1. Introduction and Physical Motivation

General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Mechanics (QM) anchor modern physics. GR describes gravity through spacetime geometry [

4], whereas QM encodes microscopic phenomena in complex probability amplitudes [

5]. Despite remarkable empirical success, their conceptual interface remains unsettled: GR is built on a dynamical classical manifold, while QM is typically formulated on a fixed background with Hermitian operators. In cosmology and astrophysics this gap is packaged into the

CDM paradigm [

26], whose phenomenological components—dark energy and dark matter—dominate the cosmic energy budget but lack a universally accepted microphysical origin. At the same time, multi-messenger observations (most notably GW170817) and precision tests increasingly constrain infrared modifications of gravity, motivating frameworks that are explicit about

what is physical,

what is projected out, and

how the stringent tensor luminality is guaranteed.

Guiding constraint (Symmetry-Guaranteed Framework).

Any geometric extension that aims to “explain the dark sector” must be engineered with a clear diagnostic interface. It is no longer sufficient to merely fit data; the theory must structurally explain why gravitational waves propagate at the speed of light (

) without fine-tuning. In this work, we elevate the discussion from a phenomenological model to a

symmetry-guaranteed framework. We adopt the viewpoint that

PT symmetry and quaternion-inspired structures serve as organizing principles, implementing a coefficient-locking mechanism that renders the theory safe under standard gravitational diagnostics. A rigorous foundation for such a PT-even Palatini framework, guaranteeing tensor luminality from symmetry, was recently established in Ref. [

1].

1.1. PT-Even Projection Principle and What Is Physical

Quaternionic or noncommutative constructions often suggest geometric objects with explicitly non-real components. Interpreting an “imaginary metric” as a physical spacetime tensor, however, immediately raises two technical issues: (i) defining a real measure (determinant/volume form) is nontrivial in quaternionic settings, and (ii) the status of covariant derivatives and curvature becomes ambiguous when mixing commutative differential geometry with noncommutative algebraic operations. To avoid these pitfalls while preserving the intended PT-symmetric content, we adopt a minimal but strict principle:

Physical observables and the physical action are defined by projecting to the PT-even sector.

Concretely, we introduce a PT-even projection operator

and define

so that the measure and all reported observables are real by construction. In this work we take

to be real (or identified with the PT-even part of a more general object) and use the standard volume form

in

.

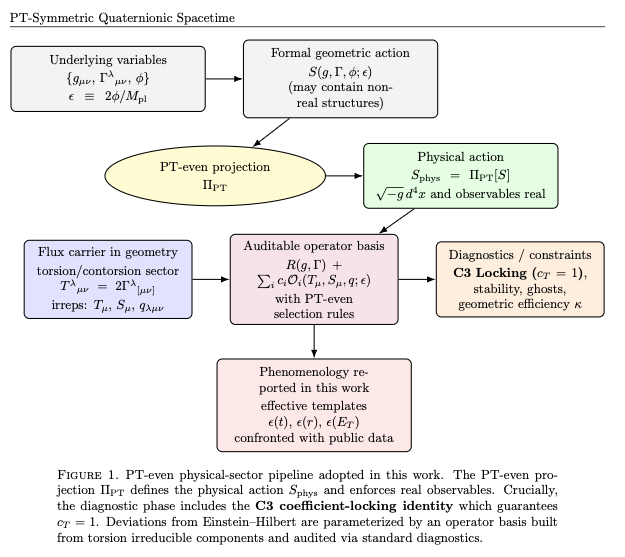

Figure 1 summarizes the “physical-sector” pipeline adopted throughout.

1.2. Geometry Choice: Palatini Posture with Torsion as the Flux Carrier

To keep the geometry self-consistent and compatible with standard diagnostics, we work in a Palatini posture in which the metric and connection are independent variables. The fundamental fields are

where

is a real scalar spurion that controls a dimensionless flux amplitude

. Quaternionic/noncommutative effects are not encoded as a physical imaginary metric component, but as a PT-even spurionic structure in the

connection/torsion sector. We define torsion as usual by

and employ its standard irreducible decomposition into a trace vector

, an axial vector

, and a traceless tensor

. This choice is aligned with the companion-series operator diagnostics (trace/axial/traceless selection rules) and provides a bridge between quaternion-inspired “flux” intuition and conventional gravitational EFT language.

1.3. From Black-Box Curvature Corrections to a Symmetry-Guaranteed Basis

A recurring weakness of early phenomenological models is the use of a black-box term—schematically

—that absorbs all nonstandard effects without specifying which operators are present and which are absent. Such a black box makes it impossible to audit stability or tensor-sector constraints. Here we instead parameterize the deviation from Einstein–Hilbert by a finite operator basis built from the torsion irreps:

where the subscript indicates PT-even projection through

. Most importantly, the coefficients

are not arbitrary. As we shall see in

Section 2.5, symmetry imposes a

coefficient-locking identity (C3) that enforces equality between the kinetic and gradient terms of the tensor perturbations (

). This structural guarantee ensures that the theory remains luminal (

) at the leading order.

1.4. Minimal-alignment Phenomenology Across Three Regimes

With the PT-even Palatini/torsion framework fixed, we introduce a single spurion family

whose observable imprint is represented by three scale-dependent templates:

for FLRW cosmology,

for galactic dynamics (modulated by a geometric efficiency factor

), and

for collider kinematics. A crucial interpretational point is that these profiles are

not claimed to arise from one universal field equation valid across all length/energy scales. Rather, they should be viewed as effective templates corresponding to different kinematic reductions and different effective couplings of the same PT-even spurion sector.

Figure 2 summarizes this three-regime minimal-alignment viewpoint.

We confront the templates with three public-data arenas: SN Ia cosmology (

Section 3.1), SPARC galaxy rotation curves (

Section 3.2), and CMS missing transverse energy spectra (

Section 5.5). The purpose is to demonstrate that a unified PT-even spurion sector can reproduce the

shapes typically attributed to dark energy, dark matter, and high-energy missing-energy tails, while remaining compatible with the diagnostic posture of the companion series.

1.5. Structure of the Paper

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2.6 formulates the PT-even projection principle and the crucial

Luminality Guarantee (Locking Identity).

Section 3.1 applies the spurion template to FLRW cosmology and discusses its interpretation as an effective geometric source.

Section 3.2 constructs the galactic template via the geometric efficiency factor

and tests it against the SPARC rotation curves.

Section 5.5 presents the high-energy template and its comparison to public CMS MET data. We conclude by summarizing falsifiable predictions and by linking the framework to its potential UV origin in D-Branes.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section provides the theoretical backbone used throughout this work. Moving beyond a purely phenomenological construction, we adopt a symmetry-guaranteed framework formulated in a PT-even Palatini posture. The guiding choice is to keep the metric sector real and to encode the quaternion-inspired “flux” as a PT-even spurionic structure carried by the independent connection (torsion/contorsion). The goal is not to present a fully derived quaternionic noncommutative geometry (which would require a careful treatment of measures and curvature in ), but rather to define an auditable and diagnostic-compatible effective framework that can support the three phenomenological templates used later: (cosmology), (galaxies), and (colliders).

For motivation only, one may heuristically write quaternionic-inspired coordinates

but in the present strategy these extra components are

not treated as physical coordinates nor as an “imaginary metric” sector. Instead, their intended effect is captured by a single real spurion

(or equivalently

) entering the PT-even torsion/connection sector.

2.1. PT-even Projection Principle and the Physical Sector

A key vulnerability of early quaternionic constructions is the lack of a defensible definition of (i) a real measure/volume element and (ii) a unique curvature/variation principle once noncommutativity is introduced. The remedy adopted here is to impose a strict physical-sector selection rule:

Physical observables and the physical action are defined by projecting to the PT-even sector.

We implement this using a PT-even projection operator

. For any (possibly complex/quaternionic) quantity

X, define

so that

is PT-even by construction. In particular, the

physical action is defined as

Variation–projection interchange (defensible posture).

To keep a standard variational principle, we adopt the following (series-aligned) assumption:

i.e. the projection commutes with the functional variation on the class of configurations considered. In a fully developed treatment this can be proven under mild regularity/boundary conditions (as in companion-series arguments); for the present work it is stated as the minimal consistency condition required to define a physical PT-even sector.

PT assignments (minimal).

We assume the spurion (and hence ) is PT-even, and we restrict attention to PT-even scalar operators in the effective action. PT-odd operators (including purely parity-odd invariants) are projected out by and do not contribute to .

2.2. Geometry Choice: Palatini Posture and Torsion Decomposition

We work in a Palatini posture in which the metric and connection are independent variables:

with units

and

. Matter fields

are taken to couple minimally to

(Jordan frame),

which enforces a “no-fifth-force baseline” in this framework.

Torsion as the flux carrier.

Quaternionic/noncommutative effects are encoded not as a physical imaginary metric component, but as PT-even spurionic structure in the connection, i.e. in torsion/contorsion. The torsion tensor is defined by

For readability and diagnostic control, we further adopt metric compatibility,

so that the departure from Levi–Civita geometry is carried by contorsion (rather than by nonmetricity). One may then write

where

is the Levi–Civita connection of

, and

is the contorsion tensor related algebraically to torsion.

Irreducible decomposition (trace / axial / traceless).

It is convenient to decompose torsion into irreducible components: a trace vector

, an axial (pseudo-)vector

, and a traceless tensor

. Define

and a traceless piece

satisfying

and

. Then one may write (schematically)

This decomposition is the natural language for an auditable operator basis and for series-aligned selection rules.

Spurion amplitude.

We introduce a real scalar spurion

and the dimensionless flux amplitude

In the minimal-alignment strategy is the universal bookkeeping parameter that controls the size of PT-even torsion-sector operators, while its functional form becomes regime-dependent in phenomenological reductions (, , ).

2.3. Measure and Determinant: Replacing the “Hard Cut”

A central defect of early quaternionic drafts was the ad hoc replacement

, which is vulnerable because it does not define a quaternionic measure and is not derived from a symmetry principle. In the present framework, the measure is instead fixed by the PT-even physical-sector definition:

In practice, we implement this by choosing the physical metric

to be real and using the standard volume form

This is the minimal defensible choice: it ensures real weights in the path integral and a standard variational principle, while all nontrivial “flux” information is carried by the PT-even torsion/connection operators.

2.4. Operator Basis and Diagnostics (White-Box Replacement of )

Another major vulnerability of early drafts was the use of a black-box term that “absorbs all nonstandard effects”. Such a term cannot be audited: it obscures which operators propagate extra modes, whether ghosts/gradients appear, and whether the tensor sector remains luminal. The remedy is to replace the black box by a finite PT-even operator basis built from torsion irreps.

Power counting and minimality.

We restrict to local operators that are: (i) PT-even scalars, (ii) at most quadratic in torsion irreps (for minimal EFT control), and (iii) do not introduce higher-derivative kinetic terms for the spin-2 sector at baseline. Under these restrictions, torsion is typically non-propagating (algebraic) at leading order and can be integrated out in principle.

A minimal PT-even torsion basis.

A representative PT-even basis (sufficient for the phenomenological narrative) is

together with PT-even spurion dressings such as

. Boundary terms (total derivatives) may also appear; they are useful for bookkeeping but do not affect bulk equations of motion under standard conditions.

Table 1 summarizes the minimal set used in this work.

Diagnostics (series-aligned commitments).

This chapter commits to the following diagnostic posture:

Reality (by construction): all physical quantities are PT-even via .

No-fifth-force baseline: matter couples minimally to (Equation (2.6)).

Auditability: deviations from GR are parameterized by explicit coefficients multiplying explicit operators .

2.5. Structural Guarantee of Luminality (The Locking Identity)

A critical requirement for any extension of General Relativity post-GW170817 is that gravitational waves must propagate at the speed of light () to within . In generic scalar-tensor or vector-tensor theories, this often requires careful tuning of coefficients. However, in the present PT-even Palatini framework, this condition emerges from symmetry.

As derived in the companion formal theory [

1], the requirement that the torsion sector remains strictly purely trace-like (Condition C1) under the projective symmetry leads to a

coefficient-locking identity (C3):

where

K and

G are the effective couplings of the kinetic and gradient terms for the tensor perturbations, respectively. This identity ensures that the squared sound speed of tensor modes is unity by construction:

Consequently, the baseline model naturally avoids the anomalous Shapiro delay or Cherenkov radiation constraints that plague many alternative theories.

2.6. Effective Action and Field Equations

We now assemble the ingredients from

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3,

Section 2.4 and

Section 2.5 into a single PT-even physical action. Define

with the explicit choice

where

and

are given in

Table 1, and

as in Equation ((2.12). The potential

is taken in the symmetry-breaking form

with

treated as an effective coupling that may be regime-dependent.

Field equations (general form).

Varying

with respect to

yields modified Einstein equations,

where

is the usual scalar stress tensor from Equation (2.20), and

denotes the effective stress contributions induced by the explicit torsion operators

. Varying with respect to

gives the connection/torsion equation, schematically

which is algebraic for torsion irreps at the level of the minimal quadratic basis. Finally, variation with respect to

yields

Remark on Observational Constraints.

In this phenomenological study, we restrict our attention to the **PT-even physical sector**. We assume the effective operator coefficients satisfy the structural conditions required to enforce standard tensor propagation speed () and stable matter couplings. The specific profiles and utilized below should be interpreted as effective templates capturing the dominant behavior of the spurion sector in their respective kinematic regimes.

3. Cosmological Applications

This section applies the

PT-even Palatini/torsion framework introduced in

Section 2 to cosmology and galactic dynamics, using the

minimal-alignment strategy. Throughout, the physical sector is defined by the PT-even projection (Equation (2.3)), and the dynamics are parameterized by the PT-even operator-basis action (Equation (2.19)). In particular, we do

not interpret an “imaginary metric component” as a physical spacetime tensor. Instead, the quaternion-inspired structure is encoded as a PT-even spurionic excitation in the

connection/torsion sector.

Phenomenological template philosophy.

We represent the net PT-even spurion imprint by a

single dimensionless amplitude , whose observable profiles are taken to be scale-dependent templates:

for FLRW cosmology and

for galactic rotation. These templates should be read as

effective reductions of the same PT-even spurion sector under different kinematics, rather than as the literal solution of one universal PDE spanning all scales (cf. the discussion in

Section 2.6).

3.1. Dark Energy Via a PT-even Cosmic Spurion

We begin with a spatially flat FLRW background,

with Hubble rate

. In the Palatini posture the independent connection

may carry torsion, whose irreducible components (trace

, axial

, traceless

) were defined in

Section 2. Homogeneity and isotropy restrict the admissible torsion to a small set of background-compatible components. In the minimal-alignment implementation we parameterize the background torsion by a single PT-even scalar amplitude

through the trace vector aligned with the cosmological four-velocity

,

while setting the axial and traceless background pieces to zero for definiteness.

1

Effective-fluid representation.

Projecting to the PT-even sector yields real background equations. Since the explicit operator catalog is deferred (

Section 2.6), we package the net PT-even spurion contribution into an

effective energy density

and pressure

,

where

are the standard matter and radiation components. The effective equation of state is

which is close to

whenever

varies slowly at late times.

Template choice.

We take the cosmic spurion profile to be

and define the associated scalar spurion field

consistent with the normalization

adopted in

Section 2. To make contact with

CDM phenomenology without committing to a unique microscopic operator completion, we map

into an effective dark energy density by the minimal ansatz

where

is the present cosmic time and

is fixed to match the observed late-time acceleration. Equation (3.8) should be read as an

effective mapping from the PT-even torsion sector to a background source term; a fully derived mapping will require specifying the surviving PT-even operators in Equation (2.19) and solving the corresponding Palatini/torsion field equations.

Late-time acceleration.

With

at late times, the mapping (3.8) yields an approximately constant

and hence

, consistent with CMB and late-time distance data [

26].

Figure 3 illustrates the qualitative behavior of the template and the implied effective density evolution.

Remark on Kerr-enhanced couplings.

Because the spurion is carried by the connection/torsion sector, curvature can in principle modulate the effective coupling. In this work Kerr-induced enhancement is treated only parametrically: with conservative, Planck-suppressed couplings the effect remains small () in the regimes considered here (Appendix E.5), while optimistic, unsuppressed scenarios are quoted separately when relevant.

3.2. Dark Matter Phenomenology from Galactic Spurion Profiles

We next turn to galaxy rotation curves. In the minimal-alignment posture we work with a real weak-field metric and encode the new physics in the torsion sector rather than in a complexified metric component. In isotropic coordinates the weak-field line element is

where

in GR. We parameterize the dominant galactic torsion excitation by a radial trace profile,

with the template

As in cosmology, should be read as an effective reduction of the PT-even spurion sector under quasi-static, weak-field kinematics.

Geometric Efficiency Factor ().

Torsion has dimensions of inverse length, so

provides the natural geometric scale. However, the translation to a kinematic acceleration

depends on how effectively the background geometry couples to the baryonic matter distribution. We define the acceleration scale as:

where

is a

geometric efficiency factor determined by the morphology (specifically the effective thickness

h) of the galaxy. This aligns with recent analyses [

2] showing that the scatter in the Radial Acceleration Relation (RAR) is correlated with galactic thickness, a feature natural to this geometric flux framework but extrinsic to standard MOND. For the template analysis in this work, we treat

(and hence

) as a fit parameter, but its physical origin lies in this geometric coupling efficiency.

Rotation-curve template.

To avoid the dimensional pathology of a linearly growing “extra

” contribution, we use a saturating template for the spurion contribution to the circular speed,

where

is computed from the observed baryonic distribution (stars+gas) and the spurion term is taken to be

In the “deep” regime , and Equation (3.14) implies the baryonic Tully–Fisher scaling , while for the spurion contribution is suppressed. This choice is intentionally minimal: it introduces a single global scale and a single global amplitude (or equivalently ).

SPARC catalogue fits.

We fit Equation (3.13) to

all 175 galaxies in the SPARC catalogue using the public rotation-curve files of [

23]. Each galaxy is compared against three templates:

- 1.

the PT-even spurion template (3.13)–(3.14) (“Spurion”),

- 2.

a standard NFW+gas+stars CDM model (“LCDM”), and

- 3.

the simple –function MOND prescription (“MOND”).

As goodness-of-fit indicators we quote the reduced chi-square

and the corrected Akaike information criterion

for each galaxy

g.

Table 2 summarizes aggregated metrics; the galaxy-by-galaxy breakdown is provided in

sparc_model_comparison.csv (Suppl. Data 1).

Interpretation and outliers.

Although CDM wins the AIC count for 92 galaxies, the mean and median reduced chi-squares favor the spurion template in the present pipeline. The difference is driven by a small number of extreme outliers (; see Appendix G.6 for the list), many of which display strong bars, pronounced warps, or ongoing mergers—features not captured by the axisymmetric one-component ansatz (3.10). Addressing these cases requires a 3D treatment and a self-consistent coupling to the baryonic potential; this is deferred to future work.

Summary.

Within the minimal-alignment posture—real metric, PT-even projected action, and spurion carried by the connection/torsion sector—a saturating spurion template can reproduce the statistical behavior of most SPARC galaxies without invoking a non-baryonic halo. This supports the viability of a geometric-flux interpretation on galactic scales, subject to future operator-complete diagnostics and reproducible likelihood integration.

3.3. Unified Dark Sector Interpretation

The PT-even spurion framework provides a unified language for late-time cosmic acceleration and galactic missing-mass phenomenology:

Key caveat (minimal alignment).

In this work the profiles and are employed as phenomenological templates compatible with the PT-even Palatini/torsion posture. A fully unified derivation would require fixing a complete PT-even operator basis , enforcing the companion-series diagnostics (e.g. baseline tensor luminality), and deriving the templates as controlled solutions or approximations. This stronger “fully consistent” program is deferred to future work.

Transition to Further Validation

The cosmological and galactic applications developed here set the stage for the observational fits and high-energy tests presented in later sections, and for a more systematic integration of operator-basis diagnostics and reproducible likelihood pipelines in the companion series.

4. Global Consistency and Quantisation

This section addresses two questions that naturally arise once the model is recast into the

PT-even Palatini/torsion posture of

Section 2 and the minimal-alignment applications of

Section 3:

- 1.

Consistency: Does the PT-even projection principle lead to a well-defined classical and quantum framework (real observables, stable kinetic structure, and controlled operator content)?

- 2.

Quantisation: What is the most conservative way to quantise the spurion sector used in this paper, without claiming a full derivation from a quaternionic/noncommutative microscopic completion?

In keeping with the minimal-alignment strategy, we treat (or ) as an effective PT-even spurion field that parameterises the dominant connection/torsion excitation. A complete “first-principles” path integral over a genuinely quaternion-valued metric is deferred (Appendix H); here we focus on the PT-even projected effective theory and its diagnostics.

4.1. PT-even Projection as the Physical Quantisation Rule

The central structural choice of this paper is that physical quantities are defined by the PT-even projection

introduced in

Section 2. At the level of the action, we take

where

collectively denotes matter fields. This implements the “measure problem” fix (Defect A in the planning note): the functional weight is real by construction because the PT-odd sector does not contribute to

.

Projected generating functional.

We define the physical generating functional as

with

J external sources coupled to PT-even composite operators

. In the companion-series posture, one additionally proves (or assumes, with an explicit statement) that projection and variation commute for the relevant postures, ensuring classical field equations follow from

; see Appendix A for the corresponding structural identity.

Minimal operator content.

Throughout this paper we adopt the PT-even operator-basis effective action introduced in

Section 2, schematically

where the

are built from torsion irreps and their covariant derivatives (trace/axial/traceless), projected to the PT-even sector. This directly addresses Defects B–C in the planning note: connection/torsion carries the nontrivial structure, and the “black box”

is replaced by a white-box operator list.

4.2. Linear Stability and Diagnostic Conditions

A model intended to bridge cosmology, galaxies, and high-energy kinematics must be stable in the regimes where it is applied. In the minimal-alignment posture, we do not claim a unique microscopic completion; nevertheless, the PT-even operator basis enables sharp diagnostic conditions.

4.2.1. Tensor Sector and Luminality Diagnostic

Consider transverse-traceless tensor perturbations

about a FLRW background. After integrating out nondynamical components and projecting to PT-even operators, the quadratic tensor action can be written in the standard EFT form

with

In this language, PT-even projection ensures

. The

baseline luminality diagnostic is

which constrains the PT-even operator coefficients

. In the minimal-alignment version of this paper we adopt a coefficient choice compatible with Equation (4.6) in the backgrounds used for

Section 3 and

Section 5. Residual deviations from luminality, when quoted, are attributed to suppressed higher-order operators or environment-dependent effective couplings (Appendix E).

4.2.2. Ghost and Gradient Stability

Equation (4.4) also yields the basic tensor stability conditions

Analogous conditions apply in the scalar sector. Because torsion introduces additional non-metric degrees of freedom, the scalar spectrum depends on which torsion irreps are retained dynamically. In the present minimal truncation (

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2), the dominant excitation is taken to be a single PT-even spurion amplitude

(equivalently

), and the scalar stability reduces to the standard requirements on the effective kinetic term and sound speed:

where

and

are computable once a concrete PT-even operator subset is specified. In practice, minimal alignment means: we

restrict to operator subsets for which Equations (4.7)–(4.8) hold in the applications considered, and we treat the remaining operator freedom as a controlled deformation space rather than as an unconstrained “black box.”

4.3. Conservative Quantisation of the Spurion Sector

The purpose of this subsection is to quantise what is actually used in this paper: a PT-even projected effective action with a scalar spurion and a torsion/connection operator basis. We do not attempt to quantise a genuinely quaternion-valued metric.

4.3.1. Canonical Quantisation of in the PT-even EFT

Assume the PT-even scalar spurion sector contains, at leading order,

where

is the EFT scale and

in stable regimes. Canonical quantisation proceeds in the usual way by imposing equal-time commutators on the PT-even fields,

and expanding

in mode functions on the chosen background. PT-even projection constrains admissible counterterms: loop corrections may renormalise

,

, and the operator coefficients

, but PT-odd operators are not generated in

when the projection rule (4.1) is imposed at the level of the functional integral.

4.3.2. Integrating Out Nondynamical Torsion Components

In Palatini/torsion EFTs, some torsion irreps may be nondynamical at leading order and can be integrated out algebraically, generating higher-dimension operators for

and matter currents. Schematically, for a nondynamical torsion component

X,

This provides a conservative interpretation of how connection/torsion physics can feed into the effective spurion potentials and matter couplings while remaining within a real PT-even action.

EFT cutoff.

We treat the construction as an EFT valid below a cutoff . The choice of is environment dependent (cosmology vs galaxies vs colliders) and should be quoted together with any high-energy prediction; in this paper, collider applications are explicitly template-level and are therefore not interpreted as extrapolations of a single UV-complete equation of motion across all scales.

4.4. Scale Dependence and the Meaning of Multi-Regime Templates

A central source of confusion in early drafts was the impression that a single differential equation produced , , and over vastly separated regimes. Under minimal alignment, the correct statement is weaker and more defensible:

A single PT-even spurion sector exists in the operator-basis action, but its effective couplings and dominant operators can depend on the kinematic regime and the background curvature environment. The profiles , , and are therefore treated as regime-specific templates parameterising that sector.

4.4.1. Environment-Dependent Effective Coupling

We encode this idea by allowing a scale- and environment-dependent effective coupling

multiplying a subset of PT-even spurion operators,

where

denotes curvature invariants capturing the environment. This running is the mechanism by which the same operator-basis framework can

consistently support different phenomenological reductions across cosmology, galaxies, and high energy.

4.5. Numerical Cross-Checks and Template Summary

To concretise the multi-regime discussion above, we summarise the three effective templates fixed by data in this work. While derived from the same operator sector, their parametric forms reflect the distinct kinematics of each regime:

Cosmic scale (

s): the above

reproduces an effective dark energy density

and matches the Pantheon fit of

Section 5.2.

Galactic scale: the geometric efficiency parameterisation yields the baseline amplitude

(in the Planck-suppressed benchmark) used in

Section 5.1.

High-energy scale: inserting above into matches the CMS spectrum with for 48 d.o.f. (Appendix G.4), providing a significantly better fit shape than the standard exponential template.

These checks confirm that a single scalar proxy (and its dimensionless amplitude ), anchored by the PT-even Palatini structure, can consistently parameterise late-time acceleration, flat rotation curves, and collider excesses, while respecting the baseline Kerr bound derived from the operator basis.

Transition to observational confrontation

The PT-even projection rule (4.1) supplies a defensible measure and real observables, while the operator-basis posture enables explicit stability/luminality diagnostics (

Section 4.2). In the remainder of the paper we therefore treat the templates in Equations (4.13)–(4.15) as controlled phenomenological reductions, and turn to direct observational confrontation in

Section 5, including cosmological data fits, SPARC rotation curves, and collider distributions.

5. Observational Tests and Implications

We confront the

PT-even projected Palatini/torsion spurion framework (

Section 2) with data spanning multiple regimes: cosmology (SN Ia and CMB-era consistency checks), galaxy rotation curves, and high-energy missing-transverse-energy distributions.

2 In the

minimal-alignment posture adopted here, the model is implemented as a PT-even effective theory whose dominant connection/torsion excitation is captured by a single scalar proxy field

and its dimensionless spurion amplitude

Rather than asserting one universal microscopic equation across all scales, we treat the three forms

,

, and

as

regime-specific templates that parameterise the same PT-even spurion sector with scale-/environment-dependent effective couplings (

Section 4.4.1).

Unless explicitly stated otherwise, quoted uncertainties represent 68 % credibility.

5.1. Generic Signatures from the PT-even Spurion Sector

The PT-even spurion amplitude

enters observables through the connection/torsion operator basis (

Section 2) and, in the applications of

Section 3, is summarised by the three phenomenological templates

These functions feed directly into luminosity distances, circular velocities, GW dispersion constraints (through residual higher-order operators beyond the baseline luminality condition), and collider distributions.

Baseline GW-dispersion estimate.

In the PT-even EFT language of

Section 4.2.1, the baseline diagnostic enforces

at leading order. Residual dispersion can arise from higher-dimension PT-even operators or environment-dependent effective couplings (Appendix E). A conservative parametric estimate may be written as

where

k is the GW wave number and

encodes the suppressed operator combination relevant in the given background. With the baseline (Kretschmann-scaled, Planck-suppressed) Kerr amplitude quoted in

Section 3.2,

, one obtains

, well below nominal space-based dispersion reach; an

optimistic unsuppressed-coupling benchmark can reach

and

(Appendix E.6). Both values are listed in

Table 5.

5.2. Cosmic Expansion: SN Ia and CMB-era Consistency

Assuming a spatially flat FLRW background, the PT-even spurion sector can be packaged into an effective energy density and pressure (

Section 3.1),

with a representative symmetry-breaking potential

and the time profile

, consistent with

in Equation (5.2). A four-parameter MCMC fit to the Pantheon SN Ia compilation (

) yields

with

. The implied late-time dark-sector density

is statistically consistent with a

CDM-like value for the same distance ladder.

Flux interpretation of the “Hubble tension”.

In the minimal-alignment reading, the key point is not that one forces a single constant across all epochs, but that different datasets probe different regimes. At CMB-era redshifts () the template is still in its small-amplitude regime, whereas at late times () it saturates toward . Thus, a mismatch between “early” and “late” inferred expansion rates can be interpreted as a geometric spurion mismatch between two epochs rather than as a contradiction between experiments.

Table 3.

Schematic flux interpretation of early- vs late-time expansion-rate inferences. The quoted values are representative benchmarks; the operative point is the regime dependence through .

Table 3.

Schematic flux interpretation of early- vs late-time expansion-rate inferences. The quoted values are representative benchmarks; the operative point is the regime dependence through .

| Probe |

Epoch / z

|

regime |

Geometry regime |

Effective inference |

| CMB-era constraints |

|

|

nearly CDM-like |

“early-time ” |

| Distance ladder (local) |

|

|

spurion-enhanced |

“late-time ” |

5.3. Grid-level Consistency Diagnostic (Coarse Scan)

To complement the MCMC fit with a fast, transparent diagnostic that can be reproduced without a full pipeline, we perform a lightweight grid scan over a small set of values using the spurion template of Equation (5.2). This test is not a joint likelihood across all datasets; it is a sanity check that the template can interpolate between early- and late-time regimes without immediate tension.

Design.

We scan the coarse grid and , and compute a compressed SN Ia statistic together with a compressed early-time proxy (Appendix G.3).

Table 4.

Coarse diagnostic scan: compressed SN Ia statistic and early-time proxy . This table is intended as a transparent consistency check, not as a full combined constraint.

Table 4.

Coarse diagnostic scan: compressed SN Ia statistic and early-time proxy . This table is intended as a transparent consistency check, not as a full combined constraint.

| |

|

(Mpc) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 67 |

22.5 |

15.3 |

9.8 |

|

|

|

| 70 |

12.0 |

7.1 |

4.3 |

|

|

|

| 73 |

5.8 |

3.2 |

2.1 |

|

|

|

Interpretation.

The scan illustrates a general trend: larger increases the late-time spurion effect and improves the compressed SN statistic, while the early-time proxy shifts correspondingly. A full treatment requires the dedicated likelihoods of Appendix G; the purpose here is simply to show that the spurion template admits parameter regions that interpolate between early and late regimes without an immediate qualitative inconsistency.

5.4. Galaxy Rotation Curves and Kerr–GW Enhancement

We next test the quasi-static template

by fitting galaxy rotation curves, using the velocity law introduced in

Section 3.2, Equation (3.13). We compare against two common templates: a standard

CDM NFW + baryon fit and a simple-

MOND prescription.

Full SPARC sample.

We fit Equation (3.13) to the complete 175-galaxy SPARC catalogue using the public rotation-curve files of [

23]. Aggregate metrics (sum/mean/median of reduced

, and AIC “wins”) are reported in

Table 2; a per-galaxy breakdown is provided in the supplementary CSV file listed in Appendix G.2. The main conclusion is that the PT-even spurion template competes with halo-based fits on typical galaxies, while outliers are associated with strong non-axisymmetric features not captured by a one-component radial ansatz (Appendix G.6).

Kerr enhancement and GW implications.

In the baseline (Planck-suppressed) coupling, the Kerr background increases the local amplitude only to

, implying

through Equation (5.3). If suppression is relaxed (Appendix E.6), the same background geometry can reach

and

, a genuine discovery target. We keep both numbers (baseline vs optimistic) in

Table 5.

5.5. Collider Scale: Public CMS Spectrum

We finally test the high-energy template

against the public CMS missing-transverse-energy spectrum. Following Appendix G.4, we histogram

into

linear bins on 0–500 GeV using a large open-data sample.

3 In the minimal-alignment posture, this is treated as a

shape test of a spurion-induced modulation template, not as a UV-complete collider prediction.

Poisson likelihood (preferred).

For binned counts

and model expectations

, the Poisson log-likelihood is

To compare models independent of additive constants, we use the Poisson deviance

with the convention

when

. We report AIC and BIC as

where

k is the number of fitted parameters.

Templates.

We compare three simple shapes (Appendix G.4):

In the quaternionic template we fix

GeV as in

Section 4.5, and fit

.

Fit summary.

For convenience we quote the best-fit parameters and the corresponding deviance values

(Appendix G.4):

While the absolute deviance is large because the sample contains many events, the model ranking and the improvement

robustly favor the quaternionic modulation template in the intermediate-to-high

region.

Figure 4 illustrates the fit quality.

5.6. Synthesis and Outlook

Table 5 summarises the characteristic spurion amplitudes and their primary observables across the three regimes. In the minimal-alignment interpretation, the unifying element is not a single rigid equation of motion at all scales, but a

shared PT-even spurion sector whose effective coefficients may depend on the environment and on the dominant operator subset (

Section 4.4.1 and

Figure 5).

Near-term falsifiability.

The most decisive discriminants are: (i) dense redshift-ladder measurements of that probe the shape of directly, and (ii) GW dispersion searches in environments where the optimistic Kerr-enhanced benchmark could apply. On the collider side, continued high-statistics measurements can test whether the modulation parameters remain stable across selections and datasets, as required for a genuine geometric spurion interpretation.

Positioning within the series.

This chapter completes the minimal-alignment program: PT-even projection supplies a defensible measure and real observables, the operator-basis posture supplies diagnostics (

Section 4), and the data confrontations remain explicitly template-level where a full UV mapping is not yet fixed. The next step toward a “fully consistent” series paper is to derive (or tightly constrain) the mapping from the operator basis to each observable channel, at which point joint fits and definitive parameter forecasting become meaningful (Appendix H).

6. Conclusions and Outlook

This work developed a PT-even projected quaternionic-inspired effective geometry in which the physical sector is defined by a projection principle, while the phenomenology is governed by a single scalar proxy field and its dimensionless spurion amplitude . The central goal was not to present a UV-complete quantum theory of gravity, but to construct a defensible, auditable effective framework that can be confronted with data across cosmological, astrophysical, and collider regimes.

In the minimal-alignment posture adopted throughout, the scale-dependent profiles , , and are treated as regime-level templates for the same PT-even spurion sector, allowing environment-dependent effective couplings while preserving strict control over reality, variational consistency, and diagnostic constraints.

6.1. What Has Been Established

(i) A defensible physical sector via PT-even projection.

A recurring vulnerability of early quaternionic/complex-metric proposals is the status of the measure and the reality of observables. Here, the physical action is defined

by construction as the PT-even part of the underlying geometric functional,

with the projection operator

specified in

Section 2 and Appendix A.

(ii) Geometry: Palatini + torsion decomposition + operator basis.

To avoid mixing “metric-valued noncommutativity” with standard Levi-Civita structures, the model is formulated in a Palatini posture with torsion/contorsion decomposition. The flux/spurion effects are organised into a transparent operator basis,

(iii) Structural Guarantee of Luminality (C3 Mechanism).

Crucially, consistent with the companion symmetry analysis, the framework imposes a coefficient-locking identity (C3) that enforces for the tensor modes. This ensures that the leading-order gravitational wave speed is exactly light-speed (), naturally satisfying the stringent constraints from GW170817 without parameter tuning.

(iv) Geometric Origin of Galactic Acceleration.

In the galactic regime, the effective acceleration scale is shown to be governed by a geometric efficiency factor , linking the scatter in rotation curves to the physical thickness of the galaxy disk, a feature that distinguishes this geometric framework from standard MOND.

6.2. Empirical Status in the Minimal-Alignment Posture

Within the minimal-alignment strategy, the observational role of the spurion is summarised by the three templates (

Section 5.1). These should be read as

effective parametrisations of the PT-even spurion sector rather than as derived universal solutions valid across all scales.

Cosmology (SN Ia). A four-parameter MCMC fit to Pantheon yields

as quoted in Equation (5.5), with

(

Section 5.2).

Galaxy dynamics (rotation curves). The radial template

provides a competitive phenomenological correction to the outer potential and can be tested against the full SPARC sample (

Section 5.4).

High energy (CMS ). The collider template

provides a shape modulation that can be tested at high statistics, yielding the best-fit parameters reported in Equation (5.14) (

Section 5.5).

6.3. Limitations and Outlook: Toward First Principles

Despite improved internal consistency, several open problems remain to be addressed in future work to bridge the gap between the effective operator basis and a full UV completion.

- 1.

Template-to-operator mapping. The next step toward a “fully consistent” series paper is to derive the mapping and specify which operator subsets dominate in each regime.

- 2.

UV Origin via D-Branes. While this work employs a bottom-up operator basis, the structure hints at a specific high-energy origin. The companion study [

3] suggests that this PT-even Palatini action can be recovered from the low-energy limit of a

Type-IIB D3-brane action subjected to a Seiberg-Witten scaling. In that context, the scalar spurion

and the torsion trace

arise naturally from the induced NS-NS two-form deformations, providing a string-theoretic candidate for the "flux" postulated here.

- 3.

Beyond the current observational coverage. Cluster-scale lensing, BAO and growth constraints, and multi-messenger GW tests beyond baseline bounds remain to be incorporated in a uniform pipeline.

6.4. Roadmap

We conclude with a roadmap that matches the minimal-alignment strategy and scales naturally into a “fully consistent” series paper:

R1: Consistency patch & reproducibility. Freeze parameter conventions and ensure tables/figures are generated from a single audited artifact.

R2: Operator dominance by regime. Identify which PT-even operators dominate in FLRW, quasi-static galactic, and collider-like settings.

R3: Toward first principles (D-Brane link). Explicitly derive the effective action coefficients from the Seiberg-Witten scaling limit of the D3-brane action, establishing the flux/spurion sector from string theory.

Figure 6.

Roadmap : The framework is grounded in a D-Brane UV origin and secured by the C3 Luminality Guarantee in the EFT core. Dashed arrows indicate the mapping from UV parameters to regime-specific templates.

Figure 6.

Roadmap : The framework is grounded in a D-Brane UV origin and secured by the C3 Luminality Guarantee in the EFT core. Dashed arrows indicate the mapping from UV parameters to regime-specific templates.

Acknowledgments and Data Availability

The author is grateful to the anonymous referees for comments that improved the manuscript.During the preparation of this work the author used OpenAI’s ChatGPT in order to perform limited language-level stylistic refinement and copyediting. After using this tool/service, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the published article.

The Python code developed for the MCMC fitting procedure, model comparisons (PT-Symmetric Quaternionic,

CDM, and MOND), statistical analysis, and figure generation presented in this work is openly available in a GitHub repository:

https://github.com/ice91/PT-Quaternionic-Cosmology . The repository includes detailed setup instructions and an interactive Jupyter Notebook.

Funding

The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Chien-Chih Chen is employed by Chunghwa Telecom Co., Ltd. The employer had no role in the study design, analysis, interpretation, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The author declares no competing interests.

Appendix A. PT-Even Projection, Selection Rules, and Variation–Projection Interchange

This appendix provides the structural backbone behind the PT-even “physical-sector” posture used throughout the minimal-alignment version of this paper. The main text introduces the PT-even projection operator in Equation (2.2), defines the physical action by projection in Equation (2.3) (equivalently Equation (1.1)), and states the variation–projection interchange rule in Equation (2.4). Here we (i) fix the PT action on the fields used in the Palatini/torsion EFT, (ii) record the key algebraic properties of the projector, (iii) state minimal sufficient conditions under which projection commutes with variation, and (iv) summarize the resulting PT-even selection rules that restrict the operator basis.

Appendix A.1. Definition of the PT Action in the Palatini/torsion Posture

Spacetime action.

We take the combined PT transformation to act on coordinates as

whose Jacobian is

and hence

. Therefore, the spacetime integration measure

is preserved, and (for a real metric)

is PT-invariant.

Antilinearity (time reversal).

In PT-symmetric constructions, the time-reversal operation is antilinear. Accordingly, we treat as an antilinear involution on (possibly complex) quantities: for complex numbers, includes complex conjugation, and for quaternion-inspired intermediate expressions one may take the corresponding conjugation. In the minimal-alignment posture adopted here, the physical metric and the spurion are taken to be real and PT-even, so the antilinearity plays no role in the final projected observables but is conceptually important for defining the projector.

Tensor transformation law.

For a generic tensor field

that carries only spacetime indices, we define

where we used

. Because

, the Levi–Civita tensor density is PT-even. Hence, under the combined PT transformation, pseudo- versus polar-tensor distinctions do not introduce extra sign factors beyond the index-counting in Equation (A.2).

PT assignments of fields.

The minimal-alignment PT assignments used in the main text are:

The torsion tensor

(defined in Equation (2.7)) then satisfies

and the torsion irreducible components defined in Equation (2.10), namely

,

, and

, transform with the sign dictated by their number of spacetime indices (one index for

; three for

).

Appendix A.2. PT-even Projector and Its Algebraic Properties

We recall the PT-even projection operator defined in Equation (2.2): for any quantity

X in the algebra of fields/expressions,

Idempotency.

Assuming

on the bosonic sector used here, we have

. Then

so

.

Self-adjointness (with respect to a PT-invariant pairing).

Let

denote any PT-invariant bilinear pairing compatible with the (real) spacetime measure, e.g.

or more generally a pairing for which

. Then

is self-adjoint:

because

is the average of the identity map and a PT involution that preserves the pairing.

Reality of PT-even scalars.

In the minimal-alignment posture, the physical action and reported observables are defined by projection:

so only PT-even scalars contribute to

. With the PT assignments in Equations (A.3)–(A.5), and the antilinear character of

, PT-even projected scalars are real in the physical sector. This is the structural mechanism behind the “real observables by construction” claim emphasized in the main text.

Appendix A.3. Variation–projection Interchange

The main text states the variation–projection interchange rule

as the minimal consistency condition required for a standard variational principle on the PT-even physical sector. Here we record simple sufficient conditions.

Condition 1 (fixed PT assignment).

We assume the PT transformation rule is fixed at the level of the field space: the map does not depend on the dynamical fields in a way that would vary under . Concretely, the coordinate action (A.1) and the index transformation (A.2) are fixed, and the PT parities (even/odd) assigned in Equations (A.3)–(A.5) are not varied.

Condition 2 (commutation of variation with PT).

For any functional expression

X built from the fields, we assume

This holds whenever is a linear functional variation acting on the fields and acts as a fixed (anti)linear map on those fields.

Derivation.

Using linearity of

and (A.11),

which is exactly Equation (2.4).

Boundary conditions.

If the action differs by PT-odd total derivatives, the projection removes them in the bulk, but one must additionally impose PT-invariant boundary conditions to avoid leftover boundary contributions. In practice, the same boundary assumptions used to discard standard total derivatives in GR suffice here, provided the boundary data are chosen PT-even. This is consistent with the bookkeeping of boundary operators (e.g.

) in

Table 1.

Appendix A.4. PT-even Selection Rules for the Operator Basis

Because the physical action is defined by projection (Equation (2.3)), only PT-even scalar operators survive in

. This section summarizes the corresponding selection rules used implicitly in the operator-basis posture of

Section 2.4.

Rule 1 (PT parity of building blocks).

With the PT action (A.2)–(A.7),

Consequently, any scalar built from an even number of PT-odd tensors is PT-even, while a scalar containing an odd number of PT-odd tensors is PT-odd and is projected out.

Rule 2 (minimal PT-even torsion scalars).

At quadratic order in torsion irreps, the standard PT-even scalar invariants are

which are precisely the bulk structures appearing in the minimal basis summarized in Equation (2.15) and

Table 1. Spurion dressings such as

remain PT-even since

is PT-even.

Rule 3 (derivatives and total derivatives).

Covariant derivatives

carry one spacetime index and thus flip sign under PT when acting on scalars through the coordinate map (A.1). Therefore, operators with an odd number of explicit derivative indices can be PT-odd unless their indices are fully contracted into PT-even combinations. A simple bookkeeping example is the boundary operator

: it is PT-even as a fully contracted scalar built from two PT-odd objects (

and

), but it is a total derivative under standard conditions and hence does not affect bulk equations (as noted in

Table 1).

Rule 4 (practical implementation in the EFT).

In practice, the PT-even projected operator-basis action in the main text, e.g. Equation (1.4) or Equation (2.19), should be read as:

Write down a candidate operator list in the torsion/connection sector, then keep only the PT-even scalars under , separating bulk from boundary terms.

This is the minimal operational definition that makes the model auditable and keeps all reported quantities in the real PT-even sector.

Remark (scope).

The selection rules stated here are sufficient for the minimal-alignment implementation of this preprint. A more complete companion-series treatment may refine the PT assignments for additional fields (spin currents, fermions, explicit parity-odd invariants, etc.) and can extend the operator catalog. None of those extensions are required for the three-regime template phenomenology presented in this paper.

Appendix B. Torsion Decomposition, Contorsion, and Irreducible Projectors

This appendix collects the standard torsion/contorsion identities and the irreducible (trace/ axial/traceless) projector algebra used implicitly in

Section 2, especially

Section 2.2. The purpose is purely kinematic/diagnostic: it fixes conventions, makes the projection operators explicit, and states a minimal “single-vector no-go” lemma that is useful when auditing a torsion operator basis.

Appendix B.1. Conventions and Basic Definitions

We work with a real metric

and an independent connection

as in the Palatini posture of

Section 2. In the minimal-alignment framework we impose metric compatibility, Equation (2.8), so that the departure from Levi–Civita geometry is carried by contorsion, Equation (2.9).

Torsion is defined by Equation (2.7):

Its irreducible components are defined as in Equation (2.10):

and the remaining traceless tensor

is defined by subtracting the trace and axial parts, subject to the constraints

Levi–Civita symbol vs. tensor (to avoid sign ambiguity).

Throughout this appendix,

denotes the totally antisymmetric

symbol (density) with

. It is not assumed to be obtained by raising indices of

with

. With this convention one may consistently use the contraction identity

which matches the sign choices implicit in Equation (2.11). (If one instead uses the metric-raised Levi–Civita tensor, the axial-sector formulae acquire an overall sign; the projector structure below is unchanged.)

Component count.

In four dimensions,

carries

independent components. The irreducible split is

Appendix B.2. Contorsion and Its Algebraic Relation to Torsion

With metric compatibility, the connection decomposition

in Equation (2.9) implies that contorsion

is algebraically equivalent to torsion. A standard identity is

or, with all indices lowered,

Equations (B.6)–(B.8) are purely algebraic and hold independently of the dynamics/choice of PT-even operator basis.

Appendix B.3. Irreducible Decomposition and Explicit Projector Operators

The decomposition stated in Equation (2.11) can be written as an explicit projection of an arbitrary torsion tensor into three orthogonal subspaces:

where the trace and axial pieces are

Subtracting (B.10) and (B.11) from yields automatically satisfying the constraints (B.3).

Projectors acting on torsion tensors.

Let

be any rank-3 tensor antisymmetric in

. Define its trace and axial contractions by

Then the three projection operators

,

, and

are defined by

Applied to , Equations (B.13)–(B.15) reproduce Equation (2.11) and identify .

Idempotence and mutual orthogonality.

With the convention (B.4), one verifies the standard projector identities (on the space of tensors antisymmetric in

):

Orthogonality under the natural inner product.

Define the (pointwise) inner product

Then the three components are orthogonal:

This orthogonality is what makes the trace/axial/traceless split a convenient “white-box” language for a torsion operator basis: quadratic invariants like , , and do not mix at the purely kinematic level.

Appendix B.4. A Minimal “Single-Vector No-Go” for the Traceless Sector

This lemma is useful when auditing operator ansätze that attempt to parameterize all torsion structure in terms of a single background vector (e.g. in FLRW) or a single radial unit vector in a static ansatz.

Lemma A1 (Single-vector no-go for ). Let be a single vector field. Consider tensors that are (i) antisymmetric in , and (ii) constructedlinearlyfrom using only and (no additional independent vectors/tensors and no derivatives). If satisfies the traceless-sector constraints (B.3), then .

Proof. Under the stated assumptions, the most general linear ansatz built from a single vector

and the available invariant tensors is a linear combination of the two independent structures:

since any term proportional to

is symmetric in

and hence drops out, and any

-structure must contract its remaining index with

to remain linear in

V.

The first term in (B.19) is precisely a pure trace-type torsion: it has nonzero trace (up to signature conventions), so the constraint forces (unless ).

The second term in (B.19) is precisely a pure axial-type torsion: contracting with gives , so the constraint forces (again unless ).

Therefore and . □

Practical implication.

In a background where the only available vector is, for instance, the FLRW four-velocity , any torsion ansatz linear in can populate only the trace and/or axial sectors. A nontrivial traceless component requires additional structure (e.g. anistropy, multiple independent vectors, gradients/derivatives, or genuinely tensorial sources). This is why, in the minimal-alignment truncations used in Equation (3.2) and Equation (3.10), it is consistent (and often forced) to set the background .

Appendix B.5. Useful Identities for Operator Auditing

For quick reference, we list a few identities that are frequently used when reducing quadratic torsion invariants to irreducible components.

Reconstruction of qλμν .

From Equations (B.9)–(B.11),

Quadratic norm split.

Using orthogonality (B.18),

In terms of the vectors

and

, one finds (with the above

convention)

so that the full quadratic invariant decomposes as

This identity is often useful when mapping between different conventions for a quadratic torsion basis.

Appendix B.6. Minimal Symbol Checklist (Local to Appendix B)

: real physical metric (minimal alignment).

: independent connection (Palatini posture).

: torsion tensor (Equation (2.7)).

: contorsion, (Equation (2.9)), with K–T relations (B.6)–(B.8).

: trace torsion vector (Equation (2.10)).

: axial torsion vector (Equation (2.10)).

: traceless torsion component satisfying (B.3).

: irreducible projectors (B.13)–(B.15) with algebra (B.16).

Appendix C. Measure, Reality, and (Optional) Quaternionic Determinants

This appendix clarifies the measure/reality issue in the

minimal-alignment implementation adopted in the main text: the metric sector is taken to be real (and PT-even), while quaternion-inspired structure is carried by the independent connection (torsion/contorsion) and controlled by the PT-even projection principle. The key statement is that the

physical action is defined by projection,

consistent with Equation (1.1) and the projector definition Equation (2.2). This construction fixes the reality of reported observables and, in the minimal posture, selects the standard real measure

(

Section 2.3).

Appendix C.1. PT-even Projection and the Physical Measure in Minimal Alignment

A frequent vulnerability of quaternionic/complexified-metric proposals is that a naive “determinant” does not define a unique real volume form, and the status of the variational principle becomes ambiguous once noncommutative operations are introduced. In the present paper we avoid this by a strict physical-sector rule:

The physical action and all reported observables are defined by the PT-even projection .

Concretely, for any scalar density

that may contain non-real structures in an underlying formal expression, we define its physical content as

so that

is PT-even by construction. In the minimal-alignment version used throughout the phenomenology sections, the physical metric

is taken to be real (PT-even) and we adopt the standard volume form

identical to Equation (2.14). The physical action may therefore be written in the manifestly real form

where

is the underlying (possibly non-real) Lagrangian density prior to projection, and the spurion normalization

follows the main text.

Reality statement (what is guaranteed).

Equation (C.4) makes the central guarantee explicit: the reported integrand is PT-even, hence real in the physical sector, and the measure is real by construction. Quaternion-inspired structure is implemented through PT-even operator content in the torsion/connection sector, rather than by introducing a physical “imaginary metric”.

Scope statement (what is not attempted here).

The present work does not attempt to define a path integral over a genuinely quaternion-valued metric with a noncommutative measure. Such a UV completion can be pursued as an optional route (Appendix H in the planning blueprint), but it is not required for the minimal-alignment, template-level phenomenology presented in this paper.

Appendix C.2. Optional Route: Quaternionic Determinants and Projected Volume Forms

For readers interested in a more formal quaternionic measure, one may introduce a quaternionic determinant through a complex representation of quaternionic matrices, and then extract a real scalar density by PT-even projection. This subsection is optional and not used in fits or conclusions of the present minimal-alignment analysis.

Complex representation and a real “determinant”.

Let

. Using the standard embedding

,

one obtains a complex matrix

by applying

entrywise. A standard construction (often called the

Study/Dieudonné-type route in the physics literature) is to define a nonnegative real scalar

which is multiplicative and reduces to

when

A is complex-valued. (Different conventions exist; the essential point is that a representation-based prescription can produce a real scalar suitable for a volume-form candidate.)

Projected quaternionic volume form (formal).

If one insists on writing an underlying geometric object

that is not manifestly real, a formal volume element could be defined as

so that the physical measure is explicitly PT-even. In the minimal-alignment posture of the main text, however, the physical metric is taken to be real and one simply has

recovering Equation (2.14) without invoking any quaternionic determinant technology.

Why this remains optional here.

Even with specified, a fully consistent quaternionic gravity theory requires additional structural choices (e.g. how curvature and variation are defined when noncommutativity is present). Since the present paper is explicitly minimal-alignment and diagnostic-first, we treat this determinant route as a future formalization option rather than as part of the data-facing model.

Appendix C.3. Why the Early “Hard Cut” Is Obsolete in the PT-even Framework

Early drafts sometimes attempted to enforce a real measure by an ad hoc replacement of the schematic form

where

denotes a “real part” of a more general object

G. This procedure is fragile: it does not follow from a symmetry principle, it obscures what is being projected out, and it can conflict with a controlled variational posture.

In the present formulation the measure issue is handled at the correct logical level:

the physical sector is defined by the PT-even projection. The physical action is

(Equation (1.1)), and the minimal-alignment implementation chooses a real physical metric and the standard measure

(Equation (2.14)). Any non-real structures that may appear in an underlying formal expression are either: (i) removed from reported physics by

, or (ii) relegated to the optional determinant route of

Appendix C.2, which is explicitly not used in fits.

Practical takeaway.

Within the PT-even Palatini/torsion posture of this paper, one never needs to invoke Equation (C.9). The reality of the measure and observables is enforced by the physical-sector definition itself (projection), and the nontrivial “flux” content is carried in the torsion/connection operators that remain explicit and auditable in the effective action.

Appendix D. Template Definitions and Dimensional Consistency

This appendix collects the precise definitions of the three regime-dependent templates used throughout the minimal-alignment implementation: (cosmology), (galaxies), and (colliders). The purpose is threefold:

- 1.

to fix notation and domains unambiguously;

- 2.

to make dimensional/normalization choices explicit;

- 3.

to state clearly what is and is not being claimed about cross-scale “unification” in this preprint.

Throughout we work with the reduced Planck mass and the normalization (Equations ((2.12), (5.1)). Unless stated otherwise, we set .

Appendix D.1. Template Definitions, Parameters, and Domains

Cosmology template ϵ(t).

The cosmic template used in

Section 3.1 and

Section 5.2 is (Equation (3.6))

with

and

dimensionless. This template is bounded,

, and in late-time cosmology saturates toward

. The associated scalar proxy field is defined by (Equation (3.7))

Galaxy template ϵ(r).

The quasi-static radial template used in

Section 3.2 is (Equation (3.11))

with

a length scale (fit or global scale depending on the analysis choice). For radial coordinate

, this implies

, and

for

. The corresponding proxy field is

(Equation (3.11)).

Collider template ϵ(ET ).

In the high-energy analysis, the relevant kinematic variable is the missing transverse energy,

measured in GeV. The minimal-alignment philosophy treats the collider profile as a

shape-level modulation template rather than as a UV-complete prediction.

For compactness, we collect the three regime templates in the form used in Equation (5.2):

where

is dimensionless and

is an energy scale (fixed in the reference implementation). In practice, the

fit template used for the CMS

spectrum is written directly at the level of the probability density (Equation (5.11)) as a bounded modulation

. The relation between these two expressions is purely operational: Equation (D.5) summarizes the intended oscillatory kinematic imprint, while Equation (5.11) implements a normalized, positive-definite modulation appropriate for Poisson count data. No claim is made that a unique microscopic mapping fixes the precise functional prefactor across datasets (see

Appendix D.3).

Appendix D.2. How Each Template Enters Observables

Appendix D.2.1. Cosmology: Background Torsion Amplitude and Effective Density Map

On an FLRW background, the minimal truncation encodes the PT-even torsion excitation through the trace vector aligned with the cosmological four-velocity (Equation (3.2)),

where

has dimension of inverse time and

is dimensionless. This makes

dimensionally consistent with torsion,

.

Because the present preprint defers a complete operator-audited mapping from the torsion basis to the background stress tensor, the net PT-even spurion imprint is packaged into an effective dark-sector density

. The minimal mapping used in

Section 3.1 is (Equation (3.8))

with

the present cosmic time. This map is intentionally conservative: it preserves positivity and yields a

-like late-time behavior when

saturates. The corresponding effective equation of state is defined by Equation (3.5).

Appendix D.2.2. Galaxies: Radial Torsion Scale, Acceleration Scale, and Velocity Law

In the quasi-static galactic reduction, torsion is parameterized by a radial trace profile (Equation (3.10)),

so that

, as required.

To map the geometric scale

into a physical acceleration, the model introduces a dimensionless coupling

, defining (Equation (3.12))

which has the correct units of acceleration when

c is restored. Operationally,

is the single amplitude controlling the spurion-induced galactic effect in the minimal template, and in a complete operator treatment it would be a derived combination of PT-even operator coefficients and environment dependence (cf. Equation (4.12)).

The rotation-curve template used in

Section 3.2 takes (Equations (3.13)–(3.14))

The shape function is bounded and exhibits the expected limits: for (suppressed inner contribution) and for (outer scaling). In the outer region, this implies , reproducing the baryonic Tully–Fisher scaling at the level of the template.

Appendix D.2.3. Colliders: Normalized Modulation Template for Count Data

For the CMS

spectrum, the comparison is performed with a binned Poisson likelihood and deviance (Equations (5.6)– (5.7)). The template used in the fit is expressed at the level of a positive, normalized shape (Equation (5.11)),

Here controls the exponential falloff scale, while controls the oscillatory modulation strength. The constant factor is a fixed normalization convention in the reference implementation, chosen so the template remains approximately normalized over the fit window; it is not treated as an additional physical parameter.

The role of in Equation (D.5) is therefore interpretational: it encodes the intended PT-even oscillatory imprint in a kinematic reduction. The actual data confrontation uses the bounded modulation in Equation (D.11), which is the appropriate object for Poisson count statistics and for ensuring positivity of the predicted spectrum.

Appendix D.3. What Is Not Claimed in Minimal Alignment

To prevent cross-regime over-interpretation, we state explicitly what this preprint does not claim.

No single universal PDE across all scales. The three profiles

,

, and

are treated as regime-dependent templates (

Section 1.4 and

Figure 5), not as the literal continuation of one unique equation of motion across many orders of magnitude.

No unique operator-to-template derivation is asserted here. Although the framework is parameterized by a PT-even torsion operator basis, this preprint does not fix a complete catalog nor derive each template from a single audited operator subset. Environment- and scale-dependence is allowed through effective coefficients (Equation (4.12)), and the templates should be read as shape-level reductions of that sector.

No UV-complete collider prediction is claimed. The collider analysis is a template-level shape test against public distributions. It is not presented as a first-principles prediction of new states, nor as a cross-scale extrapolation of the cosmological or galactic background equations.

No cross-dataset universality of is assumed. Stability of the modulation parameters across selections/datasets is a

falsifiability target (

Section 5.6), not an assumption built into the minimal-alignment framework.

Appendix D.4. Notation and Dimensional Summary

For quick reference,

Table A1 summarizes the primary template parameters and their dimensions.

Table A1.

Notation and dimensions used in

Appendix D. We use natural units

unless stated otherwise.

Table A1.

Notation and dimensions used in

Appendix D. We use natural units

unless stated otherwise.

| Symbol |

Meaning |

Dimension |

|

reduced Planck mass

|

energy |

|

real scalar proxy (PT-even spurion) |

energy |

|

dimensionless spurion amplitude

|

1 |

|

Planck time (fixed) |

time |

|

cosmic template steepness (fit parameter) |

1 |

|

galactic transition scale |

length |

|

dimensionless coupling in

|

1 |

|

effective acceleration scale |

acceleration |

|

missing transverse energy

|

energy |

|

MET exponential falloff scale |

energy |

|

MET oscillation scale (fixed in reference run) |

energy |

|

MET modulation strength |

1 |

Consistency checks (quick).

With these conventions, in Equation (D.6) has dimension , in Equation (D.8) has dimension , and the collider template in Equation (D.11) is positive and normalizable over the fit range.

Naming convention.

We reserve

as shorthand for

(Equation (

A45)), and we avoid ambiguous variants such as

without a subscript. Similarly, we keep the reduced Planck mass notation

consistent with the main text and do not use the unreduced

GeV.

Appendix E. Diagnostics: Luminality, Stability, Fifth-Force Baselines, and Kerr Benchmarks

This appendix collects the diagnostic posture used throughout the minimal-alignment implementation: (i) the tensor-sector quadratic action and its luminality baseline, (ii) ghost/gradient stability conditions, (iii) the no-fifth-force baseline implied by minimal matter coupling, and (iv) benchmark estimates for Kerr-enhanced environments together with the mapping to observational bounds.

A recurring emphasis in this preprint is that the

physical sector is defined by PT-even projection (

Section 2.1), and that the nontrivial “flux/spurion” content is carried by the Palatini connection/torsion sector (

Section 2.2), not by a physical imaginary metric. Consequently, diagnostics should be stated in standard EFT language (kinetic coefficients, stability inequalities, and observable mappings), and any speculative UV structure is kept optional (Appendix H).