1. Introduction

Aging is associated with the onset of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, representing a natural physiological decline [

1]. Among various theories for aging, an increased production in free radicals (such as reactive oxygen species, ROS) is the most widely accepted hypothesis for explaining the aging process at the cellular level. The excessive accumulation of intracellular free radicals could lead to oxidative damage, which has a significant impact on lifespan [

2]. Therefore, enhancements in the antioxidant system and reductions in ROS could prolong the lifespan [

3].

In recent years, researchers have focused on the relationship between immunity and aging, giving rise to the immunological theory of aging. As a result of malfunctions in innate and adaptive immune responses, the body’s capacity to resist invading microorganisms and toxic substances diminishes with age. During aging, the efficacy of adaptive immune response diminishes while innate immunity often becomes more hyperactive, leading to an increased susceptibility to inflammatory responses [4-7]. The above changes could inflict harms on the tissues, leading to accelerated aging and the onset of age-related diseases [

8,

9].

Given the intense interest to maintain health and prolong lifespan, increasing researches ranging from exercise regulation, dietary control to pharmacological properties of health products have been pursued to understand aging processes [10-12]. Many plant-derived extracts are important sources for the preparation of health drugs. It’s reported that plant extracts, such as Angelica keiskei extracts, gastrodin, Agrocybe aegerita polysaccharides and ginsenosides, can prolong the lifespan of fruit flies [13-16]. Due to its short lifespan, strong reproductive ability, and clear genetic background, Drosophila melanogaster is an excellent model organism not only for studying developmental biology, but also for studying aging [17-20].

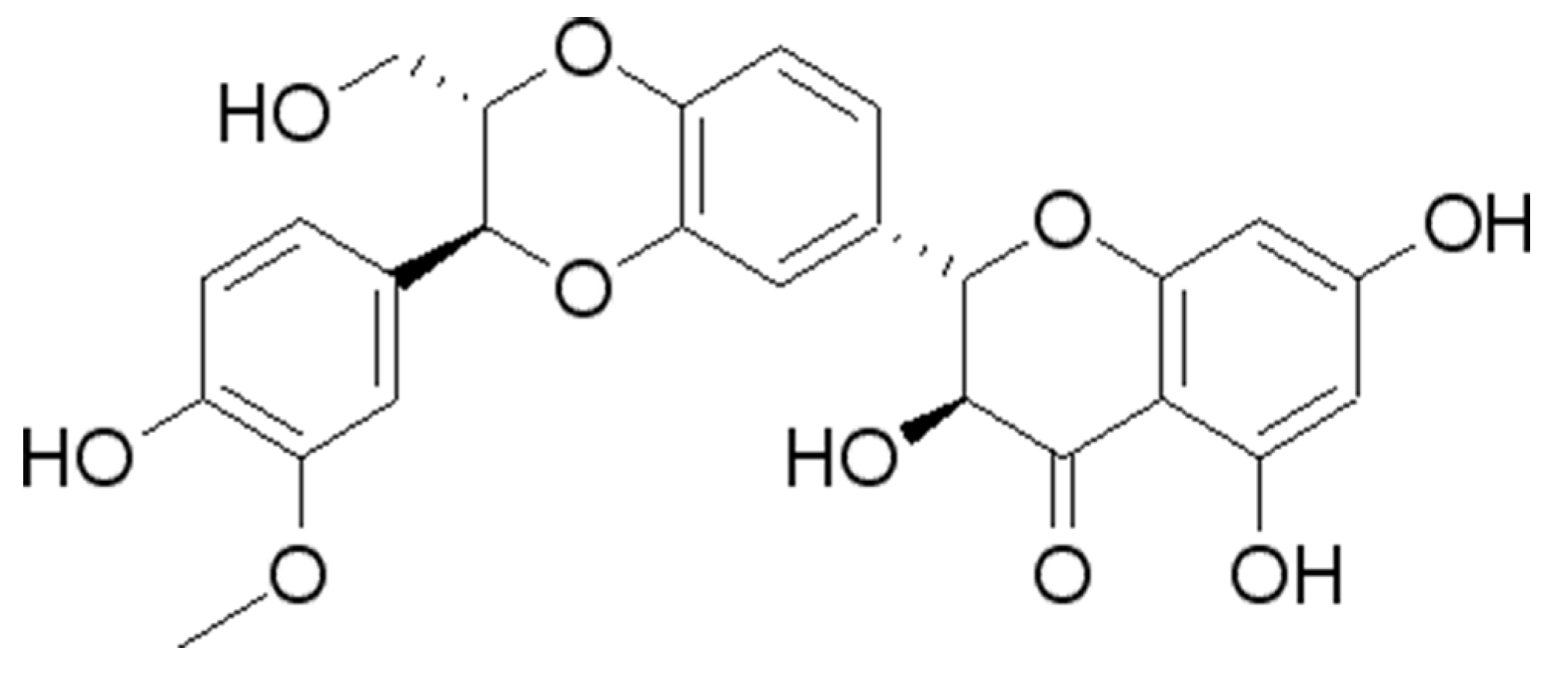

Silibinin (SIL) (

Figure 1), a flavonoid substance, is the primary component of silymarin extract from the seeds of

Silybum marianum (also called as milk thistle). SIL exhibits a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, such as anti-tumor, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and protecting liver and cardiovascular functions [21-27]. Due to its excellent antioxidant activities, SIL functions as a scavenger of free radicals, and has been widely used in the treatment of multiple diseases such as hepatitis, sepsis and cardiovascular disease [28-31]. To date, the anti-aging effects and the associated mechanisms of SIL in

Drosophila remain unclear. In this study, we examined the effect of SIL in delaying aging in fruit flies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

SIL (purity of 98%) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.; SOD assay kit and MDA assay kit were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; CAT assay kit was purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute.

2.2. Drosophila Strain and Culture

Male fruit flies were used for all experiments in this study. All fly stocks were raised at 25℃ on a standard fly medium, except those with special requirements. The w1118 strain was used as the wild-type strain and obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC). SIL was added to the standard medium at final concentrations of 0.6 mg/ml, 1.2 mg/ml, and 2.4 mg/ml. The flies were transferred to fresh medium every 3 days.

2.3. Lifespan Assay

Male flies were collected and divided into 4 equal groups (150 flies for each group) on the 3rd day after eclosion, and then placed in the standard medium and the medium supplemented with 0.6 mg/ml, 1.2 mg/ml, and 2.4 mg/ml SIL, respectively. Flies were transferred to a new tube containing fresh media every 3 days, and the number of flies that died each day were recorded until all flies died, with which the lifespan curve and average life of flies were derived.

2.4. Food Intake Detection

Food intake detection was conducted based on the Han's method [

32]. That is, after 7 days of feeding in the standard medium and SIL-added medium, a 2-hour starvation period was implemented. Subsequently, 20 male flies per experimental group were transferred to the standard medium containing 2.5% (w/v) of bright blue (dye, Macklin). After a 1-hour feeding period, flies were homogenized and centrifuged in 1ml of phosphate buffer solution. The absorbance of the supernatant at 595nm was measured using a spectrophotometer.

2.5. Body weight Detection

Fruit flies were raised in different groups of culture medium for 20 days and 40 days, respectively. Ten healthy flies were selected and weighed after being anesthetized with CO2. Each group was measured three times and the average value was taken.

2.6. Climbing Assay

Athletic ability was evaluated using a negative geotropism test. After cultivating in the standard medium supplemented with SIL for 20 and 40 days respectively, the flies were incubated in empty culture tubes at 25℃ for 30 minutes, afterwards, fruit flies were gently patted to the bottom of the tube. Percentages of flies climbing 5 cm or more in 15 seconds were recorded, which was used as the climbing ability of flies. The climbing assay was repeated 3 times for each experimental group.

2.7. Smurf Assay

The "Smurf" test usually refers to the use of a non-absorbent dye (bright blue, Macklin) to assess the barrier effect of the fruit fly intestine [

33,

34]. Fruit flies cultured in the standard medium were used as control. Male flies were raised in the medium containing SIL for 20 and 40 days, respectively. Subsequently, all flies were starved for 1 hour, and then transferred to dyed food containing blue dye (2.5% w/v) and raised for 2.5 hours, eventually the number of "Smurfs" was calculated. When blue dye staining is observed throughout a fly's entire body, it is identified as a "Smurf" phenomenon.

2.8. Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) Challenge Assay

H

2O

2 is used to generate hydroxyl radicals (·OH). After H

2O

2 induction, the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in flies increased, resulting in accelerated aging. The method was adapted from Liu et al [

35]. Newly hatched male flies were fed the standard medium and medium supplemented with SIL respectively. On day 20, flies were starved for 2 hours in an empty vial containing filter paper soaked in distilled water, then transferred to separate vials containing filter paper soaked with 6% sucrose-30% H

2O

2 solution. The death events were recorded every 2 hours until all flies died.

2.9. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and MDA Content

Newly hatched male flies were raised with the standard medium and medium supplemented with 0.6 mg/ml, 1.2 mg/ml and 2.4 mg/ml SIL for 40 days respectively. Subsequently all flies were starved for 1 hour, then transferred to a centrifuge tube and quick-frozen with liquid nitrogen. Then frozen samples were homogenized in phosphate buffer solution, centrifuged at 1500g at 4℃for 10 minutes. The supernatant was collected and stored at -80℃. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, catalase (CAT) activity, and malondialdehyde (MDA) content of samples in each group were measured.

2.10. RNA-Seq

RNA-seq was conducted by Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co. Ltd. Male flies were cultured in standard foods (control) or medium supplemented with 1.2 mg/ml SIL for 30 days. Total RNAs were extracted from fruit fly samples. The purity and concentration of RNA were measured using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. The sequencing library was constructed and sequenced on an Illumina platform. The raw reads were filtered and the Q20 and Q30 of Clean reads were calculated simultaneously. DESeq2 was used to perform differential expression analysis. The statistical enrichment of the Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathways of differentially expressed genes were analyzed using the clusterProfile software.

2.11. Real-Time PCR

Male flies were reared in standard (control) or SIL-supplemented food for 40 days, then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNAs were extracted, and the cDNA was prepared using PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TAKARA). CT values were calculated to analyze the relative expression of genes. The following primers were used for amplifying differential expression genes (rp49 gene as reference) (

Table 1).

2.12. Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism6 (Version No. 6, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). In addition to survival, statistical significance was established using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-test. The survival rates among the groups were compared and the logrank test was used for significance test. For all analyses, significant levels of p values were expressed as *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, and ****<0.0001.

3. Results

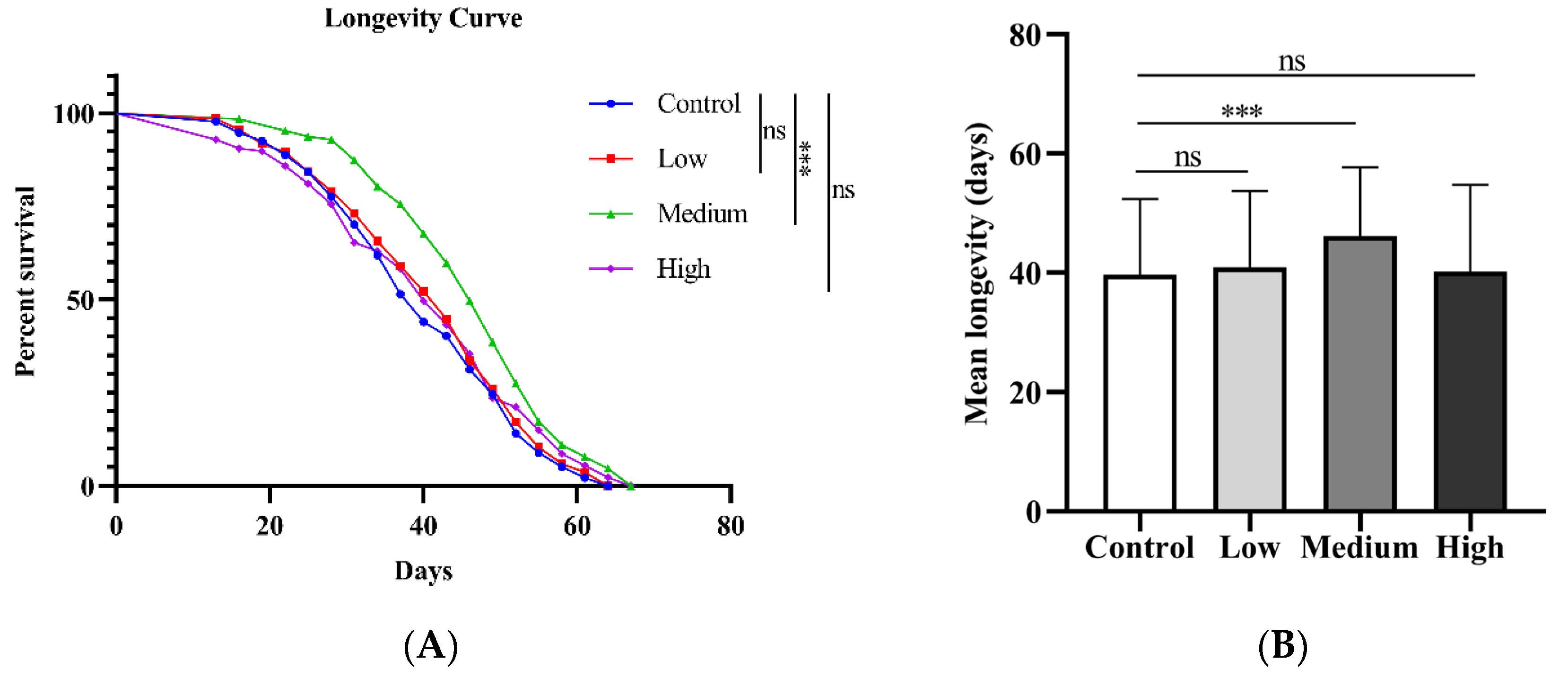

3.1. SIL Supplementation Extends the Lifespan in Drosophila

To explore whether SIL prolongs the lifespan of fruit flies, we performed an assay using male

w1118 as experimental material, by adding SIL to the basic culture medium. In this experiment, three concentrations of SIL (0.6 mg/ml, 1.2 mg/ml, and 2.4 mg/ml) were used to examine the lifespan of fruit flies. We found that, compared with the control group (no dietary addition of SIL), the average lifespan of flies fed with 1.2 mg/ml SIL was extended by 16.32% (

p < 0.001) (

Figure 2A-B). However, both lower and higher concentrations of SIL did not affect the lifespan of male flies. The results suggest that SIL supplementation extends the lifespan in

Drosophila in the concentration-dependent manner. We speculate that high concentrations of Sil may cause toxicity to fruit flies and shorten their lifespan instead.

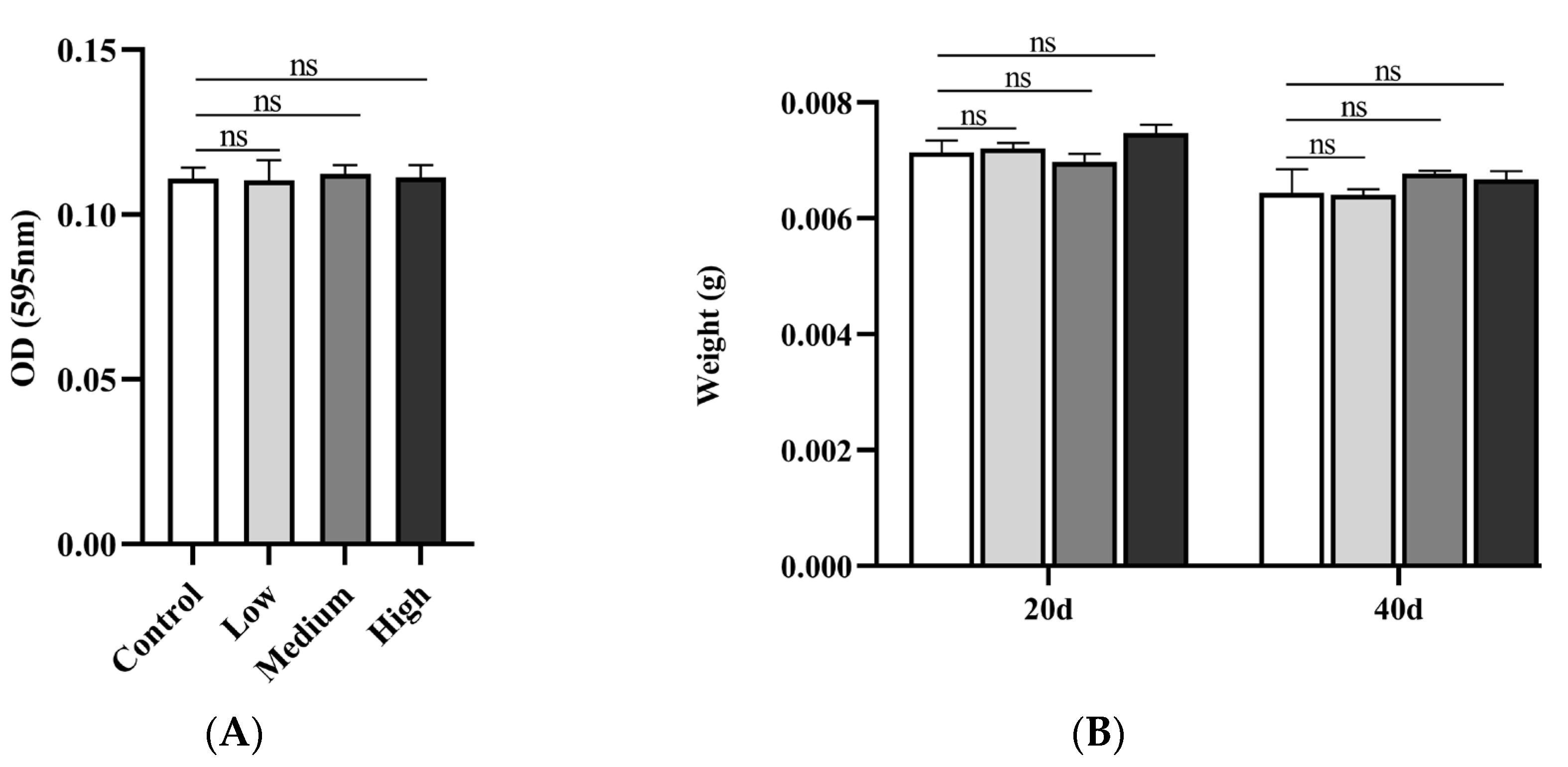

3.2. SIL Fails to Affect Food Intake and Body Weight Of Flies

Caloric restriction (CR) has been one of the most effective strategies for extending the lifespan of animals [

36,

37]. We are uncertain whether the SIL-addition will decrease the food consumption of fruit flies, thus prolonging its lifespan accordingly. Therefore, it is necessary to measure food intake of flies after SIL supplementation.

In food intake assays, it is common to reflect changes in dietary behavior by adding bright blue to the food in

Drosophila. The results showed that there was no difference between the SIL-feeding group with different concentrations (0.6mg/ml, 1.2mg/ml, and 2.4 mg/ml) compared to the control group (

Figure 3A). This result indicates that SIL does not influence food intake of fruit flies, and the lifespan extension of SIL is not achieved through CR in

Drosophila.

In animal, the body weights are frequently influenced by their dietary behavior. Therefore, we assessed the fly weight after administering SIL. The results showed that, compared with the control, there was no difference in body weight after the continuous supplementation of SIL for 20 and 40 days (

Figure 3B). Put together, we eliminated the effects of CR on the lifespan in

Drosophila.

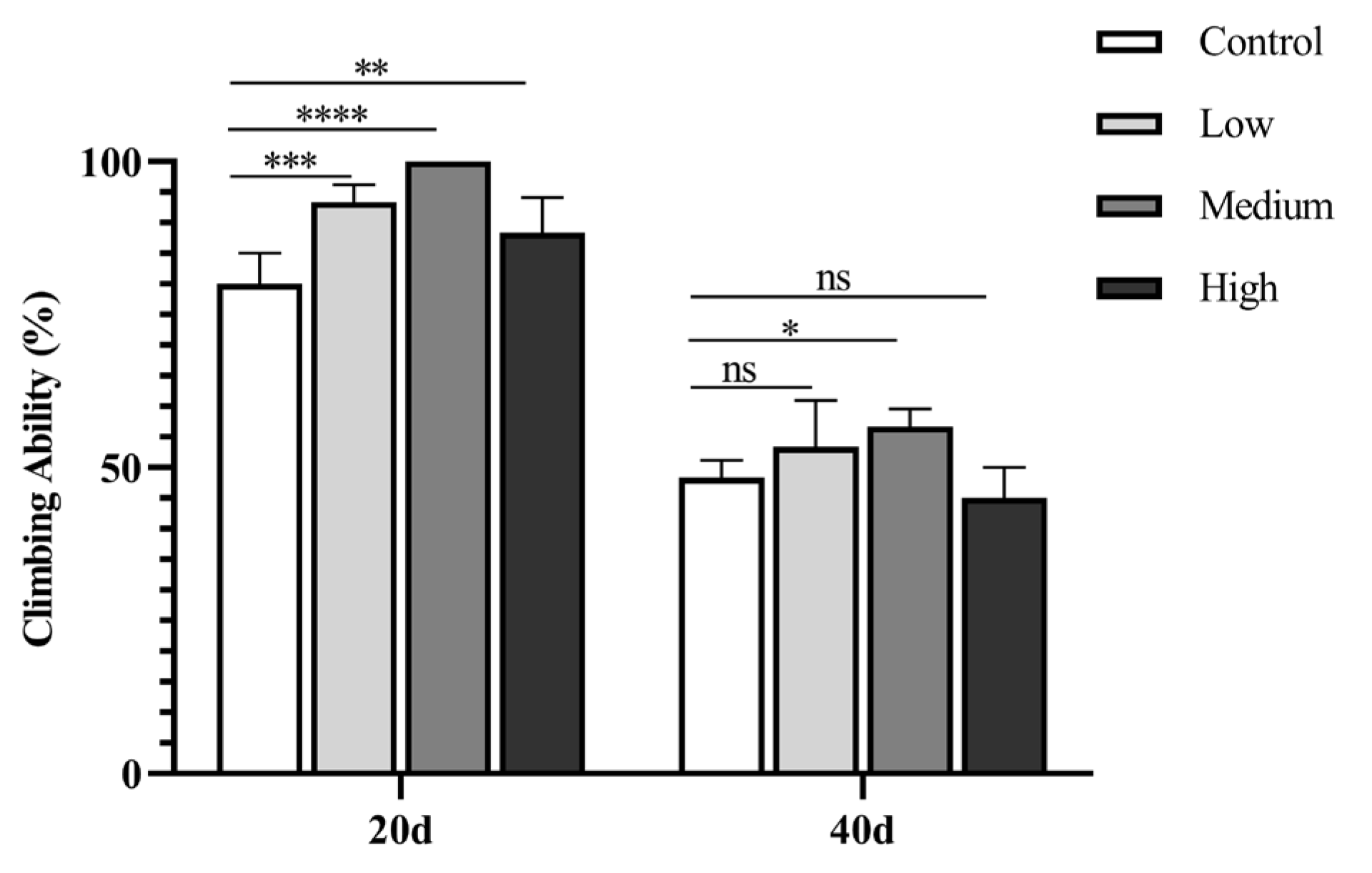

3.3. SIL Improves the Locomotor Ability

Fruit flies exhibit a habit of climbing upwards in enclosed spaces [

38], so the climbing ability is an important indicator of insect motility. The climbing ability can be quantitated by recording the number of fruit flies that climb to a set point within a specified time. As shown in

Figure 4, compared with 20-day-old flies, the climbing ability of each group collected from 40-day-old (with or without SIL added) was significantly decreased, suggesting the athletic ability is closely related with aging.

We subsequently analyzed the locomotor ability of fruit flies with continuous SIL-supplementation for 20 and 40 days, with no SIL-addition as control. The results showed that, compared to the control, the climbing ability of flies with 20-day-SIL-feeding was significantly increased, especially the middle-concentration group (1.2 mg/ml) increased the most by 25.0% (

P < 0.0001) (

Figure 4). When continuous SIL-supplementation for 40 days, the improvement of climbing ability was only observed in the middle-concentration group, with an increase of 17.26% (

P < 0.05) (

Figure 4). The results suggest that SIL enhances the athletic ability in both age- and concentration- dependent manner in

Drosophila.

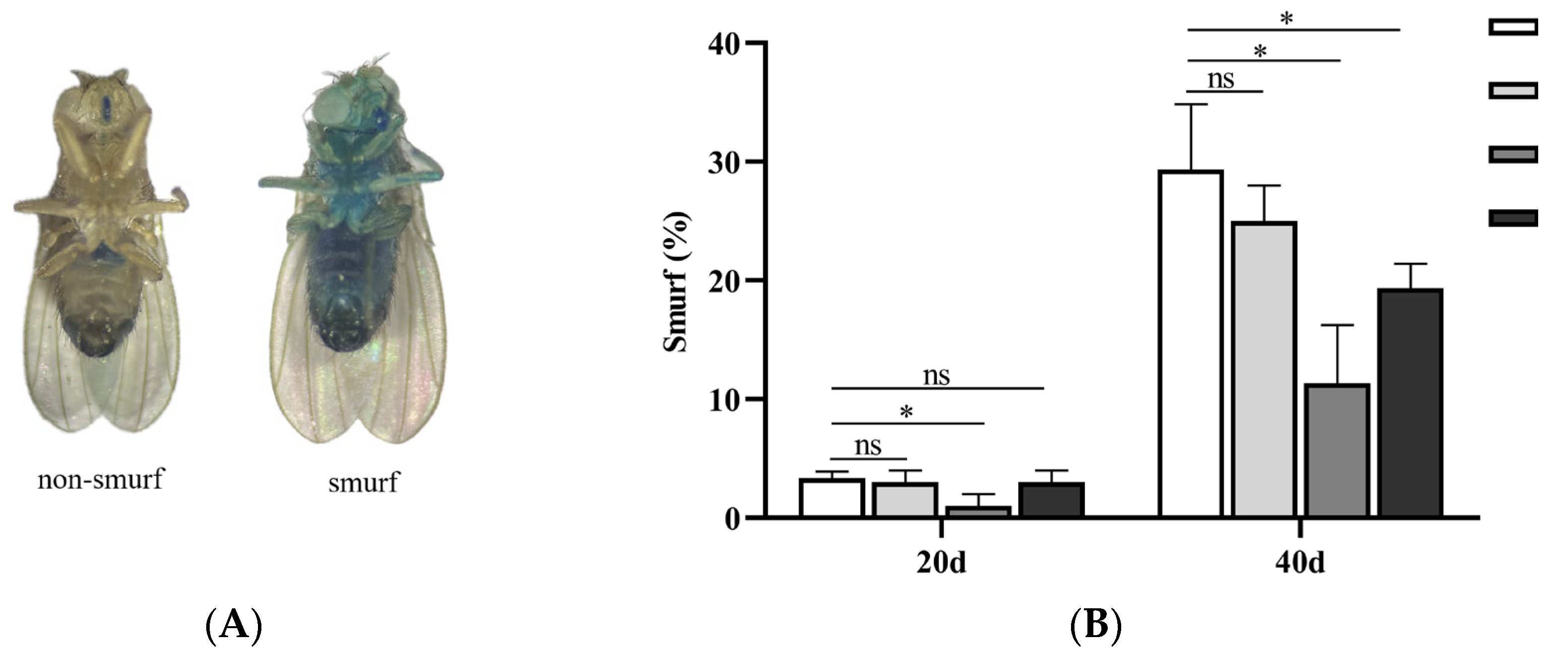

3.4. SIL Prevents the Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Aged Flies

Previous studies have shown that, relying on tissue homeostasis and cell junctions, the gut of young fruit flies maintains structural integrity and low intestinal permeability. Conversely, the intestinal barrier protection in older fruit flies is compromised, exhibiting the increased permeability [

39,

40]. As shown in

Figure 5A, in fruit flies with intact intestinal function after consuming blue dye food, the blue coloration was largely confined to the mouthpart and the digestive tract. However, when the intestinal barrier function is impaired, the blue dye becomes clearly visible throughout the entire body, leading to the nickname “Smurfs” [

40].

To explore physiological protective effects of SIL on the gut of older flies, we performed the “Smurfs” assay to assess the integrity of the physical barrier in the gut of fruit flies. We took old male fruit flies (day 40 after eclosion) as research subjects, and the results showed that compared to the control group, the percentage of Smurfs flies in both 1.2mg/ml and 2.4mg/ml SIL treatment groups decreased significantly (

Figure 5B). Moreover, the 1.2mg/ml SIL treatment group exhibited the most significant reduction, with a decrease of 61.37%. These findings fully demonstrate that SIL supplementation prevents the intestinal barrier dysfunction in old flies, thereby preserving the integrity of intestinal tracts.

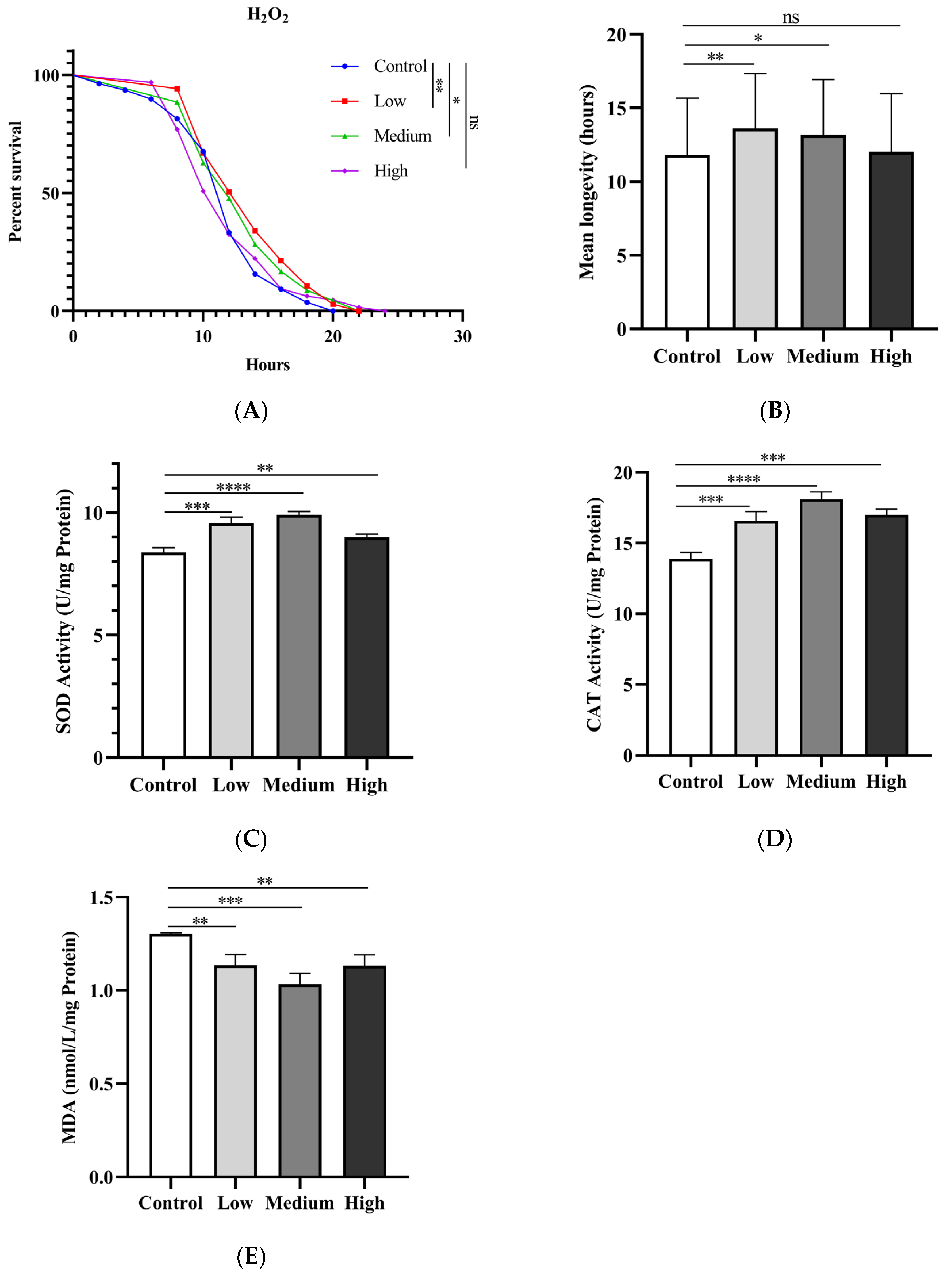

3.5. SIL Enhances the Antioxidant Capacity

Numerous plant extracts, such as polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, anthocyanins and saponins, can extend the lifespan in flies by enhancing their resistance to oxidative stress [41-44]. To determine whether SIL extends the lifespan of flies by enhancing the antioxidant capacity, male fruit flies were fed with SIL for 20 days, then transferred to filter paper containing 30% H

2O

2 solution to record the mortality. The results showed that SIL supplementation notably boosted survival rates under H

2O

2-induced oxidative stress conditions compared with the control group (

Figure 6A-B). The average survival rates of the 0.6mg/ml and 1.2mg/ml SIL treatment groups rose by 15.24% and 11.35%, respectively, contrast to the control group.

To explore whether SIL extends the lifespan by enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes in flies, we detected the activities of the SOD and CAT in male flies treated by SIL. The SOD activity was significantly increased in flies treated with three concentrations (0.6mg/ml, 1.2mg/ml, and 2.4 mg/ml) of SIL for 40 days (

Figure 6C). The activity of CAT was also markedly increased by same dose of SIL supplementation (

Figure 6D). Malondialdehyde (MDA) is the product of free radicals reaction, which directly reflects the degree of oxidative damage in organisms [

45]. As shown in

Figure 6E, the levels of MDA were significantly reduced under different concentrations of SIL treatment. The above results indicate that SIL exerts anti-aging effects by enhancing the antioxidant capacity in fruit flies.

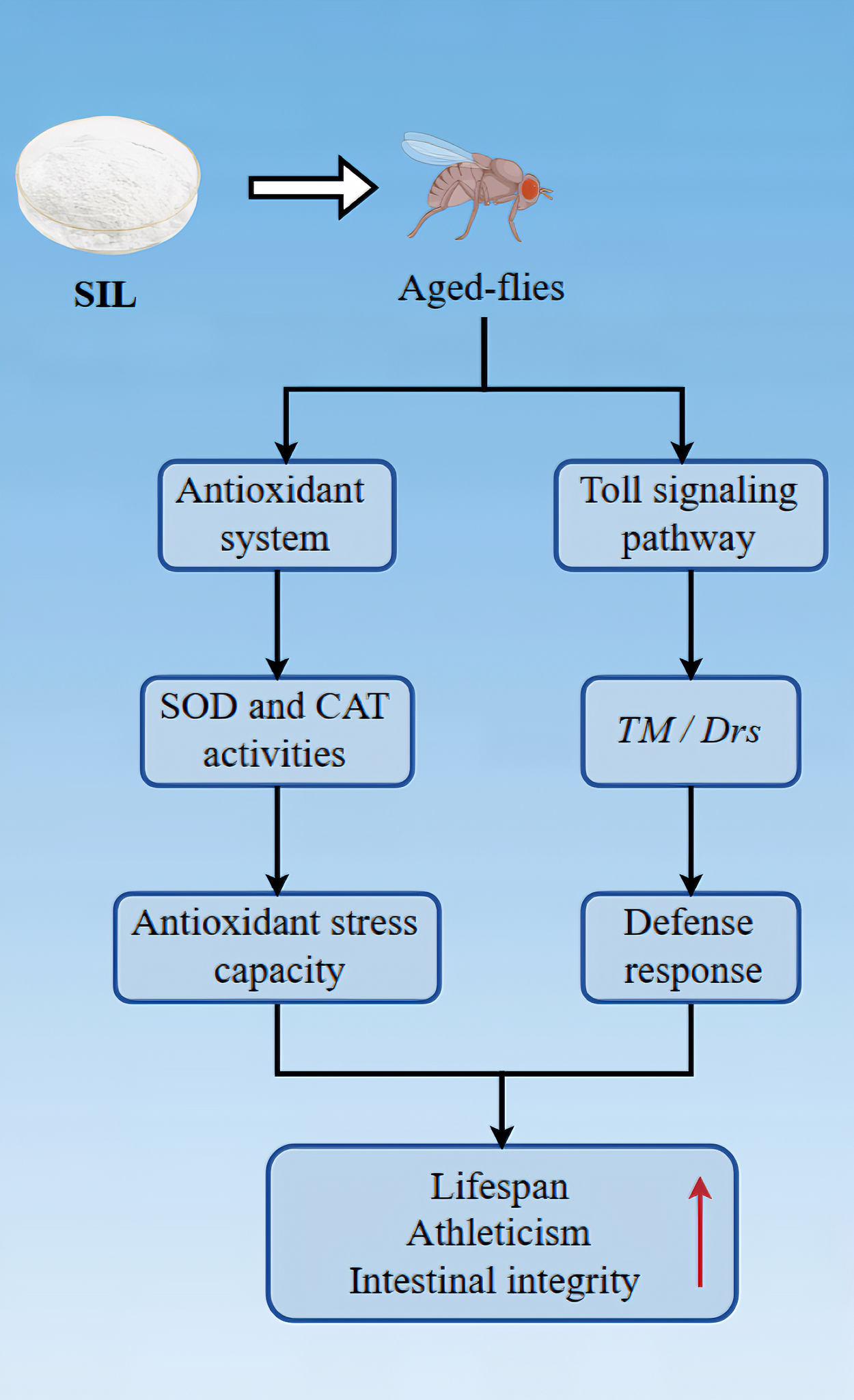

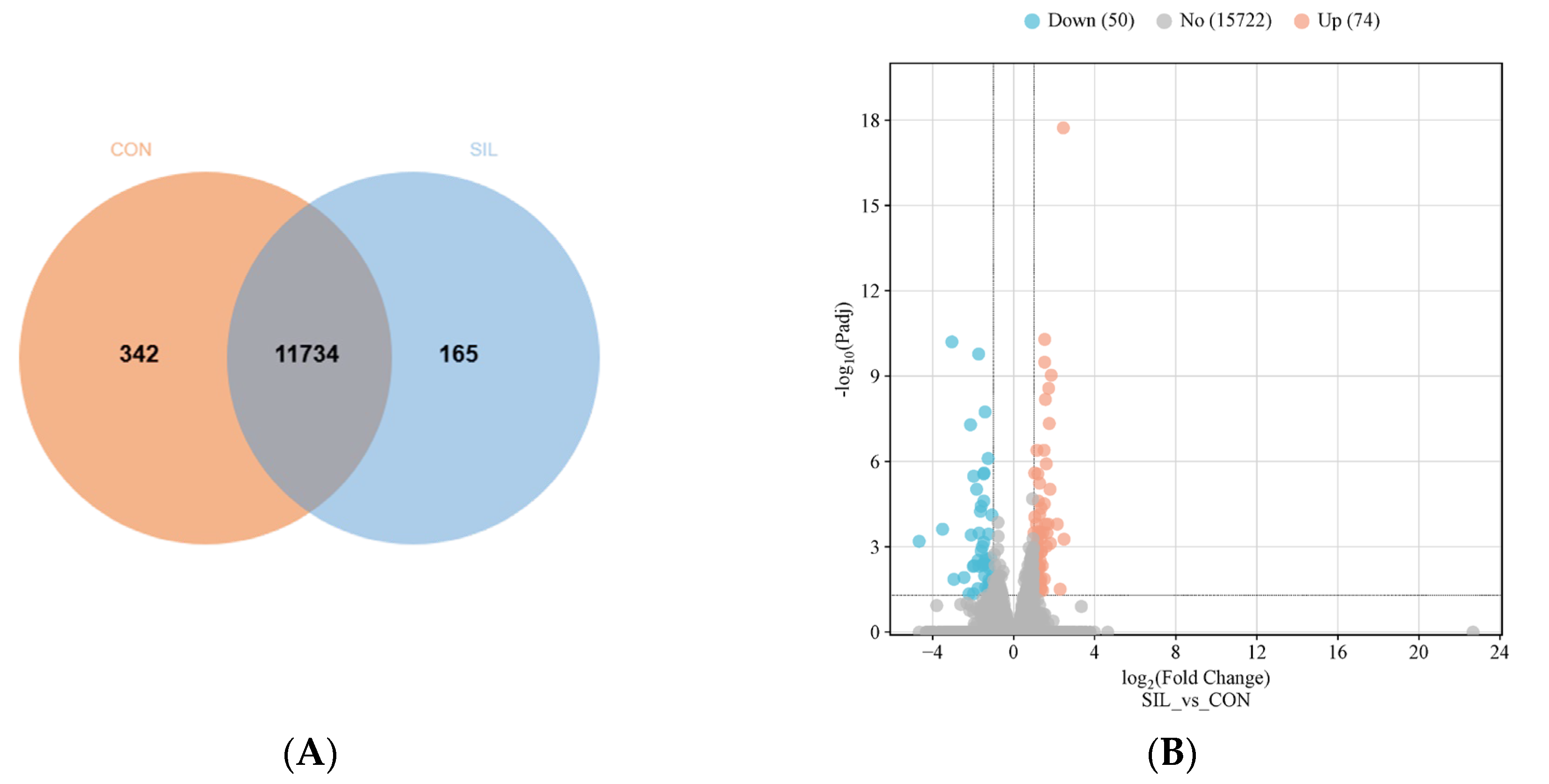

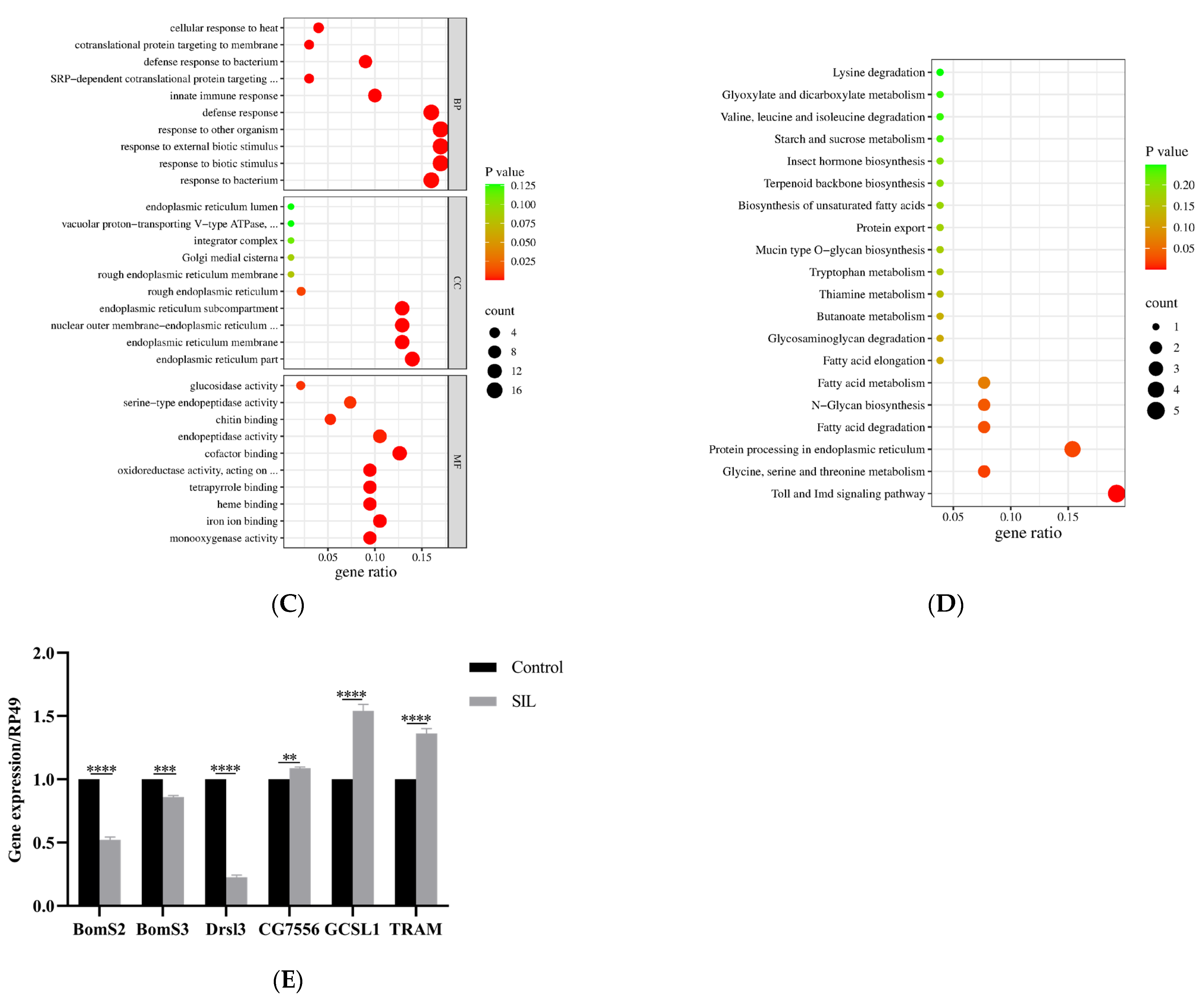

3.6. SIL Inhibits Toll Signaling Pathway and Activates ER Proteins Processing-Related Pathway in Flies

To identify key functional gene sets that may associate with SIL anti-aging, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) on 30-day-old fruit flies treated without (as control) and with SIL (1.2 mg/ml). The expression profiles of approximately 12,000 genes were obtained from the sequencing database, and further bioinformatic analysis showed that more than 80% of these genes were expressed in both groups (

Figure 7A), suggesting that SIL does not exert its anti-aging effects by altering sleep-regulating genes. The transcript levels of 124 key genes were significantly altered due to long-term treatments with SIL. Among them, 74 genes were upregulated and 50 genes were downregulated in SIL-treated groups compared with control groups (

Figure 7B and Supplementary dataset 1 and dataset 2). To explore the biological functions of differentially expressed genes, we conducted Gene ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis. The results showed that altered genes by SIL were mainly involved in biological processes such as response to bacterium, response to biotic stimulus, defense response, innate immune response, cotranslational protein targeting to membrane and cellular response to heat. (

Figure 7C and Supplementary Dataset 3).

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses revealed that differentially expressed mRNAs were mainly involved in 5 pathways including the Toll signaling pathway, Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum (ER), fatty acid degradation and N-Glycan biosynthesis (

Figure 7D and Supplementary Dataset 4). The Toll signaling pathway was downregulated significantly, suggesting that supplementation with SIL inhibited the activity of this signaling pathway, while protein processing in ER was upregulated markedly following SIL intervention (Supplementary Dataset 4), suggesting the SIL diet promotes the physiological function of ER.

To further validate the expression profile of genes related to SIL’s anti-aging effects, we measured the expression of six genes associated with the Toll signaling pathway and ER protein process using qRT-PCR technique. The results showed that the mRNA expression levels of

IM2,

IM3 and

Drsl3 from Toll signaling pathway were significantly reduced compare to the control group, while

CG755,

GCSL1 and

TRAM (ER protein process) expressions were significantly higher than those in the control group (

Figure 7E). Put together, these results indicate that SIL supplementation inhibits the activation of Toll, meantime promotes the protein processing in ER in aged flies.

4. Discussion

Aging is a progressive decline in physiological functions that accompanies the senescence of organisms, and the incidence of many diseases increases with age [

46]. What is the mechanism of aging? How to delay aging? These questions are hot topics for scientists to investigate. Natural compounds derived from plants have been identified as potential candidates for delaying aging and treating aging-related diseases [

47].

Drosophila melanogaster is a model organism widely used in studying disease- and aging-related mechanisms, as well as in drug screening. This article explored the effects of SIL on anti-aging in

Drosophila melanogaster. The dietary addition of SIL significantly improved the lifespan, motility, and intestinal integrity in fruit flies, while there was no difference in food intake and body weight, indicating that the anti-aging effect of SIL is not due to dietary restrictions.

In different biological models, the extension of lifespan is closely linked to the enhancement of stress tolerance. Numerous environmental stress factors can stimulate organisms to generate excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), induce cellular oxidative stress, disrupt normal redox balance, and result in various adverse effects, ultimately accelerating aging [

48,

49]. El Assar et al. have demonstrated that, due to decreased antioxidant capacity of the body, free radicals cannot be cleared timely, ultimately leading to inflammation, and even death [

50]. The decline in the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD and CAT, accelerates the aging in fruit flies, while the increase in the activity can extend the lifespan [

51,

52]. Kumar et al. have revealed that SIL can reduce oxidative damage and prolong the lifespan of nematodes [

53]. Our findings indicate that SIL can enhance the activity of SOD and CAT, significantly extending the lifespan of fruit flies under H

2O

2 stress, which is consistent with the reports on nematodes.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that dietary supplements, such as purple sweet potato anthocyanins and apple polyphenols, can enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes and prolong the lifespan of animals [

32,

54]. SIL is a flavonoid substance, indicating that flavonoid maybe have anti-aging effects by scavenging free radicals. In addition to clearing intracellular free radicals, SIL also possesses numerous other biological functions. For instance, it can inhibit the activation of poly (ADP-ribose)-polymerase (PARP), ultimately leading to the restoration of NAD

+ levels, SIRT1 activity, and AMPK phosphorylation levels [

29]. Liu et al. found that SIL can reduce apoptosis of hippocampal neurons in over-trained rats, delay cell aging, and alleviate learning and memory impairment in rats [

55]. Guo et al. demonstrated that SIL can improve H

2O

2 induced apoptosis of trophoblast cells and enhance oxidative stress response by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway [

28]. The current research shows that SIL can improve the intestinal inflammatory response of fruit flies by regulating the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway [

30]. Our research suggests that SIL-addition can inhibit the activity of Toll signaling pathway in aged fruit flies and promote the expression of processing proteins in ER. These results indicate that SIL is involved in numerous biological processes. However, whether these signaling pathways and biological processes regulated by SIL more or less involved in regulating the aging of animals? These are topics worth studying in the future.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this study is to investigate the effects of dietary supplementation with SIL on the anti-aging in Drosophila melanogaster. The SIL supplementation dramatically extended lifespan, improved the locomotor ability, ameliorated age-associated intestinal barrier disruption, and enhanced antioxidant ability. The food intake and body weight were not affected in flies treated with SIL. The Toll signaling pathway was found to be inhibited, while the ER proteins processing-related pathway was activated.

The results indicates that SIL strongly exhibits anti-aging effects by enhancing antioxidant capacity and regulating aging-related signaling pathways, and therefore SIL shows potential application in the production of functional food products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Supplementary dataset 1: The 74 genes upregulated in the SIL-treated groups compared with control groups; Supplementary dataset 2: The 50 genes downregulated in the SIL-treated groups compared with control groups; Supplementary dataset 3: The GO analysis of differentially expressed genes between the flies treated with or without SIL; Supplementary dataset 4: The KEGG pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between the flies treated with or without SIL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z, D.C. and D.D.; methodology, D.C.; software, K.Z.; validation, H.N., E.H. and Y.H.; investigation, K.Z.; resources, D.C.; data curation, D.C. and D.D.; writing-original draft preparation, K.Z.; visualization, F.H.; project administration, D.C.; funding acquisition, D.C. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by the National Science Foundation of China (31071266), the funding of Anhui Provincial Key Laboratory of Molecular Enzymology and Mechanism of Major Metabolic Diseases (Fzmx202006), the Project of Anhui Provincial Department of Human Resources and Social Security (2019H220). Key R&D and achievement transformation of Wuhu (2023yf001).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Qingchun Tong for critical readings of the manuscript, Xiao-Yan Ma and Hao Yan for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, S.; Sharpless, N.E. ; Senescence in health and disease. Cell. 2017, 169, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomini, F.; Rodella, L.F.; Rezzani, R. Metabolic syndrome, aging and involvement of oxidative stress. Aging Dis. 2015, 6, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.L.; Wu, P.F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.J.; Shen, Z.C.; Luo, H.; Chen, H.; Long, L.H.; Chen, J.G.; Wang, F. Dimethyl sulfide protects against oxidative stress and extends lifespan via a methionine sulfoxide reductase A-dependent catalytic mechanism. Aging Cell. 2017, 6, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.; Sheng, J.; Carlson, J.; Wang, S. Aging-induced fragility of the immune system. J. Theor Biol. 2021, 510, 110473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaranayake, T.; Shaw, A.C. Host resistance and immune aging. Clin Geriatr. Med. 2016, 32, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattabiraman, G.; Palasiewicz, K.; Galvin, J.P.; Ucker, D.S. Aging-associated dysregulation of homeostatic immune response termination (and not initiation). Aging Cell. 2017, 16, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, E.J.; Palmer, J.L.; Fortin, C.F.; Fülöp, T. Jr.; Goldstein, D.R.; Linton, P.J. Aging and innate immunity in the mouse: impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Trends Immunol. 2009, 30, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowden, J.; Renshaw-Hoelscher, M.; Engleman, C.; Katz, J.; Sambhara, S. Innate immunity in aging: impact on macrophage function. Aging Cell. 2004, 3, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badinloo, M.; Nguyen, E.; Suh, W.; Alzahrani, F.; Castellanos, J.; Klichko, V.I. Orr, W.C.;Radyuk, S.N. Overexpression of antimicrobial peptides contributes to aging through cytotoxic effects in Drosophila tissues. Arch Insect. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 98, e21464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, D.E.; Kistner, T.M.; Richard, D.; Lee, I.M.; Baggish, A.L. The active grandparent hypothesis: Physical activity and the evolution of extended human healthspans and lifespans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2021, 118, e2107621118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, O.; Youm, Y.; Shchukina, I.; Ryu, S.; Sidorov, S.; Ravussin, A.; Nguyen, K.; Aladyeva, E.; Predeus, A.N.; Smith, S.R.; Ravussin, E.; Galban, C.; Artyomov, M.N. Dixit, V.D. Caloric restriction in humans reveals immunometabolic regulators of health span. Science. 2022, 375, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Gollapalli, K.; Mangiola, S.; Schranner, D.; Yusuf, M.A.; Chamoli, M.; Shi, S.L. Lopes Bastos, B.; Nair, T.; Riermeier, A.; Vayndorf, E.M. Wu, J.Z. Nilakhe, A.; Nguyen, C.Q.; Muir, M.; Kiflezghi, M.G.; Foulger, A.; Junker, A.; Devine, J.; Sharan, K.; Chinta, S.J.; Rajput, S.; Rane, A.; Baumert, P.; Schönfelder, M.; Iavarone, F.; di Lorenzo, G.; Kumari, S.; Gupta. A.; Sarkar, R.; Khyriem, C.; Chawla, A.S.; Sharma, A.; Sarper, N.; Chattopadhyay, N.; Biswal, B.K.; Settembre, C.; Nagarajan, P.; Targoff, K.L.; Picard, M.; Gupta, S.; Velagapudi, V.; Papenfuss, A.T. Kaya, A.; Ferreira, M.G.; Kennedy, B.K.; Andersen, J.K.; Lithgow, G.J.; Ali, A.M.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Palotie, A.; Kastenmüller, G.; Kaeberlein, M.; Wackerhage, H.; Pal, B.; Yadav, V.K. Taurine deficiency as a driver of aging. Science. 9257. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, M.; Schriner, S.E.; Kil, Y.S.; Pham, S.T.; Seo, E.K. Angelica keiskei impacts the lifespan and healthspan of Drosophila melanogaster in a sex and strain-dependent manner. Pharmaceuticals. 2023, 16, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Lin, X.; Xiu, M.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Gastrodin extends the lifespan and protects against neurodegeneration in the Drosophila PINK1 model of Parkinson's disease. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 7816–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, L.; Tong, A.; Zhen, H.; Han, D.; Yuan, H.; Li, F.; Wang, C.; Fan, G. Anti-aging effect of Agrocybe aegerita polysaccharide through regulation of oxidative stress and gut microbiota. Foods. 2022, 11, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang X, Jin C, Qiao J, Wang C, Jiang L, Yu S, Pan D, Zhao D, Wang S, Liu M. Total ginsenosides extend healthspan of aging Drosophila by suppressing imbalances in intestinal stem cells and microbiota. Phytomedicine. 2024, 129, 155650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, S.; Lüersen, K.; Wagner, A.E.; Rimbach, G. Drosophila melanogaster as a versatile model organism in food and nutrition research. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3737–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Yoshidam, H. Drosophila as a model organism. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1076, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, M.A.; Tan, F.H.P.; Azlan, A.; Rasyid, I.I.; Rosli, N.; Shamsuddin, S.; Azzam, G. Ageing, Drosophila melanogaster and epigenetics. Malays. J. Med Sci. 2020, 27, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.; Metcalfe, N.H. Drosophila melanogaster: a fly through its history and current use. J. R. Coll. Physician.s Edinb. 2013, 43, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffar, H.M.; Al-Asmari, F.; Khan, F.A.; Rahim, M.A.; Zongo, E. Silymarin: Unveiling its pharmacological spectrum and therapeutic potential in liver diseases-A comprehensive narrative review. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 3097–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Kong, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, W.; Ma, L.; Jiang, S.; Ren, W.; Du, L.; Ma, W.; Liu, X. A review of the botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, synthetic biology and comprehensive utilization of Silybum marianum. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1417655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, J.; Sotoodehnejadnematalahi, F.; Shokouhifar, A.; Rahimi, M.; Sodeifi, N.; Sahranavardfar, P.; Azimi, M.; Janzamin, E.; Safa, M.; Ebrahimi, M. Silibinin exhibits anti-tumor effects in a breast cancer stem cell model by targeting stemness and induction of differentiation and apoptosis. Bioimpacts. 2022, 12, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deep, G.; Kumar, R.; Nambiar, D.K.; Jain, A.K.; Ramteke, A.M.; Serkova, N.J.; Agarwal, C.; Agarwal, R. Silibinin inhibits hypoxia-induced HIF-1α-mediated signaling, angiogenesis and lipogenesis in prostate cancer cells: In vitro evidence and in vivo functional imaging and metabolomics. Mol Carcinog. 2017, 56, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zheng, F.; Lin, F. Silibinin restores the sensitivity of cisplatin and taxol in A2780-resistant cell and reduces drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Cancer. Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 7111–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boojar, M. M. A.; Boojar, M. M. A.; Golmohammad, S. Overview of Silibinin anti-tumor effects. Herbal. Medicine. 2020, 23, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.P.; Islam, M.A. ; Islam. M.S. Han, A.; Geng, P., Aziz, M.A., Eds.; Mamun, A.A. A comprehensive evaluation of the therapeutic potential of silibinin: a ray of hope in cancer treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1349745. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D. Silibinin ameliorats H2O2-induced cell apoptosis and oxidative stress response by activating Nrf2 signaling in trophoblast cells. Acta. Histochem. 2020, 122, 151620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomone, F.; Barbagallo, I.; Godos, J.; Lembo, V.; Currenti, W.; Cinà, D.; Avola, R.; D'Orazio, N.; Morisco, F.; Galvano, F.; Li Volti, G. Silibinin restores NAD⁺ levels and induces the SIRT1/AMPK pathway in non-alcoholic fatty liver. Nutrients. 2017, 9, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, L.; Ye, J.; Zhao, X.; Ren, G.; Chen, H. Silibinin alleviates intestinal inflammation via inhibiting JNK signaling in Drosophila. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1246960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.; Mishra, A.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Siddiquie, S. Recapitulation of evidence of phytochemical, pharmacokinetic and biomedical application of silybin. Drug. Res. (Stuttg). 2021, 71, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Guo, Y.; Cui, S.W.; Li, H.; Shan, Y.; Wang, H. Purple Sweet Potato Extract extends lifespan by activating autophagy pathway in male Drosophila melanogaster. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 144, 111190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Han, Y.; Pei, Y.; Guo, Y.; Cui, S.W. Purple sweet potato extract maintains intestinal homeostasis and extend lifespan through increasing autophagy in female Drosophila melanogaster. J. Food Biochem. 2021, e13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Zheng, X.; Liu, L.; Hua, Y.; Du, B.; Zhao, G.; Yu, J.; Zhuo, Z.; Xie, Z.; Ji, S. Aspirin positively contributes to Drosophila intestinal homeostasis and delays aging through targeting Imd. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1821–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhen, H.; Zhao, L.; Wu, H.; Liu, B.; Fan, G.; Tong, A. Agrocybe aegerita polysaccharide combined with bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12 attenuates aging-related oxidative stress and restores gut microbiota. Foods. 2023, 12, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Couteur, D.G.; Raubenheimer, D.; Solon-Biet, S.; de Cabo, R.; Simpson, S.J. Does diet influence aging? Evidence from animal studies. J. Intern Med. 2024, 295, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorling, J.L.; van Vliet, S.; Huffman, K.M.; Kraus, W.E.; Bhapkar, M.; Pieper, C.F.; Stewart, T.; Das, S.K.; Racette, S.B.; Roberts, S.B.; Ravussin, E.; Redman, L.M.; Martin, C.K. ; CALERIE Study Group. Effects of caloric restriction on human physiological, psychological, and behavioral outcomes: highlights from CALERIE phase 2. Nutr. Rev.

- Zhong, L.; Yang, Z.; Tang, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, J. Differential analysis of negative geotaxis climbing trajectories in Drosophila under different conditions. Arch. Insect. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 111, e21922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, A.M.; Aparicio, R.; Clark, R.I.; Rera, M.; Walker, D.W. Intestinal barrier dysfunction: an evolutionarily conserved hallmark of aging. Dis. Model. Mech. 2023, 16, dmm049969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Gu, Y.; Dai, X. Protective effect of bilberry anthocyanin extracts on dextran sulfate sodium-induced intestinal damage in Drosophila melanogaster. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.J.; Li, X.J.; Liu, W.; Chai, X.J.; Zhu, X.Y.; Sun, P.H.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.K.; Huang, J.L.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhao, S.T. Eucommia polysaccharides ameliorate aging-associated gut dysbiosis: A potential mechanism for life extension in Drosophila. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Li, Q.; Zhang, G.; Ma, C.; Dai, X. The Protective effects of carrageenan oligosaccharides on intestinal oxidative stress damage of female Drosophila melanogaster. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021, 10, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.M.; Lei. L.; Liu. Y.; Wang. X.; Ma. K.Y.; Chen, Z.Y. Cranberry anthocyanin extract prolongs lifespan of fruit flies. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 69, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S; Zhao, Y. ; Wang, C.; Li. K.; Jin. Z.; Qiao, J.; Liu, M. Studies on the regulation and molecular mechanism of Panax ginseng saponins on senescence and related behaviors of Drosophila melanogaster. Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2022, 14, 870326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, G.J.T.; Ecker, A.; Adefegha, S.A.; da Costa, J.G.M. Advances in evaluation of antioxidant and toxicological properties of stryphnodendron rotundifolium Mart. in Drosophila melanogaster model. Foods. 2022, 11, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- la Torre, A.; Lo Vecchio, F.; Greco, A. Epigenetic mechanisms of aging and aging-associated diseases. Cells. 2023, 12, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, X.; Luo, X.; Lou, X.; Li, P.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Antiaging effects of dietary supplements and natural products. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1192714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongchum, N.; Dechakhamphu, A. Xanthohumol prolongs lifespan and decreases stress-induced mortality in Drosophila melanogaster. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 244, 108994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barouki, R. Stress oxydant et vieillissement [Ageing free radicals and cellular stress]. Med. Sci. (Paris). 2006, 22, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Assar, M.; Angulo, J.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Frailty as a phenotypic manifestation of underlying oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 149, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, H.F.; Tao, Z.; Yuan, C.; Jiang, Z.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Kurihara, H.; Xu, W.D. Ganoderma lucidum spore oil (GLSO), a novel antioxidant, extends the average life span in Drosophila melanogaster. Food Science. and Human Wellness. 2021, 10, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepashree, S.; Shivanandappa, T.; Ramesh, S.R. Genetic repression of the antioxidant enzymes reduces the lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Comp Physiol. B. 2022, 192, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.; Park, K.C.; Awasthi, A.; Prasad, B. Silymarin extends lifespan and reduces proteotoxicity in C. elegans Alzheimer's model. CNS. Neurol. Disord. Drug. Targets.

- Peng, C.; Chan, H.Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, Z.Y. Apple polyphenols extend the mean lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, W.; Liu, P.; Liu, X.; Song, X.; Hayashi, T.; Onodera, S.; Ikejima, T. Silibinin alleviates the learning and memory defects in overtrained rats accompanying reduced neuronal apoptosis and senescence. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 1818–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).