1. Introduction

Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) is an approach of monitoring and analysing wastewater to identify and track the presence of various biological and chemical substances, including pathogens, drugs, and other pollutants. WBE has become an important tool in public health surveillance, allowing for early detection and tracking of infectious disease outbreaks, drug use trends, and environmental contaminants in communities. Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) has been widely used to monitor the presence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in communities [

1]. WBE can provide early warning of outbreaks by detecting the virus in sewage before people show symptoms or get tested, and it can also help to track the overall prevalence of the virus in a given area. By analysing wastewater samples from different locations within a community, public health officials can get a better understanding of the geographic distribution of the virus and use this information to guide the targeted interventions and prioritize resource allocation [

2]. Due to its rapid spread and the number of cases and deaths reported in multiple countries around the world COVID-19 the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared it as a pandemic on March 11, 2020. While some regions or countries may have experienced more severe outbreaks and resultant deaths than others, the global spread of the virus continues to be a public health concern. However, on May 5,2023 WHO declared that the COVID-19 “pandemic” is no longer a Public Health Emergency of International Concern considering the current severity of the disease [

3].

WBE has already been validated as an effective approach for monitoring and surveillance of pandemics such as COVID-19. Several studies have demonstrated that the detection of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in wastewater can serve as an early warning system for the presence of the virus in communities [

4,

5]. Furthermore, WBE has been shown to detect SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater several days before cases are reported through clinical testing [

6]. By monitoring wastewater from multiple locations within a community on a routine basis, public health officials can track the overall prevalence of the virus, estimate the number of infections, and detect changes in the prevalence of the virus over time. WBE has also been used to identify the presence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2 in communities [

7,

8]. By analysing wastewater samples, researchers can identify mutations in the viral genome and track the spread of new variants in a population. This guides targeted interventions and carry out resource allocation which helps manage the spread of the virus effectively.

India experienced a devastating second wave of COVID-19 cases between March and May 2021, with a peak in daily new cases exceeding 400,000 and a high death toll [

9]. However, since then, the number of reported cases and deaths has significantly declined. As of September 2021, the reported number of daily new cases had dropped to below 30,000, and the reported number of daily deaths had also declined. Our previous studies showed the importance of early detection of COVID-19 through WBE during the first and second wave in India [

10,

11]. As of 13 February 2023, according to Indian government figures, India has the second-highest number of confirmed cases in the world (after the United States of America) with 44,685,425 reported cases of COVID-19 infection and the third-highest number of COVID-19 deaths (after the United States and Brazil) at 530,753 deaths(covid19india.org). Although the number of reported cases has gone down now (1091 across India and 0 active cases in Rajasthan on 14 December 2023, as per mygov.in due to less severe symptoms and home rapid tests, the threat of death in patients with comorbidities persists. The mechanism and kinetics of spread of this disease have changed from being a pandemic which increases exponentially from a single point to an endemic mixed with occasional bouts of foreign origin variants. The cycles of disease waves have also become more akin to epidemics. Although decline in the number of active cases can be a positive sign, the disease still prevails, thus warranting development of suitable protocols for a continuous monitoring of sewage samples for forewarning and implementing measures to prevent further outbreaks. This is critical as COVID-19 may endemically be a long-term public health challenge that requires ongoing monitoring and response efforts. The continued presence of a minimally affected population of this endemic even shows epidemic waves which are characterized by repeated cycles of outbreaks and warning of infections; this is observed with the changes in community wise prevalence of the disease as the severity and spread of these waves was lesser than the first two waves.

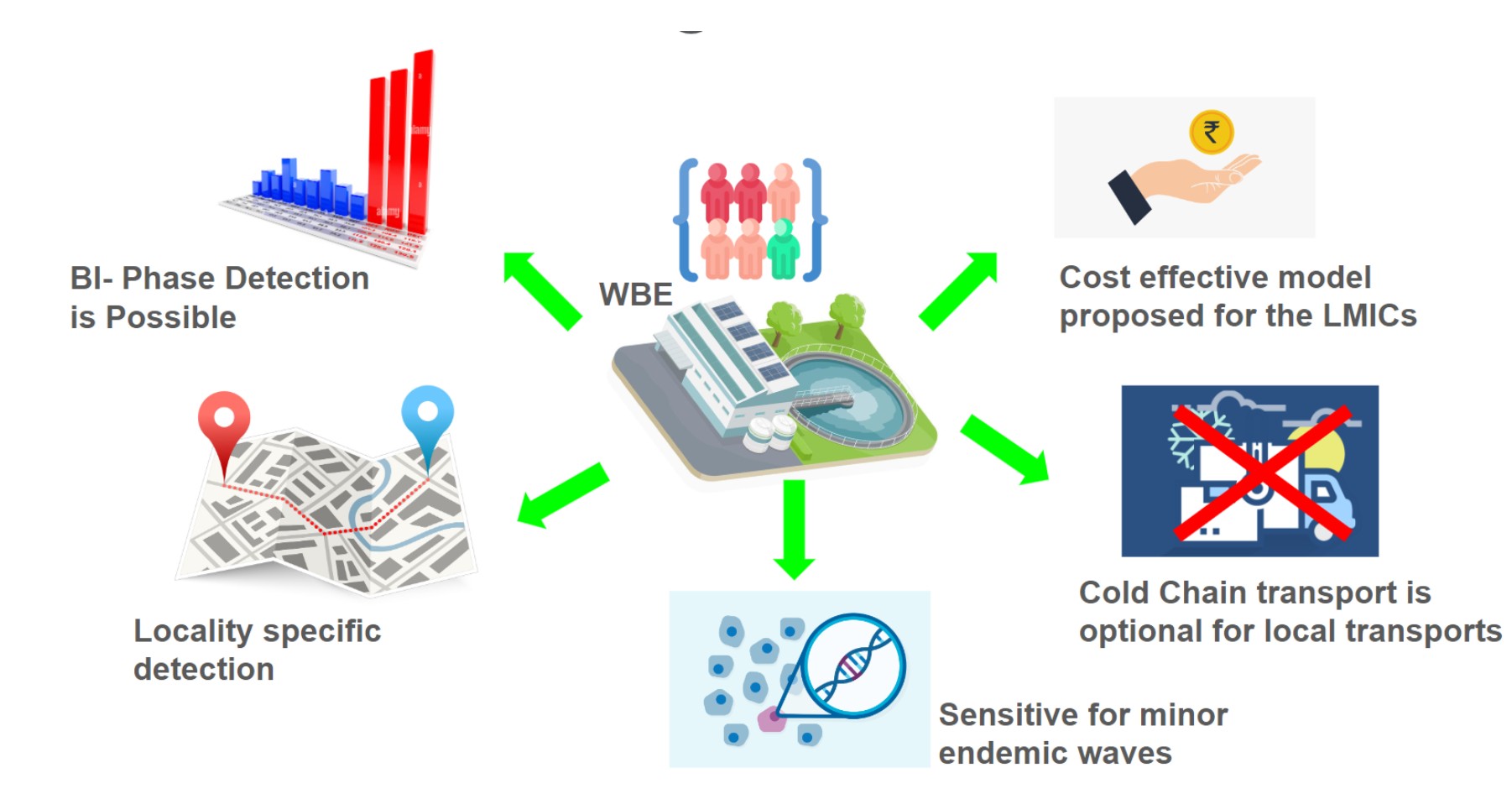

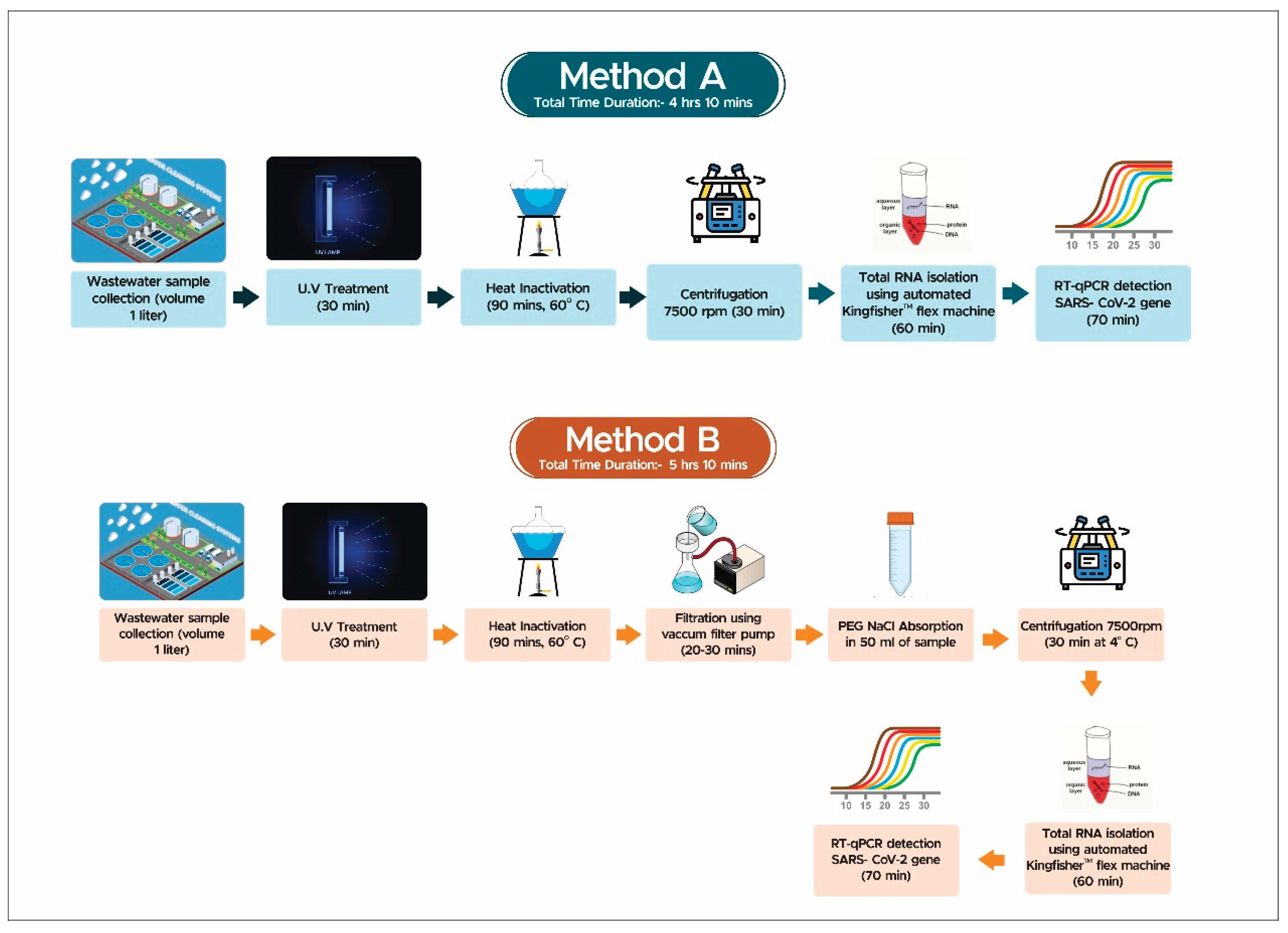

The present study aimed to validate the WBE based approach for endemic and epidemic surveillance and find ways of optimizing such surveillance protocols for low- and middle-income country infrastructures which can be employed continuously in a cost-effective manner. Thus, the paradigm of a tier II city -Jaipur was taken for this purpose. The study spanned through the time points having absence and reported presence of major and minor COVID-19 waves in the city and compared the efficiency of different protocols and detection kits. Based on the findings of this comparison, it is proposed that a bi-phase detection approach can be adapted as a cost-effective method for continued utilization of WBE in monitoring and prediction of endemic or epidemics waves of pathogens even during “off-seasons”. This approach involves a combination of two phases of analysis of wastewater samples. In the first phase, samples are directly processed for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR without any pre-processing. The other method involves pre-processing the samples by centrifugation, filtration, and PEG adsorption before RNA extraction (

Figure 1 in the method section illustrates the details).

2. Experimental Methodology

2.1. Sample Collection and Transportation

In this study, influent samples were collected from nine municipal wastewater treatment plants located in Jaipur, covering approximately 60-70% of the city's sewerage network, for monitoring SARS-CoV-2 (

Table 1). The sampling was done longitudinally, with samples collected weekly between June 8th, 2021 and July 8th, 2022. All samples were collected as one-liter grabs in sterile bottles and transported to the Environmental Biotechnology Laboratory at Dr. B. Lal Institute of Biotechnology, Jaipur, for further analysis. During the sampling process, appropriate precautions, including ambient temperature, were taken into consideration, and personnel wore standard personal protective equipment (PPE) throughout the sampling process. Additionally, the samples were stored at 4°C for 24 hours before analysis, as previously described [

7].

2.2. Sample Processing for SARS-CoV-2 Detection via RT-qPCR

Samples were processed according to two different methods. For the direct method (Method A) the protocol described by [

10,

11] was slightly modified for the isolation of RNA from wastewater samples. After centrifuging 1 ml of the sample at 7,000 rpm for 30 minutes to remove debris and unwanted materials, the supernatant was processed for RNA extraction as per previous [

11] protocol. The automated KingFisher™ Flex machine was used to extract viral RNA from the processed wastewater samples via the MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems), following the manufacturer's instructions and internal process control (MS2 phage). The eluted RNA was then stored at -20°C for further use.

The PEG concentration method (Method B) involved surface sterilization of the samples with UV treatment for 30 minutes, followed by manual mixing. The samples were then heat-inactivated at 60°C for 90 minutes to eliminate the virus. After heat inactivation, the samples were filtered through a 0.45μm membrane using a vacuum filter assembly. The filtrate of each sample was then mixed with 0.9g sodium chloride (NaCl) and 4g polyethylene glycol (PEG) in a fresh 50ml falcon by gentle manual mixing. The samples containing PEG and NaCl were then centrifuged at 4°C for 30 minutes at 7000 rpm. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 1X Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) and then processed for manual RNA extraction. The total RNA extraction from the concentrated viral sample of sewage was performed manually using the ZymoBIOMICS®96 MagBead DNA/RNA Kit R2136 in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. The easy MAG extractor stand was used for RNA extraction, and the extracted RNA was eluted in a 100 μl elution buffer [

7].

2.3. RT-PCR Based Qualitative and Quantitative Detection of Viral Genome

The presence and amount of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the extracted wastewater RNA samples were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively using two different commercial RT-PCR kits on a CFX 96 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). For qualitative detection, Kit 1, AllplexTM 2019-nCoV Assay RT-PCR was used, targeting the E gene, N gene, and RdRp gene with internal controls on two different fluorophore channels. The RT-PCR reaction mixture was prepared by mixing 11 μL RNA with 14 μL master mix, followed by thermal cycling and detection using Bio-Rad CFX Manager software. The presence of at least two genes (out of three) with Ct values was considered positive.

For quantitative detection, Kit 2, InnoDetect One Step COVID-19, was used. Two different plasmid DNAs were used to prepare a standard curve ranging from 10 pg/μL to 0.01 fg/μL for N gene and ORF1ab gene. The kit used three different fluorophore channels for individual gene identification. The RT-PCR reaction mixture was prepared using the master mix, primer probe, and isolated RNA, followed by thermal cycling and detection. The samples with the quantitative presence of any of the two genes (N or ORF1ab) or both the genes were considered positive. Positive samples were selected for further processing [

2,

7]. MS2 phage was taken as internal process control, template positive control and template negative controls were set along with every run in qualitative and quantitative detection.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A paired T -Test analysis was done to evaluate the efficiency of the two methods and two tailed, unequal variance T -Test was performed on the samples collected at the cold chain and the ambient normal temperatures using MS excel for statistical analysis. P values were calculated by using the data analysis package of the Excel in MS office 2007.

3. Results & Discussions

3.1. WBE Approach Could Catch Epidemic Cycles Even in Absence of Clinical Detection

Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) is a valuable approach for monitoring epidemic cycles, even in the absence of clinical samples detection awareness or when the number of reported cases is low. This is because wastewater can provide an aggregate sample of the population, including both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals who may not seek medical attention or clinical confirmation of their infection.

Since the pattern of epidemic is different from that of a pandemic in terms of origin of the infection, kinetics and the intensity of spread; the approaches to detect these two, might be different. Epidemics usually have multiple focal points of origin, and the disease spreads radially through the community from those points. In contrast, pandemics typically have a single point of origin and spread globally. This means that monitoring for epidemics may require a more localized approach, while monitoring for pandemics may require a more global approach. The agents that cause epidemics are often not new to the population, and there may be some level of acquired immunity in the community. This can result in lower peak infections and less severe outbreaks compared to pandemics. The goals of monitoring epidemics may differ from those of monitoring pandemics. For example, in an epidemic, the priority may be to quickly identify and contain the outbreak preventing it from spreading. In a pandemic however, the goal may be to track the spread and kinetics of the disease globally and accordingly develop interventions to mitigate the impact of the disease on public health and society. Overall, the approaches to detecting and monitoring epidemics and pandemics may differ based on the unique characteristics of each type of outbreak.

The present study aimed to investigate whether WBE is capable of detecting the dynamics of a typical epidemic. To achieve this, wastewater samples were collected weekly from different locations in the city from August 2021 to June 2022. This period covered the monitoring of wastewater samples after the second wave of COVID-19 had declined in the city. By analysing the wastewater samples during this period, the study aimed to identify any potential epidemic cycles or trends that could be useful for monitoring and controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the city.

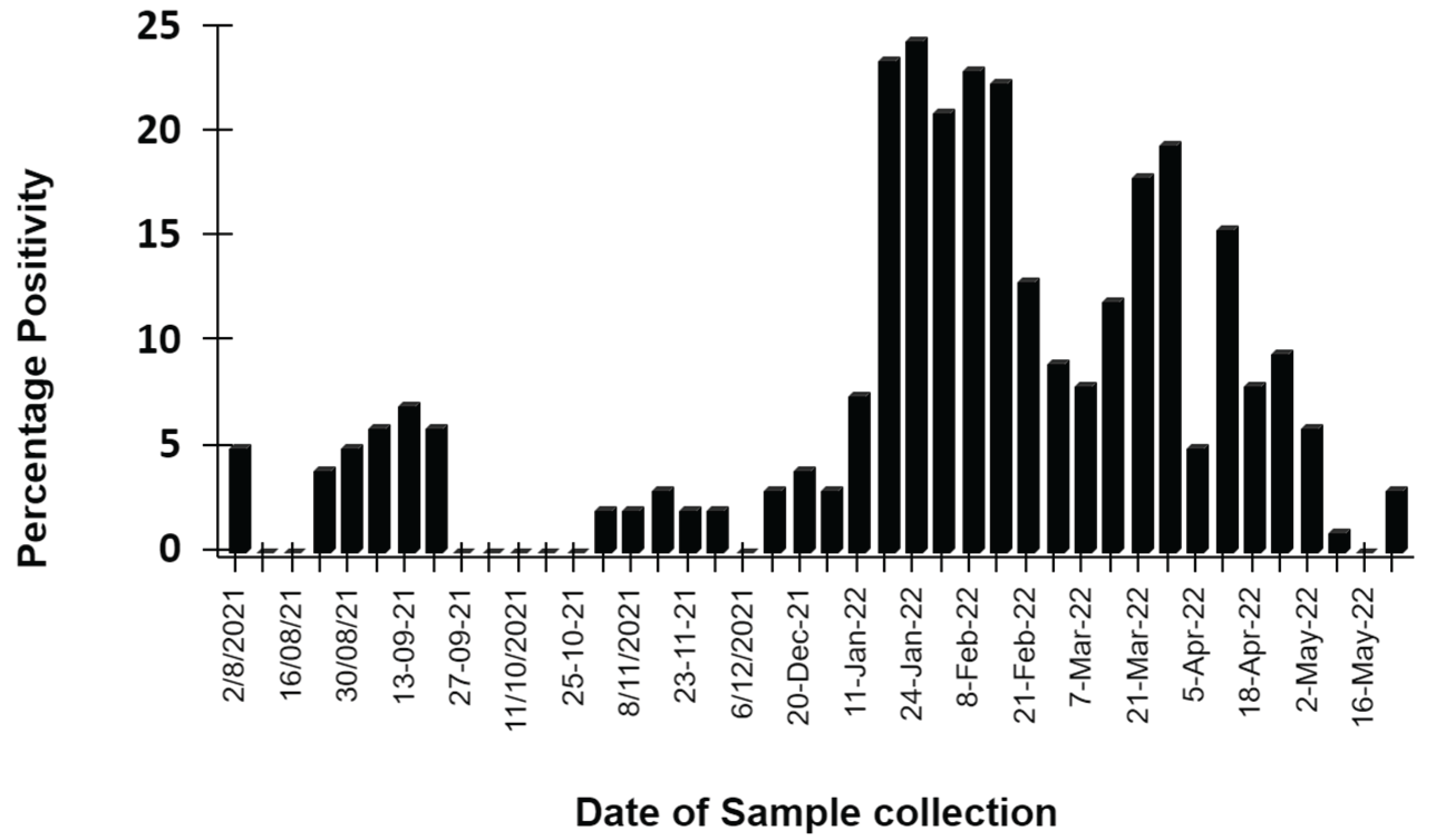

The majority of the population in the city where the study was conducted had either been vaccinated or had developed immunity due to prior infection with COVID-19. As a result, there was a decrease in the severity of symptoms and hospitalizations, leading to a relaxation of government regulations and a decrease in the necessity of testing. The use of home testing kits was also allowed, which further led to a decrease in reported cases. However, to check the sensitivity of WBE for epidemic monitoring, the presence of viral genome was checked in wastewater samples. As shown in

Figure 2, the study found that there were two minor waves of COVID-19 spread, with a low third wave observed between December 2021 to February 2022, and a minor spike observed in August to September 2021. These waves were not publicly reported by the city health care system. Although the caseload did increase during these waves, the positive samples tested from all across the city percent out of all tested untreated wastewater samples for a given day could not even exceed 25%. Furthermore, the overall intensity was much lower than that of the second wave, and there was a decrease in mortality and genome load (Supplementary table S1). This decrease in intensity could be in part attributed to a wide-scale vaccination drive which had ensured that millions of residents had received at least one dose of the vaccine before December 2021 and the use of rapid home testing kits, which could have led to decreased testing and reporting.

3.2. Different Phases of Epidemic Cycle Showed Difference in Target Detection

It is possible that detection of target sequences by RT-qPCR in the WBE approach could vary during different phases of epidemic cycles. This could be owing to factors such as changes in the prevalence and distribution of the virus in the population, differences in the viral load shed in feces during different stages of the disease, and differences in the performance of the RT-qPCR assay over time [

12]. However, more research is required to confirm if this is the case.

As mentioned above, the study collected wastewater samples from various sites (Table1) in the city over a period of time when the second wave of COVID-19 had subsided and post-vaccination drive. Out of 755 untreated wastewater samples tested, 475 were found to be positive for COVID-19 viral genome. The highest log values observed during the windows of third and fourth waves were in order of 10

8 copies/L while the lowest were in order of 10

4 copies/L. Different local infection wave patterns were observed in different communities, and the WBE approach was capable of distinguishing local, sub-city, or community-level disease spread cycles. The details of positive samples detected are given in

Table 1.

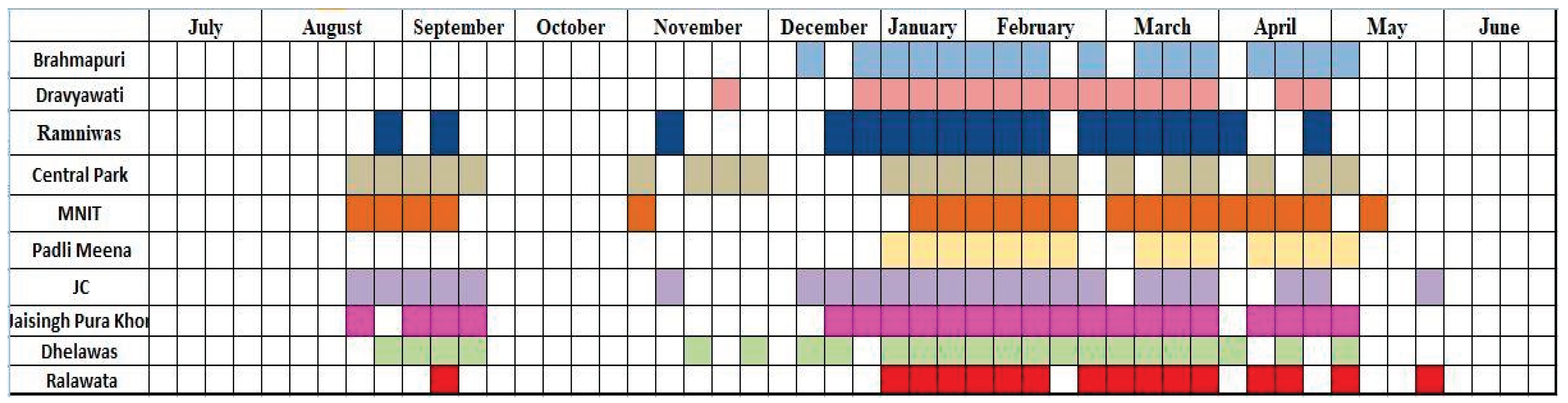

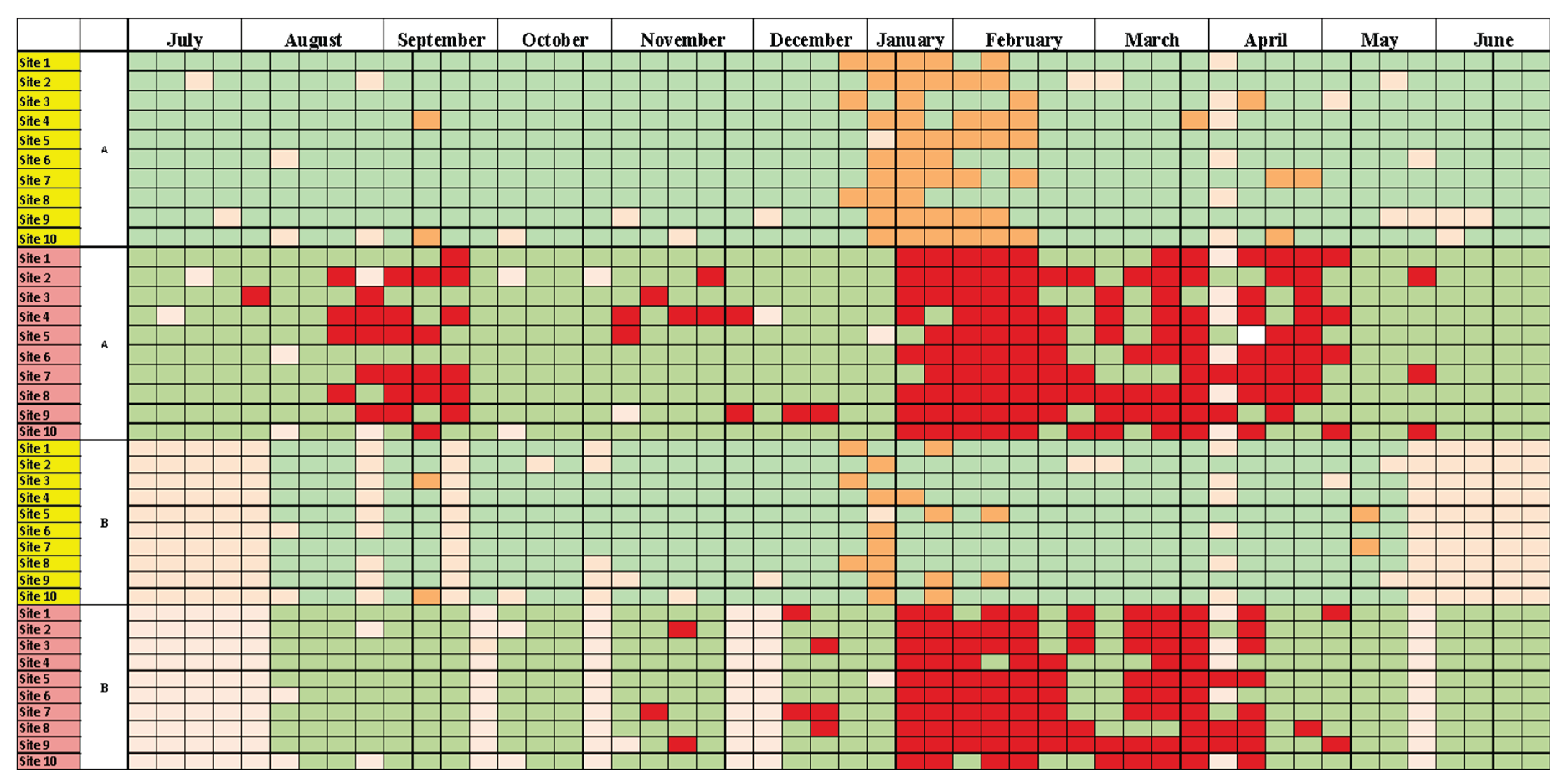

Like a typical epidemic, several local infection wave patterns were observed in different communities as shown in

Figure 3. It was observed that although the third wave of COVID-19 showed its presence all across the city, the minor spike observed during August and September did not spread evenly to all localities of the city. For example, Sites 1, 2 and 6 remained unaffected by this spike while sites 3 and 10 were only minimally affected. This pattern was different from that of sites 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9 where the spike was very consistently detected. This result highlights the local exposures and viral spreads in the city as each of these sites cater to a different catchment area and interestingly, the sites behaving similar are not geographically located near to each other (

Figure 3). This pattern clearly shows that WBE is capable of distinguishing local, sub-city or community level disease spread cycles and is not limited to city hotspot detection.

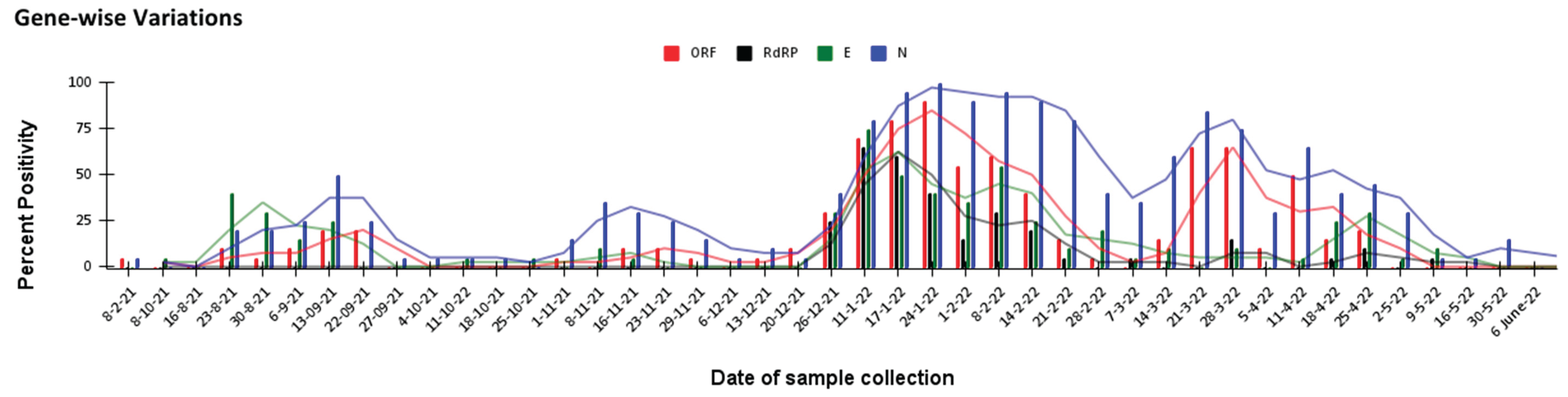

In the RT-PCR testing it was observed that during a minor third and a mild fourth waves in the city all the tested targets did not show the same detection pattern during the span of wastewater monitoring. Some genetic targets like ORF1ab and N were detected during more phases of epidemic cycle than others like E, which showed less detection during the period between two different waves or RdRP, which was not detected in any phase except for the peak duration of the fourth wave in the city (

Figure 4). This observation may be explained easily by the sensitivity of different targets used; alternatively, this pattern may also be an indicator of some key variables affecting the kinetics of pathogen spread as all the targets belong to genes, which have different functions during viral life cycle [

13]. Regardless of the aforementioned reason, the data highlight the importance of checking for multiple target regions to get a comprehensive picture from the wastewater monitoring.

Although, in contrast to the patients’ testing, where the presence of multiple positive targets or Ct values lower than 35 is considered to be a good cut-off for considering a sample as positive, the detection of even one target gene in wastewater should be considered a “low infection number” possibility in the community. It has been observed that during the rise and peak of infection waves more than one target may be detected by RT-PCR, while in samples collected from time point’s right after these phases and until the next rise usually tested positive for only one target. This indicates that there could be a possibility that any wastewater sample from a community with a low number of infected people might only be retaining degraded or very diluted representation of pathogen genomes in the community wastewater, thus making it easy to miss intact genomes during collection [

12].

Although monitoring is only useful on untreated wastewater from a community, the study looked at the presence of genome load in treated wastewater as an indicator of health risk. It was observed that as compared to previously reported data [

2,

10] there were more numbers of effluent samples detected positive with the genome load of SARS-CoV-2 than observed during initial phases of COVID-19 spread. It was observed that as compared to influent samples where N and ORF genes could be quantified in 29.89% and 18.59% respectively; percentages of positive effluents were less (25.48% and 15.71% respectively). One possible reason for such observation could be the tendency of viral particles or genome copies to show retention at various steps of the treatment plants leading to their slow release at later time [

14]. Since there is still a lack of evidence about spreading COVID-19 through treated wastewater positive for viral genome, it can be safely assumed that SARS-CoV-2 in particular poses minimal health risk in treated wastewater. However, this is an observation worth exploring in case of other pathogenic causal agents of epidemics which might be present in treated wastewater.

3.3. Impact of Kit Sensitivity and Preprocessing Methods on Target Detection

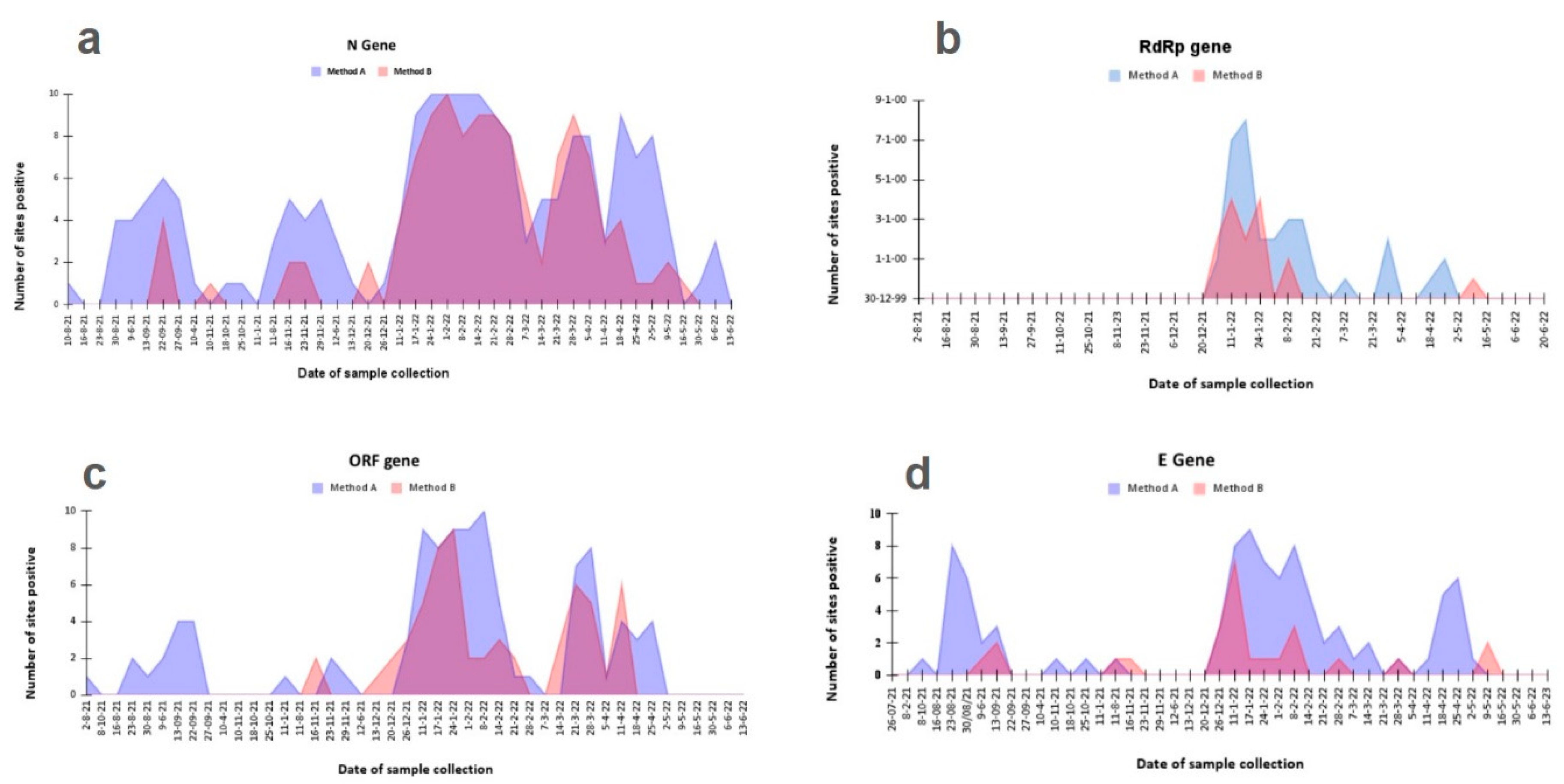

As discussed in section 3.2, a difference in target detection was observed during different phases. These observations led to the question of impact of other variables in this detection. In order to investigate this, variables like target sensitivity and the impact of PCR inhibition (owing to difference in pre-processing treatments of sample), two different kits were used targeting different four different genes (Kit 1= E gene, RdRp gene and N gene, Kit 2= N gene, ORF gene) with one gene as a common target. Both of these kits were used to test for samples processed with two different preprocessing approaches (As described in the methods section). It is expected that a sample where viral particles are concentrated will give better yields and will be overall a more sensitive approach for detection of viral presence. It was however observed that percentage positivity of the samples detected by either approach was not significantly different.

Although method B (which included concentration of the sample) detected a mere 2% more positive samples per tested sample (which was statistically insignificant); two interesting observations were made in the data. Firstly, there is a log reduction of an order of 10

1 to 10

2 in viral copy numbers detected per litre. Secondly, it was observed that whenever there was a period of low case reports in the city Method A (which did not include concentration) seemed to be detecting better than Method B which failed to detect viral presence despite concentration of the sample (

Figure 5). This observation can be explained by one or both of the following explanations- a) increasing filtration steps to remove gravel and grit also led to removal of viral particles or b) concentrating the sample by adsorption also concentrated some inhibitors which hampered the RT-PCR based detections in case of high inhibitor to genome ratio in the processed sample. Since method A showed better detection at low caseload time points, it was important to understand whether this behaviour was somehow affecting the detection pattern of target genes observed (

Figure 4). Upon looking at the specific method wise gene detection it was found that the observation differences were not limited to just the gene target tested but the pattern of detection was also unique for each Method for every gene (

Figure 6).

Moreover, although one of the two kits used (Kit 2) was found to be more sensitive overall; samples with preprocessing through Method A it could be specially detected through kit 2 during the time window with less caseload in the community (

Figure 5). This indicates that the choice of kit as well as preprocessing approach can have an impact on the detection of viral presence in wastewater.

3.4. Local Monitoring Could Potentially Eliminate the Need for Cold Chain Transport.

Cold chain transportation is a standard practice for collecting and transporting the samples related to wastewater-based epidemiology. However, to maintain a cold chain transport is an investment in itself and may add up to a large amount in day-to-day operations it should be acknowledged that this practice can incur substantial costs. Since the study focussed on variables affecting the regular monitoring of the endemic, cold chain transport which is currently recognized as a crucial factor in ensuring precise COVID-19 detection was also investigated. Opportunistically the study is based in Rajasthan, where environmental conditions exhibit extreme high ambient temperatures. Our investigation looked into the efficiency of sample transportation and asked if it would compromise the sensitivity of COVID-19 detection if samples were transferred on the ambient temperatures instead of the cold chain?

To check this, we designed a sampling protocol encompassing all the sites described above, (

Table 1). Upon collection, the samples' temperature was immediately recorded on-site (29 °C to 34 °C), Subsequently, temperature measurements were again acquired upon the samples' arrival at the Environmental Biotechnology Laboratory, located at Dr. B. Lal Institute of Biotechnology, Jaipur, followed by transportation through both cold-chain (which was recorded between 23° C to 32.5 °C) and ambient temperature methods (which was 29 °C to 34 °C). The ensuing procedures remained consistent with the aforementioned methodology.

Interestingly, experimental results indicated that there was no statistically significant difference between the two methods under investigation when the samples were transported locally (

Table 2). Both methods exhibited similar behaviour in terms of Positivity and log Numbers. T-test analysis revealed a p-value of 0.44, which is greater than the significance level of 0.05 (

Supplementary Table S2).

Based on the study findings, it is proposed that since there is no significant difference in the positivity of sample transportation between the cold chain and normal temperature methods protocols in distances within a city, using the ambient temperature transport method should be adapted as a cost-efficient alternative to the cold chain approach. This would increase the affordability of WBE for the cities which currently do not have elaborate sampling and processing setups for such monitoring.

3.4. Epidemic Monitoring Can Be Pragmatically and Cost-Effectively Applied as a Bi-Phase Model

Since the previous results showed that there was no significant difference in the detection by Method A or Method B and that they perform nearly the same, cost calculation was done for both the approaches. Considering the only difference in these approaches was in pre-processing steps and semi-automation for RNA extraction the cost of these two were compared. It was found that preprocessing of Method B alone could take the cost of this approach to more than 330 times that of Method A.

Given that Method B is only ever so slightly better (39.54% by method B Vs 37.35% by method A) in target detection it does not seem to be a pragmatic yearlong epidemic monitoring approach for any country where resources are limited and can be better utilized. Further the cost incurred (additional 2-3% to reagents cost) in maintaining a cold chain transport within local distances may be optional and invested only when more sensitivity in detection needs to be ensured. Since, epidemics are cyclic and rise from within the community yearlong monitoring is also equally vital for disease management. Therefore, it is proposed that WBE is used as a monitoring system in parallel to the sentinel system, using the preprocessing steps of Method A. Method B can thus be employed as soon as first signs of epidemic detection as an “urgent response protocol” against the epidemic on rise. Since this strategy will allow a yearlong monitoring through WBE, this strategy will not be dependent on patient cohorts to show symptoms or to be reported to hospitals or sentinel clinics. Additionally, looking out for more than one target in a pathogen from community wastewater will ensure an early detection which is the major advantage of using the WBE (

Figure 4). This bi-phase monitoring approach will give a comprehensive epidemic monitoring in a cost-efficient manner.

Therefore, the study suggests using Method A for year-long monitoring of wastewater as a parallel system to the sentinel system, and switching to Method B as an "urgent response protocol" during epidemics. This bi-phase monitoring approach will provide a cost-efficient and comprehensive epidemic monitoring system.

4. Conclusions

The utilization of WBE has emerged as a promising strategy for monitoring epidemics, offering a cost-effective and practical approach. The recommendation for adopting a random monitoring technique coupled with a direct method of preprocessing stands as a crucial enhancement. Implementing an "urgent response" strategy, triggered upon a positive result from the direct method, presents an opportunity to allocate dedicated resources at an opportune moment, optimizing the viability and usability of WBE in epidemic surveillance. Distinguishing between the dynamics of epidemics and pandemics, including varied spread patterns, multiple origin points, and differing population immunity levels, was a crucial aspect of this research's exploration. This comprehensive approach enabled the identification of both minor fluctuations and significant surges in epidemic waves distinguishing between endemic patterns of different localities in the city. Notably, the amalgamation of the direct method with a quantitative kit was determined as the most sensitive approach for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Cold chain transportation, another critical component which is conventional to the WBE while being quite costly. The study result provides evidence that the detection of percentage positivity is not significantly different without or with local cold chain transport of samples. This gives the LMIC setups an option to skip such investments for establishment of the WBE surveillance. In conclusion, this study's recommendations offer a pragmatic and adaptable framework for leveraging WBE in epidemic surveillance, potentially revolutionizing how we proactively monitor and respond to emerging health crises.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization- AN, SA, ABG Data curation- AN, EM , Formal analysis- AK, AN, Funding acquisition- SA, Investigation- SA, AN, Methodology- EM, TP, KS, SKS, Project administration-SA, Resources-SA, SKS, Supervision- AN, Validation- EM, Visualization- AN, EM, Writing – original draft- AN, EM, Writing – review and editing- SA, AN.

Funding

The present research study is funded by the Internal Mural Grants (IMG) from Institutional Research Scientific Committee of the institute Dr. B. Lal Institute of Biotechnology, Jaipur, BIBT/ISRC/IMG-2021-22/038 and partially funded under the SERB special project grant CVD/2022/000021 titled “Early Detection, Surveillance, and prevention of Communicable Viral diseases in Jaipur city: a Wastewater-Based Epidemiological study for COVID-19 (DISCOVER- WBE)".

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was done with all the necessary institutional ethical permissions in accordance with the ICMR Govt. of India guidelines. Written consents were obtained from the sites which were sampled for wastewater.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The study group would like to acknowledge the constant support received from Dr. B. Lal Gupta (Dr. B. Lal Institute of Biotechnology, Jaipur) and Dr. Aparna Datta for inspiring this research and providing daily motivation to work faster.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumblathan, T.; Liu, Y.; Uppal, G.K.; Hrudey, S.E.; Li, X.F. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology for Community Monitoring of SARS-CoV-2: Progress and Challenges. ACS environmental Au 2021, 1, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Nag, A.; Kalra, A.; Sinha, V.; Meena, E.; Saxena, S.; Sutaria, D.; Kaur, M.; Pamnani, T.; Sharma, K.; Saxena, S.; Shrivastava, S.K.; Gupta, A.B.; Li, X.; Jiang, G. Successful application of wastewater-based epidemiology in prediction and monitoring of the second wave of COVID-19 with fragmented sewerage systems-a case study of Jaipur (India). Environmental monitoring and assessment 2022, 194, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, R.; Roknuzzaman, A.S.M. ; Nazmunnahar; Shahriar, M. ; Hossain, M.J.; Islam, M.R. The WHO has declared the end of pandemic phase of COVID-19: Way to come back in the normal life. Health Science Reports 2023, 6, e1544. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Tscharke, B.; Bertsch, P.M.; Bibby, K.; Bivins, A.; Choi, P.; Mueller, J. F. SARS-CoV-2 RNA monitoring in wastewater as a potential early warning system for COVID-19 transmission in the community: A temporal case study. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 761, 144216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra, A.; Botello, J.; Pinilla, A.; Urrutia, J.I.; Canora, J.; Sánchez, J.; Flores, J. SARS-CoV-2 detection in wastewater as an early warning indicator for COVID-19 pandemic. Madrid region case study. Environmental research 2022, 203, 111852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Angel, N.; Edson, J.; Bibby, K.; Bivins, A.; O'Brien, J.W.; Mueller, J. F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 728, 138764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nag, A.; Arora, S.; Sinha, V.; Meena, E.; Sutaria, D.; Gupta, A.B.; Medicherla, K. M. Monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 variants by wastewater-based surveillance as a sustainable and pragmatic approach—a case study of Jaipur (India). Water 2020, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, B.A.; Kaya, D.; Kelly, C.; Williamson, K.J.; Alegre, D.; Bachhuber, S.M.; Radniecki, T.S. Evaluation of a wastewater-based epidemiological approach to estimate the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infections and the detection of viral variants in disparate Oregon communities at city and neighborhood scales. Environmental health perspectives 2022, 130, 067010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, R.M.; Sorensen, R.J.; Pigott, D.M.; Bisignano, C.; Carter, A.; Amlag, J.O.; Murray, C.J. Estimating global, regional, and national daily and cumulative infections with SARS-CoV-2 through Nov 14, 2021: a statistical analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 2351–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Nag, A.; Sethi, J.; Rajvanshi, J.; Saxena, S.; Shrivastava, S.K.; Gupta, A. B. Sewage surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 genome as a useful wastewater based epidemiology (WBE) tracking tool in India. Water Science and Technology 2020, 82, 2823–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, S.; Nag, A.; Rajpal, A.; Tyagi, V.K.; Tiwari, S.B.; Sethi, J.; Kumar, M. Imprints of lockdown and treatment processes on the wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2: a curious case of fourteen plants in northern India. Water 2021, 13, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Younis, N.M.; Dhahir, N.M.; Hussain, K.N. Acceptance of Covid-19 vaccine among nursing students of Mosul University, Iraq. Rawal Medical Journal 2022, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Au, K.K.; Chen, C.; Chan, Y.M.; Wong, W.W.S.; Lv, H.; Mok, C.K.P.; Chow, C.K. Tracking the Transcription Kinetic of SARS-CoV-2 in Human Cells by Reverse Transcription-Droplet Digital PCR. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Bivins, A.; Stephens, M.; Metcalfe, S.; Smith, W.J.; Sirikanchana, K.; Simpson, S.L. Occurrence of multiple respiratory viruses in wastewater in Queensland, Australia: Potential for community disease surveillance. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 864, 161023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).