Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

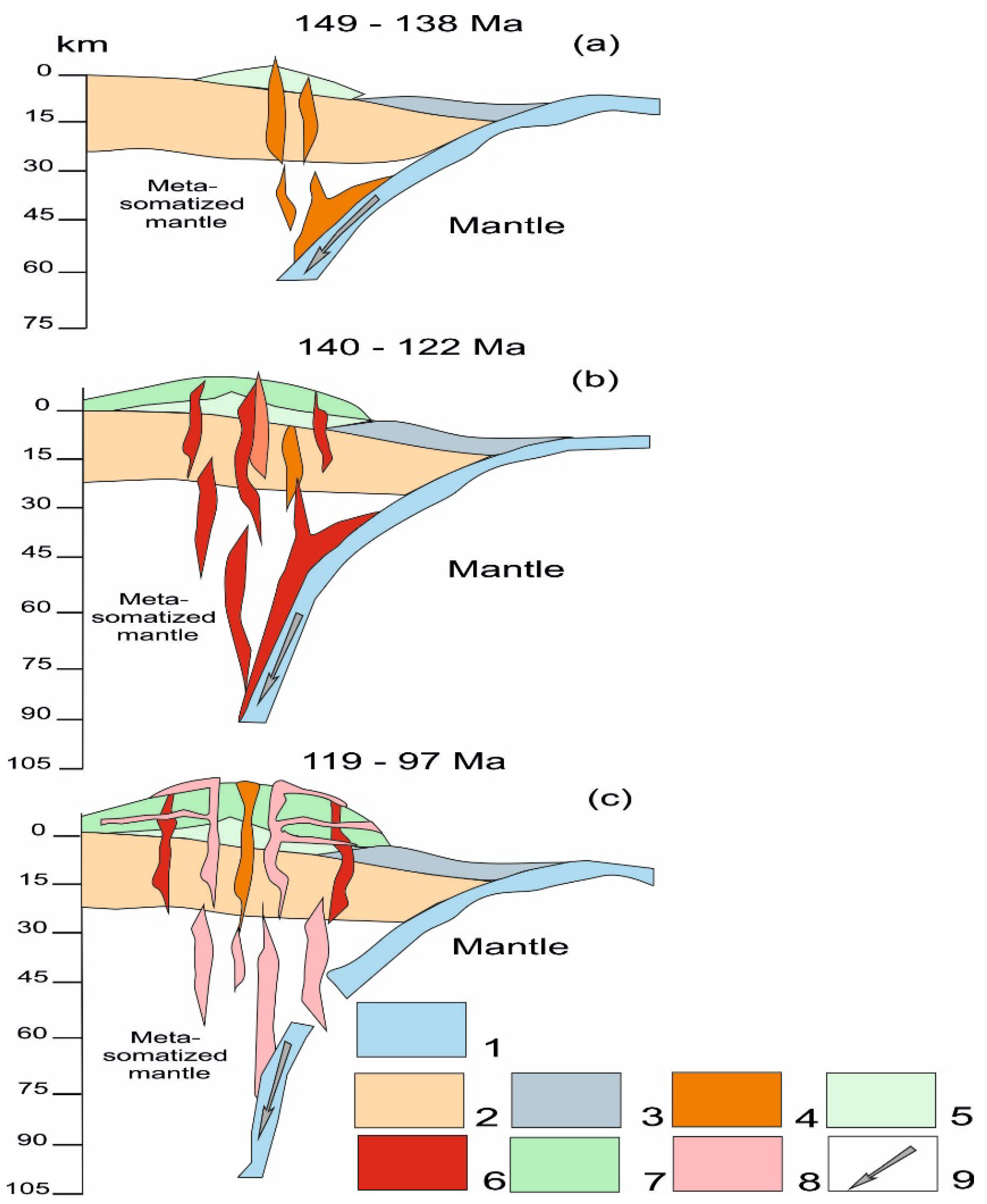

The presented work is the result of the study and the analysis of the distribution of ore manifestations and geochemical fields of gold and magmatic complexes of the Late Mesozoic in the framing of the Eastern flank of the Mongol-Okhotsk orogenic belt. It was found that elevated concentrations of this noble element are noted within the areas of telescoping of rocks of magmatic complexes formed in various geodynamic settings. The main testing ground for studying this problem was the southern framing of the Eastern flank of the Mongol-Okhotsk orogenic belt (Russia). Here, the processes of combining various magmatic stages, is most clearly manifested. The chosen object of study was the intrusive Uskalin massif. The massif is composed of rocks that reflect the following geodynamic events: initial over-subductional (149– 138 Ma), subductional (140– 122 Ma), collisional (119– 97 Ma). The formation of this massif is accompanied by extensive mineralization zones with gold-bearing veins. Therefore, gold contents have been established directly in the granitoids, which exceed the Clarke values by 2.25.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

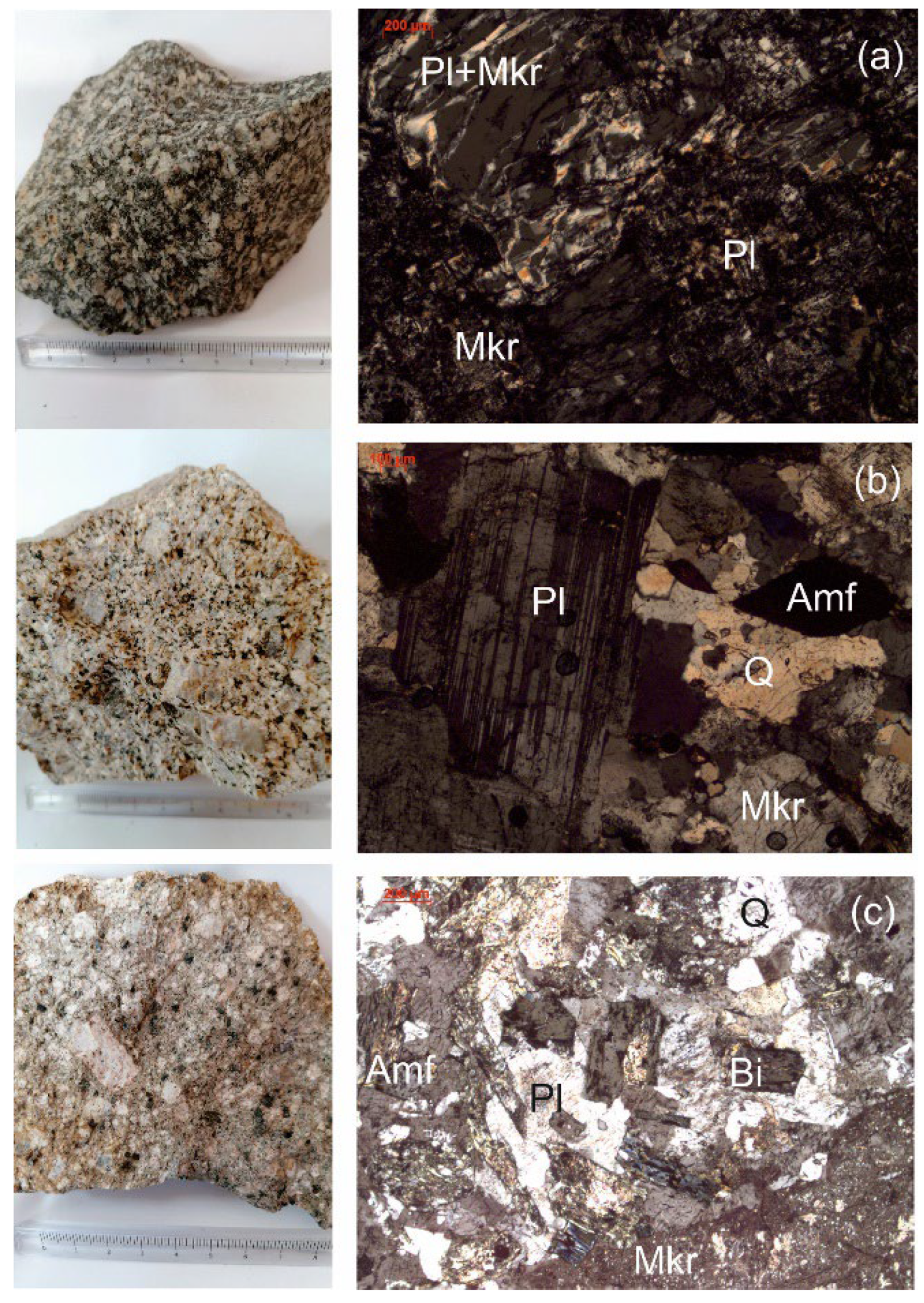

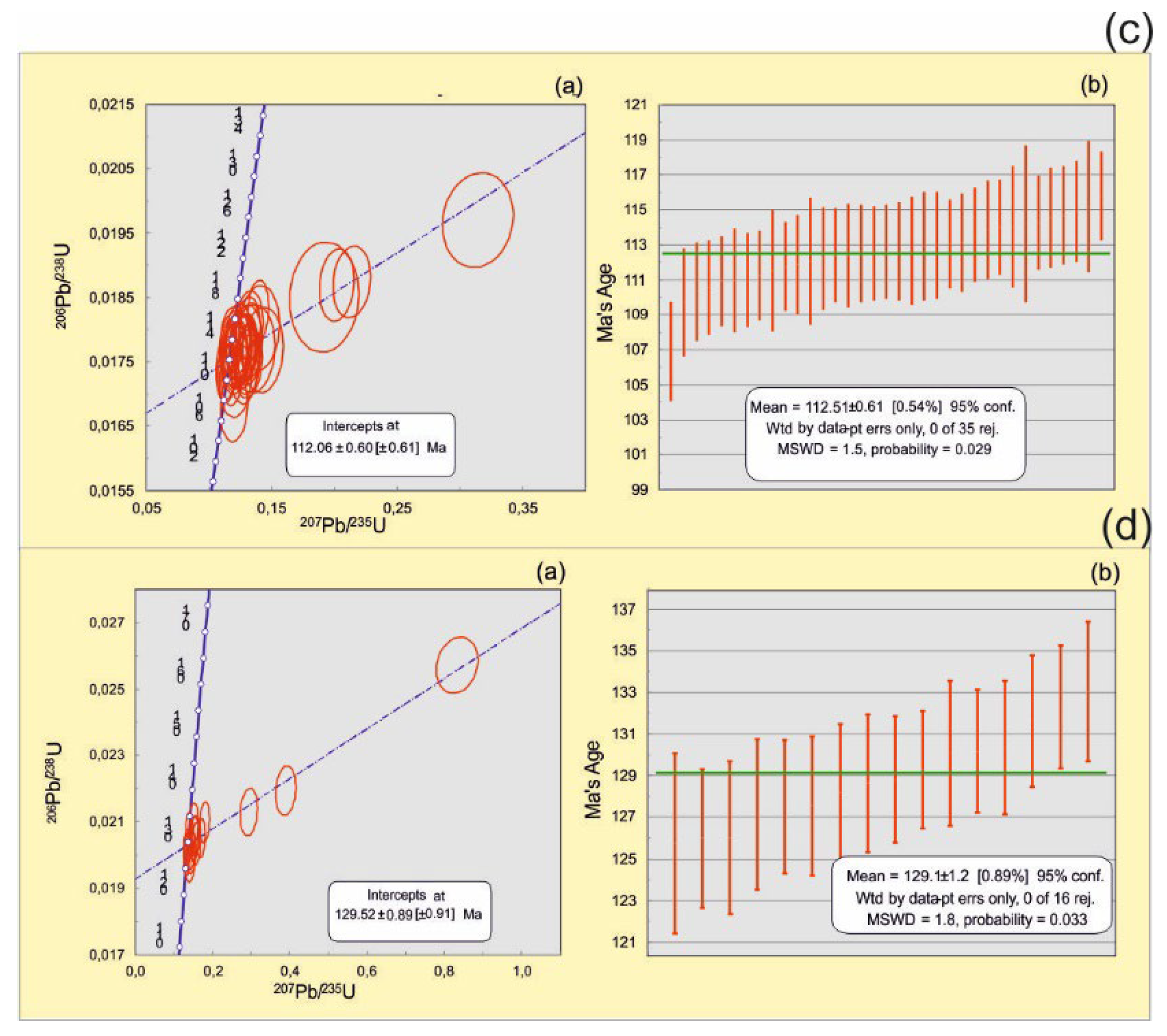

3.1. Petrographic Features and Age of Granitoids of the Uskalin Massif

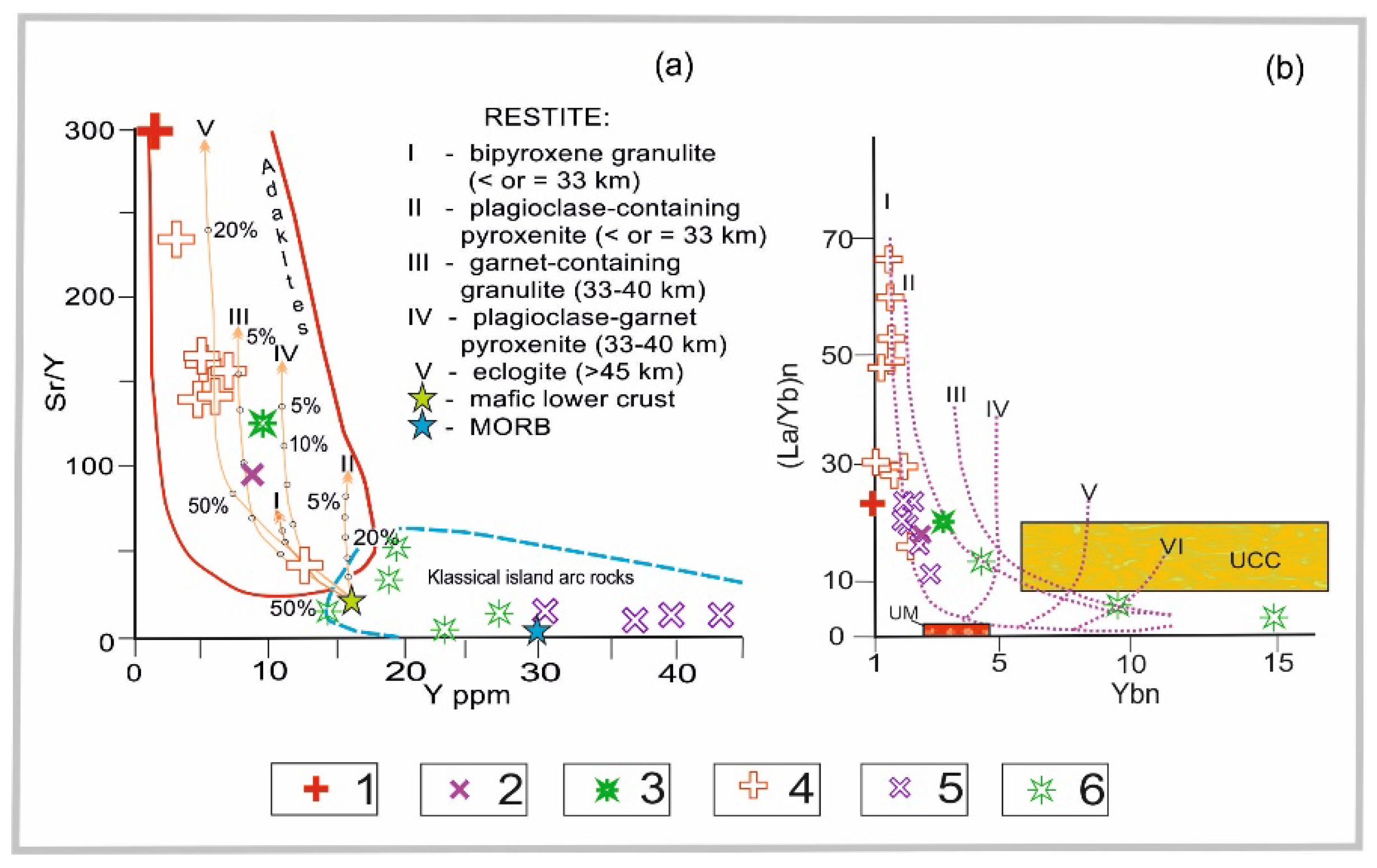

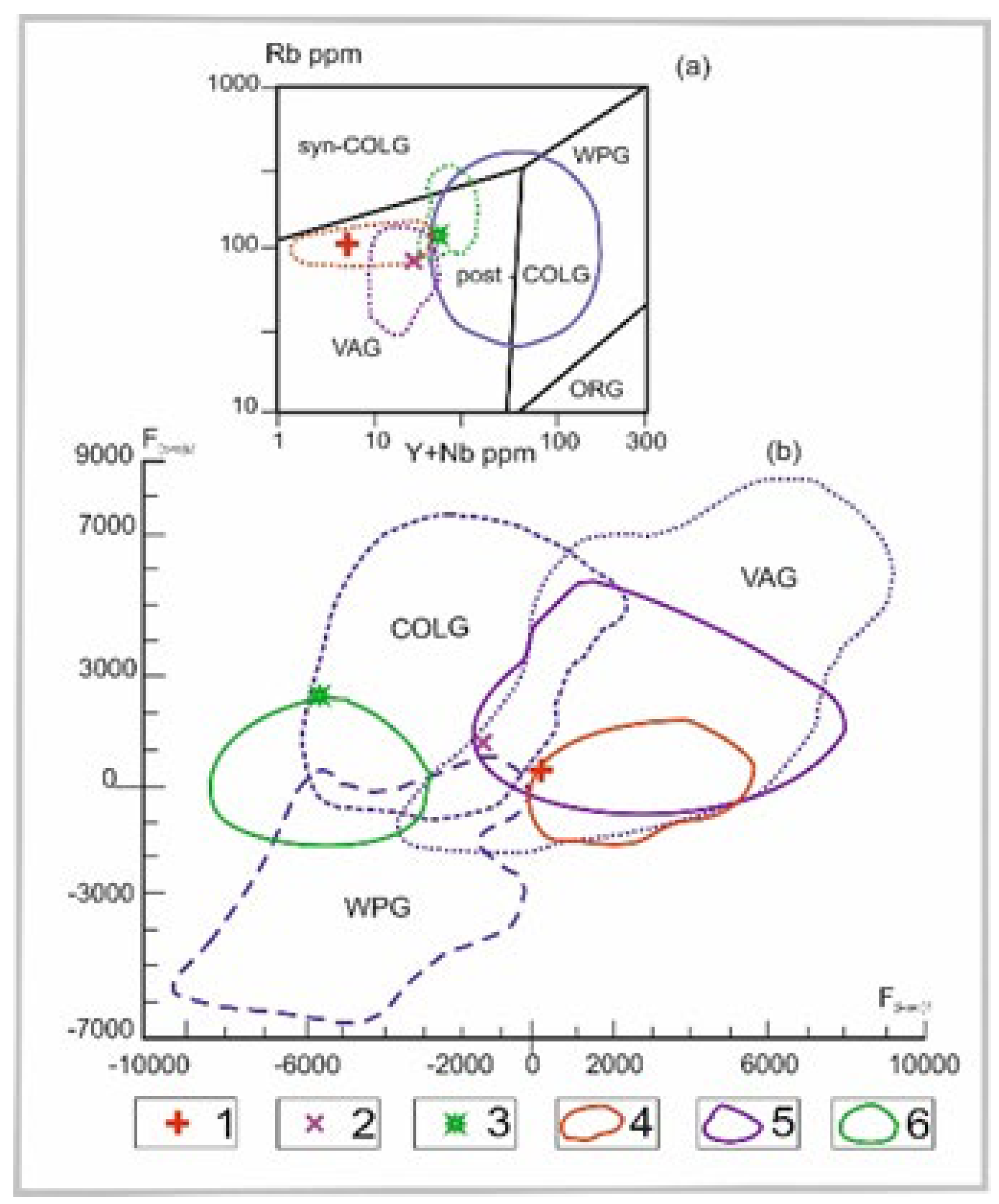

3.2. Geochemical Characteristics of Granitoids of the Uskalin Massif

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouysse, Ph. Geological map of the World, scale 1:50 000 000, 2009, Available from: http://www.ccgm.org.

- Sokolov, S.V. Structures of anomalous geochemical fields and mineralization forecast. Nauka: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1998; pp. 131.

- Derbeko, I.M.; Vyunov, D.L. Distribution of gold and silver mineralization in the territory of the Amur region (Russia) according to geochemical prospecting data and its role in geodynamic reconstructions. In Book Gold of Siberia and the Far East. Buryat Scientific Center SB RAS: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 2004; pp. 69-71.

- Derbeko, I.M.; Vyunov, D.L.; Bortnikov, N.S. The role of interaction of plume and plate tectonics mechanisms in the formation of gold-silver mineralization of the Upper Amur region (Russia) in the Late Mesozoic. Geology and mineral resources of Siberia. FSUE “SNIIGGiMS”: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2014; 3(1), 14-17.

- Poletika, I.A. General properties of gold deposits. Mining J. 1866, 1-10. (In Russian).

- Kravchinsky, V.A.; Cogné, J.-P.; Harbert, W.P.; Kuzmin, M.I. Evolution of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean as constrained by new palaeomagnetic data from the Mongol-Okhotsk suture zone, Siberia. Geophys. J. Inter. 2002, 148, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J.; Kusky, T. Geodynamic processes and metallogenesis of the Central Asian and related orogenic belts: Introduction. Gondwana Res. 2009, 16, 167–169. [Google Scholar]

- Metelkin, D.V.; Vernikovsky, V.A.; Kazansky, A.Y.; Wingate, M.T.D. Late Mesozoic tectonics of Central Asia based on paleomagnetic evidence. Gondwana Research 2010, 18, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbeko, I.M. Bimodal volcano-plutonic complexes in the frames of Eastern member of Mongol-Okhotsk orogenic belt, as a proof of the time of final closure of Mongol-Okhotsk basin. In Book Up-dates in volcanology - A Comprehensive Approach to Volcanological Problems, Francesco Stoppa; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; Chapter 5, 99-124.

- Shevchenko, B.F.; Popeko, L.I.; Didenko, A.N. Tectonics and evolution of the lithosphere of the eastern fragment of the MongolOkhotsk orogenic belt. Geodyn. end Tectonoph. 2014., 5(3), 667–682. [CrossRef]

- Van der Voo, R.; van Hinsbergen, D.J.J.; Domeier, M.; Spakman, W.; Torsvik, T.H. Latest Jurassic–earliest Cretaceous closure of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean: A paleomagnetic and seismological-tomographic analysis. Geol. Soc. of America Spec. Pap. 2015, 513, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhao, H. Further paleomagnetic results from the ~ 155 Ma Tiaojishan Formation, Yanshan Belt, North China, and their implications for the tectonic evolution of the Mongol-Okhotsk suture. Gondwana Res. 2016, 35 180–191. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Yang, T.; Gao, Y.; Turbold, S.; Zhao, H.; Wu, H.; Li, H.; Fu, H.; Xu, B.; Zhang, J.; Tomurtogoo, O. New late Jurassic to early Cretaceous paleomagnetic results from North China and southern Mongolia and their implications for the evolution of the Mongol-Okhotsk suture. J. of Geophysical Res. Solid Earth 2018, 123(12), 10,370–10,398. [CrossRef]

- Derbeko, I.; Kichanova, V. Post-Mesozoic Evolution of the Eastern Flank of the Mongol–Okhotsk Orogenic Belt. Advances in Geophysics, Tectonics and Petroleum Geosciences 2021., CAJG 2019. Springer, Cham, 4, 577-581. [CrossRef]

- Derbeko, I. The Influence of an Interdependent Structures on the Post-Mesozoic Evolution of the Eastern Flank of the Mongol-Okhotsk Orogenic Belt. Intern. J. of Geosc. 2022., 13(6). [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, V.D.; Melnikov, A.V.; Kovtanyuk, G.P. Gold placers of the Amur region. 2006, pp. 295.

- Vetluzhskikh, V.G. Regularities of placement, conditions of formation and prospects for discovery of gold placers in the south of the Aldan Shield and in the Stanovoy folded region. Abstract of a PhD dissertation. Far Eastern Scientific Center of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, Russia, 1972.

- Derbeko, I.M.; Chugaev, A.V. Late Mesozoic adakite granites of the southern frame of the eastern flank of the Mongol-Okhotsk orogenic belt: material composition and geodynamic conditions of formation. Geodyn. end Tectonoph. 2020, 11(3), 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbeko, I.M. Late Mesozoic Granitoid Magmatism in the Evolution of the Eastern Flank of the Mongol-Okhotsk Orogenic Belt (Russia). Minerals 2022, 12(11), 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbeko, I. Late Mesozoic Adakite Granites in the Northern Framing of the Eastern Flank of the Mongol–Okhotsk Orogenic Belt. Geochem. Intern. 2023, 61(1), 62–74. [CrossRef]

- Derbeko, I.M., Ponomarchuk, V.A., Vyunov, D.L., Kozyrev S.K. Bimodal post-collision volcano-plutonic complex in the southern rim of the eastern flank of the Mongol-Okhotsk orogenic belt. In Book: Proceedings of the 24-th IAGS, D.R. Lentz, K.G. Thorne, K.-L. Beal; Canada, 2009; pp. 143--46.

- Derbeko, I.M.; Vyunov, D.L.; Kozyrev, S.K.; Ponomarchuk, V.A. Conditions for the formation of a bimodal volcano-plutonic complex, within the southern margin on the eastern flank of the Mongol-Okhotsk orogenic belt. In Book Large igneous provinces of Asia, mantle plumes and metallogeny, Novosibirsk, Russia 2009; pp. 73-75.

- Zhang, K-J.; Yan, L.-L.; Ji, C. Switch of NE Asia from extension to contraction at the mid-Cretaceous: A tale of the Okhotsk oceanic plateau from initiation by the Perm Anomaly to extrusion in the Mongol–Okhotsk ocean? Earth-Science Rev. 2019, 198, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Stricha, V.E. U-PB isotope age (shrimp-ii) of granitoids of a magdagachinsky complex of the Umlekano-Ogodzhinsky vulkano-plutonic zone. Bull. of Amur State Univer., Russia 2016, 75, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyrev, S.K.; Volkova, Y.R.; Ignatenko, N.N. State map of the Russian Federation-scale 1: 200 000. Ed. VE Chepygin. Series Zeya. Sheet N-51-XXIII. Explanatory note. Moscow branch of FSBI “VSEGEI”: Moscow, Russia, 2016.

- Khubanov, V.B.; Buyantuev, M.D.; Tsygankov, A.A. U-Pb isotope dating of zircons from PZ-MZ igneous complexes of Transbaikalia by magnetic sector mass spectrometry with laser sampling: procedure for determination and comparison with SHRIMP data. Geol. and Geoph. 2016, 57(1), 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, W.L.; Powell, W.J.; Pearson, N.J.; O’Reilly, S.Y. GLITTER: data reduction software for laser ablation ICP-MS. In Book Laser ablation ICP-MS in the Earth sciences: current practices and outstanding issues. Mineralogical association of Canada short course series; P.J. Sylvester; Canada 2008, 40, 204–207.

- Ludwig, K.R. Isoplot 3.6: Berkeley Geochronology Center. Spec. Publ., 2008, 4 77.

- Sun, S-s.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. In Book Magmatism in the Ocean Basins; A.D. Sounders, M.J. Norry; The Geol. Soc. Spec. Public.: London, England, 1989, Volume 42, pp. 313–345. [CrossRef]

- Defant, M.J.; Drummond, M.S. Derivations of some modern are magmas by melting of young subducted lithosphere. Nature 1990, 347, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zheng, J.P.; Xu, Y.G.; Griffin, W.L.; Zhang, R.S. Are continental “adakites” derived from thickened or foundered lower crust? Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 2015, 419, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H. The mechanisms of petrogenesis of the Archaean continental crust - comparison with modern processes, Lithos 1993, 46, 373-388.

- Martin, H. Adakitic magmas: modern analogues of Archaean granitoids, Lithos 1999, 46(3), 411-429. [CrossRef]

- Barbarian, B. Granitoids: main petrogenetic classifications in relation to origin and tectonic setting. Geol. J. 1990, 25, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J. Sources and settings of granitic rocks. Episodes 1996, 24, 956–983. [Google Scholar]

- Velicoslavinsky, S.D. Geochemical typification of acid magmatic rocks of leading geodynamical situations. Petrology 2003, 26(2), 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Eirish, I.V. Metallogeny of golg of Priamurye (Amur Region, Russia), V.A. Stepanov; Dalnauka: Vladiostok, Russia, 2002; pp. 97 - 121.

- Sorokin, A.A.; Kadashnikova, A.Y.; Ponomarchuk, A.V.; Travin, A.V.; Ponomarchuk, V.A. Age and genesis of the Pokrovskoye gold-silver deposit (Russian Far East). Geol. and Geoph. 2021, 62(1), 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.H.G.; Garson, M.S. Mineralization of plate boundaries. Minerals. Sci. Engng. 1976. 8, 129–169.

- Mitchell, A.H.G.; Garson, M.S. Mineral Deposits and Global Tectonic Settings (Academic Press Geology Series). Published by Academic Press Inc: London, UK, 1981.

- Browne, P.R.L.; Hedenquist, J.W.; Allis, R.G. Epitherminal gold mineralization; Belousov V.I.; Geothermal Research Centre: Wellington, New Zealand. 1988, pp. 169.

- Qiu, K.-F.; Deng J.; Laflamme С.; Long, Z.-Y.; Wana R.-Q.; Moynier; F.; Yu H.-C.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Ding Z.-J.; Goldfarb R. Giant Mesozoic gold ores derived from subducted oceanic slab and overlying sediments. Geoch. et Cosmoch. Acta 2023, 343, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Yeap, E.B. Tin and gold mineralizations in Peninsular Malaysia and their relationships to the tectonic development. J. of Southeast Asian Earth Scienc. 1993, 8, 1–4, 329-348.

- Zheng, W.; Liu, B.; McKinley, J.M.; Cooper, M.R.; Wang, L. Geology and geochemistry-based metallogenic exploration model for the eastern Tethys Himalayan metallogenic belt, Tibet. J. of Geoch. Explor. 2021, 224, 106743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Mao, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, W.N.P.; Yang, X. Hydrothermal ore deposits in collisional orogens. Science Bull. 2019. www.elsevier.com/locate//scib.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).