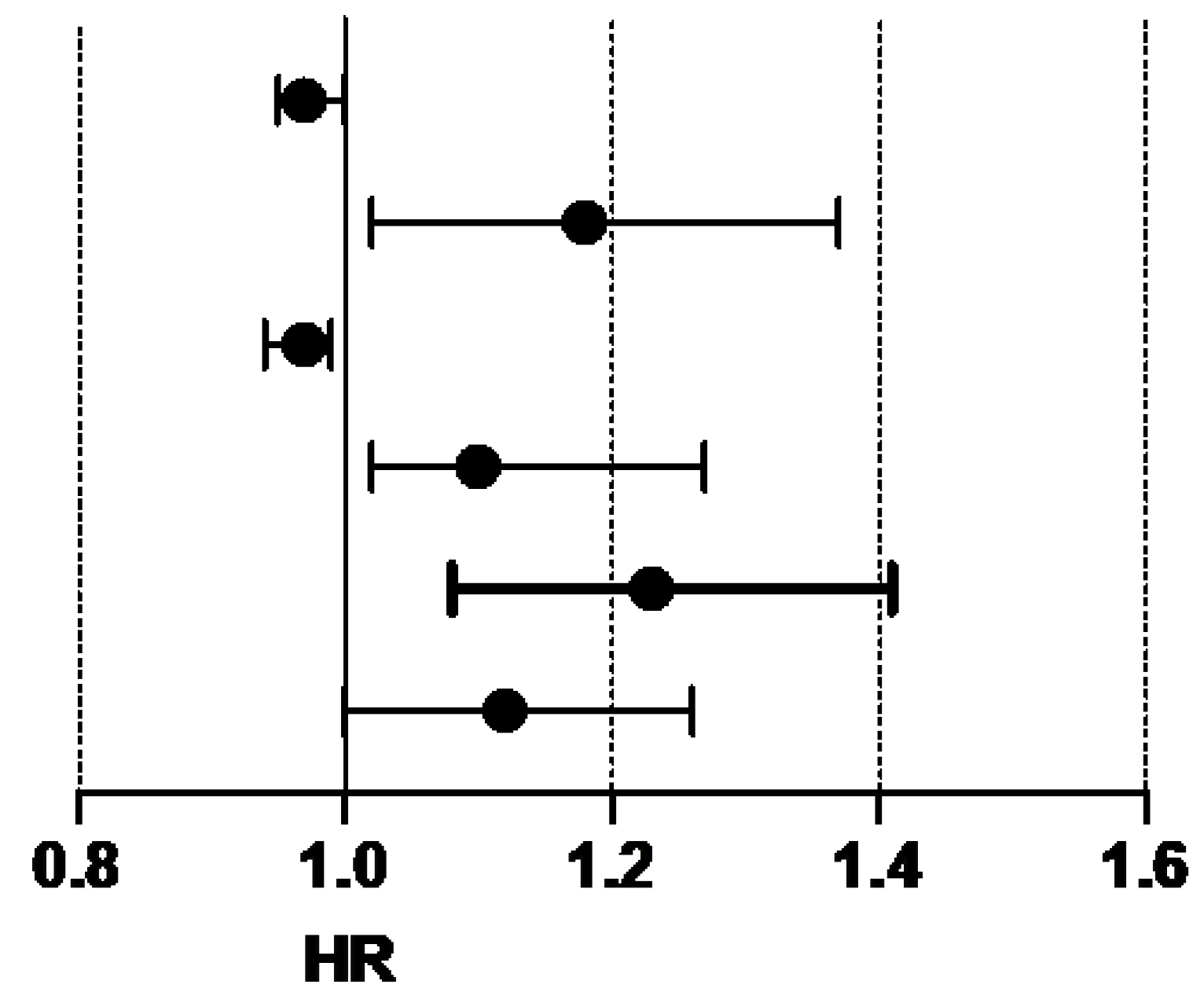

| All-cause death | ||||

| HR | (95% CI) | p-Value | C-index | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.97 | 0.95-1.00 | 0.069 | 0.727 |

| GDF-15(ng/mL) | 1.18 | 1.02-1.37 | 0.031 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.97 | 0.94-0.99 | 0.009 | 0.758 |

| sST2 (x10 ng/mL) | 1.1 | 1.02-1.27 | 0.020 | |

| GDF-15(ng/mL) | 1.23 | 1.08-1.41 | 0.002 | 0.744 |

| sST2 (x10 ng/mL) | 1.12 | 1-1.26 | 0.051 | |

2.3. Hospital Readmissionsfor Heart Failure

| Heart Failure readmission | ||||

| Total | No | Yes | p-Value | |

| (n= 104) | (n= 83) | (n= 21) | ||

| Anthropometric parameters | ||||

| Age (years) | 66.7 (18.3) | 66.7(20.1) | 64.8 (12.14) | 0.310 |

| Male [n (%)] | 82 (78.8) | 66 (79.5) | 16 (76.2) | 0.739 |

| Obesit [n (%)] | 39 (37.5) | 30 (36.1) | 9 (42.9) | 0.570 |

| Risk factors and comorbidities | ||||

| Stroke [n (%)] | 11 (10.6) | 8 (9.6) | 3 (14.3) | 0.691 |

| Peripheral vasc dis.[n (%)] | 9 (8.7) | 6 (7.2) | 3 (14.3) | 0.381 |

| COPD [n (%)] | 31 (29.8) | 22 (26.5) | 9 (42.9) | 0.183 |

| CKD [n (%)] | 33 (31.7) | 23 (27.7) | 10 (47.6) | 0.080 |

| Cancer [n (%)] | 15 (14.4) | 14 (16.9) | 1 (4.8) | 0.295 |

| STEMI [n (%)] | 29 (27.9) | 20 (24.1) | 9 (42.9) | 0.087 |

| LVEF (%) | 20 (15) | 20 (15) | 20 (10) | 0.953 |

| Atrial fibrillation [n (%)] | 32 (30.8) | 23 (27.7) | 9 (42.9) | 0.179 |

| NYHA III-IV [n (%)] | 13 (12.5) | 4 (4.8) | 9 (42.9) | <0.001 |

| HF [n (%)] | 46 (44.2) | 29 (34.9) | 17 (81) | <0.001 |

| Prior coronary revasc. [n (%)] | 21 (20.2) | 12 (14.5) | 9 (42.9) | 0.012 |

| Smoking [n (%)] | 37 (35.6) | 28 (33.7) | 9 (42.9) | 0.435 |

| Diabetes [n (%)] | 49 (47.1) | 39 (47) | 10 (47.6) | 0.959 |

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 69 (66.3) | 55 (66.3) | 14 (66.7) | 0.972 |

| Dyslipidemia [n (%)] | 58 (55.8) | 49 (59) | 9 (42.9) | 0.182 |

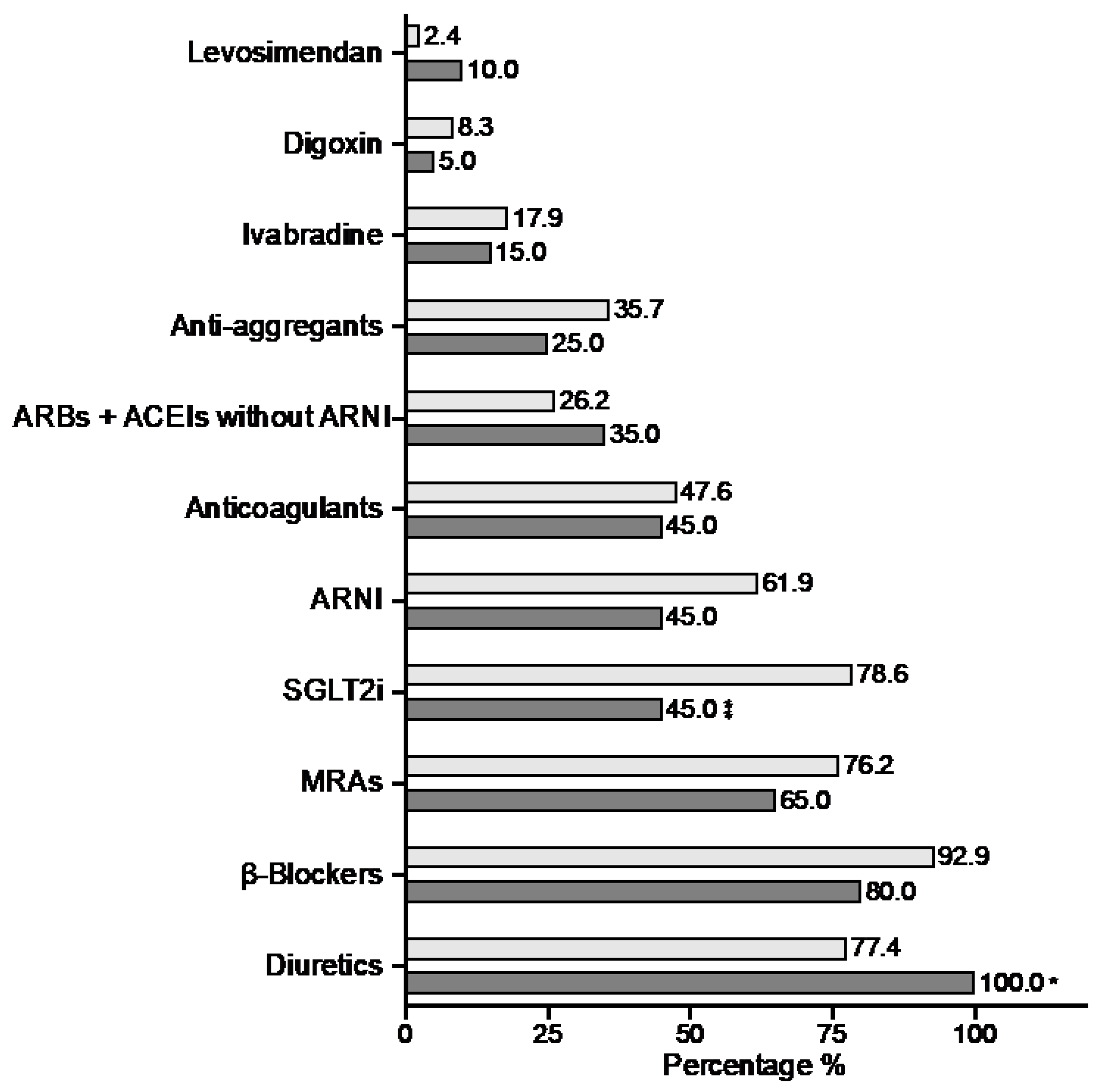

| Pharmacology | ||||

| Anticoagulants [n (%)] | 49 (47.1) | 36 (43.4) | 13 (61.9) | 0.129 |

| Anti-aggregants [n (%)] | 35 (33.7) | 28 (33.7) | 7 (33.3) | 0.972 |

| MRAs [n (%)] | 77 (74) | 61 (73.5) | 16 (76.2) | 0.801 |

| SGLT2i [n (%)] | 75 (72.1) | 62 (74.7) | 13 (61.9) | 0.243 |

| ARBs + ACEIs without ARNI | 29 (27.9) | 25 (30.1) | 4 (19) | 0.312 |

| β-Blockers [n (%)] | 94 (90.4) | 75 (90.4) | 19 (90.5) | 0.987 |

| Diuretics [n (%)] | 85 (81.7) | 66 (79.5) | 19 (90.5) | 0.350 |

| Digoxin [n (%)] | 8 (7.7) | 7 (8.4) | 1 (4.8) | 0.573 |

| Ivabradine [n (%)] | 18 (17.3) | 16 (19.3) | 2 (9.5) | 0.518 |

| Levosimendan [n (%)] | 4 (3.8) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (9.5) | 0.181 |

| ARNI [n (%)] | 61 (58.7) | 51 (61.4) | 10 (47.6) | 0.250 |

| HF readmission | ||||

| Total | No | Yes | p-Value | |

| (n= 104) | (n= 83) | (n= 21) | ||

| Biochemestry | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 113 (45) | 113 (35) | 99 (73) | 0.489 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.49) | 1.2 (0.64) | 0.047 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 66.9 (38) | 68 (35.9) | 54 (37.83) | 0.111 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 25 (16) | 25 (15) | 29 (19) | 0.395 |

| Serum iron level (µg/dL) | 54 (37.8) | 54 (41.5) | 47 (28) | 0.672 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 147.4 (220) | 137.6 (265) | 127 (143) | 0.101 |

| HB (g/dL) | 13.6 (3.6) | 13.7 (3.3) | 13 (4.05) | 0.709 |

| Hct (%) | 41.9 (9.4) | 42.5 (8.9) | 40 (12.8) | 0.755 |

| ProteinBiomarkers | ||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.96 (2.4) | 0.92 (2.64) | 0.99 (2.08) | 0.288 |

| TnI (ng/mL) | 0.04 (0.1) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.1) | 0.893 |

| CK-MB (ng/mL) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.01 (0.75) | 1.05 (0.87) | 0.929 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 6.4 (10.7) | 7.61 (10.96) | 5.08 (5.35) | 0.195 |

| NT-proANP (ng/mL) | 29.7 (10) | 29.69 (9.84) | 28.57 (13.71) | 0.442 |

| GDF-15 (ng/mL) | 3.1 (2.4) | 3 (2.25) | 4.04 (3.23) | 0.072 |

| sST2 (x10 ng/mL) | 3.53 (3.5) | 3.37 (3.05) | 3.98 (3.86) | 0.229 |

| uPAR (ng/mL) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.41) | 3.18 (1.4) | 0.093 |

| FABP4 (ng/mL) | 44.21 (32.6) | 44.36 (33.99) | 52.95 (29.17) | 0.574 |

| MM Biomarkers | ||||

| PTH (pg/mL) | 71 (49.5) | 71 (54) | 71 (55) | 0.156 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.4 (0.8) | 9.4 (0.95) | 9.5 (0.95) | 0.810 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.7 (1) | 3.6 (1) | 3.9 (1.05) | 0.305 |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 24.5 (27.2) | 23 (21.3) | 34 (36) | 0.211 |

| FGF-23 (x103 RU/mL) | 0.36 (0.5) | 0.32 (0.36) | 0.71(1.58) | 0.104 |

| Klotho (pg/mL) | 458.5 (242) | 452 (230) | 529 (278) | 0.135 |

| All-cause death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | p-Value | C-index | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.20 | 1.14-4.22 | 0.018 | 0.58 |

| GDF-15 (ng/mL) | 1.22 | 1.07-1.38 | 0.003 | 0.59 |

| suPAR (ng/mL) | 1.41 | 1.12-1.77 | 0.003 | 0.60 |

| Calcidiol (ng/mL) | 1.02 | 1.01-1.04 | 0.006 | 0.53 |

| FGF-23 (x103 RU/mL) | 2.12 | 1.36-3.33 | 0.001 | 0.53 |

| CKD [n (%)] | 2.40 | 1.02-5.67 | 0.046 | 0.37 |

| HF [n (%)] | 7.38 | 2.47-22.0 | <0.001 | 0.56 |

| NYHA III-IV [n (%)] | 12.0 | 4.58-31.3 | <0.001 | 0.51 |

| Prior coronary revasc. [n (%)] | 3.43 | 1.44-8.15 | 0.005 | 0.40 |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Study Design

4.2. Clinical Outcomes

4.3. Biochemical Analysis

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 25(OH)D ACEI ARB ARNI COPD CKD eGFR FABP4 FGF23 GDF-15 HF HFrEF HFU MM MRA OSA P PTH SLGT2i sST2 STEMI suPAR TnI |

1-25-dihydroxyvitamin D Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Angiotensin Receptor/Neprilysin Inhibitor Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Chronic Kidney Disease estimated Glomerular GiltrationRate Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Growth Differentiation Factor-15 Heart Failure Heart Failure with reduced ejection fraction Heart Failure Unit Mineral Metabolism Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists Obstructive Sleep Apnea Phosphorus Paratohormone Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity 2 ST elevation myocardial infarction soluble urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor. Troponin I |

References

- van Riet, E.E.S.; Hoes, A.W.; Limburg, A.; Landman, M.A.J.; van der Hoeven, H.; Rutten, F.H. Prevalence of unrecognized heart failure in older persons with shortness of breath on exertion. Eur.J.Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart 2007, 93, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, K.; et al. Risk prediction in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and analysis. JACC.Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouwerkerk, W.; Voors, A.A.; Zwinderman, A.H. Factors influencing the predictive power of models for predicting mortality and/or heart failure hospitalization in patients with heart failure. JACC.Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.L.; et al. Role of Biomarkers for the Prevention, Assessment, and Management of Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e1054–e1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, W.C.; et al. Circulating heart failure biomarkers beyond natriuretic peptides: review from the Biomarker Study Group of the Heart Failure Association ( HFA ), European Society of Cardiology ( ESC ). European J of Heart Fail 2021, 23, 1610–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; et al. Heart Failure Drug Treatment—Inertia, Titration, and Discontinuation. JACC: Heart Failure 2023, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, e153–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioncel, O.; et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017, 19, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Harshaw-Ellis, K. Evolving Use of Biomarkers in the Management of Heart Failure. Cardiol Rev 2019, 27, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, E.; et al. The diagnostic accuracy of the natriuretic peptides in heart failure: systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis in the acute care setting. BMJ 2015, 350, h910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.; et al. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology practical guidance on the use of natriuretic peptide concentrations. Eur J Heart Fail 2019, 21, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clerico, A.; Emdin, M. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic relevance of the measurement of cardiac natriuretic peptides: a review. Clin Chem 2004, 50, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamanchi, C.; Alhosaini, H.; Sumida, A.; Runge, M.S. Obesity and natriuretic peptides, BNP and NT-proBNP: mechanisms and diagnostic implications for heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2014, 176, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Tsutamoto, T.; Wada, A.; Hisanaga, T.; Kinoshita, M. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as a biochemical marker of high left ventricular end-diastolic pressure in patients with symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Am Heart J 1998, 135, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, L.; Rocha-Resende, C.; Prabhu, S.D.; Mann, D.L. Reappraising the role of inflammation in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020, 17, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.P.; Kakkar, R.; McCarthy, C.P.; Januzzi, J.L. Inflammation in Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 1324–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bootcov, M.R.; et al. MIC-1, a novel macrophage inhibitory cytokine, is a divergent member of the TGF-beta superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 11514–11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, M.; Nicklin, M.J.H. Interleukin-1 Receptor Cluster: Gene Organization ofIL1R2, IL1R1, IL1RL2(IL-1Rrp2),IL1RL1(T1/ST2), andIL18R1(IL-1Rrp) on Human Chromosome 2q. Genomics 1999, 57, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Insights Into Mechanisms of GDF15 and Receptor GFRAL: Therapeutic Targets. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2020, 31, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawalha, K.; Norgard, N.B.; Drees, B.M.; López-Candales, A. Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF-15), a New Biomarker in Heart Failure Management. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2023, 20, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Figal, D.A.; et al. Soluble ST2, high-sensitivity troponin T- and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: complementary role for risk stratification in acutely decompensated heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2011, 13, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsioupa, M.; et al. Novel Biomarkers and Their Role in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollert, K.C.; Kempf, T.; Wallentin, L. Growth Differentiation Factor 15 as a Biomarker in Cardiovascular Disease. Clin Chem 2017, 63, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaca, M.P.; et al. Growth differentiation factor-15 and risk of recurrent events in patients stabilized after acute coronary syndrome: observations from PROVE IT-TIMI 22. ArteriosclerThrombVasc Biol 2011, 31, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; et al. Growth differentiation factor-15 is associated with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020, 19, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, A.; et al. Circulating GDF-15 levels predict future secondary manifestations of cardiovascular disease explicitly in women but not men with atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol 2017, 241, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopfer, D.W.; Ku, I.A.; Regan, M.; Whooley, M.A. Growth differentiation factor 15 and cardiovascular events in patients with stable ischemic heart disease (The Heart and Soul Study). Am Heart J 2014, 167, 186–192e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahrenberg, R.; et al. The novel biomarker growth differentiation factor 15 in heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2010, 12, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.; et al. Circulating protein biomarkers predict incident hypertensive heart failure independently of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels. ESC Heart Fail 2020, 7, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuster, N.; et al. Multimarker approach including CRP, sST2 and GDF-15 for prognostic stratification in stable heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2020, 7, 2230–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benes, J.; et al. The Role of GDF-15 in Heart Failure Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Can J Cardiol 2019, 35, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouabdallaoui, N.; et al. Growth differentiation factor-15 is not modified by sacubitril/valsartan and is an independent marker of risk in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: the PARADIGM-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2018, 20, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkovic, S.; et al. GDF-15 is a better complimentary marker for risk stratification of arrhythmic death in non-ischaemic, dilated cardiomyopathy than soluble ST2. J Cell Mol Med 2018, 22, 2422–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, E.O.; Shimpo, M.; Hurwitz, S.; Tominaga, S.; Rouleau, J.-L.; Lee, R.T. Identification of serum soluble ST2 receptor as a novel heart failure biomarker. Circulation 2003, 107, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ky, B.; et al. High-sensitivity ST2 for prediction of adverse outcomes in chronic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2011, 4, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupón, J.; et al. Combined use of the novel biomarkers high-sensitivity troponin T and ST2 for heart failure risk stratification vs conventional assessment. Mayo Clin Proc 2013, 88, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, M.; et al. sST2 Predicts Outcome in Chronic Heart Failure Beyond NT-proBNP and High-Sensitivity Troponin T. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Y. Long-Term and Short-Term Prognostic Value of Circulating Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity-2 Concentration in Chronic Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiology 2021, 146, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruson, D.; Lepoutre, T.; Ahn, S.A.; Rousseau, M.F. Increased soluble ST2 is a stronger predictor of long-term cardiovascular death than natriuretic peptides in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol 2014, 172, e250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimo, A.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Soluble Suppression of Tumorigenicity-2 and Prognosis in Acute Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2017, 5, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; et al. Predictors of Long-Term Mortality in Patients With Acute Heart Failure. Int Heart J 2017, 58, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, C.; et al. Soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (sST2) for predicting disease severity or mortality outcomes in cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. IJC Heart & Vasculature 2021, 37, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vark, L.C.; et al. Prognostic Value of Serial ST2 Measurements in Patients With Acute Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017, 70, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, P.; Cunha, F.M.; Ferreira-Coimbra, J.; Barroso, I.; Guimarães, J.-T.; Bettencourt, P. Dynamics of growth differentiation factor 15 in acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2021, 8, 2527–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, J.; et al. A 3-Biomarker 2-Point-Based Risk Stratification Strategy in Acute Heart Failure. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 708890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; et al. Growth differentiation factor-15 combined with N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide increase 1-year prognosis prediction value for patients with acute heart failure: a prospective cohort study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2019, 132, 2278–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Fernández, S.; Mueller, T.; Pascual-Figal, D.; Truong, Q.A.; Januzzi, J.L. Usefulness of soluble concentrations of interleukin family member ST2 as predictor of mortality in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure relative to left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol 2011, 107, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E.D.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Heravi, A.S.; Appel, L.J.; Supplements, C. Vitamin D, Calcium Supplements, and Implications for Cardiovascular Health. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2021, 77, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkner, B.; Keith, S.W.; Gidding, S.S.; Langman, C.B. Fibroblast growth factor-23 is independently associated with cardiac mass in African-American adolescent males. J Am Soc Hypertens 2017, 11, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panwar, B.; et al. Association of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 With Risk of Incident Coronary Heart Disease in Community-Living Adults. JAMA Cardiol 2018, 3, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and the risk of cardiovascular diseases and mortality in the general population: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 989574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Parra, E.; et al. Important abnormalities of bone mineral metabolism are present in patients with coronary artery disease with a mild decrease of the estimated glomerular filtration rate. J.BoneMiner.Metab 2016, 34, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunon, J.; et al. Coexistence of low vitamin D and high fibroblast growth factor-23 plasma levels predicts an adverse outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. PLoS.One. 2014, 9, e95402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; et al. Serum parathyroid hormone and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and risk of incident heart failure: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J.Am.Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e001278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, R.; et al. Relations of serum phosphorus levels to echocardiographic left ventricular mass and incidence of heart failure in the community. Eur.J.Heart Fail. 2010, 12, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnenmars, S.H.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Risk of New Onset Heart Failure With Preserved or Reduced Ejection Fraction: The PREVEND Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e024952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, S.E.; et al. Multi-variable biomarker approach in identifying incident heart failure in chronic kidney disease: results from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-P.; Zeng, R.-X.; He, M.-H.; Lin, S.-S.; Guo, L.-H.; Zhang, M.-Z. Associations Between Serum Soluble α-Klotho and the Prevalence of Specific Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 899307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; et al. Association between serum Klotho concentration and heart failure in adults, a cross-sectional study from NHANES 2007–2016. International Journal of Cardiology 2023, 370, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Wei, N.; Sun, Z.; Gong, Y. Association between serum α-klotho level and the prevalence of heart failure in the general population. Cardiovasc J Afr 2023, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Landaluce, C.; et al. Parathormone levels add prognostic ability to N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in stable coronary patients. ESC Heart Failure 2021, 8, 2713–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallmeyer, A.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 independently predicts adverse outcomes after an acute coronary syndrome. ESC Heart Fail 2024, 11, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borné, Y.; Persson, M.; Melander, O.; Smith, J.G.; Engström, G. Increased plasma level of soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is associated with incidence of heart failure but not atrial fibrillation. Eur J Heart Fail 2014, 16, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, A.; Valdovinos, P.; Lázaro, I.; Bonet, G.; Bardají, A.; Masana, L. Parallel evolution of circulating FABP4 and NT-proBNP in heart failure patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2013, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruson, D.; Lepoutre, T.; Ketelslegers, J.M.; Cumps, J.; Ahn, S.A.; Rousseau, M.F. C-terminal FGF23 is a strong predictor of survival in systolic heart failure. Peptides 2012, 37, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, L.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Is an Independent and Specific Predictor of Mortality in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ.Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfahrt, P.; et al. Association of Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 Levels and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibition in Chronic Systolic Heart Failure. JACC.Heart Fail. 2015, 3, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, A.M.; et al. Long term pronostic value of suPAR in chronic heart failure: reclassification of patients with low MAGGIC score. Clin Chem Lab Med 2021, 59, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, S.S.; et al. Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor Levels and Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure. J Card Fail 2023, 29, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Calvo, R.; et al. Fatty Acid Binding Proteins 3 and 4 Predict Both All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Subjects with Chronic Heart Failure and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, L.; et al. Soluble Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator Receptor Improves Risk Prediction in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2017, 5, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen, A.; et al. Intact fibroblast growth factor 23 levels and outcome prediction in patients with acute heart failure. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 15507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohebi, R.; et al. Biomarker prognostication across Universal Definition of Heart Failure stages. ESC Heart Fail 2022, 9, 3876–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E.; Lee, K.L.; Mark, D.B. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996, 15, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All-cause death | ||||

| Total | No | Yes | p-Value | |

| (n= 104) | (n= 84) | (n= 20) | ||

| Biochemestry | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 113 (45) | 111.5 (45) | 117.5 (49) | 0.954 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 1.5 (1) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 66.9 (38) | 70.3 (36.7) | 46 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 25 (16) | 23.5 (14) | 38.5 (26) | 0.03 |

| Serum iron level (µg/dL) | 54 (37.8) | 54 (39) | 48 (42.5) | 0.615 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 147.4 (220) | 137.5 (231) | 163 (183) | 0.961 |

| HB (g/dL) | 13.6 (3.6) | 13.9 (3.2) | 11.8 (3) | 0.006 |

| Hct (%) | 41.9 (9.4) | 43 (7.9) | 36.9 (9.9) | 0.008 |

| ProteinBiomarkers | ||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.96 (2.4) | 0.9 (2) | 2.6 (4.6) | 0.027 |

| TnI (ng/mL) | 0.04 (0.1) | 0.04 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.834 |

| CK-MB (ng/mL) | 1.1 (0.7) | 0.99 (1.4) | 1.12 (1.4) | 0.091 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 6.4 (10.7) | 6.1 (8.7) | 10.1 (14.5) | 0.029 |

| NT-proANP (ng/mL) | 29.7 (10) | 28.9 (11.4) | 31.8 (6.8) | 0.175 |

| GDF-15 (ng/mL) | 3.1 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.1) | 5 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| sST2 (x10 ng/mL) | 3.53 (3.5) | 3.09 (2.9) | 5 (5.82) | <0.001 |

| suPAR (ng/mL) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.4) | 3.5 (2.1) | 0.004 |

| FABP4 (ng/mL) | 44.21 (32.6) | 43.2 (32.2) | 50 (54.2) | 0.152 |

| MM Biomarkers | ||||

| PTH (pg/mL) | 71 (49.5) | 67.5 (46) | 85 (80) | 0.416 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.4 (0.8) | 9.4 (0.9) | 9.6 (0.6) | 0.048 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.7 (1) | 3.7 (1) | 3.6 (1.3) | 0.948 |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 24.5 (27.2) | 25.5 (26.5) | 19.3 (22.2) | 0.345 |

| FGF-23 (x103 RU/mL) | 0.36 (0.5) | 0.33 (0.4) | 0.90 (1.8) | 0.034 |

| Klotho (pg/mL) | 458.5 (242) | 458.5 (235) | 461 (264) | 0.603 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).