Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This article presents a computational model for Transmission and Generation expansion planning considering the impact of Virtual Power Lines which consists of investment in energy storage in the transmission system, being able to determine the reduction and postponement of investments in transmission lines. The flexibility from the TSO-DSO interconnection is also modeled, analyzing its impact on system expansion investments. Flexibility is provided to the AC power flow transmission network model by distribution systems connected at the transmission system nodes. The Transmission system Flexibility requirements are provided by expansion planning performed by the connected DSOs. The objective of the model is to minimize the overall cost of system operation and investments in transmission, generation and the investments in flexibility requirements. A Data-Driven Distributionally Robust Optimization-DDDRO approach is proposed to consider uncertainties of demand and Variable Renewable Energy generation. The Column and Constraint Generation algorithm and Duality-Free Decomposition method are adopted. Case studies using a Garver 6-node system and the IEEE RTS-GMLC were carried out to validate the model and evaluate the values and impacts of local flexibility on transmission system expansion. The results obtained demonstrate a reduction in total costs, an improvement in the efficient use of the transmission system, and an improvement in the locational marginal price indicator of the transmission system.

Keywords:

1. Nomenclature

1.1. Sets

| Dispatchable generation units | |

| Candidate Dispatchable generation units | |

| Non-Dispatchable generation units | |

| Candidate Non-Dispatchable generation units | |

| VPP Dispatchable generation units | |

| VPP Non-Dispatchable generation units | |

| Battery Storage units | |

| Virtual Power Lines | |

| Virtual Power Plants | |

| Demand stages | |

| Candidate Storage units | |

| Set of nodes in the power transmission network | |

| Set of Lines in the power transmission network, | |

| Set of circuits in the power transmission network line | |

| Set of scenarios | |

| DDDRO Ambiguity Set |

1.2. Indices

| b | Node, |

| c | Line Circuit, |

| Candidate Dispatchable Generation, | |

| Candidate Non-Dispatchable Generation, | |

| h | Battery Storage unit, |

| l | Line, |

| s | Stage, |

| t | Time step, t |

| Virtual Power Line, | |

| Virtual Power plant, | |

| w | Scenario, |

1.3. Input Data and Operators

| Time horizon of the problem | |

| a | Area |

| Susceptance [p.u.] of line l | |

| discount rate | |

| Conductance (p.u.) of line l | |

| Maximum number of circuits of line l | |

| Active Power Capacity of circuit c of line l | |

| apparent Power Capacity of circuit c of line l | |

| Investment cost of additional line circuit at corridor l in time period t [$/circuit] | |

| Investment cost of additional dispatchable generation at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Investment cost of additional Non-Dispatchable generation at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Investment cost of Battery Storage h in time period t [$/] | |

| Investment cost of VPL in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of existing dispatchable generation at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of candidate dispatchable generation at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of upward flexibility at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of downward flexibility at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of demand response upward flexibility at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of demand response downward flexibility at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of storage h in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of P2P active power contracted at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of P2P active generation contracted at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of load curtailment at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of Non-Dispatchable generation curtailment at node b in time period t [$/] | |

| Variable cost of congestion in time period t [$/] | |

| Probability of Scenario w | |

| Probability of Scenario w from data | |

| Active power of Demand response, bus b, time period t, demand stage s [] | |

| Reactive power of Demand response, bus b, time period t, demand stage s [] | |

| Demand response available flexibility band, bus b, time period t, demand stage s [] | |

| Active power of Net Demand, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power of Net Demand, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of Candidate Non-Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power of Candidate Non-Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of VPP contracted in the P2P market, vpp , bus b, time period t [] | |

| Reactive power of VPP contracted in the P2P market, vpp , bus b, time period t [] | |

| Active power available as downward flexibility at bus b, time period t [] | |

| Active power available as upward flexibility at bus b, time period t [] | |

| Energy capacity of Battery storage h, time period t [] | |

| Maximum power of Battery storage h [] | |

| Maximum active power of Existing Dispatchable generation units, bus b [] | |

| Maximum reactive power of Existing Dispatchable generation units, bus b [] | |

| Maximum Active power of VPP Dispatchable generation, vpp [] | |

| Maximum Reactive power of VPP Dispatchable generation, vpp [] | |

| Maximum Active power of VPP Dispatchable generation, vpp [] |

| Maximum Reactive power of VPP Dispatchable generation, vpp [] | |

| Maximum Active power of Candidate Dispatchable generation, bus b [] | |

| Maximum Reactive power of Candidate Dispatchable generation, bus b [] | |

| Maximum Active power of Upward flexibility, bus b [] | |

| Maximum Active power of Downward flexibility, bus b [] | |

| Reference bar for voltage angle | |

| M | Large power value [p.u.] |

1.4. Decision Variables

| Active power flow of line l, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Signed Active power flow of origin side of line l, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Signed Active power flow of destination side of line l, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power flow of line l, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of VPP demanded from reserve market, vpp , bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power of VPP demanded from reserve market, vpp , bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of VPP Dispatchable generation, vpp , bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power of VPP Dispatchable generation, vpp , bus b, time period t, demand stage, scenario w s [] | |

| Active power of Existing Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power of Existing Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of Candidate Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power of Candidate Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of existing Non-Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Reactive power of existing Non-Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of VPP Non-Dispatchable generation, vpp , bus b, time period t, demand stage s [] | |

| Reactive power of VPP Non-Dispatchable generation, vpp , bus b, time period t, demand stage s [] | |

| Active power of Curtailed Non-Dispatchable generation units, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of Upward flexibility, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of Downward flexibility, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of procured demand response upward flexibility, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of procured demand response downward flexibility, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Active power of Curtailed demand, bus b, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Storage Active power discharge of storage h, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

| Storage Active power charge of storage h, time period t, demand stage s, scenario w [] | |

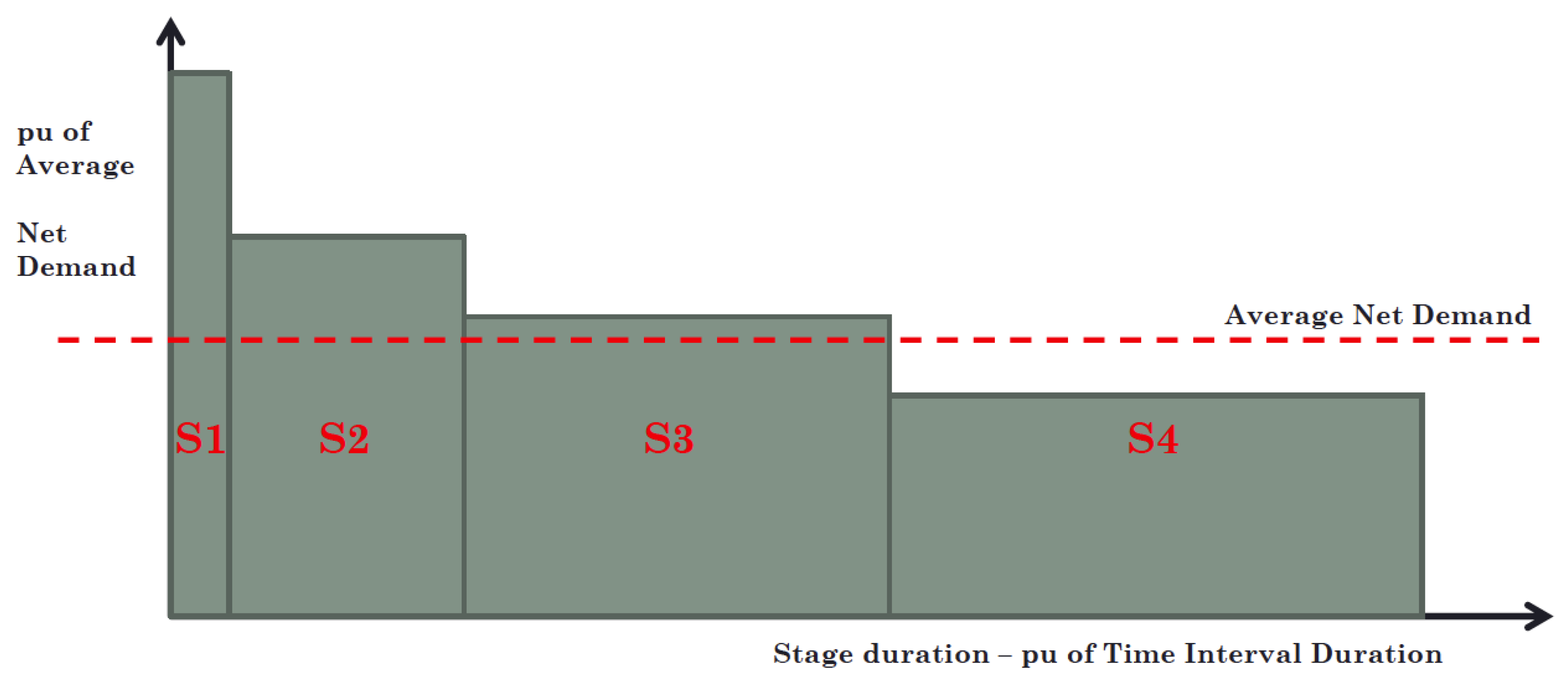

| Time duration of demand stage s [pu] | |

| Voltage (p.u.) at bus b at time t, demand stage s, scenario w | |

| Voltage (p.u.) at bus b at time t, demand stage s, scenario w | |

| Voltage phase angle between nodes i and j at time t, demand stage s, scenario w | |

| State-of-charge (), storage h, at time t, demand stage s, scenario w | |

| Energy available at storage device h in time period t, scenario w [] | |

| Admittance of line l - Real part | |

| Admittance of line l - Imaginary part | |

| Binary variable indicating if downward flexibility is considered at bus b, during demand stage s [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating if upward flexibility is considered at bus b, during demand stage s [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the presence of a circuit c, in corridor l, time period t [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the presence of storage h, time period t [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the presence of VPL l, time period t [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the presence of candidate dispatchable generation , bus b, time period t [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the presence of candidate Non-Dispatchable generation , bus b, time period t [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the charge/discharge status of Battery storage unit h, time period t, stage s [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the flow status of VPL line l from side, time period t, stage s [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the flow status of VPL line l to side, time period t, stage s [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the charge/discharge status of VPL Battery storage unit 1 of line l, time period t, stage s [0,1] | |

| Binary variable indicating the charge/discharge status of VPL Battery storage unit 2 of line l, time period t, stage s [0,1] |

1.5. Vector Notation

| Set of network variables: [, , , ] . | |

| Set of network variables: [ , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ] . |

2. Introduction

2.1. Background

2.2. Literature Review

2.3. Contributions

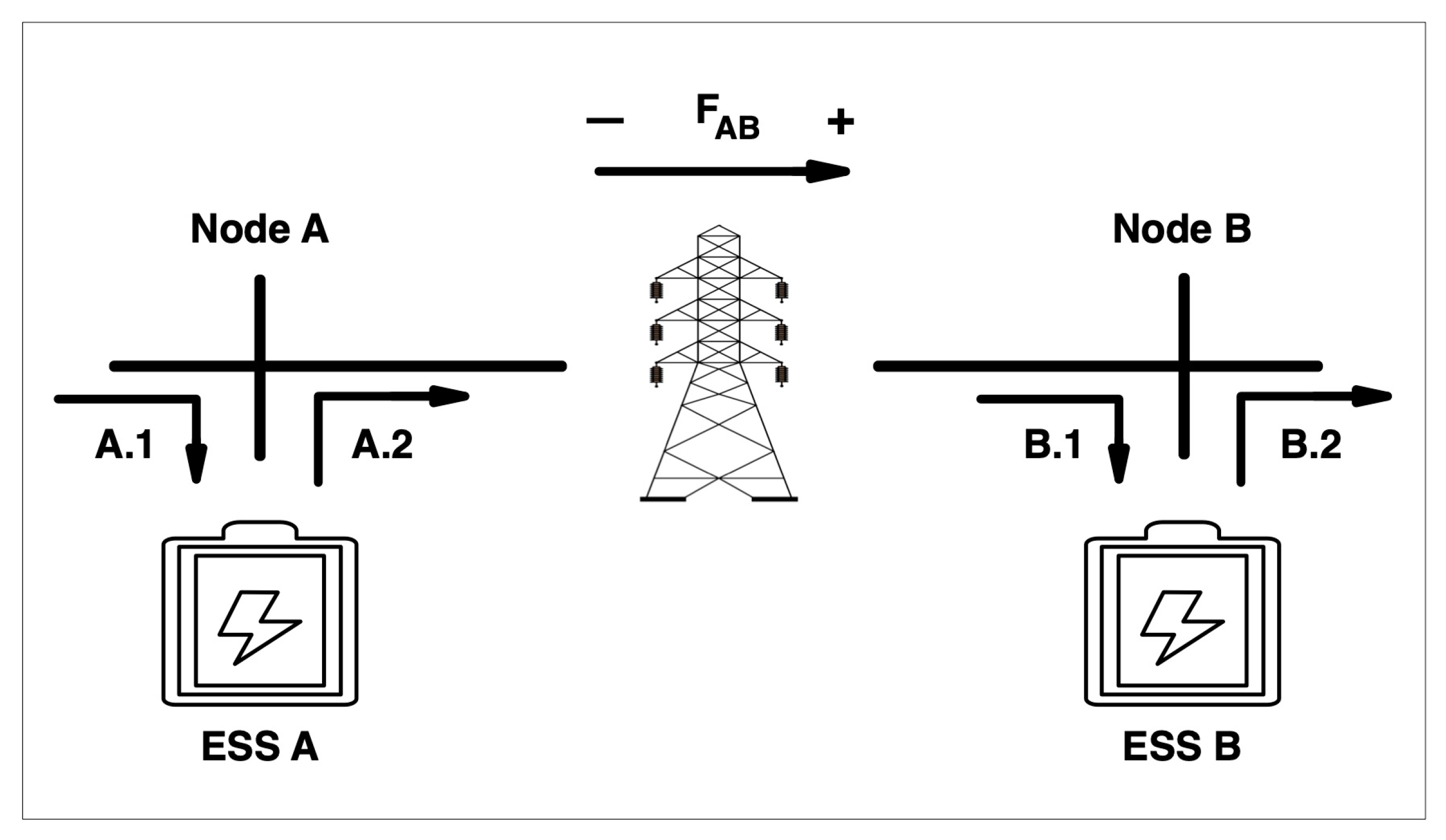

- Battery Energy storage modeling for implementation of Virtual Power Lines, in Generation and Transmission Expansion Planning;

- Modeling of Virtual Power Plants providing aggregated energy and power capacity to transmission nodes;

- Modeling of the Distributed Energy Resources services at the TSO-DSO interconnection as demand response flexibility, providing energy and capacity reserve to transmission system;

- Implementation of a net demand model associated with load duration curve stages to deal with the use of variable renewable energy.

3. Problem Formulation - Deterministic Model

3.1. Net Demand Model

3.2. Flexibility

3.3. Virtual Power Lines

3.4. Virtual Power Plants

3.5. Objective Function

3.6. Power Balance Constraints

3.7. Demand Response Constraints

3.8. Reference Bar and Voltage Constraints

3.9. Transmission Line Circuits Constraints

3.10. Transmission Line Circuits Constraints AC Linearized

3.11. Transmission Line Circuits Constraints AC - Second-Order Cone Constraint

3.12. Energy Storage System Constraints

3.13. Virtual Power Line Constraints

3.14. Flexibility Constraints

3.15. Virtual Power Plants Constraints

3.16. Power Limits Constraints

4. Problem Formulation - Modeling Uncertainties

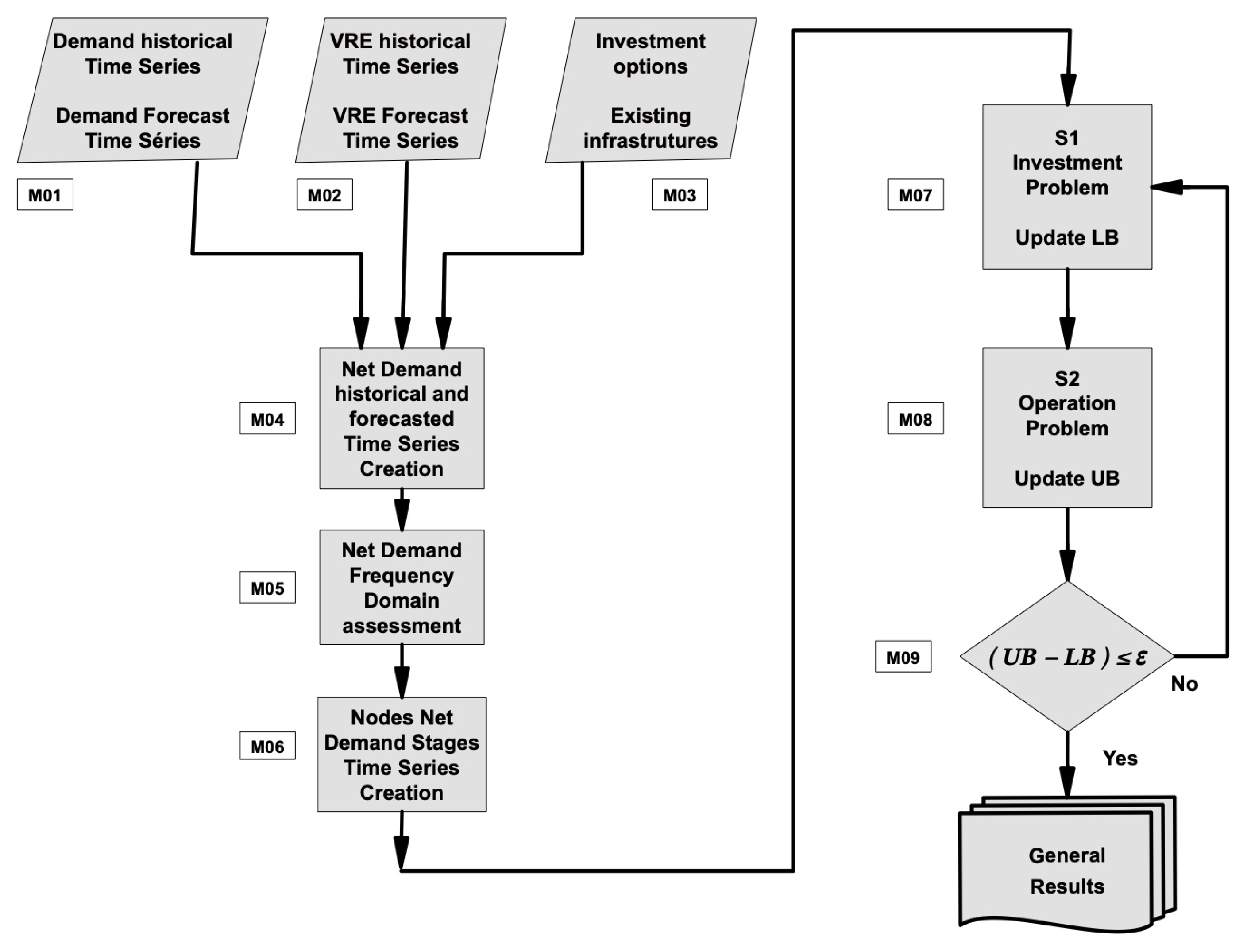

5. Solution Procedure

5.1. Deterministic Procedure

- Set , , k=0 and

-

Solve the following Master Problem:s.t.Solution:

- Update

- Solve the following Slave Problem:s.t.

- Update [ ]

- If return and finish

- Create variables

- Add the following constraints to Master Problem:

- Update k = k + 1 and Go to Step 2

5.2. Procedure Considering Uncertainties

5.2.1. Ambiguity Set

5.2.2. Duality-Free Approach

6. Case Studies

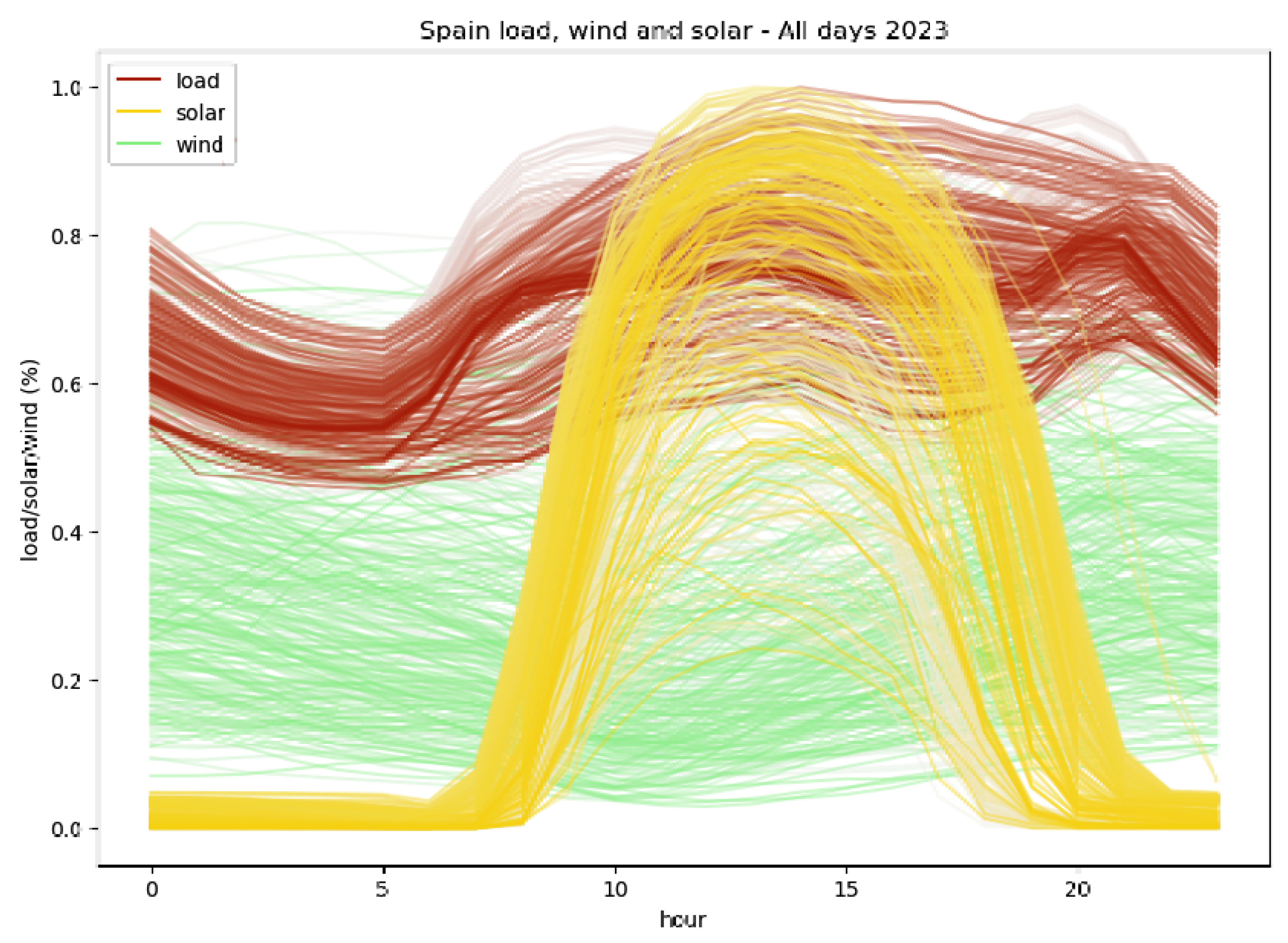

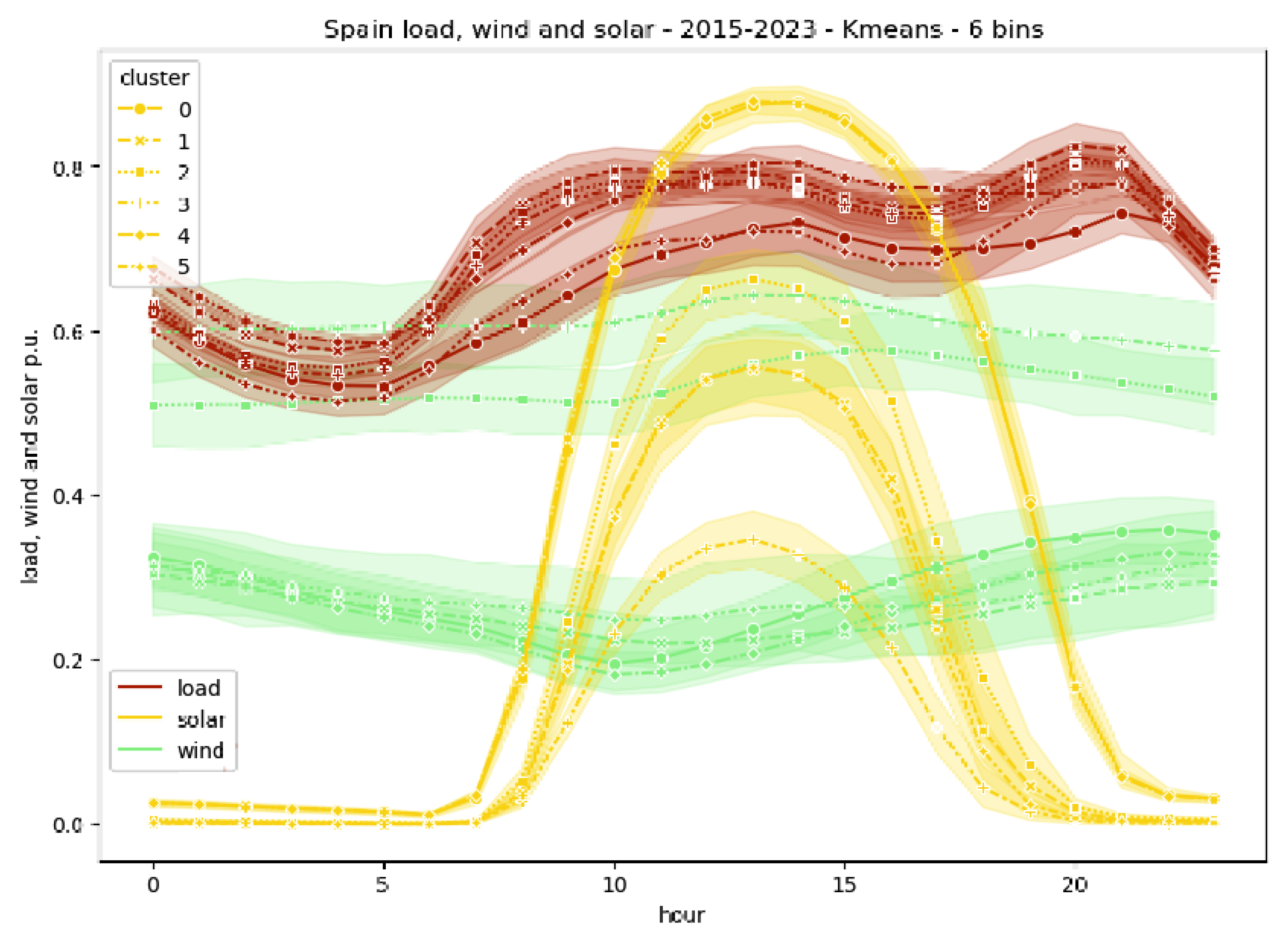

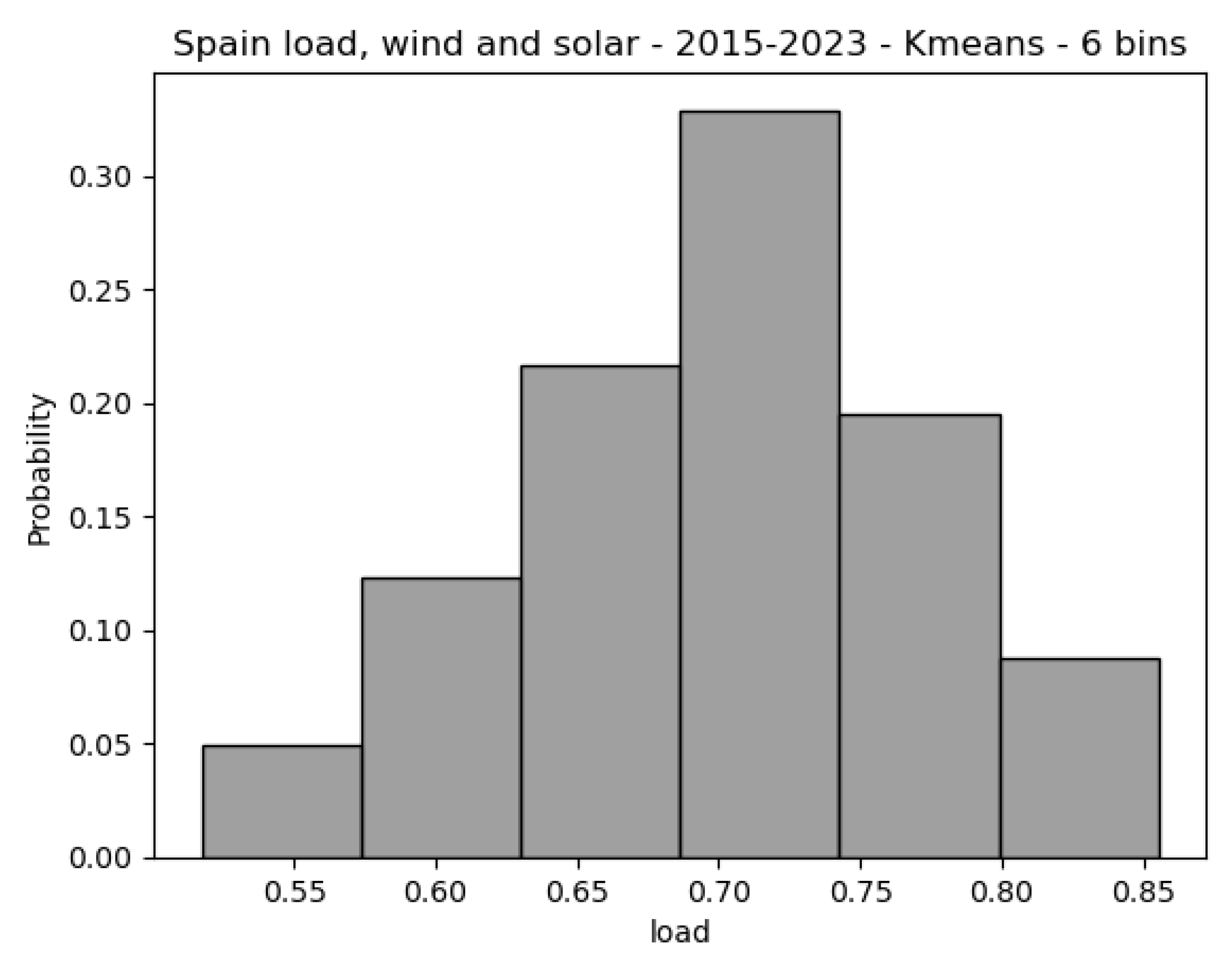

6.1. Cluster of Data Bins

6.2. Garver 6-Node Network

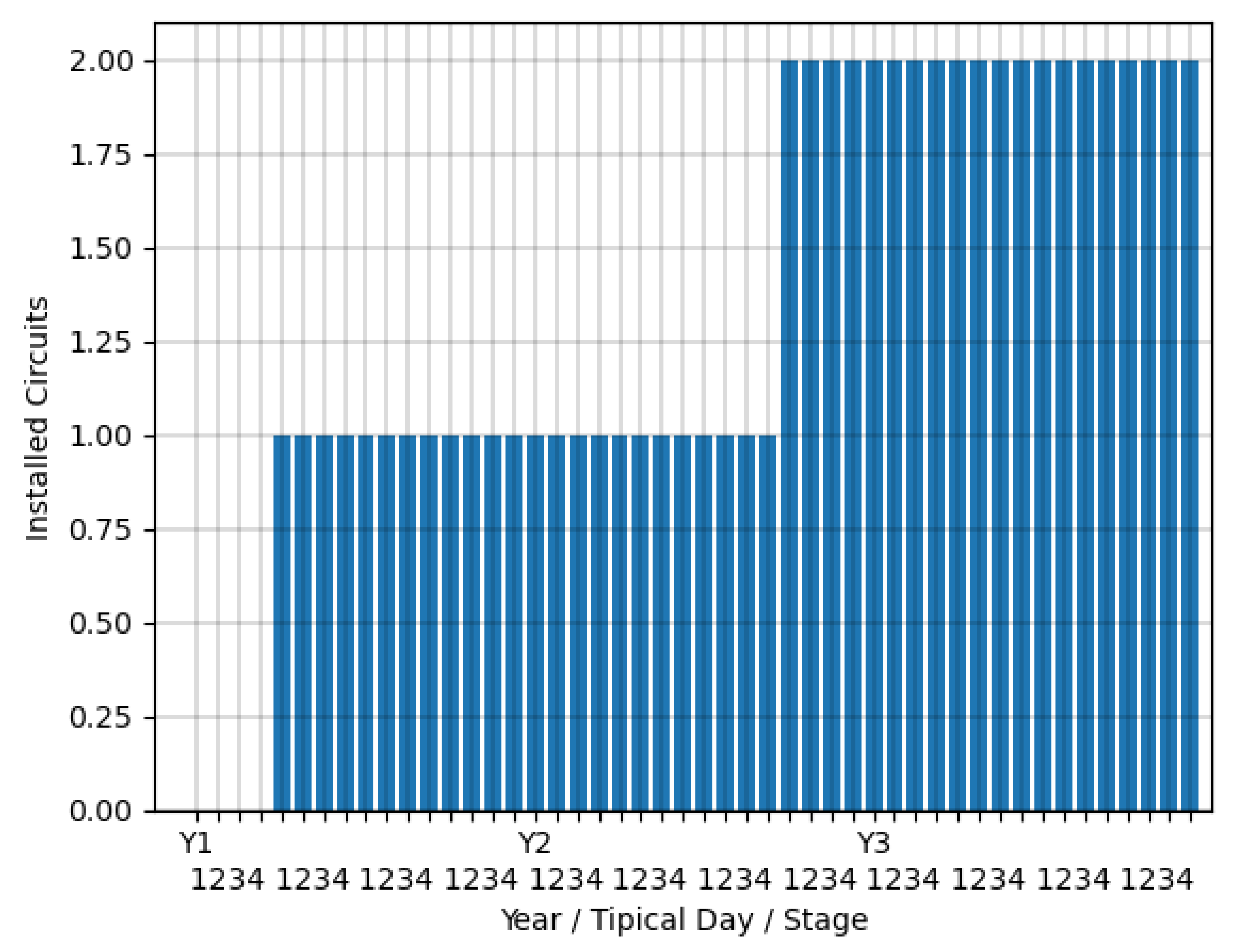

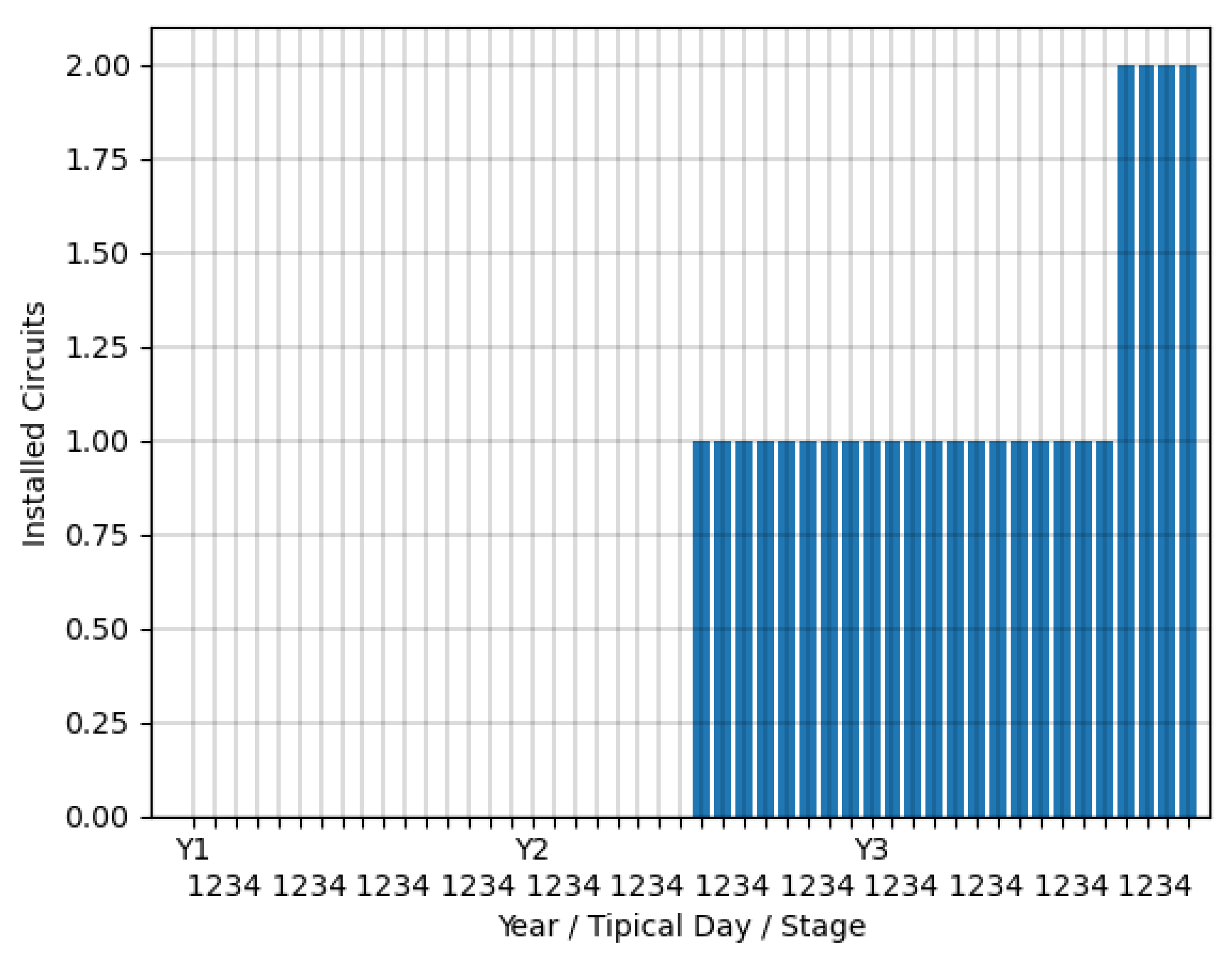

6.2.1. Garver 6-Node Network - Scenario S1.1

6.2.2. Garver 6-Node Network - Scenario S1.2

6.2.3. Garver 6-Node Network - Scenario S1.3

6.3. IEEE RTS-GMLC

6.3.1. IEEE RTS-GMLC - Scenario S2.1

6.3.2. IEEE RTS-GMLC - Scenario S2.2

6.3.3. IEEE RTS-GMLC - Scenario S2.3

6.3.4. IEEE RTS-GMLC - Scenario S2.4

7. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matevosyan, J.; Huang, S.H.; Du, P.; Mago, N.; Guiyab, R. Operational Security: The Case of Texas. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 2021, 19, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, E.; Ho, J.L.; Hobbs, B.F.; Johnson, R.M.; McCalley, J.D. What are the Benefits of Co-Optimizing Transmission and Generation Investment? Eastern Interconnection Case Study. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 32, 4265–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, G.; Cruz, R.D.; Areiza, J.M.; Villegas, A. Classification of publications and models on transmission expansion planning. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2003, 18, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, R.; Hooshmand, R.; Khodabakhshian, A. Comprehensive review of generation and transmission expansion planning. IET Generation, Transmission Distribution 2013, 7, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, M.; Sabillon Antunez, C.; Ajalli, M.; Romero, R. Transmission Expansion Planning: Literature Review and Classification. IEEE Systems Journal 2019, 13, 3129–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Meligy, M.A.; Sharaf, M.; Soliman, A.T. A coordinated scheme for transmission and distribution expansion planning: A Tri-level approach. Electric Power Systems Research 2021, 196, 107274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, H.; Hosseini, S.H.; Zareipour, H. A robust optimization method for co-planning of transmission systems and merchant distributed energy resources. International Journal of Electrical Power Energy Systems 2020, 118, 105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushamah, H.A.S.; Haghifam, M.; Bolandi, T.G. A novel approach for distributed generation expansion planning considering its added value compared with centralized generation expansion. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2021, 25, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, H.; Hosseini, S.H.; Zareipour, H. Resiliency-Oriented Planning of Transmission Systems and Distributed Energy Resources. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2021, 36, 4114–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Cheng, H.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Data-driven distributionally robust transmission expansion planning considering contingency-constrained generation reserve optimization. International Journal of Electrical Power Energy Systems 2021, 131, 106973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanapriya, T.; Manikandan, T.R. Congestion management of deregulated electricity market using locational marginal pricing. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Research, 2014, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Benders, J.F. Partitioning Procedures for Solving Mixed-variables Programming Problems. Numer. Math. 1962, 4, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejo, A.J.; Mínguez, R.; Castillo, E.; García-Bertrand, R. Decomposition Techniques in Mathematical Programming, 1st ed.; Springer, 2006.

- Romero, R.; Monticelli, A. A hierarchical decomposition approach for transmission network expansion planning. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 1994, 9, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, S.L. O Planejamento da Expansão dos Sistemas Elétricos no Contexto de um Ambiente Competitivo. PhD thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2000.

- Jabr, R.A. Robust Transmission Network Expansion Planning With Uncertain Renewable Generation and Loads. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2013, 28, 4558–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Wang, Z. Robust Optimization for Transmission Expansion Planning: Minimax Cost vs. Minimax Regret. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2014, 29, 3069–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C.; Conejo, A. Robust transmission expansion planning. European Journal of Operational Research 2015, 242, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, T.; Caijuan, Q.; Liang, Z.; Pengjiang, G.; Jianfeng, G.; Panlong, J. A comprehensive flexibility optimization strategy on power system with high-percentage renewable energy. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy (ICPRE), 2017, pp. 553–558. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, E.F.; Olmos, L.; Ramos, A.; Antoniadou-Plytaria, K.; Steen, D.; Tuan, L.A. Values and impacts of incorporating local flexibility services in transmission expansion planning. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 212, 108480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wu, J.; Peng, Q.; Zhao, H.; Huang, X. Optimal Transmission Expansion Planning Considering Demand Response Characteristics of Load Duration Curve. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), 2022, pp. 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACPEE53904.2022.9783835. [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, M.; Korpås, M.; Farahmand, H.; Graabak, I.; Härtel, P. Introducing system flexibility to a multinational transmission expansion planning model. In Proceedings of the 2016 Power Systems Computation Conference (PSCC), 2016, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Arango, D.A.; Morales-España, G.; Wogrin, S.; Centeno, E. Power-Based Generation Expansion Planning for Flexibility Requirements. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 35, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, S.; Amjady, N.; Conejo, A.J. A Multistage Robust Transmission Expansion Planning Model Based on Mixed Binary Linear Decision Rules—Part I. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 5341–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Heydt, G.T.; Vittal, V.; Quintero, J. An Improved Network Model for Transmission Expansion Planning Considering Reactive Power and Network Losses. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2013, 28, 3471–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bynum, M.; Castillo, A.; Watson, J.P.; Laird, C.D. A multitree approach for global solution of ACOPF problems using piecewise outer approximations. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2018, 114, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, M.; Castillo, A.; Watson, J.P.; Laird, C.D. Tightening McCormick Relaxations Toward Global Solution of the ACOPF Problem. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 34, 814–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaddar, B.; Jabr, R.A. Power transmission network expansion planning: A semidefinite programming branch-and-bound approach. European Journal of Operational Research 2019, 274, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrtash, M.; Cao, Y. A New Global Solver for Transmission Expansion Planning With AC Network Model. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2022, 37, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrtash, M.; Hobbs, B.F.; Mahroo, R.; Cao, Y. Does Choice of Power Flow Representation Matter in Transmission Expansion Optimization? A Quantitative Comparison for a Large-Scale Test System. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2024, 60, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmintier, B.S.; Webster, M.D. Impact of Operational Flexibility on Electricity Generation Planning With Renewable and Carbon Targets. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2016, 7, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lv, J.; McElroy, M.B.; Han, X.; Nielsen, C.P.; Wen, J. Power System Capacity Expansion Under Higher Penetration of Renewables Considering Flexibility Constraints and Low Carbon Policies. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 6240–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendelborg, M.A.; Backe, S.; del Granado, P.C.; Seifert, P.E. Consequences of Uncertainty from Intraday Operations to a Capacity Expansion Model of the European Power System. In Proceedings of the 2023 19th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), 2023, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Alvarez, E.F.; Lumbreras, S. OpenTEPES: Open-source Transmission and Generation Expansion Planning. SoftwareX 2022, 18, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Conejo, A.J.; Carrión, M. Toward Fully Renewable Electric Energy Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2015, 30, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baringo, L.; Baringo, A. A Stochastic Adaptive Robust Optimization Approach for the Generation and Transmission Expansion Planning. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Pozo, D.; Street, A.; Sauma, E. Reliable Renewable Generation and Transmission Expansion Planning: Co-Optimizing System’s Resources for Meeting Renewable Targets. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 32, 3246–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Mavalizadeh, H.; Ghadimi, A.A.; Miveh, M.R.; Ahmadi, A. Dynamic robust generation–transmission expansion planning in the presence of wind farms under long- and short-term uncertainties. IET Generation, Transmission Distribution 2020, 14, 5418–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Pozo, D.; Street, A.; Sauma, E.; Strbac, G. Climate-aware generation and transmission expansion planning: A three-stage robust optimization approach. European Journal of Operational Research 2021, 295, 1099–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backe, S.; Ahang, M.; Tomasgard, A. Stable stochastic capacity expansion with variable renewables: Comparing moment matching and stratified scenario generation sampling. Applied Energy 2021, 302, 117538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curty, M.G.; Borges, C.L.; Saboia, C.H.; Lisboa, M.L.; Berizzi, A. A soft-linking approach to include hourly scheduling of intermittent resources into hydrothermal generation expansion planning. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 188, 113838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toolabi Moghadam, A.; Bahramian, B.; Shahbaazy, F.; Paeizi, A.; Senjyu, T. Stochastic Flexible Power System Expansion Planning, Based on the Demand Response Considering Consumption and Generation Uncertainties. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bertrand, R.; Mínguez, R. Dynamic Robust Transmission Expansion Planning. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 32, 2618–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, C.; Mínguez, R.; García-Bertrand, R.; Arroyo, J.M. Robust Transmission Network Expansion Planning Under Correlated Uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 34, 2071–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Kang, C. Robust Transmission Expansion Planning Based on Adaptive Uncertainty Set Optimization Under High-Penetration Wind Power Generation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2021, 36, 2798–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Lin, Z.; Kang, C. Probability-driven transmission expansion planning with high-penetration renewable power generation: A case study in northwestern China. Applied Energy 2019, 255, 113610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, H.; Liang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, J. Robust transmission network expansion planning based on a data-driven uncertainty set considering spatio-temporal correlation. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2023, 33, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cerezo, A.; Baringo, L.; Garcia-Bertrand, R. Dynamic Robust Transmission Network Expansion Planning in Renewable Dominated Power Systems Considering Inter-Temporal and Non-Convex Operational Constraints. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies (SEST), 2022, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cerezo, A.; Baringo, L.; Garcia-Bertrand, R. Expansion planning of the transmission network with high penetration of renewable generation: A multi-year two-stage adaptive robust optimization approach. Applied Energy 2023, 349, 121653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Conejo, A.J. Coordinated Investment in Transmission and Storage Systems Representing Long- and Short-Term Uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 7143–7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verastegui, F.; Lorca, A.; Olivares, D.E.; Negrete-Pincetic, M.; Gazmuri, P. An Adaptive Robust Optimization Model for Power Systems Planning With Operational Uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 34, 4606–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Ye, H.; Zhang, X.; Mei, S.; Chang, N. Robust Coordinated Transmission and Generation Expansion Planning Considering Ramping Requirements and Construction Periods. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, H.; Liang, Z.; Zhu, Y. A Flexibility-oriented robust transmission expansion planning approach under high renewable energy resource penetration. Applied Energy 2023, 351, 121786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, F.; Nijhuis, M.; Nguyen, P.H.; Cobben, J.F.G. Variance-Based Global Sensitivity Analysis for Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 1670–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, N.; Neyestani, N.; Soares, F.; Iria, J.; Lopes, M.; Antunes, C.H.; Pinto, D.; Jorge, H. Bottom-up approach to compute der flexibility in the transmission-distribution networks boundary. In Proceedings of the Mediterranean Conference on Power Generation, Transmission, Distribution and Energy Conversion (MEDPOWER 2018), 2018, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Byrne, R.H. Evaluation of Energy Storage Providing Virtual Transmission Capacity. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), 2021, pp. 01–05. [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Virtual Power Lines - Innovation Landscape Brief. IRENA International Renewable Energy 2020.

- Baringo, A.; Baringo, L.; Arroyo, J.M. Holistic planning of a virtual power plant with a nonconvex operational model: A risk-constrained stochastic approach. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2021, 132, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; Machado, G.; Rego, E.; Esteves, H.; Carvalho, A. Manual de Utilização do Modelo de Otimização da Expansão da Oferta de Energia Elétrica – Modelo PLANEL. https://www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/PublicacoesArquivos/publicacao-227/topico-563/NT_PR_004.22_Manual%20PLANEL.pdf, 2022.

- Ding, T.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X.; Huang, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; Blaabjerg, F. Duality-Free Decomposition Based Data-Driven Stochastic Security-Constrained Unit Commitment. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2019, 10, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, C.; Gong, K.; Si, R.; Shao, H.; Liu, W. Data-driven distributionally robust economic dispatch for distribution network with multiple microgrids. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2020, 14, 5712–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Zhao, L. Solving two-stage robust optimization problems using a column-and-constraint generation method. Operations Research Letters 2013, 41, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erseghe, T. Distributed Optimal Power Flow Using ADMM. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2014, 29, 2370–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, R.S.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Fan, L. ADMM for nonconvex AC optimal power flow. In Proceedings of the 2017 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Conejo, A.J. Robust Transmission Expansion Planning Representing Long- and Short-Term Uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2018, 33, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zeng, B. Robust unit commitment problem with demand response and wind energy. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, 2012, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Mahroo, R.; Kargarian, A.; Mehrtash, M.; Conejo, A.J. Robust Dynamic TEP With an Security Criterion: A Computationally Efficient Model. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2023, 38, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Guan, Y. Data-Driven Stochastic Unit Commitment for Integrating Wind Generation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2016, 31, 2587–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C. Data-Driven Stochastic Transmission Expansion Planning. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 32, 3461–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENTSOE. Electricity generation, transportation and consumption data and information for the pan-European market. https://transparency.entsoe.eu/dashboard/show, 2024.

- Ferreira, F. UFPR - Data Repository. https://github.com/Falferreira/Phd_Files.git, 2022.

- Barrows, C.; Bloom, A.; Ehlen, A.; Ikäheimo, J.; Jorgenson, J.; Krishnamurthy, D.; Lau, J.; McBennett, B.; O’Connell, M.; Preston, E.; et al. The IEEE Reliability Test System: A Proposed 2019 Update. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 35, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerigk, M.; Khosravi, M. Optimal scenario reduction for one- and two-stage robust optimization with discrete uncertainty in the objective. European Journal of Operational Research 2023, 310, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, M.J. Planejamento da Expansão de Sistemas de Transmissão Usando os Modelos CC – CA e Técnicas de Programação Não – Linear. PhD thesis, University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, 2006.

- Ayres, D.; Zamora, L. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2023; IRENA, 2024; p. 211.

- Zobaa, A.F.; Ribeiro, P.F.; Aleem, S.H.A.; Afifi, S.N. Energy storage at different voltage levels: technology, integration, and market aspects; Vol. 111, Energy Engineering, 2018.

| Ref1 | GEP2 | TEP3 | UC4 | VPP5 | VPL6 | Flx7 | Gen Flx8 | DR E Flx9 | DR C Flx10 | T Scale11 | VRE12 | Cong13 | AC14 | DC15 | Sen16 | Static17 | Dynamic18 |

| [23] | |||||||||||||||||

| [24] | |||||||||||||||||

| [25] | |||||||||||||||||

| [26] | |||||||||||||||||

| [27] | |||||||||||||||||

| [28] | |||||||||||||||||

| [29] | |||||||||||||||||

| [30] | |||||||||||||||||

| [31] | |||||||||||||||||

| [32] | |||||||||||||||||

| [33] | |||||||||||||||||

| [34] | |||||||||||||||||

| [35] | |||||||||||||||||

| [36] | |||||||||||||||||

| [37] | |||||||||||||||||

| [7] | |||||||||||||||||

| [10] | |||||||||||||||||

| [9] | |||||||||||||||||

| [8] | |||||||||||||||||

| [38] | |||||||||||||||||

| [39] | |||||||||||||||||

| [40] | |||||||||||||||||

| [6] | |||||||||||||||||

| [41] | |||||||||||||||||

| [29] | |||||||||||||||||

| [42] | |||||||||||||||||

| [43] | |||||||||||||||||

| [44] | |||||||||||||||||

| [45] | |||||||||||||||||

| [46] | |||||||||||||||||

| [47] | |||||||||||||||||

| [48] | |||||||||||||||||

| [49] | |||||||||||||||||

| [50] | |||||||||||||||||

| [51] | |||||||||||||||||

| [52] | |||||||||||||||||

| [53] | |||||||||||||||||

| [54] | |||||||||||||||||

| Proposed model |

| Demand side Fij (+) | Supply side Fij (-) | |

| Hi grid usage | Discharge | Charge |

| Low grid usage | Charge | Discharge |

| Scenario S1.1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Circuits | VPL | Disp Gen [GW] | Ndisp Gen [GW] | Dem Response [GW] | DSO Flex [GW] | Cost [M$] |

| 2-6 | - | - | - | - | - | 30 |

| 2-6 | - | - | - | - | - | 30 |

| 3-5 | - | - | - | - | - | 20 |

| 4-6 | - | - | - | - | - | 30 |

| - | - | 0.68 | - | - | - | 28.2 |

| Total | 138.2 | |||||

| Scenario S1.2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Circuits | VPL | Disp Gen [GW] | Ndisp Gen [GW] | Dem Response [GW] | DSO Flex [GW] | Cost [M$] |

| 2-6 | - | - | - | - | - | 30 |

| - | 2-6 | - | - | - | - | 27.5 |

| 3-5 | - | - | - | - | - | 20 |

| - | 4-6 | - | - | - | - | 27.5 |

| - | - | 0.68 | - | - | - | 28.2 |

| Total | 133.2 | |||||

| Scenario S1.3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Circuits | VPL | Disp Gen [GW] | Ndisp Gen [GW] | Dem Response [GW] | DSO Flex [GW] | Cost [M$] |

| 2-6 | - | - | - | - | - | 30 |

| - | 2-6 | - | - | - | - | 18.75 |

| - | 3-5 | - | - | - | - | 18.75 |

| - | 4-6 | - | - | - | - | 18.75 |

| - | - | 0.68 | - | - | - | 28.2 |

| Total | 114.45 | |||||

| Scenario S2.1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Circuits | VPL | Disp Gen [GW] | Ndisp Gen [GW] | Dem Response [GW] | DSO Flex [GW] | Cost [M$] |

| 15-24 | - | - | - | - | - | 99.8 |

| 55-56 | - | - | - | - | - | 39.3 |

| 59-61 | - | - | - | - | - | 24.9 |

| 58-60 | - | - | - | - | - | 14.7 |

| - | - | 8.2 | - | - | - | 348 |

| Total | 526.7 | |||||

| Scenario S2.2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Circuits | VPL | Disp Gen [GW] | Ndisp Gen [GW] | Dem Response [GW] | DSO Flex [GW] | Cost [M$] |

| - | 15-24 | - | - | - | - | 37.5 |

| - | 55-56 | - | - | - | - | 37.5 |

| 59-61 | - | - | - | - | - | 24.9 |

| 58-60 | - | - | - | - | - | 14.7 |

| - | - | 8.2 | - | - | - | 348 |

| Total | 462.6 | |||||

| Scenario S2.3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Circuits | VPL | Disp Gen [GW] | Ndisp Gen [GW] | Dem Response [GW] | DSO Flex [GW] | Cost [M$] |

| - | 15-24 | - | - | - | - | 22.5 |

| - | 55-56 | - | - | - | - | 22.5 |

| - | 59-61 | - | - | - | - | 22.5 |

| 58-60 | - | - | - | - | - | 14.7 |

| - | - | 8.2 | - | - | - | 338 |

| Total | 420.2 | |||||

| Scenario S2.4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Circuits | VPL | Disp Gen [GW] | Ndisp Gen [GW] | Dem Response [GW] | DSO Flex [GW] | Cost [M$] |

| - | 15-24 | - | - | - | - | 37.5 |

| - | 55-56 | - | - | - | - | 37.5 |

| 59-61 | - | - | - | - | - | 24.9 |

| 58-60 | - | - | - | - | - | 14.7 |

| - | - | 5.05 | 1.1 | 2.05 | 0.615 | 282.76 |

| Total | 397.36 | |||||

| Scenario | Average Line Usage [p.u.] | Line Losses [p.u.] | LMP Average [$] |

|---|---|---|---|

| S2.1 | 0.968 | 450.3 | 1001.3 |

| S2.2 | 1.167 | 447.4 | 981.1 |

| S2.3 | 1.185 | 443.0 | 731.5 |

| S2.4 | 1.196 | 440.5 | 66.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).