1. Introduction

Ferns and lycophytes represent a genetic legacy of great value, being descendants of the first plants that evolved vascular tissues about 470 million years ago. Compared to angiosperms, they have received scant attention, relegating them to the background after a splendid past. The aesthetic appeal of their leaves and using them to alleviate ailments in traditional medicine is all that these plant groups have traditionally inspired. Only a handful of species have been used to delve into basic developmental processes, such as photomorphogenesis (1), spore germination (2–4), cell polarity (5), cell wall composition (6), or reproduction. These studies focused on the gametophyte generation, an autonomously growing organism, well-suited for in vitro culture and sample collection (7–8). Although the gametophytes of ferns possess a very simple structure consisting of one cell layer, they display some degree of complexity: apical-basal polarity, dorsoventral asymmetry, rhizoids, meristems in the apical or lateral parts, reproductive organs (male antheridia and female archegonia), and trichomes distributed over the entire surface.

From a metabolic point of view, ferns and lycophytes contain many secondary metabolites: flavonoids, alkaloids, phenols, steroids, etc., and exhibit various bioactivities such as antibacterial, antidiabetic, anticancer, antioxidant, etc. (9). The therapeutic use of both plant groups is changing, from its use in the traditional medicine of different peoples to current applications, in which these plants are used to generate nanoparticles (10). Finally, the use of ferns and lycophytes was recently advocated to address problems caused by biotic and abiotic stresses. Drought is one of the most severe abiotic stresses affecting plant growth and productivity, and fern and lycophytes could contribute to managing it (11). Other important adaptations of ferns to extreme environments, such as salinity, heavy metals, epiphytes, or a low invasion of its habitats were summarized by Rathinasabapathi (12). Likewise, Dir (13) highlights the high efficiency of many species of aquatic and terrestrial ferns in extracting various organic and inorganic pollutants from the environment.

Increasingly, researchers have become more interested in these plants, made possible by the advent of high-throughput technologies, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, providing greater knowledge of the functions encoded by their elusive genomes. Changes in gene expression, induced by either environmental or developmental conditions, can now be examined in non-model organisms because the required techniques have become more affordable as automation and efficiency have reduced costs. To date, some transcriptomic and proteomic datasets have been published for ferns, e.g., Pteridium aquilinum (14), Ceratopteris richardii (5,15), Blechnum spicant (16), Lygodium japonicum (17), Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis (18–20), and Dryopteris oreades (20,21). For the last species, both transcriptomic and proteomic analyses were performed by RNA-sequencing and shotgun proteomics by tandem mass spectrometry.

This work expands our knowledge of proteomic data in non-seed plants, which is far less explored than in seed plants. We present a continuation of previous work (21), in which proteins of heart-shaped gametophytes from two ferns, the apomictic species D. affinis spp. affinis (referred to as D. affinis hereafter) and its sexual relative D. oreades, were extracted and identified using a species-specific transcriptome database established in a previous project (18,19). The functional annotation was inferred by blasting identified full length protein sequences. We report the categorization of proteins that are shared by both sexual and apomictic gametophytes. Specifically, our analysis reveals new proteomic information involved in the metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids, the biosynthesis of amino acids, the metabolism of nucleotides and energy, as well as of secondary compounds, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, lignans, etc., important in plant defence against stress. In addition to oxide-reductive processes, it also reveals proteins related to transcription, translation, as well as protein folding, sorting, transport, and degradation.

2. Results

To gain insights into their biological functions, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) classifications provided by the STRING platform were analyzed (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Based on GO classification, most of the identified proteins are involved in biological functions linked to the primary metabolism, and more specifically to other cellular processes, such as response to stimulus, protein degradation, translation, etc.

In turn, KEGG classification revealed that common proteins are mostly associated with the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, the ribosome, and the biosynthesis of amino acids. These processes include the building of cellular organelles such as ribosomes (

Figure 3) or proteasomes (

Figure 4). Related to ribosomes, there were several protein classes, such as nucleic acid-binding proteins, ribosomal proteins, translation elongation factors, etc. On the other hand, proteasomes mediate the degradation of proteins, and we found proteins of 20S particle, the proteolytic core, but also regulatory factors.

Protein domains that are abundant in the gametophytes of both ferns were the pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component and the histidine and lysine active sites of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, which is involved in carbohydrate metabolism. Regarding the biosynthesis of amino acids, the most abundant domains were aspartate aminotransferase and pyridoxal phosphate-dependent transferase. Among proteins involved in the metabolism of energy, the HAS barrel domain and the F1 complex of the alpha and beta subunits of ATP synthase were abundant. Related to the metabolism of secondary compounds, aromatic amino acid lyase, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, and the N-terminus of histidase were enriched. Finally, the frequently found domains in proteins involved in transcription and translation were the GTP-binding domain and domain 2 of elongation factor Tu as well as conserved sites of the ribosomal proteins S10 and S4.

The interactome of the proteins common to

D. affinis and

D. oreades represented a network composed of 218 nodes and 1,792 interactions (p-value < 1 x e-16). The proteins with the highest number of interactions among the identified proteins are shown in

Table 1, i.e., SUPPRESSOR OF ACAULIS 56 (SAC56), RIBOSOMAL PROTEIN US11X (US11X), and RIBOSOMAL PROTEIN US17Y (US17Y), each having 44 interactions.

The strength of the interactions can be weak or strong (

Table S1) based on a scale from 0 to 1, where a weak interaction will have a score close to 0 and a strong one a score close to 1. Taking into account only interactions with a score equal to or greater than 0.99 foreach group of proteins studied, proteins involved in transcription and translation are those with the highest number of interactions (554), followed by proteins involved in energy (29), carbohydrate metabolism (16), and finally biosynthesis of amino acids (5), and transport (3). According to the STRING software, the evidence of interactions between proteins can be of various types: (a) Experiments: these refer to proteins that have been shown to have chemical, physical, or genetic interaction in laboratory experiments; (b) Databases: describes interactions of proteins found in the same databases; (c) Textmining: the proteins are mentioned in the same PubMed abstract or the same article of an internal selection of the STRING software; (d) Co-expression: indicates that the gene expression patterns of the two proteins are similar; (e) Neighbourhood: the genes encoding the proteins are close to each other in the genome; (f) Gene fusion: indicates that at least in one organism the orthologous genes encoding the two proteins are fused into a single gene; and (g) Co-occurrence: refers to proteins that have a similar phylogenetic distribution. Next, we consider some of these type of interaction between proteins (

Figure 5): text mining, experiments, co-expression, and databases.

Specifically, we analyzed the groups metabolism of carbohydrates (

Figure 5a), metabolism of energy (

Figure 5b), ribogenesis (

Figure 5c), and protein degradation (

Figure 5d). Paying attention only to the two main types of evidence for each of these groups, their relationships were analyzed (

Figure 6). Evidence from databases and text mining were the most relevant for metabolism of carbohydrates (

Figure 6a), biosynthesis of amino acids (

Figure 6b), the metabolism of secondary compounds, and transport; textmining and co-expression data for the metabolism of energy (

Figure 6c), and experiments and co-expression data for transcription and translation (

Figure 6d). The associations between variables statistically were as follows: in metabolism of carbohydrates and in transcription and translation highly significant in both (p-value < 0.001), in biosynthesis of amino acids no significant (p-value > 0.05), and in metabolism of energy marginally significant (p-value slightly greater than 0.05).

Alternatively, when comparing the same type of evidence among the different groups of proteins, we observed that the neighborhood interaction was the most important for biosynthesis of amino acids and transcription and translation; gene fusion for metabolism of carbohydrates and biosynthesis of amino acids; co-occurrence for biosynthesis of amino acids and metabolism of secondary compounds; co-expression for metabolism of energy and transcription and translation; experiments for transcription and translation, and transport; evidence from databases for metabolism of carbohydrates and transport; and, finally, textmining for metabolism of secondary compounds and transport.

3. Discussion

The current work provides novel information on the proteome shared by gametophytes of the apomictic fern

D. affinis and its sexual relative

D. oreades, and provides continuity to previous studies in these species (18–21). Specifically, for ease of discussion of biological functions and interaction, the proteins discussed here after were grouped into two major categories: metabolism and genetic information processing (

Table 2).

3.1. Metabolism

Metabolism comprises two main branches: primary and secondary. Primary metabolism concerns essential metabolites that are directly involved in plant growth (carbohydrates, lipids, amino acids, nucleotides), as well as those reactions that fuel their biosynthesis, such as photosynthesis, glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle, etc. In plants, there is also an important secondary metabolism, which concerns non-essential metabolic routes that govern, for instance, defence and stress responses.

Citrate/tricarboxylic acid cycle

Likewise, we identified some proteins associated with the citrate/tricarboxylic acid cycle: AT2G20420 and AT5G08300, involved in the only phosphorylation step at the substrate level of this cycle. Another protein we identified is the cytosolic MALATE DEHYDROGENASE 1 (c-NAD-MDH1), which catalyses a reversible NAD-dependent dehydrogenase reaction involved in central metabolism and redox homeostasis between organelle compartments (24).

Pentose phosphate pathway

In parallel to glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway generates NADPH and pentoses. This metabolic pathway is represented in our dataset by the proteins 6-PHOSPHOGLUCONATE DEHYDROGENASE 1 (PGD1), GLUCOSE-6-PHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE 6 (G6PD6), and PGK1. A mutation in the gene of the first protein may decrease cellulose synthesis, thus altering the structure and composition of the primary cell wall (25). G6PD6 is important for the synthesis of fatty acids and nucleic acids involved in membrane synthesis and cell division (26). PGK1 contributes to trigger the phosphorylation of the proteins FTSZ2-1 and FTSZ2-2, required for chloroplast division (27).

Starch

Starch is the main reserve form of carbohydrates and energy in plants, being accumulated in chloroplasts during the day, and transported and degraded to provide energy and nutritional substances for growth and metabolism. Gametophytes of D. affinis and D. oreades produce proteins involved in its synthesis, including STARCH BRANCHING ENZYME 2.2 (SBE2.2) and GRANULE-BOUND STARCH SYNTHASE 1 (GBSS1), the latter, together with STARCH DIRECTED PROTEIN (PTST), required for amylose synthesis (28).

Biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars

Apart from to the proteins mentioned above, we found some that are associated with the biosynthesis of nucleotide sugars, such as two pyrophosphorylases (ADG1 and APL1); the protein REVERSIBLY GLYCOSYLATED POLYPEPTIDE 4 (RGP4), involved in the synthesis of non-cellulosic polysaccharides of the cell wall (29); and AT5G20080.

Biosynthesis of amino acids

Involved in the biosynthesis of amino acids, we found the proteins aminotransferase ASP1; the ISOPROPYL MALATE ISOMERASE LARGE SUBUNIT 1 (IIL1), which acts in glucosinolate biosynthesis involved in the defence against insects (34); GLUTAMATE SYNTHASE 1 (GLU1), required for the re-assimilation of ammonium ions generated during photorespiration (35); and SERINE HYDROXYMETHYLTRANSFERASE 3 (SHM3), HISTIDINOL DEHYDROGENASE (HDH), and METHIONINE OVER-ACCUMULATOR3 (MTO3), which catalyse the formation of glycine, L-histidine, and methionine, respectively (36–38).

3.2. Genetic Information Processing

Transcription and translation

The processing of genetic information comprises transcription, translation, and protein folding, sorting or transport, and degradation. In the gametophytes of D. affinis and D. oreades, we identified two proteins involved in transcription, specifically the 14-3-3-like proteins: GF14 nu (GRF7) and GF14 iota (GRF12), which are associated with a DNA-binding complex that binds to the G-box, a cis-regulatory DNA element (58). Related to translation, we found: RNA-BINDING GLYCINE-RICH PROTEIN A7 (RBGA7), which has a role in RNA processing during stress, specifically in editing cytosine to uracil in mitochondrial RNA and thus controlling 6% of all mitochondrial editing sites (59); and others, such as AT1G03510; RNA-BINDING PROTEIN 47B (RBP47B); and UBP1-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 2A (UBA2A), which regulates mRNA and stabilizes RNA in the nucleus (60). Apart from several ribosomal subunits, there were others involved in elongation, like the protein LOW EXPRESSION OF OSMOTICALLY RESPONSIVE GENES1 (LOS1), which is also involved in the response to cold (61).

Protein folding and sorting

Once the proteins have been formed, there is a quality check to ensure that they have been synthesized completely folded correctly. Among the proteins playing a major role in the acceleration of folding or the degradation of misfolded proteins are GROES, AT3G10060, AT2G43560, AT2G21130, etc. The gametophyte of the ferns under study harbour proteins linked to the sorting or transport of molecules within the cell and between the inside and outside of cells. In line with this, we found ALBINO OR GLASSY YELLOW1 (AGY1), which has a role in coupling ATP hydrolysis to protein transfer across the thylakoid membrane, thus participating in photosynthetic acclimation and chloroplast formation (62); RAN BINDING PROTEIN 1(RANBP1), moving proteins into the nucleus (63); IMPORTIN ALPHA ISOFORM 2 (IMPA-2), acting in nuclear import (64); and the proteins ADP/ATP CARRIER 2 (AAC2), mediating the import of ADP into the mitochondrial matrix (65), and TRANSLOCON AT THE INNER ENVELOPE MEMBRANE OF CHLOROPLASTS 62 (Tic62), involved in the import of nuclear-encoded proteins into chloroplasts (66). In addition, we found proteins associated with the transport of water and small hydrophilic molecules through the cell membrane: PLASMA MEMBRANE INTRINSIC PROTEIN 1;4 (PIP1;4) (67); and VOLTAGE-DEPENDENT ANION CHANNEL 3 (VDAC3) (68). There were also proteins with dilysine motifs and associated with clathrin-uncoated vesicles that are transported from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus and vice versa: ALPHA1 COAT PROTEIN (alpha1-COP), GAMMA2 COAT PROTEIN (gamma2-COP), and AT5G05010. In contrast, the proteins EPSIN2 (EPS2) and DYNAMIN-LIKE 3 (DL3) are related to clathrin-coated vesicles, the latter participating in planar polarity formation to correctly position the root hairs (69). Reviewing our proteomic profiles, we found GUANOSINE NUCLEOTIDE DIPHOSPHATE DISSOCIATION INHIBITOR 1 (GDI1), which regulates the GDP/GTP exchange reaction of most RAB proteins by inhibiting GDP dissociation and subsequent GTP binding (70).

Protein degradation

On the other hand, many proteins we found are related to protein catabolism or degradation, being subunits of proteasomes, i.e., complexes characterized by their ability to degrade polyubiquitinylated proteins. Others, such as AT1G09130; CLP PROTEASE PROTEOLYTIC SUBUNIT 2 (CLP2); CLP PROTEASE R SUBUNIT 4 (CLPR4); LON PROTEASE 1 (LON1); PRESEQUENCE PROTEASE 1 (PREP1), which degrades, in mitochondria, the pre-sequences of proteins that have been cut off after import, in order to prevent their export back to the cytoplasm, which is inefficient and energy-costly (71); and also DEGRADATION OF PERIPLASMIC PROTEINS 9 (DEG9), which degrades the A. thaliana RESPONSE REGULATOR 4 (ARR4), a regulator that participates in light and cytokinin signalling by modulating the activity of Phytochrome B (72). Plants have to cope with heat stress, and for this, the gametophytes studied here rely on the aminopeptidases LEUCYL AMINOPEPTIDASE 1 and 3 (LAP1 and LAP3), which are probably involved in the processing and turnover of intracellular proteins, and function as molecular chaperones protecting proteins from heat-induced damage (73).

3.3. Protein-Protein Interactions

Using the STRING platform, we thoroughly analyzed - one by one - the interactions of the groups of proteins studied. We observed that for metabolism of carbohydrates, evidence from co-expression, textmining, and experiments were stronger between the proteins AT2G20420 and AT5G08300, and evidence from databases between AT2G20420 and E2-OGDH1. AT2G20420 and AT5G08300 are both mitochondrial succinate-coA ligase subunits, and E2-OGDH1 catalyses the conversion of 2-oxoglutarate to succinyl-CoA and CO2, i.e., the three proteins are involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (74). Among the proteins for biosynthesis of amino acids, evidence from co-expression was stronger between the proteins AT1G14810 and DIHYDROXYACID DEHYDRATASE (DHAD); while evidence from databases was stronger between DHAD and 2-ISOPROPYLMALATE SYNTHASE 1 (IMS1), IIL1 and IMS1, and IIL1 and ISOPROPYLMALATE DEHYDROGENASE 2 (IMD2). In fact, these proteins are involved in the synthesis of numerous compounds necessary for plant growth and development: AT1G14810 for the biosynthesis of lysine, threonine, and methionine (75); DHAD for isoleucine and valine (76); IMS1 and IMD2 for leucine (77,78); and IIL1 for glucosinolates (34). For metabolism of energy, evidence from co-expression was stronger between the proteins ATPC1 and GLYCERALDEHYDE 3-PHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE A SUBUNIT 2 (GAPA-2), and DRT112 and FED A; while experiments provided strong evidence for the interaction between PSAA and PSAC. In photosynthesis, the C-terminus of PSAC interacts with PSAA and other proteins, such as PSAB and PSAD for its assembly into photosystem I (79). Evidence from databases indicated the interaction between AGT and GLYCOLATE OXIDASE 2 (GOX2), both proteins being involved in photorespiration (46); while evidence from textmining suggested an interaction between PSBO2 and PHOTOSYSTEM II SUBUNIT P-1 (PSBP-1), both being chloroplastic oxygen-evolving enhancers that form part of photosystem II (41).

For metabolism of secondary compounds, evidence from textmining was the strongest, indicating an interaction between PHE AMMONIA LYASE 1 (PAL1) and PHENYLALANINE AMMONIA-LYASE 4 (PAL4). Both proteins participate in the synthesis from phenylalanine of numerous compounds based on the phenylpropane skeleton, necessary for the plant’s metabolism (80). With respect to transcription and translation, co-expression evidence was stronger between ribosomal proteins, such as EL34Z and UL22Z, RPL23AB, UL11Z, EL14Z, and RPL18, among a long list of proteins forming ribosomes. Finally, for protein transport, co-expression data provided the strongest evidence for interactions between the proteins alpha1-COP and gamma2-COP; experiments for the interaction between alpha1-COP and AT5G05010; and textmining for that between AGY1 and GET3B.

As indicated in the results, in the group related to metabolism of carbohydrates, the proteins with the most interactions were ENOC and PGK1, both involved in glycolysis (81). For biosynthesis of amino acids, it was AT1G14810, which is involved in several biosynthetic pathways: lysine, isoleucine, methionine, and threonine (77). In the group metabolism of energy, ATPC1 had the highest number of interactions, likely because it is part of a chloroplastic ATP synthase (82). The protein 4CL3 had the most interactions in the group metabolism of secondary compounds. It plays a key role in the synthesis of numerous secondary metabolites, such as anthocyanins, flavonoids, isoflavonoids, coumarins, lignin, suberin, and phenols (53). In transcription and translation, the ribosomal proteins SAC56, US11X, and US17Y, necessary for the formation of ribosomes, had the highest number of interactions (83). Finally, in transport, RAB1A held to top rank; it participates in intracellular vesicle trafficking and protein transport (84).

Regarding the statistical analysis of the two highest types of interactions in the studied groups of metabolism of carbohydrates (database and textmining) and transcription and translation (experiments and co-expression), the Person’s correlation coefficients, which measure the tendency of two vectors to increase or decrease together, were significant, being the pairwise interactions increased. One of the most popular types of data in databases is text, and the process of synthesizing information is known as text mining. In the case of proteins linked to the carbohydrates metabolism, it seems to have a lot of information in databases about it, and therefore textmining could be enriched as well. In the second case, we speculate that in the experiments carried out on transcription and translation processes, depending on the methodology employed, might be that more genes could be expressed at the same time.

These data on the interactions between the studied proteins and the evidence supporting it sheds new light onto the proteome shared the ferns D. affinis and D. oreades. Together with the description of the possible biological functions associated with these proteins and their interactions, this study significantly expands the scarce information on the development and functioning of fern gametophytes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Spores of D. affinis were obtained from sporophytes growing in Turón valley (Asturias, Spain), 477m a.s.l., 43º 12′ 10 N−5º 43′ 43′’ W. For D. oreades, spores were collected from sporophytes growing in Neila lagoons (Burgos, Spain), 1.920 m a.s.l., 42º 02′ 48N−3º 03′ 44′’ W. Spores were released from sporangia, soaked in water for 2 h, and then washed for 10 min with a solution of NaClO (0.5%) and Tween 20 (0.1%). Then, they were rinsed three times with sterile, distilled water. Spores were centrifuged at 1,300 g for 3 min between rinses and then cultured in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of liquid Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (85). Unless otherwise noted, media were supplemented with 2% sucrose (w/v), and the pH was adjusted to 5.7 with 1 or 0.1 N NaOH. The cultures were kept on an orbital shaker (75 rpm) at 25 ºC under cool-white fluorescent light (70 µmol m-2s-1) with a 16 h photoperiod.

Following spore germination, filamentous gametophytes were subcultured into 200 mL flasks containing 25 mL of MS medium supplemented with 2% sucrose (w/v) and 0.7% agar. The gametophytes of

D. affinis became two-dimensional, arriving at the spatulate and heart stage after 20 or 30 additional days, respectively. Gametophytes of

D. oreades grew slower and needed around six months to become cordate and reach sexual maturity (

Figure 7). Apomictic and sexual gametophytes were collected, and images were taken under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse E600), using microphotographic equipment (DS Camera Control, Nikon). Gametophytes of

D. oreades had only female reproductive organs (i.e., archegonia), while cordate gametophytes of

D. affinis had visible developing apogamic centers, composed of smaller and darker isodiametric cells. Samples of apomictic and sexual cordate gametophytes were weighed before and after lyophilization for 48h (Telstar-Cryodos) and stored in Eppendorf tubes in a freezer at -20 ºC until use.

4.2. Protein Extraction, Separation, and In-Gel Digestion

From the cordate apomictic and sexual gametophytes (three samples each), an amount of 20 mg dry weight was homogenized using a Silamat S5 shaker (IvoclarVivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein). The protocol used for protein extraction, separation, and in-gel digestion was reported earlier (20). Samples were solubilized with 800 μL of buffer A [0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA, 0.1 MHEPES-KOH, 4 mM DTT, 15 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 0.5% (w/v) PVP, and 1 xprotease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland)], and homogenized using a Potter homogenizer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Proteins were extracted in two steps: first, the homogenate was subjected to centrifugation at 16,200g for 10 min at 4 ºC on a tabletop centrifuge and, second, the supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 117–124 kPa (100,000g) for 45 min at 4 ºC in an Airfuge (Beckman Coulter, Pasadena, CA, USA), yielding the soluble protein fraction in the supernatant. In parallel, the pellet obtained from the first ultracentrifugation was re-dissolved in 200 μL of buffer B [40 mM Tris-base, 40 mM DTT, 4% (w/v) SDS, 1 xprotease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland)] to extract membrane proteins using the ultracentrifuge as described above, in the supernatant. Protein concentrations were determined using a Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The 1D gel electrophoresis was performed as follows: 1 mg protein per each soluble and membrane fraction was treated with sample loading buffer and 2 M DTT, heated at 99 ºC for 5 min, followed by a short cooling period on ice, and then loaded separately onto a 0.75 mm tick, 12% SDS-PAGE mini-gel. Electrophoresis conditions were 150 V and 250 mA for 1 h in 1xrunning buffer.

4.3. Protein Separation and In-Gel Digestion

Each gel lane was cut into six 0.4 cm wide sections resulting in 48 slices, then fragmented into smaller pieces and subjected to 10 mM DTT (in 25 mM AmBic, pH8) for 45 min at 56 ºC and 50 mM iodoacetamide for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, prior to trypsin digestion at 37 ºC overnight. Subsequently, gel pieces were washed twice with 100 μL of 100 mM NH4HCO3/50% acetonitrile and washed once with 50μL acetonitrile. At this point, the supernatants were discarded. Peptides were digested with 20μL trypsin (5 ng/L in 10 mM Tris/2 mM CaCl2, pH 8.2) and 50μL buffer (10 mM Tris/2 mM CaCl2, pH 8.2). After microwave-heating for 30 min at 60 ºC, the supernatant was removed, and gel pieces were extracted once with 150 μL 0.1% TFA/50% acetonitrile. All supernatants were put together, then dried and dissolved in 15μL 0.1% formic acid/3% acetonitrile, and finally transferred to auto-sampler vials for liquid chromatography (LC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) for which 5 μL was injected.

4.4. Protein Identification, Verification, and Bioinformatic Downstream Analyses

MS/MS and peptide identification (Orbitrap XL) were performed according to (18). Scaffold software (version Scaffold 4.2.1, Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR) was used to validate MS/MS-based peptide and protein identifications. Mascot results were analyzed together using the MudPIT option. Peptide identifications were accepted if they scored better than 95.0% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm with delta mass correction, and protein identifications were accepted if the Protein Prophet probability was above 95%. Proteins that contained the same peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony using the scaffolds cluster analysis option. Only proteins that met the above criteria were considered as positively identified for further analysis. The number of random matches was evaluated by performing the Mascot searches against a database containing decoy entries and checking how many decoy entries (proteins or peptides) passed the applied quality filters. The peptide FDR and protein FDR was estimated at 2 and 1%, respectively, indicating the stringency of the analyses. A semi-quantitative spectrum counting analysis was conducted. The “total spectrum count” for each protein and each sample was reported, and these spectrum counts were averaged for each species, D. affinis and D. oreades. Then, one “1” was added to each average in order to prevent division by zero and a log2-ratio of the averaged spectral counts from D. affinis versus D. oreades was calculated. Proteins were considered as differentially expressed if this log2-ratio was above 0.99. This refers to at least twice as much peptide spectrum match (PSM) assignments in one group compared to the other. Also, to provide some functional understanding of the identified proteins, we blasted the whole protein sequences of all identified proteins against Sellginella moellendorfii and A. thaliana Uniprot sequences and retrieved the best matching identifier from each of them, along with the corresponding e-value, accepting blast-hits with -values below 1E-7. These better described ortholog identifiers were then used in further downstream analysis.

4.5. Protein Analysis Using the STRING Platform

The identifiers of the genes from apomictic and sexual gametophyte samples were used as input for STRING platform version 11.5 analysis and a high threshold (0.700) was selected for positive interaction between a pair of genes.

4.6. Statistical Analyses

Regarding the two major protein-protein interactions highlighted for carbohydrates metabolism, amino acid biosynthesis, energy metabolism and transcription and translation, a Pearson’s correlation test was performed using R software, and p-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of a set of 218 proteins shared by the gametophytes of the apomictic fern D. affinis and its sexual relative D. oreades revealed the presence of proteins mostly involved in biological functions associated with metabolism, the processing of genetic information. and abiotic stress. Some smaller protein groups were studied in detail: metabolism of carbohydrates, biosynthesis of amino acids, metabolism of energy, metabolism of secondary compounds, transcription, translation, and transport, and abiotic stress. Possible interactions between these proteins were identified, the most common source of evidence for interactions stemming from databases and textmining information. The proteins involved in transcription and translation exhibit the strongest interactions. The description of possible biological functions and the possible protein-protein interactions among the identified proteins expands our current knowledge about ferns and plants in general.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1. Strongest STRING interactions of proteins extracted from gametophytes of D. affinis and D. oreades, classified into the following groups: metabolism of carbohydrates, biosynthesis of amino acids, metabolism of energy, metabolism of secondary compounds, transcription, translation, and transport.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F. and U.G.; methodology, H.F., J.G., V.G., J.M.A., and S.O.; formal analysis, J.G. and H.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.F. and S.O., with help from U.G.; writing—review and editing, U.G., J.G., V.G., L.G.Q., and J.M.A.; funding acquisition, H.F. and U.G.; resources, L.G.Q. and U.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of Zurich, the University of Oviedo: GrantCESSTT1819 for International Mobility of Research Staff, and the European Union’s 7th Framework Program: PRIME-XS-0002520.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Oviedo for a grant from International Mobility of Research Staff, according to the collaboration agreement CESSTT1819, and the Functional Genomics Center Zurich for access to its excellent infrastructure. We also thank Hans Peter Schöb for his logistic support during H.F.’s visits to the Grossniklaus laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wada, M. The fern as a model system to study photomorphogenesis. J. Plant Res. 2007, 120, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.L.; Bushart, T.; Stout, S.; Roux, S. Profile and analysis of gene expression changes during early development in germinating spores of Ceratopteris richardii. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 1734–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.L.; Morris, K.E.; Roux, S.J.; Porterfield, D.M. Nitric oxide and CGMP signaling in calcium-dependent development of cell polarity in Ceratopteris richardii. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Cao, J.; Liu, G.; Wei, X.; Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Dai, S. Cytological and proteomic analyses of Osmunda cinnamomea germinating spores reveal characteristics of fern spore germination and rhizoid tip growth. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2015, 14, 2510–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. L.; Bushart, T. J. Cellular, molecular, and genetic changes during the development of Ceratopteris richardii gametophytes. In Working with ferns: Issues and Applications; Fernández, H., Kumar, A., Revilla, M.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhout, S.; Leroux, O.; Willats, W. G.; Popper, Z. A.; Viane, R. L. Comparative glycan profiling of Ceratopteris richardii ‘C-fern’ gametophytes and sporophytes links cell-wall composition to functional specialization. Ann Bot. 2014, 114(6), 1295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, H.; Revilla, M.A. In vitro culture of ornamental ferns. Plant Cell. Tissue Organ Cult. 2003, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Cañal, M. J.; Grossniklaus, U.; Fernández, H. The gametophyte of fern: born to reproduce. In: Current Advances in Fern Research. Fernández, H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3-19.

- Chen, C.-Y.; Chiu, F.-Y.; Lin, Y.; Huang, W.-J.; Hsieh, P.-S.; Hsu, F.-L. Chemical constituents analysis and antidiabetic activity validation of four fern species from Taiwan. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2015, 16, 2497–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femi-Adepoju, A.G.; Dada, A.O.; Otun, K.O.; Adepoju, A.O.; Fatoba, O. P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using terrestrial fern (Gleichenia pectinata (Willd.) C. Presl.): characterization and antimicrobial studies. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Cao, F.; Guo, L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, T.; Yan, X.; Dai, S. Desiccation tolerance mechanism in resurrection fern-ally Selaginella tamariscina revealed by physiological and proteomic analysis. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 6561–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinasabapathi, B. Ferns represent an untapped biodiversity for improving crops for environmental stress tolerance. New Phytol. 2006, 172, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, B. Role of ferns in environmental cleanup. In Current Advances in Fern Research; Fernández, H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 517–531. [Google Scholar]

- Der, J.P.; Barker, M.S.; Wickett, N.J.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Wolf, P.G. De novo characterization of the gametophyte transcriptome in bracken fern, Pteridium aquilinum. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordle, A.; Irish, E.; Cheng, C.L. Gene expression associated with apogamy commitment in Ceratopteris richardii. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2012, 25, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valledor, L.; Menéndez, V.; Canal, M.J.; Revilla, A.; Fernández, H. Proteomic approaches to sexual development mediated by antheridiogen in the fern Blechnum spicant L. Proteomics 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aya, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Tanaka, J.; Ohyanagi, H.; Suzuki, T.; Yano, K.; Takano, T.; Yano, K.; Matsuoka, M. De novo transcriptome assembly of a fern, Lygodium japonicum, and a web resource database Ljtrans DB. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, J.; Fernández, H.; Chaubey, P. M.; Valdés, A. E.; Gagliardini, V.; Cañal, M. J.; Russo, G.; Grossniklaus, U. Proteogenomic analysis greatly expands the identification of proteins related to reproduction in the apogamous fern Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyder, S.; Rivera, A.; Valdés, A.E.; Cañal, M. J.; Gagliardini, V.; Fernández, H.; Grossniklaus, U. Differential gene expression profiling of one- and two-dimensional apogamous gametophytes of the fern Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, H.; Grossmann, J.; Gagliardini, V.; Feito, I.; Rivera, A.; Rodríguez, L.; Quintanilla, L.G.; Quesada, V.; Cañal, M.J.; Grossniklaus, U. Sexual and apogamous species of woodferns show different protein and phytohormone profiles. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojosnegros, S.; Alvarez, J. M.; Grossmann, J.; Gagliardini, V.; Quintanilla, L. G.; Grossniklaus, U.; Fernández, H. The shared proteome of the apomictic fern Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis and its sexual relative Dryopteris oreades. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23(22), 14027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronconi, M.A.; Fahnenstich, H.; Gerrard Weehler, M.C.; Andreo, C. S.; Flügge, U.I.; Drincovich, M.F.; Maurino, V.G. Arabidopsis NAD-malic enzyme functions as a homodimer and heterodimer and has a major impact on nocturnal metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Assmann, S.M. The glycolytic enzyme, phosphoglycerate mutase, has critical roles in stomatal movement, vegetative growth, and pollen production in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaz, T.; Bagard, M.; Pracharoenwattana, I.; Lindén, P.; Lee, C.P.; Carroll, A.J.; Ströher, E.; Smith, S.M.; Gardeström, P.; Millar, A.H. Mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase lowers leaf respiration and alters photorespiration and plant growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1143–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howles, P.A.; Birch, R.J.; Collings, D.A.; Gebbie, L.K.; Hurley, U.A.; Hocart, C.H.; Arioli, T.; Williamson, R. E. A mutation in an Arabidopsis ribose 5-phosphate isomerase reduces cellulose synthesis and is rescued by exogenous uridine. Plant J. 2006, 48, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakao, S.; Benning, C. Genome-wide analysis of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005, 41, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, D.; Maple-Grødem, J.; Møller, S.G. In vivo phosphorylation of FtsZ2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. J. 2012, 446, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seung, D.; Soyk, S.; Coiro, M.; Maier, B.A.; Eicke, S.; Zeeman, S. C. PROTEIN TARGETING TO STARCH is required for localising GRANULE-BOUND STARCH SYNTHASE to starch granules and for normal amylose synthesis in Arabidopsis. PLOS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautengarten, C.; Ebert, B.; Herter, T.; Petzold, C.J.; Ishii, T.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Usadel, B.; Scheller, H.V. The interconversion of UDP-arabinopyranose and UDP-arabinofuranose is indispensable for plant development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1373–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.; He, Y.; Dai, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Deficiency in fatty acid synthase leads to premature cell death and dramatic alterations in plant morphology. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatland, B.L.; Ke, J.; Anderson, M.D.; Mentzen, W.I.; Wei Cui, L.; Christy Allred, C.; Johnston, J.L.; Nikolau, B.J.; Syrkin Wurtele, E.; Biology LWC, M. Molecular characterization of a heteromeric ATP-citrate lyase that generates cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme A in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatland, B.L.; Nikolau, B.J.; Wurtele, E. S. Reverse genetic characterization of cytosolic acetyl-CoA generation by ATP-citrate lyase in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracharoenwattana, I.; Cornah, J.E.; Smith, S.M. Arabidopsis peroxisomal citrate synthase is required for fatty acid respiration and seed germination. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 2037–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knill, T.; Reichelt, M.; Paetz, C.; Gershenzon, J.; Binder, S. Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a bacterial-type heterodimeric isopropylmalate isomerase involved in both Leu biosynthesis and the Met chain elongation pathway of glucosinolate formation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 71, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Ohsumi, C.; Totsuka, K.; Igarashi, D. Analysis of glutamate homeostasis by overexpression of Fd-GOGAT gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Amin. Acids 2009, 38, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, K.; Sandoval, F. J.; Santiago, K.; Roje, S. One-carbon metabolism in plants: characterization of a plastid serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Biochem. J. 2010, 430, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.N.; Marineo, S.; Mandalà, S.; Davids, F.; Sewell, B.T.; Ingle, R.A. The missing link in plant histidine biosynthesis: Arabidopsis myoinositol monophosphatase-like2 encodes a functional histidinol-phosphate phosphatase. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Li, C.; Tarczynski, M.C. High free-methionine and decreased lignin content result from a mutation in the Arabidopsis S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthetase 3 gene. Plant J. 2002, 29(3), 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintala, M.; Allahverdiyeva, Y.; Kidron, H.; Piippo, M.; Battchikova, N.; Suorsa, M.; Rintamäki, E.; Salminen, T.A.; Aro, E. M.; Mulo, P. Structural and functional characterization of ferredoxin-NADP+-oxidoreductase using knock-out mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007, 49, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieselbach, T.; Bystedt, M.; Hynds, P.; Robinson, C.; Schröder, W.P. A peroxidase homologue and novel plastocyanin located by proteomics to the Arabidopsis chloroplast thylakoid lumen. FEBS Lett. 2000, 480, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, B.; Hansson, M.; Schoefs, B.; Vener, A. V.; Spetea, C. The Arabidopsis PsbO2 protein regulates dephosphorylation and turnover of the photosystem II reaction centre D1 protein. Plant J. 2007, 49, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Last, R.L. A chloroplast thylakoid lumen protein is required for proper photosynthetic acclimation of plants under fluctuating light environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Mao, Z.; Guo, S.; Yang, C.; Weng, Y.; Chong, K. The cyclophilin CYP20-2 modulates the conformation of BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1, which binds the promoter of FLOWERING LOCUS D to regulate flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2504–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracher, A.; Sharma, A.; Starling-Windhof, A.; Hartl, F.U.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Degradation of potent rubisco inhibitor by selective sugar phosphatase. Nat. Plants 2014, 112015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, R.; Edner, C.; Kolukisaoglu, Ü.; Hagemann, M.; Weckwerth, W.; Wienkoop, S.; Morgenthal, K.; Bauwe, H. D-glycerate 3-kinase, the last unknown enzyme in the photorespiratory cycle in Arabidopsis, belongs to a novel kinase family. PlantCell 2005, 17, 2413–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, L.; Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xiang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y. Overexpression of AtAGT1 promoted root growth and development during seedling establishment. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanda, S.; Leustek, T.; Theisen, M.J.; Garavito, R.M.; Benning, C. Recombinant Arabidopsis SQD1 converts UDP-glucose and sulfite to the sulfolipid head group precursor UDP-sulfoquinovose in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 3941–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Abdel-Ghany, S. E.; Anderson, T. D.; Pilon-Smits, E. A.; Pilon, M. CpSufE activates the cysteine desulfurase CpNifS for chloroplastic Fe-S cluster formation. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281(13), 8958–8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario-Méry, S.; Meyer, C.; Hodges, M. Chloroplast nitrite uptake is enhanced in Arabidopsis PII mutants. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Ida, S.; Morikawa, H. Nitrite reductase gene enrichment improves assimilation of NO(2) in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, B.W.; Hanley, S.; Goodman, H. M. Effects of ionizing radiation on a plant genome: analysis of two Arabidopsis transparent testa mutations. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eudes, A.; Pollet, B.; Sibout, R.; Do, C.T.; Séguin, A.; Lapierre, C.; Jouanin, L. Evidence for a role of AtCAD 1 in lignification of elongating stems of Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2006, 225, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlting, J.; Büttner, D.; Wang, Q.; Douglas, C.J.; Somssich, I.E.; Kombrink, E. Three 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligases in Arabidopsis thaliana represent two evolutionarily divergent classes in angiosperms. Plant J. 1999, 19, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, H.J.; Muskopf, Y.M.; Gasser, C.S. Cloning of an Arabidopsis thaliana gene encoding 5-enolpyruvyl shikimate-3-phosphate synthase: sequence analysis and manipulation to obtain glyphosate-tolerant plants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1987, 210, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasinghe, G.P.K.; Sander, I.M.; Bennett, B.; Periyannan, G.; Yang, K. W.; Makaroff, C.A.; Crowder, M. W. Structural studies on a mitochondrial glyoxalase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 40668–40675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, P.; Keech, O.; Stenlund, H.; Gardeström, P.; Moritz, T. Reduced mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase activity has a strong effect on photorespiratory metabolism as revealed by 13C labelling. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 3123–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.P.; Edwards, R. Roles for stress-inducible lambda glutathione transferases in flavonoid metabolism in plants as identified by ligand fishing. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 36322–36329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, M.; Alsterfjord, M.; Larsson, C.; Sommarin, M. Data mining the Arabidopsis genome reveals fifteen 14-3-3 genes. expression is demonstrated for two out of five novel genes. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Hanson, M.R.; Bentolila, S. Two RNA recognition motif-containing proteins are plant mitochondrial editing factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 3814–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambermon, M.H.L.; Fu, Y.; Kirk, D.A.W.; Dupasquier, M.; Filipowicz, W.; Lorković, Z.J. UBA1 and UBA2, two proteins that interact with UBP1, a multifunctional effector of pre-mRNA maturation in plants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 4346–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xiong, L.; Ishitani, M.; Zhu, J.K. An Arabidopsis mutation in translation elongation factor 2 causes superinduction of CBF/DREB1 transcription factor genes but blocks the induction of their downstream targets under low temperatures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 7786–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalitzky, C.A.; Martin, J.R.; Harwood, J.H.; Beirne, J.J.; Adamczyk, B.J.; Heck, G.R.; Cline, K.; Fernandez, D. E. Plastids contain a second Sec translocase system with essential functions. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haizel, T.; Merkle, T.; Pay, A.; Fejes, E.; Nagy, F. Characterization of proteins that interact with the GTP-bound form of the regulatory GTPase Ran in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1997, 11, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Lee, L.Y.; Oltmanns, H.; Cao, H.; Veena; Cuperus, J.; Gelvin, S.B. IMPa-4, an Arabidopsis importin α isoform, is preferentially involved in Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2661–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, I.; Hackstein, J. H.P.; Voncken, F.G.J.; Schmit, G.; Tjaden, J. Functional integration of mitochondrial and hydrogenosomal ADP/ATP carriers in the Escherichia coli membrane reveals different biochemical characteristics for plants, mammals and anaerobic chytrids. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 3172–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchler, M.; Decker, S.; Hörmann, F.; Soll, J.; Heins, L. Protein import into chloroplasts involves redox-regulated proteins. EMBOJ. 2002, 21, 6136–6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Chung, G.C.; Jang, J.Y.; Ahn, S.J.; Zwiazek, J.J. Overexpression of PIP2;5 aquaporin alleviates effects of low root temperature on cell hydraulic conductivity and growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrier, C.; Peyronnet, R.; Betton, J.M.; Ephritikhine, G.; Barbier-Brygoo, H.; Frachisse, J.M.; Ghazi, A. Channel characteristics of VDAC-3 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 459, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislas, T.; Hüser, A.; Barbosa, I.C.R.; Kiefer, C.S.; Brackmann, K.; Pietra, S.; Gustavsson, A.; Zourelidou, M.; Schwechheimer, C.; Grebe, M. Arabidopsis D6PK is a lipid domain-dependent mediator of root epidermal planar polarity. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žárský, V.; Cvrčková, F.; Bischoff, F.; Palme, K. At-GDI1 from Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a Rab-specific GDP dissociation inhibitor that complements the Sec19 mutation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1997, 403, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ståhl, A.; Moberg, P.; Ytterberg, J.; Panfilov, O.; Von Löwenhielm, H. B.; Nilsson, F.; Glaser, E. Isolation and identification of a novel mitochondrial metalloprotease (PreP) that degrades targeting presequences in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 41931–41939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Pu, H.; Shen, J.; Adam, Z.; Clausen, T.; Zhang, L. The crystal structure of Deg9 reveals a novel octameric-type HtrA protease. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scranton, M.A.; Yee, A.; Park, S.Y.; Walling, L. L. Plant leucine aminopeptidases moonlight as molecular chaperones to alleviate stress-induced damage. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 18408–18417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condori-Apfata, J. A.; Batista-Silva, W.; Medeiros, D. B.; Vargas, J. R.; Valente, L. M. L.; Pérez-Díaz, J. L.; Fernie, A. R; Araújo, W. L.; Nunes-Nesi, A. Downregulation of the E2 subunit of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase modulates plant growth by impacting carbon-nitrogen metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62(5), 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Swart, C.; Alseekh, S.; Scossa, F.; Jiang, L.; Obata, T.; Graf, A.; Fernie, A. R. The extra-pathway interactome of the TCA cycle: expected and unexpected metabolic interactions. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177(3), 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zang, X.; Yuan, S.; Bat-Erdene, U.; Nguyen, C.; Gan, J.; Zhou, J.; Jacobsen, S. E.; Tang, Y. Resistance-gene-directed discovery of a natural-product herbicide with a new mode of action. Nature 2018, 559(7714), 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraker, J. W. de; Luck, K.; Textor, S.; Tokuhisa, J. G.; Gershenzon, J. Two Arabidopsis genes (IPMS1 andIPMS2) encode isopropylmalate synthase, the branchpoint step in the biosynthesis of leucine. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143(2), 970–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Mawhinney, T. P.; Chen, B.; Kang, B. H.; Hauser, B. A.; Chen, S. Functional characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana isopropylmalate dehydrogenases reveals their important roles in gametophyte development. New Phytol. 2011, 189(1), 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotto, C.; Pesaresi, P.; Meurer, J.; Oelmüller, R.; Steiner-Lange, S.; Salamini, F.; Leister, D. Disruption of the Arabidopsis photosystem I gene psaE1 affects photosynthesis and impairs growth. Plant J. 2000, 22(2), 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, F. C.; Davin, L. B.; Lewis, N. G. The Arabidopsis phenylalanine ammonia lyasegene family: kinetic characterization of the four PAL isoforms. Phytochemistry 2004, 65(11), 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, X.; Gong, P.; Xu, Q.; Yu, Q. B.; Guan, Y. Pooled CRISPR/Cas9 reveals redundant roles of plastidial phosphoglycerate kinases in carbon fixation and metabolism. Plant J. 2019, 98(6), 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, D.; Amako, K.; Hashiguchi, M.; Fukaki, H.; Ishizaki, K.; Goh, T.; Fukao, Y.; Sano, R.; Kurata, T.; Demura, T.; Sawa, S.; Miyake, C. Chloroplastic ATP synthase builds up a proton motive forcepreventing production of reactive oxygen species in photosystem I. Plant J. 2017, 91(2), 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. J.; Heazlewood, J. L.; Ito, J.; Millar, A. H. Analysis of the Arabidopsis cytosolic ribosome proteome provides detailed insights into its components and their post-translational modification. Mol. Cell Proteomics 2008, 7(2), 347–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, J.; Batth, T. S.; Petzold, C. J.; Redding-Johanson, A. M.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Verboom, R.; Meyer, E. H.; Millar, A. H.; Heazlewood, J. L. Analysis of the Arabidopsis cytosolic proteome highlights subcellular partitioning of central plant metabolism. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10(4), 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Plant Physiol. 1962, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

GO enrichment terms of the shared proteomes obtained from gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades according to the category biological function, analyzed by STRING and CYTOSCAPE. Turquoise indicates metabolism of carbohydrates, yellow metabolism of energy, pink transcription and translation, and green protein degradation.

Figure 1.

GO enrichment terms of the shared proteomes obtained from gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades according to the category biological function, analyzed by STRING and CYTOSCAPE. Turquoise indicates metabolism of carbohydrates, yellow metabolism of energy, pink transcription and translation, and green protein degradation.

Figure 2.

KEGG enrichment terms of the shared proteomes obtained from gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades, analyzed using the STRING platform.

Figure 2.

KEGG enrichment terms of the shared proteomes obtained from gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades, analyzed using the STRING platform.

Figure 3.

Proteins involved in ribogenesis found in the gametophyte of the ferns Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades. Imaged provided by STRING platform according to KEGG dataset. “Light-green” highlighted boxes are the identified proteins.

Figure 3.

Proteins involved in ribogenesis found in the gametophyte of the ferns Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades. Imaged provided by STRING platform according to KEGG dataset. “Light-green” highlighted boxes are the identified proteins.

Figure 4.

Proteins of the proteasome found in gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades. Images provided by the STRING platform according to KEGG annotations. Boxes highlighted in green represent identified proteins.

Figure 4.

Proteins of the proteasome found in gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades. Images provided by the STRING platform according to KEGG annotations. Boxes highlighted in green represent identified proteins.

Figure 5.

Circular representations obtained by STRING and CYTOSCAPE for proteins detected in the gametophytes of both Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades: (a) metabolism of carbohydrates, (b) metabolism of energy, (c) ribogenesis, and (d) protein degradation. Pink lines refer to evidence from experiments, green lines from textmining, black lines from co-expression, and blue lines from databases.

Figure 5.

Circular representations obtained by STRING and CYTOSCAPE for proteins detected in the gametophytes of both Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades: (a) metabolism of carbohydrates, (b) metabolism of energy, (c) ribogenesis, and (d) protein degradation. Pink lines refer to evidence from experiments, green lines from textmining, black lines from co-expression, and blue lines from databases.

Figure 6.

Plots of the two main types of evidence for interactions in the groups of proteins shared by the gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades: (a) metabolism of carbohydrates, (b) biosynthesis of amino acids, (c) metabolism of energy, and (d) transcription and translation. Each spot represents the intersection of the type of evidence for interactions between two proteins. The linear regression and the coefficient of correlation are provided for each pair of evidence for the interaction.

Figure 6.

Plots of the two main types of evidence for interactions in the groups of proteins shared by the gametophytes of Dryopteris affinis and D. oreades: (a) metabolism of carbohydrates, (b) biosynthesis of amino acids, (c) metabolism of energy, and (d) transcription and translation. Each spot represents the intersection of the type of evidence for interactions between two proteins. The linear regression and the coefficient of correlation are provided for each pair of evidence for the interaction.

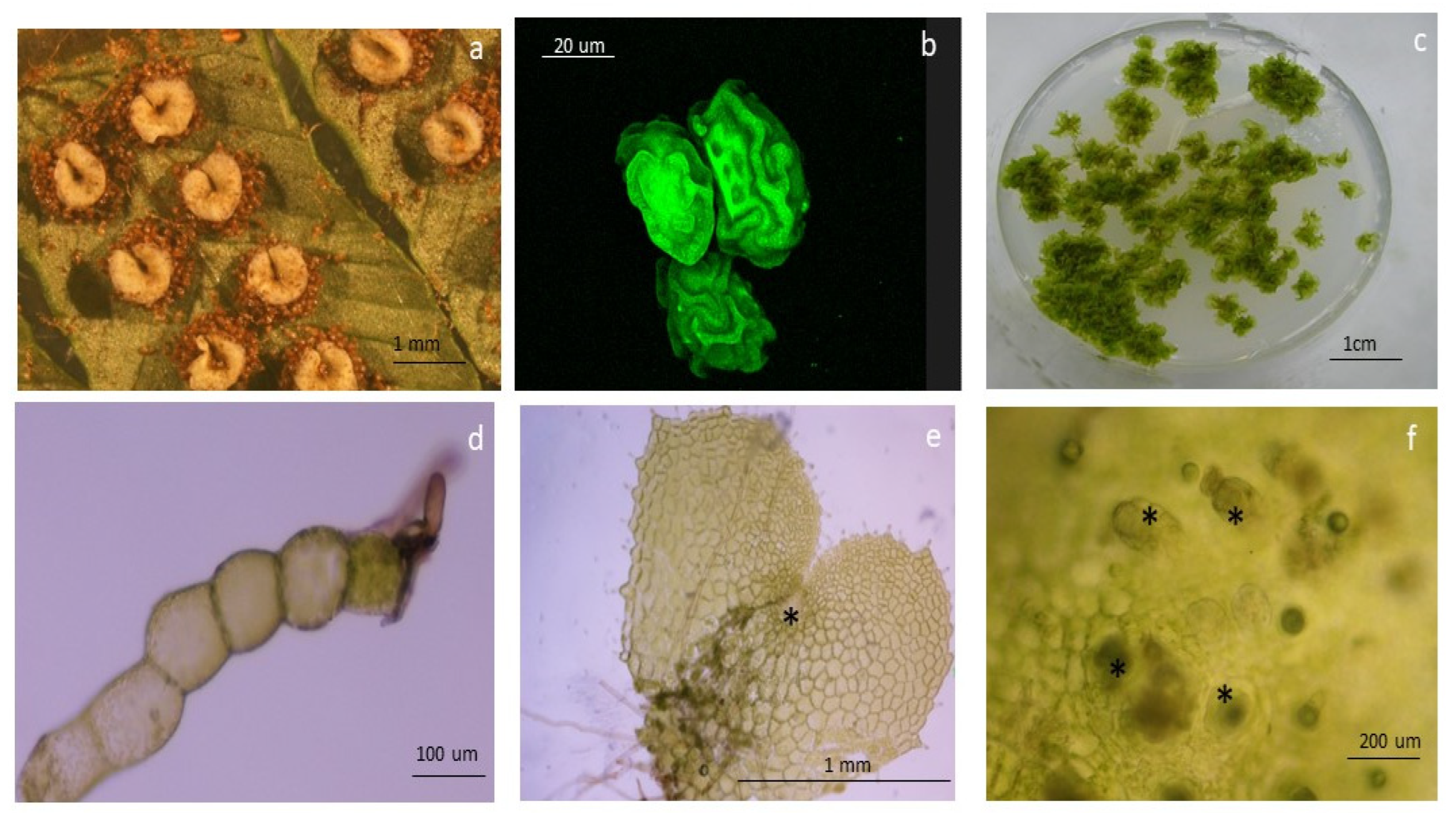

Figure 7.

Morphological traits in the apomictic fern Dryopteris affinis and its sexual relative D. oreades: (a) typical kidney-shaped sori on the leaf underside; (b) confocal image of spores; (c) gametophytes growing in a Petri dish; (d) and (e) images taken under a light microscope of one- and two-dimensional gametophytes of D. affinis; asteric shows an apomictic center; and finally (f) refers to archegonia, indicated by asterics, in the gametophyte of D. oreades.

Figure 7.

Morphological traits in the apomictic fern Dryopteris affinis and its sexual relative D. oreades: (a) typical kidney-shaped sori on the leaf underside; (b) confocal image of spores; (c) gametophytes growing in a Petri dish; (d) and (e) images taken under a light microscope of one- and two-dimensional gametophytes of D. affinis; asteric shows an apomictic center; and finally (f) refers to archegonia, indicated by asterics, in the gametophyte of D. oreades.

Table 1.

Biological functions and number of interactions exhibited by proteins common to apomictic D. affinis and sexual D. oreades.

Table 1.

Biological functions and number of interactions exhibited by proteins common to apomictic D. affinis and sexual D. oreades.

| Biological functions |

Protein |

Nº Interactions |

| Metabolism of carbohydrates |

ENOC |

12 |

| PGK1 |

12 |

| Biosynthesis of amino acids |

AT1G14810 |

6 |

| Metabolism of energy |

ATPC1 |

20 |

| Secondary metabolism |

4CL3 |

3 |

| Transcription & Translation |

SAC56 |

44 |

| US11X |

44 |

| US17Y |

44 |

| Transport |

RAB1A |

4 |

Table 2.

Selected proteins found in gametophytes of both apomictic D. affinis and sexual D. oreades.

Table 2.

Selected proteins found in gametophytes of both apomictic D. affinis and sexual D. oreades.

| Category |

Accession Number |

UniProtKB/

Swiss-Prot

|

Gene Name |

Protein Name |

MW (kDa) |

Amino

Acids

|

| Carbohydrates |

58787-330_2_ORF2 |

Q94AA4 |

PFK3 |

Phosphofructokinase 3 |

53 |

489 |

| Carbohydrates |

135690-210_1_ORF2 |

Q9ZU52 |

PDE345 |

Pigment defective 345 |

42 |

391 |

| Carbohydrates |

tr|A9NMQ0|A9NMQ0_PICSI |

Q9LF98 |

FBA8 |

Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase 8 |

38 |

358 |

| Carbohydrates |

38153-411_5_ORF2 |

Q38799 |

MAB1 |

Macchi-bou1 |

39 |

363 |

| Carbohydrates |

83096-276_3_ORF2 |

Q5GM68 |

PPC2 |

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase 2 |

109 |

963 |

| Carbohydrates |

54280-344_1_ORF1 |

Q84VW9 |

PPC3 |

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase 3 |

110 |

968 |

| Carbohydrates |

113756-233_2_ORF1 |

Q9SIU0 |

NAD-ME1 |

NAD-dependent malic enzyme 1 |

69 |

623 |

| Carbohydrates |

102811-246_6_ORF2 |

O04499 |

iPGAM1 |

2,3-biphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase 1 |

60 |

557 |

| Carbohydrates |

70011-302_2_ORF1 |

O82662 |

AT2G20420 |

- |

45 |

421 |

| Carbohydrates |

8279-816_3_ORF2 |

P68209 |

AT5G08300 |

- |

36 |

347 |

| Carbohydrates |

222487-119_2_ORF2 |

P93819 |

c-NAD-MDH1 |

Cytosolic-NAD-dependent malate dehydrogenase 1 |

35 |

332 |

| Carbohydrates |

156827-185_4_ORF1 |

Q9SH69 |

PGD1 |

6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 1 |

53 |

487 |

| Carbohydrates |

12493-682_6_ORF2 |

Q9FJI5 |

G6PD6 |

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 6 |

59 |

515 |

| Carbohydrates |

20760-547_4_ORF1 |

Q9LD57 |

PGK1 |

Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 |

50 |

481 |

| Carbohydrates |

69882-302_6_ORF2 |

Q9LZS3 |

SBE2.2 |

Starch branching enzyme 2.2 |

92 |

805 |

| Carbohydrates |

tr|Q5PYJ7|Q5PYJ7_9MONI |

Q9MAQ0 |

GBSS1 |

Granule bound starch synthase 1 |

66 |

610 |

| Carbohydrates |

tr|A9SGH8|A9SGH8_PHYPA |

P55228 |

ADG1 |

ADP glucose pyro-phosphorylase 1 |

56 |

520 |

| Carbohydrates |

181563-155_3_ORF2 |

P55229 |

APL1 |

ADP glucose pyro-phosphorylase large subunit 1 |

57 |

522 |

| Carbohydrates |

tr|D7MQA6|D7MQA6_ARALL |

Q9LUE6 |

RGP4 |

Reversibly glycosylated polypeptide 4 |

41 |

364 |

| Carbohydrates |

162660-176_6_ORF1 |

P83291 |

AT5G20080 |

- |

35 |

328 |

| Lipids |

20213-554_2_ORF1 |

Q9SLA8 |

MOD1 |

Mosaic death 1 |

41 |

390 |

| Lipids |

387953-27_4_ORF1 |

Q9SGY2 |

ACLA-1 |

ATP-citrate lyase A-1 |

49 |

443 |

| Category |

Accession Number |

UniProtKB/

Swiss-Prot

|

Gene Name |

Protein Name |

MW (kDa) |

Amino

Acids

|

| Lipids |

211149-128_1_ORF1 |

Q9LXS6 |

CSY2 |

Citrate synthase 2 |

56 |

514 |

| Amino acids |

47558-369_4_ORF2 |

P46643 |

ASP1 |

Aspartate aminotransferase 1 |

47 |

430 |

| Amino acids |

72506-296_4_ORF1 |

Q94AR8 |

IIL1 |

Isopropyl malate isomerase large subunit 1 |

55 |

509 |

| Amino acids |

125905-219_3_ORF2 |

Q9ZNZ7 |

GLU1 |

Glutamate synthase 1 |

179 |

1,648 |

| Amino acids |

393073-25_4_ORF2 |

Q94JQ3 |

SHM3 |

Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 3 |

57 |

529 |

| Amino acids |

tr|D8RLH8|D8RLH8_SELML |

Q9C5U8 |

HDH |

Histidinol dehydrogenase |

50 |

466 |

| Amino acids |

294436-71_4_ORF2 |

Q9LUT2 |

MTO3 |

Methionine over-accumulator 3 |

42 |

393 |

| Nucleotides |

2121-1366_3_ORF2 |

Q9SF85 |

ADK1 |

Adenosine kinase 1 |

37 |

344 |

| Nucleotides |

59309-329_5_ORF1 |

Q96529 |

ADSS |

Adenylosuccinate synthase |

52 |

490 |

| Nucleotides |

152024-193_3_ORF2 |

Q9S726 |

EMB3119 |

Embryo defective 3119 |

29 |

276 |

| Energy |

164104-175_1_ORF1 |

Q9FKW6 |

FNR1 |

Ferredoxin-NADP (+)-oxidoreductase 1 |

40 |

360 |

| Energy |

sp|Q7SIB8|PLAS_DRYCA |

P42699 |

DRT112 |

DNA-damage-repair/toleration protein 112 |

16 |

167 |

| Energy |

154679-189_1_ORF2 |

Q9S841 |

PSBO2 |

Photosystem II subunit O-2 |

35 |

331 |

| Energy |

218625-122_1_ORF2 |

O22773 |

MPH2 |

Maintenance of photosystem II under high light 2 |

23 |

216 |

| Energy |

6036-926_2_ORF1 |

Q9ASS6 |

Pnsl5 |

Photosynthetic NDH subcomplex l 5 |

28 |

259 |

| Energy |

250817-99_2_ORF2 |

Q94K71 |

AT3G48420 |

- |

34 |

319 |

| Energy |

tr|A9RDI1|A9RDI1_PHYPA |

Q944I4 |

GLYK |

Glycerate kinase |

51 |

456 |

| Energy |

297118-70_2_ORF2 |

Q56YA5 |

AGT |

Alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase |

44 |

401 |

| Energy |

33137-439_6_ORF2 |

O48917 |

SQD1 |

Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol 1 |

53 |

477 |

| Energy |

227095-115_1_ORF2 |

Q84W65 |

CPSUFE |

Chloroplast sulfur E |

40 |

371 |

| Energy |

311596-62_2_ORF2 |

Q9ZST4 |

GLB1 |

GLNB1 homolog |

21 |

196 |

| Energy |

318906-58_1_ORF1 |

Q39161 |

NIR1 |

Nitrite reductase 1 |

65 |

586 |

| Secondary compounds |

156331-186_3_ORF2 |

P41088 |

TT5 |

Transparent testa 5 |

26 |

246 |

| Secondary compounds |

230420-113_2_ORF2 |

P34802 |

GGPS1 |

Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase 1 |

40 |

371 |

| Secondary compounds |

85783-271_1_ORF2 |

Q9T030 |

PCBER1 |

Phenylcoumaran benzylic ether reductase 1 |

34 |

308 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Category |

Accession Number |

UniProtKB/

Swiss-Prot

|

Gene Name |

Protein Name |

MW (kDa) |

Amino

Acids

|

| Secondary compounds |

153413-190_1_ORF2 |

P42734 |

CAD9 |

Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 9 |

38 |

360 |

| Secondary compounds |

156554-185_2_ORF1 |

Q9S777 |

4CL3 |

4-coumarate:coA ligase 3 |

61 |

561 |

| Secondary compounds |

223603-118_1_ORF1 |

P05466 |

AT2G45300 |

- |

55 |

520 |

Oxido

-reduction |

133847-212_2_ORF2 |

Q9SID3 |

GLX2-5 |

Glyoxalase 2-5 |

35 |

324 |

Oxido

-reduction |

tr|E1ZRS4|E1ZRS4_CHLVA |

Q9ZP06 |

mMDH1 |

Mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase 1 |

35 |

341 |

Oxido

-reduction |

34437-432_2_ORF1 |

Q9M2W2 |

GSTL2 |

Glutathione transferase lambda 2 |

33 |

292 |

Oxido

-reduction |

115571-230_4_ORF1 |

Q9LZ06 |

GSTL3 |

Glutathione transferase L3 |

27 |

235 |

| Transcription |

tr|A2X6N1|A2X6N1_ORYSI |

Q96300 |

GRF7 |

General regulatory factor 7 |

29 |

265 |

| Transcription |

287872-75_1_ORF1 |

Q9C5W6 |

GRF12 |

General regulatory factor 12 |

30 |

268 |

| Translation |

209284-130_2_ORF2 |

Q9FNR1 |

RBGA7 |

MA-binding glycine-rich protein A7 |

29 |

309 |

| Translation |

293356-72_1_ORF1 |

Q9LR72 |

AT1G03510 |

- |

47 |

429 |

| Translation |

26795-487_6_ORF2 |

Q0WW84 |

RBP47B |

MA-binding protein 47B |

48 |

435 |

| Translation |

20230-554_5_ORF2 |

Q9LES2 |

UBA2A |

UBP1-associated protein 2A |

51 |

478 |

| Translation |

174433-162_1_ORF1 |

Q9ASR1 |

LOS1 |

Low expression of osmotically responsive genes 1 |

93 |

843 |

| Folding |

26640-489_1_ORF2 |

Q9M1C2 |

GROES |

- |

15 |

138 |

| Folding |

189606-147_1_ORF2 |

Q9SR70 |

AT3G10060 |

- |

24 |

230 |

| Folding |

149253-199_6_ORF2 |

O22870 |

AT2G43560 |

- |

23 |

223 |

| Folding |

2524-1285_6_ORF2 |

Q9SKQ0 |

AT2G21130 |

- |

18 |

174 |

| Transport |

19573-562_5_ORF2 |

Q9SYI0 |

AGY1 |

Albino or glassy yellow 1 |

117 |

1,042 |

| Transport |

248569-101_3_ORF1 |

P92985 |

RANBP1 |

RAN binding protein 1 |

24 |

219 |

| Transport |

146969-201_2_ORF1 |

F4JL11 |

IMPA-2 |

Importin alpha isoform 2 |

58 |

535 |

| Transport |

151836-193_1_ORF2 |

P40941 |

AAC2 |

ADP/ATP carrier 2 |

41 |

385 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Category |

Accession Number |

UniProtKB/

Swiss-Prot

|

Gene Name |

Protein Name |

MW (kDa) |

Amino

Acids

|

| Transport |

161087-178_2_ORF2 |

Q8H0U5 |

Tic62 |

Translocon at the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts 62 |

68 |

641 |

| Transport |

82340-277_1_ORF2 |

Q39196 |

PIP1;4 |

Plasma membrane intrinsic protein 1;4 |

30 |

287 |

| Transport |

154825-188_3_ORF2 |

Q9SMX3 |

VDAC3 |

Voltage dependent anion channel 3 |

29 |

274 |

| Transport |

272341-85_2_ORF2 |

Q94A40 |

alpha1-COP |

Alpha1 coat protein |

136 |

1,216 |

| Transport |

29489-466_3_ORF1 |

Q0WW26 |

gamma2-COP |

Gamma2 coat protein |

98 |

886 |

| Transport |

38639-409_2_ORF3 |

Q93Y22 |

AT5G05010 |

- |

57 |

527 |

| Transport |

43675-385_1_ORF2 |

Q67YI9 |

EPS2 |

Epsin2 |

95 |

895 |

| Transport |

68824-304_5_ORF2 |

Q9LQ55 |

DL3 |

Dynamin-like 3 |

100 |

920 |

| Transport |

- |

F4J3Q8 |

GET3B |

Guided entry of tail-anchored proteins 3B |

47 |

433 |

| Transport |

3434-1154_1_ORF2 |

Q96254 |

GDI1 |

Guanosine nucleotide diphosphate dissociation inhibitor 1 |

49 |

445 |

| Degradation |

141778-205_4_ORF2 |

Q8L770 |

AT1G09130 |

- |

40 |

370 |

| Degradation |

172993-163_5_ORF1 |

Q9XJ36 |

CLP2 |

CLP protease proteolytic subunit 2 |

31 |

279 |

| Degradation |

72587-296_2_ORF2 |

Q8LB10 |

CLPR4 |

CLP protease R subunit 4 |

33 |

305 |

| Degradation |

17420-593_1_ORF2 |

P93655 |

LON1 |

LON protease 1 |

109 |

985 |

| Degradation |

tr|A9SF86|A9SF86_PHYPA |

Q9LJL3 |

PREP1 |

Pre-sequence protease 1 |

121 |

1,080 |

| Degradation |

186732-150_2_ORF2 |

Q9FL12 |

DEG9 |

Degradation of periplasmic proteins 9 |

65 |

592 |

| Degradation |

170504-166_2_ORF2 |

P30184 |

LAP1 |

Leucyl aminopeptidase 1 |

54 |

520 |

| Degradation |

170504-166_2_ORF2 |

Q944P7 |

LAP3 |

Leucyl aminopeptidase 3 |

61 |

581 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).