Methods Used in the Review

This study used the scientific databases PubMed, SciFinder, and Google Scholar for a literature search of relevant studies that contained the keywords “skin diseases”, “artemisia species”, “skin cancer”, “artemisinin”, “antibacterial”, “dermatology”, “skin”, and “skin disorders”. All search terms were used in various combinations, and studies were screened for relevance based on their abstracts. A review of studies written in English and Russian languages were considered. The bibliographical analysis indicated a total of 26 genera belonging to Artemisia family that was used against skin related diseases.

Introduction

Skin diseases affect more than 20% of the world’s population, exercising a considerable burden on public health [

1,

2]. The economic implications of skin conditions are significant, particularly with human skin wounds as a growing concern [

3]. In addition, the psychological impact of these diseases is deep, influences mortality in mental disorders [

4]. The incidence of non -melanoma skin cancer is increasing worldwide [

5], while psoriasis remains frequent and widely studied [

6]. World Health Organization emphasizes the importance of addressing environmental risks to mitigate health loads [

7]. As treatments evolve, the understanding of adverse effects remains critical [

8,

9].

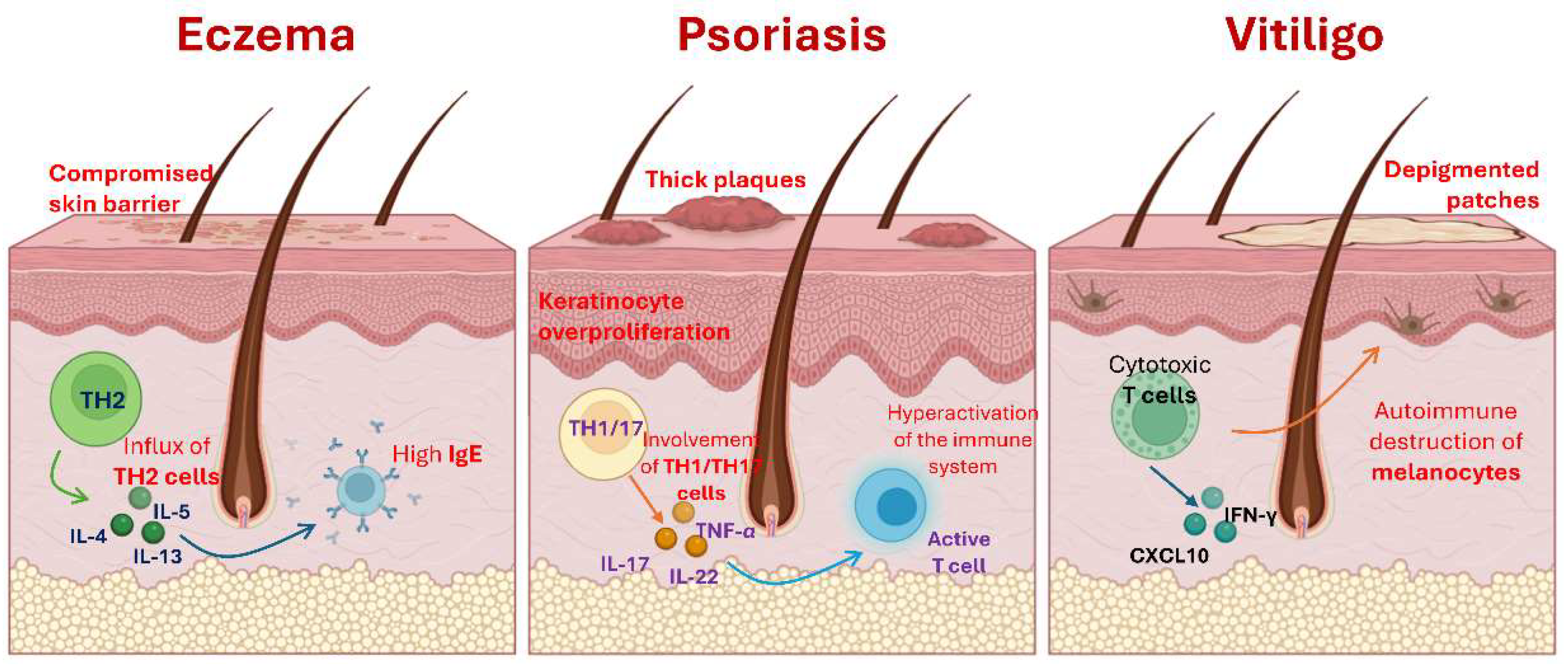

Eczema, psoriasis and vitiligo are prevailing skin conditions that significantly affect the quality of life of patients. These disorders arise from complex interactions between genetic, environmental and immunological factors, which leads to abnormal skin responses. The pathophysiology of eczema, mainly identified as atopic dermatitis, implies a compromised skin barrier and an abnormal immune response characterized by high levels of IgE and an influx of TH2 cells [

10]. Psoriasis, in contrast, is characterized by hyperactivation of the immune system, particularly that involves TH1 and TH17, leading to a greater proliferation of keratinocytes [

11]. Vitiligo is considered an autoimmune disorder where there is a loss of melanocytes due to a deregulated immune system that addresses these pigment producing cells (

Figure 1) [

12].

The prevalence of these skin conditions varies significantly between populations. It is reported that the eczema affects approximately 10-20% of children and 1-3% of adults [

13]. Psoriasis occurs in approximately 2-3% of the population, with implications for life for many affected individuals [

14]. Vitiligo impacts between 0.5-2% of the global population, with variations based on ethnicity and geographical distribution [

15]. These statistics underline the generalized nature of these conditions and the need for effective treatment strategies to relieve the anguish they cause.

Eczema treatment options generally involve topical moisturizing and corticosteroid agents to control inflammation and restore the skin barrier [

16]. Systemic therapies, including immunosuppressants, are reserved for severe cases. In psoriasis, patients can benefit from topical treatments, phototherapy or systemic medications, including biological ones that go to specific immune paths such as IL-17 and IL-23 [

17]. Vitiligo treatments often include topical corticosteroids, phototherapy with narrow band UVB and emerging therapies such as immune modulators [

18]. However, responses to treatments can be variable, and not all patients achieve satisfactory results.

In this review are given the types of Artemisia that have potential for use treatment in skin diseases and cosmetics. Ethnopharmacological studies reveal that the components of Artemisia species can effectively modulate skin conditions through various biochemical paths, indicating their role as promising candidates for the development of natural dermatological therapies.

Historical Background of Artemisia in the Treatment of Skin Diseases

About 2,500 plants known to have been used in traditional medicine in Russia and Central Asia, about 1,000 have been used to treat various skin diseases. Some plants, however, are much more widely used to treat skin diseases than others, and about 300 medicinal plants are known to have been frequently used in prescription and over-the-counter pharmaceuticals in post-Soviet states. The genus

Artemisia (family: Asteraceae) encompasses a diverse group of plants widely distributed across temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Comprising over 500 species,

Artemisia is recognized for its extensive medicinal properties, which have been traditionally exploited in various cultures. Russia and China exhibit the highest species diversity. In Kazakhstan, 81 species have been documented, including 19 endemic species, with 34 of these occurring within Central Kazakhstan [

19,

20,

21]. The genus has a significant historical and cultural value in traditional medicine, in particular for the treatment of skin diseases. The effectiveness of

Artemisia species in the management of skin diseases can be attributed to their rich phytochemical composition. Compounds such as flavonoids, terpenoids and essential oils have notable anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiseptic and antioxidant properties [

22]. These bioactive constituents promote the healing of wounds and reduce the symptoms associated with various dermatological conditions, including eczema and psoriasis. For example, traditional methods often involve the topical application of extracts or plant material finely on the ground in affected areas, which has demonstrated significant health benefits in clinical observations [

23]. Current research reaffirms the relevance of

Artemisia in therapies based on contemporary plants, in particular as a natural alternative to synthetic pharmaceuticals. In recent years, studies have highlighted not only traditional uses but also the pharmacological properties of

Artemisia species, supporting their inclusion in modern treatments for skin evils [

24]. In addition, the exploration of

Artemisia’s potential as a source of cosmetic raw materials highlights its versatility and its meaning in medicinal and beauty applications [

25].

Table 1.

Traditionally used Artemisia species in skin disorders.

Table 1.

Traditionally used Artemisia species in skin disorders.

| Species name |

Part used |

Traditional use |

Country |

Reference |

|

Artemisia iwayomogi

|

|

skin whitening,

itchy skin |

Korean folk medicine

|

[26] |

| Artemisia argyi |

|

itchy skin,

eczema |

Traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean medicine |

[27] |

| Artemisia princeps |

|

itchy skin,

eczema |

Traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean medicine |

[27] |

| Artemisia herba-alba |

essential oil from the leaves and the thin branches |

local skin infections |

|

[28] |

| |

skin diseases, scabies |

Jordanian traditional medicine

|

[29] |

| Artemisia absinthium |

Herb |

boils, wounds, and bruises |

Poland and Ukraine |

[30] |

| |

ulcerative sores, eczema, purulent scabies |

|

[31] |

| Artemisia vulgaris |

|

ulcerative sores, eczema, purulent scabies |

|

[31] |

| Artemisia annua |

|

eczema, scabies, sores |

Traditional Chinese medicine |

[32] |

| Artemisia arborescens |

|

Psoriasis |

Southern Italy |

[33] |

| Artemisia dracunculus |

|

skin wounds, irritations, allergic rashes, and dermatitis |

Asia, Russia |

[34] |

| Artemisia capillaris |

|

skin inflammation |

Traditional Chinese medicine |

[35] |

| Artemisia anomala |

|

wound-curing agent |

Traditional Chinese medicine |

[36] |

| Artemisia apiacea |

|

eczema and jaundice |

Traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean medicine |

[37] |

| Artemisia asiatica |

|

skin health and increase the elasticity of skin |

Traditional Korean medicine |

[38] |

| Leaves |

carbuncle and boil in skin, itchy skin |

Traditional Chinese medicine |

[38] |

Antibacterial Potential of Artemisia Species

There has been a surge in interest in medicinal plants that have antimicrobial or antibacterial properties as a means of combating antibiotic-resistant infections, which have become an increasingly serious health threat worldwide. There is an increasing recognition that antibiotic resistance represents a significant public health issue, with genetic mutations and horizontal gene transfer providing mechanisms through which pathogenic microorganisms acquire resistance to conventional antibiotics [

39,

40]. In this regard, there is growing interest in the study of natural products derived from plants, which are known to contain a diverse range of bioactive compounds with potent antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral properties that may offer a promising alternative or complementary approach to traditional antibiotic therapy [

41,

42]. These plant-derived compounds featuring the capacity to synthesize enzymes that are capable of tearing apart microbial cell membranes, halting protein production, or inhibiting microbial enzymes is very relevant today. Moreover, the therapeutic effects of these compounds may greatly contribute to reducing the consequences of antibiotic resistance and fighting infections produced by multi-drug resistant bacteria [

43,

44]. Medicinal plants are rich in secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenols, and saponins, which have bacteriostatic effects, inhibiting bacterial growth, or bactericidal effects, directly killing bacteria [

45,

46]. These compounds act on bacterial cell walls, membranes, or genetic material and modulate virulence factors such as biofilm formation and quorum sensing, which are often linked to resistance mechanisms [

47,

48]. Bacterial infections represent a prominent etiological factor in dermatological disorders, ranging from mild irritations to severe systemic diseases [

49]. Among the most prevalent bacterial pathogens,

Streptococcus and

Staphylococcus species are of particular significance in the pathogenesis of various cutaneous infections [

50]. Cutaneous conditions associated with

Streptococcal infections encompass pyoderma, streptoderma, and streptococcal impetigo.

Streptococcus pyogenes is an important cause of skin diseases, in particular impetigo, cellulite and necrotizing fasciitis. This bacterium enters the skin by cuts, blisters or insect bites, leading to various infections [

51]. The pathogenic mechanisms of

S. pyogenes involve the production of toxins and enzymes which can damage skin tissue and escape the immune system [

52].

Staphylococcal infections, predominantly attributed to

Staphylococcus aureus, are associated with a variety of skin conditions, such as impetigo, folliculitis, furuncles, and subcutaneous abscesses [

53]. Furthermore, the production of exfoliative toxins by

S. aureus is implicated in the development of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome [

54]. The clinical manifestations of these infections exhibit a broad spectrum of severity, affecting individuals with both intact and compromised immune systems [

53]. At present,

S. aureus infections are treated with antibiotics, and there has been a dramatic rise in antibiotic-resistant strains, including methicillin-resistant

S. aureus (MRSA) [

55]. This growing resistance emphasizes the need for novel therapeutic strategies, improved infection control measures, and judicious use of existing antibiotics to mitigate the spread and impact of these resistant strains [

39].

Table 2.

Antibacterial and antimicrobial activities of Artemisia species against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria.

Table 2.

Antibacterial and antimicrobial activities of Artemisia species against Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria.

| Species name |

Part used |

Bacteria |

Reference |

| Artemisia scoparia |

essential oil |

S. aureus |

[56] |

Artemisia oliveriana

Artemisia aucheri

|

ethanol extract |

S. aureus |

[57] |

| Artemisia absinthium |

in vivo |

S. aureus

S. pyogenes

|

[58,70] |

| Artemisia afra |

ethanol, methanol, and n-hexane extracts of leaves |

S. aureus |

[59] |

| Artemisia vulgaris |

aqueous, ethanol, petroleum ether and benzene extract of leaves |

S. aureus |

[60] |

Artemisia asiatica

|

essential oil from leaves |

S. aureus

S. pyogenes

|

[61] |

| Artemisia annua |

essential oil |

S. aureus |

[62,63] |

| Artemisia princeps |

ethanol extract |

S. aureus |

[64] |

| Artemisia abrotanum |

ethanol extract |

S. aureus |

[65] |

| Artemisia lerchiana |

infusion and essential oil extract |

S. aureus

Streptococcus

|

[66] |

| Artemisia nilagirica |

essential oil |

S. aureus

S. epidermidis

|

[67] |

|

Artemisiajudaica

|

essential oil |

S. aureus |

[67] |

| Artemisia ifranensis |

essential oil |

S. aureus |

[67] |

|

Artemisiaherba-alba

|

essential oil |

S. aureus |

[68] |

| Artemisia gmelinii |

|

S. aureus

S. epidermidis

S. pyogenes

|

[67] |

| Artemisia fragrans |

essential oil |

S. aureus

S. epidermidis

|

[67] |

| Artemisia dracunculus |

essential oil |

S. aureus

|

[67] |

| Artemisia campestris |

essential oil |

S. aureus

|

[69] |

| Artemisia argyi |

chloroform fraction from aqueous extract

|

S. aureus

|

[67] |

| Artemisia apiacea |

ethanol extract of aerial parts |

S. aureus

|

[67] |

Herbal Plants For Skin Diseases

There are numerous conditions that can adversely affect the skin, with over a thousand potential causes. Nevertheless, dermatological diseases may arise from various factors, including parasitic, bacterial, and fungal infections, as well as immune system deficiencies and prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Many common skin disorders have effective herbal treatment options available. The following section outlines potential Artemisia species.

Atopic Dermatitis

Artemisia annua

Studies have shown the effects of

A. annua aqueous extract on a mice model of atopic dermatitis caused by 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB). Applying DNCB to the ears of BALB/c mice resulted in the development of notable clinical signs that resembled atopic dermatitis, such as redness, swelling, ulceration, and dry, flaky skin. There was a significant reduction in clinical skin parameters following treatment with

A. annua aqueous extract. Also, the treatment significantly reduced the size and weight increase of the spleen caused by DNCB-induced inflammatory alterations in mice, particularly when administered at higher dosages. The mechanism of atopic dermatitis processes has been evaluated because of the relationship between immunological and inflammatory manifestations and the condition’s progression. A study found that the plant extract suppressed symptoms by inhibiting p38 MAPK and NFκB signal pathways. As a result of these observations, it was clear that

A. annua aqueous extract could relieve atopic dermatitis symptoms in mice [

32].

Artemisia capillaris

Artemisia capillaris was assessed for its ability to inhibit inflammatory processes in vitro by assessing of nitric oxide by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and histamine by PMA/A23187-stimulated MC/9 mast cells. As result,

A. capillaris extract dramatically decreased LPS-induced nitric oxide and suppressed histamine synthesis in MC/9 cells stimulated by PA. In vivo evaluation of

A. capillaris extract has been conducted on Nc/Nga mice induced by the house dust mite

Dermatophagoides farinae.

A. capillaris extract was applied externally to mice’s backs and ears for a period of four weeks, and by the third week of treatment, the severity of dorsal skin and ear lesions had been greatly minimized, indicating a possible therapy for treating symptoms of atopic dermatitis [

71].

Artemisia anomala

There has been a long history of

Artemisia anomala use in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese medicine to treat inflammatory diseases. N

evertheless, there is still a lack of knowledge regarding the mechanisms by which A. anomala can be therapeutically effective in atopic dermatitis. In accordance with this comprehension Yang et al. examined the anti-inflammatory properties of the ethanol extract from A. anomala, especially the effects in a mouse model of DNCB-induced atopic dermatitis and TNF-α/IFN-γ-stimulated HaCaT cells. In contrast to the control group, mice treated with A. anomala ethanol extract had significantly improved skin conditions and considerably reduced epidermal thickness of their dorsal skin. According to this, A. anomala may have potential as a therapy for atopic dermatitis [

36]

.

Artemisia apiacea

Artemisia apiacea ethanol extract was evaluated in vitro and in vivo for its anti-inflammatory properties in HaCaT cells, as well as its potential as an atopic dermatitis treatment in a mouse model induced by DNCB. The results of both analyzes showed that the plant extract regulates the production of cytokines and chemokines through the p38/NF-κB pathway, and also relieves symptoms of skin lesions in mouse models, such as dorsal skin thickness and ear skin thickness. Although more research is needed, this study points to the fact that

A. apiacea can be used therapeutically in the treatment of atopic dermatitis [

37].

Rosacea

Artemisia lavandulaefolia

There has been recent research investigating

A. lavandulaefolia’s in vitro anti-rosacea properties. It has been demonstrated that two chlorogenic acid isomers isolated from a 40% ethanol extract efficiently suppress the activity of KLK5, which is an essential intermediary of rosacea-related inflammatory and vascular processes. By inhibiting KLK5, LL-37 is converted from inactive cathelicidin into active form, regulating immune function and blood vessel function. In addition, isochlorogenic acids have been studied in terms of their mechanisms of action. Several studies have been conducted on isochlorogenic acids to find out how they act. These findings suggest rosacea may benefit from using the plant as a therapeutic agent [

72].

Eczema

Artemisia annua

There has been a research study looking at the potential therapeutic effects of the aqueous extract of

Artemisia annua against eczema using a 3D in vitro epidermal inflammation model and an in vivo itching model in animals suffering from eczema of topical preparation containing

A. annua aqueous extract. As demonstrated in the study, topical preparation containing

A. annua aqueous extract has a similar antipruritic effect to clinical anti-eczema medication – clobetasol propionate ointment. Consequently, the increase in itch threshold suggests

A. annua aqueous extracts could be anti-eczema and these findings suggest their potential for treatment [

73].

Leishmaniasis

Artemisia dracunculus L.

An ethanolic extract of

Artemisia dracunculus L. dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide was evaluated for its antileishmanial effect in vitro. The experiment was carried out at various parasite concentrations (100–1000 μg/ml) for three days, recording the results every 24 hours, and the corresponding IC50 were 962.03, 688.36 and 585.51 μg/ml. According to repeated-measures analysis,

A. dracunculus extract showed a significant difference in the interaction between concentration and time with P < 0.05. Results from this study suggest that

A. dracunculus extract may be used in conjunction with or as an alternative treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis [

74].

Skin Inflammation

Artemisia capillaris

This study analyzed the literature regarding

Artemisia capillaris which is widely recognized in traditional Chinese medicine for its ability to cure skin inflammatory diseases and anti-inflammatory properties of its components. According to in vitro and in vivo studies, the plant and its several main components (esculetin and quercetin) revealed a potential inhibitory effect against 5-lipoxygenase considering that it is a leukotriene-producing enzyme that is closely associated with inflammation of the skin. Based on these results, inflammatory skin problems of the skin can be effectively treated with the help of this plant material [

35].

Artemisia annua

Artemisia naphtha is a byproduct of artemisinin extraction and an oil consisting of camphor, camphene, p-cymene, eucalyptol, and D-limonene as its main constituents identified by GC-MS. The study demonstrates the anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activity of the oil extract by suppressing the microbial pathogens that cause acne and eczema. Moreover, human clinical trials indicate that

Artemisia naphtha oil is effective in reducing symptoms of acne and eczema when applied locally for 2 weeks at a 1% concentration to acne-prone skin. These in vitro analysis and clinical evidence demonstrate the efficiency in the treatment of problem skin [

75].

Psoriasis

Artemisia arborescens

Bader et al. conducted an experiment on

Artemisia arborescens along with other plants against psoriasis and other skin diseases caused by an unbalanced eicosanoids production. Since dermatological diseases, including psoriasis, are associated with eicosanoids which contribute to innate immunity. The results indicate that

A.ligustica extract enhances the biosynthesis of 15(S)-HETE. Researchers have studied the activation of nuclear factor kappaB (NFκB), and it has been shown to have NFκB inhibitory activity [

76].

UV-Induced Skin Diseases

Artemisia scoparia in a Complex

An investigation of

Artemisia scoparia in conjunction with other herbal plants has been conducted to explore its inhibitory effect on UVB-induced photoaging and the mechanism of action. The complex was prepared from

A. scoparia,

Limonium tetragonum,

Triglochin maritimum and red ginseng root by ethanol (50%) extraction. As a result, the complex demonstrated increased survival in HaCaT cells stimulated with 100 mg/ml tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBHP) which has been found to induce oxidative stress and cell destruction. Moreover, the treatment with the complex resulted in significant increases in collagen synthesis and restoration of collagen and elastin degradation caused by UVB-induced cell damage. The complex inhibits matrix metalloproteinase production by inhibiting MAPK/NFκB signaling at the level of cells [

77].

Artemisia iwayomogi

In light of the fact that skin is subject to oxidative damage when exposed to UV irradiation, researchers have studied polysaccharides, which are powerful antioxidants. The object of the study is polysaccharides from

Artemisia iwayomogi stem obtained by ethanol extraction and fractionation with water. According to the study, polysaccharides from

A. iwayomogi stems showed the highest hydroxyl and superoxide radical scavenging activity with 66.14% and 74.40% at 100 mg per 3 mL concentration. Animal skin tissues were also significantly protected by polysaccharides of

A. iwayomogi against UVB damage caused by protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation. Moreover, the inhibitory effect on reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced in human neutrophils was investigated with 83.14% at 20 μg per well, indicating high ROS scavenging ability [

78].

Artemisia asiatica

Pharmacological studies evaluated protective effect of

Artemisia asiatica ethanol extract on UVB-induced cell death in keratinocytes, as well as cytotoxicity,

moisturizing factors, expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) genes and inflammatory genes as COX-2 in HaCaT, B16F10, HEK293 and NIH3T3 cells. It was found that the plant extract was not cytotoxic and protected various types of cells from UV-mediated cell death, restored procollagen type 1 gene expression, and reduced MMPs and COX-2 expression. Additionally, the expression of tyrosinase and melanin secretion induced by α-MSH at a concentration of 50 μg/ml were also significantly suppressed in B16F10 cells. The cumulative result of research using variety of photoaging methods and studying the mechanisms leads to the fact that the

A. asiatica ethanol extract may become a protective agent for the skin [

38].

Skin Cancer

Artemisia dracunculus L.

Over 3.000 plant species worldwide have anti-cancer properties, which contribute 60% of anti-cancer agents today. Medicinal plants are considered as beneficial chemicals for the making of novel chemotherapeutic drugs and an example of them can be

Artemisia dracunculus L., which has antitumor properties [

79]. One study conducted an in vivo study of the chemopreventive effects of a methanol extract of

A. dracunculus on skin cancer caused by 7,12-dimethylbenzeanthracine in 18 adult male Balb/c mice divided into 3 groups. As results, the treatment revealed significant reduction in tumor incidence, tumor volume and tumor burden after oral administration at a dose of 500 mg/kg/d. In fact, the study was carried out on the basis that three flavonoid compounds, namely rutin, quercetin and kaempferol, were tested for potential effects against skin cancer. Phytochemical profile of

A. dracunculus identified by PHPLC method [

80].

Artemisia annua|Artemisinin

Melanoma is the primary cause of skin cancer-related deaths and one of the most aggressive and unpredictable tumours. Globally, there have been 4-6% annual increases in cases over the past decade. Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone that is the main active ingredient of

Artemisia annua and has received a Nobel Prize as an antimalarial agent [

81]. Artemisinin was hypothesized to be an anticancer drug, and in vitro and in vivo studies supported this hypothesis. Based on the findings of Buommino et al., doses of 100 and 150 μM artemisinin caused a strong inhibition of the growth of A375M cells within 72 hours. Moreover, the chemotactic migration of human melanoma A375M cells was investigated as well as the inhibition mechanism. In consequence, artemisinin inhibits the production of metalloprotease 2 (MMP-2) and strongly inhibits the expression of αv and β3 integrin subunits. A chemotherapeutic agent such as artemisinin may be effective against melanoma, based on the results of this study [

82]. Additionally, there is another study where artemisinin was tested on uveal melanoma and found to be able to prevent metastasis. Throughout the results, artemisinin treatment inhibited uveal melanoma cell migration and invasion, and wound healing decreased in area in the initial knock and completely healed in subsequent knocks. Furthermore, a molecular pathway study of artemisinin showed that it inhibited PI3K, AKT, and mTOR phosphorylation signaling significantly in uveal melanoma cells. In an in vivo study, mice bearing subcutaneous uveal melanoma tumors did not lose weight and the tumors significantly shrank and grew less as a result of receiving artemisinin [

83].

Cosmetics

Artemisia iwayomogi|Anti-Aging Effect

Artemisia iwayomogi is used in Korean traditional medicine for skin whitening, and its UV protection effect is scientifically proven. The whitening and anti-aging effects of

A. iwayomogi were assessed in vitro and in vivo. The study was conducted on five compounds obtained from the ethyl acetate and aqueous fractions. The compounds were tested in vitro to determine antioxidant activity by DPPH and ABTS, whitening effect through tyrosinase inhibition, and anti-wrinkle activity through elastase along with collagenase inhibition. Among isolated components, scopoletin and luteolin demonstrated significant antioxidant and whitening activities while scopolin, scopoletin and luteolin showed resistance to aging. The in vivo test involved preparing a cream containing the plant extract that contained a 1% aqueous solution. Twenty-one women with wrinkles who had just begun to develop wrinkles or already had wrinkles participated in the study for 8 weeks.

A. iwayomogi water fraction significantly reduced wrinkles during the study period, indicating its anti-aging properties [

84].

Artemisia argyi|Moisturizing Effect

Traditional medicine has used

Artemisia argyi for treating skin problems, thus providing a basis for research into its properties. The study evaluated the moisturizing and antioxidant properties of

A. argyi liquid essence, an aqueous solution obtained from the plant leaves through supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, and its mechanisms of action. The research was conducted on isoforms of hyaluronan synthase (HAS2 and HAS3), which responsible for synthesizing hyaluronic acid in the skin, and aquaporin 3 (AQP3) in HaCaT cells. Since, a lack of hyaluronic acid and aquaporins in the skin causes dehydration, which leads to the formation of folds and wrinkles. As result, treatment with liquid essence of

A. argyi showed a significant increase the mRNA and protein expression of AQP3 and HAS2 indicating that it could be a key ingredient in cosmetics to address dry and aging skin problems [

85,

86].

Determination of Tyrosinase Activity in Artemisia Species Germinating in Kazakhstan

Melanoma is among the most aggressive and malignant tumors in humans, originating from melanocytes and characterized by rapid proliferation and a high metastatic potential. Several factors contribute to its development, with UV radiation being the most prominent environmental risk factor. However, endogenous factors, such as hormonal imbalances—particularly those occurring during pregnancy—can also influence pigmentation changes and potentially contribute to melanoma progression. Additionally, individual variations in melanin synthesis, either increased or decreased, modulate the extent of UV-induced damage, leading to differential susceptibility among individuals.

Melanin synthesis, a key protective mechanism facilitating the human body’s adaptation to environmental factors, is mediated by melanocytes [

87,

88,

89,

90]. These specialized cells contain highly organized, membrane-bound structures where melanin production occurs. However, with aging, physiological processes throughout the body, including melanin synthesis, gradually slow down and become less efficient. This decline leads to localized melanin accumulation in certain areas of the skin, which may contribute to an increased risk of melanoma development.

Tyrosinase, a copper-dependent enzyme, plays a pivotal role in regulating the rate of melanin biosynthesis. It catalyzes the oxidation of tyrosine to melanin and other related pigments through a series of enzymatic reactions. The inhibition of tyrosinase activity by specific inhibitors represents a viable approach for modulating melanin production, with potential applications in the treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders and other pigment-related conditions [

91,

92,

93].

Several well-known tyrosinase inhibitors, including kojic acid, ascorbic acid, phytic acid, retinoic acid, arbutin, glabridine, and hydroquinone, have been widely studied for their depigmenting properties. However, their application is associated with various adverse effects. For instance, kojic acid has been reported to cause contact dermatitis and skin irritation, while arbutin can undergo conversion into hydroquinone, a compound with potential cytotoxicity. Hydroquinone itself is recognized for its toxic effects, raising concerns regarding its safety in long-term use. These limitations highlight the need for safer and more effective alternatives in melanin regulation.

The selection of appropriate treatment methods depends on various factors, including the specific condition and a comprehensive understanding of the underlying etiology of skin diseases, which is essential for determining optimal therapeutic strategies. Consequently, there is a growing need for the development of novel and safe treatment approaches. In this regard, natural bioactive compounds derived from plant sources native to Kazakhstan hold significant potential as effective and sustainable alternatives for dermatological applications.

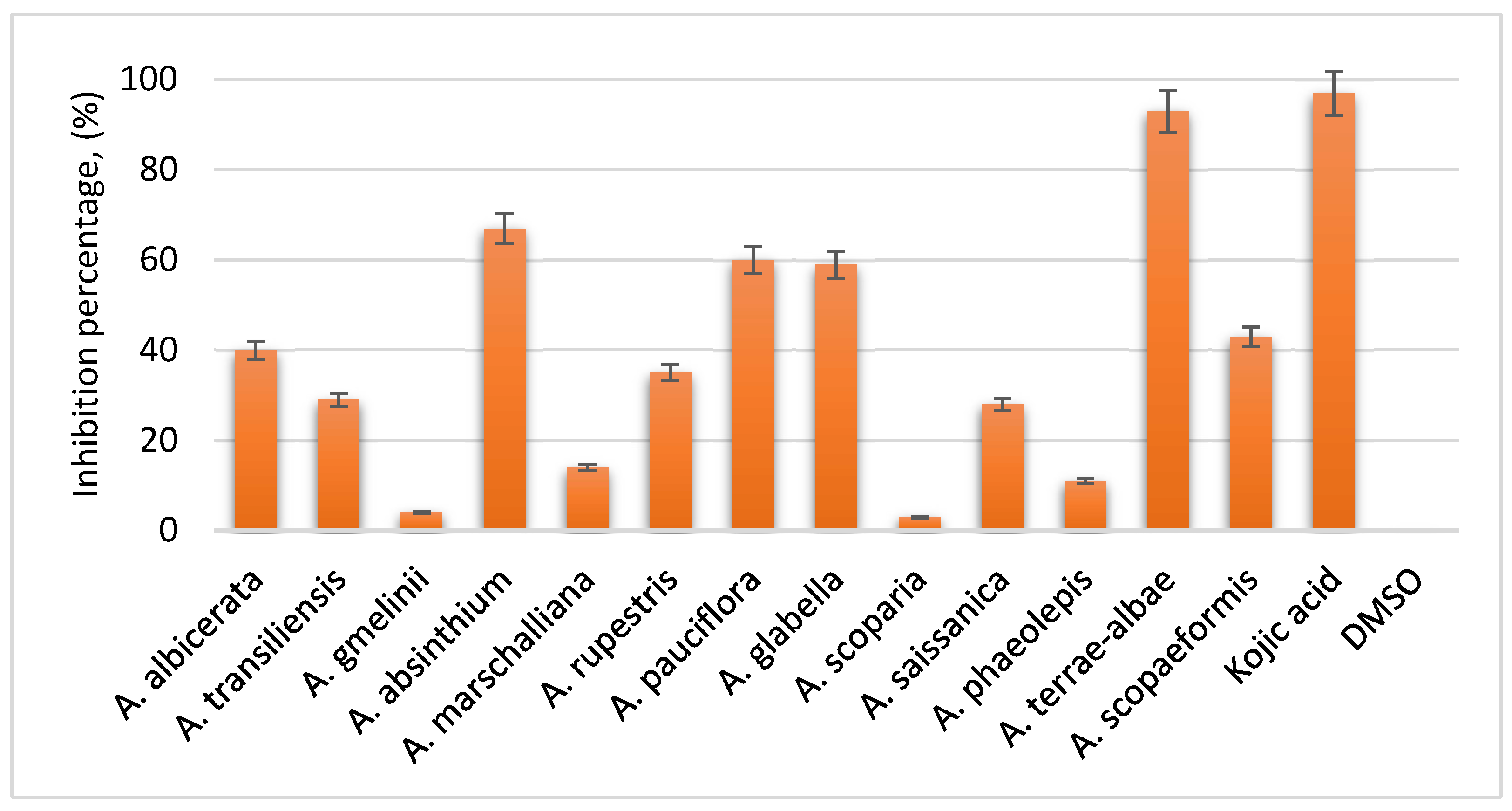

In 2020, the Griffith Institute for Drug Discovery (Australia) conducted an analysis of tyrosinase content in the total extracts of 13 Artemisia plant species included in our study.

Melanocytes contain specialized, highly organized, membrane-bound structures where melanin biosynthesis occurs. With aging, overall physiological processes in the body gradually slow down and become less efficient. This decline similarly affects melanin synthesis, leading to its localized accumulation in certain areas of the skin, which may contribute to an increased risk of melanoma development. The findings of the study were as follows:

Figure 2.

Tyrosinase content in plant extracts.

Figure 2.

Tyrosinase content in plant extracts.

All samples were prepared in a 1% DMSO phosphate buffer, with a final extract concentration of 2.5 mg/mL. Kojic acid, at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL, was used as a reference control due to its well-established efficacy as a potent tyrosinase inhibitor. Analysis of the results revealed that the total extracts of A. terrae-albae exhibited the highest tyrosinase inhibitory activity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the ethnopharmacological importance of Artemisia species are both a reflection of traditional practices and a promising area for pharmacological research. The documentation of these traditional uses, combined with modern phytochemical analyzes, could lead to the development of effective dermatological treatments based on ancient wisdom. As noted in various studies, the integration of traditional knowledge with scientific methods improves our understanding of the true effectiveness of these species of vital plants. Moreover, in order to identify gaps in research field, the efficiency of medicinal plants that could be a candidate for new pharmaceuticals was researched by screening pharmacological and phytochemical studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of the review, J.J., A.K., Zh.A. and A.B.; literature search, A.K., Zh.A. and A.B.S.; design and drawing of tables and figures, A.K., Zh.A., A.B.S. and A.B.; preparation, editing and review the manuscript, J.J., N.M., T.K., and H.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP19676281) and the International Project in collaboration with the Central Asia Center of Drug Discovery and Development of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. CAM202404).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| DNCB |

2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene |

| MRSA |

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

|

| GC-MS |

Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| PHPLC |

Preparative High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

References

- Hay, R.J. , et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. Journal of investigative dermatology 2014, 134, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdanova, A.A. , et al. Cutaneous manifestations of endocrine disorders. Russian Journal of Clinical Dermatology and Venereology 2022, 21, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, C.K. , et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound repair and regeneration 2009, 17, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.R. , et al. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, A.L.B.J. , et al. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. British Journal of Dermatology 2012, 166, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalek, I.M. , et al. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2017, 31, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüss-Üstün, A. , Wolf, J., Corvalán, C., Bos, R. and Neira, M. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks. World Health Organization 2016.

- Wang, D.Y. , et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA oncology 2018, 4, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R. , et al. A systematic review on reporting and assessment of adverse effects associated with transcranial direct current stimulation. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 14, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, J. , Silverberg, N.B. Skin diseases associated with atopic dermatitis. Clinics in Dermatology 2018, 36, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. , et al. Emerging role of immune cell network in autoimmune skin disorders: An update on pemphigus, vitiligo and psoriasis. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2019, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.L. , et al. Vitiligo: an autoimmune skin disease and its immunomodulatory therapeutic intervention. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 797026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzolo, E. , Naldi, L. Epidemiology of major chronic inflammatory immune-related skin diseases in 2019. Expert review of clinical immunology. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z. , et al. The psychosocial impact of pediatric vitiligo, psoriasis, eczema, and alopecia: A systematic review. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 2024, 88, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnowicki, T. , et al. Blood endotyping distinguishes the profile of vitiligo from that of other inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2019, 143, 2095–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, E. , et al. Skin immunity and its dysregulation in atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa and vitiligo. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagaiah, P. , et al. Biologic and targeted therapeutics in vitiligo. Journal of cosmetic dermatology 2023, 22, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speeckaert, R. , et al. Vitiligo: from pathogenesis to treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plavlov, H.V. Flora Kazakhstan, 9th ed.; Compositae; Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR; In-t Botany: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, M. J. , et al. The Artemisia L. genus: A review of bioactive essential oils. Molecules 2012, 17, 17–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, K. S. , Sharma, A. The genus Artemisia: A comprehensive review. Pharmaceutical Biology 2011, 49, 49–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, M. , et al. Bioactive compounds and health benefits of Artemisia species. Natural product communications 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekiert, H. , et al. Artemisia species with high biological values as a potential source of medicinal and cosmetic raw materials. Molecules 2022, 27, 6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, O.A. , et al. Chemical composition, traditional uses and biological activities of artemisia species. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2020, 9, 1124–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Nurlybekova, A. , et al. Traditional use, phytochemical profiles and pharmacological properties of Artemisia genus from Central Asia. Molecules 2022, 27, 5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, k.Y. , et al. In vitro and in vivo anti-aging effects of compounds isolated from Artemisia iwayomogi. Journal of Analytical Science and Technology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C. , et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Artemisia Leaf Extract in Mice with Contact Dermatitis In Vitro and In Vivo. Mediators of Inflammation 2016, 2016, 8027537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchara, N. , et al. Anti-inflammatory and prolonged protective effects of Artemisia herba-alba extracts via glutathione metabolism reinforcement. South African Journal of Botany 2021, 142, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Darwish, M.S. , et al. Artemisia herba-alba essential oil from Buseirah (South Jordan): Chemical characterization and assessment of safe antifungal and anti-inflammatory doses. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2015, 174, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, N. , et al. Current Knowledge on Interactions of Plant Materials Traditionally Used in Skin Diseases in Poland and Ukraine with Human Skin Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugoeze, K.C. , Odeku O.A. Herbal bioactive–based cosmetics. In Herbal Bioactive-Based Drug Delivery Systems. 1st ed.; Bakshi I.S., Bala R., Madaan R., Sindhu R.K.; Academic Press: 2022; pp.195–226.

- Han, X. , et al. Artemisia annua water extract attenuates DNCB-induced atopic dermatitis by restraining Th2 cell mediated inflammatory responses in BALB/c mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, A. , et al. Antioxidant Artemisia princeps Extract Enhances the Expression of Filaggrin and Loricrin via the AHR/OVOL1 Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, A.S. , et al. Development and in Vitro Characterization of Nanoemulsion and Nanoemulsion Based Gel Containing Artemisia Dracunculus Ethanol Extract. International Journal of PharmATA 2022, 2, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, O.S. , et al. Inhibition of 5-Lipoxygenase and Skin Inflammation by the Aerial Parts of Artemisia capillaris and its Constituents. Arch Pharm Res 2011, 34, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H. , et al. Artemisia anomala Herba Alleviates 2,4-Dinitrochlorobenzene- Induced Atopic Dermatitis-Like Skin Lesions in Mice and the Production of Pro-Inflammatory Mediators in Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-/Interferon Gamma-Induced HaCaT Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H. , et al. Ethanolic Extracts of Artemisia apiacea Hance Improved Atopic Dermatitis-Like Skin Lesions In Vivo and Suppressed TNF-Alpha/IFN-Gamma–Induced Proinflammatory Chemokine Production In Vitro. Nutrients 2018, 10, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D. , et al. Artemisia asiatica ethanol extract exhibits anti- photoaging activity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2018, 220, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C. L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: Part 1: Causes and threats. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2015, 40, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Founou, L. L. , et al. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: A developing country-perspective. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D. J. , et al. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. Journal of Natural Products 2016, 59, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A. S. , et al. Antimicrobial properties of medicinal plants: A review. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods – A review. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, D. , et al. Medicinal plants and their bioactive compounds as novel antimicrobial agents. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 2021, 53, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S. H. , Vanitha J. Medicinal plants in dermatology. Indian Journal of Dermatology 2004, 49, 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, P. , et al. Medicinal plants with antibacterial properties: A review. Pharmacognosy Reviews 2011, 5, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia, V. C. Quorum sensing inhibitors: An overview. Biotechnology Advances 2013, 31, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R. , Chanda, S. Antibacterial activity of medicinal plants. International Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Pharmacy 2014, 5, 417–421. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, M. D. , et al. Medicinal plants and their role in dermatological conditions. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy 2016, 8, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, M. F. , et al. The role of skin flora in cutaneous infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2015, 53, 2406–2415. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, L. , et al. Getting under the skin: the immunopathogenesis of Streptococcus pyogenes deep tissue infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2010, 51, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avire, N.J. , et al. A review of Streptococcus pyogenes: public health risk factors, prevention and control. Pathogens 2021, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J. R. , et al. Staphylococcus aureus skin infections: Pathogenesis and antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2006, 44, 2165–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, B. C. , et al. Exfoliative toxins and their role in the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2005, 43, 957–964. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. , et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatologic conditions: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2011, 64, 1294–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Utegenova, G.A. , et al. Antibacterial activity of essential oils from some Artemisia and Thymus species against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Experimental Biology 2017, 2 (71). ISSN 1563-0218. http://bb.kaznu.kz/index.

- Baghini, G.S. , et al. The combined effects of ethanolic extract of Artemisia aucheri and Artemisia oliveriana on biofilm genes expression of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Iran.J.Microbiol. 2018, 10, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moslemi, H. , et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Artemisia absinthium Against Surgical Wounds Infected by Staphylococcus aureus in a Rat Model. Indian J Microbiol 2012, 52, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemtsehay, B.H.; et al. Antibacterial Effects of Artemisia afra Leaf Crude Extract Against Some Selected Multi-Antibiotic Resistant Clinical Pathogens. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2022, 32, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolume, D.G. , et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Artemisia vulgaris Linn. (Damanaka) International Journal of Research in Ayurveda & Pharmacy 2011, 2 (6), 1674-1675. 2 (6).

- Huang, J. , et al. Antibacterial activity of Artemisia asiatica essential oil against some common respiratory infection causing bacterial strains and its mechanism of action in Haemophilus influenzae. Microbial Pathogenesis 2018, 114, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, R. , et al. Antibacterial activity of Tuscan Artemisia annua essential oil and its major components against some foodborne pathogens. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2015, 64, 1251–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilia, A.R. , et al. Essential Oil of Artemisia annua L.: An Extraordinary Component with Numerous Antimicrobial Properties. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014, 1, 159819. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N.Y. , et al. Artemisia princeps Inhibits Biofilm Formation and Virulence-Factor Expression of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. BioMed Research International 2015, 1, 239519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsyk, R.A. , et al. The investigation of antimicrobial and antifungal activity of some Artemisia L. species. Pharmacia 2021, 68, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nametov, A. , et al. Evaluation of the antibacterial effect of Artemisia lerchiana compared with various medicines. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2023, 83, e277641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J. , et al. Antimicrobial activity in Asterceae: The selected genera characterization and against multidrug resistance bacteria. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi Moussii, I. ,et al. Synergistic antibacterial effects of Moroccan Artemisia herba alba, Lavandula angustifolia and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils. Synergy 2020, 10, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendifallah, L. , Merah, O. Phytochemical and biocidal properties of Artemisia campestris subsp. campestris L. (Asteraceae) essential oil at the southern region of Algeria. Journal of Natural Pesticide Research 2023, 4, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Bioactive Principles and Potentiality of Hot Methanolic Extract of the Leaves from Artemisia absinthium L “in vitro Cytotoxicity Against Human MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells, Antibacterial Study and Wound Healing Activity”. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology 2020, 21, 1711–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, H. , et al. Artemisia capillaris inhibits atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in Dermatophagoides farinae-sensitized Nc/Nga mice. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2014, 14, http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472–6882/14/100. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, K.B. , et al. Chlorogenic Acid Isomers Isolated from Artemisia lavandulaefolia Exhibit Anti-Rosacea Effects In Vitro. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. , et al. In vitro and in vivo anti-eczema effect of Artemisia annua aqueous extract and its component profiling. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, F. , et al. In vitro anti-leishmanial activity of Satureja hortensis and Artemisia dracunculus extracts on Leishmania major promastigotes. J Parasit Dis 2016, 40, 1571–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K. , et al. Artemisia Naphta: A novel oil extract for sensitive and acne prone skin. Ann Dermatol Res. 2021, 5, 022–029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A. , et al. Modulation of Cox-1, 5-, 12- and 15-Lox by Popular Herbal Remedies Used in Southern Italy Against Psoriasis and Other Skin Diseases. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.Y. , et al. Protective effects of halophyte complex extract against UVB-induced damage in human keratinocytes and the skin of hairless mice. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.Y. , et al. Antioxidative and Protective Activity of Polysaccharide Extract from Artemisia iwayomogi Kitamura Stems on UVB-Damaged Mouse Epidermis. J. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2011, 54, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Orfi, et al. Use of Medicinal Plants by Cancer Patients Under Chemotherapy in the Northwest of Morocco (Rabat Area): Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahem, N.M. Extraction and Characterization of Iraqi Artemisia dracunculus Dried Aerial Parts Extract Though Hplc and Gc-Ms Analysis with Evaluation of Its Antitumor Activity Against 7, 12-Dimethylbenze (A) Anthracene Induced Skin Cancer in Mice. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2017, 9, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuleuova, D.A. , et al. Melanoma: incidence and mortality in the world and Kazakhstan in 2018. Journal of Oncology and Radiology of Kazakhstan 2020, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Buommino, E. , et al. Artemisinin reduces human melanoma cell migration by down-regulating αVβ3 integrin and reducing metalloproteinase 2 production. Invest New Drugs 2009, 27, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, M. , et al. Artemisinin Inhibits the Migration and Invasion in Uveal Melanoma via Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 9115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y. , et al. In vitro and in vivo anti-aging effects of compounds isolated from Artemisia iwayomogi. Journal of Analytical Science and Technology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollag, W.B. , et al. Aquaporin-3 in the epidermis: more than skin deep. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2020, 318, C1144–C1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. , et al. Moisturizing and Antioxidant Effects of Artemisia argyi Essence Liquid in HaCaT Keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K. , et al. Chemical and biochemical control of skin pigmentation with special emphasis on mixed melanogenesis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021, 34, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. , et al. Advances in Biomedical Functions of Natural Whitening Substances in the Treatment of Skin Pigmentation Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. , et al. Genome-wide association analysis reveal the genetic reasons affect melanin spot accumulation in beak skin of ducks. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. , et al. Decursin prevents melanogenesis by suppressing MITF expression through the regulation of PKA/CREB, MAPKs, and PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β cascades. Biomed. Pharmacother 2022, 147, 112651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinheimo, E. , et al. Comparison of the characteristics of fungal and plant tyrosinases. Journal of biotechnology 2007, 130, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Casanola-Martin, G., et al. Tyrosinase enzyme: 1. An overview on a pharmacological target. Current topics in medicinal chemistry 2014, 14, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, W. , et al. Chitosan and chitin oligomers increase phenylalanine ammonia-lyase and tyrosine ammonia-lyase activities in soybean leaves. Journal of plant physiology 2003, 160, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).