Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

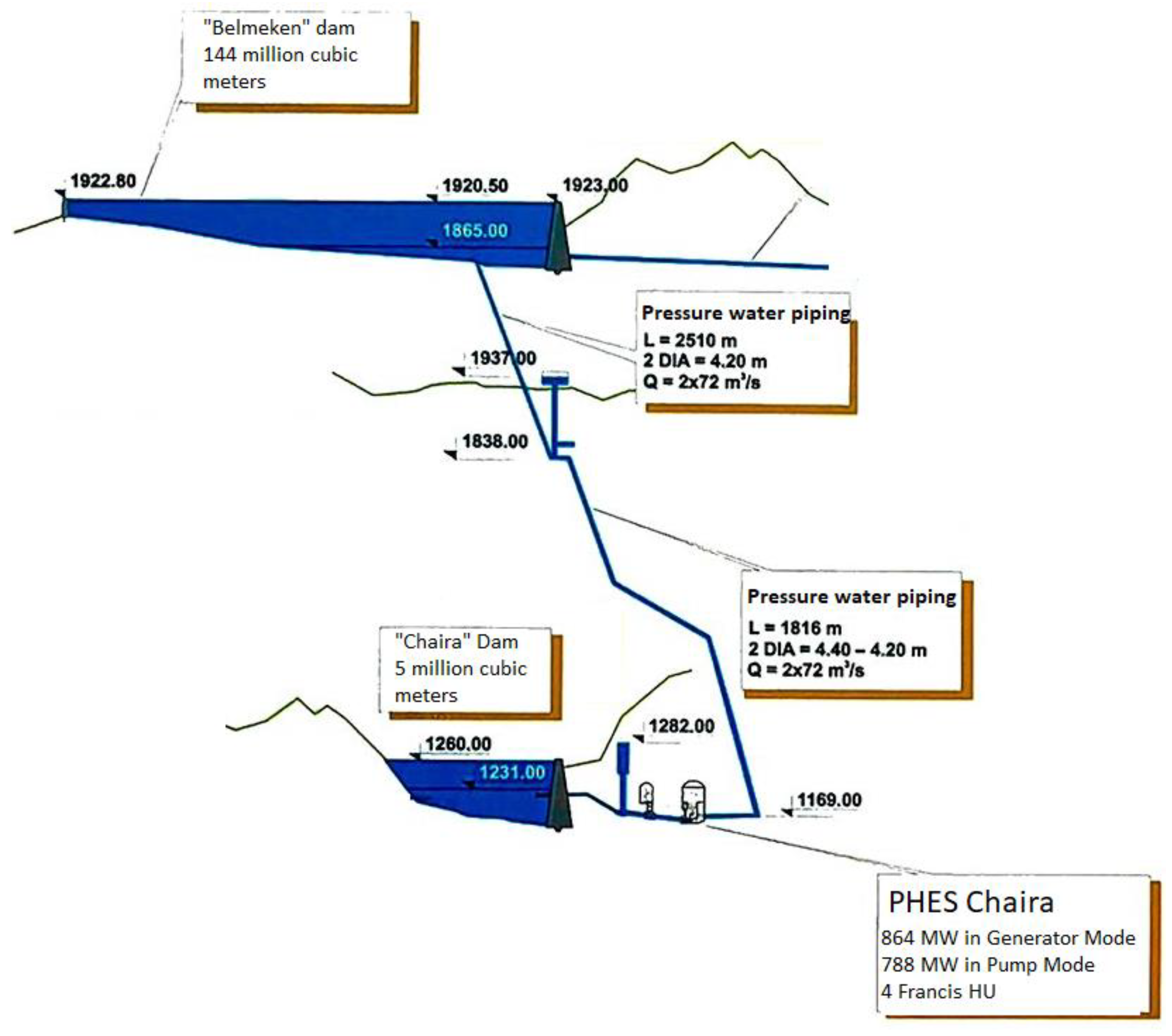

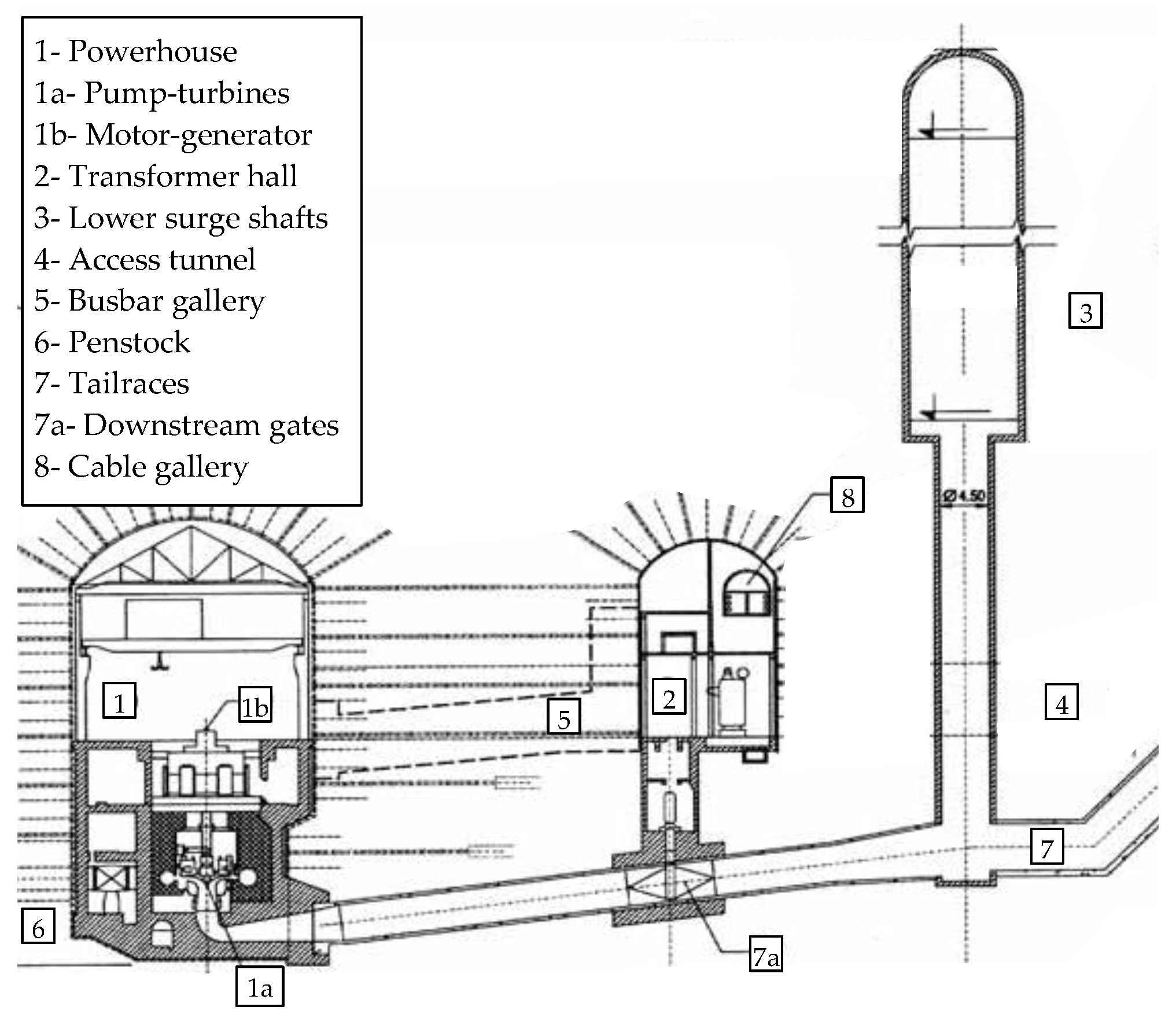

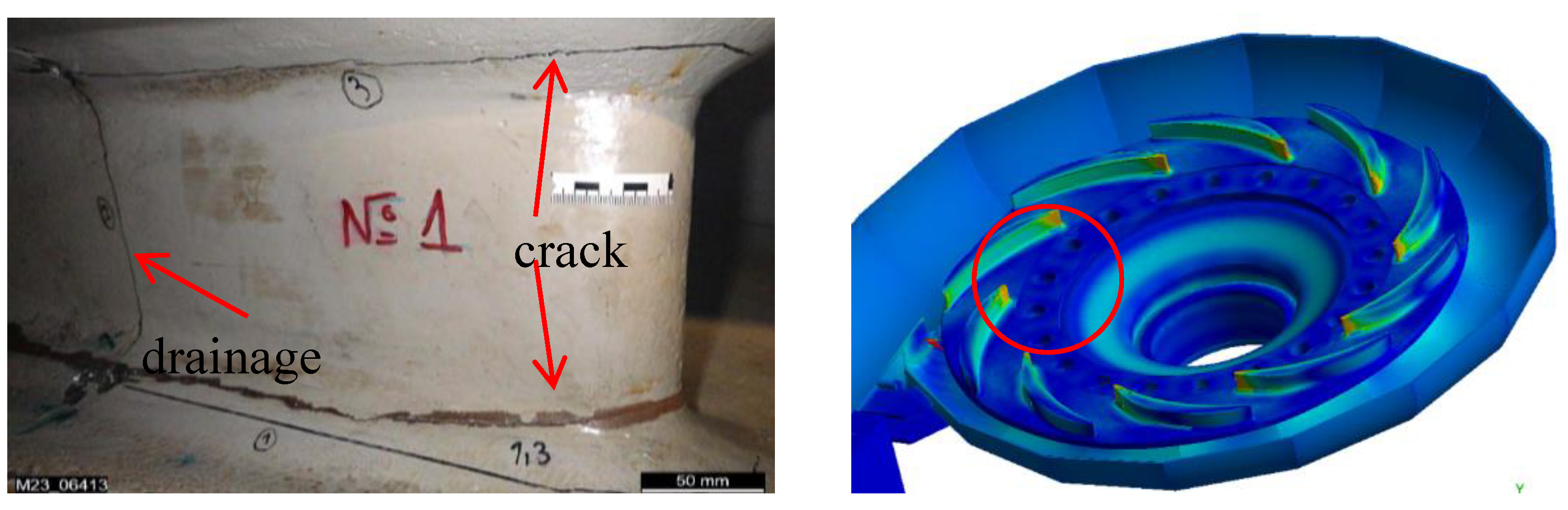

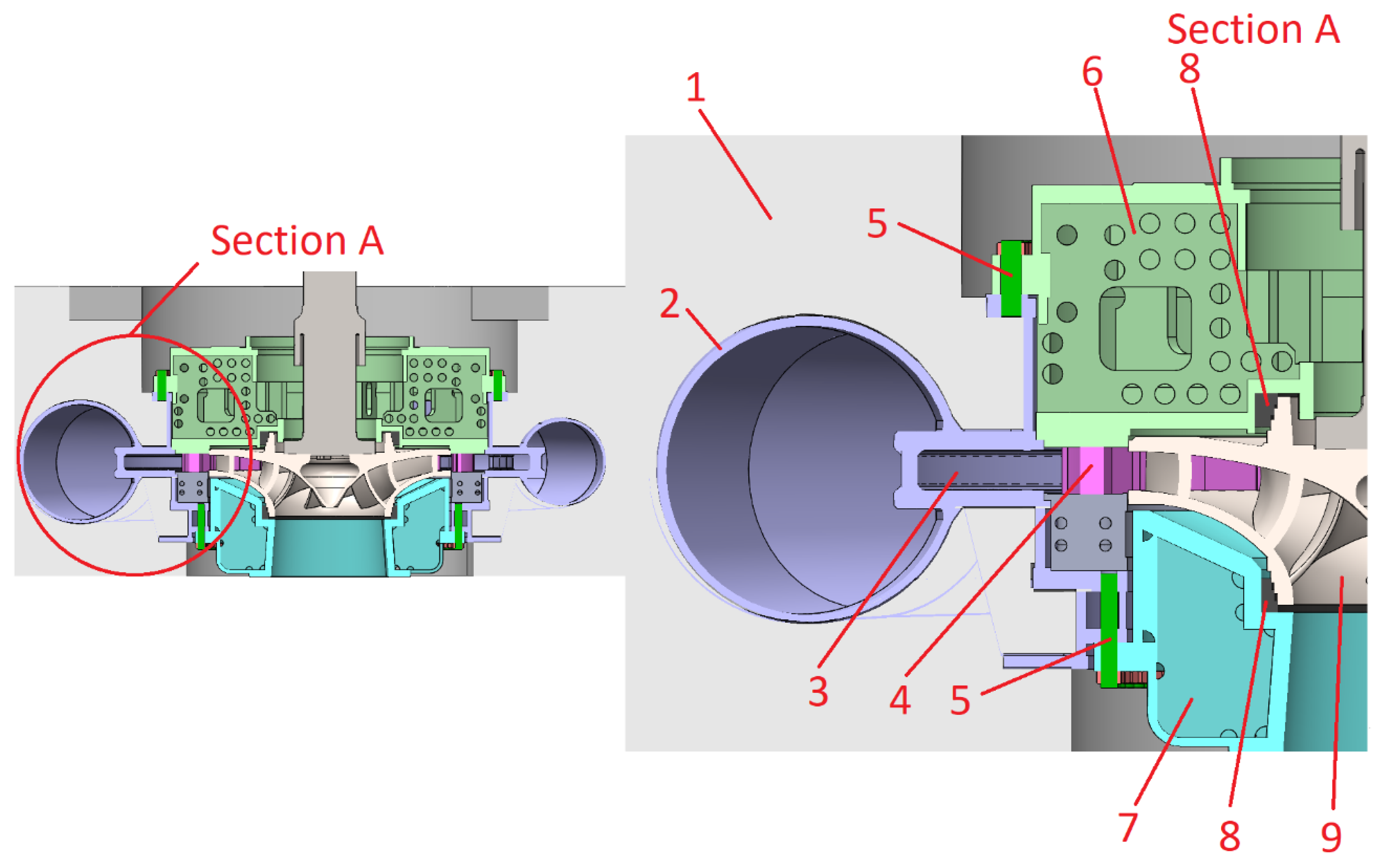

In the present paper subject of the investigations is the reliability assessment of the single-stage reversible Hydropower Unit No. 3 (HU3) in the Bulgarian Pumped Hy-dro-Electric Storage (PHES) plant “Chaira”, which processes the waters of the “Belmeken” dam and “Chaira” dam. Preceding destruction of HU4 and its virtual simulation, analysis and the conclusions for the rehabilitation and safety provided the information for the possible processes in HU3. Detailed analysis of the consequences of prolonged use of HU3 was carried out. The Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system records were studied. Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) is applied to determine the component relationships and subsystem failures that can lead to an undesired primary event. The functional structure of the system was depicted as a causal chain of failure effects. The probability of system failure was estimated based on the failure probabilities of the primary events. The effects of static loads, dynamic loads and low-cycle loads were investigated. Based on the experience and the investigations of the HU4 and its damages, as well as of the failures in the stay vanes of HU3 it is recommended to organize monitoring for water ingress into the drainage holes, which will allow detecting failures in a timely manner.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

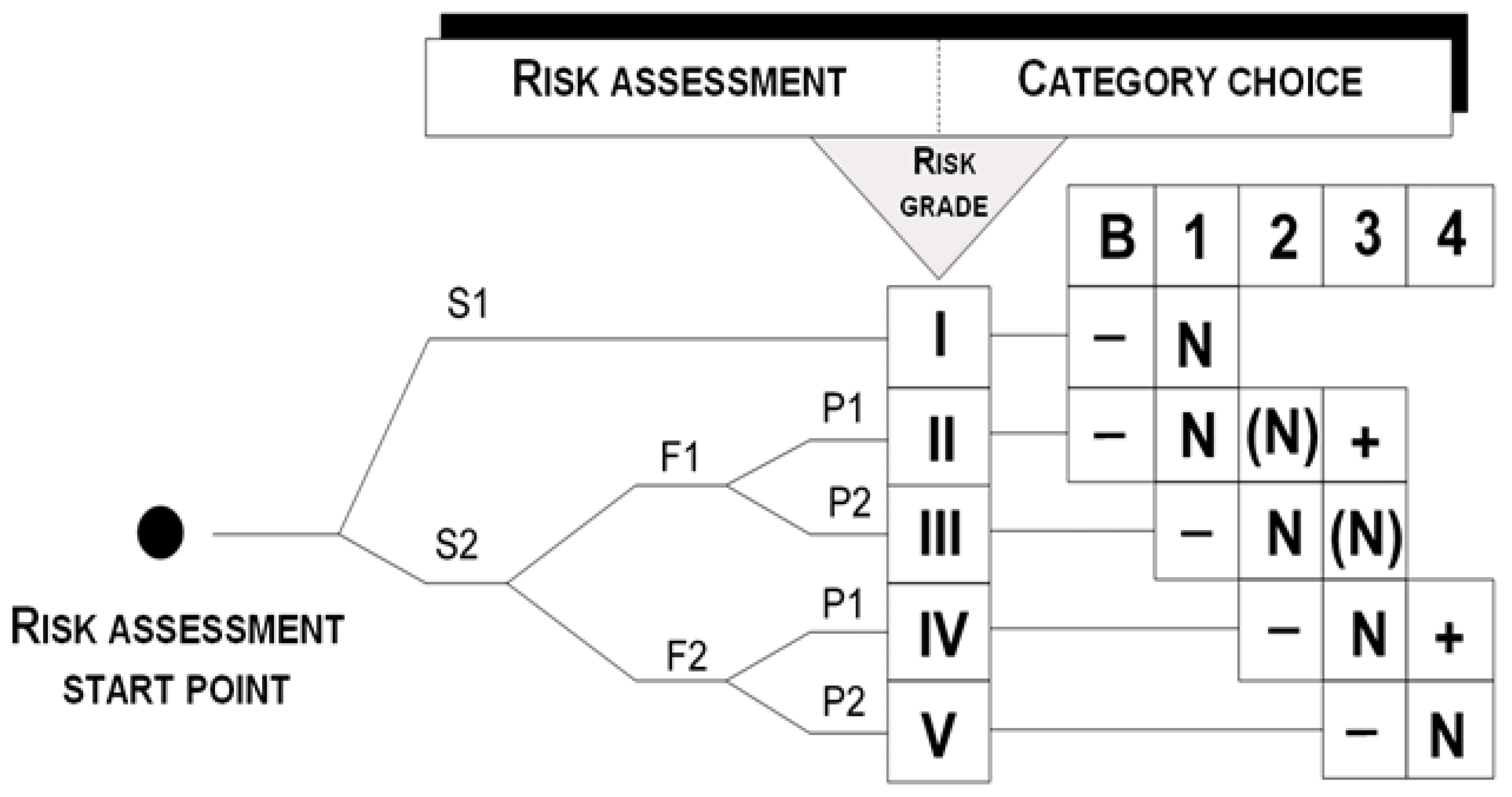

2.1. Risk Analysis. Essence

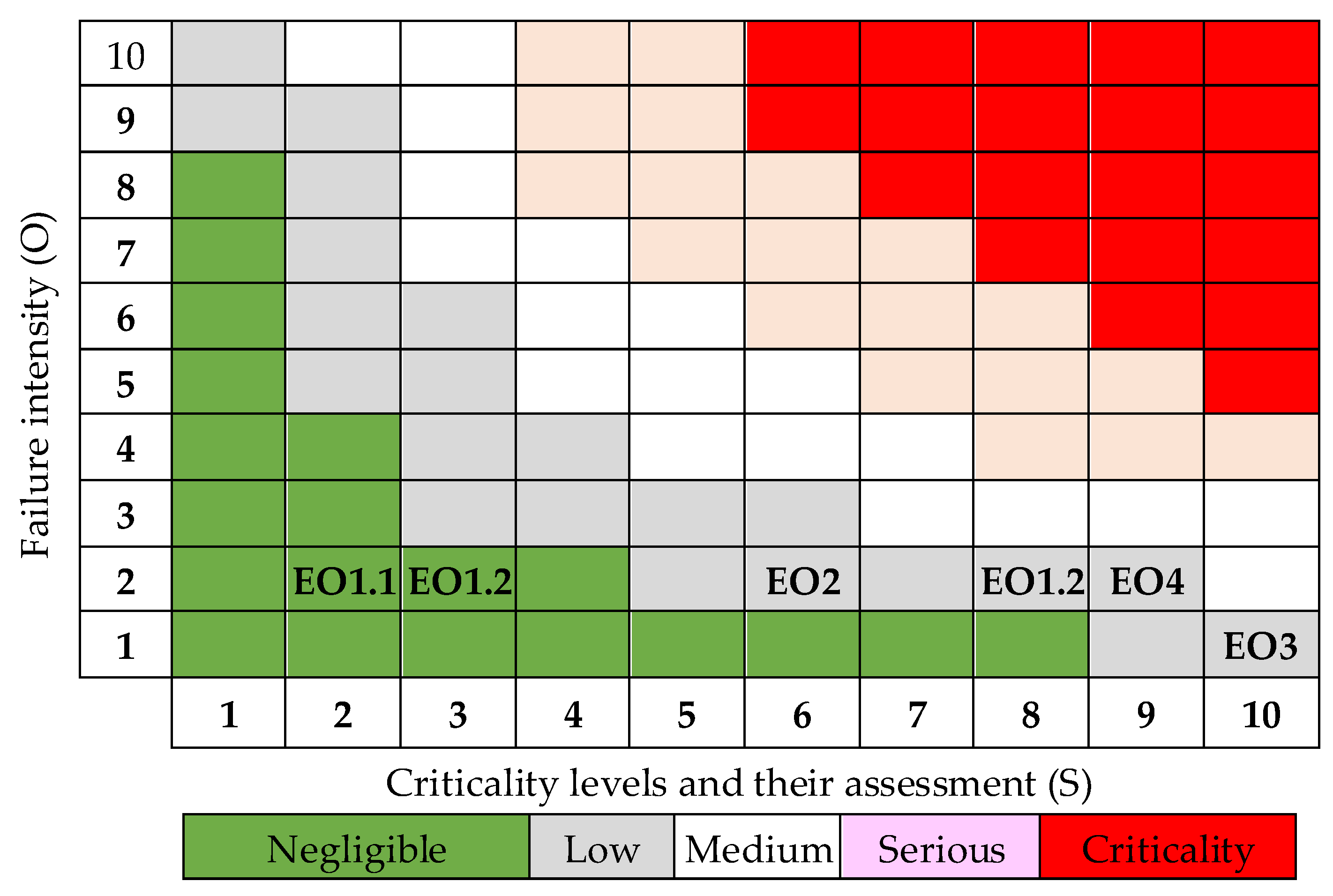

2.2. Methodology Used for Analysis of Failures and Their Effects

- S (severity, criticality) assesses the degree of significance of the failure;

- O (occurance, failure intensity) assesses the likely occurrence of such a failure;

- D (detection, detectability) represents the probability of detecting the cause of the failure.

- RPN values up to 40 indicate low risk (no need for corrective actions);

- RPN values in the range 40 ÷ 100 indicate moderate risk (certain actions are needed to improve the study object);

- RPN values above 100 are classified as unacceptable risk (urgent actions are needed).

3. Results

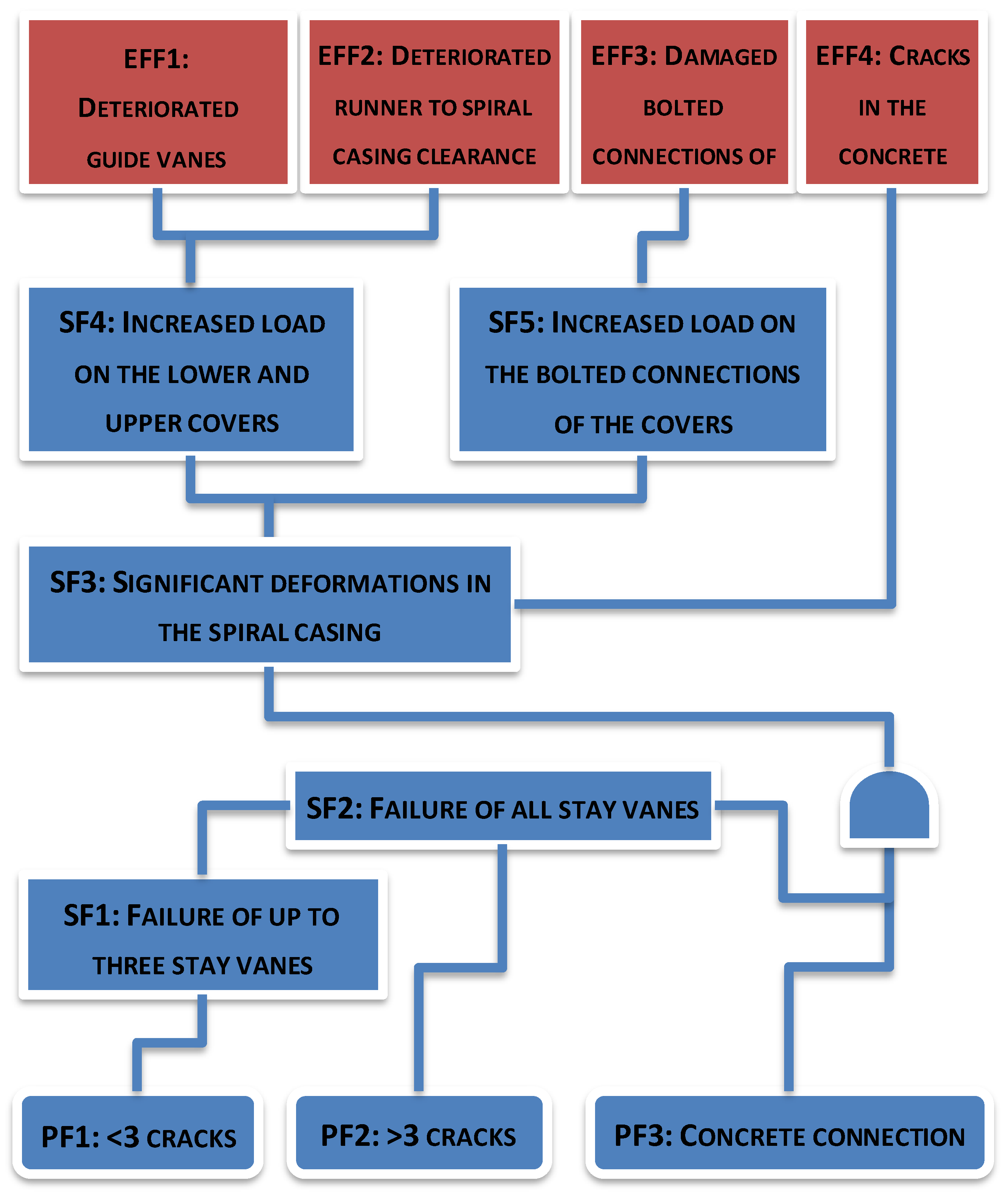

3.1. Fault Tree Analysis of the HU3 of PHES “Chaira”

- Primary failure (failure of a component under normal operating conditions);

- Secondary failure (failure of a component as a result of secondary failure from a primary failure or as a result of extreme operating conditions);

- Errors as a result of incorrect operation or misuse.

-

Primary failures/shutting out (PF):

- ○

- PF1: Crack formation on the faces of up to three stay vanes due to low-cycle material fatigue;

- ○

- PF2: Crack formation on the faces of more than three stay vanes due to low-cycle material fatigue;

- ○

- PF3: Violation of the bond between concrete and spiral casing leading to a backlash.

-

Secondary failures/shutting out (SF):

- ○

- SF1: Failure of up to three stay vanes;

- ○

- SF2: Failure of all stay vanes;

- ○

- SF3: Significant deformations in the spiral casing;

- ○

- SF4: Increased load on the lower and upper covers;

- ○

- SF5: Increased load on the bolted connections of the covers, due to their overloading by bending moment.

-

Effects because of failures (EFF):

- ○

- EFF1: Deteriorated guide vanes bearing – violation of clearance and coaxiality between the guide vanes and the bearings, leading to difficult closing (switching off) of the vanes control;

- ○

- EFF2: Deteriorated runner to spiral casing clearance – violation of clearance between the runner and the spiral casing and possible mutual contact;

- ○

- EFF3: Damaged bolted connections of covers – destruction of bolted connections of the covers, due to their overloading by bending moment;

- ○

- EFF4: Cracks in the concrete – cracking of the concrete, due to overloading of the spiral casing and total failure of the stay vanes.

3.2. Analysis of Failures in the Stay Vanes of HU3 and Their Effects

- G1: Nominal generator mode – mode of the system operation as a generator in a steady state;

- G2: Peak loads in the generator mode – process of switching to a nominal generator mode for which the loads on the runner and the entire structure increase;

- P1: Nominal Pump mode, - mode of operation of the system as a pump in a steady state;

- P2: Peak loads in the pump mode – process of switching to a nominal pump mode for which the loads on the runner and the entire structure increase;

- P3: Pump mode when runner spins – mode in which the runner spins infor a closed system until the required speed and pressure are reached;

- A1: Drop of the load mode – sudden loss of load on the runner leading to an increase of the rotation speed;

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- regular inspection and planned repairs be to provided;

-

units that cannot be surveyed visually must be equipped with sensors and control devices, these are

- ○

- the guide vanes and their welding places;

- ○

- the water ingress in the bearings;

- ○

- the gap between the concrete and the spiral casing;

- ○

- the deflections of the bolts of the upper and the lower covers;

- ○

- the stresses in the spiral casing;

- monitoring for water ingress into the drainage holes should be organized.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available online: https://www.nek.bg/index.php/en/ (accessed on 05 January 2025).

- Available online: https://wwtech.com.pl/en/2024/09/11/chaira-pump-storage-hpp-bulgaria/ (accessed on January 05, 2025).

- Available online online: https://balkangreenenergynews.com/bulgaria-to-replace-broken-turbines-in-chaira-pumped-storage-hydropower-plant/ (accessed on January 05, 2025).

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_hydroelectric_power_station_failures.

- Yasuda, M.; Watanabe, S. How to Avoid Severe Incidents at Hydropower Plants. Int. J. Fluid Mach. Syst. 2017, 10, 296–306. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sayano-Shushenskaya_power_station_accident.

- Fisher, R.K. Jr., et al., 2002, “A Case Study in Resonant Hydroelastic Vibration: The causes of Runner Cracks and the Solutions implemented for the Xiaolangdi Hydroelectric Project,” 21st IAHR.

- Available online: https://www.hydropower.org/sediment-management-case-studies/nepal-kali-gandaki.

- Aliabadi, A. and Shamekhi, A., 2007. “Von Karman frequency excitation caused cracking of the Karun III Francis runner,” HYDRO2007 6.04.

- Alvarez, A., 2011, “Solving a Problem Related to Shear Pin Failure,” HydroWorld.com. https://www.hydroreview.com/world-regions/latin-america/solving-a-problem-related-to-shear/.

- Halipchuk, P. et al., 2011, “Machining Solutions: Repairing Cracked Turbine Shafts at Jenpeg,” HydroWorld.com. https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/baseload/hydropower/machining-solutions-repairing-cracked-turbine-shafts-at-jenpeg/.

- Price, J. W.H., 1998, “The failure of the Dartmouth turbine casing,” International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping Volume 75, Issue 7, pp 559–566. [CrossRef]

- Chinese scientists - Gao, X.; Fu, D.; Wu, H. Embedment of Steel Spiral Casings in Concrete: Lessons from a Structural Deformation Accident in China. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8395. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, C. Static and dynamic damage analysis of mass concrete in hydropower house of Three Gorges Project. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2010, 16, 433–440. [CrossRef]

- Todorov, G.; Kralov, I.; Kamberov, K.; Sofronov, Y.; Zlatev, B. Failure mechanisms of stay vanes in a PHES Francis turbine unit. In Proceeding of the 13th International Scientific Conference “TechSys 2024”—Engineering, Technologies and Systems, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 18 May 2024.

- Todorov, G.; Kralov, I.; Kamberov, K.; Zahariev, E.; Sofronov, Y.; Zlatev, B. An Assessment of the Embedding of Francis Turbines for Pumped Hydraulic Energy Storage. Water 2024, 16, 2252. [CrossRef]

- Todorov, G.; Kralov, I.; Kamberov, K.; Sofronov, Y.; Zlatev, B.; Zahariev, E. Investigation and Identification of the Causes of the Unprecedented Accident at the “Chaira” Pumped Hydroelectric, Energy Storage. Water 2024, 16, 3393. [CrossRef]

- Hanel, B. FKM-Guideline. In Analytical Strength Assessment of Components in Mechanical Engineering; VDMA Verlag GmbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 2003.

- Chryssanthopoulos, M.; Righiniotis, T. Fatigue reliability of welded steel structures. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2006, 62, 1199–1209. [CrossRef]

- Xin Liu; Yongyao Luo; Zhengwei Wang. A review on fatigue damage mechanism in hydro turbines, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 54, February 2016, Pages 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Lyutov, A.; Kryukov, A.; Cherny, S.; Chirkov, D.; Salienko, A.; Skorospelov, V.; Turuk, P. Modeling of a Francis Turbine Runner Fatigue Failure Process Caused by Fluid-Structure Interaction. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 49, 072012. [CrossRef]

- Presas, A.; Yongyao, L.; Zhengwei, W.; Bao, G. Fatigue life estimation of Francis turbines based on experimental strain meas-urements: Review of the actual data and future trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 96–110. [CrossRef]

- Biner, D.; Alligné, S.; Nicolet, C.; Dujic, D.; Münch-Alligné, C. Numerical fatigue damage analysis of a variable speed Francis pump-turbine during start-up in generating mode. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1079, 012079. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Qi-Ling; Hu, Lei; Gao, Xiao-Feng. Fatigue life prediction of steel spiral cases in pumped-storage power plants: Factors to be considered. Engineering Failure Analysis 2024, 157, 107908. [CrossRef]

- Souza, Rodrigo de Queiroz; Álvares, Alberto José. FMEA and FTA Analysis for Application of the Reliability Centered Maintenance Methodology: Case Study on Hydraulic Turbines, ABCM Symposium Series in Mechatronics, Vol. 3, 803-812, Copyright °c 2008. https://www.abcm.org.br/symposium-series/SSM_Vol3/Section_VII_Emerging_Technologies_and_Applications/SSM3_VII_10.pdf.

- Peeters, J.F.W.; Basten, R.J.I.; Tinga, T. Improving failure analysis efficiency by combining FTA and FMEA in a recursive manner. Reliability Engineering System Safety 2018, 172, 36–44. [CrossRef]

- InfraSpeak Team, FTA vs FMEA: What Are The Differences? October 23, 2020. https://blog.infraspeak.com/fta-vs-fmea/.

- Standard: DIN EN ISO 12100:2011-03, Safety of machinery - General principles for design - Risk assessment and risk reduction, Publication date 2011-03, Original language German, Pages 96. https://www.dinmedia.de/en/standard/din-en-iso-12100/128264334.

- Flynn, A.M. Hazard Risk Assessment, Chapter in the Book Introduction to Environmental Management, Editors: Theodore, M.K., Theodore, L. 2nd Edition Imprint CRC Press, Pages11, 2021. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003171126-44/hazard-risk-assessment-ann-marie-flynn.

- Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment, Study Report Consultancy and Training Services by TheSaftyMaster, Published by TheSafeyMaster, September 18, 2024. https://www.thesafetymaster.com/hazard-identification-and-risk-assessment-study-report-consultancy-and-training-services-by-thesafetymaster/Author.

- Standard DIN EN ISO 14121-1:2007-12 Safety of machinery - Risk assessment - Part 1: Principles (ISO 14121-1:2007); German version Sicherheit von Maschinen - Risikobeurteilung - Teil, Pages 35. https://www.dinmedia.de/en/standard/din-en-iso-14121-1/94405328.

- Quality-One International, Introduction to Failure Mode, Effects & Criticality Analysis (FMECA). https://quality-one.com/fmeca/.

- Available online: Military handbook. Reliability prediction of electronic equipment. 1991. Accessed online https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/NSWC_Crane/SD-18/Test%20Methods/MILHDBK217.pdf.

- Marvin Rausand, Stein Haugen, Risk Assessment: Theory, Methods, and Applications, 2nd Edition. Wiley. March 2020. ISBN: 978-1-119-37722-1.

| Level | Description | Rating (S) |

|---|---|---|

| None | No effect on components | 1 |

| Minor | Minor effect on the system | 2 |

| Very low | Slightly pronounced impact on the system | 3 |

| Low | Low level of criticality regarding the functioning of the system | 4 |

| Average | The system is functioning, with broken parameters | 5 |

| High | Reduced system functionality | 6 |

| Very high | Loss of important system functions | 7 |

| Dangerous | Functions are lost, leading to potential danger to users | 8 |

| Very dangerous | Potentially dangerous system condition, with indications allowing preventive action | 9 |

| Extremely dangerous | System condition with possible critical impacts on personnel, without possibility of detection and prevention | 10 |

| Intensity | Probability | Rating (O) |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely low | ≤1∙10-5 | 1 |

| Low | 1∙10-4 | 2 |

| Average grade | 5∙10-4 | 3 |

| 1∙10-3 | 4 | |

| 2∙10-3 | 5 | |

| High degree (repeatability) | 5∙10-3 | 6 |

| 1∙10-2 | 7 | |

| 2∙10-2 | 8 | |

| 5∙10-2 | 9 | |

| Very high degree | ≥1∙10-1 | 10 |

| Grade | Description | Rating (D) |

|---|---|---|

| Very high | Very high probability of failure detection | 1 |

| High | High probability of failure detection | 2 |

| Relatively high | Relatively high probability of failure detection | 3 |

| Medium | Average probability of detecting failure | 4 |

| Relatively low | Relatively low probability of detecting the potential cause/mechanism of failure | 5 |

| Low | Low probability of detecting the potential cause/mechanism of failure | 6 |

| Very low | Very low probability of detecting the potential cause/mechanism of failure | 7 |

| Weak | Weak probability of detecting the potential cause/mechanism of failure | 8 |

| Very weak | Very weak probability of detecting the more potential cause/mechanism of failure | 9 |

| Impossible | Inability to establish the refusal | 10 |

| Effect of refusal | Mode | Effect | Mark |

|---|---|---|---|

| ЕО1: Violation of the clearance and alignment between the guide vanes and bearings leading to difficult or no control | P1/P2/ | Strong vibrations in the structure; Water appearing in the service area through drainage holes in the stay vanes. |

ЕО1.1 |

| G1/G2 | Strong vibrations in the structure; Water appearance in the service area through drainage holes in the stay vanes; Difficulty for closing the water flow and switching off the machine |

ЕО1.2 | |

| А1 | Strong vibrations in the structure; Water appearing in the service area through drainage holes in the stay vanes; Rapid increase of the machine rotation frequency and danger of exceeding critical ones, leading to destruction; Serious damage to the electrical part of the system |

ЕО1.3 | |

| ЕО2: Violation of the clearance between the runner and the spiral casing and contact | G1/G2/P1/P2/А1 | Strong impacts to the structure; Water in the service area; Risk of destruction of the runner bearing; Possible mechanical damage to the spiral casing and the runner |

ЕО2 |

| ЕО3: Destruction of bolted connections of the covers due to overloading by bending moment | G1/G2/P1/P2/А1 | Strong impacts to the structure; Massive water ingress into the engine room; Difficult or impossible closing of the guide vanes |

ЕО3 |

| ЕО4: Cracking of the concrete due to overloading of the spiral casing and broken integrity of the stay vanes | G1/G2/P1/P2/А1 | Severe deformations in the structure; Difficult or impossible closing of the guide vanes Danger of destruction of the runner bearing; Serious damages to the electrical part of the system |

ЕО4 |

| Failure effect | Criticality (S) | Intensity (O) | Detectability rate (D) | RPN |

| ЕО1.1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 24 |

| ЕО1.2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 36 |

| ЕО1.3 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 32 |

| ЕО2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| ЕО3 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 20 |

| ЕО4 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).