Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

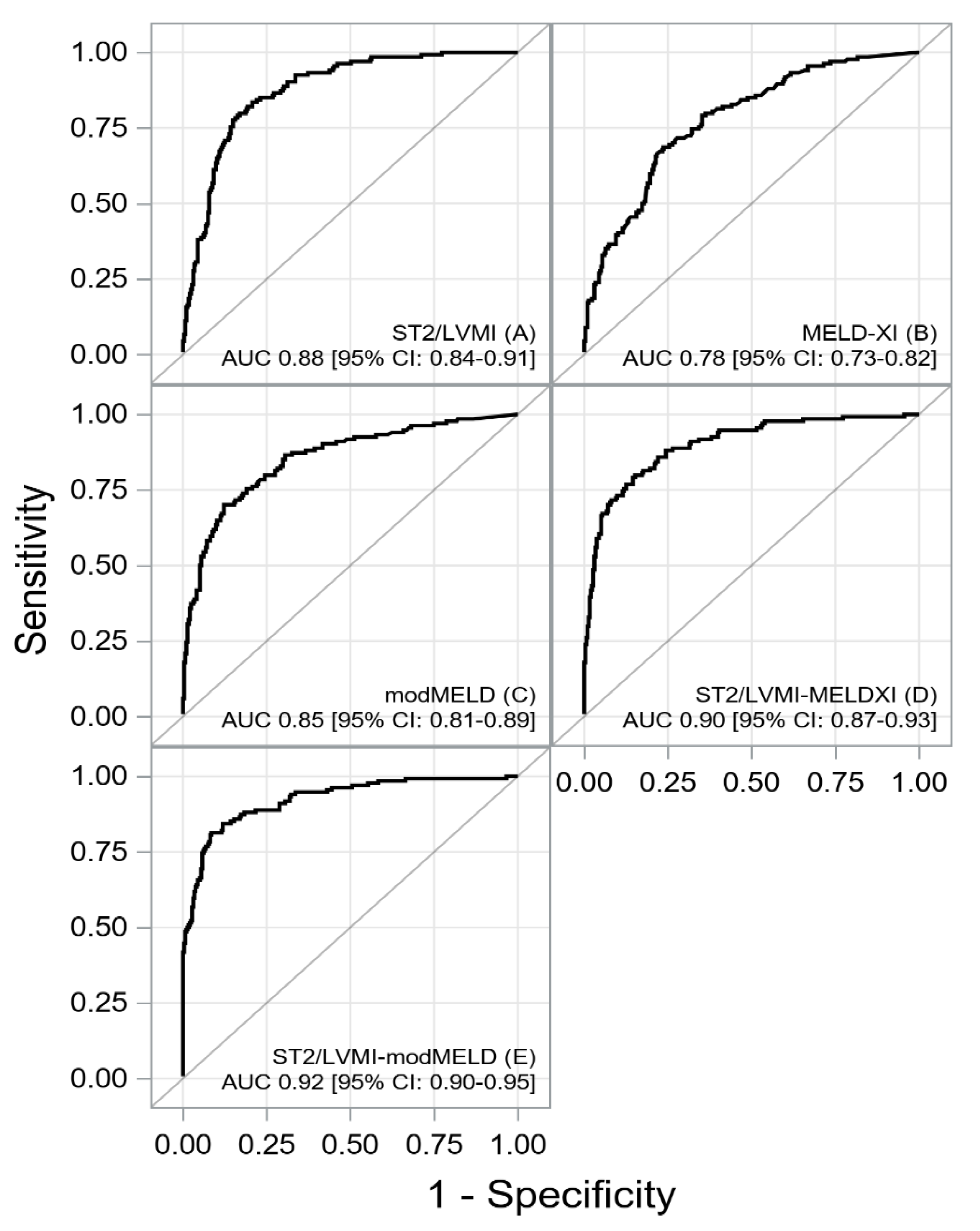

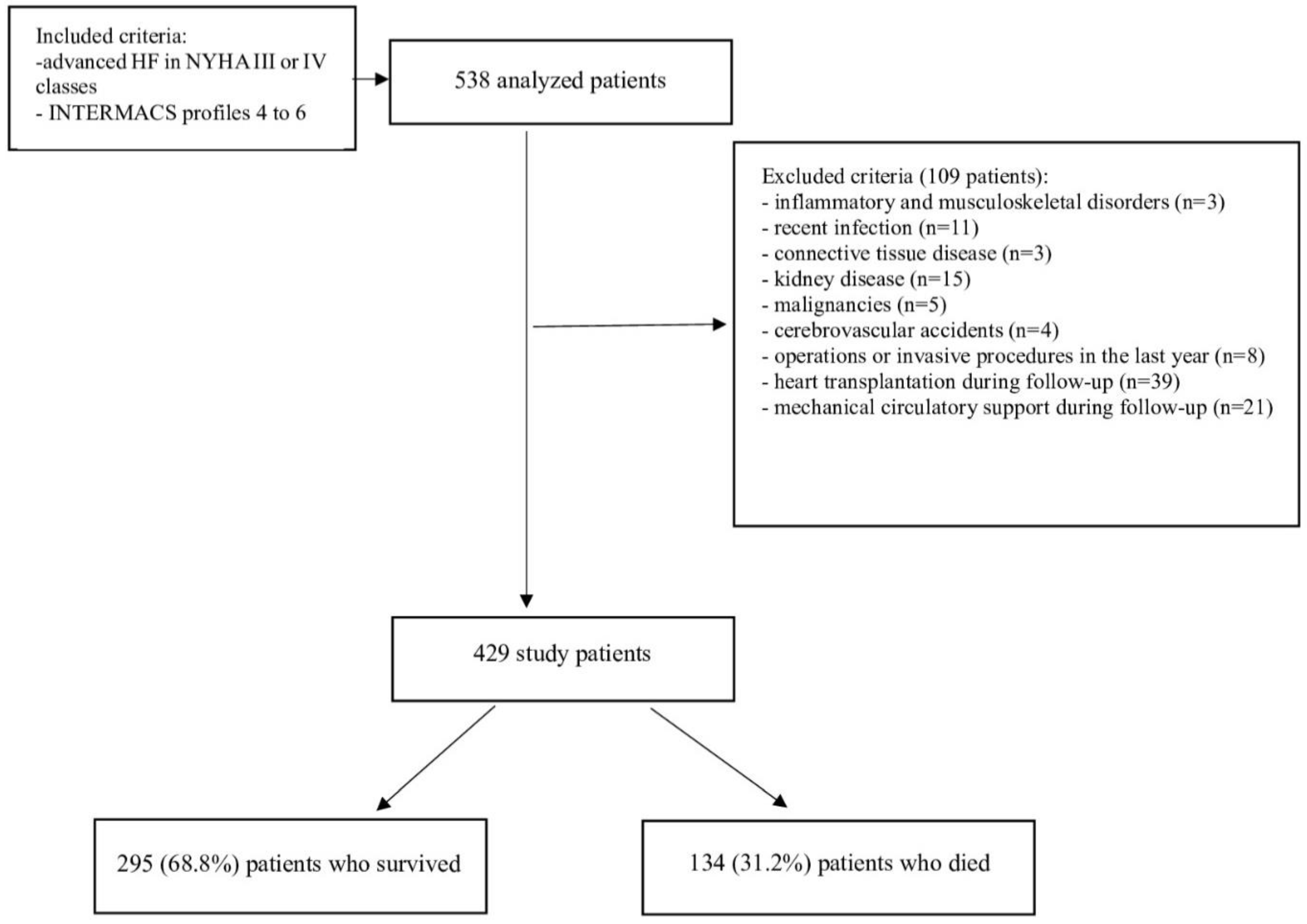

Biomarkers in heart failure (HF) management are critical for enhancing diagnostic accuracy, monitoring therapeutic response and assessing the risk of death. The aim of the study was to assess risk factors for one-year mortality in patients with advanced HF, with particular emphasis on the soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2/left ventricular mass index (sST2/LVMI) ratio, modified Model for End-stage Liver Disease (modMELD) and Model for End-stage Liver Disease excluding INR (MELD-XI). We propectively analyzed 429 adult patients with advanced HF hospitalized between 2018 and 2023. The end-point of the study was defined as all-cause mortality during a one-year follow-up. The median age was 56.0 (50.0–60.0) years; 89.2% were male. During one-year follow-up, 134 (31.2%) patients died. The area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves indicated an excellent prognostic powers of sST2/LVMI-MELDXI (AUC: 0.90 [CI: 0.87-0.93]; sensitivity 80%, and specificity 85%) and sST2/LVMI-modMELD (AUC: 0.92 [95% CI: 0.90-0.95]; sensitivity 81%, and specificity 92%) for assessment of one-year mortality. The multivariable Cox regression model showed that: sST2/LVMI-MELD-XI [HR 2.501 (2.168-2.886) p<0.001], sodium [HR 1.065(1.004-1.130) p=0.036], NT-proBNP [HR 1.004 (1.004-1.007) p=0.008],fibrinogen [HR 1.002 (1.000-1.004) p<0.001], and uric acid [1.001 (1.000-1.002), 0.0426] in first model, and sST2/LVMI-modMELD [HR 2.552 (2.224-2.928) p<0.0001], NT-proBNP [HR 1.005 (1.002-1.008) p=0.002],fibrinogen [HR 1.002 (1.000-1.003) p=0.0099], and uric acid [1.001 (1.000-1.002), 0.0489] in second model were independent risk factors for one- year mortality. The sST2/LVMI-modMELD and sST2/LVMI- MELD-XI ratios are strongly associated with one-year mortality in the patients with advanced HF. Both models have a excellent prognostic powers for an effective separation of one-year survivors from non-survivors. Another independent risk factors for one-year mortality in the analyzed population were higher levels of fibrinogen, uric acid and NT-proBNP, as well as lower sodium levels.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

2.1 Study population

2.2. Echocardiography

2.3 Analyzed biomarkers and scores

2.4 Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Saccaro, L.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Hear. Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciatti, E.; Merlo, A.; Scangiuzzi, C.; Limonta, R.; Gori, M.; D’elia, E.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Emdin, M.; Senni, M. Prognostic Value of sST2 in Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, W.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B.; Siedlecki, Ł.; Gąsior, M. Prognostic scales in advanced heart failure. Pol. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2018, 15, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlken, C.; Screever, E.M.; Suthahar, N.; van der Meer, P.; Westenbrink, B.D.; Coster, J.E.; Van Veldhuisen, D.J.; de Boer, R.A.; Meijers, W.C. Left atrial volume and left ventricular mass indices in heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. ESC Hear. Fail. 2021, 8, 2458–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Huang, Y.; Cai, A.; Yan, M.; Cheng, Q.; Feng, X.; Nie, Z.; Feng, Y. Longitudinal Study of Left Ventricular Mass Index Trajectories and Risk of Mortality in Hypertension: A Cohort Study. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2023, 12, e028568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Xu, M.; Fu, M.; Cui, X.; Lian, Z.; Xin, H.; Zhou, J.; Ge, J. Increased ratio of sST2/LVMI predicted cardiovascular mortality and heart failure rehospitalization in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.A.; Kato, T.S.; Shulman, B.P.; Takayama, H.; Farr, M.; Jorde, U.P.; Mancini, D.M.; Naka, Y.; Schulze, P.C. Liver dysfunction as a predictor of outcomes in patients with advanced heart failure requiring ventricular assist device support: Use of the Model of End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) and MELD eXcluding INR (MELD-XI) scoring system. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2012, 31, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szygula-Jurkiewicz, B.; Szczurek, W.; Skrzypek, M.; Zakliczyński, M.; Siedlecki, Ł.; Przybyłowski, P.; Zembala, M.; Gąsior, M. One year survival of ambulatory patients with the end-stage heart failure: the analysis of prognostic factors. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2017, 127, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2022, 24, 4–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuman, D.M.; Mihas, A.A.; Habib, A.; Gilles, H.S.; Stravitz, R.T.; Sanyal, A.J.; Fisher, R.A. MELD-XI: A rational approach to “sickest first” liver transplantation in cirrhotic patients requiring anticoagulant therapy. Liver Transplant. 2006, 13, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, W.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B.; Zakliczyński, M.; Król, B.; Gąsior, M.; Zembala, M. Prognostic utility of the N terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide and the modified Model for End Stage Liver Disease in patients with end stage heart failure. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2018, 128, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Xu, M.; Fu, M.; Cui, X.; Lian, Z.; Xin, H.; Zhou, J.; Ge, J. Increased ratio of sST2/LVMI predicted cardiovascular mortality and heart failure rehospitalization in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilla, L.; Ibarrola, J.; Arrieta, V.; Garcia-Peña, A.; Martinez-Martinez, E.; Sádaba, R.; Alvarez, V.; Navarro, A.; Fernández-Celis, A.; Gainza, A.; et al. Soluble ST2 promotes oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiac fibroblasts: an in vitro and in vivo study in aortic stenosis. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, C.P.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr. Soluble ST2 in Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2018, 14, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-L.; Chien, K.-L.; Hsu, H.-C.; Su, T.-C.; Chen, M.-F.; Lee, Y.-T. Left ventricular mass and risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause death among ethnic Chinese—The Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011, 149, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, W.; Gąsior, M.; Romuk, E.; Skrzypek, M.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. Usefulness of combining prognostic scores to predict survival in patients with advanced heart failure. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2019, 38, 1224–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szygula-Jurkiewicz, B.; Szczurek, W.; Skrzypek, M.; Zakliczyński, M.; Siedlecki, Ł.; Przybyłowski, P.; Zembala, M.; Gąsior, M. One year survival of ambulatory patients with the end-stage heart failure: the analysis of prognostic factors. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2017, 127, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotou, M.; Suzuki, A.; Shiga, T.; Kikuchi, N.; Hagiwara, N. Implication of modified MELD scores for postdischarge prognosis in hospitalized patients with heart failure. Hear. Vessel. 2022, 38, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, W.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B.; Siedlecki, Ł.; Gąsior, M. Prognostic scales in advanced heart failure. Pol. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2018, 15, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T.; Kim, M.; Farr, M.; Wu, C.; Givens, R.; Collado, E.; Mancini, D.; Schulze, P. Hepatic Dysfunction in Ambulatory Patients with Heart Failure – Application of the MELD Scoring System for Outcome Prediction. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2013, 32, S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefold, J.C.; Filippatos, G.; Hasenfuss, G.; Anker, S.D.; von Haehling, S. Heart failure and kidney dysfunction: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Z.; Ji, K.; Qian, L. Association between fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and prognosis of patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, F.; Gilani, M.; Latif, M.; Sattar, A.; Ashraf, H.; Rafaqat, S. The Role of Coagulation in Heart Failure: A Literature Review. Curr. Hear. Fail. Rep. 2024, 21, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, W.; Song, Y.; Tang, X.-F.; Xu, J.-J.; Wang, H.-H.; Jiang, L.; Chen, J.; Qiao, S.-B.; et al. Relationship between fibrinogen levels and cardiovascular events in patients receiving percutaneous coronary intervention. Chin. Med J. 2019, 132, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar, R.; Fish, R.J.; Casini, A.; Neerman-Arbez, M. Fibrin(ogen) in human disease: both friend and foe. Haematologica 2020, 105, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugno, M.; Mari, D.; Meroni, P.L.; Gronda, E.; Vicari, F.; Frigerio, M.; Coppola, R.; Bottasso, B.; Borghi, M.O.; Gregorini, L. Haemostatic and inflammatory biomarkers in advanced chronic heart failure: role of oral anticoagulants and successful heart transplantation. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 126, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; He, Y. Fibrinogen Level Predicts Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Heart Failure. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Pi, J.; Ma, W.; Gu, W.; Zhang, H.; Xu, A.; Liu, Y.; Shi, T.; Yang, F.; Chen, L. Prognostic value of the fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio (FAR) in patients with chronic heart failure across the different ejection fraction spectrum. Libyan J. Med. 2024, 19, 2309757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Foiles, N.; Chan, C.; Schreiner, P.J.; Liu, K. Elevated fbrinogen levels and subsequent subclinical atherosclerosis: the CARDIA Study. Atherosclerosis. 2009, 202(2), 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, M.; Huang, Y. The inverted U-shaped association between blood fibrinogen and rehospitalization risk in patients with heart failure. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.; Hernandez, M.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Kashani, K.B.; Riaz, I.; Rangaswami, J.; Herzog, E.; Guglin, M.; Krittanawong, C. Hyponatremia in Heart Failure: Pathogenesis and Management. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2019, 15, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H.R.; Charnigo, R.; Guglin, M. Prognostic Significance of Discharge Hyponatremia in Heart Failure Patients With Normal Admission Sodium (from the ESCAPE Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, M.; Hernandez, M.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Kashani, K.B.; Riaz, I.; Rangaswami, J.; Herzog, E.; Guglin, M.; Krittanawong, C. Hyponatremia in Heart Failure: Pathogenesis and Management. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2019, 15, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiade, M.; Rossi, J.S.; Cotts, W.; Shin, D.D.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Piña, I.L.; Fonarow, G.C.; DeMarco, T.; Pauly, D.F.; DiSalvo, T.G.; et al. Characterization and Prognostic Value of Persistent Hyponatremia in Patients With Severe Heart Failure in the ESCAPE Trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S.K.; Shaikh, M.M. Biomarkers in Routine Heart Failure Clinical Care. Card. Fail. Rev. 2019, 5, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, F.; Packer, M.; Coats, A.J.; Fowler, M.B.; Krum, H.; Mohacsi, P.; Rouleau, J.L.; Tendera, M.; Castaigne, A.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Plasma N-Terminal Pro–Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Severe Chronic Congestive Heart Failure. Circulation 2004, 110, 1780–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senni, M.; Lopez-Sendon, J.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Ponikowski, P.; Nkulikiyinka, R.; Freitas, C.; Vlajnic, V.M.; Roessig, L.; Pieske, B. Vericiguat and NT- -proBNP in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: analyses from the VICTORIA trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9(6), 3791–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-N.; Januzzi, J.L. Natriuretic Peptide Testing in Heart Failure. Circulation 2011, 123, 2015–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehner, W.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Zannad, F.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Salsali, A.; Kaempfer, C.; Brueckmann, M.; Pocock, S.J.; et al. Uric acid and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition with empagliflozin in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the EMPEROR-reduced trial. Eur. Hear. J. 2022, 43, 3435–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.; Guo, M.; Pan, D.; Chen, P.; Chen, Z.; Gao, J.; Yu, Y.; Shi, D.; Du, J. Serum Uric Acid and Risk of Chronic Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 785327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. Uric Acid Is a Biomarker of Oxidative Stress in the Failing Heart: Lessons Learned from Trials With Allopurinol and SGLT2 Inhibitors. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Rosticci, M.; Parini, A.; Baronio, C.; D’addato, S.; Borghi, C. Serum uric acid is inversely proportional to estimated stroke volume and cardiac output in a large sample of pharmacologically untreated subjects: data from the Brisighella Heart Study. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2013, 9, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.-H.; Park, S.-K.; Lee, I.-K.; Johnson, R.J. Uric Acid–Induced C-Reactive Protein Expression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 3553–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Din, U.A.S.; Salem, M.M.; Abdulazim, D.O. Uric acid in the pathogenesis of metabolic, renal, and cardiovascular diseases: A review. Journal of Advanced Research 2016, 8, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Node, K.; Kobayashi, Y. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: A clinical review. J. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehner, W.; Landmesser, U. Xanthine Oxidase and Uric Acid in Cardiovascular Disease: Clinical Impact and Therapeutic Options. Semin. Nephrol. 2011, 31, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W. High Uric Acid Inhibits Cardiomyocyte Viability Through the ERK/P38 Pathway via Oxidative Stress. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 45, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumrić, M.; A Borovac, J.; Kurir, T.T.; Božić, J. Clinical Implications of Uric Acid in Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review. Life 2021, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-A.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Johnson, R.J.; Kang, D.-H. Oxidative stress with an activation of the renin–angiotensin system in human vascular endothelial cells as a novel mechanism of uric acid-induced endothelial dysfunction. J. Hypertens. 2010, 28, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Survival N=295 |

Nonsurvival N=134 |

P | |

| Age, years | 56 (50.0 - 60.0) | 55 (50.0 - 60.0) | 0.6835 |

| Male, n (%) | 263 (89.2) | 113 (84.3) | 0.1593 |

| Ischemic etiology of HF (%) HF, n (%) |

191 (64.7) | 89 (66.4) | 0.736 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.1 (23.0 - 29.7) | 25.6 (23.2 - 28.2) | 0,1094 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 146 (49.5) | 62 (46.3) | 0.5359 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 152 (51.5) | 82 (61.2) | 0.0620 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 198 (67.1) | 79 (59.0) | 0.1014 |

| Persistent AF, n (%) | 132 (44.7) | 61 (45.5) | 0.8809 |

| WBC, x 109/l | 7.3 (6.0 - 8.6) | 7.4 (6.2 - 8.7) | 0.4293 |

| Hemoglobin, mmol/l | 8.8 (8.2 - 9.6) | 8.8 (8.1 - 9.7) | 0.902 |

| Creatinine, umol/l | 103.0 (90.0 - 119.0) | 126.0 (108.0 - 138.0) | <0.0001* |

| Total bilirubin, µmol/l | 16.9 (11.7 - 22.8) | 22.9 (15.9 - 32.3) | <0.0001* |

| Albumin, g/l | 43.0 (41.0 - 46.0) | 37.0 (35.0 - 41.0) | <0.0001* |

| Uric acid, µmol/l | 419.0 (343.0 - 498.0) | 502.0 (430.0 - 599.0) | <0.0001* |

| Urea, µmol/l | 7.7 (5.9 - 11.7) | 9.10 (6.3 - 12.8) | 0.0485* |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dl | 369.0 (292.0 - 441.0) | 412.5 (341.0 - 537.0) | <0.0001* |

| AST, U/l | 26.0 (20.0 - 31.0) | 26.0 (21.0 - 34.0) | 0.4975 |

| ALT, U/l | 23.0 (17.0 - 33.0) | 22.00 (16.0 - 31.0) | 0.5767 |

| ALP, U/l | 77.0 (57.0 - 101.0) | 83.5 (65.0 - 109.0) | 0.0447* |

| GGTP, U/l | 62.0 (33.0 - 112.0) | 91.0 (48.0 - 144.0) | 0.0001* |

| Cholesterol, mmol/l | 4.4 (3.8 - 4.9) | 4.5 (4.1 - 4.9) | 02376 |

| hs-CRP, mg/l | 3.0 (1.5 - 5.6) | 6.0 (3.8 - 8.5) | <0.0001* |

| Sodium, mmol/l | 139.0 (138.0 - 141.0) | 137.0 (135.0 - 139.0) | <0.0001* |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 3564.0 (1761.0-6682.0) | 5526.0 (2517.0-7645.0) | 0.0006* |

| ST2, ng/ml | 35.6 (29.8 - 45.4) | 89.3 (70.2 - 101.3) | <0.0001* |

| VO2max, mL/kg/min | 11.0 (10.1 - 11.8) | 11.2 (10.3 - 12.0) | 0.0618 |

| CI, l/min/m2 | 1.9 (1.7 - 1.9) | 1.9 (1.7 - 2.1) | 0.7124 |

| PVR, Wood units | 2.0 (1.6 - 2.4) | 2.1 (1.5 - 2.9) | 0.2234 |

| LA, mm | 52.0 (47.0 - 56.0) | 53.0 (47.0 - 57.0) | 0.202 |

| RVEDd, mm | 34.0 (30.0 - 42.0) | 34.0 (30.0 - 40.0) | 0,8325 |

| LVEDd, mm | 73.0 (68.0 - 78.0) | 75.5 (70.0 - 82.0) | 0.0014* |

| IVSd, mm | 10.0 (9.0 - 11.0) | 10.0 (9.0 - 11.0) | 0.2246 |

| PWTd, mm | 10.0 (9.0 - 11.0) | 10.0 (9.0 - 11.0) | 0.2405 |

| LVEF, % | 18.0 (15.0 - 21.0) | 18.0 (15.0 - 20.0) | 0.1898 |

| LVMI, g/m2 | 174.0 (149.9 - 199.2) | 189.5 (160.5 - 226.5) | 0.0002* |

| Cardiac medication on admission, n (%) | |||

| B-blockers, n (%) | 273 (92.5) | 127 (94.8) | 0.3931 |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 272 (92.2) | 126 (94) | 0.4983 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 295 (100.0) | 134 (100.0) | 1.00 |

| MRA, n (%) | 282 (95.6) | 124 (92.5) | 0.1928 |

| Flosins, n (%) | 155 (52.5) | 68 (50.7) | 0.73 |

| ICD/CRT-D, n (%) | 295 (100.0) | 134 (100.0) | 1.00 |

| Statins, n (%) | 214 (72.5) | 93 (69.4) | 0.5041 |

| Other parameters | |||

| modMELD | 9.0 (7.5 - 11.1) | 14.2 (11.7 - 16.9) | <0.0001* |

| MELD-XI | 12.0 (10.5 - 13.9) | 14.8 (13.3 - 17.1) | <0.0001* |

| ST2/LVMI | 0.22 (0.16 - 0.29) | 0.45 (0.34 - 0.58) | <0.0001* |

| ST2/LVMI-MELD-XI | 4.1 (3.6 - 4.7) | 5.9 (5.3 - 6.8) | <0.0001* |

| ST2/LVMI-modMELD | 2.9 (2.4 - 3.5) | 4.9 (4.2 - 5.7) | <0.0001* |

| Univariable data | Multivariable data Model 1 |

Multivariable data Model 2 |

||||

| Parameter | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| CRP (+) | 1.018 [1.001-1.035] | 0.0353 | ||||

| Fibrinogen (+) | 1.004 [1.003-1.005] | <0.001 | 1.002 [1.001-1.004] | <0.001 | 1.002 [1.000-1.003] | 0.0099 |

| ALP (+) | 1.005 [1.000-1.010] | 0.0472 | ||||

| GGTP (+) | 1.006[1.003-1.009] | <0.001 | ||||

| Uric acid (+) | 1.003 [1.002-1.004] | <0.001 | 1.001 [1.000-1.002] | 0.0426 | 1.001 [1.000-1.002] | 0.0489 |

| Urea (+) | 1.023 [0.996-1.051] | 0.0980 | ||||

| NT-proBNP (a) | 1.006[1.003-1.009] | <0.001 | 1.004 [1.004-1.007] | 0.0081 | 1.005 [1.002-1.008] | 0.0020 |

| Sodium (-) | 1.164 [1.103-1.229] | <0.001 | 1.065 [1.004-1.130] | 0.0360 | ||

| ST2/LVMI-MELD-XI (+) | 2.718 [2.369-3.118] | <0.001 | 2.501 [2.168-2.886] | <0.001 | ||

| ST2/LVMI-modMELD (+) | 2.718 [2.389-3.092] | <0.001 | 2.552 [2.224-2.928] | <0.0001 | ||

| AUC [±95 CI] |

Cut-off | Sensitivity [±95 CI] |

Specificity [±95 CI] |

PPV [±95 CI] |

NPV [±95 CI] |

Accuracy | |

| sST2/LVMI | 0.88 [0.84-0.91] | ≥0.306 | 0.84 [0.76-0.89] | 0.79 [0.74-0.84] | 0.65 [0.57-0.72] | 0.91 [0.87-0.94] | 0.81 [0.77-0.84] |

| MELD-XI | 0.78 [0.73-0.83] | ≥13.96 | 0.69 [0.60-0.76] | 0.76 [0.71-0.81] | 0.57 [0.49-0.65] | 0.84 [0.79-0.88] | 0.74 [0.69-[0.78] |

| ModMELD | 0.85 [0.81-0.89] | ≥12.55 | 0.70 [0.62-0.78] | 0.88 [0.84-0.91] | 0.72 [0.64-0.80] | 0.87 [0.82-0.90] | 0.82 [0.78-0.86] |

| sST2/LVMI-MELDXI | 0.90 [0.87-0.93] | ≥5.07 | 0.80 [0.72-0.86] | 0.85 [0.80-0.89] | 0.70 [0.62-0.78] | 0.90 [0.86-0.93] | 0.83 [0.79-0.87] |

| sST2/LVMI-modMELD | 0.92 [0.89-0.95] | ≥4.04 | 0.81 [0.74-0.88] | 0.92 [0.88-0.94] | 0.81 [0.74-0.88] | 0.92 [0.88-0.944] | 0.88 [0.85-0.91] |

| ST2/LVMI- modMELD, AUC [±95 CI]1 | P | |

| modMELD, AUC [±95 CI] | 0.0214 [0.00251-0.0402] | 0.0263 |

| LVMI/ST2, AUC [±95 CI] | 0.0862 [0.0540-0.1183] | 0.0001 |

| ST2/LVMI- MELD-XI AUC [±95 CI]1 | P | |

| MELD-XI, AUC [±95 CI] | 0.0486 [0.0213-0.0760] | 0.0005 |

| LVMI/ST2 AUC [±95 CI] | 0.0456 [0.0157-0.0755] | 0.0028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).