Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pohl, C.S.; Medland, J.E.; Moeser, A.J. Early-life stress Origins of gastrointestinal disease: animal models, intestinal pathophysiology, and translational implications. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015, 309, G927–G941. [Google Scholar]

- Pluske, J.R. Invited review: aspects of gastrointestinal tract growth and maturation in the pre-and postweaning period of pigs. J Anim Sci 2016, 94, 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Siemińska, I.; Pejsak, Z. Impact of stress on the functioning of the immune system, swine health, and productivity. Med Weter 2022, 78, 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.; Crenshaw, J.D.; Polo, J. The biological stress of early weaned piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2013, 4, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rhouma, M.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Beaudry, F.; Letellier, A. Post weaning diarrhea in pigs: Risk factors and non-colistin-based control strategies. Acta Vet Scand 2017, 59, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, P.A. Alternatives to antibiotics as growth promoters for use in swine production: A review. J Anim Sci Biotechnol, 2013, 4, 1–12.

- Liu, H.Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, M.; Yuan, L.; Li, S.; Gu, F.; Hu, P.; Chen, S.; Cai, D. Alternatives to antibiotics in pig production: looking through the lens of immunophysiology. Stress Biol 2024, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, T.C.R. , Barreyro, A.A., Rubio, S.R., González, Y. M.; García, K. E.; Soto, J.G.G.; Mariscal-Landín, G. Growth performance, diarrhoea incidence, and nutrient digestibility in weaned piglets fed an antibiotic-free diet with dehydrated porcine plasma or potato protein concentrate. Ann Anim Sci.

- Parra-Alarcón, E.; de Jesús Hijuitl Valeriano, T.; Landín, G.M.; De Souza, T.C.R. Concentrado de proteína de papa: una posible alternativa al uso de antibióticos en las dietas para lechones destetados. revisión. Rev Mex Cienc Pecu.

- Beals, K.A. Potatoes, Nutrition and Health. Am. J. Potato Res 2019, 96, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, W.N.; Soladoye, O.P. Towards potato protein utilisation: Insights into separation, functionality and bioactivity of patatin. Int J Food Sci Technol 2020, 55, 2314–2322. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, C.; Galli, G.; Kurozawa, L. Potato protein: Current review of structure, technological properties, and potential application on spray drying microencapsulation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 6323, 6564–6579. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutto, R.A.; Khanal, S.; Wang, M.; Iqbal, S.; Fan, Y.; Yi, J. Potato protein as an emerging high-quality: Source, extraction, purification, properties functional, nutritional, physicochemical, and processing, applications, and challenges using potato protein. Food Hydrocoll 2024, 110415, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-García, K.; de Souza, T. C. R.; Díaz-Muñoz, M.; Bautista-Marín, S.E. Nivel dietético de concentrado de proteína de papa y su efecto sobre la concentración intestinal de citocinas y ácidos grasos volátiles en lechones destetados. Rev Mex Cienc Pecu 2025, 16, 1–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bártová, V.; Bárta, J.; Jarošová, M. Antifungal and antimicrobial proteins and peptides of potato Solanum tuberosum L. tubers and their applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 103, 5533–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Benson, A.K.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Shared mechanisms among probiotic taxa: Implications for general probiotic claims. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2018, 49, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijan, S. Probiotics and their antimicrobial effect. Microorganisms 2023, 112, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luise, D.; Spinelli, E.; Correa, F.; Nicodemo, A.; Bosi, P.; Trevisi, P. The effect of a single, early-life administration of a probiotic on piglet growth performance and faecal microbiota until weaning. Ital J Anim Sci 2021, 20, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wen, H.; Wan, H.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. Yeast probiotic and yeast products in enhancing livestock feeds utilization and performance: An overview. J Fungi 811, 1191–1202. [CrossRef]

- Parada, J.; Magnoli, A.; Isgro, M.C. , Poloni, V., Fochesato, A., Martínez, M.P., Carranza A., Cavaglieri, L. In-feed nutritional additive probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii RC009 can substitute for prophylactic antibiotics and improve the production and health of weaning pigs. Vet World, 1035. [Google Scholar]

- Alkalbani, N.S.; Osaili, T.M.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Olaimat, A.N.; Liu, S.Q.; Shah, N.P.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Ayyash, M.M. Assessment of yeasts as potential probiotics: A review of gastrointestinal tract conditions and investigation methods. J Fungi 2022, 84, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchette, K.J.; Carroll, J.A.; Allee, G.L.; Matteri, R.L.; Dyer, C.J.; Beausang, L.A.; Zannelli, M.E. Effect of spray-dried plasma and lipopolysaccharide exposure on weaned pigs: I. Effects on the immune axis of weaned pigs. J Anim Sci 2002, 802, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreeuwenberg, M.A.M.; Verdonk, J.M.A.J.; Gaskins, H.R.; Verstegen, M.W.A. Small intestine epithelial barrier function is compromised in pigs with low feed intake at weaning. J Nutr 2001, 1315, 1520–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

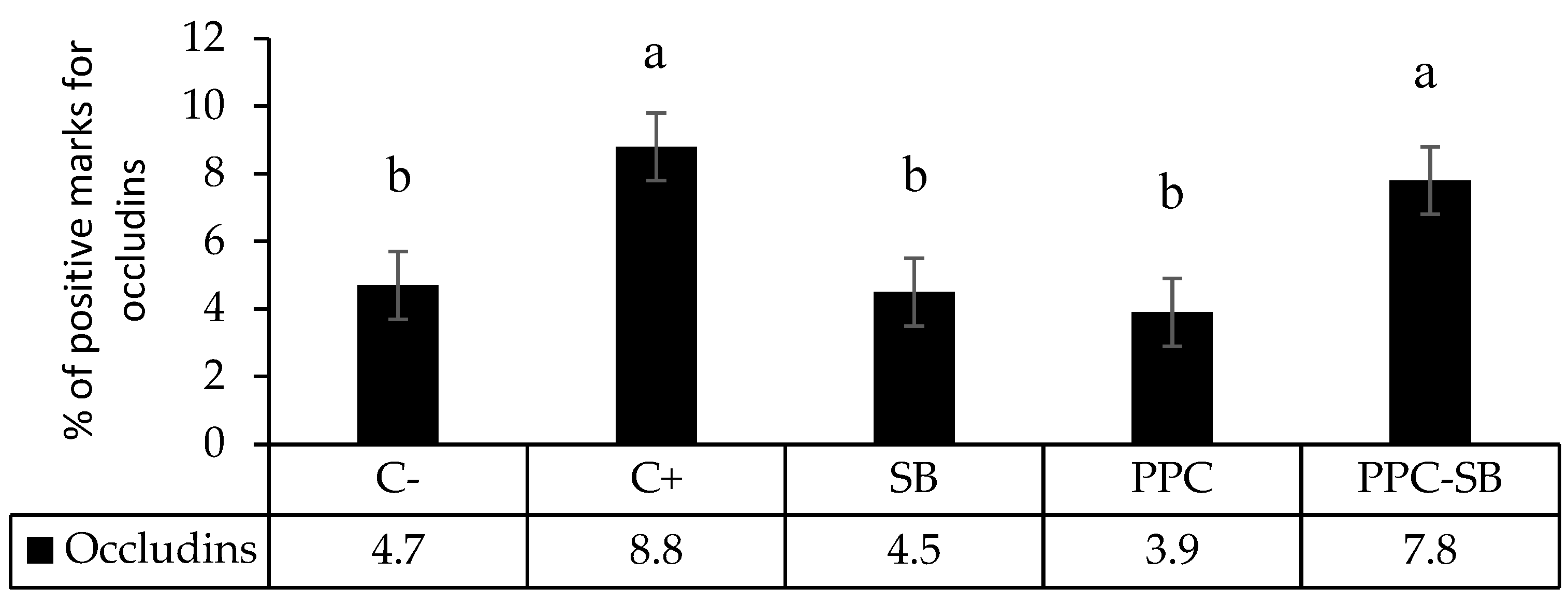

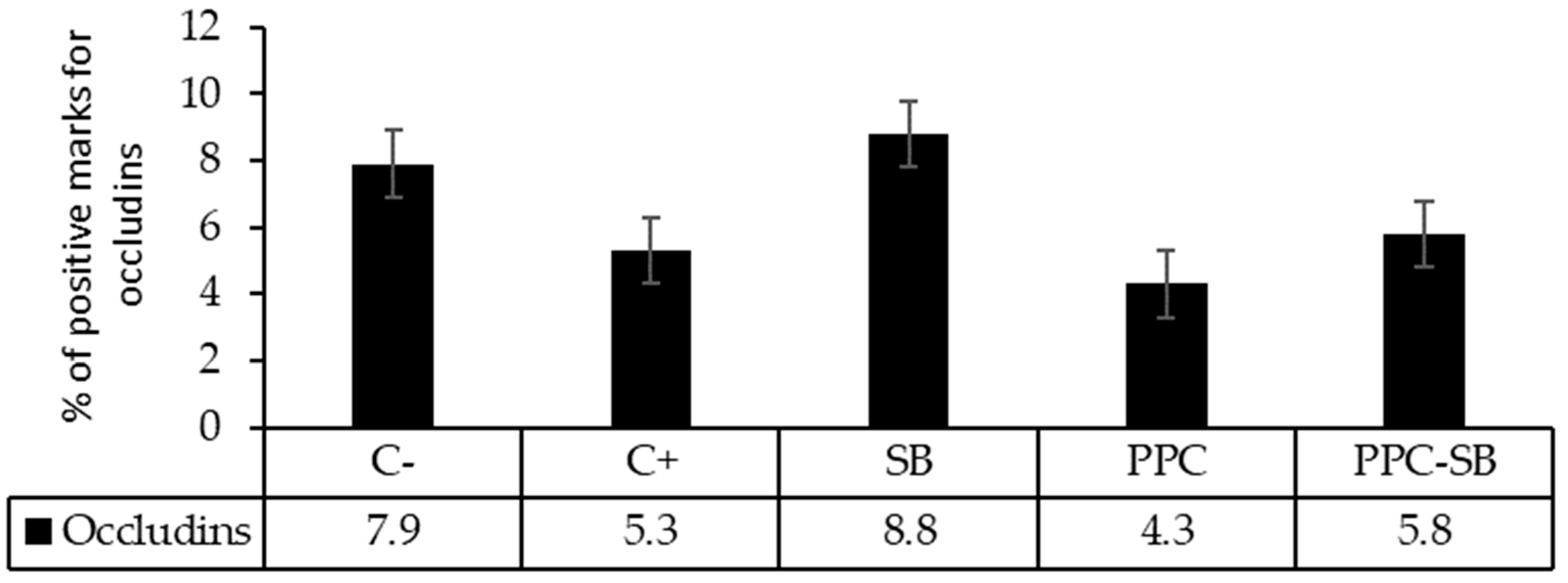

- Saitou, M.; Furuse, M.; Sasaki, H.; Schulzke, J.; Fromm, M.; Takano, H.; Noda, T.; Tsukita, S. Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol Biol Cell 2000, 1112, 4131–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIOMS. International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals. In: Organization WH editor. International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals. Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences. Geneva; 1985.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. Publication date: , 2001. Available online:http://legismex.mty.itesm.mx/normas/zoo/zoo062.pdf accessed on 09 august 2024. 22 August.

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Swine, 11th ed.; National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Marín, S.; Escobar-García, K.; Molina-Aguilar, C.; Mariscal-Landín, G.; Aguilera-Barreyro, A.; Díaz-Muñoz, M.; de Souza, T.R. Antibiotic-free diet supplemented with live yeasts decreases inflammatory markers in the ileum of weaned piglets. S Afr J Anim Sci 2020, 503, 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Pita-López, W.; Gomez-Garay, M.; Blanco-Labra, A.; Aguilera-Barreyro, A.; Souza, T.C.R.; Olvera-Ramírez, A.M.; Ferriz-Martínez, R.A.; García-Gasca, T. Tepary bean Phaseolus acutifolius lectin fraction provokes reversible adverse effects on rats’ digestive tract. Toxicol Res 2020, 95, 714–725. [Google Scholar]

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. Publication date: , 1995. NOM-113-SSA1-1994. Bienes y servicios. C. Available online on http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Documentos/Federal/wo69536.pdf accessed on 09 august 2024. 25 August.

- De Man, J.C.; Rogosa, M.; Sharpe, M.E.A. Medium for the Cultivation of Lactobacilli. J Appl Bacteriol 1960, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, R.O.; Aherne, F.X. Influence of dietary nutrient density, level of feed intake and weaning age on young pigs. II. Apparent nutrient digestibility and incidence and severity of diarrhea. Can J Anim Sci 1987, 674, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluske, J.R.; Hampson, D.J.; Williams, I.H. Factors influencing the structure and function of the small intestine in the weaned pig: a review. Livest Prod Sci 1997, 511, 215–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ebner, S.; Schoknecht, P.; Reeds, P.; Burrin, D. Growth and metabolism of gastrointestinal and skeletal muscle tissues in protein-malnourished neonatal pigs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 1994, 2666, R1736–R1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijuitl-Valeriano, T.J. Efecto del nivel de inclusión de concentrado de proteína de papa en la dieta de lechones sobre algunos indicadores de la salud intestinal. Master ina Helth and Produ, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro. Querétaro, Qro: Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro; 2021. Available online: https://ri-ng.uaq.mx/browse?type=author&value=Teresita+De+Jesus+Hijuitl+Valeriano&value_lang=es_ES.

- Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Tan, X.; Wang, L. ; Xiong, X; Wang, Q.; Yang, H.; Yin, Y. The developmental changes in intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and shedding in weaning piglets. Anim Nutr.

- Schubert, D.C.; Mößeler, A.; Ahlfänger, B.; Langeheine, M.; Brehm, R.; Visscher, C.; El-Wahab, A.A.; Kamphues, J. Influences of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency on nutrient digestibility, growth parameters as well as anatomical and histological morphology of the intestine in a juvenile pig model. Front Med 9, 1–12.

- Silk, D. Digestion and Absorption of Dietary Protein in Man. Proc. Nutr. Soc 1980, 391, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Wang, A.; Zeng, X.; Hou, C.; Liu, H.; Qiao, S. Lactobacillus reuteri I5007 modulates tight junction protein expression in IPEC-J2 cells with LPS stimulation and in newborn piglets under normal conditions. BMC Microbiol 2015, 151, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Yang, D.; Huang, S.; Wei, Z.; Liang, X.; Wang, Z. Supplementation with yeast culture improves the integrity of intestinal tight junction proteins via NOD1/NF-ΚB P65 pathway in weaned piglets and H2O2-challenged IPEC-J2 cells. J Funct Foods 2020, 72, 104058. [Google Scholar]

- Barszca, M.; Skomiał, J. The development of the small intestine of piglets – chosen aspects. J Anim Feed Sci. 2011, 20, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- De Lange, C.F.M.; Pluske, J.; Gong, J.; Nyachoti, C.M. Strategic use of feed ingredients and feed additives to stimulate gut health and development in young pigs. Livest Sci 2010, 134, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- García, K.E.; de Souza, T.C.R.; Landín, G.M.; Barreyro, A.A.; Santos, M.G.B.; Soto, J.G.G. Microbial fermentation patterns, diarrhea incidence, and performance in weaned piglets fed a low protein diet supplemented with probiotics. FNS 2014, 518, 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Sampath, V.; Heon Baek, D.; Shanmugam, S.; Kim, I.H. H. Dietary inclusion of blood plasma with yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae supplementation enhanced the growth performance, nutrient digestibility, Lactobacillus count, and reduced gas emissions in weaning pigs. Animals 2021, 113, 759–771. [Google Scholar]

- Parada, J.; Magnoli, A.; Poloni, V.; Corti Isgro, M.; Rosales Cavaglieri, L.; Luna, M. J.; Carranza, A.; Cavaglieri, L. Pediococcus pentosaceus RC007 and Saccharomyces boulardii RC009 as antibiotic alternatives for gut health in post-weaning pigs. J Appl Microbiol 2024, 135, lxae282. [Google Scholar]

- Gresse, R.; Chaucheyras Durand, F.; Dunière, L.; Blanquet-Diot, S.; Forano, E. Microbiota composition and functional profiling throughout the gastrointestinal tract of commercial weaning piglets. Microorganisms 2019, 79, 343–366. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Bao, C.; Wang, J.; Zang, J.; Cao, Y. Administration of Saccharomyces boulardii mafic-1701 improves feed conversion ratio, promotes antioxidant capacity, alleviates intestinal inflammation and modulates gut microbiota in weaned piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Qayum, A.; Xiuxiu, Z.; Liu, L.; Hussain, K.; Yue, P.; Yue, S. Potato protein: An emerging source of high quality and allergy free protein, and its possible future based products. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110583. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; He, Y.; Zhang, W.; He, J. Potato proteins for technical applications: Nutrition, isolation, modification and functional properties-A review. IFSET 2024, 91, 103533. [Google Scholar]

| Ingredients (%) | Experimental diets | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C- | C+ | SB | PPC | PPC-SB | |

| Maize | 44.7 | 44.56 | 44.68 | 43.78 | 43.77 |

| Soybean Meal | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Soybean Isolate | 8.32 | 8.34 | 8.33 | 3.74 | 3.74 |

| Potato Protein Concentrate | 6 | 6 | |||

| Antibiótic1 | 0.05 | ||||

| Yeast2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| Menhaden Fish Meal | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Sweet Whey Milk | 24.69 | 24.69 | 24.69 | 24.69 | 24.69 |

| Maize oil | 2.45 | 2.52 | 2.45 | 2.23 | 2.23 |

| L-Lysine HCl | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| L-Threonine | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| DL-Methionine | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| L-Tryptophan | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| L-Valine | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| Salt | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Calcium Carbonate | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| Dicalcium Phosphate | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| Titanium Dioxide | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Vitamins Premix3 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Minerals Premix4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Items | Experimental diets | p | SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C- | C+ | SB | PPC | PPC-SB | |||

| ADFI (g/day) | |||||||

| Week 1 | 105 | 96 | 98 | 103 | 105 | NS | 3.1 |

| Week 2 | 255 | 258 | 256 | 265 | 271 | NS | 5.3 |

| ADG (g/day) | |||||||

| Week 1 | -28 | -21 | -30 | -13 | -15 | NS | 4.4 |

| Week 2 | 210 | 230 | 215 | 219 | 224 | NS | 5.4 |

| FE | |||||||

| Week 1 | -0.270 | 0.249 | -0.345 | -0.194 | -0.191 | NS | 0.052 |

| Week 2 | 0.821 | 0.914 | 0.835 | 0.830 | 0.833 | NS | 0.015 |

| Items | Experimental diets | p | SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C- | C+ | SB | PPC | PPC-SB | |||

| Body weight (Kg) | 8.100 | 8.527 | 7.715 | 8.238 | 7.933 | NS | 0.177 |

| Relative body weight (g*BW-1) | |||||||

| Pancreas | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.1 | NS | 0.065 |

| Liver | 29 | 32 | 30 | 33 | 28 | NS | 0.818 |

| Estomach | 8.8 | 8.1 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 7.9 | NS | 0.312 |

| Small Intestine | 61 | 57 | 58 | 65 | 60 | NS | 1.285 |

| Large Intestine | 17.7 | 19.8 | 18.1 | 18.2 | 19.8 | NS | 0.794 |

| pH of Contents | |||||||

| Estomach | 2.8 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.7 | NS | 0.163 |

| Yeyune | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.7 | NS | 0.064 |

| Ileum | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 5.9 | NS | 0.081 |

| Ceacum | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.5 | NS | 0.061 |

| Colon | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.6 | NS | 0.047 |

| Items | Experimental diets | p | SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C- | C+ | SB | PPC | PPC-SB | |||

| Duodenum | |||||||

| VH (μm) | 344 | 369 | 363 | 331 | 375 | NS | 6.8 |

| VW (μm) | 115bc | 130ab | 138a | 108c | 138a | 0.009 | 2.7 |

| CD (μm) | 197 | 223 | 213 | 227 | 240 | NS | 8.3 |

| Jejunum | NS | ||||||

| VH (μm) | 378b | 439a | 337b | 343b | 435a | 0.003 | 8.0 |

| VW (μm) | 112 | 123 | 111 | 94 | 109 | NS | 4.9 |

| CD (μm) | 236 | 247 | 202 | 244 | 234 | NS | 6.7 |

| Ileum | |||||||

| VH (μm) | 298 | 331 | 332 | 366 | 361 | NS | 9.9 |

| VW (μm) | 108 | 111 | 107 | 117 | 116 | NS | 3.1 |

| CD (μm) | 208 | 187 | 194 | 203 | 214 | NS | 5.3 |

| Colon CD (μm) | 320 | 312 | 305 | 299 | 337 | NS | 6.3 |

| Items | Experimental diets | p | SEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C- | C+ | SB | PPC | PPC-SB | |||

| Coliforms (UFC/g) | 7.4a | 5.7b | 7.5a | 7.2ab | 8.1a | 0.04 | 0.23 |

| Lactobacillus (UFC/g) | 3.5b | 4.1b | 5.9a | 3.8b | 5.7a | 0.001 | 0.19 |

| ID | |||||||

| Week 1 (days) | 4.6 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 4.8 | NS | 0.14 |

| Week 2 (days) | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | NS | 0.05 |

| SD | |||||||

| Week 1 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.4 | NS | 0.12 |

| Week 2 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | NS | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).