Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

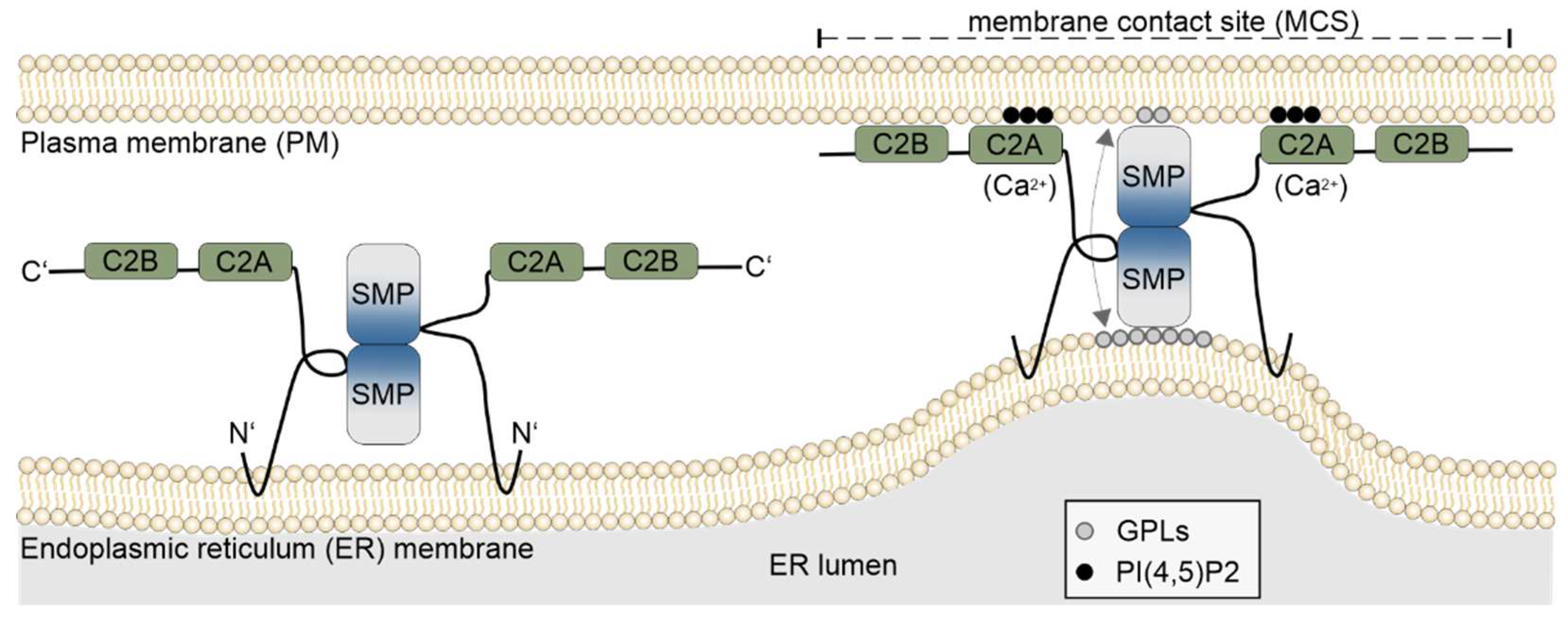

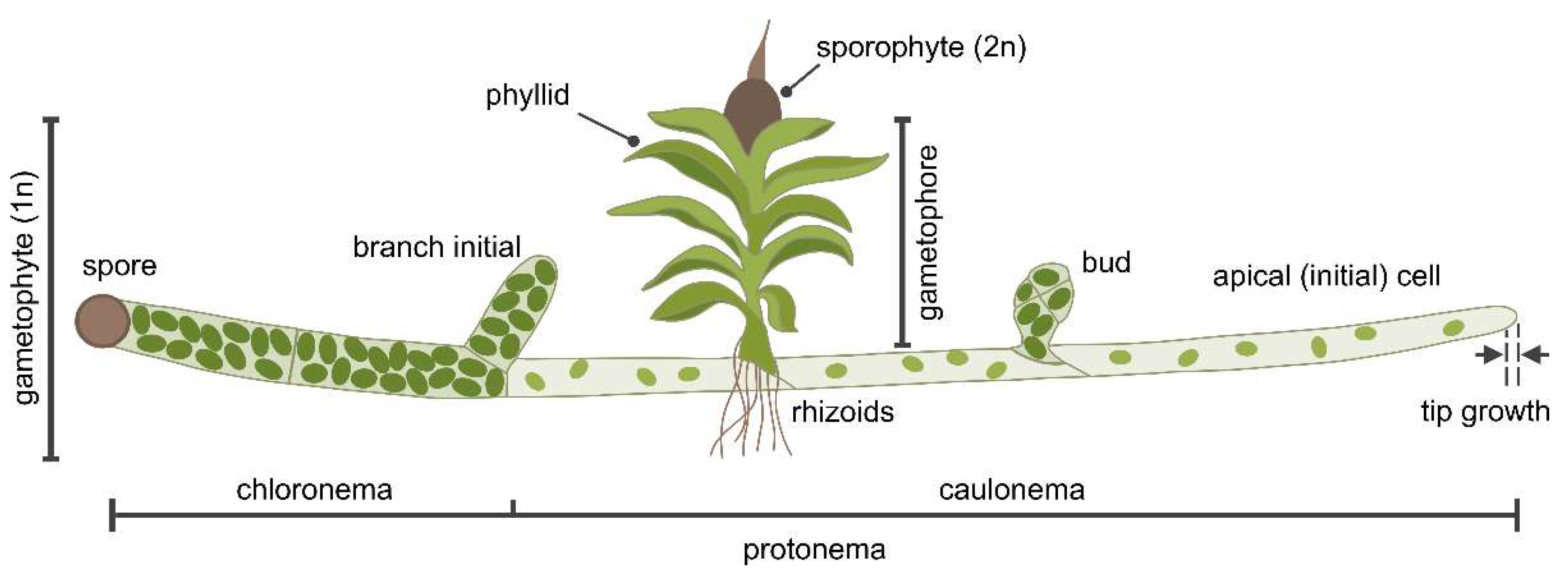

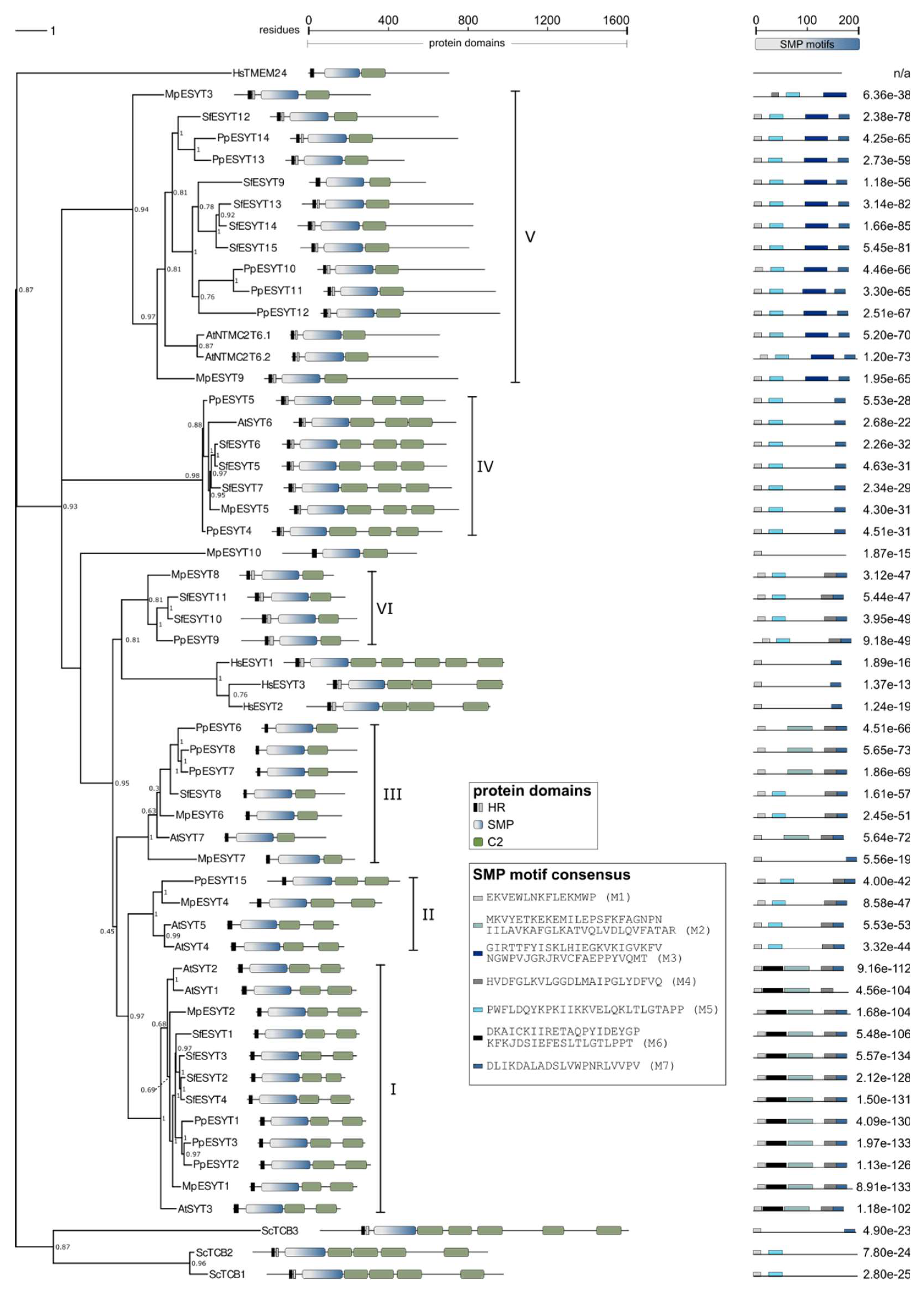

Membrane contact sites (MCSs) between the endoplasmic reticulum and the plasma membrane enable transport of lipids without membrane fusion in eukaryotes. Extended Synaptotagmins (ESYTs) can form and maintain MCSs, acting as tethers between two membrane compartments. In plants, ESYTs have been mainly investigated in the flowering plant Arabidopsis and shown to maintain the integrity of the plasma membrane, especially during stress responses such as cold acclimatization, mechanical trauma and salt stress. ESYTs are also present at MCSs of plasmodesmata, where they regulate defense responses by modulating cell-to-cell transfer of pathogens. Here, the analyis of ESYTs in plants was expanded to the bryophyte Physcomitrium patens, an extant representative of the earliest land plant lineages. P. patens was found to contain a larger number of ESYTs that were distributed in all previously established classes and an additional class not present in Arabidospsis. Motif discovery identified regions in the Synaptotagmin-like mitochondrial (SMP) domain that may explain phylogenetic relationships as well as protein function. These findings highlight the suitability of P. patens as a model organsim to study ESYT functions in tip growth, stress-responses and plasmodesmata-mediated transport, and open new directions of research regarding the function of MCSs in cellular processes and plant evolution.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. ESYTs in Plants

2.1. Membrane Contact Sites

2.2. Domain Structure and Functions of ESYTs

2.3. ESYTs in Arabidopsis

2.4. P. patens as a Model Organism for Membrane Dynamics

2.5. ESYTs in Bryophytes

3. Conclusions

4. Methods

4.1. Genome and Protein Databases Search

4.2. Protein Domains and Motif Analysis

4.3. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Construction

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saheki, Y.; De Camilli, P. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Plasma Membrane Contact Sites. Annu Rev Biochem 2017, 86, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toulmay, A.; Prinz, W.A. A conserved membrane-binding domain targets proteins to organelle contact sites. Journal of Cell Science 2012, 125, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, F.; Saheki, Y.; Idevall-Hagren, O.; Colombo, S.F.; Pirruccello, M.; Milosevic, I.; Elena; Sviatoslav; Borgese, N. ; De Camilli, P. PI(4,5)P2-Dependent and Ca2+-Regulated ER-PM Interactions Mediated by the Extended Synaptotagmins. Cell 2013, 153, 1494–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saheki, Y.; De Camilli, P. The Extended-Synaptotagmins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2017, 1864, 1490–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapire, A.L.; Voigt, B.; Jasik, J.; Rosado, A.; Lopez-Cobollo, R.; Menzel, D.; Salinas, J.; Mancuso, S.; Valpuesta, V.; Baluska, F.; et al. Arabidopsis synaptotagmin 1 is required for the maintenance of plasma membrane integrity and cell viability. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 3374–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Fuente, F.; Botella, M.A. Biological roles of plant synaptotagmins. European Journal of Cell Biology 2023, 102, 151335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebnev, G.; Cvitkovic, M.; Fritz, C.; Cai, G.; Smith, A.-S.; Kost, B. Quantitative Structural Organization of Bulk Apical Membrane Traffic in Pollen Tubes. Plant Physiology 2020, 183, 1559–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xing, J.; Lin, J. At the intersection of exocytosis and endocytosis in plants. New Phytologist 2019, 224, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voeltz, G.K.; Sawyer, E.M.; Hajnóczky, G.; Prinz, W.A. Making the connection: How membrane contact sites have changed our view of organelle biology. Cell 2024, 187, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Rouiller, C. Close topographical relationship between mitochondria and ergastoplasm of liver cells in a definite phase of cellular activity. The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology 1956, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbluth, J. Subsurface cisterns and their relationship to the neuronal plasma membrane. Journal of Cell Biology 1962, 13, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.; John Peter, A.T.; Kornmann, B. ER–mitochondria contact sites in yeast: Beyond the myths of ERMES. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2015, 35, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.J.; Voeltz, G.K. Structure and function of ER membrane contact sites with other organelles. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2016, 17, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venditti, R.; Masone, M.C.; De Matteis, M.A. ER-Golgi membrane contact sites. Biochemical Society Transactions 2020, 48, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, L.; Stefano, G.; Puggioni, M.P.; Kim, S.-J.; Lavell, A.; Froehlich, J.E.; Burkart, G.; Mancuso, S.; Benning, C.; Brandizzi, F. ER-associated VAP27-1 and VAP27-3 proteins functionally link the lipid-binding ORP2A at the ER-chloroplast contact sites. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorrano, L.; De Matteis, M.A.; Emr, S.; Giordano, F.; Hajnóczky, G.; Kornmann, B.; Lackner, L.L.; Levine, T.P.; Pellegrini, L.; Reinisch, K.; et al. Coming together to define membrane contact sites. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.M.; Buchanan, J.; Luik, R.M.; Lewis, R.S. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. Journal of Cell Biology 2006, 174, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sancho, J.; Vanneste, S.; Lee, E.; McFarlane, H.E.; Esteban del Valle, A.; Valpuesta, V.; Friml, J.; Botella, M.A.; Rosado, A. The Arabidopsis Synaptotagmin1 Is Enriched in Endoplasmic Reticulum-Plasma Membrane Contact Sites and Confers Cellular Resistance to Mechanical Stresses. Plant Physiology 2015, 168, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K.; Tamura, K.; Fukao, Y.; Shimada, T. Structural and functional relationships between plasmodesmata and plant endoplasmic reticulum–plasma membrane contact sites consisting of three synaptotagmins. New Phytologist 2020, 226, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, P.C.; Bharat, T.A.M.; Wozny, M.R.; Boulanger, J.; Miller, E.A.; Kukulski, W. Tricalbins Contribute to Cellular Lipid Flux and Form Curved ER-PM Contacts that Are Bridged by Rod-Shaped Structures. Developmental Cell 2019, 51, 488–502.e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hawkins, T.J.; Richardson, C.; Cummins, I.; Deeks, M.J.; Sparkes, I.; Hawes, C.; Hussey, P.J. The Plant Cytoskeleton, NET3C, and VAP27 Mediate the Link between the Plasma Membrane and Endoplasmic Reticulum. Current Biology 2014, 24, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretti, D.; Dahan, N.; Shimoni, E.; Hirschberg, K.; Lev, S. Coordinated Lipid Transfer between the Endoplasmic Reticulum and the Golgi Complex Requires the VAP Proteins and Is Essential for Golgi-mediated Transport. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2008, 19, 3871–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Gao, J.; Liang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Q.; Huang, S.; Jiang, L. Arabidopsis ORP2A mediates ER–autophagosomal membrane contact sites and regulates PI3P in plant autophagy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2205314119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, N.; Kuijl, C.; van der Kant, R.; Janssen, L.; Houben, D.; Janssen, H.; Zwart, W.; Neefjes, J. Cholesterol sensor ORP1L contacts the ER protein VAP to control Rab7–RILP–p150Glued and late endosome positioning. Journal of Cell Biology 2009, 185, 1209–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Richardson, C.; Hawkins, T.J.; Sparkes, I.; Hawes, C.; Hussey, P.J. Plant VAP27 proteins: Domain characterization, intracellular localization and role in plant development. New Phytologist 2016, 210, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Klemm, S.; Pain, C.; Duckney, P.; Bao, Z.; Stamm, G.; Kriechbaumer, V.; Bürstenbinder, K.; Hussey, P.J.; Wang, P. A novel plant actin-microtubule bridging complex regulates cytoskeletal and ER structure at ER-PM contact sites. Current Biology 2021, 31, 1251–1260.e1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R.; Lackner, L.L.; West, M.; DiBenedetto, J.R.; Nunnari, J.; Voeltz, G.K. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science 2011, 334, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.-K.; Chakrabarti, R.; Fan, X.; Schoenfeld, L.; Strack, S.; Higgs, H.N. Receptor-mediated Drp1 oligomerization on endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Cell Biology 2017, 216, 4123–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Duckney, P.; Zhang, T.; Fu, Y.; Li, X.; Kroon, J.; De Jaeger, G.; Cheng, Y.; Hussey, P.J.; Wang, P. TraB family proteins are components of ER-mitochondrial contact sites and regulate ER-mitochondrial interactions and mitophagy. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Lopez, N.; Pérez-Sancho, J.; del Valle, A.E.; Haslam, R.P.; Vanneste, S.; Catalá, R.; Perea-Resa, C.; Damme, D.V.; García-Hernández, S.; Albert, A.; et al. Synaptotagmins at the endoplasmic reticulum–plasma membrane contact sites maintain diacylglycerol homeostasis during abiotic stress. The Plant Cell 2021, 33, 2431–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinisch, K.M.; Prinz, W.A. Mechanisms of nonvesicular lipid transport. Journal of Cell Biology 2021, 220, e202012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, J.; DiGregorio, P.J.; Yeromin, A.V.; Ohlsen, K.; Lioudyno, M.; Zhang, S.; Safrina, O.; Kozak, J.A.; Wagner, S.L.; Cahalan, M.D.; et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. Journal of Cell Biology 2005, 169, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeromin, A.V.; Zhang, S.L.; Jiang, W.; Yu, Y.; Safrina, O.; Cahalan, M.D. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature 2006, 443, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vig, M.; Peinelt, C.; Beck, A.; Koomoa, D.L.; Rabah, D.; Koblan-Huberson, M.; Kraft, S.; Turner, H.; Fleig, A.; Penner, R.; et al. CRACM1 Is a Plasma Membrane Protein Essential for Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry. Science 2006, 312, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakriya, M.; Feske, S.; Gwack, Y.; Srikanth, S.; Rao, A.; Hogan, P.G. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature 2006, 443, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putney, J.W. A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium 1986, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L.; Parker, P.J.; Rhee, L.; Yang-Feng, T.L.; Chen, E.; Waterfield, M.D.; Francke, U.; Ullrich, A. Multiple, Distinct Forms of Bovine and Human Protein Kinase C Suggest Diversity in Cellular Signaling Pathways. Science 1986, 233, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, W.D.; Tsavaler, L.; Reichardt, L.F. Identification of a synaptic vesicle-specific membrane protein with a wide distribution in neuronal and neurosecretory tissue. Journal of Cell Biology 1981, 91, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.R. How Does Synaptotagmin Trigger Neurotransmitter Release? Annual Review of Biochemistry 2008, 77, 615–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Maximov, A.; Shin, O.-H.; Dai, H.; Rizo, J.; Südhof, T.C. A Complexin/Synaptotagmin 1 Switch Controls Fast Synaptic Vesicle Exocytosis. Cell 2006, 126, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brose, N.; Petrenko, A.G.; Südhof, T.C.; Jahn, R. Synaptotagmin: A Calcium Sensor on the Synaptic Vesicle Surface. Science 1992, 256, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perin, M.S.; Fried, V.A.; Mignery, G.A.; Jahn, R.; Südhof, T.C. Phospholipid binding by a synaptic vesicle protein homologous to the regulatory region of protein kinase C. Nature 1990, 345, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugita, S.; Shin, O.H.; Han, W.; Lao, Y.; Südhof, T.C. Synaptotagmins form a hierarchy of exocytotic Ca(2+) sensors with distinct Ca(2+) affinities. Embo j 2002, 21, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, S.-W.; Chang, W.-P.; Südhof, T.C. E-Syts, a family of membranous Ca 2+-sensor proteins with multiple C2 domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 3823–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Hong, W. Diverse membrane-associated proteins contain a novel SMP domain. The FASEB Journal 2006, 20, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauder, C.M.; Wu, X.; Saheki, Y.; Narayanaswamy, P.; Torta, F.; Wenk, M.R.; De Camilli, P.; Reinisch, K.M. Structure of a lipid-bound extended synaptotagmin indicates a role in lipid transfer. Nature 2014, 510, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, T.P. Remote homology searches identify bacterial homologues of eukaryotic lipid transfer proteins, including Chorein-N domains in TamB and AsmA and Mdm31p. BMC Molecular and Cell Biology 2019, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Bian, X.; Ma, L.; Cai, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Karatekin, E.; De Camilli, P.; Zhang, Y. Stepwise membrane binding of extended synaptotagmins revealed by optical tweezers. Nature Chemical Biology 2022, 18, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheki, Y.; Bian, X.; Schauder, C.M.; Sawaki, Y.; Surma, M.A.; Klose, C.; Pincet, F.; Reinisch, K.M.; De Camilli, P. Control of plasma membrane lipid homeostasis by the extended synaptotagmins. Nature Cell Biology 2016, 18, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Jiao, L.; Liu, R.; Wang, K.; Ma, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G.; et al. Insights into membrane association of the SMP domain of extended synaptotagmin. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K.; Tamura, K.; Ueda, H.; Ito, Y.; Nakano, A.; Hara-Nishimura, I.; Shimada, T. Synaptotagmin-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum-Plasma Membrane Contact Sites Are Localized to Immobile ER Tubules. Plant Physiol 2018, 178, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manford, A.G.; Stefan, C.J.; Yuan, H.L.; MacGurn, J.A.; Emr, S.D. ER-to-Plasma Membrane Tethering Proteins Regulate Cell Signaling and ER Morphology. Developmental Cell 2012, 23, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavente, J.L.; Siliqi, D.; Infantes, L.; Lagartera, L.; Mills, A.; Gago, F.; Ruiz-López, N.; Botella, M.A.; Sánchez-Barrena, M.J.; Albert, A. The structure and flexibility analysis of the Arabidopsis synaptotagmin 1 reveal the basis of its regulation at membrane contact sites. Life Science Alliance 2021, 4, e202101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Gulbranson, D.R.; Paine, A.; Rathore, S.S.; Shen, J. Extended synaptotagmins are Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer proteins at membrane contact sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 4362–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Busnadiego, R.; Saheki, Y.; De Camilli, P. Three-dimensional architecture of extended synaptotagmin-mediated endoplasmic reticulum–plasma membrane contact sites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, E2004–E2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Takata, N.; Uemura, M.; Kawamura, Y. Arabidopsis synaptotagmin SYT1, a type I signal-anchor protein, requires tandem C2 domains for delivery to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 23165–23176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idevall-Hagren, O.; Lü, A.; Xie, B.; De Camilli, P. Triggered Ca2+ influx is required for extended synaptotagmin 1-induced ER-plasma membrane tethering. The EMBO Journal 2015, 34, 2291–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Bacaj, T.; Zhou, A.; Tomchick, D.R.; Südhof, T.C.; Rizo, J. Structure and Ca2+ Binding Properties of the Tandem C2 Domains of E-Syt2. Structure 2014, 22, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Poser, C.; Ichtchenko, K.; Shao, X.; Rizo, J.; Südhof, T.C. The evolutionary pressure to inactivate: A subclass of Synaptotagmins with an amino acid substitution that abolishes Ca2+ binding. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 14314–14319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Minami, A.; Uemura, M. Calcium-dependent freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis involves membrane resealing via synaptotagmin SYT1. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 3389–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Saheki, Y.; De Camilli, P. Ca(2+) releases E-Syt1 autoinhibition to couple ER-plasma membrane tethering with lipid transport. Embo J 2018, 37, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davletov, B.A.; Südhof, T.C. A single C2 domain from synaptotagmin I is sufficient for high affinity Ca2+/phospholipid binding. J Biol Chem 1993, 268, 26386–26390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruget, C.; Bello, O.; Coleman, J.; Krishnakumar, S.S.; Perez, E.; Rothman, J.E.; Pincet, F.; Donaldson, S.H. Synaptotagmin-1 membrane binding is driven by the C2B domain and assisted cooperatively by the C2A domain. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 18011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, J.A.; Messa, M.; Sun, E.W.; Wheeler, H.; Torta, F.; Wenk, M.R.; De Camilli, P.; Reinisch, K.M. Lipid transport by TMEM24 at ER-plasma membrane contacts regulates pulsatile insulin secretion. Science 2017, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottekat, A.; Becker, S.; Spencer, K.R.; Yates, J.R.; Manning, G.; Itkin-Ansari, P.; Balch, W.E. Insulin Biosynthetic Interaction Network Component, TMEM24, Facilitates Insulin Reserve Pool Release. Cell Reports 2013, 4, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.W.; Guillén-Samander, A.; Bian, X.; Wu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Messa, M.; De Camilli, P. Lipid transporter TMEM24/C2CD2L is a Ca(2+)-regulated component of ER-plasma membrane contacts in mammalian neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 5775–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Panagiotou, S.; Cen, J.; Gilon, P.; Bergsten, P.; Idevall-Hagren, O. The endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane tethering protein TMEM24 is a regulator of cellular Ca2+ homeostasis. J Cell Sci 2021, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huercano, C.; Percio, F.; Sanchez-Vera, V.; Morello-López, J.; Botella, M.A.; Ruiz-Lopez, N. Identification of plant exclusive lipid transfer SMP proteins at membrane contact sites in Arabidopsis and Tomato. bioRxiv 2012, 2022.2012.2014.520452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Santana, B.V.N.; Samuels, E.; Benitez-Fuente, F.; Corsi, E.; Botella, M.A.; Perez-Sancho, J.; Vanneste, S.; Friml, J.; Macho, A.; et al. Rare earth elements induce cytoskeleton-dependent and PI4P-associated rearrangement of SYT1/SYT5 endoplasmic reticulum–plasma membrane contact site complexes in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 71, 3986–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craxton, M. Evolutionary genomics of plant genes encoding N-terminal-TM-C2 domain proteins and the similar FAM62 genes and synaptotagmin genes of metazoans. BMC Genomics 2007, 8, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Vanneste, S.; Pérez-Sancho, J.; Benitez-Fuente, F.; Strelau, M.; Macho, A.P.; Botella, M.A.; Friml, J.; Rosado, A. Ionic stress enhances ER-PM connectivity via phosphoinositide-associated SYT1 contact site expansion in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 1420–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hernández, S.; Rubio, L.; Pérez-Sancho, J.; Esteban del Valle, A.; Benítez-Fuente, F.; Beuzón, C.R.; Macho, A.P.; Ruiz-López, N.; Albert, A.; Botella, M.A. Unravelling Different Biological Roles Of Plant Synaptotagmins. bioRxiv 2001, 2024.2001.2021.576508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Krausko, M.; Jásik, J. SYNAPTOTAGMIN 4 is expressed mainly in the phloem and participates in abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Han, S.; Siao, W.; Song, C.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, X.; Cheng, P.; Li, H.; Jásik, J.; Mičieta, K.; et al. Arabidopsis Synaptotagmin 2 Participates in Pollen Germination and Tube Growth and Is Delivered to Plasma Membrane via Conventional Secretion. Molecular Plant 2015, 8, 1737–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, B.; Fan, H.; Jin, J.; Botella, M.A.; Jiang, L.; Lin, J. Golgi Apparatus-Localized Synaptotagmin 2 Is Required for Unconventional Secretion in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.; Neu, C.; Pajonk, S.; Yun, H.S.; Lipka, U.; Humphry, M.; Bau, S.; Straus, M.; Kwaaitaal, M.; Rampelt, H.; et al. Co-option of a default secretory pathway for plant immune responses. Nature 2008, 451, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, D.G.; Jiang, J.; Movahed, N.; Germain, H.; Yamaji, Y.; Zheng, H.; Laliberté, J.F. Turnip Mosaic Virus Uses the SNARE Protein VTI11 in an Unconventional Route for Replication Vesicle Trafficking. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 2594–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siao, W.; Wang, P.; Voigt, B.; Hussey, P.J.; Baluska, F. Arabidopsis SYT1 maintains stability of cortical endoplasmic reticulum networks and VAP27-1-enriched endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites. J Exp Bot 2016, 67, 6161–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutz, C.E.; Snyder, S.L.; Schulz, T.A. Characterization of the yeast tricalbins: Membrane-bound multi-C2-domain proteins that form complexes involved in membrane trafficking. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS 2004, 61, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, J.M.; Richardson, R.A.; McLoughlin, F.; Vierstra, R.D.; Haswell, E.S. Unbiased proteomic and forward genetic screens reveal that mechanosensitive ion channel MSL10 functions at ER–plasma membrane contact sites in Arabidopsis thaliana. eLife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, D.; Haswell, E.S. The Mechanosensitive Ion Channel MSL10 Potentiates Responses to Cell Swelling in Arabidopsis Seedlings. Current Biology 2020, 30, 2716–2728.e2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, F.; Zhou, M.; Huang, X.; Fan, J.; Wei, L.; Boulanger, J.; Liu, Z.; Salamero, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. E-syt1 Re-arranges STIM1 Clusters to Stabilize Ring-shaped ER-PM Contact Sites and Accelerate Ca(2+) Store Replenishment. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, T.; Li, C.; Liu, F.; Xu, K.; Wan, C.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H. Arabidopsis synaptotagmin 1 mediates lipid transport in a lipid composition-dependent manner. Traffic 2022, 23, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, K.; Oparka, K. Imaging plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 2011, 248, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, E.M.; Benitez-Alfonso, Y. Plasmodesmata: Channels Under Pressure. Annual Review of Plant Biology 75, 291-317.

- Robertson, J.D.; Locke, M. Cellular membranes in development. by M. Locke, Academic Press, Inc., New York 1964, 1.

- Brault, M.L.; Petit, J.D.; Immel, F.; Nicolas, W.J.; Glavier, M.; Brocard, L.; Gaston, A.; Fouché, M.; Hawkins, T.J.; Crowet, J.M.; et al. Multiple C2 domains and transmembrane region proteins (MCTPs) tether membranes at plasmodesmata. EMBO reports 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriechbaumer, V.; Botchway, S.W.; Slade, S.E.; Knox, K.; Frigerio, L.; Oparka, K.; Hawes, C. Reticulomics: Protein-Protein Interaction Studies with Two Plasmodesmata-Localized Reticulon Family Proteins Identify Binding Partners Enriched at Plasmodesmata, Endoplasmic Reticulum, and the Plasma Membrane. Plant Physiol 2015, 169, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, K.; Kwon, C.; Yun, H.S. Synaptotagmin 4 and 5 additively contribute to Arabidopsis immunity to Pseudomonas syringae DC3000. Plant Signal Behav 2022, 17, 2025323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensing, S.A.; Goffinet, B.; Meyberg, R.; Wu, S.-Z.; Bezanilla, M. The Moss Physcomitrium (Physcomitrella) patens: A Model Organism for Non-Seed Plants. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 1361–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menand, B.; Calder, G.; Dolan, L. Both chloronemal and caulonemal cells expand by tip growth in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Journal of Experimental Botany 2007, 58, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.; Dolan, L. Auxin promotes the transition from chloronema to caulonema in moss protonema by positively regulating PpRSL1and PpRSL2 in Physcomitrella patens. New Phytol. 2011, 192, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelander, M.; Landberg, K.; Sundberg, E. Auxin-mediated developmental control in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Journal of Experimental Botany 2018, 69, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntefidou, M.; Eklund, D.M.; Le Bail, A.; Schulmeister, S.; Scherbel, F.; Brandl, L.; Dörfler, W.; Eichstädt, C.; Bannmüller, A.; Ljung, K.; et al. Physcomitrium patens PpRIC, an ancestral CRIB-domain ROP effector, inhibits auxin-induced differentiation of apical initial cells. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, doi.org–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, R.; Moody, L.A. A fundamental developmental transition in Physcomitrium patens is regulated by evolutionarily conserved mechanisms. Evol. Devel. 2021, 23, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thelander, M.; Olsson, T.; Ronne, H. Effect of the energy supply on filamentous growth and development in Physcomitrella patens. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumaker, K.S.; Dietrich, M.A. Programmed Changes in Form during Moss Development. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, Y.; Ohtsuka, J.; Hiwatashi, Y.; Naramoto, S.; Kyozuka, J. Cytokinin and ALOG proteins regulate pluripotent stem cell identity in the moss Physcomitrium patens. Science Advances 2024, 10, eadq6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, P.; Reski, R.; Maldiney, R.; Laloue, M.; Schwartzenberg, K.v. Kinetics of Cytokinin Production and Bud Formation in Physcomitrella: Analysis of Wild Type, a Developmental Mutant and Two of Its ipt Transgenics. Journal of Plant Physiology 2000, 156, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, L.A.; Kelly, S.; Rabbinowitsch, E.; Langdale, J.A. Genetic Regulation of the 2D to 3D Growth Transition in the Moss Physcomitrella patens. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 473–478.e475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, V.A.S.; Dolan, L. The evolution of root hairs and rhizoids. Annals of Botany 2012, 110, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.; Zhao, S.; Yao, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M.; Sun, Y.; Hou, X.; Haas, F.B.; Varshney, D.; Prigge, M.; et al. Near telomere-to-telomere genome of the model plant Physcomitrium patens. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunkard, J.O.; Zambryski, P.C. Plasmodesmata enable multicellularity: New insights into their evolution, biogenesis, and functions in development and immunity. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2017, 35, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, M.E.; Graham, L.E.; Botha, C.E.J.; Lavin, C.A. Comparative ultrastructure of plasmodesmata of Chara and selected bryophytes: Toward an elucidation of the evolutionary origin of plant plasmodesmata. American Journal of Botany 1997, 84, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegner, L.; Ehlers, K. Plasmodesmata dynamics in bryophyte model organisms: Secondary formation and developmental modifications of structure and function. Planta 2024, 260, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, T.; Thelander, M.; Ronne, H. A Novel Type of Chloroplast Stromal Hexokinase Is the Major Glucose-phosphorylating Enzyme in the Moss Physcomitrella patens. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 44439–44447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensing, S.A.; Lang, D.; Zimmer, A.D.; Terry, A.; Salamov, A.; Shapiro, H.; Nishiyama, T.; Perroud, P.-F.O.; Lindquist, E.A.; Kamisugi, Y.; et al. The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science 2008, 319, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, M.; Rensing, S.A.; Gould, S.B. The greening ashore. Trends in Plant Science 2022, 27, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, K.; Maruyama, F.; Fujisawa, T.; Togashi, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Seo, M.; Sato, S.; Yamada, T.; Mori, H.; Tajima, N.; et al. Klebsormidium flaccidum genome reveals primary factors for plant terrestrial adaptation. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol 1981, 17, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, D.M.; Shu, S.; Howson, R.; Neupane, R.; Hayes, R.D.; Fazo, J.; Mitros, T.; Dirks, W.; Hellsten, U.; Putnam, N.; et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1178–D1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schliep, K.P. phangorn: Phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Project, I. Inkscape. 2020.

- Blum, M.; Andreeva, A.; Florentino, L.C.; Chuguransky, S.R.; Grego, T.; Hobbs, E.; Pinto, B.L.; Orr, A.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Ponamareva, I.; et al. InterPro: The protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53, D444–D456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, gkae1010. [CrossRef]

- Berardini, T.Z.; Reiser, L.; Li, D.; Mezheritsky, Y.; Muller, R.; Strait, E.; Huala, E. The arabidopsis information resource: Making and mining the “gold standard” annotated reference plant genome. genesis 2015, 53, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, A.L.; Piatkowski, B.; Lovell, J.T.; Sreedasyam, A.; Carey, S.B.; Mamidi, S.; Shu, S.; Plott, C.; Jenkins, J.; Lawrence, T.; et al. Newly identified sex chromosomes in the Sphagnum (peat moss) genome alter carbon sequestration and ecosystem dynamics. Nature Plants 2023, 9, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.L.; Kohchi, T.; Yamato, K.T.; Jenkins, J.; Shu, S.; Ishizaki, K.; Yamaoka, S.; Nishihama, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Berger, F.; et al. Insights into Land Plant Evolution Garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha Genome. Cell 2017, 171, 287–304.e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, J.; Tsirigos, K.; Pedersen, M.D.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Marcatili, P.; Nielsen, H.; Krogh, A.; Winther, O. DeepTMHMM predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenhofer, U.; Bonatesta, E.; Horejš-Kainrath, C.; Hochreiter, S. msa: An R package for multiple sequence alignment. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3997–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henikoff, S.; Henikoff, J.G. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1992, 89, 10915–10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G. Data Integration, Manipulation and Visualization of Phylogenetic Trees; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Feng, T.; Xu, S.; Gao, F.; Lam, T.T.; Wang, Q.; Wu, T.; Huang, H.; Zhan, L.; Li, L.; et al. ggmsa: A visual exploration tool for multiple sequence alignment and associated data. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23, bbac222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charif, D.; Lobry, J.R. Structural Approaches to Sequence Evolution: Molecules, Networks, Populations; Bastolla, U., Porto, M., Roman, H.E., Vendruscolo, M., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 2007.

- Jones, D.T.; Taylor, W.R.; Thornton, J.M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci 1992, 8, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Class V | Class VI | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. thaliana | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| M. polymorpha | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 91 |

| S. fallax | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 15 |

| P. patens | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).