1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease has been the leading cause of death worldwide. The risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) rises steadily with age, with individuals aged 65 and older representing over half of all CVD-related hospitalizations and procedures in the U.S., along with approximately 80% of CVD deaths [

1].

In fact, the mortality rate following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in this population is ten times higher than in those aged 65 or younger [

2]. The use of primary PCI for STEMI is nowadays considered as the firstline treatment, and is associated with a reduction in mortality [

3]. Although cardiovascular disease (CVD) is highly prevalent and associated with significant morbidity and mortality in older adults, the majority of randomized clinical trials have either systematically excluded this population or included only healthier older individuals with minimal comorbidities or functional limitations [

4,

5]. Contrast-induced AKI is a significant complication that can occur in STEMI patients undergoing pPCI . The occurrence of CIN has been linked to prolonged hospitalization, the need for renal replacement therapy, major cardiovascular events, and even mortality [

6]. Therefore, predicting CIN using easily calculated markers before the angiographic procedure is essential for identifying high-risk patients and implementing preventive measures. Several risk factors have been associated with CIN development, including female gender, advanced age, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, elevated baseline creatinine levels, lower total bilirubin levels, anemia, the volume of contrast media used, and the administration of nephrotoxic medications [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Although the exact mechanisms underlying contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) are not fully understood, researches have confirmed that several pathways - including nephrotoxic effects, inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species generation, and renal medullary hypoxia likely play a role in its occurrence. Consequently, early and precise risk stratification, along with tailored preventive measures, holds significant clinical importance [

11]. Recent studies have proposed two new composite indices, the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), which serve as valuable tools for assessing both inflammatory and immune responses simultaneously [

12,

13]. While these inflammatory markers consistently correlate with unfavorable cancer outcomes, they also show remarkable predictive capacity in cardiovascular conditions. Recent cardiovascular studies particularly highlight their association with poor prognosis, typically measured as composite endpoints. Of clinical significance, SIRI proved to be a robust, independent prognostic indicator for MACE in acute coronary syndrome undergoing PCI [

14,

15]. Currently, no studies have investigated whether SIRI and SII serve as independent risk factors for contrast-induced acute kidney injury development in elderly ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between SII, SIRI, and the development of contrast-induced AKI in this specific patient population.

2. Materials and Methods

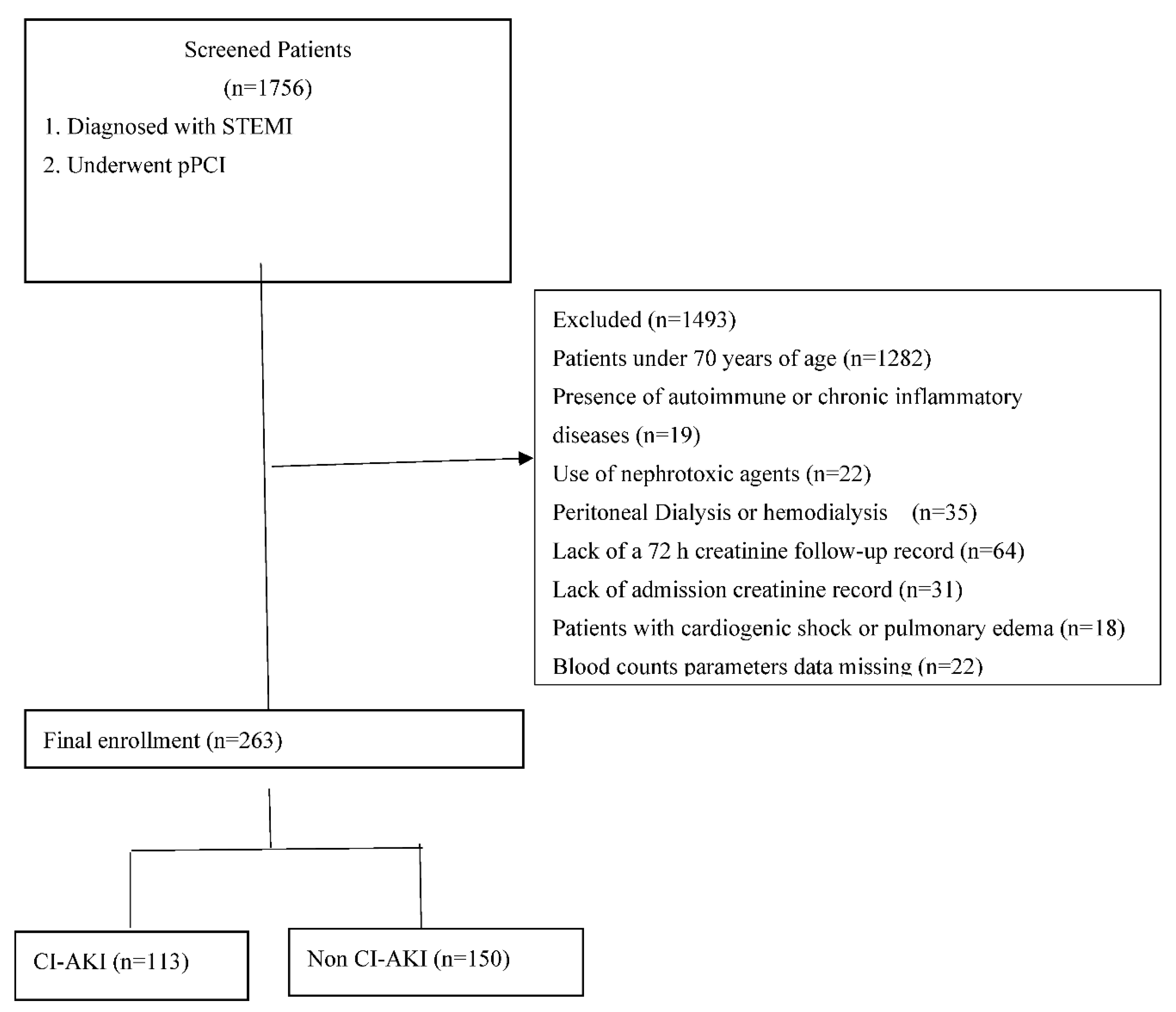

This is a single-center, retrospective, and observational study that consecutively included 1756 patients with a history of STEMI who underwent PCI from November 3, 2020 to September 1, 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age≥ 70 years; (2) patients diagnosed with STEMI underwent PCI. The exclusion criteria included patients aged <70 years, presence outoimmune or chronic infammatory diseases, use of nephrotoxic agents, peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis, lack of a 72 hours creatinine follow-up record, lack of admission creatinine record, cardiogenic shock or pulmonary edema, and missing laboratory data. A total of 263 elderly patients aged seventy years and above with STEMI who underwent pPCI were included (

Figure 1).

This study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital’s ethical review board.

In this study, baseline clinical data from the hospital information system were collected for all patients, including age, sex and related risk factors (e.g., coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, atrial fibrillation and hyperlipidemia). Venous blood samples were collected on admission to the hospital and during hospitalization. Complete blood count was measured by Mindray BC6800 plus autoanalyzer (Mindray, Chenzhen, China). Biochemical measurement was performed by a clinical biochemistry analyzer (Beckman AU5800, Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Brea, CA, US) in the hospital biochemistry laboratory.

STEMI was defined according to ESC guidelines for STEMI criteria and management [

16]. Patients underwent coronary angiography with subsequent percutaneous coronary intervention within 90 min of admission to the intensive care unit.

Hypertension was defined by a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or a history of hypertension or use of antihypertensive drugs [

17].

Smoking status was classified as never smoker (defined as smoking less than 100 cigarettes in life), former smoker (defined as smoking more than 100 cigarettes in life and smoking not at all now) and now smoker (defined as smoking moth than 100 cigarettes in life and smoking some days or every day). Diabetes was defined by a fasting blood glucose >126 mg/dLol/L, or a previous history of diabetes or use of hypoglycemic drugs [

18]. Coronary heart disease was defined by a previous history of coronary heart disease. Atrial fibrillation was defined by a previous history of atrial fibrillation or diagnosis with atrial fibrillation by electrocardiography. Congestive heart failure (CHF) was identified as a known heart failure symptoms affirmed with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Patients with previous ischemic strokes or transient ischemic attacks were defined as having a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Hyperlipidemia was identified as total cholesterol higher than 200 mg/dL and/or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol higher than 130 mg/dL.

Contrast-Induced Nephropathy (CIN) is defined as an iatrogenic complication characterized by either an absolute increase in serum creatinine ≥0.5 mg/dL or a relative increase ≥25% within 48-72 hours following intravascular administration of iodinated contrast media, persisting for 2-5 days in the absence of other identifiable causes, according to the KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Kidney Injury [

19]. The SII index was calculated using the following formula: SII = (peripheral platelet counts × neutrophil counts/ lymphocyte counts)/1000. The systemic inflammation response index was defined as follows: neutrophil count × monocyte/lymphocyte count [

12,

20].

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Distribution of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The data for continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were compared between groups using independent sample T-test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square or Fisher Exact test. Univariable logistic regression analysis was used to detect the association of variables with CI-AKI in elderly patients with STEMI. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed with clinically relevant variables with a P < .05 in univariable logistic regression analysis.

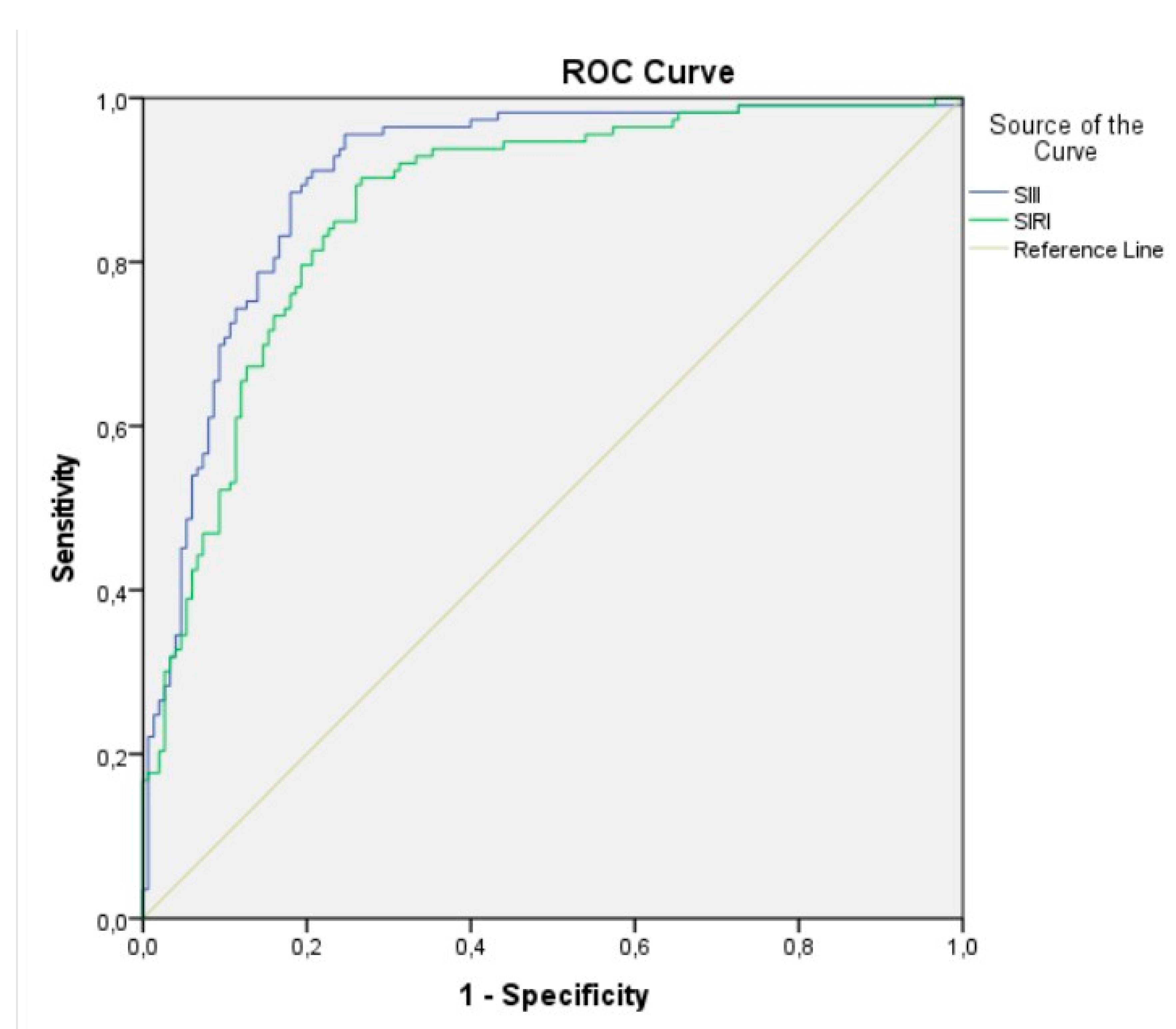

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to compare the performance and predictive accuracy of the SII and SIRI score for CI-AKI. The optimal test cut-off point was established by calculating Youden’s index. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

This clinical study included a total of 263 elderly patients aged seventy years and above with STEMI who underwent pPCI. Contrast induced-AKI developed in 113 patients (43%) after the pPCI procedure in elderly patients with STEMI.

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic and clinical characteristics of CI-AKI (+) and CI-AKI (-) patients. Contrast induced AKI (+) elderly patients were older than the CI-AKI (-) group (78.7±6.3 vs 76.6±5.9 years; p = 0.005). Likewise, elderly patients with CI-AKI (+) had higher frequencies of smoking, Killip>1, CHF, anterior STEMI, bleeding and vasopressor use compared with CI-AKI (-). The number of elderly patients with DM, HT, AF, previous history of CAD, COPD, periferal artery disease and hyperlipidemia was similar between the groups.

Table 2 demonstrates baseline laboratory measurements of the sample. Considering biochemical parameters, we could not reach any significant differences between the groups in hemoglobin, glucose at admission, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, triglyceride, C-reactive protein at admission, serum creatinine at admission, and monocyte counts (p >0.05). However, the patients developing CI-AKI had higher levels of maximum serum creatinine ( 2.23±1.32 vs 1.39±1.1 mg/dL, p<0.001), maximum CRP (90.37±69.3 vs 66.94±50, p <0.001), peak hs troponin I (10100±6827 vs 4529±3562, p=0.003). In addition, the patients with CI-AKI had higher neutrophil ( 10.81±4.14 vs 7.62±2.8, p<0.001) and platelet counts (286.93±81.8 vs 239.65±73, p<0.001), and had lower levels lymphocyte counts (1.07±0.38 vs 2.27±1.0, p<0.001) compared with those without CI-AKI. Likewise, among the markers calculated from hematological parameters, SII and SIRI was higher in patients who developed CI-AKI compared to those who did not (3252.35±225.7 vs 1097.95±99.1, p<0.001; 12.1±4.54 vs 2.86±1.48, p<0.006, respectively).

We evaluated the roles of some CI-AKI risk factors using multivariate analysis in elderly patients with STEMI underwent pPCI. In univariate analysis, we found age, female sex, maximum hsCRP, maximum hsTnI, Killip>1, glucose at admission, anterior MI, SII and SIRI to be associated with CI-AKI development. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that only SII score (OR: 1.008, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.003–1.020, p<0.001) and SIRI (OR: 1.231, 95% CI: 1.057–1.433, p = 0.008) were independent predictors of CI-AKI development (

Table 3).

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to evaluate the predictive level of the SII index and SIRI for CI-AKI. ROC analysis showed that the best cutoff value for the SII index to predict the development of CI-AKI, with 79% sensitivity and 84% specificity (area under ROC curve = 0.903 (95% CI: 0.865– 0.941), p < 0.001), was 1703. The best cutoff value of 3.65 for the SIRI predicted the development of CI-AKI, with a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 78% (area under ROC curve = 0.8670 (95% CI: 0.823–0.911), p< 0.001) (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the relationship between SIRI, SII, and the development of CI-AKI after pPCI in elderly STEMI patients. Our study showed the predictive roles of the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Systemic Inflammation Response Index, a novel inflammatory markers, for contrast-induced acute kidney injury following primary percutaneous coronary intervention in elderly patients with STEMI. In elderly patients with STEMI, our study findings demonstrated that both SII index and SIRI exhibit high sensitivity and specificity in predicting CI-AKI development after pPCI (79% sensitivity and 84% specificity for SII index, 82% sensitivity and 78% specificity for SIRI).

Among STEMI patients who underwent pPCI, the rate of CI-AKI development varies from 15% to 35%, with no significant age-related differences, and the incidence exceeds 50% among high-risk populations, particularly elderly patients and those with comorbid conditions including diabetes mellitus, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease [

21,

22,

23]. As global population aging accelerates, contrast-enhanced procedures are being increasingly performed in elderly patients worldwide. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI), a common complication of PCI, represents a leading cause of hospital-acquired renal impairment. The adverse clinical outcomes associated with CI-AKI, including prolonged hospitalization and elevated treatment costs, have significantly constrained the use of contrast angiography, particularly in high-risk STEMI patients [

24,

25]. Although the precise pathophysiology of CI-AKI remains incompletely elucidated, current evidence confirms its association with multiple pathogenic factors including direct nephrotoxicity, systemic inflammatory activation, oxidative stress pathways, excessive reactive oxygen species production, and renal medullary ischemia [

25,

26]. In addition to the previously mentioned underlying mechanisms in elderly patients, substantial loss of nephrons caused by advanced age, increases in vascular stiffness, and decreases in vascular endothelial function may lead to CI-AKI [

27,

28,

29].

Numerous investigations have demonstrated that elevated inflammatory activity triggers neutrophil-mediated renal tubular injury. This process is exacerbated by massive anti-inflammatory factor release, which induces lymphocyte apoptosis while simultaneously compromising the body's immune defenses and antioxidant capacity, ultimately resulting in endothelial dysfunction [

30,

31,

32]. Platelet activation contributes significantly to inflammatory processes through the secretion of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines. Such excessive inflammatory responses may induce systemic microcirculatory disturbances, accelerated platelet consumption, and impaired renal perfusion with consequent hypoxia. These findings collectively suggest that elevated SII index and SIRI levels potentially promote CI-AKI pathogenesis through dual mechanisms: sustained inflammatory cascades and dysregulated coagulation pathways [

33,

34].

Both the SII index and SIRI have been extensively investigated in various cardiovascular disease. Bağcı et al. demonstrated in STEMI patients (mean age 66 years) that the preprocedurally calculated SII index serves as an independent predictor of CI-AKI development following pPCI [

35]. In another study, Marci et al. reported a significant association between elevated SII index and SIRI values with increased mortality rates in STEMI patients [

13]. The literature reveals no established predictive threshold for SII, with studies reporting varying cut-off values. This discrepancy underscores the necessity for standardized large-scale investigations. Notably, Yang et al. demonstrated that elevated SII levels (>694.3 × 10⁹/L) correlate with adverse cardiovascular outcomes post-PCI in CAD patients [

36].

Our study demonstrated a 42% incidence of CI-AKI following pPCI in STEMI patients aged over 70 years. Patients who developed CI-AKI had significantly higher comorbidity burden compared to those without CI-AKI. In STEMI as a manifestation of acute coronary syndrome, inflammatory processes secondary to coronary plaque rupture play a fundamental role. Neutrophils, platelets, monocytes, and lymphocytes are known to be key mediators in this process, all of which can be easily and inexpensively measured via complete blood count. In our patient cohort, neutrophil and platelet counts were higher in the group that developed CI-AKI compared to those who did not, whereas lymphocyte counts were lower. Monocyte counts showed no significant difference between the groups. Both the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) and the Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI), calculated from neutrophil, platelet, monocyte, and lymphocyte values, were significantly elevated in the CI-AKI group. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that both SII index and SIRI independently predict the development of CI-AKI following pPCI in elderly patients with STEMI. Based on our findings, we speculate that calculating pre-procedural SII and SIRI values in elderly patients diagnosed with STEMI may allow for the early identification of those at high risk for CI-AKI after pPCI. This, in turn, could facilitate timely interventions, potentially shortening hospital stays and even contributing to a reduction in mortality. The SII index and SIRI may offer a more comprehensive and reliable reflection of the immune system's overall status in cardiovascular disease compared to NLR and PLR. In this study, we employed a combined index approach and demonstrated that both SII and SIRI correlate with development of CI-AKI after pPCI in elderly STEMI patients. Notably, SII index and SIRI emerged as a stronger predictor of CI-AKI in elderly STEMI patients. Specifically, when SII index and SIRI values exceeded 1703 and 3.65 respectively , the risk of CI-AKI after pPCI in elderly STEMI patients showed a statistically significant increase. This study has some limitations. Firstly, this was a single-center retrospective observational study, and there may be selection bias in including research subjects. Secondly, patients were not stratified by age for further analysis. Finally, the sample size of this study needs to be increased. Despite these limitations, our study has identified SII index and SIRI as novel and robust inflammatory markers for predicting CI-AKI development after PCI in elderly STEMI patients, while laying the groundwork for future research to validate and expand upon these findings. In conclusion, the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Systemic Inflammation Response Index have a certain predictive value in evaluating the occurrence of CI-AKI after pPCI in elderly patients with STEMI. This method has the advantages of convenient detection and low cost, and has a good application prospect in predicting CI-AKI after PCI in elderly patients with STEMI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.Y. and E.K.; methodology, S.S.Y; validation, E.D.; investigation, G.C. and M.A. (Murat Avsar); resources, B.B., O.S., M.A.(Mujdat Aktas), S.S.Y., E.K, E.D., G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.Y and B.B; writing—review and editing, G.C., M.A. (Murat Avsar), S.S.Y., E.K., E.D., O.S., M.A. (Mujdat Aktas), B.B., and K.K.; supervision, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Prof. Dr. Cemil Tascioglu City Hospital of University of Health Science (approved date/number: 31.12.2024/E-486707771-770-264016808).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SII index |

Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index |

| SIRI |

Systemic Inflammation Response Index |

| CI-AKI |

Contrast induced acute kidney injury |

| STEMI |

ST- ST-segment elevation myocardial |

| pPCI |

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention |

References

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. On behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016, 133, 338–360.

- Alessandra, M. Campos, Andrea Placido-Sposito, et al. ST-elevation myocardial infarction risk in the very elderly. BBA Clinical 2016, 6, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez B, James S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2021; 42:1289-1367.

- Herrera AP, Snipes SA, et al. Disparate inclusion of older adults in clinical trials: priorities and opportunities for policy and practice change. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 suppl 1:105-112.

- Heiat A, Gross CP, et al. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162, 1682–1688.

- Gruberg L, Mintz Gary S, et al. The prognostic implications of further renal function deterioration within 48 h of interventional coronary procedures in patients with pre-existent chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 36, 1542–1548. [CrossRef]

- Mehran R, Nikolsky E. Contrast-induced nephropathy: definition, epidemiology, and patients at risk. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 11–15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucelikova T, Dangas G, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv. 2008, 71, 62–72. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Y, Qiu H, et al. Predictive value of inflammatory factors on contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients who underwent an emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Cardiol. 2017, 40, 719–725. [CrossRef]

- Shacham Y, Gal-Oz A, et al. Association of admission hemoglobin levels and acute kidney injury among myocardial infarction patients treated with primary percutaneous intervention. Can J Cardiol. 2015, 31, 50–55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehran R, Dangas GD, et al. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 2146–2155. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q, Zhuang, L, et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer 2016, 122: 2158–2167.

- Federica Marchi, Nataliya Pylypiv, et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Systemic Inflammatory Response Index as Predictors of Mortality in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13:1256-1267.

- Han, K, Shi, D, et al. Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory response index in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 1667–1677. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y, Chen, H. A nonlinear relationship between systemic inflammation response index and short-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A retrospective study from MIMIC-IV. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1208171.

- Thygesen, K, Alpert, J.S., et al. Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2018, 138: 618-651.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, et al. 2017 ACC/ AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018, 71:127-248.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, et al. Defnition of metabolic syndrome: report of the national heart, lung, and blood institute/American heart association conference on scientifc issues related to defnition. Circulation. 2004, 109, 433–438. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaka Y, Hayashi H, et al. Guideline on the use of iodinated contrast media in patients with kidney disease 2018. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020, 24, 1–44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu B, Yang XR, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 6212–6222. [CrossRef]

- Silvain J, Nguyen LS, et al. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and mortality in ST elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2018, 104, 767–772. [CrossRef]

- Parfrey, P. The clinical epidemiology of contrast-induced nephropathy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005, 28, S3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rear R, Bell RM, Hausenloy DJ. Contrast-induced nephropathy following angiography and cardiac interventions. Heart. 2016, 102, 638–48. [CrossRef]

- Fähling M, Seeliger E, et al. Understanding and preventing contrast-induced acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017, 13, 169–180. [CrossRef]

- Hossain MA, Costanzo E, Cosentino J, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy: pathophysiology, risk factors, and prevention. Saudi j Kidney Dis Transplantation. 2018, 29, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Qiu H, Zhu Y, Shen G, Wang Z, Li W. A predictive model for contrast-Induced Acute kidney Injury after Percutaneous Coronary intervention in Elderly patients with ST-Segment Elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Interv Aging. 2023, 18, 453–465. [CrossRef]

- Stojanović SD, Fiedler J, et al. Senescence-induced inflammation: an important player and key therapeutic target in atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 2983–2996. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia G, Aroor AR, et al. Endothelial cell senescence in aging-related vascular dysfunction. Biochimica et biophysica acta Mol dis. 2019, 1865, 1802–1809. [CrossRef]

- Çınar T, Karabağ Y, et al. The investigation of TIMI risk index for prediction of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol. 2020, 75, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Butt K, D’Souza J, et al. Correlation of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) with Contrast-Induced Nephropathy in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Cureus. 2020, 12, e11879.

- Akcay A, Nguyen Q, et al. Mediators of inflammation in acute kidney injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2009, 2009, 137072.

- Ösken A, Öz A, et al. The association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with carotid artery stenting. Vascular. 2021, 29, 550–555. [CrossRef]

- Jansen MP, Emal D, et al. Release of extracellular DNA influences renal ischemia reperfusion injury by platelet activation and formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Kidney Int. 2017;91(2):352–364.

- Gameiro J, Fonseca JA, et al. Neutrophil, lymphocyte and platelet ratio as a predictor of mortality in septic-acute kidney injury patients. Nefrologia. 2020, 40, 461–468. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Bagci, Fatih aksoy, et al. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index May Predict the Development of Contrast-Induced Nephropathy in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Angiology. 2022, 73, 218–224. [CrossRef]

- Yang YL, Wu CH, Hsu PF, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) predicted clinical outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020, 50, e13230. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).