Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

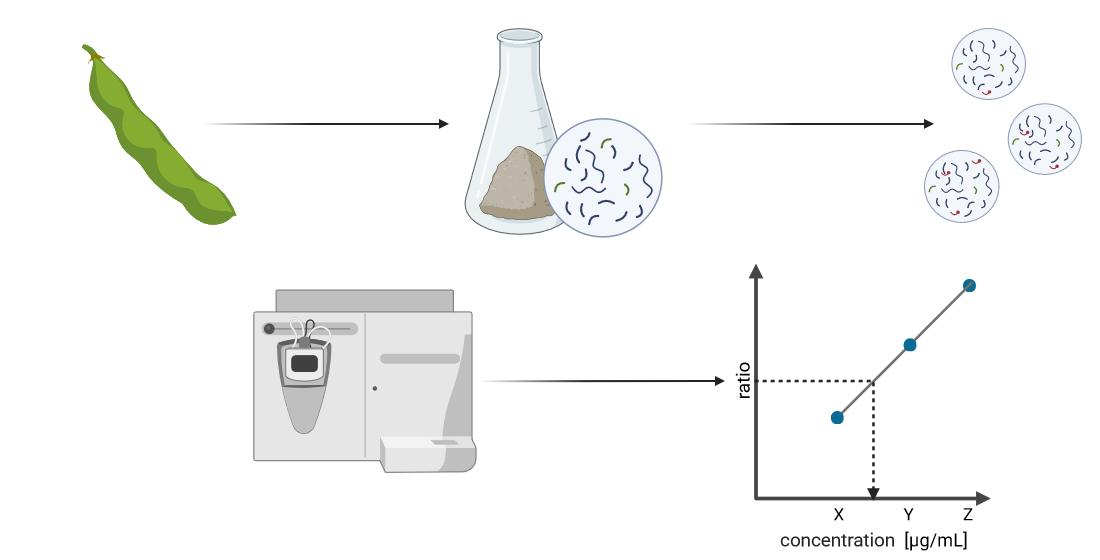

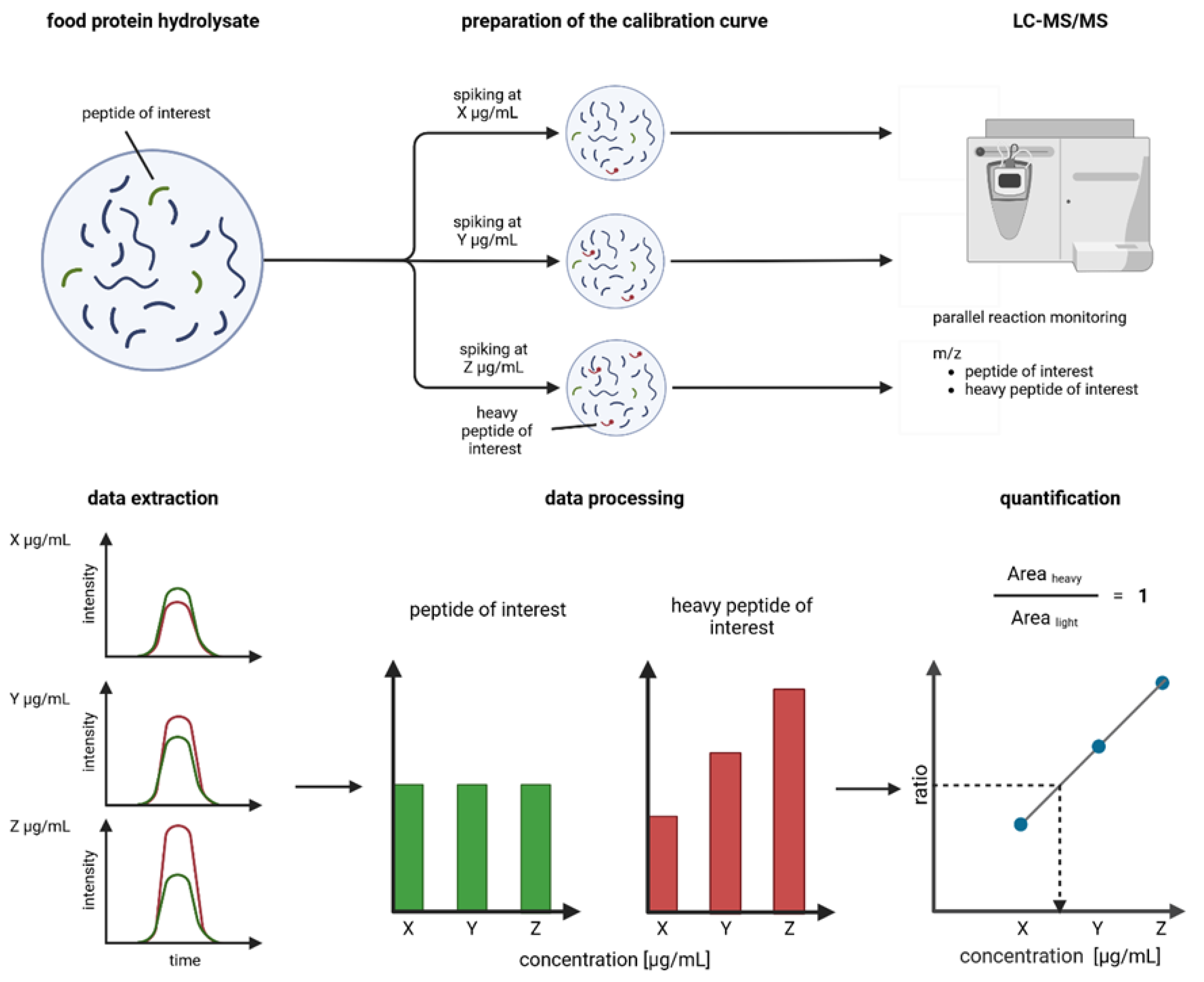

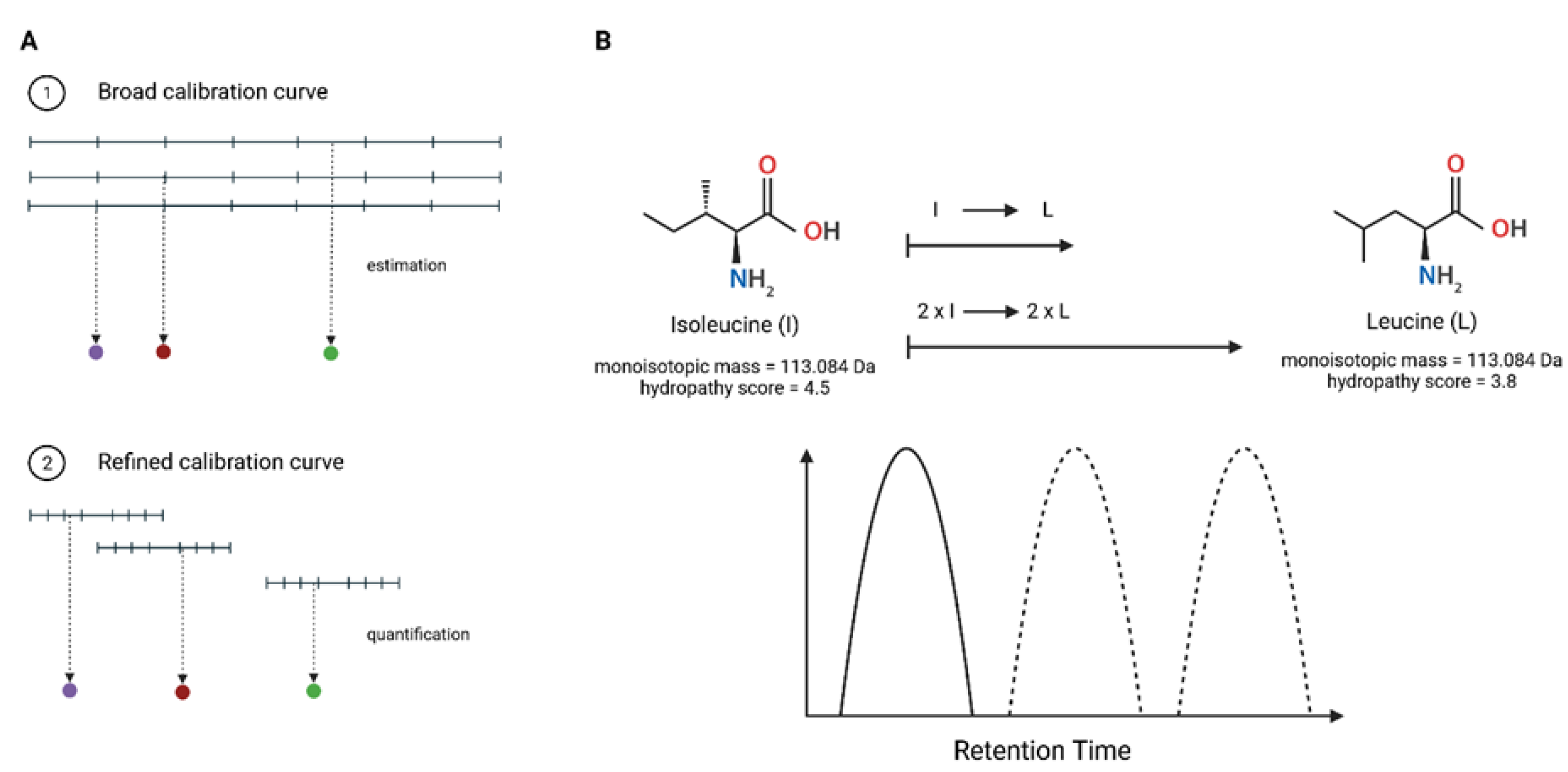

2.2. Preparation of Broad and Refined Internal Calibration Curves

2.3. Parallel Reaction Monitoring Mass Spectrometry Method and Inclusion List

2.4. Peak Integration

2.5. Peptide Sequence Validation

2.6. Linear Regression and Peptide Quantification

3. Results

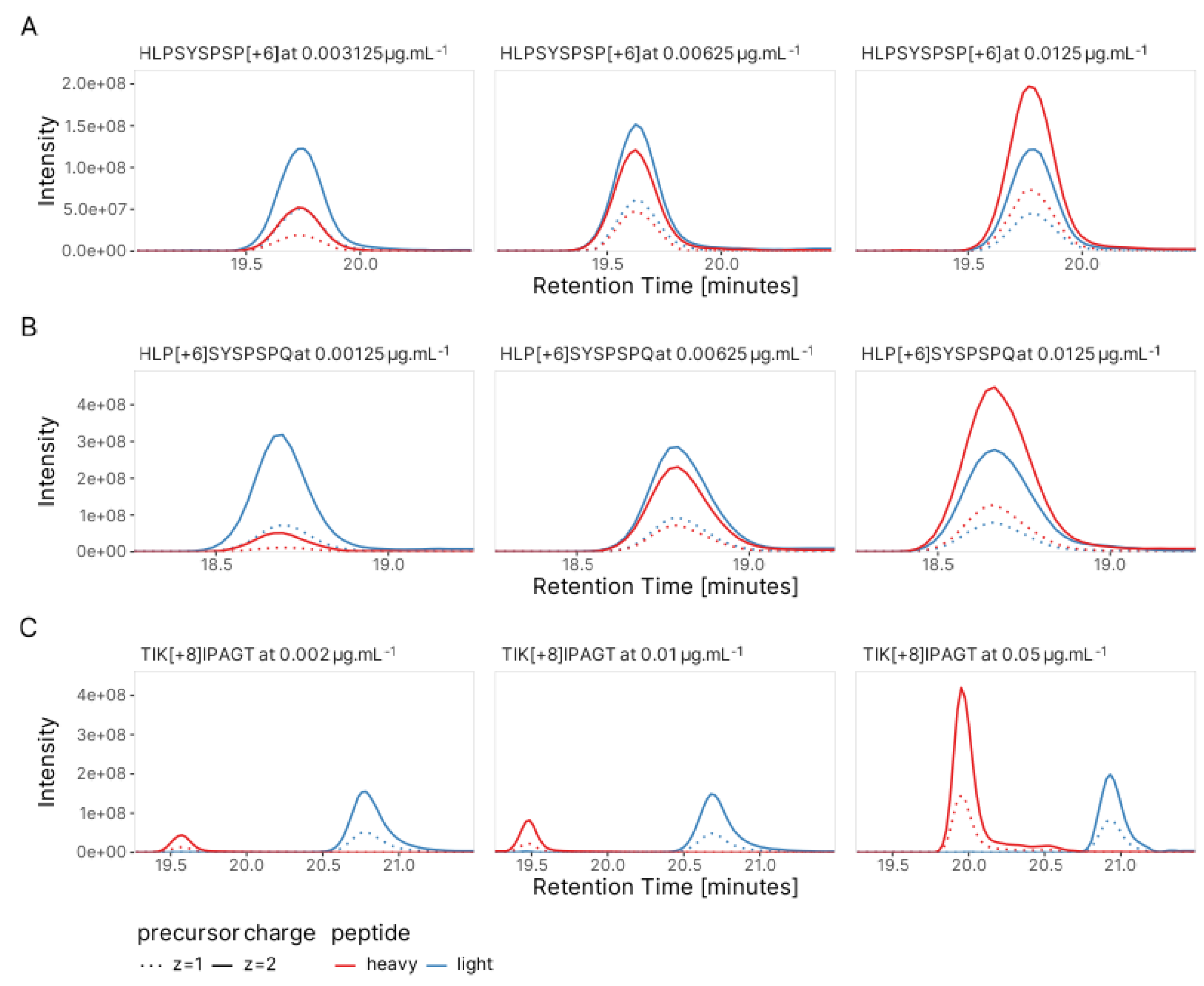

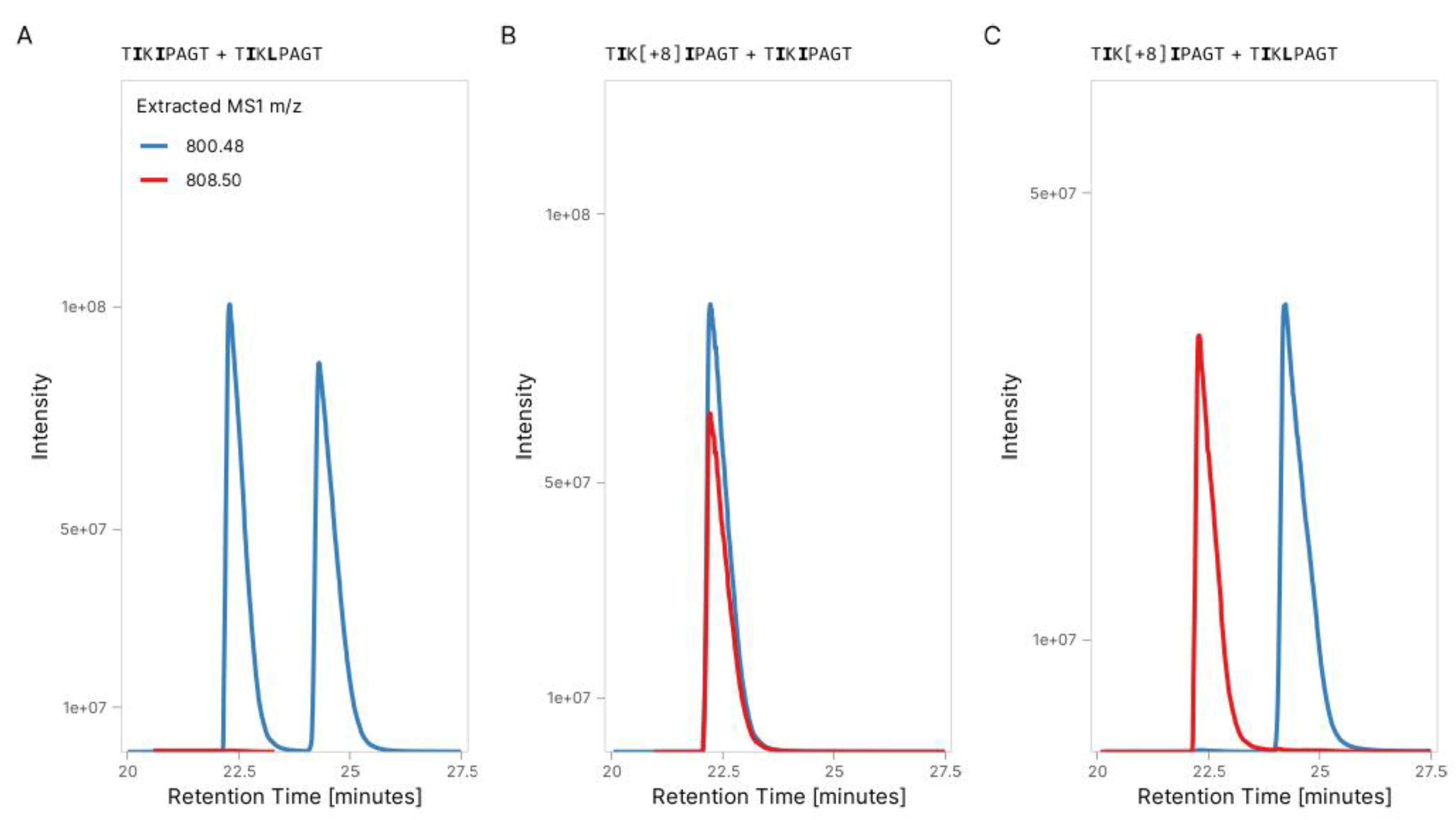

3.1. Validation of Peptide Sequence Using Synthetic Heavy Peptides

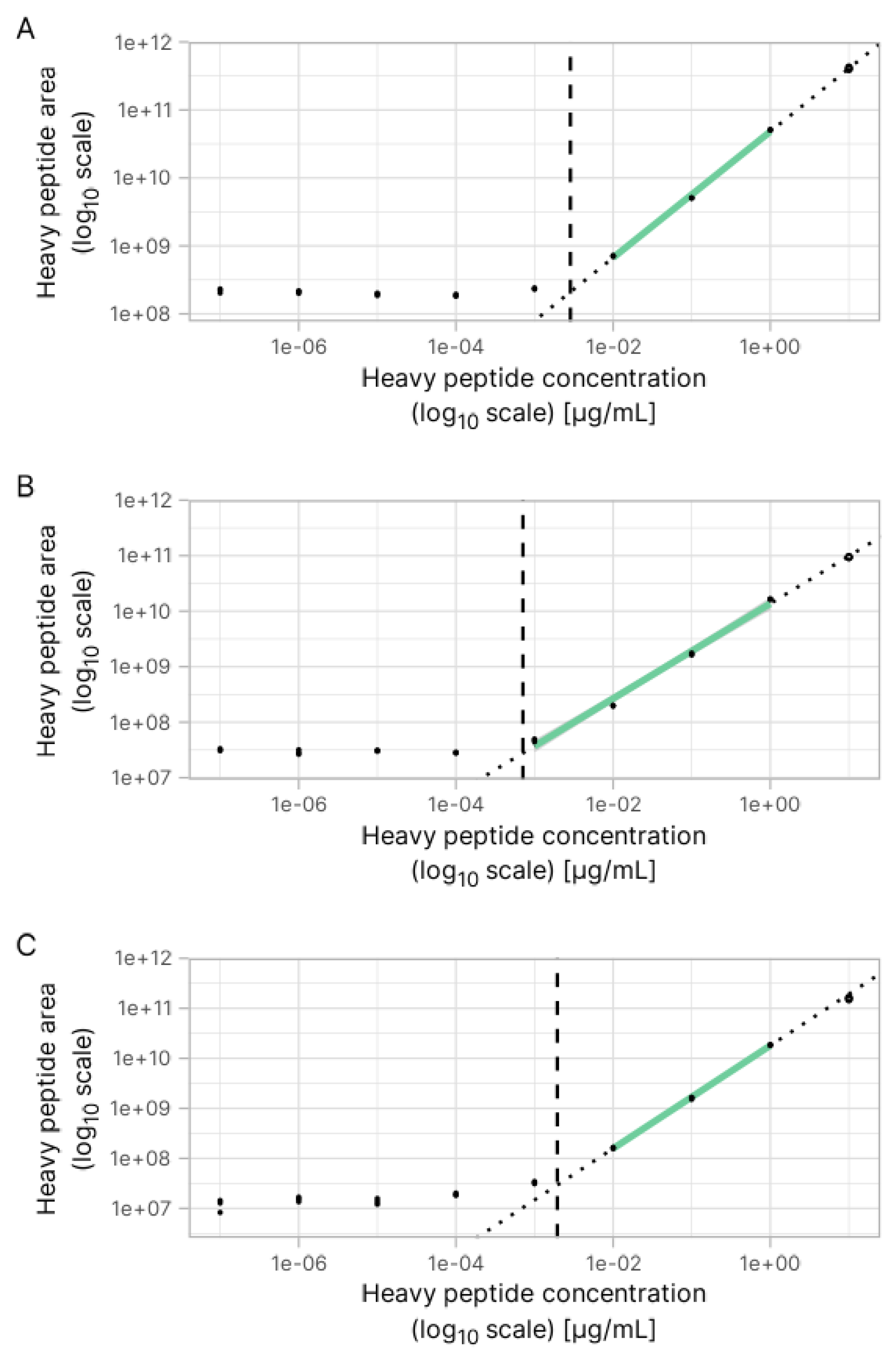

3.2. Estimation of Concentration for Multiple Peptides with Broad Internal Calibration Curves

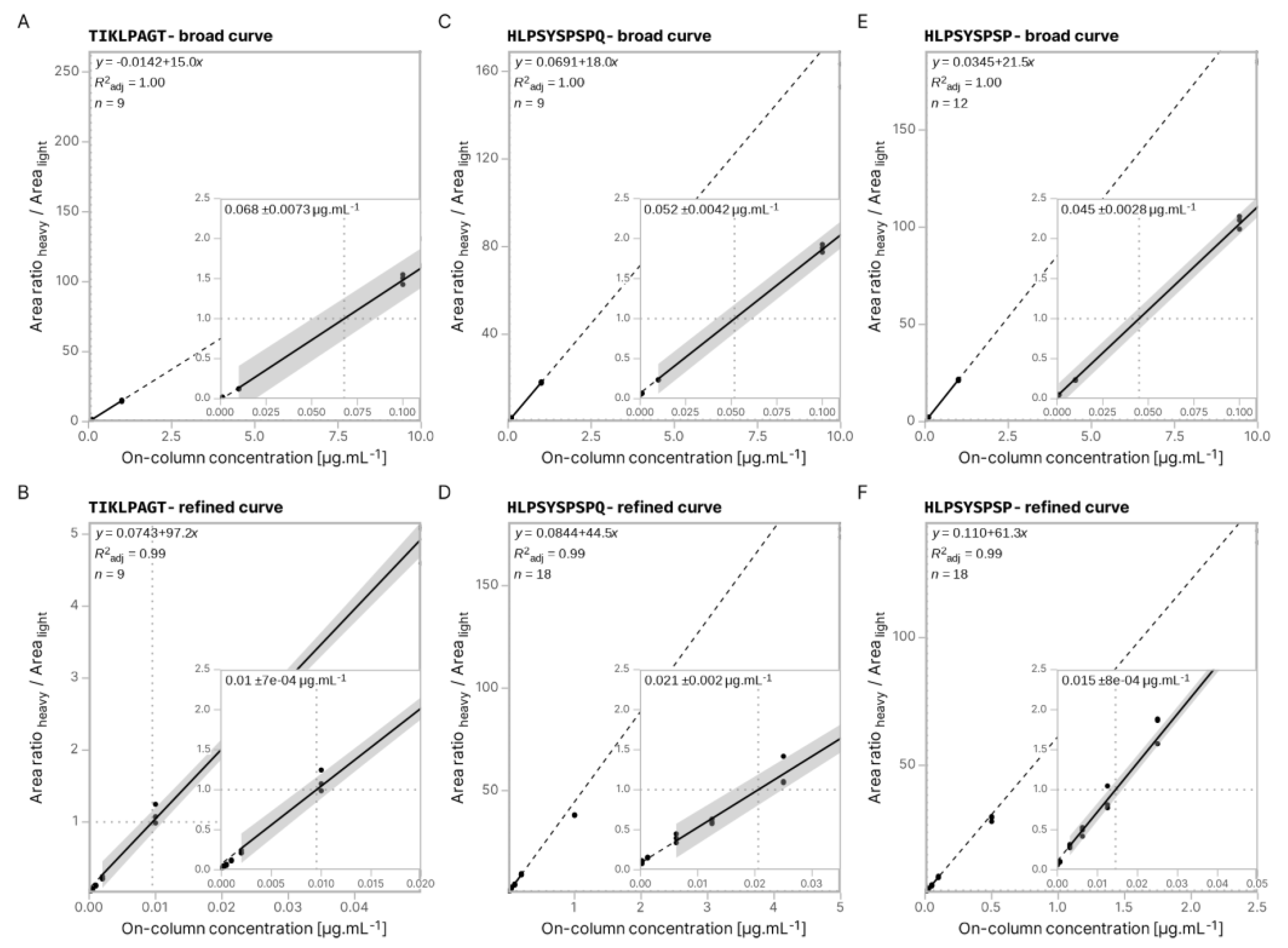

3.4. Absolute Quantification Using Peptide-Specific, Refined Calibration Curves

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRM | Parallel Reaction Monitoring |

| MRM | Multiple Reaction Monitoring |

| XIC | Extracted Ion Chromatogram |

| DDA | Data Dependent Acquisition |

| BCA | Bichinconininc Acid Assay |

References

- Chalamaiah M, Yu W and Wu J 2018 Immunomodulatory and anticancer protein hydrolysates (peptides) from food proteins: A review Food Chem. 245 205–22. [CrossRef]

- Chalamaiah M, Keskin Ulug S, Hong H and Wu J 2019 Regulatory requirements of bioactive peptides (protein hydrolysates) from food proteins J. Funct. Foods 58 123–9. [CrossRef]

- Hayes M and Bleakley S 2018 21 - Peptides from plants and their applications Peptide Applications in Biomedicine, Biotechnology and Bioengineering ed S Koutsopoulos (Woodhead Publishing) pp 603–22.

- He R, Girgih A T, Rozoy E, Bazinet L, Ju X-R and Aluko R E 2016 Selective separation and concentration of antihypertensive peptides from rapeseed protein hydrolysate by electrodialysis with ultrafiltration membranes Food Chem. 197 1008–14. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Liu Q, Xue B, Chen L, Wang Y, Ou S and Peng X 2016 Angiotensin-I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activities and In Vivo Antihypertensive Effects of Sardine Protein Hydrolysate J. Food Sci. 81 H2831–40. [CrossRef]

- Ying X, Agyei D, Udenigwe C, Adhikari B and Wang B 2021 Manufacturing of Plant-Based Bioactive Peptides Using Enzymatic Methods to Meet Health and Sustainability Targets of the Sustainable Development Goals Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5. [CrossRef]

- RUIZ-RUIZ J, DÁVILA-ORTÍZ G, CHEL-GUERRERO L and BETANCUR-ANCONA D 2013 ANGIOTENSIN I-CONVERTING ENZYME INHIBITORY AND ANTIOXIDANT PEPTIDE FRACTIONS FROM HARD-TO-COOK BEAN ENZYMATIC HYDROLYSATES J. Food Biochem. 37 26–35.

- Zhuang H, Tang N and Yuan Y 2013 Purification and identification of antioxidant peptides from corn gluten meal J. Funct. Foods 5 1810–21. [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye F, Vuong T, Duarte J, Aluko R E and Matar C 2012 Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating properties of an enzymatic protein hydrolysate from yellow field pea seeds Eur. J. Nutr. 51 29–37. [CrossRef]

- Kim S E, Kim H H, Kim J Y, Kang Y I, Woo H J and Lee H J 2000 Anticancer activity of hydrophobic peptides from soy proteins BioFactors 12 151–5. [CrossRef]

- Li J-T, Zhang J-L, He H, Ma Z-L, Nie Z-K, Wang Z-Z and Xu X-G 2013 Apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG2 cells induced by corn peptides and its anti-tumor efficacy in H22 tumor bearing mice Food Chem. Toxicol. 51 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Wu W, Zhang M, Sun C, Brennan M, Li H, Wang G, Lai F and Wu H 2016 Enzymatic preparation of immunomodulatory hydrolysates from defatted wheat germ (Triticum Vulgare) globulin Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51 2556–66. [CrossRef]

- Katayama S, Corpuz H M and Nakamura S 2021 Potential of plant-derived peptides for the improvement of memory and cognitive function Peptides 142 170571. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Zhao M, Fan H and Wu J 2022 Emerging proteins as precursors of bioactive peptides/hydrolysates with health benefits Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 48 100914. [CrossRef]

- Regazzo D, Mollé D, Gabai G, Tomé D, Dupont D, Leonil J and Boutrou R 2010 The (193–209) 17-residues peptide of bovine β-casein is transported through Caco-2 monolayer Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 54 1428–35.

- Grootaert C, Jacobs G, Matthijs B, Pitart J, Baggerman G, Possemiers S, Van der Saag H, Smagghe G, Van Camp J and Voorspoels S 2017 Quantification of egg ovalbumin hydrolysate-derived anti-hypertensive peptides in an in vitro model combining luminal digestion with intestinal Caco-2 cell transport Food Res. Int. 99 531–41. [CrossRef]

- Kong S, Zhang Y H and Zhang W 2018 Regulation of Intestinal Epithelial Cells Properties and Functions by Amino Acids ed S Ishihara BioMed Res. Int. 2018 2819154.

- Takeda J, Park H-Y, Kunitake Y, Yoshiura K and Matsui T 2013 Theaflavins, dimeric catechins, inhibit peptide transport across Caco-2 cell monolayers via down-regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase-mediated peptide transporter PEPT1 Food Chem. 138 2140–5. [CrossRef]

- Wang C-Y, Liu S, Xie X-N and Tan Z-R 2017 Regulation profile of the intestinal peptide transporter 1 (PepT1) Drug Des. Devel. Ther. Volume 11 3511–7.

- Ozorio L, Mellinger-Silva C, Cabral L M, Jardin J, Boudry G and Dupont D 2020 The influence of peptidases in intestinal brush border membranes on the absorption of oligopeptides from whey protein hydrolysate: An ex vivo study using an ussing chamber Foods 9 1415.

- Xu Q, Hong H, Wu J and Yan X 2019 Bioavailability of bioactive peptides derived from food proteins across the intestinal epithelial membrane: A review Trends Food Sci. Technol. 86 399–411.

- Castro P, Madureira R, Sarmento B and Pintado M 2016 Tissue-based in vitro and ex vivo models for buccal permeability studies Concepts and models for drug permeability studies (Elsevier) pp 189–202.

- Vermeirssen V, Camp J V and Verstraete W 2004 Bioavailability of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory peptides Br. J. Nutr. 92 357–66. [CrossRef]

- Deacon C F, Nauck M A, Toft-Nielsen M, Pridal L, Willms B and Holst J J 1995 Both subcutaneously and intravenously administered glucagon-like peptide I are rapidly degraded from the NH2-terminus in type II diabetic patients and in healthy subjects Diabetes 44 1126–31.

- Shimizu M, Tsunogai M and Arai S 1997 Transepithelial Transport of Oligopeptides in the Human Intestinal Cell, Caco-2 Peptides 18 681–7.

- Adibi S 1976 Intestinal phase of protein assimilation in man Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 29 205–15. [CrossRef]

- Chabance B, Marteau P, Rambaud J C, Migliore-Samour D, Boynard M, Perrotin P, Guillet R, Jollès P and Fiat A M 1998 Casein peptide release and passage to the blood in humans during digestion of milk or yogurt Biochimie 80 155–65. [CrossRef]

- Lambers T T, Gloerich J, van Hoffen E, Alkema W, Hondmann D H and van Tol E A F 2015 Clustering analyses in peptidomics revealed that peptide profiles of infant formulae are descriptive Food Sci. Nutr. 3 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Corrochano A R, Cal R, Kennedy K, Wall A, Murphy N, Trajkovic S, O’Callaghan S, Adelfio A and Khaldi N 2021 Characterising the efficacy and bioavailability of bioactive peptides identified for attenuating muscle atrophy within a Vicia faba-derived functional ingredient Curr. Res. Food Sci. 4 224–32. [CrossRef]

- Dallas D C, Guerrero A, Parker E A, Robinson R C, Gan J, German J B, Barile D and Lebrilla C B 2015 Current peptidomics: Applications, purification, identification, quantification, and functional analysis Proteomics 15 1026–38.

- Arnold S L, Stevison F and Isoherranen N 2016 Impact of Sample Matrix on Accuracy of Peptide Quantification: Assessment of Calibrator and Internal Standard Selection and Method Validation Anal. Chem. 88 746–53. [CrossRef]

- Arnold S Sample matrix has a major impact on accuracy of peptide quantification: Assessment of calibrator and internal standard selection and method validation.

- Warwood S, Byron A, Humphries M J and Knight D 2013 The effect of peptide adsorption on signal linearity and a simple approach to improve reliability of quantification J. Proteomics 85 160–4. [CrossRef]

- Wei A Systematical Analysis of Tryptic Peptide Identification with Reverse Phase Liquid Chromatography and Electrospray Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry.

- Chauhan S Using Peptidomics and Machine Learning to Assess Effects of Drying Processes on the Peptide Profile within a Functional Ingredient.

- Foreman R E, George A L, Reimann F, Gribble F M and Kay R G 2021 Peptidomics: A Review of Clinical Applications and Methodologies J. Proteome Res. 20 3782–97. [CrossRef]

- van der Kloet F M, Bobeldijk I, Verheij E R and Jellema R H 2009 Analytical Error Reduction Using Single Point Calibration for Accurate and Precise Metabolomic Phenotyping J. Proteome Res. 8 5132–41. [CrossRef]

- Mesmin C, Dubois M, Becher F, Fenaille F and Ezan E 2010 Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry assay for the absolute quantification of the expected circulating apelin peptides in human plasma Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24 2875–84.

- Kandi S, Savaryn J P, Ji Q C and Jenkins G J 2022 Use of in-sample calibration curve approach for quantification of peptides with high-resolution mass spectrometry Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 36 e9377. [CrossRef]

- Rauniyar N 2015 Parallel Reaction Monitoring: A Targeted Experiment Performed Using High Resolution and High Mass Accuracy Mass Spectrometry Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 28566–81. [CrossRef]

- Steen H and Mann M 2004 The abc’s (and xyz’s) of peptide sequencing Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5 699–711. [CrossRef]

- Cal R, Davis H, Kerr A, Wall A, Molloy B, Chauhan S, Trajkovic S, Holyer I, Adelfio A and Khaldi N 2020 Preclinical Evaluation of a Food-Derived Functional Ingredient to Address Skeletal Muscle Atrophy Nutrients 12 2274. [CrossRef]

- MacLean B, Tomazela D M, Shulman N, Chambers M, Finney G L, Frewen B, Kern R, Tabb D L, Liebler D C and MacCoss M J 2010 Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 26 966–8.

- Pino L K, Searle B C, Bollinger J G, Nunn B, MacLean B and MacCoss M J 2020 The Skyline ecosystem: Informatics for quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics Mass Spectrom. Rev. 39 229–44. [CrossRef]

- Krieger J, Xin L and Shan B (Paul) 2020 Multi-User, High-Throughput PEAKS Online Workflow, for large scale DIA and DDA Proteomic Analysis J. Biomol. Tech. JBT 31 S22–3.

- Fernández-Costa C, Martínez-Bartolomé S, McClatchy D B, Saviola A J, Yu N-K and Yates J R I 2020 Impact of the Identification Strategy on the Reproducibility of the DDA and DIA Results J. Proteome Res. 19 3153–61.

- Muggeo V M R 2003 Estimating regression models with unknown break-points Stat. Med. 22 3055–71. [CrossRef]

- Muggeo V M R 2008 segmented: an R package to fit regression models with broken-line relationships. R News 8 20–5.

- Gu H, Zhao Y, DeMichele M, Zheng N, Zhang Y J, Pillutla R and Zeng J 2019 In-Sample Calibration Curve Using Multiple Isotopologue Reaction Monitoring of a Stable Isotopically Labeled Analyte for Instant LC-MS/MS Bioanalysis and Quantitative Proteomics Anal. Chem. 91 2536–43. [CrossRef]

- Zheng N, Taylor K, Gu H, Santockyte R, Wang X-T, McCarty J, Adelakun O, Zhang Y J, Pillutla R and Zeng J 2020 Antipeptide Immunocapture with In-Sample Calibration Curve Strategy for Sensitive and Robust LC-MS/MS Bioanalysis of Clinical Protein Biomarkers in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tumor Tissues Anal. Chem. 92 14713–22. [CrossRef]

- Bateman N W, Goulding S P, Shulman N J, Gadok A K, Szumlinski K K, Maccoss M J and Wu C C 2014 Maximizing Peptide Identification Events in Proteomic Workflows Using Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13 329–38. [CrossRef]

- Gillette M A and Carr S A 2013 Quantitative analysis of peptides and proteins in biomedicine by targeted mass spectrometry Nat. Methods 10 28–34.

- Bourmaud A, Gallien S and Domon B 2016 Parallel reaction monitoring using quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer: Principle and applications PROTEOMICS 16 2146–59. [CrossRef]

- Gallien S, Bourmaud A, Kim S Y and Domon B 2014 Technical considerations for large-scale parallel reaction monitoring analysis Spec. Issue Can Proteomics Fill Gap Genomics Phenotypes 100 147–59. [CrossRef]

- Kimanani E K 1998 Bioanalytical calibration curves: proposal for statistical criteria1Presented at the Analysis and Pharmaceutical Quality Section of the Eleventh Annual American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists Meeting, October 1996, Seattle, Washington, USA.1 J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 16 1117–24.

- Ronsein G E, Pamir N, von Haller P D, Kim D S, Oda M N, Jarvik G P, Vaisar T and Heinecke J W 2015 Parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) and selected reaction monitoring (SRM) exhibit comparable linearity, dynamic range and precision for targeted quantitative HDL proteomics J. Proteomics 113 388–99.

- Nwachukwu I D and Aluko R E 2019 A systematic evaluation of various methods for quantifying food protein hydrolysate peptides Food Chem. 270 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Boersema P J, Raijmakers R, Lemeer S, Mohammed S and Heck A J R 2009 Multiplex peptide stable isotope dimethyl labeling for quantitative proteomics Nat. Protoc. 4 484–94. [CrossRef]

- Greer T, Lietz C B, Xiang F and Li L 2015 Novel isotopic N,N-Dimethyl Leucine (iDiLeu) Reagents Enable Absolute Quantification of Peptides and Proteins Using a Standard Curve Approach J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 26 107–19.

- DeSouza L V, Taylor A M, Li W, Minkoff M S, Romaschin A D, Colgan T J and Siu K W M 2008 Multiple Reaction Monitoring of mTRAQ-Labeled Peptides Enables Absolute Quantification of Endogenous Levels of a Potential Cancer Marker in Cancerous and Normal Endometrial Tissues J. Proteome Res. 7 3525–34. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Wen B, Zhou B, Yang L, Cha C, Xu S, Qiu X, Wang Q, Sun H, Lou X, Zi J, Zhang Y, Lin L and Liu S 2013 Quantitative Analysis of the Human AKR Family Members in Cancer Cell Lines Using the mTRAQ/MRM Approach J. Proteome Res. 12 2022–33. [CrossRef]

- Gilani G S, Xiao C and Lee N 2008 Need for Accurate and Standardized Determination of Amino Acids and Bioactive Peptides for Evaluating Protein Quality and Potential Health Effects of Foods and Dietary Supplements J. AOAC Int. 91 894–900. [CrossRef]

- Rutherfurd-Markwick K J 2012 Food proteins as a source of bioactive peptides with diverse functions Br. J. Nutr. 108 S149–57. [CrossRef]

- Mamone G, Picariello G, Caira S, Addeo F and Ferranti P 2009 Analysis of food proteins and peptides by mass spectrometry-based techniques Adv. Sep. Methods Food Anal. 1216 7130–42. [CrossRef]

- Anon THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development.

| Peptide of interest | Spiked internal standard | ||

| Peptide Sequence | Molecular Weight (Da) | Peptide Sequence | Molecular Weight (Da) |

| HLPSYSPSP | 984.4785 | HLPSYSPSP[Label:13C(5)15N(1)] | 990.4923 |

| HLPSYSPSPQ | 1112.5371 | HLP[Label:13C(5)15N(1)]SYSPSPQ | 1118.5509 |

| TIKIPAGT | 800.4876 | TI[Label:13C(6)15N(2)]KIPAGT | 808.4876 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).