Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Literature Review

2. Theoretical and Methodical Design

- What operational risks are subjectively perceived by special police forces in high-risk situations? − This question explores the categorization of risks as subjectively experienced by officers in ad-hoc operations. The findings provide insights into perceived threats, including those related to tactical uncertainties, environmental constraints, and psychological pressures encountered in real-time crisis scenarios.

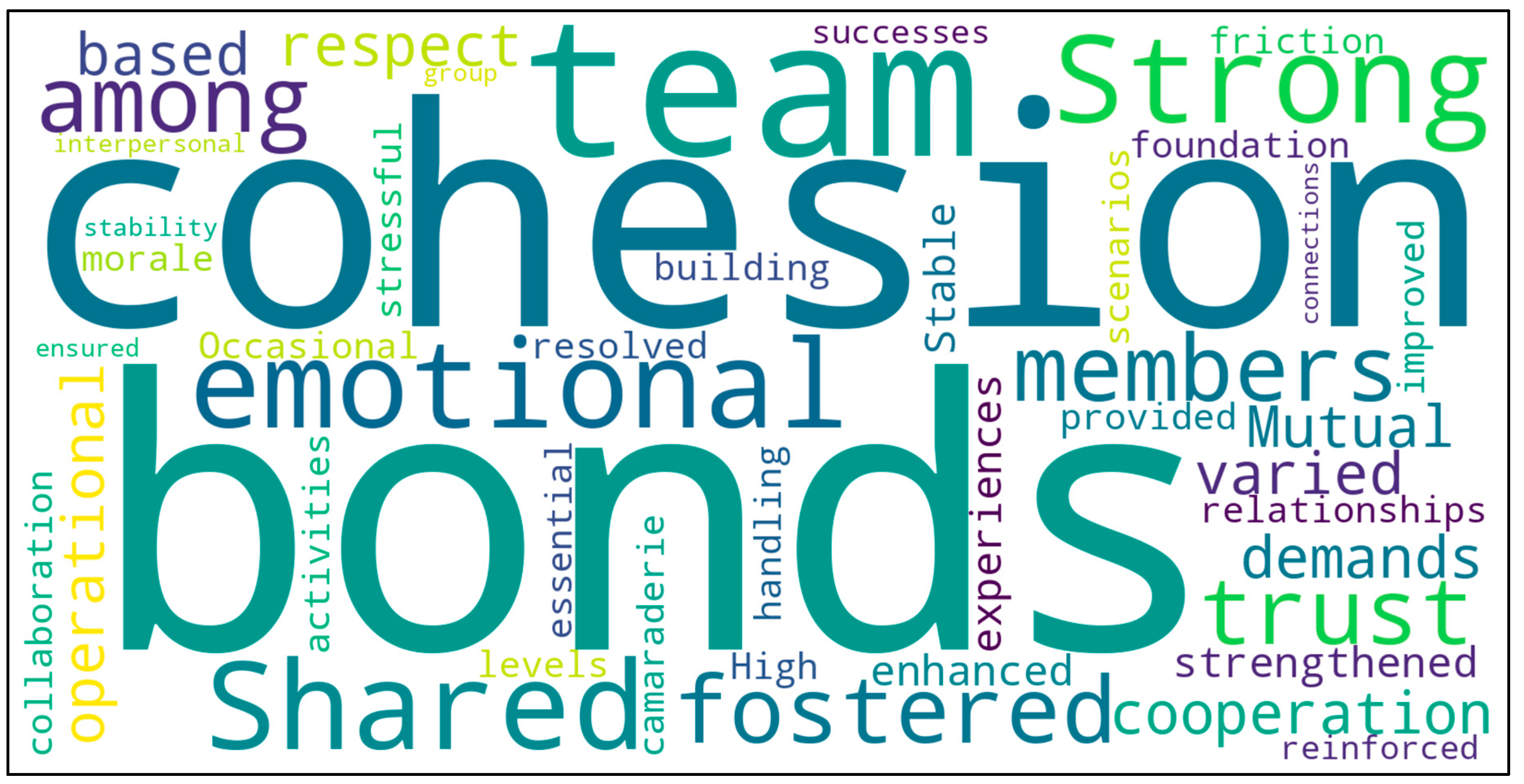

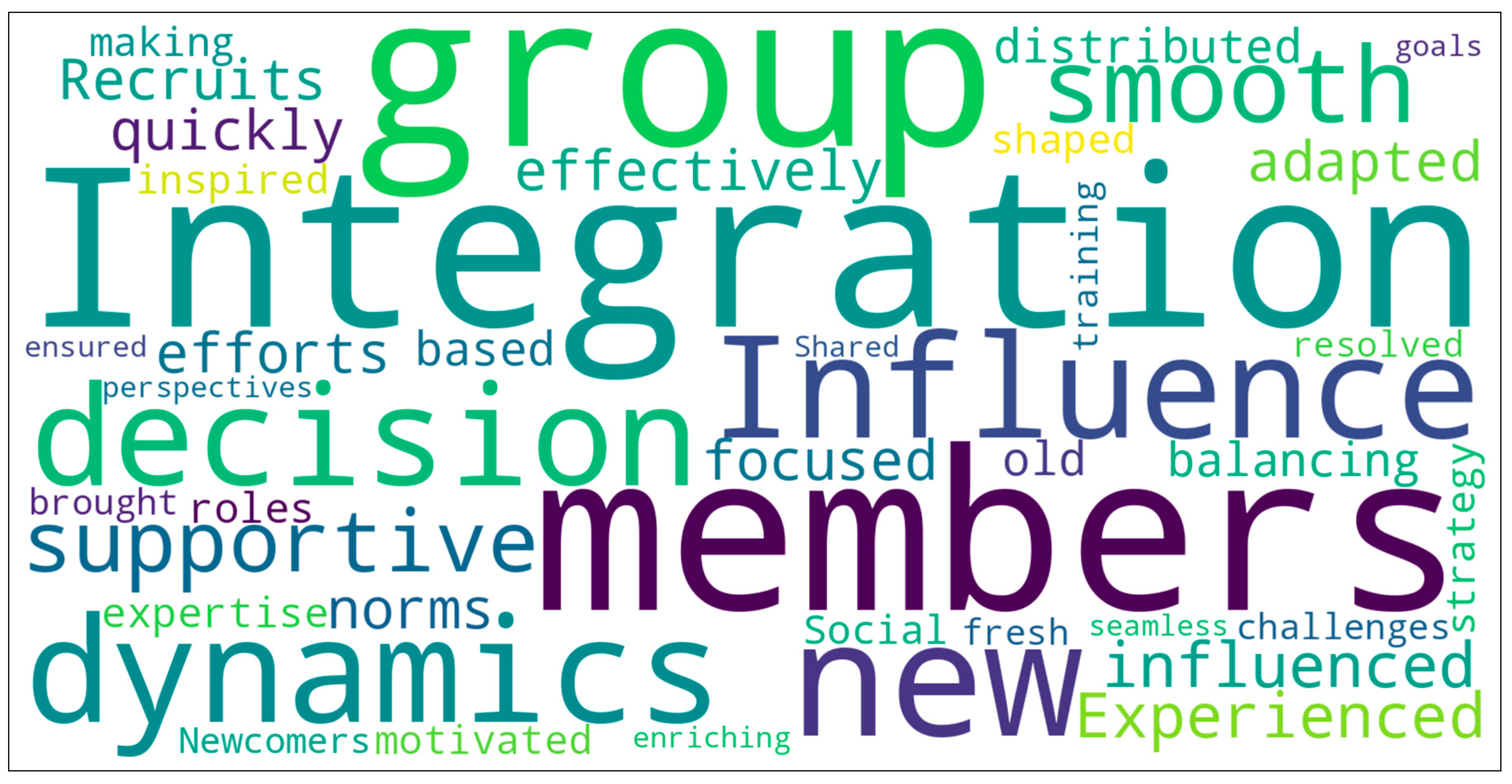

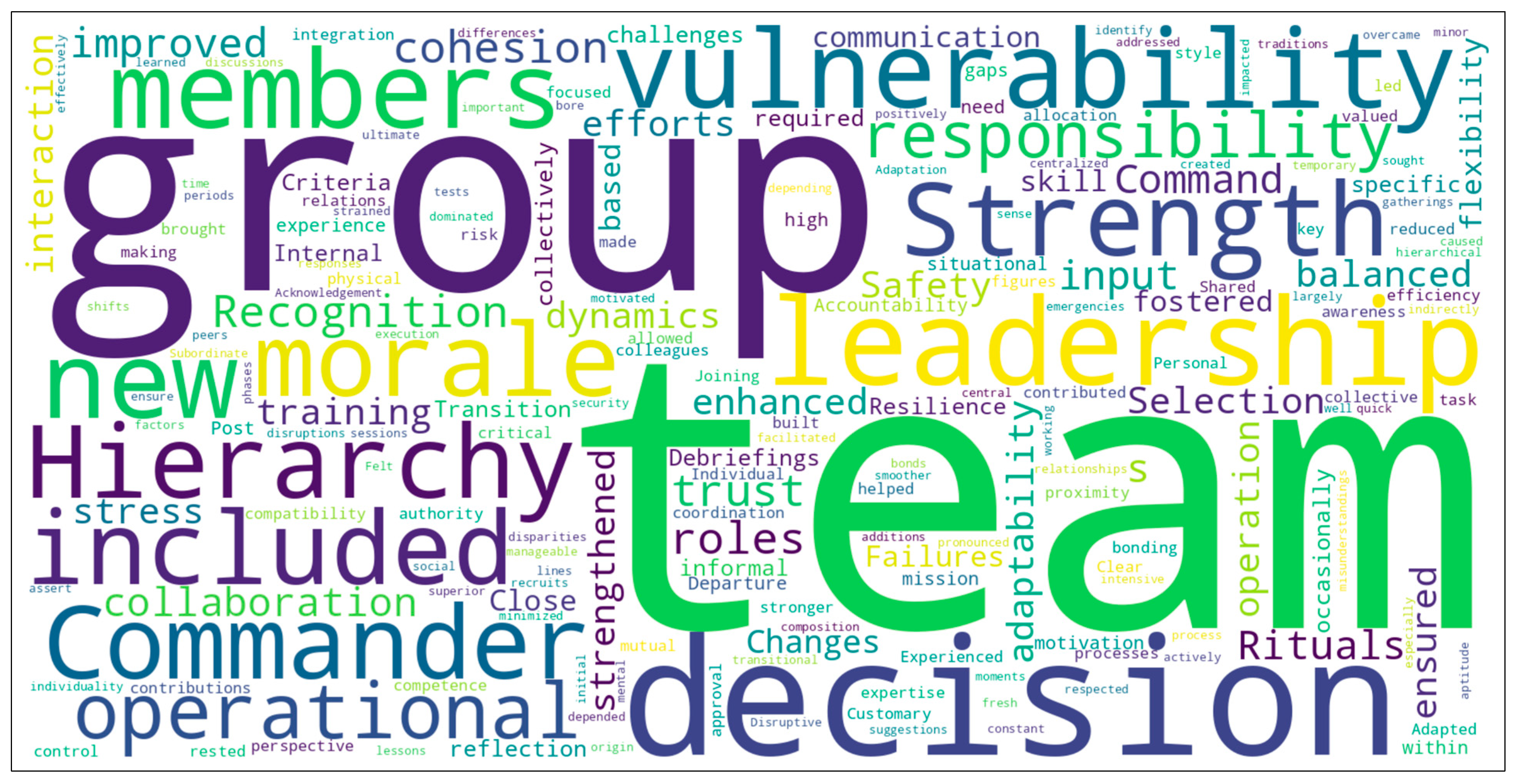

- How do group dynamic factors influence safety and the management of high-risk police operations? − The study examines key elements of group dynamics, including: a) communication and interaction – how information flows within the team and how members coordinate actions; b) interpersonal attraction and cohesion – the strength of emotional bonds, trust, and collaboration within the unit; c) social integration and influence – the ways in which new members are accepted and how individuals impact group behavior; d) power and control – the distribution of authority and decision-making structures within the unit;e) group culture – the shared norms, values, and beliefs that shape team cohesion and operational effectiveness. These factors are analyzed to assess their contribution to the safe and successful execution of high-risk operations.

- What influence does risk perception have on safety in high-risk operations, and what role does training play? − This section examines how officers perceive risk and how their awareness impacts safety. Additionally, it explores the role of training in enhancing situational awareness, improving decision-making, and reducing operational errors. The study highlights specific training strategies that reinforce risk perception and enhance overall operational readiness.

2.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Questionnaire Design

- a)

- Operational risks ‒ this section focused on identifying and categorizing the risks encountered during ad-hoc operations. Participants were asked to reflect on physical, psychological, and operational risks, providing specific examples of scenarios in which these risks became apparent;

- b)

- Risk perception ‒ the goal of this section was to understand how officers perceive and evaluate risks in high-pressure situations. Questions explored the influence of training and personal experience on their ability to recognize potential dangers and respond appropriately.

- c)

- Group dynamics ‒ to explore the socio-psychological aspects of operations, this section included questions on group cohesion, communication, and trust. Participants shared their perspectives on how these dynamics shaped decision-making and operational outcomes;

- d)

- Leadership and decision-making ‒ this segment examined the impact of leadership on risk management and team resilience. Questions addressed the balance between hierarchical authority and collaborative decision-making within the EKO Cobra framework;

- e)

- Training and preparedness ‒ feedback on training methods, including modular competency training (MKT) and scenario-based simulations, was the focus here. Participants evaluated the effectiveness of these programs in preparing them for real-world challenges;

- f)

- Technological and cultural factors ‒ the final section explored the role of modern technologies and intercultural considerations in enhancing operational safety and efficiency. Participants identified areas where improvements or innovations could strengthen outcomes.

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Exploring Correlations Through the Quantification of Qualitative Data

3.2. Descriptive Analysis of Qualitative Data

4. Discussion

Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Jasch, M. Kritische Lehre und Forschung in der Polizeiausbildung. Polizei und Gesellschaft: Transdisziplinäre Perspektiven zu Methoden, Theorie und Empirie reflexiver Polizeiforschung 2019, 231-250.

- Feltes, T. Polizeiliches Fehlverhalten und Disziplinarverfahren–ein ungeliebtes Thema. Überlegungen zu einem alternativen Ansatz. Die Polizei 2012, 10, 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.S.; Hong, S. A Study on the Risk of Terrorism by Simulated Guns and Homemade Explosives. Forum of Public Safety and Culture 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, E.; Michaud, P. “HIGH-RISK”: A Useful Tool for Improving Police Decision-Making in Hostage and Barricade Incidents. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 2015, 30, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, S.; LaFree, G.; Dugan, L.; Piquero, A. A Situational Model for Distinguishing Terrorist and Non-Terrorist Aerial Hijackings, 1948–2007. Justice Quarterly 2012, 29, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleck, G.; McElrath, K. The Effects of Weaponry on Human Violence. Social Forces 1991, 69, 669–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monuteaux, M.; Lee, L.; Hemenway, D.; Mannix, R.; Fleegler, E. Firearm Ownership and Violent Crime in the U.S.: An Ecologic Study. American journal of preventive medicine 2015, 49 2, 207-214. [CrossRef]

- Rowhani-Rahbar, A.; Zatzick, D.; Wang, J.; Mills, B.; Simonetti, J.; Fan, M.; Rivara, F. Firearm-Related Hospitalization and Risk for Subsequent Violent Injury, Death, or Crime Perpetration. Annals of Internal Medicine 2015, 162, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhieieva, D.; Kulyk, M.; Antoniuk, P.; Marko, S.; Isagova, N. Firearms as a means of committing criminal offenses. Cuestiones Políticas. [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.; Wintemute, G. Effects of policies designed to keep firearms from high-risk individuals. Annual review of public health 2015, 36, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Adem, O.; Aleksandar, I. Young adults’ fear of disasters: A case study of residents from Turkey, Serbia and Macedonia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2019, 35, 101095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho, M.; Santos, V.; Rasteiro, A.; Massuça, L. Physical Fitness and Psychosocial Profiles of Policewomen from Professional Training Courses and Bodyguard Special Police Sub-Unit. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 2023, 13, 1880–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, S.; Orr, R.; Pope, R. Profiling the Occupational Tasks and Physical Conditioning of Specialist Police. International Journal of Exercise Science 2019, 12, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marins, E.; David, G.; Del Vecchio, F. Characterization of the Physical Fitness of Police Officers: A Systematic Review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massuça, L.; Santos, V.; Monteiro, L. Identifying the Physical Fitness and Health Evaluations for Police Officers: Brief Systematic Review with an Emphasis on the Portuguese Research. Biology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, V.; Ravlyuk, I. Peculiarities of professional training of employees of the federal police and special police forces of Germany. Naukovyy Visnyk Dnipropetrovs'kogo Derzhavnogo Universytetu Vnutrishnikh Sprav 2020. [CrossRef]

- Silk, A.; Savage, R.; Larsen, B.; Aisbett, B. Identifying and characterising the physical demands for an Australian specialist policing unit. Applied ergonomics 2018, 68, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BM.I. Richtlinie für das Führungssystem der Sicherheitsexekutive in besonderen Lagen (RFbL). 2020, 1-31.

- Keplinger, R., Pühringer, L. Sicherheitspolizeigesetz. Polizeiausgabe. 2014.

- S., B.I. Richtlinien für das Einsatztraining. 2012, 7–30.

- Zöchbauer, G. Dienst- und Besoldungsrecht für Polizeibedienstete, 4. Aufl. St. Pölten: expresta Verlag.; 2023.

- Füllgrabe, U. Survivability – Gefahrenwahrnehmung und Gefahrenbewältigung in Verkehrssituationen. Verfügbar unter: https://psycharchives.org/en/item/e43c0bc3-1e82- 4ca5-9320-dd97e75162da (Zugriff am: 21.04.2024). 2002.

- Frise, E. The Psychological Selection of Officer Candidates in Austria. 2000.

- Stegăroiu, I.; Popescu, O.-A. The Recruitment And Selection Of Police Officers-Comparative Analysis Of Similar Policy In European States. 2010.

- BM.I. Ausbildungsplan zur Grundausbildung für den Exekutivdienst, S. BM.I. Ausbildungsplan zur Grundausbildung für den Exekutivdienst, S. 3–77. 2023.

- Kapusta, N.D.; Voracek, M.; Etzersdorfer, E.; Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Dervic, K.; Plener, P.L.; Schneider, E.; Stein, C.; Sonneck, G. Characteristics of police officer suicides in the Federal Austrian Police Corps. Crisis 2010.

- Frühwald, S.; Entenfellner, A.; Grill, W.; Korbel, C.; Frottier, P. Raising awareness about depression together with service users and relatives-results of workshops for police officers in Lower Austria. Neuropsychiatrie: Klinik, Diagnostik, Therapie und Rehabilitation: Organ der Gesellschaft Osterreichischer Nervenarzte und Psychiater 2011, 25, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh, I.; Tehrani, N. Psychological trauma risk management in the UK police service. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2019, 13, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.G.; Florig, H.K.; DeKay, M.L.; Fischbeck, P. Categorizing risks for risk ranking. Risk analysis 2000, 20, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slovic, P.; Weber, E.U. Perception of risk posed by extreme events. Regulation of Toxic Substances and Hazardous Waste (2nd edition)(Applegate, Gabba, Laitos, and Sachs, Editors), Foundation Press, Forthcoming 2013.

- Leiter, M.P.; Zanaletti, W.; Argentero, P. Occupational risk perception, safety training, and injury prevention: testing a model in the Italian printing industry. Journal of occupational health psychology 2009, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundmo, T. Associations between affect and risk perception. Journal of risk research 2002, 5, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. The role of risk perception for risk management. Reliability engineering & system Safety 1998, 59, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Namian, M.; Albert, A.; Zuluaga, C.M.; Behm, M. Role of safety training: Impact on hazard recognition and safety risk perception. Journal of construction engineering and management 2016, 142, 04016073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkert, G. Dynamisch, variabel, realitätsnah, in: Öffentliche Sicherheit. Das Magazin des Innenministeriums, 9/10, S. 103–105. Verfügbar unter: https://www.bmi.gv.at/magazinfiles/2021/09_10/virtuelles_training.pdf (Zugriff am: 23.03.2024). 2019.

- Tagesschau. Tödlicher Polizeischuss in Paris: Nicht zu erklären und nicht zu entschuldigen, Verfügbar unter: https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/europa/frankreich-tod- jugendlicher-100.html (Zugriff am: 05.03.2024). 2023.

- Staller, M.S., Körner, S. Training für den Einsatz I: Plädoyer für ein evidenzbasiertes polizeiliches Einsatztraining. Verfügbar unter:. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mario.

- Jager, J.; Klatt, T.; Bliesener, T. NRW-Studie: Gewalt gegen Polizeibeamtinnen und Polizeibeamte [North Rhine-Westphalian study: Violence against police officers]. Kiel: Institut für Psychologie, Christian-Albrechts-Universität 2013.

- Uwe, F. Survivability - Gefahrenwahrnehmung und Gefahrenbewältigung in Verkehrssituationen. In Proceedings of the 38. BDP-Kongress für Verkehrspsychologie Universität Regensburg, 2002.

- Pinizzotto, A.J.; Davis, E.F.; Miller Iii, C.E. In the line of fire: Violence against law enforcement. A Study of Selected Felonious Assaults on Law Enforcement Officers. Washington: United States. Department of Justice. Federal Bureau of Investigation. National Institute of Justice 1997.

- Memmert, D. Fußballspiele werden im Kopf entschieden: kognitives Training, Kreativität und Spielintelligenz im Amateur-und Leistungsbereich; Meyer & Meyer: 2019.

- Slidemodel. TDODAR Modell. Verfügbar unter: https://slidemodel.com/tdodar- decision-model/ (Zugriff am: 01.04.2024). 2022.

- Elbe, M. Die Einsatzorganisation als Lernende Organisation, in: Kern, E.M., Richter, G., Müller, J. and Voß, F.H. (Hrsg.) Einsatzorganisationen, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler Verlag, S. 139-165. 2020.

- Hupfeld, J. Wahrnehmungsverzerrungen im polizeilichen Alltag: Ursachen, Auswirkungen und Präventionsmöglichkeiten für Vorgesetzte. Verfügbar unter:. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310799955_Wahrnehmungsverzerrungen_im_poliz eilichen_Alltag.

- Köhnken, G. Personenidentifizierung, in: Steller, M. und Volbert, R. (Hrsg.), Psychologie im Strafverfahren, Bern: Hans Huber Verlag. 1997.

- Haller, L. Risikowahrnehmung und Risikoeinschätzung, Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Konvač. 2003.

- Münkler, H. Strategien der Sicherung: Welten der Sicherheit und Kulturen des Risikos. Theoretische Perspektiven; na: 2010.

- Hupfeld, J. Wahrnehmungsverzerrungen im polizeilichen Alltag: Ursachen, Auswirkungen und Präventionsmöglichkeiten für Vorgesetzte. 2002.

- Uwe, F. Gewaltvermeidung durch die Benutzung der TIT FOR TAT – Strategie. Magazin für die Polizei 2000, 31, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D. Psychology, risk and safety. Professional Safety 2003, 48, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Uwe, F. Survivability - Gefahrenwahrnehmung und Gefahrenbewältigung in Verkehrssituationen., in In Proceedings of the BDP-Kongress für Verkehrspsychologie: Universität Regensburg., 2002.

- Witzel, A. The Problem-centered Interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2000, 1. [CrossRef]

- Helfferich, C. Leitfaden-und experteninterviews. Handbuch methoden der empirischen sozialforschung 2019, 669–686. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Austria: Population by sex and age groups, Demographic Yearbook. 2023.

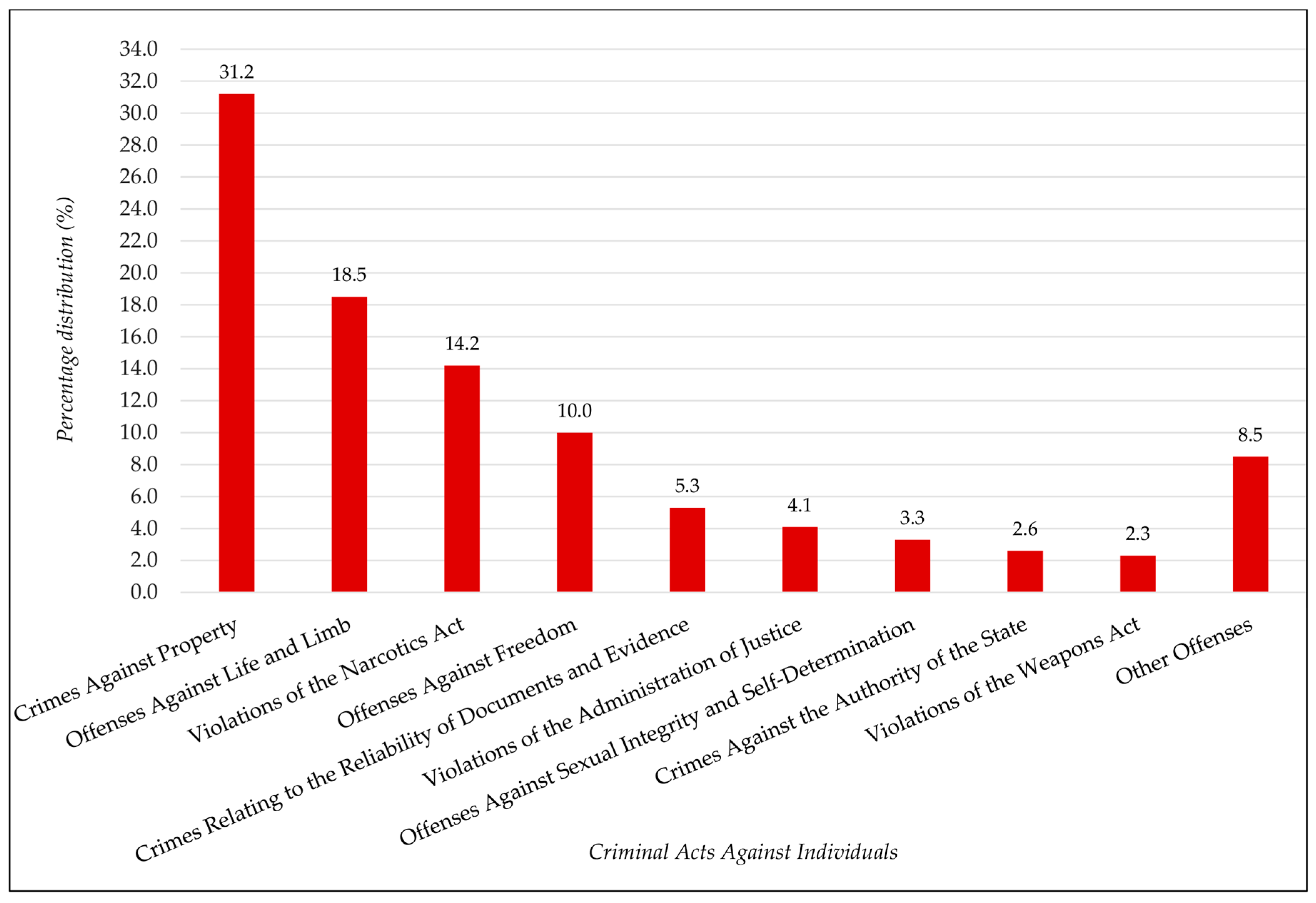

- Police crime statistics. 2024.

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken (Beltz Pädagogik, 12., überarb. Aufl.). 2015.

- Wolbers, J.; Boersma, K.; Groenewegen, P. Introducing a Fragmentation Perspective on Coordination in Crisis Management. Organization Studies 2018, 39, 1521–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militello, L.; Patterson, E.; Bowman, L.; Wears, R. Information flow during crisis management: challenges to coordination in the emergency operations center. Cognition, Technology & Work 2007, 9, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, R. Police intelligence: connecting-the-dots in a network society. Policing and Society 2017, 27, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Tanasić, J.; Renner, R.; Rokvić, V.; Beriša, H. Comprehensive Risk Analysis of Emergency Medical Response Systems in Serbian Healthcare: Assessing Systemic Vulnerabilities in Disaster Preparedness and Response. In Proceedings of the Healthcare; 2024; p. 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Dragašević, A.; Protić, D.; Janković, B.; Nikolić, N.; Milošević, P. Fire safety behavior model for residential buildings: Implications for disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, M.V. The impact fo demographic factors on the expetation of assistance from the police inn natural disaster. Serbian Science Today 2016, 1, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V.; Ivanov, A.; Sadiyeh, A. Knowledge and perceptions of students of the Academy of criminalistic and police studies about natural disasters. In Proceedings of the International scientific conference Archibald Reiss days Belgrade; 2015; pp. 371–389. [Google Scholar]

- Janković, B.; Cvetković, V. Public perception of police behaviors in the disaster COVID-19 – the Case of Serbia. Policing An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 2020, 43, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, B.; Cvetković, V.; Aleksandar, I. Perceptions of private security: А case study of students from Serbia and North Macedonia. Journal of Criminalistic and Law, NBP 2019, 24.

- Janković, B.; Cvetković, V.; Ivanović, Z.; Petrović, S.; Otašević, B. Sustainable Development of Trust and Presence of Police in Schools: Implications for School Safety Policy. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Lane, D. Social theory and system dynamics practice. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1999, 113, 501–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermos, S. The Dynamics of Group Cognition. Minds and Machines 2016, 26, 409–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perc, M.; Gómez-Gardeñes, J.; Szolnoki, A.; Floría, L.; Moreno, Y. Evolutionary dynamics of group interactions on structured populations: a review. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2013, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Stewart, A. Power dynamics in intergroup relations. Current opinion in psychology 2019, 33, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prundeanu, O. Relevant factors in the analysis of group dynamics. Annals of Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Psychology Series 2022. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Berg, D. A Paradoxical Conception of Group Dynamics. Human Relations 1987, 40, 633–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetlock, P.; Peterson, R.; McGuire, C.; Chang, S.; Feld, P. Assessing political group dynamics : a test of the groupthink model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1992, 63, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatnani, V.; Barlow, J. The Effect of Individual Traits on Emerging Roles in Synchronous Computer-Mediated Groups. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 2024, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Rogers, K.; Nacke, L.; Drachen, A.; Wade, A. Communication Sequences Indicate Team Cohesion: A Mixed-Methods Study of Ad Hoc League of Legends Teams. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 2022, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, C.; Spink, K. Member communication as network structure: Relationship with task cohesion in sport. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2020, 18, 764–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.; Adam, M.; Teubner, T. Time pressure in human cybersecurity behavior: Theoretical framework and countermeasures. Comput. Secur. 2020, 97, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maule, A.; Hockey, G.; Bdzola, L. Effects of time-pressure on decision-making under uncertainty: changes in affective state and information processing strategy. Acta psychologica 2000, 104 3, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y. The nonlinear effect of time pressure on innovation performance: New insights from a meta-analysis and an empirical study. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelfrey, W.; Young, A. Police Crisis Intervention Teams: Understanding Implementation Variations and Officer-Level Impacts. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 2020, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostinga, M.S.D.; Giebels, E.; Taylor, P. Communication Error Management in Law Enforcement Interactions: A Sender’s Perspective. Criminal Justice and Behavior 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, B.; Evain, J.; Piot, J.; Wolf, R.; Bertrand, P.; Louys, V.; Terrisse, H.; Bosson, J.; Albaladéjo, P.; Picard, J. Positive communication behaviour during handover and team-based clinical performance in critical situations: a simulation randomised controlled trial. British journal of anaesthesia 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.; Kukenberger, M.; D’Innocenzo, L.; Reilly, G. Modeling reciprocal team cohesion-performance relationships, as impacted by shared leadership and members' competence. The Journal of applied psychology 2015, 100 3, 713–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedwell, W. Adaptive Team Performance: The Influence of Membership Fluidity on Shared Team Cognition. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, J. Adaptation of teams in response to unforeseen change: effects of goal difficulty and team composition in terms of cognitive ability and goal orientation. The Journal of applied psychology 2005, 90 6, 1153–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.; Burke, P. Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M. Social Identity Theory. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.; Grieve, P. Social Identity Theory and the Crisis of Confidence in Social Psychology: A Commentary, and Some Research on Uncertainty Reduction. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 1999, 2, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Montes-Soldado, R.; Herrera, F. Social network group decision making: Managing self-confidence-based consensus model with the dynamic importance degree of experts and trust-based feedback mechanism. Inf. Sci. 2019, 505, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapeckaitę, R.; Bagdžiūnienė, D. Relationships between team characteristics and soldiers’ organizational commitment and well-being: the mediating role of psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Jue, J. The Mediating Effect of Group Cohesion Modulated by Resilience in the Relationship between Perceived Stress and Military Life Adjustment. Sustainability 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuzinge, R.; Visse, M.; Duyndam, J.; Vermetten, E. Social Embeddedness of Firefighters, Paramedics, Specialized Nurses, Police Officers, and Military Personnel: Systematic Review in Relation to the Risk of Traumatization. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; De Smet, H.; Uitdewilligen, S.; Schreurs, B.; Leysen, J. Participative or Directive Leadership Behaviors for Decision-Making in Crisis Management Teams? Small Group Research 2022, 53, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayirli, T.; Stark, N.; Hardy, J.; Peabody, C.; Kerrissey, M. Centralization and democratization: Managing crisis communication in health care delivery. Health Care Management Review 2023, 48, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, L.; De Jong, B.; Schouten, M.; Dannals, J. Why and When Hierarchy Impacts Team Effectiveness: A Meta-Analytic Integration. Journal of Applied Psychology 2018, 103, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, P.; Kaplan, H.; Boone, J. A theory of leadership in human cooperative groups. Journal of theoretical biology 2010, 265 4, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, A.; Panari, C.; Caricati, L.; Mariani, M.G. The relationship between leadership and adaptive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulutlar, F.; Kamaşak, R. Complex Adaptive Leadership for Performance: A Theoretical Framework. 2014, 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Heifetz, R.; Grashow, A.; Linsky, M. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. 2009.

- Jefferies, S. Adaptive Leadership in a Socially Revolving World: A Symbolic Interactionist Lens of Adaptive Leadership Theory. Performance Improvement 2017, 56, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, B.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Marion, R.; Seers, A.; Orton, J.; Schreiber, C. Complexity leadership theory: An interactive perspective on leading in complex adaptive systems. Emergence: Complexity and Organization 2006, 8. [CrossRef]

- Korn, J. Crises and Systems Thinking. Advances in Engineering Software 2020, 8, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D. Crisis Management Policy and Hierarchical Networks. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Safaei, A.S.; Farsad, S.; Paydar, M. Emergency logistics planning under supply risk and demand uncertainty. Operational Research 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.; Nowell, B. Networks and Crisis Management. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ayres, P. Something old, something new from cognitive load theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 113, 106503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriënboer, J.; Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory and Complex Learning: Recent Developments and Future Directions. Educational Psychology Review 2005, 17, 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; Tuovinen, J.; Tabbers, H.; Van Gerven, P. Cognitive Load Measurement as a Means to Advance Cognitive Load Theory. Educational Psychologist 2003, 38, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, J.; Maggio, L.; Cate, T.; Van Gog, T.; Young, J.; O’Sullivan, P. Cognitive load theory for training health professionals in the workplace: A BEME review of studies among diverse professions: BEME Guide No. 53. Medical Teacher 2018, 41, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Measuring cognitive load. Perspectives on Medical Education 2018, 7, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heusler, B.; Sutter, C. Shoot or Don’t Shoot? Tactical Gaze Control and Visual Attention Training Improves Police Cadets’ Decision-Making Performance in Live-Fire Scenarios. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, R.; Lewinski, W.; Heidner, G.S.; Lawton, J.; Allen, C.; Albin, M.; Murray, N. Assessing between-officer variability in responses to a live-acted deadly force encounter as a window to the effectiveness of training and experience. Ergonomics 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleygrewe, L.; Hutter, R.; Koedijk, M.; Oudejans, R. Virtual reality training for police officers: a comparison of training responses in VR and real-life training. Police Practice and Research 2023, 25, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martaindale, M.; Sandel, W.; Duron, A.; McAllister, M. Can a Virtual Reality Training Scenario Elicit Similar Stress Response as a Realistic Scenario-Based Training Scenario? Police Quarterly 2023, 27, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahora, M.; Hanafi, S.; Chien, V.; Compton, M. Preliminary Evidence of Effects of Crisis Intervention Team Training on Self-Efficacy and Social Distance. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2008, 35, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, Z.; Songer, D.; Schriver, J. A National Survey of Police Mental Health Training. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 2020, 36, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassell, K. The impact of Crisis Intervention Team Training for police. International Journal of Police Science & Management 2020, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, J.; Munetz, M.; Gil, K.; Ritter, C. Crisis intervention team training for police officers responding to mental disturbance calls. Psychiatric services 2006, 57 2, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, S.; Ross, K.; Jentsch, F. A Team Cognitive Readiness Framework for Small-Unit Training. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making 2012, 6, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Pierce, L. Adaptive Teams. 2007.

- Mammadov, R.А. The application of special operations forces combat tactics. The Proceeding "Bulletin MILF" 2024. [CrossRef]

- Raybourn, E.; Mendini, K.; Heneghan, J.; Deagle, E. Adaptive thinking & leadership simulation game training for special forces officers. 2005.

- White, S.; Mueller-Hanson, R.; Dorsey, D.; Pulakos, E.; Wisecarver, M.; Deagle, E.; Mendini, K. Developing Adaptive Proficiency in Special Forces Officers. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Yammarino, F.; Mumford, M.; Connelly, M.; Dionne, S. Leadership and Team Dynamics for Dangerous Military Contexts. Military Psychology 2010, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Dym, A.; Venegas-Borsellino, C.; Bangar, M.; Kazzi, M.; Lisenenkov, D.; Qadir, N.; Keene, A.; Eisen, L. Comparison between Simulation-based Training and Lecture-based Education in Teaching Situation Awareness. A Randomized Controlled Study. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 2017, 14, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, M.; Sepanski, R.; Goldberg, S.; Shah, S. Improving Teamwork, Confidence, and Collaboration Among Members of a Pediatric Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit Multidisciplinary Team Using Simulation-Based Team Training. Pediatric Cardiology 2013, 34, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, V.; Reime, M. Scenario-based simulation training as a method to increase nursing students' competence in demanding situations in dementia care. A mixed method study. Nurse education in practice 2018, 33, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, F.; Nguyen, Q.; Baetzner, A.; Sjöberg, D.; Gyllencreutz, L. Exploring medical first responders’ perceptions of mass casualty incident scenario training: a qualitative study on learning conditions and recommendations for improvement. BMJ Open 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahoodik, S.; Yamani, Y. Effectiveness of risk awareness perception training in dynamic simulator scenarios involving salient distractors. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, C.; Clostermann, J.-P.; Hoc, J.-M. Situation Awareness and the Decision-Making Process in a Dynamic Situation: Avoiding Collisions at Sea. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making 2008, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, K.; Vettel, J.; Vettel, J.; Vettel, J.; Patton, D.; Eddy, M.; Davis, F.; Garcia, J.; Garcia, J.; Spangler, D.; et al. Different profiles of decision making and physiology under varying levels of stress in trained military personnel. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology 2018, 131, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, T.; LaFiandra, M. The perception of team engagement reduces stress induced situation awareness overconfidence and risk-taking. Cognitive Systems Research 2017, 46, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcke, K.; Brand, M. Decision making under stress: A selective review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2012, 36, 1228–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.; Bellis, M. Knowing the risk. Public Health 2001, 115, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.; Ruiter, R.; Waters, E. Combining risk communication strategies to simultaneously convey the risks of four diseases associated with physical inactivity to socio-demographically diverse populations. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2018, 41, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, G.; Balchin, K.; Mufamadi, P. Evaluating risk awareness in undergraduate students studying mechanical engineering. European Journal of Engineering Education 2010, 35, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, E.; MacNamara, A.; Sandre, A.; Lonsdorf, T.; Weinberg, A.; Morriss, J.; Van Reekum, C. Intolerance of uncertainty and threat generalization: A replication and extension. Psychophysiology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagina, V.; Apalikova, I. FORMATION OF PSYCHOLOGICAL STABILITY CADETS OF A MILITARY UNIVERSITY. Сoвременные прoблемы науки и oбразoвания (Modern Problems of Science and Education) 2021. [CrossRef]

- Goncharova, N.; Ivanova, A. Differential psychological analysis of the features of psychological stability of the law enforcement officials. Vestnik of the St. Petersburg University of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, К. Theoretical and methodological fundamentals of psychological stability problematics of the Armed Forces of Ukraine personnel conditioned by the russian federation armed aggression. Visnyk Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. Military-Special Sciences 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Sun, S.; Yen, J. On Shared Situation Awareness for Supporting Human Decision-Making Teams. 2005, 17-24.

- Ghobadi, S.; Mathiassen, L. Risks to Effective Knowledge Sharing in Agile Software Teams: A Model for Assessing and Mitigating Risks. Information Systems Journal 2017, 27, 699–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotrecchiano, G.; Mallinson, T.; Leblanc-Beaudoin, T.; Schwartz, L.; Lazar, D.; Falk-Krzesinski, H. Individual motivation and threat indicators of collaboration readiness in scientific knowledge producing teams: a scoping review and domain analysis. Heliyon 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Li, N.; Luo, Y. Authoritarian Leadership in Organizational Change and Employees’ Active Reactions: Have-to and Willing-to Perspectives. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslahchi, M. Leadership and collective learning: a case study of a social entrepreneurial organisation in Sweden. The Learning Organization 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Song, D.; He, C. Linking authoritarian leadership to employee creativity. Chinese Management Studies 2018, 12, 384–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.; Cheung, G.; Cooper–Thomas, H. The influence of dispositions and shared leadership on team–member exchange. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2021, 36, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.; Mathieu, J.; Rapp, T.; Gilson, L.; Kleiner, C. Team leader coaching intervention: An investigation of the impact on team processes and performance within a surgical context. The Journal of applied psychology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbäck, E.; Espinosa, J. Effective Coordination of Shared Leadership in Global Virtual Teams. Journal of Management Information Systems 2019, 36, 321–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riener, G.; Wiederhold, S. Team Building and Hidden Costs of Control. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 2016, 123, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, S.; O'Connor, G. First Among Equals: The Effect of Team Leader Characteristics on the Internal Dynamics of Cross-Functional Product Development Teams. Journal of Product Innovation Management 2009, 26, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agung, A.; Kharisma, M.; Dewa, I.; Satrya, G.; Ciputra, U.; Surabaya, C.C. Participatory Leadership Style of Top Management at Medi Groups Bali. Asia Pacific Journal of Management and Education 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitson, R.; Xu, H.; Hmielowski, J. Understanding the efficacy of leadership communication styles in flex work contexts. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rennie, S.; Prieur, L.; Platt, M. Communication style drives emergent leadership attribution in virtual teams. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J. Emotions and Leadership: The Role of Emotional Intelligence. Human Relations 2000, 53, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasø, L.; Einarsen, S. Emotion regulation in leader–follower relationships. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2008, 17, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, B.; Connelly, S. Emotion Regulation Tendencies and Leadership Performance: An Examination of Cognitive and Behavioral Regulation Strategies. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, E. Training an Interdisciplinary Team in Communication and Decision-Making Skills. Small Group Research 1994, 25, 25–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, M. Improving team effectiveness using tactical decision games. Safety Science 2009, 47, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.; Sabella, M.; Burke, C.; Zaccaro, S. The impact of cross-training on team effectiveness. The Journal of applied psychology 2002, 87 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Conte, D.; Clemente, F. Decision-Making in Youth Team-Sports Players: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, R.; Salas, E. The Role of Planning in Coordinated Team Decision Making: Implications for Training. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 1993, 37, 1238–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.; Macdonald, P. A Look at Leadership Styles and Workplace Solidarity Communication. International Journal of Business Communication 2019, 56, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, H.; Euwema, M.; Van Emmerik, I.J.H. Leadership and Team Cohesiveness Across Cultures. Leadership Quarterly 2009, 20, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assen, M. Training, employee involvement and continuous improvement – the moderating effect of a common improvement method. Production Planning & Control 2021, 32, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Guenaga, J.; Iruarrizaga, J.H.; De La Mata, A.A. Initiatives for the improvement of continuous management training. 2015, 15, 61–92. [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. How leaders influence organizational effectiveness. Leadership Quarterly 2008, 19, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, S. Advancing research on team process dynamics. Organizational Psychology Review 2015, 5, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coury, B.; Terranova, M. Collaborative Decision Making in Dynamic Systems. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 1991, 35, 944–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J. Team Coordination and Dynamics. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2014, 23, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-C. Team decision theory and information structures. Proceedings of the IEEE 1980, 68, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, D. Coordination in Human Teams: Theories, Data and Models. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 1990, 23, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S. Decision-Making Groups and Teams: An Information Exchange Perspective. 2013. [CrossRef]

- De Jong, B.; Dirks, K.; Gillespie, N. Trust and team performance: A meta-analysis of main effects, moderators, and covariates. The Journal of applied psychology 2016, 101 8, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boies, K.; Fiset, J.; Gill, H. Communication and trust are key: Unlocking the relationship between leadership and team performance and creativity. Leadership Quarterly 2015, 26, 1080–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaro, S.; McCoy, M. The Effects of Task and Interpersonal Cohesiveness on Performance of a Disjunctive Group Task1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 1988, 18, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakal, T.; Mampilly, D.S.R. The Impact of Interpersonal Trust on Group Cohesion: An empirical attestation among Scientists in R&D organizations. IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences 2016, 3, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. The Power of Play. American Journal of Health Promotion 2020, 34, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghel, I.; Salanova, M.; Martínez, I. Feeling Good Makes Us Stronger: How Team Resilience Mediates the Effect of Positive Emotions on Team Performance. Journal of Happiness Studies 2016, 17, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez, I.; Gómez, H.; Laulié, L.; González, V. Project team resilience: The effect of group potency and interpersonal trust. International Journal of Project Management 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Friedman, Y.; Tishler, A. Cultivating a resilient top management team: The importance of relational connections and strategic decision comprehensiveness. Safety Science 2013, 51, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, A.; Clarke, S.; Johnson, S.; Willis, S. Workplace team resilience: A systematic review and conceptual development. Organizational Psychology Review 2020, 10, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggart, L.; Ward, E.; Cook, L.; Schofield, G. The team as a secure base: Promoting resilience and competence in child and family social work. Children and Youth Services Review 2017, 83, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwatny, H.; Miu-Miller, K. Power System Dynamics and Control. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Simeonova, B.; Galliers, R.; Karanasios, S. Power dynamics in organisations and the role of information systems. Information Systems Journal 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocar, W. Adaptive Leadership in the Military Decision Making Process. Military review 2012, 91, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Derue, D. Adaptive leadership theory: Leading and following as a complex adaptive process. Research in Organizational Behavior 2011, 31, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallillin, L. Adaptive Theory Approach In Leadership. International Journal of Asian Education 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.; Murthy, A. Adaptive leadership responses. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 2014, 10, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygeson, M.; Morrissey, L.; Ulstad, V. Adaptive leadership and the practice of medicine: a complexity-based approach to reframing the doctor-patient relationship. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice 2010, 16 5, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.; Shapiro, D.; Lu, S.; McGurrin, D. Culture and teams. Current opinion in psychology 2016, 8, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, S.; Majeed, N. Relationship between team culture and team performance through lens of knowledge sharing and team emotional intelligence. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driskell, T.; Salas, E.; Driskell, J. Teams in extreme environments: Alterations in team development and teamwork. Human Resource Management Review 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, N. Coping with coping strategies: how distributed teams and their members deal with the stress of distance, time zones and culture. Stress and health : journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress 2011, 27 2, 123-143. [CrossRef]

- Serfaty, D.; Entin, E.; Volpe, C. Adaptation to Stress in Team Decision-Making and Coordination. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 1993, 37, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdahl, M.; Undorf, M. Hindsight bias in metamemory: outcome knowledge influences the recollection of judgments of learning. Memory 2021, 29, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen-Szalanski, J.; Willham, C. The hindsight bias: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 48, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, G. Synergetic effects in working teams. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2011, 26, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.R.; Vega-Díaz, M.; González-García, H. Team Cohesion Profiles: Influence on the Development of Mental Skills and Stress Management. Journal of sports science & medicine 2023, 22 4, 637-644. [CrossRef]

- Pilny, A.; Dobosh, M.; Yahja, A.; Poole, M.; Campbell, A.; Ruge-Jones, L.; Proulx, J. Team Coordination in Uncertain Environments: The Role of Processual Communication Networks. Human Communication Research 2020, 46, 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Context Units | Description / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Resource optimization | Efficient use of personnel, time, and equipment to enhance operational outcomes |

| Corresponding prerequisites | Necessary conditions or factors that enable effective risk management and decision-making |

| Information advantage, increased attention | Improved situational awareness through better access to intelligence and heightened focus |

| Provides more safety, security, safety risk | Measures and actions that enhance safety but also potential risks in security operations |

| Sharpens risk perception, risk management, calculated risk | The ability to accurately assess threats and make informed decisions under pressure |

| Blind trust | Uncritical reliance on team members, procedures, or leadership, which can be a risk factor |

| Through training, automatism, professionalism | The impact of training in developing automatic responses, improving performance, and professionalism |

| Own risk, personal burden, perception leads to uncertainty | The psychological impact of risk exposure on individuals, leading to stress or hesitation |

| Error susceptibility | Factors that increase the likelihood of operational mistakes or misjudgments. |

| Danger, hazard | External threats and hazards encountered in high-risk operations |

| Self-awareness, self-confidence, self-assurance, self-reflection, recognition of one's abilities, own knowledge/skills | The role of personal development, confidence, and reflection in improving performance |

| Quality improvement, success, post-operation review | The importance of evaluating past actions to enhance future operational effectiveness |

| Categories | Description/Explanation | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Drill training | This category refers to intensive, standardized training methods aimed at developing automatisms in stressful situations. It examines how drill training contributes to risk reduction and improving responsiveness during operations. | 75 |

| Coordination | This category includes the ability to effectively collaborate between operational forces and units. Good coordination can help minimize risks and enhance efficiency in ad-hoc operations. | 75 |

| Success | Success is viewed here as a measure of the outcome of operations. The analysis of the expert interviews aims to reveal which factors are crucial for a successful operation and how success is defined. | 63 |

| Safety | This category examines how safety is perceived and ensured, both for operational forces and third parties. Balancing safety measures and operational risks plays a central role here. | 167 |

| Risk | This category differentiates between specific risks that may arise during an operation and how they are categorized (e.g., physical, psychological, or organizational risks). | 55 |

| Information | The "Information" category analyzes access to and availability of operation-relevant information. Clear and timely information sharing is critical to minimizing risks and successfully carrying out operations. | 16 |

| Focus | This category addresses how operational forces can maintain focus in stressful and dynamic situations and the role training plays in this. | 3 |

| Perception | This category examines how operational forces perceive risks and threats. It includes subjective assessments of danger and uncertainty in operations. | 35 |

| Error culture | This category deals with the handling of mistakes in the operational context. An open approach to errors can improve operational strategies and further develop training units. | 19 |

| Risk avoidance | Risk avoidance is a key element of operational planning. This category addresses strategies aimed at minimizing risks in advance. | 55 |

| Personal burden | This category focuses on the psychological and physical burden on operational forces during missions. It analyzes how these burdens are perceived and processed. | 12 |

| Operations | This category encompasses general operational experiences described in the interviews and serves as a reference framework for the other categories. | 27 |

| Risk perception | This category specifically investigates how operational forces assess risks and what mechanisms they use to anticipate and manage them. | 21 |

| Self-reflection | This category refers to the ability of operational forces to critically reflect on their actions and decisions after a mission and learn from them. | 39 |

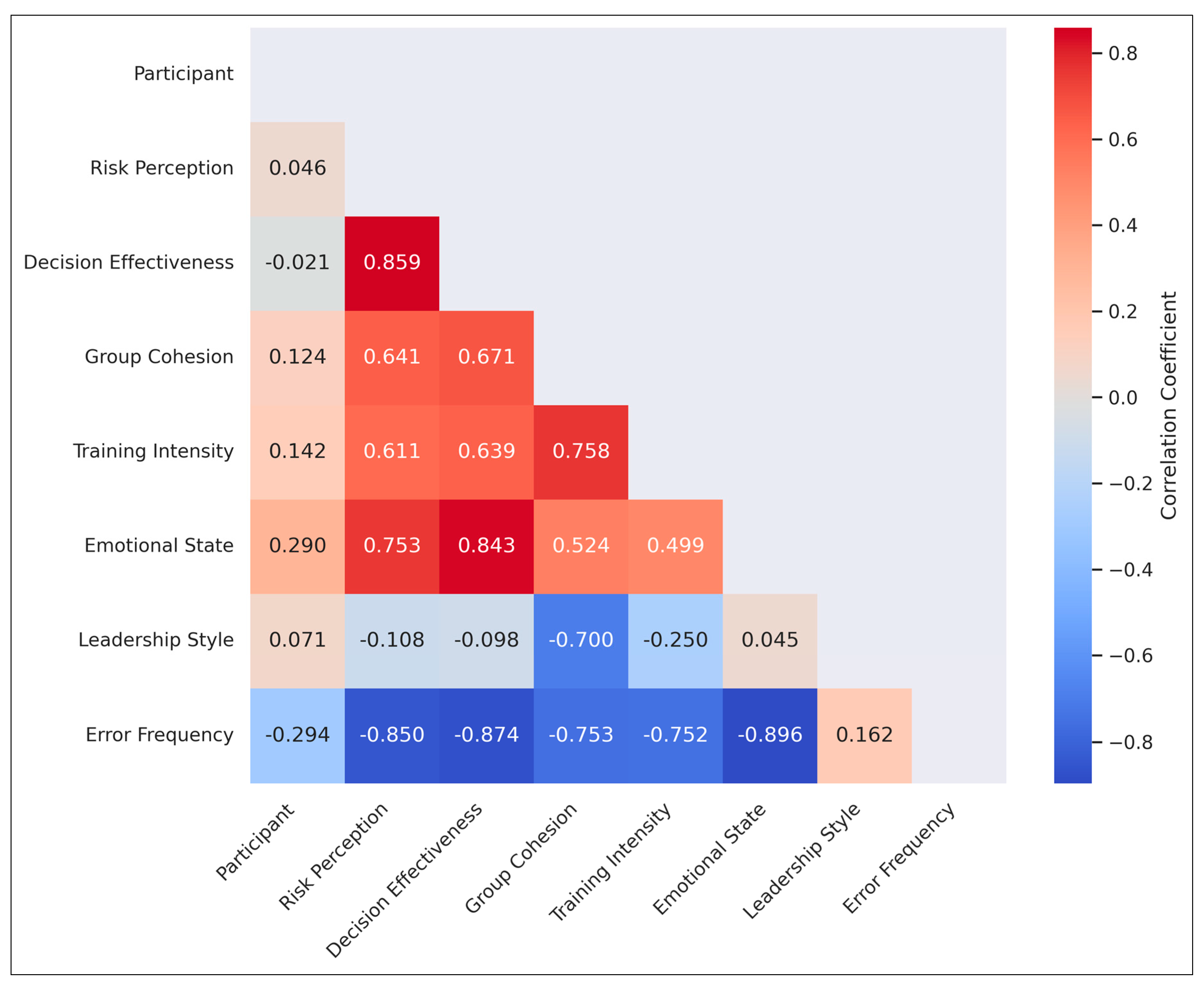

| Variable | Participant | Risk perception | Decision effectiveness | Group cohesion | Training intensity | Emotional state | Leadership style | Error frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | 1.0 | |||||||

| Risk perception | 0.046 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Decision effectiveness | ‒0.021 | 0.859** | 1.0 | |||||

| Group cohesion | 0.124 | 0.641* | 0.671* | 1.0 | ||||

| Training intensity | 0.142 | 0.611 | 0.639* | 0.758* | 1.0 | |||

| Emotional state | 0.290 | 0.753* | 0.843** | 0.524 | 0.499 | 1.0 | ||

| Leadership style | 0.071 | ‒0.108 | ‒0.098 | ‒0.700* | ‒0.250 | 0.045 | 1.0 | |

| Error frequency | ‒0.294 | ‒0.850** | ‒0.874** | ‒0.753* | ‒0.752* | ‒0.896** | 0.162 | 1.0 |

| Participant | Risk Perception (1-5) |

Decision Effectiveness (1-5) |

Group Cohesion (1-5) |

Training Intensity (1-5) | Emotional State (1-5) | Leadership Style (1=Hierarchical, 2=Participative) | Error Frequency (1-5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 10 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Participant ID | Communication and interaction |

Interpersonal attraction and cohesion |

Social integration and influence |

Power and control |

Group culture |

Key Thematic Terms | Frequency of Theme (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Open and direct communication facilitated quick decision-making. | Strong bonds among members fostered trust and cooperation. | Integration of new members was smooth and supportive. | Leadership was flexible and adapted to the situation. | Shared values and goals unified the team. | Communication, trust, clarity | 80 |

| 2 | Occasional miscommunication highlighted areas for improvement. | Cohesion varied based on operational demands. | Experienced members influenced group decisions effectively. | Hierarchical structures were evident but not rigid. | Cultural norms emphasized mutual respect and dedication. | Cohesion, camaraderie, emotional bonds | 75 |

| 3 | Frequent updates and real-time feedback enhanced coordination. | Mutual respect strengthened emotional bonds. | Recruits quickly adapted to group norms. | Power dynamics allowed for collaborative decision-making. | Beliefs about teamwork guided behavior and interactions. | Integration, influence, group dynamics | 70 |

| 4 | Structured communication protocols ensured clarity and focus. | Shared experiences enhanced team cohesion. | Integration efforts focused on balancing old and new dynamics. | Egalitarian approaches enhanced group cohesion. | Traditions and rituals reinforced a sense of belonging. | Leadership, flexibility, power balance | 85 |

| 5 | Ad hoc communication sufficed for routine operations. | Stable relationships provided a foundation for collaboration. | Influence was distributed based on expertise and roles. | Control was centralized during critical operations. | Shared norms supported consistent performance. | Culture, norms, shared values | 90 |

| 6 | Proactive communication minimized misunderstandings. | Occasional friction was resolved through team-building activities. | Group members inspired and motivated each other. | Leadership balanced authority with team input. | Team culture prioritized adaptability and innovation. | Teamwork, adaptability, inclusivity | 65 |

| 7 | Dynamic interaction enabled seamless task execution. | High levels of camaraderie improved morale. | Social influence shapes decision-making and strategy. | Power dynamics shifted based on operational needs. | Cultural values inspired collective accountability. | Group cohesion, operational success, respect | 70 |

| 8 | Occasional gaps in communication required immediate resolution. | Team cohesion was essential for handling stressful scenarios. | Integration challenges were resolved through training. | Hierarchical control was softened by trust in leadership. | Norms encouraged proactive problem-solving. | Resilience, shared goals, camaraderie | 80 |

| 9 | Clear communication reduced operational errors. | Emotional bonds were reinforced through shared successes. | Newcomers brought fresh perspectives, enriching group dynamics. | Command authority was respected but adaptable. | Shared behaviors promoted resilience under stress. | Team dynamics, efficiency, coordination | 60 |

| 10 | Consistent information sharing improved group efficiency. | Strong interpersonal connections ensured group stability. | Shared goals ensured the seamless integration of members. | Leadership effectively balanced power and inclusivity. | Cultural cohesion ensured a strong sense of identity. | Trust, collaboration, shared identity | 85 |

| Theme | Polarity | Subjectivity | Keyword Frequency | Sentiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication and Interaction | 0.115 | 0.49 | 36 | Positive |

| Interpersonal Attraction and Cohesion | 0.111 | 0.483 | 17 | Positive |

| Social Integration and Influence | 0.113 | 0.48 | 11 | Positive |

| Power and Control | 0.116 | 0.485 | 102 | Positive |

| Group Culture | 0.106 | 0.48 | 14 | Positive |

| Participant ID | How risky was the situation? | Emotional state at the time? | How likely was it that things could have gone wrong? | What could have happened? | Would you have revised decisions? | Things that should have been noticed? | Different assessment of dangers? | Key Thematic Terms | Frequency of Theme (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | High risk due to the presence of armed suspects and potential for violence. | Focused, with adrenaline heightening awareness. | Very likely due to unpredictable adversaries. | Severe injury or loss of life. | Yes, would have adjusted response times. | Details about adversary behavior. | Yes, dangers were underestimated initially. | High risk, armed suspects, unpredictability | 75 |

| 2 | Moderate to high risk depending on situational dynamics and uncertainty. | Anxious but controlled; a mix of fear and determination. | Somewhat likely depending on the decisions made. | Operational failure leading to mission compromise. | Partially; some tactics could have been improved. | Better environmental awareness. | Possibly; more cautious approach needed. | Moderate to high risk, situational dynamics, uncertainty | 60 |

| 3 | Very risky, especially due to the potential for unforeseen events. | Calm but alert; readiness to adapt was key. | High probability if coordination failed. | Unexpected escalation causing casualties. | No significant changes but would refine preparation. | Missed early warning signs. | No, assessment was appropriate. | Unforeseen events, complex scenarios, adaptability | 55 |

| 4 | Risk level varied, but high stakes were involved in specific operations. | Heightened focus, combined with moments of stress. | Moderate likelihood due to high complexity. | Loss of control and failure to neutralize the threat. | Yes, would prioritize better situational awareness. | Improved focus on small details. | Yes, some risks seemed smaller than they were. | High stakes, operational strategies, critical response | 70 |

| 5 | Risk was perceived as manageable but could escalate quickly. | Confident due to training, though occasional doubt arose. | Low likelihood with proper execution, but potential was present. | Miscalculations could have led to injury. | No, confident in decisions made at the time. | Yes, certain team dynamics were overlooked. | No, perception aligned with outcomes. | Manageable risks, potential escalation, preparation | 65 |

| 6 | High risk, particularly in scenarios involving explosives or armed adversaries. | Determined and emotionally invested in the outcome. | Moderate to high, especially in chaotic environments. | Potential for explosions or armed conflict. | Yes, focus on alternative approaches to mitigate risk. | Yes, unnoticed environmental factors. | Partially; more emphasis on long-term risks. | Explosives, armed conflict, chaotic environments | 80 |

| 7 | Risk was mitigated through training, but some operations were inherently dangerous. | Steady, but emotional tension was evident in team dynamics. | Low probability due to structured protocols. | Missteps could have endangered team safety. | Some adjustments to communication protocols. | Minor, mostly related to operational flow. | Yes, in hindsight, risks were misjudged. | Structured protocols, mitigated risks, team safety | 50 |

| 8 | High risk in emotionally charged scenarios, such as hostage situations. | Nervous initially, but focus improved as the situation evolved. | Significant risk without strong leadership and teamwork. | Hostage harm or operational delays. | Would refine coordination methods. | Would monitor subtle changes more closely. | Possibly; risk levels shifted during execution. | Emotionally charged, hostage scenarios, leadership | 85 |

| 9 | Moderate risk with a focus on minimizing adverse outcomes. | Mixed emotions; pride in execution but some hesitation. | Moderate likelihood due to external factors. | Negative outcomes due to overlooked risks. | Possibly; reconsider key choices. | Yes, missed cues during execution. | No, generally aligned well with actual risks. | External factors, overlooked risks, pressure | 40 |

| 10 | Risk varied; often underestimated initially but escalated in complex scenarios. | Composed, with a strong reliance on preparation. | Uncertain; depended on the team’s adaptability. | The worsened situation with potential fatalities. | Yes, especially in high-pressure moments. | Could have foreseen certain risks. | Yes, would reassess initial danger levels. | Complex scenarios, underestimated risks, adaptability | 60 |

| Theme | Polarity | Subjectivity | Keyword Frequency |

Sentiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How risky was the situation? | 0.126 | 0.486 | 6 | Positive |

| Emotional state at the time? | 0.107 | 0.481 | 36 | Positive |

| How likely was it that things could have gone wrong? | 0.108 | 0.489 | 14 | Positive |

| What could have happened? | 0.123 | 0.483 | 5 | Positive |

| Would you have revised decisions? | 0.113 | 0.482 | 27 | Positive |

| Things that should have been noticed? | 0.113 | 0.477 | 25 | Positive |

| Different assessment of dangers? | 0.106 | 0.478 | 22 | Positive |

| Participant ID | Teamwork within the group | Communication handling |

Decision-making (How and by whom) | Emotions within the group | Situation management | Could only group handle critical situations? | Key Thematic Terms | Frequency of Theme (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Trust among team members was critical in achieving objectives. | Clear and concise communication was maintained throughout operations. | Collective decision-making with input from all team members. | Fear and stress were mitigated through mutual support. | Situations were managed effectively through structured protocols. | Yes, group effort was essential to overcome challenges. | Trust, collaboration, mutual support | 80 |

| 2 | Coordination challenges emerged during high-pressure scenarios. | Breakdowns in communication occasionally disrupted coordination. | Commander-led decisions dominated in most operations. | Anxiety was prevalent but managed through focus on objectives. | Management was reactive but adapted to changing conditions. | Group coordination was necessary for successful outcomes. | Coordination, situational adaptability, communication | 70 |

| 3 | Team cohesion enabled effective responses to unexpected challenges. | Open channels allowed for rapid information exchange. | Combination of hierarchical and collaborative decision-making. | Camaraderie helped alleviate emotional tension among members. | Team collaboration played a central role in managing operations. | Individual efforts alone would not have sufficed; teamwork was crucial. | Cohesion, hierarchical and collaborative decision-making | 75 |

| 4 | Collaborative effort ensured better decision-making in critical situations. | Structured communication protocols guided actions effectively. | Key decisions were guided by the commander but informed by team input. | Confidence in leadership reduced uncertainty and worry. | Challenges were addressed promptly through effective planning. | Critical scenarios required the collective expertise of the group. | Leadership, emotional stability, camaraderie | 85 |

| 5 | Teamwork was stable but relied heavily on individual contributions. | Ad hoc communication was sufficient for most situations. | Reactive decision-making depending on the context of the operation. | Emotions remained stable due to preparedness and training. | Ad hoc adjustments ensured smooth resolution of issues. | Group input ensured a balanced approach to complex situations. | Structured protocols, innovative management, team efforts | 65 |

| 6 | Effective teamwork minimized risks and ensured smooth operations. | Proactive communication ensured alignment during complex tasks. | Final decisions rested with the commander, with team suggestions considered. | Occasional frustration was addressed through open dialogue. | Standardized approaches streamlined management efforts. | Yes, the group dynamic enabled effective risk mitigation. | Group dynamics, collective expertise, risk mitigation | 90 |

| 7 | Group synergy was essential for addressing high-risk tasks. | Real-time updates were crucial in dynamic scenarios. | Decisions alternated between hierarchical and collaborative approaches. | Group solidarity eased emotional burdens during operations. | Innovative strategies were employed to handle unique scenarios. | Individual skills complemented the collective strength of the team. | Collaboration, trust, proactive communication | 70 |

| 8 | Strong team collaboration improved operational outcomes. | Brief but focused communication minimized delays. | Hierarchical decision-making prevailed in critical moments. | Initial nervousness gave way to focus as tasks progressed. | Situations were resolved through decisive and coordinated actions. | Group cohesion was vital in achieving operational success. | Team cohesion, operational success, leadership input | 85 |

| 9 | Occasional conflicts arose but were resolved promptly. | Occasional miscommunication highlighted the need for clarity. | Group discussions informed the decision-making process. | Tension arose during conflicts but was quickly resolved. | Management relied heavily on leadership and team cooperation. | Without group support, operations would have been significantly harder. | Adaptability, group effort, conflict resolution | 60 |

| 10 | The high degree of trust among team members facilitated operations. | Consistent communication reduced errors and misunderstandings. | Pre-planned strategies were adapted to situational needs. | Pride in collective achievement outweighed initial fears. | Proactive strategies minimized operational disruptions. | Yes, collaborative effort ensured better management of critical tasks. | Strategic management, collective problem-solving, confidence | 80 |

| Theme | Polarity | Subjectivity | Keyword Frequency | Sentiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork within the group | 0.165 | 0.535 | 15 | Positive |

| Communication handling | 0.105 | 0.510 | 12 | Positive |

| Decision-making (How and by whom) | 0.085 | 0.521 | 11 | Positive |

| Emotions within the group | 0.142 | 0.505 | 13 | Positive |

| Situation management | 0.127 | 0.514 | 14 | Positive |

| Could only a group handle critical situations? | 0.152 | 0.520 | 12 | Positive |

| Teamwork within the group | 0.165 | 0.535 | 15 | Positive |

| Participant ID | New/old colleagues impact | Changes in the group | Role of close contact |

Role of hierarchy |

Command during operations |

Responsibility for failure |

Need for recognition | Joining group criteria | Group vulnerabilities/strengths |

Rituals after operations |

Key Thematic Terms |

Frequency of Theme (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adapted well to changes; new members brought fresh perspectives. | Improved communication and collaboration with new members. | Close bonds fostered a sense of security during operations. | The hierarchy was respected but allowed flexibility in execution. | The commander made key decisions, with input from the group. | Commander bore ultimate responsibility for failures. | Recognition was valued but not actively sought. | Selection based on physical and mental aptitude tests. | Strength in collaboration; vulnerability in skill disparities. | Debriefings and informal gatherings fostered team bonding. | Adaptation, team cohesion, perspective shifts | 70 |

| 2 | Transition periods caused minor disruptions but were manageable. | Internal relations were strained during transitional phases. | Physical proximity helped ensure quick responses in emergencies. | Clear authority lines ensured smoother decision-making. | Command decisions were central but included team suggestions. | Shared responsibility between leadership and the team. | Acknowledgement of contributions motivated team members. | Criteria included specific skills and compatibility with the team. | Resilience depended on leadership and group cohesion. | Rituals included reflection sessions to process experiences. | Transition challenges, training needs, internal relations | 65 |

| 3 | Experienced initial challenges with new members but overcame them. | Required more intensive training for recruits. | Team safety improved through constant communication. | Subordinate-superior dynamics impacted morale positively. | Group decisions were occasionally made collectively. | Accountability rested with specific roles within the hierarchy. | Felt the need to assert individuality within the group. | Customary processes ensured a balanced team composition. | Strength in adaptability; vulnerability in communication gaps. | Post-operation discussions helped identify lessons learned. | Safety, trust, collaboration | 85 |

| 4 | Departure of experienced colleagues created temporary skill gaps. | Disruptive factors included differences in working styles. | Close relationships reduced misunderstandings under stress. | Hierarchy was more pronounced during critical operations. | Hierarchy dominated command, especially in critical moments. | Responsibility was situational, depending on decision origin. | Recognition was indirectly important for morale. | Joining required approval from leadership and peers. | Collaboration minimized operational risks effectively. | Informal traditions strengthened morale after missions. | Hierarchy, flexibility, social integration | 80 |

| 5 | New additions strengthened the group’s expertise over time. | Improved interaction led to stronger group cohesion. | Safety was enhanced by trust built through interaction. | Flexibility within hierarchical roles facilitated adaptability. | Decisions were largely centralized under commander’s control. | Failures were addressed collectively to improve future efforts. | Personal efforts were acknowledged during debriefings. | Selection focused on expertise and adaptability. | Vulnerability in overreliance on specific roles or individuals. | Rituals focused on acknowledging contributions and achievements. | Leadership, control, decision-making | 75 |

| 6 | Changes in membership occasionally disrupted cohesion. | Commander’s adaptability was tested during transitions. | Proximity and interaction contributed to collective awareness. | Commander’s leadership style influenced team confidence. | Balanced approach between command authority and team input. | Commander was primarily accountable but included team input. | Recognition fostered stronger team cohesion. | Criteria included teamwork abilities and operational experience. | Strength in mutual trust; vulnerability in untested strategies. | Post-mission reviews ensured continuous improvement. | Responsibility, accountability, task allocation | 70 |

| 7 | Welcomed new members but required adjustments in team dynamics. | Enhanced training efforts to integrate new members. | Familiarity with team members improved risk management. | Clear roles reduced confusion and enhanced efficiency. | Command decisions adapted to operational demands. | Responsibility was distributed based on task allocation. | Valued recognition as an indicator of trust and competence. | Joining was determined by demonstrated capability under stress. | Team strength was its diversity; vulnerability was coordination. | Celebratory rituals enhanced team cohesion and morale. | Recognition, motivation, team morale | 60 |

| 8 | The departure of long-term colleagues affected morale. | Internal dynamics shifted, requiring renegotiation of roles. | Safety relied heavily on mutual understanding and collaboration. | The hierarchy was balanced with collaborative input from the team. | Command rested firmly with leadership figures. | Leadership took primary responsibility, shielding the team. | Acknowledgement contributed to personal and team motivation. | Group entry was based on shared values and mission alignment. | Strength in experience; vulnerability in handling new challenges. | Structured reflections allowed the processing of high-stress events. | Criteria, selection, compatibility | 75 |

| 9 | New members revitalized the group’s motivation. | Changes brought opportunities for innovation and learning. | Frequent interaction strengthened situational awareness. | Leadership was firm but adaptable to situational needs. | Group input informed decisions led by the commander. | Accountability was transparent, promoting trust in leadership. | Recognition improved self-esteem and operational engagement. | Customary approval processes ensured seamless integration. | Resilience was built through training; vulnerability in morale dips. | Debriefings balanced operational feedback with emotional support. | Resilience, vulnerabilities, operational strengths | 85 |

| 10 | The departure of key figures prompted a reevaluation of roles. | Increased focus on bridging generational gaps in the team. | Close contact was vital for maintaining operational efficiency. | Hierarchy strengthened coordination during high-stress scenarios. | Collective decisions were rare but effective when implemented. | Failures were analyzed collectively, with leadership oversight. | Individual efforts were occasionally overlooked in group dynamics. | Selection emphasized trustworthiness and competence. | Strength in trust; vulnerability in high turnover rates. | Post-operation rituals included both formal and informal components. | Rituals, reflection, team bonding | 90 |

| Theme | Polarity | Subjectivity | Keyword Frequency |

Sentiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New/old colleagues impact | 0.12 | 0.52 | 14 | Positive |

| Changes in the group | 0.11 | 0.51 | 13 | Positive |

| Role of close contact | 0.13 | 0.525 | 12 | Positive |

| Role of hierarchy | 0.115 | 0.515 | 11 | Balanced |

| Command during operations | 0.125 | 0.53 | 13 | Positive |

| Responsibility for failure | 0.118 | 0.518 | 12 | Positive |

| Need for recognition | 0.127 | 0.528 | 12 | Positive |

| Joining group criteria | 0.121 | 0.522 | 11 | Positive |

| Group vulnerabilities/strengths | 0.113 | 0.517 | 10 | Balanced |

| Rituals after operations | 0.122 | 0.523 | 13 | Positive |

| Dimension | Observations | Recommendations | Rationale | Responsible Parties | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training & Preparation | Intensive scenario-based training significantly improves situational awareness and safety. | Enhance scenario-based training with diverse operational challenges, emphasizing cognitive, physical, and emotional readiness. | Builds resilience and reduces errors during high-stress events. | Training Department | Short-term |

| Communication Protocols | Clear communication minimizes errors, but gaps were noted in high-pressure scenarios. | Standardize communication protocols with clear hierarchies and real-time feedback systems to address gaps during critical operations. | Reduces miscommunication and improves decision-making speed. | Operations Team, IT Support | Medium-term |

| Risk Perception | Overestimation of abilities and insufficient situational data led to vulnerabilities. | Integrate dynamic risk assessment frameworks and decision-support tools to improve real-time judgment and mitigate overconfidence. | Enhances judgment under uncertainty and mitigates risks. | Risk Management Team | Long-term |

| Leadership Dynamics | Flexible leadership adapted to situational needs proved effective. | Train leaders in adaptive decision-making, balancing authority with team input to foster a collaborative yet controlled response. | Promotes teamwork while maintaining control in dynamic scenarios. | Leadership Development Unit | Medium-term |

| Group Dynamics | Cohesion and mutual trust were pivotal for operational success. | Conduct team-building exercises and simulations that strengthen trust, reduce conflicts, and improve group adaptability. | Enhances collaboration and operational efficiency. | HR Department | Short-term |

| Equipment & Resources | Inadequate tools and delayed information sharing posed risks. | Ensure access to advanced tools and real-time data-sharing platforms tailored for various operational contexts. | Improves operational effectiveness and reduces delays. | Logistics and IT Departments | Short-term |

| Error Management | Mistakes in training provided valuable lessons for real scenarios. | Establish routine post-operation debriefs and integrate 'lessons learned' into future operational planning and training. | Encourages continuous improvement and adaptability. | Training Department, Team Leads | Medium-term |

| Emotional Resilience | Emotional tension varied but was mitigated through camaraderie and preparation. | Incorporate stress-management workshops and peer support programs to strengthen emotional resilience in high-stress environments. | Reduces burnout and improves focus during crises. | HR Department | Medium-term |

| Cultural Norms | Mutual respect and shared values strengthened team collaboration. | Promote cultural awareness training to enhance mutual respect and align diverse team members with organizational goals. | Improves inclusivity and reduces cultural misunderstandings. | Training Department | Short-term |

| Operational Efficiency | Structured protocols improved performance but lacked adaptability in unique scenarios. | Introduce flexible operational guidelines that allow deviations based on situational demands while maintaining core standards. | Balances consistency with the need for adaptability. | Operations Team | Medium-term |

| Adaptability | High adaptability enabled teams to handle unpredictable changes effectively. | Foster innovation through cross-training and simulations of unplanned disruptions to enhance overall team agility. | Prepares teams for unexpected challenges. | Training Department, Leadership | Long-term |

| Safety Protocols | Safety risks were mitigated but required continuous evaluation. | Regularly update safety protocols based on evolving risks, including the integration of new technologies and environmental considerations. | Ensures up-to-date practices that minimize risks. | Safety Management Team | Long-term |

| Integration of New Members | Smooth onboarding facilitated team cohesion and operational stability. | Design structured onboarding programs with mentorship systems to quickly integrate new members into team dynamics and culture. | Speeds up new member adaptation and strengthens team cohesion. | HR Department | Short-term |

| Conflict Resolution | Occasional conflicts were resolved through mutual understanding and leadership mediation. | Develop conflict-resolution training for leaders and teams to ensure quick and effective resolution without disrupting operations. | Minimizes disruptions and strengthens team dynamics. | HR Department, Team Leads | Medium-term |

| Performance Monitoring | Real-time updates improved coordination but required effort for consistency. | Utilize digital performance monitoring tools to track team effectiveness and highlight areas for immediate improvement. | Identifies areas for operational and individual improvement. | Operations Team, IT Support | Short-term |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).