Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

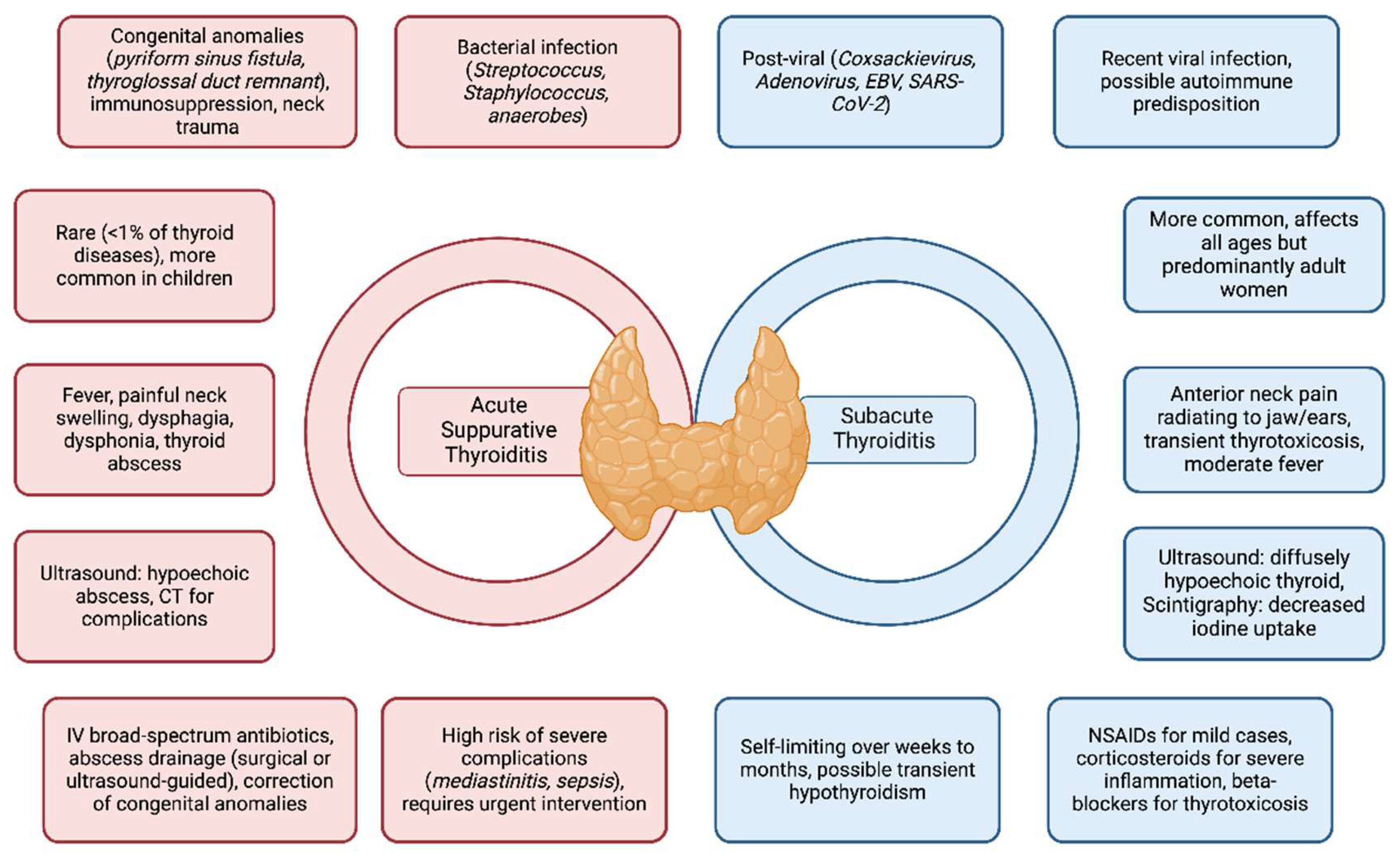

Background: Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis (AST) and Subacute Thyroiditis (SAT) are two distinct inflammatory conditions of the thyroid gland with different clinical presentation, treatment and that recognize different causes. AST is a rare but serious bacterial infection, often associated with congenital anomalies in children, whereas SAT is a self-limiting, post-viral condition that causes temporary thyroid dysfunction. Methods: A comprehensive literature review was conducted using PubMed and UpToDate, including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, case series, and case reports. Studies focusing on epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment were selected, with special attention to pediatric cases. Results: AST accounts for fewer than 1% of thyroid diseases and is more common in children, with pyriform sinus fistulas being present in 21% of cases. It presents with fever, painful neck swelling, and complications such as abscess formation and airway obstruction. Early recognition and prompt management with broad-spectrum antibiotics, ultrasound-guided aspiration, or surgical drainage are crucial. In contrast, SAT can occur at any age but is most common in adult women and follows typically a viral infection. It presents with anterior neck pain and transient thyrotoxicosis and is generally managed with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids in severe cases. Accurate differential diagnosis is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions. Conclusions: Although rare, both AST and SAT require timely diagnosis and tailored treatment strategies to avoid complications. Advances in imaging and early detection of congenital anomalies have improved AST outcomes, while SAT remains a self-limiting condition that primarily requires symptom management. Further research is needed to better understand risk factors, pathogenesis, and optimal treatment approaches, particularly in pediatric populations and resource-limited settings.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Epidemiology and predisposing conditions

4. Etiology

5. Clinical presentation

6. Diagnosis

7. Thyroid function and management

8. Antibiotic therapy for acute suppurative thyroiditis (AST), and treatment of subacute thyroiditis

9. Differential diagnosis

10. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AST | Acute Suppurative Thyroidits |

| SAT | Subacute Thyroiditis |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| IV | Intravenous |

| NSAIDs | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistan Staphylococcus aureus |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| EBV | Epstein-Barr Virus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency virus |

References

- Bilbao NA, Kaulfers A-MD, Bhowmick SK. Subacute Thyroiditis in a Child. AACE Clin Case Rep 2019, 5, e184–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongphyat O, Mahachoklertwattana P, Molagool S, Poomthavorn P. Acute suppurative thyroiditis in young children. Acute suppurative thyroiditis in young children. J Paediatr Child Health 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine N, Learoyd D, Farrell S, Wong R. Suppurative thyroiditis: Systematic review and clinical guidance. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2021, 95, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo SM, Allen DB. Thyroiditis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1989, 28, 171–174. [CrossRef]

- Manzano D, González L, Narváez L. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis in a Pediatric Patient: A Case Report. SAS Journal of Surgery 2023, 9, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes JE, Burman KD, Cohen J, Franklyn J, McHenry CR, Shoham S, Kloos RT. Acute Bacterial Suppurative Thyroiditis: A Clinical Review and Expert Opinion. Thyroid 2010, 20, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falhammar H, Wallin G, Calissendorff J. Acute suppurative thyroiditis with thyroid abscess in adults: clinical presentation, treatment and outcomes. BMC Endocr Disord 2019, 19, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoucar K, Giger R, Pope HG, Jaecklin T, Dulguerov P. Management of congenital fourth branchial arch anomalies: a review and analysis of published cases. J Pediatr Surg 2009, 44, 1432–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai Prasad TR, Chong CL, Mani A, Chui CH, Tan CEL, Tee WSN, Jacobsen AS. Acute suppurative thyroiditis in children secondary to pyriform sinus fistula. Pediatr Surg Int 2007, 23, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi H, Lee Y-J, Chiu N-C, Huang F-Y, Huang C-Y, Lee K-S, Shih S-L, Shih B-F. Acute suppurative thyroiditis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002, 21, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She X, Zhou Y-N, Guo J, Yi C. Clinical Analysis of Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis in 18 Children. Infect Drug Resist 2022, 15, 4471–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, I. Microbiology and management of acute suppurative thyroiditis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2003, 67, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng Q, Lv Z, Xiao X, Zheng S, Huang Y, Huang X, Li H, Wu Y, Dong K, Liu J. Diagnosis and management of pyriform sinus fistula: Experience in 48 cases. J Pediatr Surg 2014, 49, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panamonta O, Panombualert S, Panamonta M, Apinives C. Acute suppurative thyroiditis with thyrotoxicosis. J Med Assoc Thai 2009, 92, 1370–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzo N, Patera B, Fazzino G, Gallo D, Lai A, Piantanida E, Ippolito S, Tanda M. The Old and the New in Subacute Thyroiditis: An Integrative Review. Endocrines 2022, 3, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu C, Jiang R, Liu JY. Emerging trends and hot spots in subacute thyroiditis research from 2001 to 2022: A bibliometric analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). [CrossRef]

- Gómez S, Mora C, López de Suso D, Escalada Pellitero S, Aragón P, Parrón M, Bartolomé-Benito M, Sanz-Santaeufemia FJ, Méndez-Echevarría A. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis in Children: Clinical Decision-Making. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2023, 42, e384–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs A, Gros D-AC, Gradon JD. Thyroid Abscess Due to Acinetobacter calcoaceticus: Case Report and Review of the Causes of and Current Management Strategies for Thyroid Abscesses. South Med J 2003, 96, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles D, Boguniewicz J, Shakeel O, Margolin J, Chelius D, Gupta M, Paul D, King KY, McNeil JC. Candida tropicalis Thyroiditis Presenting With Thyroid Storm in a Pediatric Patient With Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2019, 38, 1051–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung Bck, Loke Tki, Fann Wc, Chan Jcs. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis Due to Foreign Body–Induced Retropharyngeal Abscess Presented as Thyrotoxicosis. Clin Nucl Med 2000, 25, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien K-J, Chen T-C, Hsieh M-C, Hsu S-C, Hsiao J-Y, Shin S-J, Hsin S-C. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis with Deep Neck Infection: A Case Report. Thyroid 2007, 17, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedla N, Pirela D, Manzano A, Tuda C, Lo Presti S. Thyroid Abscess: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. [CrossRef]

- Jeng L-BB, Lin J-D, Chen M-F. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis: A Ten-year Review in a Taiwanese Hospital. Scand J Infect Dis 1994, 26, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin SA, Smith SL, Meek SE. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis Caused by Pasteurella multocida and Associated with Thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 2006, 16, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy SM, Becktell KD, Muller WJ, Schneiderman J. Aspergillus thyroiditis: first antemortem case diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration culture in a pediatric stem cell transplant patient. Transplant Infectious Disease 2015, 17, 868–871. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Rueda JE, Monsalve Naranjo AD, Giraldo Benítez C, Ramírez Quintero JD. Suppurative Thyroiditis: Coinfection by Nocardia spp. and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an Immunocompromised Patient. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- N’gattia K-V, Kacouchia N-B, Vroh B-T-S, Kouassi-Ndjeundo J. Suppurative thyroiditis and HIV infection. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2015, 132, 371–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engkakul P, Mahachoklertwattana P, Poomthavorn P. de Quervain thyroiditis in a young boy following hand–foot–mouth disease. Eur J Pediatr 2011, 170, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Aniello F, Amodeo ME, Grossi A, Ubertini G. Thyroiditis and COVID-19: focus on pediatric age. A narrative review. J Endocrinol Invest 2024, 47, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancatella A, Ricci D, Viola N, Sgrò D, Santini F, Latrofa F. Subacute Thyroiditis After Sars-COV-2 Infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, 2367–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara E, Miyauchi A, Matsuzuka F, Sasaki I, Ohye H, Kubota S, Fukata S, Amino N, Kuma K. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis After Fine-Needle Aspiration Causing Thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 2005, 15, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoffarreh H, Alkaabi N, Alkhurayji A. Partially Treated Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis in a Healthy Child Caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. Partially Treated Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis in a Healthy Child Caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. Cureus 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fassih M, Moujahid E, Abada R, Rouadi S, Mahtar M, Roubal M, Essadi M, El Kadiri MF. Abcès thyroïdien à Escherichia coli: à propos d’un cas et revue de la littérature [Escherichia coli thyroid abscess: report of a case and literature review]. Pan Afr Med J.

- Adeyemo A, Adeosun A, Adedapo K. Unusual cause of thyroid abscess. . Afr Health Sci 2010, 10, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Vengathajalam S, Retinasekharan S, Mat Lazim N, Abdullah B. Salmonella Thyroid Abscess Treated by Serial Aspiration: Case Report and Literature Review. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery 2019, 71, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavreas NP, Amanatidou CD, Hatzimanolis EG, Legakis I, Naoum G, Lakka-Papadodima E, Georgoulias G, Morfou P, Tsiodras S. Thyroid Abscess Due to a Mixed Anaerobic Infection with Fusobacterium mortiferum. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 6202–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun J, Chang H, Chen K, Lin K, Lin J, Hsueh C. Anaerobic thyroid abscess from a thyroid cyst after fine-needle aspiration. Head Neck 2002, 24, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, I. Suppurative thyroiditis in children and adolescents. UpToDate 2024.

- Rafiei N, Masoudi M, Jadidi H, Ghaedi A, Jahani N, Ebrahimi S, Gharei F, Amirhoushangi H, Bayat M, Ansari A, Hamedanchi NF, Hosseini P, Elmi S, Garousi S, Mottahedi M, Ghasemi M, Alizadeh A, Deravi N. The association of subacute thyroiditis with viral diseases: a comprehensive review of literature. Przegl Epidemiol 2023, 77, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank TS, LiVolsi VA, Connor AM. Cytomegalovirus infection of the thyroid in immunocompromised adults. Yale J Biol Med 1987, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Giadrosich R V, Hernández C MI, Izquierdo Q C, Zamora K B. Tiroiditis aguda supurada en un paciente pediátrico: Report of a pediatric case. Rev Med Chil. [CrossRef]

- Pereira O, Prasad DS, Bal AM, McAteer D, Abraham P. Fatal Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis Secondary to Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis Developing in an Apparently Healthy Woman. Thyroid 2010, 20, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOUGH D, RAMADAN H, ARONOFF S. Acute suppurative thyroiditis in children. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 1996, 114, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, PR. Serum triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyrotropin during hyperthyroid, hypothyroid, and recovery phases of subacute nonsuppurative thyroiditis. Metabolism 1974, 23, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa E, Katsushima Y, Fujiwara I, Iinuma K. Subacute Thyroiditis in Children: Patient Report and Review of the Literature. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi A, Tomoda C, Uruno T, Takamura Y, Ito Y, Miya A, Kobayashi K, Matsuzuka F, Fukata S, Amino N, Kuma K. Computed Tomography Scan Under A Trumpet Maneuver to Demonstrate Piriform Sinus Fistulae in Patients with Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis. Thyroid 2005, 15, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuoka H, Miyauchi A, Tomoda C, Inoue H, Takamura Y, Ito Y, Kobayashi K, Miya A. Imaging Studies in Sixty Patients with Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis. Thyroid 2011, 21, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtois MF, Colom NF, Rodas MA, Magnanelli V, Palmieri F, Mirón L, Muracciole B. Tiroiditis aguda supurada en una paciente con fístula del seno piriforme: presentación de un caso. Arch Argent Pediatr. [CrossRef]

- McHan L, Gupta J. Thyrotoxicosis Due to Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis in a Pediatric Patient: A Case Report. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. [CrossRef]

- Sicilia V, Mezitis S. A case of acute suppurative thyroiditis complicated by thyrotoxicosis. J Endocrinol Invest 2006, 29, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadney M, Senguttuvan R, Patel PG. Case 3: Anterior Neck Swelling, Fever, and Hypertension in a 3-Year-Old Boy. Pediatr Rev 2015, 36, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuki T, Onuma R, Tonsho K, Saito D, Sakai H, Kamimura M, Watanabe Y, Kurihara N, Ishida E, Kumaki S. Hoarseness as the first symptom in a patient with acute suppurative thyroiditis secondary to a pyriform sinus fistula: a case report. BMC Pediatr 2023, 23, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh A, Saha S, Bhattacharya B, Chattopadhay S. Primary tuberculosis of thyroid gland: a rare case report. Am J Otolaryngol 2007, 28, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty M, Coker R, Claydon E. Case report: Disseminated Pneumocystis carinii infection in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome causing thyroid gland calcification and hypothyroidism. Clin Radiol 1992, 45, 209–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada H, Fujita K, Tokuriki T, Ishida R. Nine cases of piriform sinus fistula with acute suppurative thyroiditis. Auris Nasus Larynx 2002, 29, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee S hee, Kim EY. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis Caused by Methicillin - Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Healthy Children. Journal of Korean Society of Pediatric Endocrinology 2011, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segni M, Turriziani I, di Nardo R, Pucarelli I, Serafinelli C. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis Treated Avoiding Invasive Procedures in a Child. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 2980–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saklamaz, A. Is There a Drug Effect on the Development of Permanent Hypothyroidism in Subacute Thyroiditis? Acta Endocrinologica (Bucharest) 2017, 13, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolmo D, Madana J, Kalaiarasi R, Gopalakrishnan S, Kiruba Shankar M, Krishnapriya S. Retrospective case review of pyriform sinus fistulae of third branchial arch origin commonly presenting as acute suppurative thyroiditis in children. J Laryngol Otol 2012, 126, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan L, Feng X, Zhang R, Tan X, Xiang X, Shen R, Zheng H. Short-Term Versus 6-Week Prednisone In The Treatment Of Subacute Thyroiditis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Endocrine Practice 2020, 26, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttner A, Bielicki J, Clements MN, Frimodt-Møller N, Muller AE, Paccaud J-P, Mouton JW. Oral amoxicillin and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid: properties, indications and usage. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2020, 26, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez D, Melloni C, Yogev R, Poindexter BB, Mendley SR, Delmore P, Sullivan JE, Autmizguine J, Lewandowski A, Harper B, Watt KM, Lewis KC, Capparelli E V, Benjamin DK, Cohen-Wolkowiez M. Use of Opportunistic Clinical Data and a Population Pharmacokinetic Model to Support Dosing of Clindamycin for Premature Infants to Adolescents. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014, 96, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng L, Choonara I, Zhang L, Xue S, Chen Z, He M. Safety of ceftriaxone in paediatrics: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloza DL, Semar RW, Bernfeld GE. Intravenous Use of Cephradine and Cefazolin Against Serious Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1979, 15, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, Levine DP, Bradley JS, Liu C, Mueller BA, Pai MP, Wong-Beringer A, Rotschafer JC, Rodvold KA, Maples HD, Lomaestro BM. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: A revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2020, 77, 835–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramar YV, Mandal TK, Bostanian LA, Le G, Morris TC, Graves RA. Physicochemical and Microbiological Stability of Compounded Metronidazole Suspensions in PCCA SuspendIt. . Int J Pharm Compd 2021, 25, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Volta C, Carano N, Street ME, Bernasconi S. Atypical Subacute Thyroiditis Caused by Epstein-Barr Virus Infection in a Three-Year-Old Girl. Thyroid 2005, 15, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanker V, Mohamed A, Jadhav C. Acute Suppurative Thyroiditis (AST) With Thyroid Abscess: A Rare and Potentially Fatal Neck Infection. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Cathcart, RA. Inflammatory swellings of the head and neck. Surgery (Oxford) 2012, 30, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith SL, Pereira KD. Suppurative Thyroiditis in Children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008, 24, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca IFA da, Avvad CK, Sanchez EG, Henriques JLM, Leão LMCSM. Tireoidite supurativa aguda com múltiplas complicações. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia 2012, 56, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai C, Kakihara T, Watanabe A, Ikarashi Y, Hotta H, Tanaka A, Uchiyama M. Acute suppurative thyroiditis as a rare complication of aggressive chemotherapy in children with acute myelogeneous leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2002, 19, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Infectious Agents | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Staphylococcus aureus | The most common bacterial cause; it is often associated with abscess formation. | [31] |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Can cause severe cases, especially in children. | [21,32] | |

|

Streptococcus pneumoniae Escherichia coli |

Less common but significant in specific populations. Associated with immunocompromised states or anatomical abnormalities. |

[32,33,34] | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Reported in nosocomial infections and immunocompromised patients. | [35] | |

| Salmonella spp. | Rare causes, linked to underlying systemic infections. | ||

| Anaerobic Bacteria | Fusobacterium spp. | Reported in cases associated with dental or oropharyngeal infections. | [36] |

| Bacteroides spp. | They can cause mixed infections with aerobic bacteria. | [37] | |

| Fungal | Candida albicans | Occurs in immunocompromised individuals, such as those undergoing chemotherapy. | [19] |

| Parasitic | Entamoeba histolytica | Extremely rare; reported in endemic areas. | [38] |

| Polymicrobial Infections | Combination of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria | Frequently found in cases with anatomical abnormalities such as pyriform sinus fistula. | [24] |

| Viral | Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) | Rare, usually seen in immunocompromised patients. | [39,40] |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | Similar to EBV, in cases with compromised immune systems. | [6] |

| Antibiotic | Dosage Range (Pediatric) | Administration frequency | Coverage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 20–40 mg/kg/day of amoxicillin component | Subdivided; every 8 hours | Broad-spectrum (Gram-positive, anaerobes) | [61] |

| Clindamycin | 20–40 mg/kg/day | Subdivided; every 6–8 hours | Gram-positive, anaerobes | [62] |

| Ceftriaxone | 50–75 mg/kg/day | Once daily | Broad-spectrum (Gram-negative, Gram-positive) | [63] |

| Cefazolin | 50–100 mg/kg/day | Subivided; every 8 hours | Gram-positive | [64] |

| Vancomycin | 40 mg/kg/day | Subdivided every 6-8 hours | MRSA, Gram-positive | [65] |

| Metronidazole | 15–30 mg/kg/day | Subdivided; every 8 hours | Anaerobes | [66] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).