Submitted:

26 December 2023

Posted:

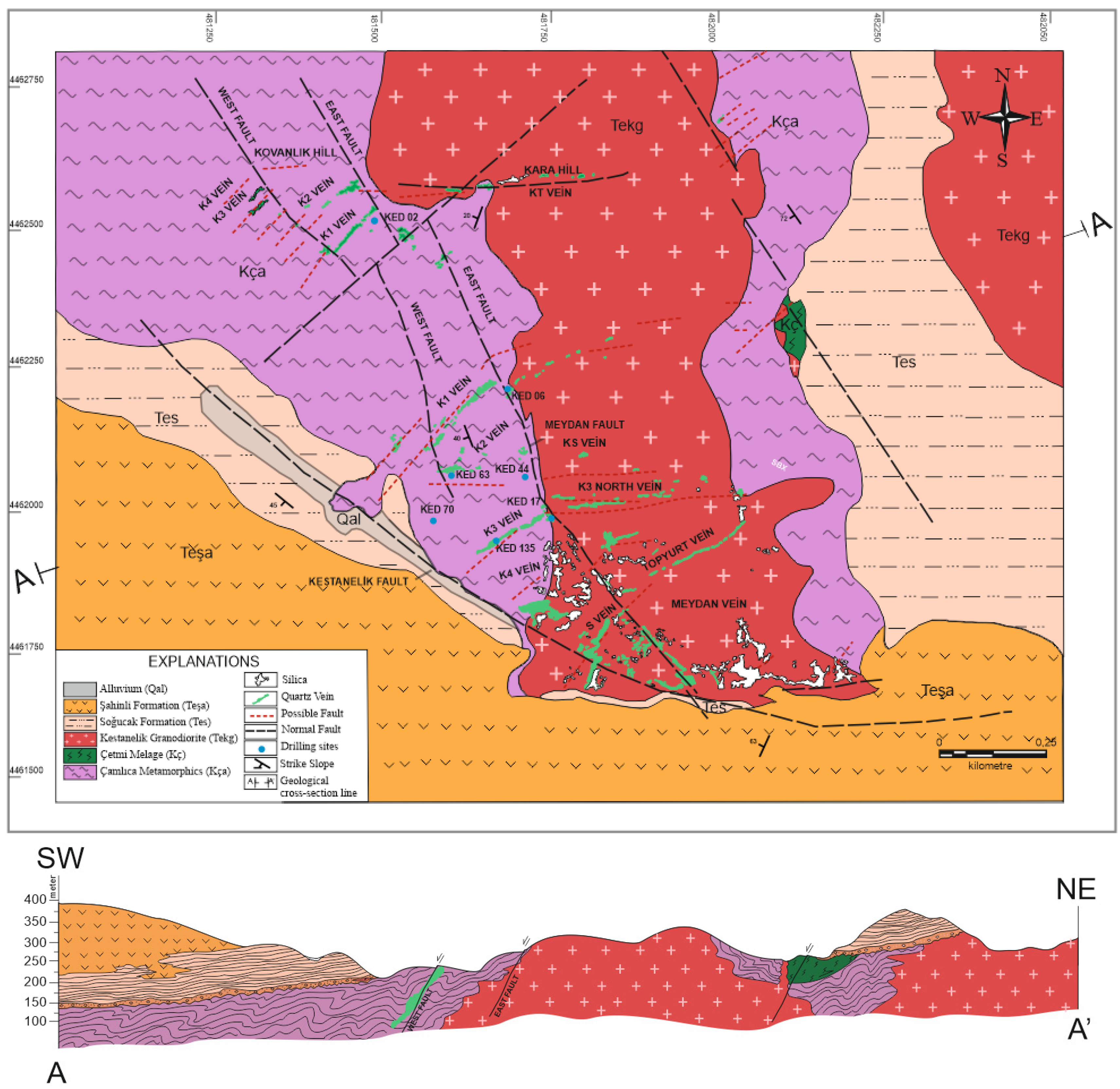

10 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

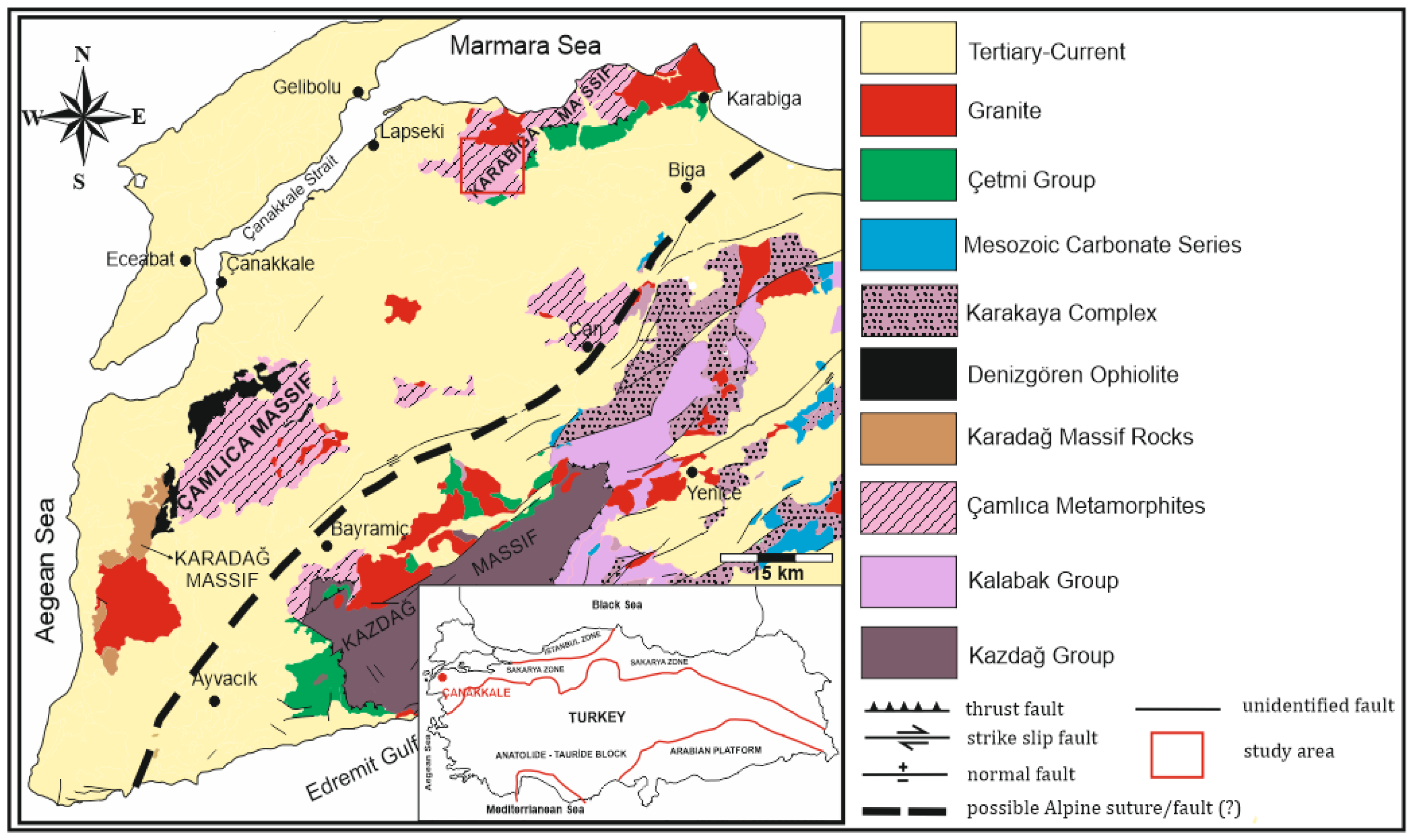

2. Regional Geology

3. Local Geology

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

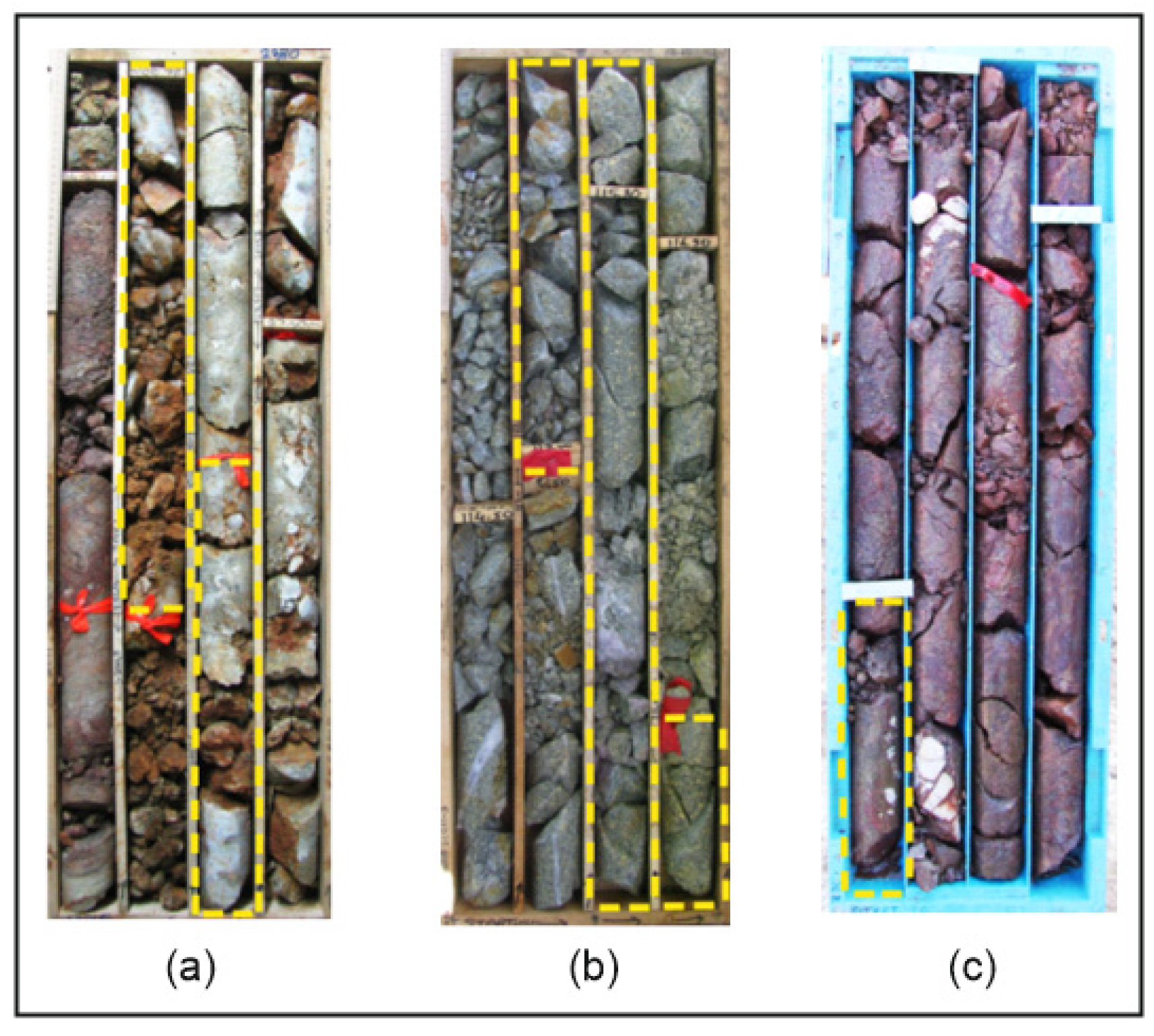

5.1. Hydrothermal Alteration and Au Mineralization

5.2. Petrography-Mineralogy of Alteration Deposits

5.2.1. Polarizing Microscope Investigations

5.2.2. X-ray Diffraction-Mineralogy of Alteration Deposits

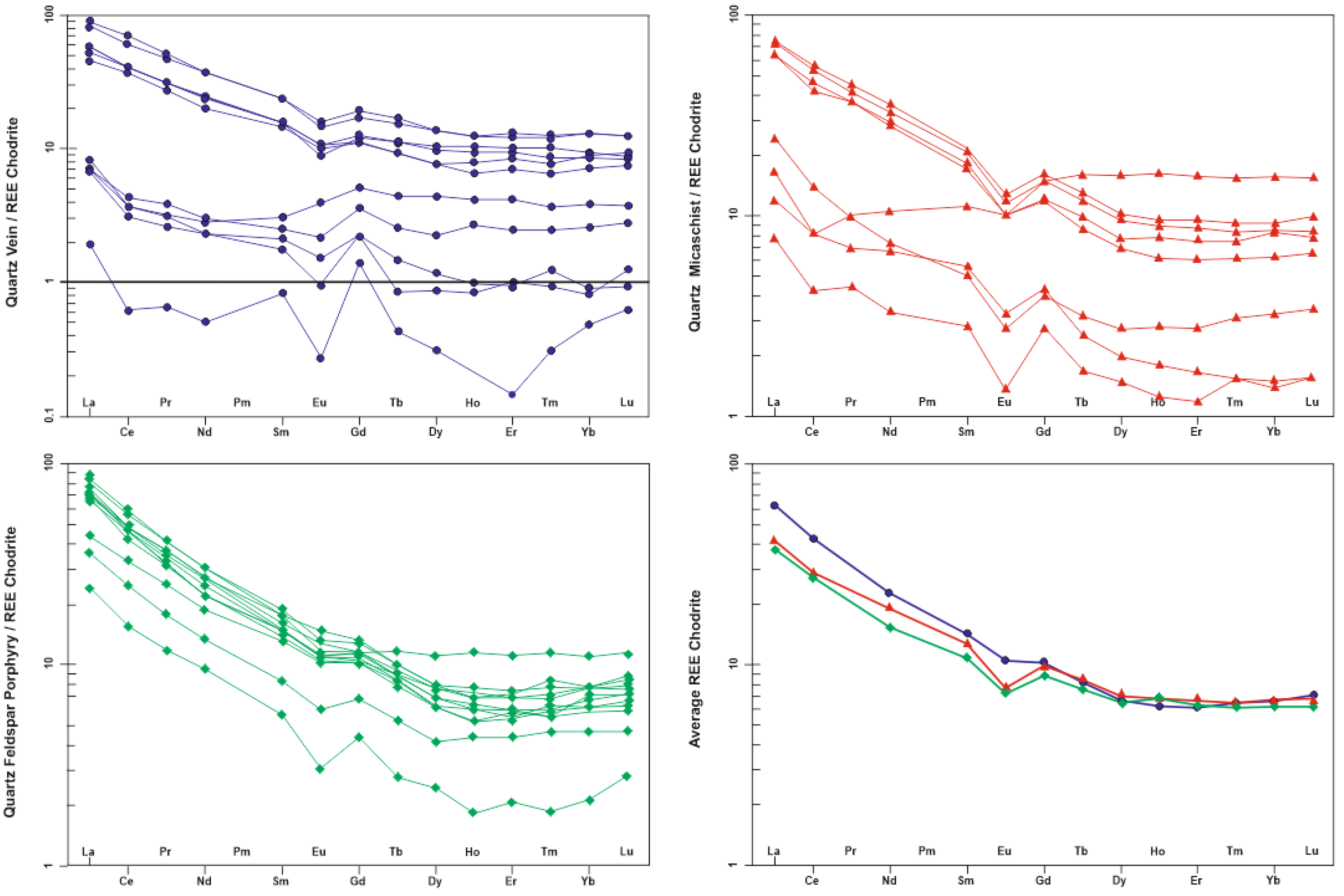

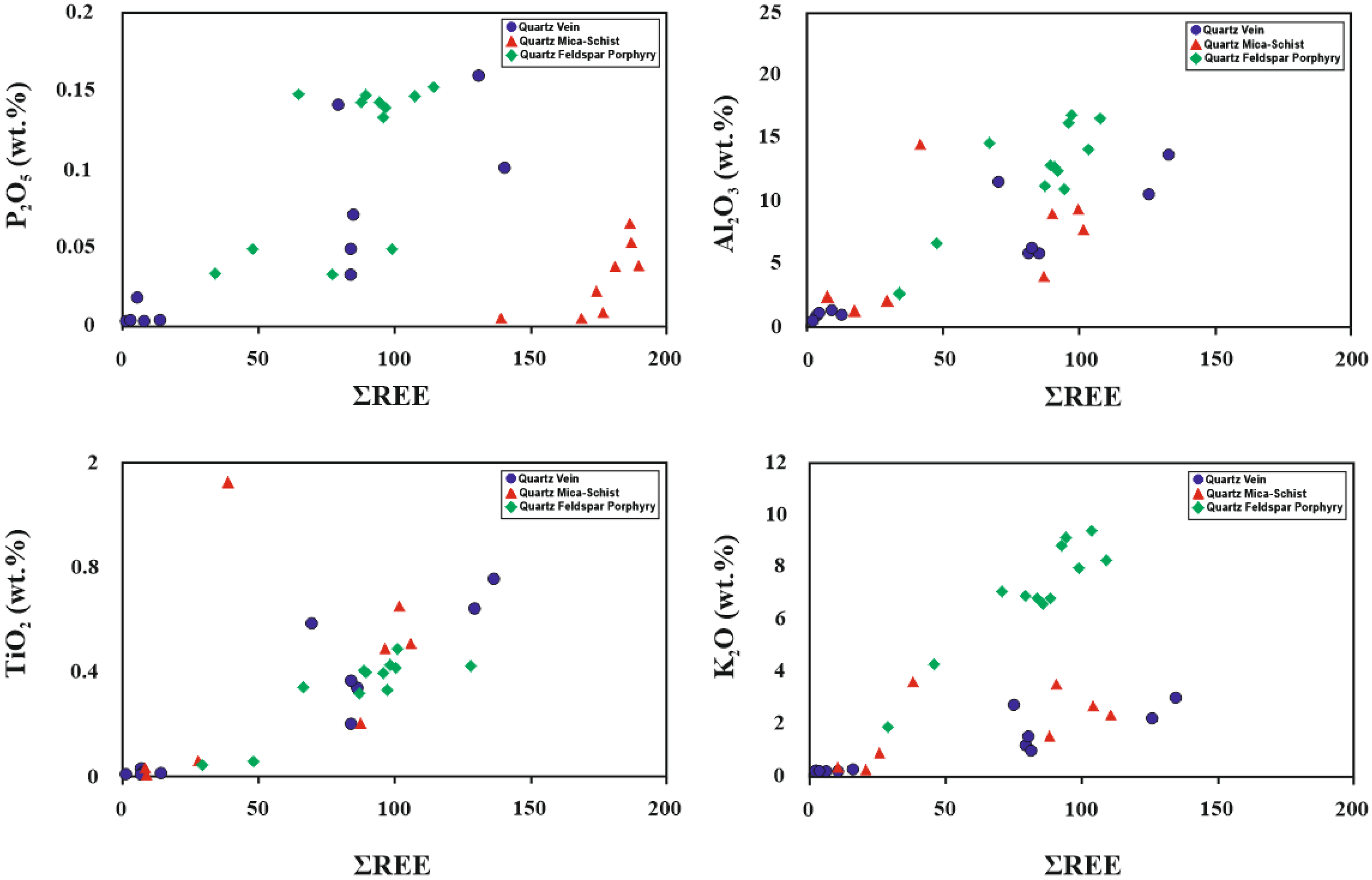

5.3. Geochemical Composition and REE Pattern

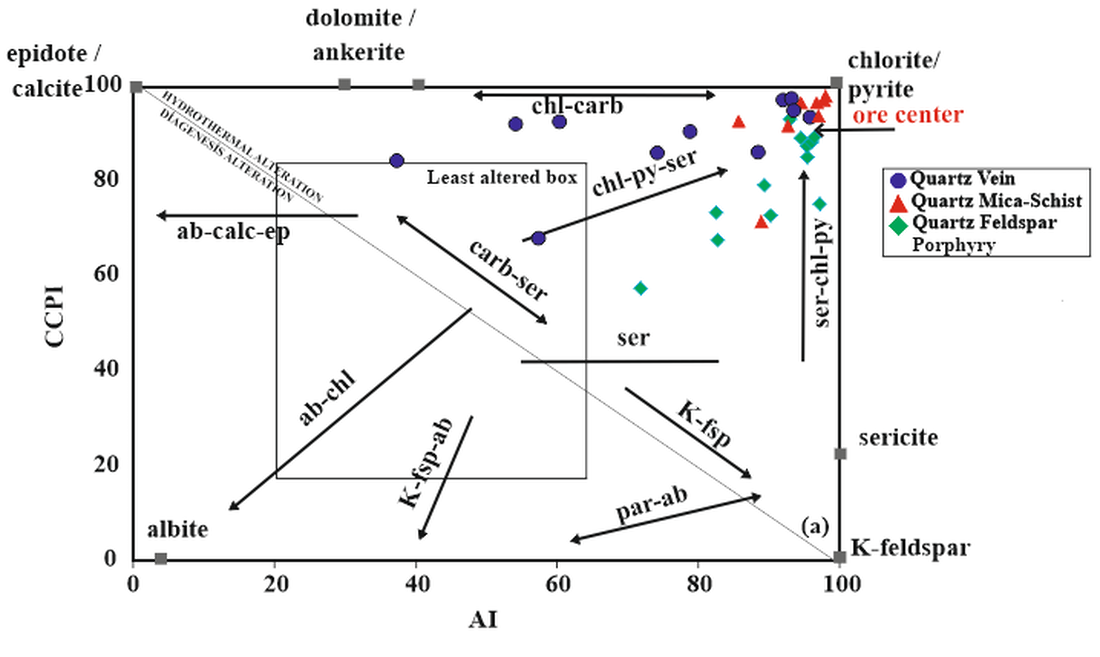

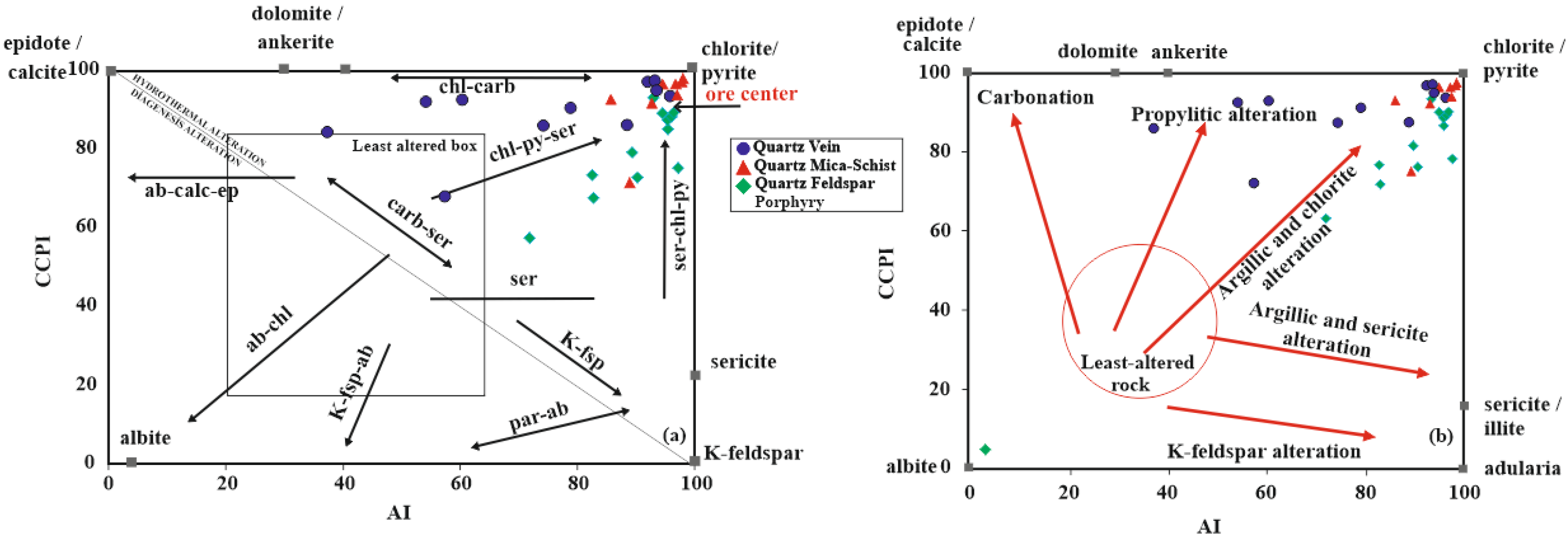

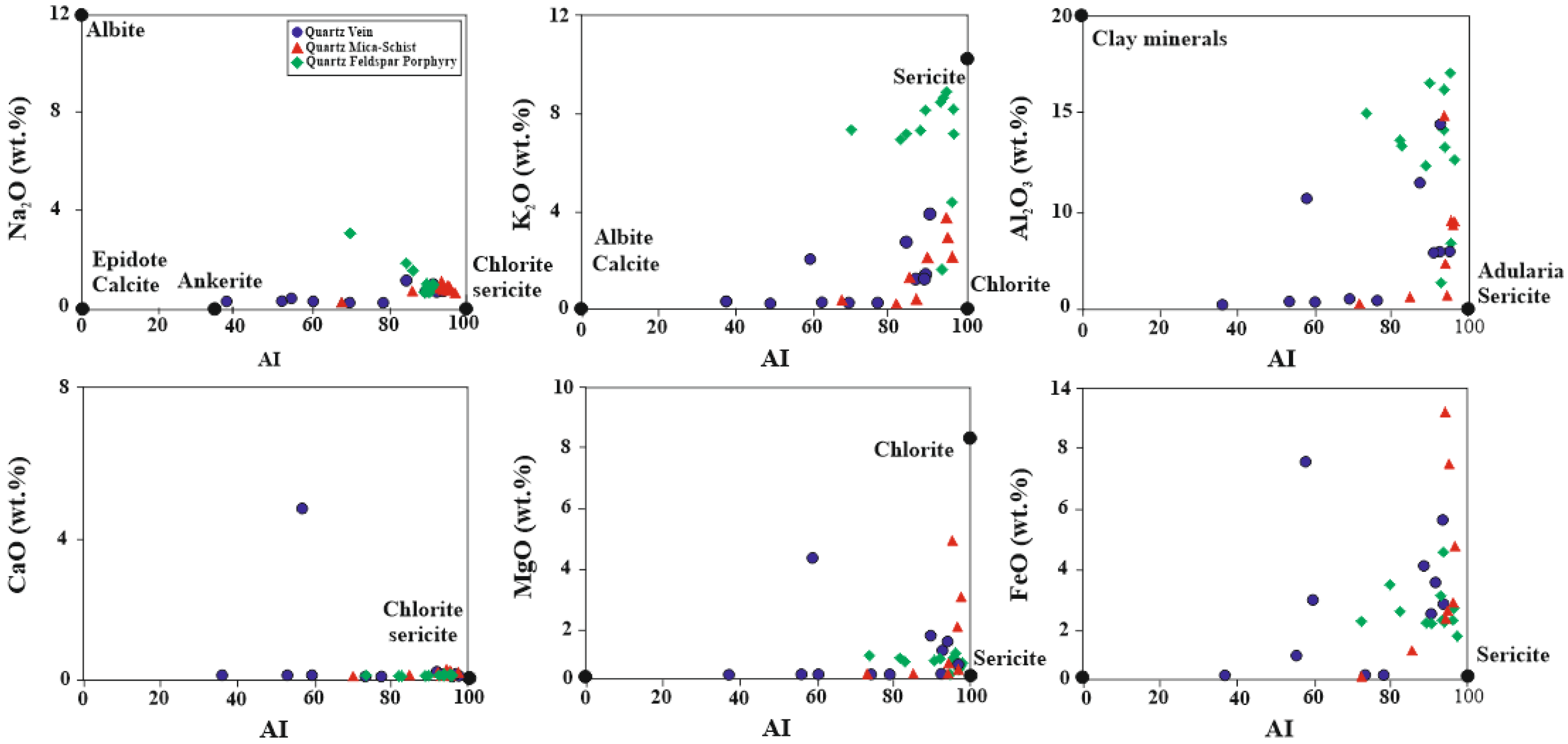

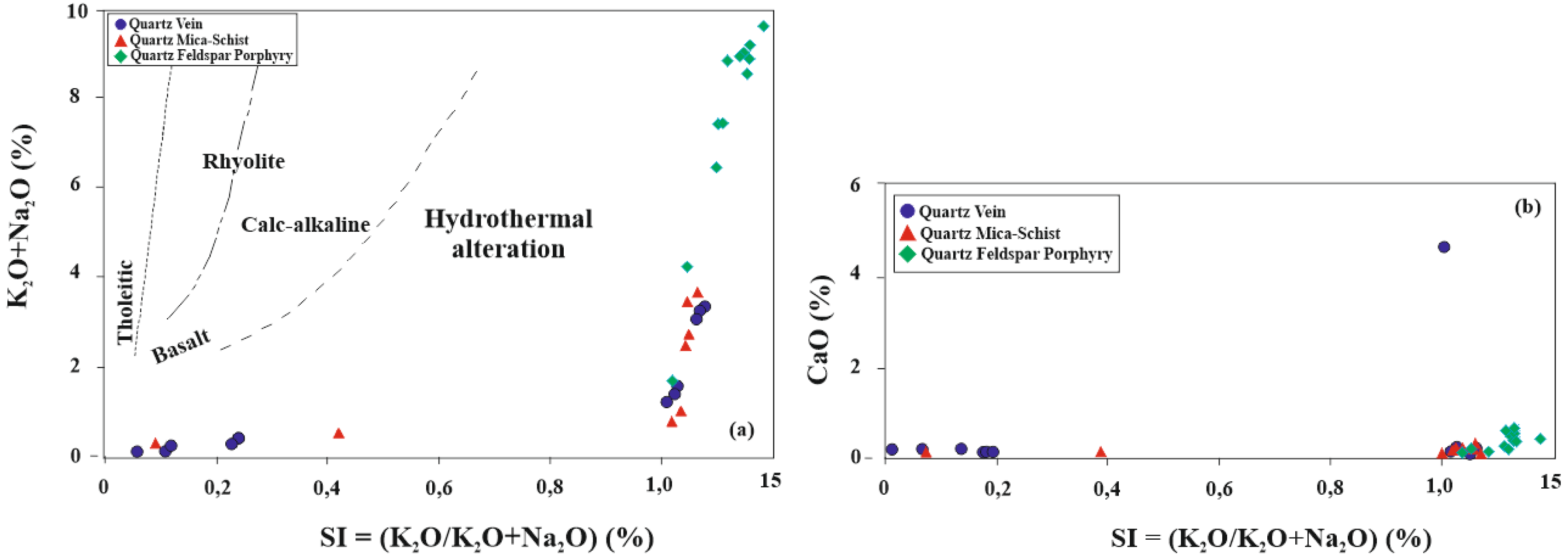

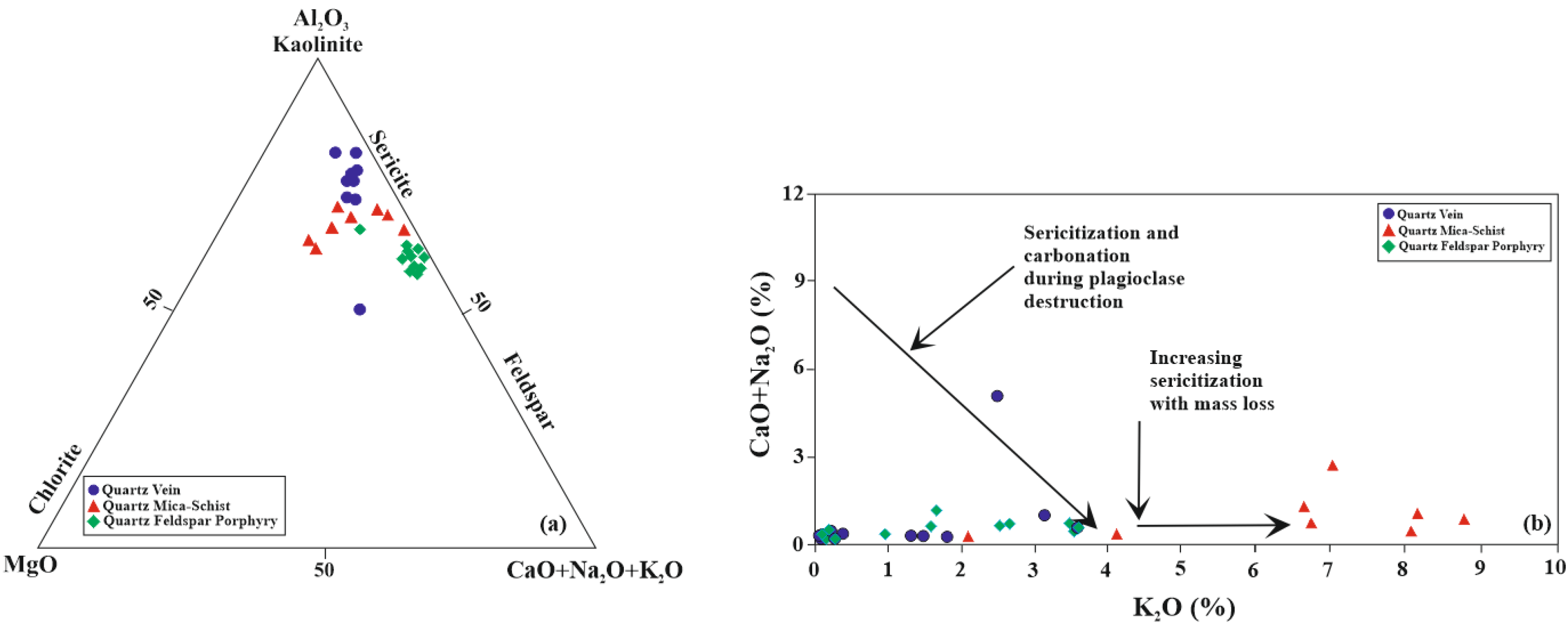

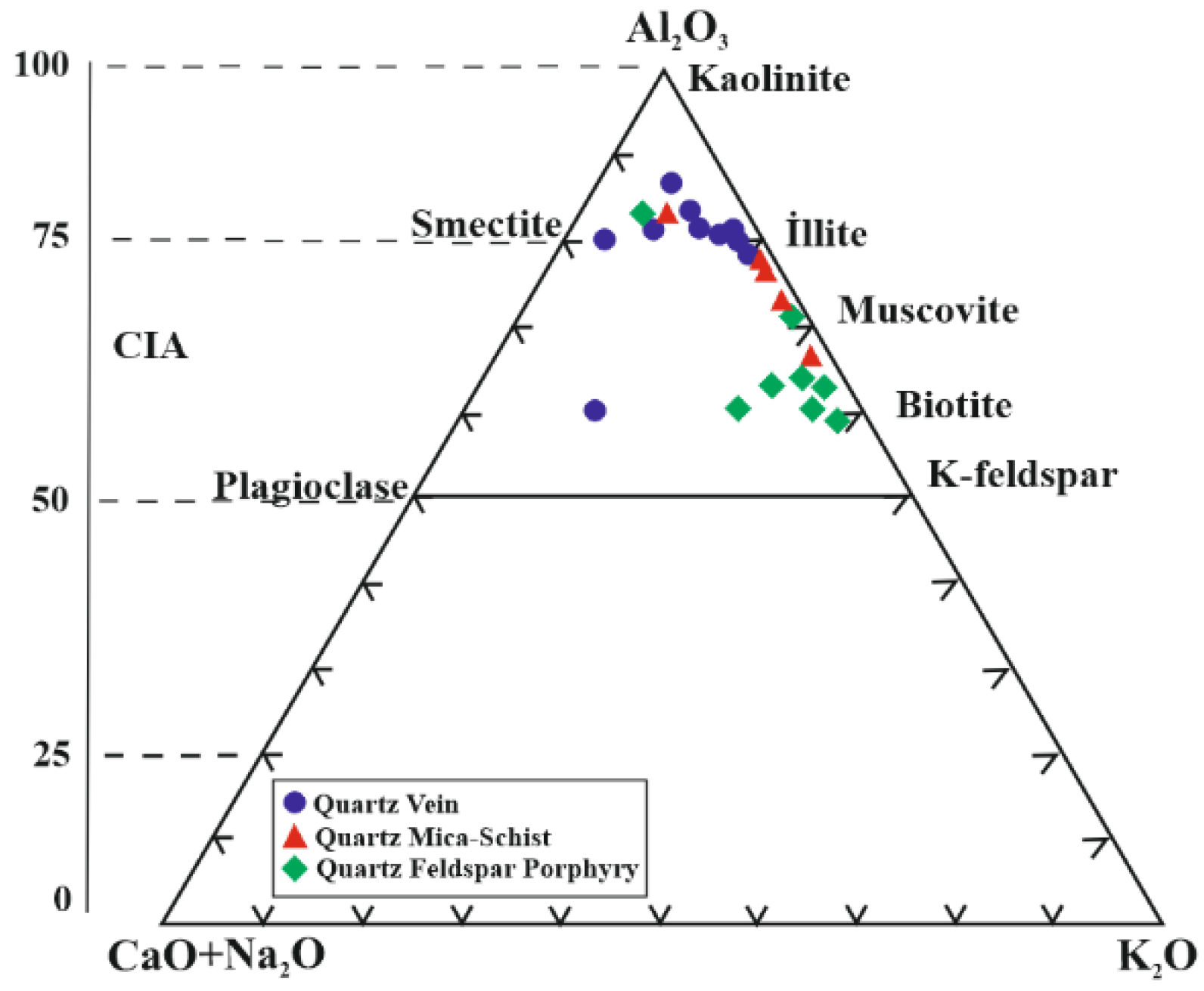

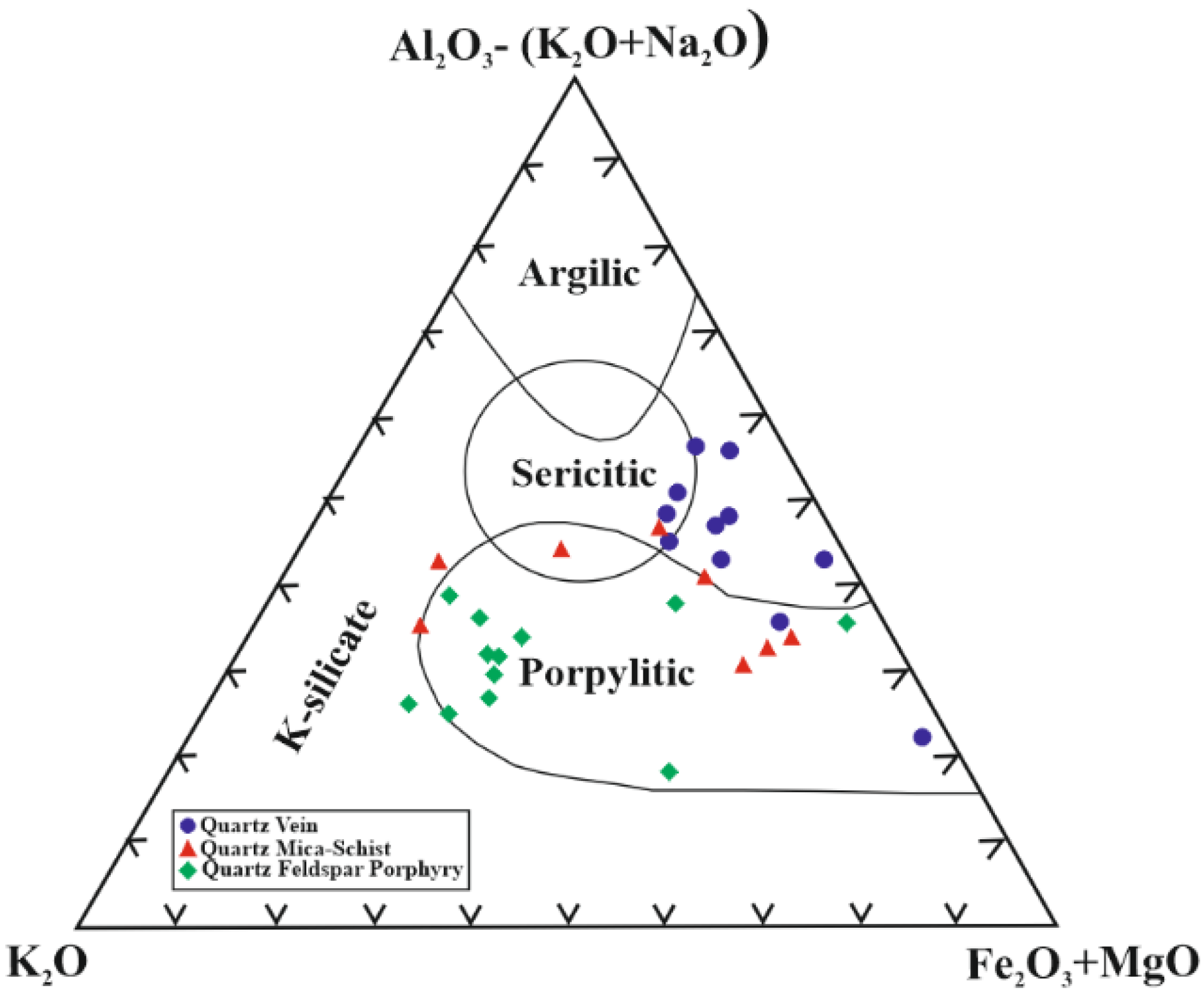

5.4. Hydrothermal Alteration Indices

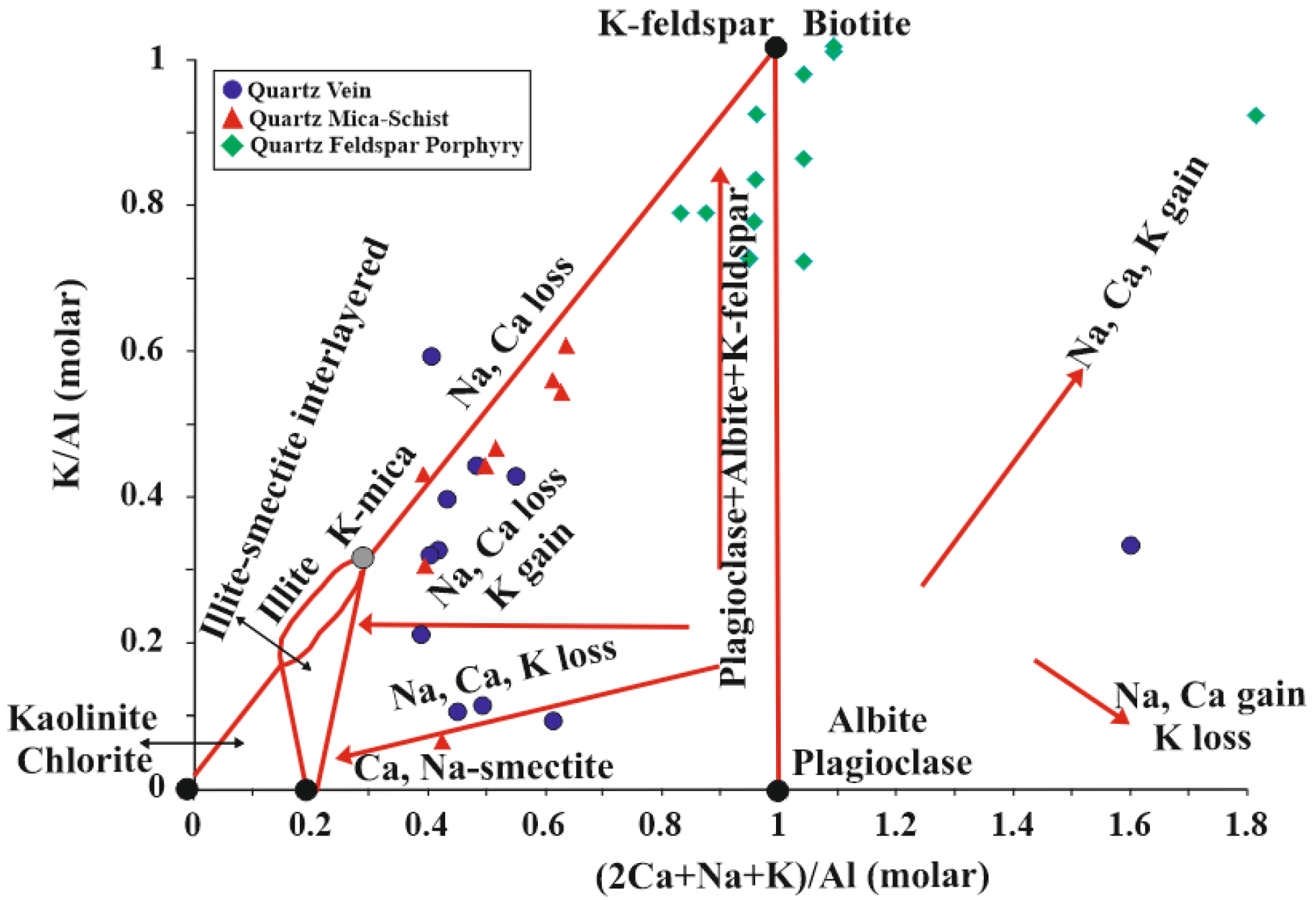

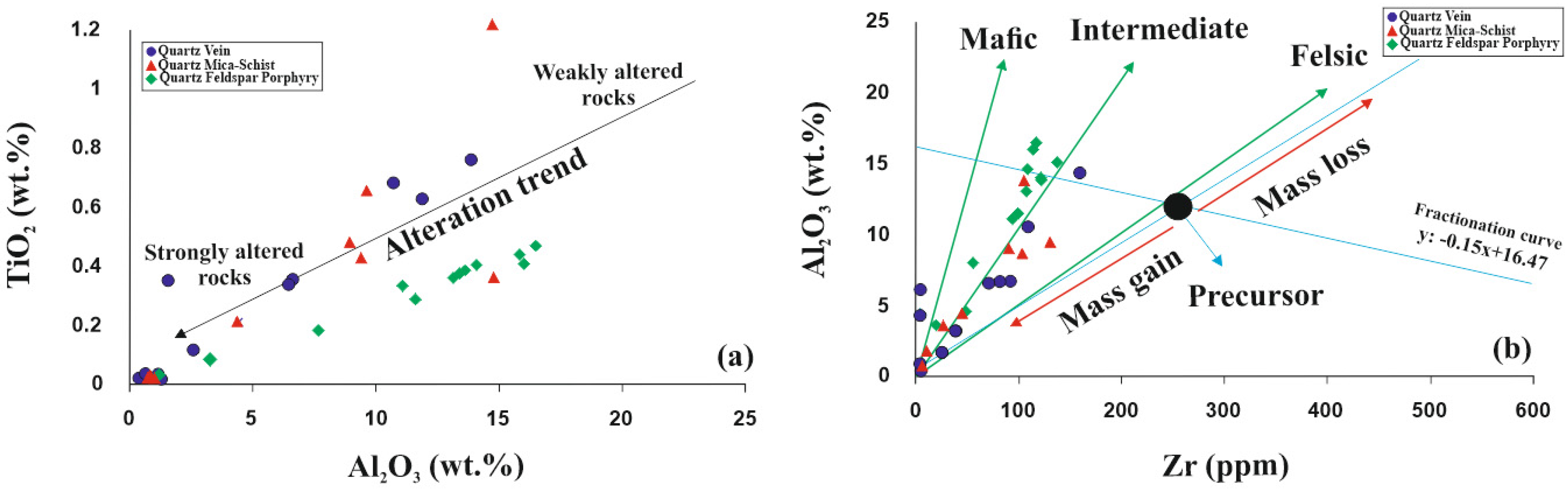

5.5. Molar Ratio and Mass Gain-Loss

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berger, B.R.; Bonham, H.F., Jr. Epithermal gold-silver deposits in the western United States: time-space products of evolving plutonic, volcanic and tectonic environments. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 1990, 36, 103–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, F. The geology of hydrothermal gold deposits in Chile. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 1990, 36, 197–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Morrison, G.; Jaireth, S. Quartz textures in epithermal veins, Queensland: classification, origin and implication. Economic Geology 1995, 90, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, H.; Oyman, T.; Arehart, G.A.; Çolakoğlu, R.; Billor, Z. Low-sulfidation type Au–Ag mineralization at Bergama, Izmir, Turkey. Ore Geology Reviews 2007, 32, 81–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, H.; Oyman, T.; Sönmez, F.N.; Arehart, G.B.; Billor, Z. Intermediate sulfidation epithermal gold-base metal deposits in Tertiary subaerial volcanic rocks Şahinli/Tespih Dere (Lapseki/Western Turkey). Ore Geology Reviews 2010, 37, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal İmer, E.; Güleç, N.; Kuşcu, İ.; Fallick, A.E. Genetic investigation and comparison of Kartaldag and Madendag epithermal gold deposits in Çanakkale, NW Turkey. Ore Geology Reviews 2013, 53, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Richards, J.P.; DuFrane, S.A.; Rebagliati, M. Geochemistry, geochronology, and fluid inclusion study of the Late Cretaceous Newton epithermal gold deposit, British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 2016, 53, 10–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, X.; Deng, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Lai, J.; Bayless, R.C.; Pan, M.; Longjiao, L.; Shang, Q. Hydrothermal processes at the Axi epithermal Au deposit, Western Tianshan: insights from geochemical effects of alteration, mineralization and trace elements in pyrite. Ore Geology Reviews 2018, 102, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najaran, M.; Mehrabi, B.; Siani, M. G. Mineralogy, hydrothermal alteration, fluid inclusion, and O–H stable isotopes of the Siah Jangal-Sar Kahno epithermal gold deposit, SE Iran. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 125, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novruzov, N.; Valiyev, A.; Bayramov, A.; Mammadov, S.; Ibrahimov, J.; Ebdulrehimli, A. Mineral composition and paragenesis of altered and mineralized zones in the Gadir low sulfidation epithermal deposit (Lesser Caucasus, Azerbaijan). Iranian Journal of Earth Sciences 2019, 11, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Siani, M.G.; Lentz, D.R. Lithogeochemistry of various hydrothermal alteration types associated with precious and base metal epithermal deposits in the Tarom-Hashtjin metallogenic province, NW Iran: implications for regional exploration. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2022, 232, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.P.; Christie, A.B. Hydrothermal alteration, mineralogical footprints for New Zealand epithermal Au-Ag deposits. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 2019, 62, 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.P.; Gazley, M.F.; Stuart, A.G.; Pearce, M.A.; Birchall, R.; Chappell, D.; Christie, A.B.; Stevens, M.R. Hydrothermal alteration at the Karangahake epithermal Au-Ag deposit, Hauraki Goldfield, New Zealand. Economic Geology 2019, 114, 243–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B. E. Epithermal gold deposits, Mineral deposits of Canada: a synthesis of major deposits-types, district metallogeny, the evolution of geological provinces, and exploration methods. Goodfellow, W.D., (ed.), Geological Association of Canada, Mineral Deposits Division 2007, Special Publication N. 5, pp. 113–139.

- White, N.C.; Hedenquist, J.W. Epithermal gold deposits: styles, characteristics and exploration. SEG Newsletter 1995, 23, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.M. Ore geology and industrial minerals: an introduction. Blackwell Publ., Oxford, 1993; pp. 389.

- Deb, M. Epithermal gold deposits: their characteristics and modeling, (online), available, psdg.bgl.esdm.go.id/makalah/Bandung-Gold-Mihir.pdf, August 23, 2023. 23 August.

- Hedenquist, J.W.; Arribas, R.A.; Gonzalez-Urien, E. Exploration for epithermal gold deposits. Society of Economic Geology Reviews 2000, 13, 245–277. [Google Scholar]

- Duba, D.; Williamsjones, A.E. The application of illite crystallinity, organic-matter reflectance, and isotopic techniques to mineral exploration-A case-study in southwestern Gaspé, Quebec. Economic Geology 1983, 78, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.L.; Kelley, K.D.; Coker, W.B.; Caughlin, B.; Doherty, M.E. Beyond the obvious limits of ore deposits: The use of mineralogical, geochemical, and biological features for the remote detection of mineralization. Economic Geology 2006, 101, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Guo, W.; Shi, W.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lian, D. Characterization of illite clays associated with the Sinongduo low sulfidation epithermal deposit, Central Tibet using field SWIR spectrometry. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 120, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, T.; Mokko, H.; Matsumoto, A.; Sato, T. Comparison of smectite–corrensite–chlorite series minerals in the Todoroki and Hishikari Au–Ag deposits: applicability of mineralogical properties as exploration index for epithermal systems. Natural Resources Research 2021, 30, 2889–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S.F.; White, N.C.; John, D.A. Geological characteristics of epithermal precious and base metal deposits. Society of Economic Geologists 2005, Inc., 485–522. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C.; Hemley, J.J. Wall rock alteration in geochemistry of ore deposits (ed. H.L. Barnes) (M). New York, 1967; pp. 166–235.

- Rose, A.W.; Burt, D.M. Hydrothermal alteration. In Barnes, H. L. (Ed.), Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits, John Wiley & Sons. New York, 1979; p. 173-235.

- Chen, M.T.; Wei, J.H.; Li, Y.J.; Shi, W.J.; Liu, N.Z. Epithermal gold mineralization in Cretaceous volcanic belt, SE China: insight from the Shangshangang deposit. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 118, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihatmoko, S.; Idrus, A. Low sulfidation epithermal gold deposits in Java, Indonesia: characteristic and linkage to the volcano-tectonic setting. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 121, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıray, D. Determination of the origin of Kestanelik Au-Ag mineralization in Şahinli (Lapseki-Çanakkale, Western Turkey) region by geological, mineralogical and geochemical investigations. PhD. Thesis, Süleyman Demirel University, 2021; pp. 217.

- Bakhsh, R.A.; Ahmed, A. H, The Umm Matierah gold prospect: Mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of a potential low-sulfidation epithermal gold deposits, southeastern Arabian Shield, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2023, X 9, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikaeili, K.; Hosseinzadeh, M.R.; Moayyed, M.; Maghfouri, S. The Shah-Ali-Beiglou Zn-Pb-Cu (-Ag) deposit, Iran: an example of intermediate sulfidation epithermal type mineralization. Minerals 2018, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imer, A.; Richards, J.P.; Muehlenbachs, K. Hydrothermal evolution of the Çöpler porphyry-epithermal Au deposit, Erzincan Province, central eastern Turkey. Economic Geology, 1619. [Google Scholar]

- Kıray, D.; Cengiz, O. Petrographical and geochemical characteristics of the Kestanelik granitoid (Çanakkale, Biga Peninsula). Geological Bulletin of Turkey 2023, 66, 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gürler, Z. Karadere low sulphidation gold deposit (İvrindi, Balıkesir): an example for detachment fault-related epithermal gold deposits in Western Turkey. M.Sc. Thesis, Balıkesir University, 2019; p. 100.

- Dill, H.G.; Dohrmann, R.; Kaufhold, S.; Çiçek, G. Mineralogical, chemical and micromorphological studies of the argillic alteration zone of the epithermal gold deposit Ovacik, Western Turkey: tools for applied and genetic economic geology. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2015, 148, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Rosúa, J.; Morales-Ruano, S.; Esteban-Arispe, I.; Hach-Ali, P.F. Significance of phyllosilicate mineralogy and mineral chemistry in an epithermal environment. Insights from the Palaı-Islica Au-Cu deposit (Almeria, SE Spain). Clays and Clay Minerals.

- Cravero, F.; Domınguez, E.; Iglesias, C. Genesis and applications of the Cerro Rubio kaolin deposit, Patagonia Argentina. Applied Clay Science 2001, 18, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, H.G.; Fricke, A.; Henning, K. H.; Theune, C.H. Aluminium phosphate mineralization from the hypogene La Vanguardia kaolin deposit (Chile). Clay Minerals 1995, 30, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, H.G.; Bosse, H.-R.; Henning, K.H.; Fricke, A.; Ahrendt, H. Mineralogical and chemical variations in hypogene and supergene kaolin deposits in a mobile fold belt the Central Andes of northwestern Peru. Mineralium Deposita 1997, 32, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, S.; Erkoyun, H. Genesis of the hydrothermal Karaçayır kaolinite deposit in Miocene volcanics and Palaeozoic metamorphic rocks of the Uşak-Güre Basin, western Turkey. Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences 2013, 22, 444–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfil, S.A.; Maiza, P.J.; Montecchiari, N. Alteration zonation in the Loma Blanca kaolin deposit, Los Menucos, Province of Rio Negro, Argentina. Clay Minerals 2010, 45, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkaya, Ö.; Bozkaya, G.; Uysal, İ.T.; Banks, D.A. Illite occurrences related to volcanic-hosted hydrothermal mineralization in the Biga Peninsula, NW Turkey: Implications for the age and origin of fluids. Ore Geology Reviews 2016, 76, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkaya, Ö.; Bozkaya, G.; Hanilçi, N.; Güven, A.S.; Banks, D.A.; Uysal, İ.T. Mineralogical evidences on argillic alteration in the Çöpler porphyry-epithermal gold deposit (Erzincan, East-Central Anatolia). Geological Bulletin of Turkey 2018, 31, 335–358. [Google Scholar]

- Schalamuck, I.B.; Zubia, M.; Genini, A.; Fernandez, R.R. Jurassic epithermal Au–Ag deposits of Patagonia, Argentina. Ore Geol. Rev. 1997, 305, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, R.H. Exploration and discovery of base- and precious-metal deposits in the Circum-Pacific region during the last 25 years. Resource Geology Special Issue no. 19. Society of Resource Geology 1995, pp.

- Gresens, R.L. Composition volume relationships of metasomatism. Chem. Geol. 1967, 2, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Sawaguchi, T.; Iwaya, S.; Horiuchi, M. Delineation of prospecting targets for Kuroko deposits based on models of volcanism of underlying dacite and alteration haloes. Mining Geology 1976, 26, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt, H.W.; Young, G.M. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. Nature 1982, 299, 299,715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.E.; MacLean, W.H. The geology of the New Insco copper deposit, Noranda District, Quebec. Canadian Jour. Earth Sci. 1983, 20, 1291–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, W.H.; Kranidiotis, P. Immobile elements as monitors of mass transport in hydrothermal alteration: Phelps Dodge massive sulfide deposit, Matagomi. Econ.Geol. 1987, 82, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, W.H.; Hoy, L.D. Geochemistry of hydrothermally altered rocks at the Horne mine, Noranda, Quebec. Economic Geology 1991, 86, 506–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.F.; Whitehead, R.E. Molar ratios in the study of unaltered and hydrothermally altered greywackes and shales. Chemical Geology 1994, 111, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.F.; Whitehead, R.E. Alkali-alumina and MgO-alumina molar ratios of altered and unaltered rhyolites. Exploration and Mining Geology 2006, 15, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.F.; Whitehead, R.E. Alkali/alumina molar ratio trends in altered granitoid rocks hosting porphyry and related deposits. Exploration and Mining Geology 2010, 19, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, C.H.B.; Lentz, D.R. The gresens approach to mass balance constraints of alteration systems,11, Geological Association of Canada, 1994; pp.161-192.

- Lentz, D. R.; Gregoire, C. Petrology and mass-balance constraints on major-, trace-, and rare-earth-element mobility in porphyry-greisen alteration associated with the epizonal True Hill granite, southwestern New Brunswick, Canada. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 1995, 52, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, D.R. Recent advances in lithogeochemical exploration for massive-sulphide deposits in volcano-sedimentary environments: petrogenetic, chemostratigraphic, and alteration aspects with examples from the Bathurst Camp, New Brunswick. In Current Research 1995, Edited by B.M.W. Carroll. New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources and Energy, Minerals and Energy Division, Mineral Resources Report 1996; 96, 73–119.

- Madeisky, H.E. Quantitative analysis of hydrothermal alteration: applications in lithogeochemical exploration (Doctoral Dissertation, PhD., University of London, 1996.

- Franklin, J.M.; Duke, J.M. Lithogeochemical and mineralogical methods for base metal and gold exploration A.G. Gubins (Ed.), Proceedings of Exploration 97: Fourth Decennial International Conference on Mineral Exploration, 1997; pp.191-208.

- Aiuppa, A.; Allard, P.; D’Alessandro, W.; Michel, A.; Parello, F.; Treuil, M.; Valenza, M. Mobility and fluxes of major, minor and trace metals during basalt weathering and groundwater transport at Mt. Etna Volcano (Sicily). Geochimimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2000, 64, 1827–1841. [Google Scholar]

- Large, R.R.; Gemmell, J.B.; Paulick, H.; Huston, D.L. The alteration box plot: asimple approach to understanding the relationship between alteration mineralogy and lithogeochemistry associated with volcanic-hosted massive sulfide deposits. Economic Geology 2001, 96, 957–971. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J.A. Isocon analysis: a brief review of the method and applications. Phys. Chem.Earth. 2005, 30, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, A.; Martinez, E.; Pettinari, G.; Herrero, S. Weathering profiles in granites, Sierra Notre (Cordoba, Argentina). J. S. Am. Earth. Sci. 2005, 19, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipahi, F.; Sadıklar, M.B. The alteration mineralogy and mass change of the Zigana (Gümüşhane) volcanics of NE Turkey. Geological Bulletin of Turkey 2010, 53, 97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Akaryalı, E.; Tüysüz, N. The genesis of the slab window-related Arzular low-sulfidation epithermal gold mineralization (Eastern Pontides, NE Turkey). Geoscience Frontiers 2013, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giggenbach, W.F. Mass transfer in hydrothermal alteration systems-a conceptual approach. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1984, 48, 2693–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giggenbach, W.F. Geothermal solute equilibria: derivation of Na-K-Mg-Ca geoindicators. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1988, 52, 2749–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, C.R.; Madeisky, H.E. Lithogeochemical exploration for hydrothermal ore deposits using Pearce element ratio analysis. Geological Association of Canada, 1994; Short Course Notes 11.

- Stanley, C.R.; Madeisky, H.E. Lithogeochemical exploration for metasomatic zones associated with hydrothermal mineral deposits using Pearce element ratio analysis. Short Course Notes on Pearce Element Ratio Analysis, 1996.

- Stanley, C.R. Graphical investigation of lithogeochemical variations using molar element ratio diagrams: theoretical foundation. In lithogeochemical exploration for metasomatic zones associated with hydrothermal mineral deposits using molar element ratio analysis. Edited byC, 1998; 63-103.

- Stanley, C.R. Molar element ratio analysis of lithogeochemical data: a toolbox for use in mineral exploration and mining. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 2020, 20, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihed, P. Lithogeochemistry, metal and alteration zoning in the Proterozoic Tallberg porphyry-type deposit, northern Sweden. Journal of Geochemical Exploration.

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Yılmaz, Y. Tethyan evolution of Turkey: a plate tectonic approach. Tectonophysics 1981, 75, 181–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.P. Tectonic, magmatic, and metallogenic evolution of the Tethyan Orogen: from subduction to collision. Ore Geology Reviews 2015, 70, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldanmaz, E.; Pearce, J.A.; Thirlwall, M.F.; Mitchell, J.G. Petrogenetic evolution of late Cenozoic, post collision volcanism in western Anatolia, Turkey. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2000, 102, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunkaynak, Ş.; Genç, Ş.C. Petrogenesis and time-progressive evolution of the Cenozoic continental volcanism in the Biga Peninsula, NW Anatolia. Lithos 2008, 102, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketin, İ. Anadolu’nun tektonik birlikleri. Bulletin of the Mineral Research and Exploration 1966, 66, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, Y. Comparision of young volcanic associations of western and eastern Anatolia under compressional regime: a review. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 1990, 44, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengör, A.M.C.; Lom, N.; Sunal, G.; Zabcı, C.; Sancar, T. The Phanerozoic palaeotectonics of Turkey. Part I: an inventory. Mediterranean Geoscience Reviews.

- Okay, A.İ.; Siyako, M.; Bürkan, K.A. Geology and tectonic evolution of the Biga Peninsula (in Turkish with English Abstract). Turkish Assoc. Petrol Geol Bull 1990, 2, 83–121. [Google Scholar]

- Göncüoğlu, M.C. Introduction to the geology of Turkey: geodynamic evolution of the pre-Alpine and Alpine terranes. MTA Monographs Series, 4075; -74. [Google Scholar]

- Topuz, G.; Altherr, R.; Kalt, A.; Satır, M.; Werner, O.; Schwartz, W. H, Aluminous granulites from the Pulur complex, NE Turkey: acase of partial melting, efficient melt extraction and crystallisation. Lithos 2004, 72, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, G.; Altherr, R.; Schwartz, W.H.; Dokuz, A.; Meyer, H.P. Variscan amphibolites-facies rocks from the Kurtoğlu metamorphic complex (Gümüşhane area, Eastern Pontides, Turkey). Int. J. Earth Sci. 2007, 96, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.I.; Satir, M.; Siebel, W. Pre-Alpide Palaeozoic and Mesozoic orogenic events in the eastern Mediterranean region. In: Gee, D.G., Stephenson, R.A. (eds), European Lithosphere Dynamics. Geological Society, London, 2006; Memoirs 32, pp. 389–405.

- Delaloye, M.; Bingöl, E. Granitoids from western and nortwestern Anatolia: Geochemistry and modeling of geodynamic evolution. International Geology Review 2000, 42, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.İ.; Satır, M. Coeval plutonism and metamorphism in a Latest Oligocene metamorphic core complex in northwest Turkey. Geol. Mag. 137, 495–516. [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.İ.; Monod, O.; Monie, P. Triassic blueschists and eclogites from northwest Turkey: Vestiges of the Paleo-Tethyan subduction. Lithos 2002, 64, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.İ.; Göncüoğlu, C. The Karakaya complex: a review of data and concepts. Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences (Turkish J. Earth Sci.).

- Okay, A.İ.; Monie, P. Early Mesozoik subduction in the Eastern Mediterranean evidence from Triassic eclogite in northwest Turkey. Geology 1997, 25, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.İ.; Satır, M. Upper Cretaceous eclogite-facies metamorphic rocks from the Biga Peninsula, northwest Turkey. Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences (Turkish J. Earth Sci.).

- Dönmez, M.; Akçay, A.E.; Genç, Ş.C.; Acar, Ş. Middle-upper Eocene volcanism and marine ignimbrites in the Biga Peninsula. Bulletin of the Mineral Research and Exploration 2005, 131, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chesser Resources. Chesser Resources Limited. Annual Report, Çanakkale, 2012.

- Erenoğlu, O. Chrono-stratigraphic position of Eocene, Oligo-Miocene volcanics around Dededag (Beyçayır-Çanakkale) and their importance for regional volcanism in the Biga Peninsula. Ph. D. Thesis, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Çanakkale, 2014; pp. 217.

- Hedenquist, J.W. Observations on the Kestanelik and Karaayi prospects, Biga Peninsula, Turkey. Unpublished annual report for Chesser Resources, Çanakkale, 2012.

- Gülyüz, N.; Shipton, Z.K.; Kuşcu, İ.; Lord, R.A.; Kaymakcı, N.; Gülyüz, E.; Gladwell, D.R. Repeated reactivation of clogged permeable pathways in epithermal gold deposits: Kestanelik epithermal vein system, NW Turkey. Journal of the Geological Society 2018, 175, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümad Mining. Tümad Mining Industry and Trade Inc., Annual Report, 10, Çanakkale, 2020.

- Alderton, D.H.M.; Pearce, J. A.; Potts, P. J. Rare earth element mobility during granite alteration: evidence from southwest England. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1980, 49, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H.J.; Özgür, N.; Palacios, C.M. Relationship between alteration, rare earth element distribution, and mineralization of the Murgul Copper deposit, northeastern Turkey. Economic Geology 1988, 83, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongliang, X.; Yusheng, Z. The mobility of rare-earth elements during hydrothermal activity: areview. Chinese Journal of Geochemistry 1991, 10, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.D.; McArthur, J.M.; Walsh, J.N. Rare earth element behaviour during evolution and alteration of the Dartmoor granite, SW England. Journal of Petrology 1992, 33, 785–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitrasson, F.; Pin, C.; Duthou, J.L. Hydrothermal remobilization of rare earth elements and its effect on Nd isotopes in rhyolite and granite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1995, 130, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boynton, W.V. Cosmochemistry of the rare earth elements: meteorite studies. Chapter 3, Development of Geochemistry 1984; 2, 63-114.

- Sverjensky, D.A. Europium redox equilibria in aqueous solution. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1984, 67, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şaşmaz, A.; Yavuz, F. REE geochemistry and fluid inclusion studies of fluorite deposits from the Yaylagözü area (Yıldızeli-Sivas) in central Turkey. N. Jb. Geol. Paläont (Abh).

- Barrett, T.; Cattalani, S.; MacLean, W.H. Volcanic lithogeochemistry and alteration at the Dalbridge massive sulphide deposits, Noranda Quebec. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 1993, 48, 135–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilekler, G. Mineralization, Textural and Alteration Characteristics of the Şahinli (Sırakayalar and Karatepe) Low Sulfidation Epithermal Deposit (Lapseki, NW Turkey). Master Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, 2022; p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, I.; Simmons, S. F.; Mauk, J. L. Whole-rock geochemical techniques for evaluating hydrothermal alteration, mass changes, and compositional gradients associated with epithermal Au-Ag mineralization. Economic Geology 2007, 102, 923–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, A.; Albarede, F. The REE content of some hydrothermal fluids. Chemical Geology 1986, 55, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C.M.; Hein, U.F.; Dulski, P. Behaviour of rare earth elements during hydrothermal alteration at the Buena Esperanza copper–silver deposit, northern Chile. Earth Planetary Science Letter 1986, 80, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, H.W. Mobility and fractionation of rare earth elements during weathering of a granodiorite. Nature 1979, 279, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P. General geochemical properties of the rare earth elements. In: Henderson, P. (ed.) Rare Earth Element Geochemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier 1984;1-32.

- Corbett, G.J. Structural controls to porphyry Cu-Au and epithermal Au-Ag deposits in applied structural geology for mineral exploration. Australian Institute of Geoscientists Bulletin 2002, 36, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, G.J.; Leach, T.M. Southwest pacific rim gold-copper systems: structure, alteration and mineralization. Workshop manual, 1998; p. 185.

- White, N.C.; Hedenquist, J.W. Epithermal environments and styles of mineralization: variations and their causes, and guidelines for exploration. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 1990, 36, 445–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.C.; Leake, M.J.; McCaughey, S.N.; Parris, B.W. Epithermal deposits of the southwest Pacific. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 1995, 54, 87–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, R.H.; Hedenquist, J.W. Linkages between volcanotectonic settings, ore-fluid compositions, and epithermal precious-metal deposits. In Simmons SF, Graham I (eds) Soc. Econ. Geol. Spec. Pub. 2003, 10, 315–343. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.J.; Qi, J.P.; Chen, J.; Dai, M.C.; Li, J. Geology, fluid inclusion and stable isotope study of the Yueyang Ag-Au-Cu deposit, Zijinshan ore field, Fujian province, China. Ore Geology Reviews 2017, 86, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay, A.İ.; Tüysüz, O. Tethyan sutures of northern Turkey. In: Durand, B, Jolivet, L., Horvath, F. and Seranne, M. Eds. Mediterranean basins: Tertiary extension within the Alpine Orogen. Geological Society, London, 1999; Special Publication 156, 475-515.

- MTA. General and economic geology of the Biga Peninsula. Special Publication Series 28, 2012; p. 326 (in Turkish).

- Tunç, O.; Yiğitbaşı, E.; Şengün, F.; Wazeck, J.; Hofmann, M.; Linnemann, U. U-Pb zircon geochronology of northern metamorphic massifs in the Biga Peninsula (NW Anatolia-Turkey): new data and a new approach to understand the tectonostratigraphy of the region. Geodinamica Acta 2012, 25, 202–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerven, M. Nebengesteins alterationen and erfassung signifikanter zonierungen im Bereich des Jade-Erzfeldes. Dipl-Geol., Freir Universitate, Rohstoff and Umweltgeologie, Berlin, 1995; pp. 186.

| Sample Number | Sample Type | Qz | Ilt | Sme/Ilt/ | Kln | Fsp | Chl | Kln/Chl | Sme/Kl | Sme | Cal | Dol | Hm | Crist | Alu | Hbl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KED 02-02 | Quartz vein | 16 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 02-05 | Quartz mica schist | 16 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 02-06 | Quartz vein | 16 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| KED 02-07 | Quartz vein | 16 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 02-11 | Quartz mica schist | 16 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 02-13 | Quartz vein | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-03 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 15 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-04 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 16 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-05 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 14 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-06 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 15 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-07 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 18 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-08 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 13 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-10 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 15 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 06-11 | Quartz mica schist | 14 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 17-01 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 11 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 17-02 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 12 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 17-06 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 17-07 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 17-08 | Quartz vein | 15 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 44-02 | Quartz mica schist | 16 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 44-03 | Quartz mica schist | 17 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 44-12 | Quartz mica schist | 15 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 63-02 | Quartz vein | 17 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 63-03 | Quartz vein | 8 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 63-05 | Quartz vein | 17 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 63-09 | Quartz vein | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 63-10 | Quartz vein | 17 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 63-11 | Quartz vein | 16 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 70-01 | Quartz mica schist | 18 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 70-02 | Quartz mica schist | 15 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KED 135-03 | Quartz feldspar porphyry | 17 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| DL | Quartz Vein | Quartz Feldspar Porphyry | Quartz Micaschists | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major oxides (w.%) | Min. | Max | Mean | Min. | Max | Mean | Min. | Max | Mean | |

| SiO2 | 0,01 | 57,74 | 98,02 | 85,00 | 64,79 | 89,52 | 72,26 | 52,92 | 95,78 | 81,56 |

| Al2O3 | 0,01 | 0,55 | 14,33 | 5,60 | 3,34 | 16,61 | 12,75 | 1,19 | 14,85 | 6,59 |

| Fe2O3 | 0,04 | 0,60 | 8,03 | 3,24 | 2,10 | 3,61 | 3,02 | 0,65 | 14,06 | 4,61 |

| MgO | 0,01 | 0,04 | 4,13 | 0,94 | 0,38 | 1,51 | 0,84 | 0,09 | 4,78 | 1,44 |

| CaO | 0,01 | 0,06 | 4,75 | 0,54 | 0,07 | 0,35 | 0,24 | 0,04 | 0,44 | 0,14 |

| Na2O | 0,01 | <0,01 | 0,42 | 0,11 | 0,07 | 8,00 | 1,34 | 0,01 | 0,09 | 0,04 |

| K2O | 0,01 | 0,03 | 3,59 | 1,32 | 2,06 | 9,21 | 6,99 | 0,11 | 3,61 | 1,93 |

| TiO2 | 0,01 | <0,01 | 0,75 | 0,34 | 0,08 | 0,48 | 0,36 | 0,01 | 1,63 | 0,46 |

| P2O5 | 0,01 | <0,01 | 0,16 | 0,07 | 0,03 | 0,13 | 0,10 | 0,02 | 0,16 | 0,07 |

| MnO | 0,01 | <0,01 | 0,47 | 0,1 | <0,01 | 0,07 | 0,04 | <0,01 | 0,07 | 0,03 |

| Cr2O3 | 0,002 | <0,002 | 0,015 | 0,01 | <0,002 | 0,004 | 0,004 | <0,002 | 0,036 | 0,02 |

| Sc (ppm) | 1 | <1 | 17 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 4,83 | <1 | 43 | 12,14 |

| Toplam/C | 0,02 | 0,02 | 2,54 | 0,27 | <0,02 | 0,06 | 0,03 | <0,02 | 0,79 | 0,15 |

| Toplam/S | 0,02 | <0,02 | 0,45 | 0,29 | <0,02 | 1,22 | 0,58 | <0,02 | 0,07 | 0,07 |

| Ateş Kaybı | -5,1 | 0,6 | 10,3 | 2,77 | 1,3 | 4,5 | 2,59 | 1 | 7,2 | 3 |

| Toplam | 0,01 | 99,98 | 99,81 | 99,92 | 99,82 | 99,96 | 99,86 | 99,79 | 99,97 | 99,91 |

| Trace-rare earth elements (ppm) | ||||||||||

| Ba | 1 | 21 | 428 | 216,36 | 142 | 866 | 572,67 | 36 | 281 | 150,13 |

| Rb | 0,1 | 4 | 173,6 | 60,31 | 97,2 | 442,2 | 344,45 | 10,2 | 191,1 | 95,44 |

| Sr | 0,5 | 10 | 59,2 | 24,06 | 30,8 | 171,8 | 98,68 | 16,2 | 149,6 | 51,06 |

| Nb | 0,1 | 0,5 | 13,3 | 5,03 | 2,00 | 7,1 | 5,54 | 0,4 | 11 | 4,88 |

| Hf | 0,1 | 0,1 | 4,5 | 1,76 | 0,6 | 3,5 | 2,73 | 0,2 | 3,3 | 1,76 |

| Th | 0,2 | 0,2 | 9,8 | 4,74 | 2,4 | 11,1 | 8,24 | 0,1 | 6,7 | 3,87 |

| Ta | 0,1 | 0,1 | 1,9 | 0,76 | 0,1 | 0,8 | 0,56 | 0,1 | 0,9 | 0,48 |

| V | 8 | <8 | 125 | 65,11 | 23 | 83 | 62,5 | 10 | 319 | 82,75 |

| Zr | 0,1 | 2 | 165 | 58,96 | 19,6 | 134,9 | 98,37 | 6 | 129,7 | 67,64 |

| Y | 0,1 | 0,2 | 25,4 | 12,87 | 4,1 | 26 | 12,47 | 2,7 | 30,1 | 13,48 |

| Cu | 0,1 | 6,8 | 75,9 | 23,09 | 6,6 | 34,6 | 15,63 | 13,9 | 54,6 | 28,9 |

| Pb | 0,1 | 16,6 | 171,3 | 54,11 | 7,2 | 102,1 | 43,11 | 13,7 | 128,1 | 46,68 |

| Zn | 1 | 18 | 88 | 51 | 22 | 97 | 47,75 | 16 | 128 | 61,88 |

| As | 0,5 | 9,7 | 615,2 | 120,07 | 2,3 | 413,7 | 137,95 | 10,9 | 422,4 | 158,64 |

| Sb | 0,1 | 3,1 | 258 | 40,05 | 1 | 28,8 | 11,36 | 3,6 | 58,9 | 22,7 |

| Ag | 0,1 | <0,1 | 2,9 | 0,9 | 0,1 | 2,6 | 0,46 | <0,1 | 10,4 | 1,84 |

| Au (ppb) | 0,5 | 2,5 | 7060,7 | 783,93 | 26,1 | 1376,5 | 389,39 | 18,7 | 903,1 | 267,5 |

| Hg | 0,01 | 0,02 | 0,11 | 0,05 | <0,01 | 0,66 | 0,16 | <0,01 | 2,87 | 0,44 |

| La | 0,1 | 0,6 | 27,7 | 11,76 | 7,5 | 23,6 | 19,53 | 2,4 | 23,3 | 13,03 |

| Ce | 0,1 | 0,5 | 56,6 | 22,37 | 12,6 | 47,8 | 34,85 | 3,4 | 45,4 | 23,56 |

| Pr | 0,02 | 0,08 | 6,33 | 2,6 | 1,43 | 5,08 | 3,84 | 0,54 | 5,54 | 2,93 |

| Nd | 0,3 | 0,3 | 22,6 | 9,73 | 5,7 | 18,3 | 13,85 | 2 | 21,8 | 11,61 |

| Sm | 0,05 | 0,16 | 4,66 | 2,11 | 1,09 | 3,65 | 2,78 | 0,55 | 4,29 | 2,51 |

| Eu | 0,02 | 0,02 | 1,16 | 0,53 | 0,22 | 1,09 | 0,77 | 0,1 | 0,94 | 0,57 |

| Gd | 0,05 | 0,36 | 5,01 | 2,3 | 1,12 | 3,4 | 2,69 | 0,72 | 4,19 | 2,63 |

| Tb | 0,01 | 0,02 | 0,81 | 0,36 | 0,13 | 0,55 | 0,39 | 0,08 | 0,76 | 0,4 |

| Dy | 0,05 | 0,1 | 4,43 | 2,11 | 0,78 | 3,55 | 2,16 | 0,48 | 3,3 | 2,27 |

| Ho | 0,02 | <0,02 | 0,9 | 0,49 | 0,13 | 0,82 | 0,45 | 0,09 | 1,17 | 0,49 |

| Er | 0,03 | 0,03 | 2,76 | 1,32 | 0,43 | 2,32 | 1,29 | 0,25 | 3,31 | 1,4 |

| Tm | 0,01 | 0,01 | 0,41 | 0,2 | 0,06 | 0,37 | 0,21 | 0,05 | 0,5 | 0,21 |

| Yb | 0,05 | 0,1 | 2,74 | 1,31 | 0,44 | 2,3 | 1,39 | 0,29 | 3,27 | 1,41 |

| Lu | 0,01 | 0,03 | 0,28 | 0,2 | 0,09 | 0,37 | 0,23 | 0,05 | 0,5 | 0,22 |

| Sample Type | Mean Eu/Eu* | La/Yb | La/Sm | LREE/HREE | Ʃ REE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz vein | 0,72 | 5,87 | 3,30 | 2,85 | 65,95 |

| Quartz feldspar porphyry | 0,82 | 9,84 | 4,41 | 4,04 | 81,06 |

| Quartz micaschist | 0,66 | 7,49 | 3,21 | 3,12 | 63,24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).