Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Identification of Macroalgae Samples

2.2. Extraction of Fucoidan

2.3. Preparation of Fucoidan Solution

2.4. Biosynthesis of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

2.5. Characterization of Au-NPs

2.6. In Vitro

2.6.1. Antioxidant Activity

DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picryl-Hydrazyl-Hydrate) Free Radical Scavenging Assay

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.6.2. Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Effect

Cell Culture and General Conditions

SRB Assay for Normal BNL Cells

MTT Assay for HepG2 Cells

WST-1 Assay for THP1 Cells

2.6.3. Determination of Anticancer Effects

Cell Cycle Analysis by Flow Cytometry

2.7. In-Silico Study

2.7.1. Target Prediction

2.7.2. Protein Preparation

2.7.3. Ligand Preparation

2.7.4. Binding Site Prediction

2.7.5. Molecular Docking

2.8. Statistical analysis

3. Results

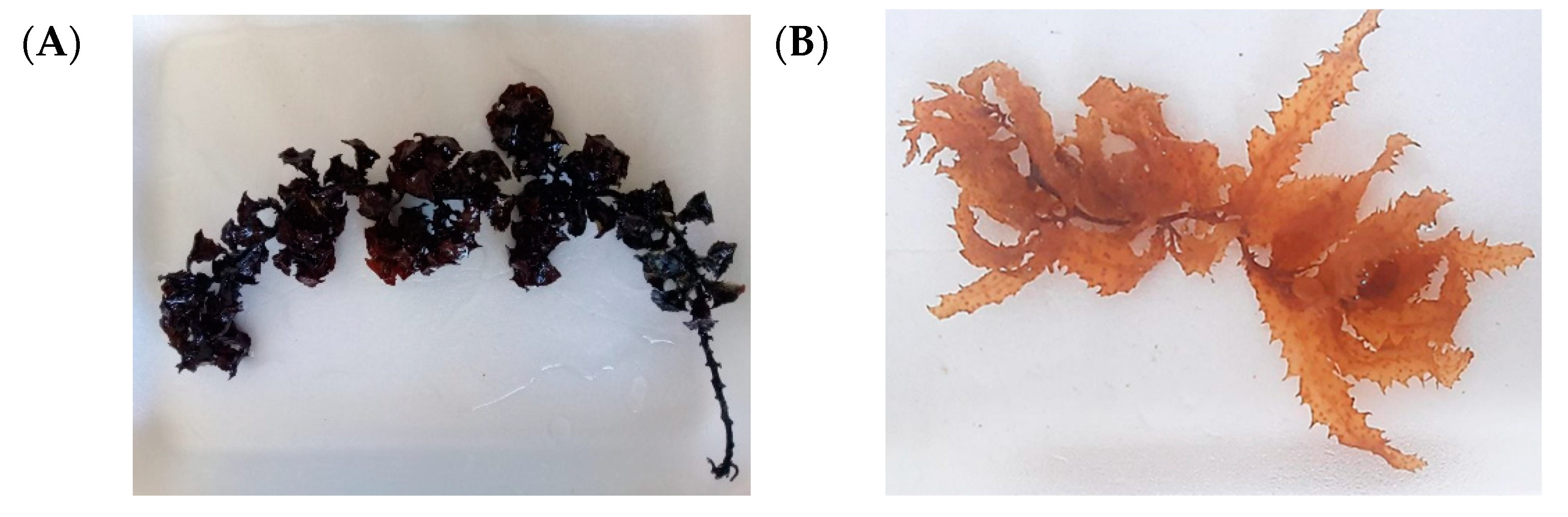

3.1. Identification of Macroalgae Samples

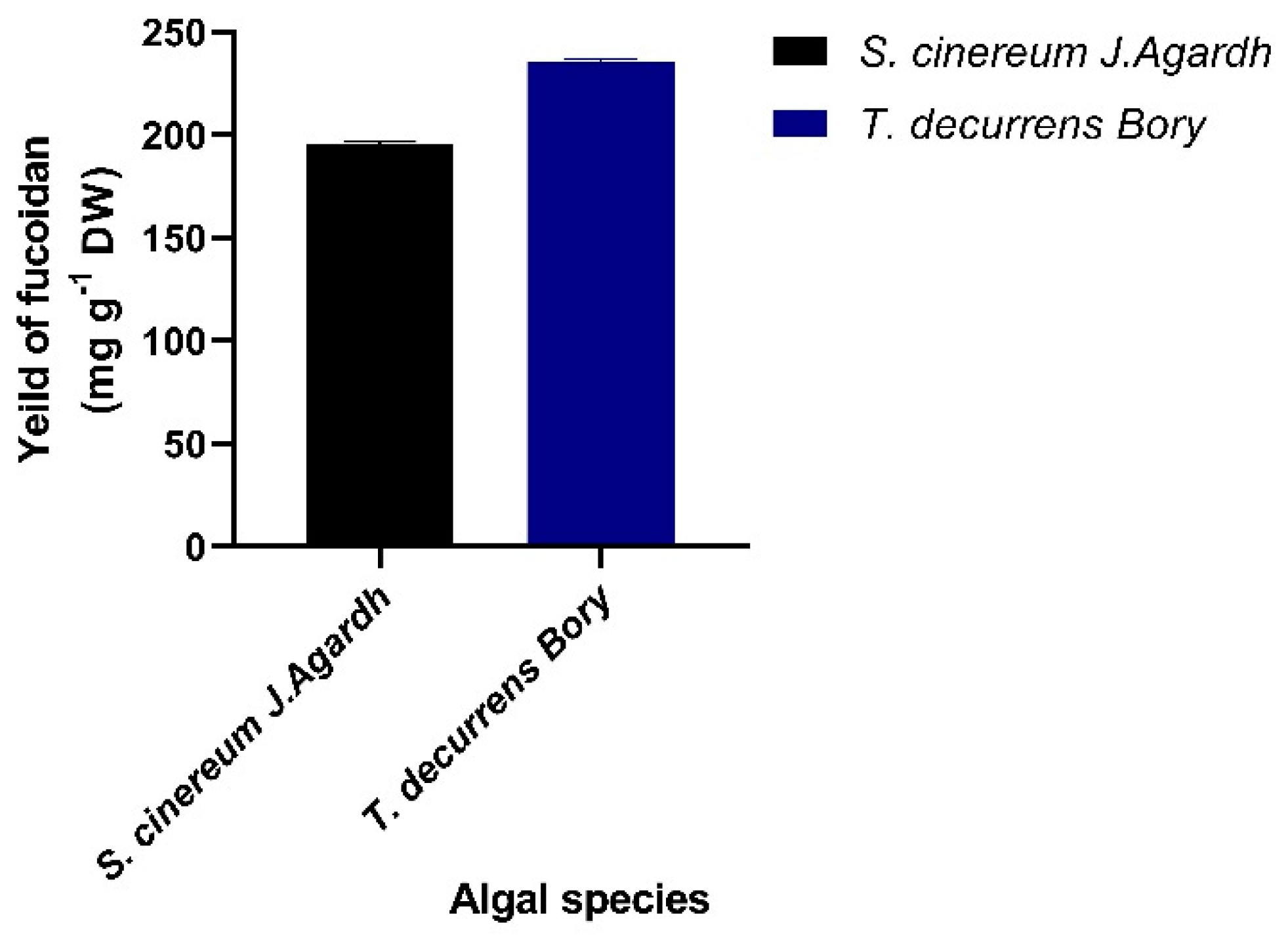

3.2. Extraction of Fucoidan

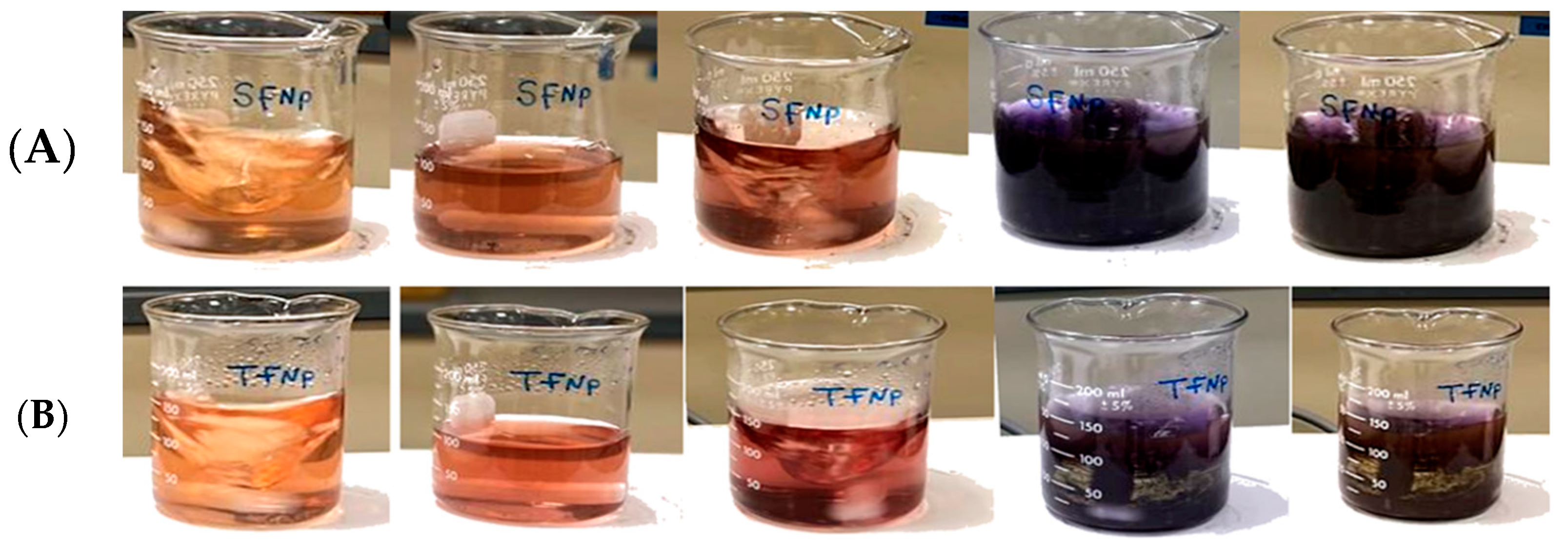

3.3. Synthesis of Fucoidan Derived Gold Nano (F-AuNPs)

Morphological Visual Observations

3.4. Characterization of Au-NPs

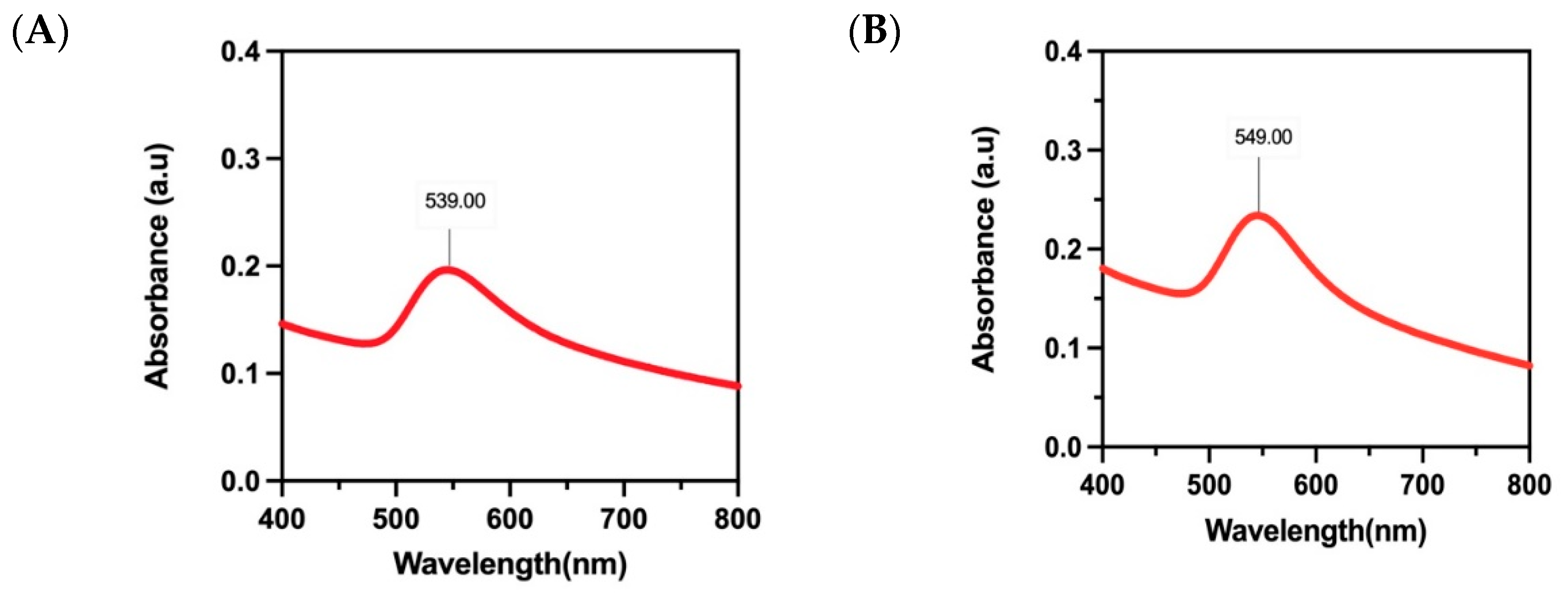

3.4.1. UV–vis Spectral Studies

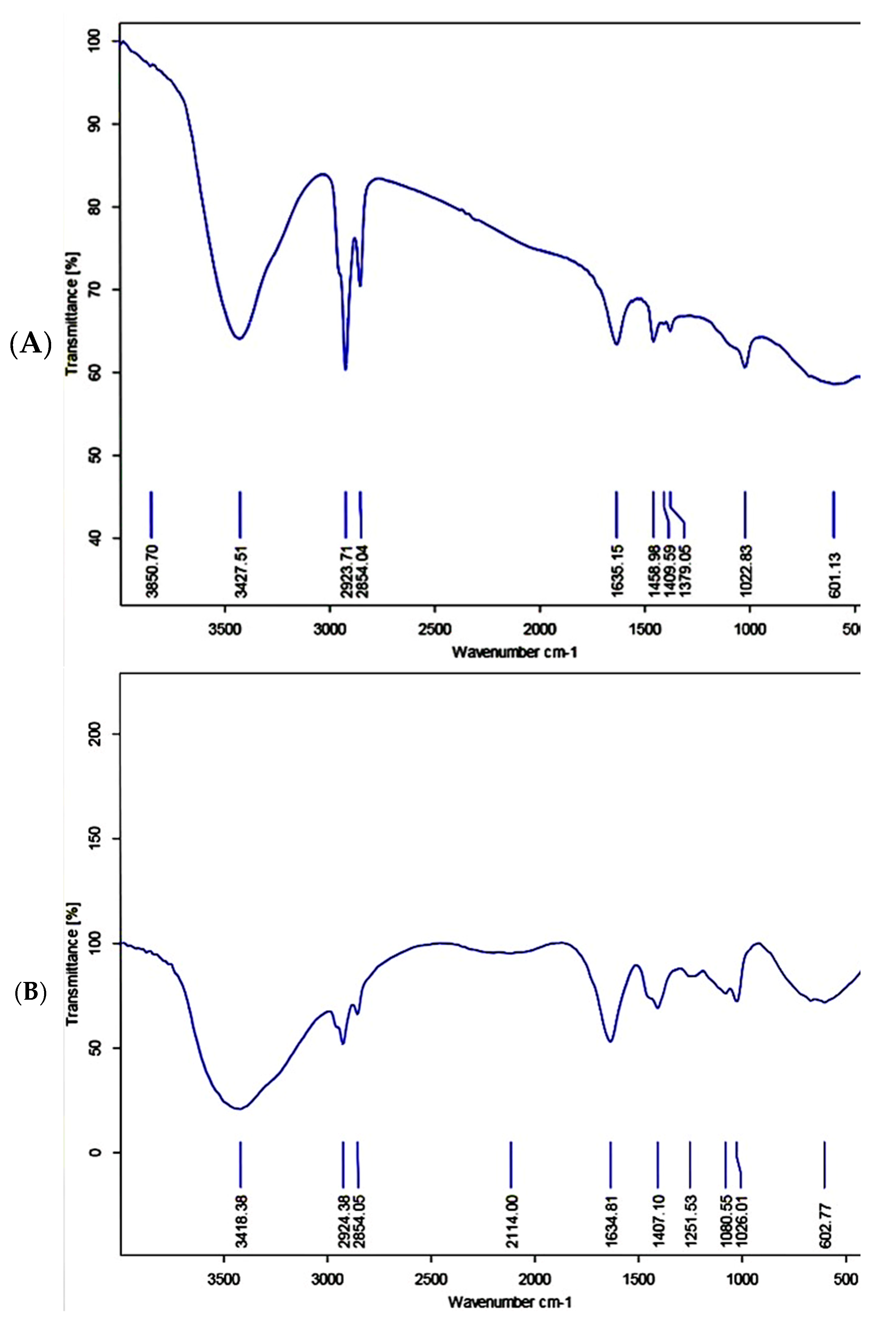

3.4.2. Fucoidan-Gold Nanoparticle FT-IR Spectroscopy Analysis

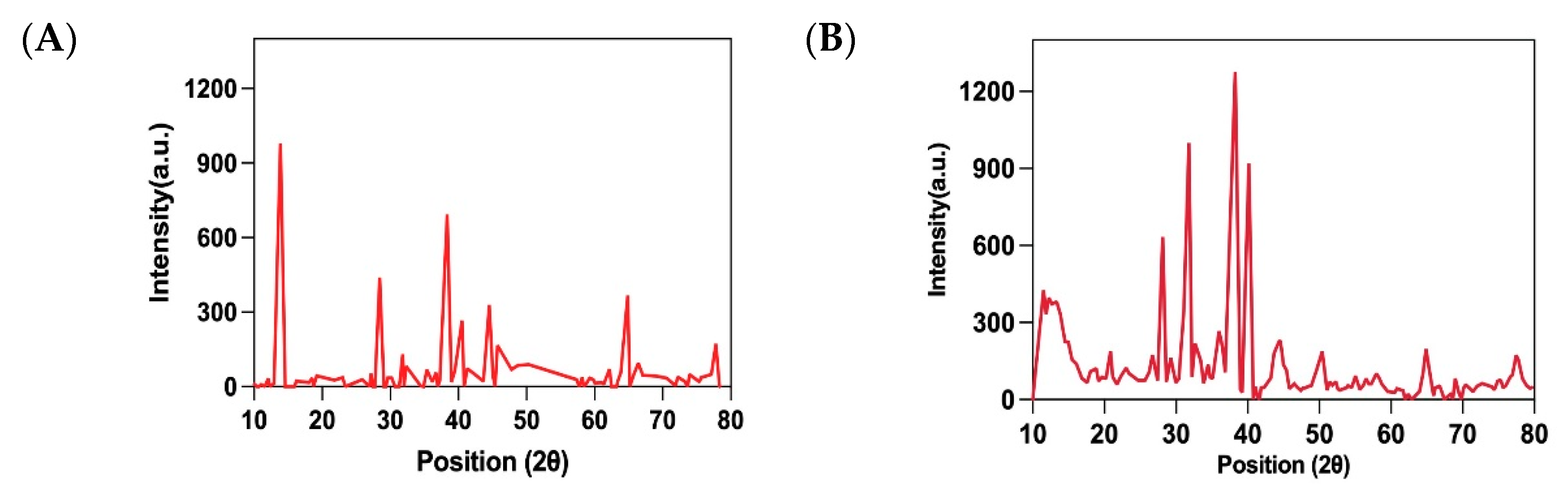

3.4.3. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of F-AuNPs

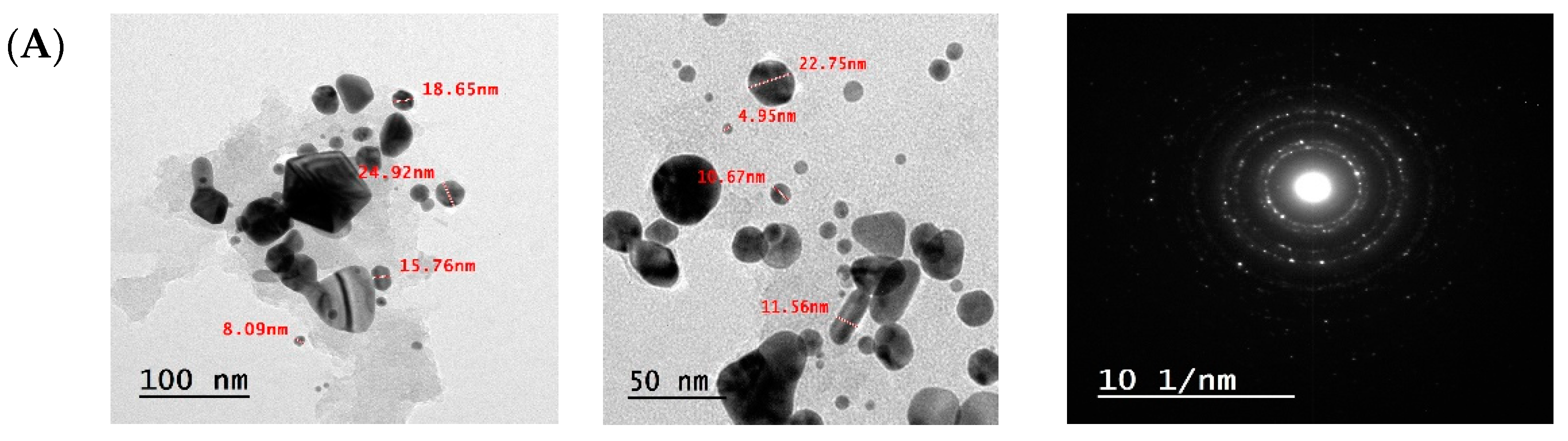

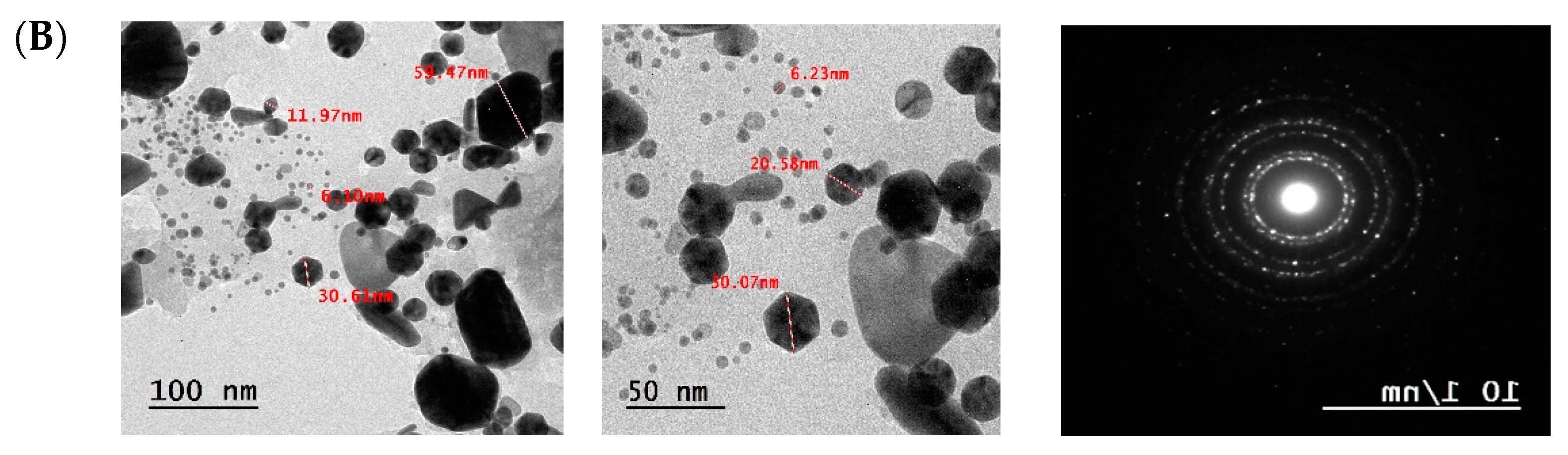

3.4.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis of F-AuNPs

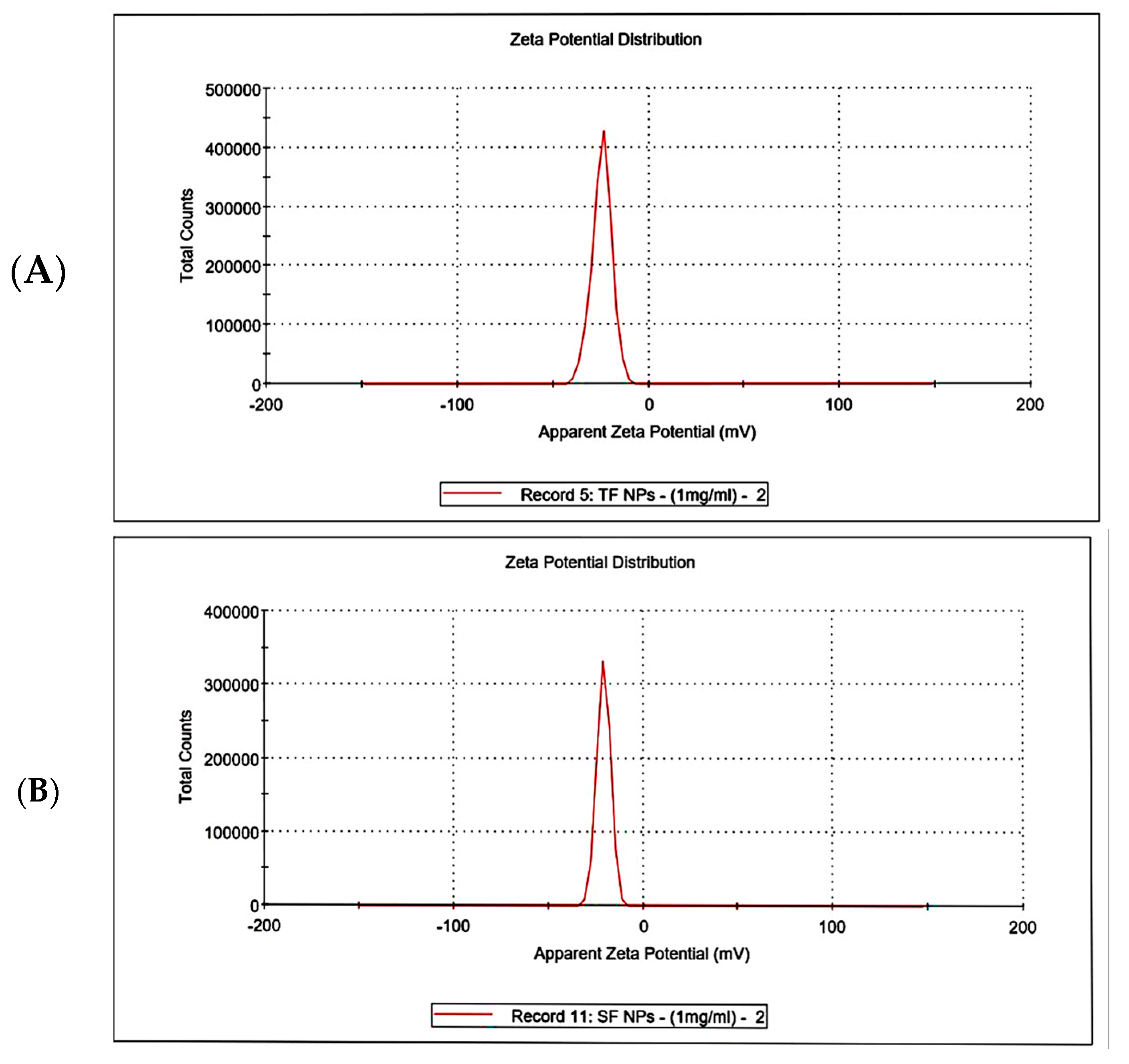

3.4.5. Zeta Potential Analysis

3.5. Antioxidant activity

3.5.1. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Assay

3.5.2. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

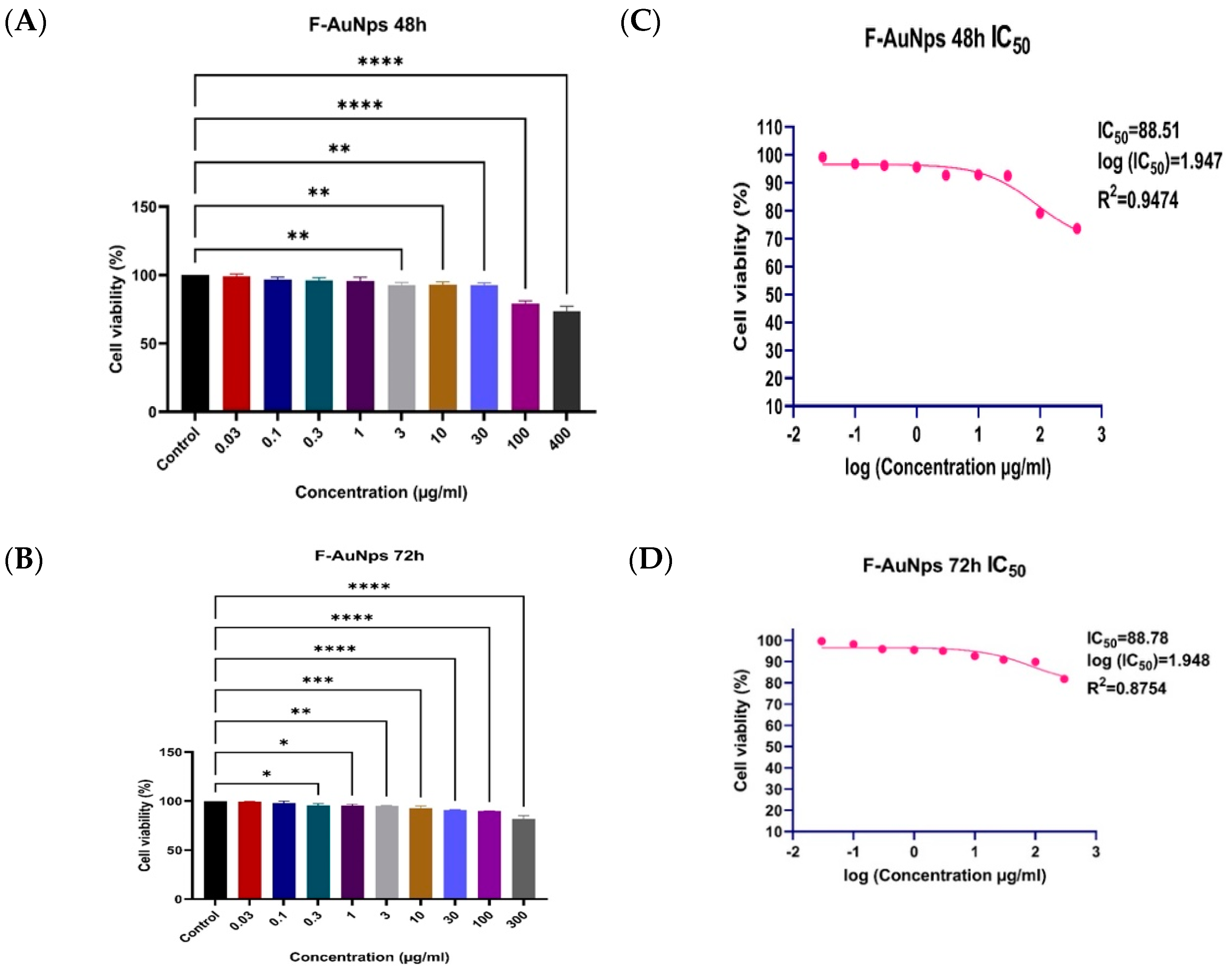

3.6. SRB Assay for Normal BNL Cells

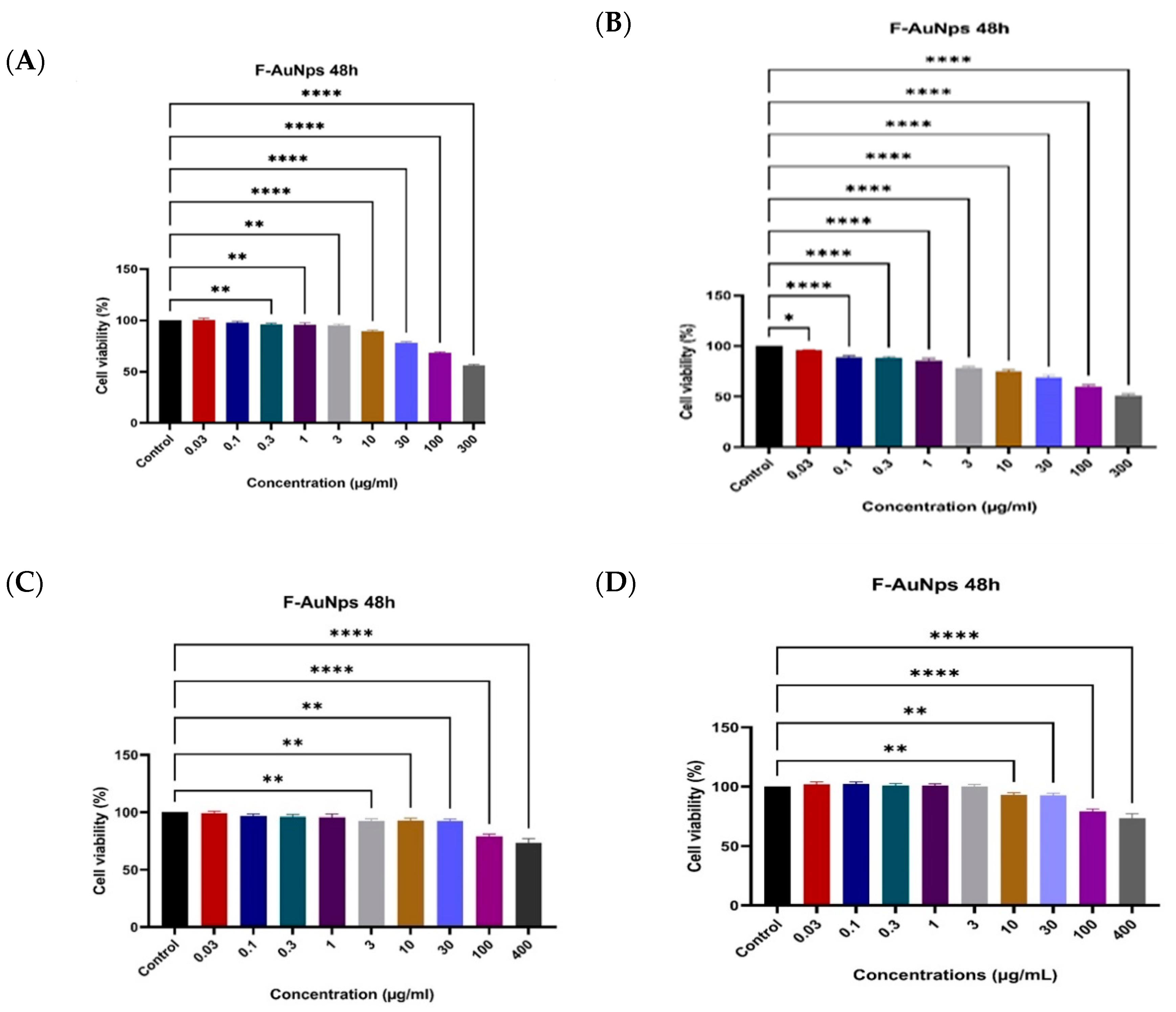

3.7. MTT Assay for HepG2 Cells and SRB Assay for THP1

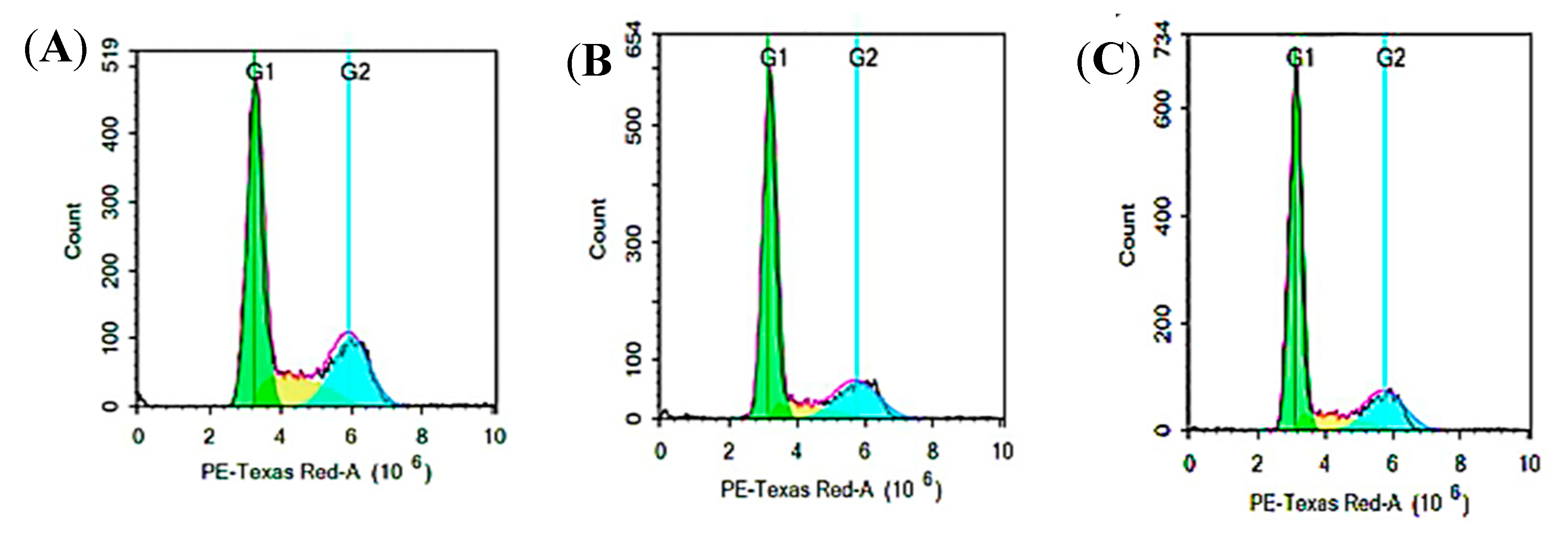

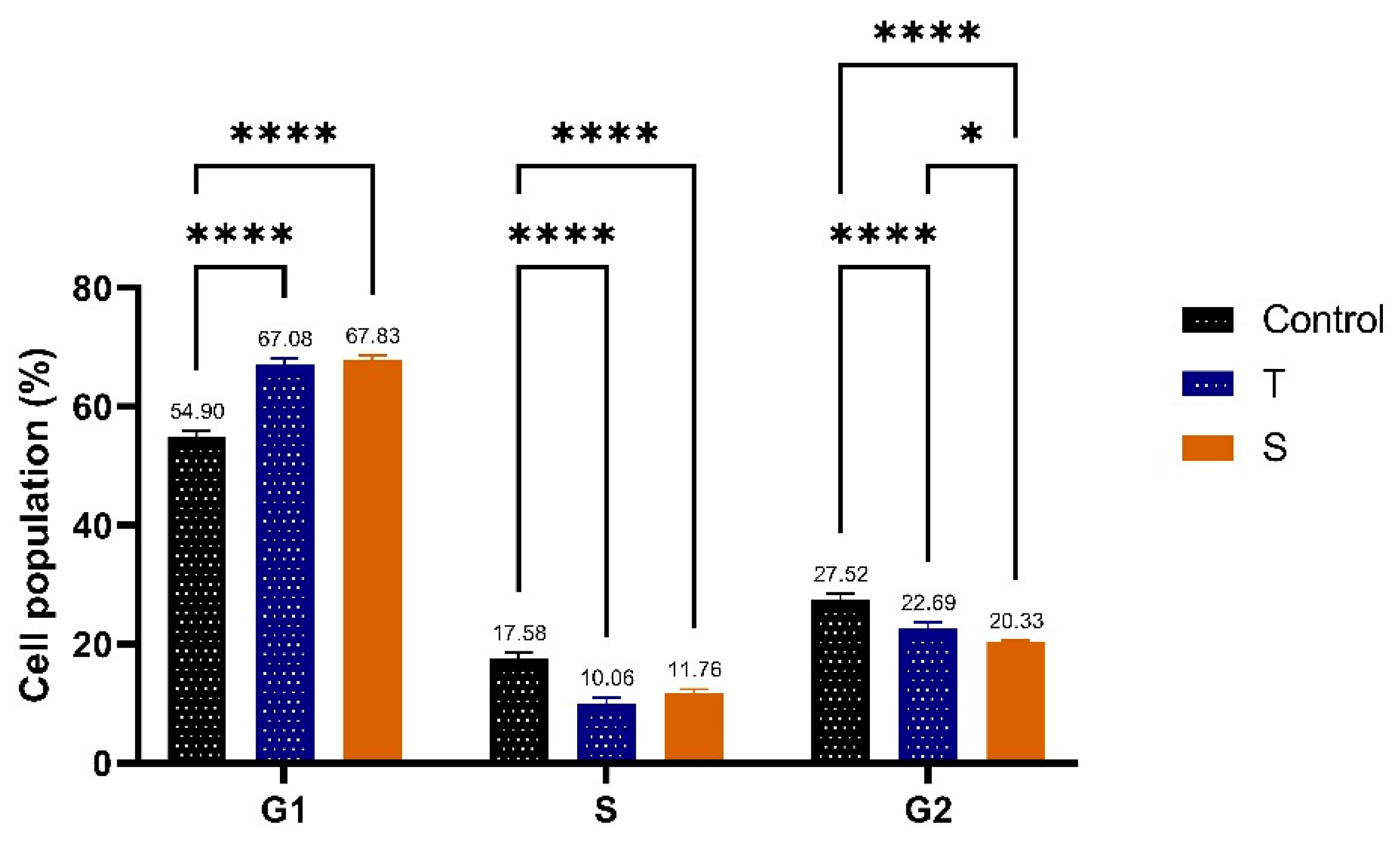

3.8. Cell Cycle Analysis by Flow Cytometry

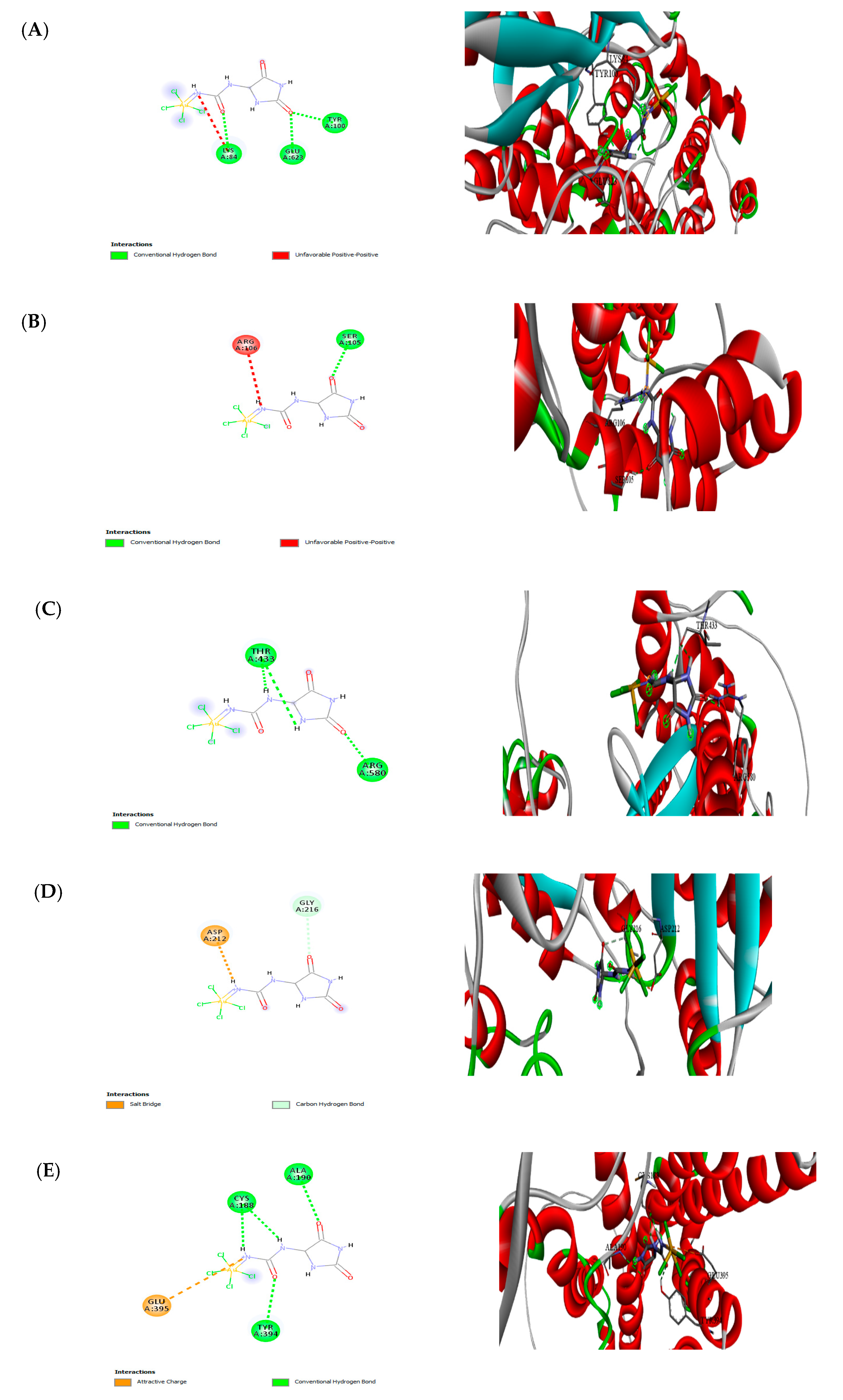

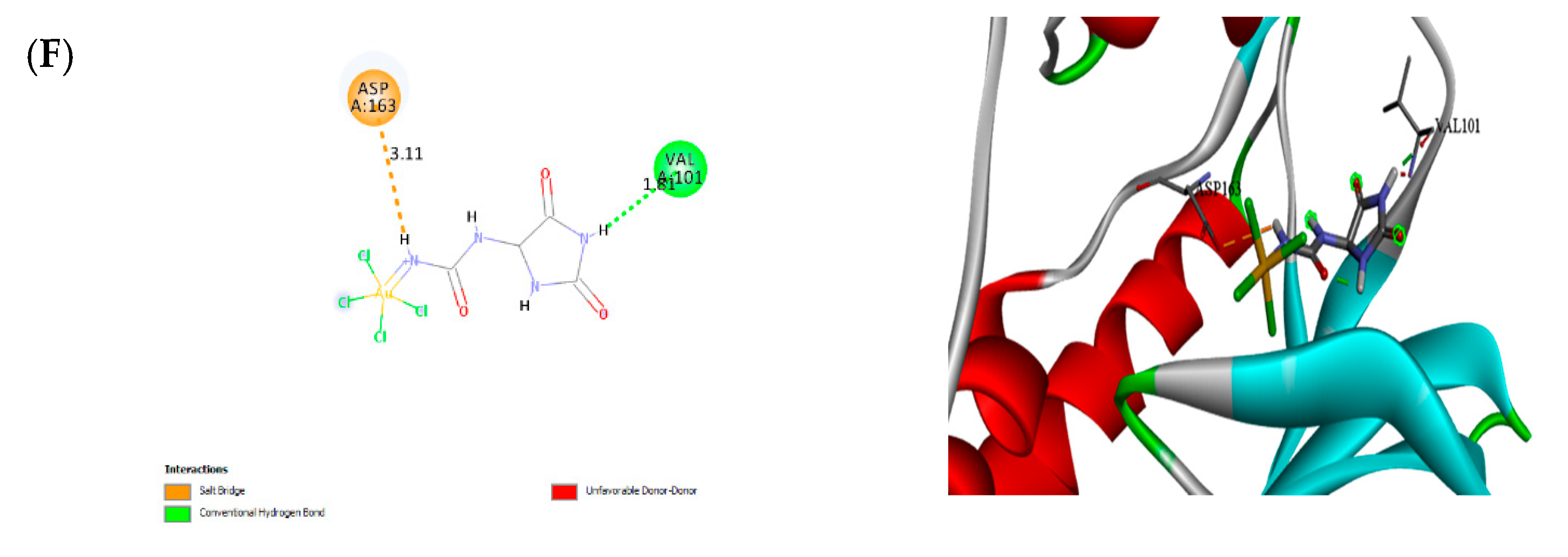

3.9. Molecular Docking

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- K. Dzobo, “The role of natural products as sources of therapeutic agents for innovative drug discovery,” Compr. Pharmacol., 2022,p. 408. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Khalifa et al., “Marine natural products: A source of novel anticancer drugs,” Mar. Drugs, 2019, vol. 17, no. 9, p. 491. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Osman et al., “The seasonal fluctuation of the antimicrobial activity of some macroalgae collected from Alexandria Coast, Egypt,” Salmonella-Distrib. Adapt. Control Meas. Mol. Technol. InTech, 2012, pp. 173–186.

- L. Pereira and A. Valado, “Harnessing the power of seaweed: Unveiling the potential of marine algae in drug discovery,” Explor. Drug Sci., 2023,vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 475–496. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Olasehinde and A. O. Olaniran, “Antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing effects of aqueous extracts from Ecklonia maxima and Ulva rigida on HepG2 cells,” J. Food Biochem., 2022, vol. 46, no. 12, p. e14498.

- J. Cao et al., “Advances in the research on micropropagules and their role in green tide outbreaks in the Southern Yellow Sea,” Mar. Pollut. Bull.,2023, vol. 188, p. 114710. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, Y. Sun, H. Liu, S. Liu, Y. Qin, and P. Li, “Advances in cultivation, wastewater treatment application, bioactive components of Caulerpa lentillifera and their biotechnological applications,” PeerJ, 2019, vol. 7, p. e6118.

- B. Koul, Herbs for cancer treatment. Springer Nature, 2020.

- B. Liu, H. Zhou, L. Tan, K. T. H. Siu, and X.-Y. Guan, “Exploring treatment options in cancer: tumor treatment strategies,” Signal Transduct. Target. Ther., 2024,vol. 9, no. 1, p. 175.

- R. Al Monla, Z. Dassouki, N. Sari-Chmayssem, H. Mawlawi, and H. Gali-Muhtasib, “Fucoidan and alginate from the brown algae Colpomenia sinuosa and their combination with vitamin C trigger apoptosis in colon cancer,” Molecules, 2022,vol. 27, no. 2, p. 358. [CrossRef]

- B. Li, F. Lu, X. Wei, and R. Zhao, “Fucoidan: structure and bioactivity,” Molecules, 2008, vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 1671–1695.

- F. Atashrazm, R. M. Lowenthal, G. M. Woods, A. F. Holloway, and J. L. Dickinson, “Fucoidan and cancer: A multifunctional molecule with anti-tumor potential,” Mar. Drugs,2015, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 2327–2346. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Sanjeewa and Y.-J. Jeon, “Fucoidans as scientifically and commercially important algal polysaccharides,” Mar. Drugs, 2021, vol. 19, no. 6, p. 284.

- S. Huo et al., “A preliminary study on polysaccharide extraction, purification, and antioxidant properties of sugar-rich filamentous microalgae Tribonema minus,” J. Appl. Phycol., 2022, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 2755–2767. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Barakat, M. M. Ismail, H. E. Abou El Hassayeb, N. A. El Sersy, and M. E. Elshobary, “Chemical characterization and biological activities of ulvan extracted from Ulva fasciata (Chlorophyta),” Rendiconti Lincei Sci. Fis. E Nat., 2022, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 829–841.

- K. Senthilkumar, P. Manivasagan, J. Venkatesan, and S.-K. Kim, “Brown seaweed fucoidan: biological activity and apoptosis, growth signaling mechanism in cancer,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol.,2013, vol. 60, pp. 366–374.

- P. Manivasagan et al., “Doxorubicin-loaded fucoidan capped gold nanoparticles for drug delivery and photoacoustic imaging,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2016, vol. 91, pp. 578–588.

- P. Elia, R. Zach, S. Hazan, S. Kolusheva, Z. Porat, and Y. Zeiri, “Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using plant extracts as reducing agents,” Int. J. Nanomedicine, 2014,pp. 4007–4021.

- I. H. Hameed, H. J. Altameme, and G. J. Mohammed, “Evaluation of antifungal and antibacterial activity and analysis of bioactive phytochemical compounds of Cinnamomum zeylanicum (Cinnamon bark) using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry,” Orient. J. Chem., 2016,vol. 32, no. 4, p. 1769. [CrossRef]

- G. Corso, A. Deng, B. Fry, N. Polizzi, R. Barzilay, and T. Jaakkola, “Deep confident steps to new pockets: Strategies for docking generalization,” ArXiv, 2024.

- F. Taylor, “The taxonomy and relationships of red tide flagellates,” Toxic Dinoflagelletas, 1985,pp. 11–26.

- A. Aleem, “Contributions to the study of the marine algae of the Red Sea,” Bull Fac Sci KAU Jeddah, 1978, vol. 2, pp. 99–118.

- A. A. Aleem, The marine algae of Alexandria, Egypt. 1993.

- R. M. Oza and S. Zaidi, “A revised checklist of Indian marine algae,” CSMCRI Bhavnagar, 2001,vol. 296.

- Guiry, M. D. and Guiry, G. M. (2022). In., “AlgaeBase. https://www.algaebase.org/.”.

- M. Tako, “Rheological characteristics of fucoidan isolated from commercially cultured Cladosiphon okamuranus,” 2003.

- C. G. Boeriu, D. Bravo, R. J. Gosselink, and J. E. van Dam, “Characterisation of structure-dependent functional properties of lignin with infrared spectroscopy,” Ind. Crops Prod., 2004,vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 205–218.

- R. Boly, T. Lamkami, M. Lompo, J. Dubois, and I. Guissou, “DPPH free radical scavenging activity of two extracts from Agelanthus dodoneifolius (Loranthaceae) leaves,” Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res., 2016,vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 29–34.

- N. S. Elkholy, M. L. M. Hariri, H. S. Mohammed, and M. W. Shafaa, “Lutein and β-carotene characterization in free and nanodispersion forms in terms of antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity,” J. Pharm. Innov., 2023,vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 1727–1744. [CrossRef]

- I. F. Benzie and J. J. Strain, “The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ‘antioxidant power’: the FRAP assay,” Anal. Biochem., 1996,vol. 239, no. 1, pp. 70–76.

- D. Gfeller, A. Grosdidier, M. Wirth, A. Daina, O. Michielin, and V. Zoete, “SwissTargetPrediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules,” Nucleic Acids Res., 2014,vol. 42, no. W1, pp. W32–W38.

- J. Eberhardt, D. Santos-Martins, A. F. Tillack, and S. Forli, “AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings,” J. Chem. Inf. Model., 2021,vol. 61, no. 8, pp. 3891–3898.

- M. D. Hanwell, D. E. Curtis, D. C. Lonie, T. Vandermeersch, E. Zurek, and G. R. Hutchison, “Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform,” J. Cheminformatics,2021, vol. 4, pp. 1–17.

- X. Liu et al., “The direct STAT3 inhibitor 6-ethoxydihydrosanguinarine exhibits anticancer activity in gastric cancer,” Acta Mater. Medica, 2022,vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 365–380.

- G. M. Morris et al., “AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility,” J. Comput. Chem., 2009, vol. 30, no. 16, pp. 2785–2791.

- M. T. Ale and A. S. Meyer, “Fucoidans from brown seaweeds: An update on structures, extraction techniques and use of enzymes as tools for structural elucidation,” Rsc Adv., 2013,vol. 3, no. 22, pp. 8131–8141.

- M. El-Sheekh, E. A. Alwaleed, W. M. Kassem, and H. Saber, “Optimizing the fucoidan extraction using Box-Behnken Design and its potential bioactivity,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2024,vol. 277, p. 134490.

- F. N. L. LUTFIA, A. Isnansetyo, R. A. Susidarti, and M. Nursid, “Chemical composition diversity of fucoidans isolated from three tropical brown seaweeds (Phaeophyceae) species,” Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers., 2020, vol. 21, no. 7.

- B. Sadeghi, M. Mohammadzadeh, and B. Babakhani, “Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Stevia rebaudiana leaf extracts: Characterization and their stability,” J. Photochem. Photobiol. B,2015 ,vol. 148, pp. 101–106.

- N. Kaur et al., “Lycium shawii mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles, characterization and assessments of their phytochemical, antioxidant, antimicrobial properties,” Inorg. Chem. Commun., vol. 2024,159, p. 111735.

- J. Huang et al., “Biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles by novel sundried Cinnamomum camphora leaf,” Nanotechnology, 2007,vol. 18, no. 10, p. 105104.

- P. Mulvaney, “Surface plasmon spectroscopy of nanosized metal particles,” Langmuir,1996, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 788–800.

- H.-G. Lee et al., “Structural characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of fucoidan isolated from Ecklonia maxima stipe,” Algae, 2022,vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 239–247.

- M. Ali Dheyab, A. Abdul Aziz, M. S. Jameel, P. Moradi Khaniabadi, and A. A. Oglat, “Rapid sonochemically-assisted synthesis of highly stable gold nanoparticles as computed tomography contrast agents,” Appl. Sci.,2020, vol. 10, no. 20, p. 7020.

- P. K. Sahoo, D. Wang, and P. Schaaf, “Tunable plasmon resonance of semi-spherical nanoporous gold nanoparticles,” Mater. Res. Express, 2014,vol. 1, no. 3, p. 035018. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Firdhouse and P. Lalitha, “Biogenic silver nanoparticles–synthesis, characterization and its potential against cancer inducing bacteria,” J. Mol. Liq.,2016, vol. 222, pp. 1041–1050.

- X. Sun et al., “Au Nanoparticles Supported on Hydrotalcite-Based MMgAlOx (M= Cu, Ni, and Co) Composite: Influence of Dopants on the Catalytic Activity for Semi-Hydrogenation of C2H2,” Catalysts,2024, vol. 14, no. 5, p. 315.

- P. Manivasagan and J. Oh, “Production of a novel fucoidanase for the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by Streptomyces sp. and its cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells,” Mar. Drugs,2015, vol. 13, no. 11, pp. 6818–6837.

- H. N. Kim and K. S. Suslick, “The effects of ultrasound on crystals: Sonocrystallization and sonofragmentation,” Crystals,2018, vol. 8, no. 7, p. 280.

- K. G. Paul, T. B. Frigo, J. Y. Groman, and E. V. Groman, “Synthesis of ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxides using reduced polysaccharides,” Bioconjug. Chem., 2004,vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 394–401.

- A. Kumar and C. K. Dixit, “Methods for characterization of nanoparticles,” in Advances in nanomedicine for the delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 43–58.

- M. A. Dheyab, A. A. Aziz, M. S. Jameel, O. A. Noqta, P. M. Khaniabadi, and B. Mehrdel, “Simple rapid stabilization method through citric acid modification for magnetite nanoparticles,” Sci. Rep., 2020,vol. 10, no. 1, p. 10793.

- S. Bagheri, H. Aghaei, M. Ghaedi, A. Asfaram, M. Monajemi, and A. A. Bazrafshan, “Synthesis of nanocomposites of iron oxide/gold (Fe3O4/Au) loaded on activated carbon and their application in water treatment by using sonochemistry: Optimization study,” Ultrason. Sonochem., 2018.vol. 41, pp. 279–287.

- M. Mahmoudi, A. Simchi, A. Milani, and P. Stroeve, “Cell toxicity of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles,” J. Colloid Interface Sci.,2009, vol. 336, no. 2, pp. 510–518.

- S. S. Agasti, A. Chompoosor, C.-C. You, P. Ghosh, C. K. Kim, and V. M. Rotello, “Photoregulated release of caged anticancer drugs from gold nanoparticles,” J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, vol. 131, no. 16, pp. 5728–5729.

- H. Sun, J. Jia, C. Jiang, and S. Zhai, “Gold nanoparticle-induced cell death and potential applications in nanomedicine,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2018,vol. 19, no. 3, p. 754. [CrossRef]

- M. Vairavel, E. Devaraj, and R. Shanmugam, “An eco-friendly synthesis of Enterococcus sp.–mediated gold nanoparticle induces cytotoxicity in human colorectal cancer cells,” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.,2020, vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 8166–8175.

- M. Kamala Priya and P. R. Iyer, “Anticancer studies of the synthesized gold nanoparticles against MCF 7 breast cancer cell lines,” Appl. Nanosci.,2015, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 443–448.

- N. Rattanata et al., “Gold nanoparticles enhance the anticancer activity of gallic acid against cholangiocarcinoma cell lines,” Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev., 2015, vol. 16, no. 16, pp. 7143–7147.

- A. A. Kajani, A.-K. Bordbar, S. H. Z. Esfahani, and A. Razmjou, “Gold nanoparticles as potent anticancer agent: green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro study,” RSC Adv., 2016,vol. 6, no. 68, pp. 63973–63983.

- J. T. Nandhini, D. Ezhilarasan, and S. Rajeshkumar, “An ecofriendly synthesized gold nanoparticles induces cytotoxicity via apoptosis in HepG2 cells,” Environ. Toxicol., 2021,vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 24–32.

- M. Islam, Y. Kusumoto, and M. A. Al-Mamun, “Cytotoxicity and cancer (HeLa) cell killing efficacy of aqueous garlic (Allium sativum) extract,” J. Sci. Res., 2011,vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 375–382.

- D. Raghunandan et al., “Anti-cancer studies of noble metal nanoparticles synthesized using different plant extracts,” Cancer Nanotechnol., 2011,vol. 2, pp. 57–65.

- M. M Hamed and L. S Abdelftah, “Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using marine Streptomyces griseus isolate (M8) and evaluating its antimicrobial and anticancer activity,” Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish., 2019,vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 173–184.

- K. M. Barakat, M. M. Ismail, H. E. Abou El Hassayeb, N. A. El Sersy, and M. E. Elshobary, “Chemical characterization and biological activities of ulvan extracted from Ulva fasciata (Chlorophyta),” Rendiconti Lincei Sci. Fis. E Nat., 2022, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 829–841. [CrossRef]

- J. Venkatesan, S. S. Murugan, and G. H. Seong, “Fucoidan-based nanoparticles: Preparations and applications,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2022,vol. 217, pp. 652–667.

- Q.-Y. Sun, H.-H. Zhou, and X.-Y. Mao, “Emerging roles of 5-lipoxygenase phosphorylation in inflammation and cell death,” Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev., 2019, vol. 2019, no. 1, p. 2749173.

- L. Y. Pang, E. A. Hurst, and D. J. Argyle, “Cyclooxygenase-2: A role in cancer stem cell survival and repopulation of cancer cells during therapy,” Stem Cells Int., 2016,vol. 2016, no. 1, p. 2048731.

- X. Yuan, C. Larsson, and D. Xu, “Mechanisms underlying the activation of TERT transcription and telomerase activity in human cancer: old actors and new players,” Oncogene, 2019,vol. 38, no. 34, pp. 6172–6183.

- E. Chu, M. A. Callender, M. P. Farrell, and J. C. Schmitz, “Thymidylate synthase inhibitors as anticancer agents: from bench to bedside,” Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol., 2003, vol. 52, pp. 80–89.

- J. Chen and X.-Y. Hu, “Inhibition of histamine receptor H3R suppresses prostate cancer growth, invasion and increases apoptosis via the AR pathway,” Oncol. Lett., 2018, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 4921–4928.

- S. Bhambri and P. C. Jha, “Targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 11: a computational approach for natural anti-cancer compound discovery,” Mol. Divers.,2025, pp. 1–17.

| Empire: Eukaryota | Empire: Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: Chromista | Kingdom: Chromista |

| Subkingdom: Harosa | Subkingdom: Harosa |

| Phylum: Ochrophyta | Phylum: Ochrophyta |

| Class: Phaeophyceae | Class: Phaeophyceae |

| Subclass: Fucophycidae | Subclass: Fucophycidae |

| Order: Fucales | Order: Fucales |

| Family: Sargassaceae | Family: Sargassaceae |

| Genus: Sargassum | Genus: Turbinaria |

| Inhibition (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrations (µ gm/ml) | Trolox | S. cinereum F-AuNPs | T. decurrens F-AuNPs |

| 3.90 | 11.73±0.21 | 10.82±0.11 | 12.05±0.41 |

| 7.81 | 25.92±039 | 21.61±0.08 | 24.07±0.36 |

| 15.60 | 47.15±0.42 | 43.23±0.13 | 39.06±0.12 |

| 25.00 | 68.64±0.15 | 66.19±0.09 | 62.49±0.31 |

| 31.25 | 83.80±0.18 | 80.49±0.19 | 78.11±0.31 |

| Inhibition (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrations (µ gm/ml) | Trolox | S. cinereum F-AuNPs | T. decurrens F-AuNPs |

| 25 | 0.09±0.17 | 0.07±0.27 | 0.07±0.30 |

| 50 | 0.15±0.28 | 0.14±0.32 | 0.14±0.11 |

| 100 | 0.34±0.16 | 0.28±0.45 | 0.28±0.17 |

| 200 | 0.65±0.08 | 0.56±0.31 | 0.57±0.12 |

| 400 | 1.40±0.15 | 1.12±0.28 | 1.14±0.19 |

| No. | Receptors | Nanoparticles | Binding affinity (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase | F-Au NAPs | -4.07 |

| 2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 | F-Au NAPs | -4.15 |

| 3 | Telomerase reverse transcriptase | F-Au NAPs | -3.98 |

| 4 | Thymidylate synthase | F-Au NAPs | -4.06 |

| 5 | Histamine H3 receptor | F-Au NAPs | -5.07 |

| 6 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinases | F-Au NAPs | -1.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).