Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

24 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

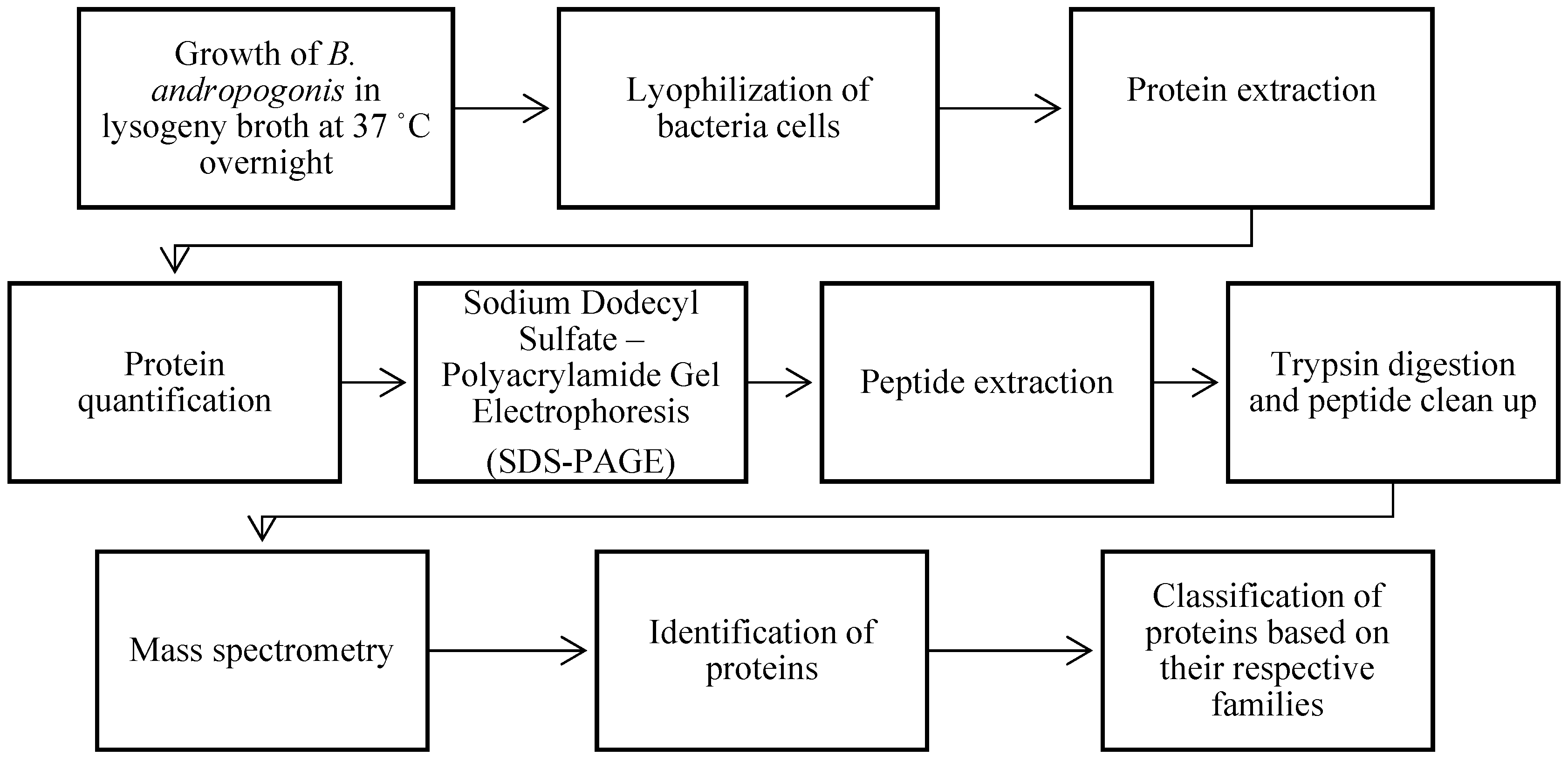

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extraction of Burkholderia andropogonis proteins

2.1.1. Growth of bacterial samples

2.1.2. Preparation of protein extract

2.2. Protein quantification

2.2.1. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay

2.2.2. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate – Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.3. Extraction of peptides

2.3.1. Reduction of disulfide bonds and alkylating free cysteines

2.3.2. In-gel digestion

2.3.3. Peptide sample clean-up and protein identification

2.4. Extraction of peptides

3. Results and discussion

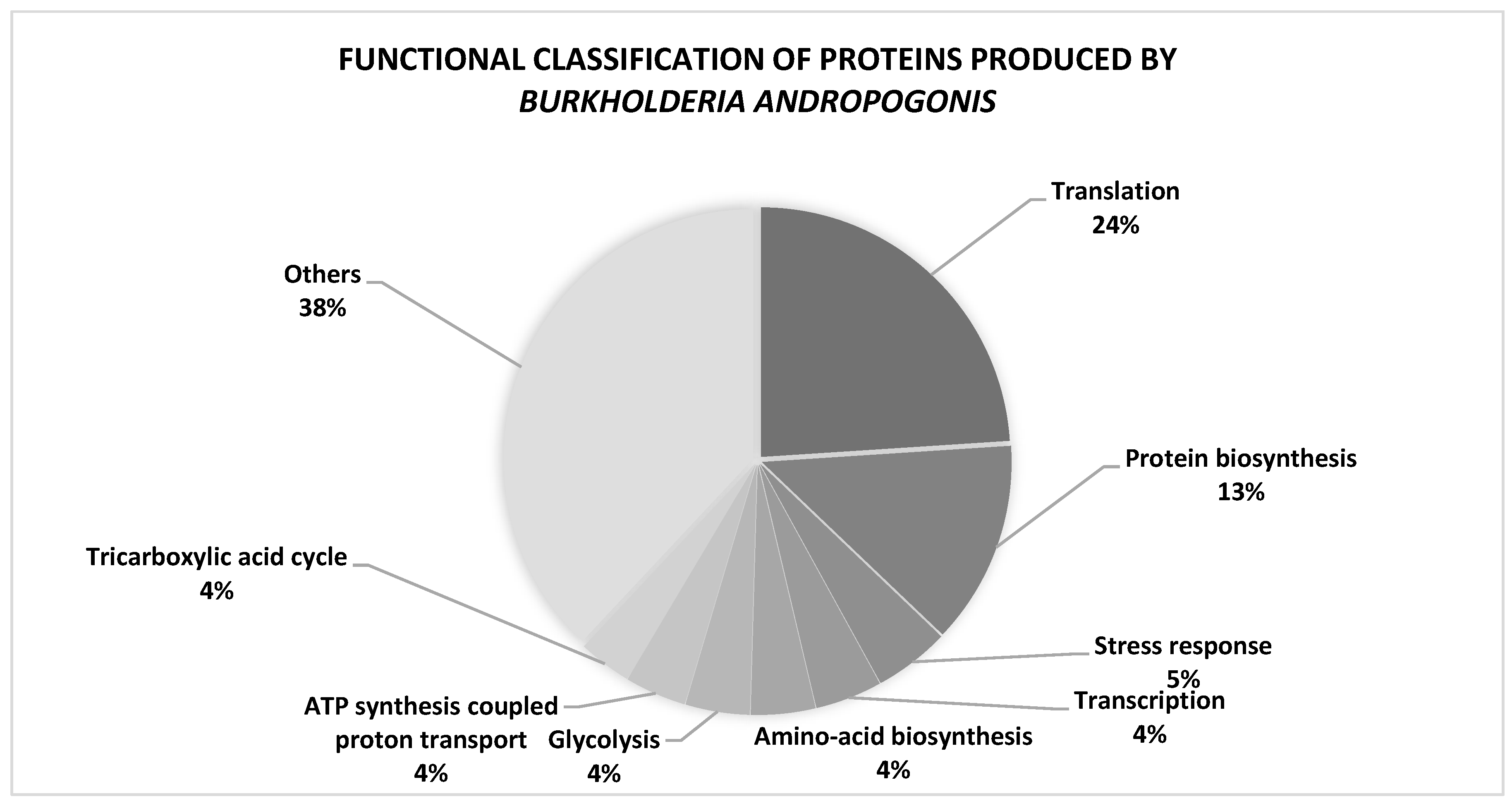

3.1. Protein profile of Burkholderia andropogonis

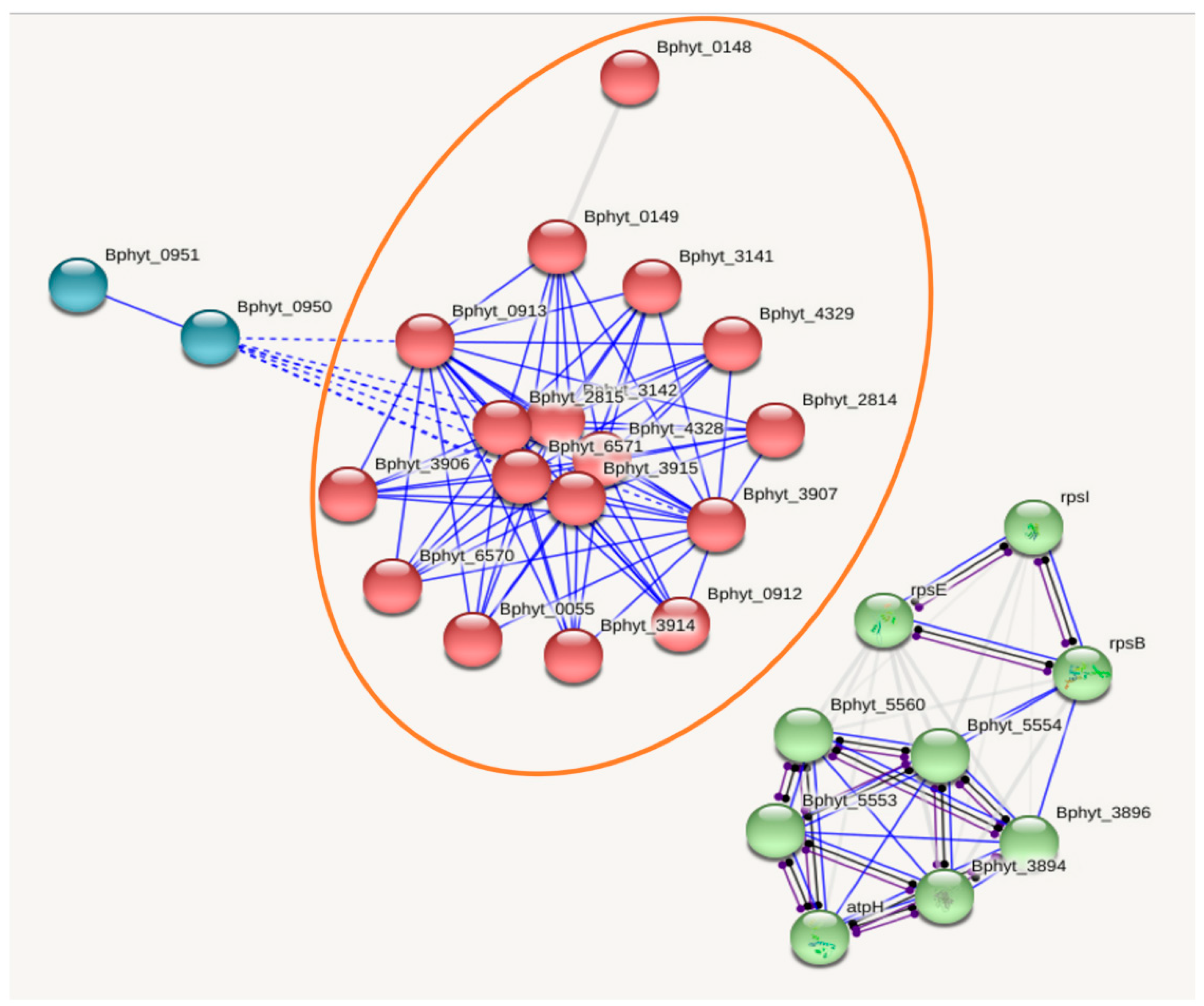

3.2. Functional information: Interactome analysis

3.3. Cellular pathways expressed in B. andropogonis

4. Conclusion and future perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Estrada-De Los Santos, P.; Bustillos-Cristales, R.; Caballero-Mellado, J. Burkholderia, a genus rich in plant-associated nitrogen fixers with wide environmental and geographic distribution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 2790–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenye, T.; Vandamme, P. Diversity and significance of Burkholderia species occupying diverse ecological niches. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarini, L.; Bevivino, A.; Dalmastri, C.; Tabacchioni, S.; Visca, P. Burkholderia cepacia complex species: health hazards and biotechnological potential. Trends Microbiol. 2006, 14, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ura, H.; Furuya, N.; Iiyama, K.; Hidaka, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Matsuyama, N. Burkholderia gladioli associated with symptoms of bacterial grain rot and leaf-sheath browning of rice. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2006, 72, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.L.; Fasi, A.C.; Ramette, A.; Smith, J.J.; Hammerschmidt, R.; Sundin, G.W. Identification and onion pathogenicity of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates from the onion rhizosphere and onion field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 3121–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Santos, L.; Castro, D.B.A.; Ottoboni, L.M.M.; Park, D.; Weir, B.S.; Destéfano, S.A.L. Draft genome sequence of Burkholderia andropogonis type strain ICMP2807, isolated from Sorghum bicolor. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e00455–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cother, E.J.; Noble, D.; Peters, B.J.; Albiston, A.; Ash, G.J. A new bacterial disease of jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis) caused by Burkholderia andropogonis. Plant Pathol. 2004, 53, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; De Boer, S.H. First report of Burkholderia andropogonis causing leaf spots of Bougainvillea sp. in Hong Kong and Clover in Canada. Plant Dis. 2005, 89, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Nowak, J.; Coenye, T.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A. Diversity and occurrence of Burkholderia spp. in the natural environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 607–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.P.; Sun, X.; Zhou, L.J.; Gabriel, D.W.; Benyon, L.S.; Gottwald, T. Bacterial brown leaf spot of citrus, a new disease caused by Burkholderia andropogonis. Plant Dis. 2009, 93, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullstrup, A.J. Bacterial stripe of corn. Phytopathology. 1960, 50, 906–910. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, J.F. Pseudomonas andropogonis; In IMI Descriptions of Fungi and Bacteria; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1973; Volume 38, p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Gitaitis, R.D.; Miller, J.; Wells, H.D. Bacterial leaf spot of white clover in Georgia. Plant Dis. 1983, 67, 913–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenye, T.; Laevens, S.; Gillis, M.; Vandamme, P. Genotypic and chemotaxonomic evidence for the reclassification of Pseudomonas woodsii (Smith 1911) Stevens 1925 as Burkholderia andropogonis (Smith 1911) Gillis et al. 1995. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, J.H.; Melanson, R.A.; Rush, M.C. Burkholderia glumae: next major pathogen of rice? Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.S.; Baeta, H.; Henriques, A.F.A.; Ejtehadifar, M.; Tranfield, E.M.; Sousa, A.L.; Farinho, A.; Silva, B.C.; Cabeçadas, J.; Gameiro, P.; Silva, M.G.; Beck, H.C.; Matthiesen, R. Proteomic Landscape of Extracellular Vesicles for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Subtyping. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellei, E.; Bertoldi, C.; Monari, E.; Bergamini, S. Proteomics Disclose the Potential of Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF) as a Source of Biomarkers for Severe Periodontitis. Materials 2022, 15, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.Y.; Siu, A.F.M.; Ngai, S.M.; Che, C.M.; Tsang, J.S.H. Proteomic analysis of Burkholderia cepacia MBA4 in the degradation of monochloroacetate. Proteomics. 2007, 7, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; dos Santos, S.C.; Santos, P.M.; Coutinho, C.P.; Tyrell, J.; McClean, S.; Callaghan, M.; Sá-Correia, L. Proteomic profiling of Burkholderia cenocepacia clonal isolates with different virulence potential retrieved from a cystic fibrosis patient during chronic lung infection. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e83065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Rojas, F.U.; López-Sánchez, D.; Meza-Radilla, G.; Méndez-Canarios, A.; Ibarra, J.A.; Estrada-de Los Santos, P. The controversial Burkholderia cepacia complex, a group of plant growth promoting species and plant, animals and human pathogens. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2019, 51, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Stoychev, S.; Naicker, P.; Mamputha, S.; Khumalo, F.; Gerber, I.; van der Westhuyzen, C.; Jordan, J. Universal unbiased pre-MS clean-up using magnetic HILIC micro-particles for SPE. 2017. Available online: https://www.bioinfor.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Universal-unbiased-pre-ms-clean-up-using-magnetic-hilic.pdf. (accessed on 14 August 2017).

- Kapoor, K.N.; Barry, D.T.; Rees, R.C.; Dodi, L.A.; McArdle, S.E.B.; Creaser, C.S.; Bonner, P.L.R. Estimation of peptide concentration by a modified bicinchoninic acid assay. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 393, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundry, R.L.; White, M.Y.; Murray, C.I.; Kane, L.A.; Fu, Q.; Stanley, B.A.; Van Eyk, J.E. Preparation of proteins and peptides for mass spectrometry analysis in a bottom-up proteomics workflow. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2010, 90, 10.25.1–10.25.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.uniprot.org (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Available online: https://string-db.org (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Kuhn, M.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Minguez, P.; Doerks, T.; Stark, M.; Muller, J.; Bork, P.; Jensen, J.J.; von Mering, C. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, M.; Cañas, B.; Gallardo, J.M. The sarcoplasmic fish proteome: pathways, metabolic networks and potential bioactive peptide for nutritional inferences. J. Proteomics. 2013, 78, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.C. DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 635–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champoux, J.J. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 369–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, K.D.; Berger, J.M. Structure, molecular mechanisms, and evolutionary relationships in DNA topoisomerases. Ann. Rev. Biophy. Biomol. Struct. 2004, 33, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A. DNA gyrase as a drug target. Trends Microbiol. 1997, 5, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdluli,K. ; Ma, Z. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA gyrase as a target for drug discovery, Infect. Disord. Drug Targets. 2007, 7, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, T.; Fukuda, M.; Kawakamis, H.; Hirano, H.; Kamiya, S.; Yamamoto, T. The Listeria monocytogenes DnaK chaperone is required for stress tolerance and efficient phagocytosis with macrophages. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1999, 4, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, A.; Tomoyasu, T.; Matsui, H.; Yamamoto, T. The DnaK/DnaJ chaperone machinery of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium is essential for invasion of epithelial cells and survival within macrophages, leading to systemic infection. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rocha Dias, S.; Friedlos, F.; Light, Y.; Springer, C.; Workman, P.; Marais, R. Activated B-RAF is an Hsp90 client protein that is targeted by the anticancer drug 17-Allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 10686–10691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, M.V.; Workman, P. Targeting of multiple signaling pathways by heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitors. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2006, 13, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolska, K.I.; Bugajska, E.; Jurkiewicz, D.; Kuć, M.; Jŏźwik, A. Antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli dnaK and dnaJ mutants. Microb. Drug Resist. 2004, 6, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitesell, L.; Bagatell, R.; Falsey, R. The stress response: implications for the clinical development of Hsp90 inhibitors. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2003, 3, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, B.; Allan, E.; Coates, A.R.M. Stress wars: the direct role of host and bacterial molecular chaperones in bacterial infection. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 3693–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, J.A.; Luzardo, Y.; Burne, R.A. Physiologic effects of forced down-regulation of dnaK and groEL expression in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 1582–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, T.F.; O’Toole, G.A. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends in Microbiol. 2001, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BurmØlle, M.; Webb, J.S.; Rao, D.; Hansen, L.H.; SØrensen, S.J.; Kjelleberg, S. Enhanced biofilm formation and increased resistance to antimicrobial agents and bacterial invasion are caused by synergistic interactions in multispecies biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 3916–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yura, T; Nakahigashi, K. Regulation of the heat-shock response. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1999, 2, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P. , Xue, J., Chen, X; Ji, X. DnaK-Mediated Protein Deamidation: a Potential Mechanism for Virulence and Stress Adaptation in Cronobacter sakazakii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00505-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberto, J. , Bonnefoy, E., Mouray, E., Pellegrini, O., Wikström, P.M., Rouvière-Yaniv, J. The Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S16 is an endonuclease. Mol. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, C.F. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Ann. Rev. Cell Biol. 1992, 8, 67–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, E.; Hunke, S. ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) transport systems: functional and structural aspects of the ATP-hydrolyzing subunits/domains. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fath, M.J.; Kolter, R. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1993, 57, 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, J.I.; Eady, E.A.; Cove, J.H.; Cunliffe, W.J.; Baumberg, S.; Wootton, J.C. Inducible erythromycin resistance in staphylococci is encoded by a member of the ATP-binding transport super-gene family. Mol. Microbiol. 1990, 4, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Lopez, C.; Baer, M.T.; Groisman, E.A. Molecular genetic analysis of a locus required for resistance to antimicrobial peptides in Salmonella typhimurium. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 4053–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, J. Reviving the antibiotic miracle? Science. 1994, 264, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelicano, H.; Martin, D.S.; Xu, R.H.; Huang, P. Glycolysis inhibition for anticancer treatment. Oncogene. 2006, 25, 4633–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O.; Wind, F.; Negelein, E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J. Gen. Physiol. 1927, 8, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. Warburg report on the metabolism of tumors. J. Chem. Educ. 1930, 7, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L.; Artemov, D.; Bedi, A.; Bhujwalla, Z.; Chiles, K.; Feldser, D.; Laughner, E.; Ravi, R.; Simons, J.; Taghavi, P.; Zhong, H. ‘The metabolism of tumours’: 70 years later. Novartis Foundation Symp. 2001, 240, 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Pinedo, C.; Ruiz-Ruiz, C.; de Almodóvar, C.R.; Palacios, C.; López-Rivas, A. Inhibition of glucose metabolism sensitizes tumor cells to death receptor-triggered apoptosis through enhancement of death-inducing signaling complex formation and apical procaspace-8 processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 12759–12768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izyumov, D.S.; Avetisyan, A.V.; Pletjushkina, O.Y.; Sakharov, D.V.; Wirtz, K.W.; Chernyak, B.V.; Skulachev, P.V. “Wages of Fear”: transient threefold decrease in intracellular ATP level imposes apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2004, 1658, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.H.; Pelicano, H.; Zhou, Y.; Carew, J.S.; Feng, L.; Bhalla, K.N.; Keating, J.; Huang, P. Inhibition of glycolysis in cancer cells: a novel strategy to overcome drug resistance associated with mitochondrial respiratory defect and hypoxia. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, C.; Bessman, S.P. Anabolic regulation of gluconeogenesis by insulin in isolated rat hepatocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1985, 242, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, Y.; Deval, C.; de la Foye, A.; Masson, L.; Gannon, V.; Harel, J.; Martin, C.; Desvaux, M.; Forano, E. The gluconeogenesis pathway is involved in maintenance of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in bovine intestinal content. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e98367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darie-Ion, L.; Jayathirtha, M.; Hitruc, G.E.; Zaharia, M.-M.; Gradinaru, R.V.; Darie, C.C.; Pui, A.; Petre, B.A. A proteomic approach to identify zein proteins upon eco-friendly ultrasound-based extraction. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, P. , Camacho, I., Câmara, J.S.; Perestrelo, R.. Urinary proteomic/peptidomic biosignature of breast cancer patients using 1D SDS-PAGE combined with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Separations. 2023, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isani, G. , Bellei, E., Rudelli, C., Cabbri, R., Ferlizza, E. Andreani, G. SDS-PAGE-Based Quantitative assay of hemolymph proteins in honeybees: Progress and Prospects for Field Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agregán, R.; Echegaray, N.; López-Pedrouso, M.; Kharabsheh, R.; Franco, D.; Lorenzo, J.M. Proteomic advances in milk and dairy products. Molecules. 2021, 26, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordwell, S.J. , Nouwens, A.S.; Walsh, B.J. Comparative proteomics of bacterial pathogens. PROTEOMICS: International Edition, 1(4), 2001; 461-472. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, S. , Staes, A., Deborggraeve, S.; Gevaert, K. Targeted proteomics for studying pathogenic bacteria. Proteomics. 2019, 19, 1800435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).