1. Introduction

Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent of gray mold, is a highly relevant phytosanitary problem in many cultivated plant species. It is an ubiquitous phytopathogenic fungus with a very wide host range, including species of enormous economic importance [

1]. It can infect all types of organs and tissues and causes problems both in the field and during post-harvest. Its life cycle is complex. As a saprophyte it can survive in the field on senescent or decomposing plant tissues. As a necrotrophic pathogen it infects living plant tissues, causing the death of the host cells to obtain from the decomposing tissues the nutrients it needs for its growth and multiplication [

2,

3]. The asexual spores produced on the conidiophores of the mycelium proliferating on the colonized tissues constitute the main structure for dispersion and infection. Mycelium itself is an important source of inoculum in the field. The fungus produces resistance structures, the sclerotia, which allow the pathogen to overcome adverse environmental conditions, such as low winter temperatures. When favorable conditions are restored, the sclerotia germinate, producing mycelium that actively sporulates. The sclerotia also play a fundamental role in the sexual cycle of the pathogen, acting as a reproductive structure provided by the female parent in crosses in which they are fertilized by microconidia produced by an isolate of compatible mating type that acts as a male parent. The ascospores produced in the derived fruiting bodies, the apothecia, also contribute to the dispersion of the pathogen and, like the spores derived from the asexual phase, are infective.

The fact that a species presents a sexual phase in its life cycle offers an extremely useful experimental tool in the context of the genetic analysis of traits: the possibility to perform crosses. Early studies on the mating type of

B. cinerea indicated that it is a heterothallic species [

4]. The sexual type is determined by a single

locus (

MAT1) with two idiomorphs,

MAT1-1 and

MAT1-2, initially assigned arbitrarily to two tester isolates, derived from single ascospores, SAS56 and SAS405, sexually compatible, generated in the course of the optimization of methods to perform crosses under laboratory conditions [

5,

6]. Both sexual types are found in similar proportions in natural populations. Although infrequently, it is also possible to find pseudo-homothallic isolates in nature that can be crossed with isolates of both sexual types [

6,

7,

8]. Even though producing apothecia from crosses in the laboratory is a routinary practice nowadays, their presence in nature is very limited, if any [

9]. This observation could be indicative that the sexual phase of the fungus is infrequent in the field. However, it is difficult to explain the high levels of genetic diversity observed in natural populations of

B. cinerea if the contribution of a powerful mechanism for generating genetic diversity such as meiotic recombination, characteristic of sexual reproduction, is not considered. Different evidence, largely derived from population genetics studies [

10,

11,

12], suggest that meiotic recombination and sexual reproduction occur very frequently in nature.

The existence of genetic variation constitutes the second fundamental pillar on which genetic analysis is based.

B. cinerea is well known as a very plastic organism whose natural populations present very high levels of phenotypic diversity. This variation has been described in relation to diverse physiological aspects, such as vegetative growth, secondary metabolism, resistance to fungicides, virulence and responses to light. Numerous works have also demonstrated, by analyzing molecular variation, that

B. cinerea populations present a high degree of genetic variability [

13,

14,

15,

16]. In recent years, the availability of well annotated reference genomes [

17,

18] and the resequencing of the genome of numerous field isolates have allowed us to confirm this high genetic variability across the genome [

10,

11,

19]. The phenotypic diversity of the individuals that make up the populations is organized around the pool of genetic variability. Sometimes, genetic variation determines notable functional alterations, even loss of function, in genetic factors with a major effect on a certain character, or subtle alterations in the function of the different genetic factors involved in determining polygenic characters. In other cases, genetic variation is silent or affects intergenic regions and does not determine functional alterations. Whatever its nature, the existence of variation and the possibility of performing crosses allow the construction of genetic maps and the development of strategies based on association analysis in segregating offspring to identify genes with a major effect or Quantitative Trait

Loci (QTLs) involved in determining traits. Bulked Segregant Analysis (BSA) is a QTL mapping method based on the identification of molecular markers associated with genes involved in the determination of traits of interest [

20,

21]. It is particularly appropriate in the analysis of offspring populations that show clearly contrasted alternative phenotypes characteristic of the parents involved in a certain cross. Its application has reported successful results in the genetic analysis of non-aggressive mycelial field isolates of

B. cinerea [

22]. On the other hand, the determination of variation in populations of individuals, and ideally at the genomic level, makes it possible to carry out Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) that are not dependent on the offspring of crosses. When applied to the

Botrytis-Arabidopsis pathosystem, indications of a complex architecture of virulence in the fungus have been found [

23]. A similar trend is observed when investigating the interaction between

B. cinerea and wild and domesticated tomato genotypes [

19]. Candidate polymorphisms and genes associated with virulence have been reported in both systems.

Basic research on the biology of

B. cinerea and its necrotrophic lifestyle has revealed a close relationship between virulence, development and light sensing. Early work already indicated that

B. cinerea can sense light of different wavelengths and that this stimulus regulates differentiation programs. Genome analysis shows that

B. cinerea possesses 11 photoreceptors whose activities cover the light spectrum (reviewed by Schumacher, 2017) [

24]. In nature most strains respond to light like the B05.10 sequenced reference strain and undergo photomorphogenesis, that is, light exposure stimulates the production of macroconidia while its absence stimulates the production of sclerotia [

25]. These strains are classified as light-responsive strains. But natural populations also show variation regarding this ability and “blind strains” displaying the same phenotype regardless of the light regime applied, “always conidia”, “always sclerotia” or “always mycelia”, are found. These strains are assumed to be deficient in key components of the light sensing machinery. Characterization of “always conidia” strains demonstrates that this phenotype may result from alterations in different genes. In the wild strains T4 and 1750 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) in gene

bcvel1 (member of the VELVET complex) determining stop codons, and therefore generating truncated versions of the encoded protein, were found to be responsible for the observed phenotype [

26,

27]. Deletion of any

VELVET complex member determined inhibition of sclerotial development, increased conidiation, increased conidial melanogenesis and, remarkably, reduced virulence [

26,

28,

29]. This demonstrates a role of VELVET in light sensing and development and pathogenicity in

B. cinerea [

28,

29]. A similar phenotype has been described in mutants altered in the

B. cinerea White Collar Complex (

WCC), the key component involved in light perception and in the coordination of light response in

B. cinerea. The functional WCC is the heterodimeric Transcription Factor (TF) integrated by the

bcwcl1 and

bcwcl2 gene products, two GATA-type transcription factors. The ∆

bcwcl1 mutants generated in the B05.10 background show hyperconidiation and lack of sclerotial development. They also show precocious and persistent conidiation. Interestingly, they show reduced virulence, but only when incubated in photoperiod conditions, not in permanent darkness. Additionally, the mutants are hypersensitive to oxidative stress caused by H

2O

2 [

30]. By applying a random mutagenesis approach another virulence-related factor, BcLTF1 (for

B. cinerea Light Responsive Transcription Factor 1), was identified and described in the B05.10 strain [

31]. The mutants, generated through

A. tumefaciens-Mediated Transformation (ATMT), were first selected based on their reduced virulence. Detailed physiological and transcriptomic analysis uncovered the functions of BcLTF1 in the regulation of light-dependent differentiation, the equilibrium between production and scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and secondary metabolism. Specifically, the mutants were unable to produce sclerotia, were found to hyperconidiate and be hypersensitive to light and oxidative stress.

bcltf1, encodes a GATA-type TF homologous to the

Neurospora crassa SUB-1 [

32] and the

Aspergillus nidulans NsdD [

33]. In these model systems, the TF has demonstrated to participate in the modulation of light responses and differentiation.

Our group is interested in the characterization of the natural populations of

B. cinerea from the vineyards of Castilla y León (Spain), in the evaluation of their genetic diversity and in the identification of natural mutant strains altered in pathogenicity [

16]. The result of these evaluations was the identification of non-aggressive mycelial isolates whose characterization led to the identification of a gene with a major effect on development and pathogenicity in

B. cinerea,

Bcin04g03490, initially catalogued as a gene encoding a TF, since the encoded protein has a Gal4-type DNA binding domain [

22]. During those evaluations, a strain with the “always conidia” phenotype was also isolated, which was deficient in its ability to infect

Phaseolus vulgaris and

Vitis vinifera leaves. Here we describe the physiological characterization of this strain, Bc116, and the application of a BSA strategy to map the mutation and identify the altered gene. This analysis demonstrates that strain Bc116 is a natural mutant altered in gene

bcltf1.

3. Discussion

Natural variation on populations of fungal pathogens is of key importance to explain their biology. Whether induced or natural, genetic analysis of variation makes it possible to address the genetic dissection of traits.

B. cinerea is considered one the most important fungal pathogens [

34] and has attracted deep interest in the scientific community. In recent decades it has become the model organism to study the necrotrophic lifestyle. Experimental evidence is accumulating outlining the mode of action of a pathogen that establishes interaction with the host by manipulating and exploiting essential biological processes of the plant for its own benefit [

35]. Recent research shows that

B. cinerea has a remarkable capacity to sense light stimuli that the fungus integrates to take developmental decisions, and several authors consider

B. cinerea as a valuable model system to expand our knowledge of fungal photobiology [

24,

30]. Our work, focused on the characterization of natural variation in

B. cinerea populations, supports the existence of close relationships at the level of their genetic determination and regulation between the processes involved in pathogenicity and responses to light, since the identified natural mutants altered in their ability to infect the host plant, Bc116 among them, but not only [

22], also show alterations in their responses to light.

Genetic analysis demonstrates that, although Bc116 shows alterations in different aspects related to pathogenicity, development and responses to light, they all depend on a single gene. This situation facilitates the consideration of procedures such as BSA to map the mutation and identify the altered gene. Although originally developed to map and identify QTLs [

21], BSA is particularly well suited for the identification of genes with a major effect on the phenotype(s) of interest. In

B. cinerea, our group has previously successfully applied this methodology [

22]. In the work here presented, Bc116 has been shown to harbour levels of polymorphism like those reported for the Bc448 isolate [

22] and for other field isolates [

10,

19]. By adapting the experimental framework previously considered, it has been possible to perform an association mapping covering the entire genome of our

B. cinerea isolates offering a resolution allowing to map the mutation in isolate Bc116 to a 200 kb genomic region in Chr14. The availability of a fully sequenced and accurately annotated reference genome has become an unvaluable tool. The detailed analysis of the mapped region under the consideration of the two criteria highlighted, a mutation of expected high impact and affecting a genetic factor with possible regulatory function, led to the selection of

bcltf1 as the most likely candidate. The restoration of the wild type phenotype by transformation with the allele derived from strain B05.10 demonstrates that

bcltf1 is the altered gene in Bc116.

Former studies performed by Schumacher et al. [

31] identified and described BcLTF1 as a virulence factor in

B. cinerea. By means of ATMT, they generated three different mutants in B05.10 that displayed reduced aggressiveness on bean plants. The three mutants were found to harbour a T-DNA insertion in the upstream region of

bcltf1. B05.10-Δ

bcltf1 mutants showed the same phenotype as those T-DNA mutants. These mutants were also altered in several differentiation and development processes regulated by the light stimulus. The results on the characterization of the natural mutant isolate Bc116 supports the regulatory role for BcLTF1 in virulence and light responses. In addition, it broadens the knowledge about the role of this factor in the biology of

B. cinerea.

Our analysis indicates that the isolate Bc116, like the B05.10-Δ

bcltf1 mutants, shows a reduction in growth in all light regimes, and that this reduction is greater under permanent light conditions. It also shares with them the early sporulation and hyperconidiation phenotypes, but its capacity to produce spores is even greater. It is interesting to note that Bc116 does not show the stimulation of sporulation by light described as characteristic of

B. cinerea isolates [

24]. Remarkably, a similar behaviour is observed in the field isolate Bc448, supporting that, in relation to these responses, variation in natural populations is certain.

In this comparison it is more striking the ability of Bc116 to produce sclerotia. It is true that the pattern of sclerotia production is different from that shown by strain Bc448, which is very similar to that of B05.10, but under the experimental conditions used in this work to stimulate sclerotia production, DD and low temperatures for about one month, Bc116 indeed produced sclerotia. These conditions are similar to those reported for the characterization of the B05.10-

∆bcltf1 mutants [

31]. Therefore, it is possible to assume that the differences observed between the B05.10-

∆bcltf1 mutants and Bc116 are due to their different genetic backgrounds. The fact that the pattern of sclerotia production shows segregation in the offspring of the Bc116 x Bc448 cross and that the complemented transformants show a pattern of sclerotia production resembling that of the Bc448 isolate indicates that the pattern of sclerotia formation is under the control of BcLTF1 and that segregation of other genetic factors in both parental genetic backgrounds likely determine differences in individuals. On the other hand, although the size of the sclerotia of Bc116 limits the possibility of their utilization in crosses, this isolate was successfully used as the male parental strain in our crosses, demonstrating that it is sexually competent.

The behaviour of Bc116 in inoculations on bean leaves in LD is similar to that described for the B05.10-

∆bcltf1 mutants under the same conditions. A delay is observed in the progress of infection in comparison with the aggressive isolate Bc448, which in our analysis is verified macroscopically and microscopically at 24 hpi. It is a delay, because the formation of dispersive lesions is evident at 72 hpi and the plant tissues are fully colonized at later stages. These observations corroborate the descriptions made in the B05.10-

∆bcltf1 mutants. However, it is interesting to note that, when extending the analysis to other light regimes, it is found that the factor limiting the mutant’s capacity to cause infection is the light exposure during the early phases of the plant-fungus interaction. In the B05.10-

∆bcltf1 mutants, the ability to penetrate the onion epidermis was analysed in inoculations carried out both, with spores and with non-sporulating mycelium. No differences were observed in comparison with the wild type isolate and it was concluded that the delay in infection was due to limitations in colonization, not in penetration. However, these evaluations were carried out only in DD. Our analysis detects the same situation in DD, but it is verified that in LL, light reduces the efficiency of penetration into the onion epidermis of both, spores and mycelium. This indicates that the Bc116 isolate has limitations to cope with the effect of light during the early stages of development, which

in planta involves penetration. Therefore, it may be concluded that the delay observed in the infection process of the

bcltf1 mutants in LL is due, at least in part, to defects in penetration. The work by Schumacher et al. [

31], found that their B05.10-

∆bcltf1 mutants are hypersensitive to oxidative stress. The authors cleverly demonstrated that the delay in the infection process and the reduced growth observed

in planta is due to the limited capacity of the

bcltf1 mutants to cope with the oxidative stress that arises during light exposure. Bc116 is also hypersensitive to the oxidative stress produced by exposure to H

2O

2 during saprophytic growth, a sensitivity accentuated in LL and LD, results supporting their observations.

The impairment of the infecting capacity of Bc116 is most noticeable on

Vitis leaves in LL, where a complete incapacity to establish the interaction is observed. As it is the same isolate on two different hosts, the more extreme limitation observed on

Vitis should be attributed to differential properties of the host, either intrinsic or related to the defence mechanisms activated in response to the presence of the pathogen, which differentially affect the

B. cinerea wild type isolate and the

bcltf1 mutant. Since on bean leaves the sensitivity to oxidative stress accounts for the reduction in aggressiveness, it is possible to assume also on

Vitis leaves an important role for the ROS produced by the plant tissues in response to the presence of the pathogen, which constitute one of the earliest cellular responses upon pathogen recognition [

36]. The timing or the intensity of this production could be different on

Vitis leaves. It will be of interest determining if other mechanisms or metabolites, specifically activated or produced on

Vitis leaves, sum their effect to that of the oxidative stress conditions created during the early stages of the interaction to block the ability of the natural

bclft1 mutant to cause infection.

It is striking that on

Vitis leaves the effects of light exposure during the early stages of the interaction determine alterations in the fungus that are maintained over time once the inoculated tissues are transferred to dark conditions (the dark phase in LD). This implies that during the first moments of the attempted infection, the conditions created by the presence of light in the environment in which the plant tissues interact with the infective structures of the fungus determine alterations in the development program of the pathogen that are irreversible. It is interesting to note that the ROS play crucial roles in development and differentiation processes in fungi [

37]. The interaction described in this work may offer an interesting experimental system to identify specific targets of the ROS that are key in the definition of these differentiation programs in

B. cinerea.

In

N. crassa, the most deeply investigated model system in fungal photobiology, SUB-1 functions as an early light-responsive TF which is involved in regulating some early and most late light-responses [

32]. In the plant pathogen

B. cinerea the homologous BcLTF1 responds to light and regulates light dependent processes [

31] and, in addition, it regulates pathogenicity related functions. Our work has characterized a natural mutant, Bc116, altered in

bcltf1. Its physiological and genetic analysis broadens our knowledge of the functions regulated by this TF and supports its fundamental role in the regulation of light responses, differentiation and pathogenicity in

B. cinerea.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Organisms and Growth Conditions

The

B. cinerea isolates B05.10 [

38], Bc116 and Bc448 [

16] were used in this study. Fungal cultures were established from frozen conidia stored on 15% glycerol (v/v) at -80°C. Fungal isolates were grown at 22°C under the light/darkness conditions required for each experiment. Light was generated by Cool White Osram L 36W/840 fluorescent bulbs.

Common bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cv Blanca Riñón were kindly provided by Centro de la Legumbre (Pajares de la Laguna, Salamanca, Spain). Plants were grown in natural substrate for 2 weeks in the greenhouse under a 16/8 h light/darkness photoperiod. Vitis vinifera plants variety Juan García were maintained in the greenhouse in the same conditions.

4.2. Germination, Conidiation and Saprophytic Growth Experiments

To study the fungal germination patterns the strains were grown on MEA (Malt Extract Agar, Difco) plates for 3 weeks at 22°C and permanent darkness. Conidia were harvested and suspensions of 5x10

5 conidia/mL were prepared in PDB (Potato Dextrose Broth, Difco) at half concentration. 60 µL drops of the conidial suspensions were placed in the center of empty Petri dishes that were incubated without agitation inside a wet chamber at 22°C under continuous light or continuous darkness. Samples were imaged at 6 hpi using a MD-E3-6.3 camera (MicrosCopiaDigital, Industrial Digital Camera) adapted to a microscope Leica DLMB (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim). The percentage of germinated conidia was quantified according to the previously described classification of the conidia developmental stages [

39]. Five plates per condition and strain were analyzed in each experiment and experiments were repeated three times.

To analyse conidiation rates, the fungal isolates were grown on MEA for 4 days at 22°C and permanent darkness. Agar plugs of 5 mm in diameter from the edge of the colony were taken and placed in the center of Petri dishes containing MEA. The plates were maintained at 22°C and different light conditions (LL, 16/8 h LD, DD) for 3 weeks and then the conidia were harvested from each plate. The number of conidia produced was estimated using a Thoma cell counting chamber. Three plates per strain and experiment were analysed and three independent biological experiments were carried out.

The fungal saprophytic growth was determined on MEA. Fungal isolates were grown, and conidia suspension were prepared as described above for the germination assays; 10 µL drops of the conidial suspension were placed in the center of Petri dishes containing MEA. The plates were incubated at 22°C for 5 days and then the diameter of the colony was measured. Different light conditions were assayed, LL, LD and DD. Three plates per strain and light condition were inoculated in each biological experiment and three independent experiments were performed. For the evaluation of the effect of the oxidative stress the isolates were grown on MEA supplemented with 7.5 mM of H2O2 using agar mycelium plugs of 5 mm in diameter as initial inoculum and measuring the colony diameter 96 hpi.

The capacity of fungal isolates to produce sclerotia was evaluated on MEA plates. Mycelium plugs taken from the edge of actively growing colonies were placed in the center of Petri dishes containing the media and incubated at 22°C for 4-5 days under permanent darkness. Afterwards, plates were incubated at 2-4°C for 4 weeks and then the number, size and distribution of sclerotia were analysed.

4.3. Penetration Analysis

The ability of fungal isolates to penetrate host tissues was analyzed on onion epidermal cells. Strips of onion epidermis were cut and placed on a slide with the hydrophobic layer side-up. 10 µL drops of a conidial suspension at 5x104 conidia/mL prepared in water, or non-sporulating mycelium plugs of 3 mm in diameter taken from the edge of actively growing colonies, were placed on the strips. The samples were maintained at 22°C and the light conditions required inside closed plastic boxes to ensure a high humidity environment. At the time of analysis, the mycelium plugs were removed. In both inoculations, 10 µL of lactophenol blue solution (Fluka, SIGMA) were placed on each inoculation spot and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the staining solution was removed and the samples were washed with distilled water. Samples were imaged using a MD-E3-6.3 camera (MicrosCopiaDigital, Industrial Digital Camera) adapted to a microscope Leica DLMB (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim).

4.4. Inoculation Assays

The pathogenicity of fungal isolates was studied according to previously described methods [

16,

22]. The inoculation on common beans was performed with whole plants that were placed inside transparent plastic boxes with water on the bottom; the inoculation on

Vitis was carried out on detached leaves whose petioles were inserted in wet floral foam and then placed inside plastic trays with wet paper on the bottom. In both systems 5 mm in diameter plugs of fresh mycelium taken from the edge of fungal colonies actively growing on MEA plates were placed on non-wounded leaves. Four plugs and one isolate were used per leaf in the case of common bean inoculations, and four plugs and two isolates were used per leaf in the case of

Vitis leaves. At least 5 leaves were inoculated per fungal isolate and condition in each experiment. The experiments were repeated in a randomized design at least three times. The inoculated materials were maintained in closed boxes or trays at 22°C and the light conditions required in each case. Aggressiveness was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the lesions 3 and 4 dpi for common bean plants and

Vitis leaves, respectively.

For the staining of inoculated common bean leaves, the mycelium plugs were removed 24 hpi and the area of the inoculation cut. Samples were immersed into a solution of lactophenol blue:ethanol (1:2) and incubated for 1 min at 100°C, cooled at room temperature and incubated again for 30 sec at the same temperature. After cooling at room temperature, the staining solution was removed and the samples were washed with absolute ethanol. Images were acquired using a Leica DFC495 camera adapted to a Leica 205FA stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany) and analyzed using the LAS software v3.6.0 (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany).

4.5. Standard Molecular Techniques

Fungal genomic DNA was isolated from mycelium cultured on cellophane sheets placed onto MEA plates. All the DNA purifications followed previously described procedures [

40].

The PCR reactions were carried out using the DNA Polymerase from Biotools with the exception of the amplification of the

bcltf1 allele which was performed using the Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase from ThermoFisher Scientific. In both cases the reactions were performed according to manufacturer’s recommendations. All the primers used in this work are listed in

Table S2.

The Gateway BP Clonase II Enzyme Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used in the cloning reactions of the

bcltf1 allele in plasmid pWAM6 [

22].

4.6. B. cinerea Transformation

B. cinerea protoplasts were transformed using the method described by ten Have et al. [

41], with modifications as specified by Reis et al. [

42] and Leisen et al. [

43]. Protoplasts were generated using a 1% concentration of Vinotaste Pro (Lamothe Abiet, Canejan, France), an enzymatic blend of chitinases and glucanases, along with 0.1% Yatalase (Takara, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France).

4.7. Construction of Bc116-bcltf1 Complemented Transformants

The wild type allele of

bcltf1 from the B05.10 strain was cloned into plasmid pWAM6 [

22], which contains a hygromycin (

Hph) resistance cassette from pOHT [44], using the Gateway cloning technology. To this end, the B05.10-

bcltf1 allele was amplified as a 4.7 kb fragment with specific oligonucleotides harboring extensions with

attB sequences (

Table S2). Upon recombination facilitated by the BP clonase, plasmid pVPM1 was generated. From it, a 7.7 kb linear fragment containing the B05.10-

bcltf1 allele and the

Hph cassette was amplified using specific oligonucleotides (

Table S2). The PCR product was used to transform Bc116, and transformants able to grow on selective media were successively transferred to fresh selective plates. Monosporic cultures were obtained from the selected transformants.

4.8. Crosses

Crosses between Bc448 and Bc116 were performed following the procedures established by Faretra et al. [

5,

6]. Mature apothecia were collected and crushed in water to release the ascospores. The suspension was filtered through glasswool and plated on MEA plates. Individual ascospore germlings were transferred 24 h later to fresh MEA plates for propagation.

4.9. Sequencing and Determination of Polymorphisms

For this study, four data sets were used. The genome of Bc448 was previously sequenced [

22] (Accession number SRR13700579). Genomic DNA of the parental strain Bc116 and of both descendant groups—those resembling Bc448 and those resembling Bc116—in the cross Bc116 x Bc448 were sequenced using Illumina technology by Novogene (Cambridge, UK) (Accession numbers: Bc116 Genome – SAMN46863733; Pool aggressive progeny (A) – SAMN46863735; and Pool non-aggressive progeny (B) – SAMN46863734). The sequences were mapped to the genome of the reference isolate, B05.10 (ASM14353v4), and polymorphisms were subsequently extracted using the tools available in Geneious Prime

® 2023.1.1 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand).

4.10. BSA

For the BSA analysis a list of SNPs of each parental isolate in comparison with the B05.10 reference genome was generated with Geneious Prime® 2023.1.1 (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand). From these, two lists of SNPs exclusive of either Bc448 or Bc116, were derived. From the progeny, two groups of individuals were selected: Group A, consisting of 60 individuals resembling the parental isolate Bc448, and Group B, consisting of 60 individuals resembling the parental isolate Bc116. Genomic DNA was extracted from each individual isolate, and equal amounts of DNA from the 60 individuals in each group were pooled together to form two bulk DNA samples. These genomic DNA pools were sequenced by Illumina, and the frequencies of the polymorphisms specific of either Bc448 or Bc116 were determined in each pool. For the association mapping analysis, only high-quality SNPs (quality score >33) were considered. The distribution of polymorphisms specific to each parental isolate in the two progeny groups was analyzed by calculating the difference in the frequency of each polymorphism between DNA pool B and DNA pool A (f “polymorphism x” in B - f “polymorphism x” in A). This difference generates a SNP index (Y-axis) that was plotted against the chromosomal coordinates (X-axis) of the reference genome B05.10. For markers unlinked to the locus responsible for the phenotypic difference, allelic frequencies were expected to be similar in both pools, causing the SNP index plot for these chromosomal regions to fluctuate around the “0” value. Conversely, for markers linked to the locus of interest, allelic frequencies differed significantly between the DNA pools, with larger differences observed for markers more closely linked to the locus. The SNP index reached maximum values (close to +1) for Bc116-specific alleles predominantly found in the non-aggressive, hyperconidiating progeny DNA pool and minimum values (close to -1) for Bc448-specific alleles predominantly found in the aggressive progeny DNA pool.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

All the statistical analysis were performed with the help of the software Statistix 10 (Analytical Software, Tallahassee, Florida, USA).

Figure 1.

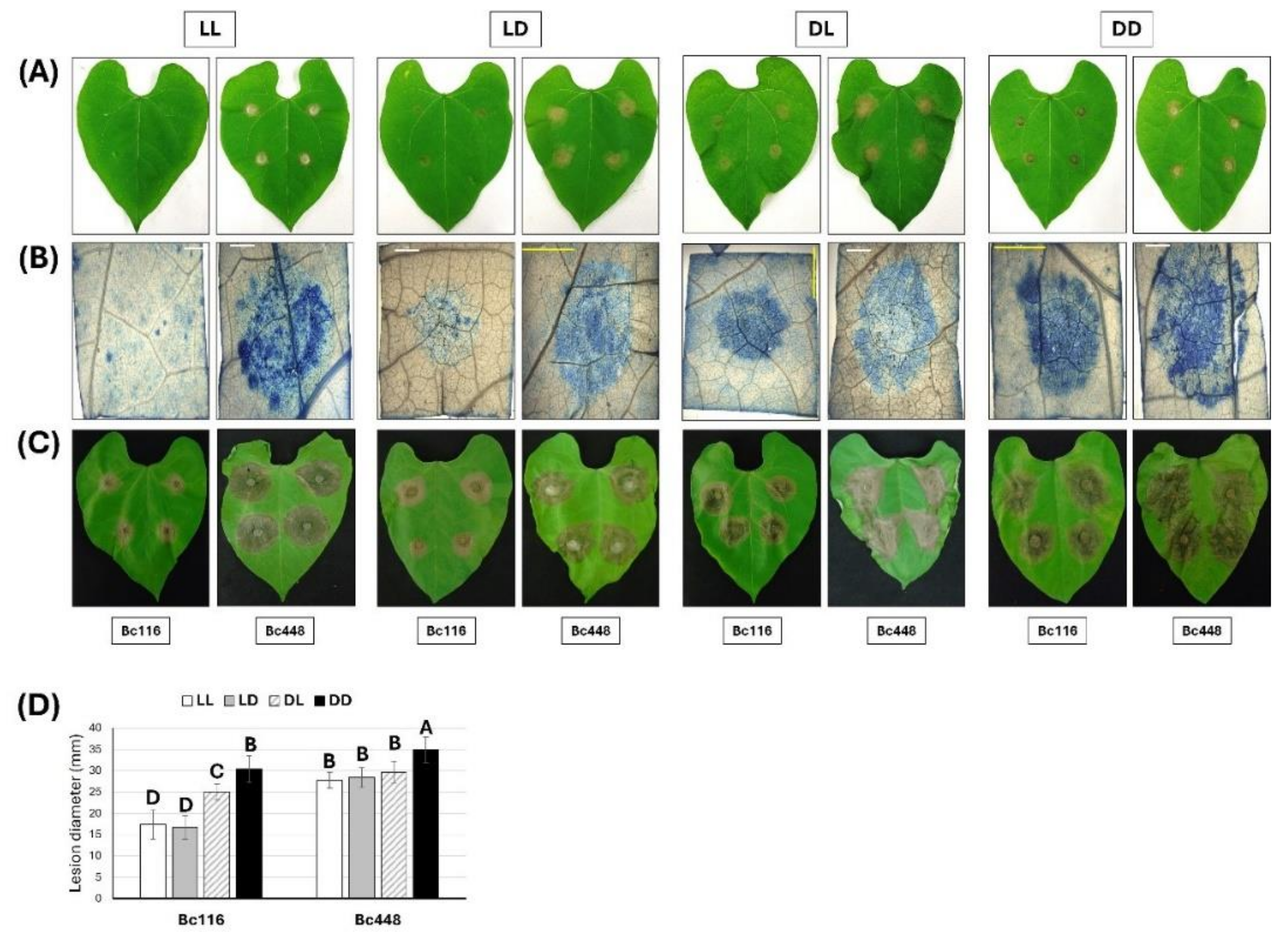

Evaluation of the effect of light on pathogenicity of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on Vitis leaves. (A) Vitis leaves were inoculated with mycelium plugs of both strains and incubated under the indicated light regimes during 96 h. The 16/8 h photoperiod regime was initiated either in the light phase (LD) or in the darkness phase (DL). (B) Quantification of aggressiveness of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on Vitis leaves under different light conditions (permanent light -LL-, white bars; 16/8 h light/darkness photoperiod -LD-, grey bars; 8/16 h darkness/light photoperiod -DL-, striped bars; permanent darkness -DD-, black bars) estimated as the medium lesion diameter. Bars show the media ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between all the conditions assayed that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Evaluation of the effect of light on pathogenicity of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on Vitis leaves. (A) Vitis leaves were inoculated with mycelium plugs of both strains and incubated under the indicated light regimes during 96 h. The 16/8 h photoperiod regime was initiated either in the light phase (LD) or in the darkness phase (DL). (B) Quantification of aggressiveness of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on Vitis leaves under different light conditions (permanent light -LL-, white bars; 16/8 h light/darkness photoperiod -LD-, grey bars; 8/16 h darkness/light photoperiod -DL-, striped bars; permanent darkness -DD-, black bars) estimated as the medium lesion diameter. Bars show the media ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between all the conditions assayed that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the effect of light on pathogenicity of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on bean leaves. Bean leaves were inoculated with mycelium plugs of both strains and incubated under the indicated light regimes. (A) Aspect of the inoculated leaves 24 hpi. (B) Lesions generated by Bc116 and Bc448 24 hpi. At the indicated time point the mycelium plugs were removed, and the plant tissues were stained with lactophenol blue. Images were taken using a Leica DFC495 camera adapted to a Leica 205FA stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany). White scale bars, 2 mm; yellow scale bars, 5 mm. (C) Aspect of the inoculated leaves 72 hpi. (D) Quantification of aggressiveness of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on bean leaves under different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 h LD, grey bars; 8/16 h DL, striped bars; DD, black bars) estimated as the medium lesion diameter 72 hpi. Bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between all the conditions assayed that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the effect of light on pathogenicity of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on bean leaves. Bean leaves were inoculated with mycelium plugs of both strains and incubated under the indicated light regimes. (A) Aspect of the inoculated leaves 24 hpi. (B) Lesions generated by Bc116 and Bc448 24 hpi. At the indicated time point the mycelium plugs were removed, and the plant tissues were stained with lactophenol blue. Images were taken using a Leica DFC495 camera adapted to a Leica 205FA stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany). White scale bars, 2 mm; yellow scale bars, 5 mm. (C) Aspect of the inoculated leaves 72 hpi. (D) Quantification of aggressiveness of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 on bean leaves under different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 h LD, grey bars; 8/16 h DL, striped bars; DD, black bars) estimated as the medium lesion diameter 72 hpi. Bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between all the conditions assayed that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Light affects the ability of isolate Bc116 to penetrate epidermal onion cells. Onion epidermal strips were inoculated with spores (panels A, C, E and G) or with mycelium plugs (panels B, D, F and H) of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 and incubated under LL or DD conditions. Penetration was evaluated visually at 12 hpi for the inoculations performed with spore suspensions and at 24 hpi for the inoculations performed with mycelium plugs. Samples were stained with lactophenol blue. Yellow arrowheads indicate hyphae penetrating host cells. Scale bars, 50 µm in panels A, C, E and G; 100 µm in panels B, D, F and H.

Figure 3.

Light affects the ability of isolate Bc116 to penetrate epidermal onion cells. Onion epidermal strips were inoculated with spores (panels A, C, E and G) or with mycelium plugs (panels B, D, F and H) of isolates Bc116 and Bc448 and incubated under LL or DD conditions. Penetration was evaluated visually at 12 hpi for the inoculations performed with spore suspensions and at 24 hpi for the inoculations performed with mycelium plugs. Samples were stained with lactophenol blue. Yellow arrowheads indicate hyphae penetrating host cells. Scale bars, 50 µm in panels A, C, E and G; 100 µm in panels B, D, F and H.

Figure 4.

Effect of light on physiology of isolates Bc116 and Bc448. (A) Germination of conidia on liquid medium in static culture. 60 µL of a 5x105 sp/mL conidial suspension were prepared and placed in the center of empty Petri dishes. The plates were incubated at 22°C under different light conditions (LL, white bars; DD, black bars). The number of conidia in each stage (stages 0, 1, 2) was determined 6 hpi. The bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between conditions assayed for each fungal isolate that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Scale bars in images of spores, 10 µm. (B) Effect of light on the conidiation rate of isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. Mycelium plugs of each fungal isolate were placed in the center of MEA plates and incubated for three weeks at 22°C under different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 LD, grey bars; DD, black bars). Afterwards, conidia were harvested, and the concentration was estimated using a Thoma cell counting chamber. The bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between conditions assayed for each fungal isolate that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). (C) Saprophytic growth on synthetic media of isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. 10 µL of a 5x105 sp/mL conidial suspension of each fungal isolate were placed in the center of MEA plates and the diameter of the colony was estimated 5 days post-inoculation (dpi). Plates were incubated at 22°C and different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 h LD, grey bars; DD, black bars). Bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between all the conditions assayed that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). (D) Production of sclerotia by isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. Mycelium plugs were placed in the center of MEA plates that were incubated at 2-4°C and DD for 4 weeks.

Figure 4.

Effect of light on physiology of isolates Bc116 and Bc448. (A) Germination of conidia on liquid medium in static culture. 60 µL of a 5x105 sp/mL conidial suspension were prepared and placed in the center of empty Petri dishes. The plates were incubated at 22°C under different light conditions (LL, white bars; DD, black bars). The number of conidia in each stage (stages 0, 1, 2) was determined 6 hpi. The bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between conditions assayed for each fungal isolate that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Scale bars in images of spores, 10 µm. (B) Effect of light on the conidiation rate of isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. Mycelium plugs of each fungal isolate were placed in the center of MEA plates and incubated for three weeks at 22°C under different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 LD, grey bars; DD, black bars). Afterwards, conidia were harvested, and the concentration was estimated using a Thoma cell counting chamber. The bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between conditions assayed for each fungal isolate that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). (C) Saprophytic growth on synthetic media of isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. 10 µL of a 5x105 sp/mL conidial suspension of each fungal isolate were placed in the center of MEA plates and the diameter of the colony was estimated 5 days post-inoculation (dpi). Plates were incubated at 22°C and different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 h LD, grey bars; DD, black bars). Bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between all the conditions assayed that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). (D) Production of sclerotia by isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. Mycelium plugs were placed in the center of MEA plates that were incubated at 2-4°C and DD for 4 weeks.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity to oxidative stress of isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. Mycelium plugs from the edge of actively growing colonies were placed in the center of MEA plates. The oxidative stress was provided by the addition of 7.5 mM H2O2 to the media. Plates were incubated at 22°C under different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 h LD, grey bars; DD, black bars) and the colony diameter was estimated 96 hpi. Bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between the conditions assayed for each fungal isolate that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Representative images of colony morphology and colony diameter for each strain and condition are shown.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity to oxidative stress of isolates Bc116, Bc448 and B05.10. Mycelium plugs from the edge of actively growing colonies were placed in the center of MEA plates. The oxidative stress was provided by the addition of 7.5 mM H2O2 to the media. Plates were incubated at 22°C under different light conditions (LL, white bars; 16/8 h LD, grey bars; DD, black bars) and the colony diameter was estimated 96 hpi. Bars show the media ± SD of three independent biological experiments. The letters over each bar represent significant differences between the conditions assayed for each fungal isolate that were tested using an ANOVA analysis followed by a Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Representative images of colony morphology and colony diameter for each strain and condition are shown.

Figure 6.

Mapping the genome region linked to the Bc116 phenotype by BSA in the cross Bc116 x Bc448. (A, B) The figure plots the SNP index of Bc448 specific variants or of Bc116 specific variants (Y-axis) across Chr13 (A) or Chr14 (B) coordinates (X-axis). The box in panel (B) delimitates a region in Chr14 where the SNP index reaches maximal values for Bc116 specific variants and minimal values for Bc448 specific variants. (C) Detailed analysis of the mapped region indicating the genes within this region annotated in the B05.10 genome. The blue graph over the linear representation of the mapped area represents sequencing reads coverage when Bc116 genome reads are aligned with the B05.10 genome. A region with no coverage is observed around the 5’-upstram region of gene bcltf1. The annealing positions of the oligonucleotides P1 (bcltf1-c2F) and P2 (bcltf1-c2R), used to amplify both the B05.10 and Bc116 alleles are indicated.

Figure 6.

Mapping the genome region linked to the Bc116 phenotype by BSA in the cross Bc116 x Bc448. (A, B) The figure plots the SNP index of Bc448 specific variants or of Bc116 specific variants (Y-axis) across Chr13 (A) or Chr14 (B) coordinates (X-axis). The box in panel (B) delimitates a region in Chr14 where the SNP index reaches maximal values for Bc116 specific variants and minimal values for Bc448 specific variants. (C) Detailed analysis of the mapped region indicating the genes within this region annotated in the B05.10 genome. The blue graph over the linear representation of the mapped area represents sequencing reads coverage when Bc116 genome reads are aligned with the B05.10 genome. A region with no coverage is observed around the 5’-upstram region of gene bcltf1. The annealing positions of the oligonucleotides P1 (bcltf1-c2F) and P2 (bcltf1-c2R), used to amplify both the B05.10 and Bc116 alleles are indicated.

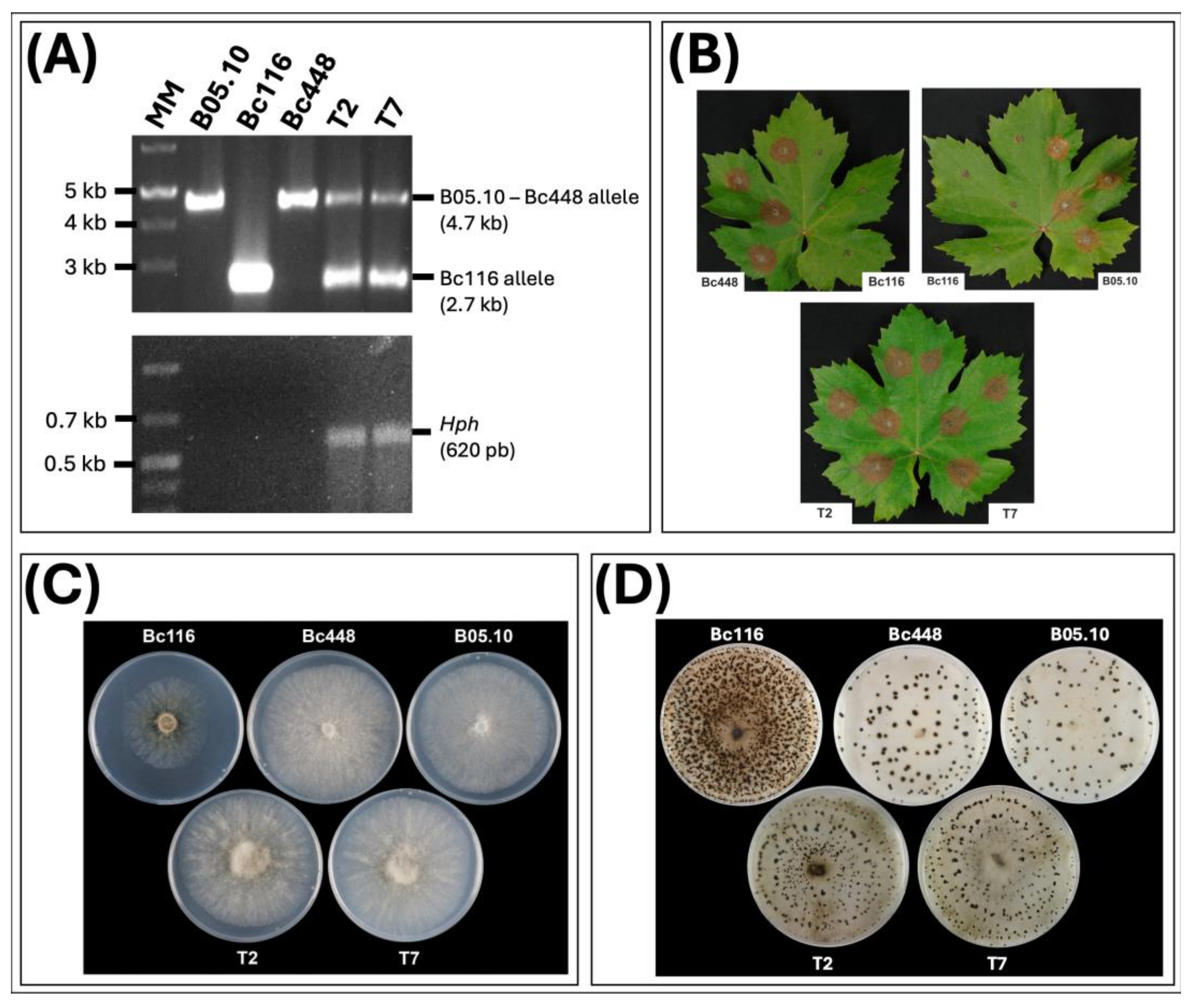

Figure 7.

Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Bc116-bcltf1 complemented transformants. (A) PCR based analysis of transformants obtained with the B05.10 bcltf1 allele. Reactions were carried out with genomic DNA of B05.10, Bc116, Bc448 or transformants T2 and T7 as template. The sizes of the diagnostic bands are indicated. MM: GeneRuler 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder (ThermoFisher Scientific). (B) Inoculations on Vitis leaves of Bc116, B05.10, Bc448 isolates and transformants T2 and T7. Leaves were inoculated with mycelium plugs of each isolate and incubated at 22°C under a 16/8 h photoperiod (LD). Images were taken 96 hpi. (C) Phenotype of the fungal isolates during growth in MEA plates (4 days at 22°C under LD conditions). (D) Pattern of production of sclerotia of the fungal isolates on MEA plates. Plates were incubated at 2-4°C under DD for 4 weeks.

Figure 7.

Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Bc116-bcltf1 complemented transformants. (A) PCR based analysis of transformants obtained with the B05.10 bcltf1 allele. Reactions were carried out with genomic DNA of B05.10, Bc116, Bc448 or transformants T2 and T7 as template. The sizes of the diagnostic bands are indicated. MM: GeneRuler 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder (ThermoFisher Scientific). (B) Inoculations on Vitis leaves of Bc116, B05.10, Bc448 isolates and transformants T2 and T7. Leaves were inoculated with mycelium plugs of each isolate and incubated at 22°C under a 16/8 h photoperiod (LD). Images were taken 96 hpi. (C) Phenotype of the fungal isolates during growth in MEA plates (4 days at 22°C under LD conditions). (D) Pattern of production of sclerotia of the fungal isolates on MEA plates. Plates were incubated at 2-4°C under DD for 4 weeks.

Table 1.

Total number of SNPs identified in the genomes of isolates Bc448 and Bc116 in comparison with the B05.10 genome. The number of SNPs exclusive of each isolate is presented.

Table 1.

Total number of SNPs identified in the genomes of isolates Bc448 and Bc116 in comparison with the B05.10 genome. The number of SNPs exclusive of each isolate is presented.

| |

B05.10 Genome |

Bc448 SNPs |

Bc116 SNPs |

| |

Chr size (kb) |

Total number |

Exclusive |

Total number |

Exclusive |

| Chr 1 |

4109 |

23260 |

9129 |

26619 |

12128 |

| Chr 2 |

3341 |

17103 |

5335 |

19466 |

7698 |

| Chr 3 |

3227 |

13364 |

4379 |

15161 |

6176 |

| Chr 4 |

2472 |

16024 |

7069 |

18731 |

9776 |

| Chr 5 |

2959 |

11864 |

4260 |

12701 |

5097 |

| Chr 6 |

2726 |

17544 |

5529 |

19339 |

7324 |

| Chr 7 |

2652 |

17831 |

5715 |

18805 |

6689 |

| Chr 8 |

2617 |

14368 |

5583 |

15433 |

6649 |

| Chr 9 |

2548 |

16793 |

5866 |

18543 |

7616 |

| Chr 10 |

2419 |

13662 |

4484 |

15798 |

6620 |

| Chr 11 |

2360 |

12485 |

3928 |

15300 |

6743 |

| Chr 12 |

2353 |

13996 |

5298 |

14802 |

6104 |

| Chr 13 |

2258 |

10921 |

3949 |

13106 |

6134 |

| Chr 14 |

2138 |

14089 |

5718 |

15952 |

7581 |

| Chr 15 |

2028 |

11469 |

3246 |

14335 |

6112 |

| Chr 16 |

1970 |

10795 |

3556 |

13634 |

6395 |

| Chr 17 |

247 |

107 |

74 |

54 |

51 |

| SUM |

42424 |

235675 |

83118 |

267779 |

114893 |