1. Introduction

Since the first observation of a carbon nanotube (CNT) of 50 nanometers diameter in 1952 [

1], many scientific studies of synthesis, characterization, and detailed investigation on mechanical, thermal, electronic, optical, and plasmonic properties have been done in carbon nanotubes. In 1975, Oberlin et al. observed a multi-walled CNT (MWCNT) as a hollow tube of rolled graphite in carbon fiber synthesis utilizing the chemical vapor deposition method decomposing benzene and hydrogen at high temperatures in the presence of a transition metal as a catalyst [

2]. Dresselhaus et al. contributed to the theoretical investigation of carbon-based materials, namely, carbon whiskers and graphite intercalation compounds, in the late 1970s. [

3,

4]. The first evidence of CNT production as fiber in carbon anode in arc discharge technique was presented at the Biennial Conference of Carbon in 1978 [

5]. MWCNTs were perceived as rolled graphene layers in a cylindrical geometry after Nesterenko et al.’s work on thermoanalytical disproportionation of carbon monoxide to characterize carbon nanoparticles [

6]. Howard Tennent received a US patent in producing cylindrical discrete carbon fibrils of diameter in the range of 3.5 to 70 nm [

7]. The experimental discovery of MWCNTs by S. Iijima in arc-burned graphite rods and their imaging through a high-resolution electron beam technique of transmission electron microscopy is considered a turning point of CNT research [

8]. Within two years after such discovery, it was observed that some single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) show exceptional conducting behavior [

9,

10]. Since then, CNTs have received significant attention among researchers in this field because of their high tensile strength (∼ order of

Pa for SWCNTs [

11]), higher electrical and thermal conductivities, opto-plasmonic properties, and chirality-dependent metallicity.

The plasmon spectrum of SWCNTs is rich in plasmon resonance peaks. Semiconducting SWCNTs have plasmon modes in the visible and ultraviolet (UV) ranges of a few hundred to thousands of terahertz (THz), while metallic SWCNTs have plasmon modes and comparatively intense plasmon peaks in the low-frequency range of only a few THz besides the other plasmon modes in the visible and UV ranges, like semiconducting SWCNTs [

12,

13]. For a thin film of CNTs, the film’s plasmonic behavior on it’s interaction with light results due to the collective excitons, which can be tuned by changing the radius, sparseness of CNTs, thickness of dielectric medium in which CNTs are immersed, and chirality of the SWCNTs [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Note that the permitivity of the host medium is comparatively larger than the permittivities of substrate and superstate, and chirality of the CNTs [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Plasmonic interconnect circuits built from CNTs offer a new material platform for nanoscale electronic devices integrated with optoelectronic components as they offer high electrical conductivity, ballistic transportation, resistance to electromigration, and broadband response [

20]. Binding a target molecules to the CNT’s surface, CNTs can be used for gas sensing, chemical sensing, and bio-sensing as plasmonic properties of CNT become sensitive in the presence of target molecules [

21,

22]. SWCNT films’ optical transparency, excellent flexibility, and remarkable potency under mechanical stress make them good candidates for transparent conductive films for liquid crystal display and organic light-emitting diode displays, transparent electrodes in photovoltaic cells, and quantum dots light-emitting diodes [

26,

27]. The films can also be used in optical modulators and optoelectronic sensors. SWCNT films can be integrated into metamaterials for sub-wavelength imaging in super lenses, cloaking devices, beam-steering technologies, and electromagnetic interference shielding for aerospace and telecommunications [

28]. Hybrid plasmonic-CNT structures obtained by incorporating one-dimensional (1D) CNT tubules with other 2D plasmonic materials such as MXenes and graphene are useful for fine-tuning various electrical, optical, thermal, and plasmonic properties as MXenes and graphene provides additional pathways for electron transport and enhances the coupling between MXenes’ or graphene’s localized surface plasmons and the electron-rich CNTs network, amplifying the plasmonic response [

23,

24,

25].

Any SWCNT of chiral indices

can be thought of as being a hollow cylinder prepared by rolling a graphene sheet along the specific chiral vector

given by

, where

and

represent the graphene lattice vectors.

and

serve as translation vectors. A scheme of rolling a graphene sheet to obtain different types of SWCNTs is presented in

Figure 1. The radius and chiral angle of any SWCNT can be calculated as [

29,

30,

31]

and

where

Å is the carbon-to-carbon distance in a graphene sheet. The chiral angle

satisfies

.

equals

for a zigzag SWCNT with chiral indices

and

for an armchair SWCNT with chiral indices

. The chiral angle

satisfies

for chiral SWCNTs. All the armchair SWCNTs are metallic. However, the zigzag SWCNTs are metallic or small band-gap semiconductors based on whether the chiral index

n is divisible by 3 or not, respectively. The chiral SWCNTs, whose chiral indices

n and

m are neither identical nor either one is zero, are quasi-metallic if the chiral indices difference

is divisible by 3 and semi-conductive otherwise. Statistically, 1/3

rd of SWCNTs are metallic, while the remaining 2/3

rd are semiconducting with a small bandgap. Depending on the technological requirement, one can synthesize SWCNTs of specific chirality.

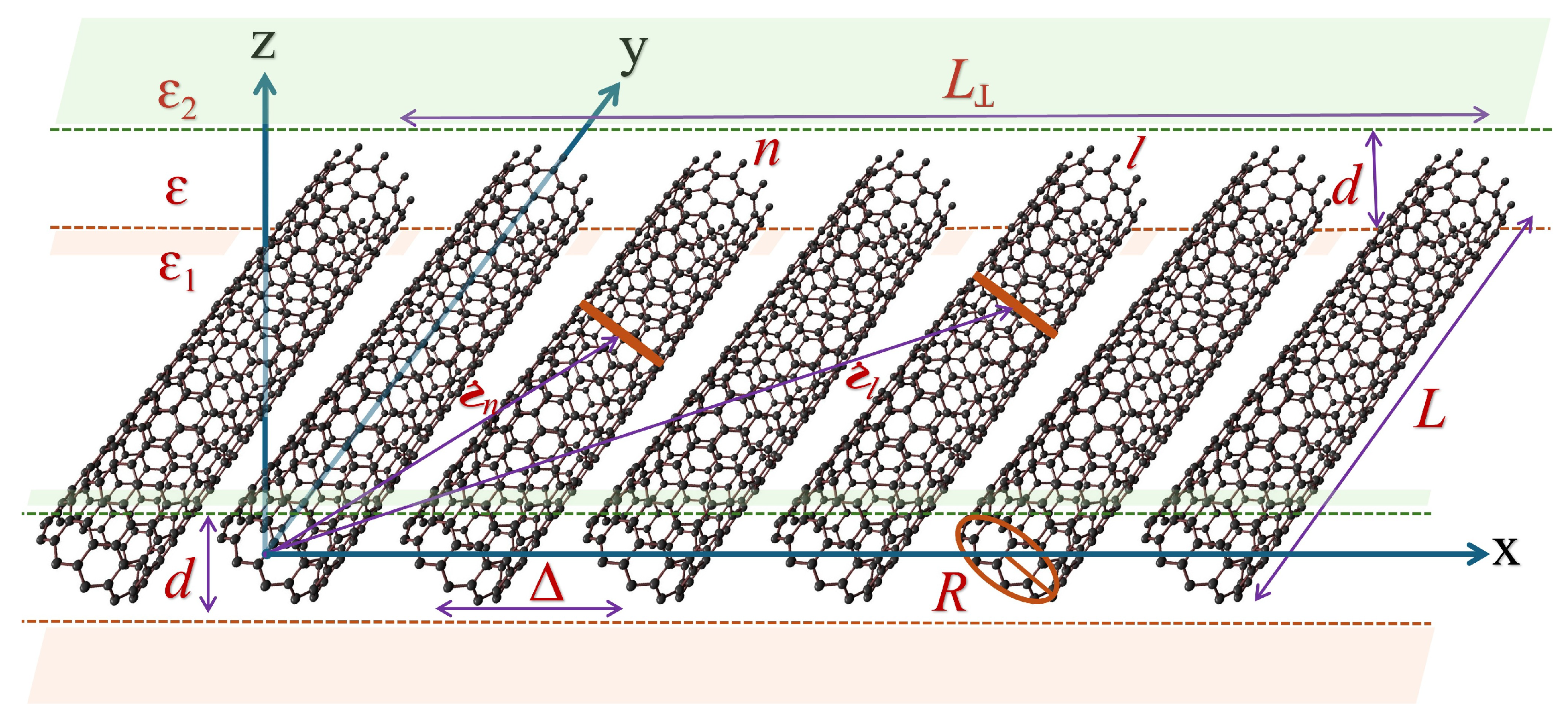

Literature is rich in the study of mechanical, electronic, optical, and plasmonic behavior of a single SWCNTs [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. This paper extends our work to the thin and ultrathin films of homogeneous SWCNTs, which are oriented along the y-axis in periodic alignment. A schematic diagram of the theoretical model considered in this study is presented in

Figure 2. Each SWCNT presented in the figure is plotted using Nanotube Modeler Software [

37,

38], which is a program to generate

-coordinates and plot interactive graphics for capped and uncapped nanotubes and nanocones for chosen chirality, tube length, and bond length. The SWCNT-array is immersed in a dielectric medium of thickness

d and constant effective relative permittivity

. The substrate and superstate have relative permitivities of

and

, which are relatively much smaller in value than

. Each SWCNT has a radius

R and length

L. The center-to-center distance inter-tube distance

satisfies

with the minimum ideal distance being the sum of the radii of the two closest tubes.

determines the disperseness of SWCNTs in the film with larger

signifying highly dispersed SWCNT film.

denotes the SWCNT film width. The SWCNTs have uniform electronic charge distribution throughout the surface of the tube.

Taking rings in

SWCNT at position vector

and

SWCNT at

, the distance between the rings can be expressed as

. For a thin film with a thickness smaller than the distance between rings denoting unit cells of different SWCNTs as shown in

Figure 2 i.e.,

, the electrostatic (Coulomb) interaction between the rings of unit cells becomes so strong that it loses the dependency on its vertical component. As a result, the effective dimensionality of the SWCNT film decreases by one, making it a 2D problem retaining the vertical size, i.e., thickness, as a parameter [

16,

17]. Such a system with a relatively small thickness, better known as trans-dimensional material (TDM), offers an exceptional tool to tune various opto-plasmonic properties that are unattainable from both 3D bulk and/or single-layered 2D counterparts.

To understand and utilize light-matter interactions in SWCNT and its film at the nanoscale, evaluating and analyzing their dielectric response tensors is crucial as dielectric response functions delineate collective oscillations of free electrons, excitons, and plasmons. The dielectric properties dependent surface plasmons and localized surface plasmon resonances occur on the film’s surface, creating strong electromagnetic fields when free electrons resonate with incident photon [

18,

19]. We derive a closed-form of mathematical expressions for the dynamical (as a function of photon frequency) dielectric response functions of the SWCNT array as presented in

Figure 2 using the many-particle Green’s function technique exploiting Matsubara frequency approach as discussed in Ref. [

39].

We organize this paper as follows. We orient ourselves with a mathematical overview for dielectric responses for SWCNTs in Sec.

Section 2. We first evaluate a SWCNT’s dynamic conductivity, which is then used to evaluate its polarizability and dielectric response functions. A comparative study of the dynamical conductivity of two different types of SWCNTs is presented, followed by the dynamical permittivities and dynamical conductivity of a SWCNT used in the SWCNT array. The dielectric response functions of an array of identical SWCNTs are presented in Sec.

Section 3. Therein, we set up the Hamiltonian of the system, determine the interaction Hamiltonian for the SWCNT film, and present the closed-form of expressions for dielectric responses. Taking (11,0) SWCNT film as a reference, we discuss our research findings in Sec.

Section 4. We present conclusions in Sec.

Section 5. We have used Gaussian units throughout this paper unless otherwise stated.

2. Dielectric Responses of an Isolated SWCNT

When light interacts with a valence electron of carbon in a SWCNT, the electron gets excited to the conduction band, leaving a hole behind, thereby creating an electron-hole pair called exciton and inducing an anisotropic polarization. The induced polarization is dominant along the SWCNT axis and negligible in the directions perpendicular to the SWCNT alignment due to the weakening of the response to incident photon along the width of the tube called transverse depolarization effect [

40,

41]. The photon frequency and SWCNT radius-dependent axial polarizability

of an SWCNT can be expressed in terms of its axial surface conductivity

as [

42]

where

is an infinitesimal frequency parameter. The dynamical conductivity of a SWCNT is estimated using the well-known

method of band structure calculations [

41,

43]. The conducting behavior of SWCNTs significantly varies with chirality and divisibility of the difference between chiral indices by 3. For example, (9,0) SWCNT is metallic, while (10,0) SWCNT is a semiconducting one. The exciton-plasmon spectrum for the conductivity of metallic SWCNT significantly differs from the semiconducting one, as shown in

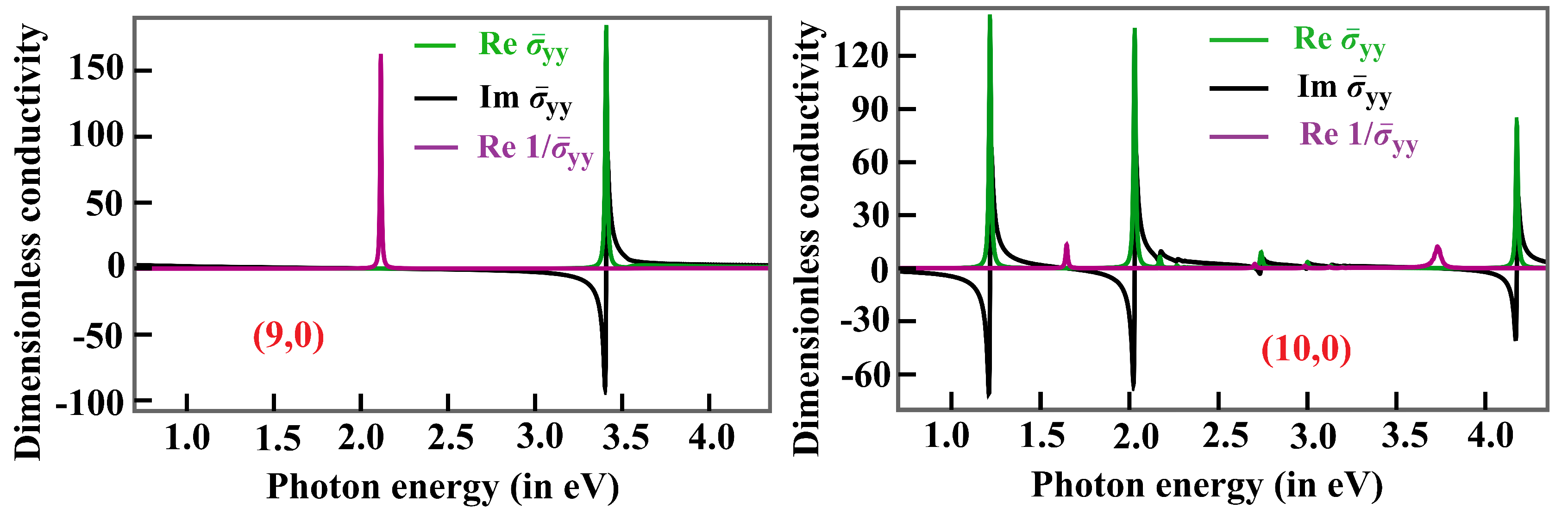

Figure 3.

One may ask how the plasmon spectrum for the conductivity of an isolated SWCNT, measured by

, can have such intense resonance peaks. The quantity

can be expressed as

where

and

denote the real and imaginary parts respectively. At the energy value, in which the real part approaches zero, and the imaginary part switches the sign simultaneously, the

quantity will have a significantly large value. As

can be smaller than unity when the imaginary part becomes zero, the

can be larger than unity. The plasmon resonance appears at a lower photon energy than that of the exciton for metallic (9,0) SWCNT. The same is not true for semiconducting (10,0) SWCNT. In the chosen window of the photon energy, i.e.,0.75 − 4.25 eV, (10,0) SWCNT has three intense exciton resonance peaks, while the (9,0) SWCNT has only one resonance peak in this energy range for each real, imaginary and energy-loss parts of the spectrum.

Knowing the conductivity of a single SWCNT, one can easily evaluate its dielectric response functions using

where

denotes the surface area of a SWCNT in which the charge is uniformly distributed, and

is the number of SWCNTs per unit volume. For an isolated SWCNT,

. Consequently,

. One can normalize the axial surface conductivity

of an SWCNT as

such that

is a dimensionless axial surface conductivity as a function of dimensionless energy

and an infinitesimal dimensionless energy

, where

is the carbon atom’s nearest neighbor overlap integral in a SWCNT. Substituting the value of

from Eq. (

6) to Eq. (

5), one gets,

Consequently, we have

for the real

and imaginary

parts of dielectric response. The loss function

, determined from the plasmon spectra, is given by

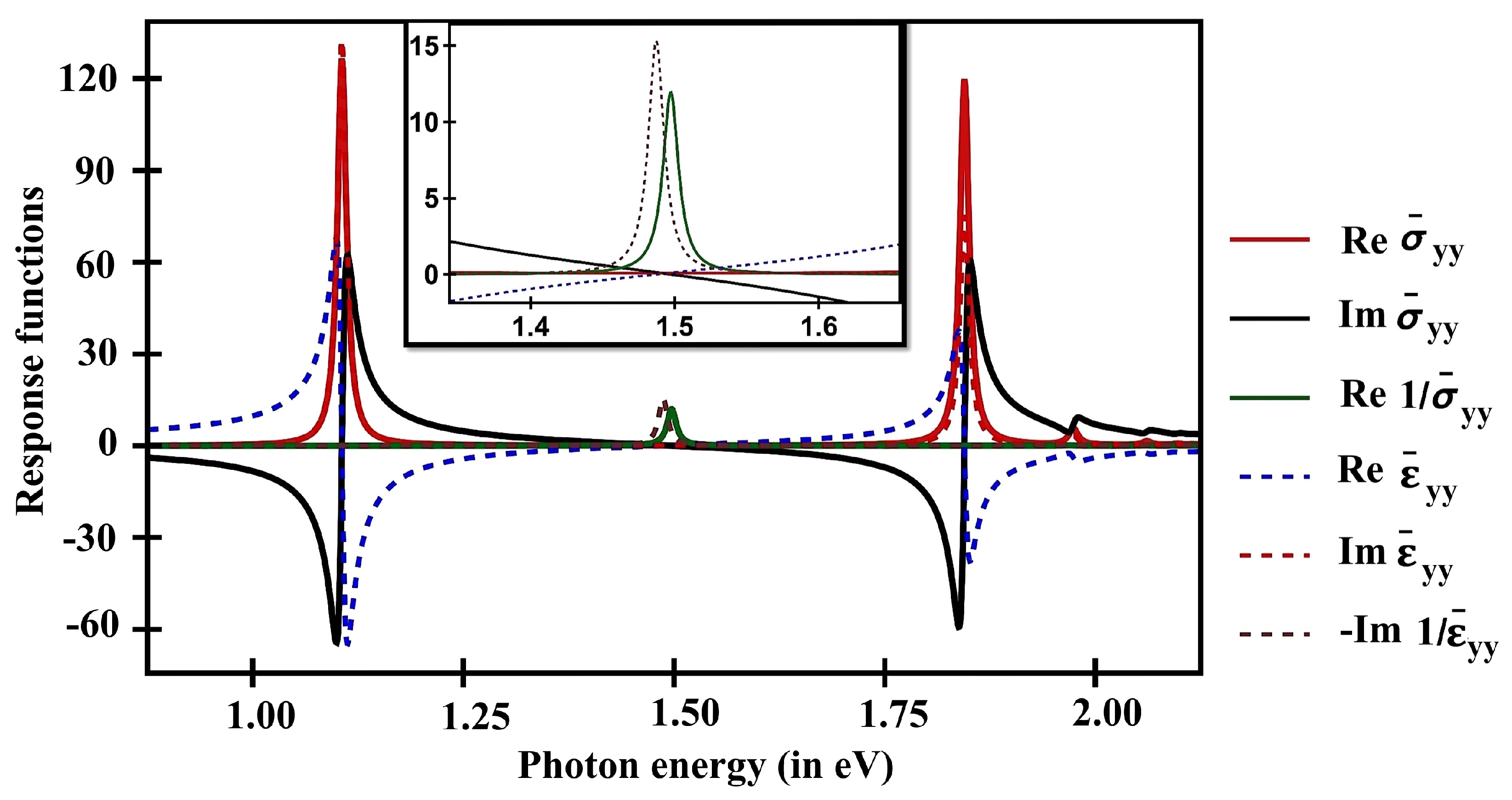

For an illustrative purpose, the dimensionless response functions, namely, longitudinal conductivities and longitudinal dielectric functions for a (11,0) SWCNT, are presented in

Figure 4.

gives us the surface plasmon’s density of states, which is nonzero when the imaginary part of

vanishes and the real part of

also approaches to zero. The quantity

is nonzero only if the

is zero and

approaches to zero at the same time.

3. Dielectric responses of SWCNT Films

From the principle of the second quantization, one can write the Hamiltonian of free exciton on the surface of the SWCNT as

where

is an exciton energy in its

s-subband.

is the electron’s quasimomentum in the plane, where

is the quasimomentum component along the SWCNT alignment and

is along the perpendicular direaction to the plane. The exciton annihilation

and creation

operators follow boson statistics and satisfy the following identities:

The complication arises when we have not just a single SWCNT but an array of SWCNTs as they interact via dipole-dipole interaction. The interaction Hamiltonian can written as [

17]

where

is the interaction potential with

being the transition dipole associated with

s-subband excitation.

,

,

a, and

are the intraband plasma oscillation frequency, the surface electron density, the lattice translation period, and the Fourier transform of the SWCNTs’ dipole-dipole interaction, respectively. The total Hamiltonian of the system is the sum of Eqs. (

10) and (

12):

which can be analytically diagonalized using the Bogoliubov-Valatin transformation as presented in Ref [

44].

For the SWCNT array, the dielectric response is anisotropic, which along the direction perpendicular to the SWCNT alignment remains constant with the value of the dielectric constant of host medium, while along the SWCNT alignment, it is given as [

17]

where

is the ratio of the SWCNTs volume to the volume of the host dielectric medium.

measures how sparse SWCNTs are in the film.

has a lower value for larger intertube distance and satisfies

, implying that screening of host dielectric medium always present in SWCNT array even at the very tightly packed SWCNT array. The screening leads to broadening excitonic and plasmonic peaks and enhancing exciton-plasmon coupling.

and

in Eq. (

15) are the zeroth-order modified cylindrical Bessel functions. The dielectric response of the SWCNT array is not only the function of photon energy and SWCNT radius similar to a single SWCNT, but it is also a function of the volumetric fraction

, permittivities

,

, and

of substrate, superstrate, and the dielectric medium holding the SWCNT array and quasi-momentum along the SWCNT alignment. Being the ratio of the physical quantities with the same dimensionality, the dielectric response function expressed in Eq. (

15) is a dimensionless quantity.

4. Discussion

For

, the right side of Eq. (

15) equals unity, implying that the dielectric response of the SWCNT array equals the host dielectric medium’s permittivity, which makes the dielectric response function isotropic. For the non-zero value of

or

, the

component of the dielectric response is a complex function. The

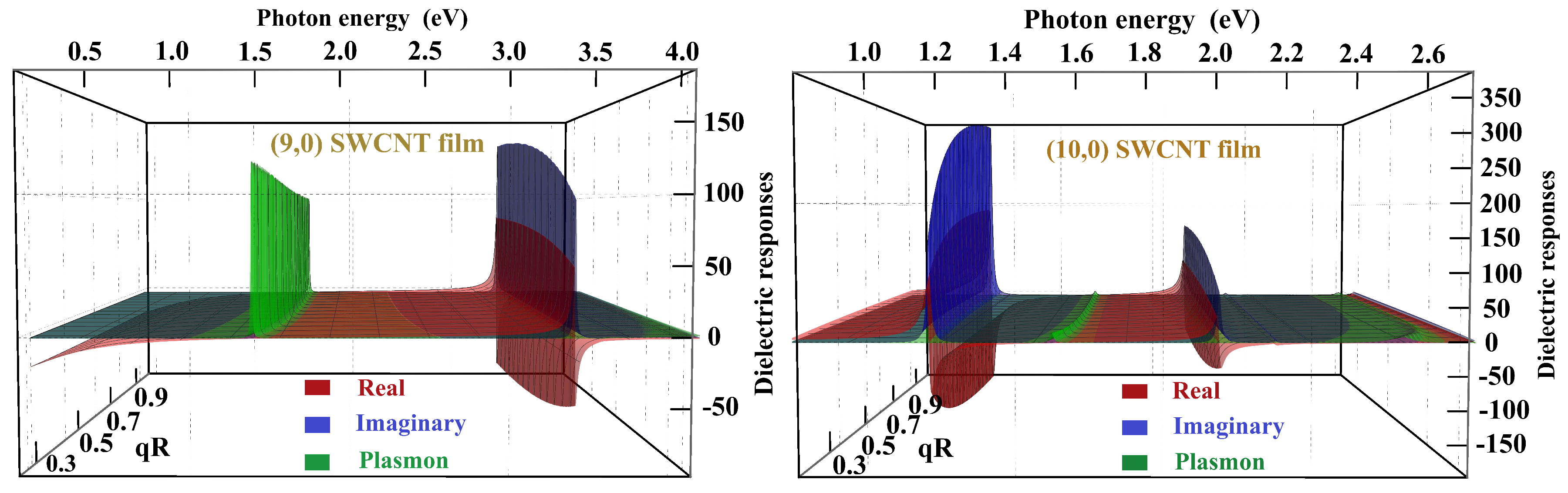

for two different composite films, one consisting of a periodic array of (9,0) SWCNTs and the other consisting of (10,0) SWCNTs, are presented in

Figure 5. The SWCNT layers are embedded in a dielectric medium of thickness

and relative permittivity

, where

R is the radius of the respective film’s SWCNT. The fractional volume of CNT in both these composites is

. The real part

represents the exciton refraction resonance, the imaginary

represents the exciton absorption resonance, and

represents the plasmon response. The plasmon mode has a resonance at the point in which

changes sign from negative to positive, and

approaches to zero. The plasmon response is positive for the entire energy range, indicating that energy loss is unavoidable. Even in the wide range of energy window (up to ∼ 4.0 eV), only one resonance is present for (9,0) SWCNT film. However, one witnesses two resonances for (10,0) SWCNT film for photon energy up to ∼ 2.6 eV. The plasmon resonance appears at a lower energy than the excitonic resonance for (9,0) SWCNT film. The same is not true (10,0) SWCNT film. The plasmon spectrum is comparatively more pronounced in (9,0) than in (10,0) SWCNT film.

The real part

of the dielectric response function is negative for a large range of photon energy for both (9,0) and (10,0) SWCNT films, making both SWCNT films good candidates for hyperbolic metamaterials. The energy range, however, depends on the chirality of constituent SWCNTs. The exciton-plasmon spectra of homogenous arrays of any metallic SWCNTs such as (12,0), (15,0), (18,0), etc SWCNTs are expected to behave similarly to (9,0) SWCNT arrays. At the same time, resonance intensity and photon energy for resonances depend on the particular metallic SWCNT that the film consists of. The SWCNT films are made up of semiconducting SWCNT arrays such as (13,0), (16,0), (19,0), etc. SWCNTs have similar behavior to an array of (10,0) SWCNTs. The exciton-plasmon coupling strength is stronger in the SWCNT array than in a single SWCNT. The inhomogeneity effect abruptly increases the exciton-plasmon coupling [

15] for a mixture of SWCNTs of slightly different diameters. Comparing the dielectric responses for a single homogeneous array presented in Ref. [

14], one can conclude that the dielectric medium contains more than a single array of identical SWCNTs, the intensity of the response function increases.

Substituting the expression of the volume of an isolated SWCNT and the composite volume,

can be expressed as

, which depends on the thickness of the film and SWCNT sparseness. Choosing a fixed value of

, one can observe the effect of film thickness on the exciton-plasmon spectra varying the value of

. Note that

is smaller for a larger value of

d.

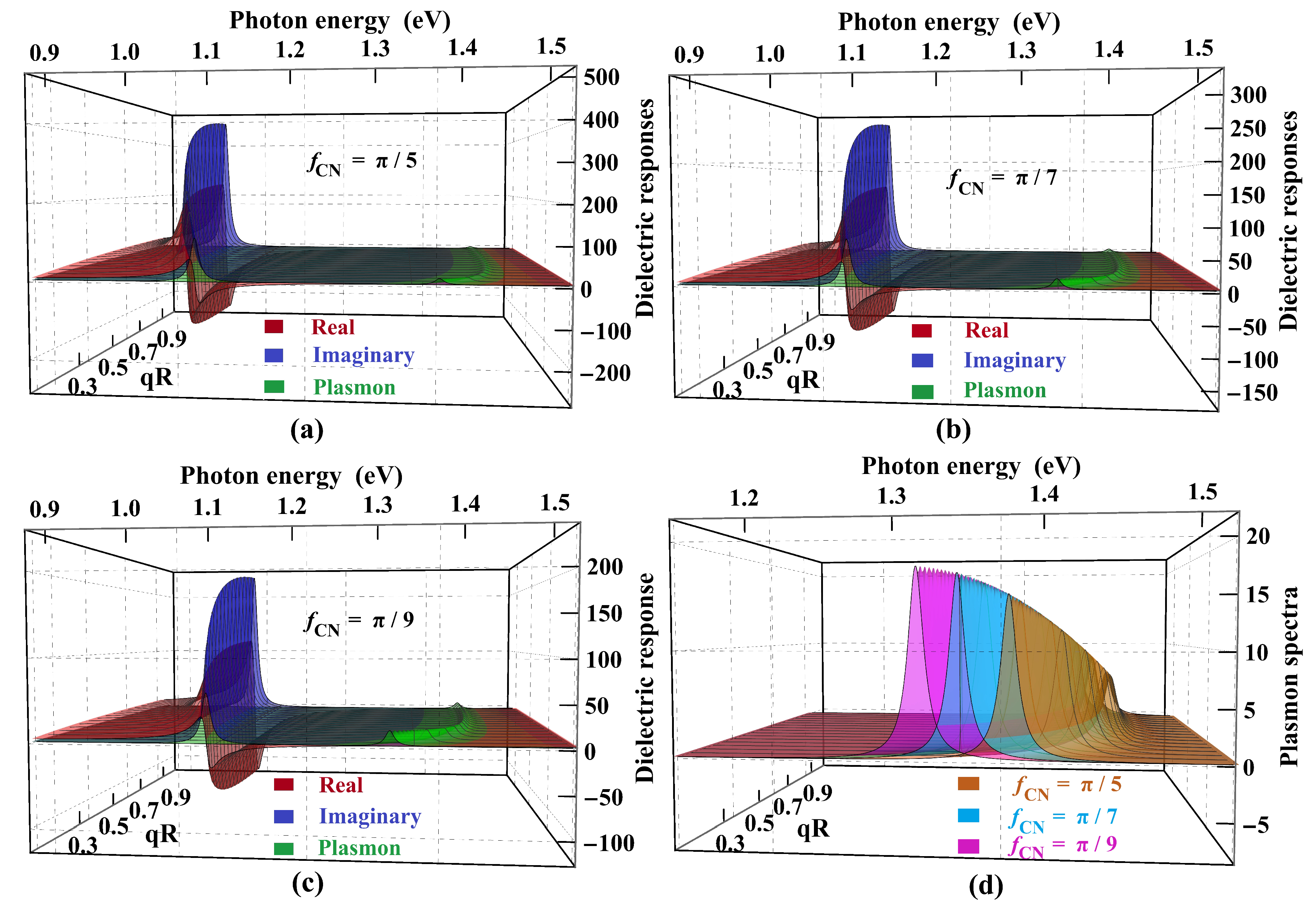

Figure 6 shows a comparative study of dielectric responses for three different values of

.

As shown in Eq. (

15), the dielectric response function of the SWCNT array is electron quasi-momentum

q-dependent. The minimum non-zero value that

q can take is

, where

L is the length of a SWCNT. One can dig a little more into how the length of a SWCNT plays a role in the minimum value of

q. For

, the longitudinal component of the response functions reads

where

is the length of a SWCNT in terms of its circumference. See

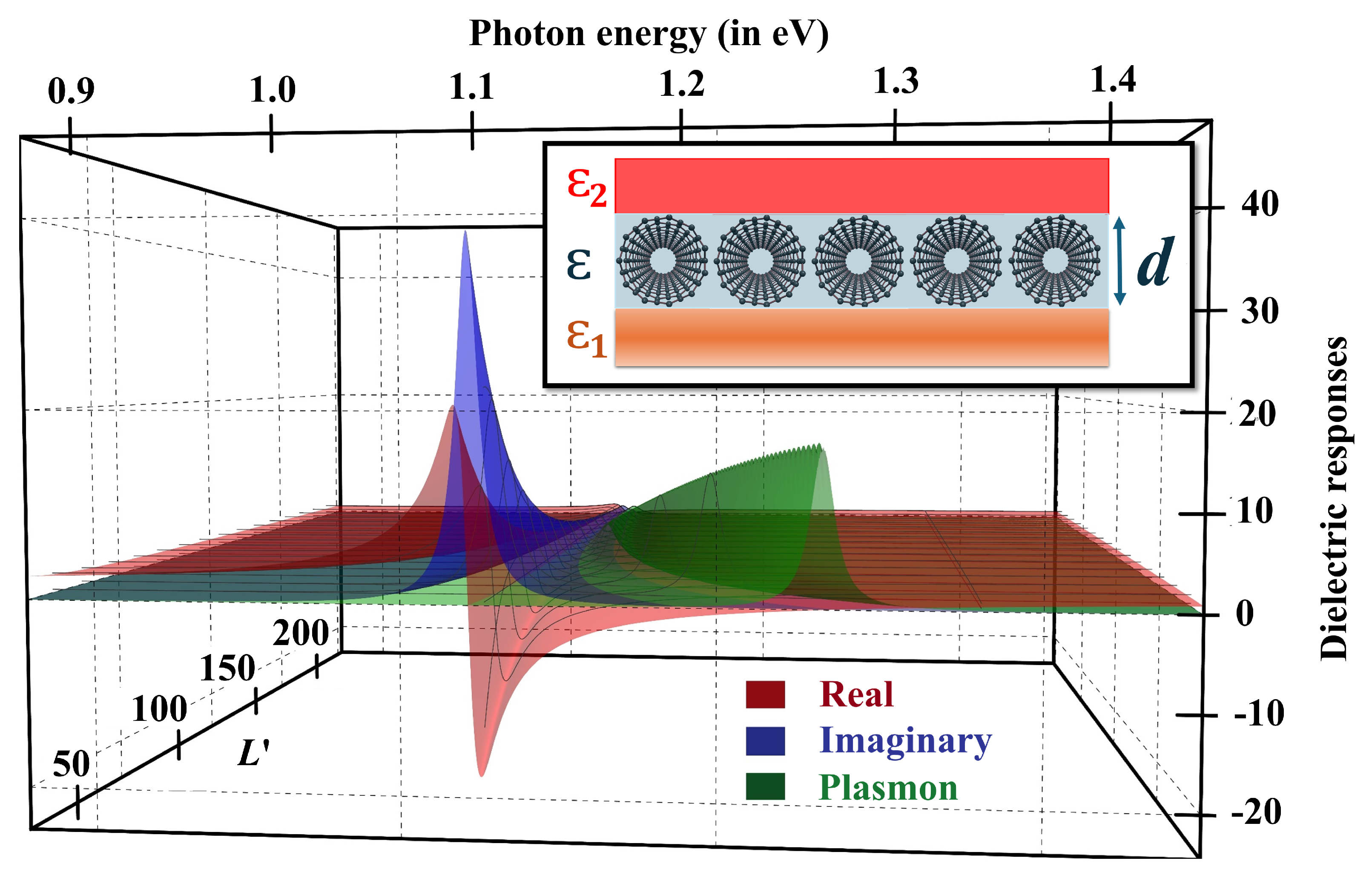

Figure 7 for the dielectric response function at the minimum nonzero value of momentum

.

The major contribution to the dielectric response comes from the momentum. At the same time, one should not forget that with also have a non-zero contribution to the response function, which decays exponentially. The exciton and the plasmon resonances approach each other more closely for than for the larger q. However, the intensity of each of the resonance peaks for is smaller than the large q counterpart. Thus, the resonance intensity and exciton-plasmon coupling strength depend on the SWCNT length. The momentum has a lower value for a longer SWCNT than the shorter one. As the CNT length increases, the plasmon resonance comes closer to the exciton resonance strengthening the exciton-plasmon coupling.

Making use of SWCNTs and their thin films in the current technology is not free from challenges. One of the major challenges using the currently available synthesis methods is producing SWCNTs of a specific chirality and their scalability [

45]. Although some claims on producing pure SWCNTs have been reported, some issues, such as removing amorphous carbon, washing out metallic catalysts after catalytic SWCNT synthesis, and yielding defect-free SWCNTs, remain [

46]. As chirality control is usually an issue in SWCNT production, having a consistent film thickness, as this article proposed, needs extra work in the experimental setup, which may have not only inhomogeneous mixing of SWCNTs of different chirality but also have tubular misalignment and inter-tube junction resistance due to phonon scattering. The phonon scattering at the inter-tube junction reduces the conductivity of SWCNT film. In future studies, we will focus on the phonon scattering at inter-tube junctions and its effect on dielectric responses in the homogeneous SWCNT arrays and inhomogeneous arrays of SWCNTs of approximately the same diameters. Future work will concentrate on creating hybrid materials combining SWCNTs with other materials, such as graphene and polymers, in search of optoelectronic performance enhancements.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram showing the rolling direction for the most general chiral with chirality vector and two special cases of achiral, namely, zigzag for and armchair SWCNTs.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram showing the rolling direction for the most general chiral with chirality vector and two special cases of achiral, namely, zigzag for and armchair SWCNTs.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram showing a planner periodic array of identical non-chiral SWCNTs taken in our theoretical model.

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram showing a planner periodic array of identical non-chiral SWCNTs taken in our theoretical model.

Figure 3.

Dimensionless conductivities of a (9,0) (left panel) and (10,0) (Right panel) SWCNTs along the corresponding CNT axis as a function of photon energy (expressed in eV).

Figure 3.

Dimensionless conductivities of a (9,0) (left panel) and (10,0) (Right panel) SWCNTs along the corresponding CNT axis as a function of photon energy (expressed in eV).

Figure 4.

Dimensionless conductivities and dimensionless dielectric functions of a (11,0) SWCNT along the SWCNT axis plotted as a function of photon energy (expressed in eV). Only the first two excitonic peaks and a plasmonic peak are shown. For better visibility, curves and are scaled by . In the inset, the magnified version of the curves near the resonances of and are shown.

Figure 4.

Dimensionless conductivities and dimensionless dielectric functions of a (11,0) SWCNT along the SWCNT axis plotted as a function of photon energy (expressed in eV). Only the first two excitonic peaks and a plasmonic peak are shown. For better visibility, curves and are scaled by . In the inset, the magnified version of the curves near the resonances of and are shown.

Figure 5.

Dimensionless dielectric responses of a periodic array of (9,0) SWCNTs (left panel) and (10,0) SWCNTs (right panel) along their CNT axis as a function of momentum times radius of respective CNT and the photon energy (expressed in eV). The relative permittivity of the substrate, superstrate, and dielectric medium are taken as 1, 1, and 20, respectively. Only the first resonances of the response functions are shown for (9,0) SWCNT film, while the first two resonances of the response functions are shown for (10,0) SWCNT film. The fractional density parameter is . The red colored surface represents the , the blue colored surface depicts the , and the negative of is shown by green colored surface.

Figure 5.

Dimensionless dielectric responses of a periodic array of (9,0) SWCNTs (left panel) and (10,0) SWCNTs (right panel) along their CNT axis as a function of momentum times radius of respective CNT and the photon energy (expressed in eV). The relative permittivity of the substrate, superstrate, and dielectric medium are taken as 1, 1, and 20, respectively. Only the first resonances of the response functions are shown for (9,0) SWCNT film, while the first two resonances of the response functions are shown for (10,0) SWCNT film. The fractional density parameter is . The red colored surface represents the , the blue colored surface depicts the , and the negative of is shown by green colored surface.

Figure 6.

Dimensionless dielectric functions of a periodic array of (11,0) CNTs along the CNT axis as a function of momentum times radius of (11,0) CNT and the photon energy (expressed in eV). The relative permittivities of the substrate, superstrate, and dielectric medium are taken as 1, 1, and 15, respectively. Only the first resonances of the response functions are shown. Three different scenarios if the values, namely, (a), (b), and (c) are taken. Figure (d) shows the comparison of plasmon spectra only for the cases chosen in (a), (b), and (c).

Figure 6.

Dimensionless dielectric functions of a periodic array of (11,0) CNTs along the CNT axis as a function of momentum times radius of (11,0) CNT and the photon energy (expressed in eV). The relative permittivities of the substrate, superstrate, and dielectric medium are taken as 1, 1, and 15, respectively. Only the first resonances of the response functions are shown. Three different scenarios if the values, namely, (a), (b), and (c) are taken. Figure (d) shows the comparison of plasmon spectra only for the cases chosen in (a), (b), and (c).

Figure 7.

Dimensionless dielectric responses of an ultrathin array of (11,0) CNTs along the CNT axis as a function of photon energy (expressed in eV) and length of a CNT , (expressed in terms of the circumference of a (11,0) CNT) for the mimimum nonzero momentum . The CNTs are tightly packed, and the thickness of the film equals the diameter of a (11,0) CNT making . The inset shows the geometry related to the SWCNT film.

Figure 7.

Dimensionless dielectric responses of an ultrathin array of (11,0) CNTs along the CNT axis as a function of photon energy (expressed in eV) and length of a CNT , (expressed in terms of the circumference of a (11,0) CNT) for the mimimum nonzero momentum . The CNTs are tightly packed, and the thickness of the film equals the diameter of a (11,0) CNT making . The inset shows the geometry related to the SWCNT film.