Submitted:

12 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

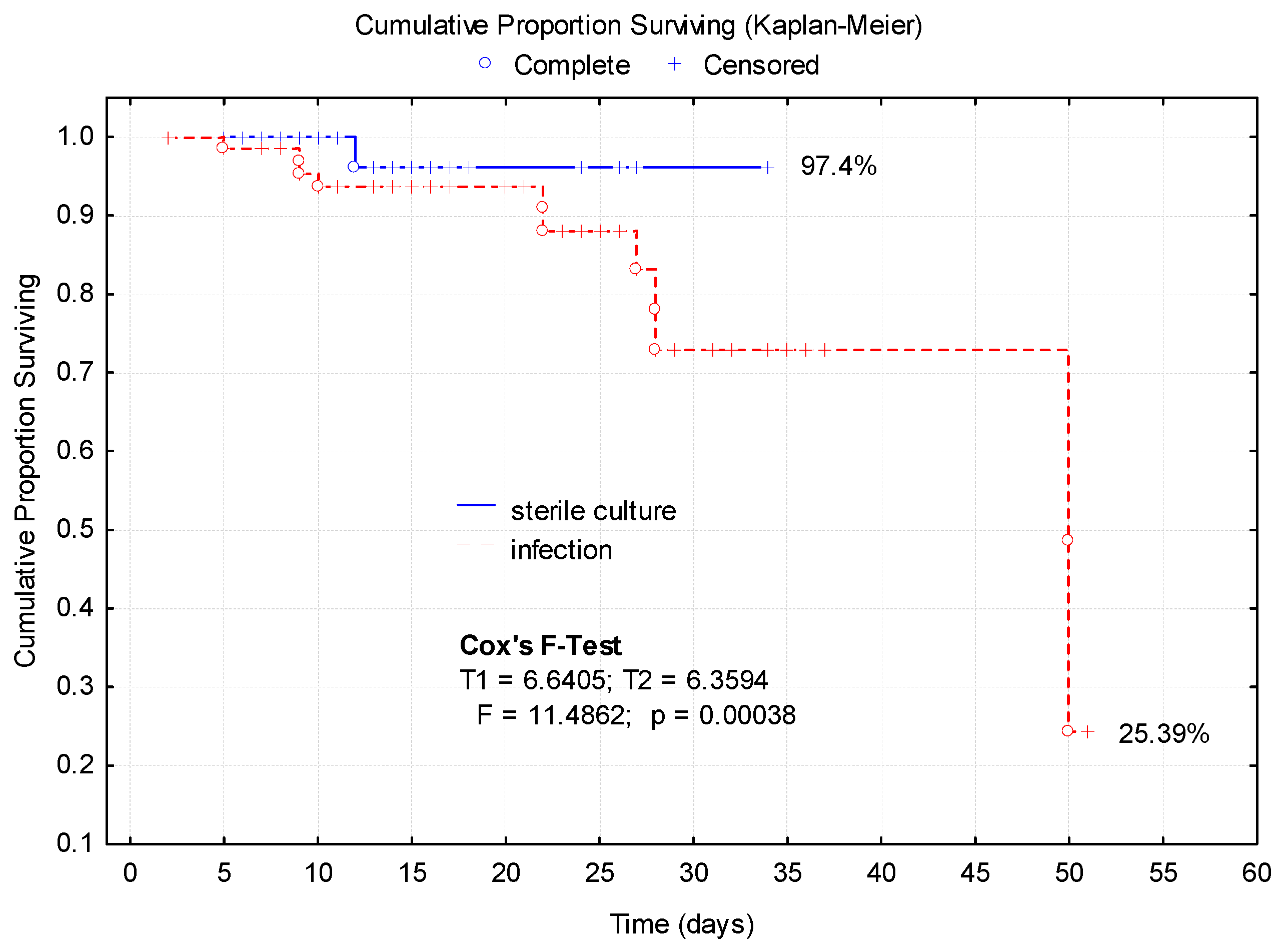

Background and Objectives: Deep neck infections (DNI) are severe diagnoses that can cause serious complications. However, are not available enough data to predict the evolution of this pathology. This study aimed to review the microbiology of DNI and to identify the factors that influence prolonged hospitalization. It was designed so that based on the results obtained, the evolution of patients with this pathology could be evaluated. Materials and Methods: In retrospective cohort observational analytical study a 7-years, we analyzed 138 patients with DNI who were diagnosed and received surgical treatment. Results: Reduced lymphocyte percentages and increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios (NLR) were significantly associated with complications (p < 0.001 and p = 0.0041, respectively). Laryngo-tracheal infections were significantly associated with complications (25.53%) (p = 0.0004). Diabetes mellitus and immunocompromised status, were strongly associated with complications (p < 0.001 and p = 0.0056, respectively), establishing these conditions as significant risk factors. Patients with complications experienced substantially longer hospitalizations, with a mean duration of 24.9 days compared to 8.32 days in patients without complications (p < 0.001). Complications were observed in 47 patients (34.06%). The most common complications were airway obstruction, which occurred in 26 patients (18.84%), and mediastinitis, which was noted in 31 patients (22.46%). Patients requiring tracheotomy due to airway obstruction had 6.51 times higher odds of long-term hospitalization compared to those without airway obstruction (OR = 6.51; p < 0.001). Mediastinitis was associated with a 4.81-fold increase in the odds of prolonged hospitalization (OR = 4.81; p < 0.001). Monomicrobial infections were observed in 35.5% of cases, with no significant difference between short-term (< 2 weeks, 37.33%) and long-term (≥ 2 weeks, 33.33%) hospitalization groups (p = 0.8472). Conversely, polymicrobial infections were significantly associated with prolonged hospitalization, occurring in 20.63% of long-term cases compared to 6.66% of short-term cases (p < 0.001). The most common aerobic bacteria were observed Staphylococcus aureus (14.28%) Streptococcus constellatus (12.69%) and Streptococcus viridans (7.93%) during long-term hospitalizations. The comparative analysis of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to the presence of infection revealed a significantly lower survival in cases with a positive culture. Conclusions: Deep neck infection is a complex pathology, whose therapeutic management remains a challenge in order to reduce the length of hospitalization and mortality.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

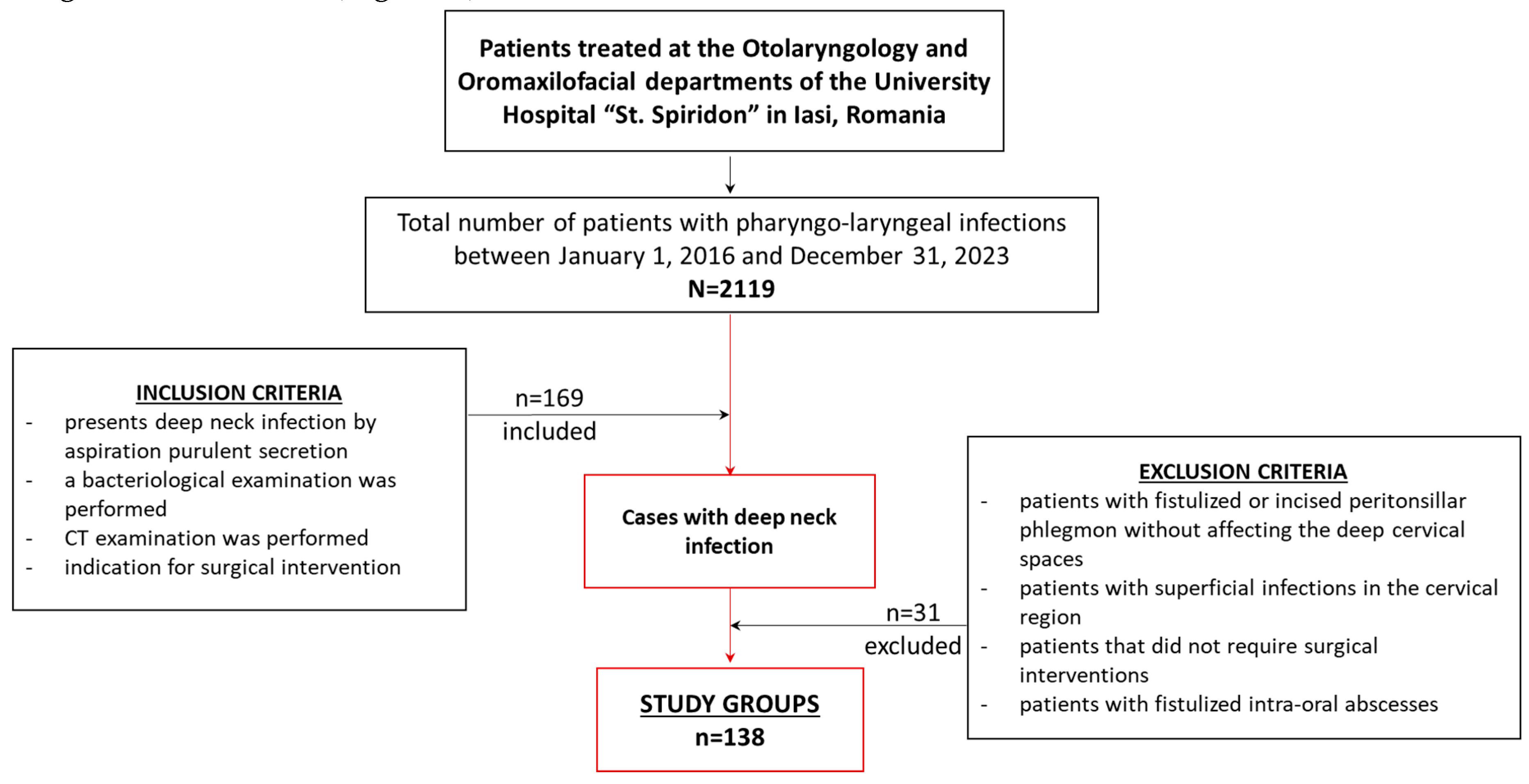

2.1. Study Group. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

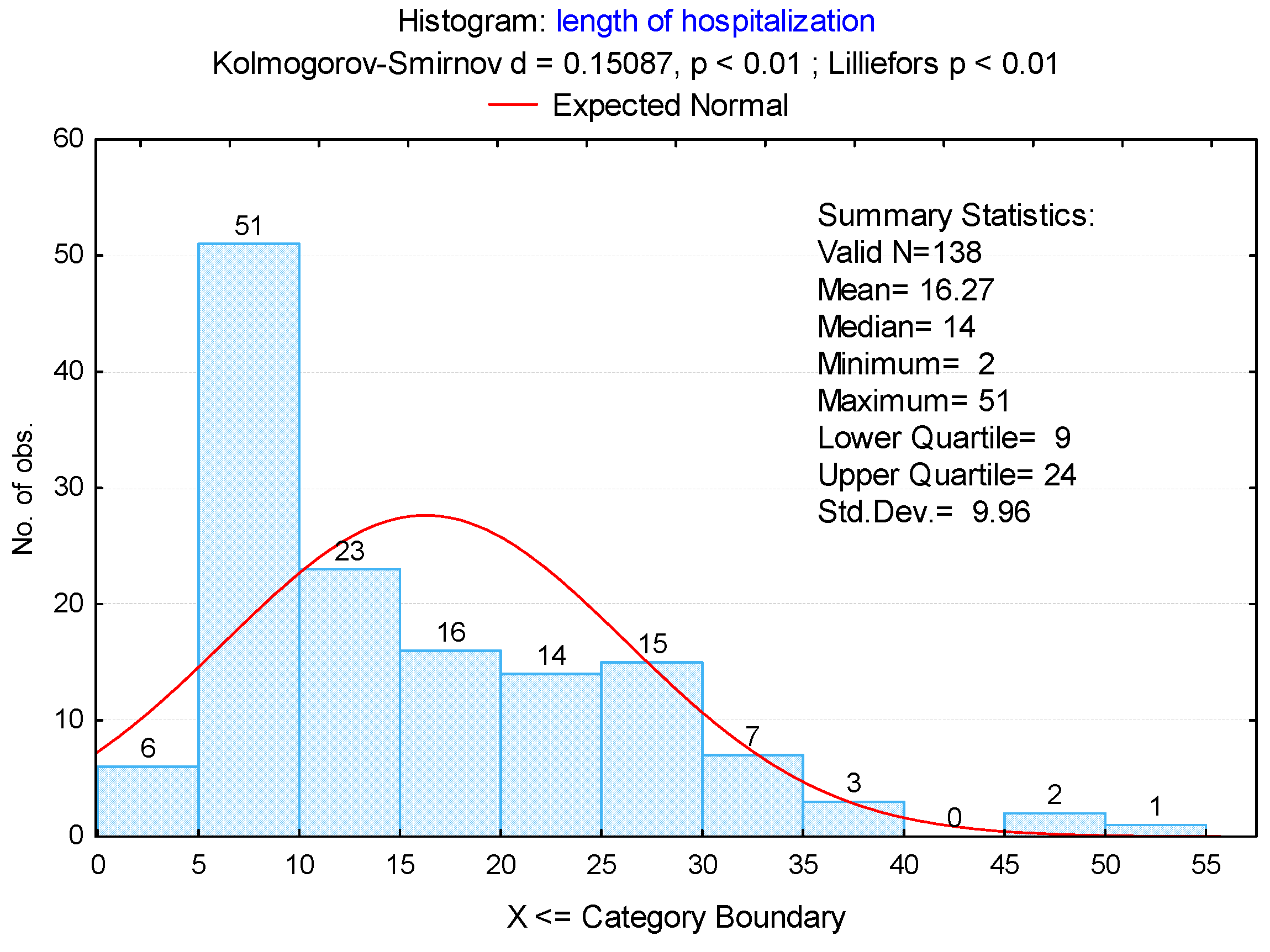

3.2. Duration of Hospitalization

3.3. Complications and Their Association with the Duration of Hospitalization

3.4. Bacterial Culture Positive Associated with Long-Term Hospitalization

3.5. Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bal, K. K., Unal, M., Delialioglu, N., Oztornaci, R. O., Ismi, O., Vayisoglu, Y. (2022). Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in deep neck infections: an analysis of 74 consecutive patients. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology, 88(4), 511–522. [CrossRef]

- Supreet Ratnakar Prabhu and Enosh Steward Nirmalkumar. (2019). Acute Fascial Space Infections of the Neck: 1034 cases in 17 years follow up. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 9(1): 118–123). [CrossRef]

- Staffieri, C., Fasanaro, E., Favaretto, N., La Torre, F. B., Sanguin, S., Giacomelli, L., Marino, F., Ottaviano, G., Staffieri, A., Marioni, G. (2014). Multivariate approach to investigating prognostic factors in deep neck infections. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 271(7), 2061–2067.

- Ord R, Coletti D. Cervico-facial necrotizing fasciitis. Oral Dis. 2009 Mar;15(2):133-41.

- Yang, T. H., Xirasagar, S., Cheng, Y. F., Wu, C. S., Kao, Y. W., Lin, H. C. (2021). A Nationwide Population-Based Study on the Incidence of Parapharyngeal and Retropharyngeal Abscess-A 10-Year Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(3), 1049. [CrossRef]

- Ungkanont K, Yellon RF, Weissman JL, Casselbrant ML, González-Valdepeña H, Bluestone CD. Head and neck space infections in infants and children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995 Mar;112(3):375-82.

- Lee YQ, Kanagalingam J. Deep neck abscesses: the Singapore experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011 Apr;268(4):609-14. [CrossRef]

- Velhonoja J, Laaveri M, Soukka T, Irjala H, Kinnunen I. Deep neck space infections: an upward trend and changing characteristics. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(3):863-872. [CrossRef]

- Hidaka H, Yamaguchi T, Hasegawa J, et al. Clinical and bacteriological influence of diabetes mellitus on deep neck infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head &Neck. 2015;37(10): 1536-1546. [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.-I.; Ho, C.-Y.; Chin, S.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chan, K.-C.; Chen, S.-L. Sequential Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Deep Neck Infections: Comparison of the Clinical Characteristics of Patients with and without Diabetes Mellitus. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1383. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; Hoang, H.; Choi, J.-S. Dynamics of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio (LMR), and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) in Patients with Deep Neck Infection. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6105. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-L.; Chin, S.-C.; Chan, K.-C.; Ho, C.-Y. A Machine Learning Approach to Assess Patients with Deep Neck Infection Progression to Descending Mediastinitis: Preliminary Results. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2736. [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R. H., Douglas, C. M., Montgomery, J., Clark, L. J. (2018). The hidden cost of deep neck space infections. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 100(2), 129–134.

- Bigus, S., Russmüller, G., Starzengruber, P., Reitter, H., Sacher, C. L. (2023). Antibiotic resistance of the bacterial spectrum of deep space head and neck infections in oral and maxillofacial surgery - a retrospective study. Clinical oral investigations, 27(8), 4687–4693. [CrossRef]

- Sokouti, M., Nezafati, S. (2009). Descending necrotizing mediastinitis of oropharyngeal infections. Journal of dental research, dental clinics, dental prospects, 3(3), 82–85. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. L., Chin, S. C., Chan, K. C., Ho, C. Y. (2023). A Machine Learning Approach to Assess Patients with Deep Neck Infection Progression to Descending Mediastinitis: Preliminary Results. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 13(17), 2736.

- Velhonoja, J., Lääveri, M., Soukka, T., Irjala, H., Kinnunen, I. (2020). Deep neck space infections: an upward trend and changing characteristics. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 277(3), 863–872.

- Gallo, O., Deganello, A., Meccariello, G., Spina, R., Peris, A. (2012). Vacuum-assisted closure for managing neck abscesses involving the mediastinum. The Laryngoscope, 122(4), 785–788. [CrossRef]

- Adam, S., Sama, H. D., Chossegros, C., Bouassalo, M. K., Akpoto, M. Y., Kpemissi, E. (2017). Improvised Vacuum-Assisted Closure for severe neck infection in poorly equipped conditions. Journal of stomatology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, 118(3), 178–180. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, J., Hidaka, H., Tateda, M., Kudo, T., Sagai, S., Miyazaki, M., Katagiri, K., Nakanome, A., Ishida, E., Ozawa, D., Kobayashi, T. (2011). An analysis of clinical risk factors of deep neck infection. Auris, nasus, larynx, 38(1), 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C. Y., Wang, Y. C., Chin, S. C., Chen, S. L. (2022). Factors Creating a Need for Repeated Drainage of Deep Neck Infections. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 12(4), 940. [CrossRef]

- Celakovsky, P., Kalfert, D., Tucek, L., Mejzlik, J., Kotulek, M., Vrbacky, A., Matousek, P., Stanikova, L., Hoskova, T., Pasz, A. (2014). Deep neck infections: risk factors for mediastinal extension. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 271(6), 1679–1683.

- Wang, Y., Chen, X. M., Zhang, H., Li, D. J., Wang, Q., Song, X. C. (2020). Zhonghua er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of otorhinolaryngology head and neck surgery, 55(4), 358–362.

- Wei, D., Bi, L., Zhu, H., He, J., Wang, H. (2017). Less invasive management of deep neck infection and descending necrotizing mediastinitis: A single-center retrospective study. Medicine, 96(15), e6590.

- Tapiovaara, L., Bäck, L., Aro, K. (2017). Comparison of intubation and tracheotomy in patients with deep neck infection. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 274(10), 3767–3772.

- Kim, Y., Han, S., Cho, D. G., Jung, W. S., Cho, J. H. (2022). Optimal Airway Management in the Treatment of Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis Secondary to Deep Neck Infection. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery: official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 80(2), 223–230.

- Gargava, A., Raghuwanshi, S. K., Verma, P., Jaiswal, S. (2022). Deep Neck Space Infection a Study of 150 Cases at Tertiary Care Hospital. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery: official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India, 74(Suppl 3), 5832–5835.

- Priyamvada, S., Motwani, G. (2019). A Study on Deep Neck Space Infections. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery: official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India, 71(Suppl 1), 912–917.

- Venegas Pizarro, M. D. P., Martínez Téllez, E., León Vintró, X., Quer Agustí, M., Trujillo-Reyes, J. C., Libreros-Niño, A., Planas Cánovas, G., Belda-Sanchis, J. (2023). Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: key points to reduce the high associated mortality in a consecutive case series. Mediastinum (Hong Kong, China), 8, 8. [CrossRef]

- Rzepakowska, A., Rytel, A., Krawczyk, P., Osuch-Wójcikiewicz, E., Widłak, I., Deja, M., Niemczyk, K. (2021). The Factors Contributing to Efficiency in Surgical Management of Purulent Infections of Deep Neck Spaces. Ear, nose, throat journal, 100(5), 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, T., Scherzad, A., Hagen, R., Hackenberg, S. (2022). Deep neck infections with and without mediastinal involvement: treatment and outcome in 218 patients. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 279(3), 1585–1592.

- Desa, C., Tiwari, M., Pednekar, S., Basuroy, S., Rajadhyaksha, A., Savoiverekar, S. (2023). Etiology and Complications of Deep Neck Space Infections: A Hospital Based Retrospective Study. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery: official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India, 75(2), 697–706.

- Bal, K. K., Unal, M., Delialioglu, N., Oztornaci, R. O., Ismi, O., Vayisoglu, Y. (2022). Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in deep neck infections: an analysis of 74 consecutive patients. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology, 88(4), 511–522.).

- Boscolo-Rizzo, P., Stellin, M., Muzzi, E., Mantovani, M., Fuson, R., Lupato, V., Trabalzini, F., Da Mosto, M. C. (2012). Deep neck infections: a study of 365 cases highlighting recommendations for management and treatment. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS: affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 269(4), 1241–1249.

- Hidaka, H., Yamaguchi, T., Hasegawa, J., Yano, H., Kakuta, R., Ozawa, D., Nomura, K., Katori, Y. (2015). Clinical and bacteriological influence of diabetes mellitus on deep neck infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head & neck, 37(10), 1536–1546.

- Beka, D., Lachanas, V. A., Doumas, S., Xytsas, S., Kanatas, A., Petinaki, E., Skoulakis, C. (2019). Microorganisms involved in deep neck infection (DNIs) in Greece: detection, identification and susceptibility to antimicrobials. BMC infectious diseases, 19(1), 850.

- Almutairi, D., Alqahtani, R., Alshareef, N., Alghamdi, Y. S., Al-Hakami, H. A., Algarni, M. (2020). Correction: Deep Neck Space Infections: A Retrospective Study of 183 Cases at a Tertiary Hospital. Cureus, 12(3), c29.

- Hidaka, H., Yamaguchi, T., Hasegawa, J., Yano, H., Kakuta, R., Ozawa, D., Nomura, K., Katori, Y. (2015). Clinical and bacteriological influence of diabetes mellitus on deep neck infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head & neck, 37(10), 1536–1546.

- Li, R. M., Kiemeney, M. (2019). Infections of the Neck. Emergency medicine clinics of North America, 37(1), 95–107.

- Kong, W., Zhang, X., Li, M., Yang, H. (2024). Microbiological analysis and antibiotic selection strategy in neck abscesses among patients with diabetes mellitus. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology: official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 281(3), 1515–1523.

- Gao, W., Lin, Y., Yue, H., Chen, W., Liu, T., Ye, J., Cai, Q., Ye, F., He, L., Xie, X., Xiong, G., Wu, J., Wang, B., Wen, W., Lei, W. (2022). Bacteriological analysis based on disease severity and clinical characteristics in patients with deep neck space abscess. BMC infectious diseases, 22(1), 280.

- Huttner, B., Goossens, H., Verheij, T., Harbarth, S., CHAMP consortium (2010). Characteristics and outcomes of public campaigns aimed at improving the use of antibiotics in outpatients in high-income countries. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 10(1), 17–31.

- Rhodes, A., Evans, L. E., Alhazzani, W., Levy, M. M., Antonelli, M., Ferrer, R., Kumar, A., Sevransky, J. E., Sprung, C. L., Nunnally, M. E., Rochwerg, B., Rubenfeld, G. D., Angus, D. C., Annane, D., Beale, R. J., Bellinghan, G. J., Bernard, G. R., Chiche, J. D., Coopersmith, C., De Backer, D. P., … Dellinger, R. P. (2017). Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive care medicine, 43(3), 304–377.

- Walker, P. C., Karnell, L. H., Ziebold, C., Kacmarynski, D. S. (2013). Changing microbiology of pediatric neck abscesses in Iowa 2000-2010. The Laryngoscope, 123(1), 249–252. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T. T., Tseng, F. Y., Yeh, T. H., Hsu, C. J., Chen, Y. S. (2006). Factors affecting the bacteriology of deep neck infection: a retrospective study of 128 patients. Acta oto-laryngologica, 126(4), 396–401. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Group study N=138 cases |

Complications of deep neck infections |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present, n=47 | Absent, n=91 | |||

| Gender, male / female, n (%) |

108 / 30 (78.26 / 21.74) |

34 / 13 (31.48 / 43.33) |

74 / 17 (68.52 / 56.67) |

0.2315 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 52.9 (14.9) | 59.2 (13.9) | 49.8 (14.4) | 0.0003 |

| Smoking | 39 (28.26) | 35 (74.47) | 4 (4.40) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 6 (4.34) | 6 (0.12) | 1 (0.01) | 0.0140 |

| Blood test - Laboratory test | ||||

| Leukocytes, mm3, mean (SD) | 15418.2 (5161.6) | 16164.4 (5250.9) | 12032.8 (5101.2) | 0.0235 |

| Neutrophil ratio (%) | 109.2 (10.5) | 131.6 (11.5) | 98.8 (9.7) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 9.4 (6.7) | 6.2 (5.3) | 10.1 (7.6) | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 12.1 (9.6) | 19.8 (8.8) | 10.2 (8.4) | 0.0041 |

| ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), mean (SD) | 49.2 (16.75) | 56.3 (14.5) | 44.7 (11.2) | 0.0128 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 76.9 (11.6) | 119.4 (21.3) | 61.8 (9.5) | 0.0017 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 588.9 (95.6) | 639.4 (97.7) | 563.3 (84.0) | < 0.001 |

| Presepsin, pg/mL, mean (SD) | 573.5 (454.7) | 967.1 (709.1) | 295.7 (173.9) | 0.0278 |

| C reactive protein, mg/L, mean (SD) |

125.8 (22.8) | 138.1 (27.5) | 119.4 (17.2) | < 0.001 |

| Blood sugar, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 125.8 (58.5) | 160.7 (82.2) | 103.4 (21.1) | < 0.001 |

| Location | ||||

| submandibular and retrostylian | 17 (12.31) | 6 (12.76) | 11 (12.08) | 0.1579 |

| parapharyngeal and prevertebral | 28 (20.28) | 9 (19.14) | 19 (20.87) | 0.0897 |

| lateral cervical | 81 (58.69) | 26 (55.31) | 55 (60.43) | 0.0261 |

| anterior cervical | 26 (18.84) | 8 (17.02) | 18 (19.78) | 0.0579 |

| retropharyngeal | 17 (12.31) | 9 (19.14) | 8 (8.79) | 0.0046 |

| mediastini | 22 (15.94) | 20 (42.55) | 2 (2.19) | 0.0005 |

| Multispace involvement | 50 (36.23) | 28 (56) | 22 (44) | 0.0305 |

| Etiology factors | ||||

| odontogenic infections | 15 (10.86) | 5 (10.63) | 10 (10.98) | 0.1208 |

| pharyngo-tonsillar infections | 85 (61.59) | 28 (59.57) | 57 (62.63) | 0.0908 |

| epiglottis | 21 (15.21) | 10 (21.27) | 11 (12.08) | 0.0117 |

| foreign body | 3 (2.17) | 1 (2.12) | 2 (2.19) | 0.0869 |

| congenital cyst or trauma | 8 (5.79) | 2 (4.25) | 6 (6.59) | 0.0351 |

| laryngo-tracheal infections | 14 (10.14) | 12 (25.53) | 2 (2.19) | 0.0004 |

| lymphadenopathy | 15 (10.86) | 5 (10.63) | 10 (10.98) | 0.3275 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| pain | 54 (39.13) | 15 (31.91) | 39 (42.85) | 0.0032 |

| sore throat | 110 (79.71) | 36 (76.59) | 74 (81.31) | 0.0057 |

| dysphagia | 104 (75.36) | 39 (82.97) | 65 (71.42) | 0.0018 |

| dyspnoea | 15 (10.86) | 14 (29.78) | 7 (7.69) | 0.0009 |

| dysphonia | 8 (5.79) | 5 (10.63) | 3 (3.29) | 0.0016 |

| otalgia | 5 (3.62) | 6 (12.76) | 3 (3.29) | 0.0056 |

| chest pain | 4 (2.89) | 11 (23.4) | 5 (5.49) | 0.0014 |

| fever | 69 (50) | 23 (48.93) | 52 (57.14) | 0.0621 |

| Comorbidity, present, n(%) | 61 (44.20) | 40 (85.11) | 21 (23.08) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 35 (25.36) | 26 (55.31) | 9 (9.89) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 40 (28.98) | 29 (0.61) | 11 (0.12) | 0.0945 |

| Immunocompromised status | 25 (18.11) | 16 (0.34) | 9 (0.09) | 0.0056 |

| Malignant tumors | 4 (2.89) | 4 (0.08) | 1 (0.01) | 0.0858 |

| Number of days of hospitalization, mean (SD) median (IQR) |

16.3 (9.9) 14 (9 – 34) |

24.9 (12.2) 26 (11 – 45) |

8.32 (7.02) 11 (8 – 17) |

< 0.001 |

| Non_long term (< 2 weeks) Long-term (≥ 2 weeks) |

75 (54.34) 63 (45.65) |

13 / 62 17.33 / 82.67 |

34 / 29 53.97 / 46.03 |

< 0.001 |

| Mortality | 12 (8.70) | 12 (25.53) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Dependent variable: long-term hospitalization (over 2 weeks) Independent variable: Complications |

N = 138 n (%) |

Univariate model: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p – value | ||

| Airway Obstruction - Tracheotomy | 26 (18.84) | 6.51 | 2.27 – 18.62 | < 0.001 |

| Internal Jugular Vein Thrombosis | 5 (3.62) | 5.01 | 3.54 – 11.09 | 0.0154 |

| Pneumonia | 11 (7.97) | 3.49 | 2.89 – 9.78 | 0.0174 |

| Mediastinitis | 31 (22.46) | 4.81 | 2.96 – 9-72 | < 0.001 |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 6 (4.35) | 2.26 | 1.23 – 6.17 | 0.027 |

| Spontaneous fistulization | 17 (12.31) | 1.83 | 0.65 – 5.14 | 0.2491 |

| Renal insufficiency | 17 (12.31) | 1.39 | 0.55 – 3.86 | 0.5210 |

| Pathogens | Group study n=138 cases | Length of Hospital Stay | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non_long term (< 2 weeks) n = 75 |

Long-term (≥ 2 weeks) n = 63 |

|||

| Bacterial culture positive | 70 (50.7) | 25 (35.7) | 45 (64.3) | < 0.001 |

| Species | ||||

| Monomicrobial | 49 (35.5) | 28 (37.33) | 21 (33.33) | 0.8472 |

| Gram-positive aerobe | 39 (28.26) | 21 (28) | 18 (28.57) | 0.9791 |

| Gram-negative aerobe | 10 (7.24) | 6 (8.00) | 4 (6.34) | 0.0845 |

| Polymicrobial | 18 (13.04) | 5 (6.66) | 13 (20.63) | < 0.001 |

| 2 pathogens | 12 (8.69) | 4 (5.33) | 8 (12.69) | < 0.001 |

| 3 pathogens | 6 (4.34) | 1 (1.33) | 5 (7.93) | < 0.001 |

| Gram-positive aerobes | ||||

| Streptococcus viridans | 9 (6.52) | 4 (5.33) | 5 (7.93) | 0.0354 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 17 (12.31) | 8 (10.66) | 9 (14.28) | 0.0361 |

| Group C Streptococci | 8 (5.79) | 5 (6.66) | 3 (4.76) | 0.0247 |

| Streptococus B hemolitic | 6 (4.34) | 2 (2.66) | 4 (6.34) | 0.0019 |

| Streptococcus constellatus | 14 (10.14) | 6 (8.00) | 8 (12.69) | 0.0286 |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 6 (4.34) | 4 (5.33) | 2 (3.17) | 0.0174 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 11 (7.97) | 3 (4.00) | 8 (12.69) | < 0.001 |

| Klebsiela pneumoniae | 9 (6.52) | 2 (2.66) | 7 (11.11) | < 0.001 |

| Other gram-positive cocci | 6 (4.34) | 2 (2.66) | 4 (6.34) | 0.0187 |

| Enterococus species | 5 (3.62) | 3 (4.00) | 2 (3.17) | 0.6216 |

| Peptostreptococcus | 3 (2.17) | 2 (2.66) | 1 (1.58) | 0.0971 |

| Gram-negative aerobes | ||||

| Escherichia coli | 8 (5.79) | 5 (6.66) | 3 (4.76) | 0.1558 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 5 (3.62) | 3 (4.00) | 2 (3.17) | 0.6882 |

| Acinetobacter | 6 (4.34) | 2 (2.66) | 4 (6.34) | 0.0311 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 4 (2.89) | 2 (2.66) | 2 (3.17) | 0.8473 |

| Fusobacterium species | 1 (0.72) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.58) | 0.1274 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).