1. Introduction

In today’s industrial environment, many companies operate under unpredictable conditions. These working conditions may include changes in work hours, fluctuating workloads, irregular environments, and safety issues that arise due to the complexity of the facility or organisation. According to Green (2022), the increasing intensity of work has also been studied in recent years [

1]. Based on empirical evidence and observations, this variability frequently results in unacknowledged risks that can negatively impact employee performance and the quality of work output. Therefore, it is imperative to develop a methodology that recognises and helps identify these changing conditions, not only from a safety perspective, but also in terms of maintaining work efficiency and minimising risks in the context of the 2030 Agenda objectives.

The objective of the paper is to address the knowledge gap on unusual working conditions and to present a methodology for unusual working conditions for companies that is intended to reduce the physical and psychological burden on people working in a wide variety of fields in the context of contributing to SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth.

SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), which is part of the Sustainable Development Goals devoted to Agenda 2030, promotes decent work by ensuring that employees receive fair wages and benefits, as well as job security, in order to help achieve productive employment. The objectives and targets defined for the achievement of SDG 8 emphasise the protection of labour rights and safe working environments, which align directly with the health and safety regulations at work. By encouraging inclusive, motivating, and engaging workplaces, companies can provide stable employment, helping people transition from education to the workforce. The concept of decent work, as defined in SDG 8, also presents many challenges [

2].

Promoting mental health and managing workplace stress is crucial to improve overall worker productivity, job satisfaction, and retention. This reflects the SDG 8’s call for policies that support well-being, including digital well-being, and sustainable work environments. Improving working conditions is essential to achieve SDG 8, which aims to promote decent work, economic growth, and sustainable employment. By focussing on the physical, organisational, and social aspects of work, organisations can contribute to global efforts to foster economic growth while ensuring that all workers experience productive, safe, and fair working environments. Good working conditions, such as fair pay, enable workers to meet their needs, thereby reducing economic inequality and poverty.

This paper presents a structured, practice-oriented methodology for risk assessment and performance evaluation of work processes under Unusual Working Conditions (UWC based on the identification of gaps in theory, practical experience, and validation with analytical tools such as SWOT analysis to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. The methodology was tested and verified in an international company. through expert discussion and field observations.

Key innovations of this study are as follows:

Developing a multidimensional risk classification model applicable to unpredictable work settings;

Integrating qualitative and quantitative decision support methods to assess and prioritise occupational risks;

Formalising a process structure that allows for dynamic decision-making and continuous improvement under UWC.

This article is organised as follows:

Section 2 describes the theoretical background and conceptual framework;

Section 3 methodological framework and the applied methods;

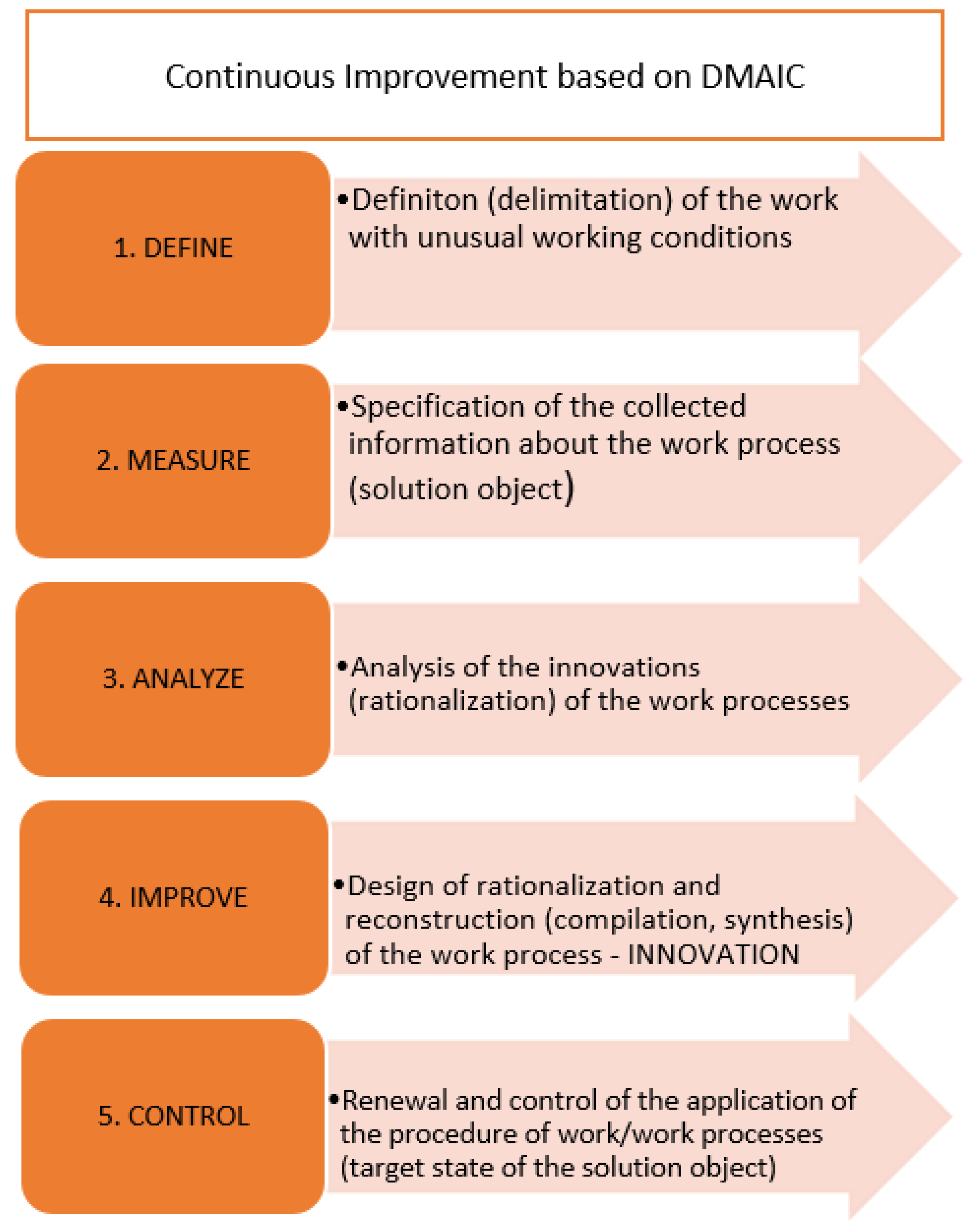

Section 4 presents the structural diagram of the methodical procedure based on the DMAIC method;;

Section 5 discusses practical implementation, limitations of study and further research.

2. Theoretical Background and Conceptual Framework

Understanding and managing occupational risks under changing and unpredictable working conditions requires an integration of classical risk assessment principles with contemporary models that account for variability, subjectivity, and complexity. This section provides a overview of methodologies in occupational risk assessment and situates them within the broader context of unusual working conditions (UWC). The review further identifies critical gaps in existing approaches, thereby justifying the need for a practice-oriented and multidimensional risk assessment framework.Risk assessment is a critical first step in evaluating work-related activities, with a focus on identifying and mitigating potential hazards.

Risk Assesment

Risk assessment is a systematic process to describe and quantifying risks associated with hazardous substances, processes, actions, or events.

Occupational risk assessment makes it possible to introduce quantitative assessment of probable damage to worker health, to identify vulnerable groups of employees, and determine the duration of service considering the exposure factors [

3].

Risk assessment is one of the necessary procedures of the health and safety management system, the authors [

3,

4] work with the traditional occupational risk assessment method, which includes compiling a list of risk factors that affect working conditions; determining the probability and damage in accordance with the classes of working conditions; calculating occupational risk on the workplace; dividing the assessment by significance based on the risk assessment scale, and developing appropriate measures to reduce the impact of risk on the workplace. The result was practically oriented method for determining occupational risk based on data from a special assessment of working conditions, which are mandatory reporting documents and characterize the actual state of working conditions in the enterprise. This procedure is suitable especially for repetitive and predictable working conditions, e.g. in an industrial enterprise.

On the other hand, the author Lasota highlights the importance of monitoring variability when assessing working conditions by Lasota [

5]. The integration of classical and modern approaches to risk assessment provides a robust foundation for analysing work processes under unusual conditions. Foundational methodologies such as those of Covello and Merkhoher [

6],Paulíkova [

7] and Stamatis [

8] are complemented by contemporary models focused on environmental and occupational health and ergonomics within sustainable CSR strategies [

9].

The most commonly used methods include qualitative risk assessment and quantitative risk assessment. Qualitative risk assessment methods rely on subjective judgments and expert opinion to assess the likelihood and consequences of risks. Techniques such as Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) are used to identify potential failure points in a system and prioritise them according to their impact and likelihood [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Event tree analysis (ETA) and Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) are examples of this approach, where probabilities of different events are calculated to model complex systems Vesely [

13]. These methods provide more precise risk assessments, but require detailed data on system behaviour and past incidents.

Hazard and Operability Study (HAZOP

) is a structured and systematic technique used to identify potential hazards and operability issues within complex industrial processes. It is particularly prevalent in high-risk sectors such as chemical manufacturing and the oil and gas industry [

14,

15]. The method involves a detailed examination of process deviations using guidewords such as ‘more’, ‘less’, or ‘as well as’ to stimulate discussion and identify possible risk scenarios [

16].

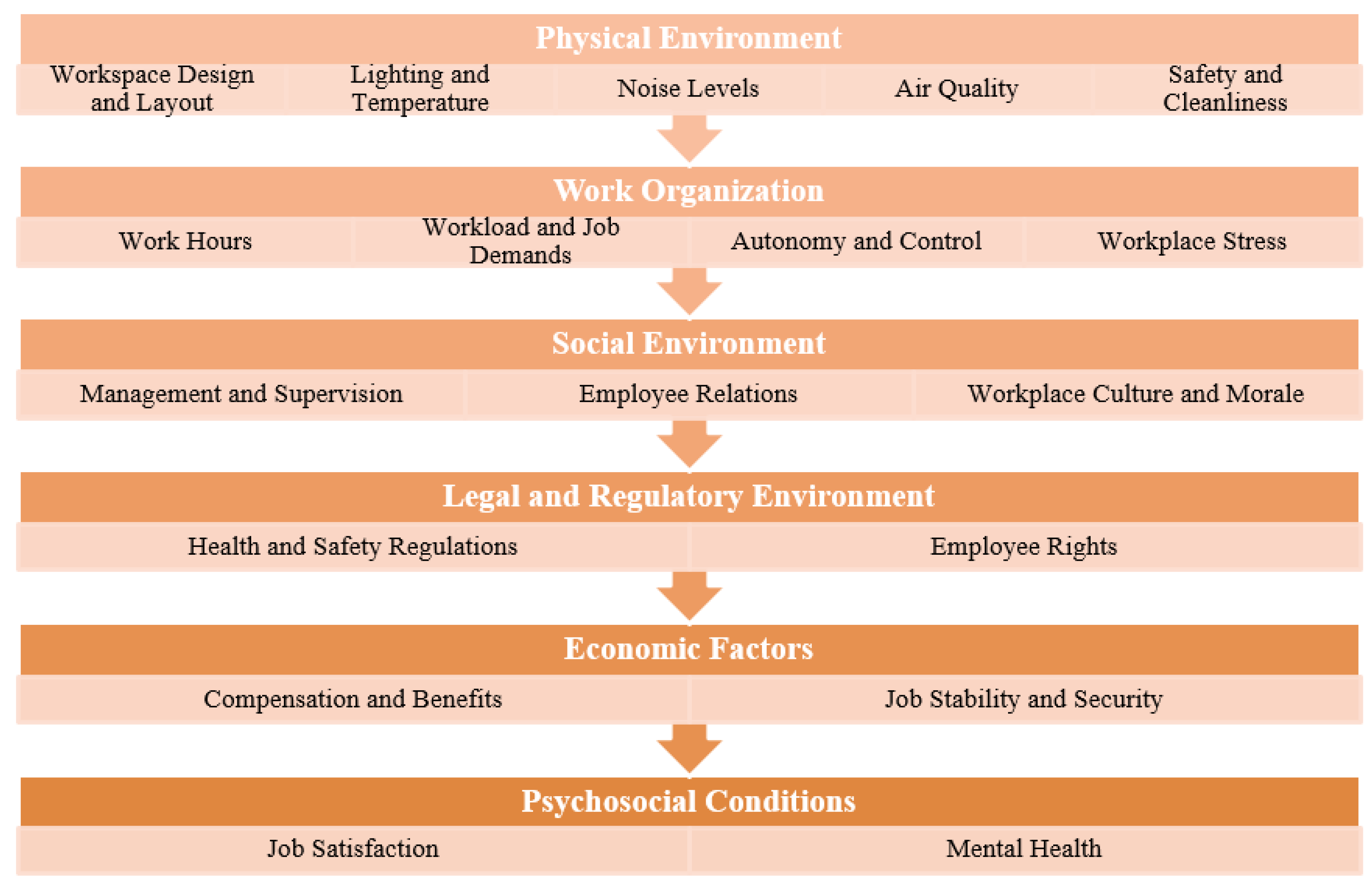

Working Conditions and Unusual Working Conditions

In general, work conditions refer to the physical, legal, social, and environmental aspects of the workplace that impact the well-being, health, and performance of employees. Working conditions in companies are shaped by a range of environmental, organizational, and psychosocial factors. The definition and scope of working conditions can vary between different industries and regions, but generally include the following six core elements of working conditions, as summarised in

Figure 1.

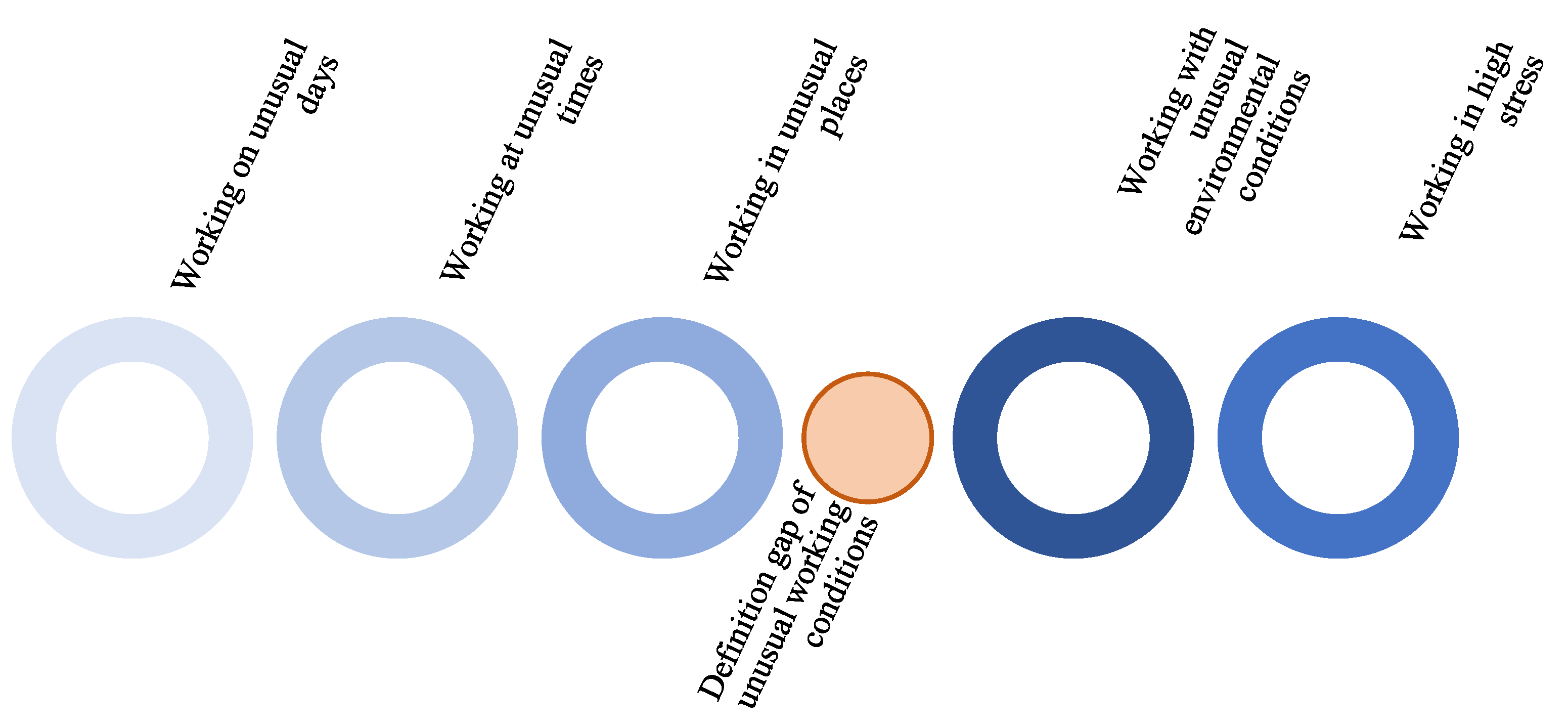

Unusual Working Conditions

Extended and atypical work hours can have a harmful effect on the body and mind. Unusual working conditions disrupt the body’s daily routine, increasing fatigue and the body’s ability to concentrate [

17].

The following symptoms of lack of energy depend on the person and their mental, emotional, and physical state. Symptoms include weariness, sleepiness, irritability, reduced alertness, lack of concentration and memory, lack of motivation, increased susceptibility to illness, depression, headache, giddiness, loss of appetite and digestive problems as shown in

Figure 2.

An analysis of factors influencing working conditions reveals that the time of day in which work is performed to be a contributing element. The nature of such roles frequently entails a wide variety of working hours, including evenings, nights, weekends, and occasionally public holidays, which can have a cumulative impact on an individual’s mental and physical well-being, as well as on their personal and professional life.

Definition of Unusual Working Conditions

Unusual working conditions are defined as those that deviate from standard, usual, or commonly expected requirements within the work environment. These factors can vary considerably in terms of location, work, health, safety, working hours, and emotional, social, and psychological aspects. Such conditions are frequently characterised by their unpredictability and tendency to change over time, resulting in instability and greater complexity in management relative to conventional working arrangements.

In this case, however, the complex theoretical definition of unusual working conditions is absent, which is defined as the coincidence of several factors. In practice, unusual working conditions frequently emerge from the interplay of multiple variables, including temporal, spatial, environmental, and psychosocial elements. The aforementioned variables are subject to further influence from the individual characteristics of the employee (eg mental stability, stress resilience), the nature of the task, and the specific context (e.g., customer expectations, construction phase, industry standards).

Consequently, although the unusual working conditions may remain constant, they are invariably associated with the individual performing the work, the customer, the construction site and the environmental conditions. Consequently, the perception of working conditions as "unusual" is not absolute, but rather context-dependent and person-specific. This understanding aligns with emerging research in sustainable human resource management (HRM) and occupational health, which emphasizes the multidimensional nature of job quality, including physical, psychosocial, and structural elements. For instance, recent studies show that long working hours, work intensification, and insufficient recovery time represent not only stressors, but also measurable health risks contributing to non-communicable diseases and burnout, directly undermining SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Gaspar et al. (2024) found that nearly half of employees reported at least one symptom of burnout, which was significantly associated with reduced quality of life. The study also identified leadership engagement, psychosocial work environment, and satisfaction with salary as protective factors [

18].

Authors McGonagle et al. (2024) emphasize that a growing number of workers are managing chronic physical and mental health conditions while working, and that work-health conflict and job insecurity are key stressors that exacerbate these conditions [

19]. These findings underscore the urgent need for dynamic, practice-oriented risk assessment methodologies that can respond to evolving work conditions and support sustainable workforce management.

Therefore, although unusual conditions may appear to be partly stable, they are inherently linked to subjective experiences, including the employee’s interpretation of the work environment and the stressors at hand. This is in line with research on job quality indicators in the context of the European Employment Strategy, which highlights that job quality is not only physical or contractual, but also psychosocial and structural (Davoine et al., 2008). [

20].

Furthermore, the dynamic, individual perception of these conditions reinforces findings in the field of sustainable human resource management and occupational health. In particular, work intensification, long working hours and slow recovery are not only stressors but also measurable risk factors for non-communicable diseases, burnout and reduced well-being (Fahey and Smyth, 2004) [

21]. . Subjective indicators such as life satisfaction and emotional distress offer additional diagnostic insight beyond traditional metrics.

Recent reviews highlight the need for adaptive safety assessment models. For example, the Mowtie method – commonly used in safety science – offers a visual and systematic way to link threats, preventive barriers and potential consequences. Although traditionally used in high-risk industries, its principles are also applicable to managing psychosocial risks in unpredictable workplaces [

22].

Furthermore, the application of multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods and their fuzzy logic variants has been shown to improve the assessment of occupational risks by incorporating uncertainty, subjectivity and input from multiple stakeholders – a particularly important strength when assessing unusual work environments (Gul, 2018). [

23].

These considerations require a context-oriented approach, where unusual working conditions are not only monitored through objective indicators, but are also interpreted in light of task-specific variables and employee adaptability. Billett and Le (2024) argue that developing adaptability is key to workforce resilience, especially in dynamic, uncertain environments where traditional competency models fail [

24].

In the proposed methodology, the existence of unusual working conditions is based on the interrelationship of spatial, temporal, psychosocial and task-related parameters

The individual’s perception of manageability in a given situation may be influenced by their personal threshold for stress. In circumstances involving numerous stressors, an individual’s response can vary significantly. While one person may find their coping mechanisms overwhelmed and unable to cope with the demands, another individual may demonstrate a higher level of resilience and ability to manage these stressors effectively.

In the proposed methodology, the existence of unusual working conditions is predicated on a direct relationship between the aforementioned parameters. This suggests that, under typical circumstances, factors such as day and time are of negligible significance as the discussion pertains to ordinary times and days. The working day is characterised by a flexible approach, with employees able to work during a variety of hours, including weekends and public holidays.

However, it is possible from practical experience that a person with a sensitive disposition may perceive noise, dust, customers, and a workplace that is less than 100% optimal (e.g., shell construction, workshop in continuous operation, etc.) as critical and difficult to achieve. For a less sensitive individual, these environmental conditions may present a slightly greater challenge, but there is no reason to perceive them as critical.

Figure 3 identifies critical gaps in the current understanding of UWC. This gap motivated the development of a multidimensional risk assessment methodology.

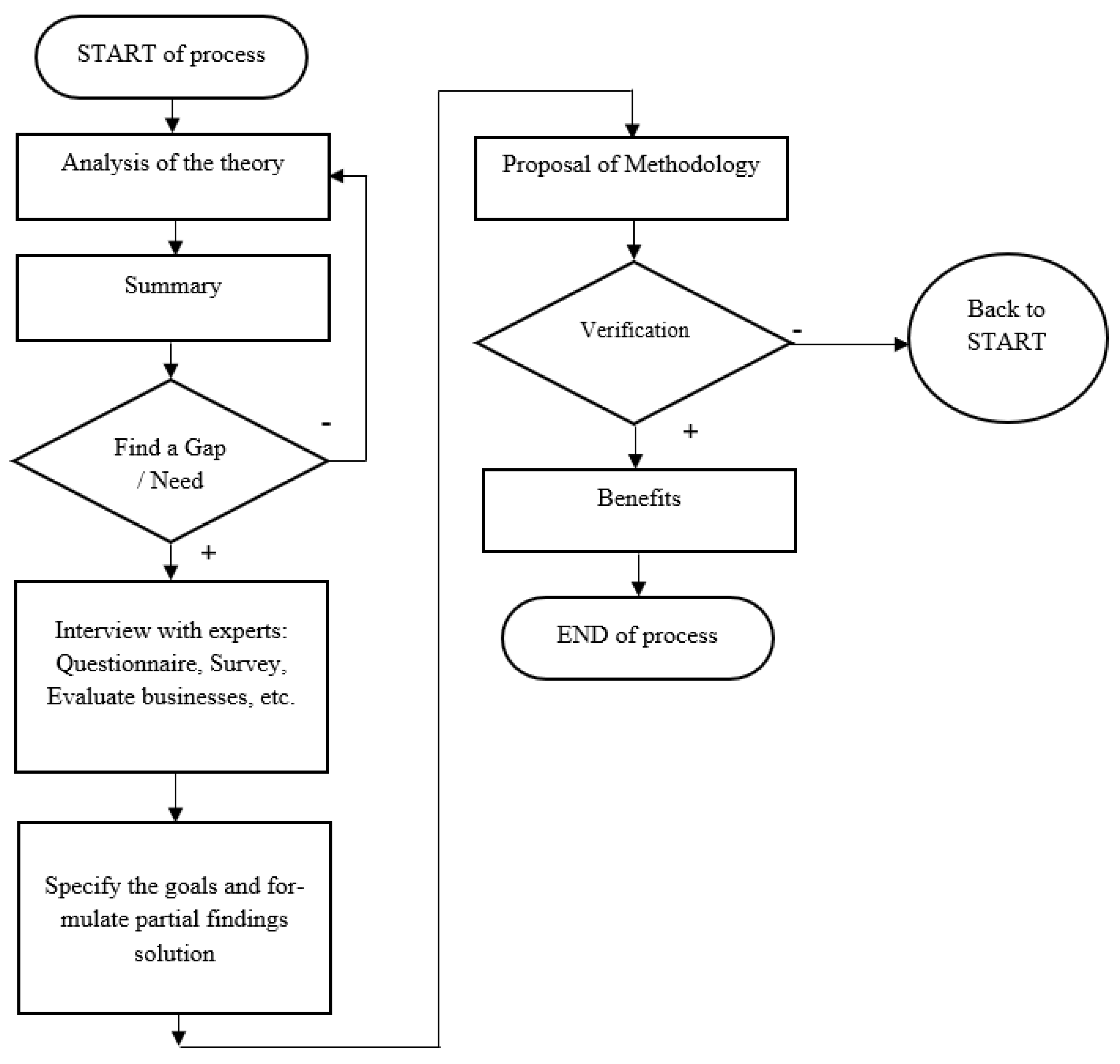

3. Materials and Methods

To proceed with the design and processing of the methodology proposal for work in unusual working conditions, it was necessary to make an appropriate selection and use of relevant methods. The advantages and disadvantages of the various methods are described in

Table 1.

When addressing the analytical aspects of the study, the following methodologies can be adopted: literature preview and analysis, observation, survey methods (questionnaires, etc.), data evaluation, and SWOT analysis, including the SWOT matrix. The following methods are available for the creation, processing, and evaluation of variants of solutions to the identified problems, their presentation, and estimation: induction and deduction method, methods of evaluating parameters and risks of work processes. In a broader sense, methods such as interviews with experts, group discussions, experiments, meta-analyses, etc. might also be helpful.

As shown in

Figure 4, the research process presented in the flow chart is structured into two interconnected phases that reflect theoretical and empirical dimensions. The initial strand begins with a thorough examination of the existing literature and practice, thus identifying knowledge gaps that serve as the foundation for the development of a targeted research questionnaire. The second part is dedicated to empirical input from surveys, which results are then incorporated into the design of a new methodological framework. The framework is then subjected to validation, a process which either confirms the results and leads to the formulation of benefits, or returns the process for revision. The sequential nature of this research process is intended to guarantee methodological integrity and applicability by correlating academic understanding with empirical validation.

In order to assess the correctness of the designed solutions, it was necessary to introduce given research questions (RQ):

Research Question 1 (RQ1): To what extent do variables related to the effectiveness of work activities influence work performance?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): What are the key parameters of risk and effectiveness in work activities and how can they be evaluated?

The confirmation or rejection of the presented research questions (RQ) must be proven as a result of the evaluation of designed solutions through verification during the tactical realisation of the management activities in the company.

To provide an overview of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, this study applies a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis. In this process, the questionnaires were evaluated in context to provide an overall assessment, which is important in this case, as the methodology can be applied to the sector as a whole. Important aspects such as company flexibility and the willingness to innovate are, of course, required for individual businesses to fully utilise the added value of this methodology. If individual evaluations took the form of a SWOT analysis, the added value for the respective company constellation could be filtered out. When the results obtained for RQ1 are summed, the variables noise, smell, air quality, etc. influence work performance differently. This depends on several factors, e.g. the sensitivity of the individual and the degree of salience of the respective variable. The key parameters in the risk area are the existing working conditions, such as the construction site in this case (type of person, interaction with third parties, etc.), air quality, location and how the work is carried out. Providing safe physical conditions (e.g. ergonomics, ventilation, and protective equipment) reduces risks and injuries, promoting healthier and more productive workers. A positive work culture and job satisfaction are crucial to retain young workers.

The evaluation is carried out from technical and health perspectives. From a technical perspective, this involves choosing the right tools for the job; from a health perspective, this involves environmental factors such as noise and the customers themselves.

The details can be seen specifically in the areas of Developing, Addressing Weaknesses, Mitigating Risks, and Avoiding Threats in

Table 2.

In the area of Developing (STRENGTHS/OPPORTUNITIES), the important topics are such as doing things differently from others, further developing, recognizing, and exploiting solutions for all persons involved, and securing a pioneering position on the market through rapid handling of the process.

In the area of Addressing Weaknesses (WEAKNESSES/OPPORTUNITIES), the important topics are such as increasing communication performance and thus raising awareness, focusing on the health of the entire staff, and digitizing internal communication and avoiding inconvenience.

In the area of Mitigating Risks (STRENGTHS/THREATS), the important topics are such as developing solutions for customers, suppliers, and clients in the area of communication, compensating for the lack of skilled workers on the labour market through a good working atmosphere, and positively shaping challenging activities with variety in the business.

In the area of Avoiding Threats (WEAKNESSES/THREATS), the important topics are such as staying one step ahead of the competition by raising the profile of the company, compensating for the lack of qualification of the staff through targeted training and further education, and focusing on the pressure of the business with challenging activities.

For a more professional understanding, it is useful to make a SWOT matrix. This matrix illustrates the strategic interconnections between Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats, and groups them into four strategy types: SO (Strengths–Opportunities), WO (Weaknesses–Opportunities), ST (Strengths–Threats), and WT (Weaknesses–Threats).

In the following SWOT matrix, rating and weighting are used to analyse the impact and significance of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. The rating assigns each factor a value from 1 (low) to 5 (high), which can influence the company’s success. On the other hand, assigns each factor a numerical value between 0 (low) and 1 (high), which indicates the strength of the factor and represents its importance. Finally, the weight score is calculated, which is the result of the rating multiplied by the weight.

4. Results and Discussion

The design of the methodology takes into account the generally valid principles and procedures for the evaluation of effectiveness (OUTPUT/INPUT) and risk of work (work processes). In our case, it is the evaluation (estimation) of work to be carried out under unusual conditions. This justifies the requirement of specific access to the compilation (projecting) of the methodology for the specific (nonstandard) conditions of the implementation as follows:

in collecting data on the (actual) state of implementation and assessment of the work with unusual working conditions;

for the division of the activities of the analysis of the collected information;

in the design (projecting) of the methodology, i.e. clear and unambiguous presentation of the individual steps of the procedure (precise and comprehensible determination of the objectives for all steps of the application);

simple but accurate assessment (determination) of the effectiveness (contributions) of the application of the methodology (formalisation for ITT application);

a predefined set of relevant and accessible methods for application in individual steps of the methodology;

defined standard values of indicators (parameters) of unusual working conditions.

In order for the application of the designed methodology to be helpful for the plant managers (in terms of the defined objectives), it is necessary to define very clear objectives (analytical specific objectives) for each step of the procedure and to assign the corresponding method(s) when designing the methodology.

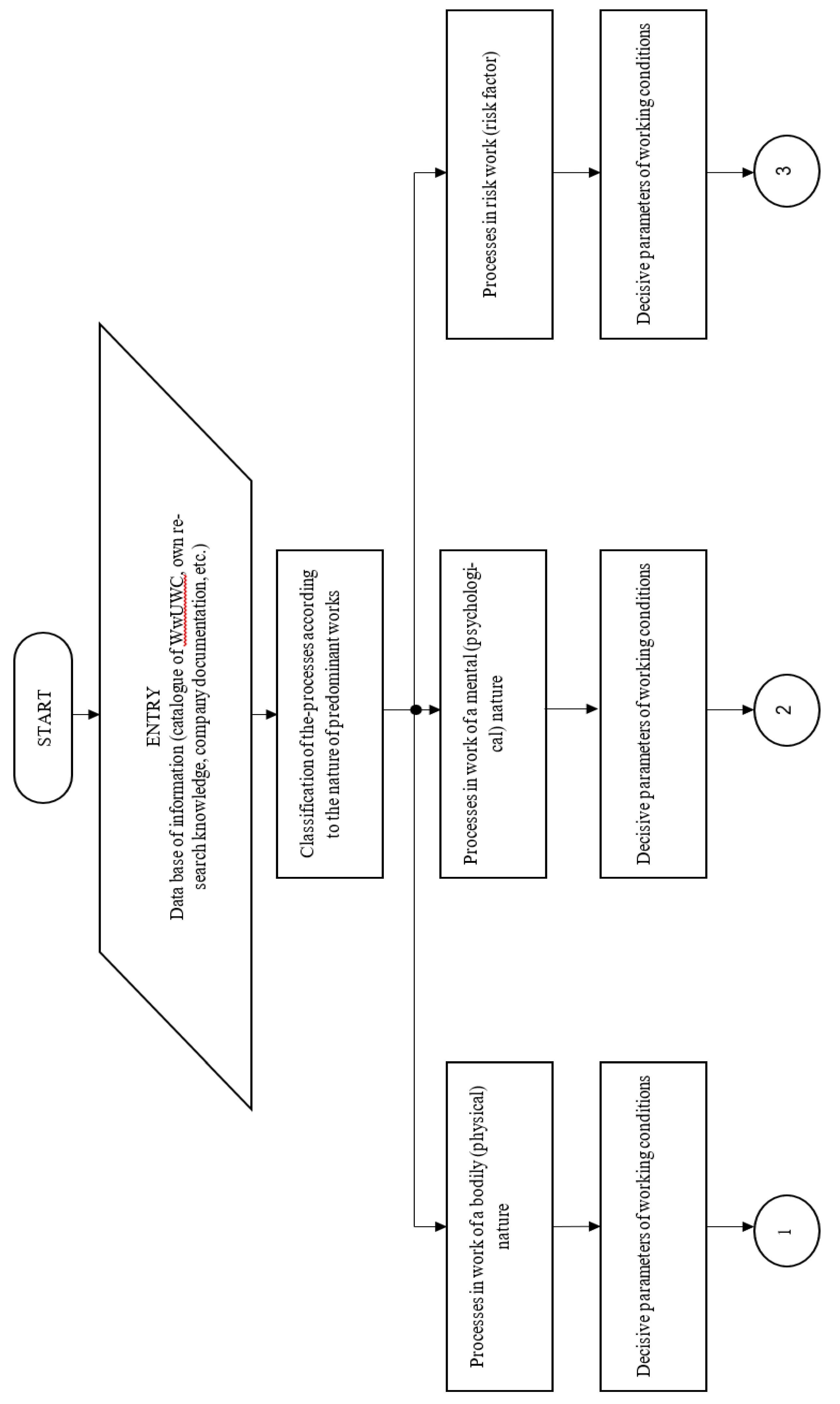

Finally, it is useful to develop a concrete procedure and a concrete time schedule for the implementation of the designed methodology. Based on the DMAIC principle,

Figure 5 presents the methodological workflow, showing the process used to define, assess, and refine risk factors under unusual working conditions

. Implementation and utilisation of the flow chart

The complexity of the structure (composition) of the flow chart is determined as a graphic representation of designed, methodical procedures and the complexity of understanding (interpretation) during practical implementation:

Complexity of the internal structure (content) of analysed processes (various types of work),

the totality of the various parameters of the working conditions of the analysed processes,

The necessity of a broad data base of the input information to be put together (collected, processed, preserved, maintained, protected).

The content, scope, and implementation of the individual steps of the flow chart of the designed methodical procedure are determined by the following influencing factors:

The database of entry information on the current status of the analysed work was acquired through the analysis survey.

The complexity of the parameters of the working conditions of the analysed work processes (selection according to the planned accuracy of identifying work with unusual working conditions).

Accessibility (timeliness and reliability) of the parameter values (standard and normative values) of the working conditions of the analysed work processes (necessity of elaboration or acquisition of information, or a combination of both),

The methods used and their complexity and accuracy for unusual working conditions (self-estimation, expert estimation, comparison, extrapolation, etc.).

Methods of assessing variations between real and normative values of UWC parameters (measurement, observation, comparison, expert estimation, etc.).

Classification of (unusual) working conditions according to complex chosen parameters (standard, usual, unusual).

Classification of work processes according to the impact of working conditions: effective work, ineffective work, standardised work (timing, cost, work performance) or risk work (health, accidents, convenience, etc.).

Expected form of output for practical application (e.g., agenda, printed manual, supported software).

Process flow charts provide an opportunity to select and implement effective procedures for analysing and evaluating work under unusual conditions. It is important to understand that + means ‘true’ and ‘false’.

For defined conditions (type of work and parameters of working conditions), the construction of the flow chart is adjusted and applied to a small extent. The construction (diagram) of the flow chart (branching) can be simplified, and the number of steps reduced, as can be shown rationally.

The practical application of the proposed methodology with the help of the flow chart will require theoretical knowledge, experience, practical skills, and the ability to choose the appropriate solution method quickly and optimally in each step of the procedure according to the specifications of the work process.

To verify the practical relevance and applicability of the proposed methodology, a structured SWOT analysis was conducted in cooperation with a group of selected industry specialists. These experts, who possess deep domain knowledge and operational experience with unusual working conditions, provided targeted input for the identification and prioritisation of strategic factors. Ratings and weights were assigned to each item based on their perceived impact and relevance in real-world implementation. The results were subsequently synthesised into the SWOT matrix presented in

Table 3, which reflects both internal and external dimensions of the evaluated work processes and supports strategic decision-making under variable workplace conditions. These were then integrated into the following SWOT matrix.

The SWOT matrix shows that the strengths/opportunities SO1, SO2, and SO3 are essential for the internationally active company. The weaknesses/opportunities WO1, WO2, and WO3 clearly demonstrate that health is a significant issue. The most significant issue in the area of strengths/threats ST1, ST2, and ST3 is that challenging construction projects can be undertaken, thus increasing market share. Furthermore, the market can be expanded using the methodology. The weaknesses/threats WT1, WT2, and WT3 play a significant role, as they currently exist in the market.

Short description of the following processes:

After the initial stage, data are collected and recorded from various sources, including information, our own research, company documentation, etc.

Existing knowledge gaps in the theory of unusual working conditions were closed by the generated definition. The resulting process or model presents classifications based on the type of predominant work. The processes are divided into work that involves physical labour, mental labour, and hazardous work. The key parameters of the working conditions for these three classifications are then presented. After evaluating the individual criteria in the subdivided classifications, you can proceed to the end or continue with the evaluation (comparison) of the actual and normative values of the parameters. After successfully completing this section, you will continue with the UWC process, up to the individual classification results and the conclusion.

To explain the entire process in more detail and to introduce a comprehensive understanding of the proposed methodology, the following section offers a detailed explanation of its constituent processes.

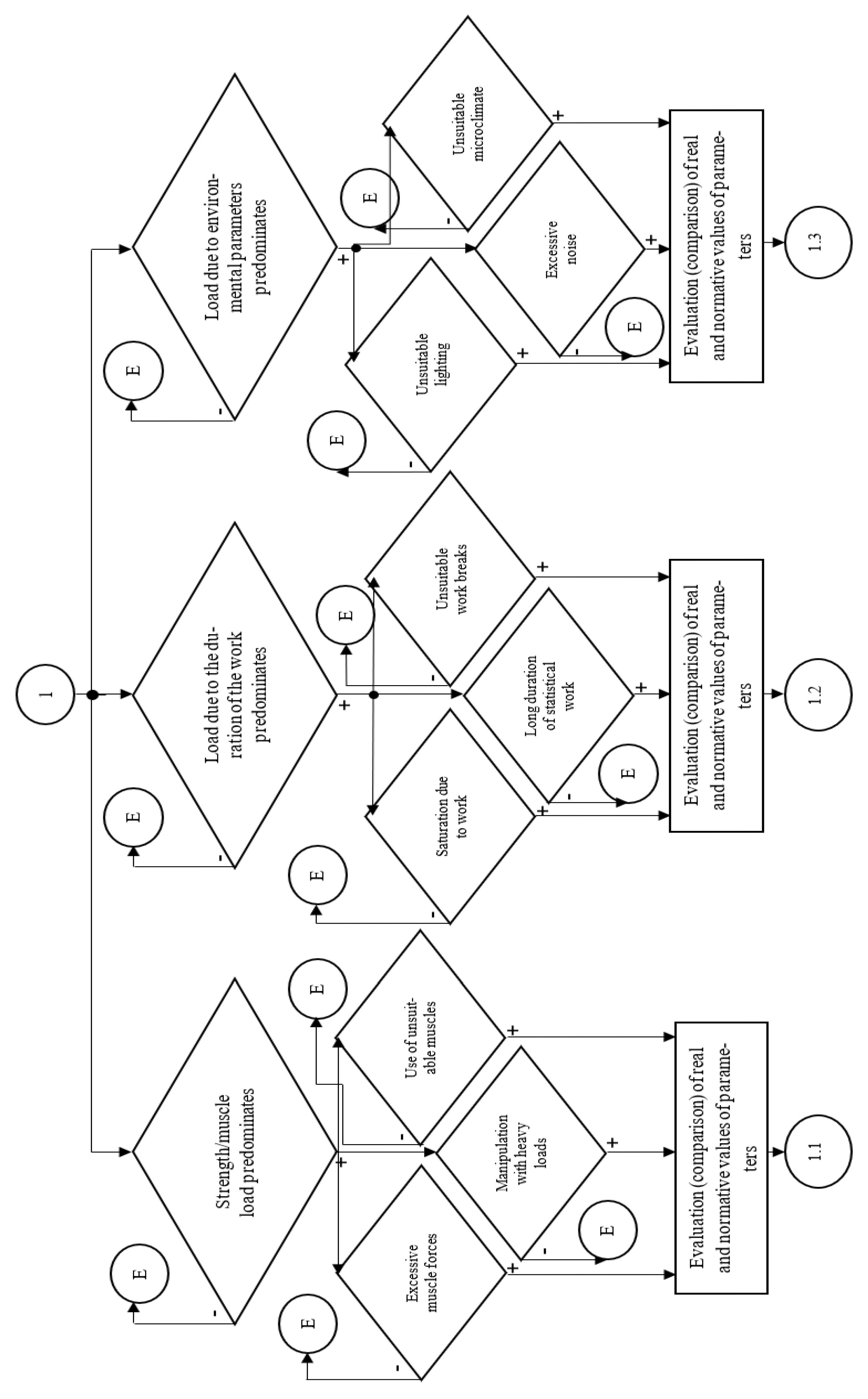

Process 1: Processes in work of a physical nature

Following the initial classification, the processes involved in physically demanding work are defined, as are the key parameters of the working conditions. If force/muscle load, load due to work duration, or load due to environmental parameters predominate, further approaches are selected. If none of these loads predominates, the process is complete. However, if one parameter is positive, the process continues.

In the area of force/muscle strain, it is determined whether heavy loads are being handled. This establishes whether excessive muscle strength or unsuitable muscles are required. Then, a comparison of the parameter values is performed.

In the area of workload duration, it is determined whether the duration of work is long, which establishes whether work saturation occurs or breaks are necessary. Then a comparison of the parameter values is performed.

In the area of environmental stress, it is determined whether there is excessive noise. This establishes whether the lighting or microclimate is not suitable. Then a comparison of the parameter values is performed.

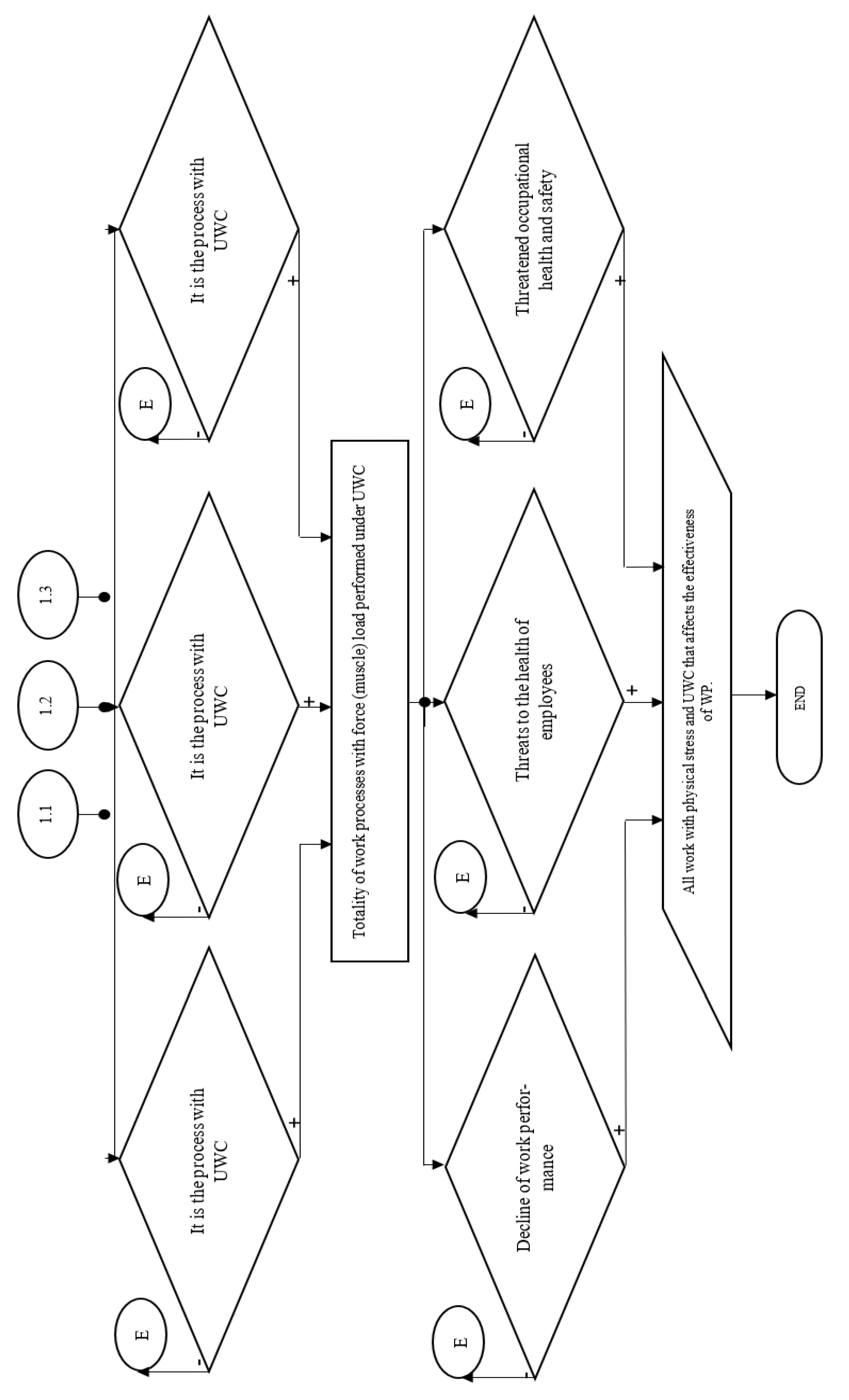

Next, it is determined whether the process involves unusual working conditions. If not, the process is terminated. However, if unusual working conditions are present, work processes involving physical/muscle strain will be carried out under these conditions.

Further parameters, such as reduced work performance, endangerment of employee health, and non-compliance with occupational safety regulations, allow the process to terminate immediately. If any of these parameters are positive, the entire work process involves physical strain under unusual working conditions that affect effectiveness.

The same can be done for Process 2: Processes in work of a mental (psychological) nature and Process 3: Processes in risk work (risk factor)

In process 2, after the start and classification, the processed psychological processes are defined, and the crucial parameters of the working conditions are explained. If the load on the sensory organs exceeds the strain on the brain (thinking, etc.) or the strain on work capacity, alternative approaches are chosen. If none of these loads prevail, the process is completed; however, if one parameter is positive, the process continues. After that the process follows like described in Process 1: Processes in work of a physical nature

In Process 3, on the other hand, after the start and classification, the processes in the risk work area (risk factors) are defined, and the most important parameters of the working conditions are explained. If the impacts on the work environment, health, and work hygiene or the effects on health and safety risks prevail, further approaches are chosen. If none of these impacts prevail, the process is concluded; however, if a parameter is positive, the process continues. As mentioned above, the process follows like described in Process 1: Processes in work of a physical nature.

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present a stepwise visualisation of the methodological workflow, supporting the structured interpretation of the evaluation procedure. Specifically,

Figure 6 introduces the classification logic used to differentiate between types of work processes based on their dominant characteristics.

Figure 7 outlines the core parameters evaluated within each category, highlighting key factors that influence the assessment of effectiveness and risk. Finally,

Figure 8 presents the specific types of load—physical, cognitive, and risk-related—that contribute to the emergence of unusual working conditions (UWC).

The proposed methodological framework, structured around the DMAIC principle, offers a structured and replicable approach to the analysis and optimization of work performance under unusual working conditions (UWC). It is confirmed that the clarity and formalization of procedural steps improve both the usability and safety of performing tasks in high-risk environments [

25,

26]. Specifically, the methodology allows the decomposition of complex work activities into clearly defined analytical steps, each of which is supported by appropriate evaluation methods and accessible parameter databases. The integration of standardized flowcharts with embedded decision nodes has demonstrated practical benefits in industrial pilot applications. Furthermore, the alignment of subjective stress indicators with physiological responses (e.g. HRV) has confirmed the relevance of the proposed classification of working conditions [

27,

28]. The scalability has been highlighted as a major strength by field experts, particularly in training environments and routine industrial assessments [

29,

30] . In line with recent findings, the success of implementing the methodology depends not only on the formal structure but also on the availability of well-trained personnel capable of interpreting data in real time and applying appropriate corrective or preventive measures. Thus, the method is not just a static protocol, but serves as a decision support system embedded in organizational learning [

31].

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that unusual working conditions have a considerable impact on employee health, performance, and the sustainability of the work environment. The methodological approach under consideration takes into account a variety of factors, including but not limited to the physical environment, the organisation of work, social and economic aspects, and psychosocial conditions. This aligns with the findings of study that occupational safety and health must be addressed holistically to support the four pillars of decent work: job creation, social protection, workers’ rights, and social dialogue [

32].

These factors have a considerable impact on health, work performance, and the sustainability of the work environment. These conditions are increasingly prevalent and are associated with elevated risks of burnout, reduced productivity, and long-term health issues [

33].

These factors are considered integral to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the promotion of decent work as part of Agenda 2030.

maintaining and promoting work ability across the life course requires safe and healthy working environments, and limits on excessive working hours, all of which are central to the concept of decent work and sustainable development [

34].

This identified gap in theory, but needed in practice, as the definition of unusual working conditions was simply closed and defined in such a way that there are no longer any open questions regarding unusual working conditions and their definition in this area. To improve theoretical knowledge relevant to the sector as a whole or analogous sectors, it is recommended that this article be utilised for information purposes. Similarly, the methodology designed is intended to be theoretically available for further development. It is possible that this methodology could be used to modify it for other specific sectors.

Regarding this study, ISO 9001:2015 Quality management systems can be used to anchor a permanent control in management. Furthermore, ISO 22 301: 2019 Business continuity management systems provide the opportunity to react very quickly to possible physical disruptions. This can prevent a prolonged system failure in the business. It also serves to identify and minimise vulnerabilities or eliminate them altogether.

Since this methodology has been designed for businesses in the national or international sector, as well as family-owned or strategically managed sectors, these documents and basic knowledge are also integrated into practice and training. In international companies, the basis in the areas of risks, operations management, effectiveness, efficiency, and, of course, physical stress is already integrated in the training programme. There, not only is the theory taught, but also the handling in practice is discussed on the basis of case studies, where this methodology has to be used. For this reason, one of the pilot companies also decided to expand the ‘Team Schmacher Academy’ programme with training courses such as risk management, operations management, communication, stress management, etc. This allows this process of methodology to be taught and implemented in its entirety, which strengthens overall success at every level of the business. Likewise, other courses such as mindfulness, conflict management, and NLP are offered for even better implementation of the designed methodology.

Another essential objective for the practice as well as for the training is to present this methodology in such an interesting, efficient, and economical way that it is not only interesting for the businesses or entrepreneurs, but also reaches the individuals in the company.

The process of the methods considers several factors such as the physical environment, work organisation, social and economic aspects, and psychosocial conditions, which are integral to achieving sustainable development goals and promoting decent work as part of Agenda 2030.

Emerging trends in workplace design and management are expected to prioritise adaptability, employee well-being, and the integration of intelligent technologies. The need for adaptability has long been recognised as essential for sustaining employability and respond to evolving workplace demands, particularly in the context of innovation and global competitiveness [

35]. At the same time, sustainable management of human resources emphasises employee well-being, development, and engagement as key drivers of satisfaction and organisational resilience [

36]. Adaptive performance, including creativity, stress management, and response to change, is increasingly viewed as a critical competency in dynamic work environments [

37,

38,

39].

From an environmental perspective, Huk and Kurowski [

40] stress the importance of factors in the context of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in work. Veselovska et al. [

41] point out that the elimination of specific risks is essential to strengthen CSR according to international standards.

Despite the practical relevance of the proposed methodology for assessing unusual working conditions (NWC), certain limitations need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the methodological framework was primarily developed and validated in an industrial setting. Its applicability in knowledge-based or service-based sectors (e.g. healthcare, education, creative industries) therefore remains to be sufficiently empirically investigated. The underlying assumptions regarding task structure, physical constraints and environmental standardization may not be fully transferable to other work contexts.

Secondly, the methodology relies on structured procedural modelling (DMAIC-based flowcharts), which presupposes a certain level of organisational maturity, data availability and employee training. In less formalised enterprises or SMEs, implementation may require adaptation or simplification to ensure usability and consistency. Another limitation concerns the subjectivity of certain input variables, such as perceived stress or task complexity, especially in self-assessment formats. Although expert estimates and observational protocols are built into the framework, further triangulation with objective physiological data would increase reliability and comparability.

To this end, future research should address the integration of real-time monitoring technologies as these tools can provide deeper insights into cognitive load, attentional focus, and decision-making dynamics in stressful situations, especially in conjunction with immersive or VR training.

In parallel, the refinement of standardized indicators and thresholds for classifying UWC across sectors should be prioritized. The legal frameworks, as discussed by Volker [

42], underline the need for transparent and predictable working conditions The development of a cross-sector UWC assessment or benchmarking platform would support comparative research and support policymakers in shaping transparent and resilient practices.

When implementing the methodology, it is essential to ensure that technological innovations support not only efficiency and safety, but also dignity, autonomy and trust of employees [

28,

43]. Khazieva et al. [

44] emphasise that the integration of knowledge management systems with artificial intelligence can generate synergistic effects in the optimisation of work processes. Further research will aim to explore how these innovations can be systematically incorporated into sustainable workplace strategies, while also addressing the potential risks and ethical considerations associated with their implementation

Based on the findings of this study, future research will focus on the evolving impact of technological advances on working conditions and organisational environments. As highlighted by Pauliková et al. [

45], emerging technologies, particularly in the field of human-robot collaboration, have the potential to significantly improve occupational safety and product quality.

In conclusion, while the proposed methodology shows significant potential, its continuous refinement, validation and contextualization remain essential to support sustainable, human-centered workplaces in line with the 2030 Agenda and ESG priorities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F: and B.K.S:; methodology, H.F: and B.K.S.; software, B.K:S.; validation, B.K.S.; formal analysis, H.F.; resources, H.F. and B.K.S, writing—original draft preparation, H.F: and B.K.S.; writing—review and editing, H.F: and B.K.S; visualization, H.F: and B.K.S; supervision, H.F.; funding acquisition, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the research project VEGA no. 2/0013/24 ‘Acceptance and use of innovations 4.0 in relation to cognitive gains and load in the context of sustainable development goals’ and based on results of successfully completed SDG4BIZ project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NLP |

Neuro-linguistic programming |

| RQ |

Request question |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| UWC |

Unusual working conditions |

| WP |

Work Process |

References

- Green, F.; Felstead, A.; Gallie, D.; Henseke, G. Working Still Harder. ILR Review 2022, 75, 458–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, B.I.; Nekhwevha, F. Exploring the Concepts of Decent Work through the Lens of SDG 8: Addressing Challenges and Inadequacies. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltser, A.V.; Yakubova, I.S.; Erastova, N.V.; Kropot, A.I. Assessment of Occupational A Priori Health Risk at the Workplace. Hygiene and Sanitation 2022, 101, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvitkina, M.; Pushenko, S.; Staseva, E. The Method of Assessing Occupational Risk Based on the Materials of a Special Assessment of Working Conditions. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 381, 01090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasota, H.; Hankiewicz, K. The Conceptual Framework for Physical Risk Assessment in Multi-Purpose Workplaces. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 137, 03007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covello, V.T.; Merkhoher, M.W. Risk Assessment Methods: Approaches for Assessing Health and Environmental Risks; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Paulikova, A.; Chovancova, J.; Blahova, J. Cluster Modeling of Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems for Integration Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatis, D.H. Failure Mode and Effect Analysis: FMEA from Theory to Execution; ASQ Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2003. ISBN 087389 5983.

- Hatiar, K.; Fidlerová, H.; Sakál, P. Ergonomic Programs Based on the HCS Model 3E as Integral Part of Sustainable CSR Strategy. In New Trends in Process Control and Production Management; CRC Press: 2018; pp. 169–174. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowska, A.; Ingaldi, M. Structural Failures Risk Analysis as a Tool Supporting Corporate Responsibility. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesarosova, J.; Martinovicova, K.; Fidlerova, H.; Hrablik Chovanova, H.; Babcanova, D.; Samakova, J. Improving the Level of Predictive Maintenance Maturity Matrix in Industrial Enterprise. Acta Logistica 2022, 9, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, A.J.; Ward, J.R.; Clarkson, P.J. Beyond FMEA: The Structured What-If Technique (SWIFT). J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 2012, 31, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, W.E.; Goldberg, F.F.; Roberts, N.H.; Haasl, D.F. The Fault Tree Handbook; Springer: 1981.

- Kletz, T.A. Introduction to Session on HAZOP Putting HAZOP in the Context Symposium. Series No. 155, Hazards XXI, IChemE 2009.

- Markova, P.; Homokyova, M.; Prajova, V.; Horvathova, M. Ergonomics as a Tool for Reducing the Physical Load and Costs of the Company. MM Sci. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmacher, B.; Fidlerova, H. Methods for Evaluating and Classifying Work Conditions According to Risks and Effectiveness. In MMK 2024; Magnanimitas: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2024; pp. 879–887. ISBN 978-80-87952-41-2. [Google Scholar]

- James, S.M.; Honn, K.A.; Gaddameedhi, S.; Van Dongen, H.P.A. Shift Work: Disrupted Circadian Rhythms and Sleep—Implications for Health and Well-Being. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2017, 3, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T.; Botelho-Guedes, F.; Cerqueira, A.; Simões, C.; Matos, M.G. Burnout as a Multidimensional Phenomenon: How Can Workplaces Be Healthy Environments? J. Public Health (Berl.) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonagle, A.K.; Chosewood, L.C.; Hartley, T.A.; Fisher, G.G.; Franche, R.-L. Chronic Health Conditions in the Workplace: Work Stressors and Supportive Supervision, Work Design, and Programs. Occup. Health Sci. 2024, 8, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoine, L.; Erhel, C.; Guergoat-Lariviere, M. Monitoring Quality in Work: European Employment Strategy Indicators and Beyond. Int. Labour Rev. 2008, 147, 164–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, T.; Smyth, E. Do Subjective Indicators Measure Welfare? Evidence from 33 European Societies. Eur. Soc. 2004, 6, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruijter, A.; Guldenmund, F. The Bowtie Method: A Review. Saf. Sci. 2016, 88, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, M. A Review of Occupational Health and Safety Risk Assessment Approaches Based on Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods and Their Fuzzy Versions. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2018, 7, 1723–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, S.; Le, A.H. Developing Adaptability for Workplace Performance and Change. In Future-Oriented Learning and Skills Development for Employability; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Balboa, I.C.; Caballero-Morales, S.O. Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control (DMAIC). In Lean Manufacturing in Latin America; García Alcaraz, J.L., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbusz, P.; Antosz, K. Assessment of the Effectiveness of Six Sigma Methodology Implementation—A Literature Review. In Advances in Production; Springer, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Narciso, D.; Melo, M.; Rodrigues, S.; Silva Cunha, J.P.; Bessa, M. Impact of Different Stimuli on User Stress During a Virtual Firefighting Training Exercise. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Bioinformatics and BioEngineering (BIBE), Cincinnati, OH, USA, 26–28 October 2020; pp. 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.; Hoermann, S.; Lukosch, S.; Lindeman, R. Design and Assessment of a Virtual Reality Learning Environment for Firefighters. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 6, 1274828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makransky, G.; Terkildsen, T.S.; Mayer, R.E. Adding immersive virtual reality to a science lab simulation causes more presence but less learning. Learn. Instr. 2019, 60, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porubcinova, M.; Gajniak, O.; Heriban, R. Expert Estimates of the Potential of AR, VR, BIM and AI Technologies to Support Sustainable Construction 4.0 in Slovak Construction Sector. Slovak J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 33, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, A. Practical skills training in enclosure fires: An experimental study with cadets and firefighters using CAVE and HMD-based virtual training simulators. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 125, 103440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, G.; Plescia, F.; Zerbo, S.; Verso, M.G.; Matera, S.; Skerjanc, A.; Cannizzaro, E. Work and Environmental Factors on Job Burnout: A Cross-Sectional Study for Sustainable Work. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.A.; Iavicoli, I.; Fontana, L.; Leka, S.; Dollard, M.F.; et al. Occupational Safety and Health Staging Framework for Decent Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilmarinen, J. Decent Work, ILO’s Response to the Globalization of Working Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, F.; Afshan, G.; Rana, S.A. Sustainable HRM and Well-Being: Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 74, 2289–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, B.G.; Mubarik, M.S. Advancing Sustainable Digital Transformations through HRIS in the Post-Pandemic Era. Sustainability 2023, 17, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo, M.A.; Henriques, P.L.; da Silva, M.J. Sustainable Employee Performance and Well-Being in Dynamic Work Environments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraňaková, N.; Stareček, A.; Babeľová, Z.G. Evaluation of HRM Processes Digitalisation by Different Genders. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 2024, 12, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, T.H.P.; Lorettob, W. Well-Being and HRM in the Changing Workplace. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 2229–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huk, K.; Kurowski, M. The Environmental Aspect in the Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Energy Industry and Sustainable Development of the Economy. Energies 2021, 14, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselovska, L.; Závadsky, J.; Závadska, Z. Mitigating Bribery Risks to Strengthen the Corporate Social Responsibility in Accordance with the ISO 37001. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1972–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, S. Implementation of the EU Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions—An Overview of the Changes to the Evidence Act and Other Laws. Monatsschrift für Deutsches Recht 2022, 76, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingaldi, M.; Ulewicz, R. The Use of Ergonomic Analysis to Improve the Workstation in the Production Process. Multidisciplinary Aspects of Production Engineering 2019, 2, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazieva, N.; Pauliková, A.; Chovanová, H.H. Maximising Synergy: The Benefits of a Joint Implementation of Knowledge Management and Artificial Intelligence System Standards. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2024, 6, 2282–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliková, A.; Gyurák Babeľová, Z.; Ubárová, M. Analysis of the Impact of Human–Cobot Collaborative Manufacturing Implementation on the Occupational Health and Safety and the Quality Requirements. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).