1. Introduction

The Feni Island group is part of the Tabar-Lihir-Tanga-Feni (TLTF) volcanic arc within the New Ireland Basin (NIB), New Ireland Province (NIP), northeast Papua New Guinea (PNG). NIP has a total population of 228,000-243035 [

1,

2] and is made up of several islands: New Ireland, New Hanover, Mussau, Djaul and the TLTF islands. The TLTF and NIB are bounded by New Ireland island to the west and Kilinailau Trench (KT) in the east. The TLTF, KT, Bougainville and Solomon Islands are part of a series of arcs and trenches within the seismically and volcanically active SW Pacific region.

Feni Island Group consists of Babase and Ambitle islands located between geographic coordinates 3° 45’S, 153°30’E and 4° 15’, 154° 00’ E, forming the southern end of the Pliocene to Holocene alkaline TLTF chain (refer to accompanying paper). The TLTF arc hosts significant gold reserves associated with alkaline magmatism at Lihir (~23 Moz Au) and Simberi (~2.2 Moz Au) mines [

3,

4]. Recent papers by Lindley [

5,

6,

7] and Brandl et al [

8] focus on the geology, mineral deposits, and the geotectonic evolution of Feni and the TLTF respectively.

In this paper, we present the petrography, mineralogy, and geochemistry of selected igneous rocks from Feni, particularly focusing on Ambitle Island, in conjunction with the TLTF regional geological framework in order to understand the magmato-tectonic processes that produced these rocks. This paper is preceded by a sister article by the same authors titled “PNG Geotectonics and the geological evolution of Feni” which discusses the major geotectonic terranes and geology of PNG, the Melanesian Arc, New Britain, New Ireland, TLTF, and the Feni Islands

The Feni islands were targeted as a natural laboratory of Au-rich alkaline to calc-alkaline volcanism. Fieldwork examined the structural and geological setting of Feni (Ponyalou et al, in review) and sampled a representative suite of rocks for petrographic, petrological, and geochemical research. Comparisons were also made with lavas from neighboring arcs which include the Quaternary New Britain arc, Manus back-arc basin, and Gallego in the Solomon arc. Gallego volcanic field (GVF) on Guadalcanal was also visited in 2009 and sampled as it is an adjacent arc continuing on from the NW-trending Manus-Kilinailau trench.

2. Background on alkalic magmatism in PNG & Oceania

Shoshonitic or alkaline rocks also occur in other parts of PNG. These include the Highlands (ie. Porgera, Crater Mountain, Mt Hagen, Mt Giluwe), Oro (ie. Mt Lamington pre-1951 volcanics), southeast Papuan Peninsula (i.e. Cloudy Bay volcanics), and Milne Bay (i.e. Kutu Volcanics, Gabahusuhusu Syenite) and are also closely linked to gold mineralization [

9,

10,

11]. Within the SW Pacific Region, shoshonitic alkalic rocks also occur in North Fiji and the Lau back-arc basin [

12,

13], Indonesia in the Sunda arc and Cadia, Australia [

14]. Unlike the voluminous calc-alkaline mafic, intermediate and porphyry Cu-Au magmas formed during subduction in island and magmatic arc settings, alkaline or shoshonitic magmas are formed post-subduction from low degree partial melting of subduction-modified lithospheric mantle during extension [

13,

15]. Post-subduction processes include slab roll back or slab delamination or slab tear [

15,

16].

Previous work published on the geology, alkalic magmatism, and porphyry-epithermal Cu-Au prospectivity of Ambitle include Johnson et al [

17], Heming [

18], Wallace et al [

19] and Licence et al [

20]. Heming [

18] described the undersaturated lavas on Ambitle as basanite, tephrite, trachyte, and ankaramitic (or pyroxene-rich) lavas. He observed olivine, clinopyroxene, plagioclase, and hauyne within the basanite, whereas in the tephrite, amphibole and mica were dominant in the absence of olivine and hauyne. He also noted that the lavas contained unusually high concentrations of incompatible trace elements relative to island arc basalts and andesites. Heming [

18] suggested that the undersaturated Ambitle lavas were most closely related to those from the Lesser Sunda arc in Indonesia. Wallace et al [

19] described the rocks of Feni as alkali basalt, tephrite, basanite, phonolitic tephrite, tephritic phonolite, trachybasalt, trachyandesite, transitional basalt and quartz-trachyte. The quartz-trachyte cumulodome is observed throughout the TLTF chain as the youngest and the most silica-saturated volcanic rock. Wallace et al [

19] noted that most of the Ambitle volcanic geochemical signatures were typical of island arcs, including the high concentration of incompatible (LIL) elements (ie Rb, Ba, Sr, K) and low Ti (which is generally high for most silica-undersaturated rocks from intercontinental arcs). In summary, the outcropping rocks from Ambitle and Babase are mostly feldspathoid-bearing mafic to intermediate alkaline volcanics and subvolcanic rocks with rare quartz-trachydacite porphyries. Drilling in the Kabang prospect on Ambitle by past companies intersected a syenite porphyry intrusive with prospective porphyry-epithermal alteration and mineralization at depth [

20]. Older company maps show a monzonite intrusive body at Matoff [

21] but this was not visited during this study (

Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Geology & sample location map of Feni Island Group. Geology modified after Wallace et al (1983) [

24] and Esso (1983) [

52].

Figure 1.

Geology & sample location map of Feni Island Group. Geology modified after Wallace et al (1983) [

24] and Esso (1983) [

52].

Figure 2.

SRTM Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of Feni Islands.

Figure 2.

SRTM Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of Feni Islands.

Figure 3.

Geology map of Ambitle modified after Esso (1983) [

52]. Red circles represent samples collected for this study.

Figure 3.

Geology map of Ambitle modified after Esso (1983) [

52]. Red circles represent samples collected for this study.

3. Materials and Methods

Fifty-two (52) rock samples comprising twenty-one (21) float and thirty-one (31) outcrop samples were collected from Feni during two field trips in September and November 2009 (

Figure 3). A third field trip was carried out in January 2011 where outcrop samples were collected from the Nanum and Kabang areas (

Figure 3) but these were not analysed. The 52 samples from the 2009 trips include 41 volcanic and volcaniclastic rock samples, 3 volcanogenic mudstone-siltstone samples and 8 geothermal sinter and clay deposits. During the first trip (abbreviated as Feni 1), 21 igneous float samples were collected from both Babase and Ambitle islands, whilst 8 insitu silica sinter and hydrothermal clay samples were collected from the geothermal fields of Waramung and Kapkai on Ambitle Island. During the second field trip (abbreviated Feni 2), several outcrops on Ambitle Island were mapped and sampled at the following localities: Natong, Niffin, Balangus and Olu Creek. The third trip in January 2011 was conducted to Nanum and Kabang on Ambitle with E. Scott who had collected a wood sample from a resedimented ash deposit and carbon-dated it to 2100 years [

22](Scott, 2011). For the purpose of this paper and limited space, a representative suite has been selected for whole rock geochemical data presentation (

Table 2 and

Table 3). The full analytical data of all 52 samples are appended.

The samples collected were analysed petrographically and geochemically in Papua New Guinea and the United Kingdom (UK). Thin sections and polished sections were prepared at the Earth Sciences Division (ESD), University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG), and at the Geology Department of the University of Leicester (UOL) in the UK. The sample preparation and geochemical analytical techniques are described herein. All rock samples, including a few with weathered surfaces, were crushed to rock powder using agate balls in a Retsch Planetary Mill at the UOL.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. The crushed material of the 31 samples (i.e. F1-F36) from the Feni 1 trip were submitted to OMAC Laboratories Ltd in Ireland for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis of major and trace elements using the lithium borate fusion dissolution technique. Aqua regia dissolution was also applied on samples F1-36 for base and precious metal analysis. QAQC analyses of blanks, duplicates, and standards are included in the online

Supplementary Information.

X-ray Fluorescence. Twenty-three (23) samples (OPBA1-OPOL1) from the Feni 2 trip were analyzed for major and trace elements with the PANalytical Axios Advanced XRF X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer and PANalytical SuperQ software at the UOL Geology Department. The crushed samples were initially prepared into a pressed powder pellet for trace element analysis and a glass bead made from the fusion of the rock powder with lithium metaborate or tetraborate for major elemental analysis. Instrument calibration and precision-accuracy measurements were conducted using various reference materials at the UOL geology lab. Counting statistic errors are available within the raw XRF data spreadsheet under sheet “axrht322 cse”.

The left-over rock powder of the Feni 2 samples were also submitted to OMAC Laboratories for whole rock geochemical and gold analysis. See

Supplementary Data for all XRF and ICP MS results. Both the ICP-MS and XRF datasets were used for whole rock geochemical analysis in the creation of bivariate plots, ratios and discrimination diagrams and are labelled accordingly in the relevant figures. In addition, the same datasets were cleaned to exclude all weathered and altered igneous rocks and those possessing a loss on ignition (LOI) > 5% resulting in a total of 26 fresh igneous samples from Feni. The Feni rocks geochemical data are compared with the volcanic and intrusive rocks from the Gallego Volcanic Field (GVF) in Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands sampled by the same authors in 2009 and previously published by Petterson et al (2011) [

23]. Comparisons are also made with rocks from other arcs in PNG using published and unpublished data.

Electron Microprobe. Electron microprobe analysis (EMPA) was conducted using the JEOL 8600 Superprobe at UOL for the determination of major elemental oxides in the polished sections of selected igneous rocks. Prior to analysis, the polished sections were coated with carbon to prevent ionization and the subsequent damage of minerals by the electron beam. The microprobe uses a wavelength dispersive system where a 30 nA current and a 15 kV accelerating voltage were used for all analyses. A 10 µm beam was employed for most analysis of feldspars and micas whilst a 5 µm beam was used for other minerals. Precision for electron probe analysis, calculated from counting statistics, was generally better than ±1% for measurements > 10 wt %, and better than ±5% for contents > 0.5 wt %. Trace element analysis of mineral phases cannot be done using the electron microprobe but is usually achieved via laser ablation ICPMS (LA ICPMS) and secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS).

4. Results

The results of this study are presented according to field or outcrop observations (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, refer to accompanying paper in same issue), alkali vs silica volcanic rock classification plots (

Figure 4), petrography (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), mineral chemistry (

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4;

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16) and whole-rock geochemistry. Mineral chemistry and microscopic petrography are complementary to each other. The whole-rock geochemistry section is further subdivided into major elements, trace elements, and rare earth elements (REE). Trace element data is also used to produce tectono-discrimination diagrams and prospectivity or Cu-Au fertility plots.

4.1. Alkali vs silica volcanic rock classification

The Feni volcanic rocks are mainly shoshonitic or alkaline in chemistry and include basalt, trachybasalt, trachyandesite, phonotephrite and trachydacite (

Figure 4). In comparison, Gallego rocks in the Solomon arc are mainly calc-alkaline andesite and basaltic andesite with minor gabbro (plotting in the basalt field in

Figure 4). Pyroclastic and resedimented ash flow deposits were also noted on Ambitle at Niffin and near Kabang but were not plotted in

Figure 4. Data from the New Britain volcanic arc (labelled NBT for New Britain Trench), Solomon Slab Basalt (from the sea floor that is subducting at the New Britain Trench) and the Manus MORB were adopted from [

24] Woodhead et al (1998) and plotted for comparison.

The Feni shoshonitic volcanic rocks have SiO2 values ranging between 45% and 67% and K2O+Na2O values falling between 3% and 12%. In contrast, the Gallego volcanic rocks from Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, and some NBT rocks are medium K calc-alkaline arc with SiO2 values ranging between 40% and 62% and K2O+Na2O values of between 1 and 7%. Low K tholeiitic rocks include the Solomon slab (subducting under the New Britain trench), some New Britain arc volcanics and Manus MORB [

24] (Woodhead et al., 1998).

4.2. Petrography & Mineral Chemistry

The primitive suites are the mafic or basic volcanics which include basalt (F4, F7, F11, F15, F16, F19, OPN6, OPN7, OPN8A and OPOL1) and trachybasalt (F2, F5, F8, F17, and OPBA1) as depicted in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Some samples look basaltic (OPN3, F6) and trachyandesitic (OPN8B) but plot in the phonotephrite field of the TAS plot (

Figure 4). The intermediate rocks are trachyandesite porphyries from Natong (OPNA1, OPNA3A, OPNA3B, OPNA4, OPNA5 and OPN5) and an evolved phonotephrite from Niffin (OPN8B) as shown in the polished sections in

Figure 8. The most felsic magmas are the trachydacite porphyries (F12, F33) also depicted in

Figure 8. The primitive basaltic and fine-grained phonotephrite magmas contain feldspathoids, alkali feldspars, clinopyroxene and minor olivine (

Figure 5 and

Figure 7). Hornblende occurs in trachyandesite and phonotephrite from Natong and Niffin respectively (

Figure 5). Biotite is most abundant in the felsic trachydacite porphyry but also occurs minimally in trachyandesite and phonotephrite almost as an accessory mineral in the hornblende-rich suites (

Figure 5). Remnant clinopyroxene appears to have been replaced by hornblende in the trachyandesite and phonotephrite samples. Feldspathoid minerals, mainly leucite and nepheline, is notable in all the basalt and trachybasalt rocks and the mafic or more primitive phonotephrite samples (ie OPN3, OPN8A). Nosean was potentially noted in the Natong trachyandesite. Apatite is present throughout all rock types but is most abundant in the hornblend-bearing trachyandesite at Natong and the evolved hornblende-phonotephrite at Niffin. Apatite abundance is strongly associated with hornblende clusters (

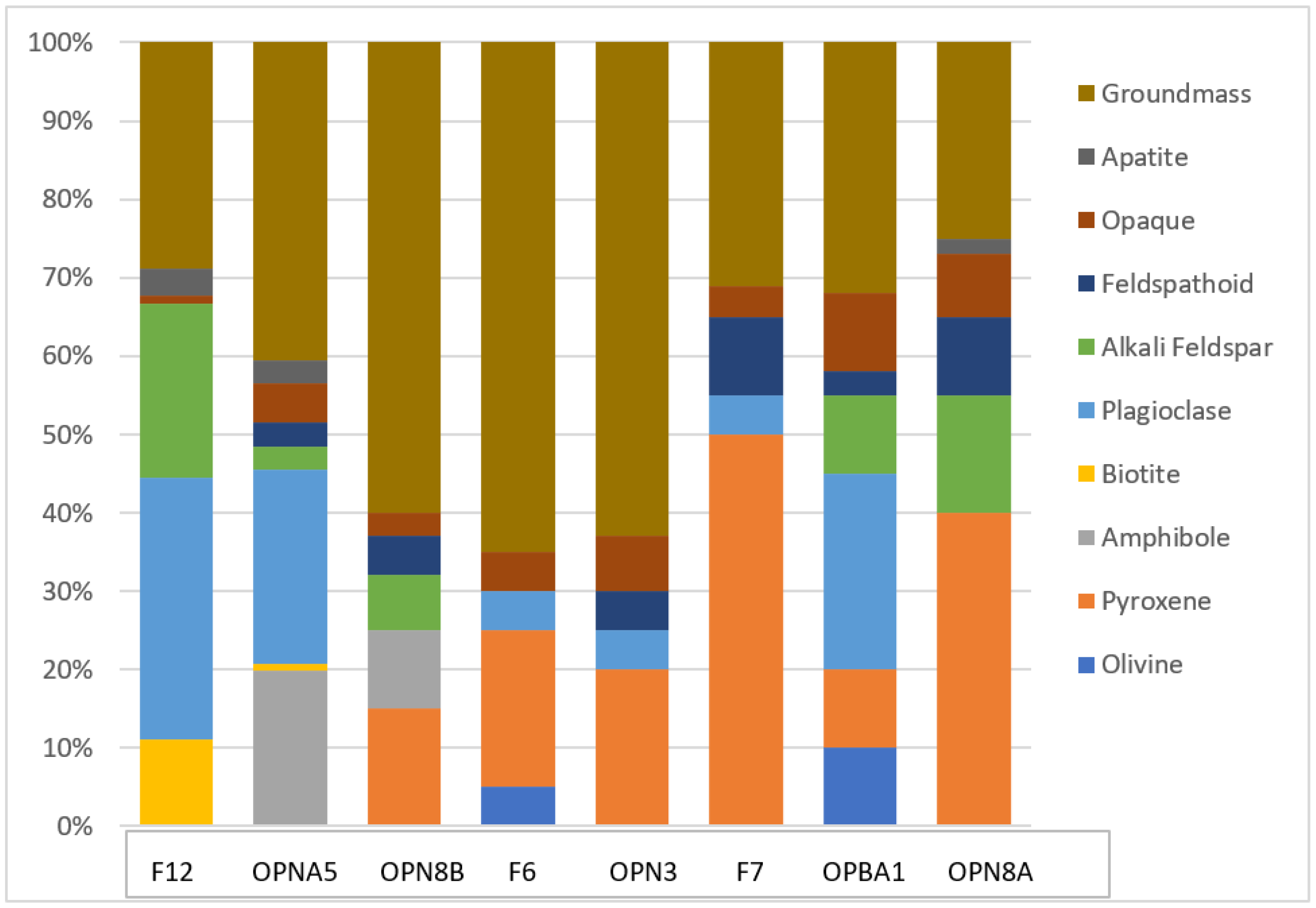

Figure 5).

Figure 4.

TAS classification diagram (Le Maitre et al., 1989) [

25] & subdivision of Subalkalic Rocks using K2O vs SiO2 (Peccerillo and Taylor, 1976) [

26] of Feni volcanic rocks (black circles) vs Gallego rocks (blue circles), New Britain volcanic arc field (pink), Solomon Slab basalt (green), and Manus MORB (red). NBT and Manus MORB data are taken from Woodhead et al. (1998) [

24] with permission.

Figure 4.

TAS classification diagram (Le Maitre et al., 1989) [

25] & subdivision of Subalkalic Rocks using K2O vs SiO2 (Peccerillo and Taylor, 1976) [

26] of Feni volcanic rocks (black circles) vs Gallego rocks (blue circles), New Britain volcanic arc field (pink), Solomon Slab basalt (green), and Manus MORB (red). NBT and Manus MORB data are taken from Woodhead et al. (1998) [

24] with permission.

Figure 5.

Modal abundance of minerals observed in thin section, as determined from gridding of thin section scans (minimum 200 points). Samples are ordered from felsic to mafic from left to right. F12 is trachydacite. OPNA5 is hornblende trachyandesite. OPN8B, F6, OPN3 are phonotephrite samples. Basalt samples are F7, OPBA1 and OPN8A.

Figure 5.

Modal abundance of minerals observed in thin section, as determined from gridding of thin section scans (minimum 200 points). Samples are ordered from felsic to mafic from left to right. F12 is trachydacite. OPNA5 is hornblende trachyandesite. OPN8B, F6, OPN3 are phonotephrite samples. Basalt samples are F7, OPBA1 and OPN8A.

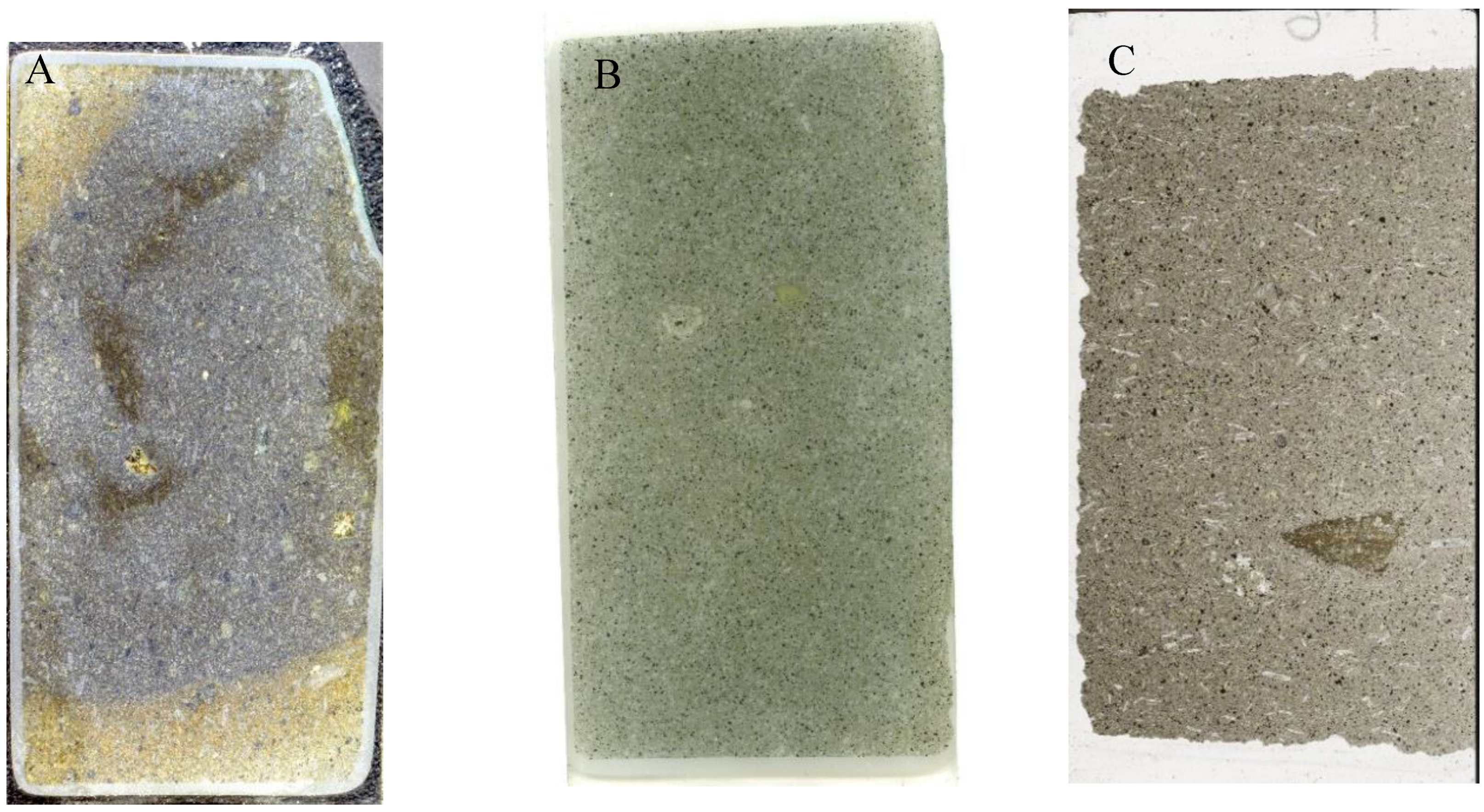

Figure 6.

Polished section scans of mafic volcanic rocks from Ambitle. A) OPBA1 trachybasalt from Balangus. B) OPN3 aphanitic, grey phonotephrite outcrop from Niffin C) F6 phonotephrite float sample.

Figure 6.

Polished section scans of mafic volcanic rocks from Ambitle. A) OPBA1 trachybasalt from Balangus. B) OPN3 aphanitic, grey phonotephrite outcrop from Niffin C) F6 phonotephrite float sample.

Mafic volcanic lava suite

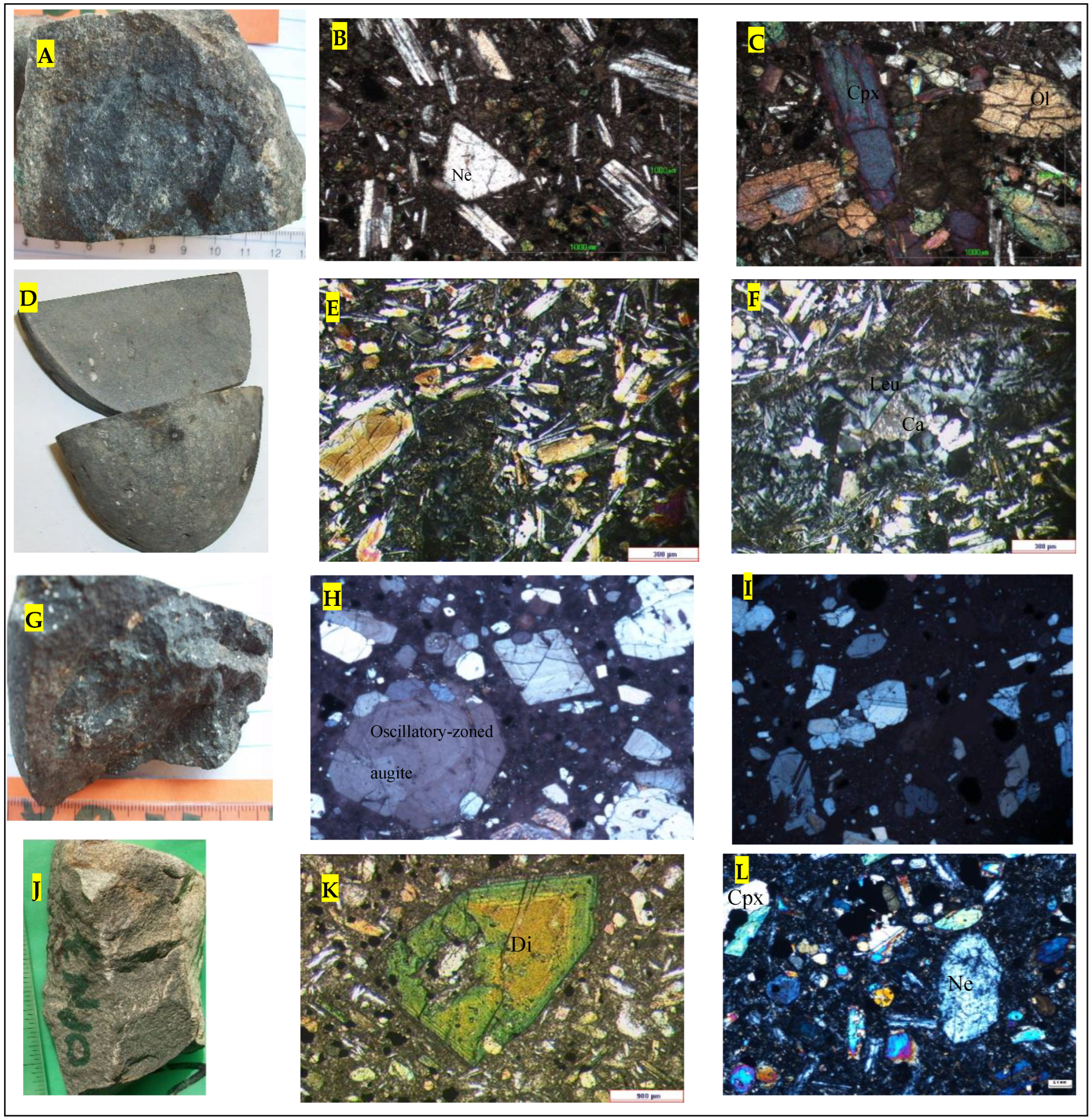

Basaltic rocks are mainly aphanitic or fine-grained, vesicular, amygdaloidal and microporphyritic in texture, with minor glass in the matrix. Clinopyroxene, particularly augite is the essential mineral phase observed in thin section with minor or no olivine. These ferromagnesian minerals occur as phenocrysts (1-3 mm), microphenocrysts (< 1mm), and glomerocrysts (2-4 mm) and rarely as xenocryst (> 4 mm) in a finer matrix of the same composition. Other essential minerals include plagioclase and feldspathoid, followed by opaques (titano-magnetite) and apatite as accessory minerals. Secondary minerals that form after the alteration of feldspars or that infill vesicles include clay, calcite and zeolite. It was noted that the basaltic rocks of Feni are dominated by clinopyroxene but a few contain olivine xenocrysts that are interpreted to be from the lower parts of the mantle and were not formed where the basaltic melt originated.

Olivine-Clinopyroxene Basalt

Olivine-clinopyroxene bearing basalt samples include F5, F11 and OPN7. OPN7 sampled from a Niffin basalt outcrop is dominated by diopside followed by forsteritic olivine with magnesium-rich cores. F11 consists of euhedral clinopyroxene megacrysts up to 15 mm in length within a groundmass of smaller fractured fragments and altered olivine grains pseudomorphed or coated by an oxide mineral.

Trachybasalt OPBA1 (

Figure 6A) is another olivine-clinopyroxene bearing basaltic rock sampled from a massive lava flow at Balangus Creek, eastern Ambitle. It is melanocratic, fine-grained or microcrystalline with flow-oriented plagioclase grains, and abundant mafic lath-shaped clinopyroxene crystals in hand-specimen and exhibiting a seriate texture under the microscope (

Figure 7 A-C). The modal mineral composition is plagioclase (20%); sanidine (15%); olivine (20%); clinopyroxene (20%); accessory oxides (~15%); and minor nepheline (~10%) set in a finer-grained matrix of similar composition. The plagioclase phases include labradorite laths exhibiting multiple twinning and tabular anorthite with compositional zoning. In

Figure 7B, a euhedral nepheline crystal is surrounded by labradorites oriented in a trachytic flow texture under crossed polars. Sanidine grains are flow-oriented and diagnostically simple-twinned. A clinopyroxene-olivine glomerocryst is observed microscopically (

Figure 7C) and in hand-specimen. The subhedral round and elongate olivine crystals lack cleavage and typically display curved fractures and third order purple-green interference colors.

Clinopyroxene Basalt

F7 is a microporphyritic basaltic sample with secondary calcite amygdules in hand-specimen (

Figure 7D). In thin section, F7 essentially comprises augite (30%) and acicular plagioclase intergrowths (35%) with minor leucite (~15%) and secondary calcite amygdules (~5%) in a finer matrix of the same composition (~10%). A rectangular or prismatic augite crystal (0.35 mm long) exhibits hour-glass extinction, good partings and a first-second order yellow-pink interference colour (

Figure 7E) under crossed-polars (mid-left) surrounded by needle-like laths of plagioclase and second order yellow-pink augite grains in F7. Other major minerals include plagioclase (sanidine, andesine), feldspathoid and accessory magnetite. The feldspathoid minerals observed in thin section were nepheline and leucite. The leucite grains (

Figure 7F) exhibit diagnostic radial and complex twinning under crossed polars with amygdular calcite in between. Secondary minerals include clay, calcite (

Figure 7D, F) and zeolite.

OPN8A is sampled from a pillow basalt outcrop along a westerly tributary of the Niffin River. It is a melanocratic, aphanitic, and pyroxene-phyric basalt with secondary calcite amygdules (~5%) on the surface (

Figure 7G). In thin section, the dominant phenocryst phase is clinopyroxene (augite) ~45-50% followed by feldspathoids and opaque magnetite set in a finer-grained matrix of similar mineralogy. This basalt is devoid of plagioclase, olivine or amphibole minerals. Augite phenocrysts occur as euhedral prisms and tabular, eight-sided oscillatory-zoned crystals sometimes with exsolution lamellae, surface fractures and perfect cleavage (

Figure 7 H, I). Microphenocrysts of clinopyroxene display hour-glass extinction and Carlsbad twinning.

Pyroxene-olivine Phonotephrite

Phonotephrite (

Figure 7 J) is a medium to light grey, fine-grained volcanic rock consisting of olivine, pyroxene, plagioclase and feldspathoid in the more primitive mafic samples, whereas in the evolved units, the texture is porphyritic and contains hornblende and minor pyroxene (without olivine). Phonotephrite samples include cobble floats from Waramung beach (F6, F9) and outcrop samples (OPN3, OPN8B) from the Niffin area. Two varieties are recognized: olivine-pyroxene phonotephrite (OPN3, F6) and hornblende-clinopyroxene phonotephrite (OPN8B).

Figure 7 K shows a zoned clinopyroxene (diopside) megacryst under crossed polars that was also analysed by electron microprobe (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

Figure 7.

Hand-specimen and photomicrographs of basaltic rocks. (A) Trachybasalt OPBA1 from Balangus, eastern Ambitle (B) Euhedral nepheline surrounded by labradorites oriented in a trachytic flow texture (xpl). (C) Clinopyroxene-olivine glomerocryst under xpl, OPBA1. (D) Aphanitic basalt F7 hand specimen with calcite amygdules. (E) Rectangular augite crystal 0.35 mm with hour glass extinction in xpl (mid-left). Note needle-like laths of plagioclase and second order yellow-pink augite grains. (F) Amygdular calcite in between leucite grains exhibiting radial and complex twinning under xpl. Basalt F7. (G) OPN8A pillow basalt from Niffin with calcite amygdules (H) Oscillatory zoned augite in pyroxene-phyric basalt OPN8A (I) Exsolution lamellaes in clinopyroxene. Titanomagnetite associated with cpx, OPN8A. (I) Phonotephrite OPN3 sample from Niffin. (K) Zoned clinopyroxene (diopside) megacryst under XPL, OPN3. Fig 15-16 show the microprobe analysis of this crystal. (F) OPN3 photomicrograph of numerous clinopyroxene crystals and a nepheline (Ne) crystal.

Figure 7.

Hand-specimen and photomicrographs of basaltic rocks. (A) Trachybasalt OPBA1 from Balangus, eastern Ambitle (B) Euhedral nepheline surrounded by labradorites oriented in a trachytic flow texture (xpl). (C) Clinopyroxene-olivine glomerocryst under xpl, OPBA1. (D) Aphanitic basalt F7 hand specimen with calcite amygdules. (E) Rectangular augite crystal 0.35 mm with hour glass extinction in xpl (mid-left). Note needle-like laths of plagioclase and second order yellow-pink augite grains. (F) Amygdular calcite in between leucite grains exhibiting radial and complex twinning under xpl. Basalt F7. (G) OPN8A pillow basalt from Niffin with calcite amygdules (H) Oscillatory zoned augite in pyroxene-phyric basalt OPN8A (I) Exsolution lamellaes in clinopyroxene. Titanomagnetite associated with cpx, OPN8A. (I) Phonotephrite OPN3 sample from Niffin. (K) Zoned clinopyroxene (diopside) megacryst under XPL, OPN3. Fig 15-16 show the microprobe analysis of this crystal. (F) OPN3 photomicrograph of numerous clinopyroxene crystals and a nepheline (Ne) crystal.

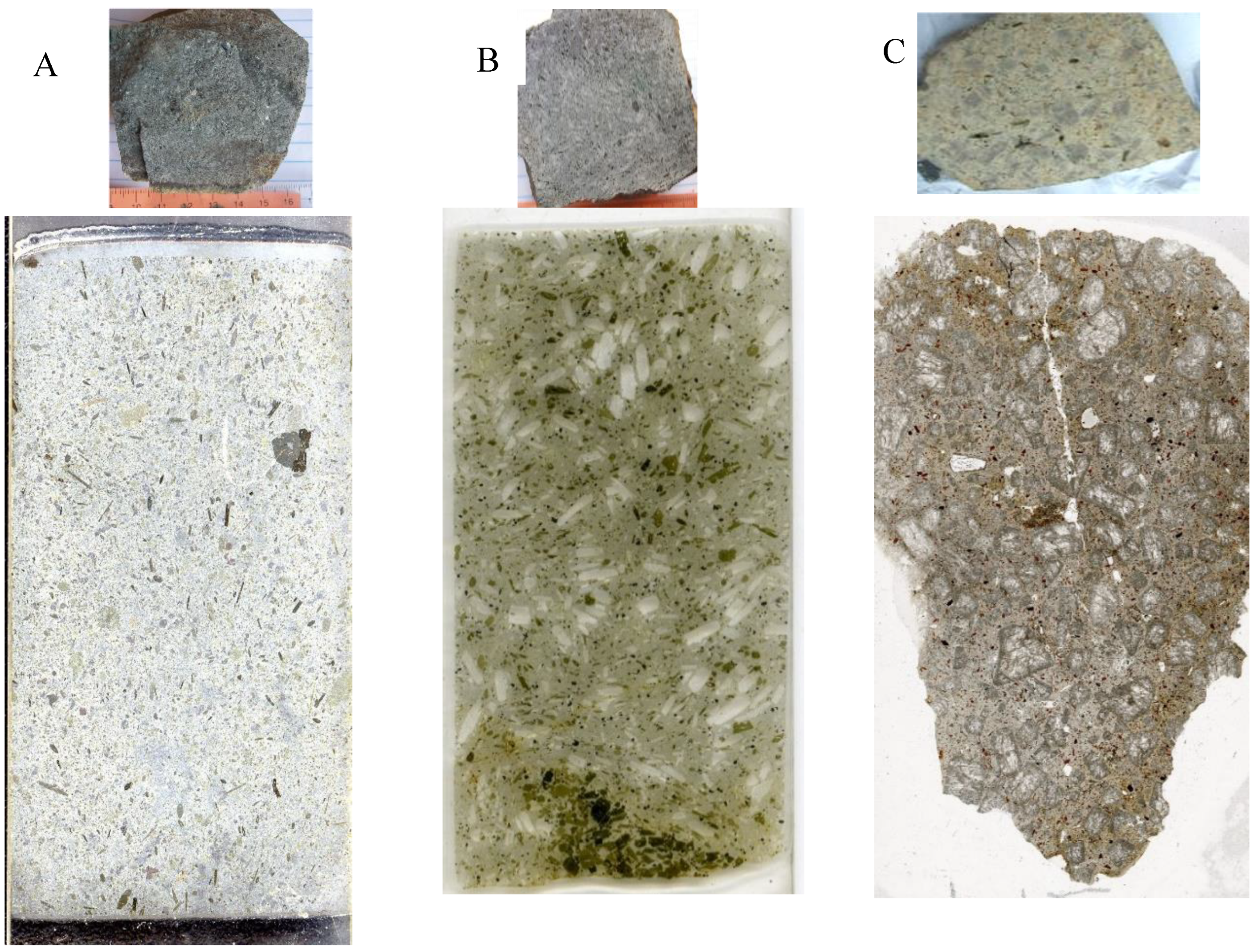

Clinopyroxene-hornblend Phonotephrite

OPN8B is a light-grey, mesocratic, slightly weathered porphyritic rock consisting of hornblende laths (5%), clinopyroxene (10%), feldspathoid (3%) and alkali feldspar (3%) set in finer grained, light grey matrix (

Figure 8A;

Figure 9 A-C). Hornblende or amphibole composition is primarily magnesiohastingsite (

Figure 15) and occurs as spindle-shaped laths, diamond-shaped grains, and coarse-grained megacryst (>2.5 mm) that are sometimes simple-twinned. Two types of clinopyroxene based on the crystal habit were observed optically. The euhedral clinopyroxene is 8-sided and exhibits third-order yellow and pink interference colours (

Figure 9A). Anhedral clinopyroxene grains, which are rare occurrences, appear to have been remelted or corroded on the edges and exhibit third-order blue and purple birefringence, inclined extinction, good cleavage, and occasional exsolution lamellaes (

Figure 9B). Sanidine or orthoclase is diagnostically simple twinned with low order grey and white birefringence. Minor or rare anhedral feldspathoid is also present.

Hornblend Trachyandesite

Trachyandesite (

Figure 8B) is an intermediate, grey subvolcanic or hypabyssal intrusive rock of porphyritic, equigranular, sub-porphyritic and trachytic texture mainly occuring as outcrops along the Natong Creek. Primary minerals are hornblende (25%) and albite (25%) phenocrysts with the occasional remnant pyroxene 5-10% (being altered to amphibole and chlorite), alkali feldspar and hauyne ranging from 2-4 mm in grain size, and set in a finer groundmass of variable alteration. Hornblende crystals form clusters or glomerocrysts (

Figure 9 G-I). Apatite appears to form euhedral crystals interstitially between the hornblende clusters or glomerocryst. Other accessory minerals include magnetite and ilmenite. Smectite clay, chlorite, and epidote alteration are common in propylitic-altered portions of the outcrop whilst fault-controlled quartz-clay-pyrite veins were observed in the field. The albite crystals are mainly tabular or prismatic, multiple-twinned and sometimes oscillatory-zoned. Plagioclase laths may also assume flow orientation as seen in the trachytic texture. Mineral impingement and embayment are observed in some plagioclase crystals and indicate high energy and mechanical movement during magma flow. The hornblende is determined as Mg-rich or magnesiohastingsite [

27,

28] (Ridolfi et al., 2010; Leake et al., 1997) with microprobe analysis displayed in

Table 2 and

Figure 15. Under the microscope, the Mg-rich hornblende is diagnostically simple-twinned, diamond-shaped, length slow, highly pleochroic with green-brown colours and exhibiting two sets of diagnostic cleavage intersecting at ~56°and ~124°.

Biotite Trachydacite

The feldspar-biotite trachydacite (F12, F33) is a pinkish-white, leucocratic crowded porphyry with coarse cumulate K-feldspar and albite phenocrysts (~40 vol%) ranging from 2- 5 mm and minor biotite microcrystals (0.2-0.6 mm) and accessory apatite (3 mm) set in a white, quartz-albite-sericite altered groundmass (

Figure 8 C). The source outcrop is inferred to be in the centre or south of Ambitle Island. In thin section, the crowded porphyry comprises albite (30%), K-feldspar-perthite pseudomorph (10%), alkali feldspar (10%), biotite (10%), opaque minerals (2%), hydrothermal quartz (2%) and accessory apatite (1-3%) and trace pyrite (0.1%) in a clay-silica altered groundmass. The main cumulate phases are albite and alkali feldspar with overprinting cloudy sericite and cancrenite alteration (

Figure 8J). Cancrenite is colourless under PPL but exhibit highly birefringent blues under XPL. Feldspar phenocrysts occur as square and hexagonal euhedral crystals that are sometimes simple-twinned (

Figure 8K). Albite occurs together with K-feldspar or perthite distinguished by perthitic twinning. Accessory apatite (~1%) is colorless, prismatic mineral, with high relief and low birefringence (

Figure 8L). Opaque minerals possibly iron and titanium oxides make up <2% of the rock. Brown and strongly pleochroic biotite laths occur in the matrix as microcrystals (< 1mm) oriented in all directions (

Figure 8G). The igneous biotite is partially replaced by phlogopite potentially indicative of a weak potassic alteration phase cross-cut by late hydrothermal quartz as micro-veinlets and vuggy infill. Fine-grained disseminated pyrite (0.1 %) is associated with the late argillic alteration (silica-clay-pyrite) overprinting the K-silicate alteration.

Figure 8.

Polished section scans and hand specimens of intermediate and felsic subvolcanic rocks from Ambitle. (A) Hornblende-phyric phonotephrite OPN8B sampled from outcrop in Niffin. (B) OPNA5 Trachyandesite hornblende porphyry from Natong. (C) Trachydacite porphyry (float) from Waramung Beach that may have come from the quartz-trachyte cumulodomes in the Central Caldera area.

Figure 8.

Polished section scans and hand specimens of intermediate and felsic subvolcanic rocks from Ambitle. (A) Hornblende-phyric phonotephrite OPN8B sampled from outcrop in Niffin. (B) OPNA5 Trachyandesite hornblende porphyry from Natong. (C) Trachydacite porphyry (float) from Waramung Beach that may have come from the quartz-trachyte cumulodomes in the Central Caldera area.

Figure 9.

Thin section photomicrographs of evolved crustal rocks from Ambitle Island: phonotephrite OPN8B from Niffin (A-C), hornblende-feldspar trachyandesite porphyry OPNA5 from Natong (D-I) and biotite-feldspar trachydacite porphyry F12 float from Waramung Beach (J-L). (A) 8-sided augite (aug) crystal surrounded by amphibole and clinopyroxene microcrystals and opaques, OPN8B, FOV 2.1 mm, PPL view. (B) Corroded clinopyroxene (cpx) megacryst with exsolution lamellae, OPN8B, FOV 2.1 mm, XPL view. (C) Hornblend (hb) megacryst, OPN8B, FOV 2.1 mm, PPL view. (D) Perthitic alkali feldspar (a-fspar), euhedral apatite (ap) and hornblende lath, OPNA5. (E) Simple-twinned sanidine, hornblende and smaller albite grains, OPNA5. (F) Zoned anorthite (an) in OPNA5 under XPL. (G) XPL & (H) PPL images of coarse twinned hornblende crystal, smaller apatite grains, and Ti-magnetite as opaques (op) in glomerocryst within OPNA5. (I) PPL image of numerous hornblende crystals with diagnostic diamond shape and intersecting inclined cleavages, OPNA5. (J) Sericite-clay altered cumulate hexagonal albite (fspar) crystals ~4-5 mm and smaller biotite (bt) ~0.5 mm grains in ppl, trachydacite sample F12. (K) Simple-twinned K-feldspar ~ 4mm long, F12. (L) Apatite grain (3 mm) in sample F12.

Figure 9.

Thin section photomicrographs of evolved crustal rocks from Ambitle Island: phonotephrite OPN8B from Niffin (A-C), hornblende-feldspar trachyandesite porphyry OPNA5 from Natong (D-I) and biotite-feldspar trachydacite porphyry F12 float from Waramung Beach (J-L). (A) 8-sided augite (aug) crystal surrounded by amphibole and clinopyroxene microcrystals and opaques, OPN8B, FOV 2.1 mm, PPL view. (B) Corroded clinopyroxene (cpx) megacryst with exsolution lamellae, OPN8B, FOV 2.1 mm, XPL view. (C) Hornblend (hb) megacryst, OPN8B, FOV 2.1 mm, PPL view. (D) Perthitic alkali feldspar (a-fspar), euhedral apatite (ap) and hornblende lath, OPNA5. (E) Simple-twinned sanidine, hornblende and smaller albite grains, OPNA5. (F) Zoned anorthite (an) in OPNA5 under XPL. (G) XPL & (H) PPL images of coarse twinned hornblende crystal, smaller apatite grains, and Ti-magnetite as opaques (op) in glomerocryst within OPNA5. (I) PPL image of numerous hornblende crystals with diagnostic diamond shape and intersecting inclined cleavages, OPNA5. (J) Sericite-clay altered cumulate hexagonal albite (fspar) crystals ~4-5 mm and smaller biotite (bt) ~0.5 mm grains in ppl, trachydacite sample F12. (K) Simple-twinned K-feldspar ~ 4mm long, F12. (L) Apatite grain (3 mm) in sample F12.

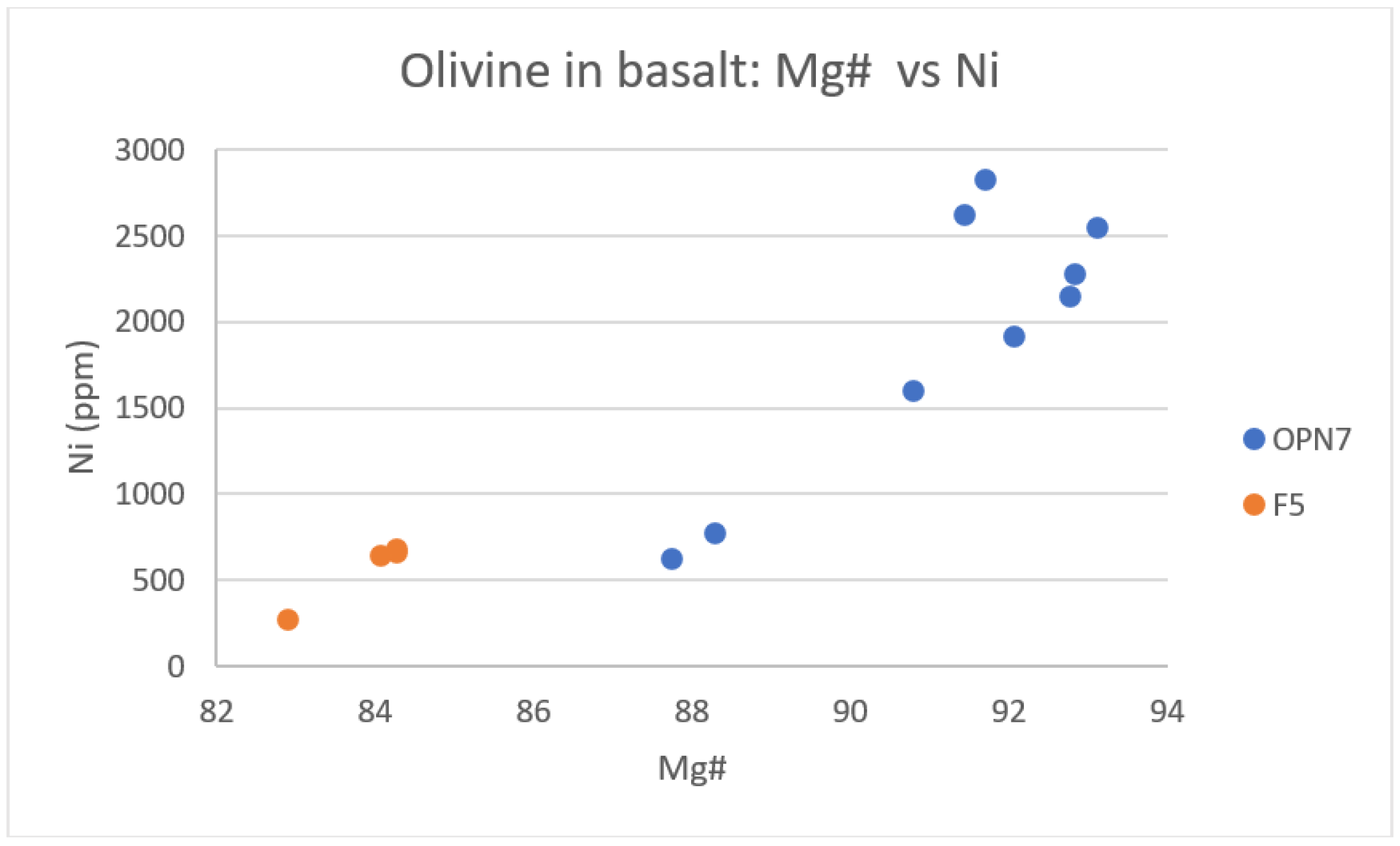

Olivine

Olivine occurs as phenocrysts or xenocrysts (<10 vol%) in some basalt and trachybasalt. Electron microprobe analysis was conducted on olivine crystals in basalt insitu sample OPN7 from Niffin and a float basalt sample F5 from Ambitle Island. The olivine xenocryst in OPN7 is forsteritic in composition (

Table 1;

Figure 10) displaying a negative linear trend for CaO and a positive correlation with NiO (

Figure 11). Olivine composition in OPN7 (

Table 1) varied from Fo

87 to Fo

94 [Fo=100×molar Mg/(Mg+Fe)], Mg# 88-93 with a NiO content of 0.10 to 0.32 wt % (or 778 - 2546 ppm) and CaO content of 0.06 to 0.38 wt %. Basalt sample F5 also contains olivine crystals but were of lower forsteritic composition at Fo

82 to Fo

84 and Mg# 82.9-84.3 (

Figure 10). Olivine composition (Te, Fa, Fo, Ca-Ol) was calculated from Mineral Formulae Recalculation (carleton.edu).

Table 1.

Electron microprobe analyses for olivine in basalt sample OPN7.

Table 1.

Electron microprobe analyses for olivine in basalt sample OPN7.

| Sample |

OPN7 |

OPN7 |

OPN7 |

OPN7 |

| Point |

12 |

13 |

14 |

59 |

| Job |

emc02 |

emc02 |

emc02 |

emc02 |

| SiO2 wt% |

40.01 |

41.86 |

39.88 |

41.30 |

| Cr2O3 wt% |

0.10 |

0.06 |

0.00 |

0.07 |

| FeO wt% |

6.90 |

7.00 |

10.78 |

6.79 |

| MnO wt% |

0.06 |

0.10 |

0.55 |

0.14 |

| MgO wt% |

50.19 |

50.42 |

45.58 |

51.63 |

| CaO wt% |

0.10 |

0.07 |

0.30 |

0.06 |

| NiO wt% |

0.29 |

0.27 |

0.10 |

0.32 |

| Total |

97.64 |

99.79 |

97.20 |

100.32 |

| Ni (ppm) |

2278.82 |

2145.234 |

777.942 |

2545.992 |

| Mg# |

93 |

93 |

88 |

93 |

| Te (mole%) |

0.061 |

0.000 |

0.601296 |

0.110 |

| Fo (mole%) |

92.6 |

93.8 |

87.4 |

94.02 |

| Fa (mole%) |

7.146 |

6.105 |

11.5952 |

5.8 |

| Ca-Ol (mole%) |

0.127 |

0.079 |

0.414751 |

0.071 |

Figure 10.

Ternary plot of olivine crystals from basalt sample OPN7 and F5 showing mainly forsterite (Mg

2SiO

4) composition. OPN7 is more forsteritic or magnesium-rich than F5. Fay + Teph is short for Fayalite + Tephroite (Fe

2SiO

4 + Mn

2SiO

4). EMPA data plotted in

www.ternaryplot.com.

Figure 10.

Ternary plot of olivine crystals from basalt sample OPN7 and F5 showing mainly forsterite (Mg

2SiO

4) composition. OPN7 is more forsteritic or magnesium-rich than F5. Fay + Teph is short for Fayalite + Tephroite (Fe

2SiO

4 + Mn

2SiO

4). EMPA data plotted in

www.ternaryplot.com.

Figure 11.

NiO and CaO vs Forserite mole % in Olivine in basalt OPN7. NiO positively correlates with forsterite. CaO decreases as Fo composition increases.

Figure 11.

NiO and CaO vs Forserite mole % in Olivine in basalt OPN7. NiO positively correlates with forsterite. CaO decreases as Fo composition increases.

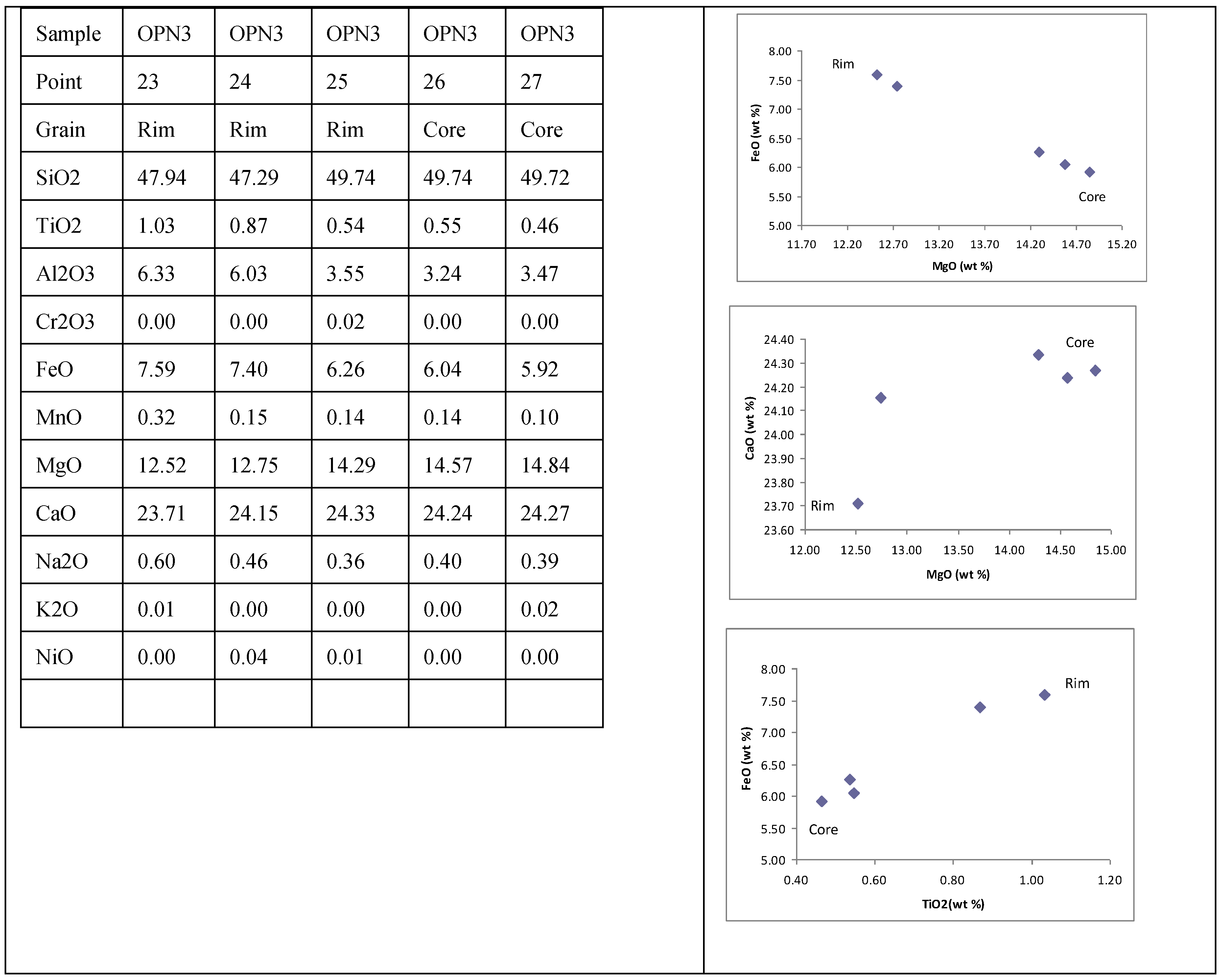

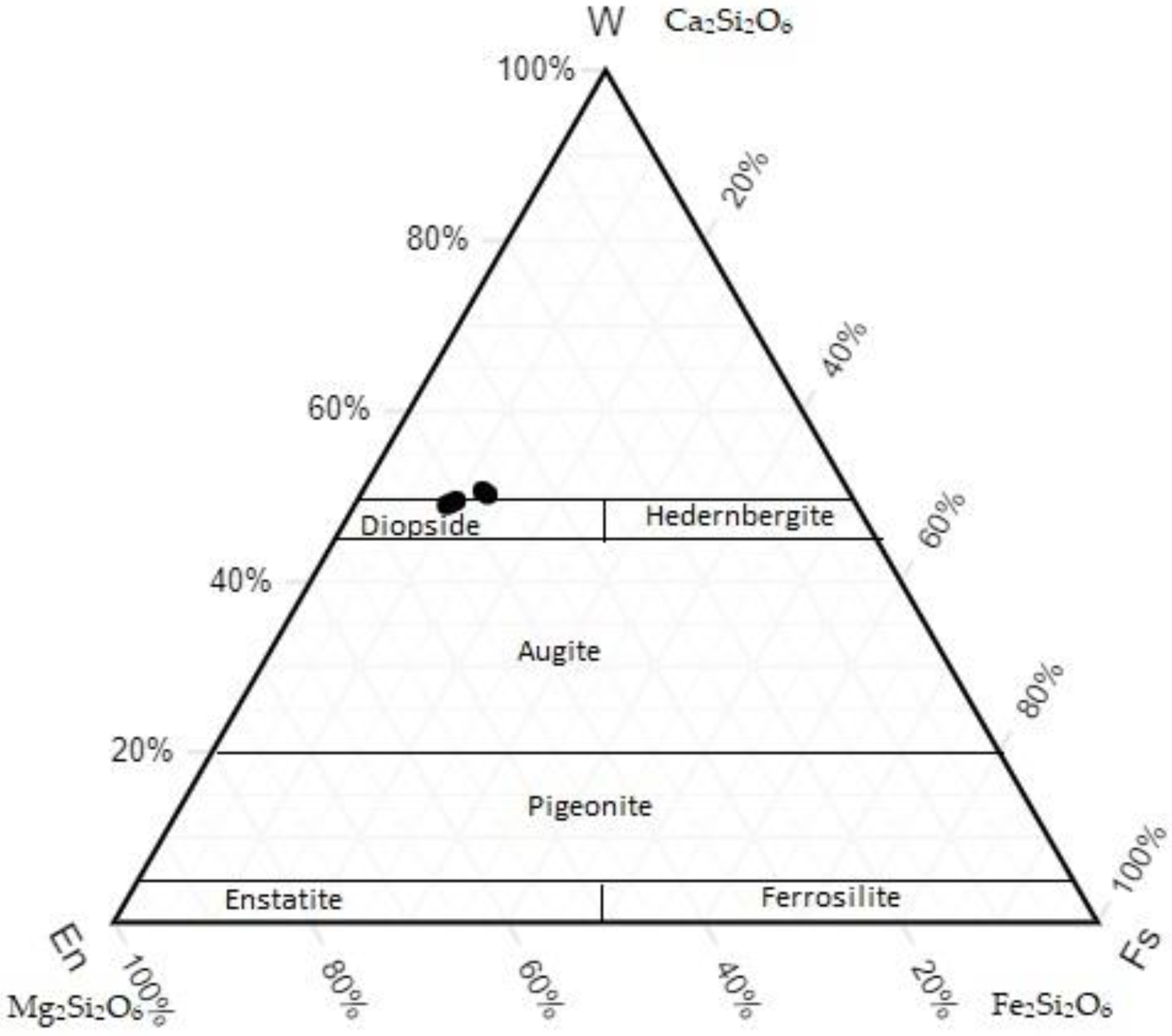

Clinopyroxene

The mafic alkalic volcanic rocks of Feni are rich in clinopyroxenes, accompanied by feldspathoids, Fe-Ti oxides and minor olivine. This is very similar to the mineral composition of other mafic alkalic volcanics in other countries such as Syria and Uganda [

29,

30] (Dobosi et al, 1991; Tyler & King, 1967). Electron microprobe analysis was conducted on a sector-zoned clinopyroxene xenocryst (

Figure 6B,

Figure 7K) in the phonotephrite sample OPN3 from Niffin (

Figure 12, 13). Mineral compositions were calculated in the PYXCALC spreadsheet from Gabbrosoft and plotted in Ternary Plot Generator - Quickly create ternary diagrams. Using the Ca-Mg-Fe quadrilateral ternary plot, the zoned pyroxene grain was classified as diopside (MgCaSi

2O

6) in

Figure 13. It shows increasing MgO and CaO composition from rim to core but decreasing values of MnO, Al

2O

3, FeO, and TiO

2. OPN8B phonotephrite sample also contains diopside phenocrysts. The diopside in the mafic phonotephrite OPN3 is more calcic than those in the mesocratic hornblende-bearing phonotephrite OPN8B.

Figure 12.

Tabulated analyses of zoned clinopyroxene in phonotephrite OPN3 and bivariate graphs of FeO vs MgO, CaO vs MgO and FeO vs TiO2 to show compositional variations from core to rim. Core is rich in CaO and MgO whilst the rims are enriched in TiO2 and FeO.

Figure 12.

Tabulated analyses of zoned clinopyroxene in phonotephrite OPN3 and bivariate graphs of FeO vs MgO, CaO vs MgO and FeO vs TiO2 to show compositional variations from core to rim. Core is rich in CaO and MgO whilst the rims are enriched in TiO2 and FeO.

Figure 13.

Ternary plot of clinopyroxene compositions from phonotephrite samples OPN3 & OPN8B. Mineral compositions calculated with PYXCALC from Gabbrosoft and plotted in Ternary Plot Generator - Quickly create ternary diagrams.

Figure 13.

Ternary plot of clinopyroxene compositions from phonotephrite samples OPN3 & OPN8B. Mineral compositions calculated with PYXCALC from Gabbrosoft and plotted in Ternary Plot Generator - Quickly create ternary diagrams.

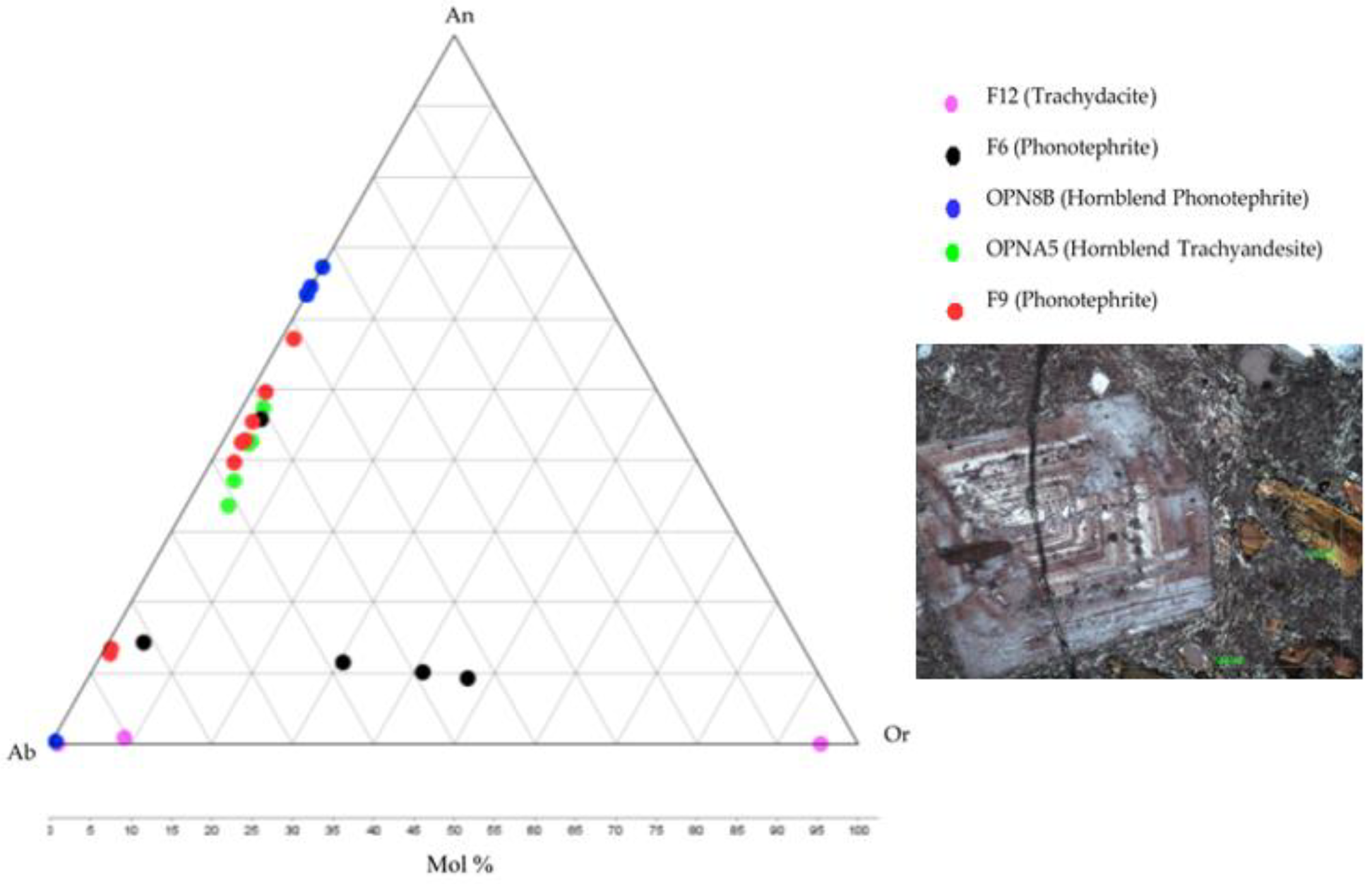

Feldspathoid and Feldspar-Plagioclase

Alkali feldspar and plagioclase are ubiquitous in both anhydrous mafic magmas and evolved hydrous magmas at varying proportions. Feldspathoids such as leucite and nepheline are distinguishable in thin section petrography but may get mixed up with alkali feldspar in mineral chemistry analyses. The olivine-clinopyroxene bearing basalt and trachybasalt mafic suites are dominated by calcic labradorite, anorthites, leucite and nepheline. Clinopyroxene-rich basalt and mafic fine-grained phonotephrite that are devoid of olivine usually contain nepheline, minor plagioclase and alkali feldspar. The intermediate hornblende-bearing phonotephrite and trachyandesite porphyries, however, contain twinned albite, andesine, and labradorite cores within concentric zoned plagioclase crystals. Feldspathoid such as nepheline and hauyne along with alkali feldspar were also observed in the hornblend-bearing intermediate trachyandesite and phonotephrite in minimal amounts. In the biotite-quartz trachydacite, albite crystals predominate with perthitic twinning and orthoclase anti-perthites observed optically and under the EMPA. All EMPA analysis of feldspar and plagioclase are attached in the supplementary notes.

Mafic phonotephrite sample F6 (

Figure 14) contains oligoclase, andesine and alkali feldspar (Or

35-53) and nepheline [

31] (Ponyalou, 2013, unpublished thesis). The plagioclase crystals in the hornblend-phonotephrite sample F9 are mainly andesine (An

30-50) with minor oligoclase (An

10-30) and labradorite (An

50-70). The mafic phenocrysts in F9 are mainly hornblend and pyroxene. The plagioclase crystals in Niffin phonotephrite sample OPN8B are mostly labradorite (An

50-70) with occasional albite (An

0-10 or Ab

99) occurring alongside hornblend and pyroxene phenocrysts. F9 and OPN8B both have high temperature labradorite crystals occurring together with lower temperature plagioclase, clinopyroxene and hornblend meaning there is a change in temperature from high to low possibly due to the influx of water or crystal fractionation.

The plagioclase phenocrysts include andesine (An

30-50) and labradorite (An

50-70) in the Natong trachyandesite (

Figure 14). An oscillatory-zoned plagioclase in OPNA5 showed cyclic compositional variations between sodium and calcium calculated at Ab

46-61 or An

37-47. Zoned plagioclase crystals have sodic rims of andesine composition and a calcic core of labradorite composition (An

52). Crystal fractionation and slow cooling is responsible for the compositional zoning in plagioclase in the Natong trachyandesite. Plagioclase phenocrysts in trachydacite porphyry sample F12 are notably sodic, mainly Ab

90-99 and occasionally show K-feldspar perthite (Or

95) exsolution lamellae, observed optically and also within the microprobe.

In summary, the more evolved subvolcanic intermediate trachyandesite and trachydacite porphyry suites contain sodic plagioclase (ie andesine and albite) whereas mafic basalt and phonotephrite contains Ca-rich plagioclase labradorite.

Figure 14.

Ternary plot of feldspar-plagioclase compositions of selected samples (F12, F6, OPN8B, OPNA5 & F9) plotted in IOGAS. Insert of zoned tabular plagioclase in OPNA5 with albitic rims and anorthitic core.

Figure 14.

Ternary plot of feldspar-plagioclase compositions of selected samples (F12, F6, OPN8B, OPNA5 & F9) plotted in IOGAS. Insert of zoned tabular plagioclase in OPNA5 with albitic rims and anorthitic core.

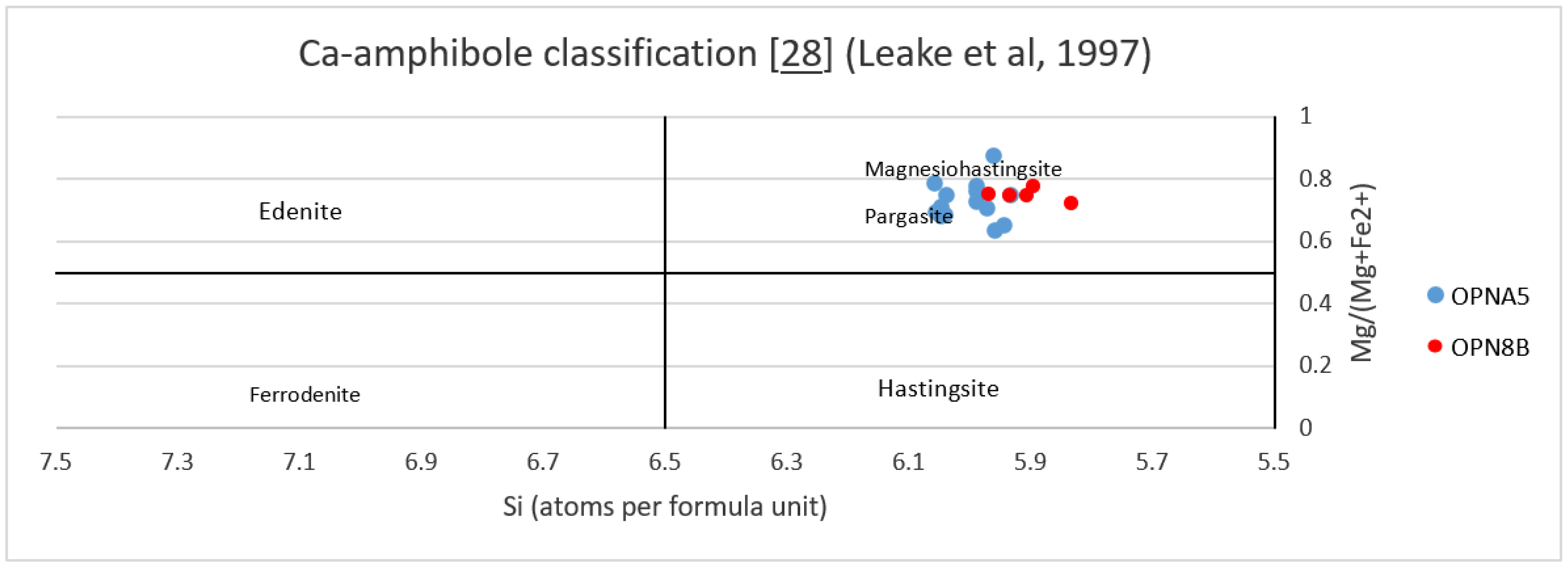

Amphibole

Mafic amphiboles (or hornblende) occur mainly as laths, tabular crystals and four-sided diamond-shaped basal sections in intermediate trachyandesite outcrops along Natong Creek and in evolved phonotephrite (sample OPN8B) in the Niffin area. Using the Amp-TB spreadsheet by [

27] Ridolfi et al (2010) and the Ca-amphibole classification after [

28] Leake et al (1997), the amphibole composition in the Natong trachyandesite (OPNA5) and the Niffin phonotephrite (OPN8B) is calculated as magnesiohastingsite (

Table 2,

Figure 15), a magnesium-rich Ca-hornblende (13-14.5 wt% MgO). Using the Amp-TB spreadsheet, melt H

2O content in trachyandesite was calculated as 4-5 ±0.7 wt % with an estimated depth of crystallization at 15-19.4 km under oceanic crust having temperature ranges of 998-1025

°C [

27] (Ridolfi et al., 2010). In contrast, the phonotephrite sample OPN8B had a melt H

2O content of 4.1- 4.9 ±0.7 wt % with an estimated depth of crystallization at 19.6-24.2 km under oceanic crust at temperature ranges of 1029-1056

°C.

The composition of hornblende crystals in OPNA5 trachyandesite was also classified as magnesiohastingsite (

Figure 15) using the Ca-amphibole classification scheme by [

28] Leake et al (1997) and the AMPH13 spreadsheet by Gabbrosoft.org for stoichiometric calculations of electron microprobe analysis (

https://www.gabbrosoft.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/AMPH13.xls). Also following the [

28] Leake et al (1997) Ca-amphibole classification scheme, the composition of amphibole laths and a megacryst in OPN8B phonotephrite sample from Niffin were identified as magnesiohastingsite with minor pargasite within the megacryst (

Figure 15). In the same sample, hornblende is observed to be replacing early pyroxene grains which are now decomposed or resorbed [

31] (Ponyalou, 2013, unpublished thesis).

Table 2.

OPNA5 zoned amphibole.

Table 2.

OPNA5 zoned amphibole.

| Sample number |

OPNA5 |

OPNA5 |

OPNA5 |

OPNA5 |

OPN8B |

OPN8B |

OPN8B |

| Point |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

7 |

8 |

8 |

| Job |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

8 |

8 |

9 |

| SiO2 |

40.78 |

40.6 |

40.18 |

40.28 |

38.697 |

40.193 |

39.923 |

| TiO2 |

2.26 |

1.84 |

1.94 |

2.12 |

2.805 |

2.654 |

2.601 |

| Al2O3 |

12.36 |

12.96 |

13.41 |

12.79 |

14.028 |

13.382 |

13.984 |

| Cr2O3 |

0 |

0 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0 |

0.02 |

0.004 |

| FeO |

12.86 |

11.49 |

12.21 |

12.25 |

11.067 |

10.556 |

11.169 |

| MnO |

0.28 |

0.12 |

0.16 |

0.22 |

0.229 |

0.197 |

0.189 |

| MgO |

13.18 |

14.48 |

13.58 |

13.45 |

13.052 |

13.831 |

13.428 |

| CaO |

12.08 |

12.27 |

12.29 |

12.18 |

12.344 |

12.088 |

12.107 |

| Na2O |

2.6 |

2.73 |

2.64 |

2.75 |

2.288 |

2.404 |

2.355 |

| K2O |

1.4 |

1.28 |

1.23 |

1.29 |

1.615 |

1.635 |

1.553 |

| Total |

97.8 |

97.77 |

97.65 |

97.34 |

96.125 |

96.971 |

97.339 |

| Mineral |

Zoned Hb |

Zoned Hb |

Zoned Hb |

Zoned Hb |

Hb spindle |

Hb megacryst |

Hb megacryst |

| Mode of occurrence |

Phenocryst |

Phenocryst |

Phenocryst |

Phenocryst |

Phenocryst |

Phenocryst |

Phenocryst |

| Species |

Magnesiohastingsite |

Magnesiohastingsite |

Magnesiohastingsite |

Magnesiohastingsite |

Pargasite |

Pargasite |

Magnesiohastingsite |

Figure 15.

Amphibole chemistry for hornblende phenocrysts in the trachyandesite suite (OPNA5) from Natong and phonotephrite suite (OPN8B) from Niffin, Ambitle. Stoichiometry calculated using AMPH13.xls (Gabbrosoft.org) and plotted in Excel using the Ca-amphibole classification after [

28] Leake et al (1997). OPNA5 amphibole are magnesiohastingsite. OPN8B amphiboles comprise of both magnesiohastingsite and pargasite.

Figure 15.

Amphibole chemistry for hornblende phenocrysts in the trachyandesite suite (OPNA5) from Natong and phonotephrite suite (OPN8B) from Niffin, Ambitle. Stoichiometry calculated using AMPH13.xls (Gabbrosoft.org) and plotted in Excel using the Ca-amphibole classification after [

28] Leake et al (1997). OPNA5 amphibole are magnesiohastingsite. OPN8B amphiboles comprise of both magnesiohastingsite and pargasite.

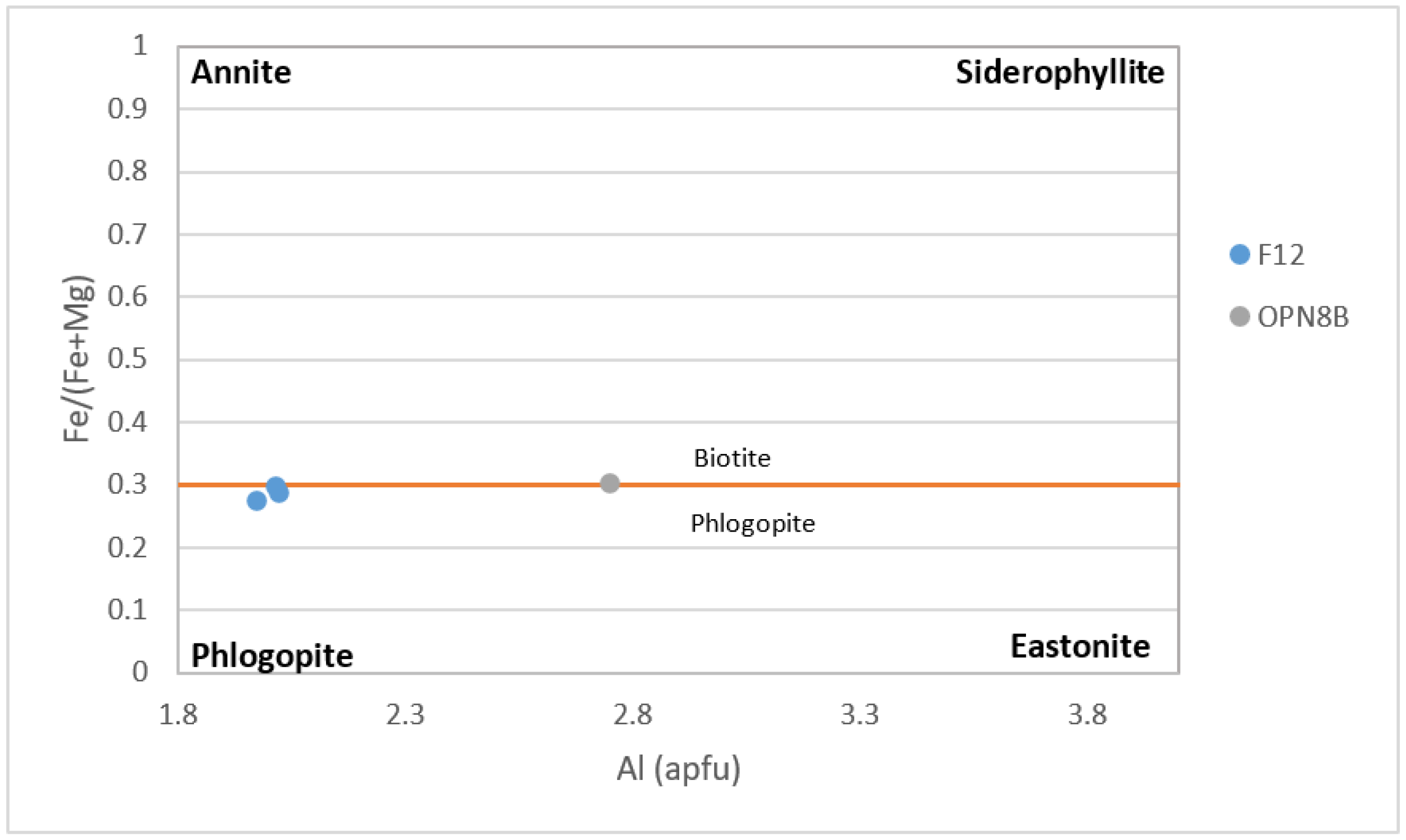

Mica

The mica group forms distinct minerals and are not part of a solid solution series as other minerals are such as feldspars, olivine, clinopyroxene, and actinolite-tremolite. Distinct mica minerals include muscovite, siderophyllite, eastonite, phengite, phlogopite, and biotite [

32] (Deer et al, 2005). Biotite is a common mineral phase in intermediate and felsic igneous rocks. Biotite inclusions were observed in a hornblend megacryst in OPN8B (phonotephrite) from the Niffin area. Tabular biotite microphenocrysts also occur in the groundmass of the trachydacite porphyry (F12) and are relatively Mg-rich. When plotted in the annite-siderophyllite-phlogopite-eastonite (ASPE) quadrilateral diagram by [

33] Speer (1984), the mica in F12 classified as phlogopite. The mica in OPN8B phonotephrite contained more Fe and thus plotted above the 0.3 line signifying it to be igneous biotite.

Table 3.

Analysis of mica in phonotephrite and trachydacite.

Table 3.

Analysis of mica in phonotephrite and trachydacite.

| Sample |

OPN8B |

F12 |

F12 |

F12 |

| Point |

10 |

1 |

5 |

7 |

| Job |

8 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| SiO2 |

35.26 |

38.57 |

38.44 |

40.65 |

| TiO2 |

3.53 |

2.89 |

2.07 |

2.38 |

| Al2O3 |

17.47 |

11.41 |

11.26 |

11.46 |

| Cr2O3 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

| FeO |

12.35 |

12.86 |

13.49 |

12.72 |

| MnO |

0.19 |

0.15 |

0.18 |

0.21 |

| MgO |

16.08 |

18.03 |

18.02 |

18.98 |

| CaO |

0.06 |

0.00 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

| Na2O |

1.47 |

0.82 |

1.14 |

0.71 |

| K2O |

7.98 |

9.48 |

8.67 |

8.67 |

| NiO |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Total |

94.49 |

94.25 |

93.34 |

95.86 |

| Al (apfu) |

2.749838089 |

2.022636188 |

2.015425253 |

1.974545278 |

| Fe/(Fe+Mg) |

0.3010823 |

0.285744138 |

0.295720045 |

0.273201555 |

| Mineral |

Biotite |

Phlog |

Phlog |

Phlog |

| Mode of occurrence |

Inclusion in hornblende phenocryst |

microphenocryst |

microphenocryst |

microphenocryst |

Figure 16.

Biotite chemistry classified in the annite–siderophyllite–phlogopite–eastonite (ASPE) quadrilateral (Speer, 1984). F12 micas are magnesium-rich and therefore, may be classed as phlogopite. Biotite in OPN8B is more iron-rich.

Figure 16.

Biotite chemistry classified in the annite–siderophyllite–phlogopite–eastonite (ASPE) quadrilateral (Speer, 1984). F12 micas are magnesium-rich and therefore, may be classed as phlogopite. Biotite in OPN8B is more iron-rich.

Minor and Accessory minerals- Ti magnetite, Magnetite and Apatite

Minor and accessory minerals include magnetite or titanomagnetite and apatite.

Table 4 shows these minerals observed in phonotephrite sample OPN3, trachydacite porhyry F12 and trachyandesite OPNA5. Apatite occurs in mafic, intermediate and felsic rocks. EMPA of F12 (trachydacite porphyry) shows euhedral, trapezium-shaped apatite grains containing 52-53 wt % CaO (

Figure 9 I). Magnetite generally contains 4-5.8 % wt TiO

2 and ̴ 68% wt FeO occuring in mafic to intermediate lavas. Impurities in magnetite as per the EMP results in

Table 4 include Mg and Al.

Figure 9 A, D and E are photomicrographs of apatite in OPNA5 closely associated with the amphibole mineral clusters. The apatite and magnetite are interpreted to be igneous in origin [

34] (Loader, 2017). The apatites in the trachyandesite OPNA5 are slightly more calcic than trachydacite F12 and phonotephrite OPN3.

Table 4.

Analysis for accessory minerals. Titanium-bearing magnetite and apatite in phonotephrite OPN3. Apatite in F12 and OPNA5.

Table 4.

Analysis for accessory minerals. Titanium-bearing magnetite and apatite in phonotephrite OPN3. Apatite in F12 and OPNA5.

| Sample |

OPN3 |

OPN3 |

OPN3 |

F12 |

F12 |

OPNA5 |

OPNA5 |

| Litho |

Phon |

Phon |

Phon |

TD |

TD |

TA |

TA |

| Point |

28 |

29 |

30 |

8 |

9 |

24 |

25 |

| Job |

8 |

8 |

8 |

3 |

3 |

7 |

7 |

| SiO2 |

0.1 |

0.13 |

2.69 |

0 |

0 |

0.50 |

0.31 |

| TiO2 |

5.79 |

5.69 |

0.04 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Al2O3 |

7.83 |

7.32 |

0.37 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Cr2O3 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.01 |

0 |

| FeO |

68.44 |

68.04 |

0.85 |

0.12 |

0.1 |

0.40 |

0.16 |

| MnO |

0.81 |

1.07 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

| MgO |

4.23 |

2.97 |

0.95 |

0.05 |

0.04 |

0.14 |

0.09 |

| CaO |

0.07 |

1.94 |

50.07 |

52.67 |

52.92 |

54.23 |

54.45 |

| Na2O |

0 |

0.06 |

0.02 |

0.26 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

| K2O |

0.01 |

0 |

0.04 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.01 |

| Total |

87.31 |

87.31 |

55.12 |

53.22 |

53.29 |

55.50 |

55.13 |

| Mineral |

Magnetite |

Magnetite |

Apatite |

Apatite |

Apatite |

Apatite |

Apatite |

4.3. Whole-rock Geochemistry

The whole rock geochemical analysis is split into major (

Table 5) and trace elements (

Table 6). These are a representative summary of the geochemical data which is fully presented in the

supplementary material.

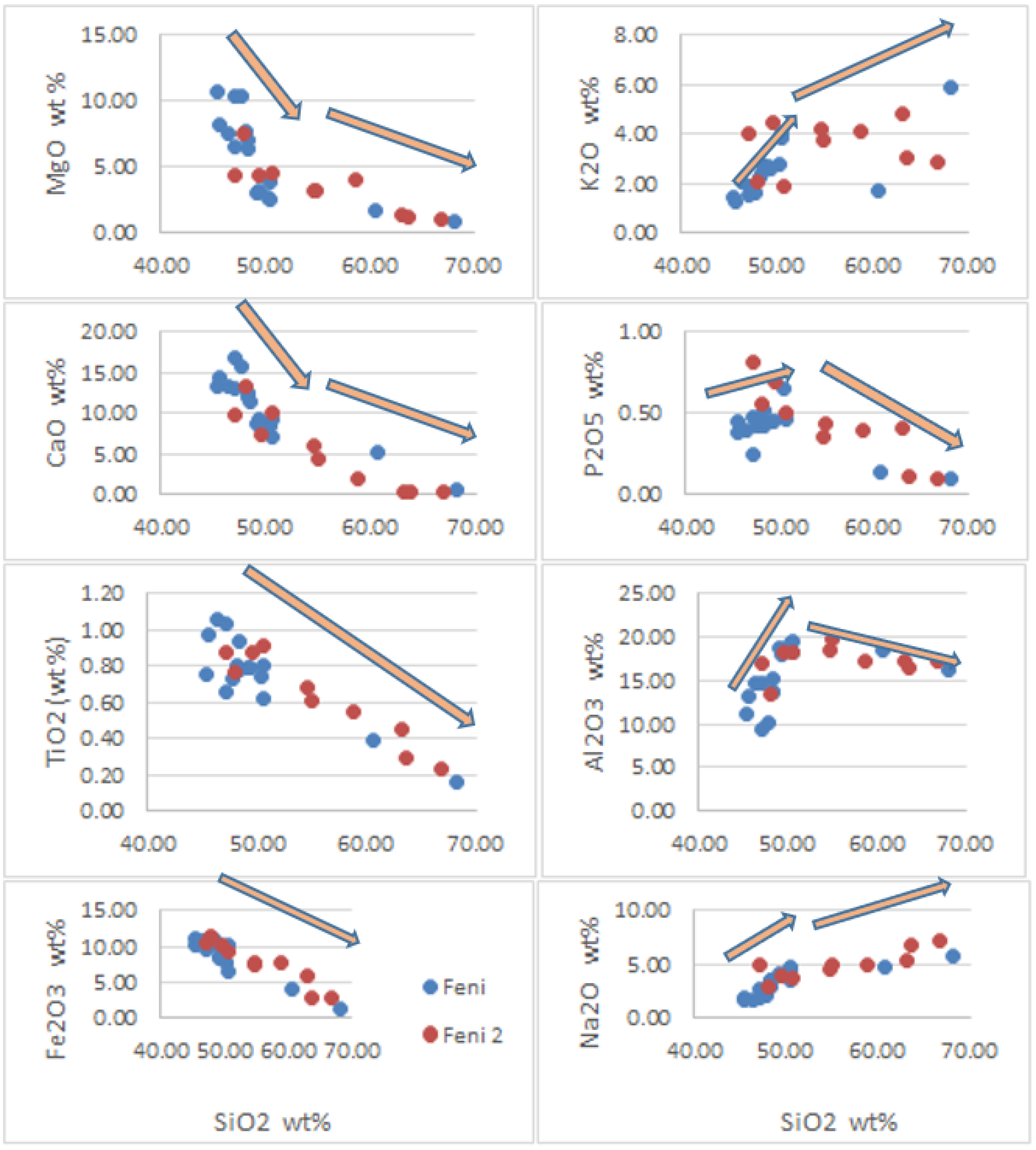

Major Elements

Major elements are presented in bivariate Harker diagrams with SiO

2 on the x-axis to show the main geochemical trends for the Feni magmas (

Figure 17). The three main patterns observed in these plots relative to increasing silica include (1) a decreasing or compatible trend for TiO

2, Fe

2O

3, MgO, and CaO, (2) increasing or incompatible trend for Na

2O and K

2O, and (3) scattering or a mixture of incompatible and compatible behaviour due to minor hydrothermal alteration and the appearance of favorable mineral phases later on as the melt becomes more felsic (eg K

2O, Al2O3).

An inflection point exists in most major element variation diagrams at SiO2 content of ~52%. There is also a ~1% SiO2 gap in the data at the point of inflection. This probably means that the rock types that form around the 52% mark (such as basaltic trachyandesite, tephriphonolite, and phonolite) were either not sampled or are absent in the Feni magma series.

The trends observed in the bivariate major elemental oxide plots are indicative of a change in fractionation of the mineral assemblages. At SiO2 contents of 45% (ie basalt) to 52% (ie trachybasalt and phonotephrite composition), the declining MgO, CaO, Fe2O3, and TiO2 compositions indicate olivine, pyroxene, magnetite, anorthitic plagioclase +/- amphibole crystal fractionation. In contrast, Al2O3, Na2O, K2O and P2O5 behave incompatibly with silica in the mafic rocks < 52%. From ~53% to 70% SiO2, MgO and CaO decline gradually relative to the basic or low SiO2 rocks. K2O and Na2O behave incompatibly relative to silica with the former displaying more scatter possibly as a result of weathering and alteration. These geochemical patterns are consistent with a change in the crystal fractionation of the controlling mineral assemblage:

olivine, pyroxene, and amphibole fractionation removes MgO and Fe2O3 from the melt.

pyroxene, amphibole, anorthite, and apatite fractionation removes CaO from the melt.

titanite, magnetite, clinopyroxene, amphibole, and biotite fractionation removes TiO

2 and Fe

2O

3 from the melt (

Figure 12,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4)

apatite is the main phosphate mineral that will use up P2O5 from the melt. It mainly occurs as a minor or accessory mineral in the mafic and felsic magmas of Feni. It is also strongly abundant in the mafic glomerocryst or cumulate phases of the Natong trachyandesite occuring alongside hornblend and magnetite. This explains the divergence or scatter in the Harker plot as a result of its abundance and mode of occurrence in the various rock types.

Al2O3 exhibits a steep increase from 45-50 wt% but then stabilizes and shows a slow decrease with increasing SiO2. It behaves incompatibly first in the primitive mafic melt but then behaves compatibly for rock types greater than 52% silica. This is because in the basaltic melt, there is little or no mineral phase that will take up Al2O3 but as the melt progressively becomes intermediate and felsic in composition, minerals like amphibole, mica, feldspar, and feldspathoid will use up the Al2O3.

K2O and Na2O positively correlate with silica but show some scatter in the more felsic rocks. This is because during normal crystal fractionation, there is little or no mineral phase to remove K2O and Na2O from the primitive basaltic melt except for minor alkali feldspar and feldspathoid (if present). As the melt fractionates and becomes more felsic, the minerals that take up K2O and Na2O include feldspar, plagioclase, feldspathoid and biotite in the more intermediate and felsic igneous rocks. The scatter in the more felsic compositions most likely results from either weathering or mild hydrothermal alteration.

Table 5.

Representative major element analysis of Feni volcanic rocks.

Table 5.

Representative major element analysis of Feni volcanic rocks.

| ID |

Rock1

|

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

CaO |

Fe2O3 |

MgO |

Na2O |

K2O |

TiO2 |

MnO |

P2O5 |

Cr2O3 or SO3 |

LOI |

Total |

| F4 |

Ba |

46.7 |

9.3 |

16.6 |

9.6 |

10.3 |

1.9 |

1.5 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.9 |

97.9 |

| F5 |

TBa |

48.3 |

15.3 |

11.5 |

10.6 |

6.4 |

3.5 |

2.4 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

100.0 |

| F6 |

PhoT |

49.1 |

17.8 |

9.0 |

9.8 |

3.8 |

4.7 |

3.7 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

3.0 |

102.6 |

| F7 |

Ba |

44.8 |

14.2 |

12.8 |

10.4 |

7.3 |

1.7 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

3.5 |

98.4 |

| F9 |

PhoT |

49.0 |

18.8 |

6.9 |

6.4 |

2.5 |

4.4 |

3.9 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

3.1 |

96.1 |

| F11 |

Ol-Ba |

47.2 |

10.0 |

15.5 |

10.6 |

10.2 |

2.1 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

1.3 |

99.9 |

| F12 |

TD |

67.0 |

16.0 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

5.6 |

5.8 |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

1.8 |

99.3 |

| F16 |

Ba |

45.5 |

14.3 |

12.5 |

10.5 |

6.3 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

1.0 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

3.4 |

98.5 |

| F19 |

Ol-Ba |

44.8 |

13.0 |

14.1 |

9.9 |

8.0 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

1.6 |

95.9 |

| F23 |

TBa |

49.1 |

18.9 |

8.2 |

7.7 |

2.7 |

3.4 |

2.7 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

<0.001 |

2.5 |

96.4 |

| OP-N3 |

PhoT |

46.3 |

16.8 |

9.7 |

10.3 |

4.3 |

4.8 |

3.9 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

1.7 |

99.8 |

| OP-N4C |

TD |

65.4 |

16.7 |

0.3 |

2.8 |

1.1 |

7.0 |

2.8 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

2.2 |

99.4 |

| OP-N5 |

TA |

57.7 |

16.9 |

2.0 |

7.7 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

4.0 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.0 |

1.8 |

100.2 |

| OP-N8A |

Ol-Ba |

46.7 |

13.2 |

13.0 |

11.1 |

7.4 |

2.8 |

2.0 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

2.8 |

100.5 |

| OP-N8B |

PhoT |

48.1 |

17.7 |

7.2 |

10.0 |

4.3 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.7 |

0.1 |

3.0 |

100.1 |

| OP-NA1 |

TA |

54.1 |

18.3 |

5.9 |

7.6 |

3.2 |

4.5 |

4.2 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

1.0 |

100.1 |

| OP-NA5 |

TA |

54.4 |

19.5 |

4.5 |

7.4 |

3.2 |

4.9 |

3.7 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

1.1 |

99.9 |

| OP-BA1 |

TBa |

49.7 |

18.0 |

9.9 |

9.0 |

4.5 |

3.6 |

1.8 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

2.0 |

100.1 |

Figure 17.

Major element variation plots for representative volcanic rocks from Feni Island. Blue dots are rocks collected in the first trip around Babase and Ambitle. Red dots are samples collected in the second trip to Ambitle.

Figure 17.

Major element variation plots for representative volcanic rocks from Feni Island. Blue dots are rocks collected in the first trip around Babase and Ambitle. Red dots are samples collected in the second trip to Ambitle.

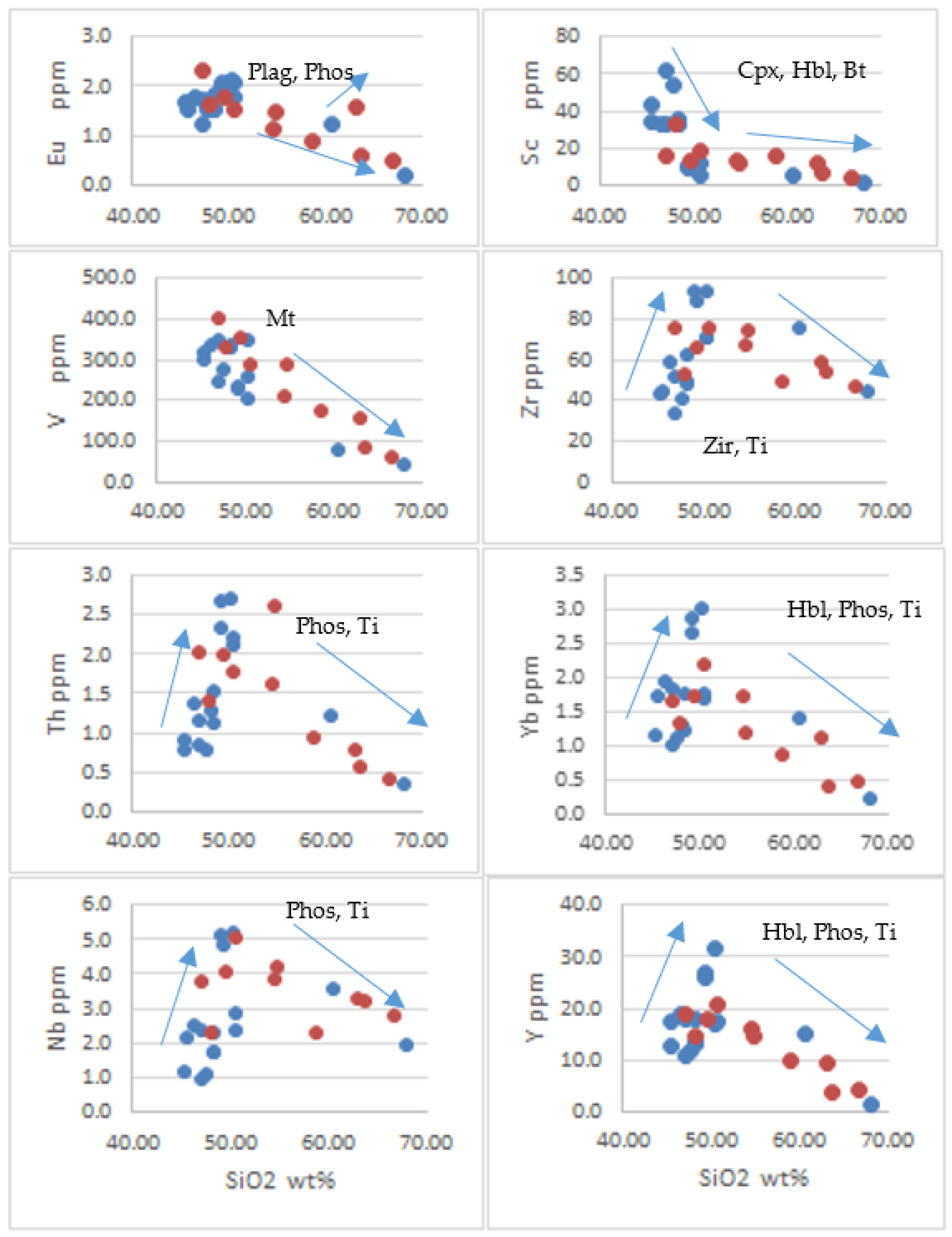

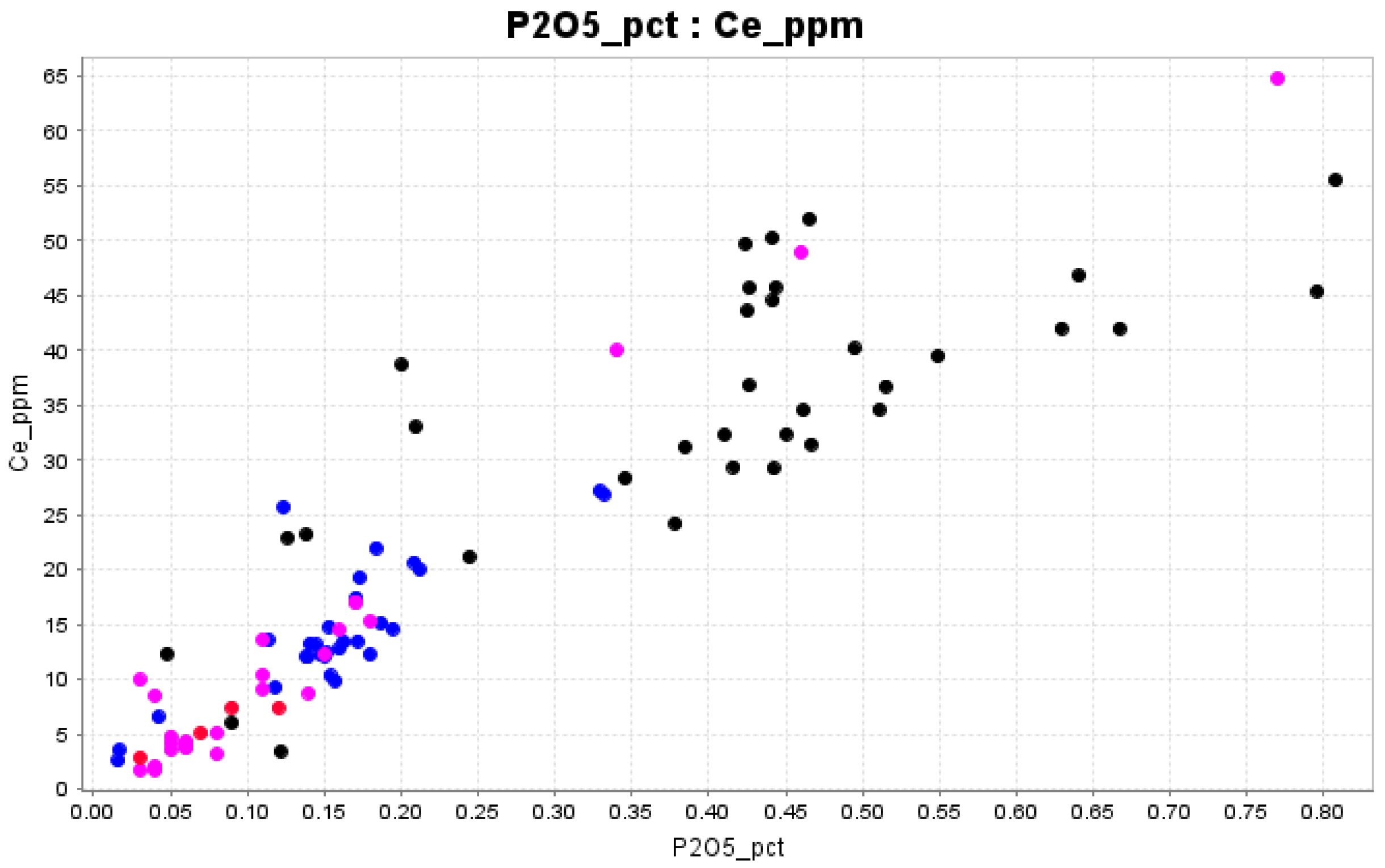

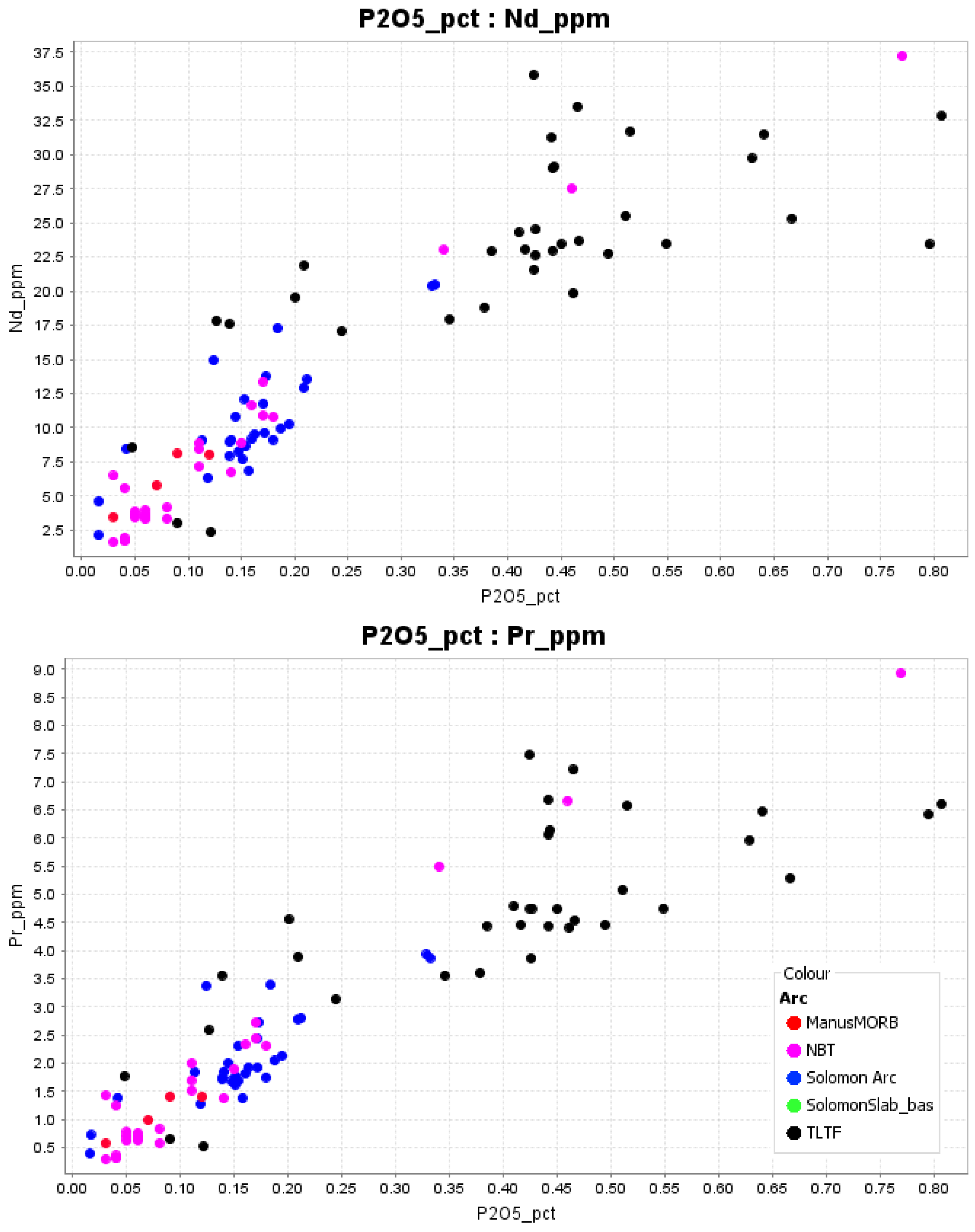

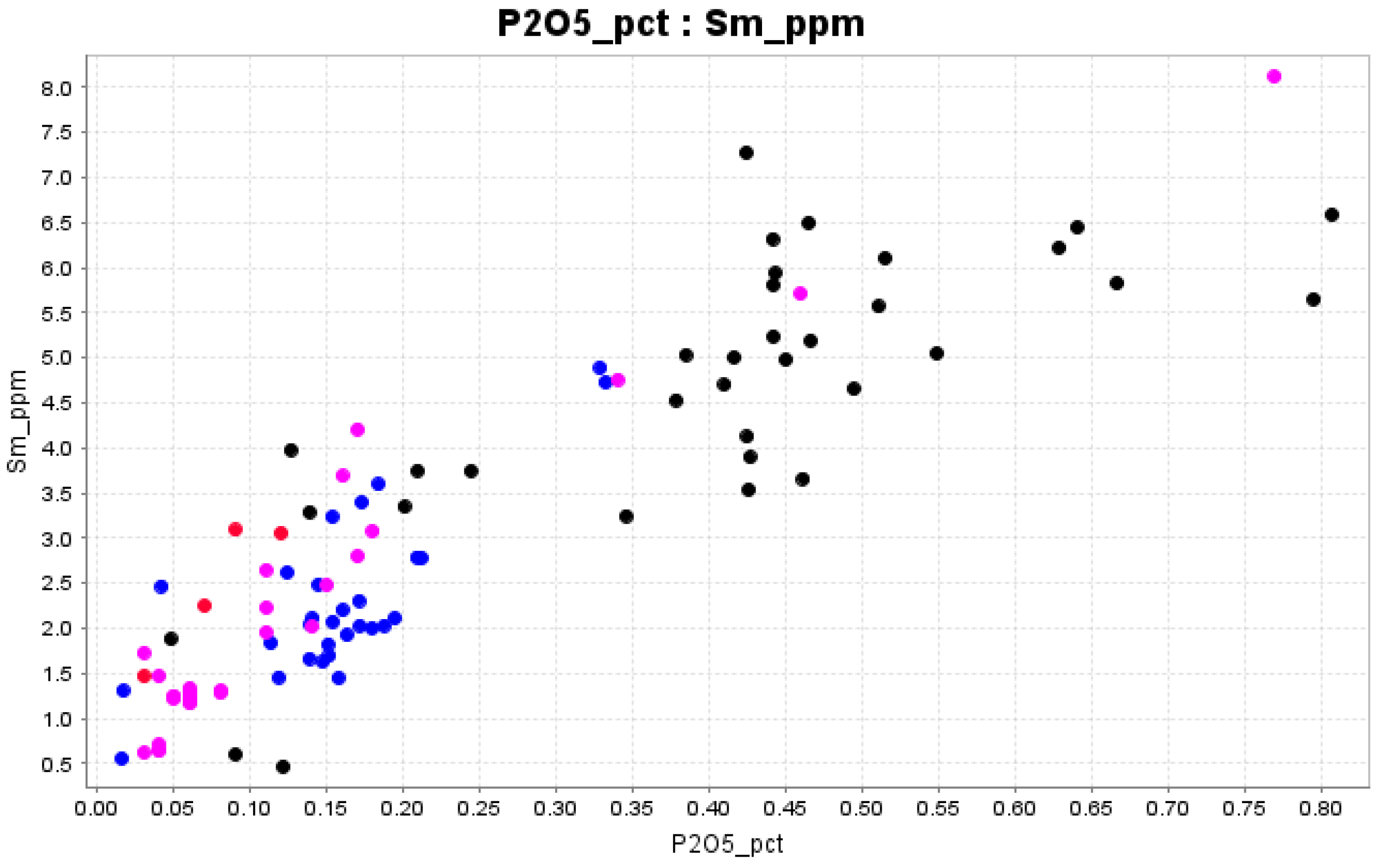

Trace Elements

Trace elements are generally described according to their compatibility or ability to partition into a solid mineral phase or remain in the melt. Compatible trace elements are able to substitute for major elements in higher temperature mineral phases whereas incompatible elements remain in the melt.

Trace element trends for the Feni magmas (

Table 6, Fig 21) are sympathetic to the major element trends with pronounced inflection points on many graphs. Relative to SiO

2, the main trace element geochemical trends in the Feni magmas include (a) decreasing linear trend indicating compatibility and (b) a mixture of both compatible and incompatible behaviour. Trace elements Sc, V and Eu behave compatibly and decrease as SiO

2 increases (

Figure 21). In contrast, the trace elements Zr, Th, Yb, Nb, and Y behave incompatibly in the mafic rocks from 45-52 wt% SiO

2 but steadily decrease in the intermediate (ie trachyandesite) to felsic (ie trachydacite) rocks (52-69 wt% SiO

2) as the magma cools. These trends are indicative of the crystal fractionation of specific mineral phases and are further elaborated below.

Sc (~0 – 60 ppm) behaves compatibly throughout the evolution of the Feni magmas because the metal substitutes for Fe in most ferromagnesian minerals, including olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite [

35] (Halley, 2020). Thus, the decreasing linear trend of Sc vs SiO

2 is, therefore, an indication of the fractionation of these Fe-Mg silicate minerals. V is the most abundant of the trace elements in the Feni magmas assaying up to 400 ppm and also behaves similarly to Sc where it substitutes for Fe in pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. However, V is most strongly associated with magnetite fractionation in oxidized magmas [

35] (Halley, 2020). Thus, magnetite fraction is possibly the main controlling phase for V in the Feni magmas followed by pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite. Also note that Sc and V geochemical behaviour relative to silica are similar to TiO2 indicating fractionation of the same minerals whereby all elements decrease with increasing silica.

The concentration for Eu, however, is quite low ranging from 0 to 2 ppm. Its generally compatible trend is attributed to plagioclase and apatite fractionation which occurs throughout the Feni magma suite from the mafic to intermediate to felsic composition.

Zr (30-90 ppm), Y (0-32 ppm), Yb (0-3.5 ppm), Nb (1-5 ppm), and Th (0.4- 2.7 ppm) are initially incompatible and remain in the melt [

37] (Pearce & Norry, 1979) where their concentration increases with increasing silica content from 42 to 52 %. At the inflection point of 52%, all five elements decrease sharply towards 70 % silica. These elements are now compatible meaning at certain temperature and composition, certain minerals will start to crystallize incorporating these trace elements into their structure. Zr fractionation occurs when the mineral zircon starts to crystallize in felsic to intermediate rocks around temperatures greater than 750°C [

38] (Watson & Harrison, 1983) and is particularly enhanced in the presence of hydrous, oxidized and F-rich magmas [

35] (Halley, 2020). Thus, the inflection point of 52% is interpreted as the composition where the magma became hydrous and hornblend crystallization began. Y and Yb are usually taken up by hornblend fractionation. In addition, [

39] Chelle-Michou (2013) also discovered that titanite fractionation causes Nb, Th, U, Zr, Y, Yb and all REEs to behave compatibly. Due to the presence of apatite in all the Feni magmas, and is particularly most abundant in the intermediate magmas, it can be postulated that this phosphate mineral may also be responsible for incorporating REEs, U, and Th into its structure.

Table 6.

Representative trace element, particularly rare earth element (REE), analysis of Feni volcanic rocks.

Table 6.

Representative trace element, particularly rare earth element (REE), analysis of Feni volcanic rocks.

| ID |

La |

Ce |

Pr |

Nd |

Sm |

Eu |

Gd |

Tb |

Dy |

Ho |

Er |

Tm |

Yb |

Lu |

W |

Th |

U |

| F4 |

9.34 |

21.2 |

3.136 |

17.046 |

3.747 |

1.258 |

3.57 |

0.46 |

2.508 |

0.446 |

1.16 |

0.164 |

1.01 |

0.16 |

<0.5 |

0.83 |

0.64 |

| F5 |

15.2 |

34.6 |

5.084 |

25.516 |

5.57 |

1.834 |

5.3 |

0.697 |

3.905 |

0.739 |

1.98 |

0.282 |

1.75 |

0.28 |

<0.5 |

1.11 |

0.82 |

| F6 |

22.4 |

46.8 |

6.474 |

31.516 |

6.445 |

2.057 |

6.03 |

0.767 |

4.026 |

0.722 |

1.96 |

0.31 |

1.75 |

0.26 |

2.08 |

2.11 |

1.5 |

| F7 |

14.4 |

31.2 |

4.444 |

22.916 |

5.034 |

1.769 |

5.02 |

0.706 |

4.165 |

0.791 |

2.11 |

0.337 |

1.93 |

0.32 |

<0.5 |

1.35 |

0.85 |

| F9 |

22.3 |

44.5 |

6.071 |

29.016 |

5.811 |

1.797 |

4.93 |

0.697 |

3.506 |

0.636 |

1.87 |

0.282 |

1.67 |

0.28 |

<0.5 |

2.21 |

1.77 |

| F11 |

12.9 |

29.4 |

4.462 |

23.086 |

5.007 |

1.537 |

4.63 |

0.566 |

2.872 |

0.541 |

1.41 |

0.21 |

1.1 |

0.16 |

0.68 |

0.78 |

0.65 |

| F12 |

3.69 |

6.02 |

0.649 |

3.046 |

0.602 |

0.228 |

0.62 |

<0.1 |

0.538 |

<0.1 |

0.23 |

<0.1 |

0.21 |

<0.1 |

7.26 |

0.33 |

1.14 |

| F14 |

13.4 |

23.2 |

3.566 |

17.586 |

3.291 |

1.221 |

3.86 |

0.513 |

2.985 |

0.576 |

1.62 |

0.228 |

1.38 |

0.23 |

<0.5 |

1.2 |

1.03 |

| F16 |

14.5 |

31.5 |

4.544 |

23.676 |

5.194 |

1.732 |

5.26 |

0.697 |

3.861 |

0.739 |

2.04 |

0.301 |

1.82 |

0.26 |

<0.5 |

1.15 |

0.96 |

| F19 |

10.8 |

24.2 |

3.603 |

18.836 |

4.533 |

1.528 |

4.24 |

0.592 |

3.636 |

0.705 |

1.99 |

0.291 |

1.71 |

0.26 |

<0.5 |

0.88 |

0.68 |

| F23 |

28 |

52 |

7.214 |

33.526 |

6.499 |

2.149 |

6.21 |

0.916 |

5.31 |

1.084 |

3.18 |

0.492 |

3.02 |

0.51 |

<0.5 |

2.68 |

1.9 |

| OP-N3 |

22.3 |

52.4 |

6.613 |

28.871 |

6.59 |

2.307 |

6.18 |

0.778 |

3.98 |

0.767 |

2.15 |

0.237 |

1.66 |

0.26 |

0.84 |

2 |

1.54 |

| OP-N4C |

3.38 |

10.9 |

0.857 |

4.463 |

1.152 |

0.523 |

1.03 |

0.194 |

0.854 |

0.168 |

0.44 |

<0.1 |

0.47 |

<0.1 |

1.52 |

0.39 |

0.88 |

| OP-N5 |

9.59 |

20.5 |

2.762 |

10.893 |

2.754 |

0.871 |

2.37 |

0.364 |

1.959 |

0.336 |

0.97 |

0.156 |

0.86 |

0.16 |

<0.5 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

| OP-N8A |

15 |

34.2 |

4.756 |

20.324 |

5.049 |

1.627 |

4.42 |

0.607 |

2.946 |

0.528 |

1.46 |

0.221 |

1.32 |

0.18 |

1.2 |

1.39 |

1.1 |

| OP-N8B |

19.4 |

42.2 |

5.292 |

22.86 |

5.828 |

1.817 |

4.79 |

0.616 |

3.369 |

0.671 |

1.87 |

0.246 |

1.71 |

0.22 |

17.2 |

1.99 |

1.4 |

| OP-NA1 |

13.7 |

29.5 |

3.563 |

14.953 |

3.249 |

1.12 |

3.32 |

0.47 |

2.405 |

0.551 |

1.23 |

0.213 |

1.72 |

0.25 |

<0.5 |

1.59 |

1.34 |

| OP-NA5 |

20.7 |

41.7 |

4.748 |

19.392 |

4.127 |

1.469 |

3.6 |

0.543 |

2.781 |

0.504 |

1.52 |

0.205 |

1.16 |

0.22 |

1.04 |

2.61 |

1.91 |

| OP-BA1 |

16.2 |

35.6 |

4.46 |

18.302 |

4.653 |

1.494 |

4.84 |

0.624 |

3.878 |

0.791 |

2.16 |

0.311 |

2.16 |

0.32 |

<0.5 |

1.76 |

1.65 |

Figure 18.

Trace element vs silica bivariate plots for representative volcanic rocks from Feni Island. Blue dots are rocks collected in first trip around Babase and Ambitle. Red dots are samples collected in second trip to Ambitle. The mineral fractionation likely responsbile for a particular trend is labelled next to the plot: Plag=plagioclase, Phos= phosphate, Mt= magnetite, Cpx = clinopyroxene, Hbl = hornblend, Bt = biotite, Ti = titanite.

Figure 18.

Trace element vs silica bivariate plots for representative volcanic rocks from Feni Island. Blue dots are rocks collected in first trip around Babase and Ambitle. Red dots are samples collected in second trip to Ambitle. The mineral fractionation likely responsbile for a particular trend is labelled next to the plot: Plag=plagioclase, Phos= phosphate, Mt= magnetite, Cpx = clinopyroxene, Hbl = hornblend, Bt = biotite, Ti = titanite.

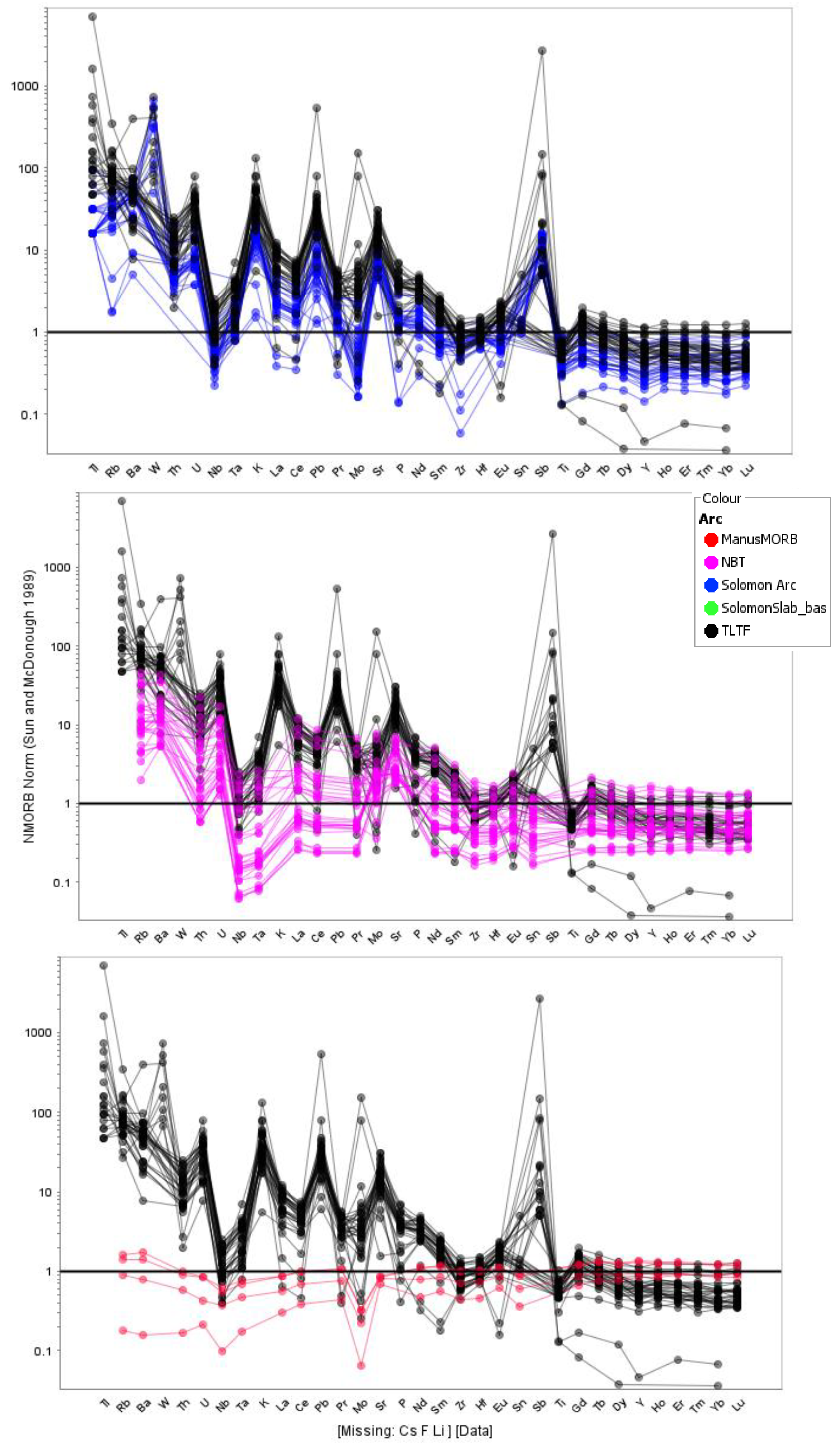

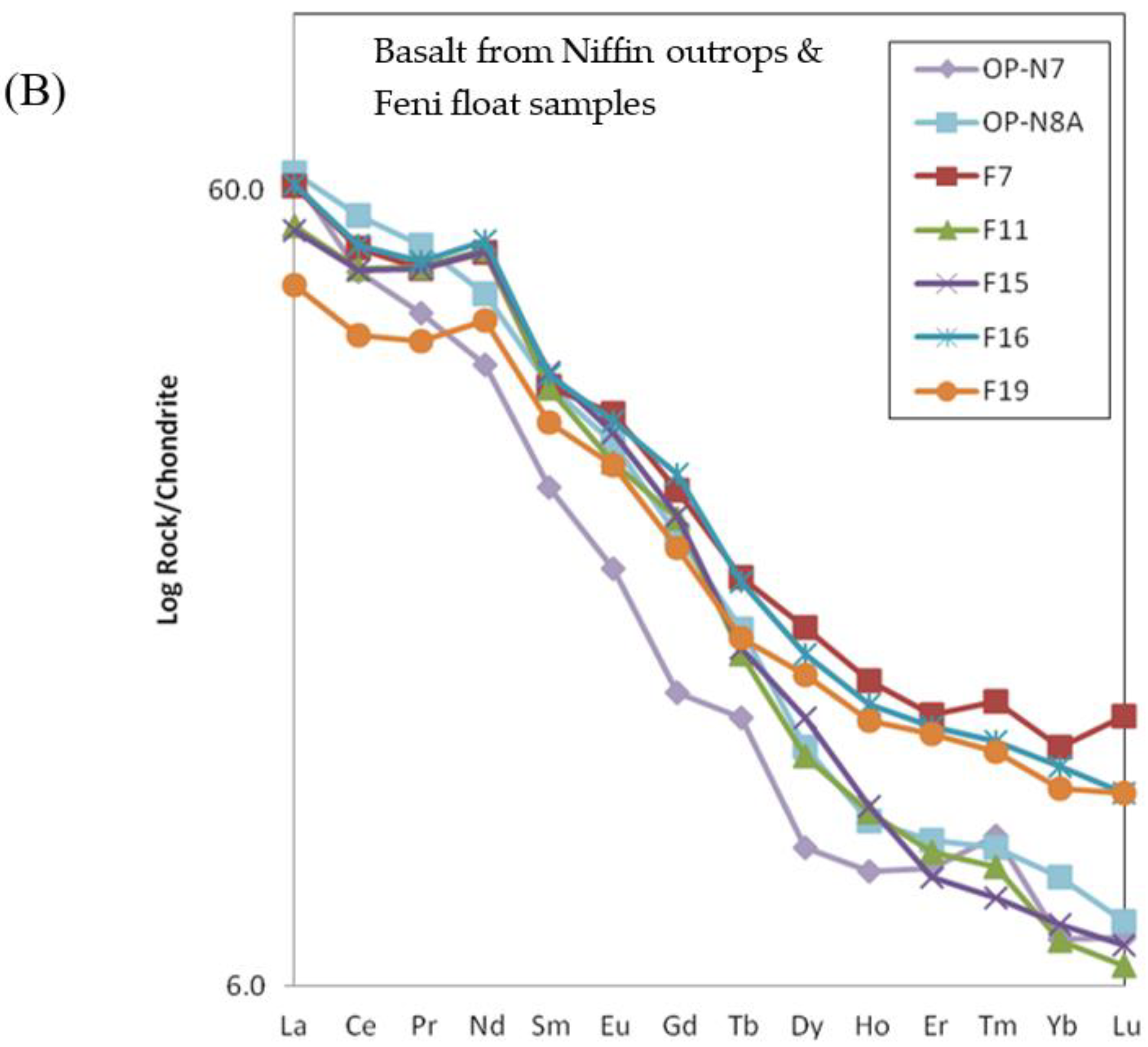

Normalized Multi-Element (Spidergram) Trace Element Patterns

Trace element concentrations are widely variable between various tectonic settings and make them better geochemical discriminants than major elements.

Table 6 represents a summary of the trace element analysis of the Feni volcanics, focusing on REE. These are plotted in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 in comparison to neighboring arcs within the Melanesian Arc such as the Gallego Volcanic Arc in the Solomon Islands, New Britain arc and Manus MORB. The trace element values of all the volcanic rocks from Feni (black), Gallego (blue), New Britain (pink) and Manus MORB (red) were normalized to NMORB [

40] (Sun & McDonough, 1989) for the spidergrams in

Figure 19. The analysed rocks of Ambitle generally have low Nb, Ti, Y and Th but are enriched in Sr, Ba, Pb, Rb, K and U. Relative to Gallego in the Solomon Arc and the New Britain (NB) Quaternary arc, trace elements within the Feni rocks are more enriched at twice the magnitude. Gallego (and NB arc) trace element patterns seem to mirror the Feni rocks indicative of arc signatures possibly relating to the older KT arc and the current New Britain-San Cristobal trench. In comparison to the Feni magmas, Manus MORB (Woodhead et al., 1998) [

24] is highly depleted in most trace elements further signifying that Feni magmas are not generated in a MORB setting.

Figure 19.

Spidergrams of trace element values normalized to NMORB and C1 chondrite [

40] (Sun & McDonough, 1989). Black lines represent Feni igneous rocks, blue lines represent Gallego igneous rocks, Solomon Arc (Petterson et al., 2011) [

23]. New Britain Trench Quaternary volcanoes (pink lines) and Manus MORB (red lines) were taken from [

24] Woodhead et al (1998). Plots generated in IOGAS.

Figure 19.

Spidergrams of trace element values normalized to NMORB and C1 chondrite [

40] (Sun & McDonough, 1989). Black lines represent Feni igneous rocks, blue lines represent Gallego igneous rocks, Solomon Arc (Petterson et al., 2011) [

23]. New Britain Trench Quaternary volcanoes (pink lines) and Manus MORB (red lines) were taken from [

24] Woodhead et al (1998). Plots generated in IOGAS.

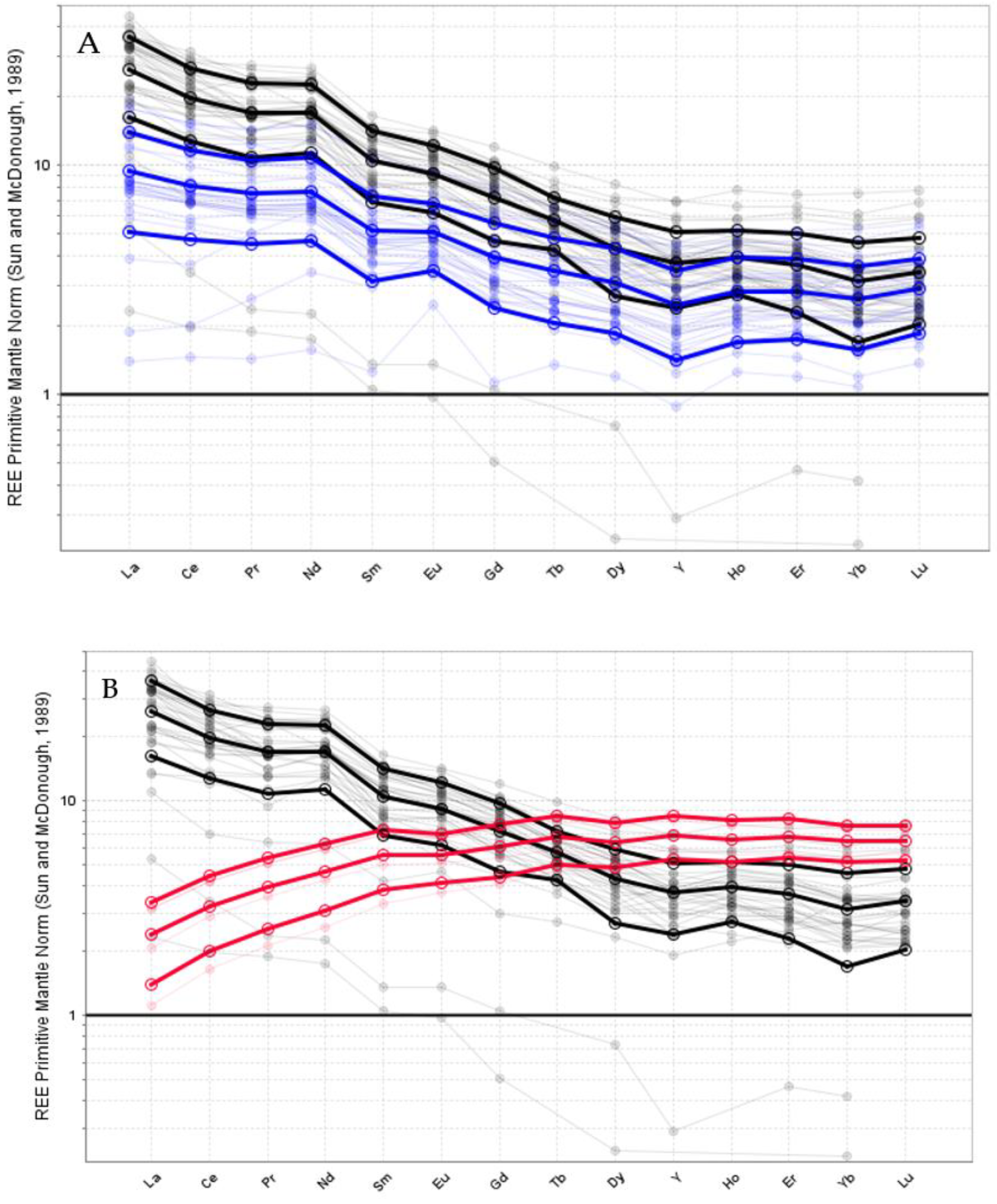

Rare Earth Elements of Feni vs other arcs

Rare earth element (REE) spider plots were constructed for Feni, Gallego (Solomon arc) and the Manus MORB [

24] (Woodhead et al., 1998) to understand REE patterns within various tectonic settings (

Figure 20). Gallego (Guadalcanal) represent calc-alkaline rocks within the Solomon Arc to the east of the active San Cristobal Trench. MORB from the Manus spreading centre are tholeiitic. Relative to the Solomon arc, the alkalic or shoshonitic lavas of Feni are more enriched in REEs. However, both magmas show similar trend of enrichment in LREE, steady decrease in MREE and no change in the HREE forming a spoon-shape profile typical of hornblende fractionation. In contrast, the Manus MORB is severely depleted in LREE relative to MREE and HREE forming a dome shape. This is indicative of olivine fractionation [

36] (Stead et al., 2017). HREE in the Manus MORB is slightly more elevated than in the Feni rocks. Also noted is the lack of a pronounced Eu anomaly in all arcs attributed to the hydrous nature of magmas leading to the late onset of plagioclase fractionation.

Figure 20.

REE Spidergram normalized to primitive mantle [

40] (Sun & McDonough, 1989). Diagrams produced in IOGAS software. (A) Black lines represent Feni Island volcanic rocks vs Gallego igneous rocks, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands in blue (B) Feni REE signature in black vs Manus MORB (Woodhead et al, 1998) [

24] in red.

Figure 20.

REE Spidergram normalized to primitive mantle [

40] (Sun & McDonough, 1989). Diagrams produced in IOGAS software. (A) Black lines represent Feni Island volcanic rocks vs Gallego igneous rocks, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands in blue (B) Feni REE signature in black vs Manus MORB (Woodhead et al, 1998) [

24] in red.

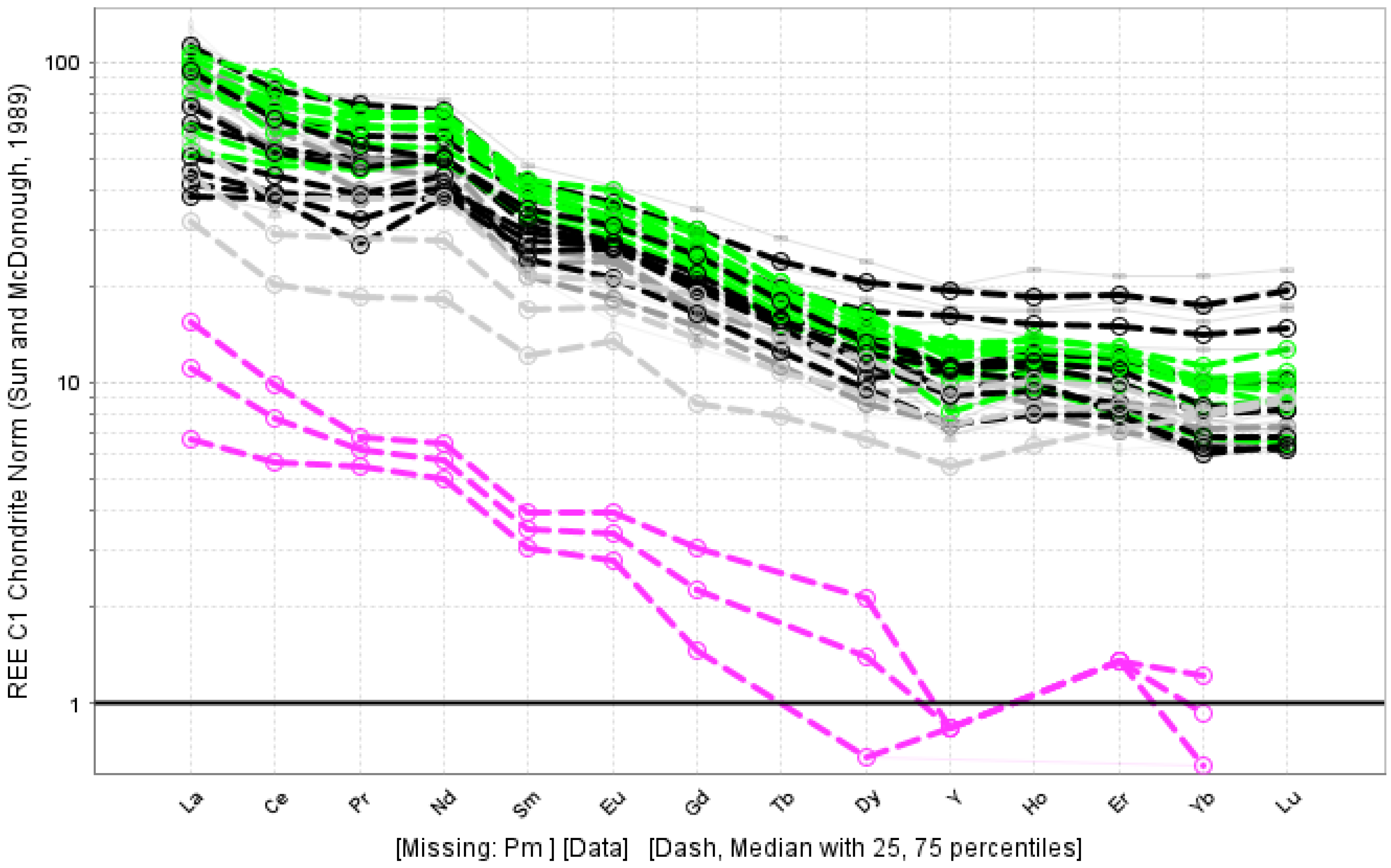

Rare Earth Elements of Feni magmatic rocks

REE plots were also generated for the Feni magmas according to their main lithologies.

Figure 21 displays the REE patterns of the volcanic and shallow porphyry intrusions of Feni: basaltic rocks (black), phonotephrite rocks (green), trachyandesite (grey) and trachydacite (pink). The basic or basaltic rocks and the phonolitic rocks of Niffin and Balangus are most enriched in REEs followed by the intermediate trachyandesite suites of Natong. The felsic trachydacite porphyries are the most depleted in REEs.

In general, the basalts to trachyandesite REE patterns are characterized by an enrichment in LREE, a steady decrease in MREE, and a flattening of the HREE. The felsic trachydacite porphyries of Feni are distinctly depleted in REE (also observed by Wallace et al., 1984 [

24]). The overall depletion of HREE relative to LREE is characteristic of the mafic volcanic rocks of Ambitle, Lihir, and Simberi.

Figure 21.

REE plot of all rock samples from Feni colour-attributed by rock-type. REE spidergrams normalized to C1 chondrite [

42] (McDonough and Sun, 1995). The black lines represent unaltered or slighlty altered basalt and trachybasalt rocks; green lines represent phonotephrite from Niffin; greys represent trachyandesite from Natong; pink lines are felsic trachydacite porphyry (F33, F12) which are float samples from the quartz trachyte domes.

Figure 21.

REE plot of all rock samples from Feni colour-attributed by rock-type. REE spidergrams normalized to C1 chondrite [

42] (McDonough and Sun, 1995). The black lines represent unaltered or slighlty altered basalt and trachybasalt rocks; green lines represent phonotephrite from Niffin; greys represent trachyandesite from Natong; pink lines are felsic trachydacite porphyry (F33, F12) which are float samples from the quartz trachyte domes.

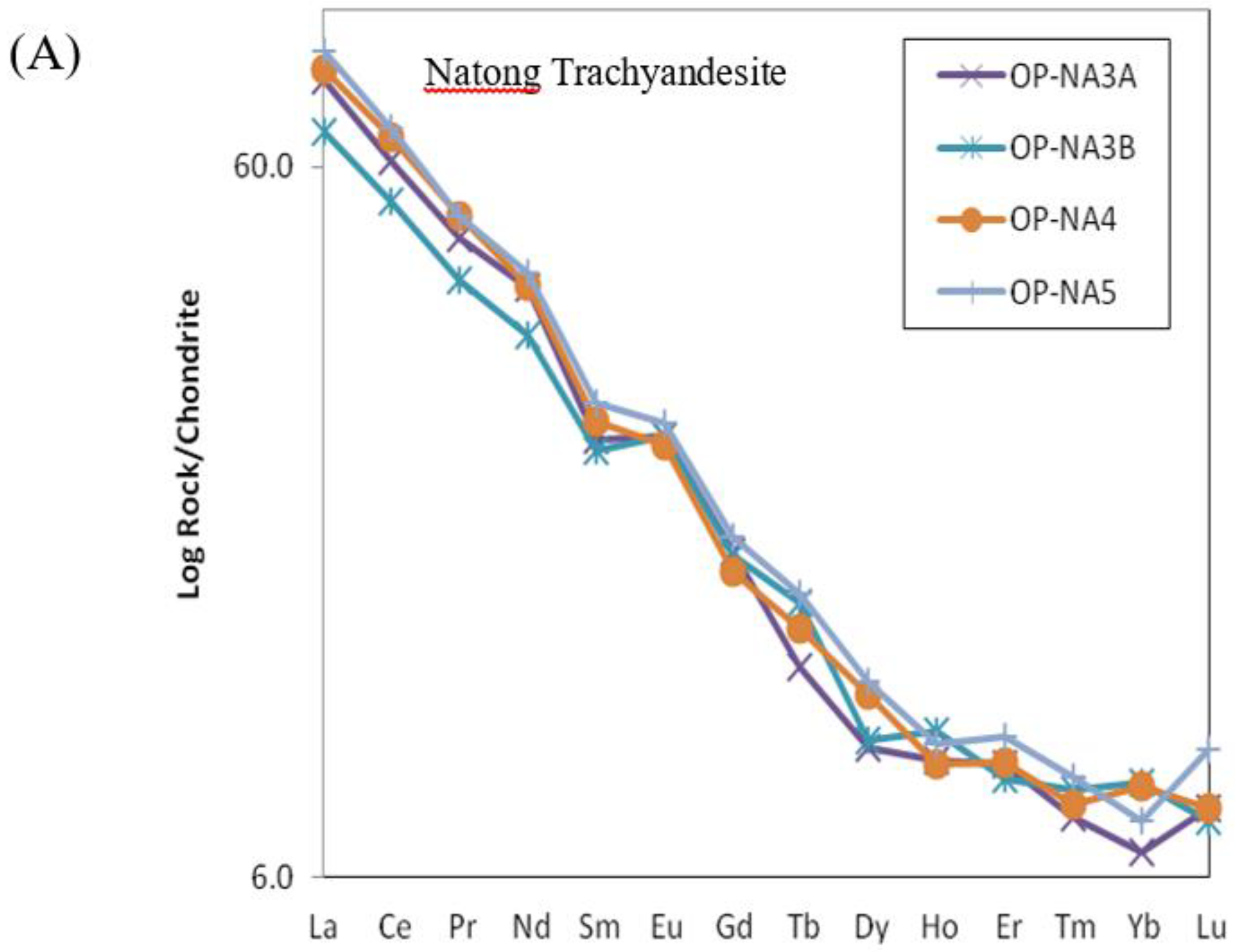

Figure 22 represents REE spider plots for trachyandesite (A) and basaltic suites (B) in Feni. There appears to be a slight negative Ce anomaly in the Feni basaltic rocks but none in the trachyandesite. A slight positive anomaly exists for the Eu in the trachyandesite suite of Natong (possibly due the hydrothermal alteration) but not in the basalt. In general, a negative Eu anomaly is not observed in the Feni magmas and thus suggests that plagioclase did not fractionate in the source area probably as a result of the presence of water or that plagioclase crystals did not physically separate from the magma. Similarly, [

41] McInnes and Cameron (1994) also showed that basalts from Simberi displayed positive Eu anomalies and negative Ce anomalies

Figure 22.

REE patterns of trachyandesite and basalt samples from Ambitle analysed by ICP-MS. Values normalized to CI chondrite [

42] (McDonough and Sun, 1995). (a) REE plot of the Natong trachyandesite. (b) REE patterns of basaltic samples from Niffin outcrops and Ambitle in general.

Figure 22.

REE patterns of trachyandesite and basalt samples from Ambitle analysed by ICP-MS. Values normalized to CI chondrite [

42] (McDonough and Sun, 1995). (a) REE plot of the Natong trachyandesite. (b) REE patterns of basaltic samples from Niffin outcrops and Ambitle in general.

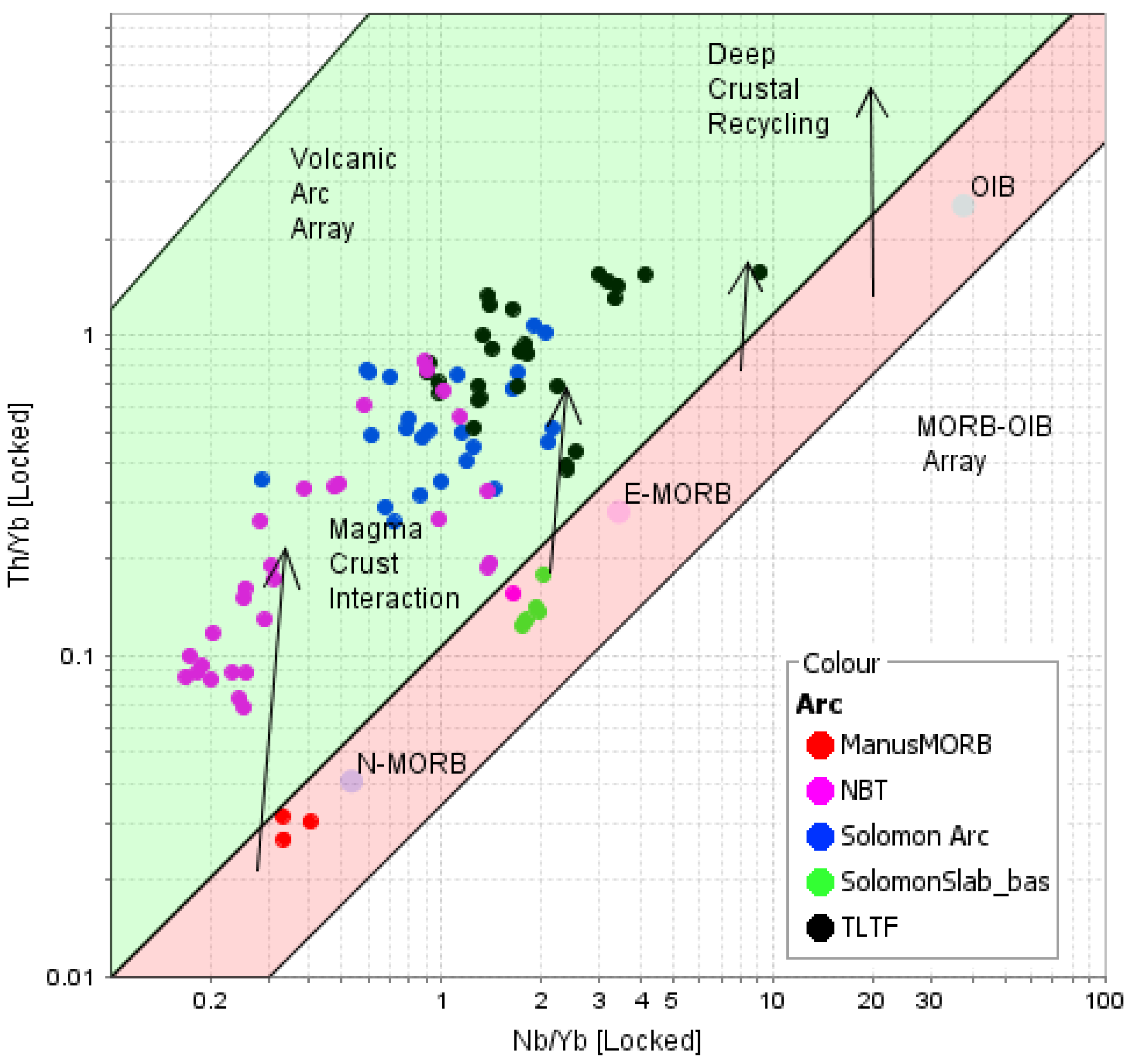

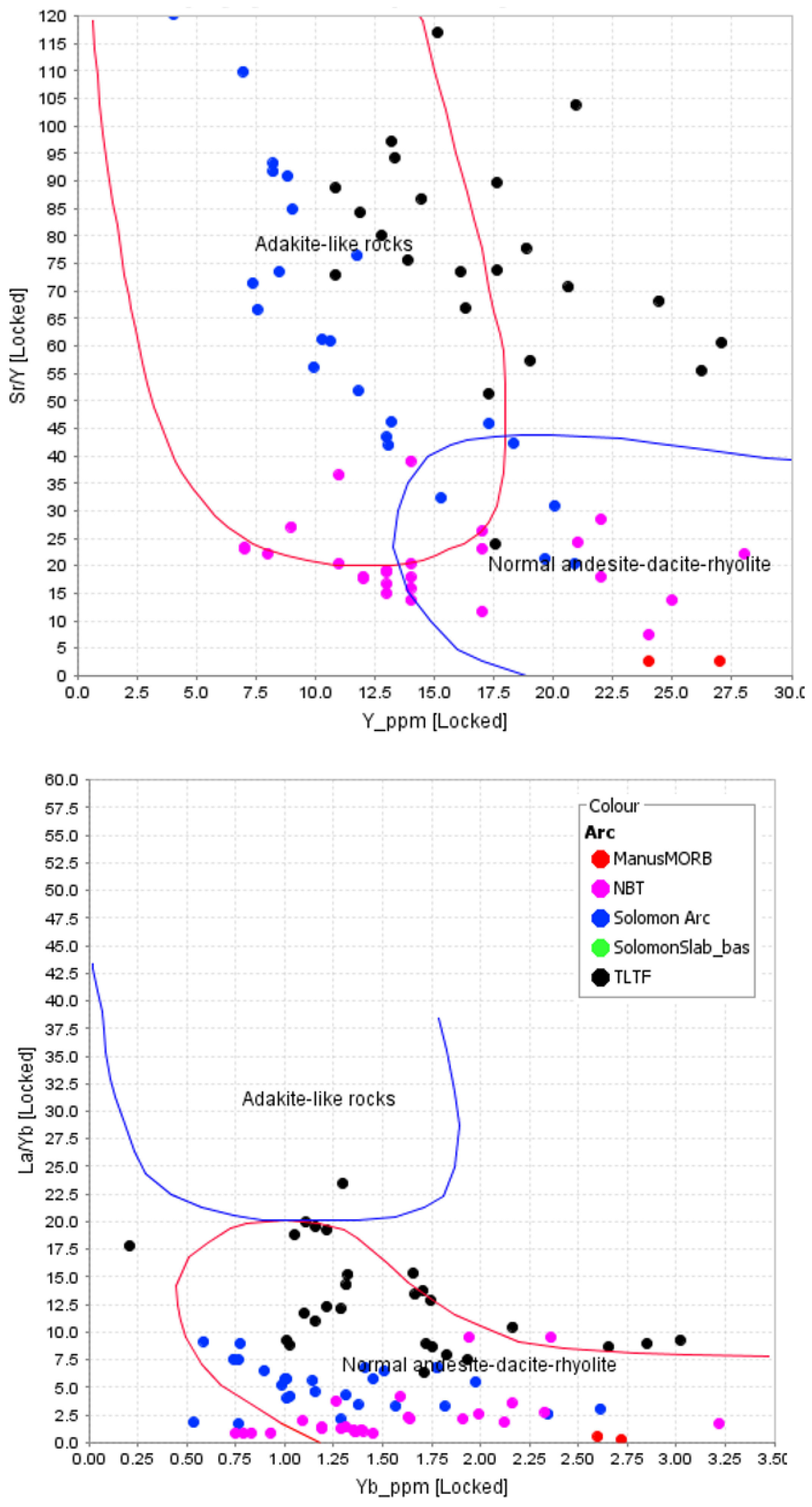

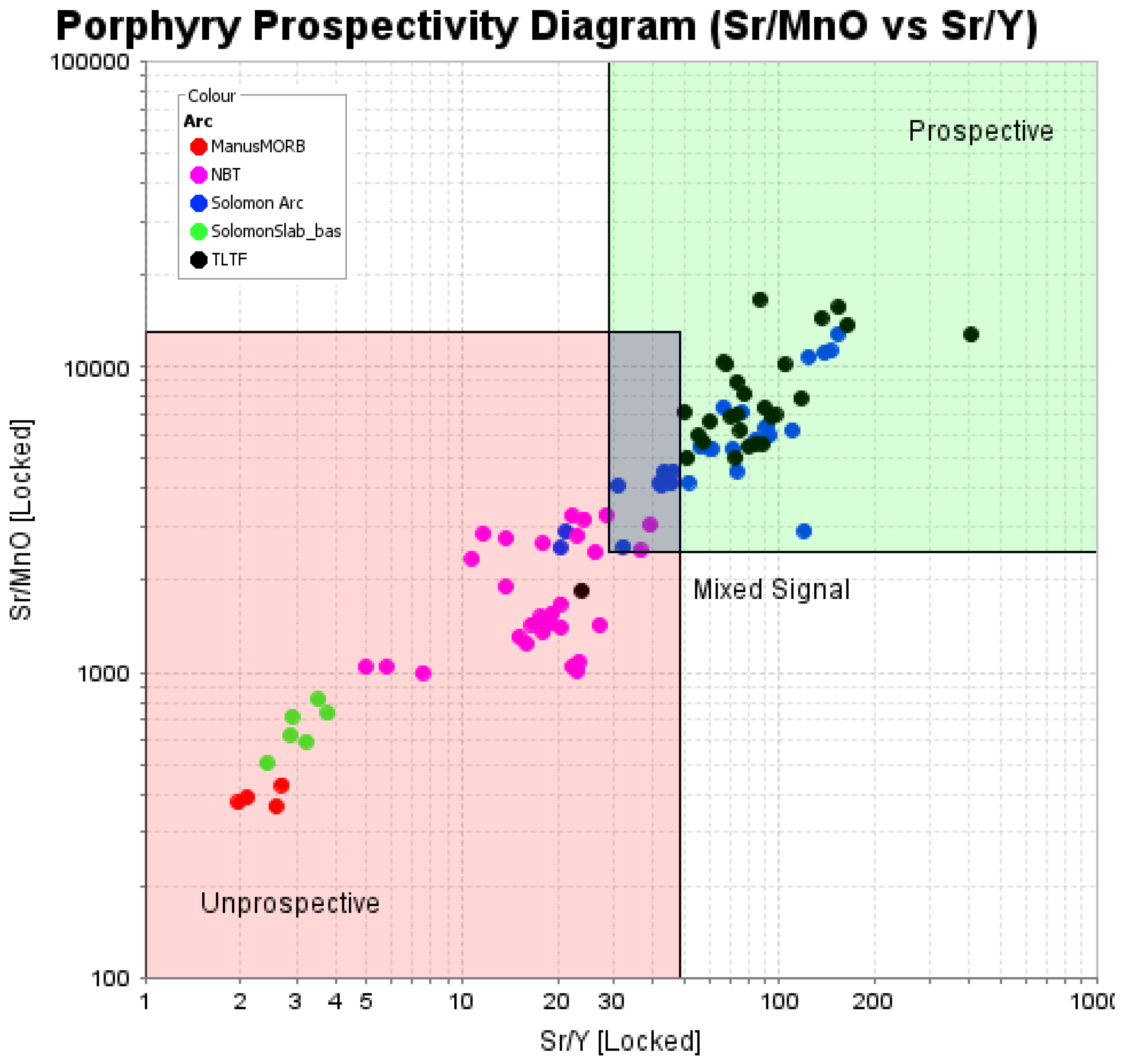

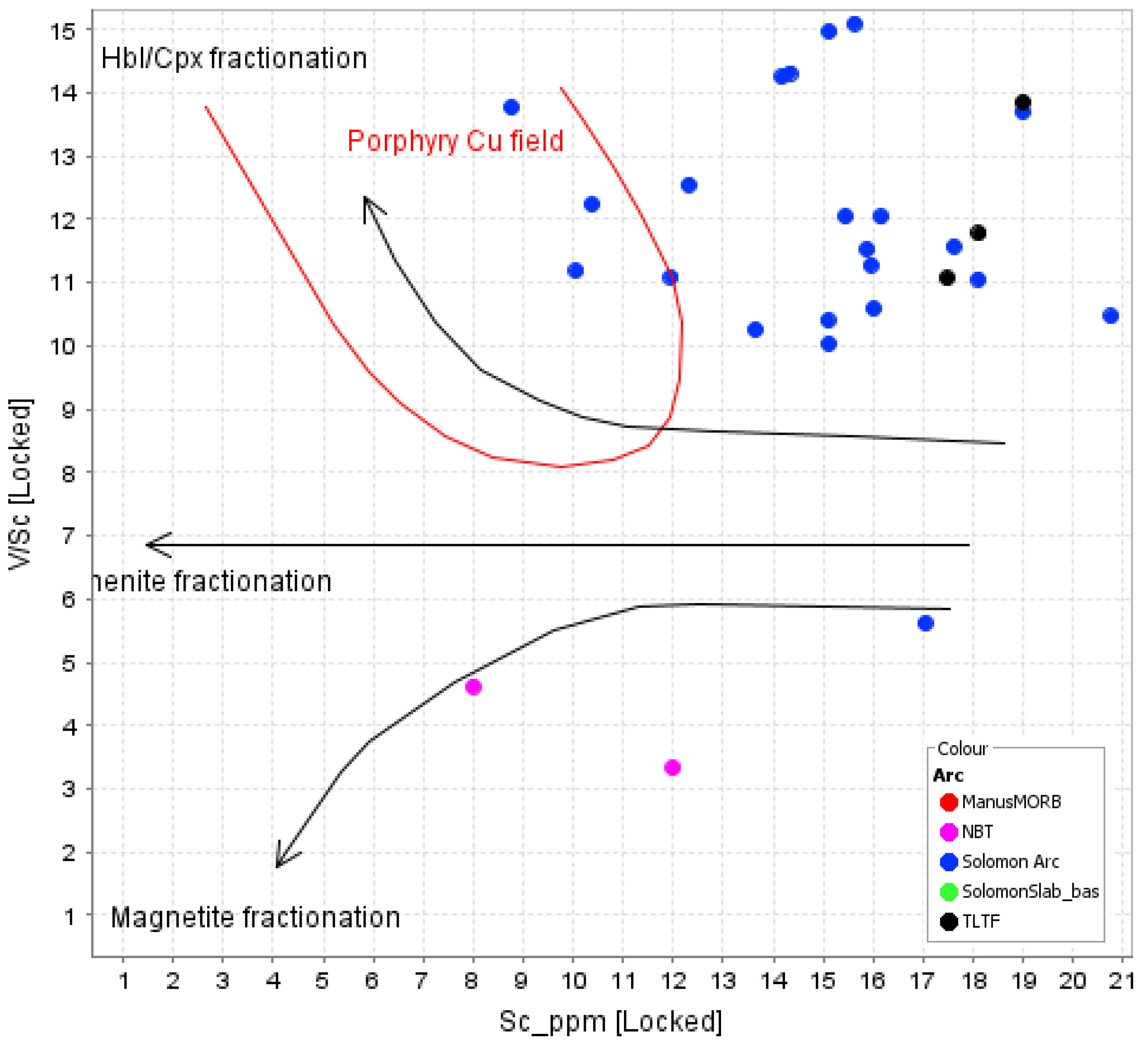

Discrimination & Classification diagrams using trace elements

The trace element data for Feni and the neighboring arcs were also plotted in discrimination diagrams for basalt and adakite to fingerprint their tectonic evolution or origin (

Figure 23, 24). The Th/Yb vs Nb/Yb plot [

43] (Pearce, 2008) in

Figure 23 generally shows that the Feni (or TLTF), Solomon and New Britain igneous rocks have volcanic-arc signatures whilst the Manus MORB is normal MORB (ie N-MORB).

Figure 23.

Th/Yb vs Nb/Yb Basalt Discrimination Plot [

43] (Pearce, 2008) of Feni (TLTF) volcanics, New Britain trench arc volcanics, Manus MORB and Gallego volcanic rocks (Solomon arc). Basalt classification diagram with Th-Nb as proxy for crustal input, divided into oceanic basalts and volcanic arc basalts field. Acronyms: MORB- Mid-Oceanic Ridge Basalt, OIB- Ocean-Island Basalt, N-MORB -Normal-MORB, E-MORB- Plume-MORB. N-MORB is depleted in trace elements compared to E-MORB.

Figure 23.