Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

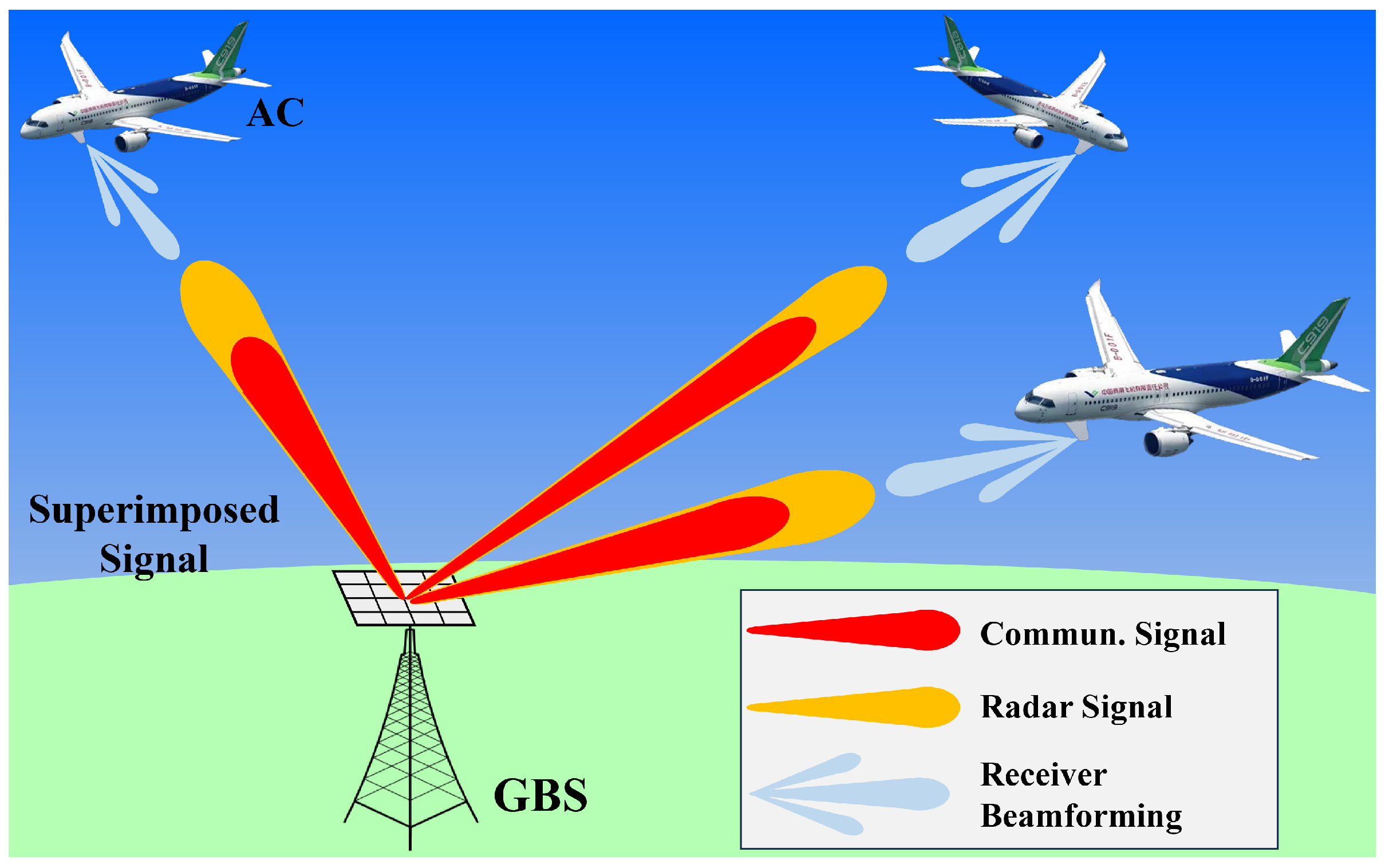

The novel framework of an integrated aeronautical communication and radar system (IACRS) to realize spectrum sharing is investigated. A non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA)- motivated multi-input-multi-output (MIMO) scheme is proposed for the dual-function system, which is able to detect multiple aircraft while simultaneously transmitting dedicated messages. Specifically, NOMA-inspired technology is utilized to enable the dual-spectrum sharing. The superposition of communication and radar signals is facilitated in the power domain, with successive interference cancellation (SIC) employed at the receiver to effectively mitigate inter-function interference. Subsequently, the regularity of three-dimensional flight track and attitude is exploited to model the air-to-ground (A2G) MIMO channel. Based on this framework, a joint optimization problem is formulated to maximize the weighted achievable sum rate and the sensing signal-clutter-noise ratio (SCNR), while satisfying the rate requirements for message transmission and ensuring the radar detection threshold. An alternative optimization (AO) algorithm is proposed to solve the non-convex problem with highly coupled variables. The original problem is decoupled into two manageable subproblems: transmit beamforming of ground base station combined with power allocation and receiver beamforming at the aircraft. The penalty-based approach and the successive rank-one constraint relaxation (SROCR) method are developed for handling the non-convex rank-one constraints in subproblems iteratively. Numerical simulations demonstrate that the proposed IACRS framework significantly outperforms benchmark schemes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.1.1. Studies on RCC

1.1.2. Studies on ISAC

1.2. Motivation and Contributions

- We in investigate an integrated transmission framework for aeronautical communication and radar system, in which MIMO is utilized at the GBS and ACs to facilitate flexible multiple access scheme, and NOMA is deployed to realize dual-spectrum sharing between the communication and the navigation avionic devices. Given the proposed framework, we formulate a weighted achievable sum rate and the sensing SCNR maximization problem. Aiming for the joint optimization of the GBS transmit BF, the airborne receivers BFs, as well as the power allocation, the minimum operation requirements of both the communication and radar functions is guaranteed.

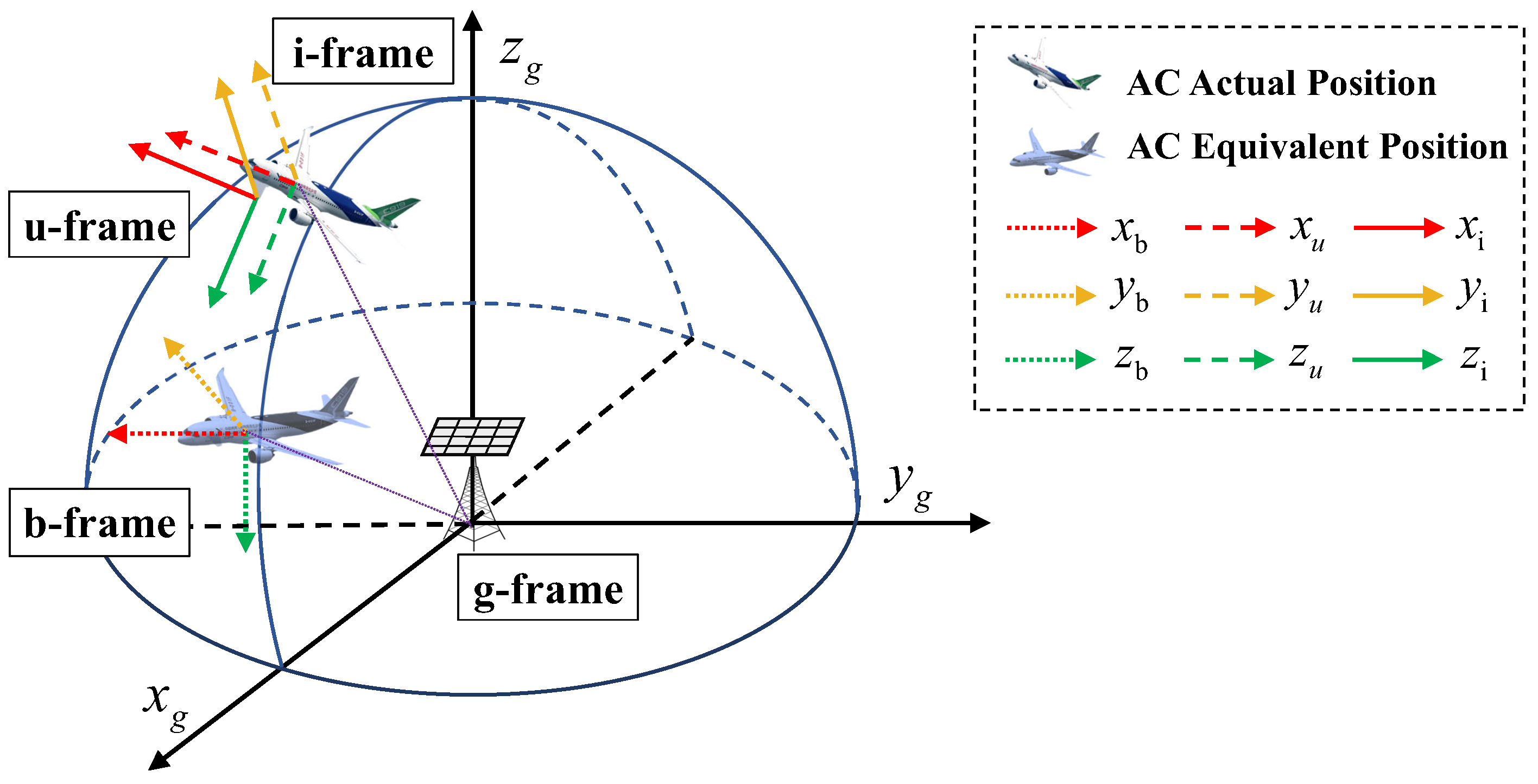

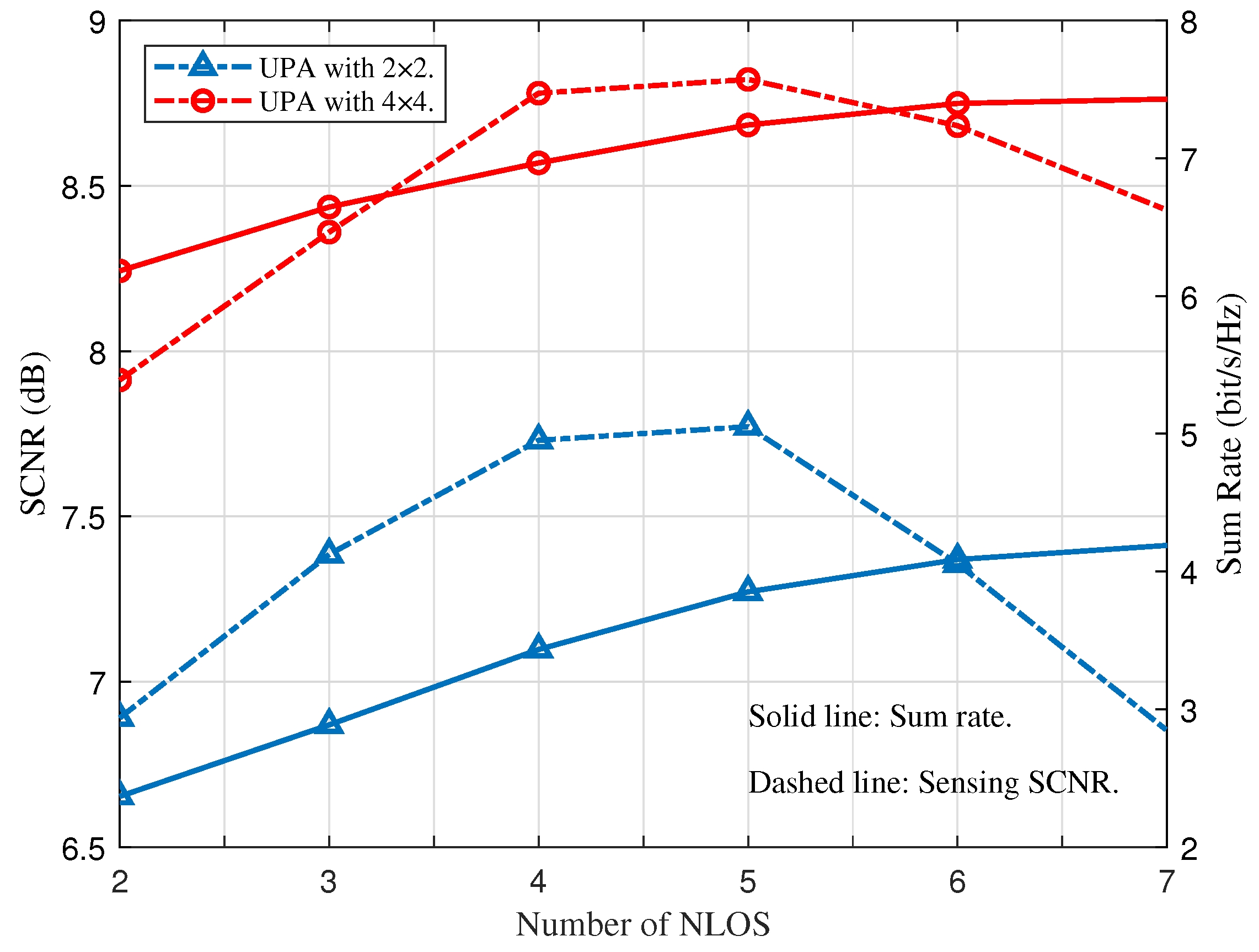

- A practical A2G MIMO channel model accounting for the AC dynamics is proposed. This model considers both the AC position and attitude to characterize the steering directions. A rotation matrix is constructed with the AC attitude represented by Euler angles (i.e., heading angle, pitch angle, and roll angle) to derive an equivalent position (EP) given the AC’s current position. Consequently, the realistic angle-of-arrivals (AoAs)/angle-of-departures (AoDs) can be obtained by leveraging the geometrical information.

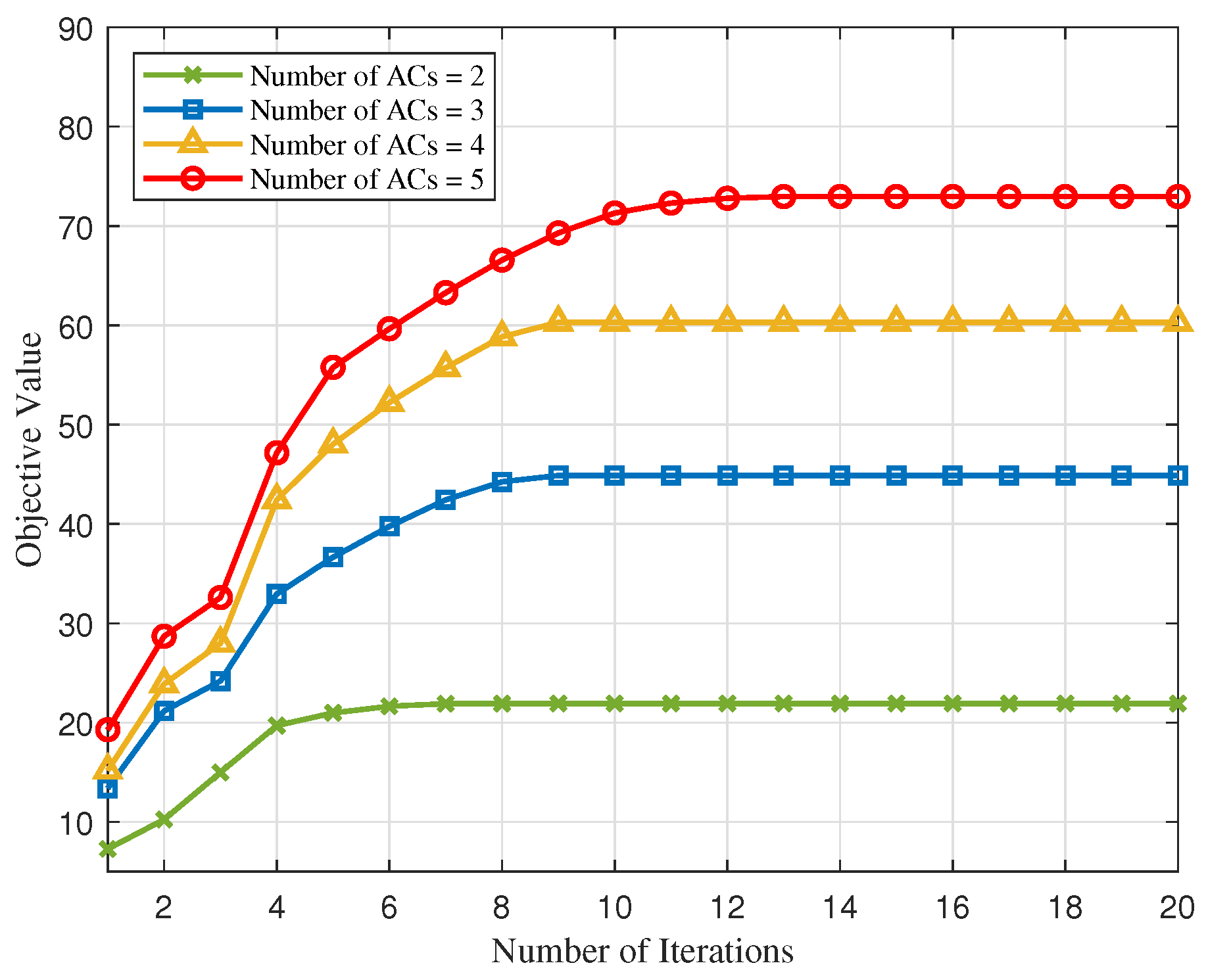

- We develop an alternating optimization (AO) algorithm, where the original problem is decomposed into two subproblems that are solved alternatively. By combining the GBS transmit BF and the power allocation subproblems, we construct the auxiliary variables which incorporate the optimization variables, so as to simplify the optimization process. Afterwards, the penalty-based method is invoked to handle the non-convex constraint for the covariance matrix of BF. For the airborne receivers BFs design, we effectively solve them by utilizing the sequential rank-one constraint relaxation (SROCR) while fixing the other optimization variables.

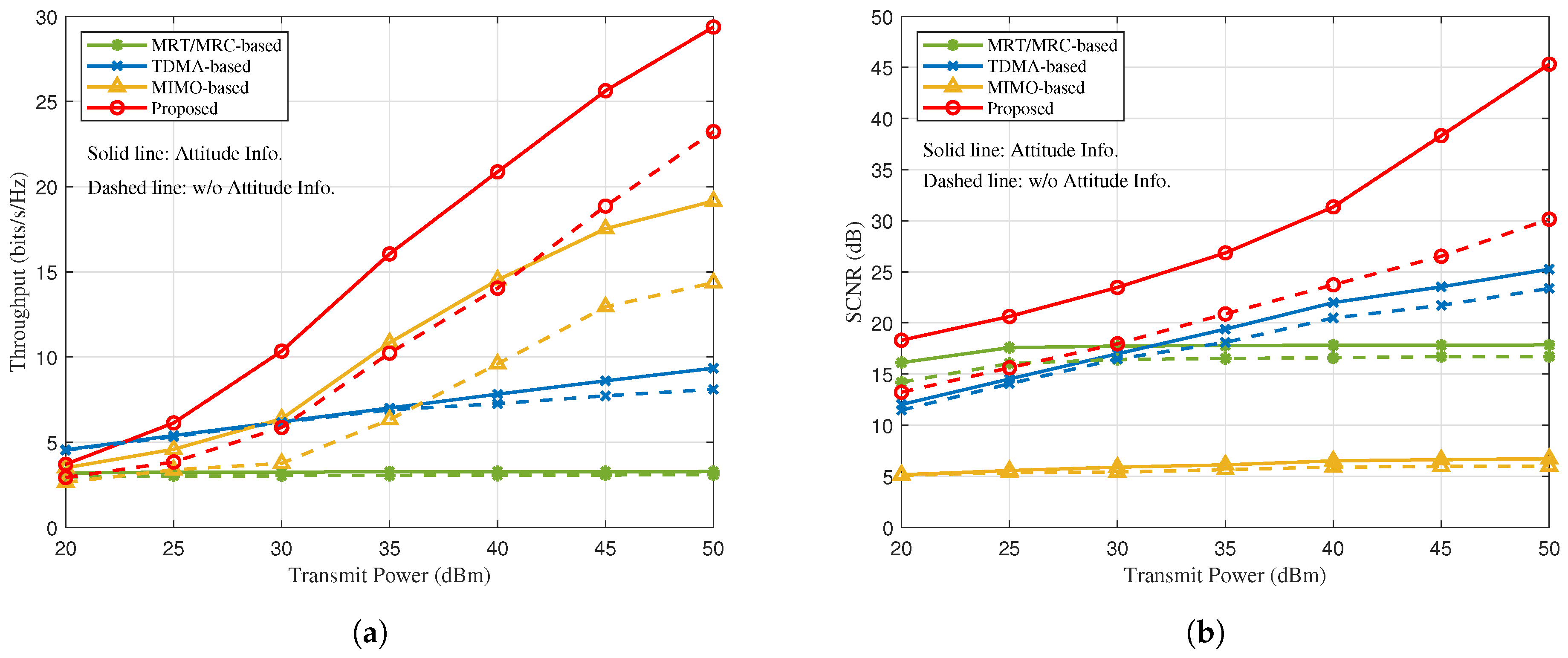

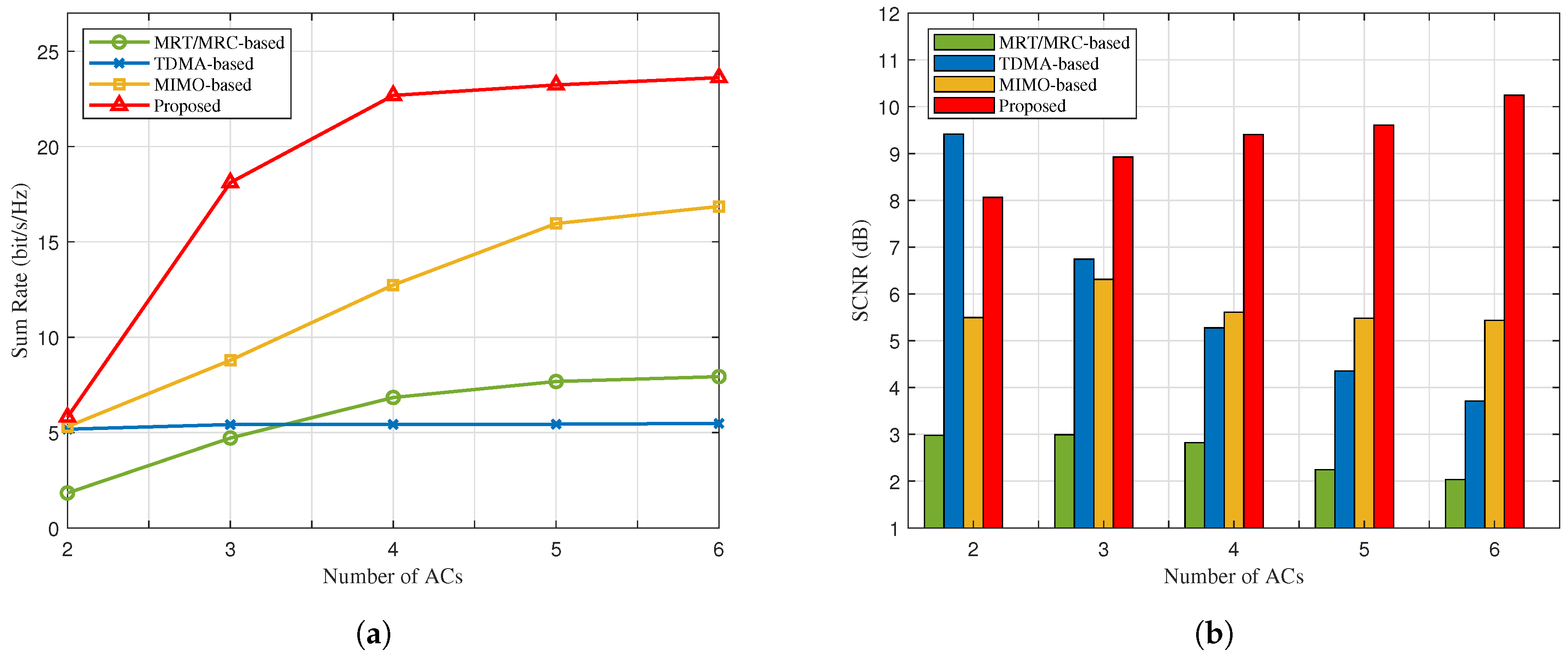

- Our numerical results indicate that the proposed algorithm achieves superior sum rate performance and sensing performance compared to the benchmark schemes for the dual-function of communication and radar. It is demonstrated that the proposed NOMA-motivated MIMO IACRS schemes are capable of significantly boosting the performance of A2G datalink to support ACs receive messages, while simultaneously constructing a high-quality radar detection capability. Furthermore, the system performance gain becomes more significant, when the AC’s attitude is considered.

1.3. Organization and Notation

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

2.1. System Description

2.2. Channel Model

2.3. Coordinate Transformation

- The GBS-geodetic coordinate frame (g-frame): Its origin is chosen as the center of gravity of the GBS-UPA, and its axis and are aligned with the directions of east and north, respectively. The axis is perpendicular to the ground surface pointing upwards, thus completing a right-handed coordinate frame. We assume that the row and column of the GBS-UPA are aligned with the axes and , respectively.

- The AC-body coordinate frame (b-frame): Its origin is the AC center of gravity (ACCG). The axes , and are aligned with its longitudinal (forward), lateral (right), and vertical (downward) direction respectively, which are parallel to , and , respectively.

- The inertial reference frame (i-frame): Its origin coincides with the ACCG, and its axes (roll axis) and (pitch axis) point out along the direction of the AC’s head and starboard wing, respectively. And its axis (yaw axis) points downward, completing a right-handed coordinate frame.

- The AC-UPA coordinate frame (u-frame): Its origin is chosen as the AC-UPA center of gravity. The axes and are aligned with the row and column of the AC-UPA, respectively. The axis is perpendicular to the plane spanned by the axes and . We assume that the axes , and are parallel to , and , respectively. On the basis of the relationship of u-frame and i-frame, the u-frame would be consistent with the i-frame when the attitude of AC changes.

2.4. Problem Formulation

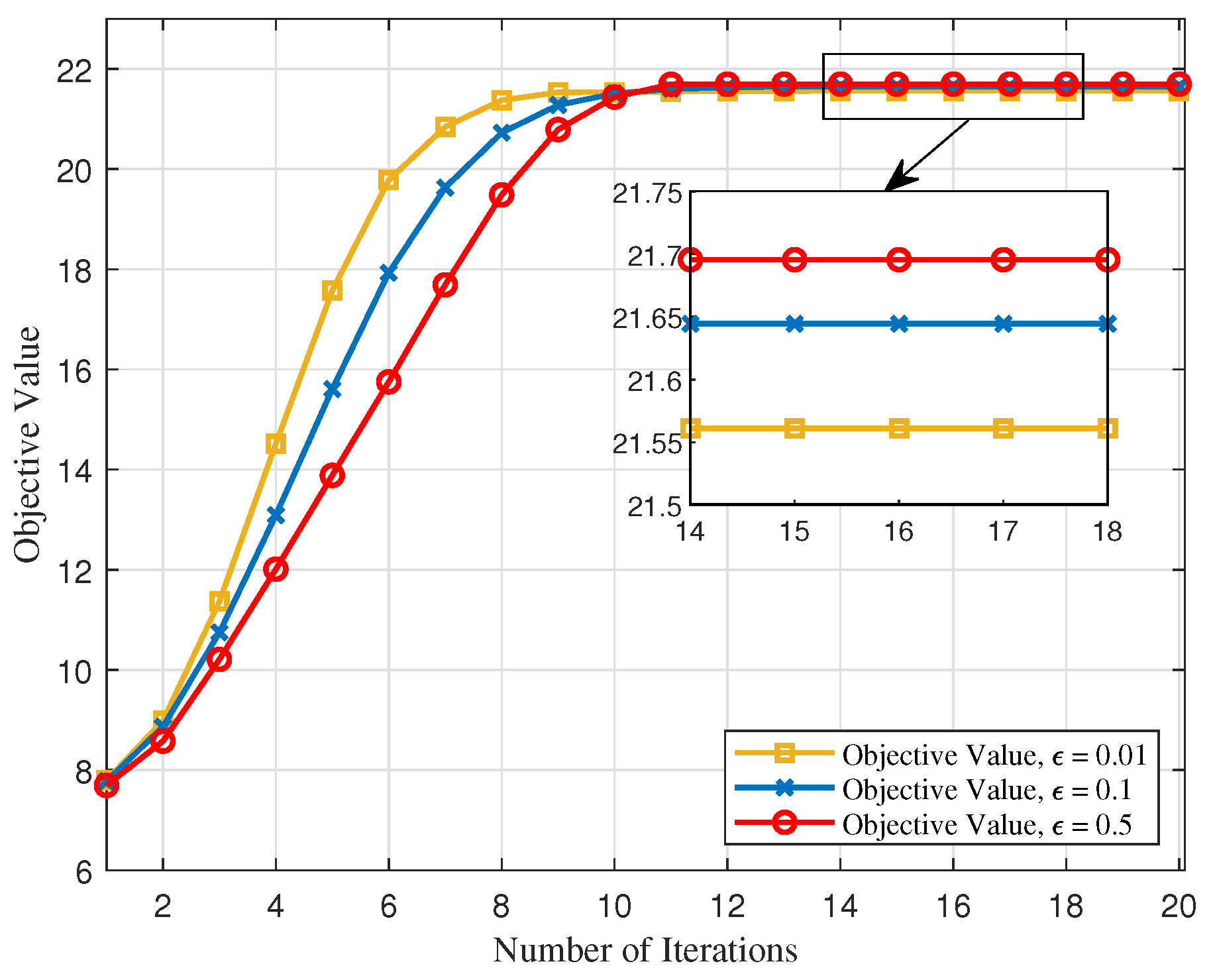

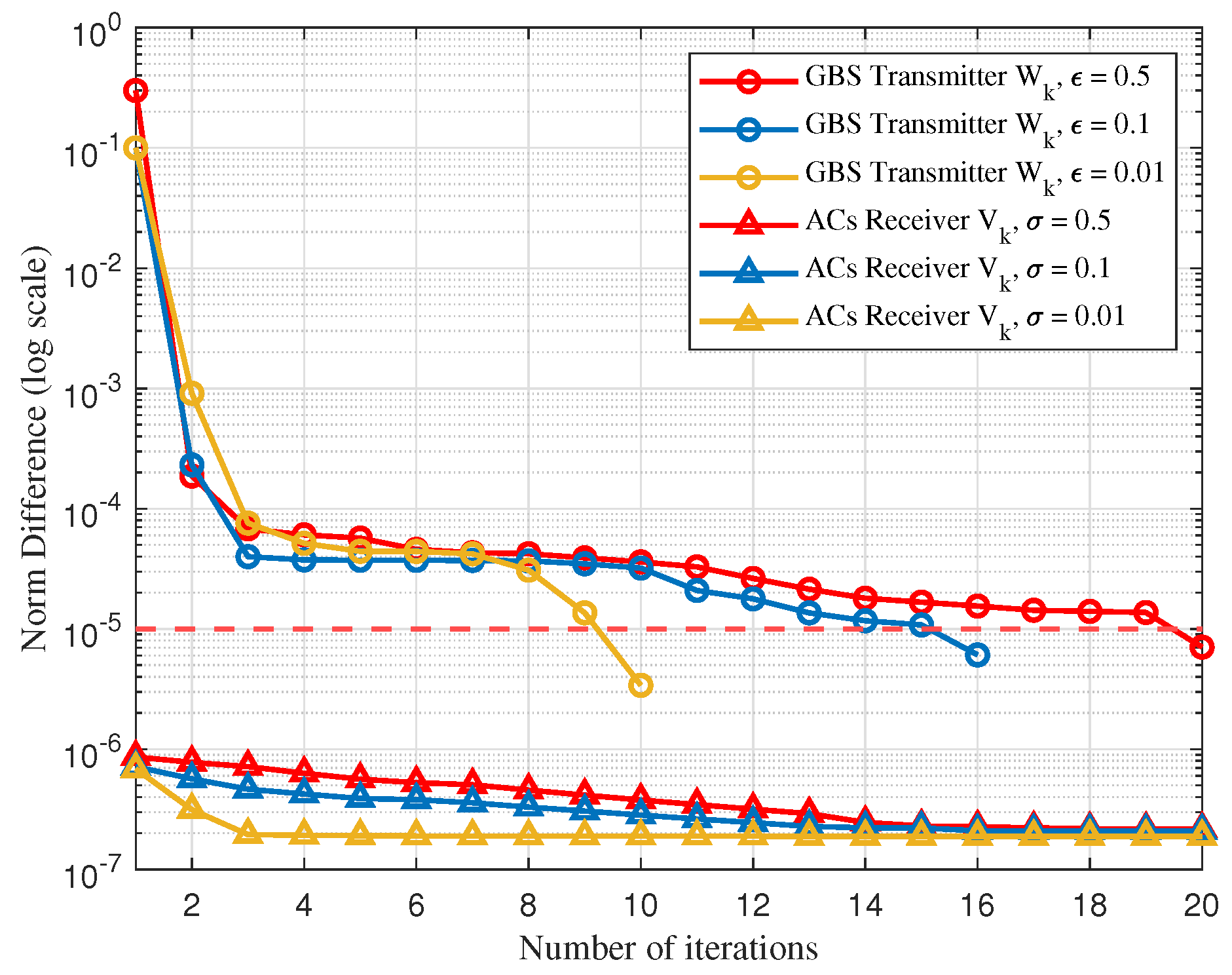

3. AO-Based Alternative Optimization Algorithm

3.1. GBS Transmit BFs Design and Power Allocation

| Algorithm 1 Penalty-based approach to solve the joint transmit BF design and power allocation subproblem (34) |

|

3.2. ACs Receiver BFs Design

| Algorithm 2 SROCR method for solving the receiver BF design subproblem (42) |

|

3.3. Complexity Analysis

4. Numerical Results

-

TDMA-based dual-function scheme: In this scheme, the GBS with multi-antenna successively transmits dedicated messages and interrogation detecting singal to ACs over time slots employing one common BF. Accordingly, for TDMA-based scheme, the sensing SCNR at the k-th AC is given bythe corresponding achievable rate for the k-th AC isThe problem of maximizing sum of and can be solved by using SCA algorithm, as there are no inter-aircraft or inter-function interference terms involved.

- MIMO-based dual-function scheme: In this scheme, the MIMO-only GBS transmits communication data to the ACs employing distinct BFs, which are also simultaneously utilized for the detection of the ACs. Notably, each AC directly receives its intended signal while treating the signals for other ACs as interference without the assistance of SIC, which means a low level of integration. Therefore, the sensing SCNR and the sum rate for the transmitted signal at the AC are similar with (3) and (6), respectively.

- MRT/MRC-based dual-function scheme: In this scheme, the system model is same as the proposed integrated framework, while using a linear transmitter and receiver, maximum-ratio transmission/maximum-ratio combining (MRT/MRC)[35]. Hence, the approximate closed-form expressions of the transmit BFs of GBS and the receiver BFs of ACs can be obtained.

5. Conclusion and Discussion

- A new A2G MIMO channel model that accounts for AC dynamics, including both position and attitude, is introduced to accurately characterize the steering direction. Since the AoDs and AoAs depend on the time-varying position and attitude, the proposed channel model significantly improves system performance, both in the proposed scheme and the baseline.

- To validate the effectiveness of the proposed scheme, it is compared with three baselines. The numerical results demonstrate that the proposed scheme achieves superior dual-function system performance compared to the benchmark schemes. In contrast, the MRT/MRC scheme does not benefit from the NOMA-motivated framework, as it relies only on valid channel information, resulting in inferior communication performance.

- One limitation of our framework is that obtaining accurate CSI becomes challenging due to the time-varying nature of A2G wireless channels and AC mobility, which directly impacts system performance. Addressing imperfect CSI could be a direction for future work. Additionally, the SIC process requires significant computational resources, and in low SNR environments, its performance may degrade substantially, leading to erroneous signal decoding and severely affecting system stability and data transmission quality.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Zhang, J. Aeronautical Mobile Communication: The Evolution from Narrowband to Broadband. Engineering 2021, 7, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, M.; Epple, U.; Shutin, D.; Schneckenburger, N. LDACS: future aeronautical communications for air-traffic management. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neji, N.; de Lacerda, R.; Azoulay, A.; Letertre, T.; Outtier, O. Survey on the Future Aeronautical Communication System and Its Development for Continental Communications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2013, 62, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y.; Yi, P.; Zhang, R.; Xia, X.G.; Schober, R. A Survey on Millimeter-Wave Beamforming Enabled UAV Communications and Networking. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tuts. 2022, 24, 557–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, N.C.; Lu, X.; Hoang, D.T.; Niyato, D.; Kim, D.I. Radio Resource Management in Joint Radar and Communication: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 2021, 23, 780–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Liu, Y.; Choi, J.; Sun, Q.; Elkashlan, M.; Chih-Lin, I.; Poor, H.V. Application of Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access in LTE and 5G Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Elkashlan, M.; Ding, Z.; Nallanathan, A.; Hanzo, L. Nonorthogonal Multiple Access for 5G and Beyond. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 2347–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Elkashlan, M.; Gao, Y.; Hanzo, L. Enhancing the Physical Layer Security of Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access in Large-Scale Networks. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2017, 16, 1656–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Cao, X.; Wu, D.O.; Xia, X.G. Millimeter-Wave NOMA With User Grouping, Power Allocation and Hybrid Beamforming. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2019, 18, 5065–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Lops, M.; Eldar, Y.C.; Wang, X. Radar and Communication Coexistence: An Overview: A Review of Recent Methods. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2019, 36, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Cui, Y.; Masouros, C.; Xu, J.; Han, T.X.; Eldar, Y.C.; Buzzi, S. Integrated Sensing and Communications: Toward Dual-Functional Wireless Networks for 6G and Beyond. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 1728–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Rahman, M.L.; Huang, X.; Guo, Y.J.; Chen, S.; Heath, R.W. Perceptive Mobile Networks: Cellular Networks With Radio Vision via Joint Communication and Radar Sensing. IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag. 2021, 16, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, C.; Zwick, T.; Wiesbeck, W. An OFDM System Concept for Joint Radar and Communications Operations. In Proceedings of the Proc. VTC Spring- IEEE 69th Veh. Technol. Conf. IEEE, Barcelona, Spain, Jun. 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, N.; Darak, S.J.; Bader, F. Spectral Coexistence of LDACS and DME: Analysis via Hardware Software Co-Design in Presence of Real Channels and RF Impairments. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 9837–9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, C.; Wiesbeck, W. Waveform Design and Signal Processing Aspects for Fusion of Wireless Communications and Radar Sensing. Proc. IEEE 2011, 99, 1236–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhou, L.; Masouros, C.; Li, A.; Luo, W.; Petropulu, A. Toward Dual-functional Radar-Communication Systems: Optimal Waveform Design. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2018, 66, 4264–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, J.A.; Khawar, A.; Abdelhadi, A.; Clancy, T.C. Spectral Coexistence of MIMO Radar and MIMO Cellular System. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2017, 53, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Lops, M.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; He, Z. Joint System Design for Coexistence of MIMO Radar and MIMO Communication. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2018, 66, 3504–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Gong, Y.; Nallanathan, A. Radar-Aided Beam Selection in MIMO Communication Systems: A Federated Transfer Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 12172–12177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Masouros, C.; Li, A.; Sun, H.; Hanzo, L. MU-MIMO Communications With MIMO Radar: From Co-Existence to Joint Transmission. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2018, 17, 2755–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Wang, W.; Hu, Z.; Hui, T. Low-Complexity Beamformer Design for Joint Radar and Communications Systems. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2021, 25, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Wang, W.; Masouros, C. Joint Radar-Communication Transmission: A Generalized Pareto Optimization Framework. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 2752–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsinos, C.G.; Arora, A.; Chatzinotas, S.; Ottersten, B. Joint Transmit Waveform and Receive Filter Design for Dual-Function Radar-Communication Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 15, 1378–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gao, F.; Wu, Q.; Jin, S.; Wu, Y.; Jia, W. Beam Tracking for UAV Mounted SatCom on-the-Move With Massive Antenna Array. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2018, 36, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, W.; Wong, K.K.; Jin, T.; An, K. Waveform Design of DFRC System for Target Detection in Clutter Environment. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Du, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, F.R. Generalized Transceiver Beamforming for DFRC With MIMO Radar and MU-MIMO Communication. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 1795–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Mu, X.; Ding, Z.; Dobre, O.A. NOMA Empowered Integrated Sensing and Communication. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2022, 26, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Lin, J.; Hanzo, L. NOMA-Aided Joint Radar and Multicast-Unicast Communication Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 1978–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H. Revealing the Impact of SIC in NOMA-ISAC. IEEE Wireless Commun. Lett. 2023, 12, 1707–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Masouros, C.; Petropulu, A.P.; Griffiths, H.; Hanzo, L. Joint Radar and Communication Design: Applications, State-of-the-Art, and the Road Ahead. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2020, 68, 3834–3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Vaidyanathan, P.P. MIMO Radar Waveform Optimization With Prior Information of the Extended Target and Clutter. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2009, 57, 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Thompson, J.; Poor, H.V. A sequential constraint relaxation algorithm for rank-one constrained problems. In Proceedings of the Proc. 25th Eur. Signal Process. Conf. (EUSIPCO), Kos, Greece, Aug. 2017; pp. 1060–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex optimization; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, U.K., 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, Q.T.; Diehl, M. Local Convergence of Sequential Convex Programming for Nonconvex Optimization. Springer Berlin Heidelberg 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Leukhin, A.; Liu, L. On the Spectral and Energy Efficiency of Full-Duplex Small-Cell Wireless Systems With Massive MIMO. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 2339–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The duration of each time block depends on the coherence time of the A2G channel. |

| Considering Factor | [24] | [25] | [26] | [27,28] | Proposed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-aircraft communication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Multi-aircraft sensing | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Radar interference cancellation | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Deployment of NOMA | × | × | × | multiple-user access in communication | co-located dual-function coordination |

| DME-like sensing requirement | × | × | ✓, but not mentioned | × | ✓ |

| Aircraft attitude | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).