Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

02 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Drosophila and Feeding Assay

2.2. cDNA Synthesis and Quantitative PCR Analysis

2.3. EC-Specific Knockdown of Selected Genes Using RNA-Interference

2.4. Drosophila Gut Immunostaining and Imaging

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

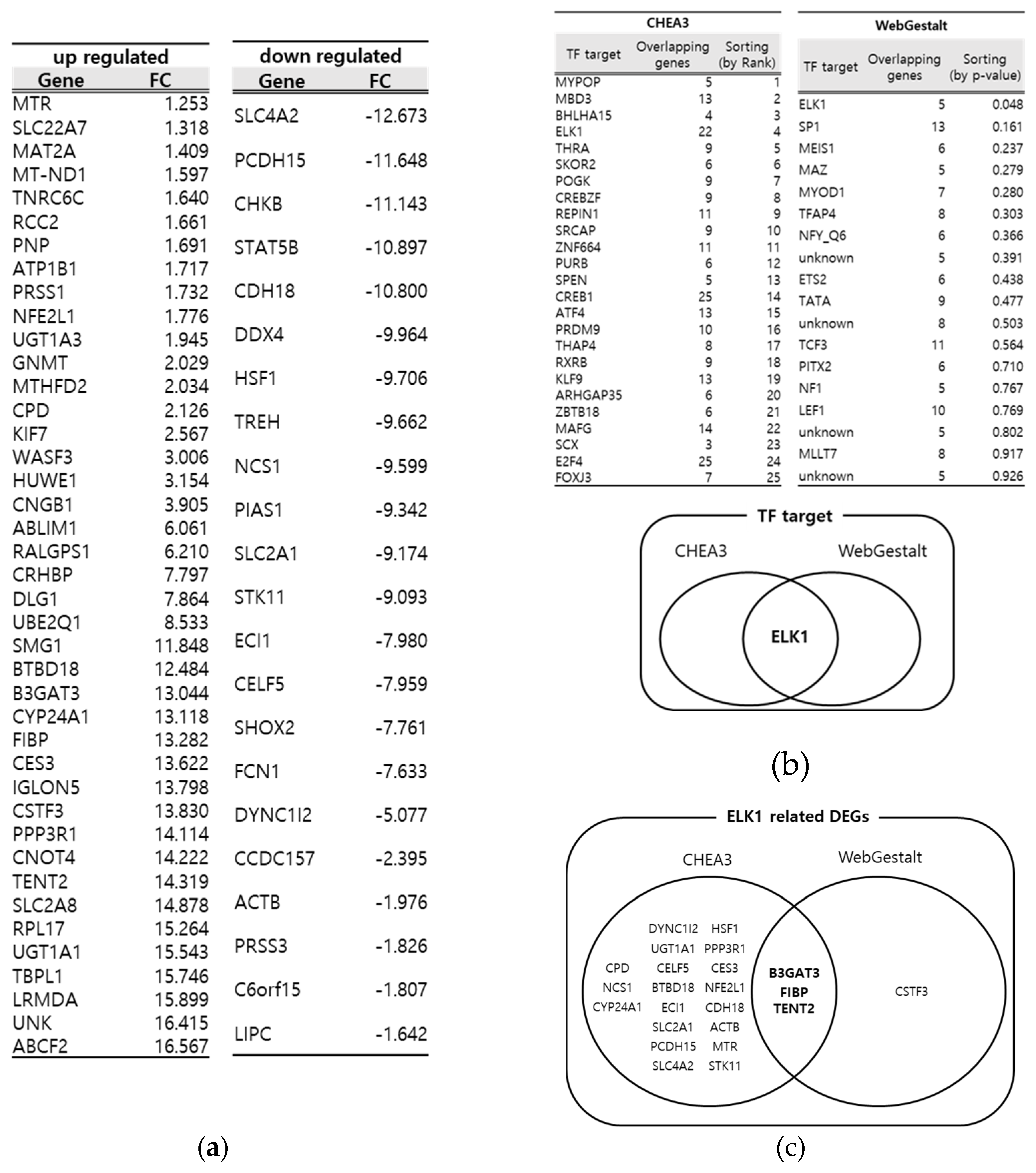

3.1. Identification of key DEGs from DSS- induced Drosophila IBD model through multiple bioinformatics tools

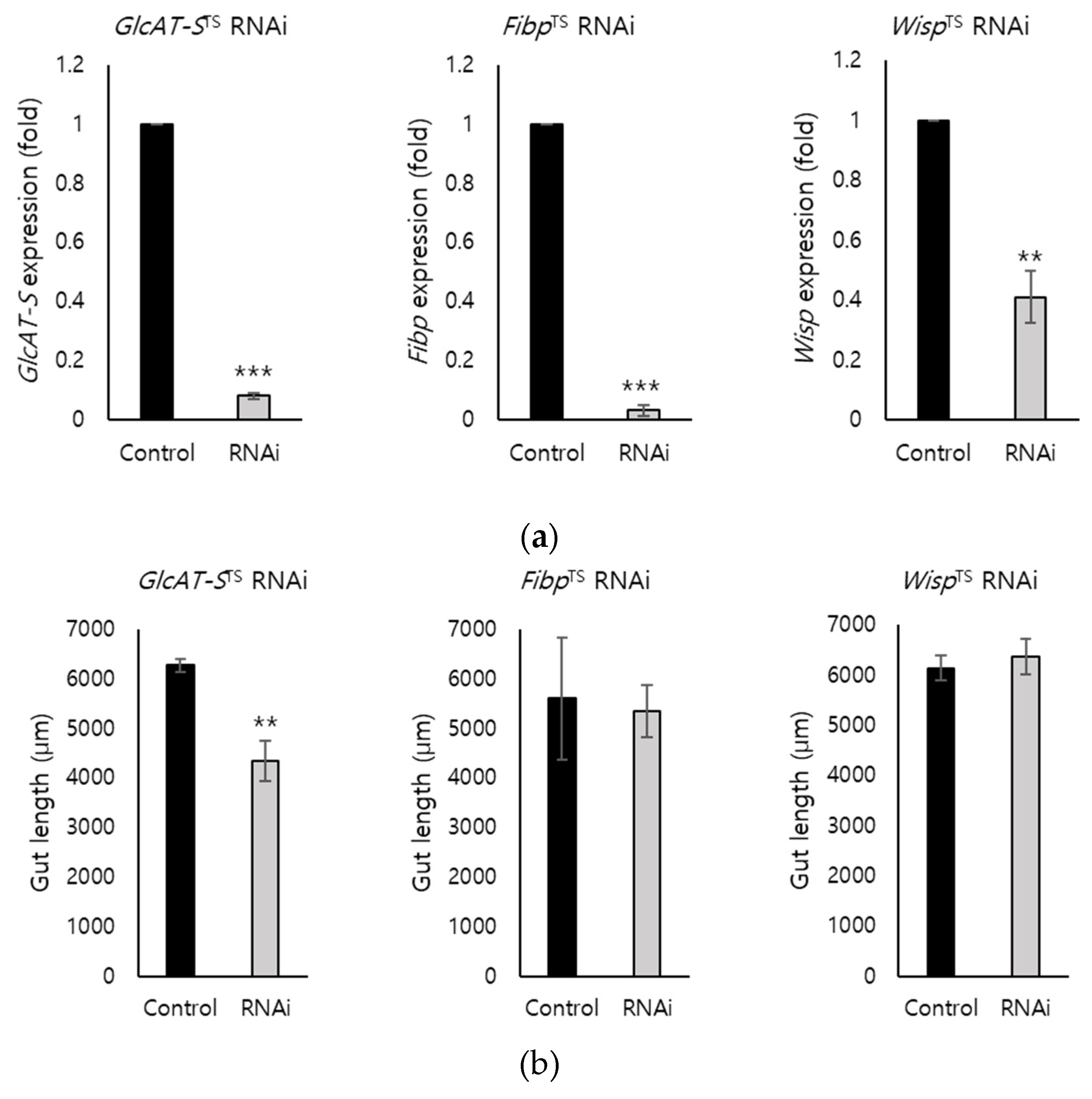

3.2. EC-Specific Knockdown of Screened DEGs

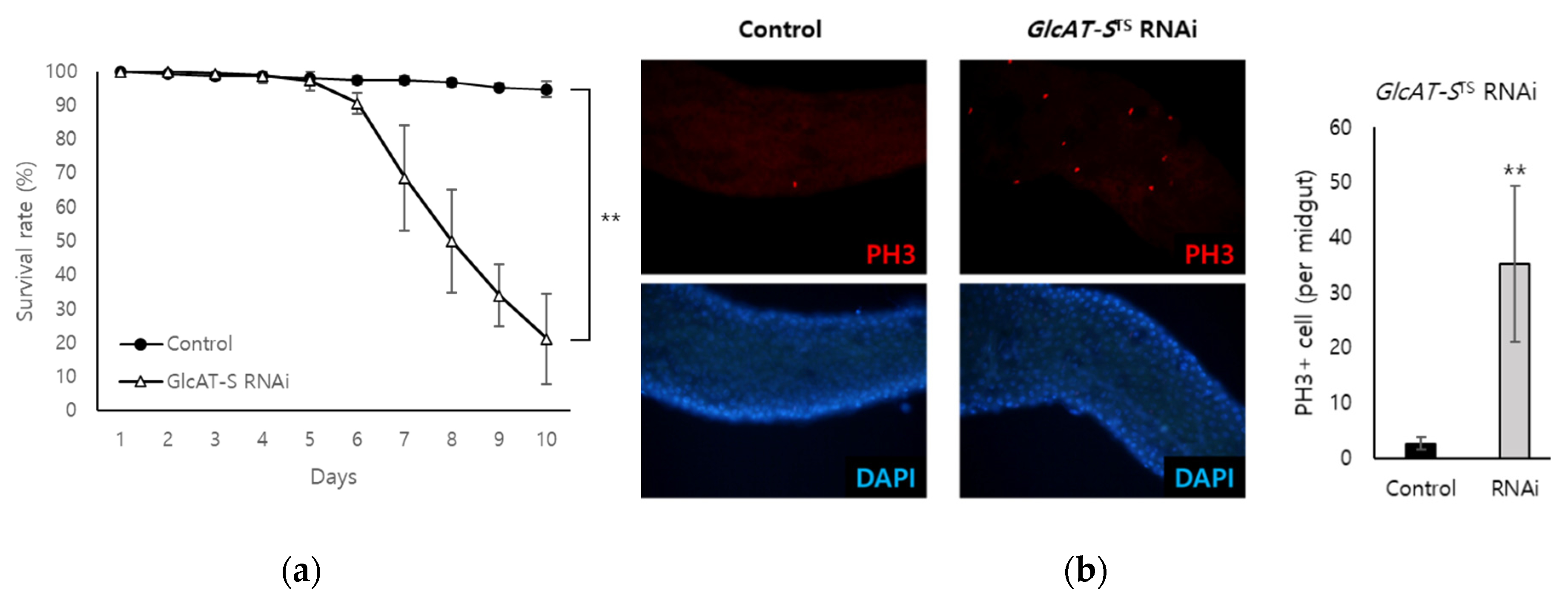

3.3. Confirmation of the Relationship Between GlcAT-S and Gut Tissue damage Through EC-Specific Knockdown

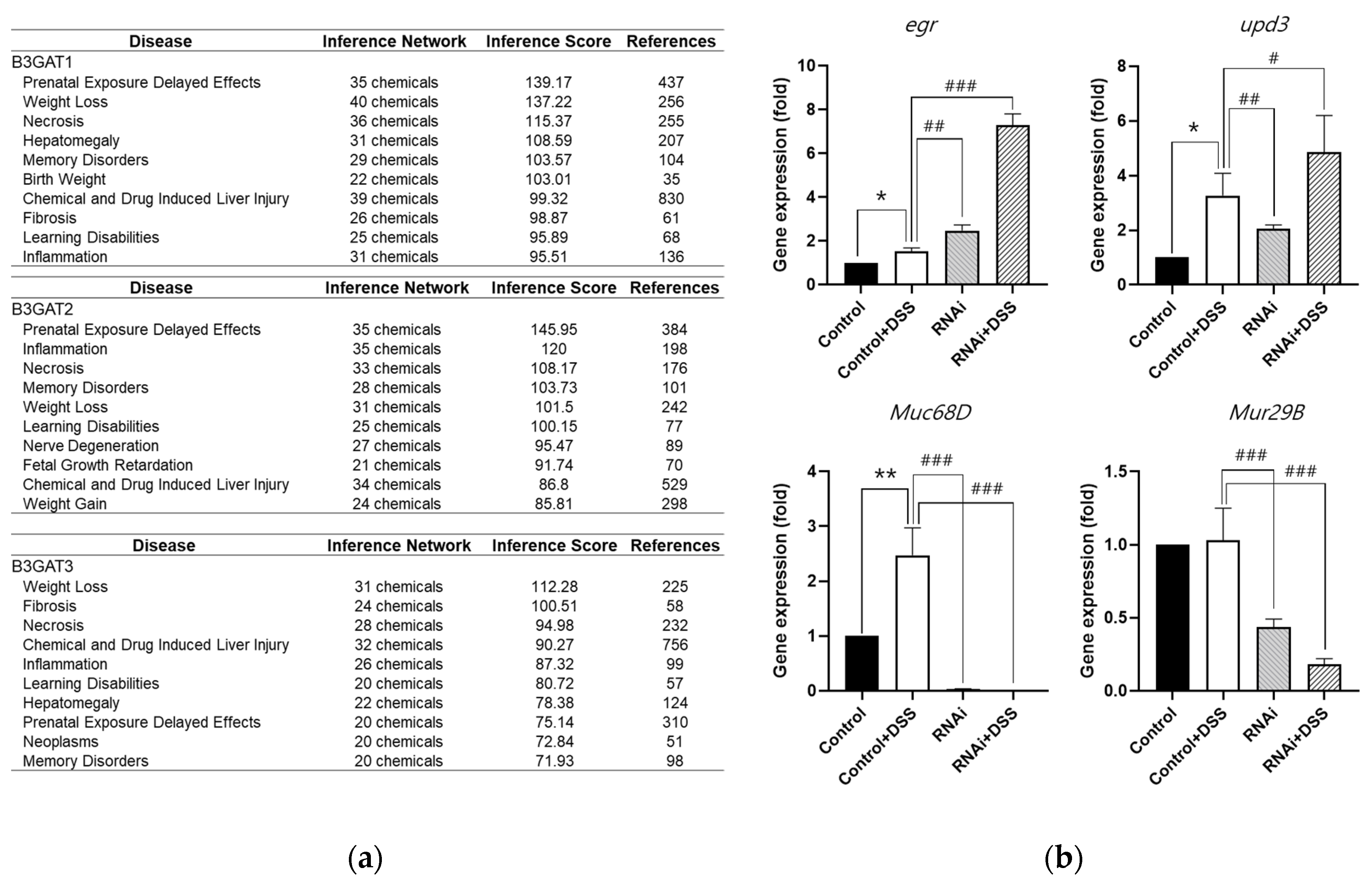

3.4. Analysis of the Relationship Among GlcAT-S, Mucus Loss, and Inflammation in the Drosophila Gut-Damage Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neurath, Neurath, M.F. Cytokines in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2014, 14, 329–342. [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R. Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Function in Health and Disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009, 9, 799–809. [CrossRef]

- Grondin, J.A.; Kwon, Y.H.; Far, P.M.; Haq, S.; Khan, W.I. Mucins in Intestinal Mucosal Defense and Inflammation: Learning From Clinical and Experimental Studies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2054. [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013, 9, 367–374.

- Pandey, U.B.; Nichols, C.D. Human Disease Models in Drosophila melanogaster and the Role of the Fly in Therapeutic Drug Discovery. Pharmacological Reviews 2011, 63, 411–436. [CrossRef]

- Apidianakis, Y.; Rahme, L.G. Drosophila melanogaster as a Model for Human Intestinal Infection and Pathology. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2011, 4, 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Galeone, A.; Han, S.Y.; Story, B.A.; Consonni, G.; Mueller, W.F.; Steinmetz, L.M.; Vaccari, T.; Jafar-Nejad, H. Gut Barrier Defects, Intestinal Immune Hyperactivation and Enhanced Lipid Catabolism Drive Lethality in NGLY1-Deficient Drosophila. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5667. [CrossRef]

- Roditi, I.; Lehane, M.J. Interactions between Trypanosomes and Tsetse Flies. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2008, 11, 345–351. [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Aitken, J.D.; Malleshappa, M.; Vijay-Kumar, M. Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS)-Induced Colitis in Mice. CP in Immunology 2014, 104. [CrossRef]

- Katsandegwaza, B.; Horsnell, W.; Smith, K. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review of Pre-Clinical Murine Models of Human Disease. IJMS 2022, 23, 9344. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Liu, F.; Huang, Y.; Liang, Q.; He, X.; Li, L.; Xie, Y. Drosophila: An Important Model for Exploring the Pathways of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) in the Intestinal Tract. IJMS 2024, 25, 12742. [CrossRef]

- Capo, F.; Wilson, A.; Di Cara, F. The Intestine of Drosophila Melanogaster: An Emerging Versatile Model System to Study Intestinal Epithelial Homeostasis and Host-Microbial Interactions in Humans. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 336. [CrossRef]

- Buchon, N.; Broderick, N.A.; Lemaitre, B. Gut Homeostasis in a Microbial World: Insights from Drosophila Melanogaster. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013, 11, 615–626. [CrossRef]

- Dietzl, G.; Chen, D.; Schnorrer, F.; Su, K.-C.; Barinova, Y.; Fellner, M.; Gasser, B.; Kinsey, K.; Oppel, S.; Scheiblauer, S.; et al. A Genome-Wide Transgenic RNAi Library for Conditional Gene Inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 2007, 448, 151–156. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet 2009, 10, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Tarca, A.L.; Carey, V.J.; Chen, X.; Romero, R.; Drăghici, S. Machine Learning and Its Applications to Biology. PLoS Comput Biol 2007, 3, e116. [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, C.; Kia, D.A.; Vandrovcova, J.; Hardy, J.; Wood, N.W.; Lewis, P.A.; Ferrari, R. Genome, Transcriptome and Proteome: The Rise of Omics Data and Their Integration in Biomedical Sciences. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 286–302. [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, W.H.; Medd, N.C.; Beard, P.M.; Obbard, D.J. Isolation of a Natural DNA Virus of Drosophila Melanogaster, and Characterisation of Host Resistance and Immune Responses. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1007050. [CrossRef]

- Ewen-Campen, B.; Luan, H.; Xu, J.; Singh, R.; Joshi, N.; Thakkar, T.; Berger, B.; White, B.H.; Perrimon, N. Split-Intein Gal4 Provides Intersectional Genetic Labeling That Is Repressible by Gal80. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2304730120. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Hwang, D.; Goo, T.-W.; Yun, E.-Y. Prediction of Intestinal Stem Cell Regulatory Genes from Drosophila Gut Damage Model Created Using Multiple Inducers: Differential Gene Expression-Based Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 2023, 138, 104539. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Singh, R.; Baym, M.; Liao, C.-S.; Berger, B. IsoBase: A Database of Functionally Related Proteins across PPI Networks. Nucleic Acids Research 2011, 39, D295–D300. [CrossRef]

- Keenan, A.B.; Torre, D.; Lachmann, A.; Leong, A.K.; Wojciechowicz, M.L.; Utti, V.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Kropiwnicki, E.; Wang, Z.; Ma’ayan, A. ChEA3: Transcription Factor Enrichment Analysis by Orthogonal Omics Integration. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, W212–W224. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jaehnig, E.J.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2019: Gene Set Analysis Toolkit with Revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, W199–W205. [CrossRef]

- Osumi, R.; Sugihara, K.; Yoshimoto, M.; Tokumura, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Hinoi, E. Role of Proteoglycan Synthesis Genes in Osteosarcoma Stem Cells. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1325794. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-F.; Niu, W.-B.; Hu, R.; Wang, L.-J.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Ni, S.-H.; Wang, M.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.-S.; Feng, W.-J.; et al. FIBP Knockdown Attenuates Growth and Enhances Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer via Regulating GSK3β-Related Pathways. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 77. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Bofill-De Ros, X.; Stanton, R.; Shao, T.-J.; Villanueva, P.; Gu, S. TENT2, TUT4, and TUT7 Selectively Regulate miRNA Sequence and Abundance. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5260. [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, W. Regulation of Intestinal Epithelial Cells Properties and Functions by Amino Acids. BioMed Research International 2018, 2018, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, L.T.; Austin, S.; Cole, T.J. Small Intestinal Length: A Factor Essential for Gut Adaptation. Gut 1991, 32, 1321–1323. [CrossRef]

- Viragova, S.; Li, D.; Klein, O.D. Activation of Fetal-like Molecular Programs during Regeneration in the Intestine and Beyond. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 949–960. [CrossRef]

- Amcheslavsky, A.; Lindblad, J.L.; Bergmann, A. Transiently “Undead” Enterocytes Mediate Homeostatic Tissue Turnover in the Adult Drosophila Midgut. Cell Reports 2020, 33, 108408. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory Responses and Inflammation-Associated Diseases in Organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [CrossRef]

- Oz, H.S.; Yeh, S.-L.; Neuman, M.G. Gastrointestinal Inflammation and Repair: Role of Microbiome, Infection, and Nutrition. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2016, 2016, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Cornick, S.; Tawiah, A.; Chadee, K. Roles and Regulation of the Mucus Barrier in the Gut. Tissue Barriers 2015, 3, e982426. [CrossRef]

- Saez, A.; Herrero-Fernandez, B.; Gomez-Bris, R.; Sánchez-Martinez, H.; Gonzalez-Granado, J.M. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Innate Immune System. IJMS 2023, 24, 1526. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shen, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, W.; Zuo, L.; Zhao, J.; Gu, L.; Gong, J.; Li, J. Therapeutic Potential to Modify the Mucus Barrier in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 44. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.S.; Seyed Hameed, A.S.; Meng, X.; Liu, W. Utilization of Glycosaminoglycans by the Human Gut Microbiota: Participating Bacteria and Their Enzymatic Machineries. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2068367. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.-H.; Yang, J.-Y. Mechanobiological Approach for Intestinal Mucosal Immunology. Biology 2025, 14, 110. [CrossRef]

- Murch, S.H.; MacDonald, T.T.; Walker-Smith, J.A.; Lionetti, P.; Levin, M.; Klein, N.J. Disruption of Sulphated Glycosaminoglycans in Intestinal Inflammation. The Lancet 1993, 341, 711–714. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lane, E.A.; Saftien, A.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wirtz-Peitz, F.; Perrimon, N. Drosophila as a Model for Studying Cystic Fibrosis Pathophysiology of the Gastrointestinal System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 10357–10367. [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, H.; Uyama, T.; Sugahara, K. Molecular Cloning and Expression of a Human Chondroitin Synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 38721–38726. [CrossRef]

- Pompili, S.; Latella, G.; Gaudio, E.; Sferra, R.; Vetuschi, A. The Charming World of the Extracellular Matrix: A Dynamic and Protective Network of the Intestinal Wall. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 610189. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.E.V.; Hansson, G.C. Immunological Aspects of Intestinal Mucus and Mucins. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 639–649. [CrossRef]

- Corfield, A.P. Mucins: A Biologically Relevant Glycan Barrier in Mucosal Protection. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2015, 1850, 236–252. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Silva, J.; Wang, G.; Yu, R.K. Sulfoglucuronosyl Paragloboside Is a Ligand for T Cell Adhesion: Regulation of Sulfoglucuronosyl Paragloboside Expression via Nuclear Factor κB Signaling. J of Neuroscience Research 2009, 87, 3591–3599. [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Wang, B.; Yue, T.; Yun, E.-Y.; Ip, Y.T.; Jiang, J. Hippo Signaling Regulates Drosophila Intestine Stem Cell Proliferation through Multiple Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 21064–21069. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).