Submitted:

07 February 2024

Posted:

08 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Environmental Sampling Strategy

2.2. Samples Concentration

2.3. Viral Nucleic Acids Extraction and Purification

2.4. Viral Nucleic Acids Detection

2.5. Data Adjustment and Normalization

- -

- Normalized Viral Load (hereafter viral load) is expressed as GC/day/100,000 inhabitants and x is the identification number of each WWTP (namely: 1, 2, 3, 4);

- -

- Conc.virus is the concentration of virus detected (GC/L);

- -

- Fd is the daily wastewater flow rate of WWTPs (L/day);

- -

- 105 is a constant used to refer the viral load to 100,000 inhabitants;

- -

- P is the number of inhabitants served by each WWTP.

2.6. Historical Data on SARS-CoV-2

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

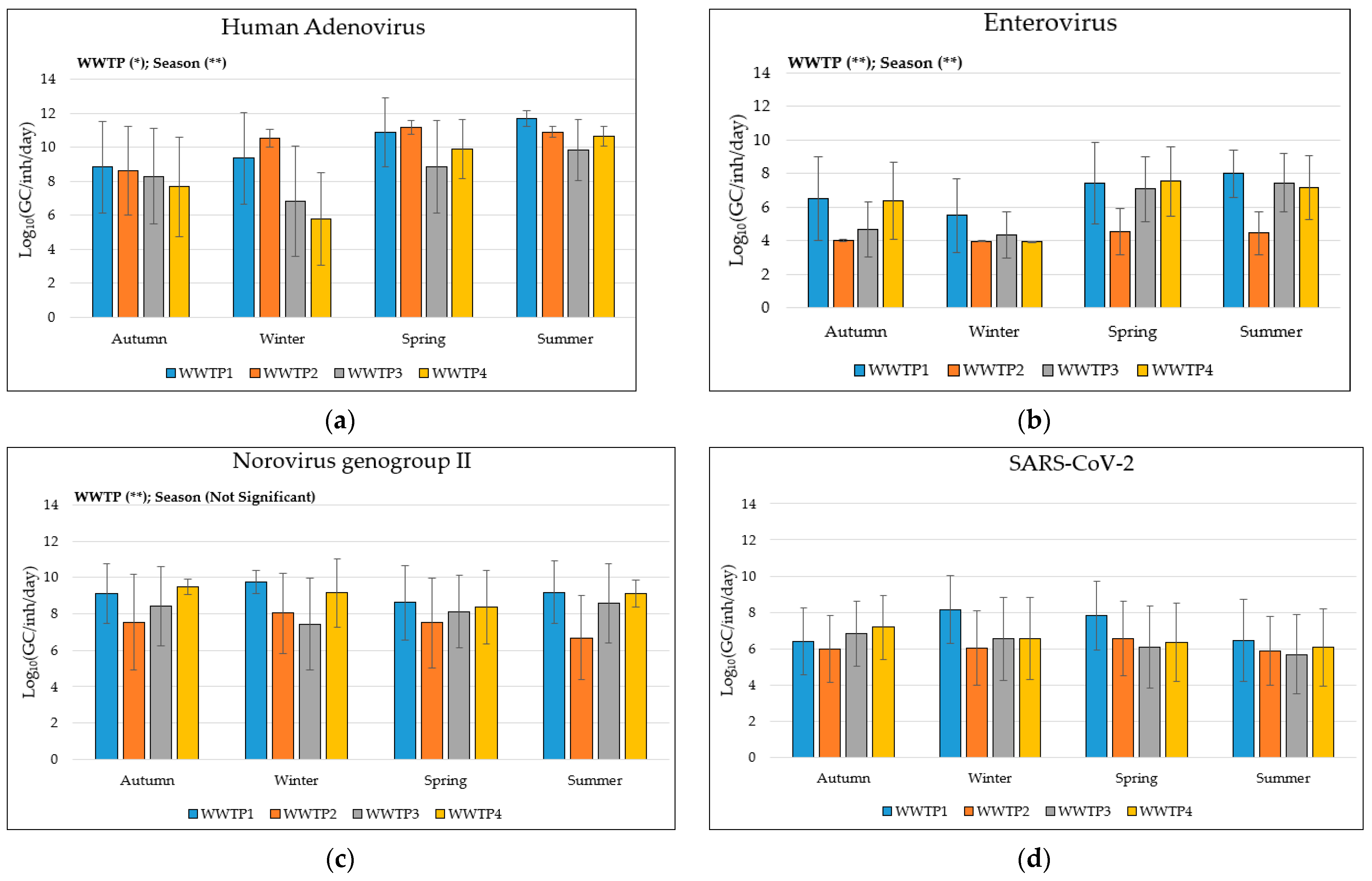

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Viruses’ Data

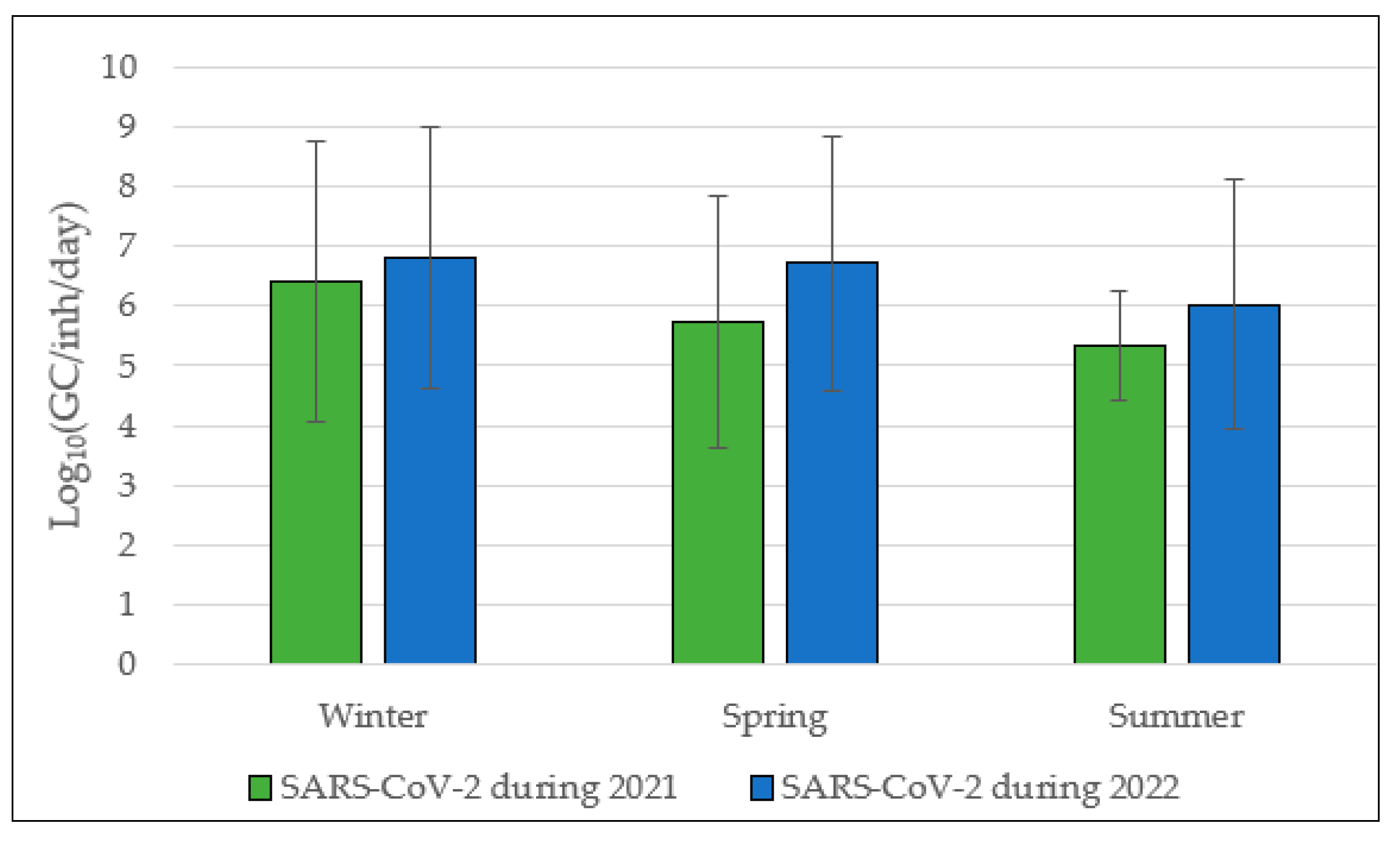

3.2. SARS-CoV-2 Annual Trend from 2021 to 2022

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Melnick, J.L. Poliomyelitis virus in urban sewage in epidemic and in nonepidemic times. Am J Hyg., Mar. 1947, Vol. 45, no. 2, pp: 240-253. [CrossRef]

- Hovi, T; Shulman, L.M; Van Der Avoort, H.; Deshpande, J.; Roivainen, M; De Gourville, E.M. Role of environmental poliovirus surveillance in global polio eradication and beyond. Epidemiology and Infection, Jan. 2012, Vol. 140, no. 1, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Zoni, R; Mezzetta, S; Affanni, P; Colucci M.E.; Fiore, S.; Fontana, S.; Bracchi, M.; Capobianco, E.; Veronesi, L. Poliovirus and non-polio-enterovirus environmental surveillance in Parma within the “Global Polio Eradication Program” (GPEI)’, Acta Biomedica, 2019, Vol. 90, no. 9 S, pp. 95–97. [CrossRef]

- Klapsa, D.; Wilton, T.; Zealand, A.; Bujaki, E.; Saxentoff, E.; Troman, C.; Shaw, A.G.; Tedcastle, A.; Majumdar, M.; Mate, R.; Akello, J.O.; Huseynov, S.; Zeb, A.; Zambon, M.; Bell, A.; Hagan, J.; Wade, M.J.; Ramsay, M.; Grassly, N.C.; Saliba, V.; Martin, J. Sustained detection of type 2 poliovirus in London sewage between February and July, 2022, by enhanced environmental surveillance, The Lancet, Oct. 2022, Vol. 400, no. 10362, pp. 1531–1538. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman N.S.; Bar-Or, I.; Sofer, D.; Bucris, E.; Morad, H.; Shulman, L.M.; Levi, N.; Weiss, L.; Aguvaev, I.; Cohen, Z.; Kestin, K.; Vasserman, R.; Elul, M.; Fratty, I.S.; Geva, M.; Wax, M.; Erster, O.; Yishai, R.; Hecht-Sagie, L.; Alroy-Preis, S.; Mendelson, E.; Weil, M. Emergence of genetically linked vaccine-originated poliovirus type 2 in the absence of oral polio vaccine, Jerusalem, April to July 2022, Eurosurveillance, Sep. 2022, Vol. 27, no. 37. [CrossRef]

- Ryerson, A.B.; Lang, D.; Alazawi, M.A.; Neyra, M.; Hill, D.R.; St. George, K.; Fuschino, M.; Lutterloh, E.; Backenson, B.; Rulli, S.; Schnabel Ruppert, P.; Lawler, J.; McGraw, N.; Knecht, A.; Gelman, I.; Zucker, J.R.; Omoregie, E.; Kidd, S.; Sugerman, D.E.; Jorba, J.; Gerloff, N.; Fei Fan Ng, T.; Lopez, A.; Masters, N.B.; Leung, J.; Burns, C.C.; Routh, J.; Bialek, S.R.; Oberste, M.S.; Rosenberg, E.S. Wastewater Testing and Detection of Poliovirus Type 2 Genetically Linked to Virus Isolated from a Paralytic Polio Case — New York, March 9–October 11, 2022. Available online: https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/ (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality: fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda, 4th ed; Geneva, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dzinamarira, T.; Pierre, G.; Iradukunda P.G.; Tungwarara, N.; Mukwenha, S.; Mpabuka, E.; Kidson Mataruka, K.; Chitungo, I.; Musukaf, G.; Murewanhema, G. Epidemiological surveillance of enteric viral diseases using wastewater in Africa – A rapid review, Journal of Infection and Public Health, Jun. 01, 2022, Vol. 15, no. 6. Elsevier Ltd., pp. 703–707. [CrossRef]

- Hellmér, M.; Paxéus, N.; Magnius, L.; Enache, L.; Arnholm, N.; Johansson, A.; Bergström, T.; Norder, H. Detection of pathogenic viruses in sewage provided early warnings of hepatitis A virus and norovirus outbreaks, Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014, Vol. 80, no. 21, pp. 6771–6781. [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A.; Verani, M.; Battistini, R.; Pizzi, F.; Rovini, E.; Andreoli, E.; Casini B. Epidemiological surveillance of human enteric viruses by monitoring of different environmental matrices, Water Science and Technology, 2006, Vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 239–244. [CrossRef]

- Sedmak, G.; Bina, D.; MacDonald, J. Assessment of an Enterovirus Sewage Surveillance System by Comparison of Clinical Isolates with Sewage Isolates from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Collected August 1994 to December 2002, Appl Environ Microbiol, Dec. 2003, Vol. 69, no. 12, pp. 7181–7187. [CrossRef]

- Chacón, L.; Morales, E.; Valiente, C.; Reyes, L.; Barrantes, K. Wastewater-based epidemiology of enteric viruses and surveillance of acute gastrointestinal illness outbreaks in a resource-limited region, American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Oct. 2021, Vol. 105, no. 4, pp. 1004–1012. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Neyvaldt, J.; Enache, L.; Sikora, P.; Mattsson, A.; Johansson, A.; Lindh, M.; Bergstedt, O.; Norder, H. Variations among Viruses in Influent Water and Effluent Water at a Wastewater Plant over One Year as Assessed by Quantitative PCR and Metagenomics, Appl Environ Microbiol, Nov. 2020, Vol. 86, no. 24. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Torres-Franco, A.; Rodriguéz, E.; Diaz, I.; Koritnik, T.; Gomes da Silva, P.; Mesquita, J.R.; Trkov, M.; Paragi, M.; Muñoz, R.; García-Encina P.A. Centralized and decentralized wastewater-based epidemiology to infer COVID-19 transmission – A brief review, One Health, Dec. 01, 2022, Vol. 15. Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, N.E.; Fout, G.S.; Keely, S.P. Retrospective Surveillance of Wastewater To Examine Seasonal Dynamics of Enterovirus Infections, mSphere, Jun. 2017, Vol. 2, no. 3. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, J.; O’Brien, J.; Sivakumar, M.; Jiang, G. Back-estimation of norovirus infections through wastewater-based epidemiology: A systematic review and parameter sensitivity, Water Research, Jul 01, 2022, Vol. 219. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Kallem, P.; Hegab, H.; Alsafar, H.; Hasan, S.W.; Banat, F. SARS-CoV-2 detection and inactivation in water and wastewater: review on analytical methods, limitations and future research recommendations, Emerging Microbes and Infections, 2023, Vol. 12, no. 2. Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Ciannella, S.; González-Fernández, C.; Gomez-Pastora, J. Recent progress on wastewater-based epidemiology for COVID-19 surveillance: A systematic review of analytical procedures and epidemiological modeling, Science of the Total Environment, Jun. 20, 2023, Vol. 878. Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EU) Commission Recommendation (EU) n° 2021/472 of 17 March 2021 on a Common Approach to Establish a Systematic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 and its Variants in Wastewaters in the EU-Publications Office of the EU. Retrieved July 6, 2023. Available online: https:// op. europa. eu/ en/ publi cation- detai l/-/ publication/ 05b46 cb0- 8855- 11eb- ac4c- 01aa7 5ed71 a1/ langu age- en/format- PDF.

- Verani M.; Federigi, I.; Muzio, S.; Lauretani, G.; Calà, P.; Mancuso, F.; Salvadori, R.; Valentini, C.; La Rosa, G.; Suffredini, E.; Carducci, A. Calibration of Methods for SARS-CoV-2 Environmental Surveillance: A Case Study from Northwest Tuscany, Int J Environ Res Public Health, Dec. 2022, Vol. 19, no. 24. [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A.; Federigi, I.; Lauretani, G.; Muzio, S.; Pagani, A.; Atomsa, N.T, Verani, M. Critical Needs for Integrated Surveillance: Wastewater-Based and Clinical Epidemiology in Evolving Scenarios with Lessons Learned from SARS-CoV-2, Food Environ Virol, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, G; Bonadonna L.; Suffredini, E. Protocollo della Sorveglianza di SARS-CoV-2 in reflui urbani (SARI) - rev. 3. Zenodo, Jul 25, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hernroth, B.E.; Conden-Hansson, A.C.; Rehnstam-Holm, A.S.; Girones, R.; Allard, A.K. Environmental factors influencing human viral pathogens and their potential indicator organisms in the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis: The first Scandinavian report, Appl Environ Microbiol, Sep. 2002, Vol. 68, no. 9, pp. 4523–4533. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson K.A.; Griffin D.W.; Paul J.H. Detection, quantitation and identification of enteroviruses from surface waters and sponge tissue from the Florida Keys using real-time RT-PCR. Water Res, 2002, Vol 36, no. 10, pp. 2505-2514. [CrossRef]

- Skraber, S.; Ogorzaly, L.; Helmi, K.; Maul, A.; Hoffmann, L.; Cauchie, H.M.; Gantzer, C. Occurrence and persistence of enteroviruses, noroviruses and F-specific RNA phages in natural wastewater biofilms. Water Res, 2009, Vol 43, no. 19, pp. 4780–4789. [CrossRef]

- Bisseux, M.; Colombet, J.; Mirand, A.; Archimbaud, C.; Peigue-Lafeuille, H.; Roque-Afonso, A.M.; Abravanel, F.; Izopet, J.; Debroas, D.; Bailly, J.L.; Henquell, C. Monitoring human enteric viruses in wastewater and relevance to infections encountered in the clinical setting: a one-year experiment in central France, Euro Surveill., 2018, Vol. 23, no. 7, 17-00237. [CrossRef]

- Vetter, M.R.; Staggemeier, R.; Vecchia, A.D.; Henzel, A.; Rigotto, C.; Spilki, F.R. Seasonal variation on the presence of adenoviruses in stools from non-diarrheic patients, Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, Jul. 2015, Vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 749–752. [CrossRef]

- Maniah, K.; Nour, I.; Hanif, A.; Yassin, M.T.; Alkathiri, A.; Al-Ashkar, I.; Eifan, S. Molecular Identification of Human Adenovirus Isolated from Different Wastewater Treatment Plants in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Surveillance and Meteorological Impacts. Water (Switzerland), Apr. 2023, Vol 15, no. 7. [CrossRef]

- Elmahdy, E.M.; Ahmed, N.I.; Shaheen, M.N.F.; Mohamed, E.C.B.; Loutfy, S.A. Molecular detection of human adenovirus in urban wastewater in Egypt and among children suffering from acute gastroenteritis, J Water Health, Apr. 2019, Vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 287–294. [CrossRef]

- Price, R.H.M.; Graham, C.; Ramalingam, S. Association between viral seasonality and meteorological factors, Sci Rep, Dec 2019, Vol. 9, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.T.; Phanikumar, M.S.; Xagoraraki, I.; Rose, J.B. Quantitative detection of human adenoviruses in wastewater and combined sewer overflows influencing a Michigan river, Appl Environ Microbiol, Feb. 2010, Vol. 76, no. 3, pp. 715–723. [CrossRef]

- Takuissu G.R.; Kenmoe S.; Ebogo-Belobo J.T.; Kengne-Ndé C.; Mbaga D.S.; Bowo-Ngandji A.; Ondigui Ndzie J.L.; Kenfack-Momo R.; Tchatchouang S.; Kenfack-Zanguim J.; Lontuo Fogang R.; Zeuko’o Menkem E.; Kame-Ngasse G.I.; Magoudjou-Pekam J.N.; Suffredini E.; Veneri C.; Mancini P.; Bonanno Ferraro G.; Iaconelli M.; Verani M.; Federigi I.; Carducci A.; La Rosa G. Exploring adenovirus in water environments: a systematic review and meta-analysis, International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Iaconelli, M.; Valdazo-González, B.; Equestre, M.; Ciccaglione, A. R.; Marcantonio, C.; Della Libera, S.; La Rosa, G. Molecular characterization of human adenoviruses in urban wastewaters using next generation and Sanger sequencing, Water Res., Sep. 15, 2017, Vol. 121, pp. 240-247. [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Figueroa, A.; Rosales, R. E.; Fernández, R.; Ramírez, V.; Bastardo, M.; Farías, A., Vizzi, E. Detection and diversity of gastrointestinal viruses in wastewater from Caracas, Venezuela, 2021-2022. Virology, 2024, Vol. 589, 109913. [CrossRef]

- Allayeh, A. K.; Al-Daim, S. A.; Ahmed, N.; El-Gayar, M.; Mostafa, A. Isolation and Genotyping of Adenoviruses from Wastewater and Diarrheal Samples in Egypt from 2016 to 2020. Viruses, 2022, Vol. 14, 10 2192. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tan, Z.; Gao, X.; Li, X.; Yang, D. Whole Genomic Sequence Analysis of Human Adenovirus Species C Shows Frequent Recombination in Tianjin, China. Viruses, 2023, Vol. 15, 4, 1004. [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A.; Viviani, L.; Pagani, A.; Atomsa, N. T.; Lauretani, G.; Federigi, I; Verani, M. Wastewater Based Surveillance of Respiratory Viruses for public health purposes: opportunities and challenges. In IWA World Water Congress & Exhibition, Toronto, Canada, 11-15 August 2024; submitted.

- Pons-Salort, M.; Oberste, M.S.; Pallansch, M.A.; Abedi, G.R.; Takahashi, S.; Grenfell, B.T.; Grassly, N.C. The seasonality of nonpolio enteroviruses in the United States: Patterns and drivers, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, Mar. 2018, Vol. 115, no. 12, pp. 3078–3083. [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Yeo, S.; Lee, B.; Park. K.; Song, J.; Yu, J.; Rheem, I.; Kim, J.; Hwang, S.; Choi, Y.; Cheon, D.; Park, J. Epidemics of enterovirus infection in Chungnam Korea, 2008 and 2009, Virol J, 2011, Vol. 8. [CrossRef]

- Rajtar, B.; Majek, M.; Polański, Ł.; Polz-Dacewicz, M. Enteroviruses in water environment-a potential threat to public health, Ann Agric Environ Med, 2008, Vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 199–203.

- Rohayem, J. Norovirus seasonality and the potential impact of climate change, Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2009, Vol. 15, no. 6. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 524–527. [CrossRef]

- Liu X.; Huang J.; Li C.; Zhao Y.; Wang D.; Huang Z.; Yang K. The role of seasonality in the spread of COVID-19 pandemic, Environ Res, Apr. 2021, Vol. 195. [CrossRef]

- Sharun, K.; Tiwari, R.; Dhama, K. COVID-19 and sunlight: Impact on SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility, morbidity, and mortality, Annals of Medicine and Surgery, Jun. 01, 2021, Vol. 66. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.; Poon, B.P.; Lam, J.; Sultana, A.; Christie-Holmes, N.; Mubareka, S.; Gray-Owen, S.D.; Farnood, R. Exploring the Differences in the Response of SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron to Ultraviolet Radiation, ACS ES and T Engineering, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lorente-González, M.; Suarez-Ortiz, M.; Landete, P. Evolution and Clinical Trend of SARS-CoV-2 Variants, Open Respiratory Archives, Apr. 01, 2022, Vol. 4, no. 2. Elsevier Espana S.L.U. [CrossRef]

- Bisseux, M.; Colombet, J.; Mirand, A.; Roque-Afonso, A.M.; Abravanel, F; Izopet, J; Archimbaud, C; Peigue-Lafeuille, H; Debroas, D; Bailly, J.L.; Henquell, C. Monitoring human enteric viruses in wastewater and relevance to infections encountered in the clinical setting: a one-year experiment in central France, 2014 to 2015. Euro Surveill. Feb 2018, Vol. 23, no, pp. 17-00237. [CrossRef]

- Fantilli, A; Cola, G.D.; Castro, G.; Sicilia, P.; Cachi, A.M.; de Los Ángeles Marinzalda, M.; Ibarra, G.; López, L.; Valduvino, C.; Barbás, G.; Nates, S.; Masachessi, G.; Pisano, M.B.; Ré, V. Hepatitis A virus monitoring in wastewater: A complementary tool to clinical surveillance. Water Res. Aug 1, 2023, Vol. 241, 120102. [CrossRef]

- Casares-Jimenez, M; Garcia-Garcia, T; Suárez-Cárdenas, J.M.; Perez-Jimenez, A.B.; Martín, M.A.; Caballero-Gómez, J.; Michán, C.; Corona-Mata, D.; Risalde, M.A.; Perez-Valero, I.; Guerra, R.; Garcia-Bocanegra, I.; Rivero, A.; Rivero-Juarez, A; Garrido, J.J. Correlation of hepatitis E and rat hepatitis E viruses urban wastewater monitoring and clinical cases. Sci Total Environ Jan 15, 2024, Vol. 908, 168203. [CrossRef]

- Rački, N; Dreo, T; Gutierrez-Aguirre, I; Blejec, A; Ravnikar, M. Reverse transcriptase droplet digital PCR shows high resilience to PCR inhibitors from plant, soil and water samples. Plant Methods. 2014, Vol. 10(1), 42. [CrossRef]

| Virus | Target region | Primers and Probes | Sequences (5′-3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Adenovirus | Ad hexon gene | AdF | CWTACATGCACATCKCSGG | [23] |

| AdR | CRCGGGCRAAYTGCACCAG | |||

| AdP1 | FAM-CCGGGCTCAGGTACTCCGAGGCGTCCT-TAMRA | |||

| Enterovirus | 5′UTR region | EVF | GGCCCCTGAATGCGGCTAAT | [24] |

| EVR | CACCGGATGGCCAATCCAA | |||

| EV | FAM-CGGACACCCAAAGTAGTCGGTTCCG-TAMRA | |||

| Norovirus ggII | ORF1-ORF2 region: RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) | JJV2F | CAAGAGTCAATGTTTAGGTGGATGAG | [25] |

| COG2R | TCGACGCCATCTTCATTCACA | |||

| RING2-TP | FAM-TGGGAGGGCGATCGCAATCT -BHQ | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | ORF1ab region: nsp14; 3′-to-5′ exonuclease |

2297 CoV-2-F | ACATGGCTTTGAGTTGACATCT | [20,21] |

| 2298 CoV-2-R | AGCAGTGGAAAAGCATGTGG | |||

| 2299 CoV-2-P | FAM-CATAGACAACAGGTGCGCTC-MGBEQ |

| Virus | WWTP1 | WWTP2 | WWTP3 | WWTP4 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Adenovirus | Positive samples (n°, %) |

42/48, 87.5% | 45/48, 93.7% | 36/51, 78.6% | 35/50, 70% | 158/197, 80.2% |

| Viral load Log10(GC/inh/day) |

10.3 ± 2.3 | 10.3 ± 1.6 | 8.5± 2.8 | 8.6 ± 2.9 | 9.4 ± 2.6 | |

| Enterovirus | Positive samples (n°, %) |

30/48, 62.5% | 4/48, 8.3% | 24/51, 47% | 29/50, 58.0% | 87/197, 44.2% |

| Viral load Log10(GC/inh/day) |

7.0 ± 2.3 | 4.3 ± 1 | 5.9 ± 2.1 | 6.6 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 2.2 | |

| Norovirus genogroup II | Positive samples (n°, %) |

44/48, 91.7% | 33/48, 68.7% | 42/51, 82.3% | 47/50, 94% | 166/197, 84.3% |

| Viral load Log10(GC/inh/day) |

9.1 ± 1.6 | 7.4 ± 2.4 | 8.2 ± 2.1 | 9.1 ± 1.4 | 8.5 ± 2.0 | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Positive samples (n°, %) |

30/48, 62.5% | 21/48, 43.7% | 22/51, 43.1% | 27/50, 54% | 100/197, 50.8% |

| Viral load Log10(GC/inh/day) |

7.2 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 6.5 ± 2.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).