Submitted:

01 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method and Experiment

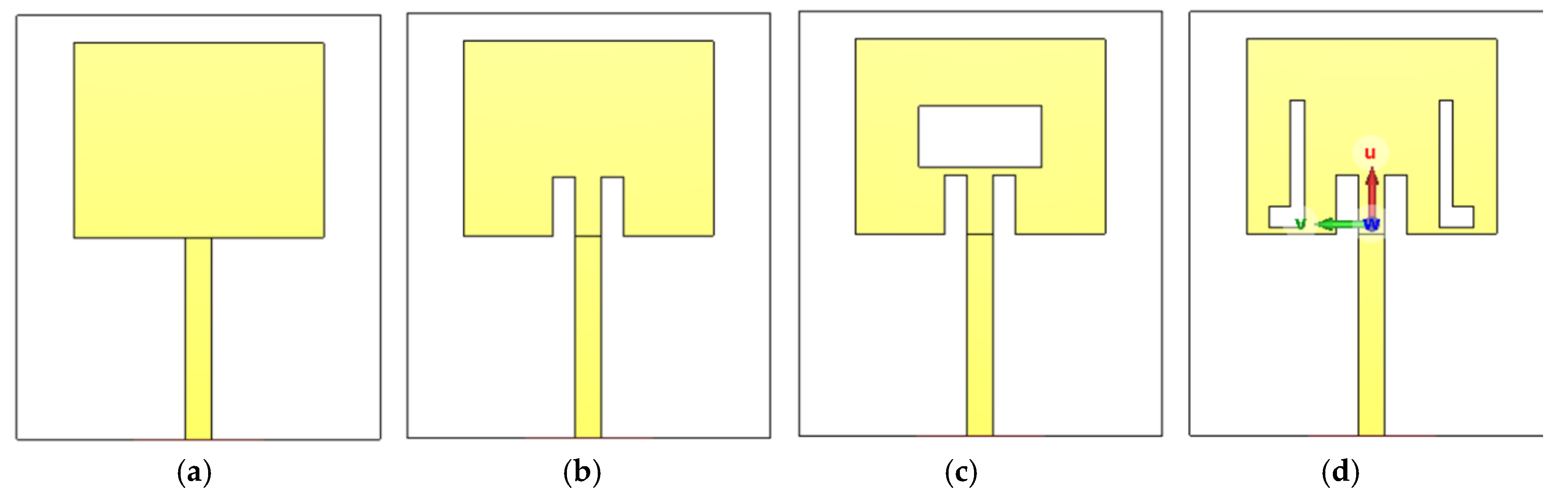

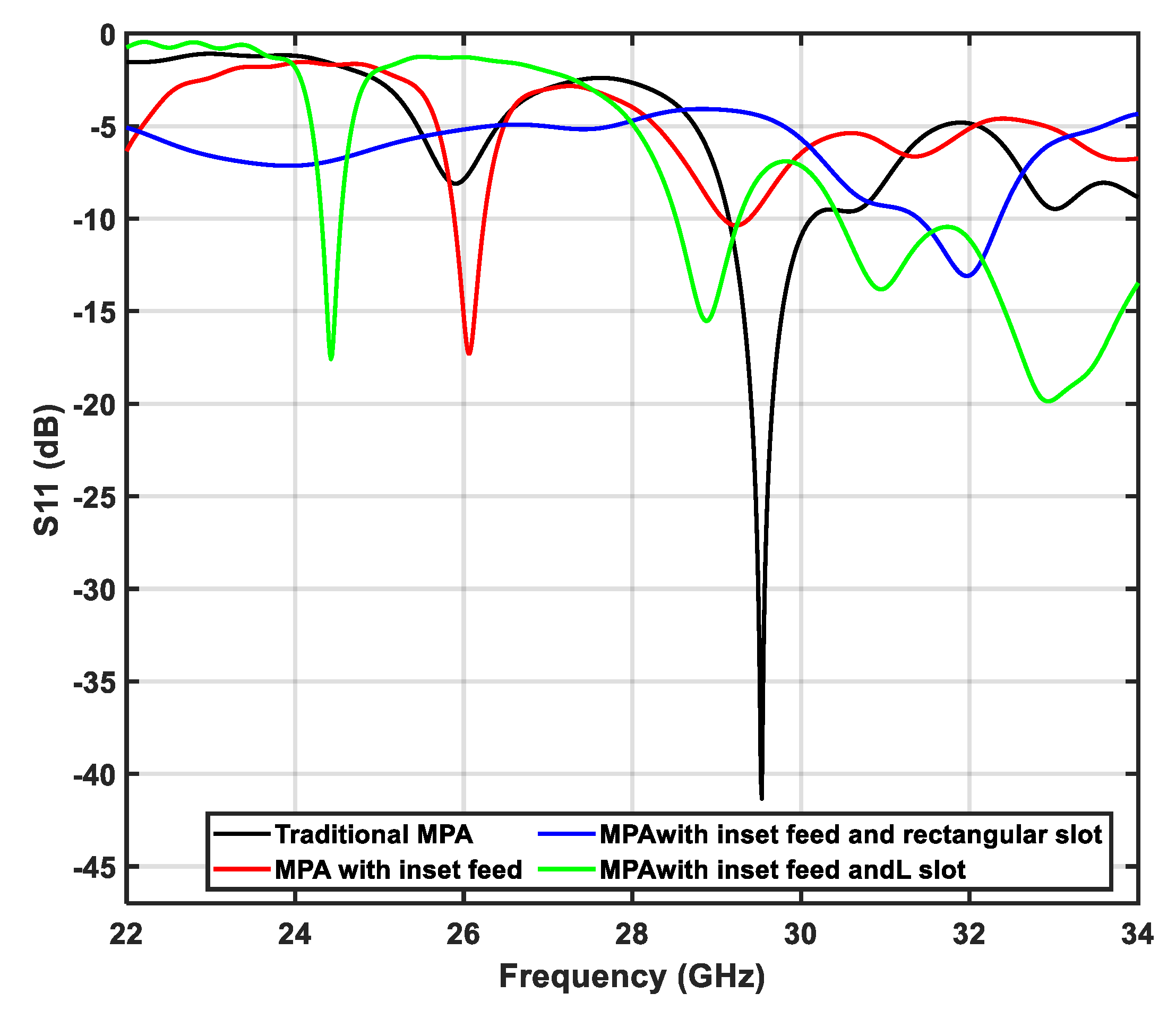

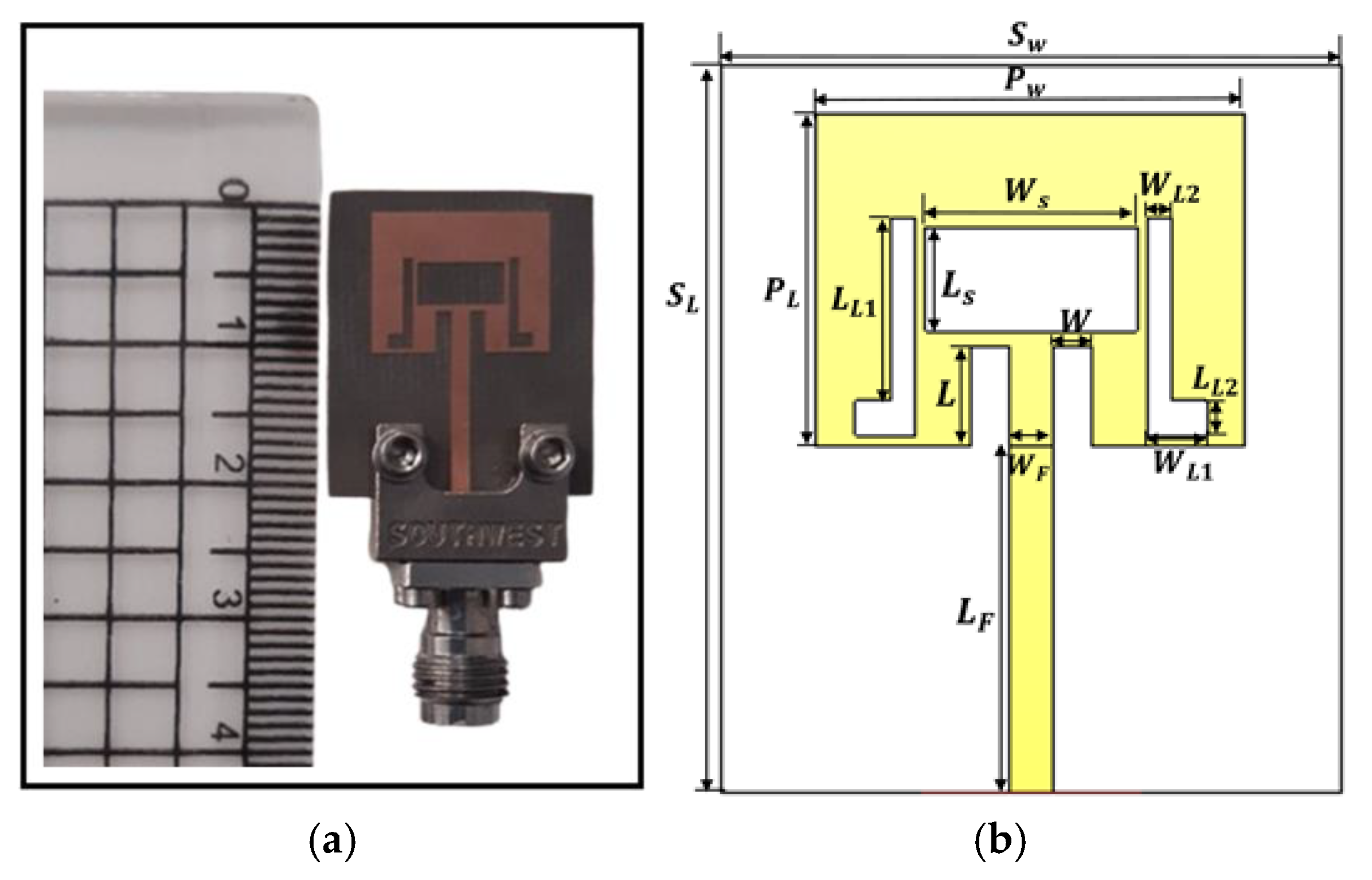

2.1. Design of the Proposed Single Antenna

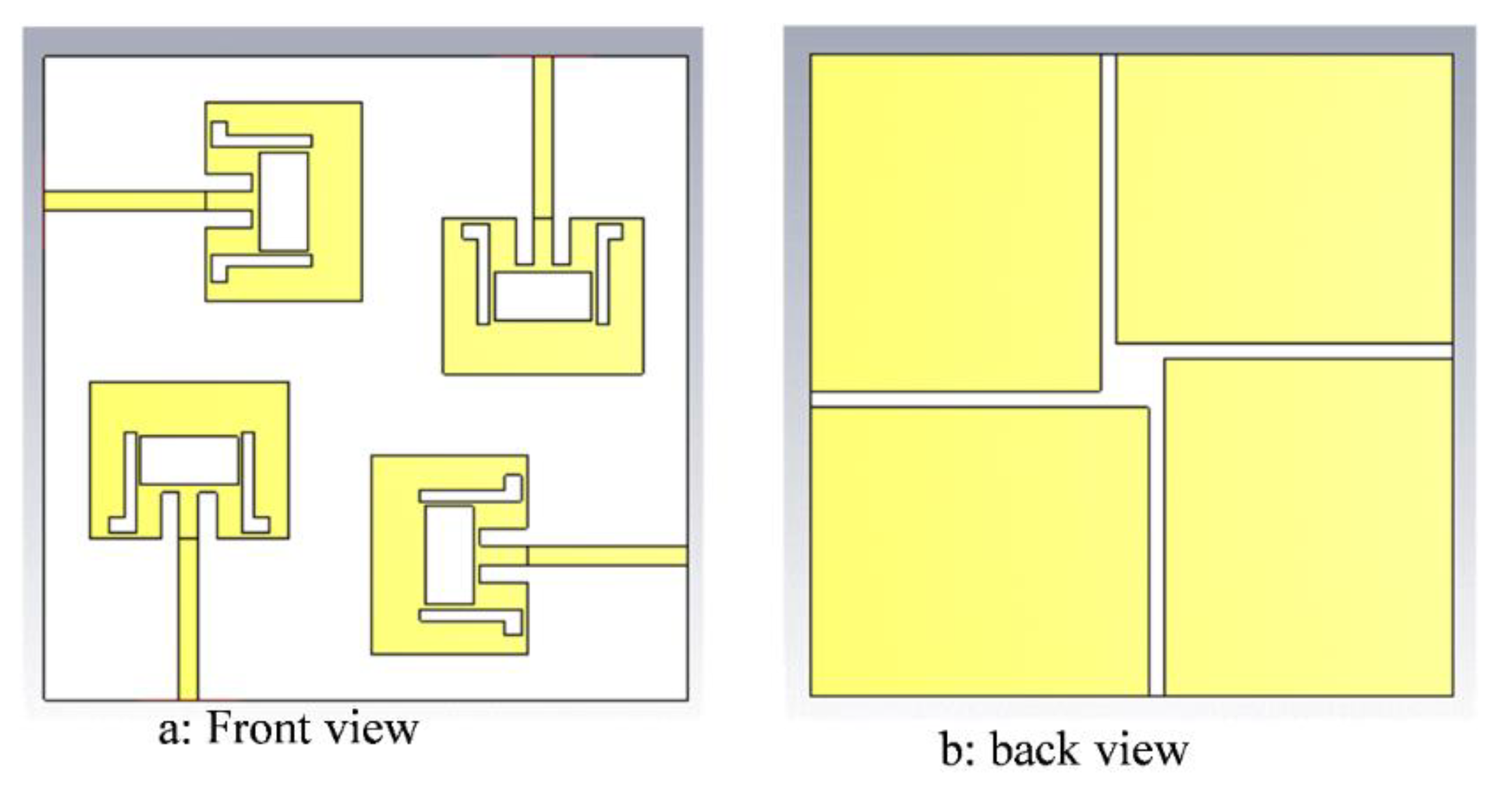

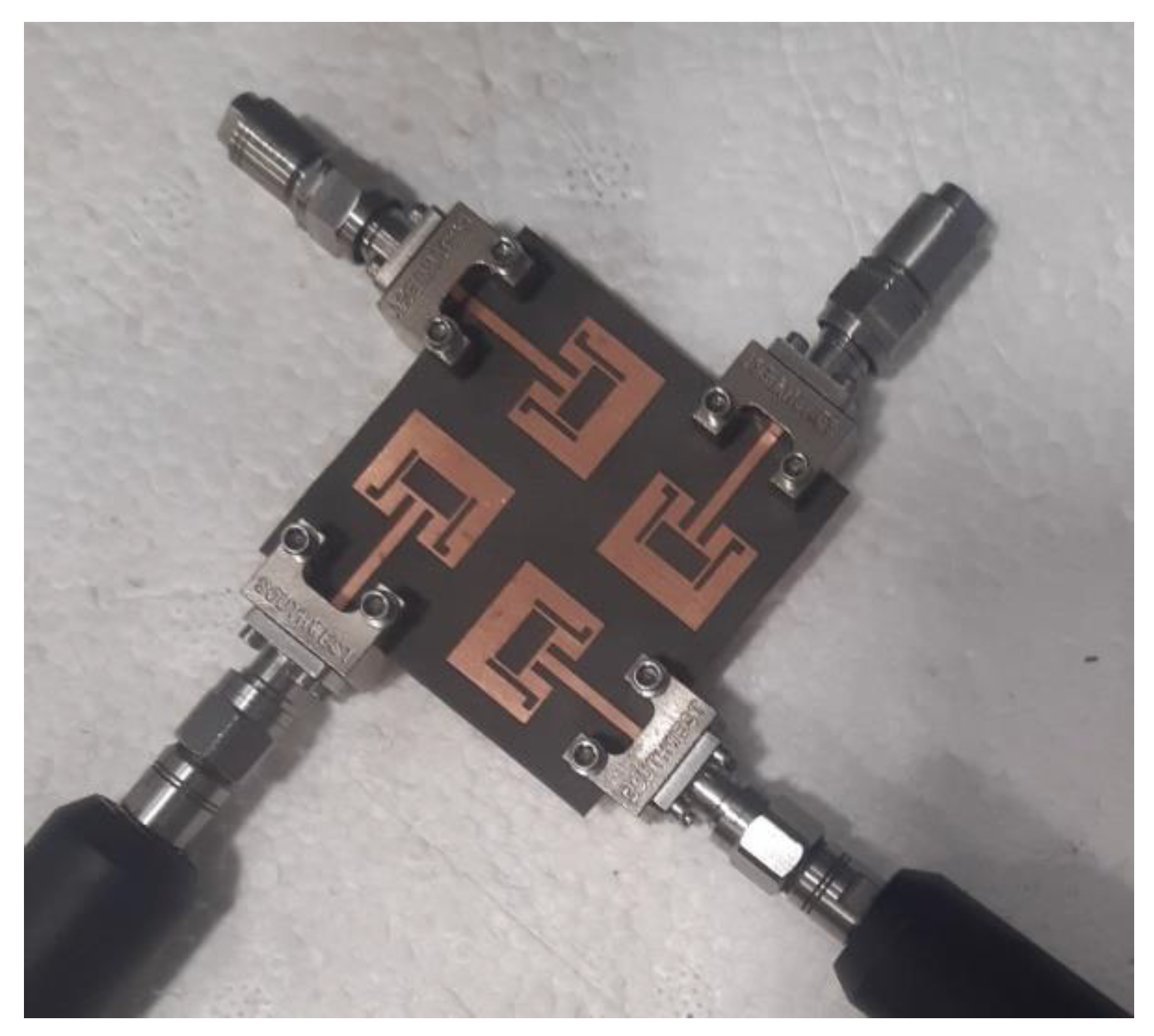

2.2. Design of the Proposed 4×4 MIMO Configuration

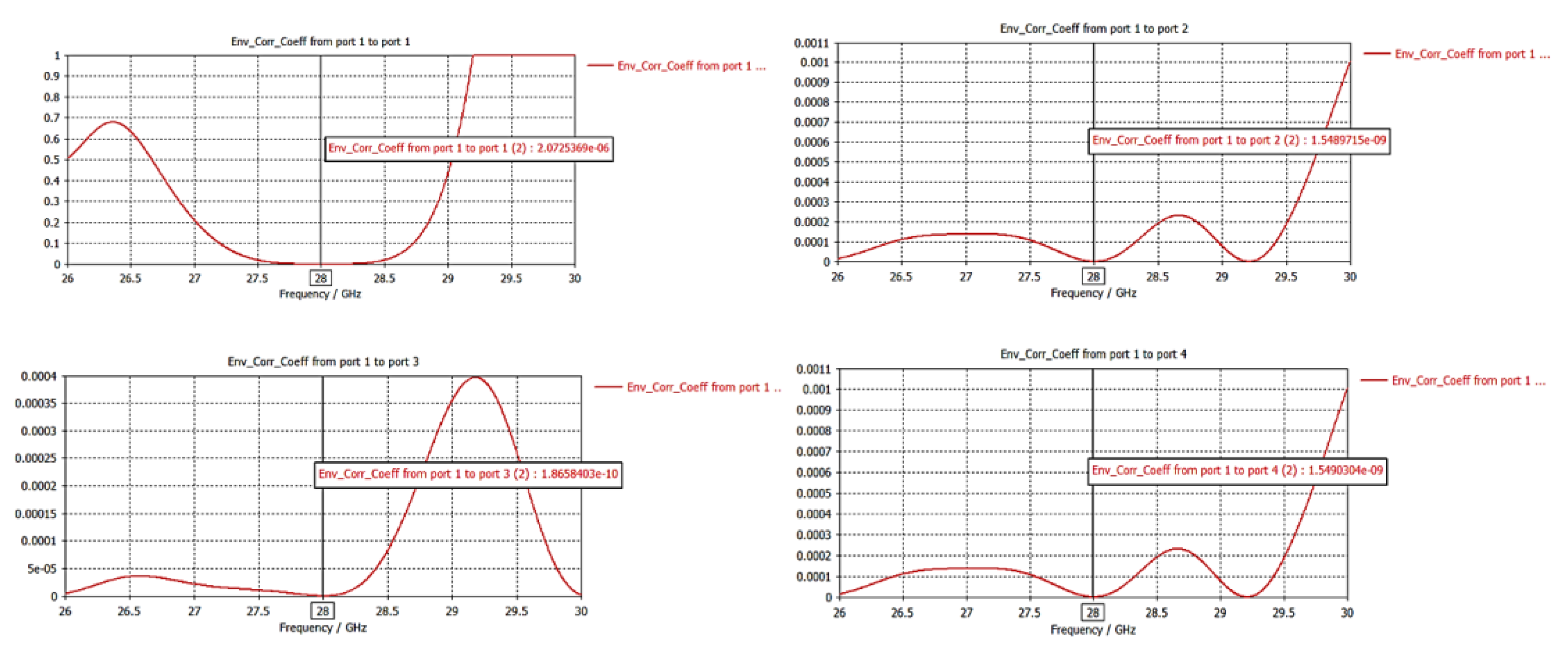

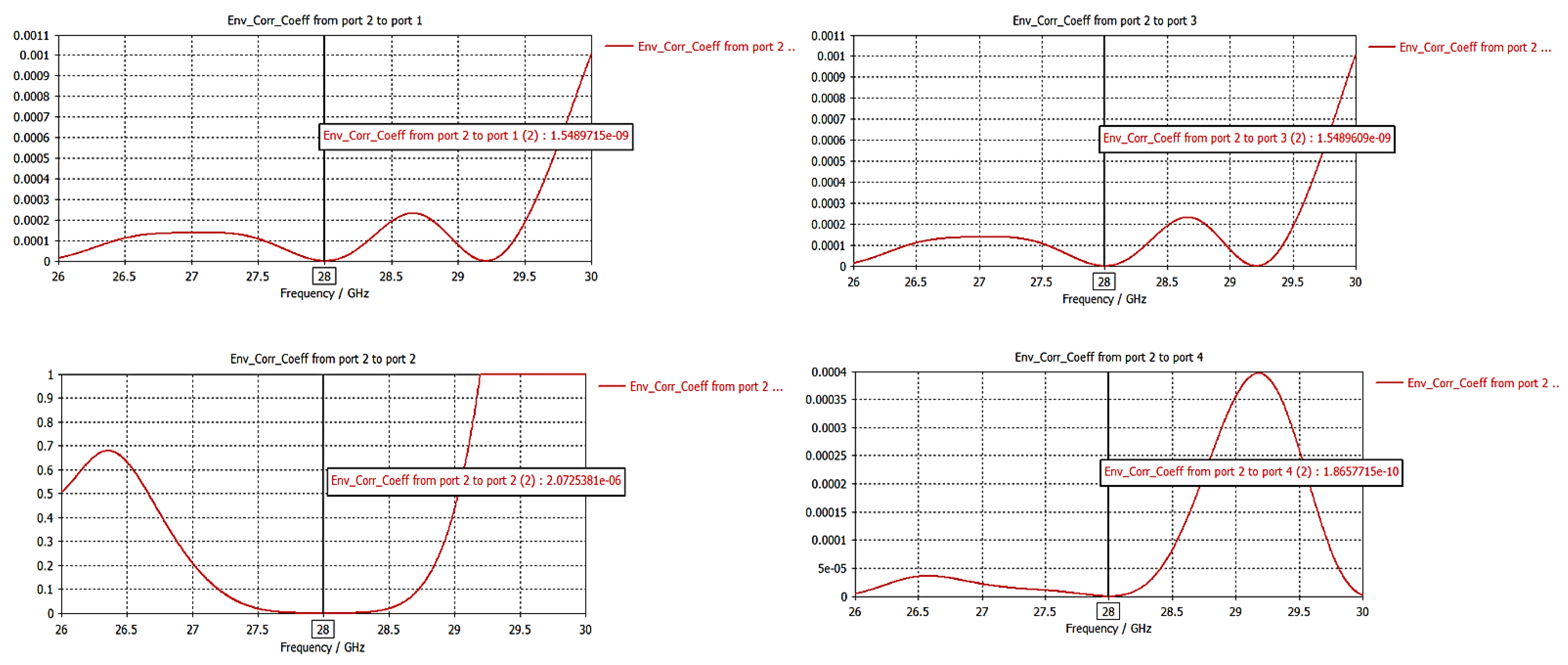

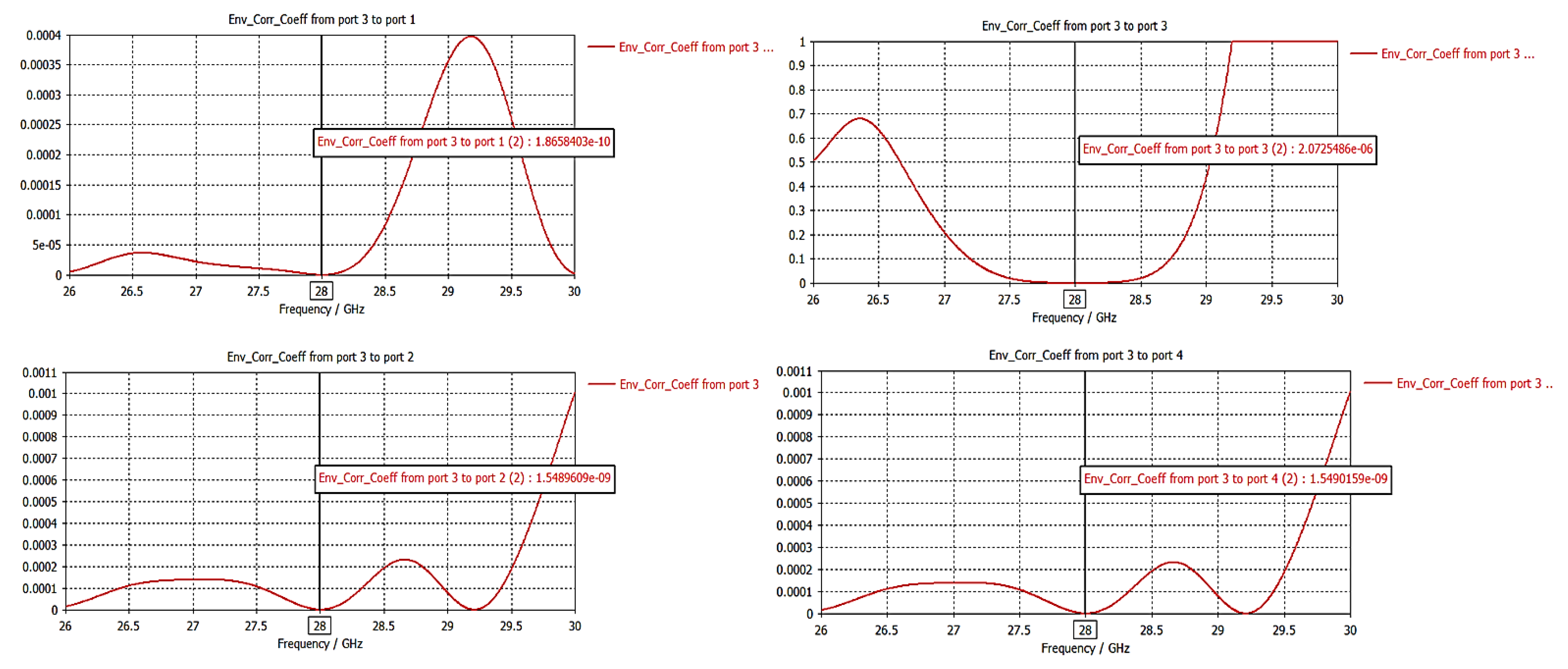

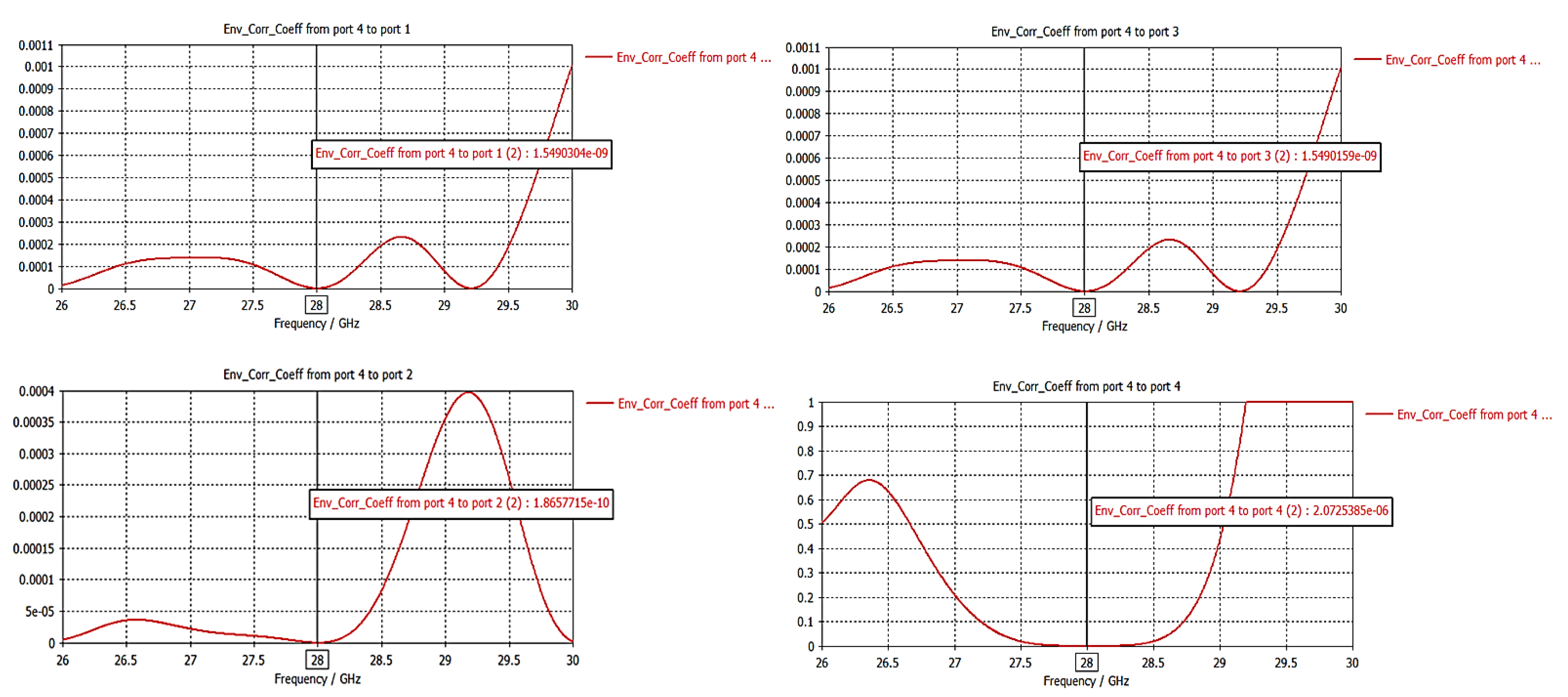

2.2.1. Envelope Correlation Coefficient (ECC)

2.2.2. Diversity Gain (DG)

2.2.3. Total Active Reflection Coefficient (TARC)

2.2.4. Mean Effective Gain (MEG)

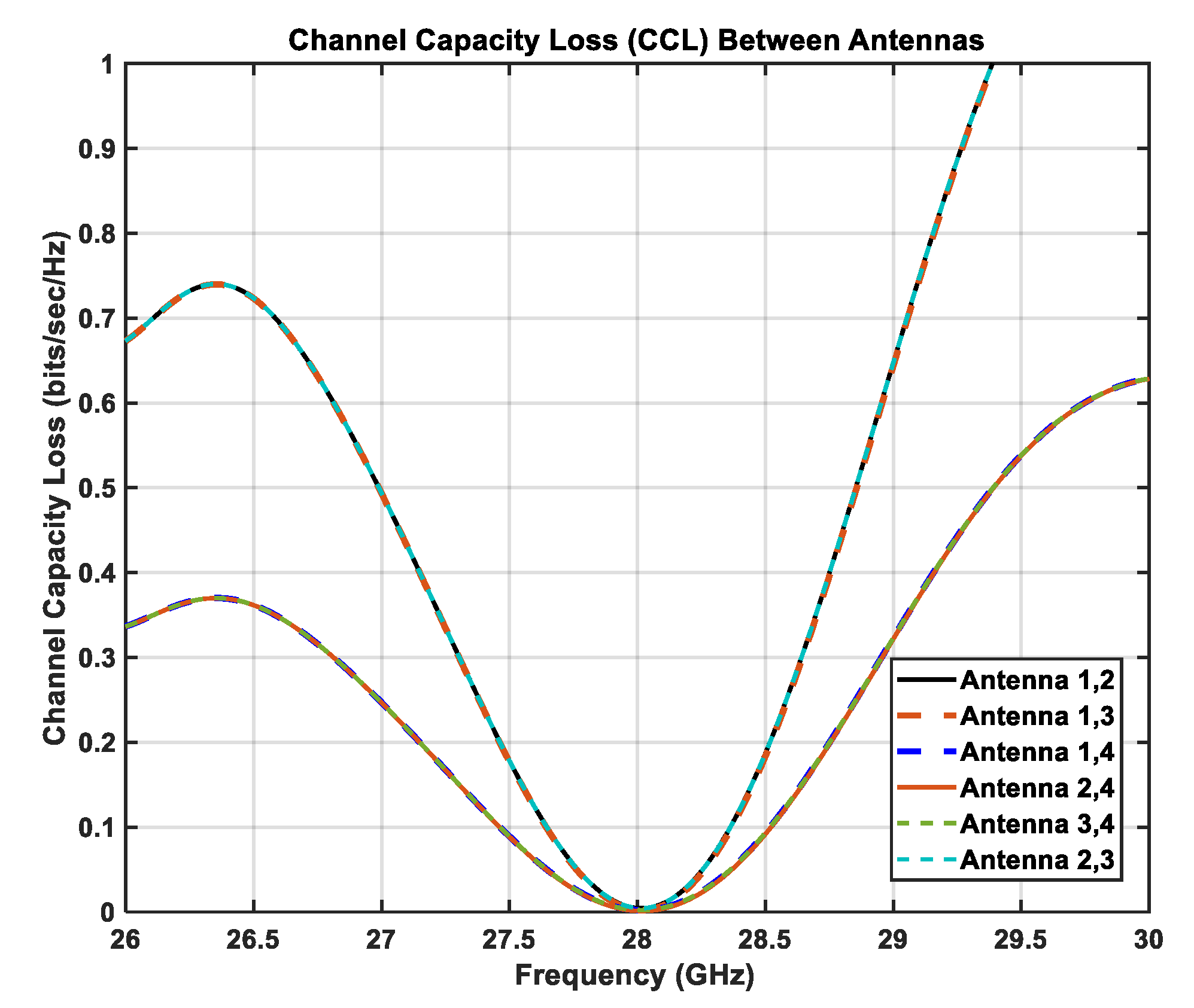

2.2.5. Channel Capacity Loss (CCL)

2.2.6. Multiplexing Efficiency (ME)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proposed Single Antenna Configuration

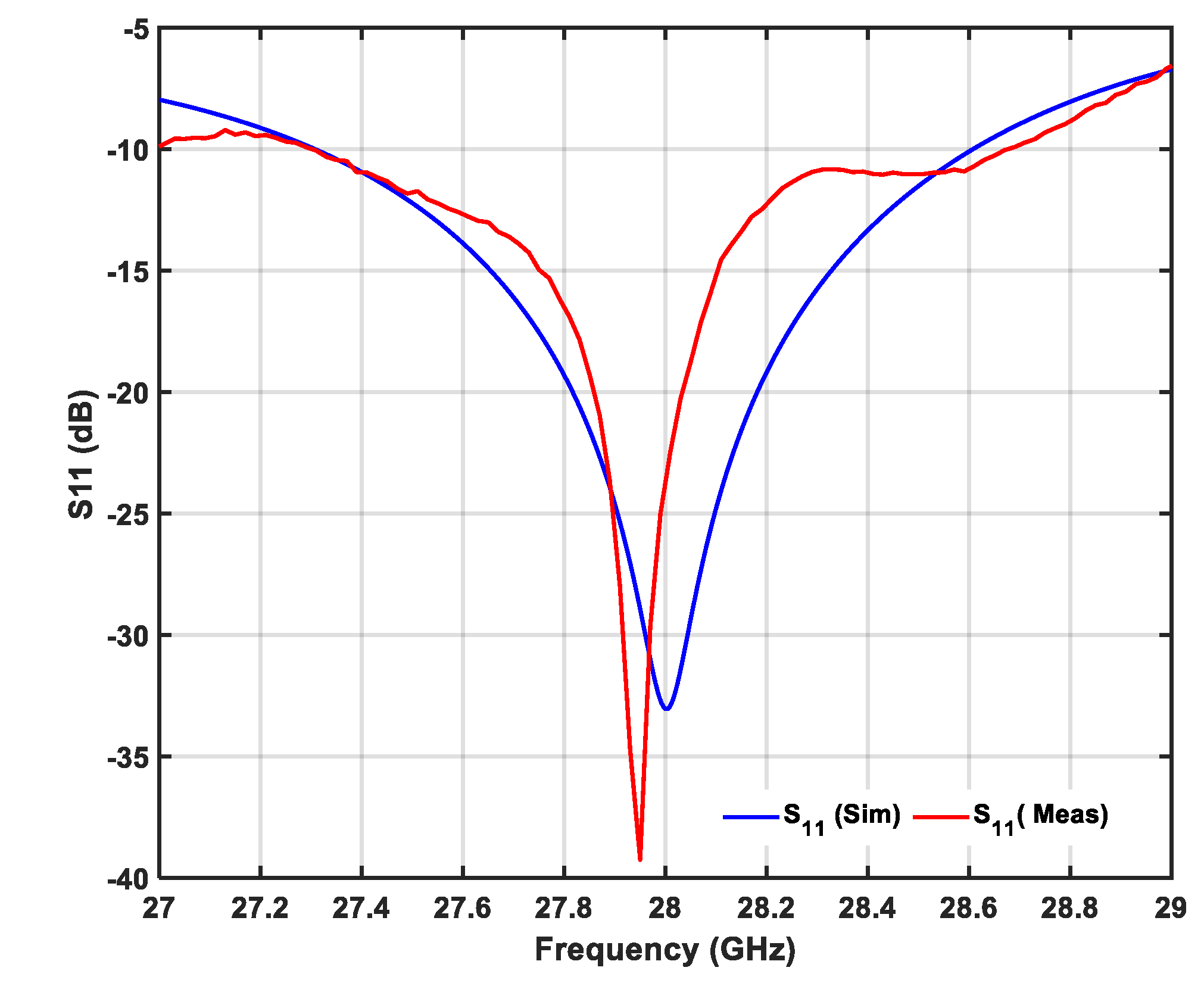

3.1.1. Return Loss ()

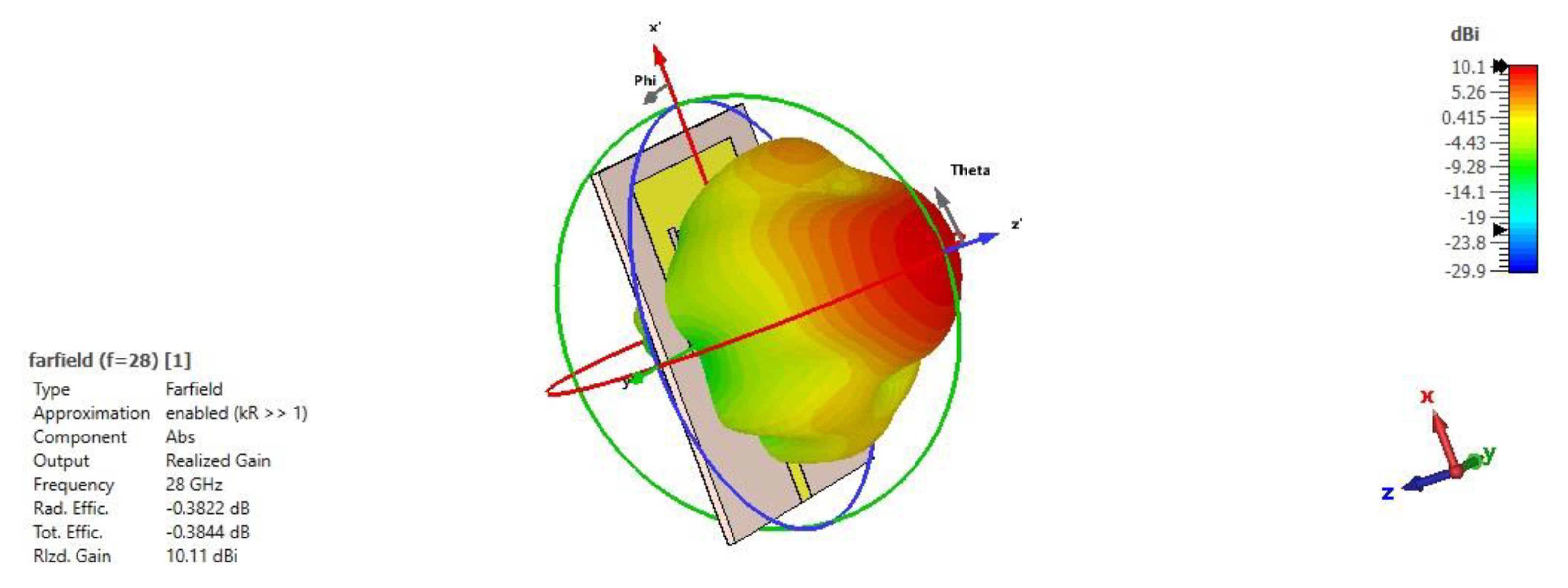

3.1.2. Gain

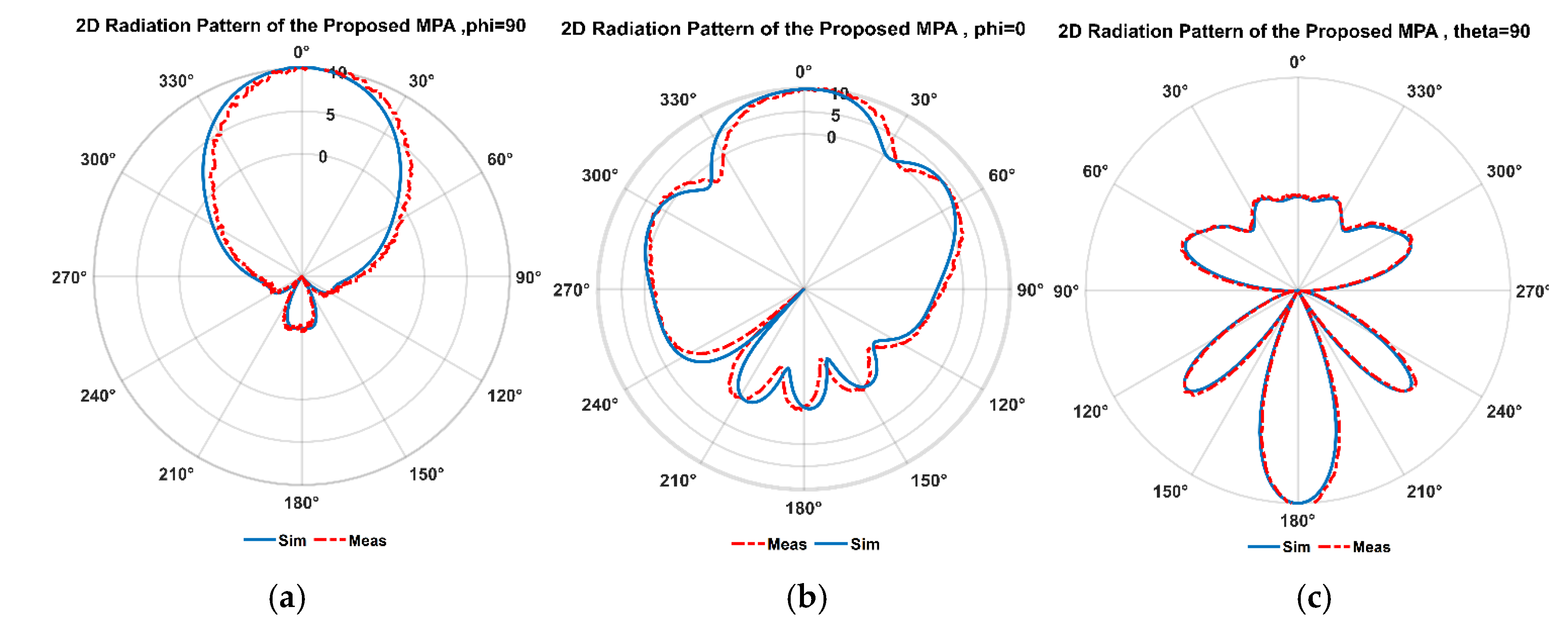

3.1.3. Radiation Pattern

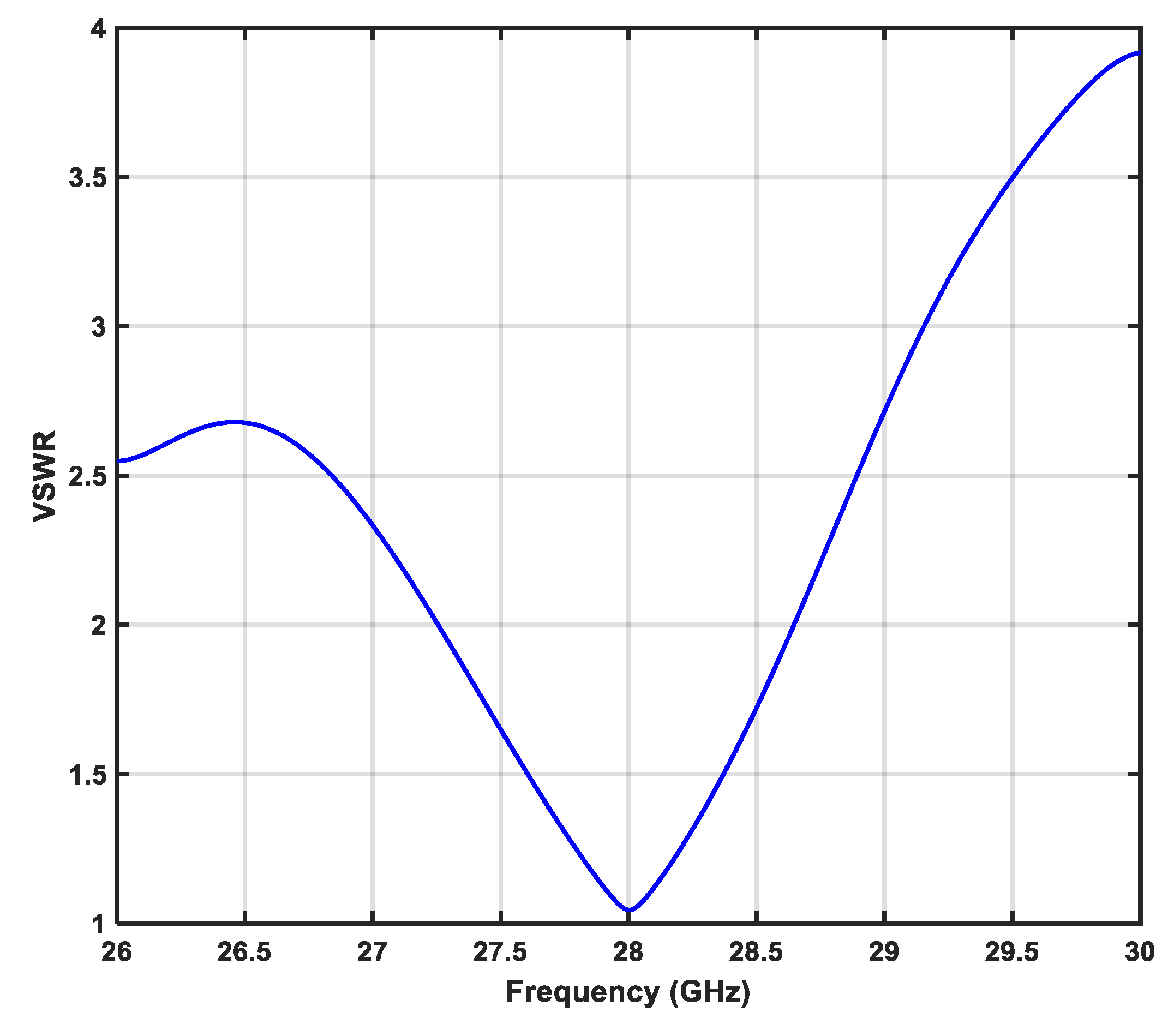

3.1.4. Voltage Standing Wave Ratio

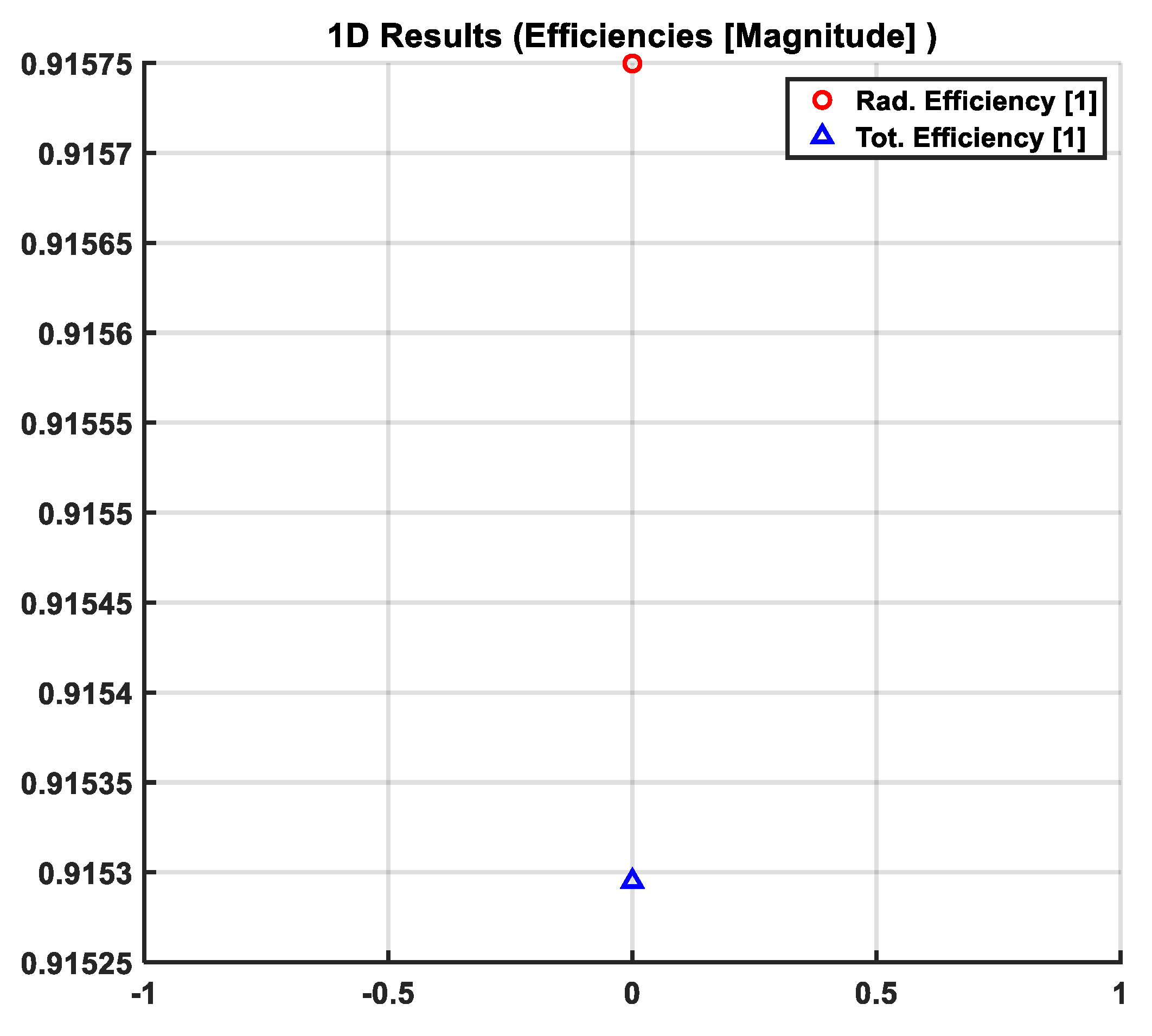

3.1.5. Efficiency

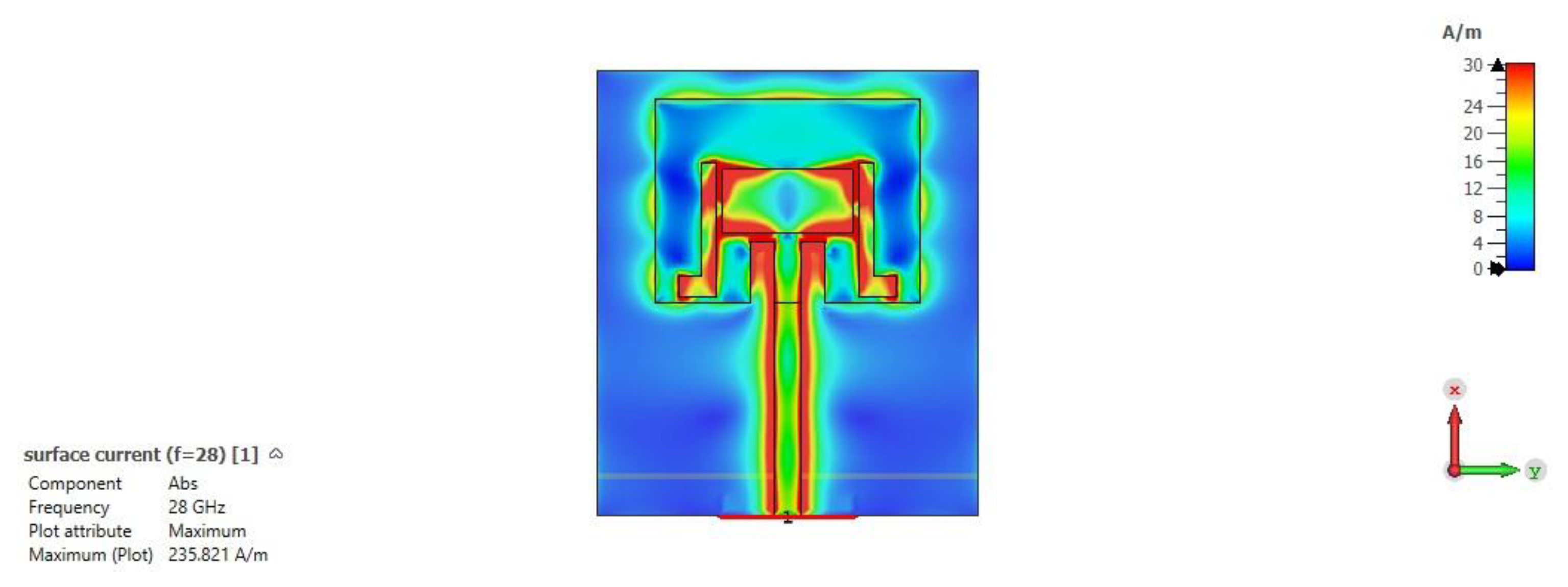

3.1.6. Surface Current

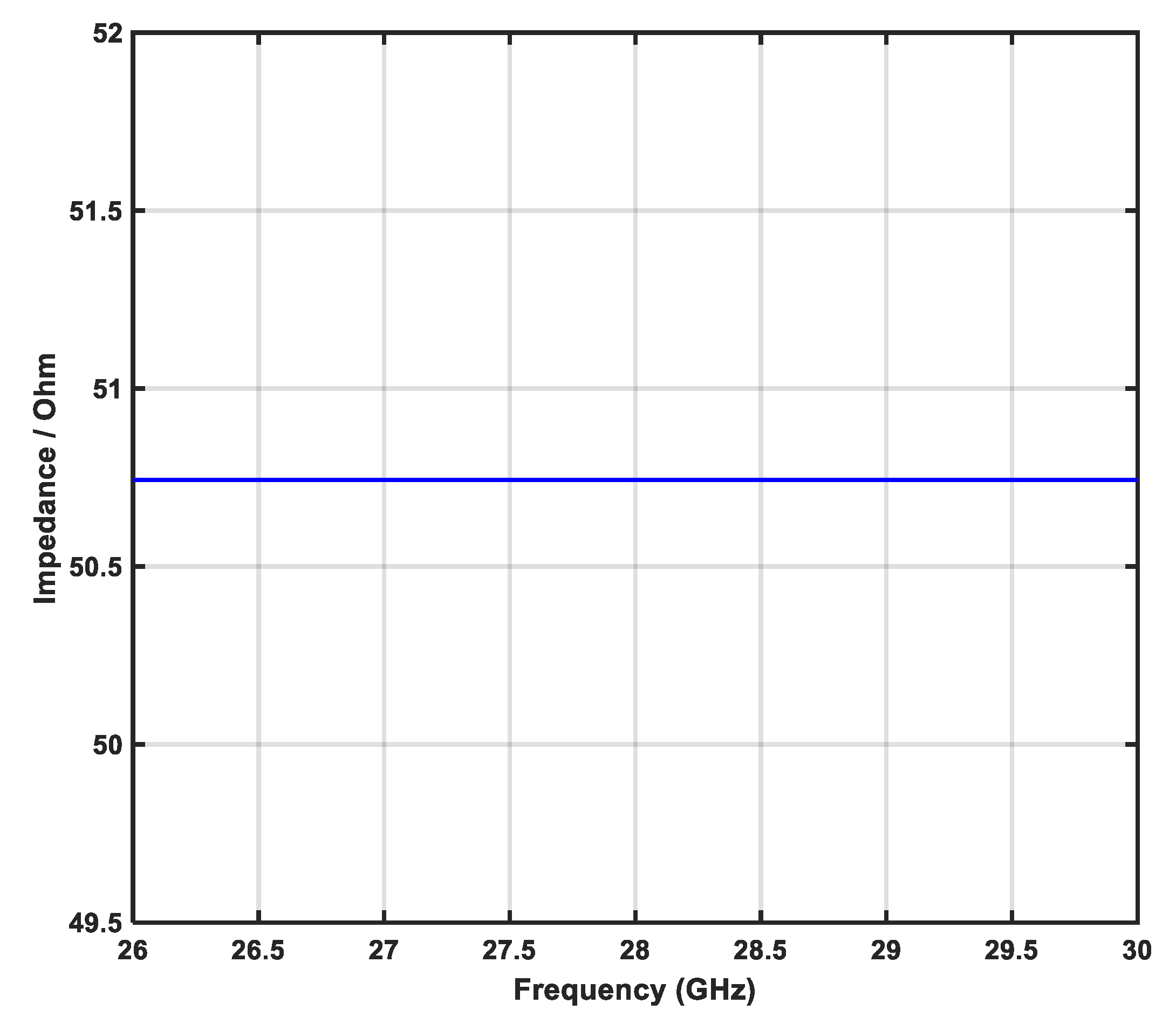

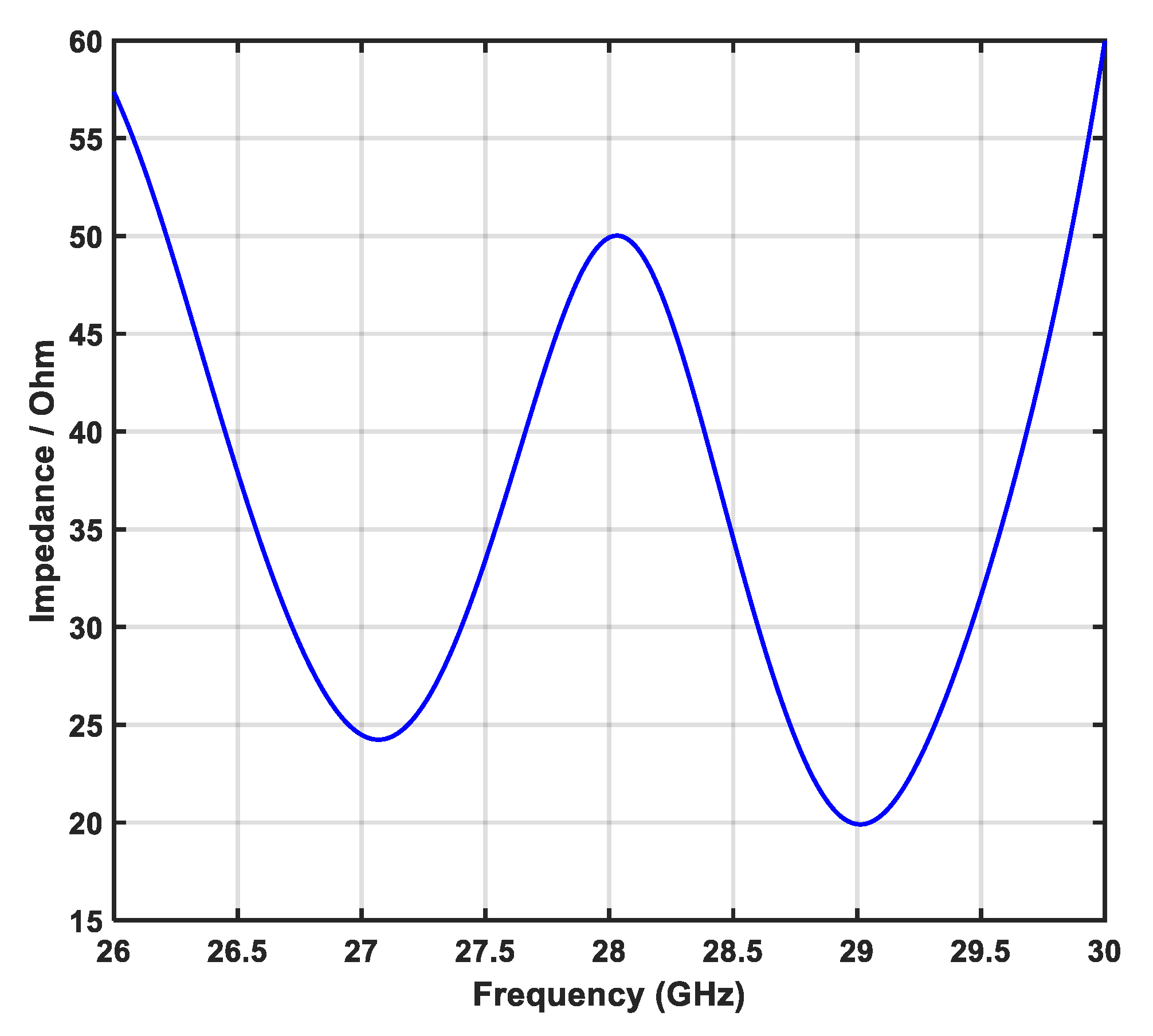

3.1.7. Reference Impedance

3.1.8. Input Impedance

3.2. Proposed MIMO

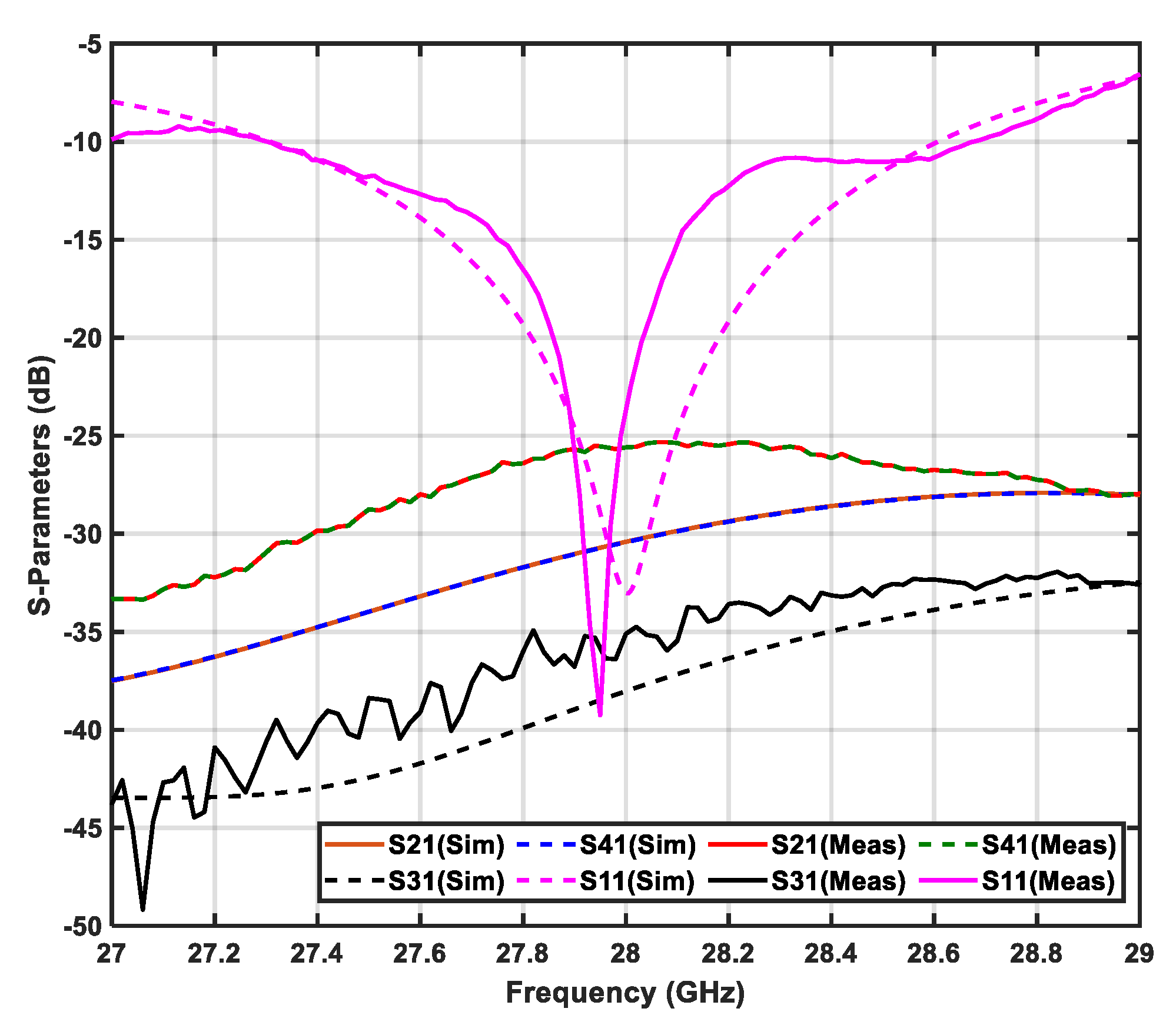

3.2.1. Reflection Coefficients (S-Parameters)

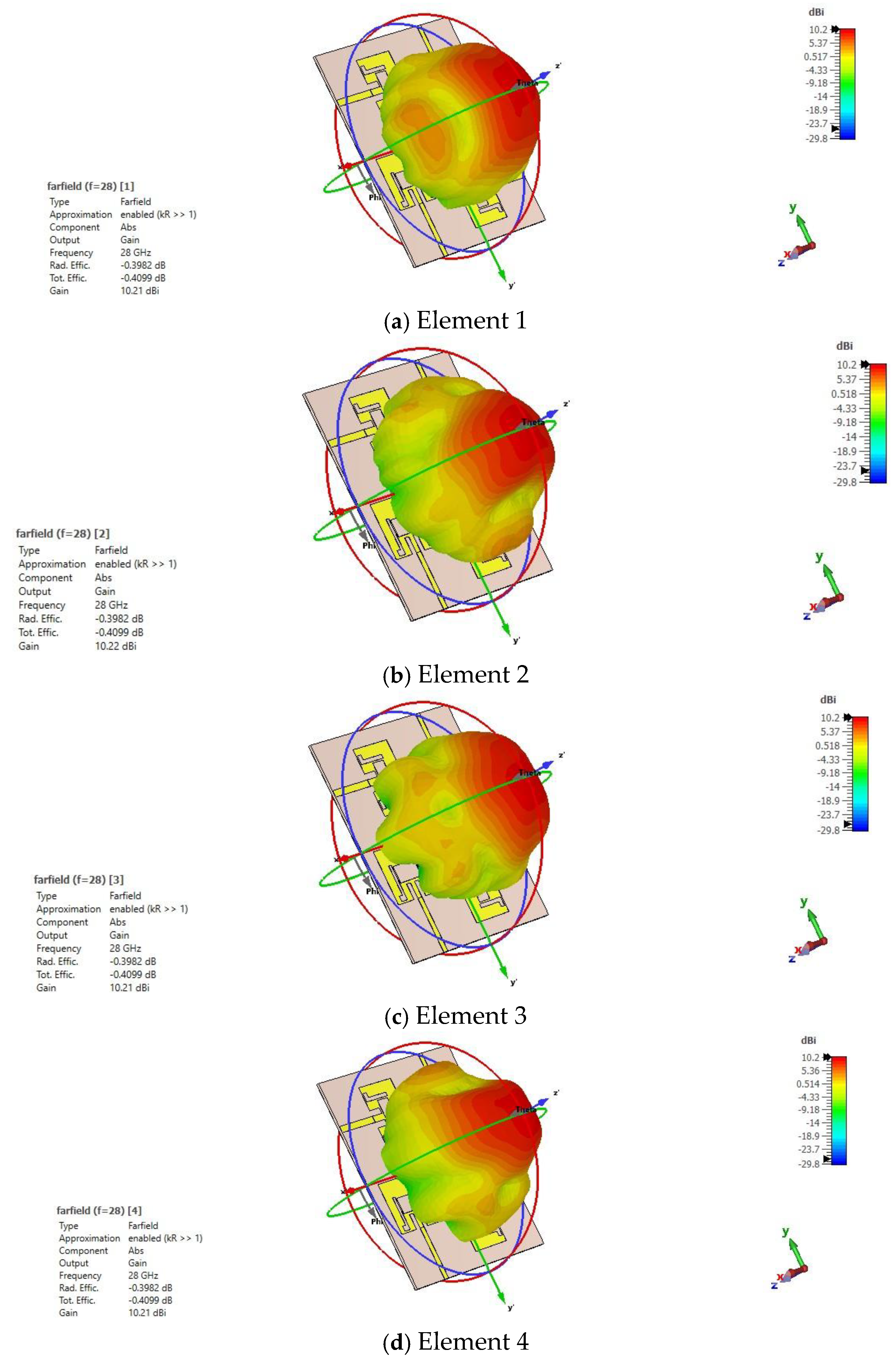

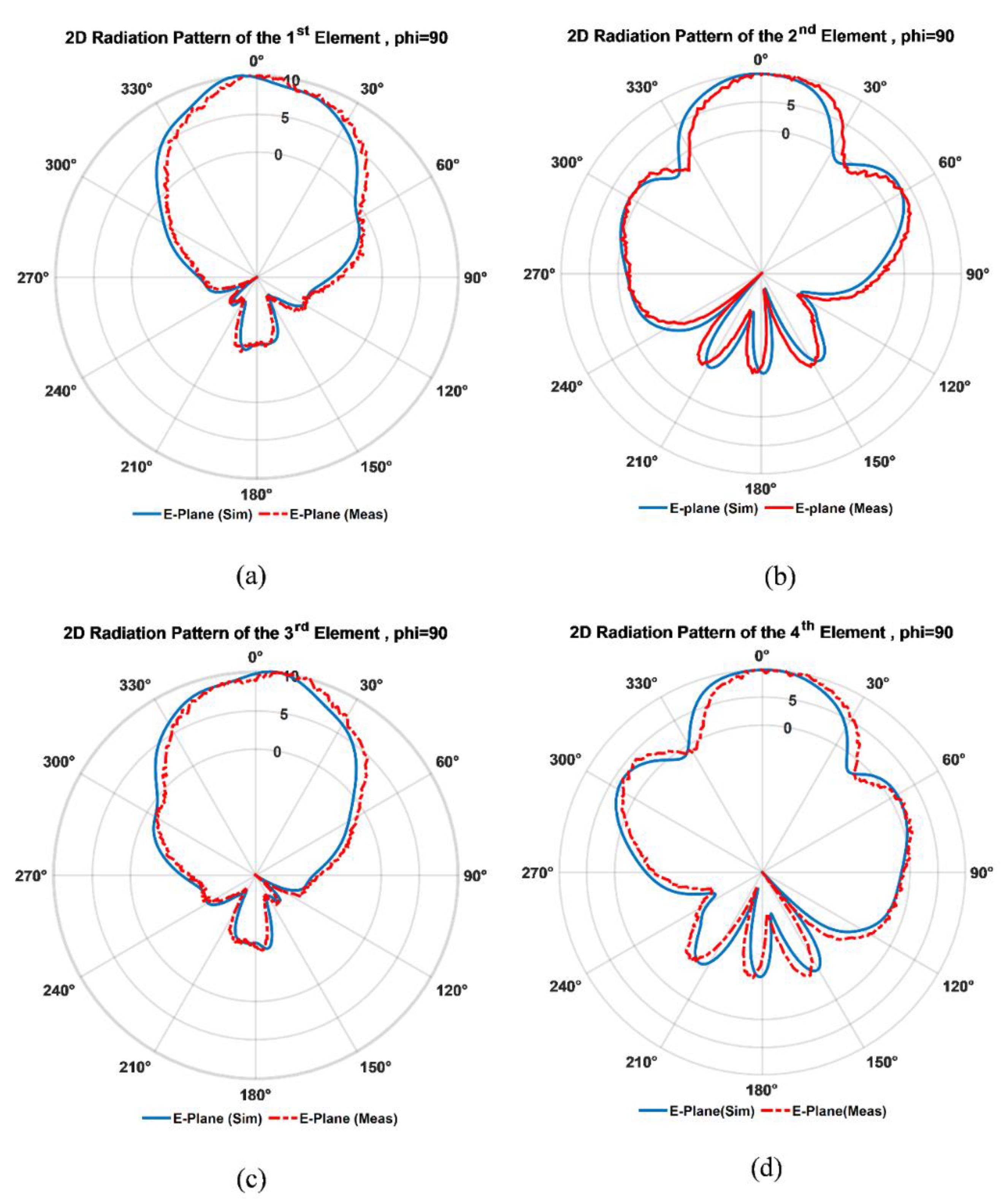

3.2.2. D-Radiation Pattern and Gain

3.2.3. Envelope Correlation Coefficient (ECC)

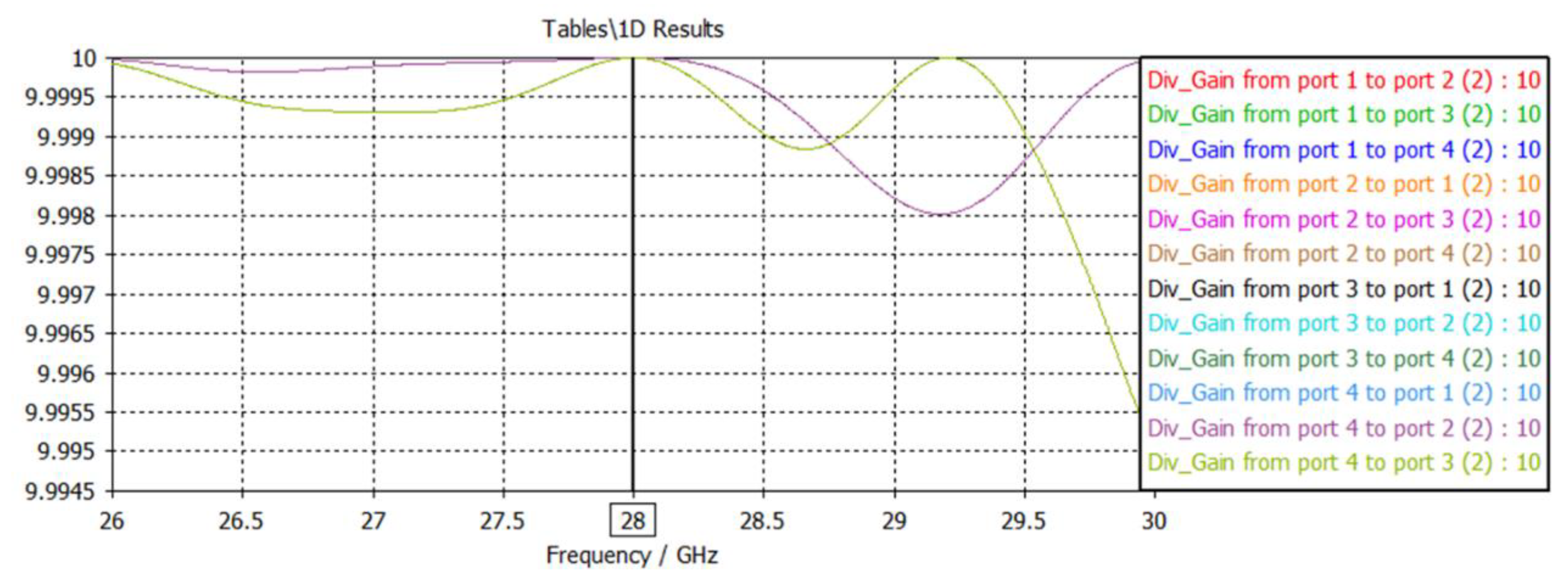

3.2.4. Diversity Gain

3.2.5. Total Active Reflection Coefficient (TARC)

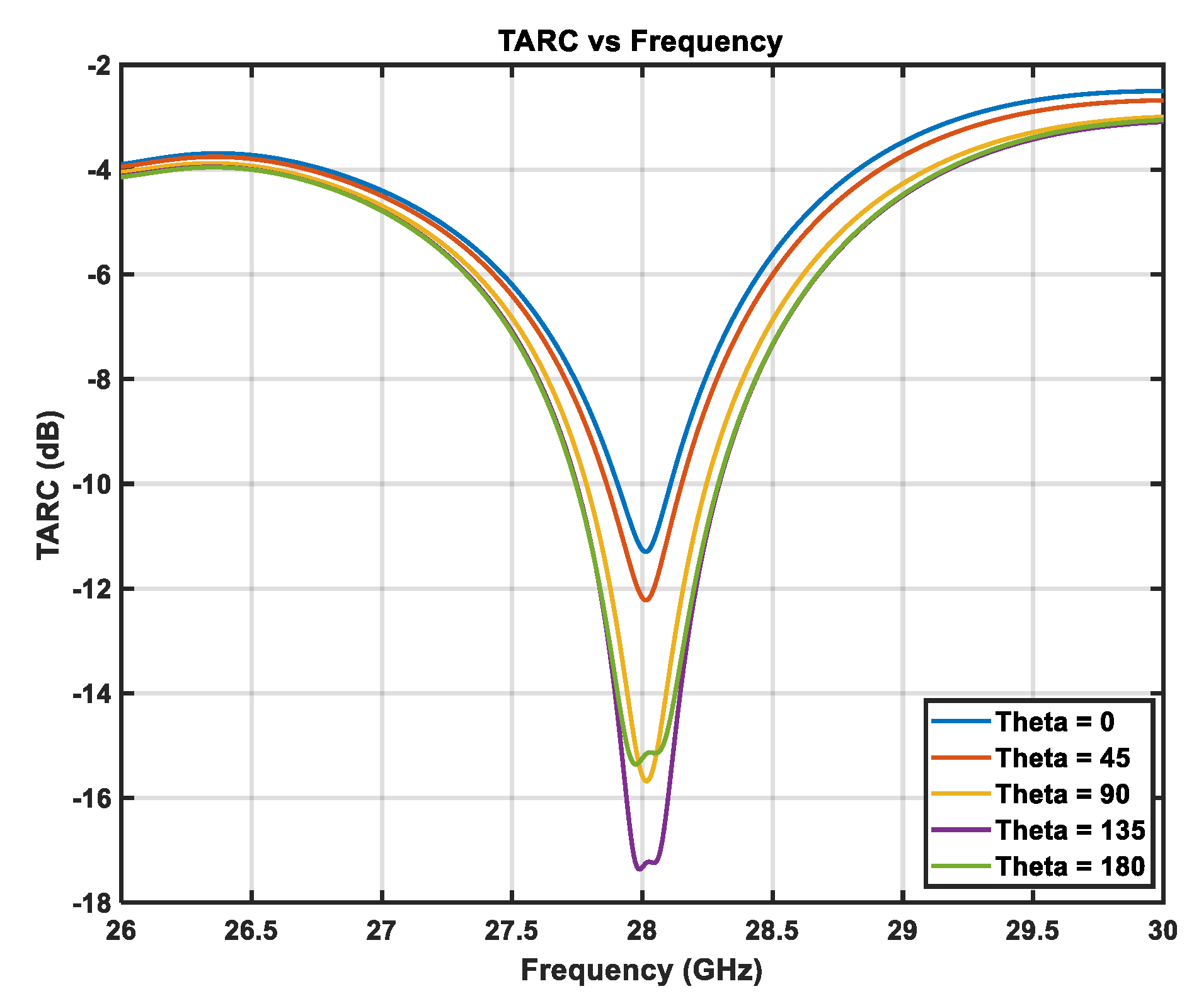

3.2.6. Mean Effective Gain (MEG)

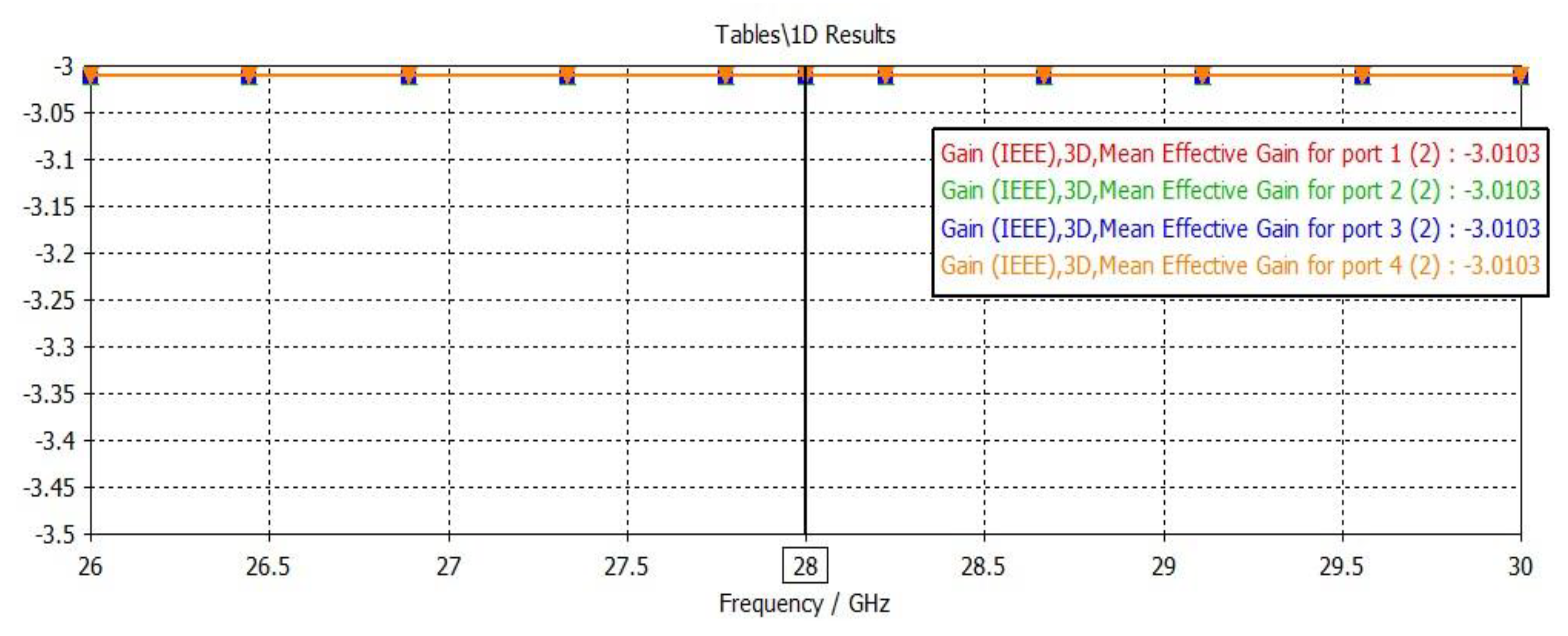

3.2.7. Channel Capacity Loss (CCL)

3.2.8. Multiplexing Efficiency

4. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Alwakeel, A. M. El-Rifaie, G. Moustafa, A. M. Shaheen, “Newton Raphson based optimizer for optimal integration of FAS and RIS in wireless systems,” Results in Engineering, Volume 25, 2025, 103822, ISSN 2590-1230. [CrossRef]

- D. Saha, I. M. Nawi, M.A. Zakariya, “Super low profile 5G mmWave highly isolated MIMO antenna with 360∘ pattern diversity for smart city IoT and vehicular communication,” Results in Engineering, Volume 24, 2024, 103209, ISSN 2590-1230. [CrossRef]

- J. R. James, P. S. Hall, and C. Wood, Microstrip Antenna Theory and Design, Peter Peregrinus, London, UK, 1981.

- R. E. Munson, “Microstrip Antennas,” Chapter 7 in Antenna Engineering Handbook (R. C. Johnson and H. Jasik, eds.), McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1984.

- W. F. Richards, “Microstrip Antennas,” Chapter 10 in Antenna Handbook: Theory, Applications and Design (Y. T. Lo and S. W. Lee, eds.), Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York, 1988.

- J. R. James and P. S. Hall, Handbook of Microstrip Antennas, Vols. 1 and 2, Peter Peregrinus, London, UK, 1989.

- P. Bhartia, K. V. S. Rao, and R. S. Tomar, Millimeter-Wave Microstrip and Printed Circuit Antennas, Artech House, Boston, MA, 1991.

- J. R. James, “What’s New In Antennas,” IEEE Antennas Propagat. Mag., Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 6–18, February 1990. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Pozar, “Microstrip Antennas,” Proc. IEEE, Vol. 80, No. 1, pp. 79–81, January 1992. [CrossRef]

- Md․ Sohel Rana, Sheikh Md․ Rabiul Islam, Sanjukta Sarker, “Machine learning based on patch antenna design and optimization for 5 G applications at 28GHz, “Results in Engineering, Volume24, 2024, 103366, ISSN 2590-1230. [CrossRef]

- F. Zavosh and J. T. Aberle, “Infinite Phased Arrays of Cavity-Backed Patches,” Vol. AP-42, No. 3, pp. 390–398, March 1994. [CrossRef]

- E. Jebabli, M. Hayouni, and F. Choubani, “Impedance Matching Enhancement of A Microstrip Antenna Array Designed for Ka-band 5G Applications,” in 2021 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Jun. 2021, pp. 1254–1258. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Seddiki, M. Nedil, S. Tebache and S. E. Hadji, “Compact Multiband Handset Antenna Design for Covering 5G Frequency Bands,” in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 20822-20829, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ishteyaq. K. Muzaffar. Multiple input multiple output (MIMO) and fifth generation (5G): An indispensable technology for sub-6 GHz and millimeter wave future generation mobile terminal applications. Int. J. Microw. Wirel. Technol. 2022, 14, 932–948. [CrossRef]

- S. Ali, M. Wajid, A. Kumar, M.S Alam,. Design Challenges and Possible Solutions for 5G SIW MIMO and Phased Array Antennas: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 88567–88594. [CrossRef]

- Lau, A, Z. Ying,” Antenna design challenges and solutions for compact MIMO terminals. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Workshop on Antenna Technology (iWAT), Hong Kong, China, 7–9 March; pp. 70–73, 2011.

- Kumar, A. Ansari, B. Kanaujia,, J. Kishor, L. Matekovits,” A Review on Different Techniques of Mutual Coupling Reduction Between Elements of Any MIMO Antenna. Part 1: DGSs and Parasitic Structures”. Radio Sci. 56, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Kumar, et al. “A Compact Quad-Port UWB MIMO Antenna with Improved Isolation Using a Novel Mesh-Like Decoupling Structure and Unique DGS”. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs, 70, 949–953, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, et. al. “Highly selective multiple-notched UWB-MIMO antenna with low correlation using an innovative parasitic decoupling structure”. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 43, 101440, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. N. Tiwari, P. Singh, B. K. Kanaujia, K. Srivastava, “Neutralization technique based two and four port high isolation MIMO antennas for UWB communication”. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun. 110, 152828,2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Zou, et. al. Widebandcouplingsuppressionwiththeneutralization line-incorporated decoupling network in MIMO arrays. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun, 167, 154688,2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Wu, M. Wang, J. Chen, “Decoupling of MIMO antenna array based on half-mode substrate integrated waveguide with neutralization lines’. AEU Int. J. Electron. Commun., 157, 154416, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Mahbub, R. Islam, S. A. Kadir Al-Nahiun, S. B. Akash, R. R. Hasan, and Md. A. Rahman, “A Single-Band 28.5GHz Rectangular Microstrip Patch Antenna for 5G Communications Technology,” in 2021 IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Jan. 2021, pp. 1151–1156. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Khattak, A. Sohail, U. Khan, Z. Barki, and and G. Witjaksono, “Elliptical Slot Circular Patch Antenna Array with Dual Band Behaviour for Future 5G Mobile Communication Networks,” Progress In Electromagnetics Research C, vol. 89, pp. 133–147, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Kaeib, N. M. Shebani, and A. R. Zarek, “Design and Analysis of a Slotted Microstrip Antenna for 5G Communication Networks at 28 GHz,” in 2019 19th International Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (STA), Mar. 2019, pp. 648–653. [CrossRef]

- W. Ahmad and W. T. Khan, “Small form factor dual band (28/38 GHz) PIFA antenna for 5G applications,” in 2017 IEEE MTT-S International Conference on Microwaves for Intelligent Mobility (ICMIM), Mar. 2017, pp. 21–24. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J.-Y. Deng, M.-J. Li, D. Sun, and L.-X. Guo, “A MIMO Dielectric Resonator Antenna With Improved Isolation for 5G mmWave Applications,” IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 747–751, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Jebabli, M. Hayouni, and F. Choubani, “Impedance Matching Enhancement of A Microstrip Antenna Array Designed for Ka-band 5G Applications,” in 2021 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC), Jun. 2021, pp. 1254–1258. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Park, J. B. Ko, H. K. Kwon, B. S. Kang, B. Park, and D. Kim, “A Tilted Combined Beam Antenna for 5G Communications Using a 28- GHz Band,” IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, vol. 15, pp. 1685–1688, 2016. [CrossRef]

| Dimension | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (mm) | 21 | 18 | 9.63 | 12.4 | 6.1 | 3 | 1.29 | 10 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 1 | 1.73 | 0.7 | 0.508 | 0.035 |

| Design | Gain () |

Center frequency () |

() |

BW () |

Directivity () |

Efficiency | Other 5g bands () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | 9.82 | 28.1 | -42 | 1.29 | - | 87.5% | - |

| [24] | 8.31 | 28 | -54 | 5.13 | 8.35 | 84.8% | 38.5 |

| [25] | 7.6 | 28 | -40 | 1.3 | 7.68 | 85.6% | 45 |

| [26] | 7.41 | 28 | -35 | 1.5 | - | - | - |

| [27] | 7.02 | 28.1 | -19.3 | 0.9 | 7.69 | 85.5% | 24.4,38 |

| [28] | 6.83 | 28.06 | -18.25 | 1.1 | - | - | - |

| [29] | 6.73 | 28 | -40 | 2.48 | 6.99 | 86.73% | - |

| Proposed | 10.11 | 28 | -33.54 | 1.3 | 10.5 | 91.5% | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).