1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, a member of the

Coronaviridae family and the

Betacoronavirus genus, is the etiological agent of the disease known as COVID-19. Transmission occurs from person to person through contact with respiratory secretions and contaminated surfaces. Clinical manifestations are characterized by symptoms such as fever, cough, dyspnea, headache, anosmia, ageusia, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, and muscle pain [

1].

First identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 triggered a pandemic declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020. In Brazil, the first reported case of COVID-19 occurred on February 26, 2020, in the state of São Paulo [

2], spreading rapidly across all states in the country.

As of February 18, 2025, a total of 715,026 deaths and 39,168,245 cases of the disease had been reported in Brazil [

3]. The rapid progression of COVID-19 required authorities to implement intervention measures to control the disease, such as social isolation, border closures, and an urgent search for vaccines. Numerous tests were developed to detect SARS-CoV-2, with clinical testing serving as the primary surveillance method. These tests provided essential data needed to detect, assess, notify, and report public health events, in accordance with the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR).

However, testing capacity varied greatly between countries and similarly across municipalities in Brazil, as tests were expensive and/or required complex equipment and skilled labor. Northern Minas Gerais, which, along with the Jequitinhonha vlley, has the lowest socioeconomic indicators in the state [

4], was severely affected, with more than 319,000 reported cases between January 2020 and February 2025 [

5].

In this regard, environmental surveillance, through wastewater-based epidemiology, emerged as an alternative tool for the detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2. Wastewater monitoring had already been used for the assessment of pharmaceutical compounds, detection of bacteria and illicit drugs, as well as other viruses such as Poliovirus, Norovirus, and Hepatitis A [

6]. Unlike clinical tests, wastewater surveillance has the advantage of encompassing both asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals who have not been tested, serving as a complementary strategy to clinical surveillance [

7].

In areas with limited access to public health services, the lack of clinical testing led to many underreported cases [

8]. In this way, wastewater monitoring can be especially useful for low- and middle-income countries, where financial resources such as viral and antibody testing capacity, hospital infrastructure, qualified staff, and personal protective equipment (PPE) may be limited. [

9].

The monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater was extensively explored during the pandemic, both in Brazil and worldwide, proving that the tool allows for analyzing the virus dynamics in the environment and predicting potential outbreaks through the increase in viral load [

9,

10,

11]. However, studies have mostly been conducted in large urban centers or their surroundings, and during the pandemic. Little is known about the potential for virus monitoring in small towns far from major centers, especially after the pandemic end. Therefore, the objective of this study was to monitor the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 during and after the pandemic, in wastewater from the cities of Salinas and Rubelita, located in the northern region of Minas Gerais, far from major centers and with low population density, as well as to compare the frequency and variability of detection with official data on confirmed COVID-19 cases in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Wastewater Sampling

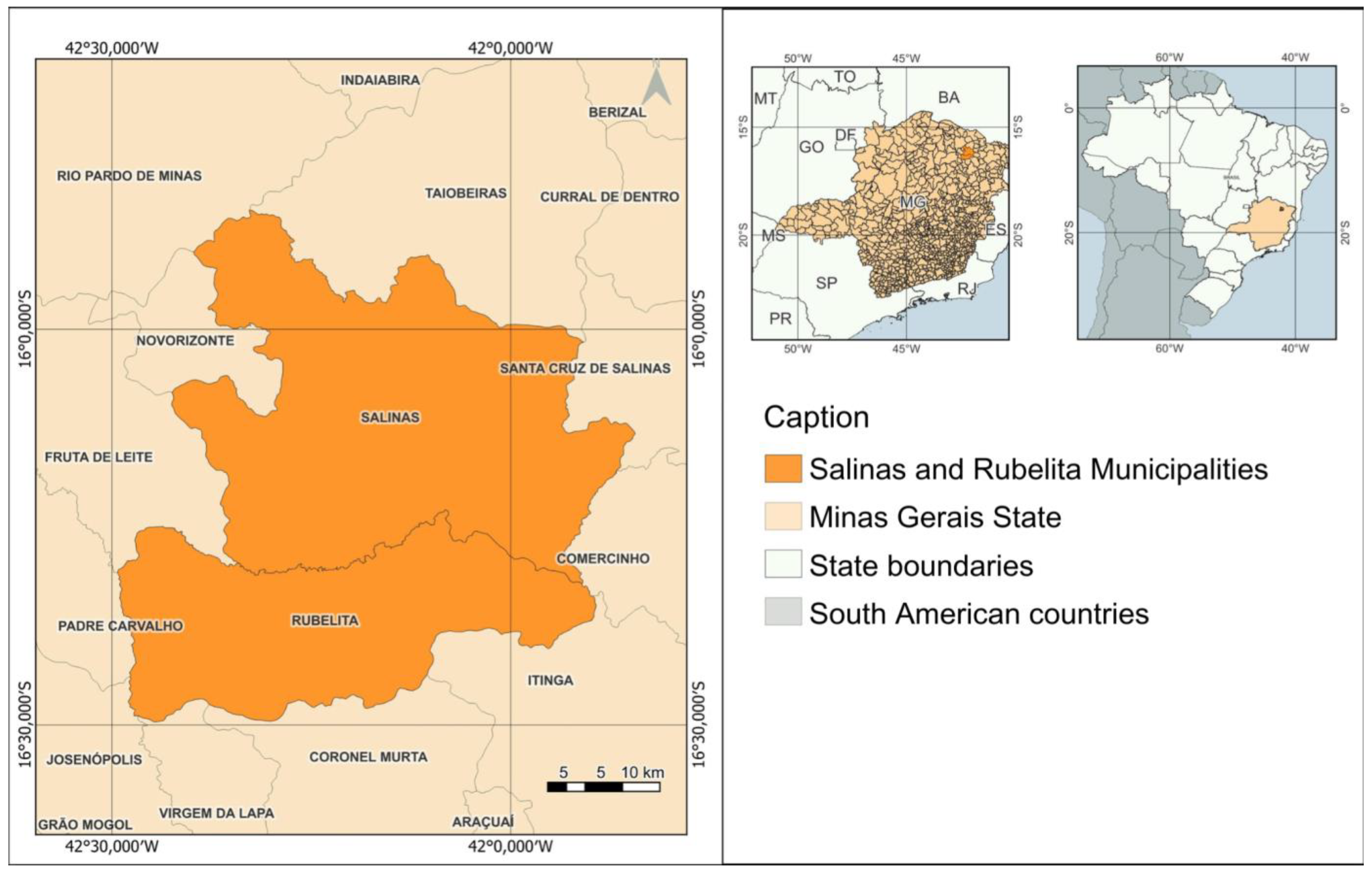

The study was conducted between February 07, 2023, and January 01, 2024, at strategic points of the raw sewage collection networks in the cities of Salinas and Rubelita, municipalities in the state of Minas Gerais (

Figure 1), located in the northern mesoregion of Minas Gerais. The city of Salinas has an estimated population of 40,178 inhabitants, with 66.15% of the population receiving sanitary assistance. The municipality of Rubelita has 5,679 inhabitants, and 25.7% of them have access to adequate sewage systems[

12].

Four sampling points were chosen based on their accessibility and the vulnerability of the population served, with three in Salinas: the Raquel neighborhood (which receives waste from the elderly home), the Instituto Federal do Norte de Minas Gerais (IFNMG - which receives waste from the academic and school community), and the Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP, which receives all the sewage from the municipality); and one in Rubelita, also at the WWTP of that municipality.

Samples were collected biweekly using the composite sampling technique, which consists of collecting approximately 1L of sewage every 10 minutes, for three repetitions. The sewage was then homogenized, and 500 mL were collected and stored in properly labeled plastic containers. The collected samples were stored in a cooler with ice and transported to the Molecular Biology Laboratory of IFNMG – Salinas Campus for analysis of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The researchers involved used all necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) to avoid contamination, such as lab coats, masks, and gloves.

2.2. Sample Concentration and RNA Extraction

The sewage samples were subjected to a viral concentration technique using electonegative membrane filtration, commonly used for the concentration of enteric viruses [

13,

14]. Initially, 1 mL of magnesium chloride (MgCl2) was added to every 100 mL of sample. Next, acidification was performed by adding acetic acid (CH3COOH) until the pH reached values between 3 and 3.5 [

14].

The samples were then filtered through 0.45μm cellulose ester electonegative membranes, 47mm in diameter (MF-Millipore), attached to a Buchner funnel and vacuum pump. After filtration, the membranes were stored in tubes containing RNAlater to preserve the genetic material, along with silica beads for membrane disruption using a Loccus L-Beader 24® tissue homogenizer.

After membrane disintegration, 600µL of lysis solution (buffer PM1 from the ThermoFisher extraction kit, PureLink RNA Mini Kit®) was added to the tube, mixed with 6µL of 2-mercaptoethanol. The samples were centrifuged (14,000g, 15 minutes, at 8°C), and the 800µL supernatant was used for the extraction process, following the protocol provided by the ThermoFisher PureLink RNA Mini Kit® manufacturer.

2.3. Viral Detection

For viral RNA detection, RT-qPCR was performed targeting the E gene (envelope) of the virus and the RNAse-P gene as a reaction control, both included in the commercial MOLECULAR SARS-CoV-2 (EDx) – Bio-Manguinhos® kit, following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C for 15 minutes, 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 58°C for 30 seconds.

The primers used targeted the envelope gene (E_Sarbeco_F1: ACAGGTACGTTAATAGTTAATAGCGT; E_Sarbeco_R2: ATATTGCAGCAGTACGCACACA; and E_Sarbeco_P1: FAM-ACACTAGCCATCCTTACTGCGCTTCG-NFQ), with an extraction control for the RNAse-P gene (RdRP_SARSr-F2: GTGARATGGTCATGTGTGGCGG; RdRP_SARSr-R1: CARATGTTAAASACACTATTAGCATA; and RdRP_SARSr-P2: VIC-CAGGTGGAACCTCATCAGGAGATGC-NFQ)[

15]. For the RT-qPCR assays, a QuantStudio 3 thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher®) was used.

Each sample was tested in duplicate [

16]. Samples were considered negative when the cycle threshold (Ct) was below 40 (

Supplementary Table S1) [

16]. The results were tabulated using Microsoft Excel® for monitoring viral circulation during the sampled period.

2.4. Scientific Dissemination

Aiming at generating information for controlling the virus spread and providing the community with feedback on the research, we prepared epidemiological bulletins disseminated to the authorities through the official IFNMG channels, as well as in the form of informative posts on social media, allowing for the visualization of SARS-CoV-2 presence at sampling points over time. Social media was also used to promote clear and accessible communication for the general population.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Collection and SARS-CoV-2 RNA Detection in Wastewater Samples

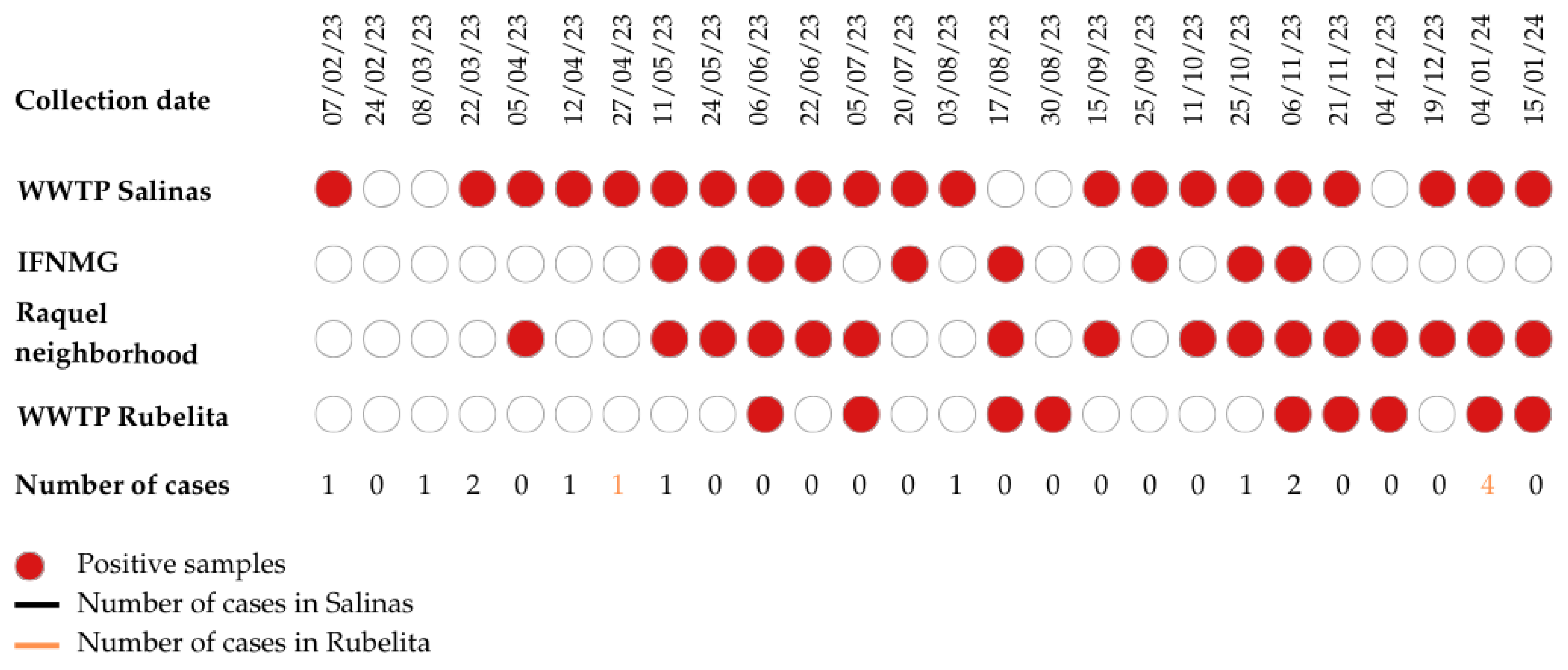

Between February 2023 and January 2024, we conducted 26 biweekly collections at each of the three sampling points in the municipality of Salinas and one sampling point in Rubelita. A total of 104 wastewater samples were collected, with 78 samples from Salinas and 26 from Rubelita. In total, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 55 (52.88%) of the samples (

Table 1). In Salinas, 46 (58.9%) tested positive, and in Rubelita, 9 (34.6%). The highest positivity rate was found at the WWTP in Salinas, with 21 positive samples, and the lowest at IFNMG and Rubelita, with 9 positive samples (

Table 1). The mean Ct values of the positive samples ranged from 31.0 to 39.0 (

Supplementary Table S1).

Importantly, the virus was detected at least at one of the sampling points in every collection, except for 03/02/2023, 24/02/2024, and 08/03/2024 (

Figure 2,

Supplementary Table S1). Despite this, only 15 human cases of COVID-19 were confirmed during the same one-year period [

5]. The distribution of positive samples varied throughout the year, with detection peaks (in which viral RNA was detected at all points) between weeks 08 and 11 (11/05/2023 to 22/06/2023), when only 1 case was reported in Salinas and none in Rubelita, and weeks 20 and 21 (25/10/2023 to 06/11/2023), when 1 case was reported in Salinas and none in Rubelita [

5]. Weeks 25 and 26 (04/01/2024 to 15/01/2024) also showed positivity peaks for all points except for IFNMG, as shown in

Figure 2.

3.2. Epidemiological Bulletins

The periodic results of the collections were communicated firsthand to the health authorities of the involved municipalities to support local epidemiological surveillance and facilitate decision-making. Additionally, during the collection period, digital content was created for the Instagram account of the Laboratory of Insect Behavior (LACOI), @lacoi_ifnmg, including 8 feed posts and 24 story posts as a means of scientific dissemination (

Table 2). Bulletins were also produced to share the results on social media and the institutional website of IFNMG, as shown in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has a high transmission capacity and was responsible for a pandemic with profound social, economic, and public health impacts [

17]. Although the pandemic has been officially declared over [

18], continuous surveillance of the virus is essential for outbreak detection and the implementation of control measures. In this context, wastewater monitoring emerges as an important surveillance tool, and wastewater-based epidemiology has proven to be a valuable approach for monitoring health-related aspects in different parts of the world [

9]. Here, we report the results and potential of this type of monitoring.

SARS-CoV-2 detection rates in wastewater are typically directly proportional to the contributing population size of the effluent—where larger populations facilitate the detection of viral RNA [

19]. However, this study underscores the applicability of wastewater surveillance as a robust epidemiological tool, even in small municipalities with low Human Development Indexes (HDI), such as Salinas and Rubelita – MG (41,178 and 5,679 inhabitants, respectively). Gudra

et al. [

20] similarly identified SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater from two small towns in Latvia, Jelgava (~55,000 inhabitants) and Kuldiga (~11,000 inhabitants), further validating the sensitivity and adaptability of this method. Furthermore, other cities in Minas Gerais state, such as Belo Horizonte and Contagem [

21], have implemented wastewater-based surveillance within large urban centers characterized by high HDI, substantial population densities, and significant commuter inflows. These contrasting scenarios highlight the versatility of wastewater surveillance in providing actionable epidemiological insights across diverse demographic and socioeconomic contexts.

It is noteworthy that viral RNA was detected in 24 out of 26 sampling weeks, including all those collected after the World Health Organization declared the end of the pandemic on May 5, 2023 (

Figure 2). Similarly, Tateishi et al. [

22] and Da Silva et al. [

23] reported positive wastewater samples for SARS-CoV-2 after the official end of the pandemic, highlighting wastewater surveillance as an effective early warning system for potential new outbreaks. Thus, the declaration of the pandemic end does not equate to the eradication of COVID-19, and preventive measures must continue, particularly the reinforcement of vaccine doses for at-risk groups such as the elderly and individuals with comorbidities. Monitoring viral variants also remains crucial for the detection of more pathogenic lineages or those with vaccine-escape potential [

24].

Despite the almost constant circulation of the virus in wastewater, few cases were reported during the entire collection period. The State Health Department of Minas Gerais issued weekly epidemiological bulletins to analyze and disseminate information on COVID-19 cases in the state (Coronavirus Bulletin). During the study period, the bulletins reported only ten human cases in Salinas and five in Rubelita (

Figure 2). [

25]. Several factors may explain this underreporting, such as limited access to clinical testing, the ongoing vaccine distribution since 2021, and prior infections, which together contribute to milder symptomatology [

26], thereby reducing the demand for testing and visits to primary healthcare units.

Throughout the year, viral detection peaks were observed, when viral RNA was found at all collection sites (

Figure 2). These peaks coincided with significant climatic and behavioral factors, such as the winter period, which is conducive to the transmission of respiratory viruses, as well as national holidays in October/November and the year-end recess, which increase the movement of people between different states/municipalities. This trend mirrors the pattern observed in Brazil since 2020 [

25,

27].

The disparity in the proportion of positive samples between Salinas and Rubelita, with 58.9% and 34.6% positivity rates, respectively, can be attributed to Salinas having a population seven times larger than Rubelita (41,000 vs. 5,600 inhabitants) and a higher population density (21 inhabitants/km² vs. 5 inhabitants/km²) [

12,

19]. Salinas is a microregion of significant importance for the regional economy, education, and healthcare, making it a location with a notable presence of individuals from other municipalities. The IFNMG campus in Salinas, for instance, has two boarding schools for students from neighboring municipalities, accommodating 164 residents (direct communication) who circulate on campus daily. Furthermore, a nephrology service is available at the local hospital, serving patients from several cities, with a capacity of up to 180 patients [

28], which further contributes to the movement of people in the area, increasing the likelihood of viral transmission [

19].

Another factor that may contribute to the difference in positive samples between the municipalities is the level of sanitation services available to the population. Salinas has an estimated population of 40,178 inhabitants, with 66.15% of the population receiving sanitation services. In contrast, Rubelita has a population of 5,679 inhabitants, with only 25.7% coverage of sanitation services, which reduces the number of people served and consequently the detection of viral RNA [

12].

The limitations of this study include its small geographical scope, as it encompasses only two municipalities, and the absence of viral load quantification in the samples due to technical constraints. Nevertheless, the data obtained in this study demonstrate the ongoing circulation of SARS-CoV-2 within the sampled populations and emphasize the importance of continuing the immunization program, including the expansion of booster doses, particularly among at-risk groups such as the elderly and individuals with comorbidities. In this context, scientific dissemination efforts, such as those carried out in this study, are essential to ensure that academic research findings extend beyond the academic community. Therefore, the continuation of wastewater-based surveillance is recommended, as it has proven to be an important epidemiological tool applicable to diverse urban and social contexts, preferably coupled with scientific dissemination initiatives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Detailed list of infected samples with CT values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.O., F.V.S.d.A., R.d.F.B. and T.d.J.T.; methodology, A.d.O.F., C.H.d.O., F.V.S.d.A., G.B.P., P.A.A.S. and T d.J.T.; software, A.d.O.F., G.B.P., P.A.A.S and, T.d.J.T.; validation, A.F.A.D., D.B.d.O., F.V.S.d.A., L.d.M.B.C. and R.d.F.B..; formal analysis A.d.O.F., C.H.d.O., G.B.P., P.A.A.S., and T.d.J.T.; investigation, A.d.O.F., C.H.d.O., G.B.P., P.A.A.S., T.d.J.T., and F.V.S.d.A.; resources, D.B.O., F.V.S.d.A., and R.d.F.B.; data curation, C.H.d.O., and T.d.J.; writing—original draft preparation, F.V.S.d.A and T.d.J.T.; writing—review and editing, A.d.O.F., A.F.A.D., C.H.d.O., D.B.d.O., F.V.S.d.A., G.B.P., L.d.M.B.C., P.A.A.S., R.d.F.B and T.d.J.T.; visualization, A.d.O.F and T.d.J.T.; supervision, A.F.A.D., D.B.d.O., F.V.S.d.A., L.d.M.B.C and R.d.F.B.; project administration, A.F.A.D., L.d.M.B.C. and R.d.F.B.; funding acquisition, R.d.F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This work received financial support from REMONAR (MCTI, Grant nº 400284/2022-7), CNPq (Grant nº 401933/2020–2) and Fapemig (Grant nº APQ-01403-21). GPB and PAAS were granted with CNPq schoolarship

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the manuscript and are fully available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ebrille, E.; Lucciola, M.T.; Amellone, C.; Ballocca, F.; Orlando, F.; Giammaria, M. Syncope as the Presenting Symptom of COVID-19 Infection. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2020, 6, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, W.K.; Duarte, E.; de França, G.V.A.; Garcia, L.P. Como o Brasil Pode Deter a COVID-19. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde Coronavírus Brasil. Available online: https://covid.saude.gov.br/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Luiz, A.; Lopes, S.; De Cássia Gusmão, G. A Relação Entre Pobreza e Desigualdade Na Região Norte de Minas Gerais. XV Seminário sobre economia mineira: anais. Anais eletrônicos... Belo Horizonte: UFMG/Cedeplar 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaria Estadual de Saúde de Minas Gerais. Portal de Informações Em Saúde. Available online: https://info.saude.mg.gov.br/1/paineis/2 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Hovi, T.; Shulman, L.M.; Van Der Avoort, H.; Deshpande, J.; Roivainen, M.; De Gourville, E.M. Role of Environmental Poliovirus Surveillance in Global Polio Eradication and Beyond. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno Ferraro, G.; Veneri, C.; Mancini, P.; Iaconelli, M.; Suffredini, E.; Bonadonna, L.; Lucentini, L.; Bowo-Ngandji, A.; Kengne-Nde, C.; Mbaga, D.S.; et al. A State-of-the-Art Scoping Review on SARS-CoV-2 in Sewage Focusing on the Potential of Wastewater Surveillance for the Monitoring of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Food Environ. Virol. 2022, 14, 315–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, C.L.F.; da Silva, M.S.; dos Santos, D.S.; Braga, T.G.M.; de Freitas, T.P.M. Impactos Socioambientais Da Pandemia de SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) No Brasil: Como Superá-Los? Revista Brasileira de Educação Ambiental (RevBEA) 2020, 15, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Bueno, R.; Claro, I.C.M.; Augusto, M.R.; Duran, A.F.A.; Camillo, L.d.M.B.; Cabral, A.D.; Sodré, F.F.; Brandão, C.C.S.; Vizzotto, C.S.; Silveira, R.; et al. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology: A Brazilian SARS-COV-2 Surveillance Experience. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medema, G.; Heijnen, L.; Elsinga, G.; Italiaander, R.; Brouwer, A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in Sewage and Correlation with Reported COVID-19 Prevalence in the Early Stage of the Epidemic in The Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, T.; Fumian, T.M.; Mannarino, C.F.; Resende, P.C.; Motta, F.C.; Eppinghaus, A.L.F.; Chagas do Vale, V.H.; Braz, R.M.S.; de Andrade, J.d.S.R.; Maranhão, A.G.; et al. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology as a Useful Tool to Track SARS-CoV-2 and Support Public Health Policies at Municipal Level in Brazil. Water Res. 2021, 191, 116810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE Salinas (MG) | Cidades e Estados | IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/mg/salinas.html (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Ahmed, W.; Harwood, V.J.; Gyawali, P.; Sidhu, J.P.S.; Toze, S. Comparison of Concentration Methods for Quantitative Detection of Sewage-Associated Viral Markers in Environmental Waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 2042–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Angel, N.; Edson, J.; Bibby, K.; Bivins, A.; O’Brien, J.W.; Choi, P.M.; Kitajima, M.; Simpson, S.L.; Li, J.; et al. First Confirmed Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Untreated Wastewater in Australia: A Proof of Concept for the Wastewater Surveillance of COVID-19 in the Community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corman, V.M.; Landt, O.; Kaiser, M.; Molenkamp, R.; Meijer, A.; Chu, D.K.; Bleicker, T.; Brünink, S.; Schneider, J.; Schmidt, M.L.; et al. Detection of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) by Real-Time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Bivins, A.; Metcalfe, S.; Smith, W.J.M.; Verbyla, M.E.; Symonds, E.M.; Simpson, S.L. Evaluation of Process Limit of Detection and Quantification Variation of SARS-CoV-2 RT-QPCR and RT-DPCR Assays for Wastewater Surveillance. Water Res. 2022, 213, 118132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardana, M.; Breslin, J.; Cortez, J.M.; Rivera, S.; Webster, S.; Ibarrondo, F.J.; Yang, O.O.; Pyles, R.B.; Ramirez, C.M.; Adler, A.P.; et al. Longitudinal COVID-19 Surveillance and Characterization in the Workplace with Public Health and Diagnostic Endpoints. mSphere 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations- (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Wu, Y.; Guo, C.; Tang, L.; Hong, Z.; Zhou, J.; Dong, X.; Yin, H.; Xiao, Q.; Tang, Y.; Qu, X.; et al. Prolonged Presence of SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA in Faecal Samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudra, D.; Dejus, S.; Bartkevics, V.; Roga, A.; Kalnina, I.; Strods, M.; Rayan, A.; Kokina, K.; Zajakina, A.; Dumpis, U.; et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Wastewater and Importance of Population Size Assessment in Smaller Cities: An Exploratory Case Study from Two Municipalities in Latvia. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernicharo, C.A.d.L.; Araújo, J.C.; Mota Filho, C.R.; Bressani-Ribeiro, T.; Chamhum-Silva, L.; Leal, C.D.; Leroy, D.F.; Machado, E.C.; Cordero, M.F.S.; Azevedo, L.; et al. Monitoramento Do Esgoto Como Ferramenta de Vigilância Epidemiológica Para Controle Da COVID-19: Estudo de Caso Na Cidade de Belo Horizonte. Eng. Sanit. E Ambient. 2021, 26, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateishi, S.; Hamada, K.; Emoto, N.; Abe, K.; Abe, K.; Kawasaki, Y.; Sunohara, M.; Moriya, K.; Katayama, H.; Tsutsumi, T.; et al. Facility Wastewater Monitoring as an Effective Tool for Pandemic Infection Control: An Experience in COVID-19 Pandemic with Long-Term Monitoring. J. Infect. Chemother. 2025, 31, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.C.M.d.; Santos, C.R.d.L.; Céleri, E.P.; Salles, D.; Fardin, J.M.; Pussi, K.F.; Gomes, D.C.d.O.; Ribeiro, V.d.O.; Konrad-Moraes, L.C.; Neitzke-Abreu, H.C.; et al. An Epidemiological Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in the Sewage System of a Higher Education Institution. Ann. Glob. Health 2024, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, O.; Plank, M.J.; Cowling, B.J.; Howden, B.P.; Kucharski, A.J.; Sullivan, S.G.; Vandemaele, K.; Viboud, C.; Riley, S.; McCaw, J.M.; et al. Key Challenges for Respiratory Virus Surveillance While Transitioning out of Acute Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaria de Estado de Saúde de Minas Gerais Boletim Epidemiológico. Available online: https://coronavirus.saude.mg.gov.br/boletim (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Rodda, L.B.; Netland, J.; Shehata, L.; Pruner, K.B.; Morawski, P.A.; Thouvenel, C.D.; Takehara, K.K.; Eggenberger, J.; Hemann, E.A.; Waterman, H.R.; et al. Functional SARS-CoV-2-Specific Immune Memory Persists after Mild COVID-19. Cell 2021, 184, 169–183.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berra, T.Z.; Alves, Y.M.; Popolin, M.A.P.; da Costa, F.B.P.; Tavares, R.B.V.; Tártaro, A.F.; Moura, H.S.D.; Ferezin, L.P.; de Campos, M.C.T.; Ribeiro, N.M.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil: Space-Time Approach of Cases, Deaths, and Vaccination Coverage (February 2020 – April 2024). BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fundação Dilson Godinho Unidades. Available online: https://www.fundacaodilsongodinho.org.br/page/unidades (accessed on 11 February 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).